1. Introduction

Hyperbolic metamaterials (HMMs) are a widely studied research field in photonics and sensor technology due to their exceptional properties [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. They possess anisotropic dielectric tensors, which comprise transverse and longitudinal components. By manipulating the operating frequency of incident light, the dielectric tensors of HMMs can exhibit negative values, effectively enabling the HMM to act as a metal and generate surface plasmon resonance (SPR) at the interface between metal and dielectric. In wave vector space, the transverse and longitudinal components of the dielectric tensors of HMMs can also possess different signs, leading to richer dispersion properties than those of conventional metals. Furthermore, the properties of HMMs can be adjusted by modifying the components or fractions of the constituent materials [

6,

7,

8,

9], thereby rendering them highly versatile and suitable for use in diverse applications [

10,

11,

12].

Due to the exceptional properties of HMMs, they have found widespread use in plasmonic sensing that relies on the phenomenon of SPR. Conventional plasmonic sensors utilize metals next to the waveguiding system to couple waveguiding modes to the SPRs, resulting in a dip in transmission spectra when the energies of the guided modes are absorbed by the metals [

13,

14,

15,

16]. As SPRs are highly sensitive to changes in the surrounding refractive index (SRI), SPR sensors are effective in a variety of fields such as medical detection, food safety, and environmental monitoring [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. In recent years, HMMs have been employed to further enhance the performance of SPR sensors. For instance, Vasilantonakis et al. investigated deep-subwavelength guiding modes in HMMs with nanorods, demonstrating that HMMs can generate plasmonic polaritons and are strong candidates for sensors [

22,

23]. Cheng et al. proposed graphene-based HMMs to improve the sensitivity of plasmonic sensors for terahertz waves [

24]. Sreekanth et al. used HMMs to enhance the angular sensitivity of SPR sensors [

25] and utilized high-k modes to achieve extreme sensitivity biosensing [

26]. Guo et al. employed hyperbolic materials to enhance electromagnetically induced transparency [

27]. Yan et al. proposed a highly sensitive SPR sensor based on nanorod HMMs [

28]. However, these works typically require complex structures such as prisms or gratings to couple waves in free space to the surface for generating SPR, which require accurate fabrication and procedure and have generally low coupling efficiency. To solve this problem, side-polished fibers coated with HMMs were proposed to achieve plasmonic sensors. This configuration is compact, flexible, and significantly improves the sensitivity and figure of merit (FOM) of the sensor [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. Hu et al. realized a high-performance SPR fiber sensor with HMMs [

34,

35]. Li et al. achieved an optical fiber SPR biosensor with composite HMM and graphene [

36]. However, existing literature has primarily focused on a resonant coupling between guided modes and SPRs, which typically have low FOMs due to the mismatch of wavevectors. Even though they have high sensitivities, the low FOMs have limited the application of conventional HMM sensors.

To address the coupling problem and enhance the FOM, one potential solution is to directly utilize the guiding modes of an HMM structure [

22]. However, due to the highly dispersive nature of nano-structured materials, the Kramers-Kronig relation limits the ability of HMMs to serve as effective waveguides, as they tend to exhibit significant light absorption. Consequently, using electromagnetic waves to propagate inside the bulk HMMs is unlikely to yield viable functional sensors. Alternatively, photonic crystals (PtCs) represent a promising class of nanostructures capable of generating bandgaps and high Q-factor waveguides via line defects. Incorporating PtC structures into HMMs can reduce light absorption by the HMMs and enable the creation of high-performance photonic devices. This fusion of HMMs and PtCs presents an attractive avenue for photonic sensing research.

This article presents a novel approach to plasmonic nano-sensors by utilizing HMM waveguides that are constructed from two-dimensional arrays of HMM nanorods. The arrays form photonic bandgaps and are used to introduce line defects that function as waveguides for incident light when the operating frequency is within the bandgap. The HMMs used in the waveguides are made up of multiple layers of silver and titanium dioxide, and can be fabricated using electron beam lithography [

37]. The article investigates the photonic bandgap structures of HMM PtCs numerically, using effective medium theory for accurate simulation of optical properties. The results indicate that the sensor based on the HMM PtC waveguide has a high figure of merit (FOM). The proposed design integrates the plasmonic properties of HMMs and the bandgap properties of PtCs, leading to a high-FOM nano-sensor with a compact configuration. This nano-sensor has a wide range of potential applications in sensing temperature, pressure, or materials, and could benefit industries such as medicine and biotechnology.

2. Materials and Methods

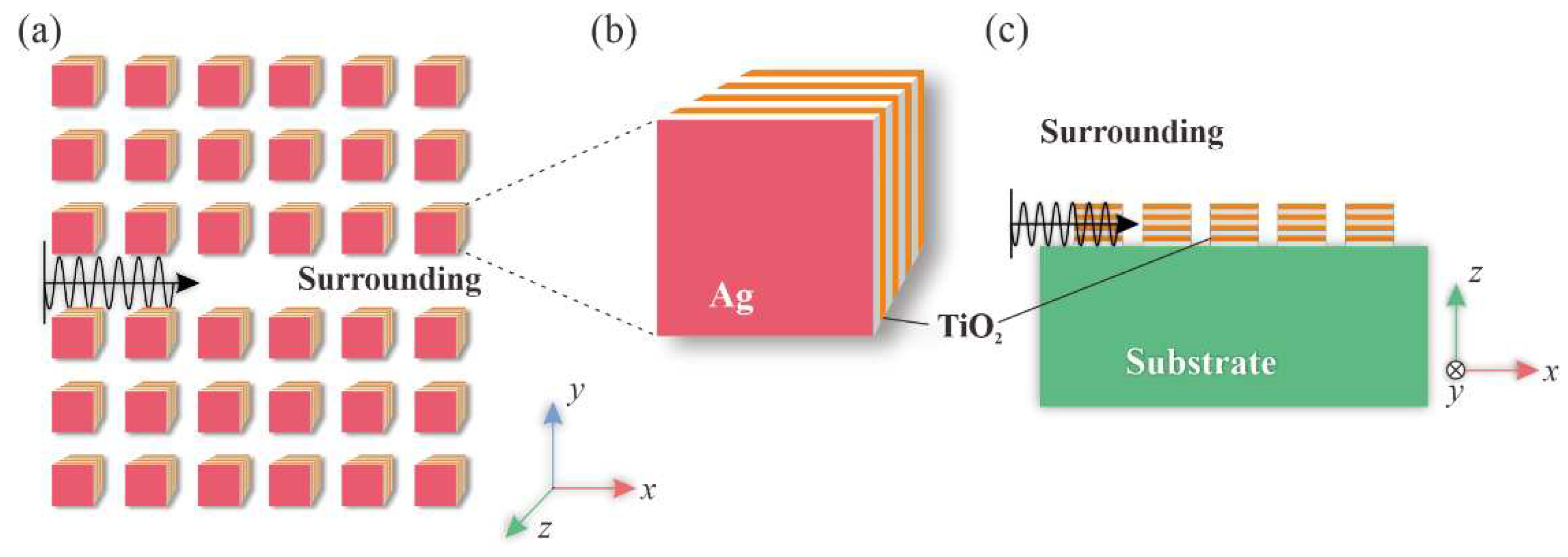

The proposed HMM waveguide consists of arrays of HMM nanorods in a dielectric surrounding environment, as depicted in

Figure 1. The HMM arrays form a photonic crystal with a lattice constant of

a = 0.2 μm. One array of HMM nanorods is removed to create a line defect, which serves as the waveguide for incident light. Each HMM nanorod has a side length of

r = 0.1 μm and is composed of Ag and TiO2 layers, with a thickness of

dm = 10 nm and

dd = 15 nm, respectively. There are eight layers in every HMM nanorod, with a filling fraction (of metal) of

f = 0.4. Numerical studies of the HMM arrays have been conducted using both the plane-wave expansion method and finite-element method, with the commercial software COMSOL Multiphysics. The study only considers TE waves with

Ez polarization, and as shown in the figure, the light waves propagate in the

x-

y plane. The transverse and longitudinal components of the effective permittivity of HMMs are denoted as

and

, respectively. In

Ez polarization, we have

and

. The fabrication of the system can be achieved using electron beam lithography, a widely used technique for fabricating arrays of nanorods [

37]. Compared to conventional HMM-enhanced SPR sensors based on fibers, the proposed waveguide is easier to fabricate as it lies on a planar substrate.

To ensure universality, we utilized the Drude model to describe the permittivity of Ag, while representing the refractive index of TiO

2 with a constant (

nTiO2 = 2.0951), which corresponds to the optical constant of TiO

2 at the wavelength of 0.8 μm. The waveguide system was placed on a glass substrate with an optical constant of

nglass = 1.440. The permittivity of Ag was obtained using the Drude model as follows:

where

,

,

and

are the high-frequency permittivity, the plasma angular frequency, the damping term, and the operating frequency, respectively. The parameters in Equation (1) were derived from experimental data of the permittivity of Ag [

38,

39] through data fitting, resulting in:

= 1.4447,

= 1.328×10

16 rad/s and

= 9.1269×10

13 rad/s. The permittivity of Ag obtained from Drude model fits experimental data very well.

In Equation (1), the imaginary part of Ag contributes significantly to the loss of waves propagating in the system. The alteration of the SRI causes a change in the electric field distribution, ultimately affecting the absorption of waves by the HMM waveguide. Propagating waves through a bulk Ag or HMM material is challenging due to high material loss and wave vector mismatch, which cannot satisfy the boundary conditions. However, the use of HMM arrays as a photonic crystal (PtC) can overcome this limitation and provide an effective waveguide system. The HMM PtC nanostructure system preserves the field enhancement properties of HMM while enabling efficient wave propagation. Moreover, the HMM waveguide system offers flexibility in parameters, plausible for various applications.

Since the thickness of the layers inside an HMM rod is much smaller than the wavelength of waves that propagate in the system, the optical property of HMM nanorods can be investigated using effective medium methods. According to the method, an HMM can be treated as having an isotropic permittivity tensor, with components

and

given by the following equations:

where

and

are the permittivities of Ag and TiO

2, respectively. Using Equations (2) and (3), we calculated the effective permittivity of the HMM as illustrated in

Figure 2. By altering the components or fractions of the HMM’s materials, we can adjust its optical properties. Based on the signs of

and

, we can categorize HMMs as (i) Effective Dielectric (

,

), (ii) Effective Metal (

,

), (iii) Type-I HMM (

,

), and (iv) Type-II HMM (

,

). The transition between these HMM types is an important area of inquiry in HMM research, as the different types of HMMs can exhibit unique wave propagation properties.

In

Figure 2, when the incident light’s operating frequency falls between 200 THz and 500 THz, the real part of the transverse components of the effective permittivities of HMMs

is positive, while the real part of the longitudinal components

is negative. This signifies that the HMMs are functioning as Type-I HMM. However, the signs of the components are not important for our waveguide system as long as there are gaps in the PtC structure, which means that the waveguide can operate properly. The dispersion relation shown in the figure is the mainstay for the sensor. As shown in the figure, the effective permittivity of the HMMs changes with the frequency, allowing the HMMs to enhance the sensitivity of the waveguide system. Note that the dispersion relation can be improved further by moving to a frequency region near the transition point of the HMMs, as the dispersion curve changes dramatically. However, the material loss (associated with the imaginary part of permittivity) is also high near the transition point. Therefore, additional optimization is required to balance the two factors that affect the waveguide system’s sensing performance. Overall, the dispersion of HMMs enhances the system’s sensitivity and provides additional versatility for adjusting its properties, making it an ideal platform for realizing high-performance sensors.

3. Results and Discussions

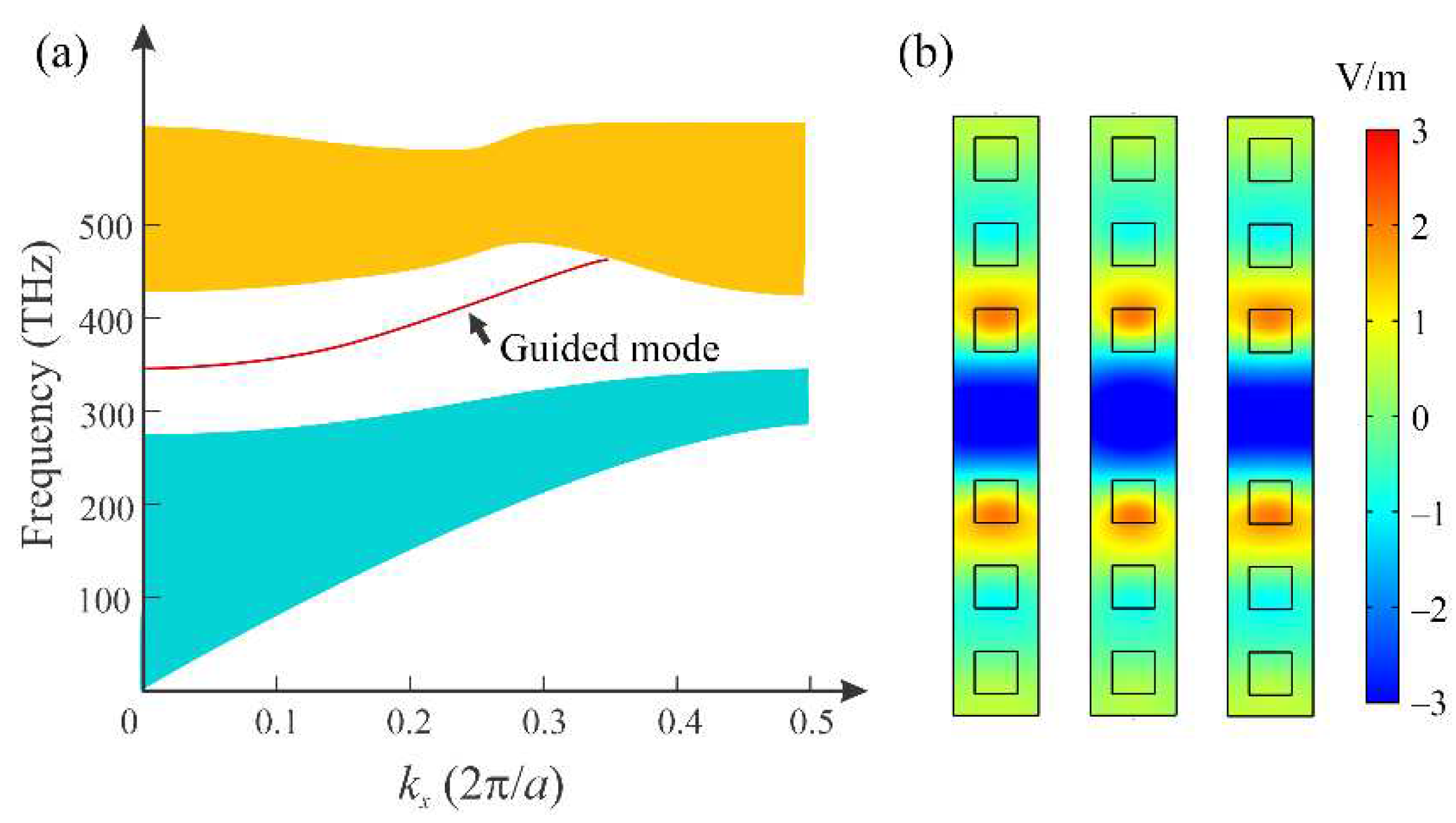

Figure 3(a) shows the band structure of the two-dimensional arrays of HMMs with an SRI of 1.33. The bands were computed using COMSOL Multiphysics software based on the finite-element method. Since the structure is periodic, only one column was required for the calculation. The obtained bands reveal a bandgap between the first and second band, within which a dispersion curve arises. This curve corresponds to the guided modes in the system. The lower cutoff frequency of the guided mode is approximately 345 THz, which marks the lower end of the dispersion curve. By adjusting the SRI, the cutoff frequency can be varied. In

Figure 3(b), the electric field (

Ez) profiles of the guided modes are depicted for

kx = 0, 0.1(2π/

a), and 0.2(2π/

a), while

ky = 0. The field profiles indicate the localization of the guided modes in the y direction. Note that in such a system, only a single guided mode can be supported. To achieve multi-mode operation, one can expand the line defect between the HMM arrays by removing more rows of HMM nanorods.

Based on the calculation result, all the eigenfrequencies have imaginary parts, which are not shown in the figure. The existence of imaginary parts in the eigenfrequencies indicates that all the modes will experience losses over time and their amplitude will decrease. These losses are mainly caused by the material loss of Ag. Moreover, changing the SRI will have an impact on both the imaginary and real parts of the guided modes, represented as

and

, respectively. If the waveguide is long enough, the transmission spectra of the sensor can be obtained by using the following equation:

where

is the transmission power,

is the angular frequency of the light source,

L is the length of the HMM waveguide. The working mechanism of conventional sensors typically follows Equation (4). However, in our work, the change of SRI not only modifies the output of Equation (4) but also causes the dispersion curve to change, leading to a further modification of the transmission spectra. This is where the HMM waveguide sensors have an advantage over conventional ones. In the subsequent discussion, we will provide a detailed explanation of how the transmission spectra of the system are affected by the change in SRI.

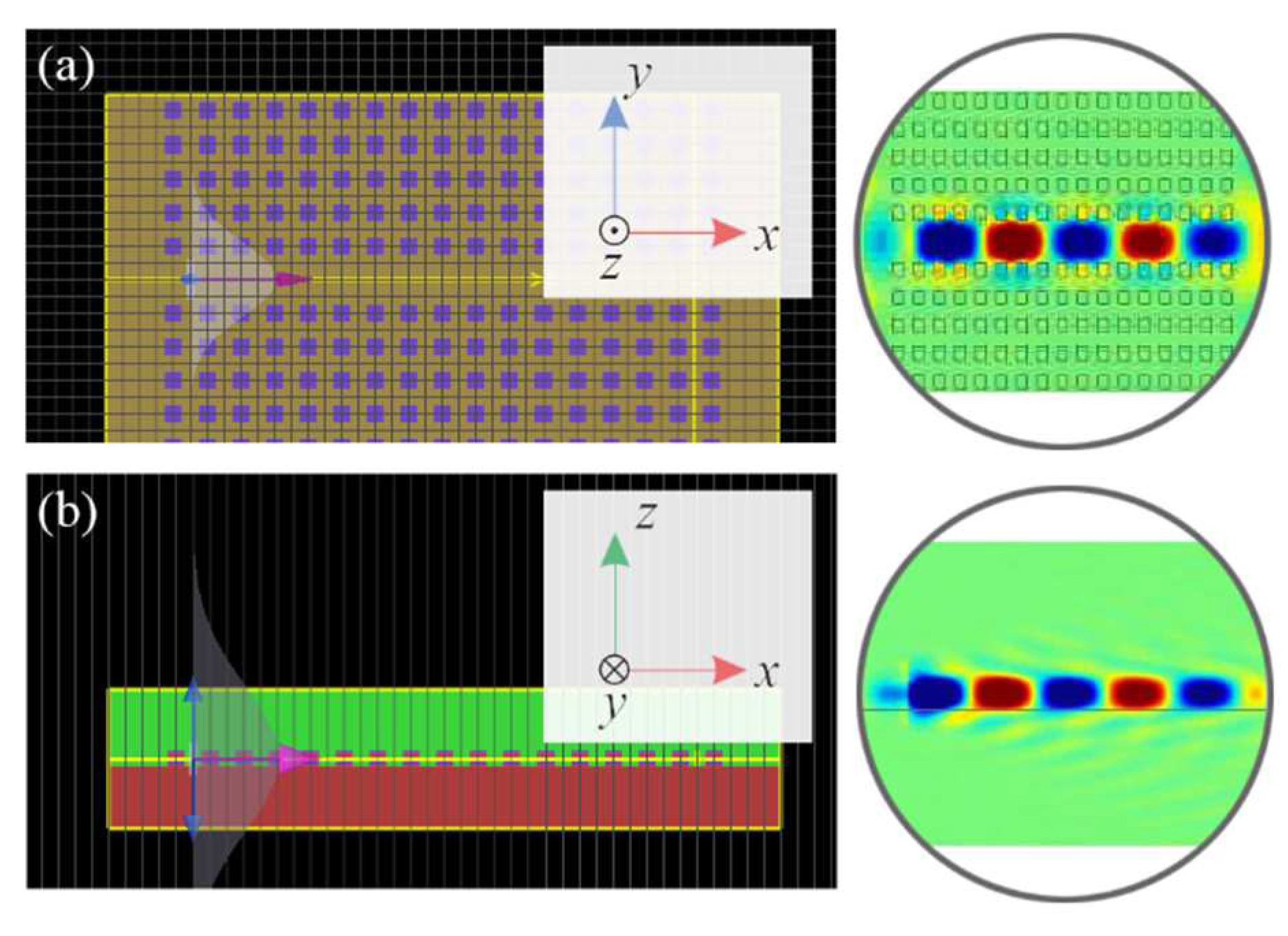

In the simulation presented above, we focused only on a two-dimensional model and neglected the substrate. We have confirmed that this model is accurate enough for our proposal by investigating the field distribution in the third dimension.

Figure 4 shows the electric field (

Ez) profiles in

x-y and

x-z planes from simulations using a three-dimensional model. The model employed the same parameters for the HMM arrays as shown in

Figure 3, and the HMM nanorods have a thickness of 0.1 μm. The field profiles demonstrate that the field can be localized in both the

y and

z directions without divergence. This result indicates that the standing wave condition can be achieved in the third dimension for the HMM waveguide system. Furthermore, additional simulations have confirmed that we can use a substrate material with the same refractive index as the SRI, and the guided mode can still propagate effectively within the waveguide without diffusion. These results demonstrate that the proposed sensor can be both compact and flexible, as the structure can be fabricated on a variety of substrates and still function properly. Additionally, the results suggest that the design of the sensor can be simplified by considering a 2D system instead of a 3D one.

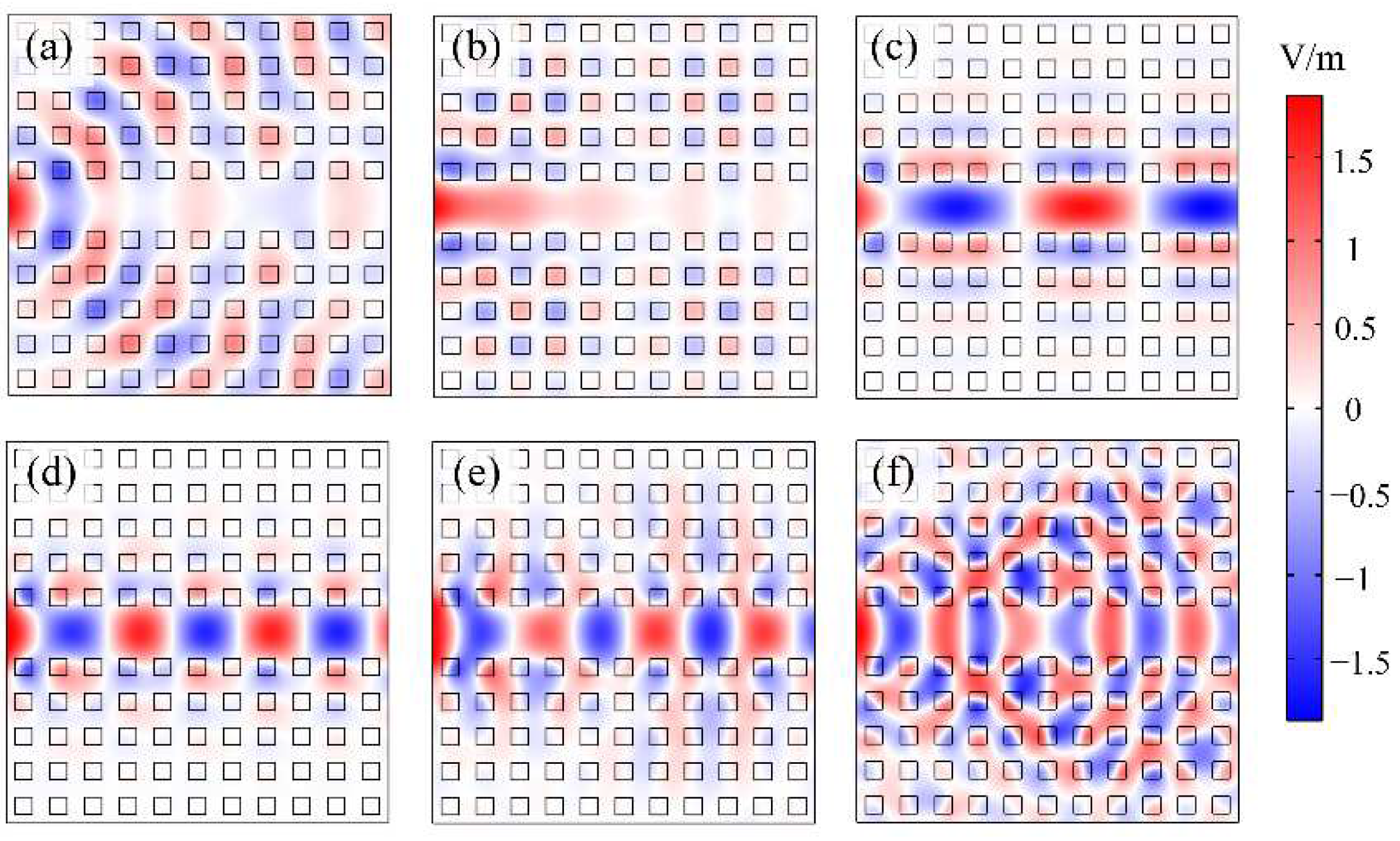

For different frequencies of the incident light, the waveguide indicates different properties in the guidance of waves, as shown in

Figure 5. There are total 11 columns of HMM nanorods have been used in

Figure 5, so the total length of the waveguide is 2.2 μm. As shown in

Figure 5(a), when the frequency of the incident light is 325 THz, which falls in the first band and is below the cutoff frequency, the propagation of light indicates non-localization and no guided modes exist. As a result, little energy has passed through the waveguide to the right end. In

Figure 5(b), the frequency of the incidence is 350 THz, which falls in the gap and is below the cutoff frequency, we can clearly see that the field decays exponentially. The HMM waveguide is in a “cutoff” state, blocking the forward propagation of waves. Additionally, near the cutoff frequency, the guided modes have very small wave vectors and low group velocities, e.g., the group velocity is approaching zero at the frequency of 345 THz. Therefore, only a small amount of energy from the incident light can successfully propagate toward the other end of the waveguide. Note that some of the energy of the incident light also has been absorbed by the HMM nanorods. At the frequencies of 375 THz and 425 THz, the wave can propagate in the waveguide to the other end, but their transmissions are different, which is related to the property of the waveguide in different frequencies. All the phenomena above can be explained by the dispersion curve shown in the band structure in

Figure 3. Consequently, modifying the dispersion curve means changing the propagation behavior of waves in the HMM waveguide.

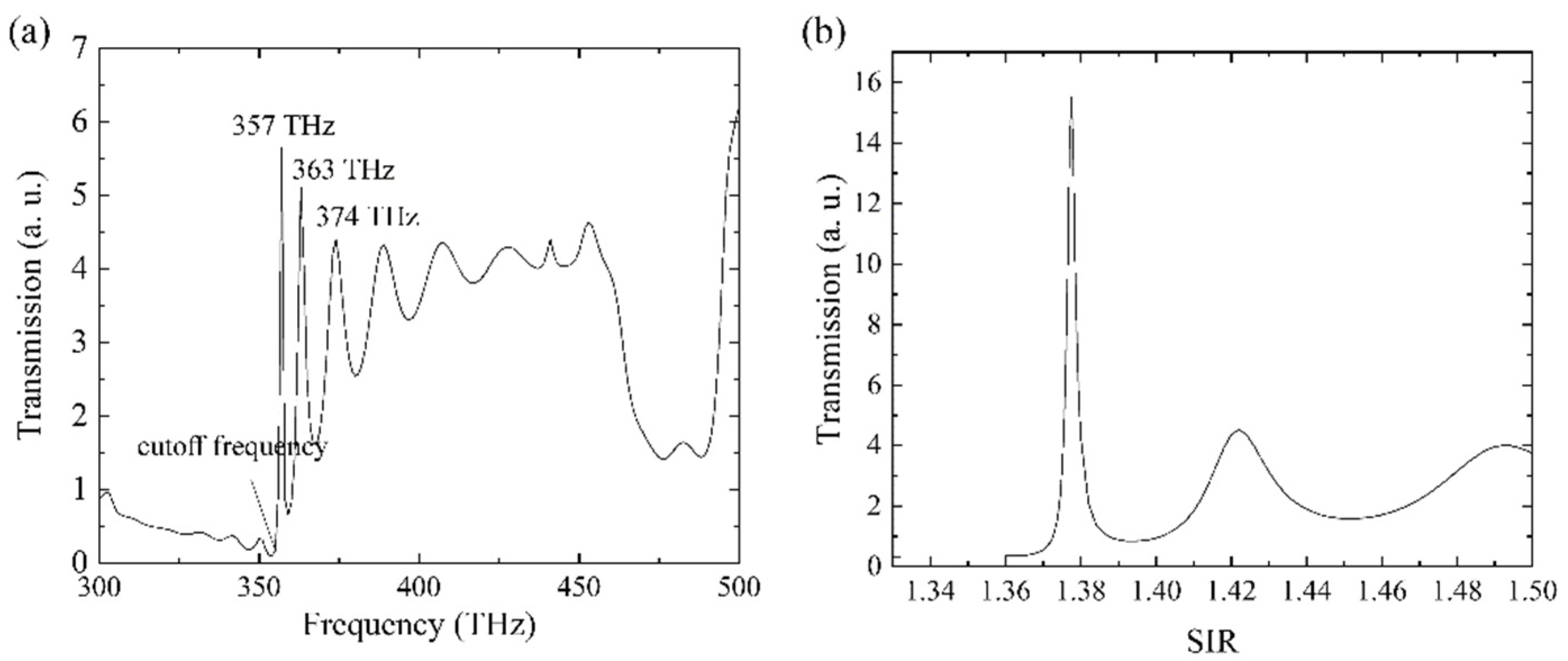

The full transmission spectrum is illustrated in

Figure 6(a), from which we can accurately determine the cutoff frequency of the waveguide to be approximately 355 THz. Below this frequency, the waveguide has very low transmission, as the incident light is either blocked due to the gap or undergoes diffusion propagation within the band. When the waveguide is working above the cutoff frequency, guided modes are generated, resulting in high transmission of the waveguide. The multiple peaks in the spectrum correspond to frequencies that satisfy the resonant condition of the Fabry-Perot (FP) cavity. The FP cavity is formed by the finite length of the waveguide, with the two ends of the waveguide functioning as reflectors. These transmission peaks are crucial for achieving sensors with high FOMs. To illustrate this point, we set the frequency of the incident light to 350 THz and obtained the transmission of the HMM waveguide at different SIRs, as shown in

Figure 6(b). Two factors play important roles in the propagation of light: the change in the dispersion curve of the guided mode following the change in the propagation behavior of light, and the energy absorbed by the materials, which reduces the transmission power of the waveguide. Modification of the SIR affects both of these factors, which is how the sensor operates.

Figure 6(b) shows that the sensing ability of the HMM PtC waveguide is excellent, with a significant change in transmission, particularly when the SIR is around 1.370 or 1.380. For example, when the SIR increases from 1.373 to 1.377, the transmission increases from 1.144 to 13.832, which represents a one-order-of-magnitude increase in transmission.

Conventional waveguides exhibit a theoretical red shift in their entire transmission spectrum as the SIR increases, but the effect is too small to be practically applicable. On the other hand, the HMM PtC waveguide has been improved through the combined effects of the dispersion properties of HMMs and PtCs. As a result, the nonlinear effect is considerably prominent. The sensitivity of the HMM PtC waveguide sensor (

S) can be defined as:

where

is the shift of wavelength,

is the shift of angular frequency, and

is the change of the SIR. Furthermore, the FOM of the system can be calculated by using the following equation:

where FWHM (full width at half-maximum) refers to the width of the transmission spectra of the HMM PtC waveguide sensor, measured at the point where the transmission reaches half of its maximum value.

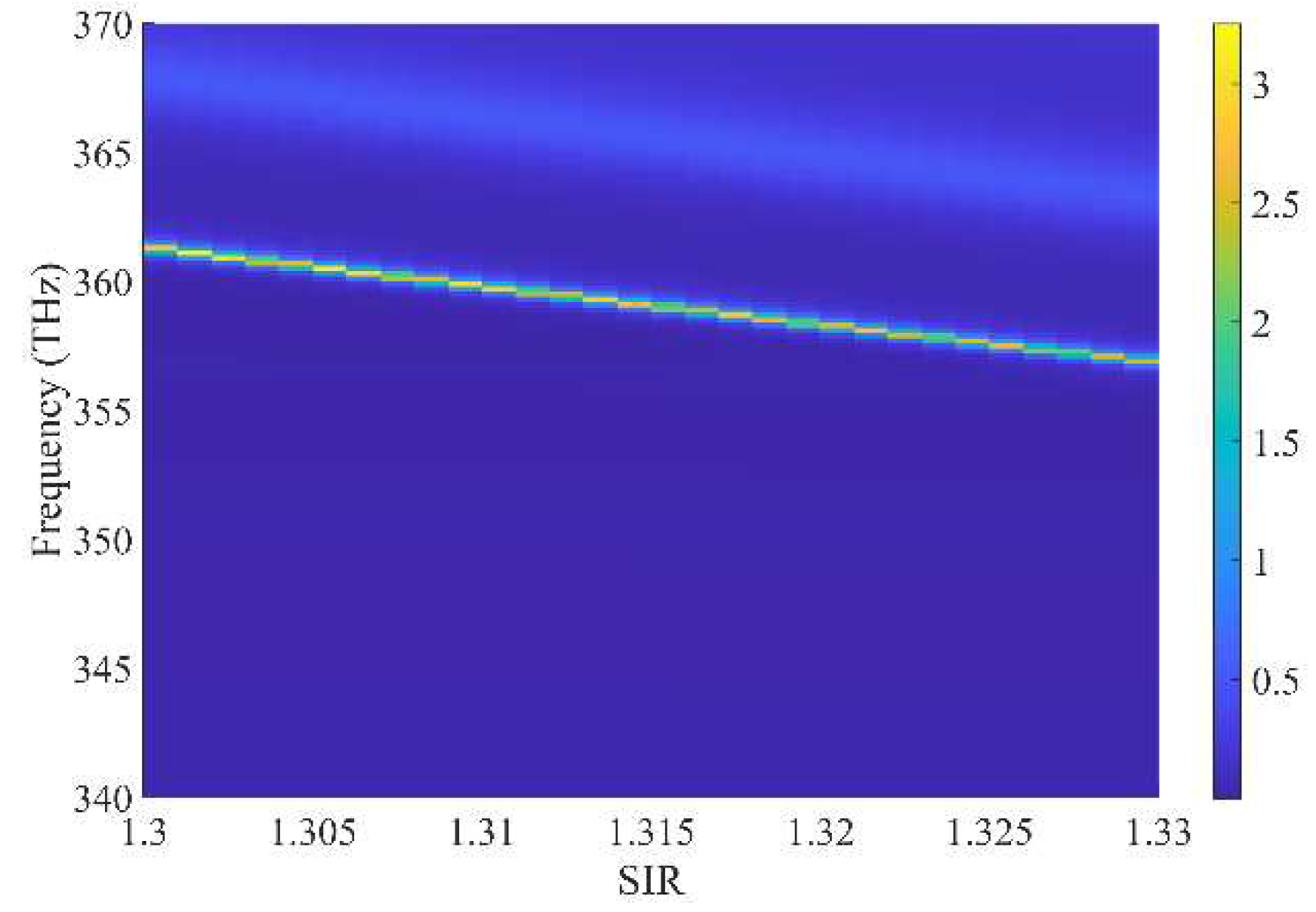

Figure 7 illustrates a more detailed relationship among transmission, frequency, and SIR. The

y-axis shows the transmission spectra for different SIRs, with two transmission peaks near 360 THz and 365 THz. Along the x-axis, as the SIR increases, the transmission peaks move to lower frequencies, and the whole transmission spectrum is red-shifted. According to the results, the average sensitivity and FOM of the HMM PtC waveguide sensor around 360 THz can be calculated based on Equations (4) and (5), respectively, which are 476.10 nm/RIU (RIU: refractive index unit) and 476.10 RIU

−1. The sensitivity appears to be not significant by comparing to conventional SPR sensors. However, we only use a waveguide with a length of 0.8 μm here, which is much shorter than the centimeter-scale lengths of conventional SPR sensors. The longer the waveguide, the larger the sensitivity will be since the absorption will be more significant. On the other hand, the FOM of the HMM PtC waveguide sensor is very promising compared to conventional sensors. Usually, only resonant cavities can provide such large FOMs, but cavities are not suitable for sensing because the area of SIR for sensing is too small, requiring very precise fabrication.

Table 1 shows a comparison of different types of sensors. After comparing the performance of the HMM PtC waveguide sensor with conventional fiber sensors, it is evident that the former has a much larger FOM and is therefore superior in sensing. Although conventional fiber sensors have high sensitivity, their small FOM limits their performance. For example, changing the SIR at a specific frequency may not significantly modify the transmission due to the large FWHM of the sensors. The drawback can be addressed by attaining higher FOMs using an alternative configuration, such as the HMM PtC waveguide. Indeed, the utilization of the guided modes in HMM waveguides allows for the direct coupling of electromagnetic waves to the highly dispersive material, making it a more efficient method than the side-coupling of fiber modes to SPR modes.

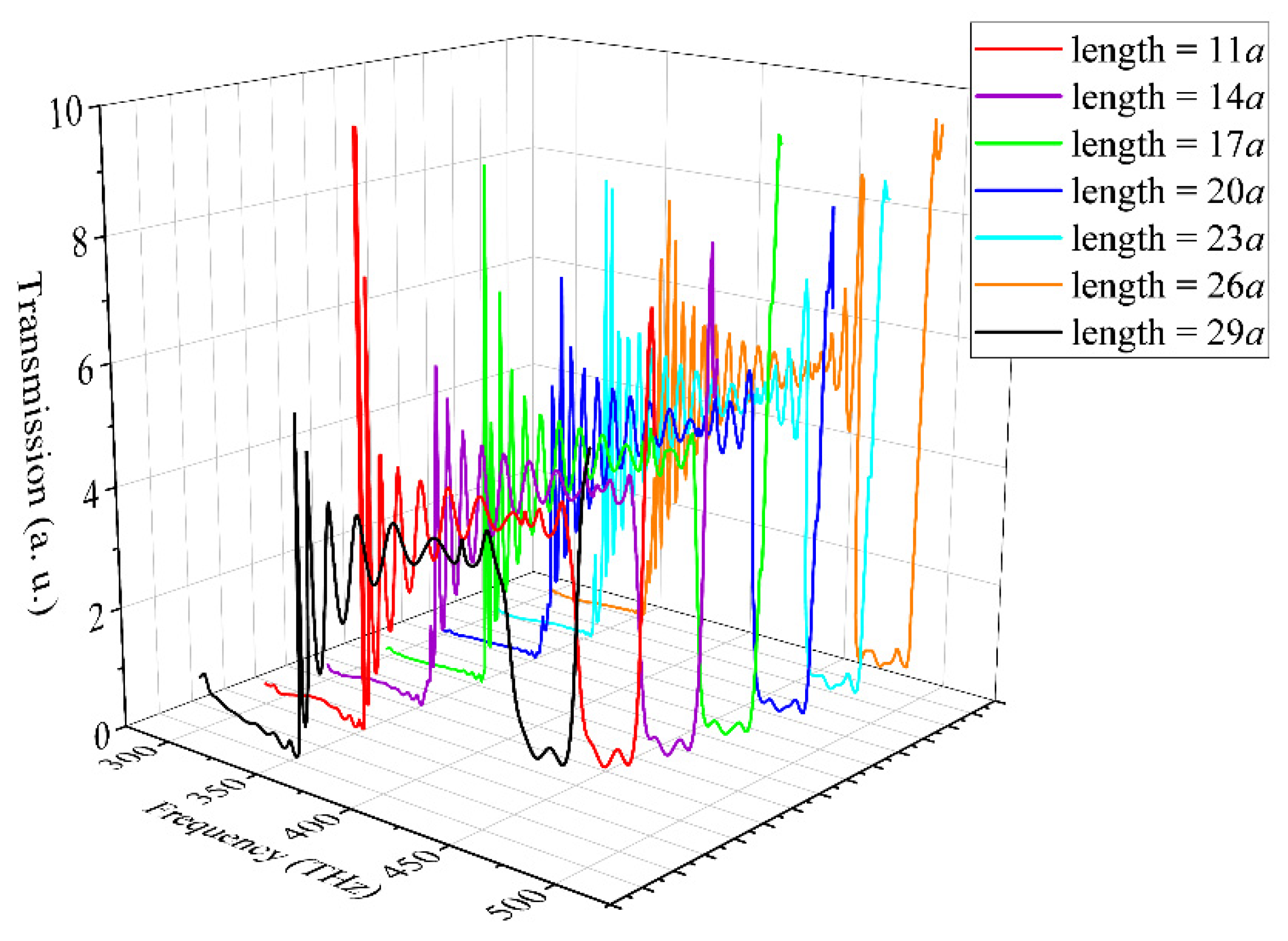

The HMM PtC waveguide sensor can be designed in various lengths to suit different applications.

Figure 8 shows the calculated transmission spectra of HMM PtC waveguides with different lengths, which exhibit similar properties. This confirms that the configuration is very flexible and can be applied to various scenarios. Additionally, the HMM PtC waveguide sensor is both compact and efficient.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z and Q.W.; methodology, Y.Z.; software, Y.Z.; validation, F.K., B.A. and Q.W.; formal analysis, Y.Z.; investigation, Y.Z., F.K., B.A. and Q.W.; resources, Y.Z.; data curation, Q.W.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z., F.K. and B.A.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z., F.K., B.A. and Q.W..; visualization, Y.Z.; supervision, Q.W.; project administration, Q.W.; funding acquisition, Y.Z. and Q.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagrams of (a) the HMM PtC waveguide, and (b) the HMM nanorod composed of alternating layers of Ag and TiO2. (c) A detailed cross-sectional view of the HMM PtC waveguide.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagrams of (a) the HMM PtC waveguide, and (b) the HMM nanorod composed of alternating layers of Ag and TiO2. (c) A detailed cross-sectional view of the HMM PtC waveguide.

Figure 2.

The longitudinal and transverse components of the effective permittivity ( and ) of the HMMs. The real and imaginary parts of the permittivity are illustrated in panels (a) and (b), respectively.

Figure 2.

The longitudinal and transverse components of the effective permittivity ( and ) of the HMMs. The real and imaginary parts of the permittivity are illustrated in panels (a) and (b), respectively.

Figure 3.

(a) Band structure of the HMM PtC waveguide when SRI = 1.33, with an arrow highlighting a dispersion curve of the guided mode located in the middle of the bandgap. (b) Electric field (Ez) profiles of guided modes for different values of kx (0, 0.1(2π/a), and 0.2(2π/a)) while ky is fixed at 0. The eigenfrequencies for these modes are 344.38 THz, 356.07 THz, and 390.22 THz, respectively.

Figure 3.

(a) Band structure of the HMM PtC waveguide when SRI = 1.33, with an arrow highlighting a dispersion curve of the guided mode located in the middle of the bandgap. (b) Electric field (Ez) profiles of guided modes for different values of kx (0, 0.1(2π/a), and 0.2(2π/a)) while ky is fixed at 0. The eigenfrequencies for these modes are 344.38 THz, 356.07 THz, and 390.22 THz, respectively.

Figure 4.

The result of a three-dimensional simulation, which illustrates the electric field (Ez) profiles of the guided mode in both the (a) x-y plane and (b) x-z planes. The simulation highlights the localization of the electric field in the y and z directions, as the electric field appears to be concentrated in these two directions. Notable, the frequency of the incident light in this simulation is 360 THz.

Figure 4.

The result of a three-dimensional simulation, which illustrates the electric field (Ez) profiles of the guided mode in both the (a) x-y plane and (b) x-z planes. The simulation highlights the localization of the electric field in the y and z directions, as the electric field appears to be concentrated in these two directions. Notable, the frequency of the incident light in this simulation is 360 THz.

Figure 5.

The electric field (Ez) profiles of waves propagating in the HMM PtC waveguide under different frequencies of incident light. Specifically, panels (a), (b), and (c) depict the Ez profiles when the incident light frequencies are 325 THz, 350 THz, 375 THz, 425 THz, 450 THz, and 500 THz, respectively.

Figure 5.

The electric field (Ez) profiles of waves propagating in the HMM PtC waveguide under different frequencies of incident light. Specifically, panels (a), (b), and (c) depict the Ez profiles when the incident light frequencies are 325 THz, 350 THz, 375 THz, 425 THz, 450 THz, and 500 THz, respectively.

Figure 6.

(a) The transmission spectrum of the HMM PtC waveguide when the SIR is 1.33. (b) The transmission of the HMM PtC waveguide when the frequency of the incident light is 350 THz.

Figure 6.

(a) The transmission spectrum of the HMM PtC waveguide when the SIR is 1.33. (b) The transmission of the HMM PtC waveguide when the frequency of the incident light is 350 THz.

Figure 7.

The transmission of the HMM PtC waveguide in different frequencies and SIRs.

Figure 7.

The transmission of the HMM PtC waveguide in different frequencies and SIRs.

Figure 8.

The transmission spectra of the HMM PtC waveguide with various lengths.

Figure 8.

The transmission spectra of the HMM PtC waveguide with various lengths.

Table 1.

Comparison of different types of sensors.

Table 1.

Comparison of different types of sensors.

| Configuration |

FOM (RIU−1) |

FWHM (nm) |

Sensitivity (nm/RIU) |

|

HMM PtC waveguide1

|

469.6 |

0.2 |

324.2 |

| HMM side-polished fiber [34] |

230.8 |

39 |

9000 |

| Ag side-polished fiber [32] |

49.8 |

87.7 |

4366 |

| Au side-polished fiber [33] |

46.1 |

103.9 |

4796 |

| PMMA/PS D-shaped fiber [30] |

39.5 |

70 |

2765 |

| Ag/MF2 SPR fiber [40] |

33.54 |

47.8 |

1603 |

| Metal-ZnO multimode fiber [41] |

15.4 |

205.3 |

3161 |

| ITO-polymer PtC fiber [42] |

9.8 |

205 |

2000 |