1. Introduction

Pain represents a grave global public health challenge, severely threatening human well-being. Chronic pain afflicts 37% of the population in developed nations and 41% in developing ones, with over half of sufferers experience emotional comorbidities, particularly anxiety, are prevalent, creating a vicious cycle that severely undermines patients’ physical and mental quality of life [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. A deeper understanding of the neural mechanisms driving this comorbidity is crucial to uncovering novel therapeutic directions for chronic pain. Previous research has demonstrated that the majority of C-afferents are polymodal nociceptors actively involved in pain transmission. Furthermore, ablation of mas-related G-protein-coupled receptor D neurons reduces behavioral sensitivity to noxious mechanical stimuli in mice [

6,

7,

8]. After knocking out the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1) channel, mechanical hyperalgesia in arthritis model mice is alleviated [

9]. Meanwhile, electroacupuncture (EA) alleviates pain in Complete Freund’s Adjuvant (CFA) model mice specifically through the TRPV1 signaling pathway in the brain [

10,

11]. Our previous research has revealed that mas-related G-protein-coupled receptor b4 (Mrgprb4)-lineage neurons, which specifically innervate hairy skin and belong to the C-fiber population, are a polymodal group indispensable for transmitting pleasant sensations [

12,

13]. Furthermore, Mrgprb4-lineage neurons are required for dopamine release during sexual behavior in female mice and are involved in brain reward [

14]. More interestingly, ablation of Mrgprb4-lineage neurons did not alter the pain threshold or motor function, much less lead to noxious pain behaviors [

14].

In current clinical practice, a combination therapy of analgesics and anti-anxiety/depression drugs is widely adopted for managing chronic pain comorbid with anxiety [

15]. While this regimen can mitigate patients’ pain and associated negative emotions to some degree, its efficacy remains dose-dependent and is accompanied by notable adverse reactions, including gastrointestinal and hepatorenal function impairments, as well as drug dependence [

16]. Consequently, there is an urgent need to develop safer, more effective therapeutic strategies for the comorbidity of chronic pain and anxiety and to further elucidate the underlying therapeutic targets. The analgesic effect of transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) is well-established, demonstrating significant efficacy in relieving diverse chronic pain conditions such as inflammatory pain, low back pain, postoperative incisional pain, and fibromyalgia [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. It produces acupuncture-like effects with distinct advantages and minimal obvious adverse reactions. Furthermore, as an emerging physical therapy modality, TENS has demonstrated unique potential for intervening in anxiety and depression [

23]. Previously published studies have established its efficacy in treating anxiety disorders during and after surgery [

24,

25,

26], however, evidence supporting TENS’s anti-anxiety effects from basic research remains limited [

26]. Zusanli (ST36) is a prominently selected point for managing pain syndromes and emotional disorders. Two research demonstrate that TENS or EA applied at ST36 significantly reduces postoperative opioid analgesic requirements and elevates TRPV1 expression levels to attenuate pain and depression [

11,

27]. Mrgprb4-lineage neurons transmit pleasant sensations induced by mild pressure and could represent key peripheral polymodal receptors enabling TENS function [

12]. Whether the mechanism underlying TENS alleviation of anxiety-like behaviors accompanying chronic pain involves Mrgprb4-lineage neurons remains unknown.

Employing genetically engineered mouse models alongside genetic manipulation, viral strategies, and behavioral assessments, we selectively activated or ablated Mrgprb4-lineage neurons to determine whether these neurons mediate the regulation of chronic pain and anxiety comorbidity by TENS applied at ST36. This study’s findings will provide novel insights and valuable references for therapeutic targets addressing this comorbidity and further enhance clinical outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animals

All animal experiments strictly adhered to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The Animal Ethics Committee at the Institute of Acupuncture and Moxibustion, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, rigorously reviewed and formally approved all experimental protocols.

We conducted experiments using C57BL/6J mice (obtained from SPF Biotechnology Co. Ltd., License No: SCXK- [Jing]-2019-0010). Mrgprb4Cre-tdTomato transgenic strains were generated by Shanghai Model Organisms Center, Inc.). Mouse lines of Ai96 (RCL-GCaMP6s mice) (no.028866) and Ai32(RCL-ChR2/EYFP mice) (no. 024109) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Subjects included both male and female mice aged 8 weeks; gender exerted no significant influence on the experimental outcomes.

Housed within standard animal facilities, mice were given ad libitum access to food and water. They experienced a consistent 12-hour light-dark cycle (dark phase: 8:00 pm to 8:00 am), with ambient temperature maintained at 23°C ± 0.5°C, humidity controlled between 60% and 70%, and environmental noise kept below 60 dB. All animals acclimated to these conditions for seven full days prior to experimentation. Crucially, all experiments were performed by experimenters rigorously blinded to the specific genotype of the mice.

A mouse model of chronic pain and anxiety comorbidity (designated CFA mice) was successfully established via subcutaneous administration of Complete Freund’s Adjuvant (CFA) into the hind paw. Under isoflurane inhalation anesthesia, precisely 25 μL of CFA was meticulously injected subcutaneously into the right hind paw of each mouse. The needle penetrated approximately 0.5 cm deep, and the injection process deliberately spanned over 30 seconds. Upon needle withdrawal, the injection site was promptly compressed with a sterile cotton ball to prevent solution leakage. Following CFA injection, the hind paw exhibited marked redness and swelling, accompanied by distinct behavioral manifestations like persistent foot shaking, vigorous licking, and pronounced lameness; concurrently, the mechanical pain threshold showed a significant reduction. Control mice received an equal volume (25 μl) of sterile 0.9% saline injected into the right hind paw using an identical protocol. After thorough disinfection with iodophor, all mice were carefully returned to their home cages for attentive post-procedural care.

2.2. Intrathecal Injection

Mrgprb4-Cre;GCaMP6s mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal administration of 1.25% tribromoethanol (0.2 mL/10 g body weight; Aibei Biotechnology, Nanjing, China). Core body temperature was maintained at approximately 37 °C using a heating pad. A 1 cm skin incision was made over the lumbar region to expose the T11-T12 intervertebral space. Under stereomicroscopic guidance (OLYMPUS SZ51, Tokyo, Japan), the intervertebral membrane and underlying dura mater were carefully exposed using fine forceps. A 0.2 mm diameter catheter connected to a microinjection system was stereotaxically inserted 5 mm caudally into the T11-T12 intervertebral space. Subsequently, 5 μL of either AAV9 (rAAV-CMV-DIO-taCasp3-T2A-TEVp; BrainCase Inc., BC-0128, 1.1×1013 GC/mL) or sterile 0.9% saline was infused into the intrathecal space at a constant rate of 1.2 μL/min. The surgical incision was closed 10 minutes post-injection. Animals were monitored during postoperative recovery. Behavioral assessments were conducted ≥3 weeks following intrathecal injection.

2.3. Measurement of Hind Paw Thickness

Hind paw thickness measurements were obtained using a digital caliper. To prevent stress responses from compromising experimental outcomes, paw thickness was assessed while mice were carefully maintained under 0.5-1% isoflurane anesthesia (R510-22-10, RWD). The mouse’s hind paw was gently positioned horizontally. The operator then precisely aligned the caliper jaws with the peak swelling point on the dorsum of the foot and recorded the measurement.

2.4. Mechanical Pain Threshold Detection

The mechanical threshold was assessed using sequentially ascending calibrated von Frey filaments (0.008 g, 0.02 g, 0.04 g, 0.07 g, 0.16 g, 0.4 g, 0.6 g, 1.0 g, 1.4 g; (Touch Test

® Sensory Evaluators, Shanghai RuiShi), commencing with the 0.008 g filament. Filaments were applied perpendicularly to the skin with sufficient force to produce slight bending, only during periods of mouse stillness. Positive responses were defined as paw withdrawal, paw licking, or escape behavior. Each filament underwent five consecutive applications; the minimal filament eliciting reflexive paw withdrawal on at least three of five trials was designated the paw withdrawal threshold, consistent with established methodology [

28].

2.5. Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation Applications

The ST36 point was identified using an experimental acupuncture atlas [

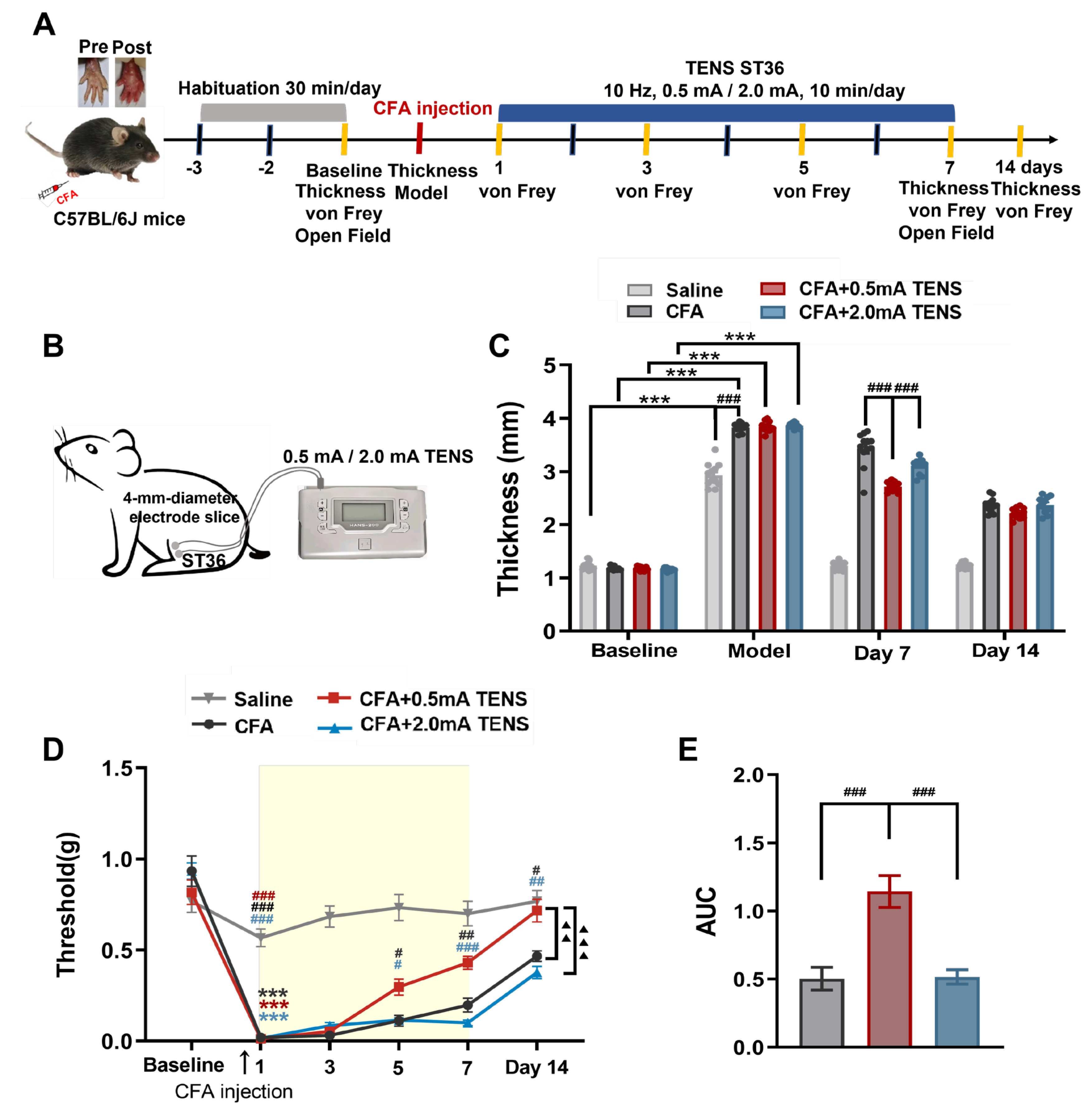

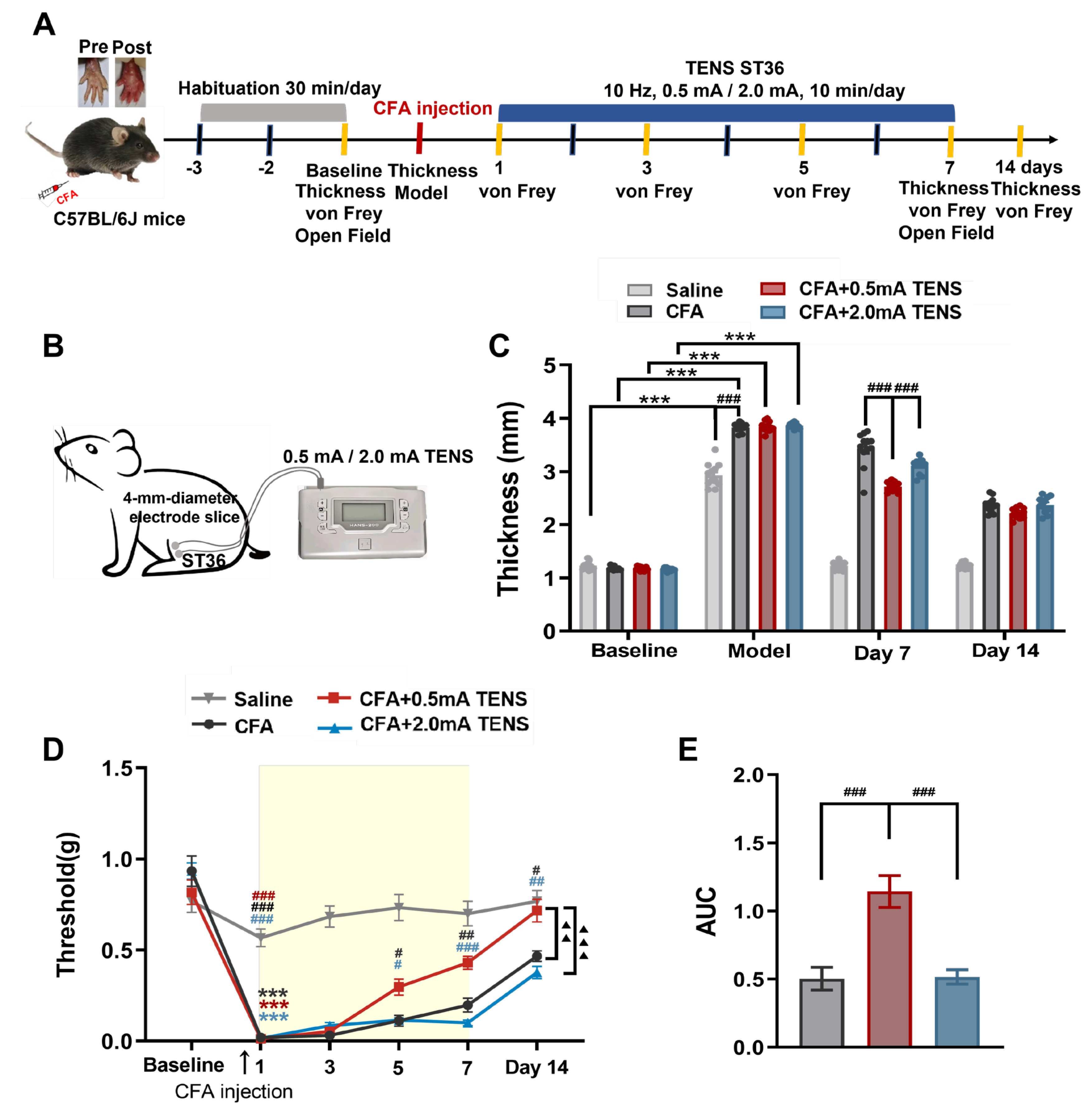

29]. Located at the posterolateral aspect of the knee joint, approximately 5 mm below the fibular head, ST36 served as the target site. Mice received induction anesthesia with 2% isoflurane, followed by maintenance at 1% concentration. Positioned supine on the operating table, each mouse had a 4-mm diameter silver wire electrode secured over the right ST36 point. TENS intervention commenced on the first post-modeling day. The electrode, connected to a HANS-200A electroacupuncture instrument, delivered TENS as depicted in

Figure 1B. A sufficient quantity of conductive paste coated the electrode slice surface to ensure optimal conductivity. Stimulation parameters were: 10 Hz frequency, 0.5 mA / 2.0 mA intensity, administered for 10 minutes per session, once daily, over 7 consecutive days.

2.6. Open Field Test

Animals were acclimated to both their testing environment and equipment before behavioral assessments commenced. Throughout testing, the experimenter remained blind to each animal’s genotype until after behavioral analysis concluded. Stress and anxiety-like behaviors were quantified using an open-field apparatus (L40 × W40 × H30 cm) [

28]. Following a 10-minute adaptation period within the experimental room, each mouse was gently placed in the center of the open-field arena. The apparatus floor was divided into 16 equal squares, designating the middle four squares as the center zone. A digital video camera recorded each animal’s movements for 5 minutes, specifically tracking the total distance traveled and time spent within the center zone. The mice’s motion trails were subsequently analyzed using Any-maze software (version 7, Stoelting).

2.7. In Vivo Ca2+ Imaging of L4 DRG

As previously described [

12], endotracheal intubation and exposure of the L4 DRG were performed (

Figure S1A-C). Intracellular calcium concentration shifts were captured using a laser-scanning confocal microscope (Leica Stellaris 8, Germany), with changes visualized through fluctuating fluorescein intensity within the neurons. Before imaging, mice were secured prone on a custom-designed microscope stage. The spinal column was firmly stabilized using a pair of customized spinal clamps to eliminate movement artifacts (

Figure S1D) and guarantee the L4 DRG remained fully exposed, free from blood exudation obscuring the field, consistent with prior methodology [

30,

31,

32]. During imaging sessions, adult male or female Mrgprb4

Cre; GCaMP6s mice received anesthesia via tracheal intubation (0.5-1% isoflurane, R510-22-10, RWD) following L4 DRG exposure. Supplemental 0.5% isoflurane was administered intratracheally when necessary to prevent muscle twitching during recording if anesthesia was proved insufficient. Ointment was applied to the animals’ eyes to prevent drying.

Imaging was conducted using a Leica 10× air objective at 1× magnification. Following localization of the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) field under microscopy (

Figure S1E), L4 DRG thickness was determined along the Z-axis, with subsequent adjustment of X and Y planes to ensure complete inclusion of the L4 DRG within the imaging field. Time-lapse z-stacks of intact DRG were acquired at 512 × 512 resolution. Individual frames comprised 6–12 z-stacks (contingent upon DRG-to-objective lens alignment), with 9 frames captured for mechanical stimuli and 20 frames for thermal stimuli. A 488 nm excitation wavelength was employed at 5% laser power, with bidirectional image acquisition at 400 Hz scan speed. Neuronal activation triggers GCaMP binding to intracellular Ca

2+, yielding green fluorescence for imaging (

Figure S1F). Live imaging spanned 9 consecutive frames: frames 1–3 recorded baseline fluorescence intensity (pre-stimulation), frames 4–6 documented stimulation-phase intensity, and frames 7–9 captured post-stimulation recovery.

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) was then administered at randomized intensities (0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0 mA; 10 Hz, 1 ms pulse width) at ST36, with 1–2 minute interstimulus intervals. Core body temperature was maintained at 37.0 ± 0.5 °C via heating pad with rectal thermometry (DC Temperature Controller, FSH, USA), while respiratory parameters underwent real-time monitoring (Small animal anesthesia system, SomnoSuite, Kent Scientific).

2.8. Optogenetics

The hair in the right ST36 area of the mice was removed in advance. Under maintained isoflurane inhalation anesthesia, the right ST36 area was subjected to blue light stimulus. The optical fiber was positioned 5 - 7 mm above the skin surface. Parameters: 473 nm, 10 Hz, 30 mW, 1 ms, 10 min per time, once a day, for 7 consecutive days. The body temperature of the mice was maintained at 37.0 ± 0.5 °C with a heating pad.

2.9. Immunofluorescence

Animals were deeply anesthetized with a Tribromoethanol solution, and the blood was cleared from all tissues by perfusing saline through the vascular system. Mice were then perfusion - fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Tissues were then collected and post - fixed in 4% PFA accordingly (DRG: 2 h, skin: 2 - 3 h). All tissues were cryoprotected in 30% sucrose for a minimum of 48 h. Subsequently, the tissues were embedded and sectioned on a freezing microtome (LEICA CM 1950, Germany) (DRG: 20 μm, skin: 30 μm). Sections were washed in PBS (3×10 minutes) and then blocked in PBS containing 3% goat serum and 0.5% Triton X - 100 for 1 hour at room temperature. Chicken anti - GFP (1:500, Abcam, #ab13970) was used as the primary antibody. Anti - GFP antibodies were used to label the expression of GCaMP6s in Mrgprb4 - GCaMP6s mice or ChR2 in Mrgprb4 - ChR2 mice. The secondary antibody was goat anti - chicken IgG - Alexa - Fluor 488 (1:600, Invitrogen, A11039). DAPI - containing media (ZLI - 9600, ZSGB - BIO) or glycerin was used to coverslip the tissue. The DRG sections were imaged with full - spectral scanning for confocal microscopy (OLYMPUS FV1200, Tokyo, Japan).

2.10. Quantification of Calcium Imaging

Calcium imaging data analysis was performed by Image J (National Institutes of Health). After importing the collected raw data into Image J, the activated neurons were manually circled and the relative fluorescence intensity of the neurons was exported. The calcium signal transients are expressed as Δ F / F0 = (Ft-F0) / F0. Ft represented the maximum fluorescence intensity of cells during stimulation (4-6 frames) and F0 represented the maximum fluorescence intensity of cells at baseline (1-3 frames) before intervention. Activation in neurons was defined as an increase in Δ F / F0 ≥ 30% [

30]. Calcium imaging data processors were mutually blinded to the experimental operator to reduce selection and bias.

2.11. Statistical Analysis

All data were presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M). Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA). Figures were prepared with bioRender (

https://BioRender.com), GraphPad Prism 8.0. Two-tailed unpaired or paired t tests were used to compare the two groups. Multiple groups were compared using one-way ANOVA or two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc tests. Data that did not conform to a normal distribution were analyzed using non-parametric tests. The number of mice and the statistical tests used for individual experiments were included in the Fig. legends. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all tests.

4. Discussion

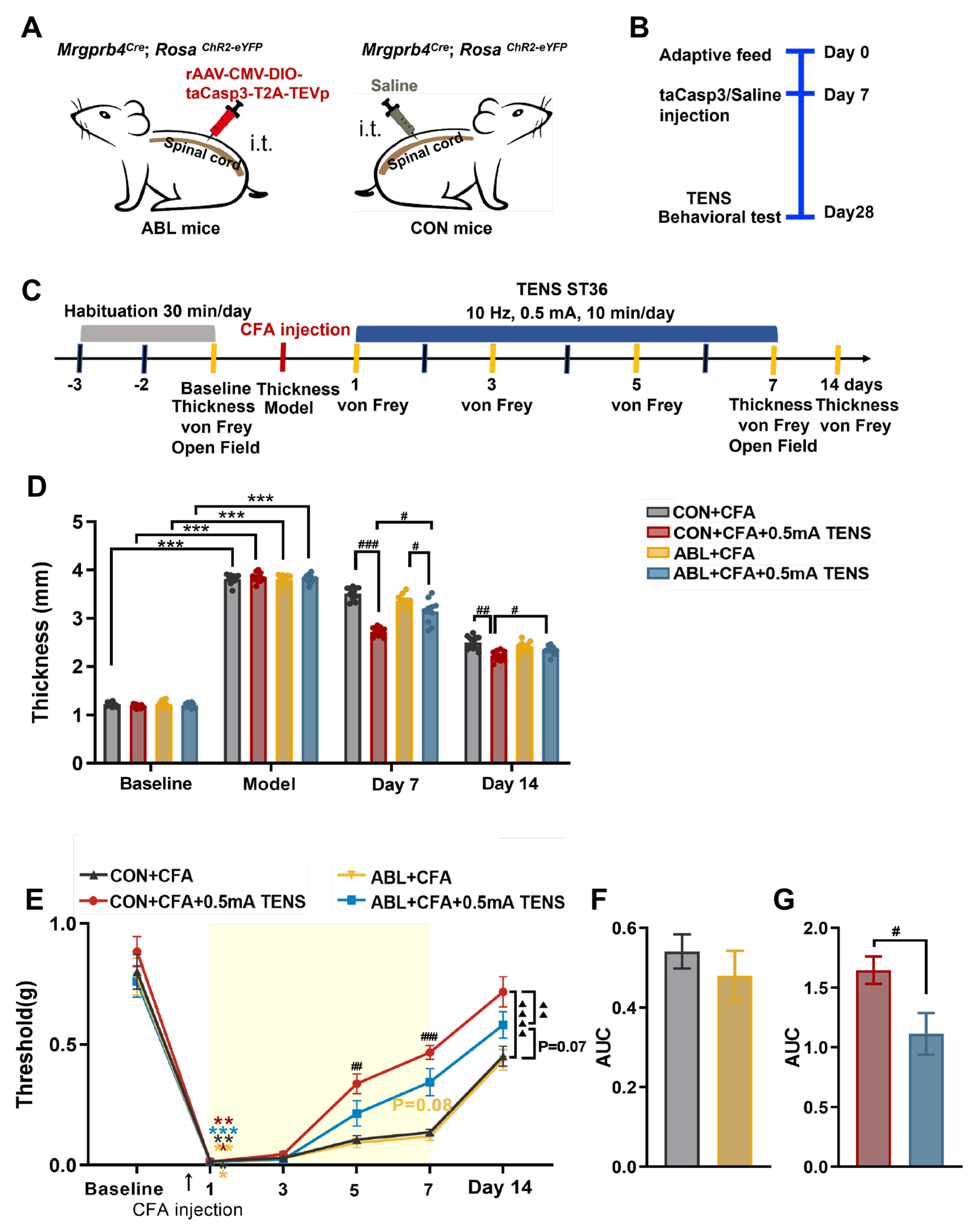

This study employed transgenic mice and a CFA-induced model of chronic pain and anxiety comorbidity. Utilizing in vivo Ca2+ imaging, genetic manipulation, viral strategies, and behavioral assessments, our research demonstrated that 0.5 mA TENS applied to ST36 significantly ameliorated both pain and anxiety-like behaviors in the comorbidity model. Simultaneously, in vivo Ca2+ imaging confirmed a substantial proportion of Mrgprb4-lineage neurons were activated by this specific TENS intensity. Photostimulation targeting ST36 replicated these analgesic and anxiolytic effects by selectively activating Mrgprb4-lineage neurons. Conversely, viral ablation of these neurons markedly attenuated the analgesic benefits of 0.5 mA TENS and failed to alleviate anxiety-like behaviors. Collectively, these findings indicate that the therapeutic regulation of chronic pain and anxiety comorbidity by 0.5 mA TENS critically requires the functional involvement of Mrgprb4-lineage neurons.

TENS is a non-invasive therapy applied to the skin surface, delivering appropriate intensity and frequency electrical currents through electrodes attached to the patient’s skin. This stimulates the nervous system to produce therapeutic effects [

33,

34]. TENS produces acupuncture-like effects, sharing similar underlying mechanisms with acupuncture. While TENS activates Aβ, Aδ, and C fibers, the specific fiber types engaged depend critically on the stimulation frequency and intensity [

35,

36,

37,

38]. Research demonstrates that low-frequency TENS primarily activates C fibers [

37], whereas high-frequency TENS (90-130 Hz) mainly stimulates Aβ fibers [

38]. Han Qingjian et al. confirmed that high-frequency (100 Hz) TENS selectively activates Aβ fibers [

39]. TENS demonstrates remarkable efficacy in alleviating chronic pain conditions like inflammatory pain, low back pain, postoperative incisional pain, and fibromyalgia, without significant adverse effects even during long-term use [

17,

18,

20,

21,

22]. Pain relief often occurs immediately following TENS treatment, with the analgesic effect persisting for several hours [

40]. Notably, low-frequency (10 Hz) TENS exhibits a markedly more prolonged analgesic effect compared to high-frequency (130 Hz) TENS [

19]. Furthermore, 0.5 mA EA demonstrates superior efficacy in alleviating inflammatory edema and hyperalgesia [

41]. Additionally, early research has confirmed the effectiveness of TENS in treating anxiety disorders during and after surgery [

24,

25,

26]. The ST36 acupoint is commonly used for treating pain and anxiety disorders. TENS stimulation at the ST36 acupoint can significantly alleviate postoperative opioid analgesic requirement and opioid-related side effects [

27,

42]. Therefore, TENS holds significant clinical application potential and value in the treatment of chronic pain comorbid with anxiety.

The CFA-induced inflammatory pain model is the most commonly used animal model for studying comorbidity of chronic pain and anxiety [

43,

44]. This model can induce persistent mechanical pain sensitivity behavior by subcutaneous injection of CFA into the hind paw of mice [

45]. Studies have shown that mice injected with CFA exhibited anxiety-like behaviors on the 7th day, primarily manifested as a notable reduction in the time spent in the central area during an open-field test [

46].

The analgesic effects of TENS may be mediated through the gate-control theory or the endogenous analgesic system. According to the classical gate-control theory, the excitation of large-diameter afferent fibers (thick fibers) prompts substantia gelatinosa cells in the spinal dorsal horn to release inhibitory neurotransmitters. These neurotransmitters, through presynaptic inhibition of T cells, close the “gate” and thereby exert an analgesic effect. Conversely, the excitation of small-diameter afferent fibers (thin fibers) relieves the inhibition on T cells, opening the “gate” and eliciting pain [

47]. TENS, developed under the guidance of this theory, is generally believed to produce its segmental analgesic effect by activating thick fibers, which in turn inhibit the transmission of nociceptive information mediated by thin fibers, leading to the closure of the “gate” [

38] . However, with the deepening of understanding and technological innovations in the field of neuroscience, the mechanisms of pain modulation in the spinal cord are far more complex than what the traditional gate-control theory describes. Lu and Perl et al. discovered a specific pathway where low-threshold C-fibers regulate the input of nociceptive C-fibers through inhibitory interneurons, demonstrating that C-fibers can also close the pain “gate” [

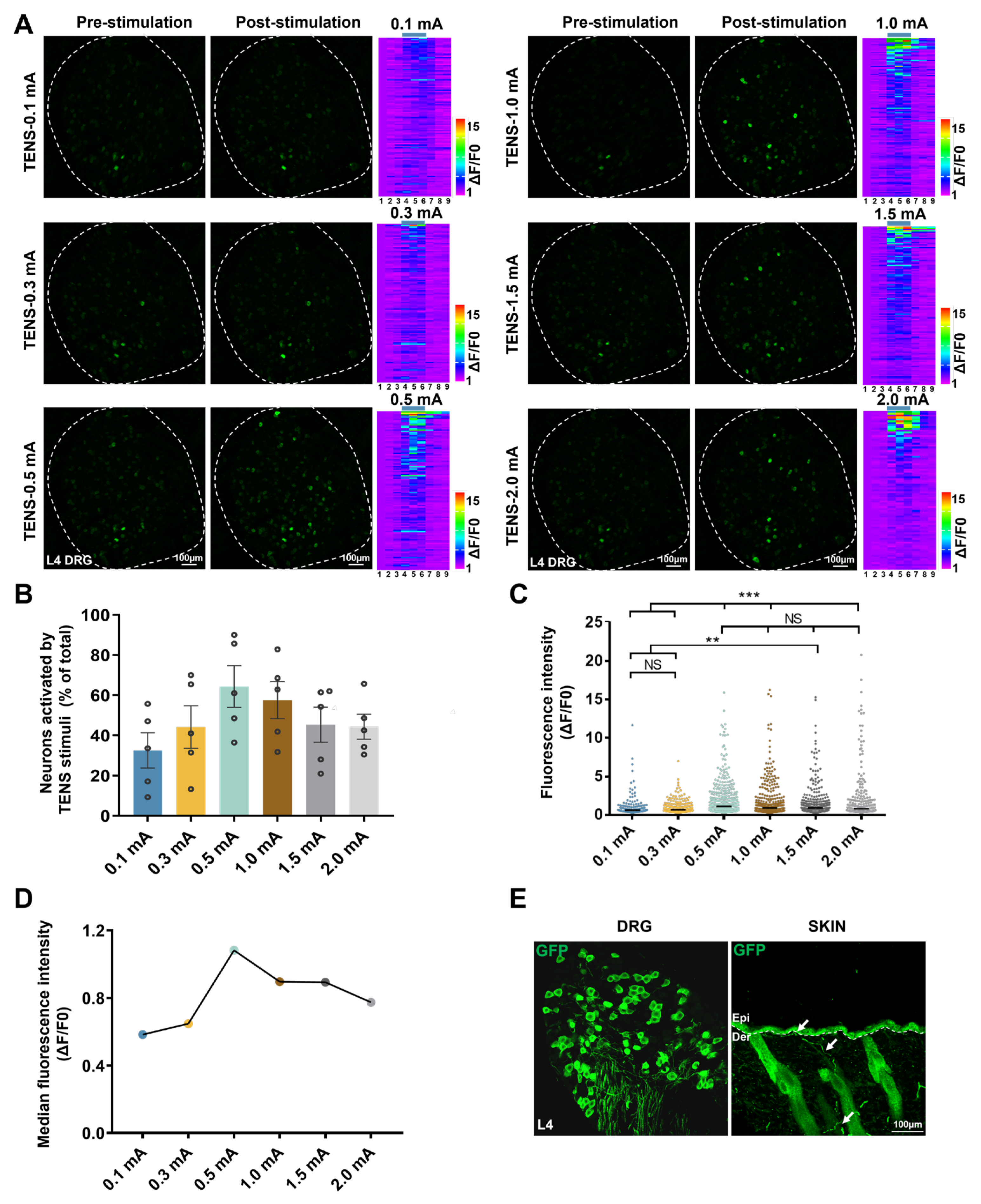

48] . In our study, utilizing in vivo Ca

2+ imaging, we have demonstrated that Mrgprb4-lineage neurons are polymodal, encompassing both C-low-threshold mechanoreceptors and C-high-threshold mechanoreceptors [

12]. Intriguingly, as

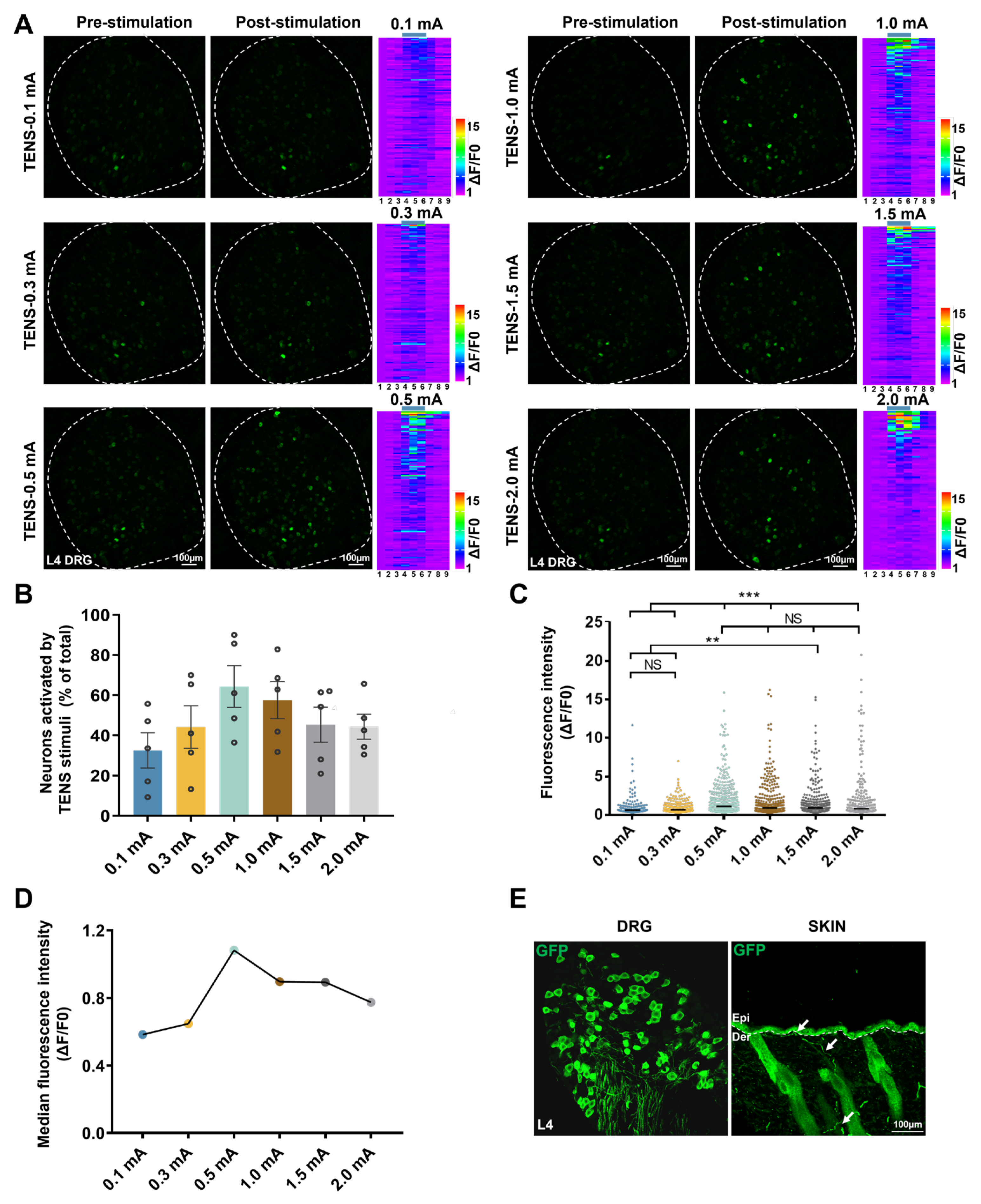

Figure 3 reveals, Mrgprb4-lineage neurons specifically innervating the hairy skin are activated by TENS, with 0.5 mA emerging as the optimal stimulation intensity. Therefore, applying 0.5 mA TENS stimulation at the ST36 acupoint can effectively close the pain “gate” mechanism by activating Mrgprb4-lineage specific fiber terminals in the skin, thus generating a potent analgesic effect.

In addition, the analgesic effects of TENS may stem from activation of the endogenous analgesic system. TENS can stimulate the release of endogenous analgesic substances within the central nervous system, such as opioid peptides and 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) [

42,

49,

50]. Studies demonstrate that low-frequency TENS enhances the release of enkephalins and endorphins, effectively alleviating pain [

49]. Furthermore, low-frequency TENS elevates 5-HT content in the spinal cord of arthritis model animals, reducing inflammation-induced mechanical hyperalgesia [

50]. Low-frequency TENS effectively combats hyperalgesia by curbing the release of glutamate and substance P within the spinal dorsal horn [

51,

52,

53,

54]. Furthermore, the TENS protocol employed in this experiment utilized repeated stimulation; continuous application over 7 days yielded significant and remarkably long-lasting analgesic effects [

55,

56].

Dopamine (DA) plays a crucial regulatory role in reward processing, modulation of pain perception, and the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying affective disorders [

57]. Reduced synthesis or dysfunction of DA can lead to anxiety-like behaviors [

57]. Studies have demonstrated the presence of synaptic connections between Mrgprb4-lineage neurons and spinoparabrachial (SPB) neurons that express G protein-coupled receptor 83 (Gpr83) [

14,

58] . Abdus-Saboor I et al. found that blue light activation of Mrgprb4 lineage neurons conveys sensory information through Gpr83+ SPB to the parabrachial nucleus and ultimately reaches the nucleus accumbens, triggering DA release and inducing lordosis-like posture in female mice to facilitate mounting by male mice [

14] . Inactivation of Mrgprb4-lineage neurons, however, converts mating behavior into aggressive behavior and is associated with decreased DA release. Additionally, chemogenetic activation of Mrgprb4 neurons induces conditioned place preference in mice, indicating that such activation has positive reinforcing or anti-anxiety effects [

59,

60]. Notably, activated Mrgprb4-lineage neurons are integral to the brain’s reward circuitry. Consequently, applying 0.5 mA TENS at ST36 effectively alleviates anxiety-like behaviors induced by CFA injection through the activation of Mrgprb4-lineage neurons, thereby inducing dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens. Our findings reveal that ablating Mrgprb4-lineage neurons diminishes TENS’s anti-anxiety effects, demonstrating that these neurons play a crucial role in mediating TENS’s therapeutic action against anxiety.

Figure 1.

Effects of TENS ST36 on hind paw thickness and mechanical pain threshold in CFA mice. A Timeline of the CFA injection, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), and behavioral testing to study the analgesic and anxiolytic effects of TENS (10Hz, 0.5 mA / 2.0 mA) treatment in CFA mice. B Schematic of TENS at the ST36 sites. C Time course of TENS on hind paw thickness of CFA mice (N=12). D Time course of TENS on mechanical pain thresholds of CFA mice (N=12). Yellow shadow is used to TENS stimuli. E The AUC statistics of each group. All data are shown as mean ± S.E.M. C–D by two-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. Statistical symbols in different colors are represented to denote different groups. Compared with Baseline, ***p < 0.001; Compared between groups at each time point, #p < 0.05,##p < 0.01,###p < 0.001; Compared with CFA+0.5 mA TENS group, ▲▲p < 0.01,▲▲▲▲p < 0.0001. (E) by one-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test, ##p < 0.01.

Figure 1.

Effects of TENS ST36 on hind paw thickness and mechanical pain threshold in CFA mice. A Timeline of the CFA injection, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), and behavioral testing to study the analgesic and anxiolytic effects of TENS (10Hz, 0.5 mA / 2.0 mA) treatment in CFA mice. B Schematic of TENS at the ST36 sites. C Time course of TENS on hind paw thickness of CFA mice (N=12). D Time course of TENS on mechanical pain thresholds of CFA mice (N=12). Yellow shadow is used to TENS stimuli. E The AUC statistics of each group. All data are shown as mean ± S.E.M. C–D by two-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. Statistical symbols in different colors are represented to denote different groups. Compared with Baseline, ***p < 0.001; Compared between groups at each time point, #p < 0.05,##p < 0.01,###p < 0.001; Compared with CFA+0.5 mA TENS group, ▲▲p < 0.01,▲▲▲▲p < 0.0001. (E) by one-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test, ##p < 0.01.

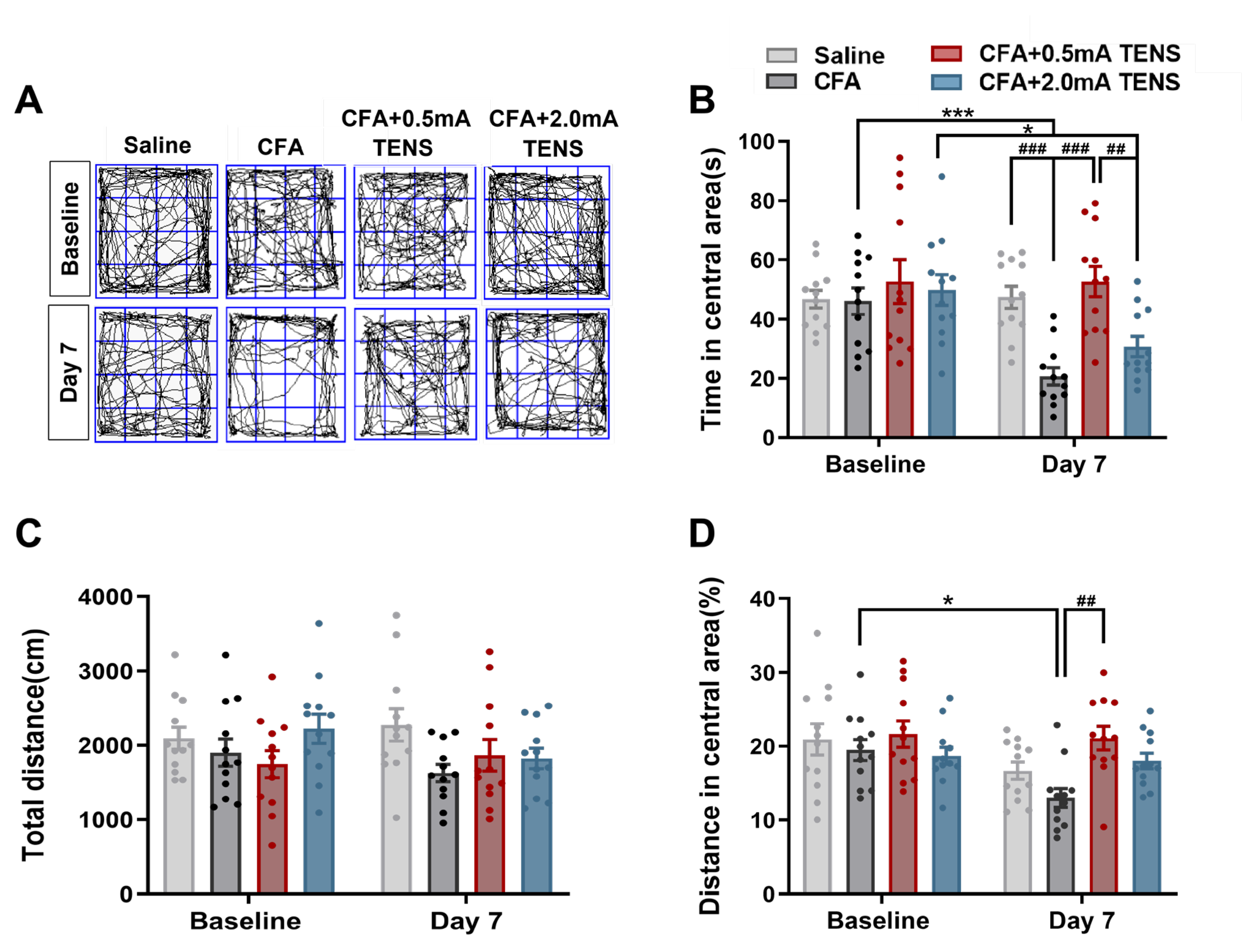

Figure 2.

Effects of TENS ST36 on anxiety-like behaviors in CFA mice. A Representative animal tracks of the four groups in the open filed test. B The time in central area of mice in each group (N=12). C The total distance of mice in each group (N=12). D The proportion of the central area to the total distance in each group of mice (N=12). All data are shown as mean ± S.E.M. B–D by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. Compared within each group, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001; Comparisons across all groups, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001.

Figure 2.

Effects of TENS ST36 on anxiety-like behaviors in CFA mice. A Representative animal tracks of the four groups in the open filed test. B The time in central area of mice in each group (N=12). C The total distance of mice in each group (N=12). D The proportion of the central area to the total distance in each group of mice (N=12). All data are shown as mean ± S.E.M. B–D by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. Compared within each group, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001; Comparisons across all groups, ##p < 0.01, ###p < 0.001.

Figure 3.

Responses of L4 DRG Mrgprb4-lineage neurons to diverse TENS stimulation in vivo Ca2+ imaging. A Representative images of Mrgprb4-lineage neuronal calcium transients to TENS stimuli (0.1 mA, 0.3 mA, 0.5 mA, 1.0 mA, 1.5 mA, and 2.0 mA) observed during in vivo Ca2+ imaging of one L4 DRG (the white outline indicates the DRG border). Right: Heatmaps of calcium signals in a single mouse DRG under diverse TENS stimuli (total recorded cells = 200). The numbers of Mrgprb4-lineage neurons activated by TENS stimulation of 0.1 mA, 0.3 mA, 0.5 mA, 1.0 mA, 1.5 mA, and 2.0 mA were 94, 82, 122, 137, 124, and 85, respectively. Scale bar, 100 μm. B The proportion of Mrgprb4-lineage neurons activated by TENS stimulation at varying intensities. Each pair of open circles represents an individual mouse. N= 5 mice. C Quantification of Ca2+ responses in cells responding to diverse TENS stimuli. Violin plots show median (black lines) and data distributions. N= 5 mice (total recorded cells = 622). D Median fluorescence intensity of Mrgprb4-lineage neurons in response to TENS stimulation at varying intensities. E Representative images of GFP+ cells in the Mrgprb4Cre; RosaChR2-EYFP mice. Immunohistochemistry was performed on L4 DRG and skin from Mrgprb4Cre; RosaChR2-EYFP mice. White arrows indicate examples of GFP+ cells. Dashed lines indicate the boundary between the epidermis and dermis layers. Scale bar, 100µm. All data are shown as mean ± S.E.M. B–C by one-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Figure 3.

Responses of L4 DRG Mrgprb4-lineage neurons to diverse TENS stimulation in vivo Ca2+ imaging. A Representative images of Mrgprb4-lineage neuronal calcium transients to TENS stimuli (0.1 mA, 0.3 mA, 0.5 mA, 1.0 mA, 1.5 mA, and 2.0 mA) observed during in vivo Ca2+ imaging of one L4 DRG (the white outline indicates the DRG border). Right: Heatmaps of calcium signals in a single mouse DRG under diverse TENS stimuli (total recorded cells = 200). The numbers of Mrgprb4-lineage neurons activated by TENS stimulation of 0.1 mA, 0.3 mA, 0.5 mA, 1.0 mA, 1.5 mA, and 2.0 mA were 94, 82, 122, 137, 124, and 85, respectively. Scale bar, 100 μm. B The proportion of Mrgprb4-lineage neurons activated by TENS stimulation at varying intensities. Each pair of open circles represents an individual mouse. N= 5 mice. C Quantification of Ca2+ responses in cells responding to diverse TENS stimuli. Violin plots show median (black lines) and data distributions. N= 5 mice (total recorded cells = 622). D Median fluorescence intensity of Mrgprb4-lineage neurons in response to TENS stimulation at varying intensities. E Representative images of GFP+ cells in the Mrgprb4Cre; RosaChR2-EYFP mice. Immunohistochemistry was performed on L4 DRG and skin from Mrgprb4Cre; RosaChR2-EYFP mice. White arrows indicate examples of GFP+ cells. Dashed lines indicate the boundary between the epidermis and dermis layers. Scale bar, 100µm. All data are shown as mean ± S.E.M. B–C by one-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

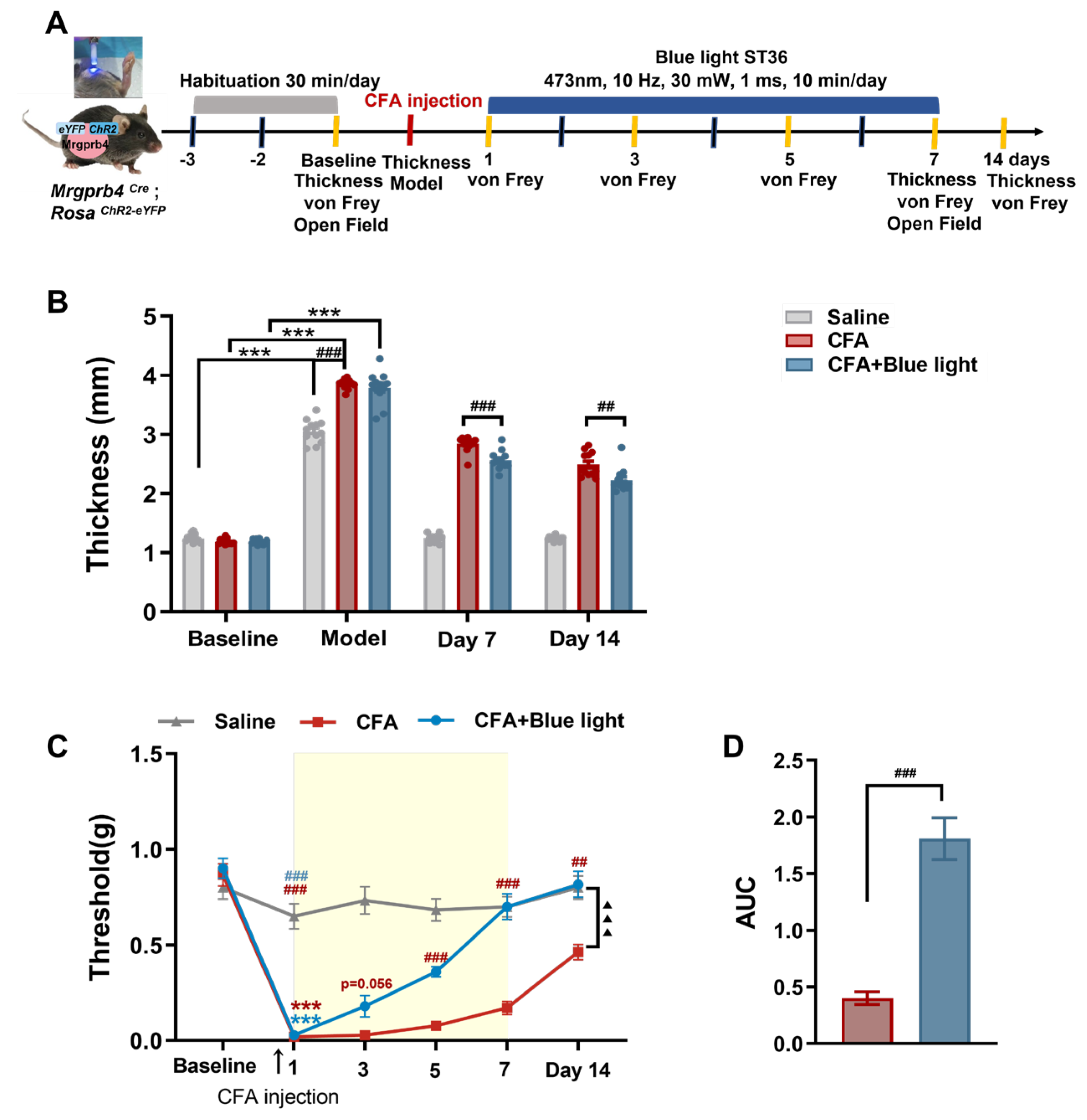

Figure 4.

Effects of Mrgprb4-lineage neurons activated by Blue light on hind paw thickness and mechanical pain threshold of CFA mice. A Timeline of the CFA injection, TENS, and behavioral testing to study the analgesic and anxiolytic effects of TENS (10Hz, 0.5 mA / 2.0 mA) treatment in CFA mice. B Time course of TENS on hind paw thickness of CFA mice (N=12). C Time course of TENS on mechanical pain thresholds of CFA mice (N=12). Yellow shadow is used to TENS stimuli. D The AUC statistics of each group. All data are shown as mean ± S.E.M. C–D by two-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. Statistical symbols in different colors are represented to denote different groups. Compared with Baseline, ***p < 0.001; Compared between groups at each time point, #p < 0.05,##p < 0.01,###P < 0.001; Compared with CFA+0.5 mA TENS group, ▲▲p < 0.01,▲▲▲▲p < 0.0001. E by one-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test, ## p < 0.01.

Figure 4.

Effects of Mrgprb4-lineage neurons activated by Blue light on hind paw thickness and mechanical pain threshold of CFA mice. A Timeline of the CFA injection, TENS, and behavioral testing to study the analgesic and anxiolytic effects of TENS (10Hz, 0.5 mA / 2.0 mA) treatment in CFA mice. B Time course of TENS on hind paw thickness of CFA mice (N=12). C Time course of TENS on mechanical pain thresholds of CFA mice (N=12). Yellow shadow is used to TENS stimuli. D The AUC statistics of each group. All data are shown as mean ± S.E.M. C–D by two-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. Statistical symbols in different colors are represented to denote different groups. Compared with Baseline, ***p < 0.001; Compared between groups at each time point, #p < 0.05,##p < 0.01,###P < 0.001; Compared with CFA+0.5 mA TENS group, ▲▲p < 0.01,▲▲▲▲p < 0.0001. E by one-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test, ## p < 0.01.

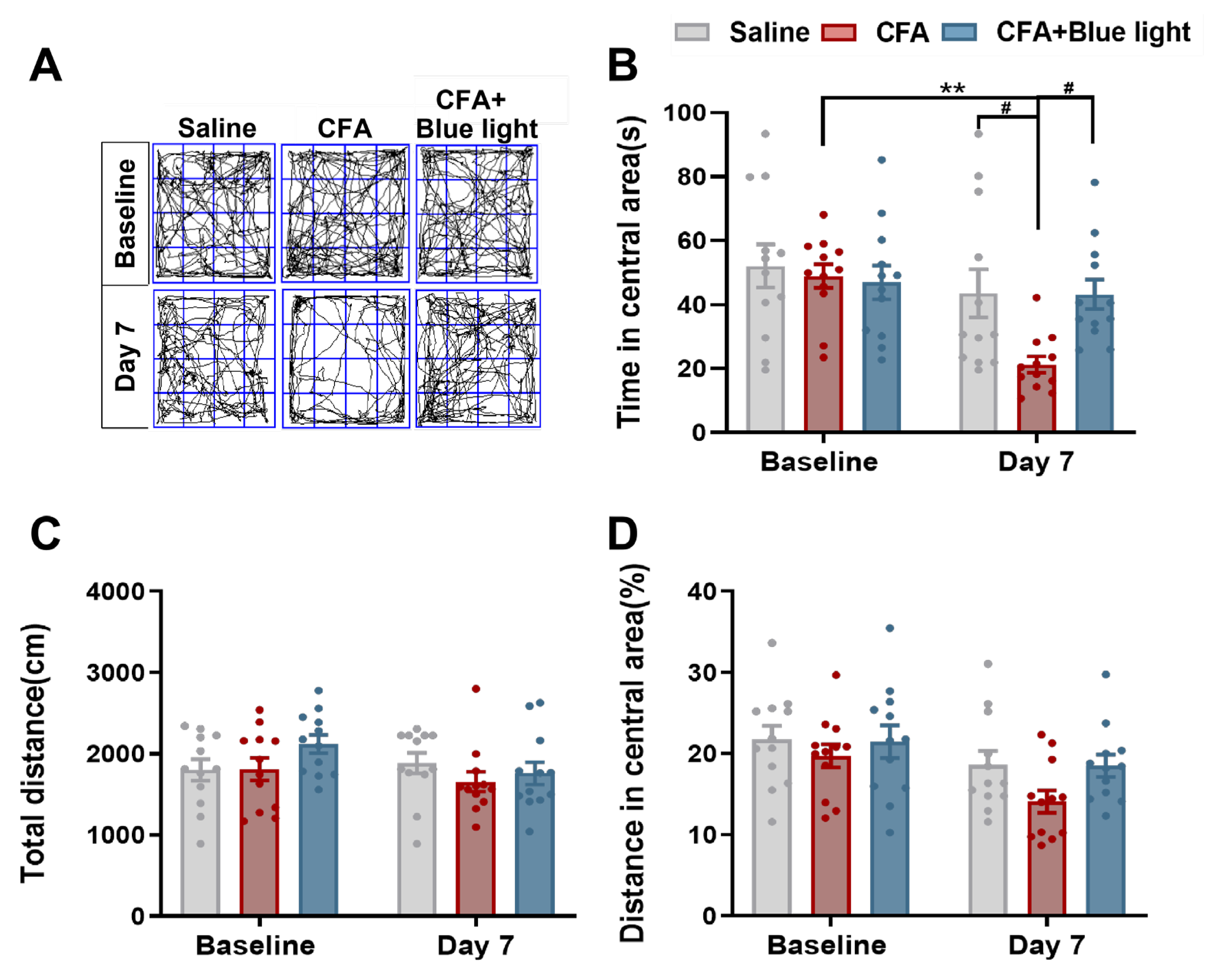

Figure 5.

Effects of Mrgprb4-lineage neuron activated by Blue light on anxiety-like behaviors of CFA mice. A Representative animal tracks of the three groups in the open filed test. B The time in central area of mice in each group (N=12). C The total distance of mice in each group (N=12). D The proportion of the central area to the total distance in each group of mice (N=12).All data are shown as mean ± S.E.M. B-D by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. Compared within each group, **p < 0.01; Comparisons across all groups, ##p < 0.01.

Figure 5.

Effects of Mrgprb4-lineage neuron activated by Blue light on anxiety-like behaviors of CFA mice. A Representative animal tracks of the three groups in the open filed test. B The time in central area of mice in each group (N=12). C The total distance of mice in each group (N=12). D The proportion of the central area to the total distance in each group of mice (N=12).All data are shown as mean ± S.E.M. B-D by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. Compared within each group, **p < 0.01; Comparisons across all groups, ##p < 0.01.

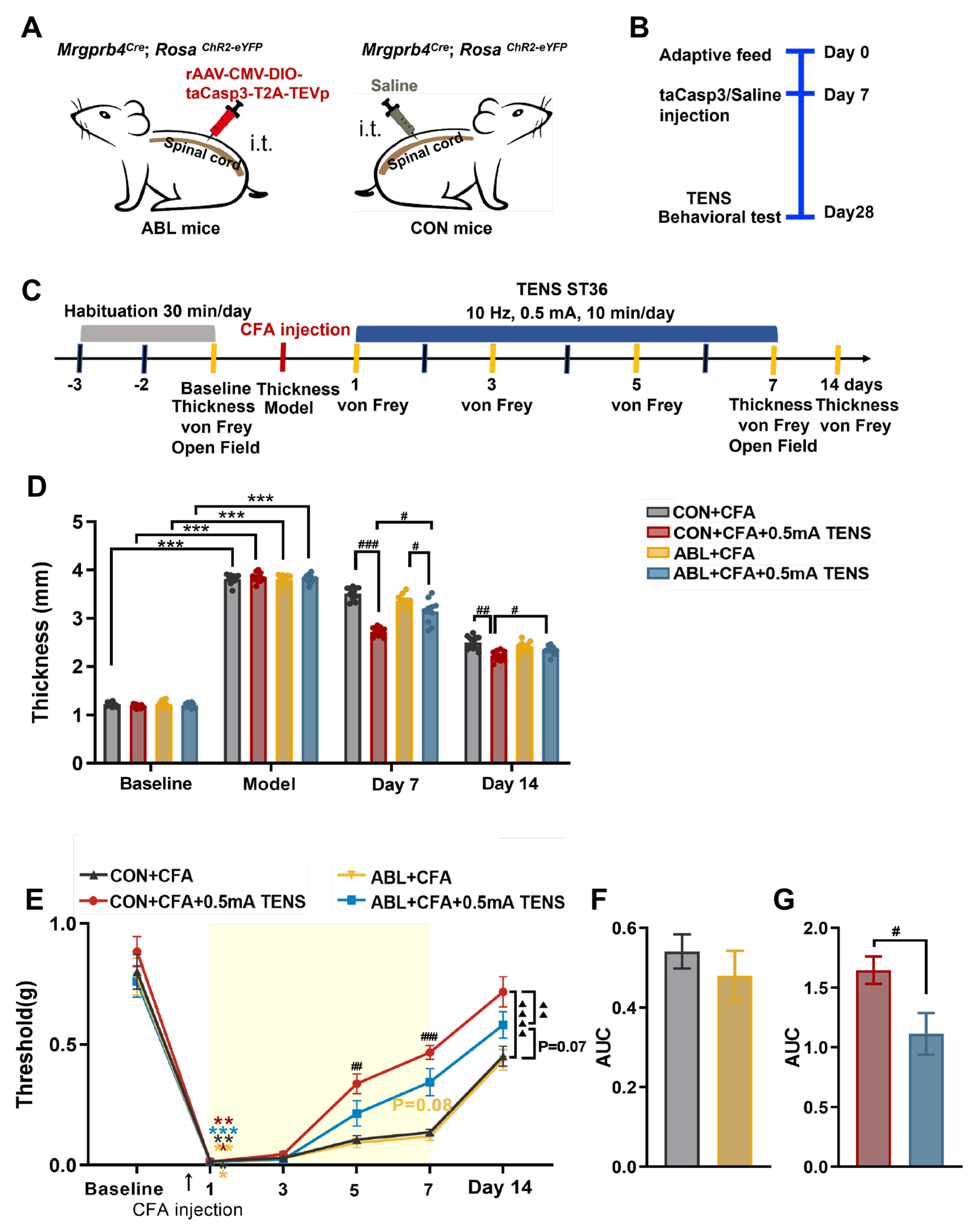

Figure 6.

Effects of virus ablation of Mrgprb4-lineage neurons on hind paw thickness and mechanical pain threshold of CFA mice. A Diagram showing the Mrgprb4-lineage neurons’ virus ablation strategy. ChR2-eYFP is expressed in Mrgprb4-lineage neurons. Intrathecal injection with rAAV-CMV-DIO-taCasp3-T2A-TEVp or Saline in Mrgprb4Cre; RosaChR2-eYFP mice. B Diagram showing the experimental procedure. Adaptive feed on day 0, injection of taCasp3 or saline on day 7, and TENS or behavioral test on day 28. C Timeline of the CFA injection, TENS, and behavioral testing to study the analgesic and anxiolytic effects of TENS (10Hz, 0.5 mA) treatment in CFA mice. D Time course of TENS on hind paw thickness of CFA mice (N=10-12). E Time course of TENS on mechanical pain thresholds of CFA mice (N=10-12). Yellow shadow is used to TENS stimuli. F-G The AUC statistics of each group. All data are shown as mean ± S.E.M. D–E by two-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. Statistical symbols in different colors are represented to denote different groups. Compared with Baseline, ***p < 0.001; Compared between groups at each time point, #p < 0.05,##p < 0.01,###p < 0.001; Comparisons across all groups, ▲▲p < 0.01,▲▲▲▲p < 0.0001. F-G by unpaired t test, #p < 0.05.

Figure 6.

Effects of virus ablation of Mrgprb4-lineage neurons on hind paw thickness and mechanical pain threshold of CFA mice. A Diagram showing the Mrgprb4-lineage neurons’ virus ablation strategy. ChR2-eYFP is expressed in Mrgprb4-lineage neurons. Intrathecal injection with rAAV-CMV-DIO-taCasp3-T2A-TEVp or Saline in Mrgprb4Cre; RosaChR2-eYFP mice. B Diagram showing the experimental procedure. Adaptive feed on day 0, injection of taCasp3 or saline on day 7, and TENS or behavioral test on day 28. C Timeline of the CFA injection, TENS, and behavioral testing to study the analgesic and anxiolytic effects of TENS (10Hz, 0.5 mA) treatment in CFA mice. D Time course of TENS on hind paw thickness of CFA mice (N=10-12). E Time course of TENS on mechanical pain thresholds of CFA mice (N=10-12). Yellow shadow is used to TENS stimuli. F-G The AUC statistics of each group. All data are shown as mean ± S.E.M. D–E by two-way repeated measures ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. Statistical symbols in different colors are represented to denote different groups. Compared with Baseline, ***p < 0.001; Compared between groups at each time point, #p < 0.05,##p < 0.01,###p < 0.001; Comparisons across all groups, ▲▲p < 0.01,▲▲▲▲p < 0.0001. F-G by unpaired t test, #p < 0.05.

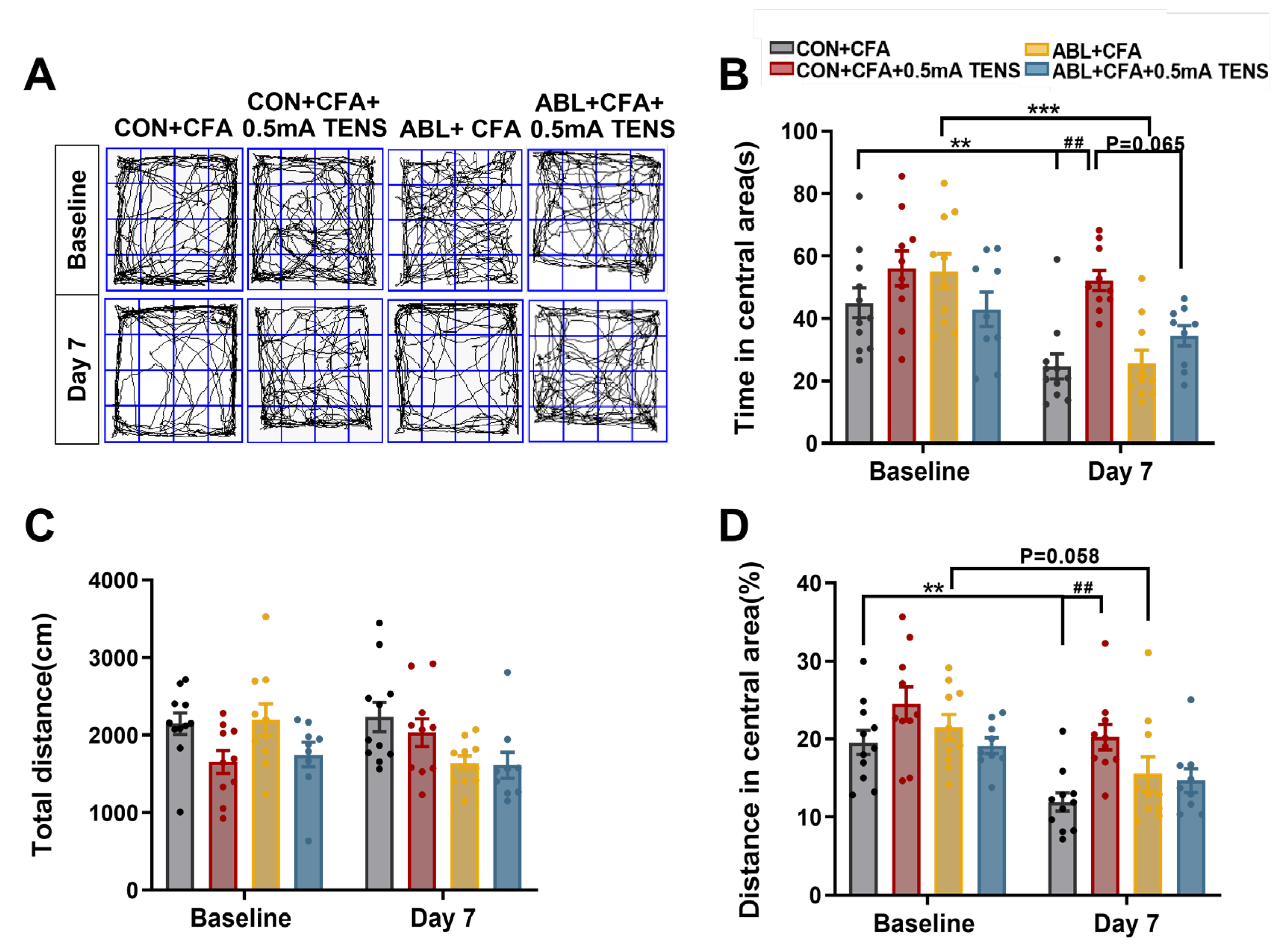

Figure 7.

Effects of virus ablation of Mrgprb4-lineage neurons on anxiety-like behaviors in CFA mice. A Representative animal tracks of the four groups in the open filed test. B The time in central area of mice in each group (N=10-12). C The total distance of mice in each group (N=10-12). D The proportion of the central area to the total distance in each group of mice (N=10-12). All data are shown as mean ± S.E.M. B-D by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. Compared within each group, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001; Comparisons across all groups, ## p < 0.01.

Figure 7.

Effects of virus ablation of Mrgprb4-lineage neurons on anxiety-like behaviors in CFA mice. A Representative animal tracks of the four groups in the open filed test. B The time in central area of mice in each group (N=10-12). C The total distance of mice in each group (N=10-12). D The proportion of the central area to the total distance in each group of mice (N=10-12). All data are shown as mean ± S.E.M. B-D by two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test. Compared within each group, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001; Comparisons across all groups, ## p < 0.01.

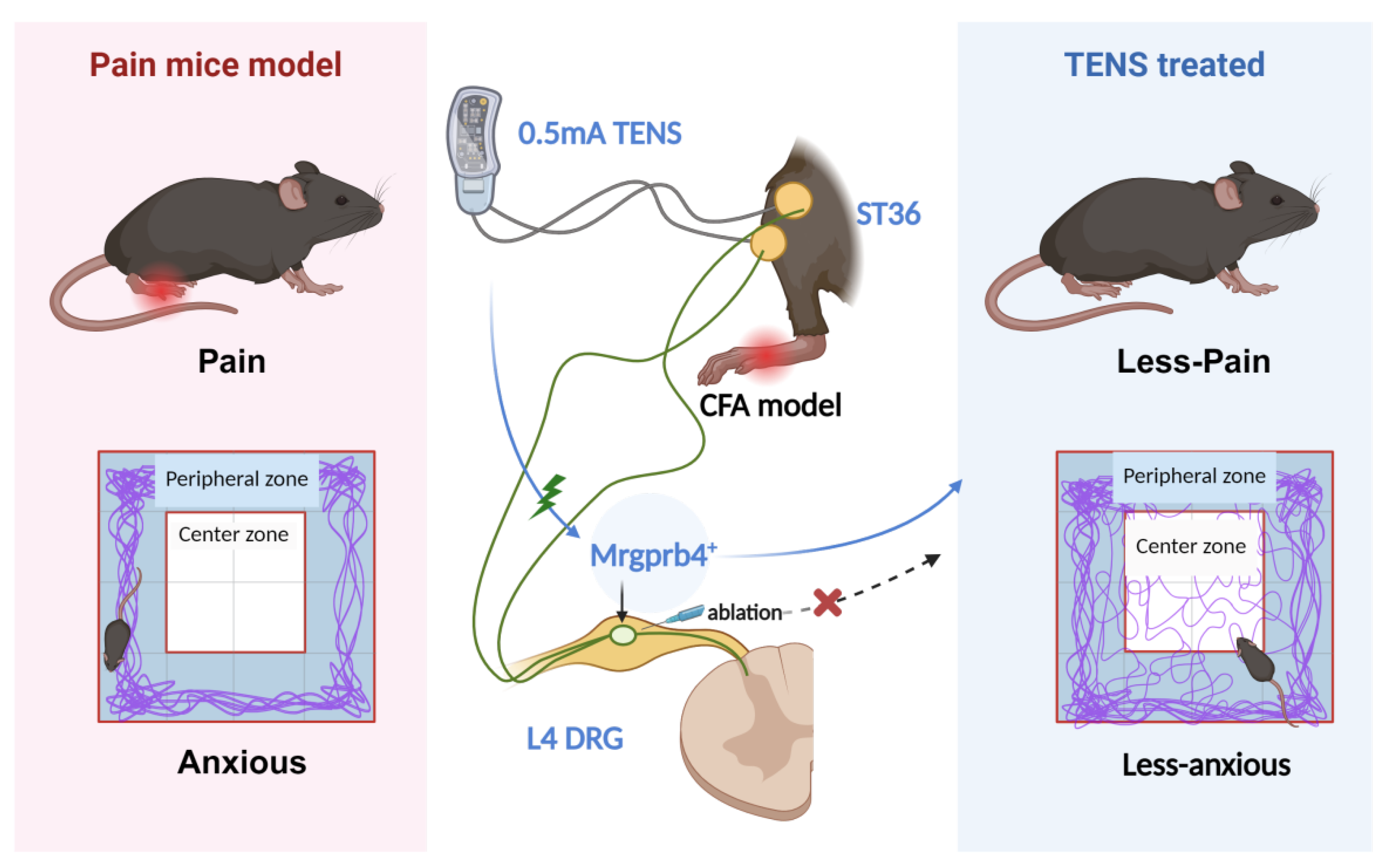

Figure 8.

This schematic diagram depicts the role of Mrgprb4-lineage neurons in TENS-induced analgesia within a CFA-induced inflammatory pain model. Activation of Mrgprb4 neurons in the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) by 0.5 mA TENS alleviates pain and anxiety-like behaviors in mice. Chemogenetic ablation of Mrgprb4 neurons in the L4 DRG, however, significantly abrogates the therapeutic effects of 0.5 mA TENS, confirming the crucial contribution of this neuronal lineage to TENS-mediated pain relief.

Figure 8.

This schematic diagram depicts the role of Mrgprb4-lineage neurons in TENS-induced analgesia within a CFA-induced inflammatory pain model. Activation of Mrgprb4 neurons in the dorsal root ganglion (DRG) by 0.5 mA TENS alleviates pain and anxiety-like behaviors in mice. Chemogenetic ablation of Mrgprb4 neurons in the L4 DRG, however, significantly abrogates the therapeutic effects of 0.5 mA TENS, confirming the crucial contribution of this neuronal lineage to TENS-mediated pain relief.