1. Introduction

The development of sustainable polymeric materials has become a global priority due to the environmental burden associated with non-biodegradable synthetic polymers [

1]. Conventional polymers derived from petroleum exhibit high resistance to degradation, leading to persistent waste accumulation and ecological damage in terrestrial and marine ecosystems [

2]. This has driven a paradigm shift toward bio-based alternatives that are renewable, functional, and environmentally benign. Among these, cellulose has emerged as a promising biopolymer because of its abundance, biodegradability, mechanical strength, and chemical versatility [

3,

4]. Its linear β-1,4-glucan structure, comprising crystalline and amorphous domains, confers high thermal stability, mechanical robustness, and chemical reactivity [

5]. These properties enable cellulose to serve as reinforcement in biocomposites, biodegradable films, micro- and nanocellulose fibers, aerogels, and biomedical matrices.

Effective utilization of cellulose depends on its purity, accessibility, and isolation method [

6]. In plant biomass, cellulose is tightly associated with hemicellulose and lignin in a complex lignocellulosic network that restricts accessibility [

7], necessitating pretreatments to achieve efficient fractionation. Chemical methods such as acid or alkaline hydrolysis, solvent extraction, and oxidative treatments are particularly attractive because they are selective, rapid, and scalable. While extraction from conventional sources such as rice straw [

8], sugarcane bagasse [

9], pea pod waste [

10], and coconut fibers [

11] have been widely reported, yields and purity vary according to biomass type and structure. While acid and alkaline hydrolysis have both been widely applied for cellulose extraction, their relative efficiency and impact on polymer-relevant properties remain highly dependent on biomass type and processing severity. Therefore, the exploration of underutilized plant resources that do not compete with food chains is critical for diversifying lignocellulosic feedstocks.

C. palmata (jipijapa palm) is a perennial herb native to Central and South America, traditionally exploited for handicrafts such as hat weaving due to the whiteness and flexibility of its fibers [

12]. Despite these properties, its potential as a cellulose source remains largely unexplored. The fibers are rich in cellulose, inexpensive, regionally abundant, and structurally accessible, making them a promising candidate for sustainable biopolymer production.

To maximize yield and purity, statistical optimization tools are increasingly employed. Response surface methodology (RSM), and in particular central composite design (CCD), allows efficient modeling of multifactorial processes, reducing experimental runs, identifying interactions, and defining optimal conditions [

13]. Several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of RSM in improving extraction efficiency and product quality from agricultural residues.

C. palmata remains virtually unexplored as a biopolymer source and historically restricted to artisanal weaving [

14]; its fibers exhibit chemical composition and structural properties that enable high cellulose yields under moderate conditions. This study not only addresses, for the first time, the statistical optimization of cellulose extraction from C. palmata using response surface methodology, but also validates the predictive accuracy experimentally, integrating a multifactorial approach that minimizes experimental runs while ensuring reproducibility. The crystalline and thermal stability values obtained highlight the competitiveness of C. palmata compared to other tropical fibers, underscoring its potential for emerging applications in PLA-based bioplastics, biodegradable films, and high-value biomaterials. Thus, this work broadens the spectrum of lignocellulosic feedstocks and contributes to circular bioeconomy strategies by promoting the sustainable use of regional resources. This approach has attracted increasing attention due to its biocompatibility and sustainability [

15].

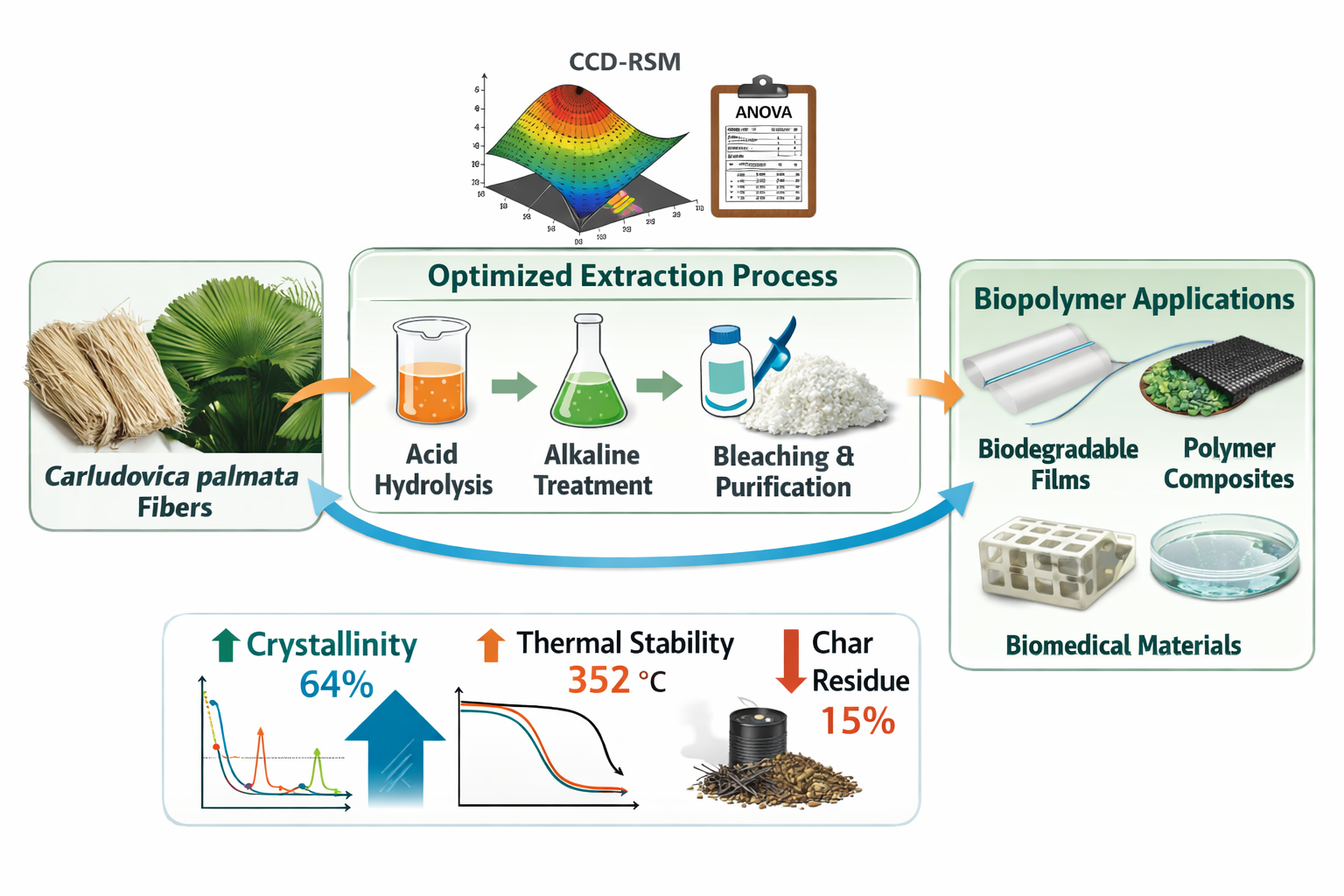

This study aimed to optimize the extraction of cellulose from C. palmata fibers through acid and alkaline hydrolysis, using CCD to model reagent concentration, temperature, and treatment time. Pretreatment and chlorination were included to enhance fractionation, and a comprehensive set of characterization techniques was applied: Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) to confirm the removal of hemicellulose and lignin, X-ray diffraction (XRD) to evaluate changes in crystallinity, and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) to assess thermal stability. Unlike previous studies, this work integrates: (i) a novel biomass source, (ii) a robust statistical optimization approach, and (iii) multiparametric chemical, structural, and thermal characterization. The results provide insights into the valorization of C. palmata fibers, contributing to bioeconomy strategies and the development of sustainable polymeric materials. This work demonstrates that statistical optimization enables the efficient extraction of cellulose with enhanced crystallinity and thermal stability, supporting the valorization of C. palmata fibers for biopolymer-based materials.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Buds of C. palmata (

Figure 1) were collected between October and December 2023 in Santa Cruz, municipality of Calkiní, Campeche, Mexico (20.396292° N, 90.238138° W). A total of 100 buds were harvested and processed immediately. Analytical-grade reagents were used: NaOH (97%, Meyer, VALDILAB), H

2SO

4 (95–98%, Sigma-Aldrich), and NaClO (commercial 5%, diluted as required).

2.2. Fiber Preparation

Fibers were obtained following the traditional artisanal technique used for weaving hats. The outer sheath was manually removed, the central vein was separated, and the leaf laminae were cut into strips and scraped to obtain uniform fibers. Fibers were air-dried under sunlight for four days and then stored in kraft paper bags at room temperature and controlled humidity (25 ± 2 °C, 60 ± 5% RH) until use.

2.3. Experimental Design

To perform statistical optimization, the coded values of the independent variables (

A: concentration (%),

B: temperature (°C), and

C: reaction time (min) were first defined based on ranges reported in the literature for similar lignocellulosic fibers. For clarity, the coded and real values used in this study are summarized in

Table 1 and

Table 2, corresponding to the acid and alkaline stages, respectively. These tables established the reference framework for the CCD.

Subsequently, RSM with CCD was applied to evaluate the combined effects of the three variables on cellulose yield (%). Five coded levels (−1.68, −1, 0, +1, +1.68) were employed to cover the experimental domain and to identify both linear and quadratic effects, as well as potential interactions. The CCD generated a total of 20 experimental runs (

Table 3 and

Table 4), including factorial, axial, and central points. The real parameter values assigned to each run, for both acid and alkaline treatments, are presented in

Table 3 and

Table 4, respectively. These tables served as the practical guide for conducting the experimental extractions under controlled conditions. Statistical modeling and analysis were performed using Design-Expert v.7.0.0 (Stat-Ease Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA).

2.4. Pretreatment

As an initial step, the fibers were subjected to an alkaline pretreatment aimed at disrupting ether linkages between lignin and hemicellulose, thereby increasing cellulose accessibility and facilitating subsequent fractionation. Based on reports for soft lignocellulosic fibers, mild NaOH conditions were selected to ensure effective delignification while minimizing cellulose degradation.

For each experimental run, 35 g of dried fiber were treated with 1 L of 4 wt% NaOH solution (solid–liquid ratio = 1:28.6 g/mL) in a mechanically stirred reactor (1200 rpm, OVAN three-station hot plate). The treatment was conducted at 100 °C for 60 min under reflux conditions. Following the reaction, the fibers were filtered, thoroughly washed with distilled water until reaching neutral pH (≈7, verified with pH indicator paper), and oven-dried at 60 °C for 24 h.

This pretreatment step produced cellulose-rich fibers suitable for the subsequent acid and alkaline treatment stages defined by the CCD experimental design.

2.5. Sequential Cellulose Extraction

After pretreatment, the fibers were subjected to a four-stage sequential process designed to progressively remove non-cellulosic components and increase cellulose yield. The acid and alkaline stages were carried out under the variable conditions defined by the CCD (see

Table 3 and

Table 4), while the chlorination and bleaching stages were maintained constantly for all experimental runs.

2.5.1. Acid Stage

Pretreated fiber was treated with H2SO4 solutions (1–5 wt.%) at 50–120 °C for 30–120 min in a reflux system. This step aimed to solubilize hemicellulose and partially disrupt the lignocellulosic matrix.

2.5.2. Chlorination Stage

Independently of the CCD, the acid-treated fibers were exposed to 3.5 wt.% NaClO for 15 min in an ultrasonic bath (Branson 2510). This oxidative treatment assisted in further delignification and microbial deactivation.

2.5.3. Alkaline Stage

Fibers were then treated with NaOH solutions (10–30 wt.%) at 50–100 °C for 60–180 min under reflux, according to the CCD matrix. This step targeted the removal of residual lignin, enhancing cellulose yield and accessibility.

2.5.4. Bleaching Stage

Finally, all runs were bleached under identical conditions using 0.5 wt.% NaClO for 90 min at 1500 rpm to improve whiteness and achieve final purification.

Between each stage, the fibers were filtered, thoroughly washed with distilled water until neutral pH, and oven-dried at 60 °C for 24 h. This sequential extraction ensured the gradual removal of hemicellulose and lignin, generating cellulose-rich fibers for subsequent structural and thermal characterization.

2.6. Characterization

2.6.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

The chemical structure of fibers before and after each stage was analyzed by FTIR spectroscopy (Nicolet 8700, Thermo Scientific). Samples were oven-dried at 60 °C for 24 h and finely ground (<250 μm). Spectra were recorded in the range of 4000–400 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1 and averaged over 100 scans. Baseline correction and normalization were performed prior to interpretation. Characteristic bands were assigned to cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin functional groups.

2.6.2. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD)

Crystallinity was determined using an X-ray diffractometer (Bruker D8 Advance, Cu Kα radiation, λ = 1.5406 Å, 40 kV, 30 mA). Powdered samples (<250 μm) were scanned over the 2θ range of 5–40° at a step size of 0.02° and a scanning speed of 1°/min. The crystalline index (CrI) was calculated using the Segal method, based on the ratio between the intensity of the crystalline peak (I200, ~22.5°) and the minimum intensity of the amorphous background (Iam, ~18°).

2.6.3. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

Thermal stability of the fibers was evaluated using a thermogravimetric analyzer (TA Instruments Q500). Approximately 8–10 mg of dried, ground sample were placed in a platinum pan and heated from 25 to 600 °C at a constant heating rate of 10 °C/min under a nitrogen atmosphere (flow rate: 60 mL/min).

2.6.4. Cellulose Yield Calculation

Cellulose yield was determined according to the following equation (1):

where Wo is the initial dry weight of the sample (g) and Wf is the final dry weight after treatment (g).

3. Results

3.1. Model Adequacy and ANOVA

Table 5 summarizes the main ANOVA results obtained for the acid and alkaline stage applied to Carludovica palmata fibers. In both cases, the global models were statistically significant (p<0.05), confirming the adequacy of the CCD–RSM approach to describe the influence of process variables on cellulose yield. For the acid treatment, the analysis revealed that both acid concentration and temperature exerted significant linear effects, while only acid concentration showed a quadratic contribution, indicating that intermediate levels of severity favored higher yields. In contrast, the alkaline treatment was dominated by nonlinear behavior, with quadratic effects of NaOH concentration and temperature emerging as the main contributors to yield, whereas the linear and interaction terms were not significant. These differences reflect distinct mechanistic pathways: acid treatment relies on controlled removal of hemicellulose at moderate conditions, while alkaline treatment requires a balance between sufficient lignin removal and prevention of cellulose degradation. The optimal conditions predicted and validated experimentally—3 wt% H

2SO

4 at 85 °C for 75 min and 20 wt% NaOH at 70 °C for 120 min—support the conclusion that both treatments must be carefully tuned to avoid excessive severity that compromises cellulose recovery.

3.2. Cellulose Yield

The evaluation of cellulose yields obtained through acid and alkaline treatments revealed clear differences in both absolute values and variability (

Table 6). For the acid treatment, yields ranged from 27.5% to 42.7%, with an overall average of approximately 38–40%. This behavior reflects the ability of H

2SO

4 to hydrolyze hemicelluloses and partially release cellulose, although it does not achieve complete lignin removal [

16,

17]. The dispersion of values also indicates a strong sensitivity of the process to changes in concentration and temperature, which is consistent with the linear and quadratic effects identified by ANOVA for this stage.

In contrast, the alkaline treatment achieved higher yields, ranging from 19.8% to 57.7%, with an average of about 47–50%. The highest values were associated with the action of NaOH in disrupting ether and ester linkages between lignin and carbohydrates, promoting a more efficient fractionation of the lignocellulosic matrix and yielding fibers with greater cellulose purity [

18]. However, the variability observed also indicates that under excessive severity (high concentrations or prolonged times), partial cellulose degradation may occur, reducing the effective yield.

When comparing both treatments, the alkaline process outperformed the acid one by up to 15 percentage points, confirming its superior efficiency in removing non-cellulosic components while preserving the crystalline cellulose fraction. This trend aligns with previous reports on tropical fibers and agro-industrial residues, where alkaline hydrolysis typically results in the highest yields and improved structural quality [

19,

20]. Overall, the results demonstrate that careful optimization of operational parameters is essential to maximize yield without compromising polymer integrity.

The cellulose yield obtained from C. palmata under optimized alkaline conditions (57.7%) is comparable or superior to several conventional lignocellulosic sources. For instance, biomass lignocellulosic has been reported to have yields around 50% [

21], while rice husk yields about 58% cellulose [

22]. This suggests that C. palmata combines relatively high yield with enhanced structural properties, making it more suitable for advanced material applications. Banana residues, in contrast, exhibit significantly lower yields (30%) [

23]. The low recovery efficiency from banana residues limits their scalability, whereas C. palmata offers a more balanced performance between yield and crystallinity. Coconut fibers exhibit higher yield (70%) [

24]. Taken together, these comparisons reinforce the competitiveness of C. palmata as a non-conventional feedstock. Unlike agro-industrial residues such as rice husk or bagasse, which are often tied to existing industrial chains, C. palmata represents an underutilized regional resource that can be valorized for high-performance cellulose. Its combination of moderate-to-high yield, improved crystallinity, and enhanced thermal stability makes it a promising candidate to produce biodegradable films, reinforced composites, and biomedical materials, situating it favorably among the spectrum of tropical lignocellulosic biomasses.

3.4. FTIR Characterization

Figure 2 compares FTIR spectra of untreated (natural fibers) and fibers subjected to pretreatment, acid hydrolysis, and alkaline hydrolysis.

The untreated fibers displayed a broad O–H stretching band at ~3300 cm

−1, C–H stretching at 2900 cm

−1, a carbonyl band at 1730 cm

−1 (hemicellulose), and aromatic lignin peaks near 1600 cm

−1. After pretreatment, the intensity of hemicellulose and lignin bands decreased, while cellulose-associated peaks (1000–900 cm

−1) became more prominent. Acid-treated fibers showed the near-complete disappearance of the 1730 cm

−1 band, confirming hemicellulose removal, though a residual lignin signal remained at 1600 cm

−1. By contrast, alkaline treatment eliminated both hemicellulose and lignin bands, leaving cellulose as the dominant component, particularly the sharp C–O–C stretching band at 1030 cm

−1 [

25]. This agrees with prior studies reporting that NaOH is highly effective for simultaneous lignin removal and cellulose purification [

26]. Overall, FTIR confirmed progressive purification of cellulose, with alkaline treatment producing the highest chemical homogeneity and structural integrity.

3.5. Response Surface Analysis

Figure 3, corresponding to the acid treatment, an initial increase in cellulose yield is observed as both H

2SO

4 concentration and temperature reaction, reaching a maximum at approximately 4% and 60 °C. However, higher levels of either variable lead to a decrease in yield, attributed to partial cellulose chain degradation and the formation of hydrolysis by-products. This parabolic behavior, confirmed by the significant quadratic terms in the model (

Table 5), indicates that intermediate conditions are necessary to maintain polymer integrity.

Figure 4, representing the alkaline treatment, the surface displays a broad plateau that defines the optimal region around 20%, 70 °C, consistent with the experimentally validated conditions. The yield increase at moderate alkali concentrations is related to the efficient cleavage of ether and ester linkages between lignin and carbohydrates, facilitating the release of high-purity cellulose [

27]. However, excessive reaction time or concentration slightly reduces the yield due to partial solubilization of amorphous cellulose fractions. The combined analysis of both surfaces demonstrates that the alkaline treatment provides a wider stability region and a higher maximum yield (57.7%) compared with the acid process (42.7%). This trend confirms the superior selectivity of NaOH for removing lignin and hemicellulose while preserving crystalline microfibrils. Therefore, the statistical model not only identified the optimal parameters but also clarified the nonlinear interactions among process variables, providing a robust predictive framework for potential scale-up of the extraction procedure.

3.6. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

Figure 5 shows the XRD patterns of untreated, acid, and alkali treated fibers. The untreated fibers exhibited diffraction peaks at 2θ ≈ 15.8°, 22.4°, and 34.6°, corresponding to the (1–10), (200), and (004) crystallographic planes of cellulose I, respectively. The crystalline index (CrI), calculated using the Segal method, was 41.2% for untreated fibers. After acid hydrolysis, the CrI increased to 52.7%, reflecting partial removal of amorphous hemicellulose and lignin. The highest CrI was obtained for alkali-treated fibers (63.8%), confirming that NaOH was more effective in eliminating non-cellulosic fractions and exposing crystalline cellulose domains.

These values are consistent with previous reports for lignocellulosic biomass subjected to chemical purification, where CrI values typically increase from ~40% to ~60% after sequential treatments [

28]. The shift toward higher crystalline indicates improved structural order, which is desirable for applications in reinforcement and film formation. The results validate that C. palmata fibers possess a crystalline structure comparable to other non-conventional cellulose sources such as peanut shells and banana residues [

29,

30].

3.7. Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

Figure 6 presents the thermogravimetric curves of untreated and chemically treated fibers. The untreated fibers showed an initial weight loss (~7%) below 120 °C due to moisture evaporation [

31]. Major thermal degradation occurred between 220–360 °C, with a maximum decomposition rate (Tmax) at 328 °C, attributed to hemicellulose and lignin degradation along with partial cellulose breakdown [

32]. Residual char at 600 °C was 28%, reflecting the presence of lignin and inorganic components. In contrast, acid-treated fibers exhibited a higher Tmax (338 °C) and reduced char residue (21%), confirming partial purification of cellulose and removal of thermally labile hemicellulose. Alkali-treated fibers displayed the highest thermal stability, with Tmax at 352 °C and char residue reduced to 15%. The improved stability is attributed to the higher crystalline observed in XRD and the removal of lignin, which typically decomposes over a wide temperature range and contributes to char formation. These findings agree with prior studies on chemically treated lignocellulosic fibers, where alkaline treatments enhanced both crystallinity and thermal resistance [

20,

30]. The results suggest that cellulose isolated from C. palmata is thermally stable up to ~350 °C, making it suitable for processing into biocomposites, biodegradable films, and other thermoplastic-compatible applications.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that Carludovica palmata fibers are a viable and competitive source of cellulose when processed under statistically optimized chemical conditions. The application of response surface methodology based on a central composite design enabled the identification of optimal operational windows for both acid and alkaline treatments, maximizing cellulose yield while minimizing excessive process severity. The multivariate optimization framework proved essential to capture nonlinear effects and interactions that cannot be resolved using conventional one-factor-at-a-time approaches, resulting in statistically significant and predictive models. Under optimized conditions, cellulose yields of 42.7% (acid stage) and 57.7% (alkaline stage) were achieved, positioning C. palmata favorably among non-conventional lignocellulosic feedstocks.

Beyond yield enhancement, statistical optimization directly influenced polymer-relevant properties of the extracted cellulose. Structural characterization confirmed a marked increase in crystallinity from 41% in untreated fibers to 64% after optimized alkaline treatment, while thermogravimetric analysis revealed improved thermal stability, with the main degradation temperature increasing from 328 °C to 352 °C and a substantial reduction in char residue. These results indicate that optimization is not merely a process intensification strategy, but a key tool to tailor cellulose structure and performance for downstream polymer processing. The optimized cellulose exhibits characteristics suitable for biodegradable films, polymer composites, and biopolymer-based materials, highlighting the transferability of the proposed approach to other underutilized biomasses within sustainable polymer engineering and circular bioeconomy frameworks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.A.C.P. and A.O.F.; methodology, R.A.C.P. and E.P.P.; software, J.C.C.P.; validation, E.P.P., M.A.D.D.C., and A.O.F.; formal analysis, R.A.C.P. and M.A.D.D.C.; investigation, R.A.C.P. and Y.A.C.C.; resources, C.R.R.S.; data curation, R.A.C.P.; writing—original draft preparation, A.O.F.; writing—review and editing, E.P.P., M.A.D.D.C., and A.O.F.; visualization, C.R.R.S.; supervision, A.O.F.; project administration, A.O.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding. The APC was funded by the authors.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge M.Sc. José Rodríguez Laviada for his technical assistance. The authors acknowledge the Tecnológico Nacional de México (TecNM) and the Instituto Tecnológico Superior de Calkiní (ITESCAM) for providing the infrastructure and technical support required for this research. Special thanks are extended to the Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán (CICY) for access to its facilities and instrumental characterization support. The authors also thank the Bioprocesses Academic Group for their support in data interpretation. Rogelio Antonio Canul Piste acknowledges the scholarship support provided by SECITHI.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Kothawade, S.N., et al., Biodegradable and Non-Biodegradable Sustainable Biomaterials, in Advances in Sustainable Biomaterials. 2024, CRC Press. p. 92-116.

- Ghanbarzadeh, B. and H.J.B.-l.o.s. Almasi, Biodegradable polymers. 2013: p. 141-185.

- Marinho, E.J.S.C.f.t.E., Cellulose: A comprehensive review of its properties and applications. 2025: p. 100283.

- Zidi, S., Cellulose of sisal fibers integration in papermaking: mechanical and thermal characterization. Multiscale and Multidisciplinary Modeling, Experiments and Design, 2025. 8(1): p. 73. [CrossRef]

- Fredricks, J.L., et al., Hierarchical biopolymer-based materials and composites. 2023. 61(21): p. 2585-2632. [CrossRef]

- Acharya, S., et al., Utilization of cellulose to its full potential: a review on cellulose dissolution, regeneration, and applications. 2021. 13(24): p. 4344. [CrossRef]

- Berglund, J., et al., Wood hemicelluloses exert distinct biomechanical contributions to cellulose fibrillar networks. 2020. 11(1): p. 4692. [CrossRef]

- Razali, N.A.M., et al., Comparative study on extraction of cellulose fiber from rice straw waste from chemo-mechanical and pulping method. 2022. 14(3): p. 387. [CrossRef]

- Melesse, G.T., et al., Extraction of cellulose from sugarcane bagasse optimization and characterization. 2022. 2022(1): p. 1712207. [CrossRef]

- Bhiri, F., et al. A Renewable Cellulose Source: Isolation and Characterization of Cellulose Microfibers from Pea Pod Waste. in Euro-Mediterranean Conference for Environmental Integration. 2021. Springer.

- Rahayu, A., et al., Cellulose extraction from coconut coir with alkaline delignification process. 2022. 1(2): p. 106-116. [CrossRef]

- Ravirajashetty, G. and T.J.I.J.O.A.S. Arif, CONSERVATION AND CRYOPRESERVATION OF RARE, ENDANGERED AND THREATENED MEDICINAL PLANTS OF WESTERN GHATS.

- Szpisják-Gulyás, N., et al., Methods for experimental design, central composite design and the Box–Behnken design, to optimise operational parameters: A review. 2023. 52(4): p. 521-537. [CrossRef]

- Hernández, H.A.M., et al., La palma jipi en México: un cultivo tradicional y símbolo de identidad cultural. 2025. 22(1): p. 18-23. [CrossRef]

- Kargupta, T., et al., An insight into thermal, chemical, and structural characterization of biopolymers. Discover Applied Sciences, 2025. 7(8): p. 1-25. [CrossRef]

- Xu, N., et al., Hemicelluloses negatively affect lignocellulose crystallinity for high biomass digestibility under NaOH and H2SO4 pretreatments in Miscanthus. 2012. 5(1): p. 58. [CrossRef]

- Wyman, C.E., et al., Hydrolysis of cellulose and hemicellulose. 2005. 1: p. 1023-1062.

- Wang, L., et al., Extraction strategies for lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose to obtain valuable products from biomass. 2024. 7(6): p. 219. [CrossRef]

- Shah, A.M., et al., The Vital Roles of Agricultural Crop Residues and Agro-Industrial By-Products to Support Sustainable Livestock Productivity in Subtropical Regions. 2025. 15(8): p. 1184. [CrossRef]

- Singh nee’Nigam, P., N. Gupta, and A. Anthwal, Pre-treatment of agro-industrial residues, in Biotechnology for agro-industrial residues utilisation: utilisation of agro-residues. 2009, Springer. p. 13-33.

- Castillo Morejón, H.P. and J.I. Llano Pérez, Optimización en la producción de bioetanol a partir de biomasa lignocelulósica: métodos y tecnologías sostenibles. 2025.

- Hafid, H.S., et al., Enhanced crystallinity and thermal properties of cellulose from rice husk using acid hydrolysis treatment. 2021. 260: p. 117789. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S., et al., Banana peel waste: An emerging cellulosic material to extract nanocrystalline cellulose. 2022. 8(1): p. 1140-1145. [CrossRef]

- Ndruru, S.T.C.L., et al., Facile synthesis of carboxymethyl cellulose from Indonesia’s coconut fiber cellulose for bioplastics applications. 2024. 64(9): p. 4144-4160. [CrossRef]

- Karimah, A., et al., The effect of active alkali and sulfidity loading on the kraft pulp properties of sweet sorghum bagasse. 2023. 25(5): p. 1196-1210. [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Estrada, A., et al., Assessment and classification of lignocellulosic biomass recalcitrance by principal components analysis based on thermogravimetry and infrared spectroscopy. 2022. 19(4): p. 2529-2544. [CrossRef]

- Schutyser, W., et al., Chemicals from lignin: an interplay of lignocellulose fractionation, depolymerisation, and upgrading. 2018. 47(3): p. 852-908. [CrossRef]

- Kafle, K., et al., Effects of delignification on crystalline cellulose in lignocellulose biomass characterized by vibrational sum frequency generation spectroscopy and X-ray diffraction. 2015. 8(4): p. 1750-1758. [CrossRef]

- Fermanelli, C.S., et al., Towards biowastes valorization: Peanut shell as resource for quality chemicals and activated biochar production. 2022. 32(1): p. 3. [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, N.A.A.N., et al., Determination of structural, physical, and thermal properties of biocomposite thin film from waste banana peel. 2019. 81(1).

- Rashid, B., et al., Physicochemical and thermal properties of lignocellulosic fiber from sugar palm fibers: effect of treatment. 2016. 23(5): p. 2905-2916. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H., et al., In-depth investigation of biomass pyrolysis based on three major components: hemicellulose, cellulose and lignin. 2006. 20(1): p. 388-393. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |