Submitted:

21 January 2026

Posted:

22 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Results

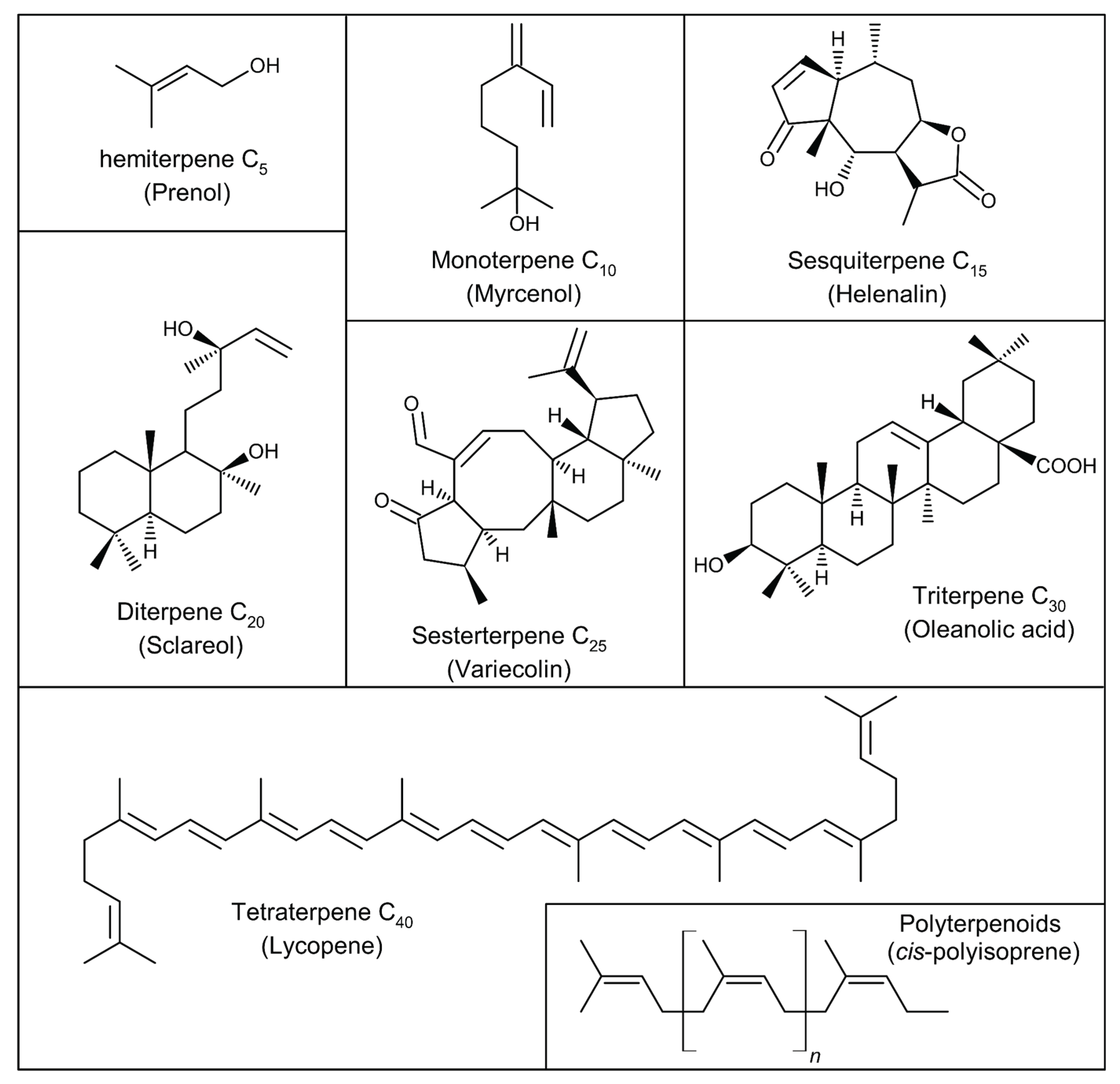

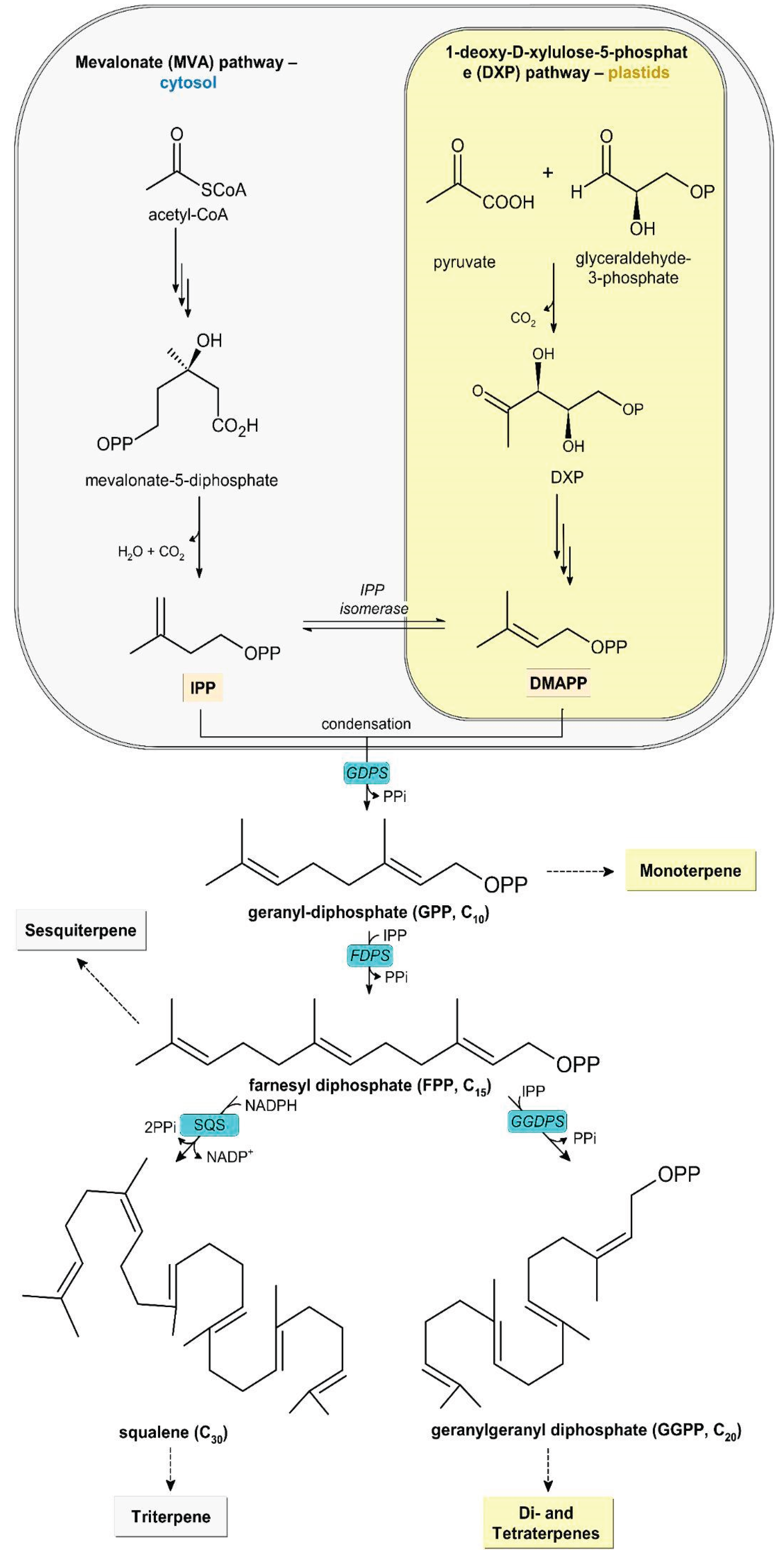

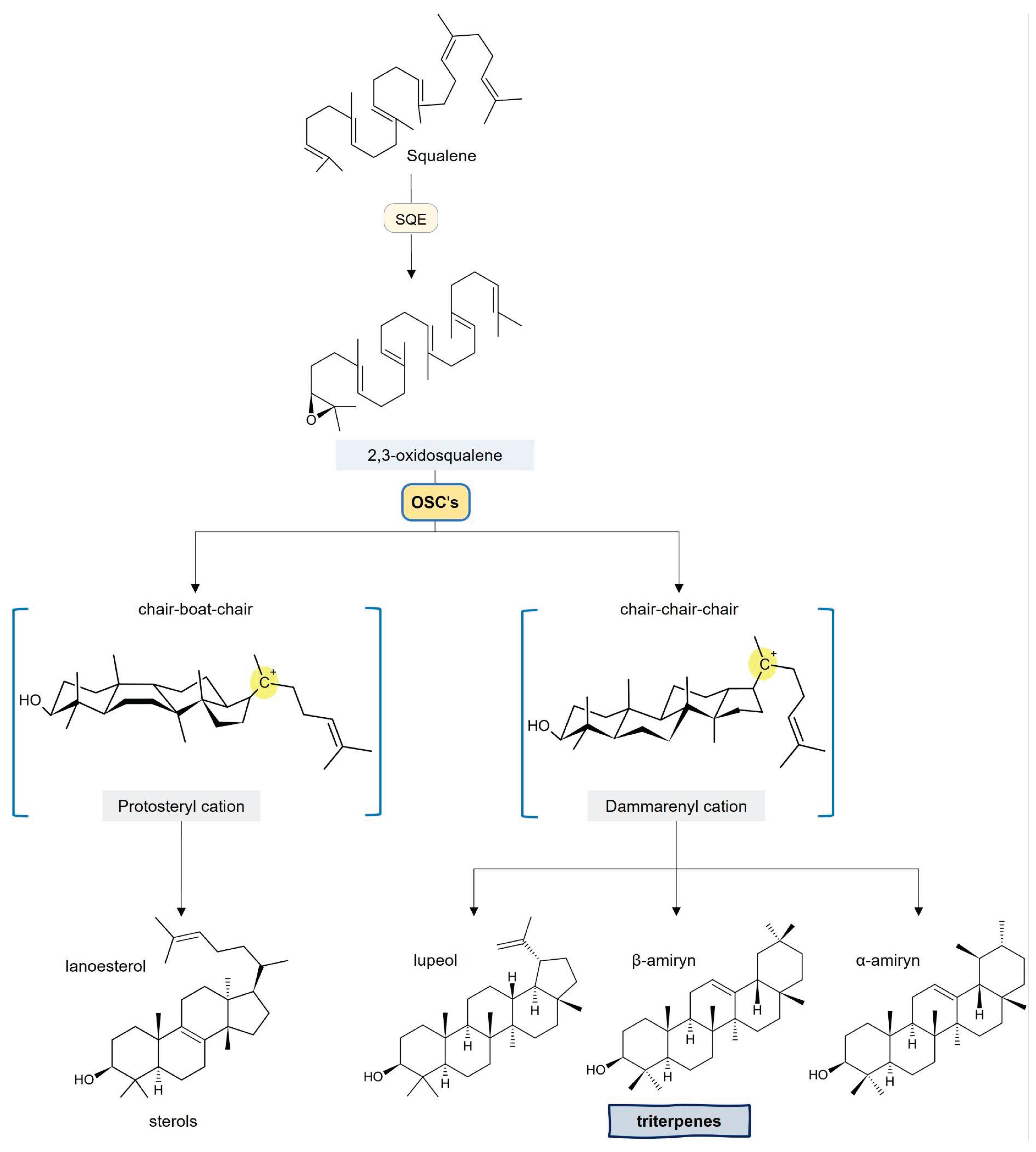

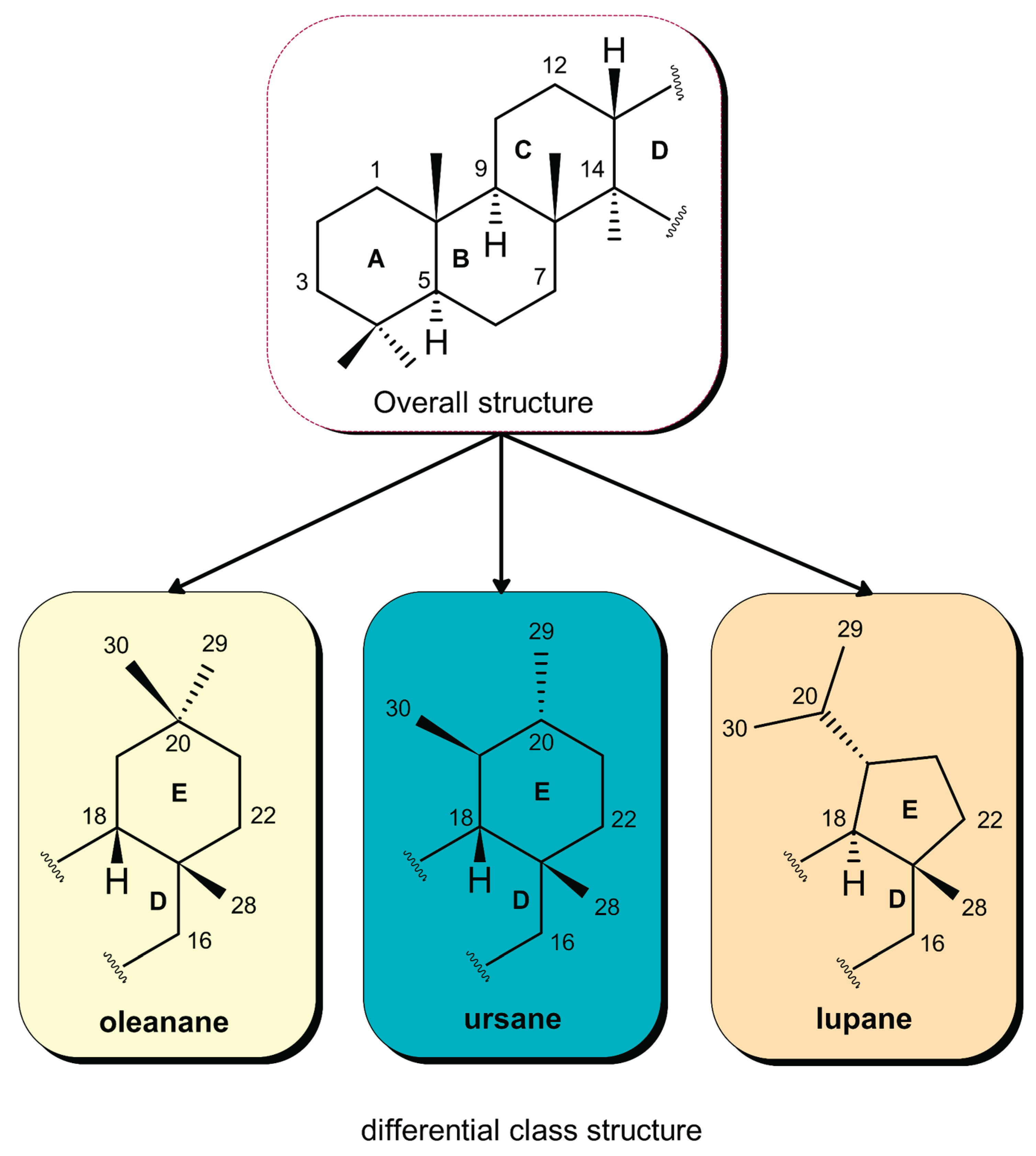

1. Classification and Structural Characteristics of Pentacyclic Triterpenes

2. Bioactivity of Triterpenes

2.1. Anti-Inflammatory Action

2.2. Antioxidant Activity

2.3. Antiadipogenic Activity and T2DM Control

2.4. Antifibrotic Activity

2.5. Antitumor Activity

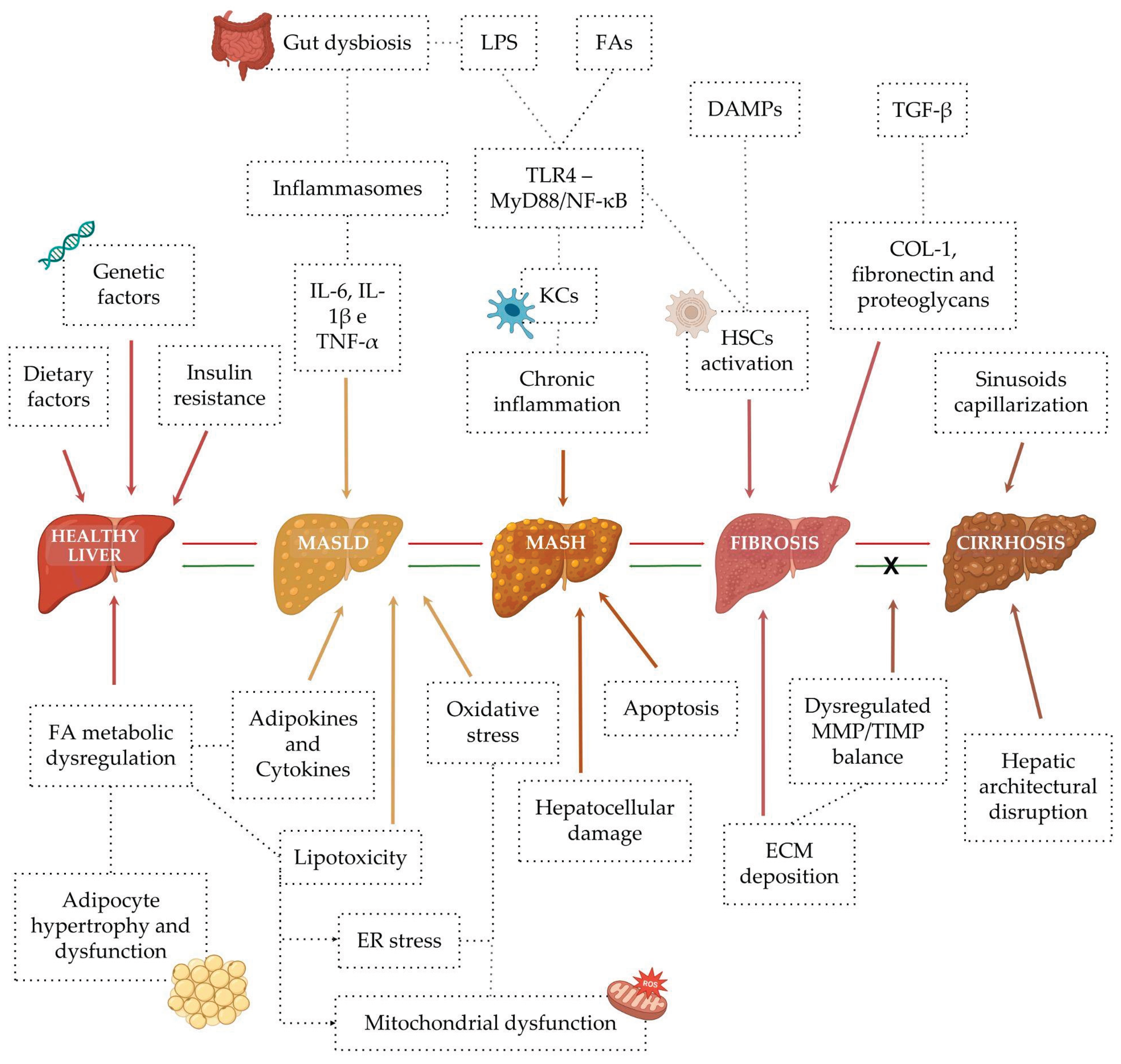

3. Mechanisms of Metabolic Dysfunction–Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD) and Metabolic Dysfunction–Associated Steatohepatitis (MASH)

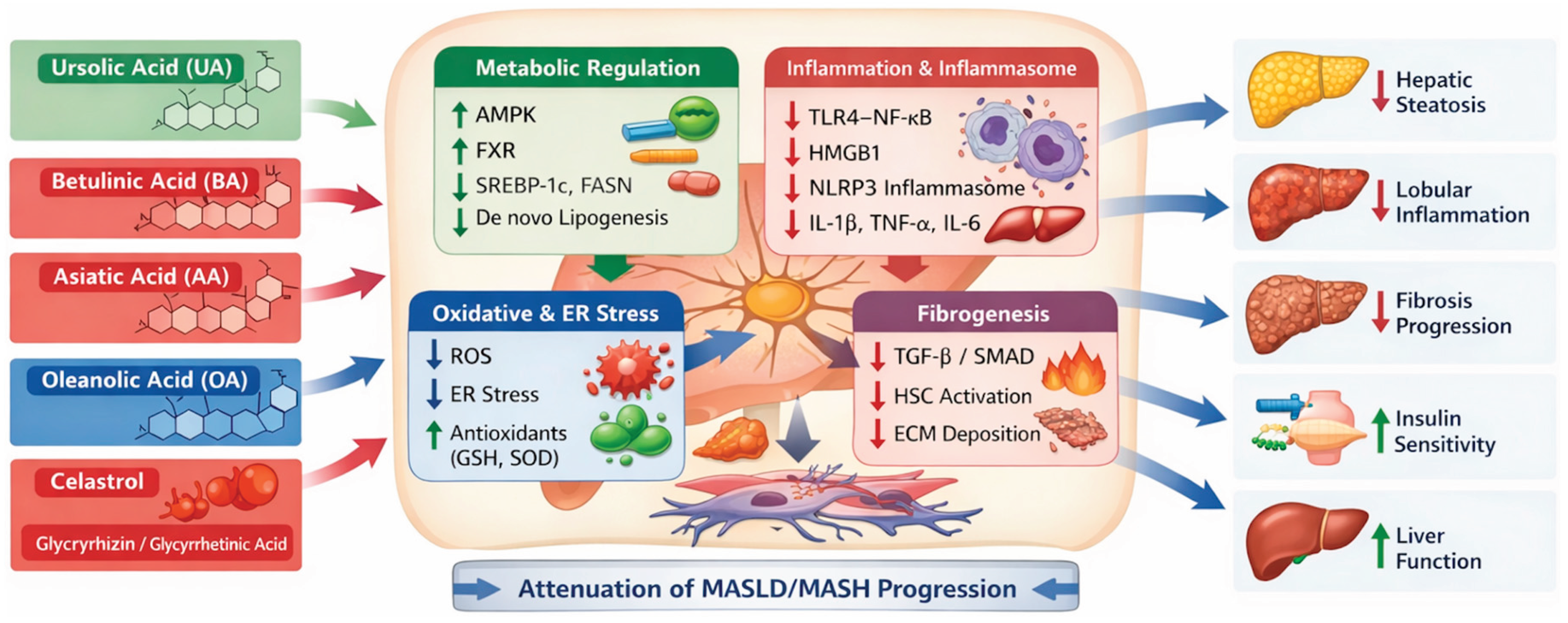

4. Current Applications of Triterpenes for MASLD and MASH

4.1. Ursolic Acid (UA)

4.2. Betulinic Acid (BA)

4.3. Asiatic Acid (AA)

4.4. Oleanolic Acid (OA)

4.5. Celastrol

4.6. Glycyrrhizin and Glycyrrhetinic Acid

5. Strategies for Enhancing Triterpenes Bioavailability and Efficacy

Conclusions

Funding Information

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thimmappa, R.; Geisler, K.; Louveau, T.; O’Maille, P.; Osbourn, A. Triterpene Biosynthesis in Plants. Annual Review of Plant Biology 2014, 65, 225–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goddard, Z.R.; Searcey, M.; Osbourn, A. Advances in Triterpene Drug Discovery. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 2024, 45, 964–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, G.J.; Koncz, C. Brassinosteroids and Plant Steroid Hormone Signaling. The Plant Cell 2002, 14 (Suppl), S97–S110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarasova, E. V.; Luchnikova, N. A.; Grishko, V. V.; Ivshina, I. B. Actinomycetes as Producers of Biologically Active Terpenoids: Current Trends and Patents. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2023, 16(6), 872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krivoruchko, A.; Nielsen, J. Production of Natural Products through Metabolic Engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2015, 35, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.C.; Duarte, L.P.; Vieira Filho, S.A. Celastraceae Family: Source of Pentacyclic Triterpenes with Potential Biological Activity. Revista Virtual de Química 2014, 6(5), 1205–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T. Unique Biosynthesis of Sesquarterpenes (C35 Terpenes). Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry 2013, 77(6), 1155–1159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ninkuu, V.; Zhang, L.; Yan, J.; Fu, Z.; Yang, T.; Zeng, H. Biochemistry of Terpenes and Recent Advances in Plant Protection. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2021, 22(11), 5710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, F.C.O.; Ferreira, M.K.A.; Silva, A.W.d.; Matos, M.G.C.; Magalhães, F.E.A.; Silva, P.T.d.; Bandeira, P.N.; Menezes, J.E.S.A.d.; Santos, H.S. Bioactivities of Plant-Isolated Triterpenes: A Brief Review. Revista Virtual de Química 2020, 12(1), 234–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, J.; Keasling, J.D. Biosynthesis of Plant Isoprenoids: Perspectives for Microbial Engineering. Annual Review of Plant Biology 2009, 60, 335–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibodeaux, C.J.; Liu, H.-W. The Type II Isopentenyl Diphosphate:Dimethylallyl Diphosphate Isomerase (IDI-2): A Model for Acid/Base Chemistry in Flavoenzyme Catalysis. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 2017, 632, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, D.R.; Rasbery, J.M.; Bartel, B.; Matsuda, S.P.T. Biosynthetic Diversity in Plant Triterpene Cyclization. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 2006, 9(3), 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parveen, I.; Wang, M.; Lee, J.; Zhao, J.; Zhu, Y.; Chittiboyina, A.G.; Khan, I.A.; Pan, Z. Identification and Functional Characterization of Oxidosqualene Cyclases from Medicinal Plant Hoodia gordonii. Plants (Basel) 2024, 13(2), 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhemileva, L.U.; Tuktarova, R.A.; Dzhemilev, U.M.; D’yakonov, V.A. Pentacyclic Triterpenoids-Based Ionic Compounds: Synthesis, Study of Structure–Antitumor Activity Relationship, Effects on Mitochondria and Activation of Signaling Pathways of Proliferation, Genome Reparation and Early Apoptosis. Cancers 2023, 15(3), 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ames, T.R.; Halsall, T.G.; Jones, E.R.H. The Chemistry of the Triterpenes. Part VII. An Interrelationship between the Lupeol and the β-Amyrin Series. Elucidation of the Structure of Lupeol. Journal of the Chemical Society 1951, 450–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halsall, T.G.; Aplin, R.T. A Pattern of Development in the Chemistry of Pentacyclic Triterpenes. Fortschritte der Chemie Organischer Naturstoffe / Progress in the Chemistry of Organic Natural Products 1964, 22, 153–202. [Google Scholar]

- Arpino, P.; Albrecht, P.; Ourisson, G. Studies on the Organic Constituents of Lacustrine Eocene Sediments. Possible Mechanisms for the Formation of Some Geolipids Related to Biologically Occurring Terpenoids. In Advances in Organic Geochemistry; von Gaertner, H.R., Wehner, H. (Eds.); Pergamon Press: Oxford, 1972; pp. 173–187.

- Kimble, B.J.; Maxwell, J.R.; Philp, R.F.; Eglinton, G.; Albrecht, P.; Ensminger, A.; Arpino, A.; Ourisson, G. Tri- and Tetra-Terpenoid Hydrocarbons in the Messes Oil Shale. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 1974, 38, 1165–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodon, J.; Borkova, L.; Pokorny, J.; Kazakova, A.; Urban, M. Design and Synthesis of Pentacyclic Triterpene Conjugates and Their Use in Medicinal Research. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2019, 182, 111653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wu, X.; Ma, Y.; Zou, Y.; Cai, Y.; Gao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, Y.-J. Natural Products of Pentacyclic Triterpenoids: From Discovery to Heterologous Biosynthesis. Natural Product Reports 2023, 40(8), 1303–1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Safayhi, H.; Sailer, E.-R. Anti-Inflammatory Actions of Pentacyclic Triterpenes. Planta Medica 1997, 63(6), 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, H.; Hu, K.; Xu, Q.; Wen, X.; Cheng, K.; Chen, C.; Yuan, H.; Dai, L.; Sun, H. Synthesis and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Saponin Derivatives of δ-Oleanolic Acid. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2021, 209, 112932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.-Y.; Ha, J.Y.; Kim, K.-M.; Jung, Y.-S.; Jung, J.-C.; Oh, S. Anti-Inflammatory Activities of Licorice Extract and Its Active Compounds, Glycyrrhizic Acid, Liquiritin and Liquiritigenin, in BV2 Cells and Mice Liver. Molecules 2015, 20, 13041–13054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pastorino, G.; Cornara, L.; Soares, S.; Rodrigues, F.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P. Liquorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra): A Phytochemical and Pharmacological Review. Phytotherapy Research 2018, 32(12), 2323–2339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisht, D.; Rashid, M.; Arya, R.K.K.; Kumar, D.; Chaudhary, S.K.; Rana, V.S.; Sethiya, N.K. Revisiting Liquorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra L.) as Anti-Inflammatory, Antivirals and Immunomodulators: Potential Pharmacological Applications with Mechanistic Insight. Phytomedicine Plus 2022, 2(1), 100206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Bhattacharjee, A.; Majumder, S.; Bhattacharya Majumdar, S.; Majumdar, S. Glycyrrhizic Acid Suppresses Cox-2-Mediated Anti-Inflammatory Responses during Leishmania donovani Infection. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2012, 67(8), 1905–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houssen, M.E.; Ragab, A.; Mesbah, A.; El-Samanoudy, A.Z.; Othman, G.; Moustafa, A.F.; Badria, F.A. Natural Anti-Inflammatory Products and Leukotriene Inhibitors as Complementary Therapy for Bronchial Asthma. Clinical Biochemistry 2010, 43(10–11), 887–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Račková, L.; Jančinová, V.; Petríková, M.; Drábiková, K.; Nosáľ, R.; Štefek, M.; Kováčová, M. Mechanism of anti-inflammatory action of liquorice extract and glycyrrhizin. Natural Product Research 2007, 21(14), 1234–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, I.; Sahar, A.; Tariq, A.; Naz, T.; Usman, M. Exploring the Role of Licorice and Its Derivatives in Cell Signaling Pathway NF-κB and MAPK. Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism 2024, 2024, 9988167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, H.; Choi, A.; Seo, N.; et al. Protective effect of glycyrrhizin, a direct HMGB1 inhibitor, on post-contrast acute kidney injury. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 15625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C. Y.; Ouyang, S. H.; Wang, X.; et al. Celastrol ameliorates Propionibacterium acnes/LPS-induced liver damage and MSU-induced gouty arthritis via inhibiting K63 deubiquitination of NLRP3. Phytomedicine 2021, 80, 153398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Zhao, W.; Liu, X.; Huang, Z.; Shan, R.; Huang, C. Celastrol ameliorates inflammatory pain and modulates HMGB1/NF-κB signaling pathway in dorsal root ganglion. Neuroscience Letters 2019, 692, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, L.; Yu, G.; Yang, K.; et al. Exploring the mechanism of celastrol in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis based on systems pharmacology and multi-omics. Scientific Reports 2024, 14, 1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sethi, G.; Ahn, K.S.; Pandey, M.K.; Aggarwal, B.B. Celastrol, a Novel Triterpene, Potentiates TNF-Induced Apoptosis and Suppresses Invasion of Tumor Cells by Inhibiting NF-κB-Regulated Gene Products and TAK1-Mediated NF-κB Activation. [published correction appears in Blood. 2013 Aug 15;122(7):1327]. Blood 2007, 109(7), 2727–2735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Li, H.; Hu, K.; Xu, Q.; Wen, X.; Cheng, K.; Chen, C.; Yuan, H.; Dai, L.; Sun, H. Synthesis and anti-inflammatory activity of saponin derivatives of δ-oleanolic acid. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2021, 209, 112932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Ciric, B.; Curtis, M.T.; Chen, W.J.; Rostami, A.; Zhang, G.X. A Dual Effect of Ursolic Acid in the Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis through Both Immunomodulation and Direct Remyelination. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2020, 117(16), 9082–9093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortiboys, H.; Aasly, J.; Bandmann, O. Ursocholanic Acid Rescues Mitochondrial Function in Common Forms of Familial Parkinson’s Disease. Brain 2013, 136(10), 3038–3050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.Y.; Sudini, K.; Singh, A.K.; Haque, M.; Leaman, D.; Khuder, S.; Ahmed, S. Ursolic Acid Facilitates Apoptosis in Rheumatoid Arthritis Synovial Fibroblasts by Inducing SP1-Mediated Noxa Expression and Proteasomal Degradation of Mcl-1. FASEB Journal 2018, 32(11), fj201800425R. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, A; Hamid, K.; Kam, A.; Wong, K.H.; Abdelhak, Z.; Razmovski-Naumovski, V.; Chan, K.; Li, K.M.; Groundwater, P.W.; Li, G.Q. The Pentacyclic Triterpenoids in Herbal Medicines and Their Pharmacological Activities in Diabetes and Diabetic Complications. Current Medicinal Chemistry 2013, 20(7), 908–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Zhang, M.; Li, X.-L.; Li, H.; Yue, L.-T.; Zhang, X.-X.; Wang, C.-C.; Wang, S.; Duan, R.-S. Low and High Doses of Ursolic Acid Ameliorate Experimental Autoimmune Myasthenia Gravis through Different Pathways. Journal of Neuroimmunology 2015, 281, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Wang, X.; Zhong, B.; Nurieva, R.I.; Ding, S.; Dong, C. Ursolic Acid Suppresses Interleukin-17 (IL-17) Production by Selectively Antagonizing the Function of RORγt Protein. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2011, 286(26), 22707–22710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Wu, F.; Tang, Z.; Yang, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, F.; Chen, B. Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Activity of Ursolic Acid: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2023, 14, 1256946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ammon, H.P.T. Boswellic acids in chronic inflammatory diseases. Planta Medica 2006, 72(12), 1100–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, J.-Q.; Zhang, Y.-J.; Tian, Z.-K. Anti-oxidant, Anti-inflammatory and Anti-fibrosis Effects of Ganoderic Acid A on Carbon Tetrachloride Induced Nephrotoxicity by Regulating the Trx/TrxR and JAK/ROCK Pathway. Chemico-Biological Interactions 2021, 344, 109529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-Suárez, M.Z.; Christen, J.G.; Cardoso-Taketa, A.T.; Villafuerte, M.d.C.G..; Rodríguez-López, V. Anti-Inflammatory and Antihistaminic Activity of Triterpenoids Isolated from Bursera cuneata (Schldl.) Engl. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2019, 238, 111786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.-M.; Su, X.-Q.; Sun, J.; Gu, Y.-F.; Huang, Z.; Zeng, K.-W.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, Y.-F.; Ferreira, D.; Zjawiony, J.K.; Li, J.; Tu, P.-F. Anti-Inflammatory Ursane- and Oleanane-Type Triterpenoids from Vitex negundo var. cannabifolia. Journal of Natural Products 2014, 77(10), 2248–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recio, M.C.; Giner, R.M.; Máñez, S.; Ríos, J.L. Structural Requirements for the Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Natural Triterpenoids. Planta Medica 1995, 61(2), 182–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allouche, Y.; Beltrán, G.; Gaforio, J.J.; Uceda, M.; Mesa, M.D. Antioxidant and Antiatherogenic Activities of Pentacyclic Triterpenic Diols and Acids. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2010, 48(10), 2885–2890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Wang, W.; Wang, L.; Liu, R.; Ding, Y.; Du, L. Constituents of the Flowers of Punica granatum. Fitoterapia 2006, 77(7–8), 534–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, J.; Lee, H.; Hong, S.; Lee, J.; Kim, Y. Comparison of the Antioxidant Potency of Four Triterpenes of Centella asiatica against Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamadalieva, N.Z.; Youssef, F.S.; Hussain, H.; Zengin, G.; Mollica, A.; Al Musayeib, N.M.; Ashour, M.L.; Westermann, B.; Wessjohann, L.A. Validation of the Antioxidant and Enzyme Inhibitory Potential of Selected Triterpenes Using In Vitro and In Silico Studies, and the Evaluation of Their ADMET Properties. Molecules 2021, 26, 6331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostapiuk, A.; Kurach, Ł.; Strzemski, M.; Kurzepa, J.; Hordyjewska, A. Evaluation of Antioxidative Mechanisms In Vitro and Triterpenes Composition of Extracts from Silver Birch (Betula pendula Roth) and Black Birch (Betula obscura Kotula) Barks by FT-IR and HPLC-PDA. Molecules 2021, 26, 4633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarjeant, K.; Stephens, J.M. Adipogenesis. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2012, 4(9), a008417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Wang, Q.; Su, H.-G.; Zhou, L.; Xiong, W.-Y.; Qiu, M.-H. Anti-Adipogenic Lanostane-Type Triterpenoids from the Edible and Medicinal Mushroom Ganoderma applanatum. Journal of Fungi 2022, 8(4), 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohsen, A.-M; Abu-Taweel, G.M.; Rajagopal, R.; Sun-Ju, K.; Kim, H.-J.; Kim, Y.O.; Mothana, R.A.; Kadaikunnan, S.; Khaled, J.M.; Siddiqui, N.A.; Al-Rehaily, A.J. Betulinic acid lowers lipid accumulation in adipocytes through enhanced NCoA1-PPARγ interaction. Journal of Infection and Public Health 2019, 12(5), 726–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, C.L.D.; Queiroz, M.G.R.; Arruda Filho, A.C.V.; Rodrigues, A.M.; Sousa, D.F.D.; Almeida, J.G.L.; Pessoa, O.D.L.; Silveira, E.R.; Menezes, D.B.; Melo, T.S.; Santos, F.A.; Rao, V.S. Betulinic acid, a natural pentacyclic triterpenoid, prevents abdominal fat accumulation in mice fed a high-fat diet. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2009, 57(19), 8776–8781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betancur, L.I.; Muñoz, D.L.; Guillen, A.; Echeverri, L.F.; Balcazar, N.; Acín, S. Major Triterpenoids from Eucalyptus tereticornis Have Enhanced Beneficial Effects in Cellular Models When Mixed with Minor Compounds Present in Raw Extract. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências 2021, 93 (Suppl. 3), e20201351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acín, S.; Balcázar, N.; Guillen, A.; Echeverri, L.F.; Betancur, L.I.; Muñoz, D.L. Triterpene-Enriched Fractions from Eucalyptus tereticornis Leaves with Different Triterpene Composition Improve Insulin Sensitivity and Reduce Hepatic Lipid Accumulation in a Nutritional Animal Model of Prediabetes. Chemico-Biological Interactions 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, D.; Liu, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wu, Z.; Li, H.; Wang, H. Ursolic acid alleviates lipid accumulation by activating the AMPK signaling pathway in vivo and in vitro. Journal of Food Science 2020, 85(11), 3998–4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bermudes-Contreras, J.D.; Gutiérrez-Velázquez, M.V.; Delgado-Alvarado, E.A.; Torres-Ricario, R.; Cornejo-Garrido, J. Hypoglycemic and Hypolipidemic Effects of Triterpenoid Standardized Extract of Agave durangensis Gentry. Plants 2025, 14(6), 894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liou, C.-J.; Dai, Y.-W.; Wang, C.-L.; Fang, L.-W.; Huang, W.-C. Maslinic acid protects against obesity-induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in mice through regulation of the Sirt1/AMPK signaling pathway. FASEB Journal 2019, 33(11), 11791–11803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaitone, S.A.; Barakat, B.M.; Bilasy, S.E.; Fawzy, M.S.; Abdelaziz, E.Z.; Farag, N.E. Protective Effect of Boswellic Acids versus Pioglitazone in a Rat Model of Diet-Induced Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Influence on Insulin Resistance and Energy Expenditure. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology 2015, 388(6), 587–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Z.; Wu, W.; Bai, Z.; Xiu, Y.; Zhou, D. Beta-boswellic Acid Facilitates Diabetic Wound Healing by Targeting STAT3 and Inhibiting Ferroptosis in Fibroblasts. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2025, 16, 1578625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reish, R.G.; Eriksson, E.; Galiano, R.D.; Dobryansky, M.; Levine, J.P.; Gurtner, G.C. Scars: A Review of Emerging and Currently Available Therapies. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery 2008, 122(4), 1068–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, N.A.; Maderal, A.D.; Vivas, A.C. US-National Institutes of Health-Funded Research for Cutaneous Wounds in 2012. Wound Repair and Regeneration 2013, 21(6), 789–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, R.J.; Porte, J.; Braybrooke, R.; Flores, C.; Fingerlin, T.E.; Oldham, J.M.; Guillen-Guio, B.; Ma, S.-F.; Okamoto, T.; John, A.E.; et al. Genetic Variants Associated with Susceptibility to Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis in People of European Ancestry: A Genome-Wide Association Study. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine 2017, 5(11), 869–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, S.L.; Bansal, M.B. Mechanisms of Hepatic Fibrogenesis. Gastroenterology 2008, 134(6), 1655–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inagaki, Y.; Okazaki, I.; Sanjo, A.; Aoyama, T.; Kato, H.; Fujii, H.; Sata, M.; Tsuneyama, K.; Nishimura, T. Emerging Insights into Transforming Growth Factor β/Smad Signal in Hepatic Fibrogenesis. Gut 2007, 56(2), 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.-X.; Wu, W.-J.; Chen, X.-H.; Li, Q.; Chen, Y.; Lin, L.; Yang, F.; Fang, M.; Gao, J.; Zhang, D.-M. Asiatic Acid Inhibits Liver Fibrosis by Blocking TGF-β/Smad Signaling In Vivo and In Vitro. PLoS One 2012, 7(2), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, M.-S.; Lee, H.-S.; Park, J.-H.; Lee, S.-J.; Kim, H.-J.; Kim, D.-H. Structure-Related Cytotoxicity and Anti-Hepatofibric Effect of Asiatic Acid Derivatives in Rat Hepatic Stellate Cell-Line, HSC-T6. Archives of Pharmacal Research 2004, 27(5), 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueberham, E.; Löser, E.; Klotz, L.-O.; Weise, C.; Gebhardt, R. Conditional Tetracycline-Regulated Expression of TGF-β1 in Liver of Transgenic Mice Leads to Reversible Intermediary Fibrosis. Hepatology 2003, 37(5), 1067–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Ikejima, K.; Kon, K.; Arai, K.; Aoyama, T.; Okumura, K.; Abe, W.; Sato, N.; Watanabe, S. Ursolic Acid Ameliorates Hepatic Fibrosis in the Rat by Specific Induction of Apoptosis in Hepatic Stellate Cells. Journal of Hepatology 2011, 55(2), 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.-Y.; Zhang, M.; Fang, G.; Cheng, C.-J.; Wang, M.-K.; Han, Y.-M.; Hou, X.-T.; Hao, E.-W.; Hou, Y.-Y.; Bai, G. Ursolic Acid Reduces Hepatocellular Apoptosis and Alleviates Alcohol-Induced Liver Injury via Irreversible Inhibition of CASP3 in Vivo. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica 2021, 42, 1101–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Fang, F.; Ma, J.; Li, C.; Zhang, J.; Sun, L.; Lu, C.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Xu, Q. A Synthetic PPAR-γ Agonist Triterpenoid Ameliorates Experimental Fibrosis: PPAR-γ-Independent Suppression of Fibrotic Responses. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2013, 73(2), 446–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batteux, F.; LeRoy, E.C.; Assassi, S.; Denton, C.P.; Distler, O.; Varga, J. New Insights on Chemically Induced Animal Models of Systemic Sclerosis. Current Opinion in Rheumatology 2011, 23(6), 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, D.; Yu, X.; Chen, M.; Sun, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, L.; Xu, J.; Li, Q.; et al. Targeted Therapeutic Remodeling of the Tumor Microenvironment Improves an HER-2 DNA Vaccine and Prevents Recurrence in a Murine Breast Cancer Model. Cancer Research 2011, 71(17), 5688–5696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhmetshina, A.; Palumbo, K.; Dees, C.; Bergmann, C.; Venalis, P.; Zerr, P.; Horn, A.; Kireva, T.; Beyer, C.; Zwerina, J.; et al. Activation of Canonical Wnt Signalling Is Required for TGF-β-Mediated Fibrosis. Nature Communications 2012, 3(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, M.-L.; Lin, Y.-T.; Kung, H.-N.; Hou, Y.-C.; Liu, J.-J.; Pan, M.-H.; Chen, H.-L.; Yu, C.-H.; Tsai, P.-J. A Triterpenoid-Enriched Extract of Bitter Melon Leaves Alleviates Hepatic Fibrosis by Inhibiting Inflammatory Responses in Carbon Tetrachloride-Treated Mice. Food and Function 2021, 12(17), 7805–7815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thannickal, V.J.; Zhou, Y.; Gaggar, A.; Duncan, S.R.; Osei, E.T.; Jenkins, R.G. Fibrosis: Ultimate and Proximate Causes. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2014, 124(11), 4673–4677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, H.; Sun, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L. Betulinic Acid Attenuated Bleomycin-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis by Effectively Intervening Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling. Phytomedicine 2021, 81, 153428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanahan, D.; Weinberg, R.A. Hallmarks of Cancer: The Next Generation. Cell 2011, 144, 646–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razboršek, M.; Voncina, D.; Doleček, V.; Voncina, E. Determination of Oleanolic, Betulinic and Ursolic Acid in Lamiaceae and Mass Spectral Fragmentation of Their Trimethylsilylated Derivatives. Chromatographia 2008, 67, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantley, L.C.; Baselga, J. The Era of Cancer Discovery. Cancer Discovery 2011, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasui, W. Future Perspectives of Gastric Cancer Treatment – From Bench to Bedside. Pathobiology 2011, 78, 293–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muffler, K.; Leipold, D.; Scheller, M.C.; Haans, C.; Steingroewer, J.; Bley, T.; Neuhaus, H.E.; Mirata, M.A.; Schrader, J.; Ulber, R. Biotransformation of Triterpenes. Process Biochemistry 2011, 46, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Chen, T.; Ye, Z.; Chen, G. Use of Liquid Chromatography–Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization–Ion Trap Mass Spectrometry for Identification of Oleanolic Acid and Ursolic Acid in Anoectochilus roxburghii (Wall.) Lindl. Journal of Mass Spectrometry 2007, 42, 910–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.-H.; Sun, W.-J.; Zhu, H.-T.; Wang, D.; Yang, C.-R.; Zhang, Y.-J. New Hydroperoxylated and 20,24-Epoxylated Dammarane Triterpenes from the Rot Roots of Panax notoginseng. Journal of Ginseng Research 2020, 44(3), 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J. Anti-inflammatory and Analgesic Effects and the Mechanism of Actions of Ginsenoside Rg1. Chinese Journal of Hospital Pharmacy 2013, 33, 1592. [Google Scholar]

- Ahn, S.; Siddiqi, M. H.; Noh, H. Y.; Kim, Y. J.; Jin, C. G.; Yang, D. C. Anti-inflammatory Activity of Ginsenosides in LPS-Stimulated RAW264.7 Cells. Science Bulletin 2015, 60(8), 773–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Li, X.; Xia, S. Lupeol triterpene exhibits potent antitumor effects in A427 human lung carcinoma cells via mitochondrial mediated apoptosis, ROS generation, loss of mitochondrial membrane potential and downregulation of m-TOR/PI3K/AKT signalling pathway. Journal of BUON 2018, 23(3), 635–640. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, S.; Khan, M. A.; Khan, M. R.; Anwar, F.; Khan, A.; Shah, N.; Ullah, R.; Rahman, A. Evaluation of the Cytotoxic Potential of a New Pentacyclic Triterpene from Rhododendron arboreum Stem Bark. Pharmaceutical Biology 2017, 55(1), 1927–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, Y.-L.; Kuo, P.-L.; Lin, L.-T.; Lin, C.-C. Proliferative Inhibition, Cell-Cycle Dysregulation, and Induction of Apoptosis by Ursolic Acid in Human Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer A549 Cells. Life Sciences 2004, 75(19), 2303–2316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.-H.; Yu, Y.-Y.; Xu, X.-Y. Management of chronic liver diseases and cirrhosis: current status and future directions. Chinese Medical Journal (Engl.) 2020, 133(22), 2647–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roehlen, N.; Crouchet, E.; Baumert, T. F. Liver Fibrosis: Mechanistic Concepts and Therapeutic Perspectives. Cells 2020, 9(4), 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Targher, G.; Byrne, C. D.; Tilg, H. MASLD: a systemic metabolic disorder with cardiovascular and malignant complications. Gut 2024, 73, 691–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mladenić, K.; Lenartić, M.; Marinović, S.; Polić, B.; Wensveen, F. M. The “Domino effect” in MASLD: The inflammatory cascade of steatohepatitis. European Journal of Immunology 2024, 54, e2149641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lekakis, V.; Papatheodoridis, G. V. Natural history of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. European Journal of Internal Medicine 2024, 122, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Israelsen, M.; Johansen, S.; Torp, N.; et al. Steatotic liver disease. Lancet 2024, 404, 1761–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caligiuri, A.; Gentilini, A.; Marra, F. Molecular Pathogenesis of NASH. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2016, 17, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessone, F.; Razori, M. V.; Roma, M. G. Molecular pathways of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease development and progression. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2019, 76, 99–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tourkochristou, E.; Assimakopoulos, S. F.; Thomopoulos, K.; Marangos, M.; Triantos, C. NAFLD and HBV interplay—related mechanisms underlying liver disease progression. Frontiers in Immunology 2022, 13, 965548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzzetti, E.; Pinzani, M.; Tsochatzis, E. A. The multiple-hit pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Metabolism 2016, 65(8), 1038–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S. K.; Bansal, M. B. Pathogenesis of MASLD and MASH—role of insulin resistance and lipotoxicity. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2024, 59(1), S10–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Zhang, W.; Huang, C.; Jian, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Chen, P.; Zhu, X. Ursolic acid alleviates Kupffer cells pyroptosis in liver fibrosis by the NOX2/NLRP3 inflammasome signaling pathway. International Immunopharmacology 2022, 113, 109321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, B.; Zhou, Y.-X.; Li, H.; Zhang, R.-Z.; He, C.; Yang, X. The METTL3/MALAT1/PTBP1/USP8/TAK1 axis promotes pyroptosis and M1 polarization of macrophages and contributes to liver fibrosis. Cell Death Discovery 2021, 7(1), 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, K.; Shi, Z.; Zhang, M.; Dong, X.; Zheng, L.; Li, G.; Han, X.; Yao, Z.; Han, T.; Hong, W. Silencing lncRNA Lfar1 alleviates the classical activation and pyroptosis of macrophage in hepatic fibrosis. Cell Death & Disease 2020, 11(2), 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berumen, J.; Baglieri, J.; Kisseleva, T.; Mekeel, K. Liver fibrosis: Pathophysiology and clinical implications. WIREs Mechanisms of Disease 2021, 13, e1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammerich, L.; Tacke, F. Hepatic inflammatory responses in liver fibrosis. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2023, 20, 633–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurzepa, J.; Mądro, A.; Czechowska, G.; Kurzepa, J.; Celiński, K.; Kazmierak, W.; Słomka, M. Role of MMP-2 and MMP-9 and their natural inhibitors in liver fibrosis, chronic pancreatitis and non-specific inflammatory bowel diseases. Hepatobiliary & Pancreatic Diseases International 2014, 13(6), 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabir, U.; Gu, H.-M.; Zhang, D.-W. Extracellular matrix turnover: phytochemicals target and modulate the dual role of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in liver fibrosis. Phytotherapy Research 2023, 37, 4932–4962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalan, R.; D'Amico, G.; Trebicka, J.; Moreau, R.; Angeli, P.; Arroyo, V. New clinical and pathophysiological perspectives defining the trajectory of cirrhosis. Journal of Hepatology 2021, 75(1), S14–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.; John, S. Hepatic Cirrhosis. StatPearls Publishing 2022. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482419/.

- Yoshiji, H.; Nagoshi, S.; Akahane, T.; Asaoka, Y.; Ueno, Y.; Ogawa, K.; Kawaguchi, T.; Kurosaki, M.; Sakaida, I.; Shimizu, M.; Taniai, M.; Terai, S.; Nishikawa, H.; Hiasa, Y.; Hidaka, H.; Miwa, H.; Chayama, K.; Enomoto, N.; Shimosegawa, T.; Takehara, T.; Koike, K. Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines for Liver Cirrhosis 2020. Journal of Gastroenterology 2021, 56, 593–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedé-Ubieto, R.; Cubero, F. J.; Nevzorova, Y. A. Breaking the barriers: the role of gut homeostasis in Metabolic-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD). Gut Microbes 2024, 16(1), 2331460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Liu, L.-X.; Li, B.-M.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, P.; Huang, C.-K.; Nie, Y.; Zhu, X. Exploring the mechanism of ursolic acid in preventing liver fibrosis and improving intestinal microbiota based on NOX2/NLRP3 inflammasome signaling pathway. Chemico-Biological Interactions 2025, 405, 111305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortea, J. I.; Crespo, J.; Puente, Á. Cirrhosis, a Global and Challenging Disease. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2022, 11(21), 6512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelmann, C.; Clària, J.; Szabo, G.; Bosch, J.; Bernardi, M. Pathophysiology of Decompensated Cirrhosis: Portal Hypertension, Circulatory Dysfunction, Inflammation, Metabolism and Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Journal of Hepatology 2021, 75(1), S49–S66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X. H.; Zhao, Y. C.; Yin, L.; Xu, R. L.; Han, D. W.; Wang, M. S. Studies on the preventive and therapeutic effects of ursolic acid (UA) on acute hepatic injury in rats. Yao Xue Xue Bao 1986, 21(5), 332-335. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3776541/. [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Aragón, S.; de las Heras, B.; Sanchez-Reus, M. I.; Benedi, J. Pharmacological Modification of Endogenous Antioxidant Enzymes by Ursolic Acid on Tetrachloride-Induced Liver Damage in Rats and Primary Cultures of Rat Hepatocytes. Experimental and Toxicologic Pathology 2001, 53(2–3), 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, R.; Viswanathan, P.; Pugalendi, K. V. Protective Effect of Ursolic Acid on Ethanol-Mediated Experimental Liver Damage in Rats. Life Sciences 2006, 78(7), 713–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.; Huang, C.; Zhao, L.; Chen, Y.; Liu, F. Regulation of Decorin by Ursolic Acid Protects against Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2021, 143, 112166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukonowenzou, N. C.; Dangarembizi, R.; Chivandi, E.; Nkomozepi, P.; Erlwanger, K. H. Administration of ursolic acid to new-born pups prevents dietary fructose-induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Sprague Dawley rats. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease 2021, 12(1), 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Ikejima, K.; Kon, K.; Arai, K.; Aoyama, T.; Okumura, K.; Abe, W.; Sato, N.; Watanabe, S. Ursolic Acid Ameliorates Hepatic Fibrosis in the Rat by Specific Induction of Apoptosis in Hepatic Stellate Cells. Journal of Hepatology 2011, 55(2), 379–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, S.; Huang, C.; Wang, A.; Zhu, X. Ursolic Acid Improves the Bacterial Community Mapping of the Intestinal Tract in Liver Fibrosis Mice. PeerJ 2020, 8, e9050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, D.; Zhang, W.; Huang, C.; Chen, J.; He, W.; Wang, A.; Li, B.; Zhu, X. Ursolic Acid Ameliorates CCl₄-Induced Liver Fibrosis through the NOXs/ROS Pathway. Journal of Cellular Physiology 2018, 233(10), 6799–6813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quan, H. Y.; Kim, D. Y.; Kim, S. J.; Jo, H. K.; Kim, G. W.; Chung, S. H. Betulinic acid alleviates non-alcoholic fatty liver by inhibiting SREBP1 activity via the AMPK–mTOR–SREBP signaling pathway. Biochemical Pharmacology 2013, 85, 1330–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Wu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, S.; Ding, Y.; Deng, X.; Feng, R.; Li, J.; Ma, T.; Huang, C. Betulinic acid prevents liver fibrosis by binding Lck and suppressing Lck in HSC activation and proliferation. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2022, 296, 115459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K. D.; Jung, H. Y.; Ryu, H. G.; Kim, B.; Jeon, J.; Yoo, H. Y.; Park, C. H.; Choi, B. H.; Hyun, C. K.; Kim, K. T.; Fang, S.; Yang, S. H.; Kim, J. B. Betulinic acid inhibits high-fat diet-induced obesity and improves energy balance by activating AMPK. Nutrition, Metabolism & Cardiovascular Diseases 2019, 29, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, S.; Fan, S.; Yang, L.; Tong, Q.; Ji, G.; Huang, C. Betulinic acid alleviates endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated nonalcoholic fatty liver disease through activation of farnesoid X receptors in mice. British Journal of Pharmacology 2019, 176, 847–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, Y.; Wu, Y.-L.; Lian, L.-H.; Xie, W.-X.; Li, X.; OuYang, B.-Q.; Bai, T.; Li, Q.; Yang, N.; Nan, J.-X. The anti-fibrotic effect of betulinic acid is mediated through the inhibition of NF-κB nuclear protein translocation. Chemico-Biological Interactions 2012, 195, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Q.; Wang, H.; Tong, L.; Fang, Q.; Xiang, M.; Han, L.; Jin, L.; Yang, J.; Qian, Z.; Ning, G.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Z. Betulinic acid improves nonalcoholic fatty liver disease through YY1/FAS signaling pathway. The FASEB Journal 2020, 34, 13033–13048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ge, X.; Jiao, T.; Yin, J.; Wang, K.; Li, C.; Guo, S.; Xie, X.; Xie, C.; Nan, F. Discovery of betulinic acid derivatives as potent intestinal farnesoid X receptor antagonists to ameliorate nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2022, 65, 13452–13472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S. L.; Yang, H. T.; Lee, Y. J.; Lin, C. C.; Chang, M. H.; Yin, M. C. Asiatic acid ameliorates hepatic lipid accumulation and insulin resistance in mice consuming a high-fat diet. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2014, 62, 4625–4631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Lao, L.; Pang, X.; Qiao, Q.; Pang, L.; Feng, Z.; Bai, F.; Sun, X.; Lin, X.; Wei, J. Asiatic acid from Potentilla chinensis alleviates non-alcoholic fatty liver by regulating endoplasmic reticulum stress and lipid metabolism. International Immunopharmacology 2018, 65, 256–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Chen, Q.; Guo, A.; Fan, J.; Wang, R.; Zhang, H. Asiatic acid attenuates CCl₄-induced liver fibrosis in rats by regulating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR and Bcl-2/Bax signaling pathways. International Immunopharmacology 2018, 60, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.-K.; Kim, J.-H.; Park, K.-M.; Oh, K.-H.; Oh, U.; Hwang, S.-J. Preparation and evaluation of a titrated extract of Centella asiatica injection in the form of an extemporaneous micellar solution. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 1997, 146, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y. H.; Chen, M. C.; Liu, F.; Xu, Z.; Tian, X. T.; Xie, Y.; Huang, C. G. Synthesis and cytotoxic activity of novel C-23-modified asiatic acid derivatives. Molecules 2020, 25, 3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. F.; Huang, R. Z.; Yao, G. Y.; Ye, M. Y.; Wang, H. S.; Pan, Y. M.; Xiao, J. T. Synthesis and biological evaluation of novel aniline-derived asiatic acid derivatives as potential anticancer agents. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2014, 86, 175–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, Y.; Wang, G.; Ge, Y.; Xu, M.; Gong, Z. Synthesis, anti-tumor and anti-angiogenic activity evaluations of asiatic acid amino acid derivatives. Molecules 2015, 20, 7309–7324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jew, S. S.; Yoo, C. H.; Lim, D. Y.; Kim, H.; Mook-Jung, I.; Jung, M. W.; Choi, H.; Jung, Y. H.; Kim, H.; Park, H. G. Structure-activity relationship study of asiatic acid derivatives against beta amyloid (Aβ)-induced neurotoxicity. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 2000, 10, 119–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyakudya, T,T,; Mukwevho, E.; Nkomozepi, P.; Erlwanger, K.H. Neonatal intake of oleanolic acid attenuates the subsequent development of high fructose diet-induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in rats. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease 2018, 9, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-N.; Chang, H.-Y.; Wang, C. C. N.; Chu, F.-Y.; Shen, H.-Y.; Chen, C.-J.; Lim, Y.-P. Oleanolic acid inhibits liver X receptor alpha and pregnane X receptor to attenuate ligand-induced lipogenesis. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2018, 66, 10964–10976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Zuo, G.; Xu, W.; Gao, H.; Yang, Y.; Yamahara, J.; Wang, J.; Li, Y. Oleanolic acid diminishes liquid fructose-induced fatty liver in rats: role of modulation of hepatic sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c–mediated expression of genes responsible for de novo fatty acid synthesis. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine 2013, 2013, 534084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djeziri, F. Z.; Belarbi, M.; Murtaza, B.; Hichami, A.; Benammar, C.; Khan, N. A. Oleanolic acid improves diet-induced obesity by modulating fat preference and inflammation in mice. Biochimie 2018, 152, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyakudya, T. T.; Mukwevho, E.; Nkomozepi, P.; Erlwanger, K. H. Neonatal intake of oleanolic acid attenuates the subsequent development of high fructose diet-induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in rats. Journal of Developmental Origins of Health and Disease 2018, 9, 500–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, R.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Liao, N.; Wang, Z.; Li, W.; Qin, X.; Hai, C. Oleanolic acid improves hepatic insulin resistance via antioxidant, hypolipidemic and anti-inflammatory effects. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology 2013, 376, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamede, M.; Mabuza, L.; Ngubane, P.; Khathi, A. Plant-derived oleanolic acid ameliorates markers associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in a diet-induced pre-diabetes rat model. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity: Targets and Therapy 2019, 12, 1953–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Wang, M.; Zhang, J.; Luo, X.; Yuan, C.; Bai, R.; Wang, T.; Xi, Y.; Li, C.; Ke, D.; Yamahara, J.; Li, Y.; Yi, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, J. Oleanolic acid inhibits SCD1 gene expression to ameliorate fructose-induced hepatosteatosis through SREBP1c-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research 2023, 67, e2200533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Li, Y.; Lv, H.; Zhang, L.; Bi, C.; Dong, N.; Shan, A.; Wang, J. Oleanolic acid targets the gut–liver axis to alleviate metabolic disorders and hepatic steatosis. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2021, 69, 7884–7897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, X.; Zuo, H.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, W.; Zhou, H.; Deng, L.; Song, H. Oleanolic acid alleviates ischemia–reperfusion injury in rat severe steatotic liver via KEAP1/NRF2/ARE signaling. International Immunopharmacology 2024, 138, 112617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pi, Y.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Q.; Zheng, W.; Zhou, H.; Deng, L.; Xu, N.; Song, H. Oleanolic acid alleviates intestinal injury after hepatic ischemia–reperfusion under steatosis via PPARG-dependent M2 macrophage polarization. International Immunopharmacology 2026, 171, 116162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Yang, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, C. H.; Feng, Y.; Ye, B.; Li, D. Celastrol ameliorates metabolic dysfunction–associated steatohepatitis by regulating the CYP7B1-mediated alternative bile acid synthetic pathway. Phytomedicine 2025, 147, 157172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Chen, J.; Ye, C.; Lin, B.; Zhang, T.; Chen, Q.; Yu, C.; Wan, X. Celastrol ameliorates fibrosis in Western diet/tetrachloromethane-induced nonalcoholic steatohepatitis by suppressing Notch/osteopontin signaling. Phytomedicine 2025, 137, 156369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, C. Celastrol stabilizes glycolipid metabolism in hepatic steatosis by binding and regulating the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ signaling pathway. Metabolites 2024, 14, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, J.; Liu, Y.; Liu, B.; Jia, X.; Fang, X.; Qin, S.; Zhang, Y. Celastrus orbiculatus Thunb. extracts and celastrol alleviate NAFLD by preserving mitochondrial function through activating the FGF21/AMPK/PGC-1α pathway. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2024, 15, 1444117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L. P.; Sun, B.; Li, C. J.; Xie, Y.; Chen, L. M. Effect of celastrol on toll-like receptor 4–mediated inflammatory response in free fatty acid–induced HepG2 cells. International Journal of Molecular Medicine 2018, 42, 2053–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Ge, H. Y.; Gu, Y. J.; Cao, F. F.; Yang, C. X.; Uzan, G.; Peng, B.; Zhang, D. H. Celastrol reverses palmitic acid–caused TLR4–MD2 activation-dependent insulin resistance via disrupting MD2-related cellular binding to palmitic acid. Journal of Cellular Physiology 2018, 233, 6814–6824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J. E.; Lee, M. H.; Nam, D. H.; Song, H. K.; Kang, Y. S.; Lee, J. E.; Kim, H. W.; Cha, J. J.; Hyun, Y. Y.; Han, S. Y.; Han, K. H.; Han, J. Y.; Cha, D. R. Celastrol, an NF-κB inhibitor, improves insulin resistance and attenuates renal injury in db/db mice. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e62068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Xu, L.; Alberobello, A. T.; Gavrilova, O.; Bagattin, A.; Skarulis, M.; Liu, J.; Finkel, T.; Mueller, E. Celastrol protects against obesity and metabolic dysfunction through activation of a HSF1–PGC1α transcriptional axis. Cell Metabolism 2015, 22, 695–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canová, N.; Šípková, J.; Arora, M.; Pavlíková, Z.; Kučera, T.; Šeda, O.; Šopin, T.; Vacík, T.; Slanař, O. Effects of celastrol on the heart and liver galaninergic system expression in a mouse model of Western-type diet-induced obesity and metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease and steatohepatitis. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2025, 16, 1476994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmouna, M.; Benammar, C.; Khan, A. S.; Djeziri, F. Z.; Hichami, A.; Khan, N. A. Celastrol improves preference for a fatty acid, and taste bud and systemic inflammation in diet-induced obese mice. Nutrients 2025, 17, 1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Wang, H. J.; Yu, J.; Li, T.; Han, Y. Protective effect of celastrol on type 2 diabetes mellitus with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in mice. Food Science & Nutrition 2020, 8, 6207–6216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Geng, C.; Liu, X.; Li, M.; Gao, M.; Liu, X.; Fang, F.; Chang, Y. Celastrol ameliorates liver metabolic damage caused by a high-fat diet through Sirt1. Molecular Metabolism 2017, 6, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, M.; Takeuchi, N.; Kotani, S.; Kumagai, A. Effects of glycyrrhizin and cortisone on cholesterol metabolism in the rat. Endocrinologia Japonica 1970, 17, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negishi, M.; Irie, A.; Nagata, N.; Ichikawa, A. Specific binding of glycyrrhetinic acid to the rat liver membrane. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1991, 1066, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, W. Y.; Chia, Y. Y.; Liong, S. Y.; Ton, S. H.; Kadir, K. A.; Husain, S. N. Lipoprotein lipase expression, serum lipid and tissue lipid deposition in orally administered glycyrrhizic acid-treated rats. Lipids in Health and Disease 2009, 8, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eu, C. H.; Lim, W. Y.; Ton, S. H.; Abdul Kadir, K. Glycyrrhizic acid improved lipoprotein lipase expression, insulin sensitivity, serum lipid and lipid deposition in high-fat diet-induced obese rats. Lipids in Health and Disease 2010, 9, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaw, H. P.; Ton, S. H.; Chin, H. F.; Karim, M. K.; Fernando, H. A.; Kadir, K. A. Modulation of lipid metabolism in glycyrrhizic acid-treated rats fed on a high-calorie diet and exposed to short- or long-term stress. International Journal of Physiology, Pathophysiology and Pharmacology 2015, 7, 61–75. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L.; Guo, S.; Zhang, S.; Gao, X.; Liu, A.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wen, A. Glycyrrhetinic acid attenuates disturbed vitamin A metabolism in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease through AKR1B10. European Journal of Pharmacology 2020, 883, 173167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Duan, X.; Sun, X.; Liu, Z.; Sun, P.; Yang, X.; Sun, H.; Liu, K.; Meng, Q. Protective effects of glycyrrhizic acid from edible botanical Glycyrrhiza glabra against non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. Food & Function 2016, 7, 3716–3723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Chen, S.; Wei, Y.; Sun, Y.; Yang, Y.; Lin, B.; Li, Y.; Wang, C. Glycyrrhizic acid restores the downregulated hepatic ACE2 signaling in the attenuation of mouse steatohepatitis. European Journal of Pharmacology 2024, 967, 176365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Yi, Y.; Lin, B.; Qiu, Z.; Wang, C.; Li, Y. Glycyrrhizic acid mitigates hepatocyte steatosis and inflammation through ACE2 stabilization via dual modulation of AMPK activation and MDM2 inhibition. European Journal of Pharmacology 2025, 1002, 177817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou-Yang, Q.; Xuan, C. X.; Wang, X.; Luo, H. Q.; Liu, J. E.; Wang, L. L.; Li, T. T.; Chen, Y. P.; Liu, J. 3-Acetyl-oleanolic acid ameliorates non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in high fat diet-treated rats by activating AMPK-related pathways. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica 2018, 39, 1284–1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, Q.; Wu, J.; Li, J. X. Oleanolic acid derivative HA-20 inhibits adipogenesis in a manner involving PPARγ-FABP4/aP2 pathway. Journal of Molecular Endocrinology 2021, 66, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Bao, Y.; Niu, S.; Wang, S.; Li, Y.; He, H.; Zhang, N.; Fang, W. Structure optimization of 12β-O-γ-glutamyl oleanolic acid derivatives resulting in potent FXR antagonist/modulator for NASH therapy. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radwan, M. O.; Kadasah, S. F.; Aljubiri, S. M.; Alrefaei, A. F.; El-Maghrabey, M. H.; El Hamd, M. A.; Tateishi, H.; Otsuka, M.; Fujita, M. Harnessing oleanolic acid and its derivatives as modulators of metabolic nuclear receptors. Biomolecules 2023, 13, 1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira Eloy, J.; Saraiva, J.; de Albuquerque, S.; Marchetti, J. M. Solid dispersion of ursolic acid in Gelucire 50/13: a strategy to enhance drug release and trypanocidal activity. AAPS PharmSciTech 2012, 13, 1436–1445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, L.; Sun, C.; Zhu, X.; Xu, W.; Yu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Dushkin, A. V.; Su, W. Inositol hexanicotinate self-micelle solid dispersion is an efficient drug delivery system in the mouse model of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2021, 602, 120576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soica, C.; Oprean, C.; Borcan, F.; Danciu, C.; Trandafirescu, C.; Coricovac, D.; Crăiniceanu, Z.; Dehelean, C. A.; Munteanu, M. The synergistic biologic activity of oleanolic and ursolic acids in complex with hydroxypropyl-γ-cyclodextrin. Molecules 2014, 19, 4924–4940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Hu, D.; Zhang, D.; Xu, G.; Wu, D.; Gao, C.; Meng, L.; Feng, X.; Cheng, W.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Tang, X. Encapsulation of oleanolic acid into cyclodextrin metal-organic frameworks by co-crystallization: preparation, structure characterization and its effect on a zebrafish larva NAFLD model. Food Research International 2025, 204, 115936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X. J.; Hu, X. M.; Yi, Y. M.; Wan, J. Preparation and body distribution of freeze-dried powder of ursolic acid phospholipid nanoparticles. Drug Development and Industrial Pharmacy 2009, 35, 305–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Ding, J.; Xu, H.; Dai, X.; Hou, Z.; Zhang, K.; Sun, K.; Sun, W. Delivery of ursolic acid in polymeric nanoparticles effectively promotes the apoptosis of gastric cancer cells through enhanced inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2013, 441, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldeira de Araújo Lopes, S.; Novais, M. V. M.; Teixeira, C. S.; Honorato-Sampaio, K.; Pereira, M. T.; Ferreira, L. A.; Braga, F. C.; Oliveira, M. C. Preparation, physicochemical characterization, and cell viability evaluation of long-circulating and pH-sensitive liposomes containing ursolic acid. BioMed Research International 2013, 2013, 467147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Yang, X.; Xie, J.; Xiang, L.; Li, Y.; Ou, M.; Chi, T.; Liu, Z.; Yu, S.; Gao, Y.; Chen, J.; Shao, J.; Jia, L. UP12, a novel ursolic acid derivative with potential for targeting multiple signaling pathways in hepatocellular carcinoma. Biochemical Pharmacology 2015, 93, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Li, Z.; Xie, X.; Wang, C.; You, J.; Mo, F.; Jin, B.; Chen, J.; Shao, J.; Chen, H.; Jia, L. Dendrimeric anticancer prodrugs for targeted delivery of ursolic acid to folate receptor-expressing cancer cells. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2015, 70, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alvarado, H. L.; Abrego, G.; Garduño-Ramirez, M. L.; Clares, B.; Calpena, A. C.; García, M. L. Design and optimization of oleanolic/ursolic acid-loaded nanoplatforms for ocular anti-inflammatory applications. Nanomedicine 2015, 11, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zheng, D.; Ding, J.; Xu, H.; Li, X.; Sun, W. Efficient delivery of ursolic acid by poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone)-block-poly(ε-caprolactone) nanoparticles for inhibiting the growth of hepatocellular carcinoma in vitro and in vivo. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2015, 10, 1909–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Pi, J.; Yang, F.; Wu, C.; Cheng, X.; Bai, H.; Huang, D.; Jiang, J.; Cai, J.; Chen, Z. W. Ursolic acid-loaded chitosan nanoparticles induce potent anti-angiogenesis in tumor. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2016, 100, 6643–6652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pi, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, H.; Gu, X.; Wang, S.; Zhang, B.; Luan, H.; Zhu, Z. Ursolic acid nanocrystals for dissolution rate and bioavailability enhancement: influence of different particle size. Current Drug Delivery 2016, 13, 1358–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baishya, R.; Nayak, D. K.; Kumar, D.; Sinha, S.; Gupta, A.; Ganguly, S.; Debnath, M. C. Ursolic acid loaded PLGA nanoparticles: in vitro and in vivo evaluation to explore tumor targeting ability on B16F10 melanoma cell lines. Pharmaceutical Research 2016, 33, 2691–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, N.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, X.; Song, Q.; Shen, Y.; Shum, H. C.; Wang, Y.; Rong, J. Celastrol-loaded lactosylated albumin nanoparticles attenuate hepatic steatosis in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Journal of Controlled Release 2022, 347, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, N.; Zhao, J.; Zhao, W.; Shen, Y.; Song, Q.; Shum, H. C.; Wang, Y.; Rong, J. Biodegradable celastrol-loaded albumin nanoparticles ameliorate inflammation and lipid accumulation in diet-induced obese mice. Biomaterials Science 2022, 10, 984–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, T.; Gan, X.; Luo, J.; Shi, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Chen, J.; Yu, C. Hyaluronic acid act as drug self-assembly chaperone and co-assembled with celastrol for ameliorating non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2024, 282, 137289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ouyang, H.; Gong, T.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, X.; Fu, Y. Targeted delivery of celastrol via chondroitin sulfate-derived hybrid micelles for alleviating symptoms in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. ACS Applied Bio Materials 2023, 6, 4877–4893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, C.; Zhu, H.; Wang, K.; Hu, H.; Wei, X.; Xu, D.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J.; Shen, Y.; Qiu, N.; Xu, X. Oral celastrol micelles forming high-density lipoprotein corona targeting hepatocytes for MASLD treatment. Advanced Science 2025, 12, e00854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sasaki, K.; Yonebayashi, S.; Yoshida, M.; Shimizu, K.; Aotsuka, T.; Takayama, K. Improvement in the bioavailability of poorly absorbed glycyrrhizin via various non-vascular administration routes in rats. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2003, 265, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Compound | Triterpene class | Main molecular mechanisms | Experimental model | Main outcomes | Key references |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ursolic acid | Ursane | AMPK activation; inhibition of TGF-β/SMAD and NLRP3; antioxidant effects | HFD, MCD, CCl₄, TAA MASLD/MASH models | Reduced steatosis, inflammation, fibrosis; improved liver enzymes | [20,119,120] |

| Betulinic acid | Lupane | AMPK and FXR activation; inhibition of SREBP-1c, YY1/FAS; antifibrotic | HFD- and MCD-fed mice; TAA/CCl₄ fibrosis | Attenuation of steatosis, insulin resistance, fibrosis | [126,129,131] |

| Asiatic acid | Ursane | NF-κB and PI3K/AKT/mTOR inhibition; ER stress reduction | HFD-fed mice; CCl₄-induced MASH | Reduced lipid accumulation, inflammation, oxidative stress | [133,134,135] |

| Oleanolic acid | Oleanane | PPARα activation; NF-κB inhibition; lipogenesis suppression | High-fructose and HFD steatosis models | Improved insulin sensitivity; reduced hepatic lipid content | [142,143,149] |

| Celastrol | Quinone methide triterpenoid | AMPK activation; SREBP-1c/FASN suppression; NLRP3 and HMGB1/NF-κB inhibition | Diet-induced MASH mouse models | Reduced steatosis, inflammation and fibrosis | [152,155,157] |

| Glycyrrhizin / Glycyrrhetinic acid | Oleanane-type saponin/metabolite | NF-κB, MAPK and NLRP3 inhibition; bile acid homeostasis modulation | MCD-induced MASH; chronic hepatitis clinical use | Attenuation of inflammation and fibrosis; hepatoprotection | [164,169,171,172] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).