Submitted:

24 January 2026

Posted:

27 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis

2.2. Structural Characterization

2.3. Electronic Structure Calculations

2.4. Magnetic Properties Measurements

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Synthesis

3.2. Crystal Structure and Bonding

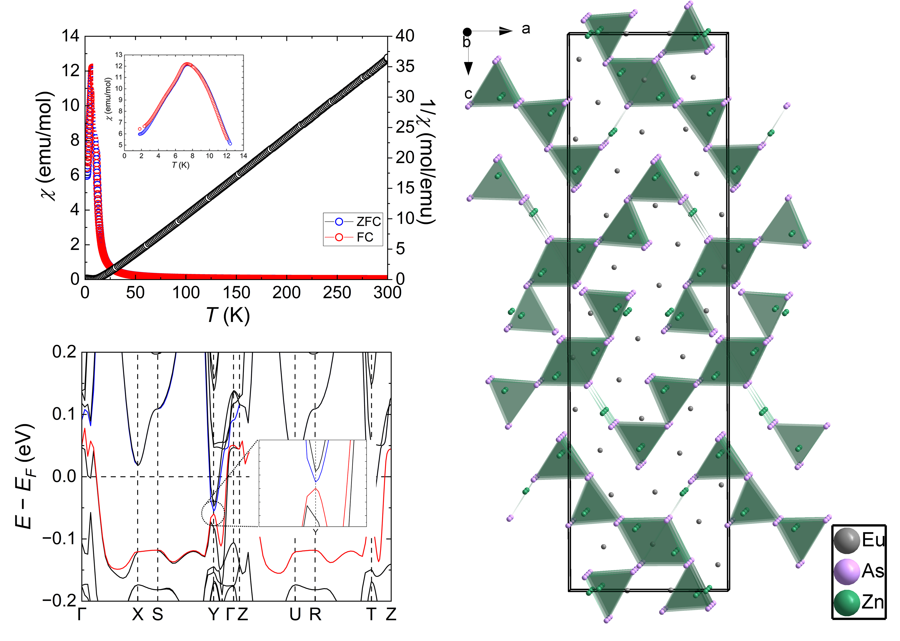

3.3. Electronic Structure

3.4. Magnetic Properties

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nesper, R. The Zintl-Klemm Concept – A Historical Survey. Z. Fur Anorg. Und Allg. Chem. 2014, 640, 2639–2648. [CrossRef]

- Kauzlarich, S.M. Zintl Phases: From Curiosities to Impactful Materials. Chem. Mater. 2023, 35, 7355–7362. [CrossRef]

- Ovchinnikov, A.; Bobev, S. Zintl phases with group 15 elements and the transition metals: A brief overview of pnictides with diverse and complex structures. J. Solid State Chem. 2019, 270, 346–359. [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.-F.; Xia, S.-Q. Recent progresses on thermoelectric Zintl phases: Structures, materials and optimization. J. Solid State Chem. 2019, 270, 252–264. [CrossRef]

- Kauzlarich, S.M.; Zevalkink, A.; Toberer, E.; Snyder, G.J. Zintl Phases: Recent Developments in Thermoelectrics and Future Outlook. In Thermoelectric Materials and Devices; The Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Kauzlarich, S.M.; Devlin, K.P.; Perez, C.J. Zintl phases for thermoelectric applications. In Thermoelectric Energy Conversion; Elsevier: 2021; pp. 157-182.

- Islam, M.; Kauzlarich, S.M. The Potential of Arsenic-based Zintl Phases as Thermoelectric Materials: Structure & Thermoelectric Properties. Z. Fur Anorg. Und Allg. Chem. 2023, 649. [CrossRef]

- Luo, D.B.; Wang, Y.X.; Yan, Y.L.; Yang, G.; Yang, J.M. The high thermopower of the Zintl compound Sr5Sn2As6 over a wide temperature range: first-principles calculations. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 15159–15167. [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.L.; Wang, Y.X.; Zhang, G.B. Electronic structure and thermoelectric performance of Zintl compound Ca5Ga2As6. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 20284–20290. [CrossRef]

- Devlin, K.P.; Kazem, N.; Zaikina, J.V.; Cooley, J.A.; Badger, J.R.; Fettinger, J.C.; Taufour, V.; Kauzlarich, S.M. Eu11Zn4Sn2As12: A Ferromagnetic Zintl Semiconductor with a Layered Structure Featuring Extended Zn4As6 Sheets and Ethane-like Sn2As6 Units. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 7067–7076. [CrossRef]

- Ogunbunmi, M.O.; Baranets, S.; Childs, A.B.; Bobev, S. The Zintl phases AIn2As2 (A = Ca, Sr, Ba): new topological insulators and thermoelectric material candidates. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 9173–9184. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Gao, W.; Chen, Z.; Chu, W.; Nie, Y.; Ma, S.; Han, Y.; Wu, M.; Li, T.; Niu, Q.; et al. Magnetic properties of the layered magnetic topological insulatorEuSn2As2. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 104, 054435. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Song, Z.; Wang, Z.; Weng, H.; Dai, X. Higher-Order Topology of the Axion Insulator EuIn2As2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 122, 256402. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Wang, Z.; Chen, X.; Lu, J.-Y.; Zhang, J.; Luo, X.; Cao, G.-H.; Dong, S.; Wang, Z.-C. Unusual magnetic and transport properties in the Zintl phase Eu11Zn6As12. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2024, 8. [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Yang, H.; Li, Y.; Pei, C.; Wang, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Li, C.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, S.; Wu, J.; et al. Pressure-induced superconductivity in the Zintl topological insulator SrIn2As2. Phys. Rev. B 2023, 108, 224510. [CrossRef]

- Rotter, M.; Pangerl, M.; Tegel, M.; Johrendt, D. Superconductivity and Crystal Structures of (Ba1−xKx)Fe2As2 (x=0–1). Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2008, 47, 7949–7952. [CrossRef]

- Balguri, S.; Mahendru, M.B.; Delgado, E.O.G.; Fruhling, K.; Yao, X.; Graf, D.E.; Rodriguez-Rivera, J.A.; Aczel, A.A.; Hicken, T.J.; Luetkens, H.; et al. Two types of colossal magnetoresistance with distinct mechanisms in Eu5In2As6. Phys. Rev. B 2025, 111. [CrossRef]

- Brechtel, E.; Cordier, G.; Schafer, H. Darstellung und Kristallstruktur von Ca9Mn4Bi9 und Ca9Zn4Bi9 /Preparation and Crystal Structure of Ca9Mn4Bi9 and Ca9Zn4Bi9. Z. Fur Naturforschung Sect. B-A J. Chem. Sci. 1979, 34, 1229–1233. [CrossRef]

- Brechtel, E.; Cordier, G.; Schäfer, H. Neue Verbindungen mit der Ca9Mi4Bi9-Struktur: Zur Kenntnis von Ca9Cd4Bi9, Sr9Cd4Bi9 und Ca9Zn4Sb9 / New Compounds with the Ca9Mn4Bi9 Structure: Ca9Cd4Bi9, Sr9Cd4Bi9, and Ca9Zn4Sb9. Z. Fur Naturforschung Sect. B-A J. Chem. Sci. 1981, 36, 1099–1104. [CrossRef]

- Bobev, S.; Thompson, J.D.; Sarrao, J.L.; Olmstead, M.M.; Hope, H.; Kauzlarich, S.M. Probing the Limits of the Zintl Concept: Structure and Bonding in Rare-Earth and Alkaline-Earth Zinc-Antimonides Yb9Zn4+xSb9 and Ca9Zn4.5Sb9. Inorg. Chem. 2004, 43, 5044–5052. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Xue, W.; Li, X.; Lan, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Zhang, F.; Yao, H.; Li, S.; Sui, J.; et al. Enhanced Thermoelectric Performance of Zintl Phase Ca9Zn4+xSb9 by Beneficial Disorder on the Selective Cationic Site. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 37741–37747. [CrossRef]

- Ohno, S.; Aydemir, U.; Amsler, M.; Pöhls, J.; Chanakian, S.; Zevalkink, A.; White, M.A.; Bux, S.K.; Wolverton, C.; Snyder, G.J. Achieving zT > 1 in Inexpensive Zintl Phase Ca9Zn4+xSb9 by Phase Boundary Mapping. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27. [CrossRef]

- Seo, N.; Lee, J.; Lee, Y.; Choi, M.-H.; Pi, J.H.; Lee, K.H.; Ok, K.M.; You, T.-S. Synergistic effect of cation substitution and p-type anion doping to improve thermoelectric properties in Zintl phases. Energy Mater. 2025, 5. [CrossRef]

- Smiadak, D.M.; Baranets, S.; Rylko, M.; Marshall, M.; Calderón-Cueva, M.; Bobev, S.; Zevalkink, A. Single crystal growth and characterization of new Zintl phase Ca9Zn3.1In0.9Sb9. J. Solid State Chem. 2021, 296. [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Kim, M.; Pi, J.H.; Choi, M.-H.; Ok, K.M.; Lee, K.H.; You, T.-S. Insights into the Crystal Structure and Thermoelectric Properties of the Zintl Phase Ca9Cd3+x–yMx+ySb9 (M = Cu, Zn) System. Chem. Mater. 2024, 37, 368–377. [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.-Q.; Bobev, S. Interplay between Size and Electronic Effects in Determining the Homogeneity Range of the A9Zn4+xPn9 and A9Cd4+xPn9 Phases (0 ≤ x ≤ 0.5), A = Ca, Sr, Yb, Eu; Pn = Sb, Bi. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 10011–10018. [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.-Q.; Bobev, S. New Manganese-Bearing Antimonides and Bismuthides with Complex Structures. Synthesis, Structural Characterization, and Electronic Properties of Yb9Mn4+xPn9 (Pn = Sb or Bi). Chem. Mater. 2009, 22, 840–850. [CrossRef]

- Kazem, N.; Hurtado, A.; Klobes, B.; Hermann, R.P.; Kauzlarich, S.M. Eu9Cd4–xCM2+x–y□ySb9: Ca9Mn4Bi9-Type Structure Stuffed with Coinage Metals (Cu, Ag, and Au) and the Challenges with Classical Valence Theory in Describing These Possible Zintl Phases. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 54, 850–859. [CrossRef]

- Bux, S.K.; Zevalkink, A.; Janka, O.; Uhl, D.; Kauzlarich, S.; Snyder, J.G.; Fleurial, J.-P. Glass-like lattice thermal conductivity and high thermoelectric efficiency in Yb9Mn4.2Sb9. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 2, 215–220. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-C.; Liu, K.-F.; Wang, Q.-Q.; Wang, Y.-M.; Pan, M.-Y.; Xia, S.-Q. Exploring New Zintl Phases in the 9-4-9 Family via Al Substitution. Synthesis, Structure, and Physical Properties of Ae9Mn4–xAlxSb9 (Ae = Ca, Yb, Eu). Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 3709–3717. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-J.; Salvador, J.; Bilc, D.; Mahanti, S.D.; Kanatzidis, M.G. Yb9Zn4Bi9: Extension of the Zintl Concept to the Mixed-Valent Spectator Cations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001, 123, 12704–12705. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.-C.; Wu, Z.; Xia, S.-Q.; Tao, X.-T.; Bobev, S. Structural Variability versus Structural Flexibility. A Case Study of Eu9Cd4+xSb9 and Ca9Mn4+xSb9 (x ≈ 1/2). Inorg. Chem. 2014, 54, 947–955. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, Q.; Liu, K.-F.; Tan, W.-J.; Liu, X.-C.; Xia, S.-Q. Sr9Mg4.45(1)Bi9 and Sr9Mg4.42(1)Sb9: Mg-Containing Zintl Phases with Low Thermal Conductivity. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 4026–4033. [CrossRef]

- Baranets, S.; Balvanz, A.; Darone, G.M.; Bobev, S. On the Effects of Aliovalent Substitutions in Thermoelectric Zintl Pnictides. Varied Polyanionic Dimensionality and Complex Structural Transformations─The Case of Sr3ZnP3 vs Sr3AlxZn1–xP3. Chem. Mater. 2022, 34, 4172–4185. [CrossRef]

- Ishtiyak, M.; Watts, S.R.; Thipe, B.; Womack, F.; Adams, P.; Bai, X.; Young, D.P.; Bobev, S.; Baranets, S. Advancing Heteroanionicity in Zintl Phases: Crystal Structures, Thermoelectric and Magnetic Properties of Two Quaternary Semiconducting Arsenide Oxides, Eu8Zn2As6O and Eu14Zn5As12O. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 63, 20226–20239. [CrossRef]

- SAINT, BrukerAXS Inc.: 2014.

- SADABS, BrukerAXS Inc.: 2014.

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT—Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A Found. Adv. 2015, 71, 3–8. [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C 2015, 71, 3-8.

- Dolomanov, O.V.; Bourhis, L.J.; Gildea, R.J.; Howard, J.A.K.; Puschmann, H. OLEX2: A complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Cryst. 2009, 42, 339–341. [CrossRef]

- Gelato, L.M.; Parthé, E. STRUCTURE TIDY– a computer program to standardize crystal structure data. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1987, 20, 139–143. [CrossRef]

- Kresse, G.; Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 1996, 54, 11169.

- Perdew, J.P.; Ruzsinszky, A.; Csonka, G.I.; Vydrov, O.A.; Scuseria, G.E.; Constantin, L.A.; Zhou, X.; Burke, K. Generalized gradient approximation for solids and their surfaces. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2007.

- Blöchl, P.E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 50, 17953–17979. [CrossRef]

- Wang, V.; Xu, N.; Liu, J.-C.; Tang, G.; Geng, W.-T. VASPKIT: A user-friendly interface facilitating high-throughput computing and analysis using VASP code. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2021, 267. [CrossRef]

- Campbell, B.J.; Stokes, H.T.; Tanner, D.E.; Hatch, D.M. ISODISPLACE: a web-based tool for exploring structural distortions. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2006, 39, 607–614. [CrossRef]

- H. T. Stokes, D.M.H., and B. J. Campbell ISOTROPY Software Suite, iso.byu.edu.

- Baranets, S.; He, H.; Bobev, S. Niobium-bearing arsenides and germanides from elemental mixtures not involving niobium: a new twist to an old problem in solid-state synthesis. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C Struct. Chem. 2018, 74, 623–627. [CrossRef]

- Klüfers, P.; Mewis, A.; Schuster, H.-U. AB2X2-Verbindungen im CaAl2Si2-Typ, VI. Z. Fur Krist. Mater. 1979, 149, 211–226. [CrossRef]

- Stoyko, S.S.; Khatun, M.; Mar, A. Ternary Arsenides A2Zn2As3 (A = Sr, Eu) and Their Stuffed Derivatives A2Ag2ZnAs3. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 2621–2628. [CrossRef]

- Saparov, B.; Bobev, S. Undecaeuropium hexazinc dodecaarsenide. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. E Crystallogr. Commun. 2010, 66, i24–i24. [CrossRef]

- Suen, N.-T.; Wang, Y.; Bobev, S. Synthesis, crystal structures, and physical properties of the new Zintl phases A21Zn4Pn18 (A=Ca, Eu; Pn=As, Sb)—Versatile arrangements of [ZnPn4] tetrahedra. J. Solid State Chem. 2015, 227, 204–211. [CrossRef]

- Ishtiyak, M.; Watts, S.R.; Pokhvata, O.; Kandabadage, T.; Baranets, S. Complex Structural Disorder in Thermoelectric Zintl Phases Eu21M4As18 (M = Mn, Zn). Z. Fur Anorg. Und Allg. Chem. 2025, 651. [CrossRef]

- Baranets, S.; Darone, G.M.; Bobev, S. Synthesis and structure of Sr14Zn1+As11 and Eu14Zn1+As11 (x ≤ 0.5). New members of the family of pnictides isotypic with Ca14AlSb11, exhibiting a new type of structural disorder. J. Solid State Chem. 2019, 280, 62–70. [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Karbasizadeh, S.; Narasimha, G.; Regmi, P.; Tao, C.; Mu, S.; Vasudevan, R.; Harrison, I.; Jin, R.; Gai, Z. Large bandgap observed on the surfaces of EuZn2As2 single crystals. Commun. Phys. 2025, 8, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-C.; Been, E.; Gaudet, J.; Alqasseri, G.M.A.; Fruhling, K.; Yao, X.; Stuhr, U.; Zhu, Q.; Ren, Z.; Cui, Y.; et al. Anisotropy of the magnetic and transport properties of EuZn2As2. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 105, 165122. [CrossRef]

- Blawat, J.; Marshall, M.; Singleton, J.; Feng, E.; Cao, H.; Xie, W.; Jin, R. Unusual Electrical and Magnetic Properties in Layered EuZn 2 As 2. Adv. Quantum Technol. 2022, 5. [CrossRef]

- Bukowski, Z.; Rybicki, D.; Babij, M.; Przewoźnik, J.; Gondek, Ł.; Żukrowski, J.; Kapusta, C. Canted antiferromagnetic order in EuZn2As2 single crystals. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Regmi, P.; Blawat, J.; Jin, R. Large unconventional Hall effect observed in EuZn2As2. Phys. Rev. B 2025, 111. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Wróblewska, M.; Shen, Z.; Toberer, E.S.; Taufour, V.; Kauzlarich, S.M. Magnetism and Thermoelectric Properties of the Zintl Semiconductor: Eu21Zn4As18. Chem. Mater. 2024, 36, 11499–11508. [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.; Zheng, J.; Pike, A.; Star, K.E.; Bux, S.K.; Hautier, G.; Kauzlarich, S.M. Diffuson-Driven Lattice Thermal Conductivity in Zintl Arsenides: Disrupting Mass-Thermal Conductivity Relation for High Thermoelectric Performance. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Cordero, B.; Gómez, V.; Platero-Prats, A.E.; Revés, M.; Echeverría, J.; Cremades, E.; Barragán, F.; Alvarez, S. Covalent radii revisited. Dalton Trans. 2008, 2832–2838. [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Chen, C.; Nan, P.; Long, Y.; Ge, B.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Y. Decoupling electrical conductivity and Seebeck coefficient via isoelectronic alloying in the 9-4-9-type Ca9−yEuyZn4.7Sb9 (0≤ y≤ 5.0) Zintl phase. J. Mater. Chem. 2026.

- Kazem, N.; Zaikina, J.V.; Ohno, S.; Snyder, G.J.; Kauzlarich, S.M. Coinage-Metal-Stuffed Eu9Cd4Sb9: Metallic Compounds with Anomalous Low Thermal Conductivities. Chem. Mater. 2015, 27, 7508–7519. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yox, P.; Voyles, J.; Kovnir, K. Synthesis, Crystal Structure, and Properties of Three La–Zn–P Compounds with Different Dimensionalities of the Zn–P Framework. Cryst. Growth Des. 2018, 18, 4076–4083. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.K.; Saparov, B.; Bobev, S. Synthesis, Crystal Structures and Properties of the Zintl Phases Sr2ZnP2, Sr2ZnAs2, A2ZnSb2 and A2ZnBi2 (A = Sr and Eu). Z. Fur Anorg. Und Allg. Chem. 2011, 637, 2018–2025. [CrossRef]

- Gvozdetskyi, V.; Lee, S.J.; Owens-Baird, B.; Dolyniuk, J.-A.; Cox, T.; Wang, R.; Lin, Z.; Ho, K.-M.; Zaikina, J.V. Ternary Zinc Antimonides Unlocked Using Hydride Synthesis. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 10686–10697. [CrossRef]

- Devlin, K.P.; Zhang, J.; Fettinger, J.C.; Choi, E.S.; Hauble, A.K.; Taufour, V.; Hermann, R.P.; Kauzlarich, S.M. Deconvoluting the Magnetic Structure of the Commensurately Modulated Quinary Zintl Phase Eu11–xSrxZn4Sn2As12. Inorg. Chem. 2021, 60, 5711–5723. [CrossRef]

- Ram, D.; Singh, J.; Banerjee, S.; Sundaresan, A.; Samal, D.; Kanchana, V.; Hossain, Z. Magnetotransport and electronic structure of EuAuSb: A candidate antiferromagnetic Dirac semimetal. Phys. Rev. B 2024, 109, 155152. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.-X.; Song, Z.; Fang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Weng, H. Manipulation of topological phase transitions and the mechanism of magnetic interactions in Eu-based Zintl-phase materials. Phys. Rev. B 2025, 111. [CrossRef]

- Mugiraneza, S.; Hallas, A.M. Tutorial: a beginner’s guide to interpreting magnetic susceptibility data with the Curie-Weiss law. Commun. Phys. 2022, 5, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Kittel, C.; McEuen, P. Introduction to solid state physics; John Wiley & Sons: 2018.

- Wu, D.; Na, S.; Li, Y.; Zhou, X.B.; Wu, W.; Song, Y.; Zheng, P.; Li, Z.; Luo, J. Single-crystal growth, structure and thermal transport properties of the metallic antiferromagnet Zintl-phase β-EuIn2As2. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 26, 8695–8703. [CrossRef]

- Radzieowski, M.; Stegemann, F.; Klenner, S.; Zhang, Y.; Fokwa, B.P.T.; Janka, O. On the divalent character of the Eu atoms in the ternary Zintl phases Eu5In2Pn6and Eu3MAs3(Pn = As–Bi; M = Al, Ga). Mater. Chem. Front. 2020, 4, 1231–1248. [CrossRef]

- Weippert, V.; Haffner, A.; Stamatopoulos, A.; Johrendt, D. Supertetrahedral Layers Based on GaAs or InAs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 11245–11252. [CrossRef]

- Goforth, A.M.; Klavins, P.; Fettinger, J.C.; Kauzlarich, S.M. Magnetic Properties and Negative Colossal Magnetoresistance of the Rare Earth Zintl phase EuIn2As2. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 47, 11048–11056. [CrossRef]

- Gebre, M.S.; Jiang, Z.; Riedel, Z.W.; Pappas, E.A.; Zhou, H.; Schleife, A.; Shoemaker, D.P. Unique Structure Type and Antiferromagnetic Ordering in Semiconducting Eu2InSnP3. Chem. Mater. 2025, 37, 6118–6126. [CrossRef]

- Day, R.P.; Yamakawa, K.; Cairns, L.P.; Singleton, J.; Cao, W.L.; Wu, C.; Allen, M.; Moore, J.E.; Analytis, J.G. Colossal magnetoresistance and anisotropic spin dynamics in the antiferromagnetic semiconductor Eu5Sn2As6. Phys. Rev. B 2025, 111. [CrossRef]

- Fender, S.S.; Thomas, S.M.; Ronning, F.; Bauer, E.D.; Thompson, J.D.; Rosa, P.F.S. Narrow-gap semiconducting behavior in antiferromagnetic Eu11InSb9. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2021, 5, 074603. [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Li, T.; Chen, X.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y.; Shang, Z.; Zheng, X.; Tian, H.; Wang, Z.; Bi, Y.; et al. Surface Half-Metallicity and Electronic Structure Evolution in A-Type Antiferromagnet EuIn2P2. Nano Lett. 2025, 25, 10419–10426. [CrossRef]

- Souza, J.C.; Thomas, S.M.; Bauer, E.D.; Thompson, J.D.; Ronning, F.; Pagliuso, P.G.; Rosa, P.F.S. Microscopic probe of magnetic polarons in antiferromagnetic Eu5In2Sb6. Phys. Rev. B 2022, 105, 035135. [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Lu, J.; Whalen, J.B.; Latturner, S.E. Flux Growth and Magnetoresistance Behavior of Rare Earth Zintl Phase EuMgSn. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 3342–3348. [CrossRef]

- Cook, M.S.; Peterson, E.A.; Kengle, C.S.; Kennedy, E.R.; Sheeran, J.; Girod, C.; Freitas, G.S.; Greer, S.M.; Abbamonte, P.; Pagliuso, P.G.; et al. Magnetic polaron formation in EuZn2P2. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2025, 9. [CrossRef]

| Compound | Space Group | References |

| Ca9Mn4+xBi9 | Pbam | [18] |

| Ca9Zn4+xSb9; (Ca,Yb)9(Zn,Cu)4+xSb9 | Pbam | [19,20,21,22,23] |

| Ca9(Zn,In)4+xSb9 |

Amm2a a a |

[24] |

| Ca9(Cd,M)4+xSb9 (M = Zn, Al) | a | [25] |

| Ca9Zn4+xBi9 | Pbam | [18,26] |

| Ca9Cd4+xBi9 | Pbam | [19,26] |

| Ca9(Mn,Al)4+xSb9 | Pbam | [27] |

| Sr9Cd4+xSb9 | Pbam | [26] |

| Sr9Cd4+xBi9 | Pbam | [19,26] |

| Eu9Cd4+xBi9, Eu9(Cd,M)4+xBi9 (M = Cu, Ag, Au) | Pbam | [26,28] |

| Yb9Mn4+xSb9, Yb9(Mn,M)4+xSb9 (M = Zn, Al) | Pbam | [27,29,30] |

| Yb9Mn4+xBi9 | Pbam | [27] |

| Yb9Zn4+xSb9 | Pbam | [20] |

| Yb9Zn4+xBi9 | Pbam | [26,31] |

| Yb9Cd4+xBi9 | Pbam | [26] |

| Eu9(Mn,Al)4+xSb9 | Cmcab | [30] |

| Ca9Mn4+xSb9, | Pnmac | [32] |

| Ca9Zn4+xAs9 | Pnmac | [32] |

| Sr9Mg4+xSb9 | Pnmac | [33] |

| Sr9Mg4+xBi9 | Pnmac | [33] |

| Eu9Zn4+xAs9 | Pnmac | This work |

| Chemical formula | Eu9Zn4.5As9 |

| fw/g mol−1 | 2336.08 |

| Space group | Pnma |

| a/(Å) | 12.1953(7) |

| b/(Å) | 4.3730(2) |

| c/(Å) | 42.674(2) |

| V (Å3) | 2275.8(2) |

| Z | 4 |

| ρcal./g cm−3 | 6.818 |

| μ(Ag Kα)/ cm−1 | 221.19 |

| Collected/independent reflections | 33102/4501 |

| R1 (I>2σ(I))a | 0.0191 |

| wR2 (I>2σ(I))a | 0.0348 |

| R1 (all data)a | 0.0217 |

| wR2 (all data)a | 0.0356 |

| Δρmax,min/e−·Å‒3 | 1.95/−1.24 |

| CCDC code | 2523214 |

| Atoms | Site | x | y | z | Ueqa (Å2) |

| Eu1b | 8d | 0.02077(3) | 0.17365(8) | 0.58230(2) | 0.00749(7) |

| Eu2b | 8d | 0.36020(3) | 0.20624(17) | 0.00124(2) | 0.012(17) |

| Eu3 | 4c | 0.03523(2) | 1/4 | 0.67579(2) | 0.00733(5) |

| Eu4 | 4c | 0.04118(2) | 1/4 | 0.19032(2) | 0.00876(5) |

| Eu5 | 4c | 0.06394(2) | 1/4 | 0.04691(2) | 0.01449(6) |

| Eu6 | 4c | 0.23374(2) | 1/4 | 0.32735(2) | 0.00802(5) |

| Eu7 | 4c | 0.28181(2) | 1/4 | 0.42064(2) | 0.01059(5) |

| Eu8 | 4c | 0.30237(2) | 1/4 | 0.24745(2) | 0.00891(5) |

| Eu9 | 4c | 0.31121(2) | 1/4 | 0.62266(2) | 0.00575(5) |

| Zn1b | 4c | 0.0749(1) | 1/4 | 0.38646(3) | 0.0076(2) |

| Zn2 | 4c | 0.09963(5) | 1/4 | 0.86014(2) | 0.0069(1) |

| Zn3b | 4c | 0.2755(1) | 1/4 | 0.17782(3) | 0.0069(2) |

| Zn4Bc | 4c | 0.3015(1) | 1/4 | 0.49314(3) | 0.0132(2) |

| Zn4Ac | 4c | 0.3646(1) | 1/4 | 0.50040(3) | 0.0132(2) |

| Zn5b | 4c | 0.3303(1) | 1/4 | 0.07027(3) | 0.0073(2) |

| Zn6 | 4c | 0.44570(5) | 1/4 | 0.74422(2) | 0.0070(1) |

| As1Ac | 4c | 0.04713(9) | 1/4 | 0.45177(2) | 0.0083(1) |

| As1Bc | 4c | 0.08877(9) | 1/4 | 0.46353(3) | 0.0083(1) |

| As2 | 4c | 0.05186(4) | 1/4 | 0.27507(2) | 0.00597(9) |

| As3 | 4c | 0.12226(4) | 1/4 | 0.79615(2) | 0.00485(8) |

| As4 | 4c | 0.25374(4) | 1/4 | 0.55010(2) | 0.00599(9) |

| As5 | 4c | 0.28296(4) | 1/4 | 0.70105(2) | 0.00565(9) |

| As6 | 4c | 0.31521(4) | 1/4 | 0.87441(2) | 0.00710(9) |

| As7 | 4c | 0.37576(4) | 1/4 | 0.12899(2) | 0.00743(9) |

| As8 | 4c | 0.49340(4) | 1/4 | 0.37946(2) | 0.00564(9) |

| As9 | 4c | 0.61590(5) | 1/4 | 0.52913(2) | 0.0097(1) |

| Atom pair | Distance (Å) | Atom pair | Distance (Å) |

| Zn1‒As1A | 2.808(2) | Zn4B‒As1B | 2.886(2) |

| Zn1‒As6 × 2 | 2.6154(7) | Zn4B‒As4 | 2.500(1) |

| Zn1‒As7 | 2.517(1) | Zn4B‒As9 × 2 | 2.5879(8) |

| Zn2‒As3 | 2.7444(7) | Zn5‒As1A | 2.807(2) |

| Zn2‒As6 | 2.6988(8) | Zn5‒As4 × 2 | 2.5634(7) |

| Zn2‒As8 × 2 | 2.5977(4) | Zn5‒As7 | 2.566(1) |

| Zn3‒As5 × 2 | 2.5043(6) | Zn6‒As2 × 2 | 2.5525(4) |

| Zn3‒As7 | 2.416(1) | Zn6‒As3 | 2.7574(8) |

| Zn4A‒As4 | 2.515(1) | Zn6‒As5 | 2.7079(8) |

| Zn4A‒As9 × 2 | 2.5348(7) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.