1. Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a common functional gastrointestinal disorder, characterized by recurrent abdominal pain associated with altered bowel habits [

1]. Diagnosis is most often established using the Rome IV criteria, which relies on the evaluation of symptom patterns in the absence of detectable structural abnormalities [

2]. The different subtypes of IBS, including IBS with constipation (IBS-C), with diarrhea (IBS-D), IBS mixed (IBS-M), and IBS unclassified (IBS-U), are defined by the predominant stool morphology on abnormal bowel movement. The global prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome is estimated to range from 4% to 10%, variations depending largely on the diagnostic criteria applied [

3]. IBS disproportionately affects women and younger adults, although men are also substantially affected [

3,

4,

5]. Living with IBS can present significant challenges. Pain, bowel difficulties and bloating contribute to the severity of the condition, whereas dietary restrictions to manage symptoms add to the burden of the condition [

6]. Additional contributors to IBS severity include social limitations, occupational and academic difficulties, cognitive impairments, sleep disturbances, nausea, and fecal incontinence. Comorbidities such as anxiety, depression, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, and sleep disturbances are also frequently reported among IBS patients [

7]. The impact on quality of life can be so profound that some patients with IBS report a willingness to sacrifice 10-15 years of life in exchange for an immediate cure [

8]. Additionally, many individuals perceive IBS as an economic burden [

8,

9].

Pathophysiology

The exact pathophysiology of IBS remains unclear; however, multiple mechanisms have been implicated. Alterations in the gut-brain axis are central, with evidence suggesting bidirectional dysregulation between the enteric nervous system, vagal pathways, neuroendocrine signaling, and higher brain centers [

10,

11]. Visceral hypersensitivity, defined as an enhanced perception of intestinal stimuli, is another hallmark of IBS [

12]. Patients typically exhibit a lowered pain threshold and heightened response to luminal distension, gas production, and motility changes [

12]. Accumulating evidence also implicates alterations in the gut microbiota [

13]. Shifts in microbial composition may promote mucosal immune activation, changes in fermentation patterns, and increased production of metabolites that influence motility and sensitivity [

13]. Low-grade mucosal inflammation and immune activation are additional features reported in IBS, including elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines and increased numbers of mast cells in close proximity to the enteric nerves [

14]. Other proposed mechanisms include abnormal bile acid metabolism, altered serotonin signaling, and genetic components [

14].

Dietary Management of IBS

Dietary factors play an important role in symptom manifestation; therefore, dietary management is central to IBS treatment [

14] . The specific types of food that trigger the symptoms and the nature of these symptoms can vary among individuals. Among the most well-known dietary triggers are specific carbohydrates such as fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs), which appear to cause symptoms in IBS patients [

3]. These carbohydrates are found in dairy products containing lactose, legumes, sugar alcohols, vegetables, nuts, cereals, and some fruits. FODMAPs generally pass through the small intestine to the colon without undergoing digestion [

15]. The mechanism behind the intolerance to FODMAPs is not fully understood but could partly be explained by inter-individual differences in the ability to digest certain FODMAPs due to lack- or reduced levels of necessary enzymes [

15].

Current recommendations, such as the NICE guidelines and the low-FODMAP diet, may alleviate symptoms but can be restrictive and difficult to maintain over the long term. A very low-carbohydrate diet also appears to exert beneficial effects on symptom severity, particularly in individuals with IBS-D [

16]. Adjuncts include selected fibers, probiotics, digestive enzymes, pharmacotherapies, psychological therapies, and investigational strategies such as fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), however with mixed results [

14,

17]. Owing to the heterogeneous pathophysiology of IBS patients and their varying responses to current treatment options, there is a need to expand available therapeutic approaches.

The Rationale for Fasting in IBS

Fasting encompasses a range of dietary regimens that involve voluntary abstinence from some or all foods, or foods and beverages, for preventive, therapeutic, religious, cultural, or other reasons, as defined in recent consensus statements [

18]. The most restrictive forms include dry fasting and fluid-only fasting. Dry fasting involves complete abstinence from both food and fluids, whereas fluid-only fasting permits the intake of water and other non-caloric beverages [

18]. Other restrictive approaches include prolonged fasting and short-term fasting, which typically extend over several consecutive days. Less restrictive fasting strategies include modified fasting and fasting-mimicking diets, which allow limited energy intake while aiming to induce fasting-related metabolic responses. Intermittent fasting represents a broader category characterized by repeated fasting periods interspersed with periods of ad libitum intake. Time-restricted eating (TRE) constitutes one of the least restrictive fasting-related approaches and is defined by limiting daily food intake to a consistent time window, without explicit restrictions on food type or caloric intake. As such, TRE is often considered a behaviorally feasible and flexible strategy compared with more restrictive fasting regimens.

Mechanistic studies suggest that fasting may influence gut motility, immune responses, and microbiota composition, processes that are relevant to gastrointestinal physiology and have been implicated in IBS [

19]. The ingestion of food and beverages represents a continuous physiological demand on the gastrointestinal tract, which must provide protection against hostile microorganisms, environmental contaminants, toxins, and potentially harmful endogenous substances such as acids, bile acids, digestive enzymes, and dietary antigens [

20]. Mechanical stress resulting from gastrointestinal contractile activity constitutes another physiological burden [

20]. To maintain homeostasis, the intestinal epithelium must respond rapidly to mechanical, chemical, and microbial stressors. The capacity to repair damage and adapt to these stressors is essential for maintaining digestive function and mucosal integrity and may be relevant in conditions characterized by low-grade inflammation [

20]. During periods of fasting, several biological processes—including activity of the migrating motor complex, metabolic switching, autophagy-related pathways, epithelial renewal, modulation of the gut microbiota, and cellular stress responses—have been proposed to play a role [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28]. Together, these observations provide a framework of biological plausibility for investigating time-restricted eating in IBS.

Despite increasing interest both in fasting regimens and dietary interventions for IBS, no study has investigated the effects of TRE on symptom severity in this population. This pilot study aimed to examine whether an 8-week TRE intervention (16:8) protocol could reduce IBS-related symptoms.

2. Materials and Methods

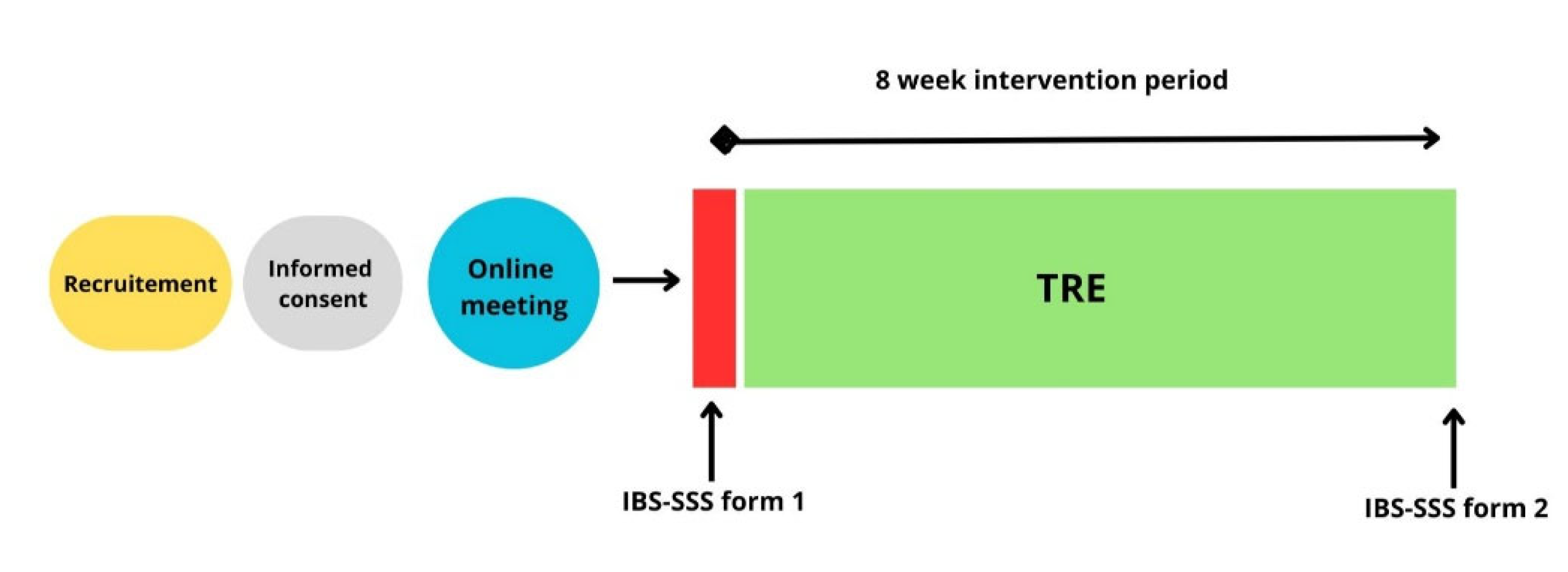

This single-group intervention pilot study examined the effects of TRE on symptom severity in patients with IBS. Participants completed an 8-week dietary intervention, with outcome measures assessed at baseline and post-intervention for the primary study period (

Figure 1). An additional follow-up assessment was conducted at approximately 12 months. The study was not prospectively registered in an international clinical trial registry. To enhance transparency, the study was retrospectively registered in the Open Science Framework (OSF) after completion of data collection (registration date: 22.12.2025).

Population and Recruitment

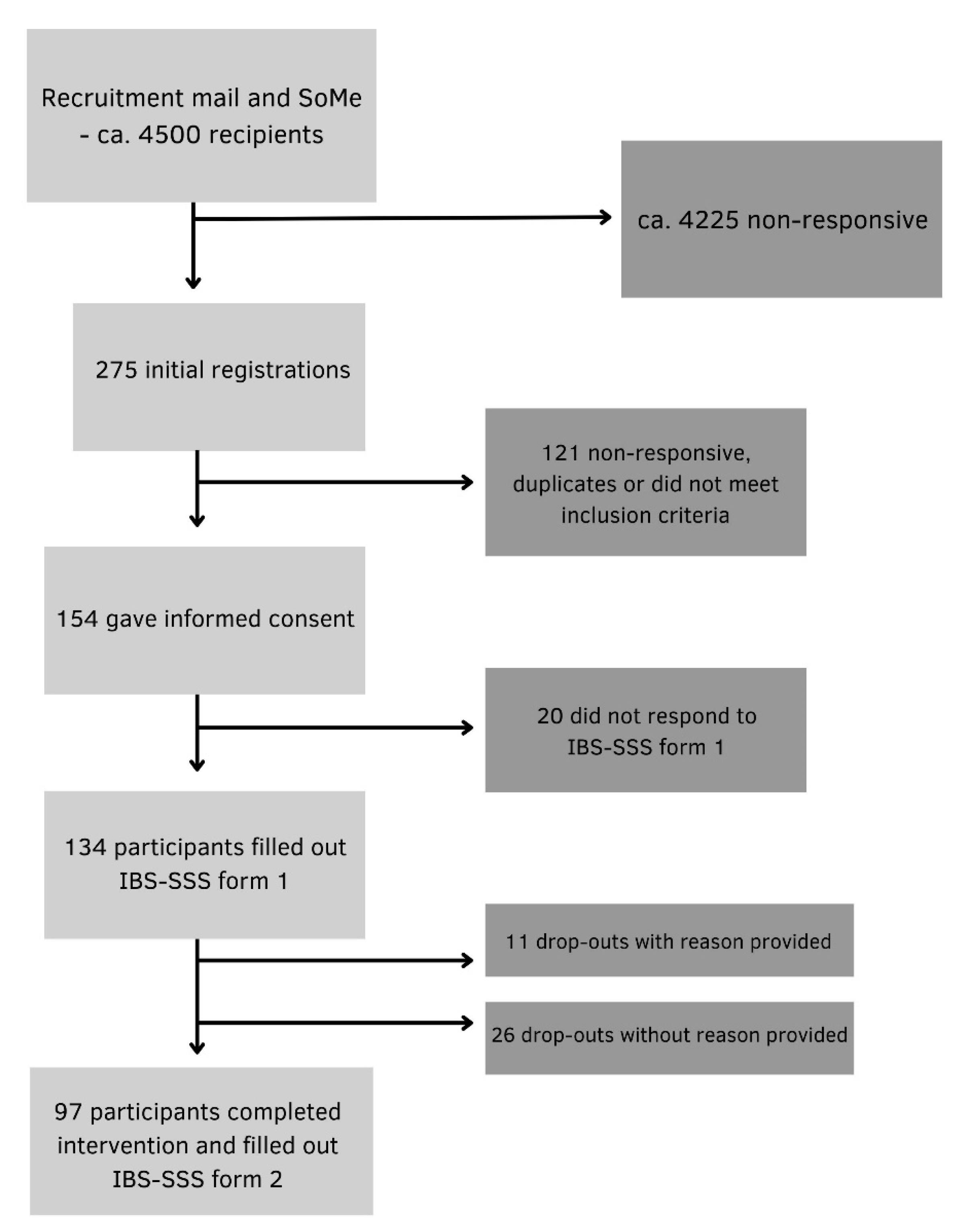

Participants were recruited from the Norwegian Gastrointestinal Association (approximately 4500 members), via information letters published on the association’s website, email and posts on social media platforms. Participants ≥ 18 years of age with a self-reported confirmed IBS diagnosis (from a primary care physician or the specialist health care service) and no prior experience with intermittent fasting methods were included. The exclusion criteria were pregnancy, breastfeeding, underweight (BMI < 18.5 kg/m^2), history of surgery resulting in altered gastrointestinal anatomy, eating disorders and other conditions with symptoms similar to IBS. 134 participants provided digitally obtained informed consent and were enrolled in the study. A total of 97 participants completed the intervention and were included in the final analysis (

Figure 2).

Intervention

The intervention was a pre/post design TRE regimen (16:8) where all participants were instructed to restrict their daily food intake to an 8-hour window while fasting for 16 h between September 16th and November 10th, 2024. One week prior to the intervention, two identical (to provide choice of participation times) digital information sessions were held, a private Facebook group was used for communication and support throughout the 8-week intervention. Participants were allowed to self-select an early or late eating window. Flexibility to switch between early and late schedules during the intervention period was permitted to enhance feasibility and adherence, provided that the prescribed daily fasting duration was maintained. During fasting, participants were instructed to consume only water and coffee/tea without milk and sweeteners. The use of sugar-free gum, lozenges, and snuff was discouraged but did not constitute an exclusion criterion. Within the eating window, participants were encouraged to eat to satiety without energy restrictions, and to consume fewer, larger meals to limit snacking. Maintenance of body weight was an explicit objective of the intervention and was emphasized throughout the study period.

Data collection and Statistical Analyses

Data were collected using secure online questionnaires at baseline and post-intervention, administered via Nettskjema, a secure digital survey platform. The severity of symptoms was assessed using the IBS Symptom Severity Scale (IBS-SSS) from a validated Norwegian translation of the IBS-SSS, approved by the Rome Foundation [

29], where questionnaire items are categorized into domains that assess pain, bloating, bowel habits, and quality of life, yielding a total IBS-SSS score ranging from 0 to 0-500. Within the range of the score, 75–175 is considered mild, 17 5–300 moderate and > 300 severe, respectively. Participants also self-evaluated their physical and mental health according to 1-10 Likert scales. All questionnaire items were mandatory, with the exception of body weight. No data imputation was performed. Analyses were conducted using complete cases only, including participants who completed both baseline and follow-up assessments (per-protocol analysis). Analyses were performed using STATA v18. Continuous variables were assessed for normality using (Shapiro-Wilk test). Paired t-tests were applied to normally distributed data, and Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used otherwise. Changes in the IBS-SSS were examined for the total sample and IBS subtype. Baseline characteristics are reported as mean ± SD or median (IQR). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

134 of the invited participants completed the pre-intervention questionnaire and were enrolled in the study. During the 8-week intervention, 37 participants discontinued participation: 11 with reasons provided and 26 without. A total of 97 participants completed the post intervention questionnaire and were included in the final analysis.

3.1. Participant characteristics

Of the 97 participants, 90 (92.8%) were women and 7 (7.2%) were men (

Table 1). The mean age was 42.5 (SD 12.9). Most of the participants had mixed IBS subtype (42.3%), followed by constipation (29.9%), diarrhea (21.7%), and unclassified type (6.2%).

3.2. Results at 8 Weeks

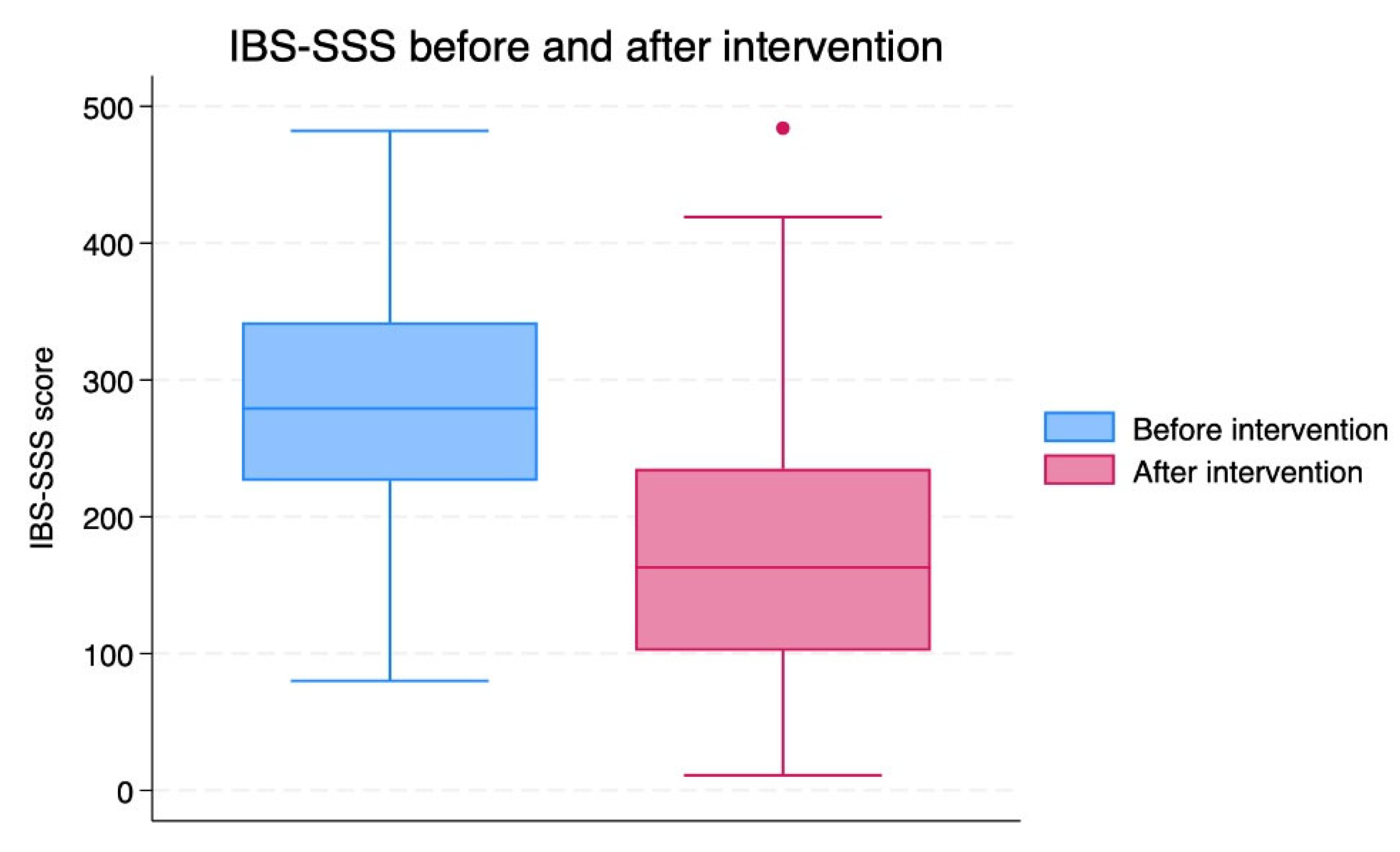

The total IBS-SSS score was reduced after 8 weeks of TRE (p<0.001;

Table 2,

Figure 3). The mean change in the IBS-SSS score was -100.2 [SD 112.3].

Subgroup analyses indicated that participants with IBS-C exhibited the most significant improvements, with a mean decrease in the total score of -125 (SD 117.9) (p<0.001) for within-group pre–post change (

Table 3), followed by participants with IBS-M and IBS-D, -93.1 (SD 107.4) (p<0.001), and -76 (SD 100.4) (p <0.005), respectively. In contrast, there was no statistically significant change in the small IBS-U group (n=6; data not shown).

Sixty participants (61.9%) exhibited a reduction of ≥50 points, indicating a clinically significant improvement [

31]. Based on the total symptom scores, 12 individuals (12.4%) met the criteria for remission after eight weeks (

Table 4). Post-intervention, 39 (40.2%) patients were classified within the mild severity range compared to 15 (15.5%) at baseline. The proportion of individuals with moderate severity decreased slightly from 44 (45.5%) before intervention to 36 (37.1%) after intervention. Notably, the number of participants with severe severity decreased from 38 (39.2%) at baseline to 10 (10.3%) following the intervention (

Table 4).

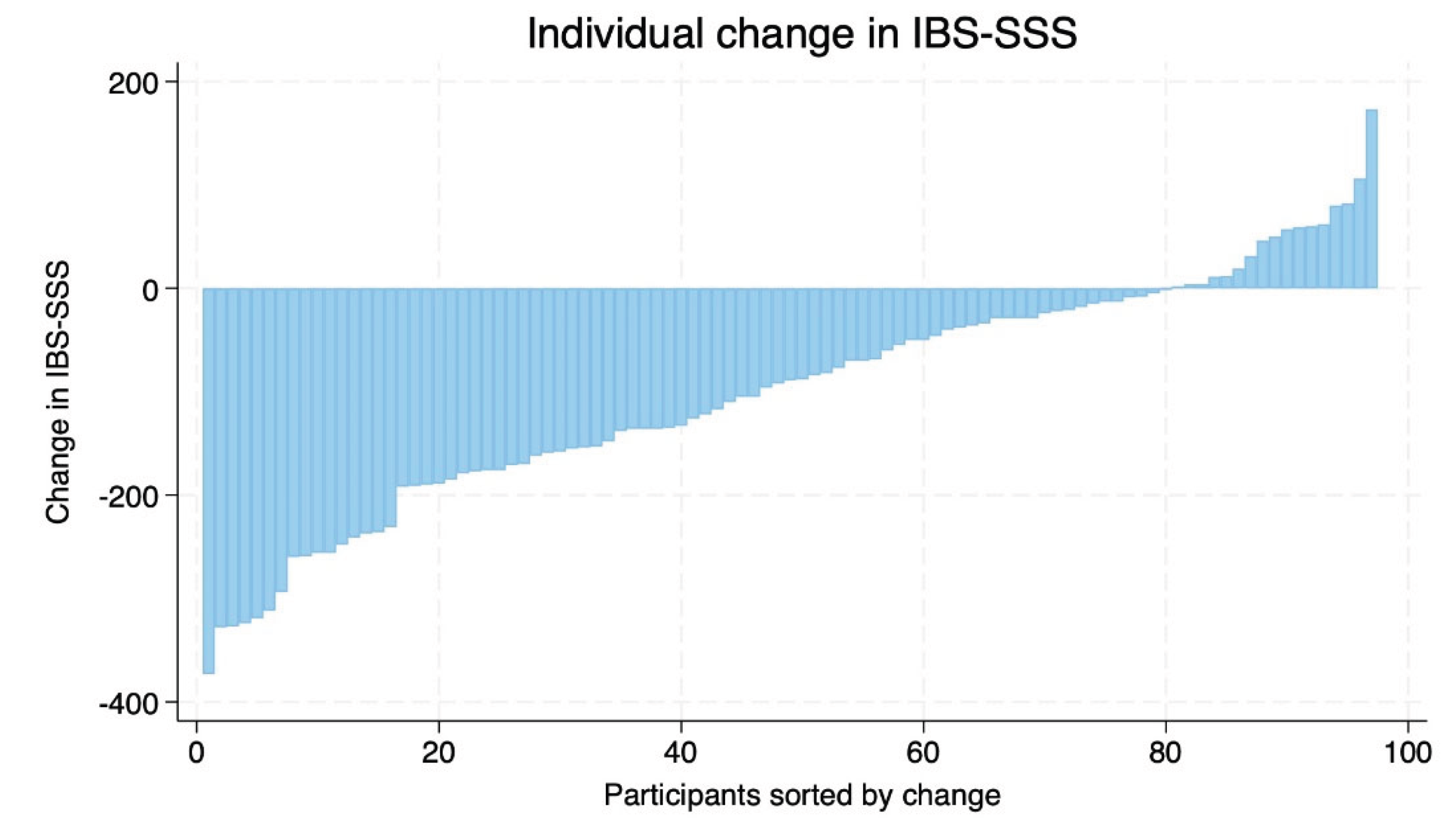

There was considerable inter-individual variability in response to the intervention. While most participants demonstrated improvements, a smaller number of participants exhibited minimal change or worsening of symptoms (

Figure 4).

Self-reported physical and mental health scores increased modestly but significantly from baseline to after intervention. Mean physical health improved from 6.2 (SD 1.6) to 6.7 (SD 1.6) and mean mental health from 6.7 (SD 2.0) to 7.0 (SD 1.7), corresponding to modest but statistically significant changes (p < 0.05 for both).

Body weight changed modestly during the intervention. Twenty-eight participants maintained stable weight, 20 experienced an increase in BMI, and 48 showed a reduction. The mean change in body weight across all participants was −0.71 kg.

3.3. Results at Follow-up (12 Months)

At 12-month follow-up, 58 participants (59.8%) responded to a digital questionnaire assessing IBS symptoms, self-reported physical and psychological health, and current practice of TRE.

Of these, 43 (74.2%) answered “yes” (n = 23) or “partly” (n = 20) to the question: “Are you practicing any form of time-restricted eating at the moment”? Most practiced 16:8 (n = 18) or 14:10 (n = 15) with flexibility during weekends and holidays. Six participants practiced 16:8 TRE, as in the intervention, and four practiced other forms of TRE. Of those not continuing with TRE, or only partly continuing with TRE, reasons are given in

Table 5.

The mean IBS-SSS-scores for this subgroup (n = 58) answering the follow-up survey was 287.8 (SD 85.5) at baseline, reduced significantly to 178.4 (SD 102.6; p < 0.001) after the intervention. At 12 months follow-up the mean IBS-SSS score was 207.3 (SD 103.5), and even though the score was higher than after the intervention, there still was a significant reduction from baseline (p < 0.001).

Regarding self-reported physical health, the scores in this subgroup (n = 58) was 6.07 (SD 1.59) at baseline, increased significantly to 6.69 (SD 1.72; p = 0.003) after the intervention. At 12-month follow-up the self-reported physical health score was 6.60 (SD 1.65), which still was a significant increase from baseline (p = 0.036). For self-reported psychological health, the scores in this subgroup (n = 58) were 6.53 (SD 2.13) at baseline increased significantly to 6.98 (SD 1.90; p = 0.031) after the intervention. At 12 months follow-up the self-reported psychological health score was 6.93 (SD 1.87), not a significant increase from baseline, however a trend (p = 0.069).

In the follow-up questionnaire, 43 participants provided open-ended responses regarding whether TRE had contributed to additional health effects beyond improvements in IBS symptoms. Several recurring themes emerged. The most frequently reported benefit was improved sleep, mentioned by 37% of respondents, followed by better weight regulation (including weight loss or greater weight stability) reported by 30%. Participants also frequently described reductions in musculoskeletal or general bodily pain (19%), improvements in mood or emotional balance (16%), increased energy levels (16%), and enhanced appetite regulation with fewer cravings (12%).

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this pilot study is the first to evaluate the efficacy of TRE as a potential adjunct IBS treatment. Using the validated IBS-SSS questionnaire, we observed clinically meaningful reductions in symptom severity, along with improvements in self-reported physical and mental health. Notably, patients with IBS-C showed the largest decrease in IBS-SSS scores.

Study Design and Feasibility

We conducted a single-group, pre–post intervention pilot study, in which participants with IBS underwent an 8-week time-restricted eating regimen. Outcomes were assessed at baseline and after the intervention to explore their potential efficacy. Participants were allowed to select either early or late TRE while maintaining a 16-hour fasting window – a flexible approach that was meant to facilitate high retention. The retention rate at the end of the intervention also suggests that the dietary protocol was feasible for most participants, indicating that this meal timing approach may be useful for a broader population of individuals with IBS. Additionally, the participants reported that the Facebook group created a sense of community and allowed them to share experiences and support each other throughout the study. This social support may have contributed to the high level of study completion, as shown by Kestyüs and colleagues [

32]. The absence of dietary restrictions and financial costs further supports its potential as a sustainable lifestyle intervention. The single-group design without a control arm limits causal inference, and the duration restricts conclusions to short-term effects. However, the follow-up at 12 months indicated long-term effects of the intervention.

Comparison with Existing Literature

As there are currently no published studies investigating the use of TRE in IBS populations, direct comparisons with existing studies are not possible. The only study that has examined the effects of fasting on IBS symptoms was conducted by Kanazawa et al. In this study, the participants underwent a 10-day water fast, followed by 5 days of refeeding. The study demonstrated a reduction in certain symptoms in patients with IBS-D, however with a more extreme form of fasting than TRE [

33]. As this trial evaluated effects via the Bristol stool scale, and not the IBS-SSS, a direct comparison is not feasible.

Comparison with Dietary Approaches – IBS Symptoms

We observed a mean reduction in IBS-SSS score of -100.2, which is comparable to reductions reported in studies evaluating dietary interventions such as the low-FODMAP diet, gluten-free diets, low-carbohydrate dietary approaches, as well as diet combined with standard dietary advice [

31]. A 2024 systematic review and meta-analysis examined 23 studies comparing low-FODMAP diets and gluten-free diets to standard diets in patients with IBS [

34]. Included studies varied in duration (3-12 weeks), and some focused exclusively on the IBS-D population. In studies comparing a low FODMAP diet with standard dietary advice, the low FODMAP diet was associated with greater reductions in IBS symptom severity, as measured by the IBS-SSS [

34]. In contrast, comparisons between gluten-free diets and standard diets did not show statistically significant changes in IBS-SSS scores [

34]. The ability of av very low carbohydrate diet to reduce symptoms in patients with IBS-D [

16] could be attributed to the exclusion of certain FODMAPs; however, it is also possible that the anti-inflammatory effect of ketone bodies contributes to symptom improvement [

26,

28]. Although our pilot study cannot be directly compared to any of these randomized controlled trials; the finding that reductions in symptoms were comparable to more established treatment options suggest that further investigation into TRE as a potential treatment for IBS is warranted.

Comparison with Dietary Approaches – Quality of Life

Existing studies have compared dietary interventions in relation to quality of life using the Irritable Bowel Syndrome Quality of Life Instrument (IBS-QOL), and improvements have been reported from both from low FODMAP diets and Mediterranean diets [

34]. Notably, Mediterranean diets demonstrate a greater improvement in quality of life than more restrictive approaches, including low FODMAP diets, gluten-free diets, low-carbohydrate diets, and a combination of low FODMAP diets with fiber supplementation [

34]. This finding is somewhat unexpected, as Mediterranean diets do not impose restrictions based on gastrointestinal symptom triggers [

35], contrasting other therapeutic dietary approaches. Instead, Mediterranean diets are characterized by high overall dietary quality and greater flexibility, suggesting that a less restrictive dietary approach may contribute positively to quality of life [

35]. Flexibility in food choice is also a defining characteristic of time-restricted eating, which does not restrict specific food types and may therefore support quality of life.

Although a small reduction in body weight was observed in a subset of participants, it is unclear whether changes in BMI contributed meaningfully to symptom improvement. Evidence on the relationship between weight loss and symptom severity in individuals with IBS is limited. A prospective cohort study in individuals with severe obesity suggested that substantial weight reduction may be associated with improvements in IBS symptoms [

36]. However, the participants in that study had markedly higher baseline BMI compared with the present study, limiting the generalizability of those findings to populations with normal weight or moderate overweight. Furthermore, the symptom improvement observed among individuals who lost weight may reflect qualitative changes in diet during the weight-loss phase rather than weight reduction per se. It remains unclear whether participants in our study who lost weight simply reduced portion sizes of their habitual foods or whether they made more substantial alterations to their dietary composition. Improvements in dietary quality - such as increased intake of whole and minimally processed foods, combined with reduced consumption of ultra-processed products - may influence gastrointestinal symptoms [

19,

37]. Accordingly, changes in diet quality could represent a significant confounding factor when interpreting the relationship between BMI reduction and symptom improvement in IBS. Given that the study did not aim to evaluate the effects of weight change, the observed BMI shifts should be interpreted cautiously and considered an exploratory finding.

An important consideration when interpreting our findings relates to the timing of the eating window. Previous studies have suggested that early time-restricted eating (eTRE) may confer greater metabolic benefits than late time-restricted eating (lTRE), potentially due to closer alignment with circadian rhythms [

38,

39], however the evidence is still inconclusive. The primary objective of the present study was to examine whether time-restricted eating, as a general behavioral strategy, could be beneficial irrespective of the timing of the eating window. Accordingly, participants were allowed to self-select either an early or late eating window and to alternate between these approaches as needed to facilitate integration into daily life. If implemented in clinical practice, this flexible approach to time-restricted eating may represent a low-cost and pragmatic strategy that can be adapted to individual preferences and life circumstances. In the present study, a 16:8 protocol was applied; however, it is plausible that less restrictive regimens (e.g., 15:9 or 14:10) could also be beneficial for individuals with IBS, provided that they extend the habitual fasting duration.

Individual Differences

Although most participants experienced improvements in symptoms, a subset reported symptom worsening. This finding underscores substantial interindividual variability in response to time-restricted eating, suggesting that underlying biological or behavioral factors may modulate the efficacy of this intervention in patients with IBS. Such heterogeneity highlights the need for more personalized approaches to IBS management and reinforces the importance of expanding the therapeutic toolbox available to clinicians.

Self-Reported Physical and Mental Health

Given the well-established burden from comorbidities, improvements in gastrointestinal symptoms may be accompanied by changes in physical and mental well-being. In this study, modest but statistically significant improvements were observed in self-reported physical and mental health following the 8-week intervention. Although these measures were exploratory and based on non-validated scales, the findings suggest that future studies should consider including validated instruments to more comprehensively assess changes in physical and psychological health. Despite considerable inter-individual variability, the qualitative findings from open-ended questions in the follow-up survey suggest that TRE may confer benefits for co-morbid symptoms frequently reported in IBS. These observations should be interpreted strictly as hypothesis-generating, given that the follow-up was exploratory, not pre-specified, and relied on self-reported qualitative data.

Potential Mechanisms

Biological pathways that may mediate the observed effects include fasting-induced modulation of the migrating motor complex [

22], metabolic switching with ketogenesis and activation of autophagy [

21,

23,

25], modulation of the gut microbiota [

24] and broader cellular and tissue-level responses [

19,

26,

27,

28]. While these mechanisms are biologically plausible - particularly given their overlap with pathophysiological processes implicated in IBS, such as impaired motility, low-grade inflammation, epithelial barrier dysfunction, and dysbiosis - this pilot study was not designed to investigate mechanistic pathways. Accordingly, any proposed explanations should be interpreted with caution. Nevertheless, the alignment between fasting-induced biological responses and established IBS-related mechanisms highlights the need for future mechanistic studies to directly examine how time-restricted eating may influence gastrointestinal function and symptom generation in IBS.

Clinical Implications and Future Research

Our findings suggest that time-restricted eating represents a simple, cost-free, and feasible approach to IBS symptom management. Its inherent flexibility may facilitate integration into a wide range of everyday life contexts, potentially empowering patients to take an active role in managing their gastrointestinal symptoms.

However, to establish the efficacy, sustainability, and underlying mechanisms of time-restricted eating in IBS, future studies should employ more rigorous designs, including randomized controlled trials with longer follow-up periods. Such studies should incorporate validated measures of quality of life and mental and physical health, objective biological markers (e.g., high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) and fecal calprotectin), and gut microbiota profiling. Objective assessments of dietary adherence, potentially including continuous glucose monitoring, should also be considered. In addition, future research should evaluate whether habitual dietary patterns are maintained over time and examine the applicability of time-restricted eating in populations excluded from the present pilot study, including individuals with conditions that produce IBS-like symptoms.

Limitations

Our sample was predominantly female and recruited through the Norwegian Gastrointestinal Association and social media, introducing potential sex and selection bias. The participants were self-selected and highly motivated, which may have contributed to positive expectancy effects. Symptom assessment relied on self-reporting, raising concerns of subjectivity, placebo and Hawthorne effects and unmeasured confounding factors such as concurrent dietary changes. Compliance was not objectively monitored, and changes in BMI may have influenced outcomes. As this is the first study to investigate the potential effect of TRE on IBS symptoms, it was not possible to perform an a priori power calculation. Although participant recruitment was relatively successful, the lack of power calculations introduces uncertainty regarding the reliability and generalizability of the finding. Post hoc analysis using Cohen’s d revealed an effect size of 0.89, which may indicate a meaningful practical and clinical benefit of TRE in individuals with IBS.

5. Conclusions

In this pilot study, an 8-week TRE regimen was associated with clinically meaningful improvements in the IBS symptom severity scores. These findings suggest that TRE may represent a feasible, cost-free dietary approach that does not impose restrictions on food types or energy intake and may therefore be suitable for symptom management in patients with IBS. Future intervention trials with longer follow-up periods and objective outcome measures are warranted to confirm efficacy and elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.T.C., A.B., H.S., M.K. and M.M.; methodology, M.T.C., A.B., M.K. and M.M.; formal analysis, M.T.C.; investigation, M.T.C.; writing—original draft preparation, M.T.C.; writing—review and editing, M.T.C., A.B., H.S., M.K. and M.M.; visualization, M.T.C.; supervision, A.B., M.K. and M.M.; project administration, M.K.; funding acquisition, M.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Kristiania University College of Applied Sciences, which provided the first author with a three-month salary to facilitate the transformation of the master’s thesis into a scientific article. Their involvement in the process was limited solely to providing financial support.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by SIKT (project number: 942235) and the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics (REK) (project number: 744378). The pilot study was preregistered in the Open Science Framework [

30].

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Due to ethical and privacy considerations, the data are not publicly available. De-identified data may be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants who enthusiastically joined the pilot study and made this inquiry possible. We would also like to give thanks to the Norwegian gastrointestinal association for their extensive support with project publicity and participant recruitment.

Conflicts of Interest

M.K. is the author of a popular science book addressing time-restricted eating and receives royalties from book sales. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Use of Artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence–based language assistance (ChatGPT, OpenAI) was used to improve the clarity, structure, and readability of the manuscript after initial drafting. All content was critically reviewed, edited, and approved by the authors, who take full responsibility for the manuscript.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BMI |

Body mass index |

| hs-CRP |

High sensitive C-reactive protein |

| FMT |

Fecal microbiota transplantation |

FODMAP

IBS |

Fermentable Oligo-, Di-, Monosaccharides and Polyols

Irritable bowel syndrome |

| IBS-SSS |

Irritable bowel syndrome symptom severity scale |

| IBS-C |

Irritable bowel syndrome (Constipation) |

| IBS-D |

Irritable bowel syndrome (Diarrhea) |

| IBS-M |

Irritable bowel syndrome (Mixed) |

| IBS-U |

Irritable bowel syndrome (Unclassified) |

| REK |

Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics |

| TRE |

Time-restricted eating |

| eTRE |

Early time-restricted eating |

| lTRE |

Late time-restricted eating |

References

- Ford, A.C.; Sperber, A.D.; Corsetti, M.; Camilleri, M. Irritable Bowel Syndrome. The Lancet 2020, 396, 1675–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rome IV Criteria. Rome Foundation. Available online: https://theromefoundation.org/rome-iv/rome-iv-criteria/ (accessed on 22 December 2025).

- Oka, P.; Parr, H.; Barberio, B.; Black, C.J.; Savarino, E.V.; Ford, A.C. Global Prevalence of Irritable Bowel Syndrome According to Rome III or IV Criteria: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 5, 908–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.-Y.; Wang, F.-Y.; Lv, M.; Ma, X.-X.; Tang, X.-D.; Lv, L. Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Epidemiology, Overlap Disorders, Pathophysiology and Treatment. World J. Gastroenterol. 2023, 29, 4120–4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperber, A.D.; Bangdiwala, S.I.; Drossman, D.A.; Ghoshal, U.C.; Simren, M.; Tack, J.; Whitehead, W.E.; Dumitrascu, D.L.; Fang, X.; Fukudo, S.; et al. Worldwide Prevalence and Burden of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders, Results of Rome Foundation Global Study. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 99–114.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IFFGD’s IBS Patients’ Illness Experience and Unmet Needs Survey - IFFGD. Available online: https://iffgd.org/news/press-release/2020-iffgd-s-ibs-patients-illness-experience-and-unmet-needs-survey/ (accessed on 24 March 2025).

- Shiha, M.G.; Aziz, I. Review Article: Physical and Psychological Comorbidities Associated with Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 54 Suppl.1, S12–S23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canavan, C.; West, J.; Card, T. Review Article: The Economic Impact of the Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014, 40, 1023–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Salhy, M.; Johansson, M.; Klevstul, M.; Hatlebakk, J.G. Quality of Life, Functional Impairment and Healthcare Experiences of Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome in Norway: An Online Survey. BMC Gastroenterol. 2025, 25, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carabotti, M.; Scirocco, A.; Maselli, M.A.; Severi, C. The Gut-Brain Axis: Interactions between Enteric Microbiota, Central and Enteric Nervous Systems. Ann. Gastroenterol. Q. Publ. Hell. Soc. Gastroenterol. 2015, 28, 203–209. [Google Scholar]

- Raskov, H.; Burcharth, J.; Pommergaard, H.-C.; Rosenberg, J. Irritable Bowel Syndrome, the Microbiota and the Gut-Brain Axis. Gut Microbes 2016, 7, 365–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzaei, M.H.; Bahramsoltani, R.; Abdollahi, M.; Rahimi, R. The Role of Visceral Hypersensitivity in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Pharmacological Targets and Novel Treatments. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2016, 22, 558–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittayanon, R.; Lau, J.T.; Yuan, Y.; Leontiadis, G.I.; Tse, F.; Surette, M.; Moayyedi, P. Gut Microbiota in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome—A Systematic Review. Gastroenterology 2019, 157, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holtmann, G.J.; Ford, A.C.; Talley, N.J. Pathophysiology of Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016, 1, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staudacher, H.M.; Irving, P.M.; Lomer, M.C.E.; Whelan, K. Mechanisms and Efficacy of Dietary FODMAP Restriction in IBS. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014, 11, 256–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, G.L.; Dalton, C.B.; Hu, Y.; Morris, C.B.; Hankins, J.; Weinland, S.R.; Westman, E.C.; Yancy, W.S.; Drossman, D.A. A Very Low-Carbohydrate Diet Improves Symptoms and Quality of Life in Diarrhea-Predominant Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Off. Clin. Pract. J. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc. 2009, 7, 706–708.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamshidi, P.; Farsi, Y.; Nariman, Z.; Hatamnejad, M.R.; Mohammadzadeh, B.; Akbarialiabad, H.; Nasiri, M.J.; Sechi, L.A. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 14562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koppold, D.A.; Breinlinger, C.; Hanslian, E.; Kessler, C.; Cramer, H.; Khokhar, A.R.; Peterson, C.M.; Tinsley, G.; Vernieri, C.; Bloomer, R.J.; et al. International Consensus on Fasting Terminology. Cell Metab. 2024, 36, 1779–1794.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolby, M.; Brevik, A.; Dale, H.F.; Molin, M.; Valeur, J. Intermittent Fasting as a Potential Therapeutic Approach for Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Mechanistic Perspective. Preprints 2025, 2025091043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkey, K.A.; Mawe, G.M. The Enteric Nervous System. Physiol. Rev. 2023, 103, 1487–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagherniya, M.; Butler, A.E.; Barreto, G.E.; Sahebkar, A. The Effect of Fasting or Calorie Restriction on Autophagy Induction: A Review of the Literature. Ageing Res. Rev. 2018, 47, 183–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deloose, E.; Janssen, P.; Depoortere, I.; Tack, J. The Migrating Motor Complex: Control Mechanisms and Its Role in Health and Disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012, 9, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, N.; Gupta, S. Biochemistry, Ketogenesis. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ducarmon, Q.R.; Grundler, F.; Le Maho, Y.; et al. Remodelling of the Intestinal Ecosystem during Caloric Restriction and Fasting. Trends Microbiol. 2023, 31, 832–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haq, S.; Grondin, J.; Banskota, S.; Khan, W.I. Autophagy: Roles in Intestinal Mucosal Homeostasis and Inflammation. J. Biomed. Sci. 2019, 26, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Xu, H.; Li, C.; Yang, H.; Mao, Y. Intermittent Fasting and Immunomodulatory Effects: A Systematic Review. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1048230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larabi, A.; Barnich, N.; Nguyen, H.T.T. New Insights into the Interplay between Autophagy, Gut Microbiota and Inflammatory Responses in IBD. Autophagy 2019, 16, 38–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, V.D.; Mattson, M.P. Fasting: Molecular Mechanisms and Clinical Applications. Cell Metab. 2014, 19, 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, C.Y.; Morris, J.; Whorwell, P.J. The Irritable Bowel Severity Scoring System: A Simple Method of Monitoring Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Its Progress. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 1997, 11, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molin, M. Time-Restricted Eating (TRE) for Symptom Relief in Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS). Open Science Framework (OSF) Preregistration. 22 December 2025. Available online: https://osf.io/9bfxa.

- Nybacka, S.; Törnblom, H.; Josefsson, A.; et al.; 31 A Low FODMAP Diet plus Traditional Dietary Advice versus a Low-Carbohydrate Diet versus Pharmacological Treatment in Irritable Bowel Syndrome (CARIBS): A Single-Centre, Single-Blind, Randomised Controlled Trial. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. accessed on. 9, 507–520. (accessed on 2024). [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesztyüs, D.; Cermak, P.; Gulich, M.; Kesztyüs, T. Adherence to Time-Restricted Feeding and Impact on Abdominal Obesity in Primary Care Patients: Results of a Pilot Study in a Pre–Post Design. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanazawa, M.; Fukudo, S. Effects of Fasting Therapy on Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Int. J. Behav. Med. 2006, 13, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haghbin, H.; Hasan, F.; Gangwani, M.K.; Zakirkhodjaev, N.; Lee-Smith, W.; Beran, A.; Kamal, F.; Hart, B.; Aziz, M. Efficacy of Dietary Interventions for Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 7531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, C.; Bryan, J.; Hodgson, J.; Murphy, K. Definition of the Mediterranean Diet; A Literature Review. Nutrients 2015, 7, 9139–9153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aasbrenn, M.; Lydersen, S.; Farup, P.G. A Conservative Weight Loss Intervention Relieves Bowel Symptoms in Morbidly Obese Subjects with Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Obes. 2018, 2018, 3732753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Yang, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, S.; Zhu, S. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Long-Term Risk of Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Large-Scale Prospective Cohort Study. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2024, 22, 1497–1507.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, E.F.; Beyl, R.; Early, K.S.; Cefalu, W.T.; Ravussin, E.; Peterson, C.M. Early Time-Restricted Feeding Improves Insulin Sensitivity, Blood Pressure, and Oxidative Stress Even without Weight Loss in Men with Prediabetes. Cell Metab. 2018, 27, 1212–1221.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Sun, Y.; Ye, Y.; Hu, D.; Zhang, H.; He, Z.; Zhao, H.; Yang, H.; Mao, Y. Randomized Controlled Trial for Time-Restricted Eating in Healthy Volunteers without Obesity. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |