Submitted:

21 January 2026

Posted:

22 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

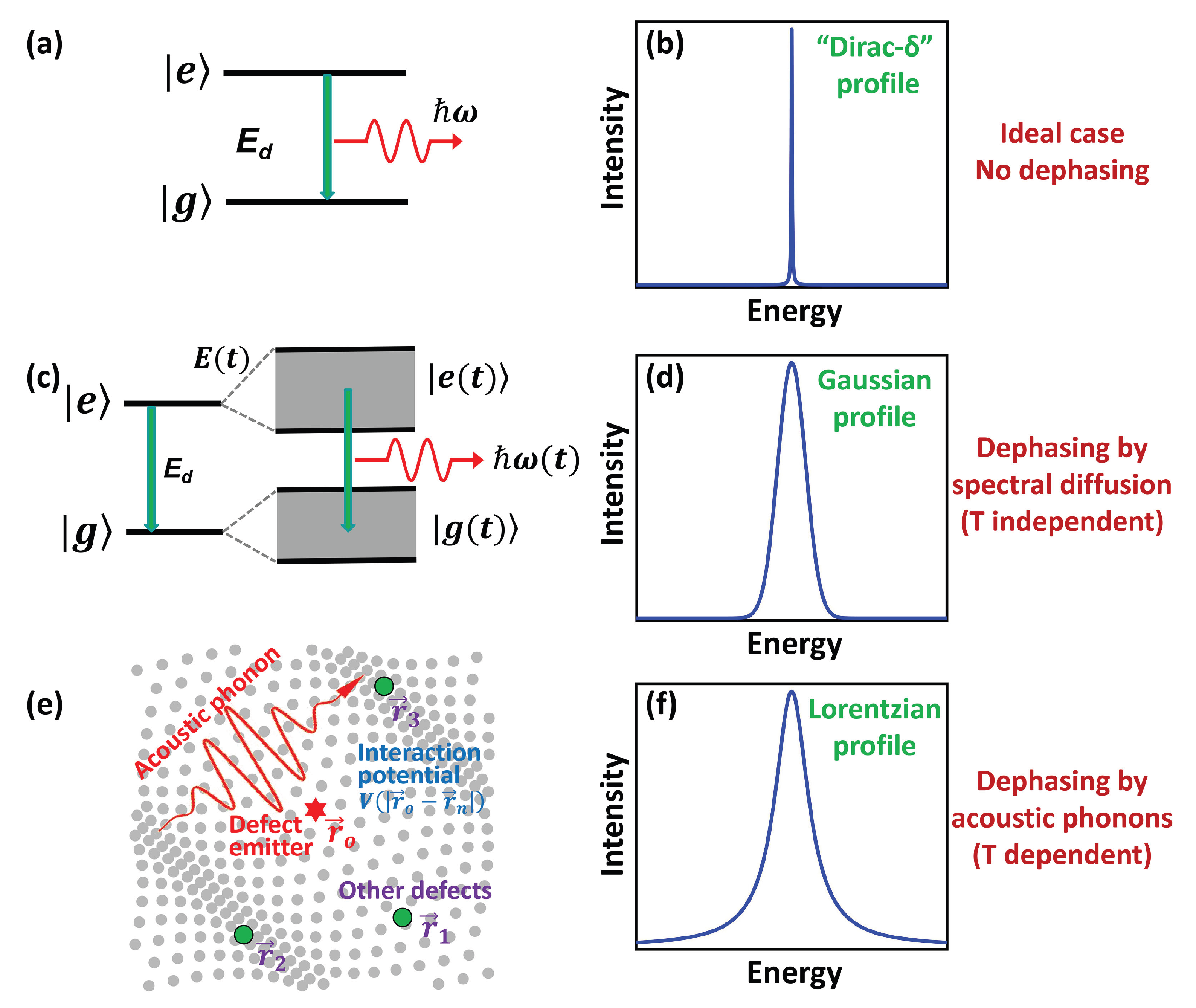

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Results and Discussion

Conclusion

References

- Aharonovich, I.; Englund, D.; Toth, M. Solid-state single-photon emitters. Nature photonics 2016, 10, 631–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y. Defect Quantum Emitters in Gallium Nitride. PhD thesis, Cornell University, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Geng, Y.; Rana, F.; Fuchs, G.D. Room temperature optically detected magnetic resonance of single spins in GaN. Nature Materials 2024, 23, 512–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, Y.; Luo, J.; van Deurzen, L.; Jena, D.; Fuchs, G.D.; Rana, F.; et al. Decoherence by Optical Phonons in GaN Defect Single-Photon Emitters. arXiv arXiv:2206.12636.

- Berhane, A.M.; Jeong, K.Y.; Bodrog, Z.; Fiedler, S.; Schröder, T.; Triviño, N.V.; Palacios, T.; Gali, A.; Toth, M.; Englund, D.; et al. Bright Room-Temperature Single-Photon Emission from Defects in Gallium Nitride. Advanced Materials 2017, 29, 1605092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geng, Y.; Jena, D.; Fuchs, G.D.; Zipfel, W.R.; Rana, F. Optical dipole structure and orientation of GaN defect single-photon emitters. ACS Photonics 2023, 10, 3723–3729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Geng, Y.; Rana, F.; Fuchs, G. GaN quantum emitters: basic physics, spin structure, and optically detected magnetic resonance (ODMR). In Proceedings of the Gallium Nitride Materials and Devices XX. SPIE, 2025; p. PC1336605. [Google Scholar]

- Berhane, A.M.; Jeong, K.Y.; Bradac, C.; Walsh, M.; Englund, D.; Toth, M.; Aharonovich, I. Photophysics of GaN single-photon emitters in the visible spectral range. Physical Review B 2018, 97, 165202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Geng, Y.; Farhan, R.; Fuchs, G.; et al. Data and scripts from: Room temperature optically detected magnetic resonance of single spins in GaN. Cornell eCommons, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Santori, C.; Fattal, D.; Vučković, J.; Solomon, G.S.; Yamamoto, Y. Indistinguishable photons from a single-photon device. nature 2002, 419, 594–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sontheimer, B.; Braun, M.; Nikolay, N.; Sadzak, N.; Aharonovich, I.; Benson, O. Photodynamics of quantum emitters in hexagonal boron nitride revealed by low-temperature spectroscopy. Physical Review B 2017, 96, 121202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Luo, J.; van Deurzen, L.; Jena, D.; Fuchs, G.D.; Rana, F.; et al. Temperature Dependence of the Emission Spectrum of GaN Defect Single-Photon Emitters. arXiv e-prints 2022, arXiv–2206. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, Y.; Luo, J.; van Deurzen, L.H.; Jena, D.; Fuchs, G.D.; Rana, F. Temperature Dependence of Spectral Emission from GaN Defect Quantum Emitters. In Proceedings of the APS March Meeting 2022, APS, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, J.; Geng, Y.; Rana, F.; Fuchs, G.D. Room-Temperature Optically Detected Magnetic Resonance of GaN Defect Single-Photon Emitters. In Proceedings of the CLEO: Fundamental Science; Optica Publishing Group, 2023; pp. FM1E–5. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, Y.; Luo, J.; van Deurzen, L.; Xing, H.; Jena, D.; Fuchs, G.D.; Rana, F. Dephasing by optical phonons in GaN defect single-photon emitters. Scientific Reports 2023, 13, 8678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Geng, Y.; Rana, F.; Fuchs, G. Room temperature optically detected magnetic resonance in single spins hosted in GaN. Bulletin of the American Physical Society, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, Y. Temperature-Dependent Emission Polarization in GaN Defect-Based Quantum Emitters. arXiv arXiv:2504.18548.

- Fu, K.M.C.; Santori, C.; Barclay, P.E.; Rogers, L.J.; Manson, N.B.; Beausoleil, R.G. Observation of the Dynamic Jahn-Teller Effect in the Excited States of Nitrogen-Vacancy Centers in Diamond. Physical Review Letters 2009, 103, 256404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yi-Fei, G.; Zhu-Ning, W.; Yao-Guang, M.; Fei, G. Topological surface plasmon. polaritons. Acta Physica Sinica 2019, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y.; Nomoto, K. Ultrafast spectral diffusion of GaN defect single photon emitters. Applied Physics Letters 2023, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Hou, Y.; Yang, Z.; Chen, F.; Li, Q. GaN as a Material Platform for Single-Photon Emitters: Insights from Ab Initio Study. Advanced Optical Materials 2023, 11, 2202158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, Y. Acoustic Phonon-Induced Dephasing in Gallium Nitride Defect-Based Quantum Emitters. arXiv arXiv:2506.12984.

- Olivero, J.J.; Longbothum, R. Empirical fits to the Voigt line width: A brief review. Journal of Quantitative Spectroscopy and Radiative Transfer 1977, 17, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).