Submitted:

26 January 2026

Posted:

27 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

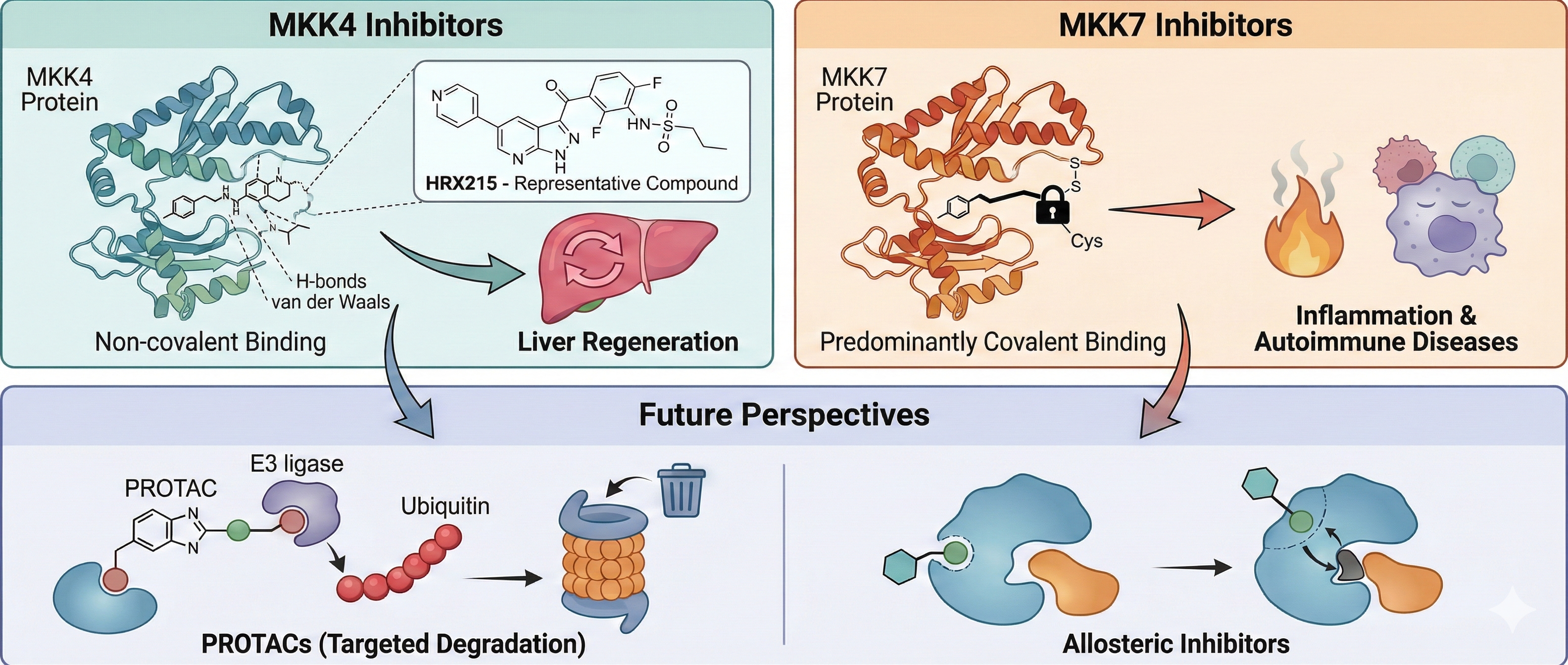

2. The Biological Functions and Therapeutic Potential of MKK4/7

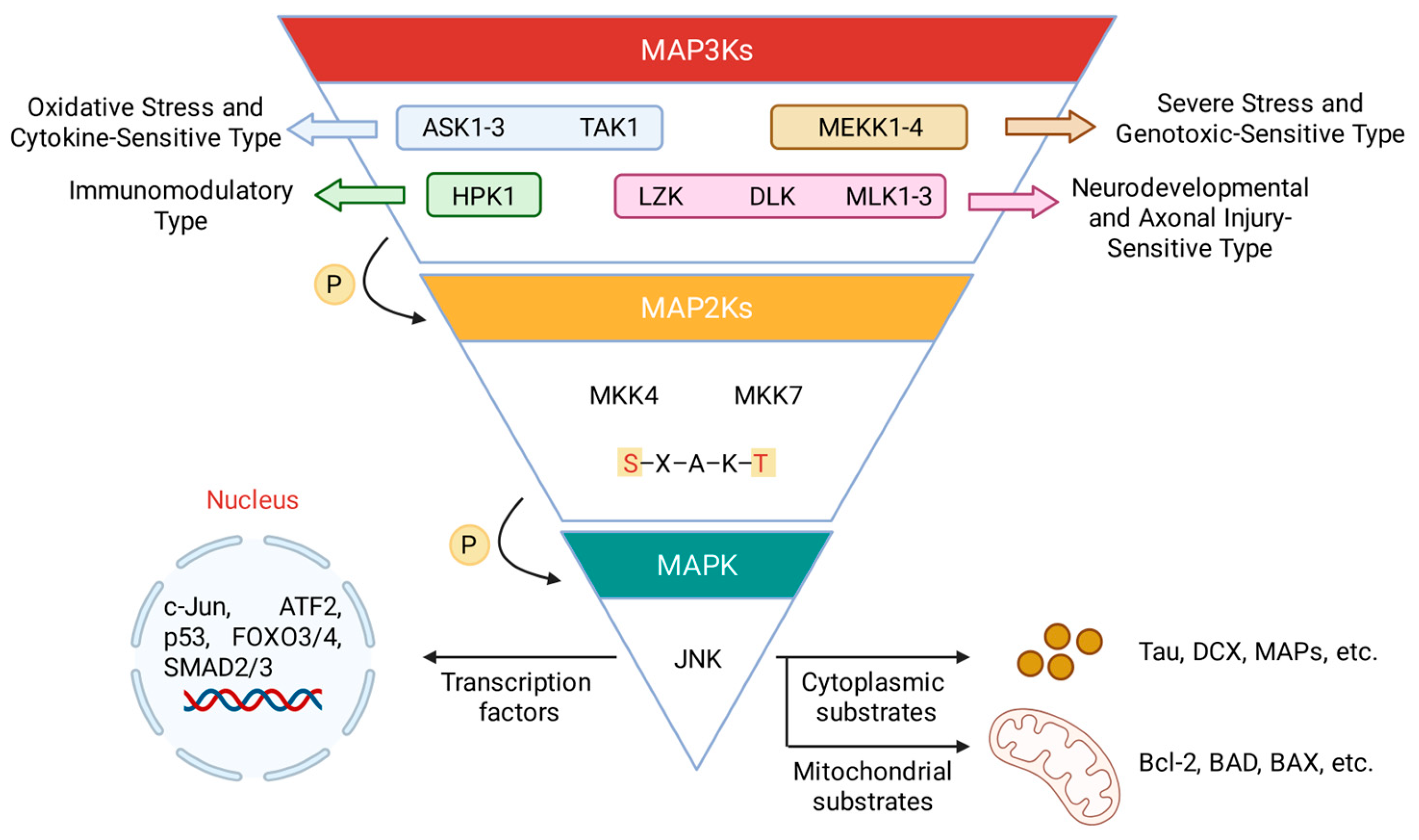

2.1. The JNK Signaling Architecture

2.2. Biological Functions and Therapeutic Potential

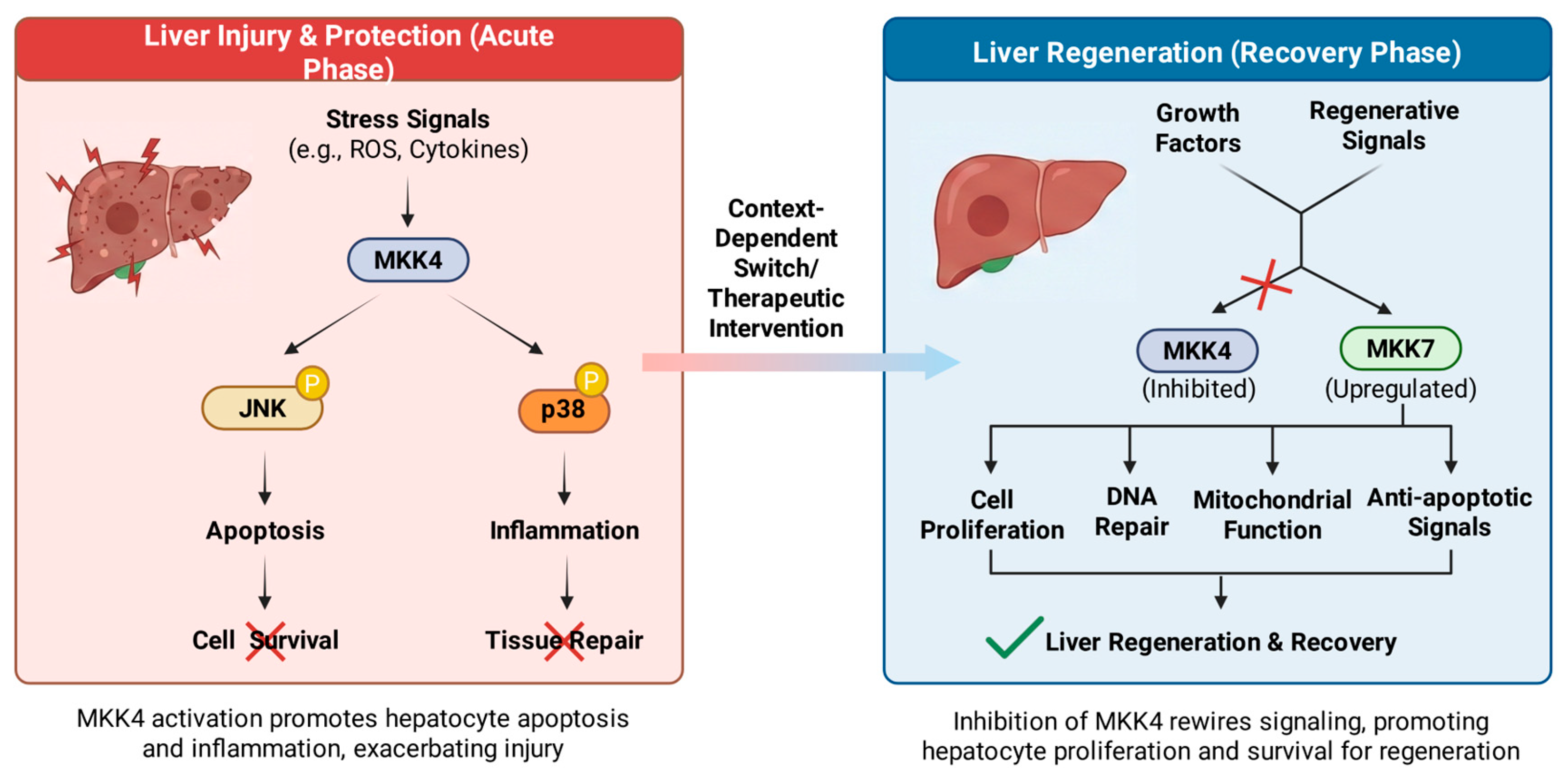

2.2.1. MKK4 in Liver Regeneration and Hepatoprotection

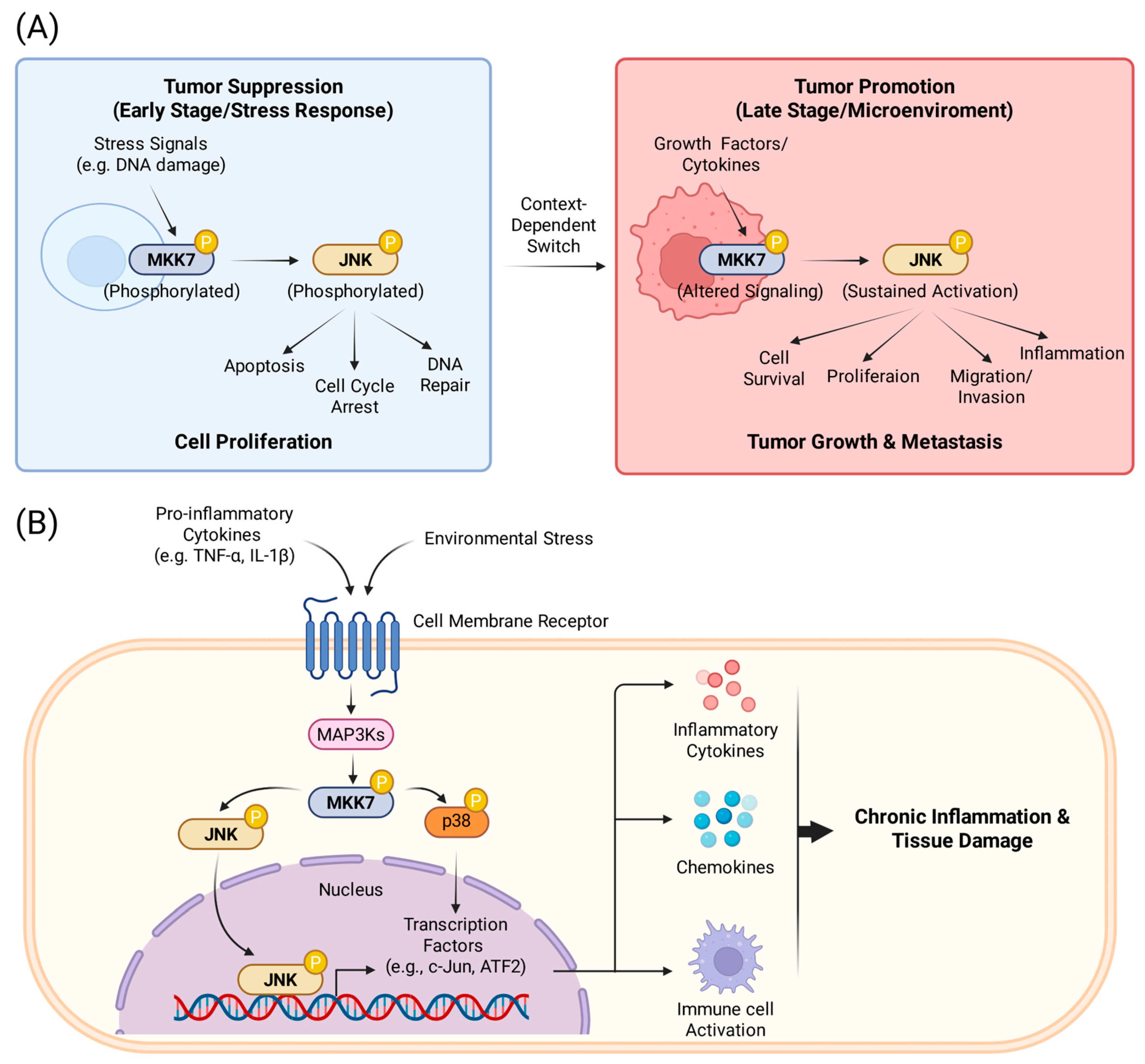

2.2.2. The Role of MKK7 in Cancer

2.2.3. The Role of MKK7 in Inflammation

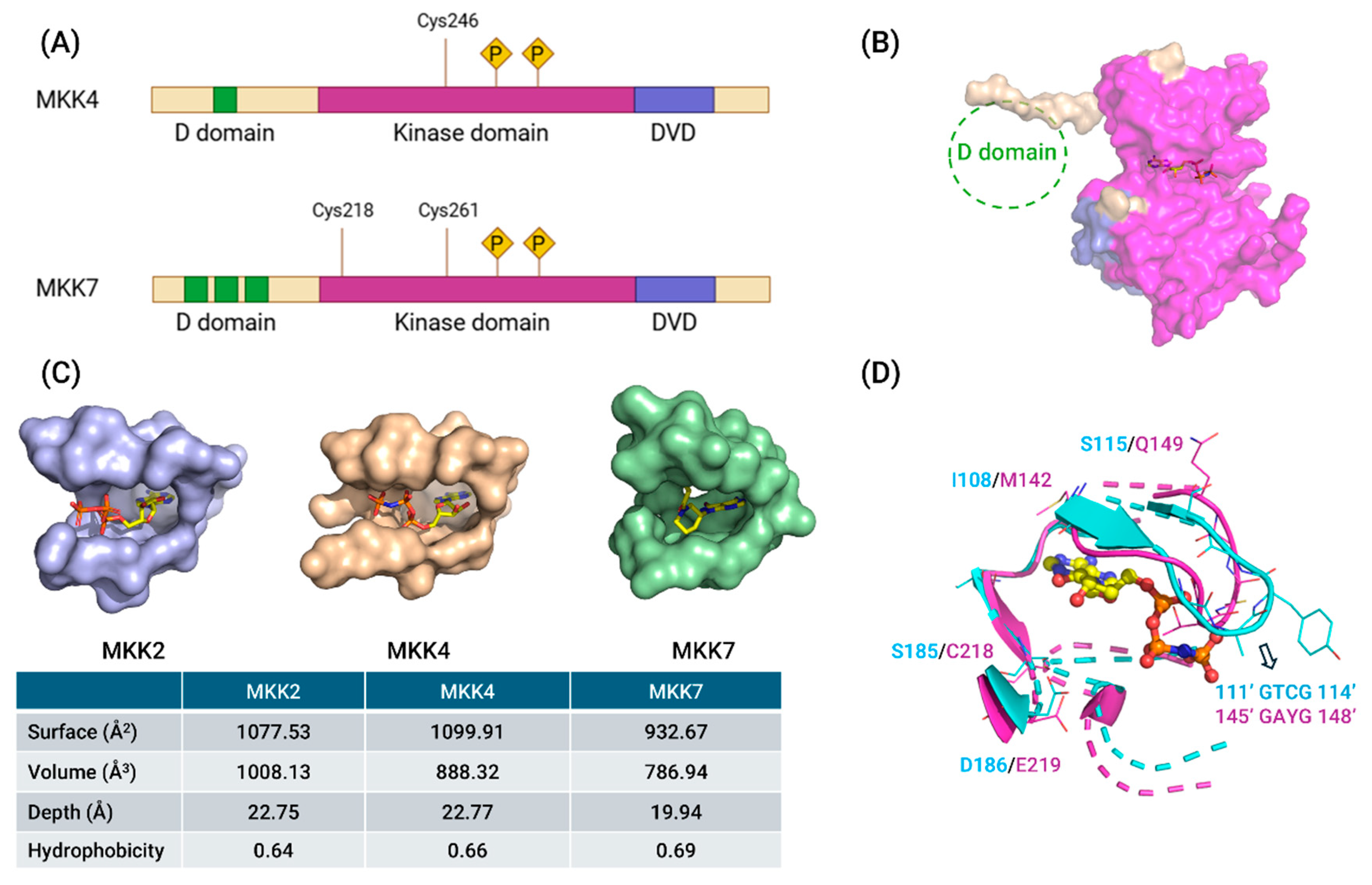

3. Structures of MKK4 and MKK7

4. MKK4 and MKK7 Inhibitors

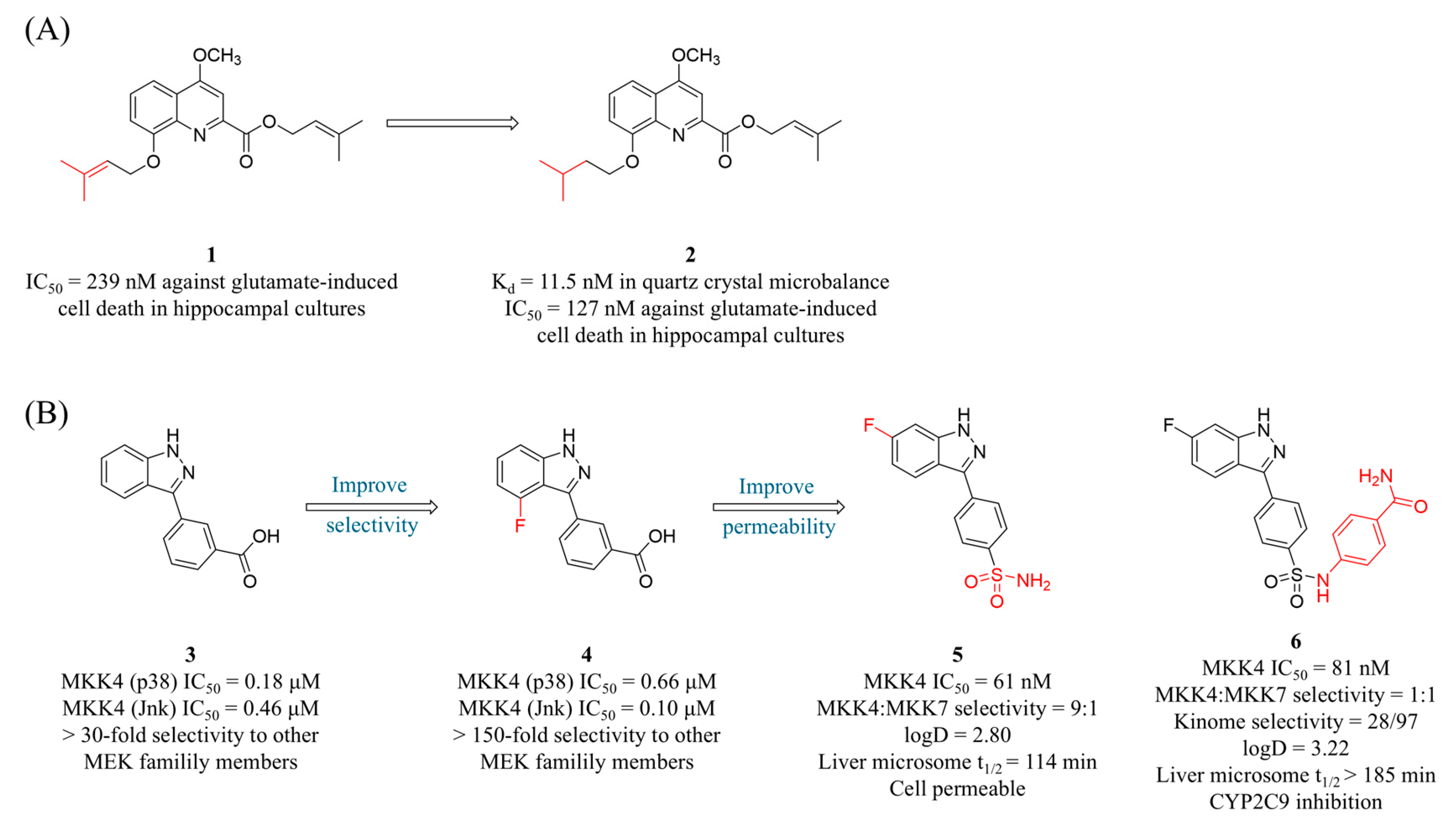

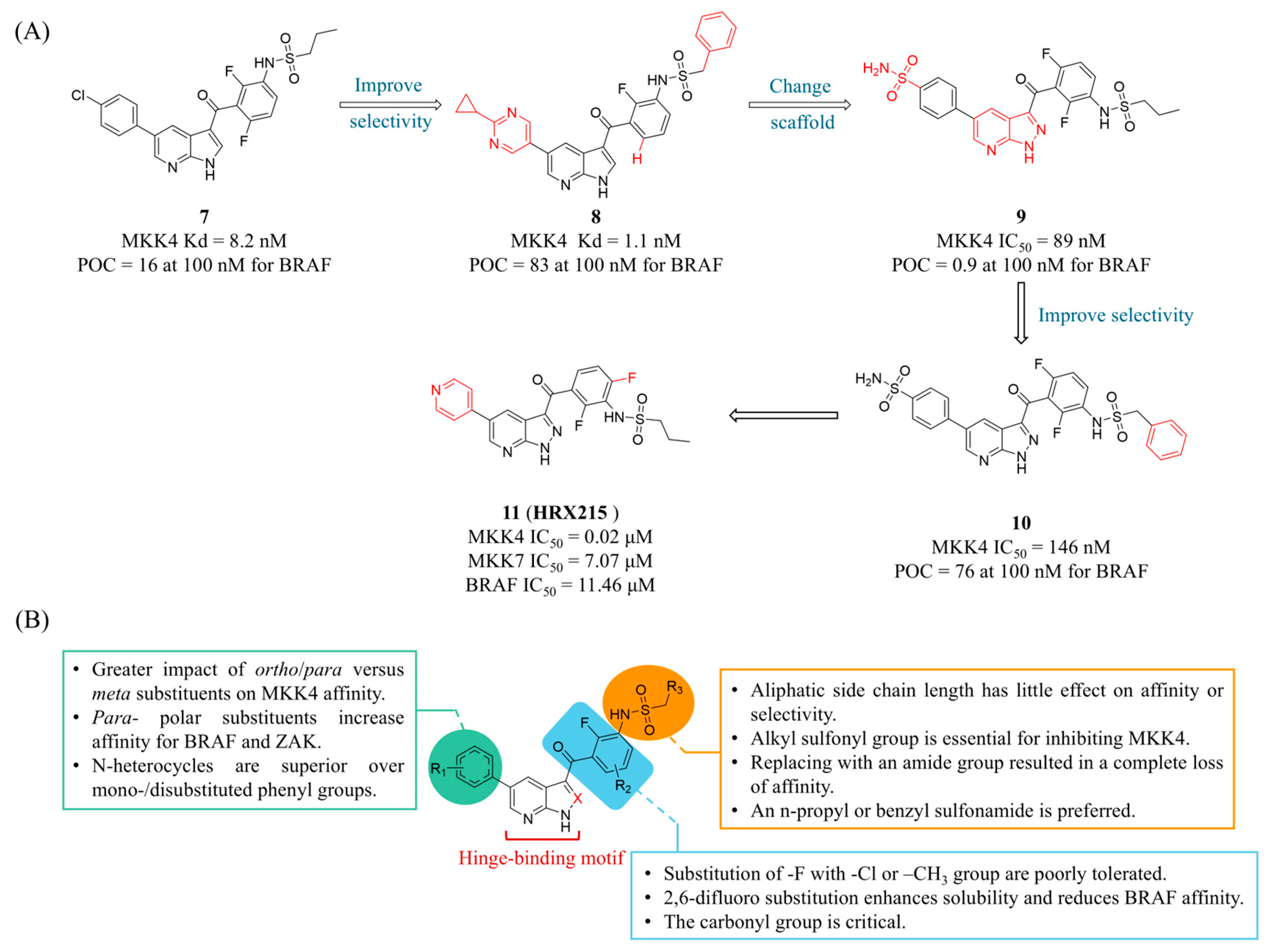

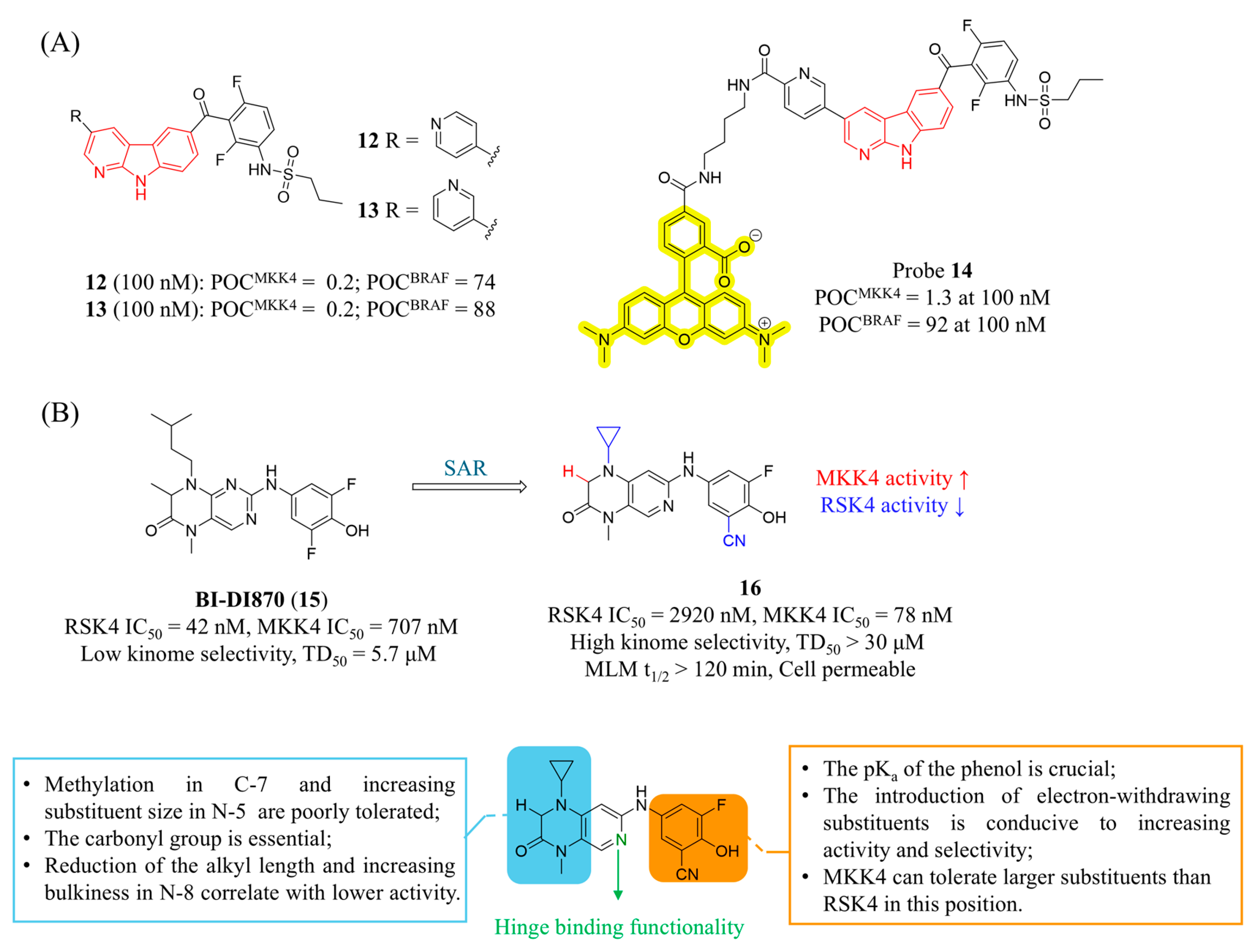

4.1. MKK4 Inhibitors

4.2. MKK7 Inhibitors

4.2.1. Covalent Inhibitors

4.2.2. Other Inhibitors

5. Conclusion and Future Perspectives

Acknowledgments

Abbreviation

References

- Cargnello, M.; Roux, P.P. Activation and function of the MAPKs and their substrates, the MAPK-activated protein kinases. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 2011, 75, 50–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atay, O.; Skotheim, J.M. Spatial and temporal signal processing and decision making by MAPK pathways. J Cell Biol 2017, 216, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarza, R.; Vela, S.; Solas, M.; Ramirez, M.J. c-Jun N-terminal Kinase (JNK) Signaling as a Therapeutic Target for Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Pharmacol 2015, 6, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, M.; Lu, Y.; Yao, Z.; Wang, P.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, L.; Yang, Q.; Sang, X.; Wang, K.; Cao, G. The role of JNK signaling pathway in organ fibrosis. J Adv Res 2025, 74, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garg, R.; Kumariya, S.; Katekar, R.; Verma, S.; Goand, U.K.; Gayen, J.R. JNK signaling pathway in metabolic disorders: An emerging therapeutic target. Eur J Pharmacol 2021, 901, 174079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Los Reyes Corrales, T.; Losada-Perez, M.; Casas-Tinto, S. JNK Pathway in CNS Pathologies. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; He, L.; Lv, D.; Yang, J.; Yuan, Z. The Role of the Dysregulated JNK Signaling Pathway in the Pathogenesis of Human Diseases and Its Potential Therapeutic Strategies: A Comprehensive Review. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Xiong, Z.; Zou, L.; Jiang, M.; Luo, Z.; Wen, S.; Liu, W.; Liu, S.; Li, W. Involvement of JNK in the embryonic development and organogenesis in zebrafish. Mar Biotechnol (NY) 2013, 15, 716–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Shuai, W.; Zhao, M.; Pan, X.; Pei, J.; Wu, Y.; Bu, F.; Wang, A.; Ouyang, L.; Wang, G. Unraveling the Design and Discovery of c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase Inhibitors and Their Therapeutic Potential in Human Diseases. J Med Chem 2022, 65, 3758–3775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhujbal, S.P.; Hah, J.M. Advances in JNK inhibitor development: therapeutic prospects in neurodegenerative diseases and fibrosis. Arch Pharm Res 2025, 48, 858–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzengruber, L.; Sander, P.; Laufer, S. MKK4 Inhibitors-Recent Development Status and Therapeutic Potential. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, 7495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.G.; Aziz, N.; Cho, J.Y. MKK7, the essential regulator of JNK signaling involved in cancer cell survival: a newly emerging anticancer therapeutic target. Ther Adv Med Oncol 2019, 11, 1758835919875574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kishimoto, H.; Nakagawa, K.; Watanabe, T.; Kitagawa, D.; Momose, H.; Seo, J.; Nishitai, G.; Shimizu, N.; Ohata, S.; Tanemura, S.; Asaka, S.; Goto, T.; Fukushi, H.; Yoshida, H.; Suzuki, A.; Sasaki, T.; Wada, T.; Penninger, J.M.; Nishina, H.; Katada, T. Different properties of SEK1 and MKK7 in dual phosphorylation of stress-induced activated protein kinase SAPK/JNK in embryonic stem cells. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, 16595–16601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lisnock, J.; Griffin, P.; Calaycay, J.; Frantz, B.; Parsons, J.; O’Keefe, S.J.; LoGrasso, P. Activation of JNK3 alpha 1 requires both MKK4 and MKK7: kinetic characterization of in vitro phosphorylated JNK3 alpha 1. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 3141–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawler, S.; Fleming, Y.; Goedert, M.; Cohen, P. Synergistic activation of SAPK1/JNK1 by two MAP kinase kinases in vitro. Curr Biol 1998, 8, 1387–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tournier, C.; Dong, C.; Turner, T.K.; Jones, S.N.; Flavell, R.A.; Davis, R.J. MKK7 is an essential component of the JNK signal transduction pathway activated by proinflammatory cytokines. Genes Dev 2001, 15, 1419–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caliz, A.D.; Vertii, A.; Fisch, V.; Yoon, S.; Yoo, H.J.; Keaney, J.F., Jr.; Kant, S. Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 7 in inflammatory, cancer, and neurological diseases. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10, 979673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasaki, T.; Wada, T.; Kishimoto, H.; Irie-Sasaki, J.; Matsumoto, G.; Goto, T.; Yao, Z.; Wakeham, A.; Mak, T.W.; Suzuki, A.; Cho, S.K.; Zuniga-Pflucker, J.C.; Oliveira-dos-Santos, A.J.; Katada, T.; Nishina, H.; Penninger, J.M. The stress kinase mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MKK)7 is a negative regulator of antigen receptor and growth factor receptor-induced proliferation in hematopoietic cells. J Exp Med 2001, 194, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chen, L.; Ko, C.I.; Zhang, L.; Puga, A.; Xia, Y. Distinct signaling properties of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinases 4 (MKK4) and 7 (MKK7) in embryonic stem cell (ESC) differentiation. J Biol Chem 2012, 287, 2787–2797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Destrument, A.; Tournier, C. Physiological roles of MKK4 and MKK7: insights from animal models. Biochim Biophys Acta 2007, 1773, 1349–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zwirner, S.; Abu Rmilah, A.A.; Klotz, S.; Pfaffenroth, B.; Kloevekorn, P.; Moschopoulou, A.A.; Schuette, S.; Haag, M.; Selig, R.; Li, K.; Zhou, W.; Nelson, E.; Poso, A.; Chen, H.; Amiot, B.; Jia, Y.; Minshew, A.; Michalak, G.; Cui, W.; Rist, E.; Longerich, T.; Jung, B.; Felgendreff, P.; Trompak, O.; Premsrirut, P.K.; Gries, K.; Muerdter, T.E.; Heinkele, G.; Wuestefeld, T.; Shapiro, D.; Weissbach, M.; Koenigsrainer, A.; Sipos, B.; Ab, E.; Zacarias, M.O.; Theisgen, S.; Gruenheit, N.; Biskup, S.; Schwab, M.; Albrecht, W.; Laufer, S.; Nyberg, S.; Zender, L. First-in-class MKK4 inhibitors enhance liver regeneration and prevent liver failure. Cell 2024, 187, 1666–1684 e26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindson, J. Development of MKK4 inhibitors for liver regeneration. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2024, 21, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichijo, H.; Nishida, E.; Irie, K.; ten Dijke, P.; Saitoh, M.; Moriguchi, T.; Takagi, M.; Matsumoto, K.; Miyazono, K.; Gotoh, Y. Induction of apoptosis by ASK1, a mammalian MAPKKK that activates SAPK/JNK and p38 signaling pathways. Science 1997, 275, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirakabe, K.; Yamaguchi, K.; Shibuya, H.; Irie, K.; Matsuda, S.; Moriguchi, T.; Gotoh, Y.; Matsumoto, K.; Nishida, E. TAK1 mediates the ceramide signaling to stress-activated protein kinase/c-Jun N-terminal kinase. J Biol Chem 1997, 272, 8141–8144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Gorospe, M.; Yang, C.; Holbrook, N.J. Role of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase during the cellular response to genotoxic stress. Inhibition of c-Jun N-terminal kinase activity and AP-1-dependent gene activation. J Biol Chem 1995, 270, 8377–8380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takekawa, M.; Tatebayashi, K.; Saito, H. Conserved docking site is essential for activation of mammalian MAP kinase kinases by specific MAP kinase kinase kinases. Mol Cell 2005, 18, 295–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, M.; Dai, T.; Deak, J.C.; Kyriakis, J.M.; Zon, L.I.; Woodgett, J.R.; Templeton, D.J. Activation of stress-activated protein kinase by MEKK1 phosphorylation of its activator SEK1. Nature 1994, 372, 798–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Tu, Z.; Lee, F.S. Mutations in protein kinase subdomain X differentially affect MEKK2 and MEKK1 activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2003, 303, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deacon, K.; Blank, J.L. Characterization of the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4 (MKK4)/c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase 1 and MKK3/p38 pathways regulated by MEK kinases 2 and 3. MEK kinase 3 activates MKK3 but does not cause activation of p38 kinase in vivo. J Biol Chem 1997, 272, 14489–14496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming, Y.; Armstrong, C.G.; Morrice, N.; Paterson, A.; Goedert, M.; Cohen, P. Synergistic activation of stress-activated protein kinase 1/c-Jun N-terminal kinase (SAPK1/JNK) isoforms by mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4 (MKK4) and MKK7. Biochem J 2000, 352, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombard, C.K.; Davis, A.L.; Inukai, T.; Maly, D.J. Allosteric Modulation of JNK Docking Site Interactions with ATP-Competitive Inhibitors. Biochemistry 2018, 57, 5897–5909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolen, B.; Taylor, S.; Ghosh, G. Regulation of protein kinases; controlling activity through activation segment conformation. Mol Cell 2004, 15, 661–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, R.J. Signal transduction by the JNK group of MAP kinases. Cell 2000, 103, 239–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hibi, M.; Lin, A.; Smeal, T.; Minden, A.; Karin, M. Identification of an oncoprotein- and UV-responsive protein kinase that binds and potentiates the c-Jun activation domain. Genes Dev 1993, 7, 2135–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, M.J.; Steer, C.J. Liver Regeneration in Acute on Chronic Liver Failure. Clin Liver Dis 2023, 27, 595–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirth, K.M.; Kizy, S.; Steer, C.J. Liver Regeneration in the Acute Liver Failure Patient. Clin Liver Dis 2018, 22, 269–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wuestefeld, T.; Pesic, M.; Rudalska, R.; Dauch, D.; Longerich, T.; Kang, T.W.; Yevsa, T.; Heinzmann, F.; Hoenicke, L.; Hohmeyer, A.; Potapova, A.; Rittelmeier, I.; Jarek, M.; Geffers, R.; Scharfe, M.; Klawonn, F.; Schirmacher, P.; Malek, N.P.; Ott, M.; Nordheim, A.; Vogel, A.; Manns, M.P.; Zender, L. A Direct in vivo RNAi screen identifies MKK4 as a key regulator of liver regeneration. Cell 2013, 153, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wada, T.; Penninger, J.M. Stress kinase MKK7: savior of cell cycle arrest and cellular senescence. Cell Cycle 2004, 3, 577–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ura, S.; Nishina, H.; Gotoh, Y.; Katada, T. Activation of the c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway by MST1 is essential and sufficient for the induction of chromatin condensation during apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol 2007, 27, 5514–5522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Li, X.; Cao, J.; Zhu, T.; Liang, S.; Du, L.; Cao, M.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Shen, B.; Feng, J.; Zhang, J.; Wang, J.; Jin, J. Components of the JNK-MAPK pathway play distinct roles in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2023, 149, 17495–17509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schramek, D.; Kotsinas, A.; Meixner, A.; Wada, T.; Elling, U.; Pospisilik, J.A.; Neely, G.G.; Zwick, R.H.; Sigl, V.; Forni, G.; Serrano, M.; Gorgoulis, V.G.; Penninger, J.M. The stress kinase MKK7 couples oncogenic stress to p53 stability and tumor suppression. Nat Genet 2011, 43, 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, T.; Saito, H.; Takekawa, M. SAPK pathways and p53 cooperatively regulate PLK4 activity and centrosome integrity under stress. Nat Commun 2013, 4, 1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubner, A.; Mulholland, D.J.; Standen, C.L.; Karasarides, M.; Cavanagh-Kyros, J.; Barrett, T.; Chi, H.; Greiner, D.L.; Tournier, C.; Sawyers, C.L.; Flavell, R.A.; Wu, H.; Davis, R.J. JNK and PTEN cooperatively control the development of invasive adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2012, 109, 12046–12051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atala, A. Re: JNK and PTEN cooperatively control the development of invasive adenocarcinoma of the prostate. J Urol 2013, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Park, C.S.; Suppipat, K.; Mistretta, T.A.; Puppi, M.; Horton, T.M.; Rabin, K.; Gray, N.S.; Meijerink, J.P.P.; Lacorazza, H.D. Inactivation of KLF4 promotes T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia and activates the MAP2K7 pathway. Leukemia 2017, 31, 1314–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, F.; Yang, L.; Lu, X.; Chen, J.; Wu, D.; Wei, Y.; Nong, Q.; Zhang, L.; Fang, W.; Chen, X.; Ling, X.; Yang, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, J. The MKK7 p.Glu116Lys Rare Variant Serves as a Predictor for Lung Cancer Risk and Prognosis in Chinese. PLoS Genet 2016, 12, e1005955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, H.; Sato, A.; Aihara, Y.; Ikarashi, Y.; Midorikawa, Y.; Kracht, M.; Nakagama, H.; Okamoto, K. MKK7 mediates miR-493-dependent suppression of liver metastasis of colon cancer cells. Cancer Sci 2014, 105, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornatore, L.; Sandomenico, A.; Raimondo, D.; Low, C.; Rocci, A.; Tralau-Stewart, C.; Capece, D.; D’Andrea, D.; Bua, M.; Boyle, E.; van Duin, M.; Zoppoli, P.; Jaxa-Chamiec, A.; Thotakura, A.K.; Dyson, J.; Walker, B.A.; Leonardi, A.; Chambery, A.; Driessen, C.; Sonneveld, P.; Morgan, G.; Palumbo, A.; Tramontano, A.; Rahemtulla, A.; Ruvo, M.; Franzoso, G. Cancer-selective targeting of the NF-kappaB survival pathway with GADD45beta/MKK7 inhibitors. Cancer Cell 2014, 26, 495–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rega, C.; Russo, R.; Foca, A.; Sandomenico, A.; Iaccarino, E.; Raimondo, D.; Milanetti, E.; Tornatore, L.; Franzoso, G.; Pedone, P.V.; Ruvo, M.; Chambery, A. Probing the interaction interface of the GADD45beta/MKK7 and MKK7/DTP3 complexes by chemical cross-linking mass spectrometry. Int J Biol Macromol 2018, 114, 114–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, I.S.; Jun, S.Y.; Na, H.J.; Kim, H.T.; Jung, S.Y.; Ha, G.H.; Park, Y.H.; Long, L.Z.; Yu, D.Y.; Kim, J.M.; Kim, J.H.; Ko, J.H.; Kim, C.H.; Kim, N.S. Inhibition of MKK7-JNK by the TOR signaling pathway regulator-like protein contributes to resistance of HCC cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis. Gastroenterology 2012, 143, 1341–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, T.; Wang, J.; Pei, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wu, Y.; Qiu, G.; Zhang, D.; Lv, M.; Li, W.; Zhang, J. Neddylation controls basal MKK7 kinase activity in breast cancer cells. Oncogene 2016, 35, 2624–2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, W.; Wang, J.; Feng, J.; Wang, Q.; Jin, J.; Lv, M.; Li, X.; Li, Y.; Ma, Y.; Shen, B.; Zhang, J. Receptor for activated C kinase 1 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma growth by enhancing mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 7 activity. Hepatology 2013, 57, 140–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takahashi, S.; Ebihara, A.; Kajiho, H.; Kontani, K.; Nishina, H.; Katada, T. RASSF7 negatively regulates pro-apoptotic JNK signaling by inhibiting the activity of phosphorylated-MKK7. Cell Death Differ 2011, 18, 645–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliz, A.D.; Yoo, H.J.; Vertii, A.; Dolan, A.C.; Tournier, C.; Davis, R.J.; Keaney, J.F., Jr.; Kant, S. Mitogen Kinase Kinase (MKK7) Controls Cytokine Production In Vitro and In Vivo in Mice. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22, 9364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kant, S.; Standen, C.L.; Morel, C.; Jung, D.Y.; Kim, J.K.; Swat, W.; Flavell, R.A.; Davis, R.J. A Protein Scaffold Coordinates SRC-Mediated JNK Activation in Response to Metabolic Stress. Cell Rep 2017, 20, 2775–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.I.; Boyle, D.L.; Berdeja, A.; Firestein, G.S. Regulation of inflammatory arthritis by the upstream kinase mitogen activated protein kinase kinase 7 in the c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway. Arthritis Res Ther 2012, 14, R38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tournier, C.; Whitmarsh, A.J.; Cavanagh, J.; Barrett, T.; Davis, R.J. The MKK7 gene encodes a group of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase kinases. Mol Cell Biol 1999, 19, 1569–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, D.T.; Bardwell, A.J.; Grewal, S.; Iverson, C.; Bardwell, L. Interacting JNK-docking sites in MKK7 promote binding and activation of JNK mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Biol Chem 2006, 281, 13169–13179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaoka, Y.; Nishina, H. Diverse physiological functions of MKK4 and MKK7 during early embryogenesis. J Biochem 2010, 148, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; MacLeod, R.; Dunlop, A.J.; Edwards, H.V.; Advant, N.; Gibson, L.C.; Devine, N.M.; Brown, K.M.; Adams, D.R.; Houslay, M.D.; Baillie, G.S. A scanning peptide array approach uncovers association sites within the JNK/beta arrestin signalling complex. FEBS Lett 2009, 583, 3310–3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, D.T.; Bardwell, A.J.; Abdollahi, M.; Bardwell, L. A docking site in MKK4 mediates high affinity binding to JNK MAPKs and competes with similar docking sites in JNK substrates. J Biol Chem 2003, 278, 32662–32672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

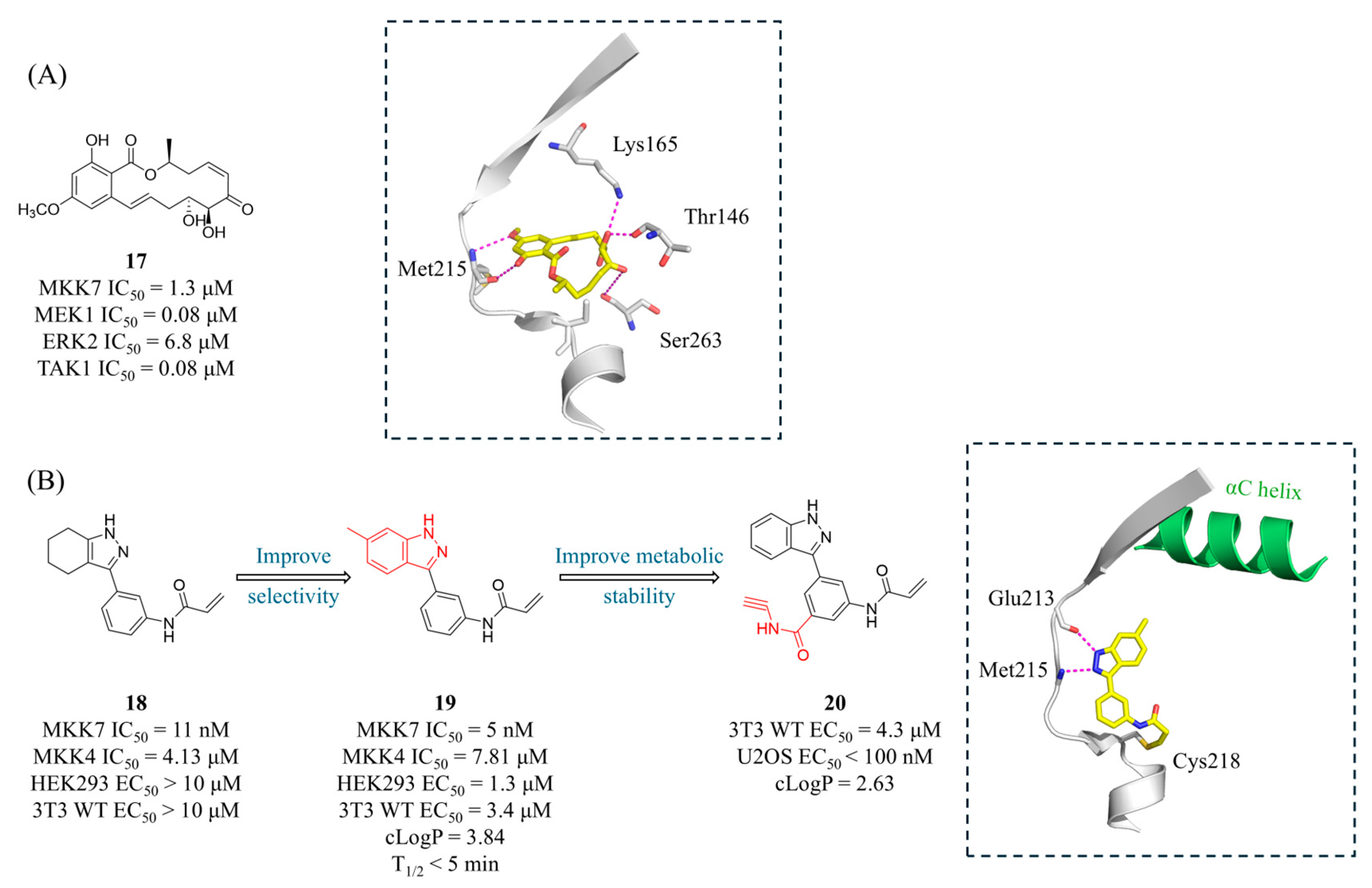

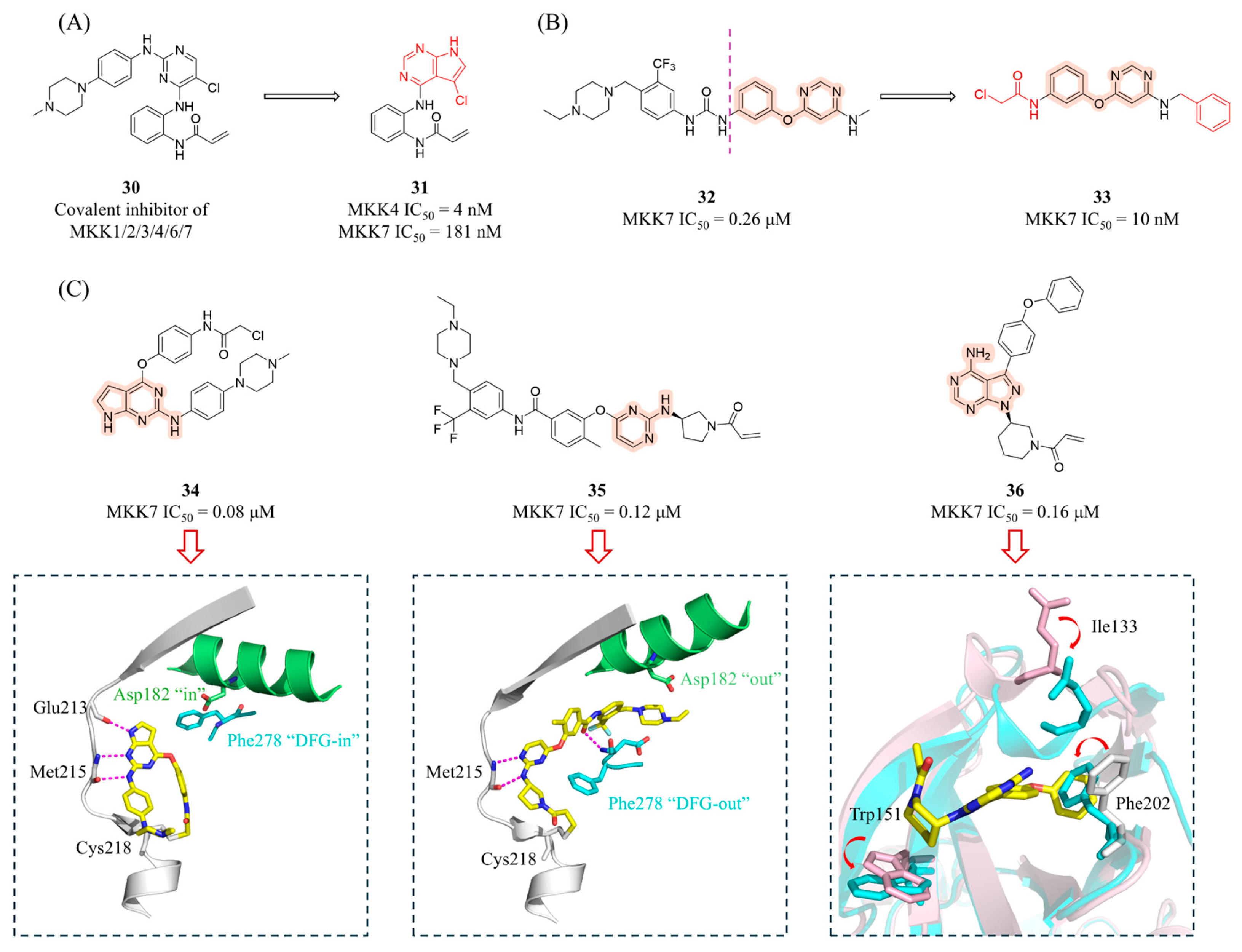

- Jiang, J.; Jiang, B.; He, Z.; Ficarro, S.B.; Che, J.; Marto, J.A.; Gao, Y.; Zhang, T.; Gray, N.S. Discovery of Covalent MKK4/7 Dual Inhibitor. Cell Chem Biol 2020, 27, 1553–1560 e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deibler, K.K.; Mishra, R.K.; Clutter, M.R.; Antanasijevic, A.; Bergan, R.; Caffrey, M.; Scheidt, K.A. A Chemical Probe Strategy for Interrogating Inhibitor Selectivity Across the MEK Kinase Family. ACS Chem Biol 2017, 12, 1245–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogabe, Y.; Matsumoto, T.; Hashimoto, T.; Kirii, Y.; Sawa, M.; Kinoshita, T. 5Z-7-Oxozeaenol covalently binds to MAP2K7 at Cys218 in an unprecedented manner. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 2015, 25, 593–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.X.; Pei, D.S.; Guan, Q.H.; Sun, Y.F.; Liu, X.M.; Zhang, G.Y. Blockade of the translocation and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4 (MKK4) signaling attenuates neuronal damage during later ischemia-reperfusion. J Neurochem 2006, 98, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Z.; Kukekov, N.V.; Greene, L.A. POSH acts as a scaffold for a multiprotein complex that mediates JNK activation in apoptosis. EMBO J 2003, 22, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevchenko, E.; Poso, A.; Pantsar, T. The autoinhibited state of MKK4: Phosphorylation, putative dimerization and R134W mutant studied by molecular dynamics simulations. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2020, 18, 2687–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolle, P.; Hardick, J.; Cronin, S.J.F.; Engel, J.; Baumann, M.; Lategahn, J.; Penninger, J.M.; Rauh, D. Targeting the MKK7-JNK (Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase 7-c-Jun N-Terminal Kinase) Pathway with Covalent Inhibitors. J Med Chem 2019, 62, 2843–2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sogabe, Y.; Hashimoto, T.; Matsumoto, T.; Kirii, Y.; Sawa, M.; Kinoshita, T. A crucial role of Cys218 in configuring an unprecedented auto-inhibition form of MAP2K7. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2016, 473, 476–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroder, M.; Tan, L.; Wang, J.; Liang, Y.; Gray, N.S.; Knapp, S.; Chaikuad, A. Catalytic Domain Plasticity of MKK7 Reveals Structural Mechanisms of Allosteric Activation and Diverse Targeting Opportunities. Cell Chem Biol 2020, 27, 1285–1295 e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrt, C.; Schulze, T.; Graef, J.; Diedrich, K.; Pletzer-Zelgert, J.; Rarey, M. ProteinsPlus: a publicly available resource for protein structure mining. Nucleic Acids Res 2025, 53, W478–W484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogura, M.; Kikuchi, H.; Shakespear, N.; Suzuki, T.; Yamaki, J.; Homma, M.K.; Oshima, Y.; Homma, Y. Prenylated quinolinecarboxylic acid derivative prevents neuronal cell death through inhibition of MKK4. Biochem Pharmacol 2019, 162, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deibler, K.K.; Schiltz, G.E.; Clutter, M.R.; Mishra, R.K.; Vagadia, P.P.; O’Connor, M.; George, M.D.; Gordon, R.; Fowler, G.; Bergan, R.; Scheidt, K.A. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of 3-Arylindazoles as Selective MEK4 Inhibitors. ChemMedChem 2019, 14, 615–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwong, A.J.; Pham, T.N.D.; Oelschlager, H.E.; Munshi, H.G.; Scheidt, K.A. Rational Design, Optimization, and Biological Evaluation of Novel MEK4 Inhibitors against Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. ACS Med Chem Lett 2021, 12, 1559–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klovekorn, P.; Pfaffenrot, B.; Juchum, M.; Selig, R.; Albrecht, W.; Zender, L.; Laufer, S.A. From off-to on-target: New BRAF-inhibitor-template-derived compounds selectively targeting mitogen activated protein kinase kinase 4 (MKK4). Eur J Med Chem 2021, 210, 112963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaffenrot, B.; Klovekorn, P.; Juchum, M.; Selig, R.; Albrecht, W.; Zender, L.; Laufer, S.A. Design and synthesis of 1H-pyrazolo[3,4-b]pyridines targeting mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4 (MKK4)—A promising target for liver regeneration. Eur J Med Chem 2021, 218, 113371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juchum, M.; Pfaffenrot, B.; Klovekorn, P.; Selig, R.; Albrecht, W.; Zender, L.; Laufer, S.A. Scaffold modified Vemurafenib analogues as highly selective mitogen activated protein kinase kinase 4 (MKK4) inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem 2022, 240, 114584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kircher, T.; Pantsar, T.; Oder, A.; Peter von Kries, J.; Juchum, M.; Pfaffenrot, B.; Kloevekorn, P.; Albrecht, W.; Selig, R.; Laufer, S. Design and synthesis of novel fluorescently labeled analogs of vemurafenib targeting MKK4. Eur J Med Chem 2021, 209, 112901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzengruber, L.; Sander, P.; Zwirner, S.; Rasch, A.; Eberlein, E.; Selig, R.; Albrecht, W.; Zender, L.; Laufer, S.A. Discovery of the First Highly Selective 1,4-dihydropyrido[3,4-b]pyrazin-3(2H)-one MKK4 Inhibitor. J Med Chem 2025, 68, 14782–14805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Sabnis, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, T.; Buhrlage, S.J.; Jones, L.H.; Gray, N.S. Developing irreversible inhibitors of the protein kinase cysteinome. Chem Biol 2013, 20, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.J.; Du, W.; Junco, J.J.; Bridges, C.S.; Shen, Y.; Puppi, M.; Rabin, K.R.; Lacorazza, H.D. Inhibition of the MAP2K7-JNK pathway with 5Z-7-oxozeaenol induces apoptosis in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Oncotarget 2021, 12, 1787–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Powell, F.; Larsen, N.A.; Lai, Z.; Byth, K.F.; Read, J.; Gu, R.F.; Roth, M.; Toader, D.; Saeh, J.C.; Chen, H. Mechanism and in vitro pharmacology of TAK1 inhibition by (5Z)-7-Oxozeaenol. ACS Chem Biol 2013, 8, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

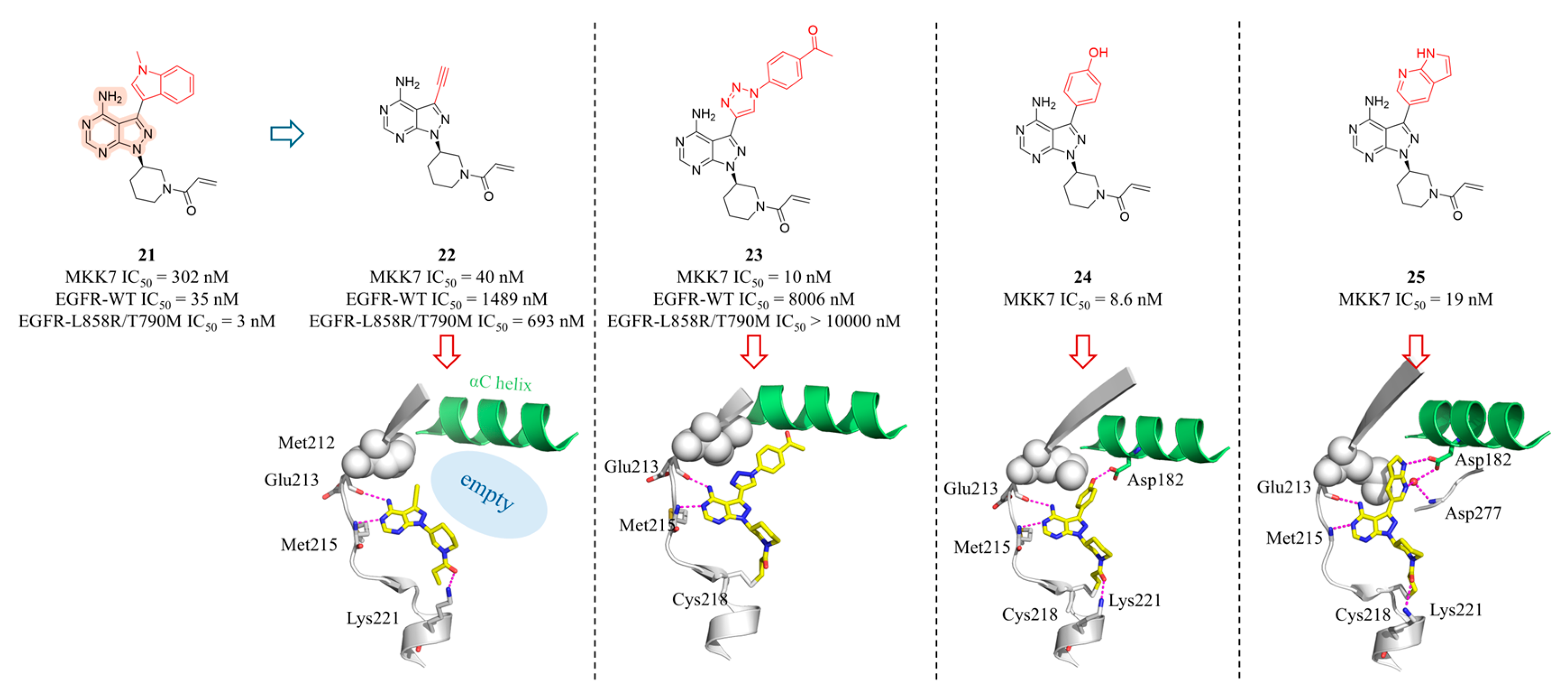

- Shraga, A.; Olshvang, E.; Davidzohn, N.; Khoshkenar, P.; Germain, N.; Shurrush, K.; Carvalho, S.; Avram, L.; Albeck, S.; Unger, T.; Lefker, B.; Subramanyam, C.; Hudkins, R.L.; Mitchell, A.; Shulman, Z.; Kinoshita, T.; London, N. Covalent Docking Identifies a Potent and Selective MKK7 Inhibitor. Cell Chem Biol 2019, 26, 98–108 e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolle, P.; Engel, J.; Smith, S.; Goebel, L.; Hennes, E.; Lategahn, J.; Rauh, D. Characterization of Covalent Pyrazolopyrimidine-MKK7 Complexes and a Report on a Unique DFG-in/Leu-in Conformation of Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase 7 (MKK7). J Med Chem 2019, 62, 5541–5546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

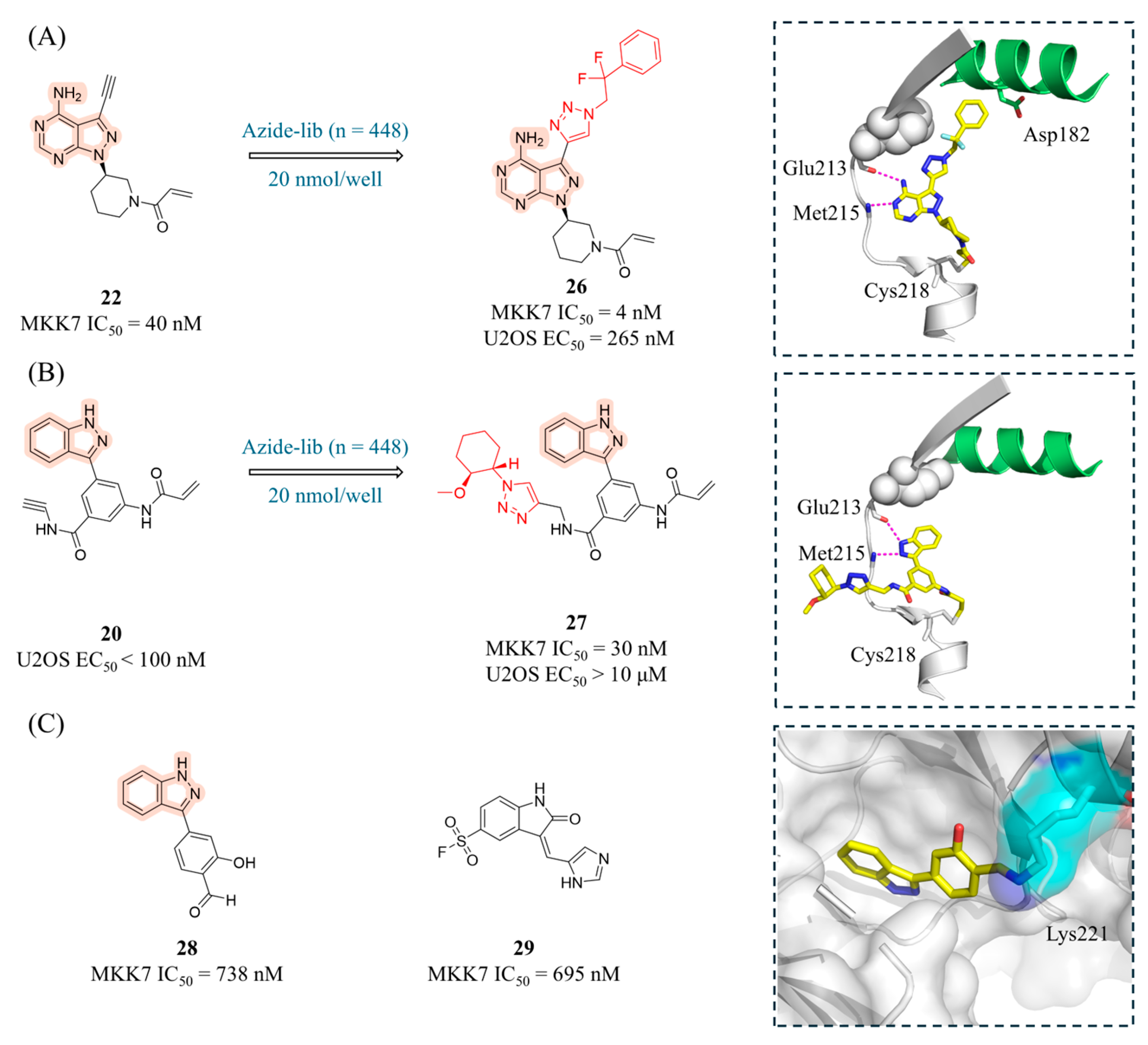

- Gehrtz, P.; Marom, S.; Buhrmann, M.; Hardick, J.; Kleinbolting, S.; Shraga, A.; Dubiella, C.; Gabizon, R.; Wiese, J.N.; Muller, M.P.; Cohen, G.; Babaev, I.; Shurrush, K.; Avram, L.; Resnick, E.; Barr, H.; Rauh, D.; London, N. Optimization of Covalent MKK7 Inhibitors via Crude Nanomole-Scale Libraries. J Med Chem 2022, 65, 10341–10356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tivon, B.; Wiese, J.; Muller, M.P.; Gabizon, R.; Rauh, D.; London, N. Computational Design of Lysine Targeting Covalent Binders Using Rosetta. J Chem Inf Model 2025, 65, 5612–5622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.; Gurbani, D.; Du, G.; Everley, R.A.; Browne, C.M.; Chaikuad, A.; Tan, L.; Schroder, M.; Gondi, S.; Ficarro, S.B.; Sim, T.; Kim, N.D.; Berberich, M.J.; Knapp, S.; Marto, J.A.; Westover, K.D.; Sorger, P.K.; Gray, N.S. Leveraging Compound Promiscuity to Identify Targetable Cysteines within the Kinome. Cell Chem Biol 2019, 26, 818–829 e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, K.; Ito, Y.; Takenouchi, S.; Nakagawa-Saito, Y.; Suzuki, S.; Togashi, K.; Sugai, A.; Mitobe, Y.; Sonoda, Y.; Kitanaka, C.; Okada, M. Effective Targeting of Glioma Stem Cells by BSJ-04-122, a Novel Covalent MKK4/7 Dual Inhibitor. Anticancer Res 2025, 45, 2917–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.R.; Orr, M.J.; Kwong, A.J.; Deibler, K.K.; Munshi, H.H.; Bridges, C.S.; Chen, T.J.; Zhang, X.; Lacorazza, H.D.; Scheidt, K.A. Rational Design of Highly Potent and Selective Covalent MAP2K7 Inhibitors. ACS Med Chem Lett 2023, 14, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Yang, W.S.; Yu, T.; Yi, Y.S.; Park, J.G.; Jeong, D.; Kim, J.H.; Oh, J.S.; Yoon, K.; Kim, J.H.; Cho, J.Y. Novel anti-inflammatory function of NSC95397 by the suppression of multiple kinases. Biochem Pharmacol 2014, 88, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

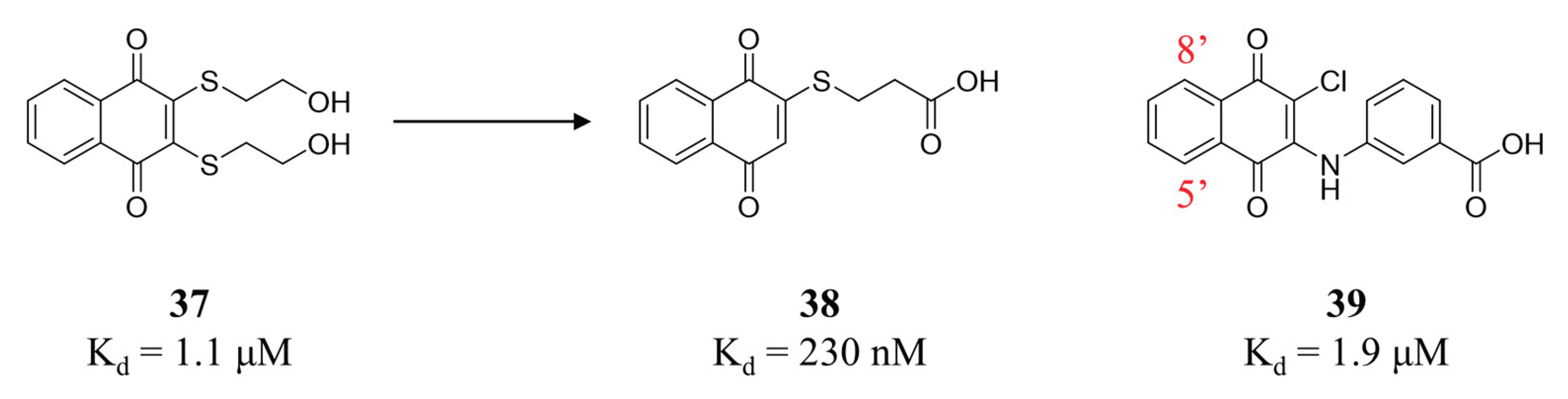

- Schepetkin, I.A.; Karpenko, A.S.; Khlebnikov, A.I.; Shibinska, M.O.; Levandovskiy, I.A.; Kirpotina, L.N.; Danilenko, N.V.; Quinn, M.T. Synthesis, anticancer activity, and molecular modeling of 1,4-naphthoquinones that inhibit MKK7 and Cdc25. Eur J Med Chem 2019, 183, 111719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandomenico, A.; Di Rienzo, L.; Calvanese, L.; Iaccarino, E.; D’Auria, G.; Falcigno, L.; Chambery, A.; Russo, R.; Franzoso, G.; Tornatore, L.; D’Abramo, M.; Ruvo, M.; Milanetti, E.; Raimondo, D. Insights into the Interaction Mechanism of DTP3 with MKK7 by Using STD-NMR and Computational Approaches. Biomedicines 2020, 9, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tornatore, L.; Capece, D.; D’Andrea, D.; Begalli, F.; Verzella, D.; Bennett, J.; Acton, G.; Campbell, E.A.; Kelly, J.; Tarbit, M.; Adams, N.; Bannoo, S.; Leonardi, A.; Sandomenico, A.; Raimondo, D.; Ruvo, M.; Chambery, A.; Oblak, M.; Al-Obaidi, M.J.; Kaczmarski, R.S.; Gabriel, I.; Oakervee, H.E.; Kaiser, M.F.; Wechalekar, A.; Benjamin, R.; Apperley, J.F.; Auner, H.W.; Franzoso, G. Preclinical toxicology and safety pharmacology of the first-in-class GADD45beta/MKK7 inhibitor and clinical candidate, DTP3. Toxicol Rep 2019, 6, 369–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Short Biography of Authors

| MAP3Ks | External/internal stimuli | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| TAK1 | TNF-α, IL-1, LPS, TGF-β, ROS, osmotic pressure | Sensing Lys63-linked polyubiquitinylation events at the TNF receptor. Activated through ubiquitination modifications by TRAF proteins. |

| ASK1-3 | H2O2, ROS, ER stress, TNF-α, Fasl, calcium ion | Inhibited by binding to antioxidant proteins (such as Thioredoxin) in the resting state; oxidative stress causes its dissociation and activation. |

| MLKs | TNF-α, IL-1, UV, heat shock, osmotic pressure, GPCR signals | Involved in cytoskeletal rearrangement, activated by small GTPases (such as Rac1, Cdc42). |

| MEKK1-4 | MEKK1: UV, serum deprivation, cytoskeletal perturbation MEKK2/3: TNF-α, IL-1, LPS MEKK4: osmotic pressure, cytotoxic agent |

Partially activated through recruitment by small GTPases (Rho, Rac) or receptor complexes. |

| DLK | neuronal damage (axotomy, ischemia), oxidative stress | Primarily expressed in the nervous system and involved in neurodegeneration and regeneration. |

| LZK | neuronal damage, oxidative stress | Functionally redundant with DLK, acting as a co-regulator of the JNK pathway in neurons. |

| HPK1 | lymphocyte antigen receptors, TNF-α, IL-1, LPS | Requiring own phosphorylation on tyrosine and subsequent interaction with adaptors of the SLP family. Ubiquitinated by E3 ubiquitin ligases, leading to its proteasomal degradation and limited signal duration. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).