1. Introduction

Lead exposure remains a significant global environmental health issue, particularly affecting children in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), where regulations on industry, pollution control, and routine environmental monitoring are frequently insufficient [

1]. As a potent neurotoxin, lead accumulates in the body over time and lacks a known safe exposure threshold. It is particularly detrimental to children under five, as it disrupts brain development, leading to lasting cognitive and behavioral challenges [

2].

According to the most recent Global Burden of Disease estimates from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), lead exposure was responsible for approximately 1.5 million deaths and more than 25 million years lived with disability (YLDs) in 2021, with cardiovascular diseases and neurodevelopmental impairments being the primary outcomes [

3,

4]. Despite the global phase-out of leaded gasoline, exposure continues to arise from sources such as contaminated drinking water, industrial emissions, lead-based paints, traditional cosmetics, spices, and ceramics [

3,

4].

In 2021, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) revised the blood lead reference value from 5 µg/dL to 3.5 µg/dL, reflecting a broader scientific agreement that even very low exposure levels can be hazardous [

5]. Importantly, recent evidence confirms that there is no safe blood lead level, as any detectable amount may adversely affect children's neurodevelopment and long-term health [

5,

6]. This change highlights the necessity for proactive public health measures and enhanced environmental monitoring.

Georgia has encountered ongoing issues with lead exposure, as revealed by a nationwide survey in 2018 from UNICEF and the National Center for Disease Control and Public Health (NCDC), which indicated that 41% of 5–7 year old children had BLLs exceeding 5 µg/dL [

7]. Regional variations were pronounced, particularly in western areas of Georgia, such as Adjara and Guria, which demonstrated disproportionately high BLLs.

In response to the MICS results, the Georgian government implemented a comprehensive national strategy that includes the adoption of a National Environmental Health Action Plan in 2018, regulatory measures on early detection and management of lead poisoning, revisions to state screening programs to include BLL testing, and the establishment of clinical protocols to guide pediatric assessment and intervention.

Subsequent investigations conducted between 2020 and 2025 confirmed the persistence of exposure in these regions, documenting multiple environmental pathways—including contaminated household dust, spices, and other domestic sources—and highlighting the need for continued surveillance and targeted interventions [

8,

9,

10]. A national analysis conducted after 2019 demonstrated significant reductions in children's BLLs following coordinated governmental interventions, yet confirmed persistent regional disparities [

8]. A lead isotope feasibility study further identified that household factors, particularly specific spices and indoor dust, were likely contributors to childhood exposure in affected regions, whereas certain high-lead soil and paint samples did not isotopically match children's BLL signatures [

9]. Most recently, a 2023–2024 feasibility study using volumetric absorptive microsampling (VAMS) in Adjara and Imereti confirmed ongoing exposure in select communities and highlighted local predictors such as housing conditions, household product use, and region-specific practices, underscoring the need for context-sensitive, site-specific public health action [

10].

Until recently, the absence of centralized surveillance data has posed significant challenges in comprehensively evaluating geographic, demographic, and temporal patterns of lead exposure in Georgia. This study represents the first nationwide descriptive analysis of lead surveillance data collected through Georgia's state program, "Early Detection and Screening of Diseases," spanning the period from 2020 to 2023. By systematically examining variables such as age, sex, regional disparities, and temporal trends, this analysis seeks to provide critical insights to inform evidence-based environmental health policies, optimize resource allocation, and guide future research priorities. The aim of this study is to describe the distribution of blood lead levels among Georgian children, identify temporal trends and regional disparities, and provide epidemiological evidence to support targeted public health interventions.

2. Materials and Methods

This descriptive cross-sectional study evaluated anonymized data from the national State Program for Early Detection and Screening of Diseases, specifically focusing on the lead component, from January 2020 to December 2023. The analysis concentrated on children under 18 years who underwent at least one screening for BLLs throughout the program period.

The screening program was formalized through the State Standard (Protocol) for Clinical Management: "Early Detection and Management of Toxic Lead Exposure in Children" (approved by Ministerial Order No. 01-148/o, April 23, 2019). The primary target population included children aged 24–84 months, with additional screening indicated for children with clinical signs, high-risk environmental exposure, or nutritional deficiencies. The screening program operates on a symptom-based approach, where healthcare providers determine whether a child should be tested based on clinical assessment, exposure risk factors, and professional judgment. All children enrolled in the state health program are tested using venous blood samples analyzed by certified laboratories. Case management protocols included environmental assessment, nutritional counseling, quarterly monitoring for BLLs 5–34.9 µg/dL, and referral to specialized care for BLLs ≥35 µg/dL.

The dataset, sourced from the NCDC, included demographic information such as age, sex, administrative region, and lead test results. Only entries with complete information for age, sex, region, and BLL values were included in the analysis, while records with missing or inconsistent identifiers, test dates, or BLL values were excluded (N=778).

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics software. Chi-square tests assessed differences between categorical variables (e.g., sex and elevated BLL categories), while t-tests and correlation coefficients examined differences between continuous variables like age and BLL. Trends in BLL over time were represented using line graphs, and regional variations were illustrated through bar charts.

Ethical considerations were upheld by fully anonymizing the dataset prior to analysis, ensuring no personal identifiers were accessible to researchers

3. Results

The analysis included a total of 32,048 children under 18 years, comprising 17,387 (54.3%) males and 14,661 (45.7%) females. The overall mean BLL was 3.56 µg/dL (SD ±1.72), with a declining trend noted over the four-year span.

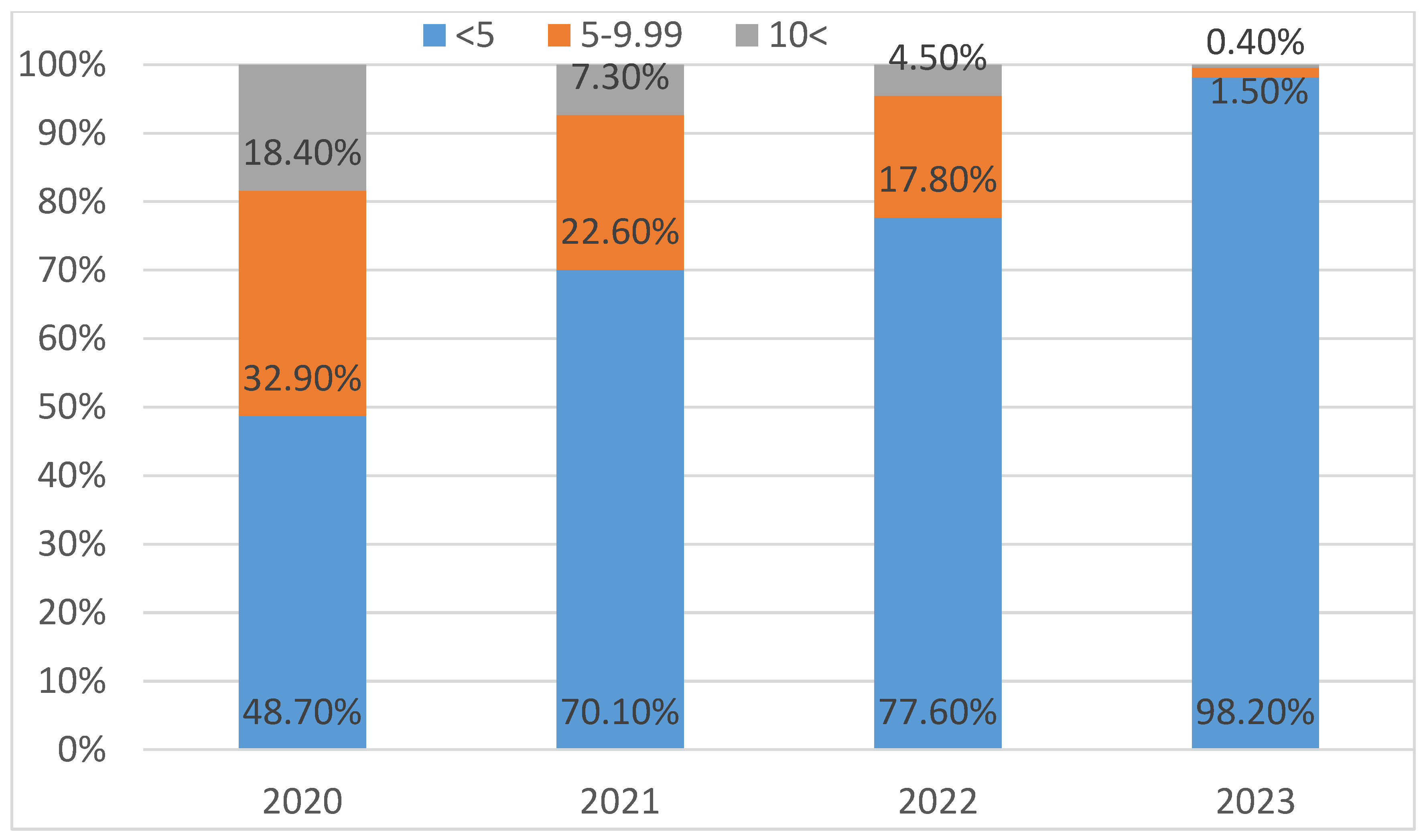

From 2020 to 2023, there was a statistically significant decrease in the prevalence of moderate (5–9.99 µg/dL) and high (≥10 µg/dL) BLL cases (p < 0.001) (

Figure 1).

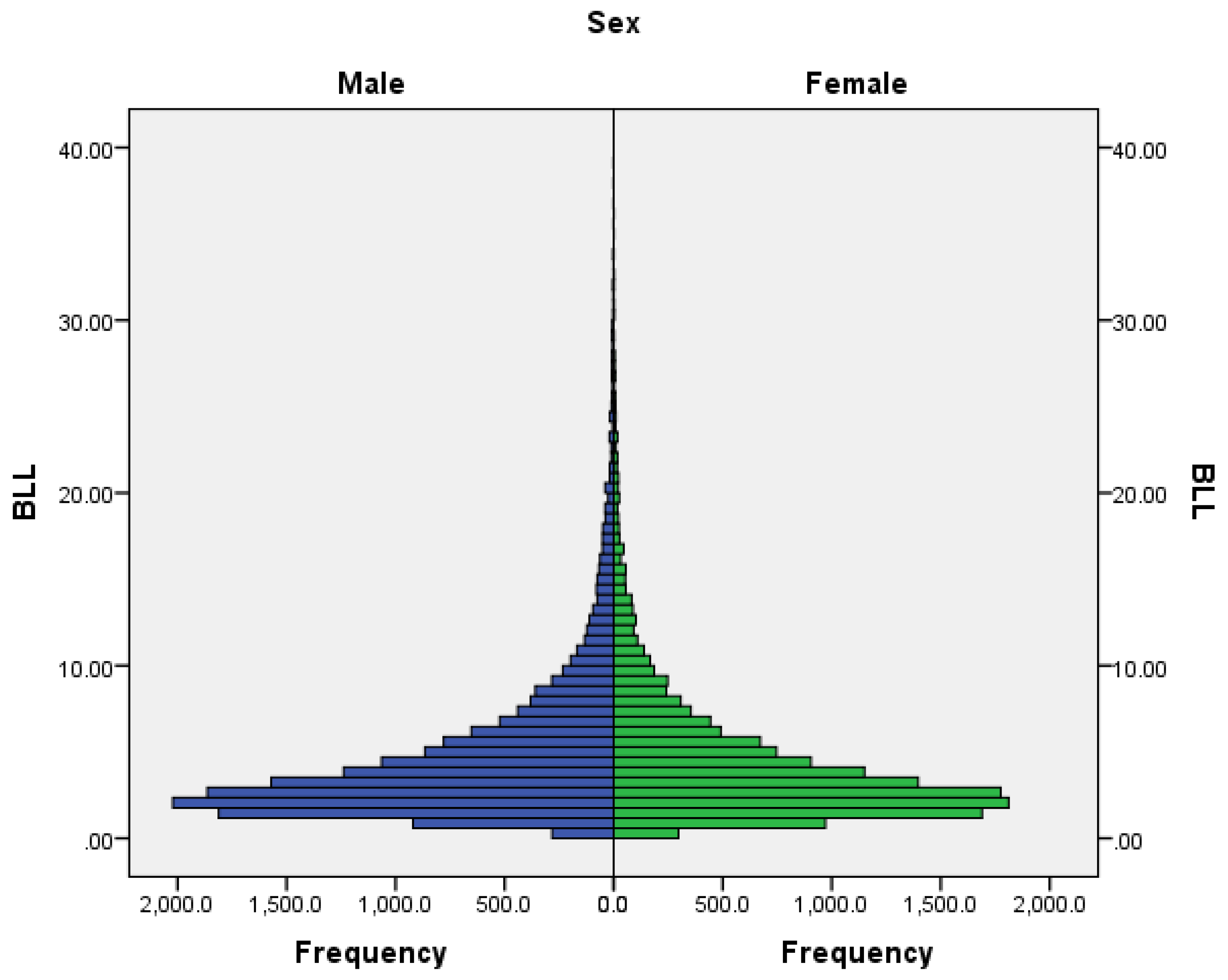

BLL distribution by sex showed no statistically significant difference between males and females (p = 0.19) (

Figure 2).

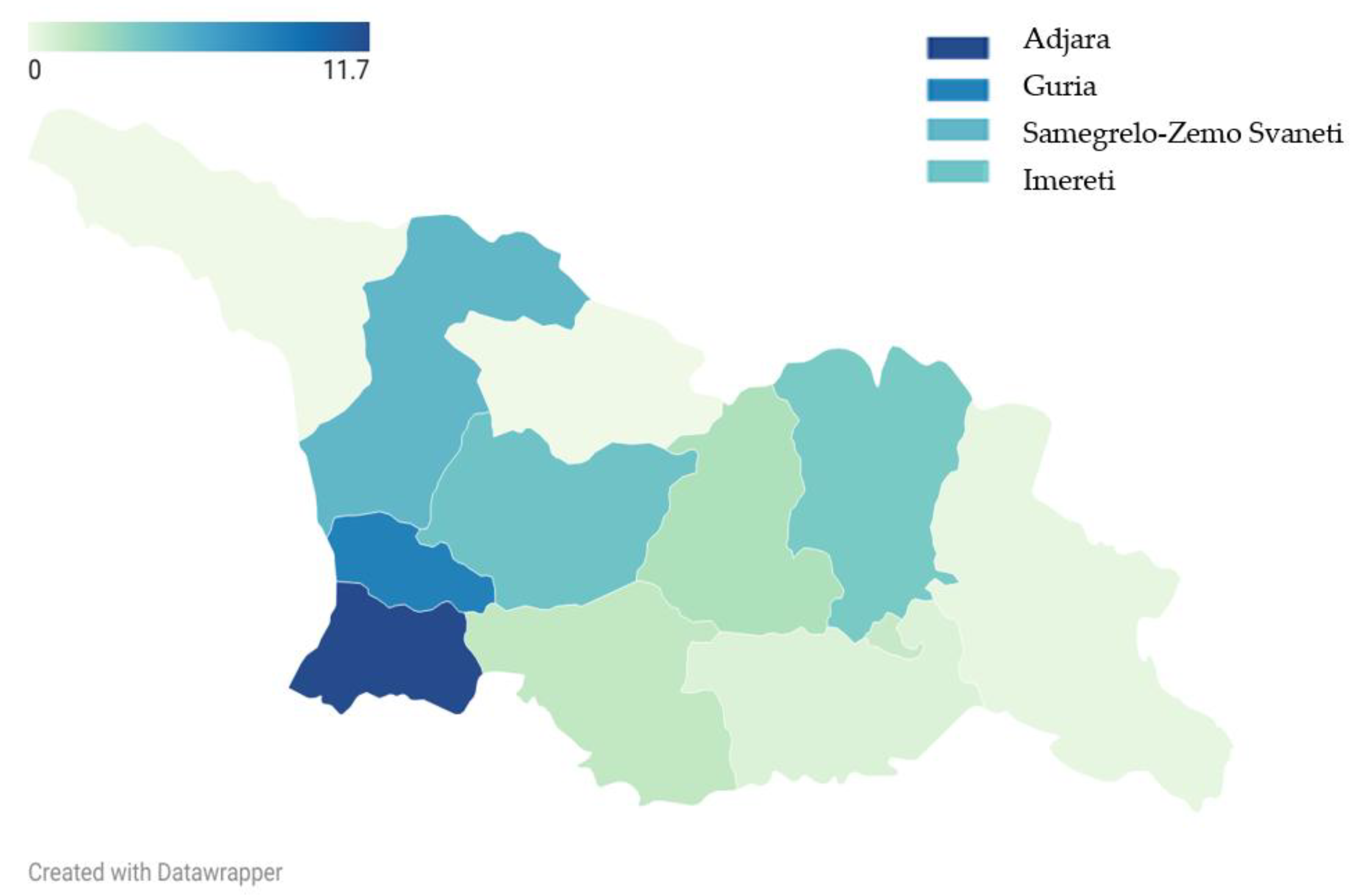

Adjara (11.7%) and Guria (8.3%) had the highest proportions of children with BLLs ≥10 µg/dL, followed by Samegrelo-Zemo Svaneti (4.9%) and Imereti (4.2%) (

Figure 3).

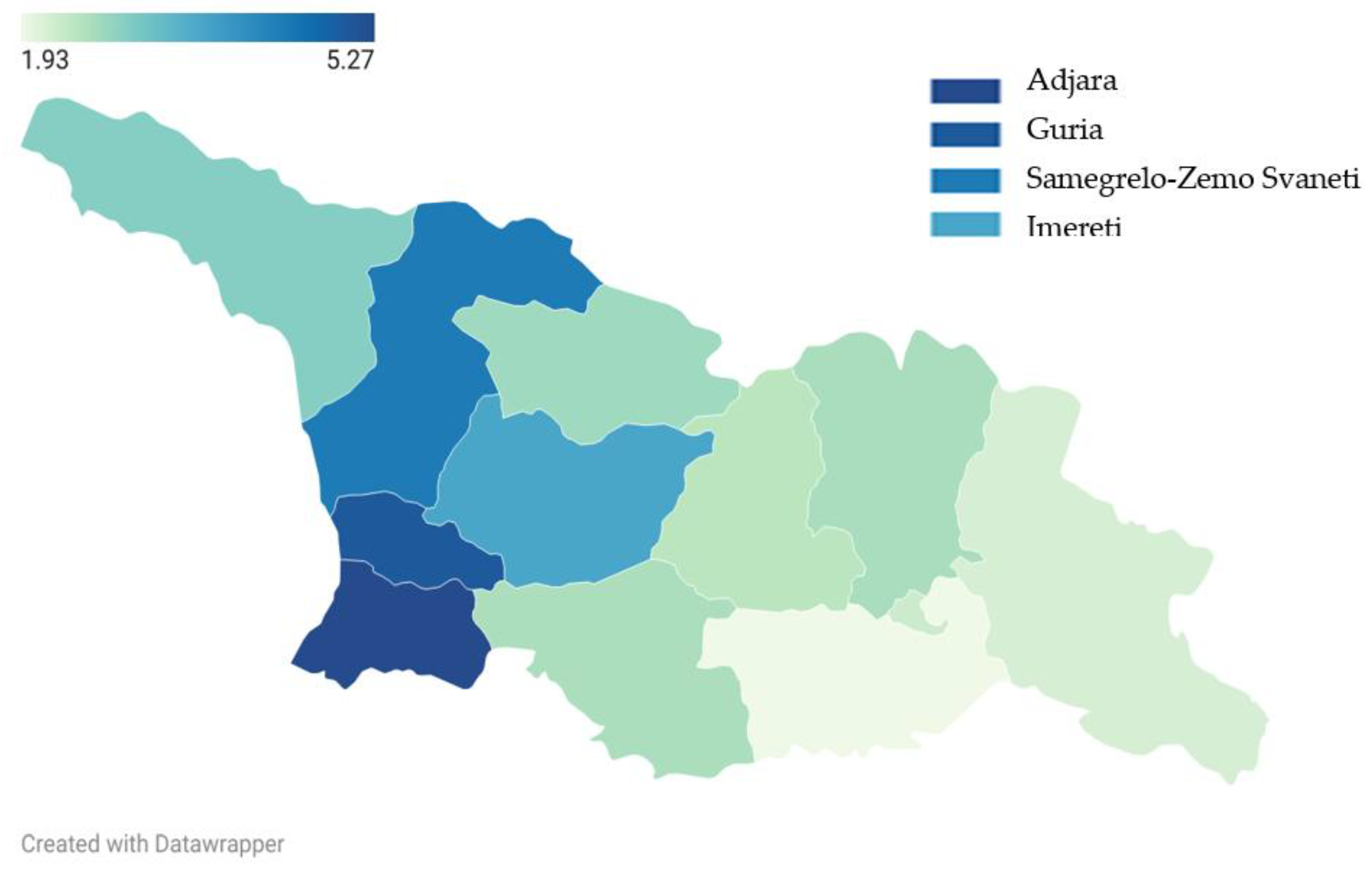

Adjara had the highest mean BLL (5.27 µg/dL), followed by Guria (5.01 µg/dL), Samegrelo-Zemo Svaneti (4.41 µg/dL), and Imereti (3.63 µg/dL) (

Figure 4).

4. Discussion

This nationwide descriptive research on BLLs distribution in Georgia's children reveals promising trends while also highlighting ongoing regional disparities and pressing public health issues. The significant reduction in BLLs between 2020 and 2023 indicates that Georgia's national screening and intervention strategies may be effective. Increasing awareness amongst the public and medical community and the incorporation of environmental health priorities into public policy, clinical guidelines, and state-funded screening initiatives appears to be showing early success.

Viewed through comparative and reflective lenses, Georgia's experience fits within broader global dynamics of declining lead exposure in countries that have invested in sustained policy enforcement and environmental surveillance. A comprehensive systematic review by Ericson et al. [

11], covering 49 low- and middle-income countries, reported that approximately half of all children studied had BLLs ≥ 5 µg/dL, underscoring the immense burden of exposure in settings with limited regulatory capacity. By comparison, Georgia's national average BLL of 3.56 µg/dL represents a more favorable profile, with the steady reduction in elevated cases suggesting measurable progress in addressing childhood lead exposure.

However, persistent regional disparities, notably in Adjara and Guria, remain a cause for concern. These findings are consistent with earlier reports [

7] and parallel regional exposure patterns identified in other LMICs. The regional differences observed in blood lead level distribution may be shaped by diverse local conditions, including environmental pollution, socioeconomic context, household exposure pathways, as well as differences in awareness and knowledge about lead exposure among healthcare providers across regions. Western regions, such as Adjara and Guria, have shown comparatively higher averages over recent years; however, these patterns are likely multifactorial and context-dependent rather than indicative of a single dominant exposure source. Higher testing rates in regions where healthcare providers are more familiar with lead screening programs may contribute to the observed regional patterns. This highlights the importance of site-specific investigations and context-sensitive interventions that consider the environmental and behavioral diversity across Georgia [

7,

12]. Lead isotope analysis has further confirmed that household sources, particularly contaminated spices and indoor dust, are more likely contributors than outdoor soil or paint in affected communities [

9].

The clustering of high BLLs in specific western regions underscores the necessity for tailored interventions that include localized risk assessments, environmental remediation efforts, and public education campaigns.

Strengths of this study include the utilization of a national dataset spanning multiple years and regions, providing a broad overview of lead exposure among Georgian children. However, limitations should be acknowledged. The reliance on screening data introduces the possibility of selection bias, as children tested were not chosen through a random population-based sampling method. Additionally, data regarding environmental exposure sources, socioeconomic factors, or follow-up outcomes were not available for inclusion.

Despite these limitations, the study offers valuable insights into the national burden and geographic distribution of childhood lead exposure. The results emphasize the need for ongoing surveillance, stricter enforcement of lead-related regulations, and public health initiatives specifically designed for high-risk communities. Future research should investigate long-term health outcomes, the cost-effectiveness of interventions, and the impact of maternal and perinatal exposures on early-life BLL increases.

Georgia's experience demonstrates both the successes of national policy interventions in reducing overall lead exposure and the ongoing challenges posed by region-specific sources that require locally adapted control measures.

5. Conclusions

This study provides the first extensive evaluation of the national blood lead screening program in Georgia, highlighting both the achievements of current policy initiatives and the necessity for ongoing efforts. The observed reduction in elevated BLLs is promising and reflects progress in addressing environmental lead hazards.

However, the enduring exposure issues in western regions like Adjara and Guria indicate the need for region-specific interventions and deeper investigations into local sources of exposure. Tackling this public health challenge requires continuous multi-sectoral collaboration, sustained monitoring, and evidence-based policymaking. Future investigations should aim to merge environmental sampling, socioeconomic analysis, and neurodevelopmental follow-up to foster a comprehensive understanding of lead's effects and enhance child health outcomes throughout the nation

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A. and T.M.; Methodology, S.A.; Formal Analysis, S.A.; Investigation, S.A. and T.M.; Data Curation, T.M.; Writing - Original Draft Preparation, S.A.; Writing - Review & Editing, S.A., L.S., Z.K., W.M.C., and T.M.; Visualization, S.A.; Supervision, L.S., T.M., Z.K., W.M.C., Project Administration, T.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Emory University through a National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the use of de-identified, anonymized surveillance data collected as part of routine national public health programs. No personal identifiers were accessible to researchers, and the analysis posed no risk to participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was waived due to the use of fully anonymized surveillance data collected as part of routine national screening programs. No personal identifiers were accessible to researchers.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy and ethical restrictions. The data are owned by the National Center for Disease Control and Public Health of Georgia and were provided for this analysis under a data sharing agreement.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the National Center for Disease Control and Public Health of Georgia for providing access to the surveillance data and the healthcare workers who participated in the national screening program.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BLL |

Blood Lead Level; |

| CDC |

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; |

| IHME |

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation; |

| LMICs |

Low- and Middle-Income Countries; |

| NCDC |

National Center for Disease Control and Public Health; |

| SD |

Standard Deviation; |

| UNICEF |

United Nations Children’s Fund; |

| WHO |

World Health Organization. |

References

- Pure Earth, UNICEF. The Toxic Truth: Children’s Exposure to Lead Pollution Undermines a Generation of Potential; UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/reports/toxic-truth (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Needleman, H.L. Lead poisoning. Annu. Rev. Med. 2004, 55, 209–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Global Burden of Disease Study 2021 (GBD 2021): Lead Exposure Estimates 1990–2021. Available online: https://ghdx.healthdata.org/record/ihme-data/gbd-2021-lead-exposure-estimates-1990-2021 (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- World Health Organization. Exposure to Lead: A Major Public Health Concern; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240112384 (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Blood Lead Reference Value. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/data/blood-lead-reference-value.htm (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- World Health Organization. Lead Poisoning and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/lead-poisoning-and-health (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- UNICEF Georgia. National Survey on Blood Lead Levels in Children in Georgia; UNICEF: Tbilisi, Georgia, 2019; Available online: https://www.unicef.org/georgia/reports/national-survey-blood-lead-levels-children (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Ruadze, E.; Leonardi, G.S.; Saei, A.; Khonelidze, I.; Sturua, L.; Getia, V.; Crabbe, H.; Marczylo, T.; Lauriola, P.; Gamkrelidze, A. Reduction in blood lead concentration in children across the Republic of Georgia following interventions to address widespread exceedance of reference value in 2019. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laycock, A.; Chenery, S.; Marchant, E.; Crabbe, H.; Saei, A.; Ruadze, E.; Watts, M.; Leonardi, G.S.; Marczylo, T. The use of Pb isotope ratios to determine environmental sources of high blood Pb concentrations in children: A feasibility study in Georgia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 15007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rylander, C.; Anda, E.E.; Cirtiu, C.M.; Jankhoteli, T.; Dzotsenidze, N.; Ghetia, V.; Adamia, E.; Imnadze, P.; Manjavidze, T. Blood lead levels in children 5 to 7 years of age from the Republic of Georgia: A feasibility study on lead surveillance using volumetric absorptive microsampling. Environ. Health Perspect. 2025, 133, 057003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ericson, B.; Hu, H.; Nash, E.; Ferraro, G.; Sinitsky, J.; Taylor, M.P. Blood lead levels in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e145–e153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kharabadze, M.; Gabunia, M.; Nemsadze, K. Lead exposure sources in western Georgia: Case review and laboratory investigation. Georgian Med. News 2022, 332, 15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Update of the blood lead reference value—United States, 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 774–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haefliger, P.; Mathieu-Nolf, M.; Lociciro, S.; Templeton, M. Global lead exposure prevention strategy: WHO’s 2023 roadmap. Environ. Health 2023, 22, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.-M.; Jiao, X.-T.; Zhang, J.; Gao, Z.-Y.; Cao, J.; Liu, J.-X.; Yang, Y.-L.; Yan, C.-H. Prevalence and risk factors of elevated blood lead levels in 0–6-year-old children: A national cross-sectional study in China. Front. Public Health 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rees, N.; Fuller, R. The Toxic Truth 2.0: 2022 Update on Global Childhood Lead Exposure; Pure Earth & UNICEF: New York, NY, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.pureearth.org/publications/the-toxic-truth-2022/ (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Upadhyay, K.; et al. Estimation of the pooled mean blood lead levels of Indian children: Evidence from systematic review and meta-analysis. Toxicol. Rep. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

Ministerial Order No. 01-148/o; Ministry of Internally Displaced Persons from the Occupied Territories, Labour, Health and Social Affairs of Georgia. State Standard for Clinical Management: Early Detection and Management of Toxic Lead Exposure in Children. Tbilisi, Georgia, 2019.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).