Submitted:

21 January 2026

Posted:

22 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

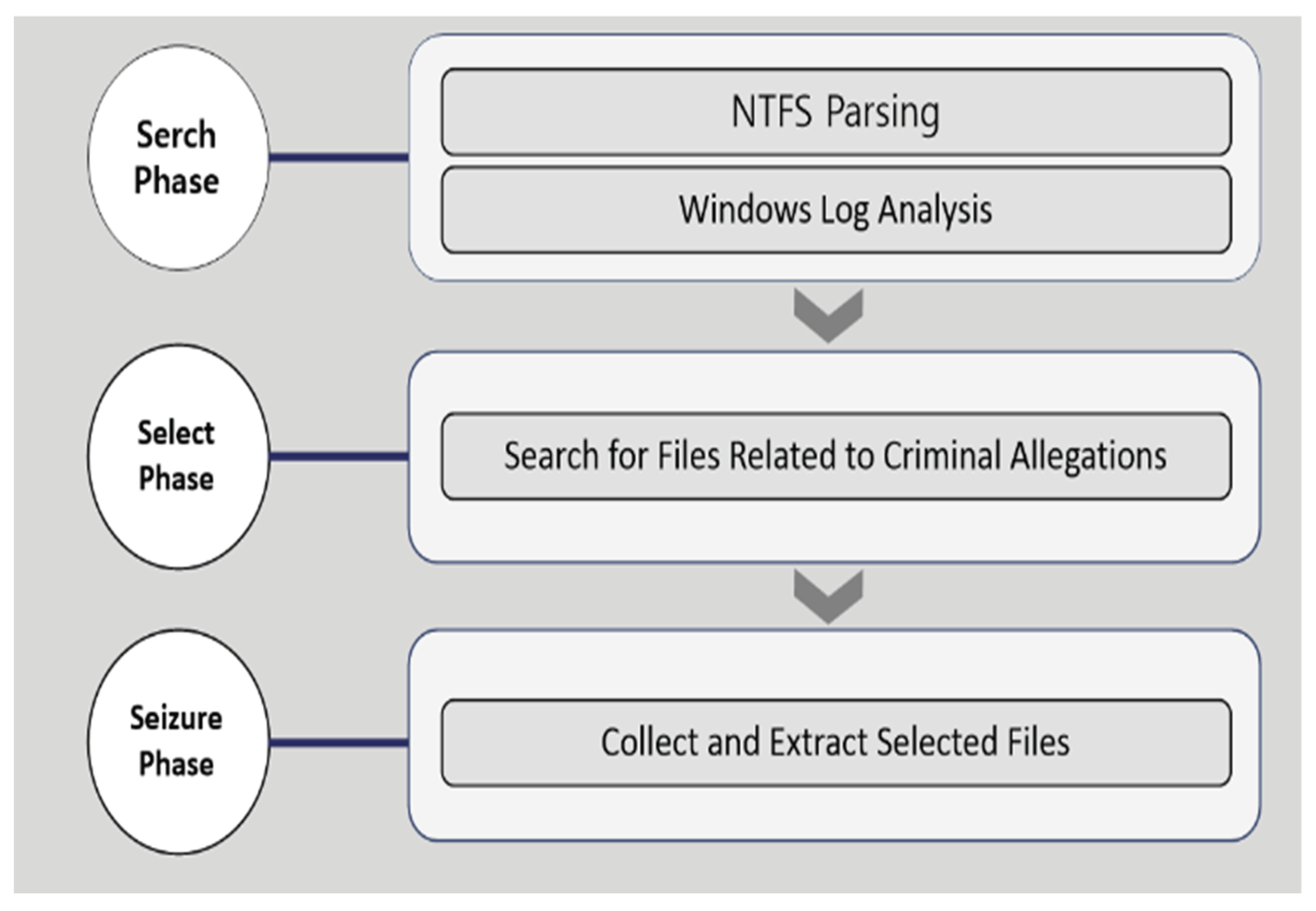

3. Evaluation Model and Data Set Development

3.1. Evaluation Model Disign

3.2. Evaluation Model Disign

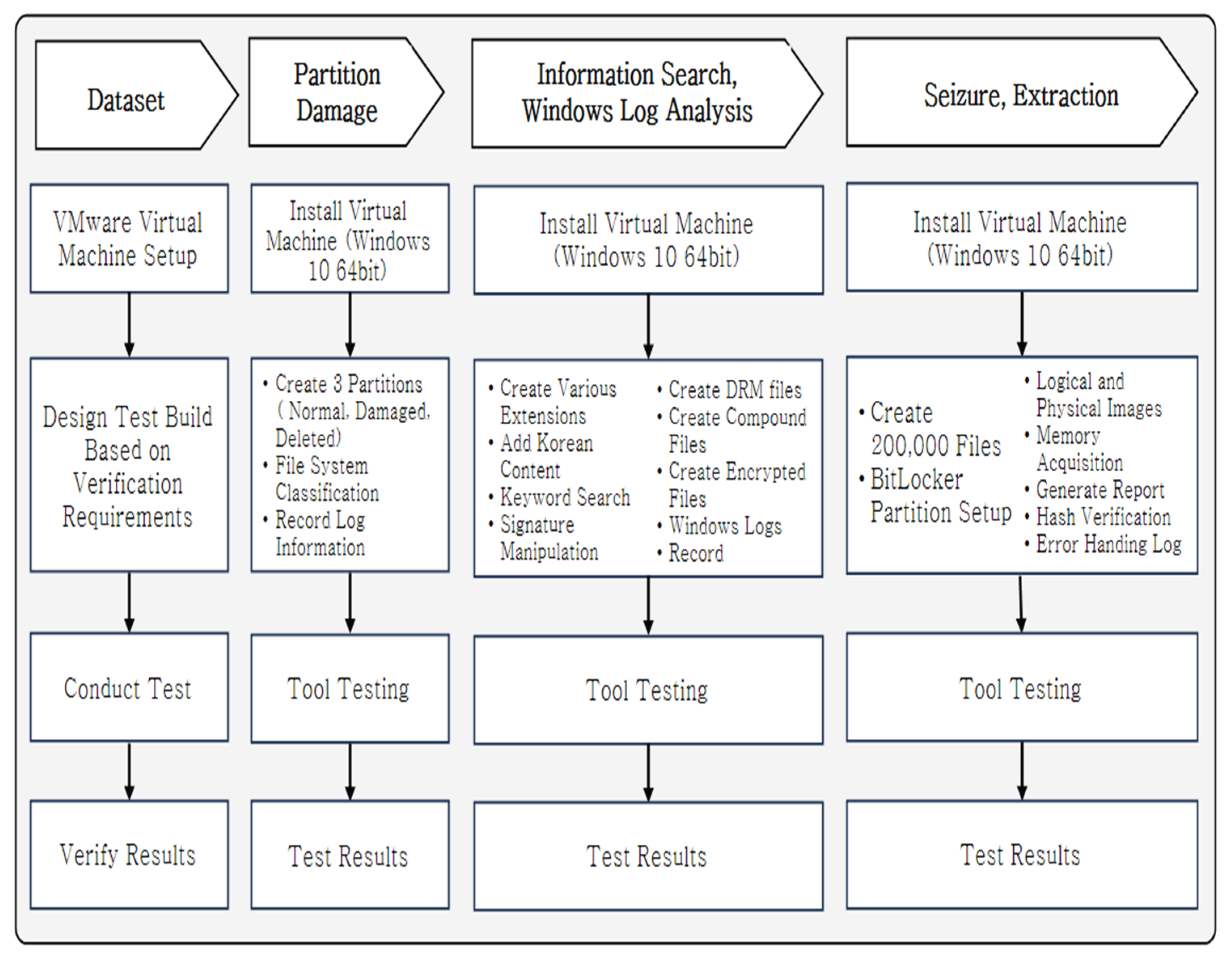

3.3. Dataset Development

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Search Phase

4.1.1. NTFS Parsing

4.1.2. File-and Folder-Access Log Analysis

4.1.3. Application-Execution Log Analysis

4.1.4. Data-Transmission Log Analysis

4.1.5. Internet Search Log Analysis

4.1.6. Suspicious-Activity Log Analysis

4.2. Search Phase

4.2.1. File-and Folder-Name Search

4.2.2. File-and Folder-Name Search

| No. | File Type | Tool | |||||

| A | B | C** | D | E* | F | ||

| 1 | cell | - | □ | O | - | O | - |

| 2 | csv | - | O | O | - | O | - |

| 3 | doc | - 1 hit |

- 2 hits |

O | - | O | - |

| 4 | docx | - 1 hit |

- 2 hits |

O | - | O | - |

| 5 | hwp | - | O | O | - | O | - |

| 6 | hwpx | - | - | - | - | O | - |

| 7 | - | O | O | - | O | - | |

| 8 | ppt | - 1 hit |

O | O | - | O | - |

| 9 | pptx | □ | O | - | O | - | |

| 10 | rtf | - 1 hit |

- 2 hits |

- | - | O | - |

| 11 | show | - | □ | - | - | O | - |

| 12 | txt | - | □ | O | - | O | - |

| 13 | xls | - | O | O | - | O | - |

| 14 | xlsx | - | O | O | - | O | - |

4.2.3. File-Header Classification

4.2.4. File-Header Classification

4.2.5. Encrypted File Identification

| No. | File Type | Tool | |||||

| A | B** | C | D | E* | F | ||

| 1 | doc | - | O | - | - | O | - |

| 2 | docx | - | O | O | - | O | - |

| 3 | hwp | - | - | - | - | O | - |

| 4 | ppt | - | - | - | - | O | - |

| 5 | pptx | - | O | O | - | O | - |

| 6 | 7z | - | O | - | - | - | - |

| 7 | tar | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 8 | zip | - | O | - | - | O | - |

| No. | Evaluation Item | File Type | Tool | |||||

| A | B** | C* | D | E | F | |||

| 1 | Document Files | cell | - | - | O | - | - | - |

| 2 | csv | - | O | O | - | - | - | |

| 3 | doc | - | O | O | - | - | - | |

| 4 | docx | - | O | O | - | - | - | |

| 5 | hwp | - | O | O | - | - | - | |

| 6 | hwpx | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 7 | - | O | O | - | - | - | ||

| 8 | ppt | - | O | O | - | - | - | |

| 9 | pptx | - | O | O | - | - | - | |

| 10 | rtf | - | O | O | - | - | - | |

| 11 | show | - | O | O | - | - | - | |

| 12 | txt | - | O | O | - | - | - | |

| 13 | xls | - | O | O | O | - | - | |

| 14 | xlsx | - | O | O | - | - | - | |

| 15 | Compound Files | pst | - | O | O | O | O | - |

| 16 | ost | - | O | O | O | O | - | |

| 17 | sqlite | - | O | - | - | O | - | |

| 18 | db | - | O | - | - | O | - | |

| 19 | 7z | - | - | O | O | - | - | |

| 20 | zip | - | - | O | O | - | - | |

| 21 | Tar | - | - | O | O | - | - | |

| 22 | egg | - | - | O | - | - | - | |

| 23 | rar | - | - | O | O | - | - | |

| 24 | Image Files (EXIF Support) |

awd | - | - | O | - | O | - |

| 25 | psd | - | O | O | - | O | - | |

| 26 | dwg | - | - | O | - | O | - | |

| 27 | bmp | - | O | O exif |

O exif |

O | - | |

| 28 | png | - | O exif |

O exif |

O exif |

O exif |

- | |

| 29 | psp | - | - | O exif |

O exif |

- | - | |

| 30 | jpeg | - | - | O exif |

O exif |

O exif |

- | |

| 31 | jpg | - | O exif |

O exif |

O exif |

O exif |

- | |

4.3. Seizure Phase

4.3.1. File-and Folder-Name Search

4.3.2. Extraction Evaluation

4.4. SSI Evaluation

4.5. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Presidential Decree; Republic of Korea. Regulations on Mutual Cooperation Between Prosecutors and Judicial Police Officers and General Investigative Principles, Article 41, Paragraphs 1, 2, 3. 1 Nov 2023. Available online: https://www.kicj.re.kr/board.es?mid=a20201000000&bid=0029&list_no=12687&act=view#wrap.

- Desktop Windows Version Market Share Republic of Korea. StatCounter Global Stats. Available online: https://gs.statcounter.com/os-version-market-share/windows/desktop/south-korea (accessed on Nov. 27 2023).

- Computer Forensics Tools & Techniques Catalog - Tool Search. Available online: https://toolcatalog.nist.gov/search/index.php (accessed on Dec. 16 2023).

- Desktop Hypervisor Solutions | VMware. Available online: https://www.vmware.com/products/desktop-hypervisor/workstation-and-fusion (accessed on Oct. 06 2024).

- Watson, S.; Dehghantanha, A. Digital forensics: the missing piece of the cloud puzzle. Computer Fraud & Security 2016, vol. 2016(no. 6), 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Montasari, R. Digital forensics: Challenges and opportunities for future studies. International Journal of Engineering & Technology 2019, vol. 7(no. 2.28), 125–135. [Google Scholar]

- Nawaz, F. Artificial intelligence-enabled digital forensics for cloud platforms. IEEE Access 2021, vol. 9, 129796–129813. [Google Scholar]

- Yoon, S.; Lee, S. A study on digital evidence automatic screening system. J. Digit. Forensics KDFS 2020, vol. 14(no. 3), 239–251. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, G. A digital forensic analysis for directory in Windows file system. J. Korea Soc. Digit. Ind. Inf. Manag. 2015, vol. 11(no. 2), 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y. A study on field detection techniques for non-searchable email attachments. M.S. thesis, Grad. Sch. Converg. Sci. Tech., Seoul Nat. Univ., Seoul, Korea, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, T. -R.; Shin, S. -U. Reliability verification of evidence analysis tools for digital forensics. J. Korea Inst. Inf. Secur. Cryptol. 2011, vol. 21(no. 3), 165–176. [Google Scholar]

- Ham, J.; Joshua, I. J. A study on the comparison of modern digital forensic imaging software tools. J. Korean Inst. Internet Broadcast. Commun. 2019, vol. 19(no. 6), 15–20. [Google Scholar]

- Harbawi, M.; Varol, A. The role of artificial intelligence in digital forensics. 2017 International Conference on Computer Science and Engineering (UBMK), 2017; IEEE; pp. 110–115. [Google Scholar]

- Tassone, C. Forensic examination of cloud storage services in Android. Digital Investigation 2016, vol. 16, 43–54. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Hur, G.; Lee, S. Development of a set of data for verifying partition recovery tool and evaluation of recovery tool. J. Korea Inst. Inf. Secur. Cryptol. 2017, vol. 27(no. 6), 1397–1404. [Google Scholar]

- Martini, B.; Choo, K.-K. R. Cloud storage forensics: ownCloud as a case study. Digital Investigation 2013, vol. 10(no. 4), 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quick, D.; Choo, K. -K. R. Big forensic data reduction: Digital forensic images and electronic evidence. Clust. Comput. 2016, vol. 19(no. 2), 723–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Case, A. Memory forensics: The path forward. Digital Investigation 2017, vol. 20, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. -S.; Lee, S. Development of Windows forensic tool for verifying a set of data. J. Korea Inst. Inf. Secur. Cryptol. 2015, vol. 25(no. 6), 1421–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsman, G. Framework for reliable experimental design (FRED): A research framework to ensure the dependable interpretation of digital data for digital forensics. Computers & Security 2018, vol. 73, 294–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D. A quality evaluation model based on ISO/IEC 9126 for digital forensic tools. M.S. thesis, Grad. Sch. Softw. Specialization, Soongsil Univ., Seoul, Korea, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Saleh, M. Cloud forensics: A research perspective. 9th International Conference on Innovations in Information Technology, 2013; IEEE; pp. 66–71. [Google Scholar]

- Alqahtany, S. Forensic investigation of cloud storage services in the Internet of Things. Digital Investigation 2019, vol. 29, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Lyle, J. R.; Guttman, B. Introduction to the NIST digital forensic tool verification system. Rev. KIISC 2016, vol. 26(no. 5), 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Ab Rahman, N. H.; Choo, K.-K. R. A survey of information security incident handling in the cloud. Computers & Security 2015, vol. 49, 45–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daryabar, F. Investigation of memory forensics of VMware workstation on Windows, Linux and Mac. Digital Investigation 2017, vol. 22, 566–578. [Google Scholar]

- CFReDS Portal. Available online: https://cfreds.nist.gov/ (accessed on Dec. 14 2023).

- Damshenas, M. Forensics investigation challenges in cloud computing environments. 2012 International Conference on Cyber Security, Cyber Warfare and Digital Forensic, 2012; IEEE; pp. 190–194. [Google Scholar]

- Ruan, K. Cloud forensics definitions and critical criteria for cloud forensic capability: An overview of survey results. Digital Investigation 2013, vol. 10(no. 1), 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosting various seminars related to digital forensics from 2001 to the present, DFRWS. Available online: https://dfrws.org/ (accessed on Dec. 14 2023).

- Dykstra, J.; Sherman, A. T. Acquiring forensic evidence from infrastructure-as-a-service cloud computing. Digital Investigation 2012, vol. 9, S90–S98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, B.; Choo, K.-K. R. An integrated conceptual digital forensic framework for cloud computing. Digital Investigation 2012, vol. 9(no. 2), 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forensic Focus. Available online: https://www.forensicfocus.com/ (accessed on Dec. 13 2023).

- Zia, T. Digital forensics for cloud computing: A roadmap for future research. Digital Investigation 2016, vol. 19, 34–46. [Google Scholar]

- Koo, K. Development of a mobile personal software platform. ETRI J. 2009, vol. 24(no. 4), 31–32. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, F. Digital Forensic Evidence Examination. IEEE Security & Privacy 2020, vol. 8(no. 2), 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L. AI-powered digital forensics: Opportunities, challenges, and future directions. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2021, vol. 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, D.; Kipper, G. Virtualization and Forensics: A Digital Forensic Investigator’s Guide to Virtual Environments; Syngress, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan, S. Digital forensic research: current state of the art. CSI Transactions on ICT 2013, vol. 1(no. 1), 91–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aminnezhad, A. Cloud forensics issues and opportunities. International Journal of Information Processing and Management 2013, vol. 4(no. 4), 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKemmish, R. What is forensic computing? In Australian Institute of Criminology trends & issues in crime and criminal justice; 2019; Volume no. 118, pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, M. Digital evidence in cloud computing systems. Computer Law & Security Review 2010, vol. 26(no. 3), 304–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J. A Comparative Study of Digital Forensic Evidence Collection Methods for Cloud Storage Services. Digital Investigation 2020, vol. 33, 301–314. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, S. Artificial Intelligence for Digital Forensics: Challenges and Applications. IEEE Access 2020, vol. 8, 119697–119707. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.; Hong, S. The Challenges of Cloud Forensics in South Korea. Journal of Digital Forensics, Security and Law 2019, vol. 14(no. 4), 45–57. [Google Scholar]

- Chung, H. Digital forensic investigation of cloud storage services. Digital Investigation 2012, vol. 9(no. 2), 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B. Automated Forensic Analysis Framework for Cloud Computing Environment. Journal of Security Engineering 2018, vol. 15(no. 6), 435–444. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, R. The application of digital forensic readiness to cloud computing. IFIP International Conference on Digital Forensics, 2013; Springer; pp. 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, M.; Kim, J. Development of Digital Forensics Standard Model for Cloud Computing Services. Journal of the Korea Institute of Information Security & Cryptology 2018, vol. 28(no. 2), 403–413. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, T. Building Digital Forensic Investigation Framework for Cloud Computing. International Journal of Network Security 2020, vol. 22(no. 6), 978–985. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Category | Project/Research | Format |

| 1 | Institution | Computer Forensic Reference Data Set (CFReDS) Project |

E01, DD |

| 2 | Computer Forensic Tool Testing Project | E01, DD | |

| 3 | Digital-forensic-tool Testing (DFTT) | DD | |

| 4 | Naval Postgraduate School Digital Forensics Corpus (NPS Corpora) | File Dump, E01, DD, packet dump File |

|

| 5 | ForensicKB | E01, DD, File | |

| 6 | Prior Research |

ISO/IEC 9126-based Quality Evaluation Model for Digital Forensic Tools |

Live |

| 7 | Reliability Evaluation through Verification of the Analytical Functions of Computer Forensic Tools | DD | |

| 8 | Development of a Verification Dataset for Windows Forensic Tools | VMDK | |

| 9 | Configuration of a Computer Forensic Tool Verification Image Suitable for Domestic Environments |

||

| 10 | Reliability Verification of Evidence Analysis Tools for Digital Forensics | E01, DD, File |

| numbers | Verification requirements |

| 1 | Recognizes the specified file system and analyzes the metadata. |

| 2 | Recognizes and analyzes all files registered in the file system. |

| 3 | Analyze accurate time information for all files and folders. |

| 4 | Recognizes and processes fragmented files. |

| 5 | Recognizes and analyzes all files and folders registered in the GUID partition. |

| 6 | Handles and recognizes incorrect partition information. |

| 7 | Shows the location on the digital source for all files. |

| 8 | Detects hidden partitions and recognizes all files and folders |

| 9 | Analytical tools provide data extraction and analysis functions for evidence media to identify evidence. |

| 10 | Analysis tool functions always output the same results when the same input data is given in the same environment. |

| 11 | Analysis tool functions keep input data revisions to a minimum and report modifications when they occur. |

| 12 | The analysis tool supports at least one file system and accurately recognizes the file systems and metadata supported by the tool. |

| 13 | The analysis tool records a log of events performed. |

| 14 | Analysis tool functions report errors that occurred during execution. |

| Numbers | Verification requirements |

| 1 | The results of considering to the query are the same as the three matching the query. |

| 2 | Navigation is possible with one or more character encodings. |

| 3 | You can explore strings in Slack space. |

| 4 | If you specify a specific area within the evidence disk as the search range, results are output only at that point. |

| 5 | You can use regular expressions to navigate. |

| 6 | You can search with Hash Set (Hash Set). |

| 7 | You can explore the full spectrum of digital sources. (including slack, parity, deleted areas, and between files) |

| 8 | You can extract any file from a supported file system. |

| 9 | If a reorganization related error occurs while extracting a file, an error report is possible. |

| 10 | The collected files are collected to the original. |

| 11 | When extracting a file, unreadable parts are potentially as extractable data. |

| 12 | Users are considering when storage space is low. |

| 13 | Korean language support is available. |

| 14 | Invented the file system information contained in the validation data. |

| 15 | Preserves hash values (minimum MD5, SHA 1) for all files included in validation data. |

| 16 | Combating the fragmentation status and count of some of the files included in the validation data. |

| 17 | Validates keyword searches in the NTFS file system. |

| 18 | Validates the ability to extract data from NTFS deleted files. |

| 19 | Verify the NTFS automatic detection feature. |

| 20 | Verify the data extraction function in the basic data carving function. |

| 21 | If a subset of the string search function is specified, results are output only from that subset. |

| 22 | A limit on the number of matches is applied when searching for sorted/unsorted subsets in a string search. |

| 23 | The screen is displayed according to the specified text direction. |

| 24 | Synonym search is supported. |

| 25 | When performing a fuzzy search, it must match a close misspelling (close misspelling) in the query string. |

| 26 | When performing a phonetic search (phonetic search), it must match words pronounced the same as the query string. |

| 27 | If you provide a predefined query, the response returned must be the same set of matches for the query. |

| 28 | It must support logical operations such as And, or, and not. |

| 29 | Analytical tools should provide data extraction and analysis capabilities to identify evidence. |

| 30 | You must be able to browse regardless of capitalization. |

| numbers | Verification content |

| 1 | Log file analysis must be able to recognize at least one or more log file formats and provide a function to search and filter desired events. |

| 2 | It is necessary to be able to analyze time information on internal data according to the environment in which the original was created. |

| 3 | System/user settings information analysis must be able to analyze information about the operating system, information about users, and information about installed applications. |

| 4 | Log file analysis must be able to accurately recognize and report on various log file formats through documentation provided by the tool (including usage, purpose, operating mechanism, and system requirements). |

| numbers | Verification content |

| 1 | The deleted file recovery function must support the recovery function in a file system confirmed by documents provided by the tool (a set of materials describing usage, purpose, operation, system requirements, etc.). |

| 2 | The deleted file recovery function must identify all deleted file system objects that can be recovered from metadata maintained after the file system object has been deleted. |

| 3 | The deleted file recovery function must report errors that occurred in constructing recovered objects. |

| 4 | The deleted file recovery function must configure a recovered object for each deleted file system object from the remaining metadata. |

| 5 | Each recovered object must include all unallocated data blocks identified in the remaining metadata. |

| 6 | Each recovered object must consist only of data blocks from the deleted block pool. |

| 7 | If the deleted file recovery function generates estimated content, the recovered object must be composed of data blocks from the original file system object identified in the remaining metadata. |

| 8 | If the deleted file recovery function generates estimated content, any data blocks in the recovered object must be organized in the same logical order as the original file system object identified in the remaining metadata. |

| 9 | If the deleted file recovery function generates estimated content, the recovered object must consist of the same number of blocks as the original file system object. |

| 10 | Verify the FAT deleted file extraction function. |

| 11 | Verify the NTFS deleted file extraction function. |

| 12 | Verify the basic data carving function. |

| numbers | Verification content |

| 1 | The analysis tool must output the results of the analysis performed in the form of a report. |

| 2 | The hash values of all files belonging to the verification data are preserved. At this time, the hash function uses at least MD5 and SHA1. |

| 3 | Analysis tool functions must always output the same results when given the same input data in the same environment. |

| 4 | Timeline analysis must be able to extract information such as creation, modification, access time, and ownership of a file through MAC (modified, modified, change of status) time analysis, and must be able to sort and list in chronological order using this information. |

| 5 | Analysis tool functions must report errors that occurred during execution. |

| No. | Phase | Evaluation Item |

| 1 | Search | • NTFS Parsing (BitLocker analysis, Partition MFT, VBR (MBR, GPT) deletion, damage analysis, $MFT, $MFT Entry, $Standard_Information, $FileName, $MFT deletion information) • File- and Folder-access Log Analysis (JumpList, Link File, Shellbag MRU, Windows.edb, ActivitiesCache.db, etc.) • Application-execution Log Analysis (Prefetch, ActivitiesCache.db, AmCache, SRUMDB) • Data-transmission Log Analysis (Setupapi.log, Registry, EventLog, AmCache) • Information Search Log Analysis (Chrome, Edge, Whale: History, Download, Password, Cache, Cookies) • Suspicious-activity Log Analysis (EventLog: System ON/OFF, User Account Changes, System Time Changes) |

| 2 | Select | • Information Search (File and folder-name search, file keyword analysis, file-header classification, DRM files, encrypted files, etc.) |

| 3 | Seizure | • Collection and Extraction (Logical image, physical image, memory acquisition, report generation, hash verification, error handling report) |

| No. | Category | Tool Name | Release and First Version |

| 1 | Commercial | A | 2019 |

| 2 | Non-commercial | B | 2010 |

| 3 | Commercial | C | 1995 |

| 4 | Commercial | D | 2011 |

| 5 | Commercial | E | 2011 |

| 6 | Commercial | F | 2021 |

| Symbol | Description |

| O | Meets all details of the verification items |

| □ | Meets three or more details of the verification items |

| △ | Meets three or more details of the verification items but requires manual analysis |

| - | Does not meet any detail of the verification items |

| No. | Type | Specifications | ||

| 1 | Laptop | CPU | Intel Core i5-1035G4 CPU @ 1.10 GHz 1.50 GHz | |

| RAM/HDD | 8 GB/Mtros SSD NVMe M.2 | |||

| 2 | Virtual Machine | Windows | Windows 10 PRO 64-bit 22H2 NTFS configuration | |

| Version | VMware Workstation PRO 17.5 | |||

| CPU/RAM | 4 Core/4 GB | |||

| Phase | Parameter | Description | |

| Search | Portable | Verify the execution and automated analysis functionality of portable GUI-based tool selection | |

| BitLocker identification and support for decryption after entering the password | Verify support for recognizing BitLocker-encrypted partitions on Windows and unlocking and decrypting them after entering the recovery key or password | ||

| Partition Damage | Verify support for recovering deleted or damaged partitions master boot record (MBR), GUID partition table (GPT) (MFT, volume boot record (VBR)) | ||

| $MFT Analysis | Verify support for recognizing NTFS and parsing $MFT. ($MFT structure parsing, size information) |

||

| $MFT attribute timestamp analysis ($SI, $FN) | Verify recognition of $MFT and support for file-information and metadata analysis. ($SI creation, modification, access, MFT modification, attribute flag information, $FI parent directory file reference address, creation, modification, access, MFT modification, file allocated size, actual file size, attribute flag, name length, name type, name information support) |

||

| $MFT Deletion | Verify deleted record information in $MFT entries. (Unallocated file, file name, creation, modification, access) |

||

| JumpList | Verify document file-access records. (Analysis count, file name, link creation, link modification, link access, target creation, target modification, target access, volume name, volume S/N, size, path, original path) |

||

| Link File | Verify document file-access records. (Analysis count, file name, link creation, link modification, link access, target creation, target modification, target access, volume name, volume S/N, size, path, original path) |

||

| Shellbag MRU | Verify folder-access records. (Analysis count, folder name, visit time, creation time, access time, modification time, path, original path) |

||

| ActivitesCache.db | Verify document file-access records. (Analysis count, display text, last modification time, app ID, path, original path) |

||

| Windows.edb | Verify document file records. (Document count, file name, creation, modification, file type, file path, content, original path) |

||

| Volume Shadow | Verify backup records of three documents. (Analysis count, file name, creation time, original path) |

||

| $Logfile | Verify document file records (Analysis count, events, original path) |

||

| $UsnJrul | Verify document file records (Analysis count, events, original path) |

||

| Thumbnail.db | Verify thumbnail cache image file records. (Image name, original path) |

||

| $Recycle.bin | Verify records of deleted files (File count, $R, $I) |

||

| Prefetch | Verify records of executed programs. (Analysis count, program name, execution time, execution count, path, original path) |

||

| Program Execution | Verify records of executed programs. (Analysis count, program name, execution time, execution count, user, path, original path) |

||

| AmCache | Verify record of executed program. (Key time, key name, name, publisher, size, original path) |

||

| SRUMDB | Verify resource-usage records of executed programs. (Creation time, program, original source) |

||

| External Storage Device | Registry | Verify external storage device records. (Model name, first connection time, last connection time, disconnection time, serial number, volume name, original path) |

|

| Setupapi.log | Verify external storage device records. (Model name, first connection time, original path) |

||

| EventLog | Verify external storage device records. (Event ID, connection/disconnection time, device information, original path) |

||

| Network Connection |

Wireless | Verify wireless network records. (Network name, last connection time, original path) |

|

| Wired | Verify wired-network records. (Adapter name, IP, Subnet mask, DHCP, original path) |

||

| Web Browser (Chrome, Edge, Whale) |

Web Access | Verify internet-access records. (Analysis count, accessed website, access time, original path) |

|

| Search Terms | Verify web search term records. (Analysis count, search terms, access time, original path) |

||

| Downloads | Verify records of files downloaded from the internet. (Analysis count, website, downloaded file, download time, original path) |

||

| Passwords | Verify saved web ID/password records. (Save count, creation time, website, original path) |

||

| Cache | Verify web-cache file records. (Analysis count, cache file, access time, website, original path) |

||

| Cookies | Verify internet cookie records. (Analysis count, cookie file, access time, website, original path) |

||

| EventLog | System ON/OFF |

Verify system ON/OFF records. (ON time, OFF time, computer name, EventID, original path) |

|

| User Account Changes | Verify system user account change information. (Account name, event time, EventID, original path) |

||

| System Time Changes |

Verify system time change information. (Previous time, new time, user ID, EventID, original path) |

||

| Select | File-name Search | Verify search of Korean file names. “Network Diagram.pptx, Risk Burden.pdf, Office Lease Contract.hwp” Verify support for logical operators AND, OR. Verify support for regular-expression searches. “Forensic[[, -]Science, Sungkyunkwan[0-9가-힣]University, http://www\.[가-힣]+\.com, C:\\Images\\KakaoTalk\\.gif, 02[-) ]*3290-1212” |

|

| Keyword Analysis | Verify search for keywords “forensics, digital forensics, selection, tools, Sungkyunkwan University” in document file extensions. (cell, csv,doc,docx,hwp,hwpx,pdf,pptx,rtf,show,txt,xls,xlsx) |

||

| File-header Identification | Documents | cell, csv, doc, docx, hwp, hwpx, pdf, pptx, rtf, show, txt, xls, xlsx. | |

| Digital Rights Management (DRM) | Verify the identification of Fasoo, SoftCamp, and Markany. | ||

| Encrypted Files | Verify the identification of doc, docx, hwp, ppt, pptx, 7z, tar, and zip. | ||

| Preview | Documents | cell, csv, doc, docx, hwp, hwpx, pdf, pptx, rtf, show, txt, xls, xlsx. | |

| Compound Files | Verify the identification of pst, ost, sqlite, db, 7z, zip, tar, egg, and rar. | ||

| Images | Verify the identification of awd, psd, dwg, bmp, png, psp, jpeg, and jpg. | ||

| Seizure | Logical Image | Verify support for logical image acquisition. | |

| Physical Image | Verify support for physical image acquisition. | ||

| Memory Collection | Verify support for memory-dump collection. | ||

| Report | Verify the generation of a report for logical image acquisition (file name, path). | ||

| Hash Verification | Verify the inclusion of hash information in the report and support for calculating at least two hashes. | ||

| Error Handling Log | Support for logging errors occurring in the tool and other logs. | ||

| Verification Item | File Name | File Size | File Hash Value (MD5, SHA1) |

| Search | MBR-000002.vmdk | 17 GB | d666ad43460de6f9955e4e045b10ba8e 54608a7ea3437e3ea6952b5722cfe4baa52fa2da |

| Basic Sample Machine-cl1.vmdk | 22.9 GB | 62ac1cfdea9a1d3b13395c6eb9c9ecc8 e3e33f24909b56a5fc57491b17621310d8a76a66 |

|

| Search, Select | Windows 10 x64(1). vmdk | 61.9 GB | d666ad43460de6f9955e4e045b10ba8e 54608a7ea3437e3ea6952b5722cfe4baa52fa2da |

| Seizure | Basic Sample Machine-cl1.vmdk | 25.3 GB | b11f85b705402c86cce19ea3ee8dec0b f2925883e67c719f01ae57762d82cd8699a1d206 |

| No. | Evaluation Item | Tool | |||||

| A | B** | C* | D | E | F | ||

| 1 | BitLocker Support | - | - | - | O | - | - |

| 2 | $MFT Analysis | O | O | O | O | O | O |

| 3 | $MFT Recognition | - | O | □ | □ | □ | - |

| 4 | MBR (VBR) Damage | - | - | - | O | - | - |

| 5 | MBR (MFT) Partition Deletion |

- | O | O | - | - | - |

| 6 | GPT (VBR) Damage | - | - | O | - | - | - |

| 7 | GPT (MFT) Partition Deletion |

- | - | O | - | - | - |

| 8 | MFT File Deletion |

- | O | O | - | O | - |

| No. | Evaluation Item | Tool | |||||

| A | B | C | D** | E* | F | ||

| 1 | JumpList | - | - | △ | □ | □ | - |

| 2 | Link File | □ | □* | △ | O | □ | □ |

| 3 | Shellbag MRU | - | □ | △ | □ | O | - |

| 4 | ActivitesCache.db | - | □ | - | O | O | - |

| 5 | Windows.edb | - | - | - | - | O | - |

| 6 | Volume Shadow | - | - | △ | - | - | - |

| 7 | $Logfile | - | - | - | - | O | - |

| 8 | $UsnJrul | - | - | - | - | O | - |

| 9 | Thumbnail.db | - | - | - | O | O | - |

| 10 | $Recycle.bin | - | O | O | - | O | - |

| No. | Evaluation Item | Tool | |||||

| A | B | C | D** | E* | F | ||

| 1 | Prefetch | □ | O | △ | O | O | □ |

| 2 | Program Execution | - | - | △ | O | O | - |

| 3 | AmCache | - | △ | △ | O | O | - |

| 4 | SRUMDB | - | □ | △ | - | O | - |

| No. | Evaluation Item | Details | Tool | ||||||

| A | B | C* | D | E** | F | ||||

| 1 | Network Connection |

Wireless | - | - | △ | O | O | - | |

| 2 | Wired | - | - | △ | - | O | - | ||

| 3 | External Storage Device | Registry | - | O | △ | O | O | - | |

| 4 | Event Log | - | - | △ | O | - | - | ||

| 5 | Setup.API | - | - | △ | △ | O | - | ||

| 6 | AmCache | - | △ | △ | O | O | - | ||

| No. | Browser | Evaluation Item | Tool | |||||

| A | B | C** | D | E* | F | |||

| 1 | Google Chrome |

Web Access | - | O | △ | O | O | - |

| 2 | Search Terms | - | O | △ | O | O | - | |

| 3 | Downloads | - | O | △ | O | O | - | |

| 4 | Passwords | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 5 | Cache | - | O | △ | - | O | - | |

| 6 | Cookies | - | O | △ | - | O | - | |

| 7 | Microsoft Edge |

Web Access | - | O | - | O | O | - |

| 8 | Search Terms | - | O | - | O | O | - | |

| 9 | Downloads | - | O | - | O | O | - | |

| 10 | Passwords | - | - | - | O | O | - | |

| 11 | Cache | - | O | - | - | O | - | |

| 12 | Cookies | - | O | - | - | O | - | |

| 13 | Naver Whale |

Web Access | - | - | - | - | O | - |

| 14 | Search Terms | - | - | - | - | O | - | |

| 15 | Downloads | - | - | - | - | O | - | |

| 16 | Passwords | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 17 | Cache | - | - | - | - | O | - | |

| 18 | Cookies | - | - | - | - | O | - | |

| No. | Evaluation Item | Tool | |||||

| A | B | C* | D** | E** | F | ||

| 1 | System ON/OFF |

- | - | △ | O | O | - |

| 2 | User Account Changes |

- | - | △ | - | - | - |

| 3 | System Time Changes |

- | - | △ | - | - | - |

| No. | Evaluation Item | Tool | |||||

| A | B | C* | D | E** | F | ||

| 1 | File Name | - | O | O | O | O | - |

| 2 | Folder Name | - | - | O | - | - | - |

| 3 | Regular Expression | - | - | - | - | □ | - |

| No. | File Type | Tool | |||||

| A | B* | C* | D | E** | F | ||

| 1 | cell | - | - | - | - | O | - |

| 2 | csv | - | - | O | - | - | - |

| 3 | doc | - | O | O | - | - | - |

| 4 | docx | - | O | O | - | O | - |

| 5 | hwp | - | O | O | - | O | - |

| 6 | hwpx | - | - | - | - | O | - |

| 7 | - | O | O | O | O | - | |

| 8 | ppt | - | O | O | - | - | |

| 9 | pptx | - | O | O | - | - | |

| 10 | rtf | - | O | O | - | 0 | - |

| 11 | show | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 12 | txt | - | O | - | O | - | - |

| 13 | xls | - | O | O | - | O | - |

| 14 | xlsx | - | O | O | - | - | - |

| No. | Software | Tool | |||||

| A | B | C | D | E* | F | ||

| 1 | Fasoo | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 3 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 4 | Softcamp | - | - | - | - | O | - |

| 5 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 6 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 7 | Markany | - | - | - | - | O | - |

| 8 | - | - | - | - | O | - | |

| 9 | - | - | - | - | O | - | |

| 10 | - | - | - | - | O | - | |

| No. | Evaluation Item | Details | Tool | |||||

| A | B | C* | D | E** | F | |||

| 1 | Logical Image | Image Format | - | - | O ctr |

O vhd |

O zip, dd |

- |

| 2 | Report | - | - | - | O Save Error |

O csv, txt |

- | |

| 3 | Time Taken for 200,000 Files | - | - | 13 min | 180 min | 34 min | - | |

| 4 | Memory Dump | Image Format | O bin |

- | - | - | O raw |

O mem |

| 5 | Report | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

| 6 | Physical Image | Image Format | - | - | O | O | O | - |

| 7 | Report | - | - | O txt |

O txt |

O txt |

- | |

| No. | Item | Tool | |||||

| A | B** | C | D | E* | F | ||

| 1 | Report Support | O | O | O | O | O | O |

| 2 | Report Format | txt, html | html, excel, text, kml, stix, tsk file |

html | txt | txt, csv, excel |

html |

| 3 | Hash Support | - | O | O | O | O | O |

| 4 | Hash Set | - | O | O | O | O | O |

| 5 | Error Handling Report | O | O | O | - | - | O |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).