1. How to Use This Template

The template details the sections that can be used in a manuscript. Note that each section has a corresponding style, which can be found in the “Styles” menu of Word. Sections that are not mandatory are listed as such. The section titles given are for articles. Review papers and other article types have a more flexible structure.

Remove this paragraph and start section numbering with 1. For any questions, please contact the editorial office of the journal or support@mdpi.com.

2. Introduction

The rural–urban transition is no longer a linear process of urban expansion, but a dynamic, contested, and hybrid territory in which agricultural livelihoods are continuously reconfigured through the interplay of state regulation, market forces, and everyday agency. In this context, spatial governance has become a central instrument for reconciling land-use planning, resource efficiency, and the needs of smallholder producers. While much of the recent literature, particularly from China, celebrates integrated, top-down models of territorial governance as engines of rural revitalization [

1,

2,

3], scholars from the Global South caution that such models often overlook the heterogeneity of rural actors and the informal, adaptive logics that sustain livelihoods in transition zones [

4,

5,

6]. This gap is especially acute in Latin America, where spatial governance remains fragmented, reactive, and frequently disconnected from the realities of peri-urban agriculture [

7,

8,

9].

In Brazil, municipal open-air markets (varejões

i) have become critical interfaces of the rural–urban transition, functioning as spaces where small-scale producers engage directly with urban consumers, bypassing intermediaries and asserting alternative food economies. Yet, despite their social and economic significance, these spaces remain under-theorized in discussions of spatial governance. Existing studies often treat feirantes (smallholder farmers and resellers who sell agricultural products at open-air markets) as passive beneficiaries of urban planning or as residual figures in modernizing food systems [

10,

11], thereby missing the rich agency through which they negotiate, reinterpret, and reshape governance from below.

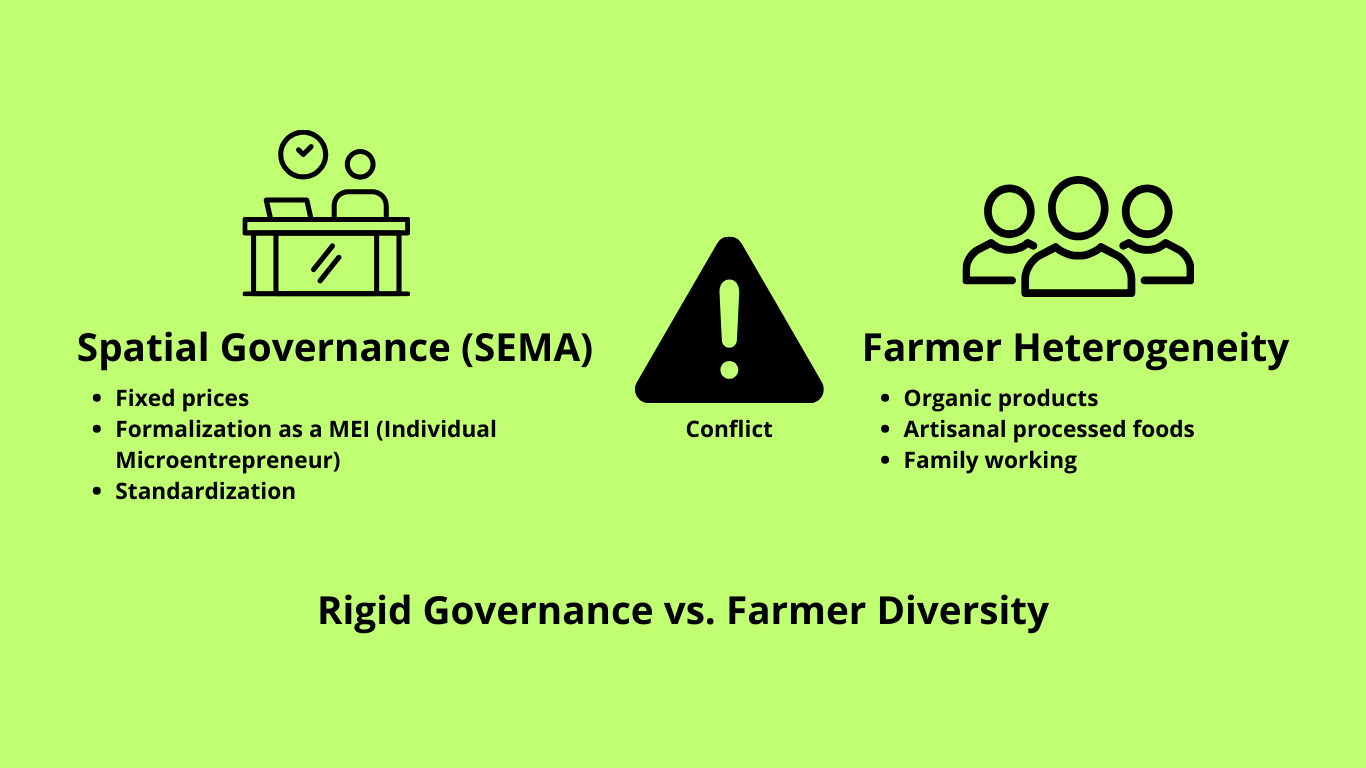

This paper addresses this gap by examining how smallholder farmers and vendors in Piracicaba (São Paulo, Brazil) interact with the spatial governance of varejões, implemented by the Municipal Secretariat of Agriculture and Food Supply (SEMAii). Drawing on 25 in-depth interviews, we analyze how SEMA’s interventions, such as fixed pricing, formalization through the MEI (Microempreendedor Individual, or Individual Microentrepreneuriii), and standardized infrastructure, clash with the heterogeneous conditions of small-scale production, particularly among organic farmers, family-based growers, and mixed vendor-producers. Crucially, we show that feirantes are not merely policy recipients; they actively diversify their livelihoods, form informal cooperatives, develop direct sales networks, and redefine agricultural work as cultural identity, thereby transforming the varejão into a site of co-governance and innovation.

Our contribution is threefold. First, we challenge the notion that spatial governance “fails” or “succeeds” in binary terms, arguing instead that it is continuously contested and co-produced through everyday practices. Second, we demonstrate that farmer heterogeneity is not a barrier to governance, but a resource, one that demands flexible, differentiated, and participatory planning approaches. Third, we offer a grounded, Brazilian perspective that resists the uncritical export of idealized models (e.g., from China) and instead highlights how survival in the rural–urban transition hinges on resilience, creativity, and collective negotiation, rather than top-down planning.

In light of this, the study seeks to answer the following research question: How do feirantes in Piracicaba reinterpret, negotiate, and reconfigure the spatial governance of varejões in the face of the heterogeneity of their agricultural livelihoods within the rural–urban transition? The general objective is to analyze how spatial governance, as implemented by the Municipal Secretariat of Agriculture and Food Supply (SEMA), interacts with the productive, commercial, and social reproduction strategies of peri-urban smallholders, especially in light of tensions arising from price standardization, bureaucratic requirements, and the absence of differentiated technical assistance.

The article is organized as follows: after this introduction, we present the theoretical framework on spatial governance, livelihoods, and rural–urban transition. Next, we describe the qualitative methodology, based on 25 semi-structured interviews with feirantes classified according to their productive profile (producers, resellers, and mixed vendors), highlighting the new coding system that foregrounds the presence of organic producers. The empirical analysis is structured around three axes: (1) productive heterogeneity as a key differentiating factor; (2) critique of standardized spatial governance, focusing on pricing, formalization, inspection, and technical assistance; and (3) the rural–urban transition as a hybrid field of co-governance, where feirantes not only survive but propose alternative futures through cooperation, innovation, and continuous negotiation. Finally, we present the conclusions, emphasizing the contribution of this Brazilian case to the international debate on spatial governance that is sensitive to agricultural diversity.

3. Spatial Governance in the Rural–Urban Transition: Between Technical Models, Productive Heterogeneity, and Local Agency

Spatial governance, in its broadest sense, refers to the institutional, political, and social arrangements that guide the production, use, occupation, and transformation of territory [

12,

13]. It is a concept that goes beyond traditional urban or rural planning, centered on maps, zoning, and technical regulations, to incorporate the dynamics of power, negotiation, conflict, and agency embedded in spatial production processes [

7].

Over the past two decades, international literature has shown that spatial governance is not monolithic. In European contexts, for example, there has been a shift from strategic planning focused on metropolitan competitiveness toward more responsive forms capable of incorporating community self-organization and citizen participation [

12,

14]. In China, spatial governance is strongly state-driven, with centralized policies seeking to integrate urban and rural development through large-scale territorial projects, although recent approaches have become more flexible and adaptive [

3,

15].

In Brazil, however, spatial governance takes on distinct contours. Historically marked by structural inequalities, weak institutional capacity, and land conflicts, territorial production has been shaped both by high-level decisions (e.g., agricultural policies, master plans) and by informal practices of occupation and resistance [

9,

16]. Recent studies highlight a duality between ex-ante planning (prospective, legal) and ex-post interventions (reactive, corrective), showing that public policies often arrive after land uses are already consolidated, as in the case of unregulated peri-urban subdivisions [

8,

17].

Moreover, spatial governance in rural and peri-urban Brazil frequently overlooks local knowledge and the survival strategies of smallholder farmers. As Sparovek et al. [

10] demonstrate, land-use policies oriented toward commercial agriculture or environmental conservation often ignore or marginalize family-based production systems, reducing territorial complexity to rigid categories (e.g., “agricultural area,” “permanent preservation area”). This technocratic logic, based on abstract maps and zoning schemes, ultimately disconnects planning from lived reality.

The rural–urban transition is not a unidirectional process of “urbanization of the rural,” but rather a hybrid and dynamic one in which agricultural practices, supply networks, and livelihoods are continuously reconfigured in response to economic, social, and environmental pressures. As Tacoli [

6] showed, interactions between rural and urban zones are fundamental to the social reproduction of populations who, even while living or working in the countryside, depend on urban markets, services, and opportunities. This structural interdependence challenges dichotomous views that oppose “rural” and “urban,” instead revealing spaces of continuous negotiation where rural livelihoods are constantly adapted.

In this context, Ellis [

5] emphasizes that smallholders in rural–urban transition rarely rely exclusively on agriculture. On the contrary, they engage in livelihood diversification, combining farming with trade, services, circular migration, and non-agricultural employment as a strategy to mitigate risks and enhance resilience. This diversification should not be interpreted as a sign of “agricultural failure,” but as a rational and creative response to market uncertainties, land pressures, and climatic volatility. However, as Wiggins, Sabates-Wheeler & Yaro [

18] observe, this transition can generate new forms of vulnerability, especially when smallholders are forced to abandon agriculture without access to viable alternatives in the formal urban sector.

The literature also stresses that agricultural livelihoods in the rural–urban transition are deeply shaped by collective strategies and social networks. Andersson [

19], analyzing Sub-Saharan African contexts, shows how farmers use community ties, informal cooperation, and exchanges of technical knowledge to strengthen their position against formalized commercial chains. These networks not only facilitate access to inputs and markets but also function as mechanisms of social protection in contexts where public policies are insufficient or absent.

Yet, survival in these hybrid territories occurs under adverse structural conditions. Bonye, Aasoglenang & Yiridomoh [

20], in a study of peri-urban Ghana, demonstrate that urban expansion often leads to loss of access to farmland, fragmentation of holdings, and unfair competition with intermediaries who do not produce but monopolize commercial spaces. A similar situation was described earlier by Zewdu & Malek [

21] in Ethiopia, where inadequate land policies marginalize smallholders, hindering their integration into emerging value chains in transition zones.

Faced with these pressures, farmers are not merely “passive victims,” but active agents who reinterpret, resist, and adapt. Choithani, van Duijne & Nijman [

22], analyzing India, show how smallholders develop “telecoupled livelihoods”, that is, they connect with distant actors (NGOs, urban consumers, certifiers) to access niche markets, technologies, and institutional support. However, this agency is differentiated: producers with greater social, educational, or political capital navigate the new rules of transition more effectively, while the most vulnerable remain on the margins. This heterogeneity is crucial for understanding survival dynamics. As Pingali et al. [

23] underline, the rural–urban transition does not affect all farmers equally.

Furthermore, the literature converges in affirming that the sustainability of agricultural livelihoods in the rural–urban transition depends less on standardized technical interventions and more on institutions’ capacity to recognize local agency, value traditional knowledge, and design policies sensitive to productive heterogeneity. As de Bruin, Dengerink & van Vliet [

24] summarize, the contemporary challenge is to build food systems that not only integrate rural and urban spheres but also value the diversity of ways of producing, marketing, and existing in these transforming territories.

Regarding spatial governance in the rural–urban transition, the literature has advanced integrated models that link territorial planning, rural development, and socio-environmental justice, particularly in contexts like China, where governance is highly centralized and oriented toward rural revitalization goals [

1,

25,

27]. In these models, the state acts as a multi-scalar coordinator, from municipal to national levels, promoting land-use reconfiguration through multifunctional zoning, incentives for sustainable production, and participatory (though hierarchical) governance structures. Here, spatial governance is presented as a strategic instrument of territorial transformation, capable of aligning economic growth, ecological protection, and social inclusion.

However, as studies from the Global South show, this idealized vision of spatial governance often clashes with the heterogeneous reality of rural livelihoods, especially in rural–urban transition zones, where agricultural production coexists with urban consumption patterns, mobility, and real estate speculation. Magigi [

4], analyzing Tanzania, warns that land-use plans that exclude or marginalize urban and peri-urban agriculture, by labeling it as “informal,” “inefficient,” or “incompatible” with urbanization, end up undermining precisely those whose subsistence depends directly on the land. When spatial governance imposes rigid categories such as “agricultural zone,” “residential zone,” or “commercial zone,” it ignores the hybrid practices of farmers who cultivate, sell, minimally process, and negotiate directly with urban consumers.

This critique is reinforced by Tan et al. [

3] and Rakodi [

26], who advocate for a livelihoods-centered approach in which spatial governance does not begin with abstract maps but with the real capacities, vulnerabilities, and strategies of local actors. From this perspective, territory is not an “empty space to be ordered,” but a field of social action where multiple actors – family farmers, intermediaries, consumers, technicians – continuously negotiate access to, use of, and value of land. The effectiveness of governance, therefore, should not be measured by the technical coherence of its plans, but by its capacity to recognize, value, and articulate the diversity of livelihood strategies.

This diversity is particularly evident in contexts of livelihood diversification, widely documented in the literature. Kassie [

27] in Ethiopia, Roden et al. [

28] in Kenya, and Baghernejad et al. [

29] in Iran show that smallholders rarely depend solely on land; they combine farming with trade, services, circular migration, and non-farm production. Yet, as Zimmerer, Carney & Vanek [

30] note, these strategies are not mere responses to poverty, but active forms of resistance, innovation, and adaptation to climate change, land pressure, and market transformation. Ignoring this agency, as many spatial governance policies do when relying on rigid categories, is to reproduce subtle forms of symbolic and material exclusion.

In Brazil, land-use governance in peri-urban areas has been marked by a strong emphasis on regularization, formalization, and sanitary control, often inspired by urban models that prioritize order, hygiene, and commercial efficiency [

8,

9]. This approach tends to homogenize diverse practices under a single regulatory framework, such as fixed pricing, mandatory formal registration (e.g., MEI), infrastructure standardization, and strict sales oversight. Although these measures aim to benefit urban consumers with affordable prices and standardized environments, they frequently disregard real production costs, family-scale operations, and the adaptive strategies of smallholders, especially those investing in differentiated practices such as organic farming or minimal processing [

10,

11].

This “one-size-fits-all” logic reveals a disconnect between prescribed governance and practiced governance. Rather than recognizing the functional diversity of peri-urban space, where production, trade, informal support networks, and value-added strategies coexist, local policies often impose rigid categories that marginalize non-standardized productive forms. This tension is exacerbated by weak coordination across government scales and limited incorporation of local knowledge into planning processes [

17,

31]. Consequently, spatial governance in Brazil does not fail due to absence, but due to an excess of technical formalism and a lack of socioeconomic sensitivity. By operating through a binary lens, rural versus urban, formal versus informal, it disregards the constitutive hybridity of transition zones, where smallholders develop creative survival strategies that blend agriculture, direct marketing, family networks, and productive innovation.

In this sense, the Brazilian case contrasts with more integrated models like China’s and critically engages with Global South literature that positions local agency as central to territorial resilience [

3,

4]. Thus, effective spatial governance in Brazil’s rural–urban transition should not be understood as an instrument of imposed order, but as a space of continuous negotiation where smallholder voices are genuinely heard and incorporated into policy design. As Ahmadzai, Tutundjian & Elouafi [

32] propose, the sustainability of agricultural livelihoods depends on flexible, context-sensitive approaches capable of articulating technical knowledge and traditional know-how. It is in the gap between governance as planning and governance as everyday practice that lies both the challenge and the opportunity to reimagine spatial governance in Brazil, not as a system of control, but as a field of co-produced territory.

4. Materials and Methods

This study adopts a qualitative approach, understood as an epistemological commitment to the social construction of reality and to the perspectives of local actors [

33]. In rural–urban transition contexts, characterized by institutional hybridity, tensions between technical regulations and everyday practices, and heterogeneous survival strategies, qualitative research proves particularly well-suited to capturing the forms of agency, adaptation, and resistance that emerge at the interface between public policy and lived experience [

34].

The primary data collection instrument was the semi-structured interview, conducted with 25 feirantes (smallholder farmers and resellers who sell agricultural products at open-air markets) operating in three central spaces of Piracicaba’s (SP) food supply network: the Central Varejão, the Organic Products Market, and the Paulista Varejão. The choice of semi-structured interviews allowed for a balance between thematic guidance, essential for investigating the relationship between spatial governance and agricultural livelihoods, and the interpretive openness characteristic of qualitative approaches, thereby fostering rich, contextualized narratives [

35].

The interview guide was developed around four thematic axes, derived from the literature on spatial governance and rural–urban transition:

(a) trajectories of market insertion (origin, motivation, occupational transitions);

(b) production and marketing strategies (channels, product differentiation, innovation);

(c) perceptions of SEMA’s role (policies, inspection, technical assistance) and forms of adaptation or resistance to rules (creativity, cooperation, critique); and

(d) visions for the future of their activity in the rural–urban transition (succession, competition, sustainability).

Interviewees were stratified according to their relationship with agricultural production, following the categories used by the Municipal Secretariat of Agriculture and Food Supply (SEMA):

(a) Producers (conventional or organic): vendors who sell exclusively products from their own farms;

(b) Resellers (conventional or organic): vendors who purchase goods from third parties (e.g., wholesale markets such as CEASAiv) for resale;

(c) Mixed vendors: those who combine self-production with complementary purchases.

This distinction is crucial, as it enables analysis of how different productive profiles, organic, conventional, family-based, or commercial, experience and respond in distinct ways to spatial governance policies, especially standardized instruments such as fixed pricing, mandatory formalization (via the Individual Microentrepreneur – MEI), and infrastructure standardization.

Table 2 below systematizes these profiles according to the proposed coding scheme.

Table 1.

Productive profiles and interviewee coding

Table 1.

Productive profiles and interviewee coding

| Category |

Subcategory |

Code |

| Producer |

Organic producer (PO) |

PO1 |

| PO2 |

| PO3 |

| Conventional producer (P) |

P4 |

| P5 |

| P6 |

| P7 |

| P8 |

| P9 |

| Reseller |

Organic reseller (RO) |

RO1 |

| RO2 |

| Conventional reseller (R) |

R3 |

| R4 |

| R5 |

| R6 |

| R7 |

| Producer/Reseller |

Mixed vendor (M) |

M1 |

| M2 |

| M3 |

| M4 |

| M5 |

| M6 |

| M7 |

| M8 |

| M9 |

| Total interviewees |

25 |

Table 2.

Empirical categories and subcategories organized by analytical axes

Table 2.

Empirical categories and subcategories organized by analytical axes

| Analytical Axis |

Empirical Category |

Subcategory (Interview Guide) |

| Productive heterogeneity |

Productive profiles and strategies |

Producer, reseller, producer/reseller

Organic vs. conventional

Diversification: minimally processed products, organic production |

| Critique of standardized spatial governance |

Perceptions of SEMA and its policies |

Rigid price controls and disconnect from real production costs

MEI formalization as bureaucratic requirement

Decontextualized inspection practices

Insufficient or generic technical assistance

Unfair competition between producers and resellers |

| Rural–urban transition as a hybrid field |

Structural challenges and future visions |

Urban pressure, supermarket competition, loss of young labor

Potential for co-governance and responsive policies

Critical perspectives on the future of the market |

All interviews were fully transcribed and subjected to a theory-driven qualitative content analysis [

34]. The analysis followed principles of discourse analysis [

36,

37], understood not as the decoding of fixed meanings, but as an exploration of how subjects construct meaning regarding spatial governance, their rights, their strategies, and their productive identities. From this process, three integrated analytical axes emerged, which structure the empirical discussion of the article:

(a) Productive heterogeneity: profiles, strategies, and tensions in the rural–urban transition (articulating trajectories, production/marketing strategies, and future visions);

(b) Critique of standardized spatial governance: technical rigidity versus lived complexity (articulating perceptions of SEMA, model limitations, and recognition failures); and

(c) The rural–urban transition as a hybrid field: structural challenges and possibilities for co-governance (synthesizing the previous axes and projecting toward the future), as shown in the table below.

5. Results and Discussion

In this section, the research findings are analyzed and discussed through three thematic axes that emerged from interviews with vendors (feirantes) at Piracicaba’s municipal open-air markets (varejões). The discussion is organized into three interrelated subsections: 4.1 Productive heterogeneity, which explores the diverse trajectories, strategies, and identities of smallholder producers, from agroecological farmers to resellers and intermediaries, highlighting the socioeconomic and cultural diversity that characterizes the market; 4.2 Critique of standardized spatial governance, which examines how policies implemented by the Municipal Secretariat of Agriculture and Food Supply (SEMA), despite good intentions, often impose uniformizing logics that overlook local specificities, generating tensions between formalization and everyday practice; and 4.3 The rural–urban transition as a hybrid field, which emphasizes how the varejão functions as a liminal space where rural practices, urban consumption dynamics, and everyday adaptation strategies intertwine, configuring a territory of continuous negotiation between tradition, innovation, and survival. Together, these axes reveal the complexity of spatial governance in rural–urban zones and the agency of vendors in continuously reconfiguring their livelihoods and work practices.

5.1. Productive Heterogeneity

The productive heterogeneity among Piracicaba’s feirantes (smallholder farmers and vendors who sell agricultural products at open-air markets) emerges as a fundamental axis for understanding the dynamics of the rural–urban transition. Far from constituting a homogeneous group, interviewees reveal striking diversity in their trajectories, production strategies, and forms of labor organization, a plurality that directly challenges standardized models of spatial governance. This section analyzes this heterogeneity through three interrelated dimensions: 4.1.1 the differentiation among productive profiles (producers, resellers, and mixed vendors) and variations in production strategies (conventional vs. organic, family-based vs. commercial); 4.1.2 multiple forms of income diversification that extend beyond the market, including minimal processing and other complementary activities; and 4.1.3 labor relations that combine family labor, informal cooperation, occasional hiring, and resistance to formal wage employment.

5.1.1. Differentiation and Variation in Production Strategies

The twenty-five interviewed vendors in Piracicaba do not constitute a homogeneous group, but rather a mosaic of productive profiles whose strategies, motivations, and relationships with spatial governance vary significantly. This heterogeneity manifests in two central dimensions: (i) position in the marketing chain (producer, reseller, or mixed vendor); and (ii) the adopted production strategy (organic vs. conventional; family-based vs. commercial).

- (i)

Position in the chain: The distinction between producers, resellers, and mixed vendors is not merely technical, but carries symbolic, economic, and political implications. Producers (e.g., PO1, P3, P6) proudly state: “Everything is from my own production, I don’t buy anything” (PO1). For them, professional identity is anchored in productive autonomy and direct connection to the land. Resellers (e.g., R1, R2, RO1), in contrast, openly assume an intermediary role: “No, I only distribute, I buy from producers and resell” (R2). Despite this, many develop customer loyalty strategies that go beyond simple resale, such as product tasting, customized cuts, or fixed delivery routes. More complex is the figure of the mixed vendor (e.g., M3, M5, M9), who combines self-production with supplementary purchases. This profile reflects both structural constraints (land scarcity, labor shortages, or limited capital) and strategic rationalities: “It’s much more worthwhile to source from outside, the labor you save alone makes it worth it” (M3). The existence of this hybrid group directly challenges SEMA’s binary logic, which treats “producer” and “reseller” as mutually exclusive categories, thereby ignoring the fluid reality of the rural–urban transition.

- (ii)

(2)Production strategy: The second dimension of heterogeneity concerns product type and underlying production logic. Here, the clearest division is between organic and conventional systems. Organic vendors (PO1, PO2, PO3, RO1, RO2) not only adopt agroecological practices but also construct a professional identity grounded in ethical values: respect for soil, biodiversity, consumers, and the planet. Interviewee RO2 states emphatically: “Whoever plants respects the soil, water, the place they step on, the planet Earth, and the food they bring to your home.” This ethics translates into market differentiation: organic vendors charge higher prices, build trust-based networks, and reject the logic of uniform pricing. However, they face significant barriers, including a lack of specialized technical assistance and unfair competition from resellers who falsely present themselves as certified organic producers. Conventional vendors, who constitute the majority of interviewees, operate according to logics of volume and efficiency. Some, like interviewee P4, argue that “they should compare [quality]... prices should be tiered like rice packages”, criticizing SEMA’s standardization. Others, like R3, innovate through minimal processing, adapting without breaking from the system. Finally, there is a clear distinction between family farming, centered on the household unit, family labor, and social reproduction, and commercial-scale operations focused on profit, hired labor, and territorial expansion (e.g., RO1, who runs a shop in Limeira and delivers to Campinas).

This structural difference influences not only survival strategies but also future visions and willingness to cooperate. This productive heterogeneity is central to the article’s argument: effective spatial governance in the rural–urban transition cannot treat all vendors as equals. Policies that ignore these differences, such as rigid price controls, inflexible inspection, or generic technical assistance, end up rendering innovative strategies invisible and marginalizing the most vulnerable.

5.1.2. Income Diversification

In Piracicaba’s rural–urban transition, vendors’ economic survival rarely depends exclusively on direct sales at municipal markets (varejões). Faced with rigid price controls, climatic volatility, and competitive pressures, income diversification emerges as a central resilience strategy, taking distinct forms depending on the vendor’s productive profile. We identify three main axes: parallel activities, minimal processing, and alternative marketing channels, illustrated with interviewees’ accounts.

- (i)

Parallel activities (between necessity and complementarity): Many vendors maintain additional income sources, whether by choice, necessity, or as a risk-mitigation strategy. Interviewee M3, a vegetable producer, is also an industrial mechanical technician, acknowledging this duality: “I’m an industrial mechanical technician. That’s it, I’m a producer.” Interviewee R2, a reseller, supplements income through informal activities: “I organize raffles, whatever comes up... Right now, I’m doing raffles in my spare time, so I sell raffle tickets.” Interviewee P2, meanwhile, combines agricultural income with rental income: “Yes... and a little rental income too.” These strategies reveal that even in seemingly “rural” activities, the rural–urban transition imposes economic hybridity: work is not confined to agricultural production but intertwines with formal or informal urban economies.

- (ii)

Minimal processing (adding value amid fixed pricing): In response to SEMA’s imposition of fixed prices, which disregard real production costs and quality differentiation, some vendors add value through minimal product transformation. Interviewee M3 describes an ambitious collective project: “To add more value to the final product, we’re setting up an industrial kitchen to produce minimally processed goods with support from CATI (Integrated Technical Assistance Coordination Officev)... We’ll build a shed, install processing machines, and buy a truck... We’re thinking of forming a cooperative to access larger markets... One person alone can’t do it, but together we can.” Interviewee R2 adopts a more immediate approach: “We already peel and pack ready-to-go portions... We cut pumpkins and sell them by the kilo in small bags... We chop cabbage, clean cauliflower, it’s all prepped and ready.” These practices are not mere commercial adaptations but forms of resistance to standardization: by transforming their products, vendors claim a space of differentiation that partially escapes the logic of uniform pricing.

- (iii)

Alternative channels: The most sophisticated form of diversification appears among organic vendors, whose value logic-ethical, ecological, and symbolic, is incompatible with SEMA’s price controls. Interviewee PO2 has built a loyal consumer network beyond the market: “Look, I don’t just do the varejão; I also have a direct consumer network... Between the market and this network, we make around three thousand reais a month.” Interviewee RO2 goes further, developing a home-delivery system combined with food education: “My project is to deliver a basket to your home... We take orders online, ‘I want one kilo of bananas’, and I bring the best products to your door... I want to turn this stall into a kind of gourmet shop: refrigerator, organic wheat pasta, free-range eggs, stuffed eggplant...” Interviewee RO1 operates across multiple territorial scales: “Yes... I have a small shop in Limeira and also deliver to households... I serve Limeira, Campinas, and here.” These alternative channels not only increase profit margins but also reconfigure producer–consumer relationships, introducing elements of trust, transparency, and proximity that the standardized varejão cannot offer.

Income diversification among Piracicaba’s vendors is not a sign of agricultural failure but a strategic and creative response to homogenizing spatial governance. It manifests differently by profile: conventional producers (P) tend to supplement income with external sources (rentals, pensions); resellers (R) focus on operational efficiency and rapid processing; mixed vendors (M) articulate cooperation and collective infrastructure; and organic vendors (PO/RO) build alternative market niches, implicitly rejecting the logic of fixed pricing. These strategies demonstrate that local agency operates in the interstices of formal governance, filling gaps left by policies that, in seeking to “modernize” the market, end up disregarding productive heterogeneity and the real dynamics of the rural–urban transition.

This income diversification does not emerge as mere economic adaptation but as a situated form of resistance that critically engages with literature on spatial governance and livelihoods in the Global South. As Ellis [

5] and Wiggins, Sabates-Wheeler & Yaro [

18] observe in Sub-Saharan Africa, diversification in Piracicaba, through minimal processing (M3), loyal consumer networks (RO2), or home-delivery baskets (PO2), reflects a productive rationality that escapes the “all-or-nothing” logic. This local agency resonates with findings by Peng et al. [

38] and Choithani, van Duijne & Nijman [

22], who highlight how smallholders in transitional contexts develop “telecoupled” productive arrangements to circumvent rigid policies.

In Brazil, this dynamic is exacerbated by the weak incorporation of local knowledge into public policies, as noted by Sparovek et al. [

10] and Jesus Silva et al. [

11], whose studies show that land-use policies often marginalize family-based production systems in the name of technical efficiency. In Piracicaba, this disconnect is acute: while SEMA enforces uniform pricing, organic vendors (PO1, PO2, RO2) and innovative producers (M3, M8) develop forms of symbolic and economic valorization that challenge standardization. This everyday creativity confirms the critique by Magigi [

4] and Rakodi [

26]: effective spatial governance is not one that imposes order from above, but one that recognizes livelihood heterogeneity and learns from local survival strategies. In this sense, Piracicaba’s vendors do not merely “diversify income”; they reinvent the very notion of agriculture in the rural–urban transition, transforming the market into a space of political negotiation, productive identity, and socio-economic resilience.

5.1.3. Labor Relations

Work at the market is rarely a solitary activity. On the contrary, it is structured around networks of reciprocity that combine family ties, informal partnerships, community support, and, to a lesser extent, wage labor. These productive arrangements reveal a moral economy that starkly contrasts with the bureaucratic logic of SEMA’s spatial governance, which tends to treat vendors as isolated individuals, formalized as MEIs, subject to standardized rules, without considering the collective dynamics that sustain production and marketing. Three main forms of labor relations emerge from the analysis of interviews with the 25 vendors: family labor, hired employees, informal cooperation, and resistance to formal hiring.

- (i)

Family labor: The family is the central productive unit for most interviewees, especially among producers (P) and mixed vendors (M). Interviewee P3 describes work as a generational effort: “In the field, it’s me, my son, and my father... Here at the market, it’s also me and my son; my father stays home, and my daughter-in-law and granddaughter also come to the market.” Interviewee M3 articulates a task division based on skills: “My son handles deliveries with the truck... Here it’s me, my son-in-law, and my two nieces.” This logic also appears in P2’s account: “Right now, it’s just me and my husband... Our children work elsewhere, they went to college and moved away.” In these cases, children’s departure or lack of succession not only affects income but threatens the very reproduction of the family-based production model, a structural risk that SEMA’s governance fails to address.

- (ii)

Hired employees: Although many avoid hiring, some interviewees employ workers, especially as their operations scale up. Interviewee R4, for example, has a fixed team: “We’re five people now... a trusted team... it’s a good group.” Interviewee R5 employs seven people: “Seven... always the same team... one worker is sick today, but she’ll be back next week.” Yet even in these cases, there is an effort to humanize labor relations beyond contractual terms. Interviewee M4 explains: “The more they sell, the more I pay... Because the better they treat the customer, the more customers return... If you treat the customer well, they come back.” This practice reveals a care-based ethics that challenges the technical neutrality of governance: the vendor is not merely a “reseller,” but a manager of human relationships.

- (iii)

Informal cooperation: The most compelling form of labor organization appears in informal cooperation, especially among organic and innovative producers. Interviewee M3, planning an industrial kitchen, states: “We’re thinking of forming a cooperative to access larger markets... One person alone can’t do it, but together we can.” Interviewee RO2 expands this logic: “Among those working with organic products, it’s really great, one helps the other, both in logistics and production... We exchange seeds, do technical visits... There are 17 producers working together, and it’s really nice.” This network of productive solidarity sharply contrasts with the implicit competition in SEMA’s model, which treats all vendors as rivals under the same rules. For these vendors, cooperation is more effective than competition, a vision that official spatial governance ignores.

- (iv)

Resistance to hiring: Interestingly, some interviewees explicitly refuse to hire employees, even when financially able. Interviewee RO1 states: “No, thank God, no... [Have you never needed to?] No, I don’t want to ((laughs)).” Interviewee PO2 is equally firm: “No, we don’t have any.” This refusal is not due to lack of resources, but stems from a desire to maintain family control and distrust of bureaucracy. The MEI requirement, rather than encouraging formal wage employment, is often seen as a threat to the autonomy the market provides.

Labor relations in Piracicaba’s varejões reveal a hybrid economy where affective ties, productive solidarity, and relational management largely replace formal organizational structures. This reality challenges standardized spatial governance, which: (a) assumes the vendor is an isolated individual (MEI); (b) ignores the family and community networks that sustain production; and (c) disregards informal cooperation as a resilience strategy.

The Piracicaba case shows that governance effectiveness does not depend on uniform rules, but on the capacity to recognize and support existing collective forms of labor organization. Policies aiming to strengthen agricultural livelihoods in the rural–urban transition must therefore encourage cooperation, value family labor, and support collective structures, such as cooperatives and knowledge networks, not merely demand individual formalization.

These labor relations, deeply rooted in family, informal cooperation, and resistance to standardized wage employment, find strong resonance in the literature on spatial governance and livelihoods in the Global South. Ellis [

5] and Wiggins, Sabates-Wheeler & Yaro [

18] already emphasized that in rural–urban transition zones, family farming crucially depends on unpaid household labor, which reduces costs but also limits expansion and generational succession.

Moreover, authors like Drescher, Holmer & Iaquinta [

39] and Zimmerer, Carney & Vanek [

30] demonstrate that urban gardens, homegardens, and exchange networks function as collective strategies for food security and resilience, not merely as economic activities. This logic is visible in the cooperation among organic vendors (PO1, RO2), who exchange seeds, knowledge, and logistics, forming a network of productive solidarity that contrasts with the individualization imposed by SEMA’s governance. This contrast deepens when considering the critiques by Magigi [

4] and Rakodi [

26]: land-use policies that ignore local labor arrangements tend to marginalize the most vulnerable, even when well-intentioned.

5.2. Critique of Standardized Spatial Governance

The spatial governance implemented by the Municipal Secretariat of Agriculture and Food Supply (SEMA) in Piracicaba’s municipal open-air markets (varejões), although motivated by legitimate goals of organization, hygiene, and food access, reveals a significant misalignment with the productive and social realities of vendors (feirantes – smallholder farmers and reseller who sell agricultural products at open-air markets). This subsection analyzes this disconnect through five interrelated dimensions: 4.2.1 rigid price controls based on external quotations that ignore real production costs and quality differentiation; 4.2.2 the requirement of formalization via the Individual Microentrepreneur (MEI), perceived less as a tool of empowerment and more as a bureaucratic barrier disconnected from effective support; 4.2.3 decontextualized inspection practices marked by a lack of dialogue, focus on formal infractions, and neglect of concrete working and marketing conditions; 4.2.4 insufficient or generic technical assistance that fails to recognize the specific needs of different productive profiles, especially organic farmers; and 4.2.5 unfair competition resulting from ineffective oversight of product origin, allowing resellers to present themselves as rural producers and gain undue advantages.

5.2.1. Rigid Price Controls and Disconnect from Real Costs

The price control policy implemented by SEMA is undoubtedly the most visible, and most criticized, spatial governance mechanism among Piracicaba’s vendors. Although its stated objective is to ensure affordable prices for consumers and fair competition, in practice the system reveals a profound disconnect from productive realities, particularly for smallholders and differentiated producers. Interviewees describe the price-setting process as distant, bureaucratic, and inflexible.

SEMA bases its pricing on wholesale market (CEASA) quotations from Campinas, a neighboring municipality, often outdated or referencing lower-quality produce. As interviewee M5 reports: “They set a price based on CEASA, but sometimes CEASA doesn’t even have good vegetables, and they don’t adjust the price properly.” This standardization ignores variations in quality, production costs, and logistical effort. Interviewee R5 illustrates the absurdity of this logic with precision: “This week I had a problem with passion fruit... I paid 75 reais for a box... then a fiscal officer comes and says I have to sell it at 6.99 per kilo. I can’t sell it at 6.99 if I paid 75!” This statement encapsulates the structural contradiction of the model: prices are fixed without regard for real acquisition costs, directly causing losses for vendors. nterviewee P1 proposes a simple yet revealing solution: “It should be like rice packages, you have 5 kg, 7 kg, 9 kg, 10 kg, 12 kg, 15 kg... you choose which one you want. Here, no, they set just one price.” This analogy with the rice market, where quality differentiation justifies price variation, exposes the rigidity of SEMA’s model, which treats all products as equivalent regardless of freshness, variety, origin, or production practices. The critique becomes even sharper among organic producers, whose costs are significantly higher. PO1, a producer with over two decades of experience, states with frustration: “Organic is more expensive... and there are reasons for it to be more expensive... but SEMA doesn’t recognize that.” PO2 reinforces this: his strategy of home-delivery baskets and an organic “gourmet shop” is only viable outside the varejão, precisely because there “the fiscal officer stops you and won’t let you charge more” (E4). Thus, rather than protecting consumers, price controls discourage quality production and penalize those who invest in differentiation.

Some vendors attempt to negotiate adjustments, especially during climatic crises. R6 recounts: “The rain ruined the produce... we already argued with them that vegetable prices need to go up a bit... But when you talk to them, what happens? Nothing... Today they raised prices a little so we can recover some of our losses.” This passivity, reacting only when losses are widespread, rather than through responsive policy design, reveals the reactive, non-adaptive nature of spatial governance.

Finally, there is tacit recognition that the system benefits resellers (who buy in bulk) more than family farmers. R1 observes ironically: “It’s just people buying from CEASA and reselling at the market... and many think they’re local producers... but they’re not.” This unfair competition is amplified by uniform pricing: resellers, with higher margins, can absorb the fixed price, while producers, facing high real costs, operate at the edge of loss.

Price controls in Piracicaba exemplify a paradigmatic case of technically sound but socially blind spatial governance. In seeking to standardize territory, it ignores the living complexity of productive strategies, generating perverse effects: devaluation of quality, disincentive to innovation, and marginalization of the most vulnerable. Though well-intentioned, this policy operates under a “one-size-fits-all” logic fundamentally incompatible with the heterogeneity of the rural–urban transition.

As Magigi [

4] observed in Tanzania, spatial plans that impose standardized rules without considering real costs, product quality, or farmers’ livelihood strategies end up marginalizing precisely those they should protect. In Piracicaba, SEMA sets prices based on CEASA quotations, often outdated or referencing second-tier produce, as vendors denounce: “I bought passion fruit for 75 reais per box, and the fiscal officer wants me to sell it at 6.99 per kilo” (R5). This policy-practice disconnect echoes findings by Sparovek et al. [

10] and Jesus Silva et al. [

11] in Brazil, whose studies show that land-use policies often disregard the heterogeneity of family-based production systems, imposing commercial logics that favor intermediaries and penalize direct producers.

This critique deepens when we contrast the Brazilian case with the celebrated Chinese models described by Ge et al. [

1] and Sun et al. [

2], where spatial governance acts as a flexible articulator between state scales and local realities. In Piracicaba, by contrast, governance operates reactively and inflexibly, unable to adapt prices to climatic volatility, quality differentiation (especially in organic production), or the cost structures of smallholders. This rigidity sharply contrasts with the proposals of Rakodi [

26] and de Bruin, Dengerink & van Vliet [

24], who advocate for a livelihoods-centered approach in which governance starts from actors’ real capacities and vulnerabilities, not abstract averages.

5.2.2. MEI Formalization as Bureaucratic Requirement, Not Empowerment

The requirement to register as an Individual Microentrepreneur (MEI) to operate in Piracicaba’s varejões is a cornerstone of SEMA’s spatial governance. Although officially presented as a measure for productive inclusion, labor formalization, and access to social security benefits, the majority of vendors perceive the MEI in practice as a bureaucratic obligation, disconnected from any real support for improving working conditions or enhancing producer value. Many interviewees acknowledge having registered as MEIs but do not fully understand its purpose. R6 summarizes this ambiguity clearly: “Yes, I had to register as MEI because... to get the card machine, my credit card, and you need MEI for that, and that’s it.” P9 shows confusion: “Individual Microentrepreneur? No... Do you have it? I don’t, I guess they might, but I think I don’t.”

This lack of clarity reflects a gap between policy and practice: MEI registration is imposed as a condition for market access but is not accompanied by meaningful training on rights, obligations, or opportunities that formalization could offer. When asked about advantages, responses are pragmatic and limited. RO2 mentions credibility and the ability to issue invoices: “I can offer that to customers who ask for a receipt, which gives more credibility... Leaving informality... becoming a company.” R4 highlights access to equipment: “Without MEI you can’t get a card machine... that’s something I liked.” M3 sees utility only in employee registration: “I pay my contribution there... and I can also hire a registered employee.”

However, this positive view is the exception. Most vendors perceive no concrete benefits. M9 states ironically: “Yes, I have it, but right now it’s not helping much... I pay my little contribution there ((laughs)).” R5 goes further, questioning the model’s logic: “The only difference is that I’m just paying into INSS... If I need to take leave or retire, that’s why I opened it...” This suggests that, in a context of eroded social protections, the MEI is seen not as a safety net but as an additional cost, especially when revenue is low and profitability uncertain.

Moreover, there are explicit criticisms of the MEI’s political instrumentalization. R1 reports: “We took the course, the training, but we don’t have [benefits]... We only have the rural producer status.” This account shows that even with orientation, some producers still struggle to achieve meaningful formalization. This disconnect between offered training and on-the-ground reality reinforces the sense that MEI registration is more an administrative requirement than a strategy for productive strengthening.\

The MEI requirement in Piracicaba’s varejões functions as a spatial governance mechanism that prioritizes the appearance of formality over the real sustainability of livelihoods. Rather than empowering vendors, especially small family farmers, the MEI is experienced as a bureaucratic entry barrier, devoid of technical, financial, or pedagogical support. This confirms the critique by Rocco, Royer & Mariz Gonçalves [

9] and Pioletti & de Oliveira Royer [

8]: urban regularization policies in Brazil often substitute inclusion with bureaucratization, creating islands of “order” that mask the absence of structural rural development policies.

5.2.3. Decontextualized Inspection

Inspection practices by the Municipal Secretariat of Agriculture and Food Supply (SEMA) in Piracicaba’s varejões are perceived ambivalently by vendors. On one hand, there is recognition of the need for standardization, hygiene, and organization; on the other, there is recurrent criticism of the lack of sensitivity to productive realities, excessive rigidity in rules, and the absence of genuine dialogue between inspectors and vendors. Many interviewees acknowledge the importance of inspection, especially to maintain the market’s reputation and prevent abuses. R1 states: “Inspection is necessary… to keep things organized, everything neat and within standards, I think it’s needed.” R4 values oversight: “If you leave resellers on their own, they’ll abuse the system.” RO2 also recognizes its role: “To prevent slacking… people tend to relax, and we always need to improve.” It is worth noting that these are resellers who often source products from CEASA (the regional wholesale market); because SEMA’s price controls are based on CEASA quotations, resellers benefit from this alignment, enjoying greater regulatory privilege than direct producers.

However, this acceptance coexists with reports of authoritarianism, lack of empathy, and disconnection from vendors’ daily realities. R6 describes constant conflict with inspectors: “We argue a lot with the inspectors here because they only look at our flaws, not theirs… they’re very harsh with us.” M5 portrays inspection as punitive rather than supportive: “Before, we could call out to customers… now we can’t, if I shout, I get a warning and might even be banned from the market.” This rigidity becomes especially problematic when inspectors disregard vendors’ material conditions. M9 highlights the insecurity of his stall location: “It’s in a different spot every time… if it rains, how am I supposed to work? … We’re producers, they should give us priority, at least place us somewhere that doesn’t flood.”

The most pointed critique, however, concerns unequal treatment between producers and resellers. R5 denounces: “There are resellers who claim to be rural producers… and as ‘producers,’ they can sell whatever they want… I don’t think that’s right.” This misrepresentation of producer identity, enabled by ineffective oversight of product origin, fuels unfair competition, exacerbated by the governance system itself. As M6 states: “The only thing we have today is a lot of unfair competition.” Additionally, there are reports of humiliation and disrespect. P3 mentions an official document questioning his “education”: “They say I lack education… it’s written in a document signed by the director and the secretary.” This episode reveals an inspection regime that morally judges vendors rather than supporting them, focusing on disciplinary sanctions instead of capacity-building or listening. Interestingly, even among inspectors, postures vary. Some, like Guastalli (a municipal inspector), are praised for their humanity and honesty (E19), while others are called “vultures” (E18) or “stupid” (E7). This internal heterogeneity within SEMA shows that the problem lies not merely with individuals, but with the absence of a clear governance policy grounded in dialogue and contextual understanding.

Inspection in Piracicaba operates through a bureaucratic and punitive logic that prioritizes formal compliance over understanding real production and marketing conditions. Although aspects like hygiene, visual standardization, and pricing are valued by vendors themselves, the lack of empathy, excessive rigidity, and tolerance of identity fraud undermine the system’s legitimacy. This confirms the critique by Rocco, Royer & Mariz Gonçalves [

9] and Pioletti & de Oliveira Royer [

8]: spatial governance policies in Brazil often replace cooperation with inspection, generating apparent order but real exclusion. Truly effective governance would require inspectors who act first and foremost as mediators between the state and smallholders, not enforcers of an abstract order.

5.2.4. Insufficient or Generic Technical Assistance

Technical assistance offered by SEMA is perceived ambivalently by vendors. On one hand, there is acknowledgment of existing courses, workshops, and partnerships with institutions like ESALQvi and SEBRAEvii; on the other, there is recurrent criticism of generic content, lack of practical applicability, and, most significantly, the absence of specialized support for organic producers, whose needs differ radically from those of conventional farmers.

Many vendors report attending events out of obligation, not interest. RO1 states ironically: “I’m required to attend ((laughs)).” R6 admits: “Some [courses] are mandatory, but I go just because I have to… Honestly, no one has helped me so far, in fact, it’s only made things harder.” This sense of practical uselessness is echoed by others. P5 recounts: “In the courses I’ve attended, what they teach, we already know much more than that. It’s all theory, and we know the practice ((laughs)).” This disconnect between technical theory and field reality deepens when it comes to organic farming. RO2, despite his engagement with organic production, acknowledges: “Sometimes I attend, but there’s no specific course for organic… the courses are tailored for conventional producers… to say there’s anything for organic producers is zero.” PO1, one of the few organic producers with over two decades of experience, is even more critical: “I don’t see the technical assistance SEMA provides… especially for him [pointing to another organic producer].” This lack of specialized support has direct consequences for the viability of organic production. M6 explains why his “organic” bananas lack certification: “For over ten years, no pesticides have been used on that land… we just don’t have the certificate, but the product is differentiated… What makes organic certification difficult? The entire farm must be free of agricultural inputs, and certifiers must visit, it’s quite complicated… Plus, the organic market is still weak, too weak to justify investing in certifying the whole farm.” Thus, producers face a double barrier: bureaucratic and technical (certification requirements) and institutional (lack of technical guidance through the process).

Moreover, there is a clear perception that SEMA prioritizes political goals over real needs. RO1 criticizes: “It’s all politics, purely political… maybe it’s good for the public, but I don’t see any benefit for us.” This view is reinforced by P3, who recounts difficulties with sanitary regulation when producing cheese: “Sanitary defense was pressuring me to stop making cheese… they even seized my cheese once… but I hired a lawyer, and it worked out.” This episode reveals that, in the absence of integrated technical assistance (linking production, marketing, and sanitary compliance), vendors must rely on private networks (lawyers, personal contacts) to survive, deepening inequalities between those with and without social capital. Finally, even among those who value the courses, gaps are acknowledged. M6, speaking of his agronomist, notes: “I once prepared a technical report with an agronomist who encouraged me… I was producing a lot.” But this support came from outside SEMA’s structure, through personal initiative.

Technical assistance in Piracicaba operates through a generic, decontextualized logic that fails to recognize the ontological differences between conventional and organic agriculture. While conventional producers receive advice aligned with a productivist paradigm (input use, pest control), organic producers, who operate through agroecosystem logics, nutrient cycling, and participatory certification, are left on the margins. This confirms the critique by Ahmadzai, Tutundjian & Elouafi [

32] and Sparovek et al. [

10]: agricultural policies that do not differentiate producer profiles end up invisibilizing and discouraging sustainable practices. In Piracicaba, the absence of technical support for organic producers is not a technical oversight, but a structural failure of spatial governance that prioritizes standardization over productive diversity.

5.2.5. Unfair Competition

One of the most recurrent tensions in vendors’ accounts concerns unfair competition generated by resellers who present themselves as “rural producers” to SEMA, thereby gaining regulatory privileges not afforded to other vendors. This widely denounced practice undermines the legitimacy of the spatial governance system itself, which, by establishing rigid categories (“producer” vs. “reseller”), inadvertently incentivizes identity fraud as a survival or profit strategy. R3 clearly describes this distortion: “There are resellers who claim to be rural producers… and as ‘producers,’ they can sell whatever they want… I can’t, even bananas and oranges, which they buy and label as their own production… I don’t think that’s right.” What R3 highlights is that SEMA grants “rural producers” exclusive rights to sell all products grown on their farms, a protective measure intended to support local agriculture. However, this well-meaning policy creates opportunities for opportunism: resellers falsely claim producer status to expand their product portfolios and compete more effectively with the full diversity offered at the varejão.

Meanwhile, “true” resellers like R3 are restricted to a limited list of items, harming their competitiveness. This critique is echoed by RO1: “It’s just people buying from CEASA and reselling at the market… and many think they’re local producers… but they’re not.” This misrepresentation not only distorts competition but also devalues the work of family farmers who invest time, land, and effort in direct production. P1 laments: “The real producer is disappearing.” Furthermore, inspection is selective. While resellers face strict controls on pricing, stall organization, and product volume, some “producers”, in reality disguised resellers, operate with greater freedom under the protection of their official category. This asymmetry breeds resentment and distrust, eroding solidarity among vendors.

Notably, not all resellers act this way. RO2, for example, openly acknowledges his role: “No, I’m a trader of organic products, but the actual producers are my partners…” This ethical transparency contrasts sharply with the strategic opacity of those who appropriate the “producer” identity for advantage. This reveals that unfair competition is not intrinsic to street vending, but rather a negative effect of poorly calibrated spatial governance that creates binary categories without effective verification mechanisms.

Unfair competition in Piracicaba is thus a symptom of a structural governance failure: by establishing rigid categories without real differentiation or oversight mechanisms, SEMA inadvertently encourages fraud and penalizes honest actors. This dynamic confirms Magigi’s [

4] critique: land-use policies that fail to incorporate agricultural livelihoods realistically tend to exclude precisely those most dependent on the system, namely, rural producers themselves. Identity fraud is not a moral failing but a rational strategy within a system that values the appearance of productivity over actual production. This contradiction also challenges the celebrated Chinese models described by Ge et al. [

1] and Sun et al. [

2], where spatial governance effectively articulates state and producer interests. In Piracicaba, by contrast, governance operates through selective inspection, regulatory asymmetry, and lack of dialogue, reproducing subtle forms of symbolic and material exclusion, as documented by Rocco, Royer & Mariz Gonçalves [

9] and Pioletti & de Oliveira Royer [

8] in the Brazilian context.

Ultimately, the solution lies not in more control, but in greater transparency and qualitative differentiation. As Ahmadzai, Tutundjian & Elouafi [

32] and Rakodi [

26] propose, effective spatial governance must start from the reality of livelihoods, valuing those who truly produce, encouraging trust-based networks, and discouraging simulation not through punishment, but by creating differentiated value for direct production. Thus, the Piracicaba case demonstrates that spatial governance does not fail due to absence, but due to poor design: by oversimplifying territorial complexity, it generates injustices that undermine the very system it seeks to regulate.

5.3. The Rural–Urban Transition as a Hybrid Field

The rural–urban transition in Piracicaba does not constitute a simple overlay of two worlds, but rather a dynamic and hybrid field where agricultural practices, urban consumption logics, and survival strategies intertwine in complex ways. In this subsection, we analyze how vendors navigate and reconfigure this liminal territory through three interrelated dimensions: 4.3.1 the structural pressures threatening their existence, including supermarket competition, real estate speculation, and the progressive loss of young labor; 4.3.2 the potential for collective co-projects, such as cooperatives, industrial kitchens, and direct marketing networks, that transform varejões into genuine “laboratories” of social innovation and food policy; and 4.3.3 a critical yet hopeful vision of the future, encapsulated in the recurring phrase: “the market won’t disappear, it will change.” This perspective reveals that vendors’ survival does not depend on top-down policy imposition, but on their continuous capacity for negotiation, adaptation, and co-production of territory, making the rural–urban transition a living space of agency and collective reinvention.

5.3.1. Urban Pressures

Vendors in Piracicaba face a triad of structural pressures that directly threaten the viability of their activity in the rural–urban transition: (i) competition with supermarkets, (ii) real estate speculation consuming agricultural land, and (iii) the progressive disinterest of new generations in farm work. Though distinct, these factors interact synergistically, accelerating sectoral aging and the marginalization of family farming.

- (i)

Supermarket competition: Supermarket competition is perceived as a growing threat. M6 summarizes it precisely: “Well... I think because of supermarkets, one day [the market] might end... but not yet, I don’t see it happening now... but over time, it could.” This concern is reinforced by M7, who acknowledges the competitive advantages of formal retail: “The trend is to shrink further, supermarkets sell everything we do, they have parking, more convenience... People go there and buy everything in one place, while here we only have these products.” Despite recognizing the superior quality of their goods, “ours is much better than theirs” (M7), vendors know that urban convenience (parking, product variety, extended hours) tends to attract consumers, especially younger ones.

- (ii)

Urban expansion and abandonment of farmland: Although less explicit, the risk of real estate speculation emerges in accounts about the uncertain future of peri-urban agriculture. M5 warns: “Here in Piracicaba, there’s [speculation], I think so, if things keep going this way, there are places being abandoned, left idle, I think it’ll be difficult.” This perception suggests that without public policies protecting agricultural land, areas near the city risk conversion into subdivisions or real estate developments, displacing smallholders. Land tenure insecurity thus operates as a silent but constant threat.

- (iii)

Loss of young labor: The most unanimous critique among interviewees concerns generational disconnect. RO1 states categorically: “Today’s youth don’t want anything to do with the countryside, with working in the fields... Most young people want to move to the city... technology... there’s no longer this idea of waking up at four in the morning to work... in fifteen or twenty years, there’ll be a food shortage.” P6 reinforces: “No... it’s very hard, you have to work a lot to make a living.” This view is shared even by those whose children tried and gave up: “My son worked as a cane cutter, even moved to the city, but couldn’t handle it and returned to the farm... so he stays at the street market and I’m at the varejão” (M7). Even in these cases of “return,” there is clear reservation about continuity. P1 expresses uncertainty: “The kids are still young... Nowadays you never know if they’ll stay, because most parents encourage their children to study, so they don’t end up in agriculture, in the fields.” This reveals a paradox: farmers themselves, by valuing formal education, reproduce the very logic that marginalizes them, encouraging their children to seek careers outside agriculture.

Despite generalized pessimism, there are signs of resistance. RO2, for example, envisions a future where the market becomes an “emporium” with coffee, tables for conversation, and organic products, precisely attracting the young audience that rejects the “hardship” of rural life but values leisure, quality, and connection to food origins. This vision suggests that, even under intense structural pressure, vendors do not merely lamente, they reimagine their space as a territory of sociability and differentiation, capable of engaging with new forms of urban consumption.

The urban pressures faced by Piracicaba’s vendors – supermarket competition, the threat of real estate speculation, and the progressive loss of young labor – are not isolated challenges but local expressions of a structural crisis of family farming in rural–urban transition zones, widely documented in the Global South. These phenomena reveal how unregulated urban expansion and the mercantile logic of consumption undermine the material and symbolic foundations of small-scale agricultural production. The rise of supermarkets as direct competitors to varejões resonates with analyses by de Bruin, Dengerink & van Vliet [

24], who highlight how urbanization reconfigures food systems, privileging long, standardized chains dependent on complex logistics. Meanwhile, short circuits, such as street markets and varejões, suffer from a lack of protective public policies, as noted by Jesus Silva et al. [

11] and Sparovek et al. [

10] in the Brazilian context, where policies often treat direct marketing channels as informal spaces to be “regularized,” rather than as strategic alternatives for food sovereignty.

The threat of real estate speculation on peri-urban farmland confirms findings by Daunt, Inostroza & Hersperger [

17] and Silva, Batistella & Moran [

40], who demonstrate how territorial planning in Brazil frequently fails to protect productive areas, subjecting them to real estate logics. Without protected agricultural zones or instruments for fair land valuation, smallholders become hostages to speculative markets, as evidenced by the implicit land tenure insecurity in vendors’ accounts. However, it is in the generational succession crisis that the social devaluation of agricultural work becomes most acute. The unanimous perception that “young people no longer want to stay in the countryside,” associating farming with “hardship” and “lack of future,” directly echoes diagnoses by Ellis [

5], Oestreicher et al. [

41], and Wiggins, Sabates-Wheeler & Yaro [

18] in African and Latin American contexts. This crisis is not merely demographic, but cultural and political, stemming from decades of policies that marginalized the countryside, while farmers themselves, recognizing the toil of the trade, encourage their children to seek “better lives” in cities, thus reproducing the logic that excludes them.

This reality contrasts sharply with the celebrated Chinese models described by Ge et al. [

1], Sun et al. [

2], and Tan et al. [

3], where the state actively coordinates rural revitalization by integrating spatial planning, technical assistance, and youth protection. In Piracicaba, by contrast, spatial governance, even when well-intentioned, operates with technical rigidity and social disconnection, ignoring the real conditions of agricultural livelihood reproduction. Thus, the solution lies not in more control, but in more dialogue and differentiation. As Ahmadzai, Tutundjian & Elouafi [

32] and Rakodi [

26] propose, sustainable agricultural policies must adopt a livelihoods-centered approach that recognizes productive heterogeneity, values local knowledge, and articulates production, marketing, and generational renewal. Likewise, as Zimmerer, Carney & Vanek [

30] and Drescher, Holmer & Iaquinta [

39] emphasize, family farming will only be viable if linked to ethical, agroecological, and identity-based values capable of attracting not only consumers but also new farmers.

Thus, the Piracicaba case reveals that the survival of family farming in the rural–urban transition does not depend on competing with formal retail, but on building niches of differentiated valorization supported by public policies sensitive to territorial complexity. Without this, spatial governance risks becoming a mere instrument of apparent order, one that organizes the market while accelerating the silent disappearance of the producer.

5.3.2. Potential for Co-Projects

Despite structural pressures and governance limitations, Piracicaba’s vendors do not limit themselves to defensive resistance. They imagine, design, and, in some cases, already implement collective initiatives that transform the market into a space of social and economic innovation. These co-projects, especially cooperatives and value-added enterprises, reveal a deep desire to redefine labor relations, marketing, and governance in the rural–urban transition.

The idea of a cooperative recurrently emerges as a strategy to overcome the limits of individual action. M3 articulates this vision most clearly: “We’re thinking of forming a cooperative to access larger markets... One person alone can’t do it, but together we can.” He is already implementing this through an industrial kitchen project supported by CATI: “We’ll build a shed, install processing machines, and buy a truck...” This initiative is not isolated. M5 recounts attending a cooperative workshop with real impact: “I liked it, a lecture on cooperativism... it seems some people actually opened a cooperative.” Though he acknowledges that, in his line (ornamental plants), cooperatives “don’t work well,” the fact that others succeeded shows the idea is both viable and desired.

Some vendors see the market not just as a sales point, but as a space for experimentation, education, and new market construction. RO2, for example, describes his stall as an “emporium under construction”: “I want this stall to be bigger, with more product diversity, a differentiated stall... I want to turn it into a kind of emporium: refrigerator, organic wheat pasta, free-range eggs, stuffed eggplant...” He also links sales to food education: “I want to create an organic garden, we’re in contact with SESCviii to offer courses on organic farming.” This vision transforms the varejão into a living laboratory of food policy, where theory and practice merge. The market ceases to be merely a regulated space and becomes a territory for co-constructing knowledge and practices.

Even without formal structures, informal cooperation networks exist. RO2 affirms: “Among those working with organic products, it’s really great, one helps the other, both in logistics and production... We exchange seeds, do technical visits... There are 17 producers working together, and it’s really nice.” This ethics of reciprocity sharply contrasts with the competitive logic imposed by SEMA’s governance. Here, the market becomes a space of productive solidarity, where collective success is valued more than individual gain.

Vendors recognize that these co-projects require institutional support, not as control, but as facilitation. RO2 proposes: “There could be more incentives... an agronomist from the city government visiting existing producers, encouraging them... neighbors working together... pushing for bigger things.” This statement reveals that the demand is not for more inspection, but for mediation, capacity-building, and co-design, a governance that stands alongside producers, not above them.

The co-project initiatives in Piracicaba – cooperatives, industrial kitchens, organic networks, food education – show that vendors not only critique current governance but propose concrete alternatives, transforming varejões into laboratories of food and territorial policy. This self-organizing capacity resonates with Özman & Taşan-Kok’s [

14] findings in Istanbul, where urban communities develop “innovative self-organization strategies” in response to formal governance failures. Moreover, the emphasis on cooperation over competition confirms the thesis of Drescher, Holmer & Iaquinta [

39] and Zimmerer, Carney & Vanek [

30]: production systems based on trust, reciprocity, and shared knowledge are more resilient and sustainable than those based solely on market efficiency. The organic network described by RO2 is a living example of this logic.

These practices also challenge the top-down Chinese model celebrated by Ge et al. [

1] and Sun et al. [

2]. In Piracicaba, innovation emerges from below, through the collective agency of smallholders, as noted by Rakodi [

26] and Ahmadzai, Tutundjian & Elouafi [

32], who argue that effective policies must not only support but learn from local initiatives.

Finally, viewing the market as a “laboratory” allows spatial governance to be tested, adapted, and co-constructed with local actors. As de Bruin, Dengerink & van Vliet [

24] and Kato, Delgado & Romano [

31] propose, the future of agricultural livelihoods in the rural–urban transition depends precisely on this capacity to co-design territory. Thus, the Piracicaba case shows that, even under pressure, smallholders are not mere survivors but architects of alternative futures, provided spatial governance recognizes them as partners, not targets of intervention.

5.3.3. A Critical Vision of the Future