Submitted:

23 January 2026

Posted:

26 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Fundamentals of Photonic Gas Sensing

2.1. Key Sensing Parameters

2.2. Resonance Shift

2.3. Evanescent-Field-Enhanced Absorption

2.4. Interferometric and Phase-Based Sensing

3. Material Platforms for Integrated Photonic Gas Sensing

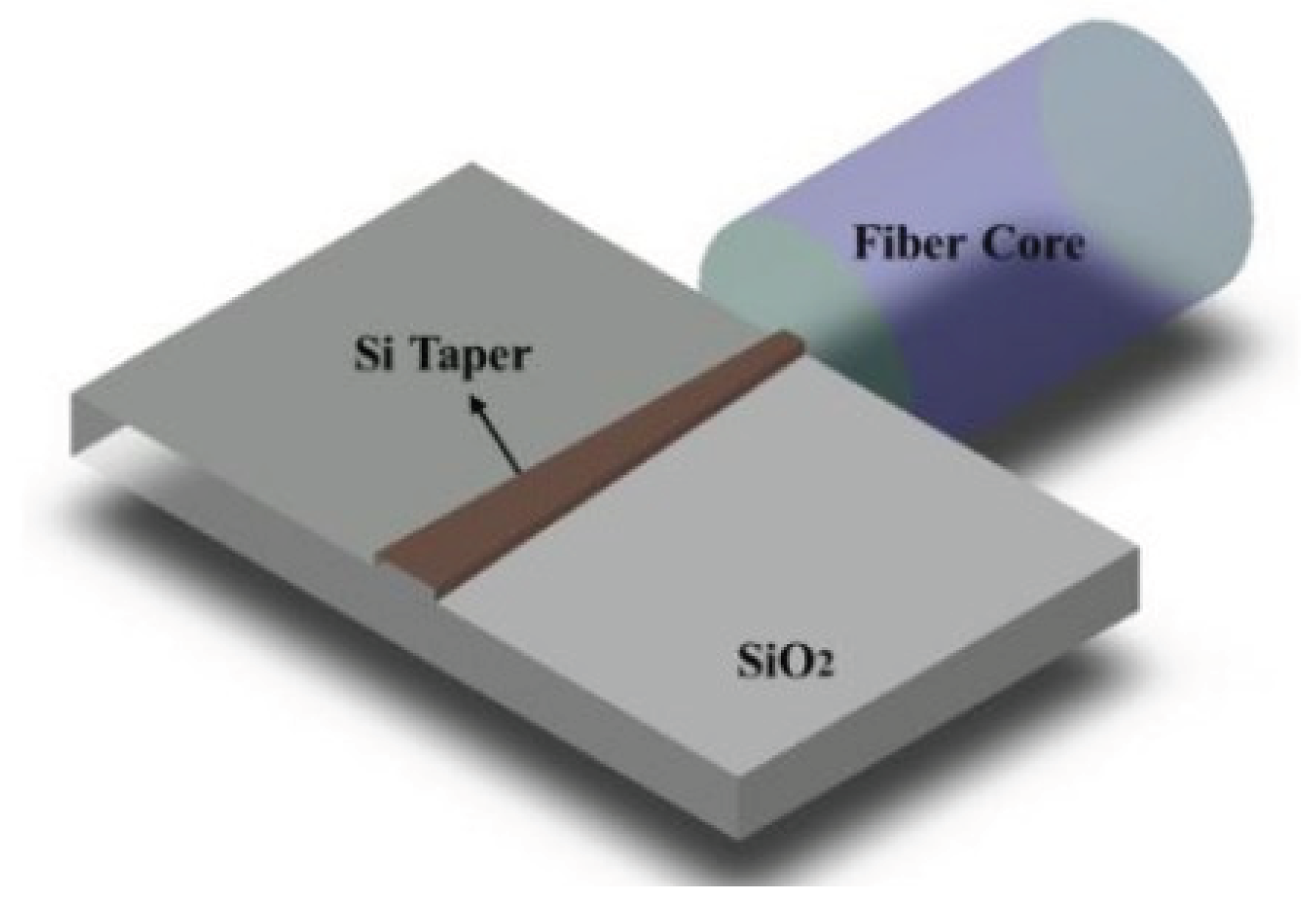

3.1. Silicon-on-Insulator (SOI)

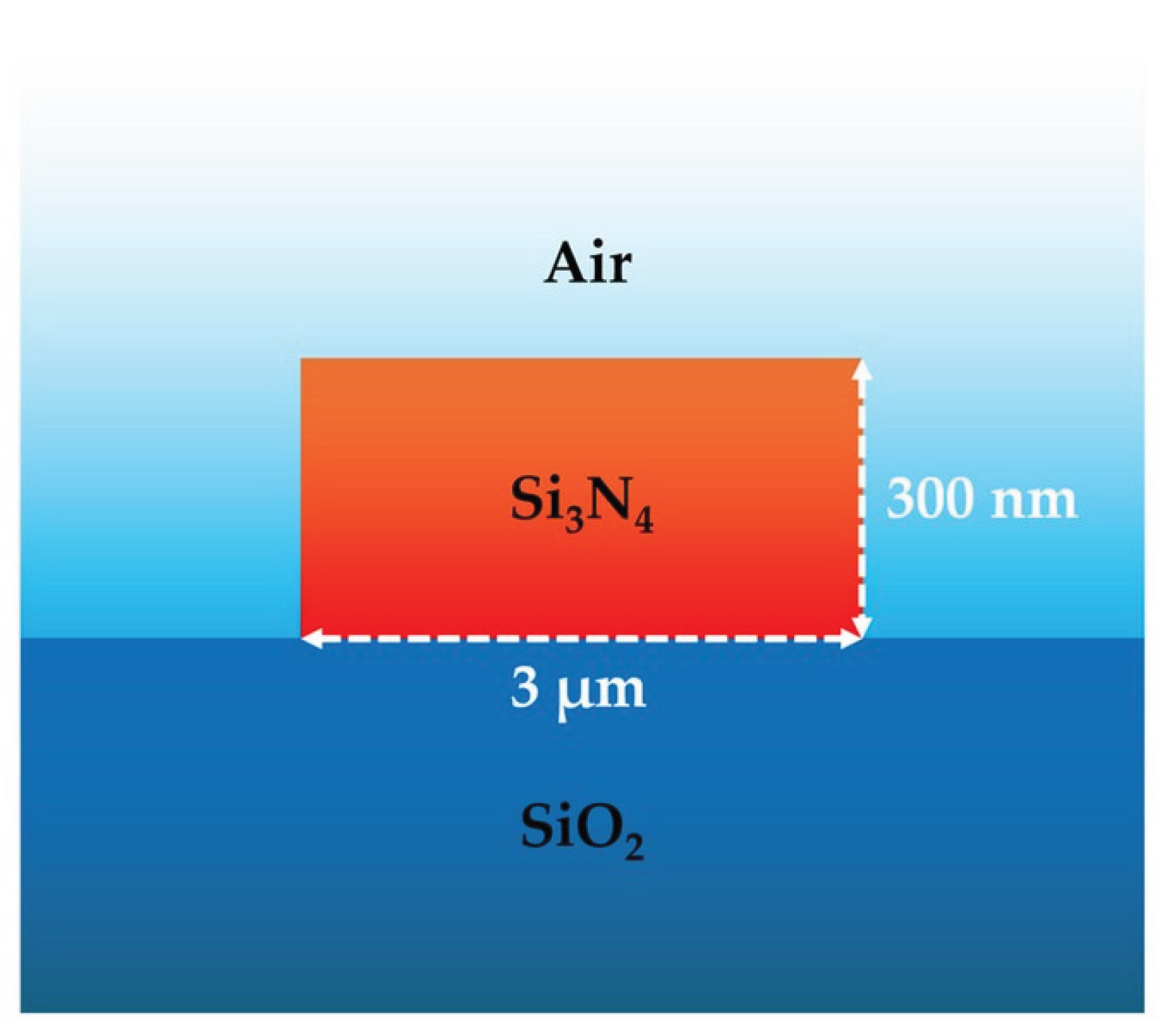

3.2. Silicon Nitride (Si3N4)

3.3. InP and III–V Semiconductors

3.4. Graphene and 2D Materials

3.5. Plasmonic Metals: Surface Plasmon Resonance Platforms

3.6. Lithium Niobate (LiNbO3)

3.7. Polymers

3.8. Chalcogenide Glasses (As2S3)

4. Photonic Gas Sensor Structures

4.1. Waveguide-Based Photonic Gas Sensors

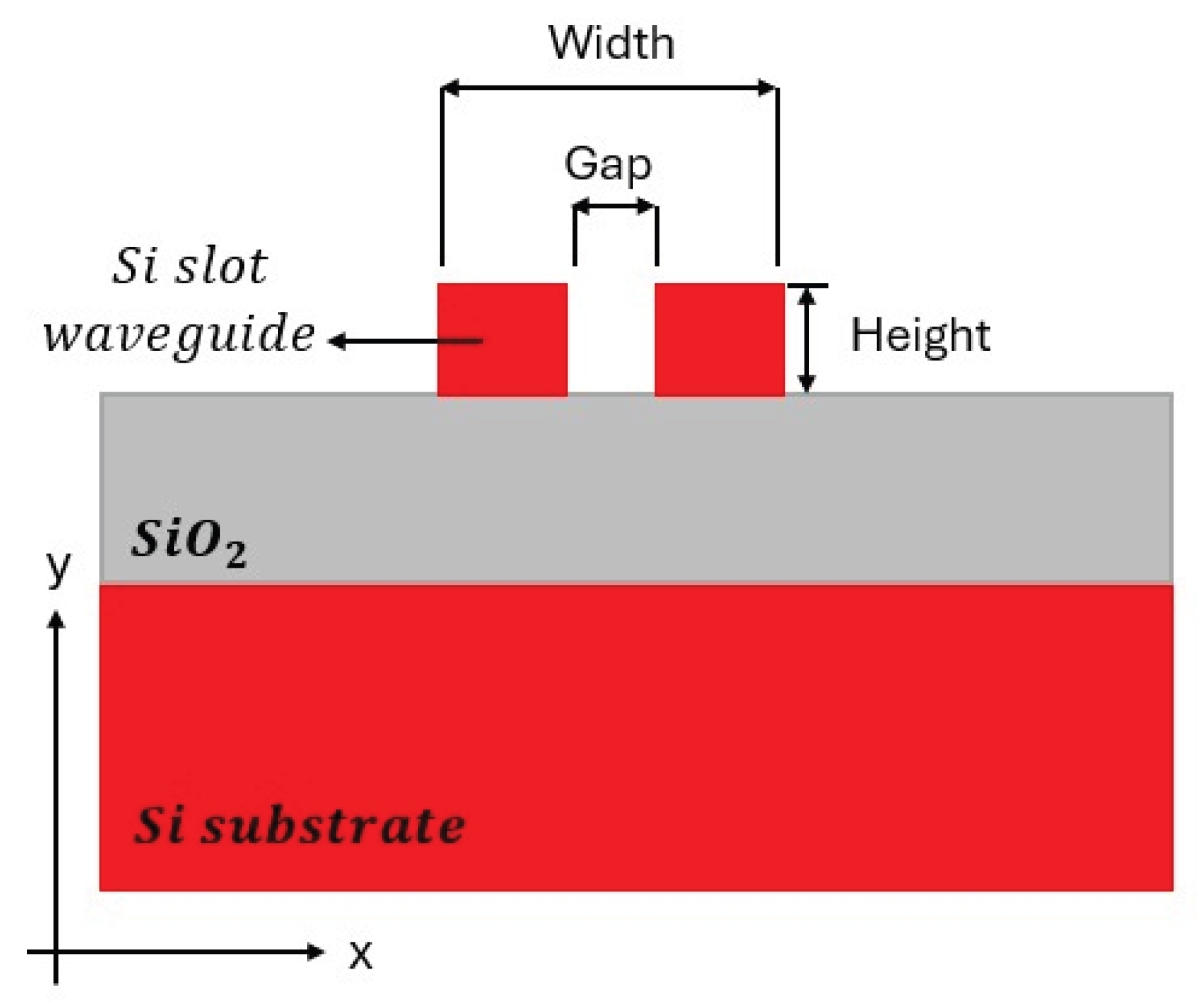

4.1.1. Silicon-Based Platforms (SOI)

4.1.2. Silicon Nitride (Si3N4)

4.1.3. Chalcogenide Glass

4.1.4. Lithium Niobate (LiNbO3)

4.1.5. Polymer and Organic Material

4.1.6. Graphene and 2D Material Integration

4.2. Resonator/Filter-Based Photonic Gas Sensors

4.2.1. Silicon on Insulator

4.2.2. Silicon Nitride (Si3N4)

4.2.3. Polymer and Organic Materials

4.2.4. Plasmonic Metasurfaces

4.3. Interferometer-Based Photonic Gas Sensors

4.3.1. Silicon on Insulator

4.3.2. Graphene and 2D Materials

5. Challenges and Future Perspectives

5.1. Challenges and Limitations

5.2. Future Perspectives

6. Conclusions

References

- Air pollution. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/air-pollution.

- Saxena, P.; Shukla, P. A review on recent developments and advances in environmental gas sensors to monitor toxic gas pollutants. Environmental Progress & Sustainable Energy 2023, vol. 42, e14126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinh, T.-V.; et al. A Potential Approach to Compensate the Gas Interference for the Analysis of NO by a Non-dispersive Infrared Technique. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 12152–12159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gad, S.C.; Handbook, P.D. 2008. [PubMed]

- Xia, L.; Liu, Y.; Chen, R.T.; Weng, B.; Zou, Y. Advancements in miniaturized infrared spectroscopic-based volatile organic compound sensors: A systematic review. Applied Physics Reviews 2024, 11, 031306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanan, S.; et al. Recent Advances on Metal Oxide Based Sensors for Environmental Gas Pollutants Detection. Critical Reviews in Analytical Chemistry 2025, 55, 911–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, C.J.; et al. Mid-infrared silicon photonics: From benchtop to real-world applications. APL Photonics 2024, 9, 080901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molaei-Yeznabad, A.; Shamloo, H.; Abedi, K.; Goharrizi, A.Y. Design and Optimization of a High-Performance CMOS-Compatible Bragg Grating Refractive Index-Based Sensor. Sens Imaging 2024, 25, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, B.; Rupam, T.H.; Chakraborty, A.; Saha, B.B. A comprehensive review on VOCs sensing using different functional materials: Mechanisms, modifications, challenges and opportunities. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2024, 196, 114365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; et al. Silicon-Nitride-Integrated Hybrid Optical Fibers: A New Platform for Functional Photonics. Laser & Photonics Reviews 2025, 19, 2400689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siew, S.Y.; et al. Review of Silicon Photonics Technology and Platform Development. J. Lightwave Technol., JLT vol. 39, 4374–4389. Available online: https://opg.optica.org/jlt/abstract.cfm?uri=jlt-39-13-4374. [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.A.; Kazanskiy, N.L.; Khonina, S.N.; Voronkov, G.S.; Grakhova, E.P.; Kutluyarov, R.V. A Review on Photonic Sensing Technologies: Status and Outlook. Biosensors 2023, 13, 568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazanskiy, N.L.; Butt, M.A.; Khonina, S.N. Carbon Dioxide Gas Sensor Based on Polyhexamethylene Biguanide Polymer Deposited on Silicon Nano-Cylinders Metasurface. Sensors 2021, 21, 378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombez, L.; Zhang, E.J.; Orcutt, J.S.; Kamlapurkar, S.; Green, W.M.J. Methane absorption spectroscopy on a silicon photonic chip. Optica, OPTICA 2017, 4, 1322–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.A.; Piramidowicz, R. Integrated Photonic Sensors for the Detection of Toxic Gasses—A Review. Chemosensors 2024, vol. 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, D.J.; Black, N.C.G.; Castanon, E.G.; Melios, C.; Hardman, M.; Kazakova, O. Frontiers of graphene and 2D material-based gas sensors for environmental monitoring. 2D Mater. 2020, 7, 032002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, N.A.; Alexeree, S.M.; Obayya, S.S.A.; Swillam, M.A. Silicon-based double fano resonances photonic integrated gas sensor. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 24811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abood, I.; Soliman, S.E.; He, W.; Ouyang, Z. Topological Photonic Crystal Sensors: Fundamental Principles, Recent Advances, and Emerging Applications. Sensors 2025, 25, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, X.; Yang, L. Optothermal dynamics in whispering-gallery microresonators. Light Sci Appl 2020, 9, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonacci, G.; Goyvaerts, J.; Zhao, H.; Baumgartner, B.; Lendl, B.; Baets, R. Ultra-sensitive refractive index gas sensor with functionalized silicon nitride photonic circuits. APL Photonics 2020, 5, 081301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Wei, H.; Tang, G.; Cao, B.; Chen, K. Advanced Crystallization Methods for Thin-Film Lithium Niobate and Its Device Applications. Materials (Basel) 2025, 18, 951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.A.Z.; Oehlschlaeger, M.A. Artificial Intelligence in Gas Sensing: A Review. ACS Sens. 2025, 10, 1538–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khonina, S.; Kazanskiy, N. Environmental Monitoring: A Comprehensive Review on Optical Waveguide and Fiber-Based Sensors. Biosensors 2022, 12, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.A. Dielectric Waveguide-Based Sensors with Enhanced Evanescent Field: Unveiling the Dynamic Interaction with the Ambient Medium for Biosensing and Gas-Sensing Applications—A Review. Photonics 2024, 11, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, V.; Rashmi, R.; Khera, S. Optical Gas Sensors; 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wusiman, M.; Taghipour, F. Methods and mechanisms of gas sensor selectivity. Critical Reviews in Solid State and Materials Sciences 2022, 47, 416–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgués, J.; Jiménez-Soto, J.M.; Marco, S. Estimation of the limit of detection in semiconductor gas sensors through linearized calibration models. Analytica Chimica Acta 2018, 1013, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Bi, M.; Xiao, Q.; Gao, W. Ultra-fast response and highly selectivity hydrogen gas sensor based on Pd/SnO2 nanoparticles. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 3157–3169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.A.; Juchniewicz, M.; Słowikowski, M.; Kozłowski, Ł.; Piramidowicz, R. Mid-Infrared Photonic Sensors: Exploring Fundamentals, Advanced Materials, and Cutting-Edge Applications. Sensors (Basel) 2025, 25, 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Martínez, E.E.; Zamarreño, C.R.; Matias, I.R. Resonance-Based Optical Gas Sensors. IEEE Sensors Reviews 2025, 2, 349–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; et al. On-Chip Optical Gas Sensors Based on Group-IV Materials. ACS Photonics 2020, 7, 2923–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranacher, C.; Tortschanoff, A.; Consani, C.; Moridi, M.; Grille, T.; Jakoby, B. Photonic Gas Sensor Using a Silicon Strip Waveguide. Proceedings 2017, 1, 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Shim, J.; Kim, I.; Kim, S.K.; Geum, D.-M.; Kim, S. Thermally tunable microring resonators based on germanium-on-insulator for mid-infrared spectrometer. APL Photonics 2024, 9, 106109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; et al. Versatile Lithium Niobate Platform for Photoacoustic/Thermoelastic Gas Sensing and Photodetection. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.A. Integrated Photonic Sensors with Enhanced Evanescent Field: Unveiling the Dynamic Interaction with the Ambient Medium. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, K.; Malviya, N.; Kumar, A. Silicon Subwavelength Grating Slot Waveguide based Optical Sensor for Label Free Detection of Fluoride Ion in Water. IETE Technical Review 2023, 41, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yallew, H.D.; et al. Sub-ppm Methane Detection with Mid-Infrared Slot Waveguides. ACS Photonics 2023, 10, 4282–4289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, Y.; et al. On-chip near-infrared multi-gas sensing using chalcogenide anti-resonant hollow-core waveguides. Lab Chip 2025, 25, 1801–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonacci, G.; Goyvaerts, J.; Zhao, H.; Baumgartner, B.; Lendl, B.; Baets, R. Ultra-sensitive refractive index gas sensor with functionalized silicon nitride photonic circuits. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.04260arXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milvich, J.; Kohler, D.; Freude, W.; Koos, C. Integrated phase-sensitive photonic sensors: a system design tutorial. Adv. Opt. Photon., AOP 2021, 13, 584–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Shamy, R.S.; Swillam, M.A.; ElRayany, M.M.; Sultan, A.; Li, X. Compact Gas Sensor Using Silicon-on-Insulator Loop-Terminated Mach–Zehnder Interferometer. Photonics 2022, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, D.; Bienstman, P. Study on the limit of detection in MZI-based biosensor systems. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 5767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; et al. WMS-based near-infrared on-chip acetylene sensor using polymeric SU8 Archimedean spiral waveguide with Euler S-bend. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2023, 302, 123020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, X.; Deng, S.; Wei, Z.; Wang, F.; Tan, C.; Meng, H. Ammonia Gas Sensor Based on Graphene Oxide-Coated Mach-Zehnder Interferometer with Hybrid Fiber Structure. Sensors 2021, 21, 3886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkinson, J.; Tatam, R.P. Optical gas sensing: a review. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2012, 24, 012004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plößl, A.; Kräuter, G. Silicon-on-insulator: materials aspects and applications. Solid-State Electronics 2000, 44, 775–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanti, F.; et al. Integrated photonic passive building blocks on silicon-on-insulator platform. in Photonics, MDPI. 2024, p. 494. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2304-6732/11/6/494.

- Shekhar, S.; et al. Roadmapping the next generation of silicon photonics. Nat Commun 2024, 15, 751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- [49] “Silicon-on-Insulator for Silicon Photonics. Photonics On Crystals. Available online: https://poc.com.sg/silicon-photonics/silicon-on-insulator/.

- Butt, M.A.; Akca, B.I.; Mateos, X. Integrated Photonic Biosensors: Enabling Next-Generation Lab-on-a-Chip Platforms. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kazanskiy, N.L.; Khonina, S.N.; Butt, M.A. Advancement in Silicon Integrated Photonics Technologies for Sensing Applications in Near-Infrared and Mid-Infrared Region: A Review. Photonics 2022, 9, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudenko, T.E.; Nazarov, A.N.; Lysenko, V.S. The advancement of silicon-on-insulator (SOI) devices and their basic properties. Semiconductor Physics, Quantum Electronics & Optoelectronics 2020, vol. 23. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Alexei-Nazarov/publication/344856636_The_advancement_of_silicon-on-insulator_SOI_devices_and_their_basic_properties/links/640a0740bcd7982d8d6e975b/The-advancement-of-silicon-on-insulator-SOI-devices-and-their-basic-properties.pdf.

- Blasco-Solvas, M.; et al. Silicon Nitride Building Blocks in the Visible Range of the Spectrum. J. Lightwave Technol., JLT vol. 42, 6019–6027. Available online: https://opg.optica.org/jlt/abstract.cfm?uri=jlt-42-17-6019. [CrossRef]

- Buzaverov, K.; et al. Silicon Nitride Integrated Photonics from Visible to Mid-Infrared Spectra. Laser & Photonics Reviews 2024, vol. 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzaverov, K.A.; et al. Silicon Nitride Integrated Photonics from Visible to Mid-Infrared Spectra. Laser & Photonics Reviews 2024, 18, 2400508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchiorre, L.; et al. Study and Characterization of Silicon Nitride Optical Waveguide Coupling with a Quartz Tuning Fork for the Development of Integrated Sensing Platforms. Sensors 2025, 25, 3663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corato-Zanarella, M.; Ji, X.; Mohanty, A.; Lipson, M. Absorption and scattering limits of silicon nitride integrated photonics in the visible spectrum. Opt. Express, OE 2024, 32, 5718–5728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucio, T.D.; et al. Silicon Nitride Photonics for the Near-Infrared. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Quantum Electronics 2020, 26, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Thomas, D.A.; et al. Single mode, distributed feedback interband cascade lasers grown on Si for gas sensing. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2025, 126, 031102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, C.; Fu, D.; Jin, Y.; Han, Y. Recent Progress in III–V Photodetectors Grown on Silicon. Photonics 2023, 10, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papatryfonos, K.; et al. Low-Defect Quantum Dot Lasers Directly Grown on Silicon Exhibiting Low Threshold Current and High Output Power at Elevated Temperatures. Advanced Photonics Research 2025, 6, 2400082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; et al. Innovative Integration of Dual Quantum Cascade Lasers on Silicon Photonics Platform. Micromachines 2024, 15, 1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Realising high-performance sensors with heterogeneous integration—Compound Semiconductor News. Compound Semiconductor. Available online: https://compoundsemiconductor.net/article/120720/Realising high-performance sensors with heterogeneous integration—Compound Semiconductor News.

- Shi, B.; Dummer, M.; McGivney, M.; Brunelli, S.S.; Oakley, D.; Klamkin, J. “Heterogeneous Integration of Large-Area InGaAs SWIR Photodetectors on 300 mm CMOS-Compatible Si Substrates”.

- He, H.; et al. Monolithic Integration of GaN-Based Transistors and Micro-LED. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Chen, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Xu, X.; Xu, J.-B. Enhancing light-matter interaction in 2D materials by optical micro/nano architectures for high-performance optoelectronic devices. InfoMat 2021, 3, 36–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqaydi, M.; et al. Gas sensing capabilities of MoS2 and WS2: theoretical and experimental study. Emergent Materials 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Jiang, C.; Wei, S. Gas sensing in 2D materials. Applied Physics Reviews 2017, 4, 021304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, N.J.; Basumatary, I.; Kolli, C.S.R.; Sahatiya, P. Current trends and emerging opportunities for 2D materials in flexible and wearable sensors. Chemical Communications 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, H.-S.; Wang, Y.; Liu, C.; Wang, T.; Huo, M. The elemental 2D materials beyond graphene potentially used as hazardous gas sensors for environmental protection. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2022, 423, 127148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Liu, J.; Yang, H.; Huang, B.; Zeng, G. Research on Tunable SPR Sensors Based on WS2 and Graphene Hybrid Nanosheets. Photonics 2022, vol. 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Khan, K.; Zou, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y. Recent Advances in Emerging 2D Material-Based Gas Sensors: Potential in Disease Diagnosis. Advanced Materials Interfaces 2019, 6, 1901329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.K.; et al. Suspended graphene arrays for gas sensing applications. 2D Mater. 2020, 8, 025006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gecim, G.; Ozekmekci, M.; Fellah, M.F. Ga and Ge-doped graphene structures: A DFT study of sensor applications for methanol. Computational and Theoretical Chemistry 2020, 1180, 112828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollaamin, F.; Monajjemi, M. Transition metal (X = Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn)-doped graphene as gas sensor for CO2 and NO2 detection: a molecular modeling framework by DFT perspective. J Mol Model 2023, 29, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, S.; Bereczki, A.; Habib, M.; Costa, I.; Cardozo, O. High-performance plasmonics nanostructures in gas sensing: a comprehensive review. Med Gas Res 2024, 15, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proença, M.; et al. New Parameter for Benchmarking Plasmonic Gas Sensors Demonstrated with Densely Packed Au Nanoparticle Layers. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2024, 16, 57832–57842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Chen, C.; Zhang, Y.; Bai, B.; Tang, S. A High-Sensitivity Methane Sensor with Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance Behavior in an Improved Hexagonal Gold Nanoring Array. Sensors 2019, 19, 4803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.; Guo, H.; Ge, L.; Sassa, F.; Hayashi, K. Inkjet-Printed Localized Surface Plasmon Resonance Subpixel Gas Sensor Array for Enhanced Identification and Visualization of Gas Spatial Distributions from Multiple Odor Sources. Sensors (Basel) 2024, 24, 6731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, Z.; Cai, C.; Yang, Z.; Qi, Z.-M. Surface plasmon resonance gas sensor with a nanoporous gold film. Opt. Lett., OL 2022, 47, 4155–4158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karki, B.; Trabelsi, Y.; Sarkar, P.; Pal, A.; Uniyal, A. Tuning sensitivity of surface plasmon resonance gas sensor based on multilayer black phosphorous. Mod. Phys. Lett. B 2025, 39, 2450364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayed, F.A.; Elsayed, H.A.; Mehaney, A.; Aly, A.H. Enhanced Angular Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensor Featuring Ag Nanoparticles Embedded Within a MoS2 Hosting Medium. Plasmonics 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proença, M.; et al. New Parameter for Benchmarking Plasmonic Gas Sensors Demonstrated with Densely Packed Au Nanoparticle Layers. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2024, 16, 57832–57842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karki, B.; Alsubaie, A.S.; Sarkar, P.; Sharma, M.; Ali, N.B. Detection of Skin, Cervical, and Breast Cancer Using Au–Ag Alloy and WS2-Based Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensor. Plasmonics 2025, 20, 3105–3116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boes, A.; et al. Lithium niobate photonics: Unlocking the electromagnetic spectrum. Science 2023, vol. 379, eabj4396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; et al. Recent development in integrated Lithium niobate photonics. Advances in Physics: X 2024, 9, 2322739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Feng, H.; Wang, C.; Ren, W. On-chip photothermal gas sensor based on a lithium niobate rib waveguide. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2024, 405, 135392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churaev, M.; et al. A heterogeneously integrated lithium niobate-on-silicon nitride photonic platform. Nat Commun 2023, vol. 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, Y.; Zheng, L.; Steinbach, L.; Günther, A.; Schneider, A.; Roth, B. Low-cost scalable fabrication of functionalized optical waveguide arrays for gas sensing application. Int J Adv Manuf Technol 2025, 138, 617–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasanna Kumaar, S.; Sivasubramanian, A. Analysis of BCB and SU 8 photonic waveguide in MZI architecture for point-of-care devices. Sensors International 2023, 4, 100207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Keppler, N.; Zhang, H.; Behrens, P.; Roth, B. Planar Polymer Optical Waveguide with Metal-Organic Framework Coating for Carbon Dioxide Sensing. Advanced Materials Technologies 2022, vol. 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalerao, O.; et al. High-sensitivity polymer-based bimodal plasmonic refractive index sensors with polymer cladding. Optics Express 2025, 33, 9813–9824. Available online: https://opg.optica.org/abstract.cfm?uri=oe-33-5-9813. [CrossRef]

- Kumaar, S.P.; Sivasubramanian, A. Analysis of BCB and SU 8 photonic waveguide in MZI architecture for point-of-care devices. Sensors International 2023, 4, 100207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, H.; Kanbara, H.; Koga, M.; Kubodera, K. Third-order nonlinear optical properties of As2S3 chalcogenide glass. J. Appl. Phys. 1993, 74, 3683–3687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, K.; et al. Supercontinuum generation in As2S3 chalcogenide waveguide pumped by all-fiber structured dual-femtosecond solitons. Optics Express 2023, 31, 29440–29451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, B.C.; Tran, B.T.L.; Van, L.C. Mid-infrared supercontinuum generation in As2S3-circular photonic crystal fibers pumped by 4.5 µm and 6 µm femtosecond lasers. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B, JOSAB 2024, 41, E1–E7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Xia, D.; Zhao, X.; Wan, L.; Li, Z. Hybrid-integrated chalcogenide photonics. gxjzz 2023, 4, 503–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanavas, T.; Grayson, M.; Xu, B.; Zohrabi, M.; Park, W.; Gopinath, J.T. Cascaded forward Brillouin lasing in a chalcogenide whispering gallery mode microresonator. APL Photonics 2022, vol. 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Yang, L.; Xia, K.; Yang, P.; Wang, R.P.; Xu, P. Exceeding two octave-spanning supercontinuum generation in integrated As2S3 waveguides pumped by a 2 μm fiber laser. Optics & Laser Technology 2024, 177, 111065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrianov, A.V.; Marisova, M.P.; Anashkina, E.A. Thermo-Optical Sensitivity of Whispering Gallery Modes in As2S3 Chalcogenide Glass Microresonators. Sensors 2022, 22, 4636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramola, A.; Shakya, A.K.; Kumar, V.; Bergman, A. Recent Advances in Photonic Crystal Fiber-Based SPR Biosensors: Design Strategies, Plasmonic Materials, and Applications. Micromachines (Basel) 2025, 16, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available, A.O. 360042305154-Waveguide-FEEM.

- Gemo, E. The design and analysis of novel integrated phase-change photonic memory and computing devices. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 6 meanings of Te and TM in rectangular waveguide. DOLPH MICROWAVE. Available online: https://www.dolphmicrowave.com/default/6-meanings-of-te-and-tm-in-rectangular-waveguide/.

- Kazanskiy, N.L.; Butt, M.A.; Khonina, S.N. 2D-Heterostructure Photonic Crystal Formation for On-Chip Polarization Division Multiplexing. Photonics 2021, vol. 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, N.; et al. Design of On-Chip Multi-Slot Chalcogenide Waveguide for Mid-Infrared Methane Sensing. Microwave and Optical Technology Letters 2024, vol. 66, e70036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khafagy, M.; Khafagy, M.; Hesham, P.; Swillam, M.A. On-Chip Silicon Bragg-Grating-Waveguide-Based Polymer Slot for Gas Sensing. Photonics 2025, vol. 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faghihi, V.; Goodarzi, R. Silicon ridge waveguide for trace gas detection. Thin films 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Sultan, A.; Sabry, Y.M.; Samir, A.; El-Aasser, M.A. Mirror-terminated Mach-Zehnder interferometer based on SiNOI slot and strip waveguides for sensing applications using visible light. Front. Nanotechnol. 2023, vol. 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonacci, G.; Goyvaerts, J.; Zhao, H.; Baumgartner, B.; Lendl, B.; Baets, R. Ultra-sensitive refractive index gas sensor with functionalized silicon nitride photonic circuits. APL photonics 2020, vol. 5. Available online: https://pubs.aip.org/aip/app/article/5/8/081301/123341. [CrossRef]

- Deleau, C.; Seat, H.C.; Bernal, O.; Surre, F. High-sensitivity integrated SiN rib-waveguide long period grating refractometer. Photon. Res., PRJ 2022, 10, 564–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.A.; et al. Investigation of Modal Characteristics of Silicon Nitride Ridge Waveguides for Enhanced Refractive Index Sensing. Micromachines 2025, 16, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammouti, A.; et al. Etching parameter optimization of photonic integrated waveguides based on chalcogenide glasses for near- and mid-infrared applications. Opt. Mater. Express, OME 2025, 15, 775–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.; et al. Second-harmonic generation in periodically-poled thin film lithium niobate wafer-bonded on silicon. Opt. Express, OE 2016, 24, 29941–29947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; et al. Mid-Infrared Highly Efficient, Broadband, and Flattened Dispersive Wave Generation via Dual-Coupled Thin-Film Lithium-Niobate-on-Insulator Waveguide. Applied Sciences 2022, vol. 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, L.; Yang, S.; Shi, R.; Fu, Y.; Su, J.; Wu, C. Polymer Waveguide Coupled Surface Plasmon Refractive Index Sensor: A Theoretical Study. Photonic Sens 2020, 10, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negm, N.; et al. Graphene Thermal Infrared Emitters Integrated into Silicon Photonic Waveguides. ACS Photonics 2024, 11, 2961–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, W.; Miller, L.; Zhao, F. Numerical Study of Graphene/Au/SiC Waveguide-Based Surface Plasmon Resonance Sensor. Biosensors 2021, 11, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Shahbazi, M.; Xing, K.; Tesfamichael, T.; Motta, N.; Qi, D.-C. Highly Sensitive NO2 Gas Sensors Based on MoS2@MoO3 Magnetic Heterostructure. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdiviezo, J.H.M.; Torchia, G.A. Design and development of integrated sensors under the silicon on insulator (SOI) platform for applications in the near/mid-infrared (NIR/MIR) band. in Nanoengineering: Fabrication, Properties, Optics, Thin Films, and Devices XXI, SPIE, Oct. 2024, pp. 77–90. [CrossRef]

- Valdiviezo, J.H.M.; Torchia, G.A. Design and development of integrated sensors under the silicon on insulator (SOI) platform for applications in the near/mid-infrared (NIR/MIR) band. In Nanoengineering: Fabrication, Properties, Optics, Thin Films, and Devices XXI; SPIE, 2024; pp. 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Zhu, B.; Zhang, Z. High Sensitivity Temperature Sensor Based on Harmonic Vernier Effect. Photonic Sens 2023, 13, 230204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, S.; Jiang, X.; Jiang, D. SOI-based parallel-ring microresonator for simultaneous sensing of refractive index and temperature. Appl. Opt., AO 2025, 64, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uchida, Y.; Arakawa, T.; Higo, A.; Ishizaka, Y. Silicon Microring Resonator Biosensor for Detection of Nucleocapsid Protein of SARS-CoV-2. Sensors 2024, 24, 3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, S.; Singhal, S.; Paithankar, P.; Varshney, S.K. Microring Resonators and its Applications. Indian Journal of Pure & Applied Physics (IJPAP) 2023, 61, 601–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemieux-Leduc, C.; Guertin, R.; Bianki, M.-A.; Peter, Y.-A. All-polymer whispering gallery mode resonators for gas sensing. Optics express 2021, 29, 8685–8697. Available online: https://opg.optica.org/abstract.cfm?uri=oe-29-6-8685. [CrossRef]

- Bianki, M.-A.; Guertin, R.; Lemieux-Leduc, C.; Peter, Y.-A. Suspended whispering gallery mode resonators made of different polymers and fabricated using drop-on-demand inkjet printing for gas sensing applications. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2024, 420, 136460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; et al. A Silicon Microring Resonator for Refractive Index Carbon Dioxide Gas Sensing. ACS Sens. 2025, 10, 4938–4944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Shi, B.; Guo, Y.; Han, B.; Zhang, Y. Polydimethylsiloxane self-assembled whispering gallery mode microbottle resonator for ethanol sensing. Optical Materials 2020, 107, 110024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazuryk, J.; Paszke, P.; Pawlak, D.A.; Kutner, W.; Sharma, P.S. Fabrication, Characterization, and Sensor Applications of Polymer-Based Whispering Gallery Mode Microresonators. ACS Sens. 2025, 10, 5314–5338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, Z.A.; Almawgani, A.H.M.; Gumaih, H.S.; Adam, Y.S. Plasmonic Multi-resonator Perfect Absorber with Narrowband Modes for Optical Sensing. Plasmonics 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salama, N.A.; Obayya, S.S.A.; Alexeree, S.M.; Swillam, M.A. Ultra-sensitive gas sensor using Fano resonance in hybrid nano-bar/nano-elliptic dielectric metasurface. in Metamaterials XIV, SPIE, Jun. 2023, pp. 113–117. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; et al. Multi-Band Terahertz Metamaterial Absorber Integrated with Microfluidics and Its Potential Application in Volatile Organic Compound Sensing. Electronics 2025, 14, 2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.A. High Sensitivity Design for Silicon-On-Insulator-Based Asymmetric Loop-Terminated Mach–Zehnder Interferometer. Materials 2025, 18, 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Y.; Yan, B.; Qi, Y. SOI optical waveguide-based refractive index sensor using a multi-slot subwavelength grating Mach–Zehnder interferometer. Appl. Opt., AO 2025, 64, 5896–5902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Xing, Z.; Chen, X.; Cheng, Z.; Li, X.; Liu, T. Recent Progress in Waveguide-Integrated Graphene Photonic Devices for Sensing and Communication Applications. Front. Phys. 2020, vol. 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, T.; Chiang, K.S. Graphene-Based Ammonia-Gas Sensor Using In-Fiber Mach-Zehnder Interferometer. IEEE Photonics Technology Letters 2017, 29, 2035–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenjan, D.; Mahdi, B.; Yusr, H. Graphene Oxide-Coated Mach-Zehnder Interferometer Based Ammonia Gas Sensor. Nexo Revista Científica 2023, 36, 1132–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elrashidi, A.; Traversa, E.; Elzein, B. Highly sensitive ultra-thin optical CO2 gas sensors using nanowall honeycomb structure and plasmonic nanoparticles. Front. Energy Res. 2022, vol. 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illuminating the Future: The Promise and Challenges of Photonics | Synopsys Optical and Photonic Blog. Available online: https://www.synopsys.com/blogs/optical-photonic/illuminating-the-future-photonics.html.

- Tian, W.; Wang, Y.; Dang, H.; Hou, H.; Xi, Y. Photonic Integrated Circuits: Research Advances and Challenges in Interconnection and Packaging Technologies. Photonics 2025, 12, 821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-García, G.; Wang, L.; Yetisen, A.K.; Morales-Narváez, E. Photonic Solutions for Challenges in Sensing. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 25415–25420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawande, T.; Deshmukh, R.; Deshmukh, S. MEMS-based electronic nose system for measurement of industrial gases with drift correction methodology. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2023, 34, 105110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshahat, S.; Mohamed, Z.E.A.; Abd-Elnaiem, A.M.; Ouyang, Z.; Almokhtar, M. One-dimensional topological photonic crystal for high-performance gas sensor. Micro and Nanostructures 2022, 172, 207447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Bakr, M.; KANJ, H. Monitoring an ambient air parameter using a trained model. US20220333940A1, 20 Oct 2022. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/US20220333940A1/en.

- Maghrabi, M.M.T.; Bakr, M.H.; Kumar, S.; Elsherbeni, A.Z.; Demir, V. FDTD-Based Adjoint Sensitivity Analysis of High-Frequency Nonlinear Structures. IEEE Transactions on Antennas and Propagation 2020, 68, 4727–4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arfin, R.; Son, J.; Niegemann, J.; McGuire, D.; Bakr, M.H. Adjoint-Driven Inverse Design of a Quad-Spectral Metasurface Router for RGB-NIR Sensing. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakr, M.; Elsherbeni, A.; Demir, V. Adjoint Sensitivity Analysis of High Frequency Structures with MATLAB. Art. 2017. Available online: https://digital.library.tu.ac.th/tu_dc/frontend/Info/item/dc:137855.

- Yoon, M.; Shin, S.; Lee, S.; Kang, J.; Gong, X.; Cho, S.-Y. Scalable Photonic Nose Development through Corona Phase Molecular Recognition. ACS Sens. 2024, 9, 6311–6319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- M. ltd. Photonic Sensors & Detectors Market—Global Forecast 2025-2030. Available online: https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/6120239/photonic-sensors-and-detectors-market-global.

- Jannat, A.; Talukder, M.M.M.; Li, Z.; Ou, J.Z. Recent Advances in Flexible and Wearable Gas Sensors Harnessing the Potential of 2D Materials. Small Sci 2025, 5, 2500025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, B.; Wu, S.; Yang, Y.; Li, Q.; Tao, T.; Mao, S. Smart Gas Sensors: Recent Developments and Future Prospective. Nano-Micro Lett. 2024, 17, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref. # | Material Platform |

Device Architecture |

Sensing Gas | Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [107] | SOI | Slotted Bragg grating waveguide | CO2 | 14.4 pm/ppm |

| [109] | Slot and strip waveguide | Different gases | 1,320 nm/RIU | |

| [113] | Chalcogenide Glass (GeSbSe) | Waveguide | Different gases | N/A |

| [86] | Lithium Niobate (LN) | Rib waveguide | Different gases | N/A |

| [91] | PMMA with a ZIF-8 (MOF) coating | Ridge Waveguide | CO2 | N/A |

| [117] | Graphene | Waveguide | CO2 | N/A |

| [128] | SOI | Microring | CO2 | High |

| [112] | Racetrack Ring Resonator | Different gases | 116.3 nm/RIU to 143.3 nm/RIU | |

| [126] | All-polymer (SU-8) | Whispering Gallery Mode (WGM) Microdisk Resonator | Pentanoic Acid (and other VOCs) | High |

| [89] | Plasmonic metasurface (Silicon nano-cylinders on a gold layer) | Metasurface-based perfect absorber microdisks | CO2 | High |

| [41] | SOI | Loop-terminated Mach-Zehnder Interferometer (LT-MZI) | Different gases | 1070 nm/RIU |

| [44] | Graphene Oxide (GO) | Mach-Zehnder Interferometer (MZI) with a hybrid MMF-TCF-MMF structure | NH3 | High |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.