Background

Financial crimes pose significant threats to the integrity and stability of the global financial system. These illicit activities not only undermine the trust and security within financial institutions but also have far-reaching implications for economies and societies at large. In the context of this study, financial crimes include - and are limited to - money laundering, fraud, and terrorism financing.

Money laundering is a sophisticated process that involves disguising the origins of illegally obtained funds, making them appear legitimate. Financial fraudsters and criminal organizations engage in money laundering to integrate illicit proceeds into the formal financial system, making detection challenging. Traditional methods of combating money laundering have proven insufficient, highlighting the need for innovative approaches to identify and prevent such activities.

Financial fraud encompasses a broad range of deceptive practices, including identity theft, credit card fraud, and embezzlement. The digital age has witnessed an escalation in Cyber fraud, exploiting vulnerabilities in online transactions and electronic banking systems. As fraudsters continually evolve their tactics, financial institutions must adapt and employ advanced technologies to stay ahead in the ongoing battle against fraudulent activities.

Terrorism Financing involves providing funds to support terrorist activities. Tracking and preventing such transactions are crucial for national security. Terrorist organizations often exploit financial networks to move money discreetly, necessitating robust mechanisms to identify and disrupt these channels. The interconnected nature of the global financial system makes it imperative to enhance measures that can effectively recognize patterns associated with terrorism financing.

Combating financial crimes often involves leveraging machine learning algorithms for anomaly detection within streaming financial datasets. However, as revealed by Ado, M.N et al, (2023) in the study titled “Comparative Analysis of Financial Fraud Techniques in Nigeria: Unveiling Expert-Based Hacking and Social Engineering Strategies” it was found that all perpetrators of these financial crimes engage in various forms of layering activities. Consequently, this study aims to investigate several methods for detecting layering activities within financial datasets, with the goal of identifying the most effective approach for layering detection.

In the context of financial transactions, layering is a sophisticated pre-laundering technique that involves the deliberate and systematic structuring of multiple financial transactions, often exploiting mechanisms such as currency exchange, to obscure the origin and ownership of funds. In Nigeria, layerers exploit subsidies allocated by financial institutions, such as the USD subsidy allocated by the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) to account holders, by converting funds from NGN to USD through a series of complex transactions. This process creates layers of financial activity, making it difficult for authorities to trace the source of the funds and identify potential illicit activities.

To achieve this objective, the study employs Systematic Detection based on the layering activities and specifications highlighted in the previous study, utilizing extracted features for Systematic Detection on a dataset titled SFinDSet, which contains information on layerers.

To evaluate the performance and accuracy of the Systematic Detection model, the output is compared with the results obtained from various machine learning classification algorithms, including One-Class SVM and Isolation Forest, as well as clustering algorithms such as Online k-Means and hierarchical clustering.

By comparing the effectiveness of these different approaches, the study aims to recommend a more reliable architecture for the detection of financial crimes in streaming data. This approach allows for a comprehensive assessment of the various methods and their suitability for detecting layering activities, thereby enhancing the overall effectiveness of financial crime detection systems.

In the realm of financial crimes mitigation, data assumes a compelling narrative, awaiting articulation through a concise and persuasive voice. As Stephen Few suggests, the information embedded in data becomes truly meaningful when structured adeptly, facilitating pattern identification that, in turn, narrates a compelling story about specific user behaviors. In the context of this research, the process of Systematic Detection unfolds through the meticulous structuring of pertinent data. This structured approach serves as the key to unveiling intricate patterns within financial transactions, ultimately empowering the identification and interpretation of meaningful insights that contribute to a comprehensive understanding of user behaviors in the context of money laundering, fraud, and terrorism financing.

Systematic Detection involves the processes for identification of an instance through the step-wise reduction of the system’s specifics and mechanics. Such processes include extraction of recurring structures, configurations, or regularities within a set of data, observations, or information. It entails discerning meaningful patterns or trends through systematic analysis, allowing for the recognition of relationships, associations, or behaviors that may not be immediately apparent.

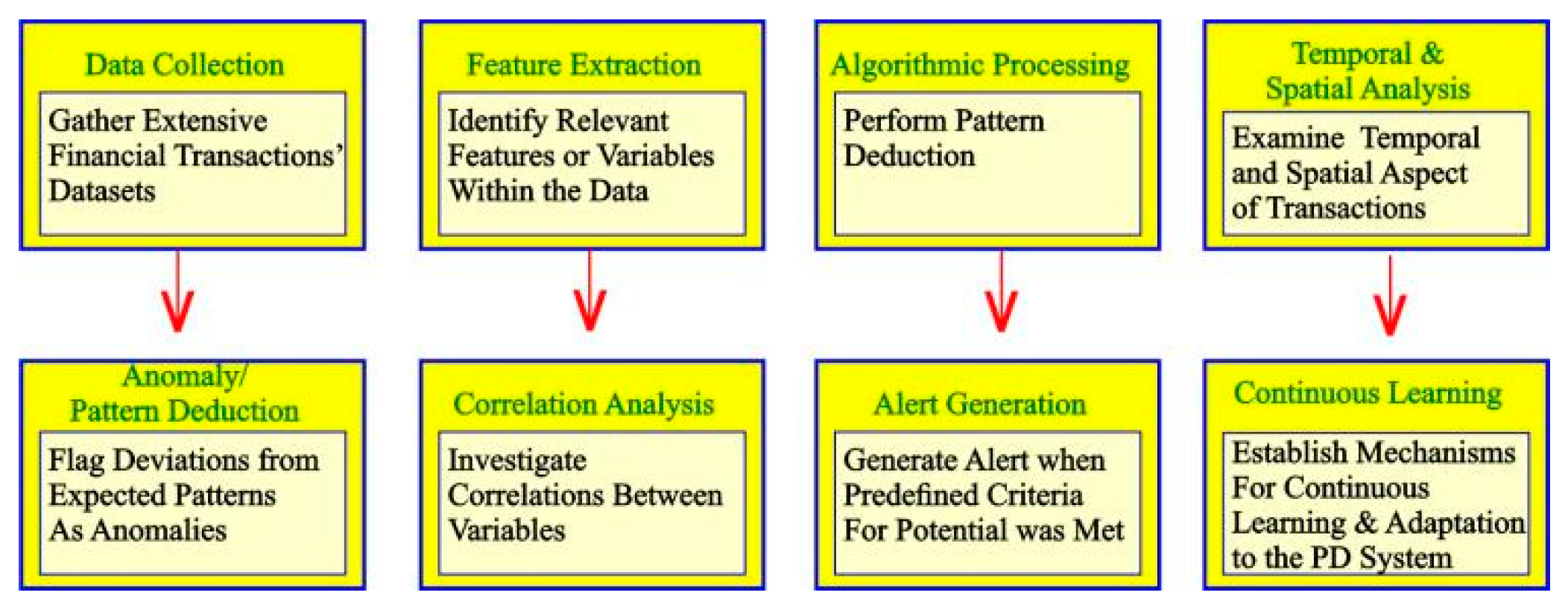

Figure 1 below depicts key components of Systematic Detection Analysis:

User-Centric Systematic Detection Analysis is a sophisticated methodology that places the individual user at the forefront of investigative efforts within the context of financial transactions. It involves a meticulous examination of user behavior patterns, aiming to uncover subtle nuances and distinctive trends that may indicate potential financial crimes such as money laundering, fraud, and terrorism financing.

This approach integrates advanced data analytics and machine learning techniques to discern meaningful patterns within user transactions. By focusing on the specific attributes and behaviors of individual users, the analysis aims to establish a comprehensive understanding of their financial activities. Transactional elements such as source, destination, type, mode, and position are systematically structured and analyzed to unveil unique patterns that may deviate from established norms.

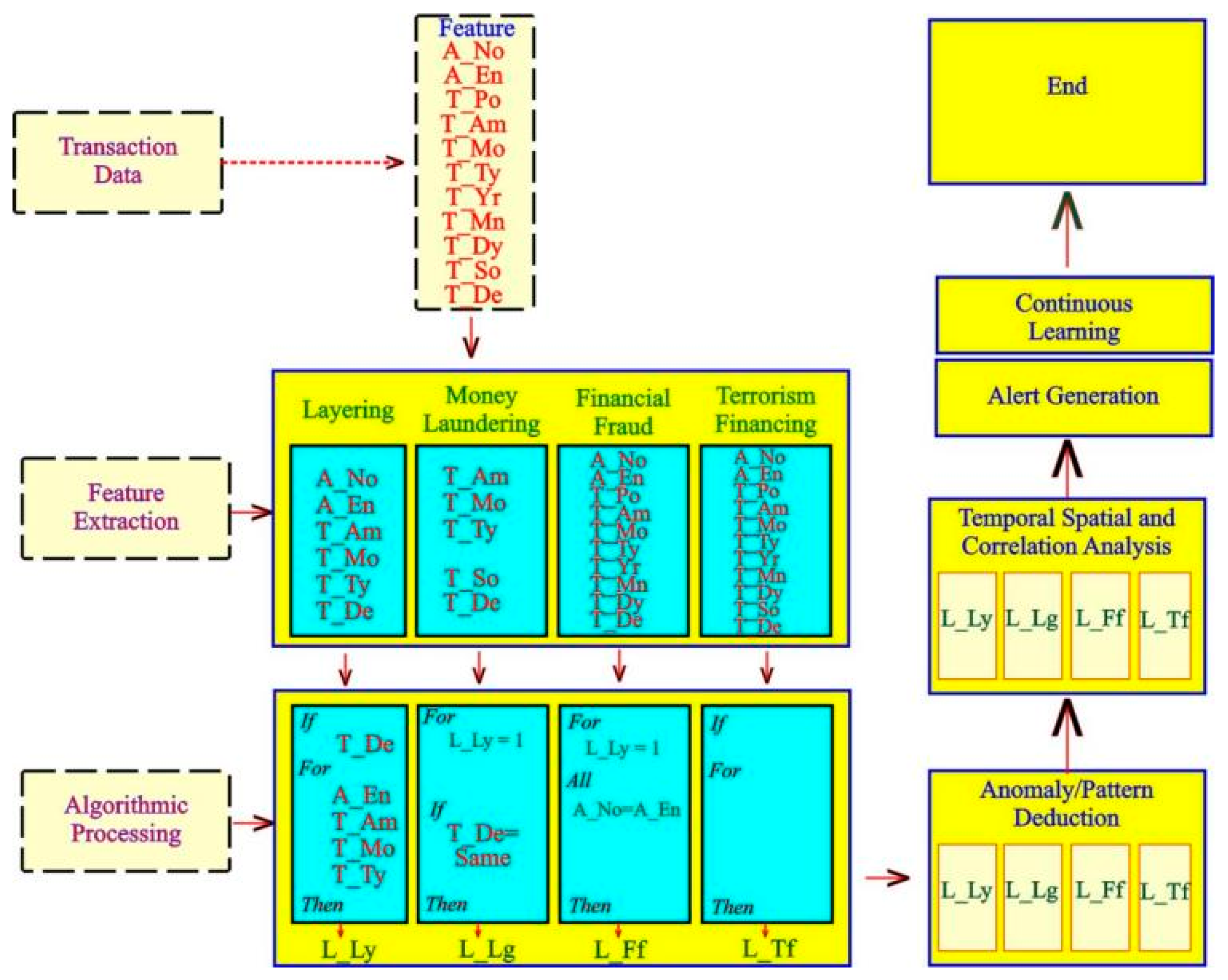

The user-centric aspect of this methodology emphasizes tailoring the analysis to the characteristics of each user, acknowledging that behavioral patterns can vary widely among individuals. As will be seen in

Figure 2, the Systematic Detection of patterns involves the extraction of relevant features and the application of machine learning algorithms for anomaly detection.

The ultimate goal of User-Centric Systematic Detection Analysis is to provide financial institutions and regulatory bodies with a proactive and adaptive tool for identifying and preventing financial crimes. By understanding and interpreting the intricacies of user behavior, this approach contributes to a more robust and personalized framework for ensuring the integrity and security of financial transactions.

Research Objectives

The objectives of this study are to:

Develop a Systematic Detection framework for identifying layering activities in streaming financial transactions.

Evaluate the effectiveness of Systematic Detection using the SFinDSet Kaggle dataset.

Compare the proposed approach with established machine learning and clustering techniques.

Assess the impact of Systematic Detection on reducing false negatives in financial crime detection.

Review

The rapidly evolving landscape of financial transactions has necessitated innovative approaches to combat emerging threats such as money laundering, fraud, and terrorism financing. Traditional methodologies often fall short in capturing the intricacies of individual user behaviors within vast datasets, prompting the exploration of User-Centric Systematic Detection Analysis as a comprehensive solution. This literature review aims to provide a synthesis of existing knowledge, research, and developments in the realm of user-centric Systematic Detection, emphasizing its role in mitigating financial crimes.

Transaction monitoring is necessary to detect and flag suspicious activity in real-time, while behavioral analysis allows for a deeper understanding of a customer’s actions and can help identify potential money-laundering schemes. (DCS AML, 2021). Uncovering Suspicious Patterns: The Power of Behavioral Analysis and Transaction Monitoring in AML. LinkedIn provides a clear overview of the importance of transaction monitoring and behavior analysis in the context of anti-money laundering (AML) efforts. It effectively communicates the key concepts and processes involved in these techniques.

Olaoye (2024) explores the application of machine learning and behavioral analytics in "Fraud Detection in Fintech Leveraging Machine Learning and Behavioral Analytics." The author discusses how machine learning algorithms and behavioral analytics can be combined to detect subtle deviations in user behavior and improve the accuracy of fraud detection mechanisms in the fintech sector.

In their paper titled "Legal Framework for Protecting Banking Transactions in the Metaverse against Deepfake Technology," Arsyad, Ifan, and Wiwoho (2024) highlight the risks posed by deepfake technology to banking transactions in the metaverse. The authors emphasize the need for specific legal regulations to address financial cybercrimes involving deepfake technology, underscoring the importance of regulatory frameworks in mitigating such threats.

Zhang et al. (2023) propose a "Privacy-Preserving Hybrid Federated Learning Framework for Financial Crime Detection" to address the challenges of collaboration and privacy in detecting financial crimes. Their approach utilizes federated learning techniques to enable secure and privacy-aware learning and inference, contributing to the systematic mitigation of financial crimes while preserving data privacy.

Al-Hashmi et al. (2023) introduce an "Ensemble-based Fraud Detection Model for Financial Transaction Cyber Threat Classification and Countermeasures," which leverages ensembling techniques to enhance fraud detection in bank payment transactions. Their comprehensive evaluation demonstrates the effectiveness of the ensemble model in minimizing false positives and improving overall fraud detection accuracy.

Gupta and Mehta (2020) address the dimension reduction of financial data for the detection of financial statement frauds in Indian companies. Their approach emphasizes the importance of feature selection in improving the efficiency and accuracy of fraud detection models, contributing to the systematic mitigation of financial crimes in the Indian context.

Finally, Leon et al. (2020) present a "Pattern Recognition of Financial Institutions' Payment Behavior" methodology, which utilizes supervised machine learning techniques to detect anomalous behavior in financial institutions' payment systems. Their approach offers insights into the development of automated detection systems for financial crimes, enhancing financial oversight and risk management efforts.

In conclusion, the reviewed literature demonstrates a diverse range of approaches and methodologies aimed at systematically mitigating financial crimes through user-centric Systematic Detection analysis. From legal frameworks to advanced technological solutions, these research contributions provide valuable insights and tools for addressing the multifaceted challenges of financial crime prevention and detection.

The advent of advanced data analytics and machine learning presents an opportunity to revolutionize the fight against financial crimes. However, integrating these technologies into existing financial systems poses challenges, including data privacy concerns, ethical considerations, and the need for collaboration between researchers, financial institutions, and regulatory bodies.

In light of these challenges and opportunities, this research endeavors to develop a systematic approach for mitigating financial crimes. As seen from Fig. 1, the proposed user-centric Systematic Detection analysis model aims to leverage technological advancements to uncover intricate behavioral patterns associated with money laundering, fraud, and terrorism financing. By doing so, the research seeks to contribute to a more secure financial landscape, fostering trust in financial transactions and fortifying the global fight against financial crimes.

Methodology

This section outlines the approach to collecting and analyzing user transaction data. It explains the integration of data analytics techniques and machine learning algorithms to uncover and understand intricate patterns in user behavior related to financial transactions.

The methodology for Systematic Detection on SFinDSet include:

The script begins by importing the pandas library and then loads a dataset named 'SFinDSet.csv' into a DataFrame.

Conditions are applied to the DataFrame to generate a new column named 'L1'. The 'L1' column is assigned a value of 1 for rows where the 'Transaction_Type' is 'NGN to USD' and the 'Transaction_Mode' is 'Card Out', and otherwise 0.

Rows are filtered from the DataFrame based on the condition in the 'L1' column. Rows where the 'L1' column value is 1 are retained, creating a new DataFrame named filtered.

The filtered DataFrame is sorted based on the 'Account_Name' column in ascending order, creating a new DataFrame.

Duplicate 'Account_Name' values are identified within the sorted DataFrame.

Labels 'L2' are assigned to attributes with similar names in the 'Account_Name' column within the sorted DataFrame.

The sorted DataFrame is sorted based on the 'Transaction_Destination' column in ascending order.

Duplicate 'Transaction_Destination' values are identified within the sorted DataFrame.

Labels 'L3' are assigned to attributes with similar values in the 'Transaction_Destination' column within the sorted DataFrame.

Unique values from the 'L3' column are extracted and stored in the unique_values variable.

Complete records (rows) associated with unique values from the 'L3' column are extracted and stored.

Account names are extracted from the stored DataFrame and stored.

Records in the original DataFrame are filtered based on the extracted account names, creating a new DataFrame of records.

The filtered records DataFrame is saved to a new CSV file.

These processes manipulate the DataFrame based on specified conditions and sort the data accordingly, with the final output being a filtered dataset saved to a CSV file.

Algorithm for Systematic Detection on SFinDSet Dataset

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

df = pd.read_csv('SFinDSet.csv')

df['L1'] = ((df['Transaction_Type'] == 'NGN to USD') & (df['Transaction_Mode'] == 'Card Out')).astype(int)

df.to_csv("SFinDSet01.csv", index=False)

filtered_df = df[df['L1'] == 1]

filtered_df.to_csv("SFinDSetO2.csv", index=False)

sorted_df = filtered_df.sort_values(by='Account_Name', ascending=True)

sorted_df.to_csv("SFinDSetO3.csv", index=False)

duplicate_accounts = sorted_df[sorted_df.duplicated('Account_Name', keep=False)]

duplicate_accounts.to_csv("SFinDSetO4.csv", index=False)

duplicate_accounts['L2'] = duplicate_accounts.groupby('Account_Name').ngroup()

duplicate_accounts.to_csv("SFinDSetO5.csv", index=False)

sorted_df_2 = duplicate_accounts.sort_values(by='Transaction_Destination', ascending=True)

sorted_df_2.to_csv("SFinDSetO6.csv", index=False)

duplicate_destinations = sorted_df_2[sorted_df_2.duplicated('Transaction_Destination', keep=False)]

duplicate_destinations.to_csv("SFinDSetO7.csv", index=False)

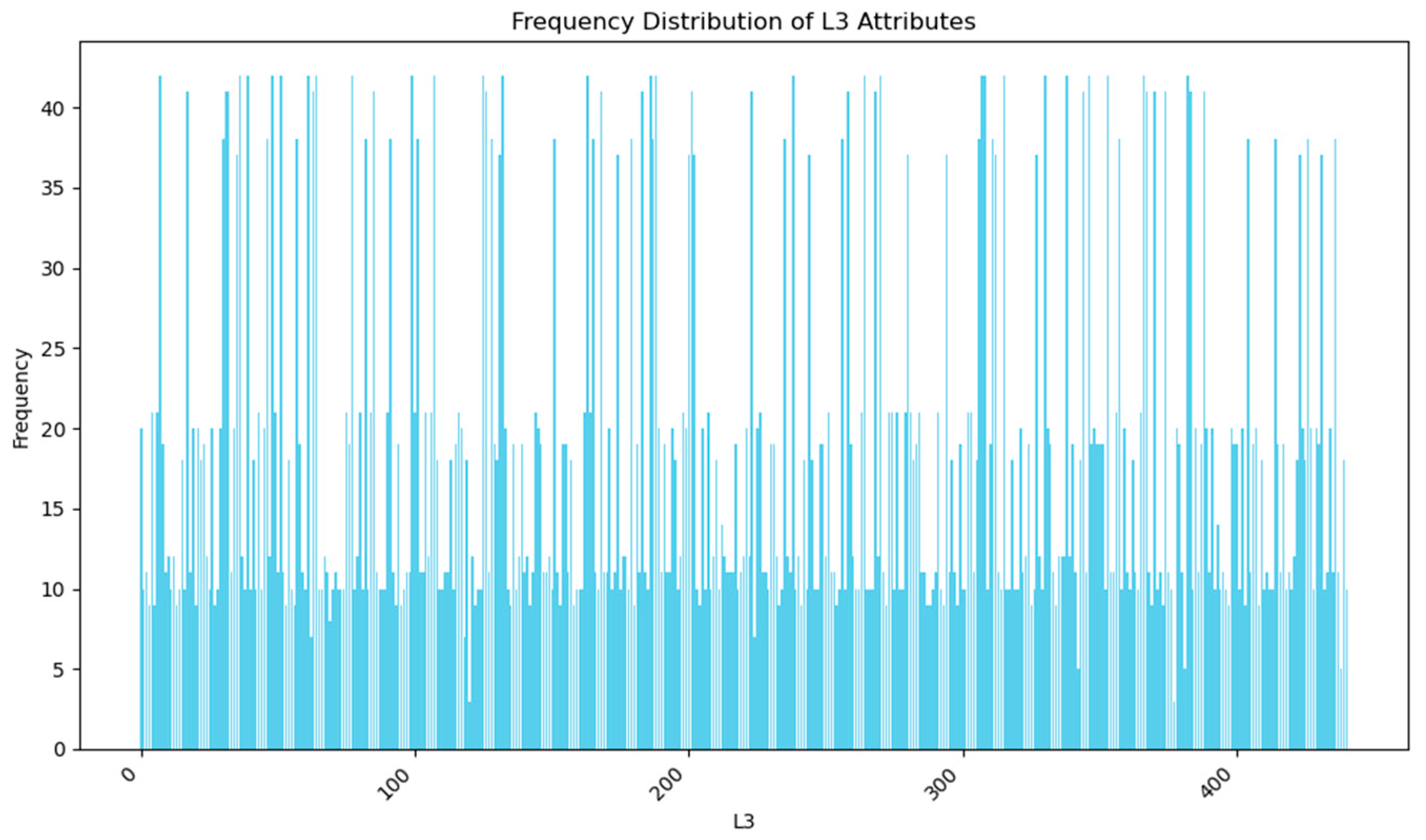

duplicate_destinations['L3'] = duplicate_destinations.groupby('Transaction_Destination').ngroup()

duplicate_destinations.to_csv("SFinDSetO8.csv", index=False)

statistics = duplicate_destinations[['L1', 'L2', 'L3']].describe()

statistics.to_csv('SFinDSetLayers.csv')

freq_l3 = duplicate_destinations['L3'].value_counts().reset_index()

freq_l3.columns = ['L3', 'Frequency']

freq_l3.to_csv('SFinDSetFreq.csv', index=False)

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.bar(freq_l3['L3'], freq_l3['Frequency'], color='skyblue')

plt.xlabel('L3')

plt.ylabel('Frequency')

plt.title('Frequency Distribution of L3 Attributes')

plt.xticks(rotation=45, ha='right')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.savefig('Frequency_Distribution.png')

unique_records = duplicate_destinations.drop_duplicates(subset=["L3"])

unique_records.to_csv("SFinDSet010.csv", index=False)

account_names = unique_records["Account_Name"]

account_names_df = pd.DataFrame(account_names, columns=["Account_Name"])

account_names_df.to_csv("SFinDSetO11.csv", index=False)

sfindset_data = pd.read_csv("SFinDSet.csv")

account_names = pd.read_csv("SFinDSetO11.csv")["Account_Name"].tolist()

filtered_records = sfindset_data[sfindset_data['Account_Name'].isin(account_names)]

filtered_records.to_csv("SFinDSetO12.csv", index=False) |

Results and Performance Evaluation

Table 1.

Summary of Suspected and Confirmed Layerers, Oct. 2021.

Table 1.

Summary of Suspected and Confirmed Layerers, Oct. 2021.

| |

Suspected Layering (L1) |

Confirmed Layering (L2) |

Confirmed Layerers (L3) |

Layerers’ Activities |

| Count |

60033 |

7694 |

441 |

15556 |

| Percentage |

5.7252 |

0.73 |

0.0004 |

1.4835 |

The data in

Table 1 above presents counts and percentages for the four categories related to suspected and confirmed layering activities:

There are 60,033 instances of suspected layering identified in the dataset, which represents approximately 5.73% of the total transactions. Suspected layering refers to transactions that exhibit characteristics or patterns suggesting the possibility of layering activities, such as multiple transfers between accounts or rapid movement of funds.

Out of the suspected layering cases, 7,694 instances have been confirmed as actual cases of layering, accounting for approximately 0.73% of the total transactions. Confirmed layering indicates transactions that have undergone further scrutiny or investigation and have been verified to involve actual layering activities.

Within the confirmed layering cases, there are 441 unique individuals or entities identified as confirmed layerers. This represents a very small percentage of the total entities involved in the transactions, approximately 0.04%.

The frequency distributions of 'L3' attributes plotted to visualize patterns and distributions within the data will be seen in

Figure 3 below:

The confirmed layerers have been involved in a total of 15,556 activities in the entire dataset. These activities might include various forms of transactions designed to obscure the origin or destination of funds, such as multiple transfers, rapid movement of funds between accounts, or use of intermediaries.

Overall, the analysis indicates that while suspected layering activities are relatively common, only a small percentage of these cases are confirmed as actual instances of layering. Additionally, the number of individuals or entities engaged in confirmed layering activities is very small compared to the total number of entities involved in the transactions. However, these confirmed layerers are involved in a significant number of activities, highlighting the potential impact of their actions on financial systems and the importance of detecting and mitigating such activities.

These figures provide insights into the scale of layering activities detected within the SFinDSet dataset for October 2021.

This is achieved by comparing the output of the Systematic Detection model with the results obtained from various machine learning classification algorithms, including One-Class SVM and Isolation Forest, as well as clustering algorithms such as Online k-Means and hierarchical clustering.

Each of Isolation Forest, One-Class Support Vector Machine (O-C SVM) as well as Online k-Means were used to detect anomalies from the SFinDSet dataset based on ‘Transaction_Destination’ column. The detected anomalies for each were subjected to the similar Systematic Detection for layering and the outcome is presented in

Table 2 below:

The analysis of the machine learning algorithms' output, particularly in detecting anomalies related to layering in financial transactions, provides valuable insights into the effectiveness of different approaches for identifying suspicious activities:

Isolation Forest demonstrates varying performance based on the contamination ratio parameter.

At lower contamination ratios (0.01 and 0.02), Isolation Forest detects a relatively small number of layering instances but with a high proportion of unique layerers.

As the contamination ratio increases (0.05), Isolation Forest identifies a larger number of layering instances, indicating a broader scope of detection. However, the proportion of unique layerers remains relatively consistent.

When using an auto-contamination ratio, Isolation Forest detects a significantly higher number of layering instances compared to other contamination ratios, suggesting a more aggressive approach to anomaly detection. However, the proportion of unique layerers decreases slightly, indicating its inappropriateness in detecting anomalies. Therefore, when using Isolation Forest on a large dataset it is better to use a specific contamination ratio like 0.05 because it identifies a larger number of layering instances (439), although the proportion of unique layerers remains relatively consistent.

One-Class SVM exhibits a higher sensitivity to detecting layering instances compared to Isolation Forest at a contamination ratio of 0.01, identifying a larger number of instances and unique layerers.

However, the number of common layerers between One-Class SVM and the Systematic Detection model is relatively low, suggesting some discrepancies in the identification of specific individuals or entities engaged in layering activities.

Online k-Means shows moderate performance in detecting layering instances, with a similar number of detected instances compared to Isolation Forest at a contamination ratio of 0.05.

At a threshold of 95%, Online k-Means identifies a substantial number of layering instances with a relatively high proportion of unique layerers.

Interestingly, at a threshold of 99%, Online k-Means does not detect any layering instances. However, it identifies a significant number of common layerers with the Systematic Detection model, suggesting a complementary role in identifying specific individuals or entities engaged in layering activities.

The presence of common layerers between the machine learning models and the Systematic Detection model indicates consistency in identifying specific individuals or entities engaged in layering activities across different detection approaches.

This overlap strengthens the confidence in the accuracy of the identified layerers and provides additional validation for the effectiveness of both the machine learning algorithms and the Systematic Detection model in detecting suspicious financial activities.

Overall, the analysis highlights the importance of considering multiple detection approaches and parameters in identifying layering activities, as well as the need for ongoing evaluation and validation of the detection results to enhance the effectiveness of financial crime detection systems.

Therefore, the performance for them all is given in

Table 3 below:

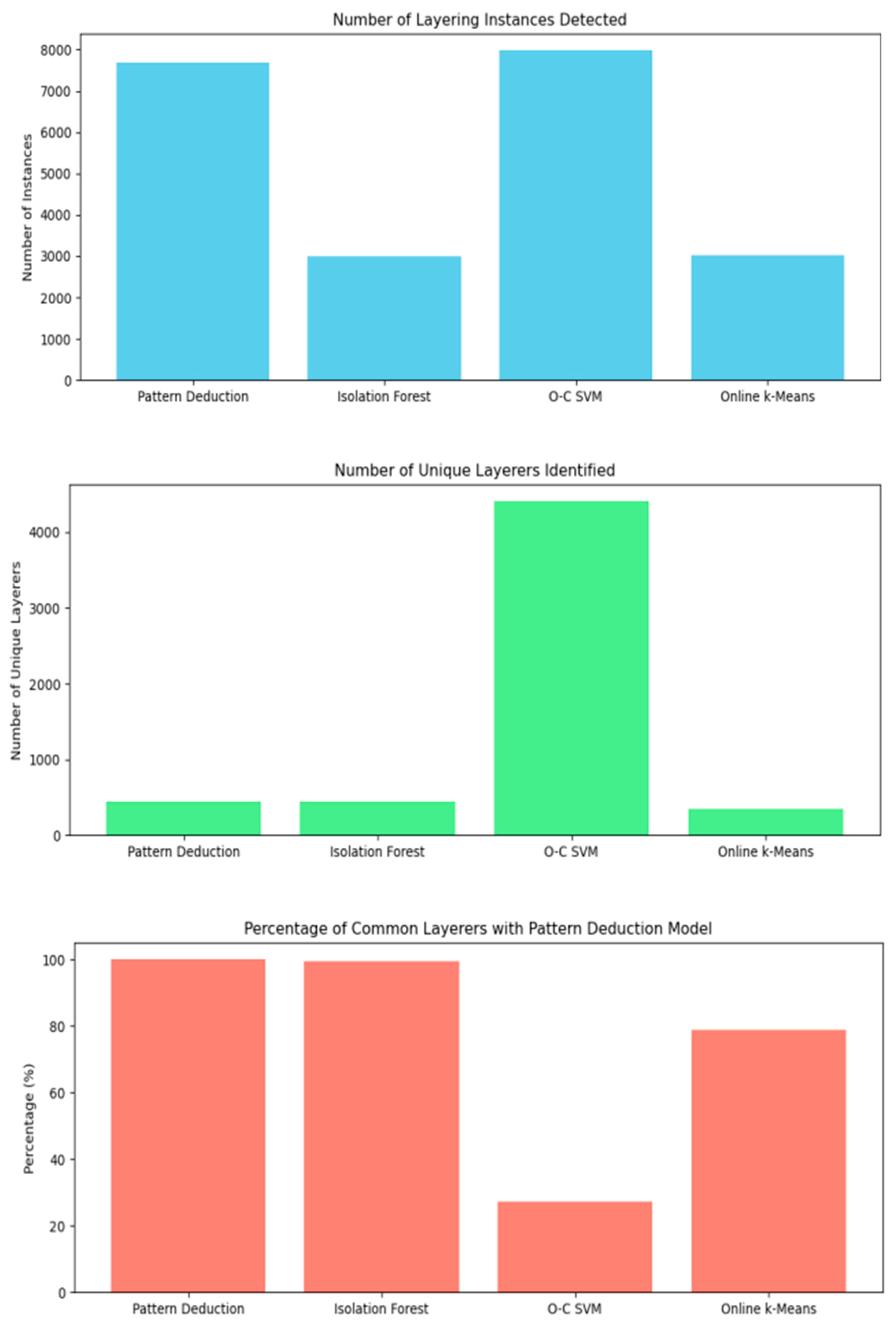

The results of the analysis, from

Table 3 above, reveal notable differences in the performance of the various layering detection models. The Systematic Detection model, characterized by its systematic approach, identifies 7,694 layering instances and 441 unique layerers, serving as a benchmark for comparison. In contrast, the Isolation Forest algorithm, a classification-based approach, detects 3,005 layering instances and 439 unique layerers, demonstrating a high degree of consistency (99.54%) with the Systematic Detection model. However, the O-C SVM algorithm, also a classification model, exhibits lower performance, identifying 7,978 layering instances but only 121 unique layerers, resulting in a lower percentage of common layerers (27.43%). Similarly, Online k-Means, a clustering-based approach, detects 3,013 layering instances and 348 unique layerers, with a percentage of common layerers of 78.91%.

Base on this, it can be said that Systematic Detection model (with 441) unique layerers outperforms Isolation Forest (439), O-C SVM (121) and Online k-Means (349)

Figure 4.

Performance of Machine Learning Algorithms.

Figure 4.

Performance of Machine Learning Algorithms.

From the bar plot (

Figure 4) above, it is evident that the Systematic Detection approach significantly outperforms all machine learning algorithms utilized in the detection of layering and layerers. Notably, Isolation Forest, with a contamination ratio of 0.05, falls marginally short of matching the performance of Systematic Detection by only 0.45%. However, this seemingly small difference translates to 45 instances in a dataset with 10,000 layerers, signifying a substantial potential for missed detection of financial fraudsters.

In light of these findings, the following recommendations can be proposed:

- ✓

Enhanced Integration of Systematic Detection Techniques:

Given the superior performance of Systematic Detection, there is merit in further integrating and refining its techniques within existing machine learning algorithms. This could involve incorporating domain-specific rules and heuristics derived from Systematic Detection methodologies to enhance the accuracy and robustness of machine learning-based detection systems.

- ✓

Systematic Detection as Benchmark:

Systematic Detection should be used as the benchmark for the detection of layering and layerers. Given its superior performance, Systematic Detection can serve as the base model for detecting financial fraudsters. This approach involves isolating complete layerers and their activities using Systematic Detection, a supervised method, from vast datasets. Subsequently, machine learning algorithms, especially classification algorithms such as Isolation Forest, can be applied to detect money laundering, fraud, and terrorism financing from the dataset pre-filtered by Systematic Detection. By leveraging the strengths of both Systematic Detection and machine learning algorithms, more accurate and reliable detection of financial crimes can be achieved.

- ✓

Optimization of Isolation Forest Parameters:

For algorithms like Isolation Forest, fine-tuning parameters such as the contamination ratio could be explored to minimize the gap in performance compared to Systematic Detection. Experimentation with different parameter settings and optimization techniques may help achieve more competitive results in detecting layering activities.

- ✓

Ensemble Learning Approaches:

Employing ensemble learning techniques, which combine the outputs of multiple algorithms, could be beneficial in mitigating the limitations of individual models. By leveraging the strengths of diverse detection methods, ensemble learning can enhance overall detection accuracy and reliability, thereby reducing the risk of false negatives in identifying financial fraudsters.

- ✓

Continuous Monitoring and Evaluation:

Continuous monitoring and evaluation of detection models are essential to adapt to evolving financial crime patterns and ensure ongoing effectiveness. Regular assessment of model performance, coupled with feedback mechanisms from real-world case studies and expert insights, can inform iterative improvements and refinements to detection strategies.

- ✓

Interdisciplinary Collaboration:

Collaboration between financial domain experts, data scientists, and law enforcement agencies is crucial in developing holistic approaches to combat financial crimes effectively. By leveraging interdisciplinary expertise and sharing knowledge across domains, innovative solutions can be devised to address the dynamic challenges posed by sophisticated fraud schemes.

By implementing these recommendations, stakeholders can bolster their efforts in detecting and preventing financial fraud, ultimately safeguarding financial systems and protecting stakeholders from potential losses.

References

- Al-Hashmi, A., Alashjaee, A., Darem, A., Alanazi, A., & Effghi, R. (2023). An Ensemble-based Fraud Detection Model for Financial Transaction Cyber Threat Classification and Countermeasures. Engineering, Technology and Applied Science Research, 13, 12253-12259. [CrossRef]

- Arsyad, I., & Wiwoho, J. (2024). LEGAL FRAMEWORK FOR PROTECTING BANKING TRANSACTIONS IN THE METAVERSE AGAINST DEEPFAKE TECHNOLOGY. Journal of Law and Sustainable Development, 12, e3199. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S., & Mehta, S. (2020). Feature Selection for Dimension Reduction of Financial Data for Detection of Financial Statement Frauds in Context to Indian Companies. Global Business Review. [CrossRef]

- Jullum, M., Løland, A., Huseby, R., Ånonsen, G., & Lorentzen, J. (2020). Detecting money laundering transactions with machine learning. Journal of Money Laundering Control. Advance online publication. [CrossRef]

- Leon, C., Barucca, P., Acero, O., Gage, G., & Ortega, F. (2020). Pattern recognition of financial institutions’ payment behavior. Latin American Journal of Central Banking, 1, 100011. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad Nuraddeen Ado. (2025). SFinDSet for Systematic Detection of FinCrimes [Data set]. Kaggle. [CrossRef]

- Olaoye, G. (2024). Fraud Detection in Fintech Leveraging Machine Learning and Behavioral Analytics. Machine Learning.

- Ravaglia, A. (2022, December 21). Fraud Detection Modeling User Behavior. Data Reply IT | DataTech. Retrieved from [https://medium.com/data-reply-it-datatech/fraud-detection-modeling-user-behavior-6d4f7bba1422].

- Utkina, M. (2023). DIGITAL IDENTIFICATION AND FINANCIAL MONITORING: NEW TECHNOLOGIES IN THE FIGHT AGAINST CRIME. Scientific Journal of Polonia University, 58, 303-308. [CrossRef]

- Vinner, E. (2023). The Concept and Types of Crimes that form Illegal Transactions with Securities. Юридические исследoвания, 40-50. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Hong, J., Dong, F., Drew, S., Xue, L., & Zhou, J. (2023). A Privacy-Preserving Hybrid Federated Learning Framework for Financial Crime Detection. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).