1. Introduction

The vadose zone (the unsaturated zone) lies between the land surface and the groundwater table. It plays a crucial role in controlling the movement of nutrients and contaminants to groundwater, as well as in groundwater recharge. As an integral part of the critical zone, the Earth's outer layer where rock, soil, water, air, and living organisms interact, the vadose zone significantly influences how climate change affects the overall health of ecosystems. Central to all these processes is the movement of water within the vadose zone.

Downward water flow in vadose zone is often associated with so-called preferential flow that is non-uniform, can bypass significant portion of soils, and thus results in rapid water flow and solute transport from the ground surface to water table for a given water flux at the ground surface [

1]. Two primary processes drive this phenomenon. The first involves macropores that facilitate swift water movement that is not in the hydraulic equilibrium with surrounding soil matrix [

2,

3]. The second process is gravitational fingering, which arises from instabilities at the wetting front during infiltration, leading to finger-like patterns of flow [

4,

5,

6,

7]. In real-world settings, both mechanisms may operate simultaneously, complicating the prediction and modeling of preferential flow. Developing robust and theoretically sound models to accurately represent these complex flow dynamics remains a significant scientific challenge [

8].

This work focuses on gravitational fingering flow in homogeneous unsaturated soils. The traditional theory for water flow in unsaturated soil is valid under the local equilibrium condition. A discussion of local equilibrium concept within the context of thermodynamics can be found in Glansdorff and Prigogine [

9]. A practical definition of local equilibrium, within a context of numerical modeling, is that capillary pressure and water saturation are relatively uniform within a numerical grid block such that the state of water distribution within the block can be adequately represented by average water saturation there. This is the fundamental reason why relative permeability is only a function of capillary pressure or water saturation under local equilibrium conditions. However, this assumption breaks down when fingering flow occurs within a grid block, necessitating a different theoretical framework to accurately describe the water flow process. While much research has focused on preferential flow related to macropores, there has been relatively limited progress in developing a macroscopic theory or modeling approach for fingering flow.

The optimality-based ARM has been developed as a macroscopic theory for fingering flow in the vadose zone [

7,

10,

11]. It divides the representative elementary volume into two distinct zones: active and inactive regions. The active region is characterized by fingering water flow, while the inactive region remains bypassed. The macroscopic relation between soil water flux and the hydraulic gradient was derived from the principle of optimality that soil water flow pattern is self-organized to maximize the flow conductivity [

7,

10,

11]. Optimality is deeply rooted in non-linear thermodynamics. Unlike the traditional theory for water flow, where conductivity is a function of capillary pressure or water saturation, hydraulic conductivity for fingering flow in ARM is also a power function of water flux.

The development of ARM was motivated by the demonstrated effectiveness of the Active Fracture Model (AFM) in simulating macroscopic water flow through the unsaturated zone at Yucca Mountain, where dense fractures can be treated as a continuum for water movement [

7,

12]. Since its inception, ARM has undergone extensive verification from multiple perspectives. The optimality-based ARM has been shown to align mathematically with the fractal characteristics of fingering flow patterns commonly observed in practice [

11,

13]. Its relationship between the fingering flow fraction and water flux matches well with laboratory observations [

14]. Most recently, Liu et al. [

15] demonstrated that ARM can reliably reproduce field results from dye infiltration experiments using only laboratory-measured soil properties, without the need for additional tunable parameters. (The related ARM simulator is available from

https://github.com/blander996/Active-Region-Model.git.) This highlights ARM’s robustness and practicality for modeling fingering flow dynamics in natural soils. ARM has also been found useful for modeling field scale flow and transport in vadose zone by Sheng et al. [

16], Engstrom and Liu [

17] and Chen et al. [

18], although further field evaluations of AEM under diverse conditions are warranted. Additionally, the optimality principle underlying ARM has been successfully applied to predict density-driven fingering transport rates (convective flux) for CO₂ storage in saline aquifers [

19]. The success of the optimality principle in describing fingering phenomena across distinct contexts further strengthens validity of ARM’s physics foundation.

This study presents two latest theoretical developments of ARM. The mathematical derivation of the ARM relationship has been continuously updated and refined while the final results remain unchanged, because certain approximation is needed in the derivation [

7,

10,

11]. For the completeness and transparency, this short communication provides the more rigorous derivation of ARM’s relationship between water flux and hydraulic gradient based on the optimality. Also, in the previous studies related to ARM, water is considered immobile within the non-fingering zone. In some field-scale contexts, the non-fingering flow zone, however, does carry a small flux, albeit much slower than in the fingers. Thus, ARM is further extended in this study to cases in which water flow is allowed to occur in the non-fingering flow zone. Hopefully, these new developments provide a more general and realistic ARM framework for modeling macroscopic fingering flow in the vadose zone.

2. The Relationship between Water Flux and Hydraulic Gradient

Modeling vadose-zone flow requires relating water flux to the hydraulic gradient. Under local equilibrium, this relationship is given by the Darcy–Buckingham law. Because Darcy–Buckingham law fails at macroscale when fingering occurs, deriving a macroscopic relation for the ARM requires an additional principle. This section derives the relation using the optimality principle: water in unsaturated soils organizes its flow to minimize global resistance or maximize conductivity.

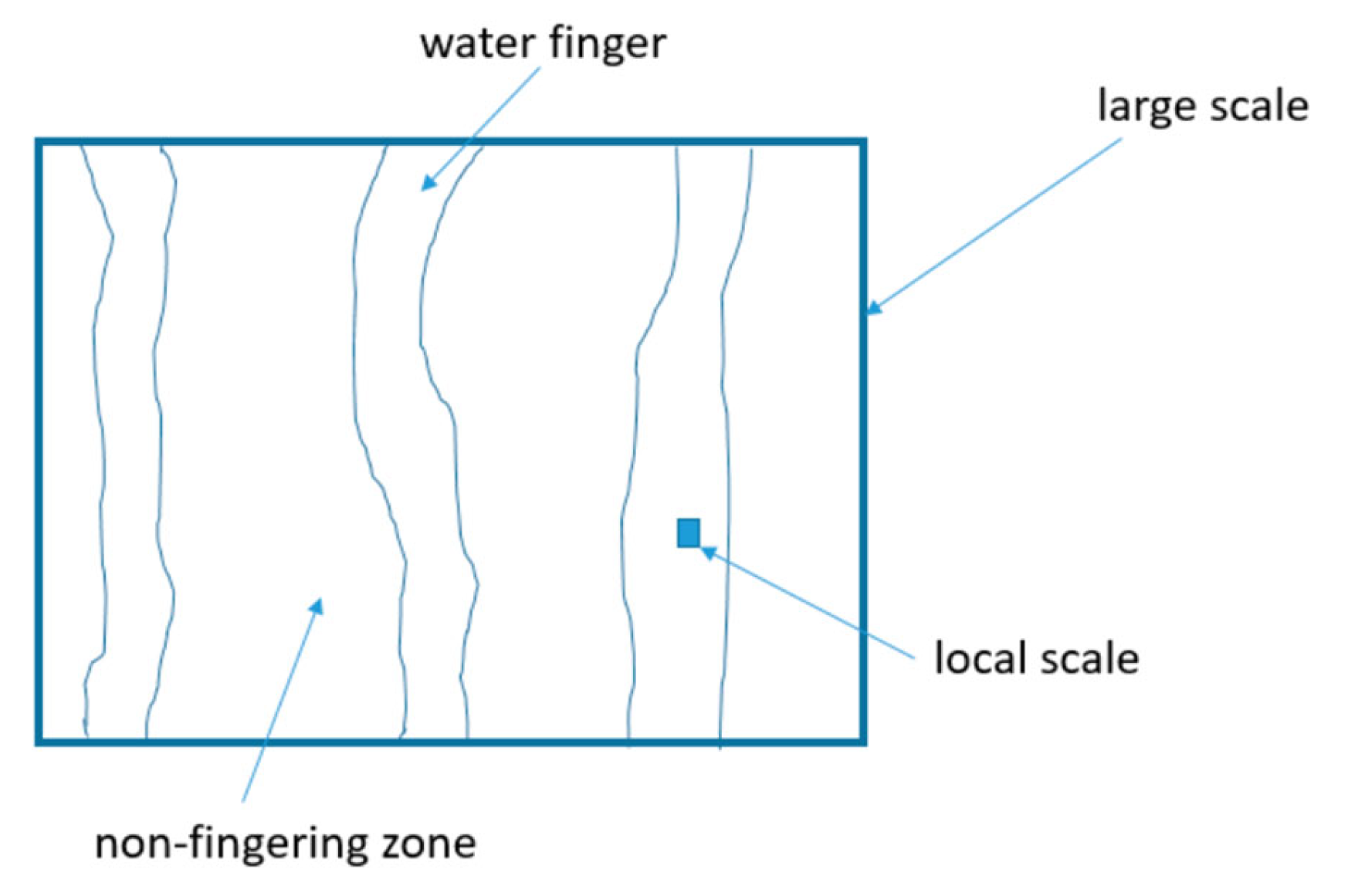

Following the common practice for determining large-scale flow parameters (e.g., [

20]), we focus on the steady-state flow process, given that this work emphasizes the fully developed fingering flow. The steady-state water flow equation on the large scale (

Figure 1) for a

homogeneous and isotropic porous medium is given as

where

x and

y are the two horizontal coordinate axes,

z is the vertical axis, and

qx, qy and

qz are large-scale Darcy flux along

x,

y and

z directions, respectively.

The expression for energy expenditure rate needs to be derived for applying the optimality principle. The energy of unit weight of liquid water (or hydraulic head) in a porous medium,

E, is given by

where

h is the average capillary pressure head within the fingering flow zone (

Figure 1). For a unit volume of porous medium, the energy expenditure rate is given as

Combining Equations.(1) and (3) yields

Therefore, the rate of water energy loss is represented by a product of water flux and energy gradient or hydraulic gradient.

Following Liu [

7,

10,

11], we assume that the

mathematical form of Darcy-Buckingham law is still applicable to fingering process at the large scale:

The major difference between Liu [

7,

10,

11] and the traditional unsaturated flow theory is the expression for hydraulic conductivity (

K). Conventionally,

K is a function of water saturation or capillary pressure only in the Darcy-Buckingham law. This is a direct consequence of the local equilibrium assumption, which is not valid for modeling fingering flow on a large scale. Local equilibrium refers to the existence of thermodynamic equilibrium within a representative elementary volume (REV). (A numerical grid block size should be larger than or equal to REV and different sizes of REV may exist at different scales [

21].) In other words, temperature, fluid saturation and capillary pressure are always uniformly distributed within REV under local equilibrium conditions (e.g., the local scale shown in

Figure 1). In contrast, non-equilibrium means that thermodynamic equilibrium does not exist within REV containing sub-grid fingering (e.g., the large-scale shown in

Figure 1). Thus, the water distribution within the large-scale REV (

Figure 1) cannot be uniquely determined by water saturation or capillary pressure alone. ARM is a continuum model associated with the large-scale REV (

Figure 1). In this case, additional large-scale variables are needed to accurately determine the state of sub-grid water distribution. Water flux is a logical choice because it is highly relevant to the fingering flow process. Following Liu [

7,

10,

11], we use the square of the energy gradient as the additional variable to determine the large-scale conductivity for mathematical convenience. This is equivalent to the use of water flux because water flux and the energy gradient are related to each other (Equation (5)). Here, the large-scale hydraulic conductivity is given by

where

Ks is saturated hydraulic conductivity and the square of the energy gradient

is defined by

Based on Equations (4), (5) and (7), we can write the total energy expenditure rate for the whole flow domain as

The optimality principle is used to derive the explicit relationship between K, h, and (Equation (6)). Note that is always negative because gained water energy is considered positive in this study. When applying the optimality principle regarding the minimization of global flow resistance (or the maximum conductivity), absolute value of the total energy expenditure rate can either be minimized or maximized, depending on the boundary conditions. For fixed energy values at the boundaries, the minimum flow resistance allows the maximum water flux, resulting in the maximum absolute value of the energy expenditure rate or the maximum entropy production under isothermal conditions. Conversely, for fixed flux values at the boundaries, the minimum flow resistance leads to the minimum absolute value of the energy gradient along the flow path, resulting in the minimum absolute value of the energy expenditure rate as well. These outcomes are direct results of the definition of the energy expenditure rate, which is the product of water flux and energy gradient. Here, we use boundary conditions with fixed energy values, which, as shown later, enable the derivation of mathematically tractable results. Intuitively, optimal conductivity should not depend on the specific boundary conditions used in the derivation.

The calculus of variations is employed here to address the extremum problems of Equation (8). While we refer to relevant mathematical books for detailed information on calculus of variations (e.g., [

22]), some pertinent results are briefly presented here. Consider a functional (

Iw) with an unknown function (

w):

where function

L is called the Lagrangian, and

wx, w y, and

wz are derivatives of

w with respect to

x, y, and

z, respectively. When

Iw reaches its extrema, the Euler equation [

22] can be used for determining the unknown function

w:

Note that the Euler equation above holds only when

w has fixed values or satisfies the following condition at boundaries:

Equations (9) and (10) are applied to a functional with one unknown function. When there are more than one unknown functions, Equation (10) will apply to each one of these functions (e.g., [

22]).

The following Lagrangian function is obtained from Equation (8):

The second term on the right-hand side is a constraint from Equation (7) and the Lagrange multiplier is a function here. The constraint related to the water flow equation (Equation (1)) is not included in Equation (12) and will be delt with later.

Since the Lagrangian function does not directly involve the derivative of

with respect to

x,

y and

z,

satisfies Equation (11). Then Equation (10) can be applicable when replacing

w with

. Inserting Equation (12) into Equation (11) gives:

Here, we consider a boundary condition with

E values being fixed at boundaries. Thus, Equation (10) is applicable when replacing

w with

E. Inserting Equation (12) into (10) and using Equations (13) and (1) yield:

Note that

in the above equation was replaced by

in Liu [

7,

11]. Equation (14) is mathematically more accurate.

If the term on the right-hand side of Equation (14) is zero or negligible for gravity-dominant water flow, an analytical relationship for the large-scale hydraulic conductivity can be obtained [

7,

11]. Change in

E largely results from change in

z while

h only contributes to a relatively small portion of changes in

E, which is the nature of gravity dominated water flow that is mainly along the vertical direction. Specifically in Equation (2),

E is the summation of

z and

h; the former is the contribution from gravity and the latter from capillary force which is weak for gravity dominated fingering flow. Considering that

K is related to

h and not to

z (Equation (6)), its relationship with

E herein should be weak and thus the derivative of

K with respect to

E is approximately negligible. To illustrate this point with a special case, consider two close elevations in

Figure 1 where the capillary pressure heads and fractions of fingering flow zone are the same at the two locations. Here,

E will be different at these two locations because of the

z difference (Equation (2)), but

K remains the same given that it only depends on

h and the fraction of fingering flow zone, as will be discussed later. Thus,

holds for this special case because the change in

E does not result in the change in

K. Nevertheless,

should be considered an approximation for a general case. Validity of considering

K to be a weak function of

E is further verified by excellent agreements between the related theoretical results derived from it and experimental observations [

11,

14,

15].

When the term on the right-hand side of Equation (14) drops, the equation becomes

Note that Equation (1) can be rewritten as

Equation (15) outlines the partial differential equation that

K must satisfy according to the optimality principle. However, the derivation of Equation (15) does not consider the constraints imposed by the water flow equation (Equation (1) or (16)), as previously mentioned. By comparing Equations (15) and (16), it becomes evident that the water flow equation (Equation (16)) is also satisfied when

where is a constant.

Following Liu [

7], we approximately rewrite the mathematical form of

K with

where

and

are functions of

h and

S*, respectively. Inserting Equation (18) into Equation (17) gives

According to Equation (5), the above equation can be further rewritten as

where

q is the magnitude of water flux defined by

Then relationship of large-scale hydraulic conductivity is obtained by inserting Equation (20) into Equation (18):

where

Fh is a function of

h and

a is a constant. The term

in Equation (22) is considered relative permeability on the local scale (

Figure 1) simply because it is only a function of

h or the capillary pressure head in fingering flow zone. The power function term represents the fraction of fingering flow zone in the cross section normal to the flux direction [

7,

10,

11]:

The parameter

a value seems to be in a narrow range (0.4 to 0.5) for different types of soils according to the data collected from both laboratory experiments and field tests [

11,

14,

15].

The large-scale hydraulic conductivity being a function of flux, as shown in Equation (22), aligns with the behavior of other unstable flow processes, such as turbulent flow. Liu [

7] compared Equation (22) to the expression of water viscosity in hydrodynamics literature, considering conductivity and viscosity as conceptual analogues. For comparison purposes, laminar water flow and turbulent flow in hydrodynamics correspond to uniform flow (or non-fingering flow) in unsaturated soils and fingering flow, respectively. For the uniform flow in unsaturated soils, hydraulic conductivity is solely a function of water saturation, which is like water viscosity in laminar flow that is a sole property of water, independent of water velocity. However, in turbulent flow, the apparent viscosity is related to the Reynolds number (

Re), which is a function of water velocity. Therefore, it is not surprising that conductivity for fingering flow in the vadose zone depends on water flux as well, as both fingering flow in unsaturated soils and turbulent flow in hydrodynamics belong to the same flow regime: unstable flow. Additionally, just as different constitutive models exist for laminar and turbulent flow regimes in hydrodynamics, we need to develop a theoretical framework for large-scale fingering flow, alongside the framework for uniform flow (Darcy-Buckingham law), to fully describe water flow in all regimes in the vadose zone. This will be further discussed in the next section.

For a positive value of a, Equation (22) suggests that locations with high water fluxes will also have high conductivity values, thereby minimizing global flow resistance. This concept aligns with our everyday experiences. For instance, to optimize traffic transportation efficiency, highways are designed with more lanes in areas with high traffic flow. In this analogy, highway networks resemble fingering flow paths, with traffic flux and the number of lanes corresponding to water flux and hydraulic conductivity, respectively.

The final optimality-based relationship between soil water flux and energy or hydraulic gradient is obtained as follows by combining Equations (5) and (22):

where bold characters are vectors,

f is given by Equation (23) and

, identical to

in Equation (22), represents local-scale water relative permeability and can be determined by the van Genuchten [

23] equation with water saturation or capillary pressure in the fingering zone. Although the water flux term occurs on both sides of the equation, Equation (22) is convenient for use in practice and its physics meanings are also relatively easy to understand because

f, the fraction of fingering flow zone, is explicitly present in the equation. This is especially useful for modeling solute transport with the ARM given that

f is a key parameter for determining the pore velocity [

17].

To avoid the flux term on the right hand of Equation (24), it can be rewritten as follows

where bold characters are again vectors. Note that for

a = 0 (or

f =1) Equation (25) is reduced to Darcy-Buckingham law. Although Equation (25) is mathematically identical to Equation (24), the relation between water flow patterns associated with gravitational fingering is more difficult to visualize from Equation (25). Nevertheless, one important implication from Equation (25) is that from a small scale to a large scale it is not enough to upscale flow parameters with mathematical forms of fundamental laws being assumed to be the same across scales. For example, at a local scale within a finger, Darcy-Buckingham law holds because of the existence of the local equilibrium at that scale. However, a different form of flux-gradient relationship (Equation (25)) needs to be used for a larger scale involving multiple fingers within each grid block.

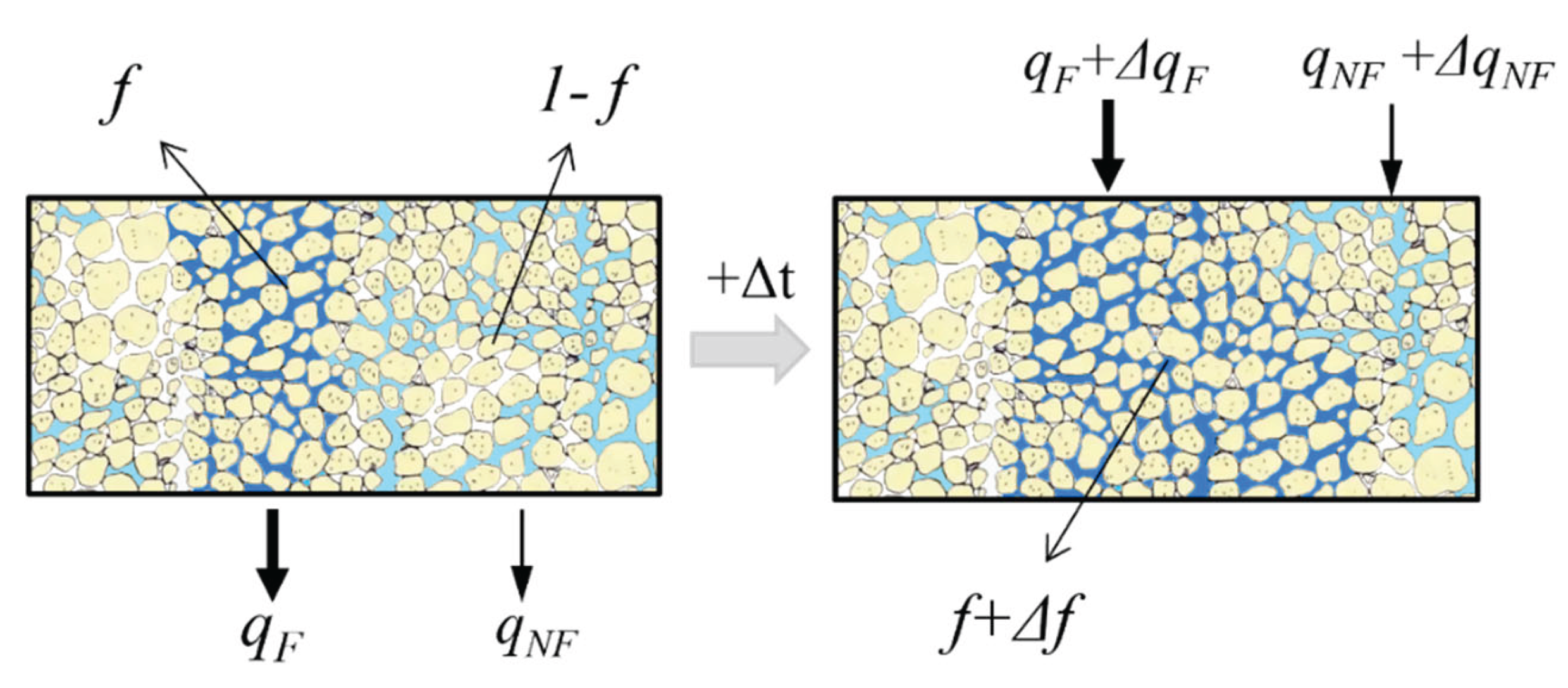

3. A Model Generalization to the Dual-Flow Field

All the above discussions on modeling gravitational fingering flow in unsaturated soils with the optimality-based ARM assume that water is immobile within the non-fingering zone. In some field-scale contexts it does carry a small flux, albeit much slower than in the fingers. In a more general case, two flow fields coexist (

Figure 2): the non-fingering zone with a relatively small water flux, governed by the Darcy-Buckingham law, and the fingering flow zone with a large water flux, described by the current theory based on the optimality [

11]. This section develops a theoretical framework to capture both flows. Because vadose flow is predominantly vertical, we restrict attention to one-dimensional vertical flow.

Since soil water is considered incompressible under isothermal conditions, soil-water mass balance is reduced to its volume balance. The total soil-water volume balance equation is

where subscripts

F and

NF refer to fingering flow and non-fingering zones, respectively,

is water content,

t is time,

z is again vertical coordinate with positive direction being downward, and

q is the water flux defined here as the volumetric water flow rate divided by cross-sectional area of bulk soil including both fingering and non-fingering zones. Water fluxes corresponding to the two zones are, respectively, given by

and

where

E is soil water energy (or hydraulic head), and the fraction of fingering flow zone is determined by

When there is no water flux in the non-fingering zone,

is the same as the total water flux, and Equation (29) becomes identical to Equation (23). Also, note that

and

have the same relationship with local-scale water saturation. For example, if they are described by the van Genuchten [

23] equation, they have the same values for the parameters in the equation because soils under consideration are homogeneous. However, at a given time, values for relative permeability

and

correspond to local-scale water saturations in fingering and non-fingering zones, respectively. Since the water saturation in the fingering flow zone is higher than that in the non-fingering zone,

is larger than

. Following the same line,

is also different from

. Clearly, these differences are reflection of the fact that fingering flow is inherently a nonequilibrium process.

Equation (26) describes the total soil-water volume balance involving both non-fingering and fingering zones. The following equation describes the volume balance specifically for the fingering flow zone:

The second term on the left-hand side of the above equation is related to the interaction between fingering flow zone and non-fingering zone (

Figure 2). It results from the expansion (or shrinkage) of fingering flow zone to (or from) the non-fingering zone with original water content

. The water volume associated with the original water content in the expanded domain is not directly from the fingering flow associated with

and thus should be subtracted from the total volume in the fingering flow zone after the expansion in Equation (30).

Similarly, the volume balance equation for the non-fingering zone is given as follows:

Again, the second term on the left-hand side of the above equation is a result of the interaction between fingering flow zone and non-fingering zone. Equation (31) can be obtained by subtracting Equation (30) from Equation (26) and thus only two of these three volume balance equations (Equations (26), (30) and (31)) are independent.

To apply the generalized model for the dual-flow fields to soil water flow in homogeneous unsaturated soils, one needs to solve two of the three volume balance equations above, together with Equations (27), (28) and (29), under appropriate boundary and initial conditions. While the focus here is on the theoretical framework for the dual-flow field, we will leave to future studies the development of numerical algorithms for the generalized model and validations with experimental data.