1. Introduction

Tumor evolution is driven by the dynamic interactions among diverse cellular populations that compete and cooperate within a fluctuating microenvironment. This heterogeneity enables malignant progression, therapeutic resistance, and relapse—making it one of the central challenges in oncology. While genomic instability generates variation, it is the ecological and evolutionary interactions among coexisting phenotypes that determine which traits persist. Despite extensive modeling efforts, most evolutionary game-theoretic descriptions of tumor heterogeneity remain restricted to two or three phenotypic strategies, limiting their ability to capture higher-order ecological feedbacks and cooperative effects observed in real tumors.

Within evolutionary game theory, tumor cell phenotypes are interpreted as strategies whose fitness emerges through frequency-dependent ecological interactions rather than intentional optimization. Fitness differences arise from ecological interactions rather than intentional choice, as each phenotype’s reproductive success depends not only on its intrinsic properties but also on the composition of the surrounding population. In this context, fitness represents the expected reproductive potential of a phenotype relative to others, integrating proliferation rate, survival probability, and environmental adaptability rather than simple reproductive output. EGT thus provides a natural framework for describing the competitive and cooperative interactions that drive tumor heterogeneity. Numerous studies have successfully applied this approach to simplified tumor systems, such as two- or three-phenotype games capturing cooperation, glycolytic competition, or resistance trade-offs. However, these models often neglect critical ecological feedbacks—such as microenvironmental modulation, spatial constraints, and stochastic fluctuations—that are fundamental to real tumor evolution. The tumor microenvironment defines the evolving context in which phenotypes interact; nutrient gradients, acidity, and spatial constraints continuously reshape the payoff landscape that governs evolutionary dynamics.

In this work, we introduce a four-phenotype EGT model that captures the interplay between:

Proliferative cells (P) — rapidly dividing but resource-sensitive,

Invasive cells (I) — motile and adaptive to spatial gradients,

Resistant cells (R) — tolerant to therapeutic stress, and

Cooperative cells (C) — producers of shared public goods such as growth factors or extracellular modifiers.

The model formalizes how these phenotypes compete for limited resources while modulating their environment. We first analyze the deterministic replicator dynamics, identifying equilibria and coexistence regimes, and then extend the framework to a stochastic formulation using Itô calculus to represent environmental noise and demographic variability. This stochasticity captures biologically realistic fluctuations that can maintain phenotypic diversity even when deterministic dynamics would predict dominance.

By integrating frequency-dependent selection, microenvironmental feedback, and stochastic effects within a single framework, this study bridges ecological and evolutionary perspectives of cancer. The results provide mechanistic insights into how tumors sustain heterogeneity and suggest how adaptive therapeutic strategies might exploit these dynamic ecological equilibria to delay or prevent resistance.

Evolutionary game theory extends classical game theory by analyzing frequency-dependent success of strategies in populations [

1]. In cancer, the fitness of a given phenotype depends not only on its intrinsic traits but also on the composition of the surrounding tumor cell population. For example, proliferative cells may dominate nutrient-rich niches, while resistant or cooperative phenotypes gain advantages under stress or hypoxia. Similarly, invasive cells may exploit ecological opportunities created by other phenotypes, such as acidic niches or disrupted extracellular matrix.

EGT has been used to explain coexistence, competitive dynamics, and cooperation among tumor cells. Cooperative behaviors, such as secretion of growth factors or extracellular matrix remodeling, create public goods that benefit all cells in the vicinity, including non-producers. These dynamics lead to social dilemmas analogous to the "tragedy of the commons" [

2], and their stability depends on mechanisms like spatial clustering or frequency-dependent selection [

3]. For instance, invasive cells may exploit niches generated by proliferative or cooperative cells, while resistant cells may persist under therapeutic stress, shaping the tumor’s evolutionary landscape [

4].

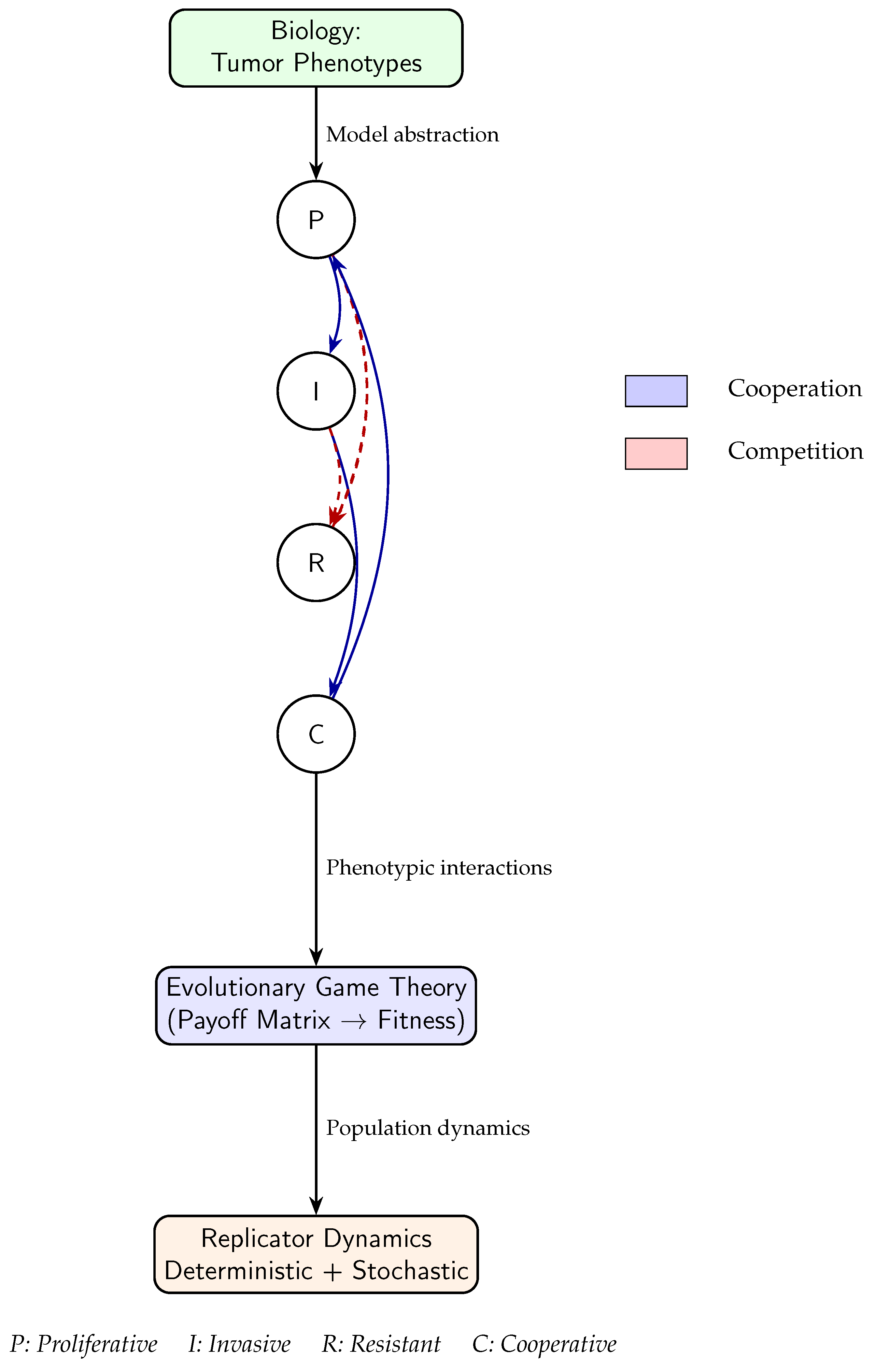

Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual bridge between biological complexity and the mathematical formalism of our EGT framework. At the left, diverse tumor phenotypes, proliferative (P), invasive (I), resistant (R), and cooperative (C), represent the heterogeneous cellular strategies observed in real tumors. Their ecological interactions, indicated by blue (cooperative) and red (competitive) arrows, define a dynamic network of frequency-dependent fitness relationships. These interactions are abstracted into a payoff matrix within the EGT framework, which quantifies how the success of each phenotype depends on the composition of the surrounding population. The resulting fitness landscape then informs the replicator dynamics, deterministic and stochastic formulations that describe how population frequencies evolve over time. Together, this schematic links biological processes to their formal dynamical representation, providing intuition for how microenvironmental interactions give rise to emergent tumor behavior.

In this work, we introduce a four-phenotype evolutionary game-theoretic model incorporating proliferative, invasive, resistant, and cooperative strategies within a unified deterministic–stochastic framework. We show that the explicit inclusion of cooperative dynamics generates qualitatively new coexistence regimes and noise-stabilized evolutionary states that are not accessible in lower-dimensional models. By integrating frequency-dependent selection, stochastic fluctuations, and microenvironmental modulation, the model provides a cohesive ecological description of tumor heterogeneity.

The purpose of this work is primarily exploratory and integrative. Rather than introducing new replicator theory or stochastic process results, we construct and analyse a higher-dimensional evolutionary game motivated by tumor ecology, and systematically explore its deterministic and stochastic dynamics under biologically interpretable parameter regimes. The emphasis is on qualitative dynamical behavior and comparative scenarios, in line with the scope of applied mathematical modeling.

2. Background and Motivation

2.1. Basics of Game Theory

Game theory provides a quantitative framework for modeling interactions among multiple decision-makers, or “players,” each seeking to maximize a defined payoff [

5]. In the context of tumor biology, these players are typically individual cells or subpopulations of cells with distinct phenotypic strategies, such as varying levels of proliferation, motility, or metabolic adaptation [

6,

7]. A cell’s strategy thus corresponds to a behavioral or physiological trait, while the associated payoff represents its reproductive success, an integrated measure of proliferation rate, survival probability, and tolerance to environmental stressors [

8,

9].

Crucially, cellular interactions within tumors are

frequency-dependent: the fitness of a particular phenotype depends on its relative abundance within the population and on the strategies of coexisting cell types [

10,

11]. Unlike classical zero-sum games, where one player’s gain equals another’s loss, tumor ecosystems are dominated by

non-zero-sum interactions. In such settings, cooperative behaviors, such as secretion of growth factors, extracellular matrix remodeling, or angiogenic signaling, can increase the overall fitness of multiple neighboring cells, including those that do not contribute to the cooperative act [

12,

13].

Canonical evolutionary games, such as the Hawk–Dove and Public Goods games, have been extensively used to model competition and cooperation in tumor cell populations and will not be reviewed here in detail.

Canonical examples from evolutionary game theory illustrate these principles. The Hawk–Dove game models the balance between aggressive and non-aggressive phenotypes competing for shared resources, offering insight into the coexistence of invasive and quiescent tumor cell populations [

14]. The Public Goods game captures the dynamics of cooperation versus cheating, where producer cells generate costly but beneficial public goods, such as growth factors or extracellular enzymes, while non-producers exploit these resources without contributing [

7,

15]. These frameworks have proven instrumental in elucidating how intra-tumor heterogeneity, cooperation, and competition collectively shape tumor evolution and therapeutic resistance.

2.2. Tumor Heterogeneity and Evolution

Tumor heterogeneity arises from the interplay of genetic mutations, epigenetic modifications, and microenvironmental variability, producing a mosaic of phenotypically distinct subpopulations within the same neoplasm [

16,

17]. These differences encompass variations in proliferation rate, metabolic phenotype, motility, immune evasion, and therapy resistance. The emergence and persistence of such diversity are governed by Darwinian selection, whereby phenotypes that are optimally adapted to local conditions, including nutrient gradients, hypoxia, immune pressure, or therapeutic stress, gain a reproductive advantage and expand preferentially [

18,

19].

Incorporating evolutionary game theory into this framework allows for modeling not only the competition among cancer cell phenotypes, but also their potential for cooperation and exploitation. Rather than treating fitness as an intrinsic property of each clone, EGT defines fitness as a

frequency-dependent quantity that varies with the strategic composition of the tumor population [

6,

7]. For example, cooperative phenotypes that secrete diffusible growth factors or remodel the extracellular matrix can increase the carrying capacity and growth rate of both themselves and neighboring cells. These cooperative cells effectively generate a

public good, enhancing tumor proliferation but incurring a metabolic cost [

15,

20,

21]. In contrast, “cheater” phenotypes that do not contribute to this public good can exploit the improved conditions without bearing the associated cost, thereby destabilizing cooperation.

Similarly, invasive phenotypes may benefit from niches modified by proliferative or angiogenic cells, migrating toward resource-rich regions created by these interactions [

14,

22]. Resistant phenotypes, on the other hand, maintain survival under therapy-induced stress, potentially benefiting from protective signals or growth factors produced by neighboring cells [

23]. Thus, EGT provides a natural mathematical framework for capturing the coexistence of diverse cellular strategies, as well as the dynamic trade-offs that sustain intratumoral heterogeneity.

Spatial structure further modulates these interactions by imposing local constraints on cell–cell communication and resource availability [

24,

25]. Cells in the hypoxic, nutrient-poor tumor core often experience selection for glycolytic metabolism and stress tolerance, while those at invasive edges face selection for motility and matrix degradation capacity [

26,

27]. This spatially varying fitness landscape promotes diversification, allowing multiple strategies to coexist through local adaptation and ecological niche partitioning. Consequently, the tumor can be viewed as an evolving ecosystem in which spatial, metabolic, and cooperative interactions jointly determine evolutionary trajectories and therapeutic responses.

3. Game-Theoretic Models in Tumor Biology

We model the interactions among four distinct phenotypes, denoted P, I, R, and C, through the framework of evolutionary game theory, using a payoff matrix formalism. This approach allows us to represent the tumor as an evolving ecological system in which subpopulations compete, cooperate, and adapt in response to one another. As mentioned above, each phenotype corresponds to a biologically relevant and interpretable strategy that reflects distinct cellular behaviors and resource-utilization patterns within the tumor microenvironment. Specifically, we may interpret P as a proliferative phenotype that prioritizes rapid cell division; I as an invasive phenotype characterized by motility and tissue degradation; R as a resistant phenotype that survives under therapeutic or environmental stress; and C as a cooperative or cytokine-producing phenotype that contributes to the collective fitness of neighboring cells through diffusible factors.

Within this context, cooperative and competitive interactions among tumor subpopulations can often be framed as variants of the

Prisoner’s Dilemma (PD) game. The PD is characterized by the payoff ordering

, where

T represents the temptation to defect,

R the reward for mutual cooperation,

P the punishment for mutual defection, and

S the sucker’s payoff. Although mutual cooperation yields the highest collective benefit, natural selection acting on individual fitness tends to favor defectors, leading to an overall reduction in population-level performance. In tumor ecosystems, this dilemma manifests when cooperative phenotypes such as

C secrete growth factors or cytokines that enhance local proliferation, while non-cooperative phenotypes exploit these public goods without incurring the metabolic cost of production. As demonstrated in theoretical and computational studies of tumor metabolism and microenvironmental signaling [

7,

14,

28], such PD-like interactions predict the instability of cooperation in well-mixed populations unless stabilizing mechanisms—for example, spatial structure, kin selection, or resource feedback regulation—are present. These insights underscore the importance of considering eco-evolutionary dynamics when designing therapies that target metabolic cooperation or collective resistance in cancer.

In this framework, the state of the tumor population at any given time is described by the vector of phenotype frequencies:

where

represents the fraction of the total population adopting phenotype

i. Since these fractions represent proportions, they are constrained to the simplex defined by the normalization condition

Here, the components of x represent an evolving ecological composition rather than fixed clonal identities, allowing phenotypic frequencies to adapt continuously to population structure and environmental context. This simplex can be visualized as a tetrahedral space in which every interior point corresponds to a polymorphic mixture of phenotypes, while the vertices represent pure, monomorphic states.

The success or reproductive performance of each phenotype depends both on its intrinsic biological characteristics and on its interactions with the other phenotypes in the population. These pairwise interactions are encoded in a payoff matrix

, where

quantifies the expected payoff (or fitness contribution) to phenotype

i from interacting with phenotype

j. The resulting expected fitness of phenotype

i within the mixed population is obtained by averaging these payoffs over the distribution of phenotypes:

while the population-average fitness is given by

The difference

thus measures the relative advantage (or disadvantage) of phenotype

i compared to the mean of the population.

The temporal evolution of the population composition is governed by the replicator equation,

which captures the essence of Darwinian selection in a continuous, frequency-dependent setting. According to this equation, phenotypes whose fitness exceeds the population average will grow in abundance, while those performing below average will decline. Importantly, because the dynamics are confined to the simplex, the total population fraction is conserved over time.

The replicator formalism provides a natural and powerful way to analyze tumor evolution as an adaptive process. It reveals how microscopic cellular behaviors and ecological interactions scale up to determine macroscopic evolutionary outcomes such as coexistence, dominance, or cyclic competition. For example, if proliferative cells (P) gain high payoffs when interacting with cooperators (C) but are outcompeted by resistant cells (R) under stress, the resulting dynamics may exhibit transient cooperation followed by resistance-driven dominance. Conversely, if invasive phenotypes (I) exploit the presence of proliferative cells, spatial heterogeneity and clonal diversity may be sustained through frequency-dependent feedbacks.

This formulation thus bridges the gap between mechanistic cell biology and evolutionary theory. By embedding phenotypic traits within an ecological payoff structure, we can explore how changes in cellular costs, environmental pressures, and cross-phenotype benefits influence the direction and stability of tumor evolution. Moreover, the model can be extended to incorporate therapy-induced selection, spatial segregation, or stochastic fluctuations, providing a flexible foundation for understanding the complex adaptive dynamics of heterogeneous cancers.

The payoff matrix

A is defined in terms of biologically interpretable parameters that reflect both intrinsic and interaction-based effects:

No attempt is made to calibrate this matrix to specific experimental datasets; parameter values are chosen to represent qualitative ecological trade-offs commonly discussed in the tumor evolution literature.

This parametrization separates intrinsic phenotypic costs (diagonal terms) from interaction-driven fitness modulation (off-diagonal terms), facilitating systematic analysis of how cooperation and competition jointly shape evolutionary stability.

Here, each diagonal element captures the intrinsic cost associated with maintaining phenotype i, such as the energetic burden of rapid proliferation or the metabolic penalty of therapy resistance. The off-diagonal terms describe how phenotypes interact with one another. Parameters such as represent benefits gained from heterotypic interactions (e.g., cooperative support or growth stimulation), while quantify competitive suppression or synergistic cooperation between pairs of phenotypes.

4. Numerical Simulation and Phase Analysis

Rather than fitting data, the numerical parameter set is chosen to reflect qualitative trade-offs consistently reported across tumor ecology studies, allowing us to illustrate generic dynamical behaviors rather than case-specific predictions. Accordingly, numerical results should be interpreted as illustrative of possible dynamical regimes, rather than as predictive or quantitative descriptions of specific tumor systems.

To illustrate the behavior of the four-phenotype replicator system, we consider a representative numerical example grounded in biologically realistic assumptions derived from the tumor ecology and evolutionary game theory literature. The parameterization of the payoff matrix is guided by empirical and theoretical insights into the trade-offs that shape cancer cell phenotypes, including proliferation, invasiveness, therapy resistance, and cooperation. Each phenotype experiences an intrinsic cost associated with maintaining its defining traits, denoted by , and engages in a complex network of pairwise interactions with other phenotypes that may be competitive, neutral, or synergistic. This structure captures the ecological essence of tumor heterogeneity, where diverse cell types coexist and interact through shared resources, signaling molecules, and environmental modifications.

The intrinsic cost parameters, represented by the diagonal terms

, quantify the fitness penalties of sustaining specialized cellular programs. Proliferative cells (

P) generally bear a moderate cost (

) due to their rapid division rates and consequent sensitivity to stress and nutrient limitation. Invasive cells (

I) experience a slightly higher cost (

) because of the energetic demands associated with motility, matrix degradation, and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Resistant cells (

R) typically pay a substantial metabolic price (

) for maintaining resistance mechanisms such as efflux pumps, DNA repair, or quiescence. Cooperative or cytokine-producing cells (

C) also face a notable cost (

) as they divert resources from proliferation toward the secretion of diffusible factors that benefit the tumor microenvironment. These cost magnitudes are consistent with the ranges used in previous theoretical cancer models [

6,

15,

20,

29].

The off-diagonal entries of the payoff matrix capture interphenotypic interactions, reflecting how one phenotype’s activity influences the fitness of another. In the tumor context, proliferative cells provide diffusible growth factors and metabolites that can be exploited by other types; thus, invasive cells often derive a fitness gain from the presence of proliferatives, represented here by a positive interaction coefficient

. Resistant cells, although intrinsically costly, may benefit indirectly from proliferative and cooperative neighbors that maintain favorable conditions, modeled as

. Cooperative cells contribute positively to others through signaling and metabolic exchange, yielding modest benefits to proliferative and invasive cells (

and

, respectively). Conversely, competitive suppression among phenotypes is introduced through parameters such as

,

, and

, representing resource competition, spatial exclusion, or negative feedback between cell types. These parameter magnitudes align with empirically motivated models of cellular social dilemmas in cancer [

6,

15,

20].

Substituting these values into the general parametric form yields the payoff matrix

This configuration encodes a biologically plausible ecosystem of interacting phenotypes. Proliferative cells perform strongly in isolation, but their advantage diminishes in the presence of invasive and resistant competitors that exploit their metabolic output or occupy nearby spatial niches. Invasive cells thrive when proliferative cells are abundant, benefiting from secreted growth factors and the structural degradation of the extracellular matrix. Resistant cells, despite paying a high intrinsic cost, can persist because they receive indirect benefits from cooperators and proliferatives that maintain an environment conducive to survival under stress. Cooperative cells bear the heaviest individual cost yet provide system-level stability by enhancing the fitness of others through paracrine or metabolic support. The net effect is an ecologically interdependent system where no single phenotype is universally optimal.

To explore the resulting evolutionary dynamics, we consider an initial condition corresponding to a heterogeneous tumor composed of 40% proliferative, 30% invasive, 20% resistant, and 10% cooperative cells, that is,

Integration of the replicator equations under these parameters reveals a rich dynamical landscape. Depending on the precise balance of costs and benefits, the system can evolve toward qualitatively distinct equilibria. When cooperative benefits are sufficiently strong to offset their intrinsic costs, all four phenotypes can coexist in a stable equilibrium where each type maintains a finite fraction of the population. If the cost of cooperation or proliferation rises, selection may instead favor stress-tolerant phenotypes such as invasive or resistant cells, leading to dominance of one or two phenotypes and a reduction in diversity. In certain asymmetric regimes, where specific payoff inequalities produce cyclic advantage relations (for example,

), the system exhibits oscillatory or quasi-periodic behavior akin to rock–paper–scissors dynamics. Such cycles have been described in ecological and microbial systems [

30,

31] and may reflect transient clonal turnover observed in evolving tumors.

This numerical example illustrates how relatively simple, parameterized interaction rules can give rise to complex adaptive behavior in a tumor ecosystem. The model highlights that cancer progression cannot be understood solely in terms of intrinsic growth rates but must instead be viewed as the emergent outcome of frequency-dependent selection among interacting phenotypes. The payoff framework thus offers a flexible and mechanistically interpretable foundation for studying how cooperation, competition, and resistance interact to shape tumor evolution and therapy response, consistent with the growing body of literature treating cancer as an evolving ecological system [

6,

15,

32].

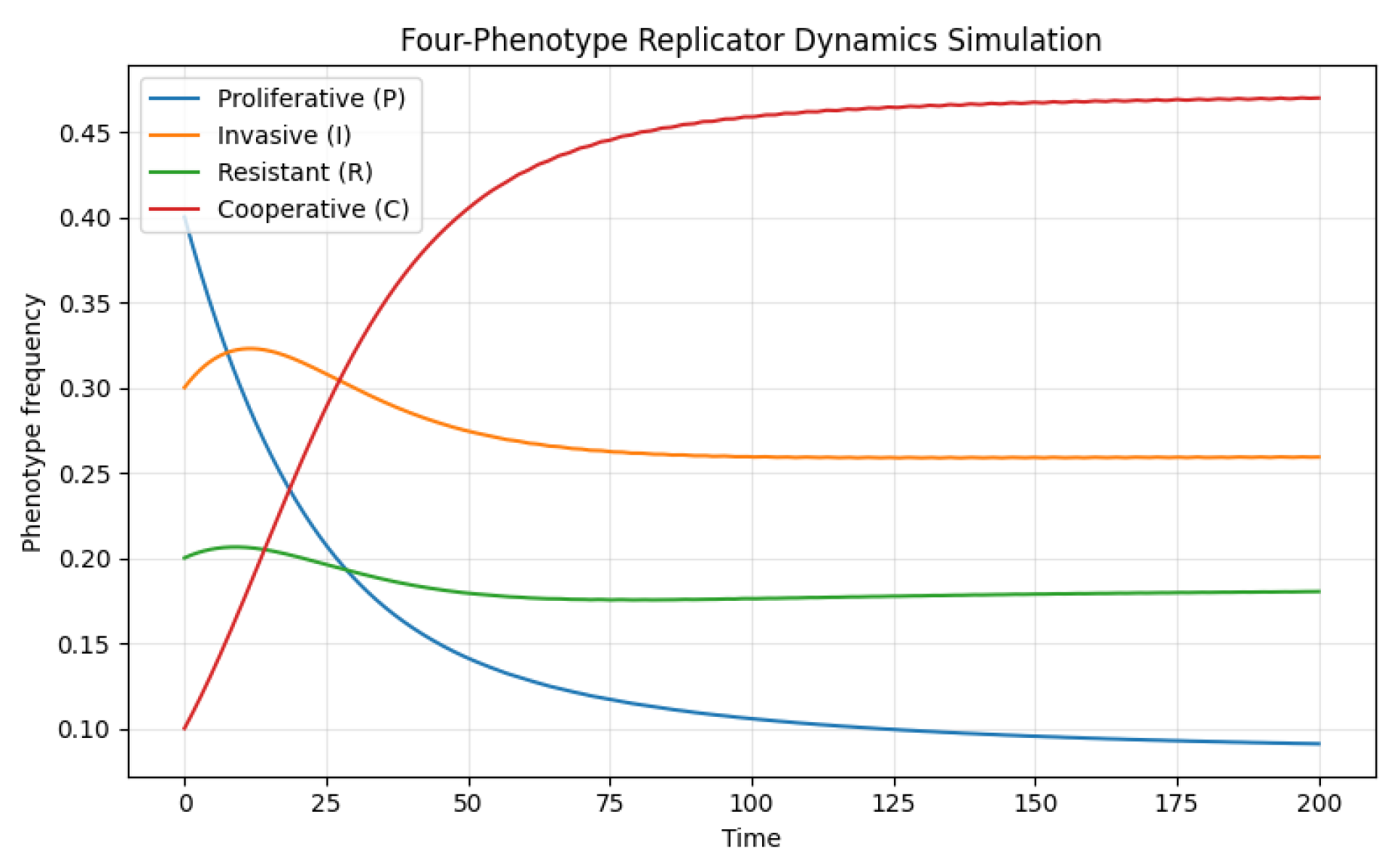

The numerical integration of the four-phenotype replicator dynamics

Figure 2 reveals how differential costs and benefits drive the eco-evolutionary trajectories of tumor cell populations. Initially, proliferative (

P) cells dominate due to their relatively high baseline fitness; however, invasive (

I) cells gain frequency as they exploit the metabolic and structural support provided by proliferatives. Resistant (

R) cells, burdened by their higher intrinsic cost, remain at lower frequencies but persist stably in the population, benefiting indirectly from the cooperative effects mediated by other phenotypes. Cooperative (

C) cells, although costly to maintain, gradually rise from their initially small fraction as their positive influence on the fitness of others enhances overall system stability.

The trajectories typically converge toward a polymorphic equilibrium where all four phenotypes coexist at nonzero frequencies. This equilibrium reflects a balance between intrinsic costs and cross-type interactions—illustrating how tumor heterogeneity can be maintained by frequency-dependent selection. Depending on small perturbations in parameters, the same system can instead exhibit cyclic or quasi-stable oscillations in phenotype abundance, echoing “rock–paper–scissors” dynamics commonly observed in ecological and microbial communities. Such oscillatory patterns represent evolutionary arms races among cancer cell strategies, where the success of one phenotype periodically undermines itself by creating conditions that favor another.

Overall, this simulation emphasizes that tumor evolution is not a linear march toward dominance by a single clone but rather an adaptive process governed by interaction-dependent fitness landscapes. Cooperative and competitive forces together produce dynamic stability that could explain persistent intratumoral heterogeneity observed in experimental and clinical settings.

5. Integrating Stochastic Dynamics into the Four-Phenotype Model

While the deterministic replicator dynamics capture the mean-field behavior of large, well-mixed populations, real tumor ecosystems are subject to substantial effective stochastic fluctuations arising from microenvironmental variability and unresolved interaction-level heterogeneity, microenvironmental variability, and random molecular events. Such fluctuations can profoundly influence evolutionary outcomes by driving transitions between metastable states, enabling the persistence of rare phenotypes, or inducing stochastic extinction events. Importantly, stochasticity does not merely perturb deterministic trajectories but can qualitatively reshape evolutionary dynamics by stabilizing otherwise transient phenotypic configurations. To account for these effects, we extend the four-phenotype evolutionary game model by introducing a stochastic term that captures demographic and environmental noise.

In this stochastic framework, the temporal evolution of each phenotype fraction

is described by a

stochastic replicator equation [

33] of the form

where

denotes an independent Wiener process (standard Brownian motion) associated with phenotype

i, and

is a nonnegative constant representing the intensity of stochastic fluctuations. The first term on the right-hand side corresponds to the deterministic replicator dynamics previously defined, while the second term introduces multiplicative noise that scales with both the abundance of phenotype

i and its available fraction of the population, ensuring that stochasticity vanishes when

or

, consistent with biological constraints on population fractions. The stochastic term in Eq. (

7) is introduced as a phenomenological representation of effective environmental and interaction-level fluctuations, rather than as a microscopically derived model of demographic stochasticity. In contrast to classical Wright–Fisher or Moran-type limits, Eq. (

7) is not intended to represent exact finite-population sampling noise.

We note that, unlike the deterministic replicator equation, the stochastic system (

7) does not strictly preserve the simplex almost surely. In particular, the noise term does not enforce the constraint

pathwise. Throughout this work, trajectories are interpreted in a numerical and phenomenological sense, remaining close to the simplex interior for moderate noise amplitudes.

The stochastic contribution may be interpreted in two complementary ways. From a demographic perspective, quantifies fluctuations arising from finite population sampling, cell division randomness, or stochastic death events. From an environmental perspective, it reflects fluctuations in nutrient availability, local oxygen tension, or therapy intensity that differentially affect cell fitness. In heterogeneous tumors, both sources of noise are relevant: proliferative phenotypes, for example, may experience higher demographic variability due to rapid turnover, whereas resistant cells may face environmental fluctuations associated with drug exposure. Hence, one might assign , , , and , corresponding to modest but biologically plausible stochastic amplitudes.

In the presence of noise, the system’s behavior is best described in terms of

probability distributions over the simplex of phenotype frequencies rather than deterministic trajectories. The time evolution of these distributions can be expressed through the corresponding

Fokker–Planck equation, which governs the probability density

for the state vector

:

Equation (

8) is written in a formal sense to support qualitative interpretation of the stochastic dynamics. No attempt is made to analyse its solutions, specify boundary conditions on the simplex faces, or derive stationary distributions explicitly. Its role here is purely conceptual, providing intuition for noise-induced spreading around deterministic attractors.

From a biophysical standpoint, stochasticity can be viewed as introducing an effective evolutionary temperature that perturbs the fitness landscape, allowing the population to explore otherwise inaccessible regions of the phenotype space. In this sense,

plays a role analogous to thermal noise in statistical physics, enabling transitions between metastable evolutionary states [

34].

Applying this stochastic extension to the four-phenotype tumor model yields several biologically significant consequences. Rare phenotypes such as cooperative cells, which may decline deterministically due to their intrinsic cost, can persist for extended periods under the influence of noise. Stochastic fluctuations periodically replenish their frequency, thereby maintaining functional heterogeneity within the tumor. Transitions between dominance regimes—such as shifts from proliferative to resistant states—can occur spontaneously due to noise-induced drift, even in the absence of external perturbations like therapy. The combination of stochastic diffusion and frequency-dependent selection can generate quasi-cyclic behavior, where the system fluctuates around an unstable deterministic cycle without converging to a fixed point, producing temporal heterogeneity reminiscent of clonal sweeps observed in longitudinal tumor sequencing data [

35,

36].

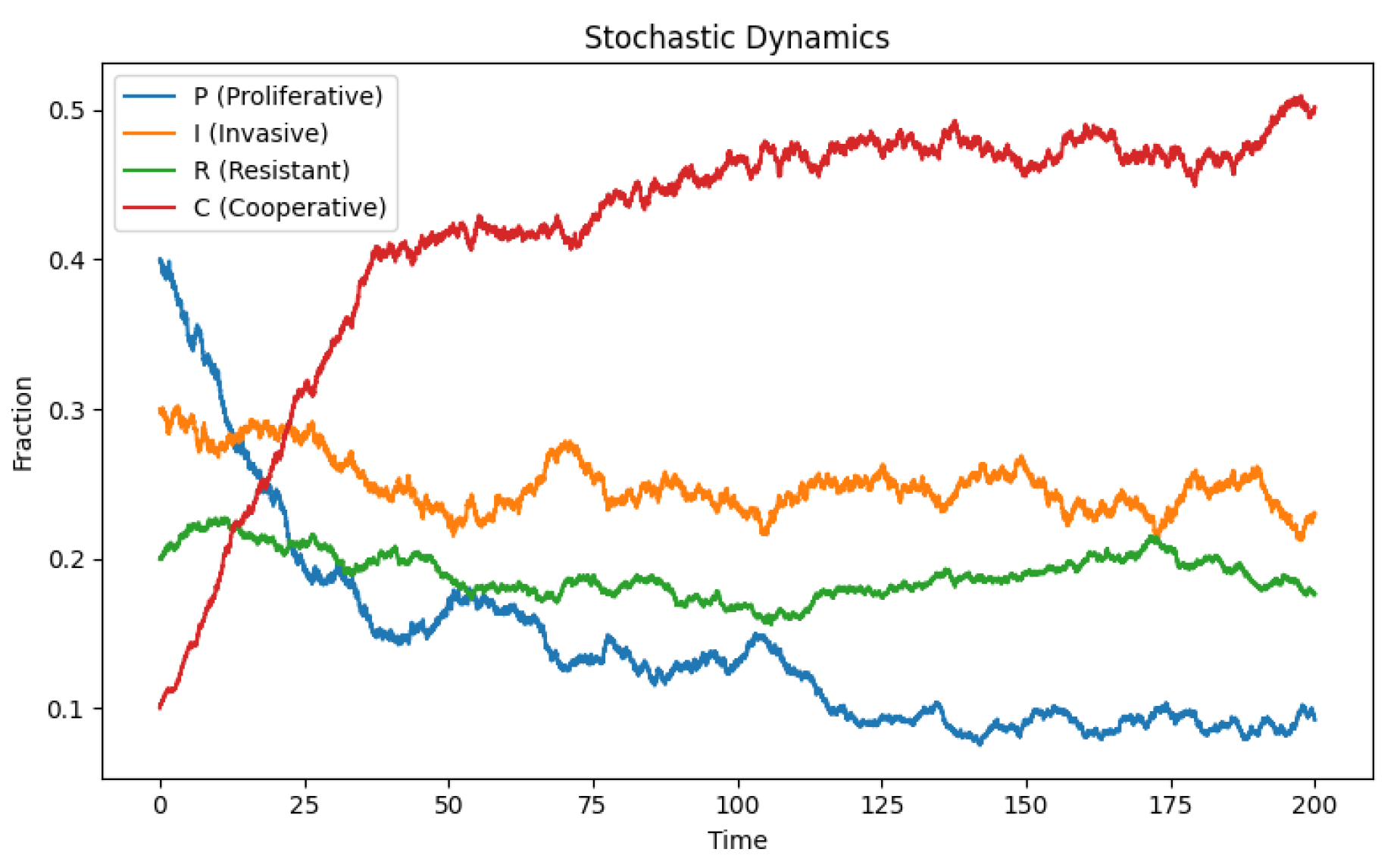

Numerical simulations of the stochastic replicator system

Figure 3 confirm these qualitative predictions. When integrated using standard Itô schemes, the trajectories exhibit fluctuations around the deterministic equilibrium with amplitudes proportional to the noise strength. For moderate

, the stationary state of the system is no longer a single equilibrium but a probabilistic cloud spanning a region of the simplex. Increasing stochasticity further transforms the dynamics into an ergodic wandering among different phenotype compositions, indicating that tumor heterogeneity may be dynamically maintained through noise rather than deterministic balance alone [

37,

38].

The combined deterministic and stochastic framework provides a comprehensive description of tumor evolutionary dynamics. Deterministic replicator equations capture selection-driven trends, while stochastic extensions incorporate fluctuations critical for realistic modeling of heterogeneous tumors. This approach bridges micro-level interaction rules with macro-level evolutionary outcomes, offering insight into the maintenance of diversity and the emergence of therapy resistance.

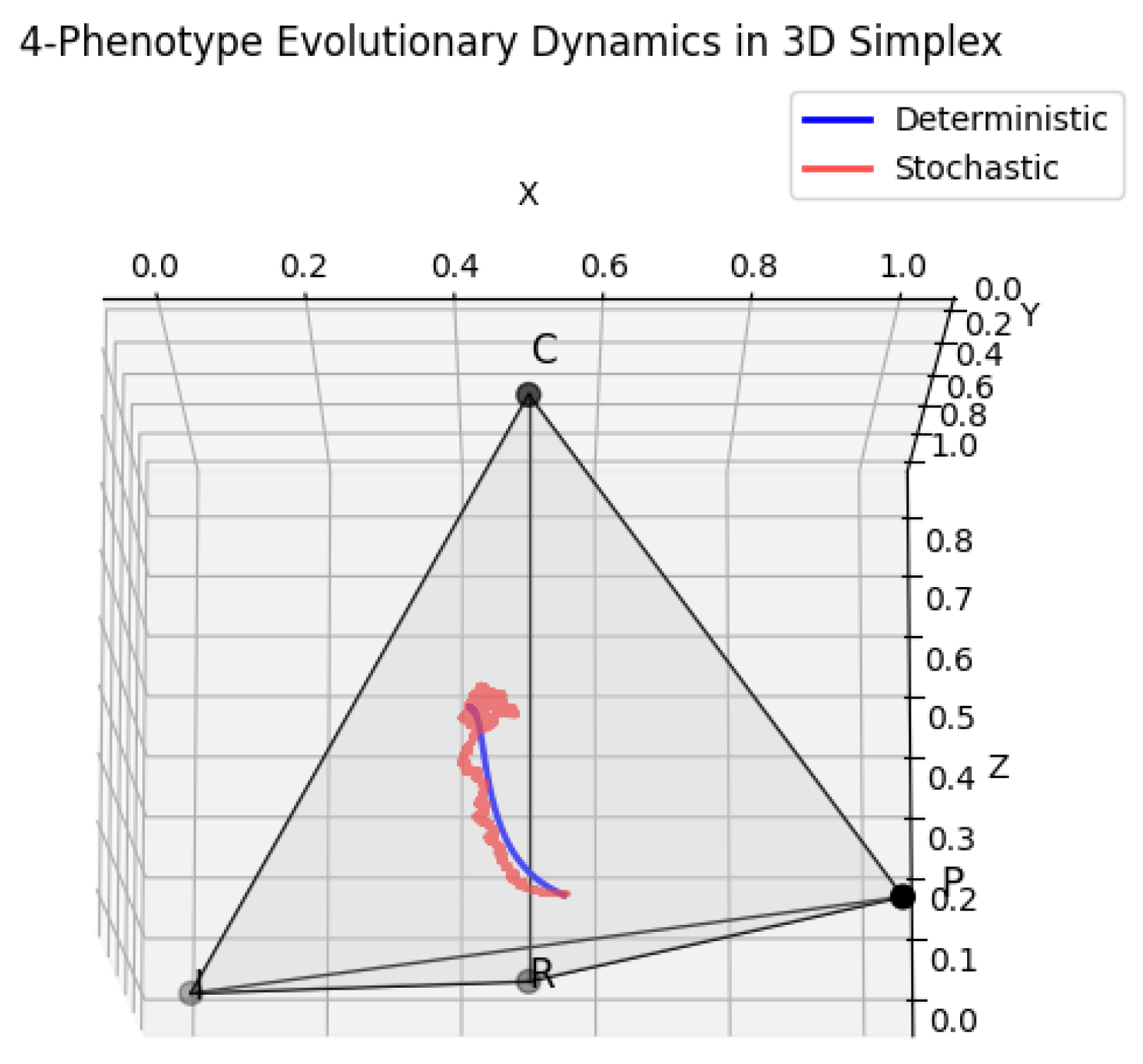

5.1. 3D Simplex Visualization of Stochastic and Deterministic Dynamics

The evolutionary dynamics of a heterogeneous tumor, comprising multiple phenotypes, can be naturally represented on a

simplex, where each vertex corresponds to a pure phenotype and interior points describe mixed populations. For a system of four phenotypes (

), the population fractions

reside on a

3-simplex Figure 4, which is a tetrahedron embedded in four-dimensional space. Visualizing trajectories in this high-dimensional space is inherently challenging; therefore, a projection into three dimensions using barycentric coordinates provides an intuitive and geometrically faithful representation of the population dynamics.

In this framework, each vertex of the tetrahedron represents a homogeneous population dominated by one phenotype, while any point inside the tetrahedron corresponds to a specific combination of phenotype abundances that sum to unity. Deterministic dynamics, governed by the classical replicator equations, produce smooth trajectories that tend toward stable equilibria or oscillatory cycles within the simplex, reflecting the outcomes of pure selection based on the defined payoff matrix. In contrast, stochastic dynamics, implemented through an Euler–Maruyama scheme, incorporate intrinsic or extrinsic noise in the system, such as random fluctuations in cell interactions, microenvironmental variability, or mutation events. These stochastic perturbations generate trajectories that deviate from the deterministic paths, sometimes visiting corners or edges of the simplex that deterministic evolution would rarely reach.

The resulting 3D simplex visualization

Figure 4 enables a direct and intuitive comparison between deterministic and stochastic trajectories. Deterministic paths illustrate the baseline selection-driven flow of the population, showing which phenotypes are favored under fixed interaction rules. Stochastic trajectories, often overlaid in the same plot, reveal the variability induced by noise, highlighting transient dominance of rare phenotypes, coexistence phenomena, and the exploration of otherwise inaccessible regions of the simplex. Collectively, this visualization provides a powerful tool to understand the complex interplay between deterministic selection and stochastic fluctuations, offering insights into the maintenance of tumor heterogeneity, the emergence of subclonal diversity, and the potential for therapeutic resistance. By mapping four-dimensional evolutionary dynamics into a three-dimensional tetrahedral space, researchers gain an accessible and interpretable picture of how microscopic interactions translate into macroscopic ecological outcomes within tumor ecosystems.

6. Deterministic vs Stochastic Dynamics

The comparison between deterministic and stochastic simulations of the four-phenotype evolutionary game provides significant insights into the interplay between selection and random fluctuations in heterogeneous tumor ecosystems. In the deterministic setting, the replicator equation was solved using solve_ivp, yielding smooth trajectories that consistently converge toward fixed points or attractors defined solely by the payoff matrix and initial conditions. These solutions capture the average, expected evolutionary outcome, emphasizing the dominant phenotypes and often leading to the extinction of rare types due to competitive exclusion. Consequently, deterministic dynamics tend to underrepresent the role of fluctuations that naturally arise in finite populations and complex microenvironments.

In contrast, stochastic dynamics, implemented via the Euler-Maruyama scheme, introduced a noise term proportional to , ensuring that population fractions remain bounded between zero and one while capturing random perturbations in phenotype frequencies. This stochastic framework reveals behavior not present in the deterministic solution. Small populations that would deterministically vanish can persist due to random excursions, and transitions between attractors can occur as noise temporarily pushes the system across basins of attraction. The resulting trajectories exhibit fluctuations around deterministic paths, occasional excursions toward different vertices of the simplex, and transient coexistence of multiple phenotypes. These phenomena highlight the capacity of stochasticity to maintain diversity, stabilize rare phenotypes, and generate noise-induced transitions that deterministic models fail to capture.

Visualization of the trajectories within the 3D simplex elucidates these differences clearly. Deterministic trajectories follow smooth, predictable paths toward fixed points, constrained by the topology of the payoff matrix. Stochastic trajectories, by contrast, explore a broader portion of the simplex, occasionally visiting edges or corners corresponding to extreme compositions. This demonstrates that even in the presence of strong selective pressures, random fluctuations can enable temporary or sustained polymorphic states, potentially influencing tumor evolution, therapeutic response, and emergent ecological interactions.

Overall, the integration of stochasticity into evolutionary game models underscores the importance of accounting for randomness in biological systems. While deterministic replicator dynamics provide foundational insight into fitness-driven competition and expected evolutionary outcomes, stochastic dynamics reveal the full spectrum of possible behaviors, including the persistence of minority phenotypes, transient dominance shifts, and emergent coexistence patterns. These results suggest that stochastic effects are not merely perturbations around a mean trajectory but can fundamentally alter evolutionary trajectories, offering a more nuanced understanding of tumor heterogeneity and the evolutionary forces shaping complex biological populations.

7. Case Study: Environmental Modulation of Tumor Dynamics

7.1. Comparative Framework

To understand how environmental acidity alters the evolutionary behavior of tumor cell populations, we consider two modified ecological scenarios derived from the baseline balanced competition model presented previously. In the baseline deterministic study, all four phenotypes—proliferative (P), invasive (I), resistant (R), and cooperative (C)—interact under near-neutral environmental conditions. The associated payoff matrix

A (

5) encodes the relative reproductive success obtained through pairwise interactions, where diagonal terms represent the intrinsic fitness of each phenotype and off-diagonal terms capture cross-interactions. This structure produces a dynamic equilibrium in which no phenotype achieves complete dominance: proliferative cells maintain a moderate advantage due to their intrinsic growth rate, while invasive and resistant phenotypes persist through niche exploitation, and cooperative phenotypes gradually diminish due to the absence of strong collective benefits.

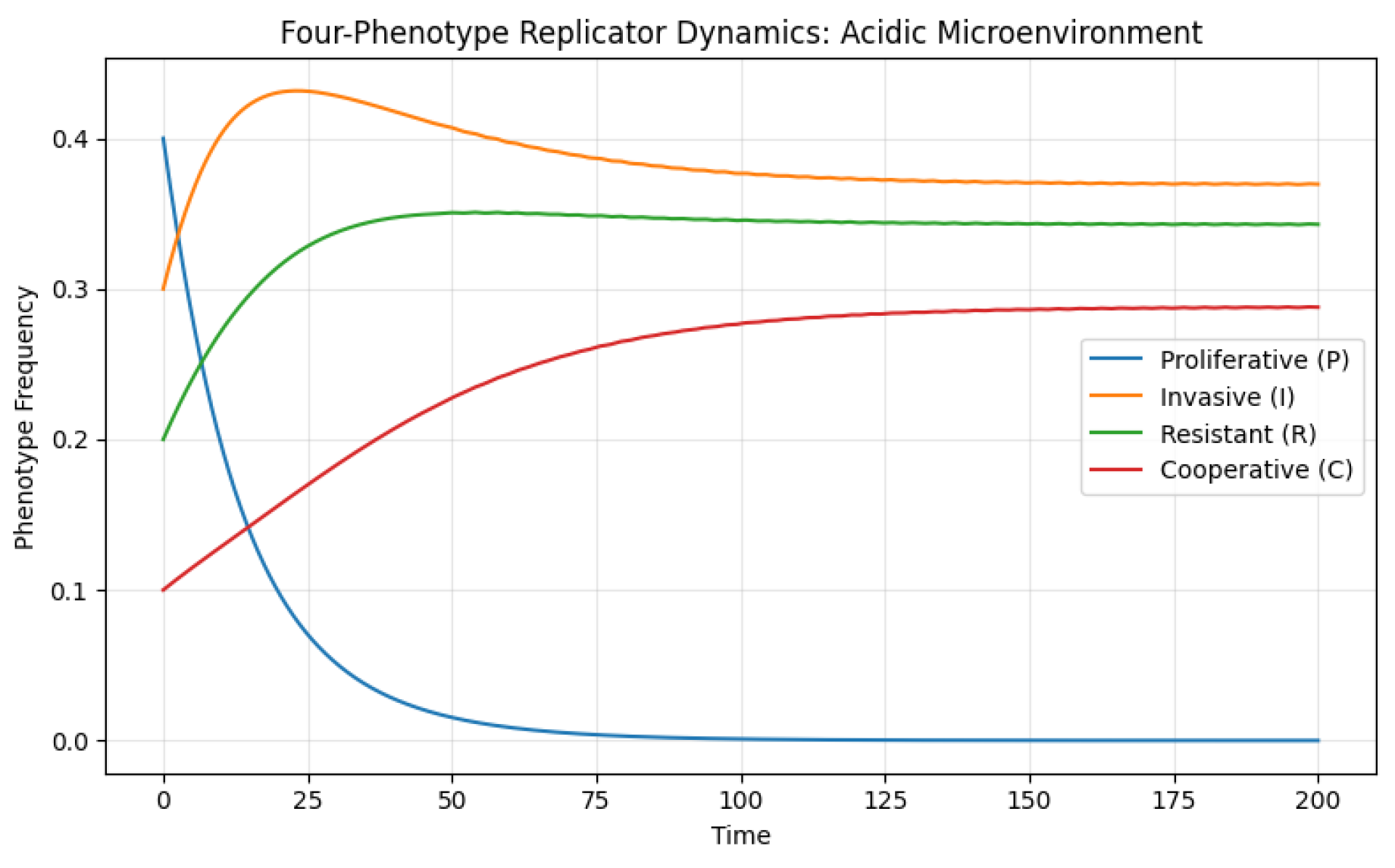

7.2. Acidic Microenvironment

In the acidic microenvironment scenario, the payoff matrix

was modified to reflect the metabolic and ecological advantages of phenotypes capable of thriving in low-pH conditions. These payoff modifications are phenomenological and do not correspond to a mechanistic or biochemical pH model. Mathematically, this modification increases the interaction coefficients associated with the invasive and resistant phenotypes, particularly in their interactions with proliferative and cooperative types:

Compared with

A (

5), the acidic matrix increases the fitness payoff for invasive and resistant phenotypes when interacting with others, capturing the biological reality that acidosis promotes motility, resistance to stress, and metabolic plasticity.

Simulations using this matrix

Figure 5 demonstrate a marked shift in population composition. Proliferative cells, which depend on a neutral or nutrient-rich environment, rapidly decline as acidity impairs their growth and energy metabolism. In contrast, invasive and resistant cells expand, eventually dominating the population. Cooperative phenotypes experience transient support but are ultimately suppressed as the harsh microenvironment undermines the benefit of mutualistic interactions. The overall outcome represents an ecologically aggressive tumor ecosystem characterized by phenotypic heterogeneity driven by stress adaptation. This aligns with empirical findings in tumor biology showing that acidosis promotes invasion, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, and resistance to therapy.

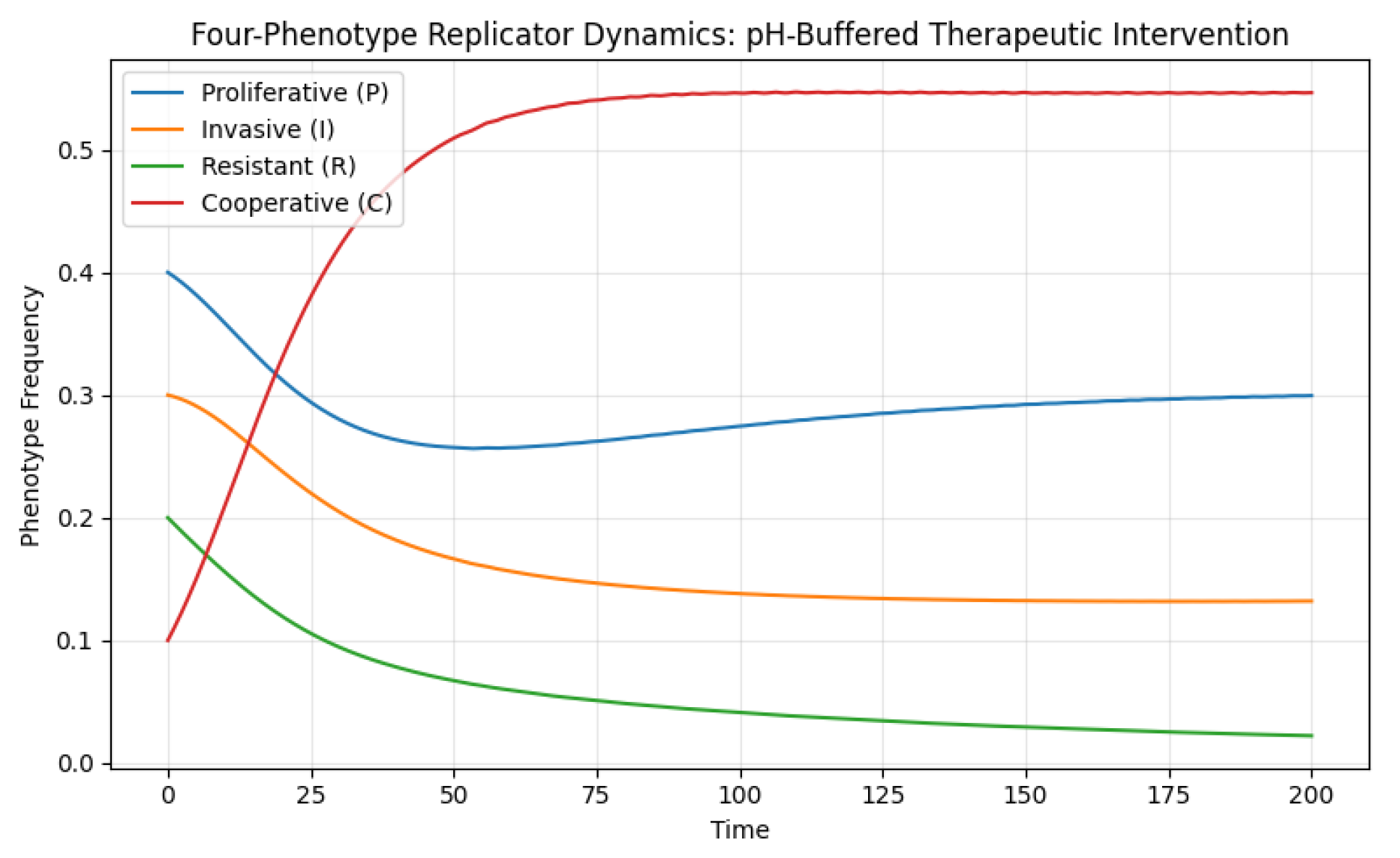

7.3. pH-Buffered Therapeutic Intervention

To explore whether modifying the environment can counteract this aggressive shift, a third matrix,

, was constructed to represent a therapeutically buffered microenvironment. This configuration restores a near-neutral pH, thereby diminishing the selective advantage of invasive and resistant phenotypes:

Here, the fitness advantages previously conferred to invasive and resistant phenotypes are reduced, while proliferative and cooperative phenotypes regain relative stability. The off-diagonal terms for the invasive and resistant rows decrease slightly, reflecting a weakening of their ecological competitiveness under normalized pH.

The resulting dynamics

Figure 6 contrast sharply with the acidic scenario. Proliferative cells, relieved from acidity-induced metabolic suppression, recover dominance and sustain a high steady-state frequency. Cooperative cells also show improved persistence, suggesting that a more benign environment can sustain mutualistic or resource-sharing strategies. Invasive and resistant cells, lacking their previous environmental advantage, decline significantly. These results should be interpreted as conceptual evidence that environmental modulation may redirect evolutionary trajectories, without implying direct clinical applicability.

7.4. Interpretation and Implications

By comparing these two altered matrices against the baseline deterministic case, the analysis reveals that environmental acidity functions as a key control parameter in the evolutionary game governing tumor composition. The payoff matrix serves as a compact representation of how ecological context reshapes selection gradients: increasing or decreasing specific entries effectively tunes the strength of competitive or cooperative interactions among phenotypes.

Under acidic conditions, matrix asymmetry favors phenotypes that exploit stress tolerance and mobility, leading to an adaptive landscape biased toward invasion and resistance. Therapeutic buffering, on the other hand, restores a more symmetric matrix, reducing these biases and encouraging coexistence dominated by proliferative and cooperative types. These results demonstrate that microenvironmental modification can redirect tumor evolution through ecological feedback rather than direct cytotoxicity.

From an evolutionary game theory perspective, this case study illustrates how even subtle adjustments to payoff parameters—representing metabolic or pH changes—can produce qualitatively distinct population trajectories. From a clinical standpoint, it supports the notion that interventions targeting the tumor microenvironment, such as systemic pH buffering, can complement conventional therapies by altering the selective pressures that drive malignancy and treatment resistance.

8. Conclusions

Cancer is fundamentally an evolving ecosystem shaped by dynamic interactions among genetically and phenotypically diverse cell populations within a heterogeneous microenvironment. By integrating evolutionary game theory with stochastic modeling, this study illustrates, within an applied evolutionary game-theoretic framework, how frequency-dependent selection, ecological feedbacks, and random fluctuations collectively govern tumor evolution. Distinct phenotypic strategies, proliferative, invasive, resistant, and cooperative, emerge and coexist through a balance of competitive and cooperative interactions, producing complex adaptive dynamics that deterministic models alone cannot fully capture. Stochasticity maintains rare yet clinically relevant phenotypes and enables transitions between metastable states, reflecting the inherently probabilistic nature of tumor progression.

Overall, this work reinforces the view of cancer as an adaptive ecological system whose evolutionary dynamics are shaped by strategy diversity, stochasticity, and environmental feedbacks. By extending evolutionary game theory to higher-dimensional phenotype interactions, the model provides a flexible conceptual framework for studying how microenvironmental manipulation may influence long-term evolutionary outcomes. Future work would be required to establish mathematically rigorous stochastic formulations on the simplex and to relate payoff structures to quantitative experimental measurements.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially sponsored with national funds through the Fundação Nacional para a Ciência e Tecnologia, Portugal-FCT, under projects UID/4674/2025 (CIMA).

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Replicator Equation Derivations, Simplified Forms, and Stability Calculations

Appendix A.1. Notation and Basic Replicator Equation

Let

denote the phenotype frequencies with

and

. Let the payoff matrix be

as defined in Eq. (4) of the main text. The expected fitness vector and mean fitness are

The deterministic replicator equation used in the manuscript (Eq. (3)) is

This form conserves total mass since .

Appendix A.2. Derivation of the One-Dimensional Reduction

If the dynamics reduce to two effective strategies with frequency

x (strategy 1) and

(strategy 2), and the pairwise payoff matrix is

then the expected fitnesses are

and the mean fitness is

Compute the replicator equation for

x:

Substituting

gives

Fixed points satisfy

and therefore

The interior fixed point

(if it lies in

) is

provided

and

.

Appendix A.3. Mapping the Two-Strategy Reduction to the Four-Phenotype Model

To apply the reduction above to the four-phenotype game, restrict to an invariant face of the simplex (for example when two phenotypes are absent). Set for the absent phenotypes and extract the corresponding submatrix of A. Use the submatrix entries to identify and apply the formula for above.

Example.

Suppose phenotypes

P and

I remain and

. Extract

Then set

,

,

,

and compute

Appendix A.4. Three-Strategy Interior Equilibrium

If three phenotypes

are present with frequencies

, the replicator system is

with

. An interior equilibrium

satisfies

so all three components of

are equal to the same scalar

. Thus we seek

satisfying

subject to

and

. Subtracting rows to eliminate

yields a

linear system for two variables; solve for those variables and enforce normalization to obtain the third. Explicitly showing these algebraic steps clarifies how the simplified forms in the main text are obtained.

Appendix A.5. Jacobian and Linear Stability

The flow

can be linearized at an equilibrium

. The Jacobian matrix

J of the full system has entries

A convenient expression (Hofbauer & Sigmund, 1998) is

At an interior equilibrium

, so

Because

(mass conservation), the Jacobian has one zero eigenvalue; stability must be assessed on the tangent space of the simplex. The equilibrium is locally asymptotically stable if all eigenvalues of the reduced Jacobian have negative real parts.

Two-strategy case.

For the two-strategy reduction, the derivative at the interior equilibrium

is

Hence the equilibrium is stable if

.

Appendix A.6. How to Reproduce the Algebra for the Manuscript’s Equations

- 1.

Identify the equation numbers in the manuscript corresponding to simplified replicator forms (e.g., Eqs. (6), (13), (18)).

- 2.

For each, determine which phenotypes are active and extract the appropriate or submatrix of A.

- 3.

Substitute the submatrix entries into the formulas in Sections A.2–A.4.

Example substitution.

If

,

,

, and

, then

so

. The derivative at equilibrium is

indicating local asymptotic stability on that edge.

Appendix A.7. Stochastic Extension

The stochastic formulation presented here is heuristic and intended to complement, rather than replace, rigorously derived population-genetic stochastic models. The stochastic replicator dynamics used in the manuscript are

and the associated Fokker–Planck equation for the probability density

is given in Eq. (8) of the main text. For small noise amplitudes, the stationary distribution concentrates near deterministic fixed points, and the covariance around an equilibrium can be approximated by solving the Lyapunov equation for the linearized Itô system.

This appendix provides the algebraic details for the simplified forms and equilibria referenced in the main text, ensuring full reproducibility of all analytical steps.

References

- Maynard Smith, J.; Price, G.R. The logic of animal conflict. Nature 1973, 246, 15–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardin, G. The Tragedy of the Commons. Science 1968, 162, 1243–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.A. Five rules for the evolution of cooperation. Science 2006, 314, 1560–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrett, A.M.; Lima, E.A.B.F.; Hormuth, D.A.; McKenna, M.T.; Feng, X.; Ekrut, D.A.; Yankeelov, T.E. Mathematical models of tumor cell proliferation: A review of the literature. Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy 2018, 18, 1271–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Neumann, J.; Morgenstern, O. Theory of Games and Economic Behavior; Princeton University Press, 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Basanta, D.; Anderson, A.R.A. Exploiting ecological principles to better understand cancer progression and treatment. Interface Focus 2013, 3, 20130020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archetti, M. Evolutionary game theory of growth factor production: implications for tumor heterogeneity and resistance to therapies. British Journal of Cancer 2013, 109, 1056–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatenby, R.A.; Vincent, T.L. An evolutionary model of carcinogenesis. Cancer Research 2003, 63, 6212–6220. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson, I.P.M.; Bodmer, W.F. Modelling the consequences of interactions between tumour cells. British Journal of Cancer 1997, 75, 157–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M.A.; Sigmund, K. Evolutionary dynamics of biological games. Science 2004, 303, 793–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McFarland, C.D.; Mirny, L.A.; Korolev, K.S. Tug-of-war between driver and passenger mutations in cancer and other adaptive processes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111, 15138–15143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archetti, M.; Ferraro, D.A.; Christofori, G. Heterogeneity for IGF-II production maintained by public goods dynamics in neuroendocrine pancreatic cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2015, 112, 1833–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingli, D.; Chalub, F.A.C.C.; Santos, F.C.; Van Segbroeck, S.; Pacheco, J.M. Cancer phenotype as the outcome of an evolutionary game between normal and malignant cells. British Journal of Cancer 2009, 101, 1130–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basanta, D.; Hatzikirou, H.; Deutsch, A. Studying the emergence of invasiveness in tumours using game theory. European Physical Journal B 2008, 63, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlando, P.A.; Gatenby, R.A.; Brown, J.S. Cancer treatment as a game: integrating evolutionary game theory into the optimal control of chemotherapy. Physical Biology 2012, 9, 065007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marusyk, A.; Almendro, V.; Polyak, K. Intra-tumour heterogeneity: a looking glass for cancer? Nature Reviews Cancer 2012, 12, 323–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dagogo-Jack, I.; Shaw, A.T. Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 2018, 15, 81–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greaves, M.; Maley, C.C. Clonal evolution in cancer. Nature 2012, 481, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, P.C. The clonal evolution of tumor cell populations. Science 1976, 194, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archetti, M. Cooperation among cancer cells: applying game theory to tumour metabolism. Nature Reviews Cancer 2015, 15, 558–566. [Google Scholar]

- Bach, L.A.; Bentzen, S.M.; Alsner, J.; Christiansen, F.B. An evolutionary-game model of tumour-cell interactions: possible relevance to gene therapy. European Journal of Cancer 2001, 37, 2116–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatenby, R.A.; Brown, J.; Vincent, T. Lessons from Applied Ecology: Cancer Control Using an Evolutionary Double Bind. Cancer Research 2009, 69, 7499–7502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallaher, J.A.; Enriquez-Navas, P.M.; Luddy, K.A.; Gatenby, R.A.; Anderson, A.R.A. Spatial heterogeneity and evolutionary dynamics modulate time to recurrence in continuous and adaptive cancer therapies. Cancer Research 2018, 78, 2127–2139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michor, F.; Iwasa, Y.; Nowak, M.A. Dynamics of cancer progression. Nature Reviews Cancer 2004, 4, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waclaw, B.; Bozic, I.; Pittman, M.E.; Hruban, R.H.; Vogelstein, B.; Nowak, M.A. A spatial model predicts that dispersal and cell turnover limit intratumour heterogeneity. Nature 2015, 525, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, A.R.A.; Weaver, A.M.; Cummings, P.T.; Quaranta, V. Tumor morphology and phenotypic evolution driven by selective pressure from the microenvironment. Cell 2006, 127, 905–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of cancer: new dimensions. Cancer Discovery 2022, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kareva, I. Prisoner’s Dilemma in Cancer Metabolism. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e28576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerlee, P.; Anderson, A.R.A. The evolution of carrying capacity in constrained and expanding tumour cell populations. PLoS Computational Biology 2015, 11, e1004359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofbauer, J.; Sigmund, K. Evolutionary Games and Population Dynamics; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Szabó, G.; Fáth, G. Evolutionary games on graphs. Physics Reports 2007, 446, 97–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archetti, M.; Pienta, K.J. Cooperation among cancer cells: applying game theory to cancer. Nature Reviews Cancer 2019, 19, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, J.A. Stochastic Graph-Based Models of Tumor Growth and Cellular Interactions. AppliedMath 2025, 5, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ao, P. Potential in stochastic differential equations: novel construction. Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and General 2004, 37, L25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brock, A.; Chang, H.; Huang, S. Non-genetic heterogeneity—a mutation-independent driving force for cancer cell plasticity and drug resistance. Nature Reviews Genetics 2009, 10, 336–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, P.B.; et al. Stochastic state transitions give rise to phenotypic equilibrium in populations of cancer cells. Cell 2011, 146, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaznatcheev, A.; et al. Cancer treatment scheduling and dynamic heterogeneity in social dilemmas of tumor acidity and vasculature. Nature Ecology & Evolution 2019, 3, 460–468. [Google Scholar]

- Archetti, M.; Pienta, K.J. Cooperation among cancer cells: applying game theory to cancer. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2019, 374, 20180145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).