1. Introduction

Understanding the evolution of cellular populations over time is crucial to comprehending various biological processes, particularly in the context of cancer biology. The tumor microenvironment (TME) plays a pivotal role in shaping the behavior of tumor cells, including their growth, invasion, and response to therapies [

1,

2]. Traditional models of tumor growth, such as the logistic growth equation, offer a foundational framework for describing how tumor populations expand by considering intrinsic growth limitations [

3]. However, the TME is subject to various dynamic and unpredictable factors, such as immune responses, nutrient availability, and the presence of therapeutic interventions [

1]. These factors introduce substantial randomness that purely deterministic models fail to capture, making it necessary to use stochastic models to provide a more accurate representation of tumor evolution [

4].

This study investigates a stochastic tumor growth model that extends the classical logistic equation by incorporating an additional decay term and stochasticity through a Gaussian white noise process [

5]. The model not only accounts for the bounded growth of tumor cells but also introduces mechanisms that describe external pressures from the TME, such as immune attacks, hypoxia, and chemotherapy, which can lead to tumor decline or remission [

6]. Furthermore, the stochastic component models the unpredictable variations resulting from the TME’s environmental and therapeutic uncertainties, thus offering a more flexible and realistic description of tumor growth and adaptation [

7].

To analyze this stochastic model, we employ numerical approximation techniques, with a focus on the Euler-Maruyama method [

8], which is widely used for solving stochastic differential equations (SDEs) in computational cancer modeling. Additionally, we extend our analysis by incorporating a dynamic graph evolution framework, where tumor cells are represented as nodes in a network that evolves over time. This approach captures the changing interactions and relationships within the TME, reflecting how tumor cells, immune cells, and other stromal components communicate and influence each other over the course of tumor progression [

9]. By adopting this graph-based perspective, we gain insights into how tumors adapt to their ever-changing microenvironment and how these changes impact treatment responses.

By integrating stochastic modeling with dynamic graph evolution, this work offers a more nuanced and adaptable approach to understanding tumor dynamics. The results provide deeper insights into how tumor populations evolve under uncertainty, interact within a complex microenvironment, and adapt to changing conditions, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of cancer progression and therapeutic challenges.

In this paper, we present a detailed study on the population dynamics of tumor growth, incorporating both deterministic and stochastic components to explore the underlying mechanisms governing cell behavior in the TME. We start by discussing the deterministic component of the model in

Section 2, where we outline the mathematical formulation of cell population growth based on deterministic differential equations. This section establishes the baseline dynamics of tumor growth under controlled conditions, where random fluctuations are not considered.

Next, in

Section 3, we introduce the stochastic elements that reflect the inherent randomness of cellular processes in the TME. These fluctuations arise from various factors, such as random mutations, interactions between different cell types, and the influence of external factors. We explore how incorporating stochasticity alters the model’s predictions and offers a more realistic representation of tumor progression.

In

Section 4, we combine both the deterministic and stochastic components into a unified model. This section provides an interpretation of the interactions between these components, and how they together shape the overall dynamics of tumor growth. By including both aspects, we aim to develop a comprehensive framework for understanding the complexity of tumor evolution.

The implications of stochasticity are explored further in

Section 5. Here, we discuss how randomness impacts tumor behavior, leading to variability in tumor progression, treatment responses, and the potential for metastasis. Stochastic models offer insight into the unpredictable nature of tumor dynamics, which is critical for improving treatment strategies.

Numerical methods are then employed to solve the model, as detailed in

Section 6. We present the Euler-Maruyama method for discretizing the stochastic differential equations and discuss the accuracy and efficiency of this approach in capturing the key dynamics of the tumor system.

In

Section 7, we introduce a graph-based approach to model the interactions between cells within the TME. This representation allows us to capture the spatial and topological structure of the tumor, which plays a significant role in its growth and resistance to therapies.

The evolution of the tumor network is further explored in

Section 8, where we investigate how the structure of the tumor’s cellular network evolves over time. We analyze the factors that influence network connectivity and discuss how these dynamics affect tumor behavior.

In

Section 9, we focus on the algebraic connectivity of the tumor network, which measures the network’s robustness and potential for connectivity-driven processes, such as metastasis. This section provides mathematical tools to analyze and quantify the network’s resilience to perturbations.

The paper concludes with a discussion in

Section 10, where we interpret the results from our model, evaluate the significance of the findings, and explore the broader implications for cancer research. We conclude with a summary of the key insights gained from our study and outline potential avenues for future work in

Section 11.

By combining deterministic and stochastic models with graph-based network approaches, we aim to provide a deeper understanding of the tumor microenvironment and its role in shaping tumor progression. This framework opens up new possibilities for personalized cancer therapies and better predictive models of tumor behavior.

2. Deterministic Component in Population Dynamics

The deterministic component of population dynamics describes how a population evolves over time under predictable biological and environmental conditions. A widely used mathematical formulation for this is [

10]:

where:

represents the population size at time t,

is the intrinsic growth rate, which dictates the population’s natural tendency to grow under favorable conditions,

is the primary carrying capacity, the maximum population size that the environment can support sustainably,

represents a decay rate, which accounts for population reduction due to external factors such as competition, predation, or environmental stress,

is an alternative carrying capacity, which influences the decay term.

2.1. Logistic Growth

The first term,

, follows the logistic growth model introduced by Verhulst (1838) [

3]. This model describes how population growth slows down as it approaches the carrying capacity

K. Initially, when resources are abundant, growth is nearly exponential, but as the population nears

K, limited resources and other density-dependent factors cause growth to decelerate.

2.2. Decay Mechanism

The second term,

, represents population reduction driven by environmental constraints or overpopulation effects. Unlike standard logistic models, this term introduces an additional threshold,

, which represents an alternative carrying capacity where decay effects become significant. If

, the population may experience earlier reductions due to resource depletion, disease spread, or stress-induced mortality [

11,

12].

2.3. Classical Logistic Growth ()

When

, the equation reduces to the standard logistic equation:

This results in an S-shaped (sigmoidal) population trajectory where growth slows and stabilizes at

K [

13].

2.4. Regulated Growth with Decay ()

When , decay introduces an additional control mechanism. This could model:

Overpopulation effects leading to increased mortality (e.g., Allee effects, disease outbreaks, or food shortages) [

14].

Population decline due to external pressures such as habitat destruction or increased predation [

15].

Regulation through self-thinning in plant or microbial populations [

16].

3. Stochastic Component in Population Dynamics

In real-world ecological and biological systems, population dynamics are influenced by various environmental factors that introduce uncertainty. Deterministic models often fail to capture the inherent randomness present in nature. To address this, stochastic models incorporate random fluctuations, allowing for more realistic representations of population behaviors [

17,

18].

To model population dynamics with stochasticity, we introduce a noise term into the deterministic equation:

where:

N is the population size,

represents the intrinsic growth rate,

K is the carrying capacity of the environment,

is a parameter describing competitive effects,

accounts for alternative carrying capacities,

is the noise intensity, controlling the magnitude of random fluctuations,

is Gaussian white noise with the properties:

where

is the Dirac delta function, ensuring the noise is uncorrelated over time [

4].

3.1. Interpretation of Stochastic Effects

The term introduces random perturbations into population growth, making the system inherently probabilistic. These fluctuations represent external environmental influences such as:

Variations in food availability [

19],

Climatic changes (e.g., droughts or floods) [

15],

Predation pressures [

12].

Unlike deterministic models, which predict a fixed trajectory for population size, stochastic models allow for variability in outcomes. This better reflects real ecosystems, where unpredictable events impact population dynamics [

21].

3.2. Implications of Stochasticity

Extinction Risk: Even if a population is stable in a deterministic model, stochastic fluctuations can drive it to extinction [

17].

Population Resilience: A species’ ability to recover from disturbances can be analyzed through the noise intensity

[

22].

Bifurcations and Critical Transitions: Stochasticity can induce shifts between stable states, leading to sudden changes in population size [

23].

4. Interpretation of the Full Model

The full stochastic differential equation (SDE) can be written in standard form as:

where

represents the increment of a Wiener process (also known as Brownian motion). The Wiener process

has the properties:

Thus, the population dynamics are driven by two components:

A deterministic drift term that governs the average behavior of the population,

A stochastic diffusion term that introduces variability around this average.

The deterministic drift term represents the fundamental growth and competition processes in the population, shaping its long-term trends. The stochastic diffusion term accounts for random environmental fluctuations, leading to deviations from the deterministic trajectory.

The presence of noise () in the model can have significant implications, such as:

Increased Extinction Risk: Small populations are particularly vulnerable to random fluctuations, which can lead to extinction even when the deterministic model predicts persistence.

Stochastic Stabilization: In some cases, noise can stabilize an otherwise unstable system by preventing deterministic collapse.

Regime Shifts: Sufficiently strong stochastic fluctuations can push the population between different equilibrium states, leading to abrupt ecological transitions.

Understanding these stochastic effects is crucial for making reliable predictions about population persistence and management in changing environments.

5. Implications of Stochasticity

Stochasticity plays a crucial role in shaping population dynamics, often introducing variability that deterministic models fail to capture. One of its most significant consequences is the increased risk of extinction. Even if a population appears stable under deterministic conditions, random fluctuations in birth rates, death rates, or environmental factors can lead to a gradual decline or sudden collapse, ultimately driving the population to extinction. This phenomenon is particularly relevant for small populations, where random demographic variations can have a disproportionately large impact.

Another important aspect of stochasticity is its effect on population resilience. The ability of a species to recover from disturbances, such as environmental shocks or resource fluctuations, depends on the intensity of stochastic noise, denoted by . Higher noise levels can either enhance adaptability by allowing populations to explore alternative states or push them toward extinction if fluctuations become too extreme. Understanding these effects is essential for conservation biology and ecosystem management, as it helps predict how species respond to environmental changes.

Additionally, stochasticity can induce bifurcations and critical transitions, leading to sudden and unpredictable shifts between stable states. In deterministic models, populations typically remain in equilibrium unless external factors cause a transition. However, in stochastic environments, random fluctuations can push populations past critical thresholds, triggering abrupt changes in size or distribution. Such transitions can result in regime shifts, where ecosystems move from one stable state to another, sometimes with irreversible consequences. These stochastic-induced shifts are particularly relevant in climate change studies, where small perturbations can lead to drastic ecosystem transformations.

Overall, incorporating stochasticity into population models provides a more realistic and nuanced understanding of ecological dynamics. By considering extinction risk, resilience, and the potential for critical transitions, researchers can better predict long-term population trends and develop more effective conservation strategies.

6. Numerical Discretization Using the Euler-Maruyama Method

The Euler-Maruyama method is a straightforward and effective technique for numerically solving SDEs. It approximates the solution over small time steps .

To obtain the discretization for the stochastic equation (

5), we, first, consider a discrete set of time points

with a small step size

, such that:

Using the Euler-Maruyama method, we approximate the solution at each time step by discretizing both the drift term (deterministic part) and diffusion term (stochastic part).

The general Euler-Maruyama approximation for an SDE of the form:

is given by:

where:

is the drift term (deterministic growth part),

is the diffusion term (stochastic noise),

represents the Wiener process increment, which satisfies:

This means

is normally distributed with mean 0 and variance

, so we can write:

Next, we identify the drift and diffusion terms:

Applying the Euler-Maruyama method, we obtain:

Since

with

, we substitute:

Since population cannot be negative, we enforce:

Thus, (

15) is the discrete-time update equation for

.

This ensures that the population remains non-negative while incorporating both deterministic growth and stochastic fluctuations.

The population at the next time step depends on the current population , the deterministic drift term, and the stochastic diffusion term.

The drift term captures the deterministic growth and decay dynamics.

The diffusion term introduces randomness, where is a standard normal random variable.

The function ensures that the population N remains non-negative, as negative population values are biologically meaningless.

The Wiener process increment is approximated by , where is drawn from a standard normal distribution. This reflects the Gaussian nature of the noise.

7. Graph Evolution Model

Graph evolution models are crucial for studying the structural transformations of complex networks over time [

24,

25]. Classical models such as the Erdős–Rényi (ER) random graph [

26] and the Barabási–Albert (BA) preferential attachment model [

27] provide fundamental insights into random and preferentially growing networks, respectively. However, many real-world systems exhibit both stochastic attachment and structured evolution, necessitating models that integrate these mechanisms.

7.1. Proposed Graph Evolution Model

In this work, we introduce a Graph Evolution Model that incorporates both growth and rewiring dynamics. Unlike classical models, our approach integrates random attachment and incremental edge rewiring at fixed time intervals, allowing the network to evolve in a structured yet stochastic manner.

The model is initialized as an Erdős–Rényi graph , where and each edge exists with an independent probability . As the network evolves:

Every 10 time steps, a new node is introduced, connecting to three randomly selected existing nodes.

Every 5 time steps, a new edge is introduced between two randomly chosen existing nodes.

This process creates a dynamically growing network that exhibits properties distinct from purely random and preferential attachment models.

7.2. Visualization and Analysis

To analyze the evolution of the network, we visualize the graph at different time steps, scaling node sizes according to a function

, which represents how biological or external factors influence network growth. This model provides insight into stochastic growth patterns observed in various real-world networks, bridging randomness with structured expansion [

28].

In the following, we present a detailed description of this evolving graph model and explore its statistical properties. By incorporating both growth and rewiring dynamics, our model offers a more comprehensive representation of real-world networks, balancing stochastic processes with structured development.

We start with an Erdős–Rényi graph

, where:

is the initial number of nodes. Each edge between two nodes exists with an independent probability

Formally, the adjacency matrix

A is defined as:

for all pairs with .

A new node

is added. It connects to three randomly chosen existing nodes. Let

be the set of nodes at time

t, and

be the set of edges. At time

(for integer

k):

Three existing nodes

are randomly selected. New edges are added:

Two existing nodes are randomly selected and connected by a new edge. At time (for integer m, but not a multiple of 10):

8. Network Growth Dynamics

Understanding how a network evolves over time is crucial in modeling real-world systems such as social networks, communication infrastructures, and biological systems. This section describes the growth dynamics of the network, detailing how the number of nodes and edges changes over time.

8.1. Node Count

The total number of nodes in the network, denoted as

, increases over time following a discrete growth pattern. Specifically, a new node is added every 10 time steps. This process can be expressed mathematically as:

where the initial number of nodes is 20, and each additional node appears at integer multiples of 10 steps. This controlled node addition reflects a structured expansion of the network.

8.2. Edge Count

The network starts with an initial set of edges determined by the Erdős–Rényi random graph model. The number of initial edges,

, is drawn from a binomial distribution::

which means that each possible edge among the initial 20 nodes exists independently with a probability of

.

Two mechanisms contribute to the growth of edges over time:

Growth Rule: Every 10 steps, 3 new edges are added to the network.

Rewiring Rule: Every 5 steps, an additional edge is introduced through rewiring.

The total expected number of edges at time

t is given by:

By simplifying the equation, we obtain:

This expression indicates that the number of edges grows linearly over time, with an expected rate of edges per time step, in addition to the initial edges. This dynamic represents a network that expands in a structured manner while allowing for incremental connectivity changes.

8.3. Comparison with Preferential Attachment

A key distinction between this model and the well-known Barabási–Albert preferential attachment model lies in the method by which new edges are introduced. The Barabási–Albert model follows a mechanism where new nodes are more likely to connect to existing high-degree nodes, reinforcing a "rich-get-richer" effect. This results in a scale-free degree distribution, where a few nodes acquire a disproportionately high number of connections.

In contrast, the growth model described in this paper does not employ preferential attachment. Instead, new edges are added by selecting existing nodes uniformly at random. This uniform selection process implies that every node has an equal probability of receiving a new connection, regardless of its current degree. Consequently, the network does not inherently favor high-degree nodes, leading to a more homogeneous growth pattern.

However, despite the lack of explicit preferential attachment, degree heterogeneity may still emerge over time. Nodes that have existed in the network for longer periods have had more opportunities to accumulate edges, leading to natural variations in node degrees. This incremental growth effect can contribute to a degree distribution that is broader than a purely random Erdős–Rényi graph but less skewed than a scale-free network.

Further analysis, such as measuring the degree distribution over time, could provide insights into whether the network develops characteristics similar to preferential attachment models or retains a more uniform structure. This comparison helps highlight the role of different edge allocation strategies in shaping network topology.

9. Algebraic Connectivity Computation

Understanding the structural evolution of dynamic networks is fundamental in various several biological. In the context of this study, the evolving graph represents a growing system where new nodes and edges are continuously added over time. The connectivity properties of such a network are crucial in determining its resilience, efficiency of information flow, and overall robustness.

Algebraic connectivity, defined as the second smallest eigenvalue of the graph Laplacian, serves as a key measure of these properties, capturing the ability of the network to remain connected despite structural changes. The graph Laplacian matrix

L is defined as:

where

D is the degree matrix, a diagonal matrix where each entry represents the degree of a corresponding vertex, and

A is the adjacency matrix, defined by (

18).

As demonstrated in previous work [

29], algebraic connectivity provides valuable insights into the topological properties of complex networks, particularly in biological and interaction-based systems. In protein-protein interaction networks, for instance, this measure helps assess functional organization and robustness against perturbations. Inspired by this approach, we apply algebraic connectivity analysis to our dynamic network model to quantify the structural changes induced by stochastic population growth and random network evolution.

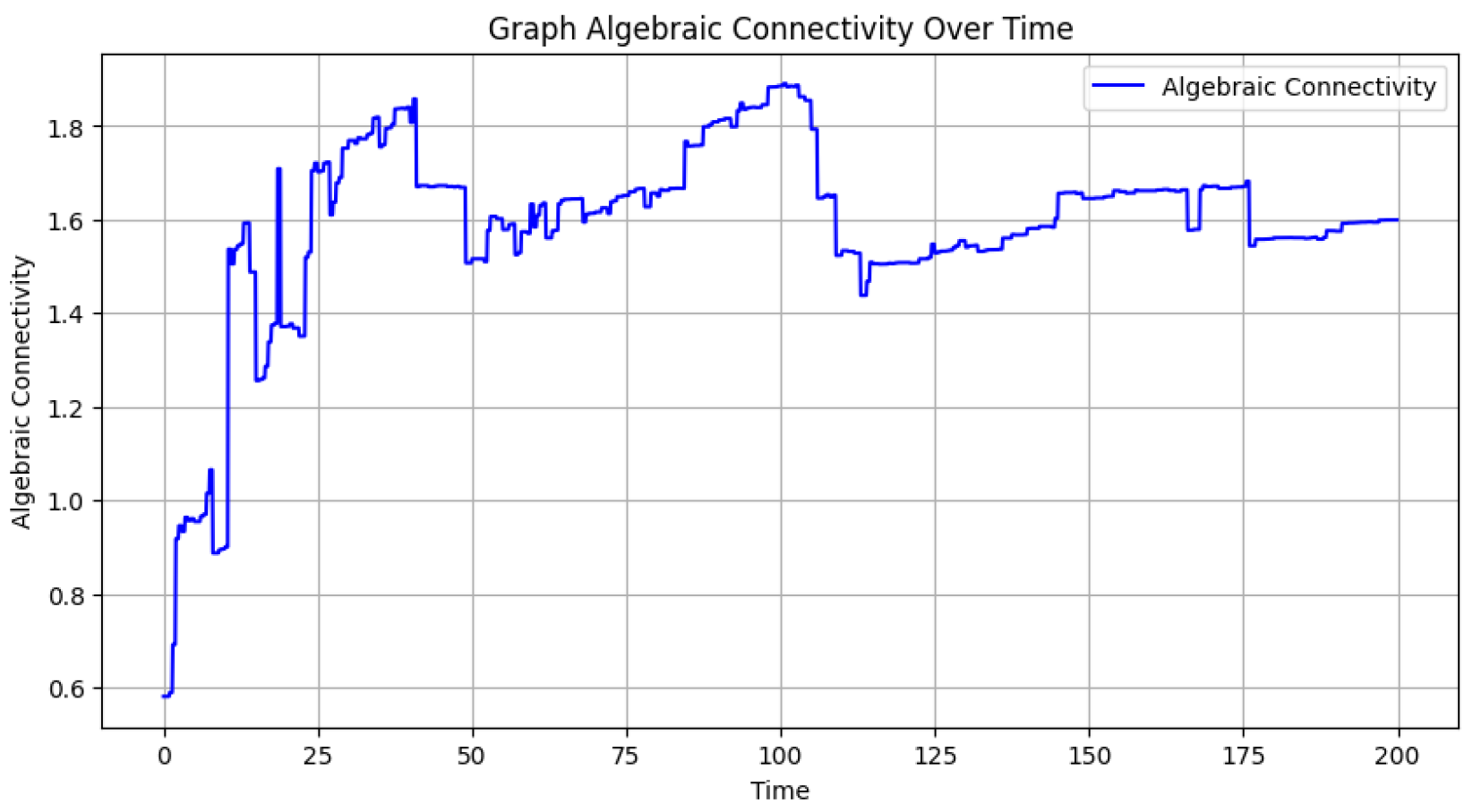

By computing algebraic connectivity at each time step, we aim to capture how the expansion of the network influences its structural cohesion. Since new nodes and edges are added periodically, the algebraic connectivity is expected to increase over time, reflecting improved network resilience. However, the stochastic nature of the graph evolution introduces fluctuations in connectivity, which can reveal critical transitions in the system’s structural development. This analysis not only aligns with theoretical perspectives from topological data analysis but also provides a quantitative measure to evaluate the impact of network growth on connectivity and robustness.

10. Discussion and Interpretation of Results

The results obtained from the simulation provide valuable insights into the evolution of both the tumoral cell population and the network’s structural properties over time.

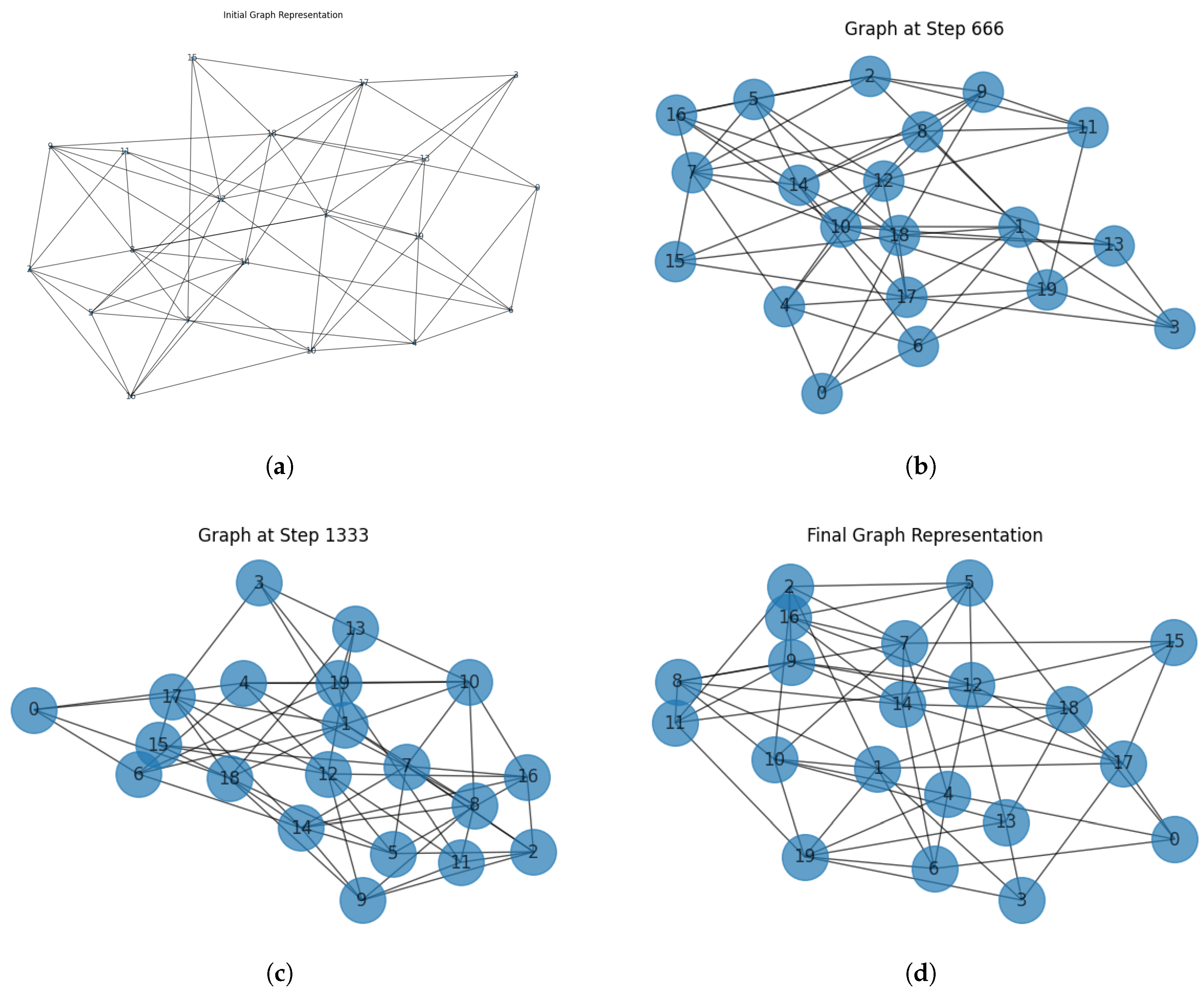

Figure 1 represents the evolution of the network, where the nodes and their connections dynamically change as new vertices and edges are introduced. The size of the circles around the vertices represents the relative population size at each time step, interpolated based on the minimum and maximum values observed. As time progresses, the growth process leads to an increase in node sizes, reflecting the increasing tumoral cell population. Additionally, new connections and nodes modify the network’s topology, making it more interconnected over time.

Figure 1 (a) represents the initial network configuration, where nodes are relatively sparse, and connections are randomly distributed. The (b) and (c) figures correspond to intermediate stages of network evolution. At these stages, new nodes have been integrated into the network, and additional edges have been introduced, leading to a more interconnected structure. The final figure (d) showcases the fully evolved network, where both node count and edge density have increased significantly. The node sizes in each figure are scaled based on the population values at the corresponding time steps, visually demonstrating the growth trend.

One of the key observations from the

Figure 1 is that while the network expands structurally, its overall connectivity follows a non-uniform pattern due to the randomness in node attachment. Certain nodes accumulate more connections than others, hinting at an implicit preferential attachment mechanism despite the random selection process. This results in a heterogeneous degree distribution, which is often observed in real-world networks.

Moreover, the influence of stochasticity in the population model is evident when examining the node size variations over time. Fluctuations in population size directly affect the graphical representation, emphasizing how uncertainties in biological growth can propagate into structural changes in the associated network. The presence of noise ensures that the system does not follow a strictly deterministic trajectory, making the results more representative of real-world complex systems.

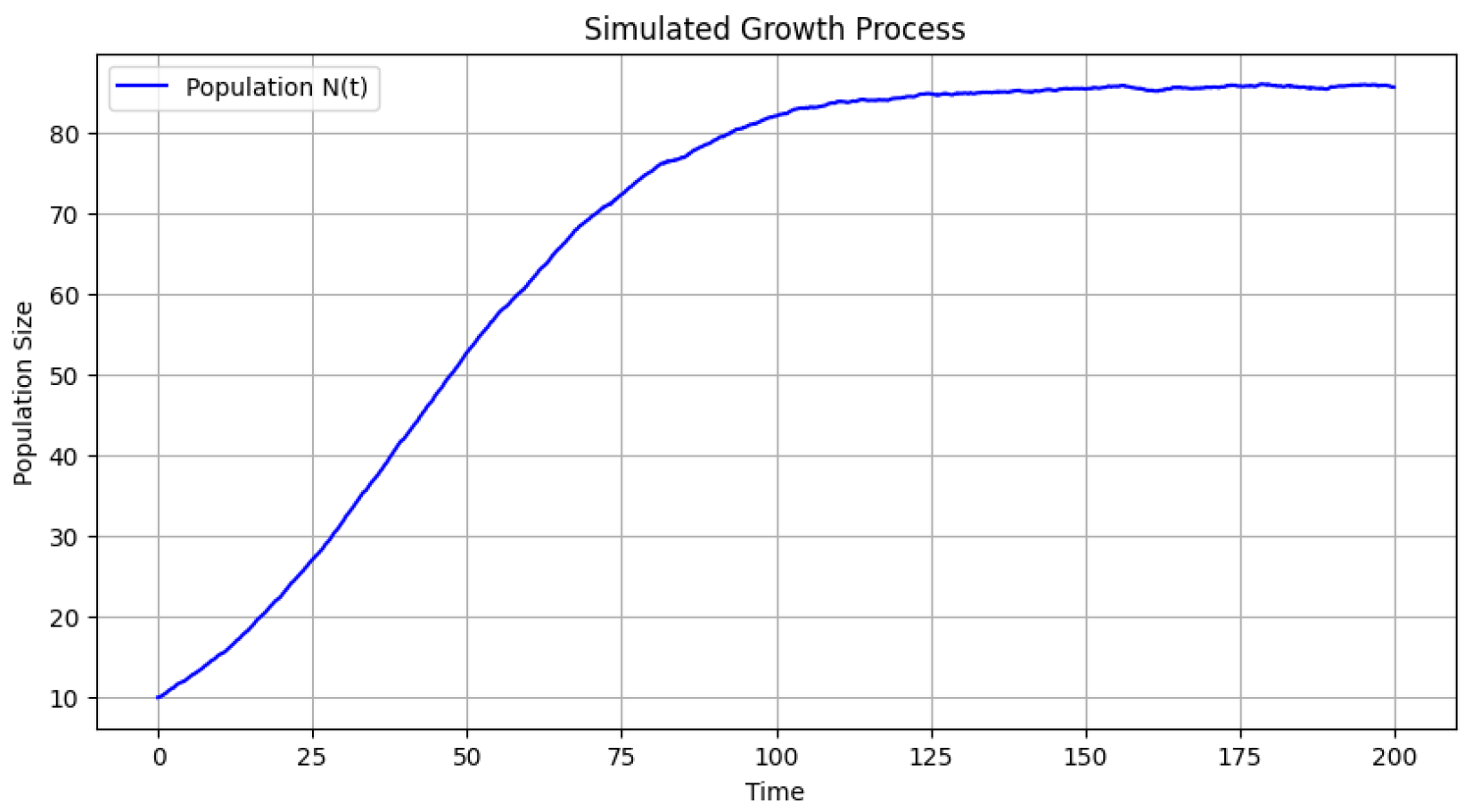

Figure 2 presents the evolution of the tumoral cell population over time. The stochastic nature of the Euler-Maruyama simulation introduces fluctuations, but overall, the population follows a growth trend influenced by carrying capacities and decay rates. The population size starts from an initial value and exhibits an increasing trajectory, with variability introduced by stochastic noise.

Finally,

Figure 3, which presents the algebraic connectivity values for each graph, illustrates the evolution of the graph’s structural cohesion. Algebraic connectivity, derived from the Laplacian matrix’s second smallest eigenvalue, quantifies the robustness of the network. Initially, with fewer nodes and edges, the connectivity is lower, but as new nodes and connections emerge, the graph becomes more integrated, often leading to an increase in connectivity. Fluctuations in the plot indicate structural changes, such as the addition of new nodes or edges, which can temporarily disrupt or strengthen the connectivity of the network.

Figure 2.

Tumoral Cell Population Evolution: The stochastic growth of the tumoral cell population over time, influenced by intrinsic growth constraints and external noise.

Figure 2.

Tumoral Cell Population Evolution: The stochastic growth of the tumoral cell population over time, influenced by intrinsic growth constraints and external noise.

Figure 3.

Algebraic Connectivity Over Time: The variation of algebraic connectivity throughout the simulation, illustrating how the network’s cohesion changes as new nodes and edges are added.

Figure 3.

Algebraic Connectivity Over Time: The variation of algebraic connectivity throughout the simulation, illustrating how the network’s cohesion changes as new nodes and edges are added.

The simulation results provide valuable insights into the dynamic relationship between stochastic population growth and evolving network topology. The population model follows a stochastic differential equation that incorporates both logistic growth and an additional decay term. The numerical solution obtained through the Euler-Maruyama method captures both deterministic trends and random fluctuations due to the Wiener process. The results demonstrate that while the population generally follows a logistic-like growth trajectory, it is significantly influenced by stochastic perturbations, which lead to irregular oscillations around the carrying capacity. The presence of an alternative carrying capacity introduces an additional regulatory mechanism, creating a complex interplay between growth and decay.

The evolution of the network reflects a dynamic process where structural changes occur at predefined intervals. The initial graph is generated using an Erdős–Rényi model with a connection probability of , resulting in a fairly random structure. As time progresses, new nodes are added every ten steps and connected to existing ones, while additional edges are formed between existing nodes every five steps. This leads to a gradual increase in network density and connectivity. The figures illustrate how the network expands over time, displaying an emergent structure that increasingly resembles real-world evolving systems, such as social networks or ecological food webs.

11. Conclusion and Future Work

In this study, we explored the interplay between stochastic population dynamics and the evolution of a growing network within the context of the tumor microenvironment. The population dynamics were modeled using a stochastic differential equation that incorporated tumor cell growth with logistic constraints, along with a secondary decay term and random fluctuations. The Euler-Maruyama method was employed to numerically approximate the solution, ensuring that the population (representing tumor cells) remained non-negative throughout the simulation. The results demonstrated that tumor cell populations fluctuate over time, influenced by the combined effects of deterministic growth, constraints imposed by the TME (such as nutrient limitations and immune responses), and stochastic noise.

Simultaneously, the network representing the tumor microenvironment evolved according to specific growth rules, where new cells or components (e.g., blood vessels, immune cells) were periodically introduced and connected to existing ones, while additional random interactions (e.g., tumor-stroma interactions or immune evasion mechanisms) were introduced at regular intervals. This process resulted in a dynamically expanding and changing network that exhibited characteristics of random growth models, such as preferential attachment-like behavior, despite the inherent randomness in cellular interactions. Visualizing the network at different stages revealed how its topology shifted over time, reflecting the impact of the evolving tumor population and the dynamic nature of the TME.

A key insight from this study is the connection between tumor population changes and structural adaptations in the tumor microenvironment. The mapping of tumor cell population size to node size in the network visualization highlighted how the biological process of tumor growth influenced the representation of the evolving TME. This could have significant implications for cancer research, particularly in understanding tumor evolution, metastasis, and treatment resistance, where the spatial and structural dynamics of the TME are crucial factors.

Future work could extend this model by incorporating more complex interaction rules, such as weighted edges based on the attributes of tumor and stromal cells, adaptive rewiring strategies (e.g., angiogenesis or immune evasion mechanisms), or feedback mechanisms between the network structure and tumor population dynamics. Additionally, exploring different types of noise, such as multiplicative stochasticity representing genetic mutations or environmental changes, could provide deeper insights into the stability and variability of the tumor microenvironment. These extensions could further enhance our understanding of cancer as a complex adaptive system, where stochastic processes and network evolution are inherently linked, offering new avenues for therapeutic interventions targeting tumor-host interactions.

Acknowledgments

This research was partially sponsored with national funds through the Fundação Nacional para a Ciência e Tecnologia, Portugal-FCT, under projects UIDB/04674/2020 (CIMA). DOI:

https://doi.org/10.54499/UIDB/04674/2020.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [CrossRef]

- Lodish, H.F.; Berk, A.; Kaiser, C.; Krieger, M.; Bretscher, A.; Ploegh, H.L.; Amon, A.; Martin, K.C. Molecular Cell Biology; W.H. Freeman-Macmillan Learning, 2016.

- Verhulst, P.F. Notice sur la loi que la population suit dans son accroissement. Correspondance Mathématique et Physique 1838, 10, 113–121.

- Gardiner, C.W. Stochastic Methods: A Handbook for the Natural and Social Sciences; Springer, 2009.

- Tuckwell, H.C. Introduction to Theoretical Neurobiology: Volume 2, Nonlinear and Stochastic Theories; Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Allen, L.J.S. An Introduction to Stochastic Processes with Applications to Biology; CRC Press, 2010.

- Lande, R.; Engen, S.; Sæther, B.E. Stochastic Population Dynamics in Ecology and Conservation; Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Kloeden, P.E.; Platen, E. Numerical Solution of Stochastic Differential Equations; Springer, 1992.

- Newman, M.E.J. Networks: An Introduction; Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Rodrigues, J.A. Using Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) for Tumor Cell Growth Modeling. Mathematics 2024, 12, 1195. [CrossRef]

- Tilman, D. Resource Competition and Community Structure; Princeton University Press, 1982.

- May, R.M. Simple mathematical models with very complicated dynamics. Nature 1976, 261, 459–467. [CrossRef]

- Murray, J.D. Mathematical Biology I: An Introduction; Springer, 2002.

- Courchamp, F.; Clutton-Brock, T.; Grenfell, B. Inverse density dependence and the Allee effect. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 1999, 14, 405–410. [CrossRef]

- Hanski, I. Metapopulation Ecology; Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Yoda, K.; Kira, T.; Ogawa, H.; Hozumi, K. Self-thinning in overcrowded pure stands under cultivated and natural conditions. Journal of Biology 1963, 14, 107–129.

- Lande, R. Risks of population extinction from demographic and environmental stochasticity and random catastrophes. American Naturalist 1993, 142, 911–927. [CrossRef]

- Nisbet, R.M.; Gurney, W.S.C. Modelling Fluctuating Populations; Wiley, 1982.

- Kutalik, Z.; Razaz, M.; Baranyi, J. Connection between stochastic and deterministic modelling of microbial growth. Journal of Theoretical Biology 2005, 232, 285–299. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.M.; May, R.M. Infectious Diseases of Humans: Dynamics and Control; Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Morris, W.F.; Doak, D.F. Quantitative Conservation Biology: Theory and Practice of Population Viability Analysis; Sinauer Associates, 2008.

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 1973, 4, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Scheffer, M.; et al. Catastrophic shifts in ecosystems. Nature 2001, 413, 591–596. [CrossRef]

- Albert, R.; Barabási, A.L. Statistical mechanics of complex networks. Reviews of modern physics 2002, 74, 47. [CrossRef]

- Newman, M.E. The structure and function of complex networks. SIAM review 2003, 45, 167–256.

- Erdős, P.; Rényi, A. On random graphs. Publicationes Mathematicae 1960, 6, 290–297.

- Barabási, A.L.; Albert, R. Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science 1999, 286, 509–512. [CrossRef]

- Dorogovtsev, S.N.; Mendes, J.F. Evolution of networks. Advances in physics 2002, 51, 1079–1187.

- Rodrigues, J.A. A Topological Approach to Protein-Protein Interaction Networks: Persistent Homology and Algebraic Connectivity. Preprints 2025. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).