Introduction

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) affects a substantial proportion of pregnancies worldwide and represents a major contributor to maternal and neonatal morbidity, being associated with increased risks of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, cesarean delivery, abnormal fetal growth, and neonatal metabolic complications [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. This condition is of increasing interest to healthcare systems because of its association with adverse health outcomes in adulthood, particularly an elevated risk of cardiometabolic diseases [

7,

8]. Beyond pregnancy, women with a history of GDM exhibit a significantly increased lifetime risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease, while their offspring are predisposed to obesity and metabolic dysfunction later in life, highlighting the intergenerational impact of dysglycemia during gestation [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Achieving optimal glycemic control during pregnancy therefore represents a primary therapeutic objective to reduce both short- and long-term adverse outcomes.

Medical nutrition therapy (MNT) is universally recommended as the first-line treatment for GDM and constitutes the foundation of clinical management across international guidelines [

1,

11,

12,

13]. Conventional dietary counseling primarily focuses on carbohydrate quality, macronutrient balance, glycemic index, and caloric adequacy to support fetal growth, while limiting maternal hyperglycemia [

11,

12,

13]. However, despite appropriate nutritional counseling and adherence, a substantial proportion of women with GDM require pharmacological therapy, suggesting that key determinants of glycemic regulation may not be fully addressed by current nutrition-based approaches alone [

11,

12,

13].

Chrono nutrition integrates principles of circadian biology into nutritional science by examining how the timing and daily distribution of food intake interact with endogenous circadian rhythms to influence metabolic regulation [

14]. In non-pregnant populations, chrono nutrition-related behaviors—such as late eating, irregular meal timing, and circadian misalignment—have been associated with impaired glucose tolerance, insulin resistance, and increased cardiometabolic risk [

14,

15]. This framework may be particularly relevant in pregnancy, a physiological state characterized by profound endocrine, metabolic, and circadian adaptations, including progressive insulin resistance and altered diurnal patterns of glucose metabolism, which may amplify the metabolic consequences of mistimed nutrient intake [

15,

16].

Circadian Regulation of Glucose Metabolism in Pregnancy

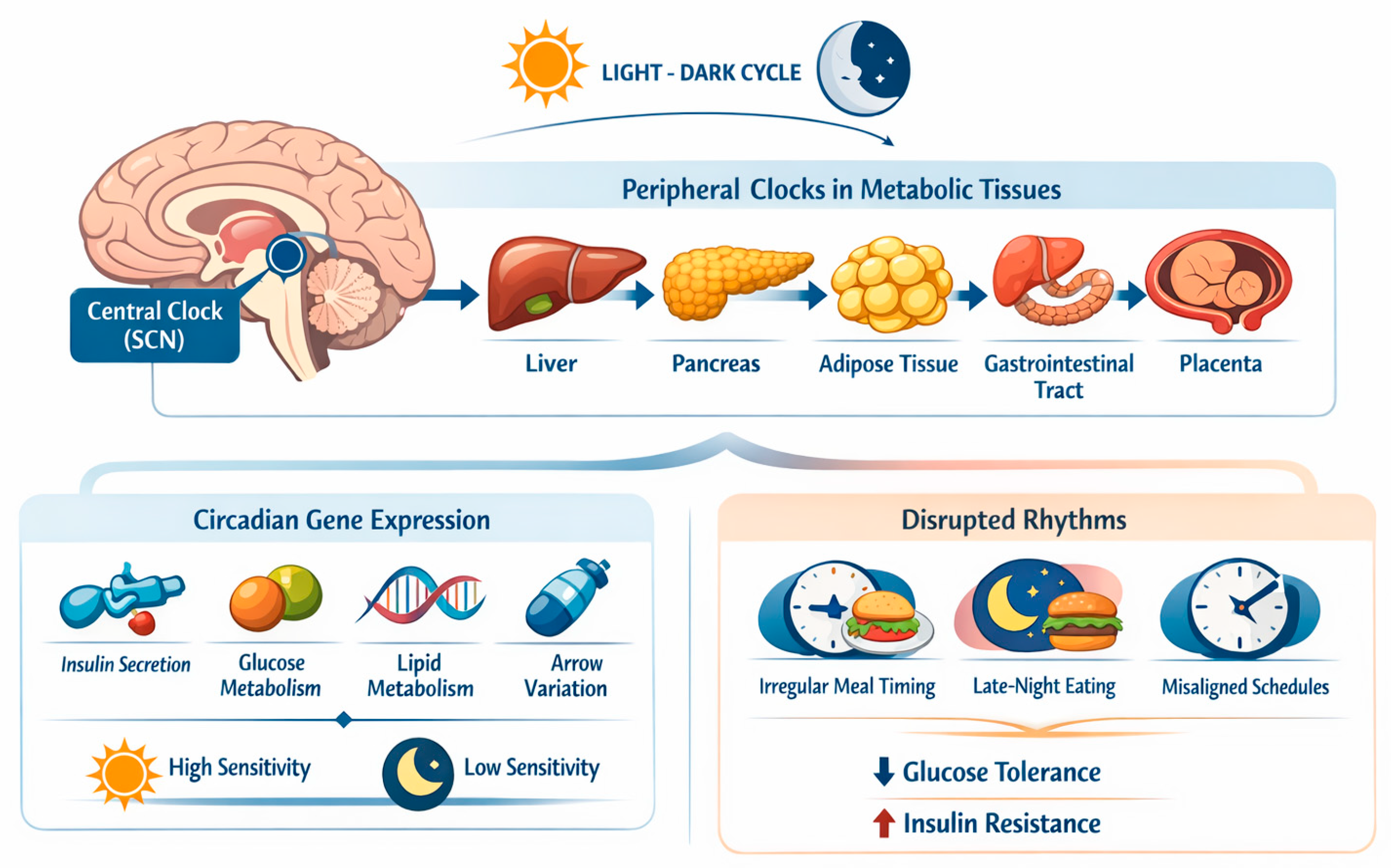

Circadian rhythms are endogenous ~24-hour cycles that regulate metabolic, hormonal, and behavioral processes and are coordinated by a central pacemaker located in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus, which synchronizes peripheral clocks expressed in key metabolic tissues, including the liver, pancreas, adipose tissue, gastrointestinal tract, and placenta [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. While the central clock is mainly entrained by the light–dark cycle, peripheral metabolic clocks are strongly modulated by behavioral cues, with feeding timing acting as one of the most potent zeitgebers, as depicted in

Figure 1 [

22,

23].

At the molecular level, circadian clocks regulate the rhythmic expression of genes involved in insulin secretion, insulin signaling, hepatic gluconeogenesis, glucose transport, and lipid metabolism [

22,

24]. Consequently, glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity exhibit pronounced diurnal variation, even in healthy individuals, with reduced insulin sensitivity typically observed during the biological night [

23,

25]. Circadian misalignment—such as that induced by irregular meal timing, late eating, or misalignment between feeding schedules and endogenous rhythms—has been shown to impair glucose metabolism and promote insulin resistance [

26,

27].

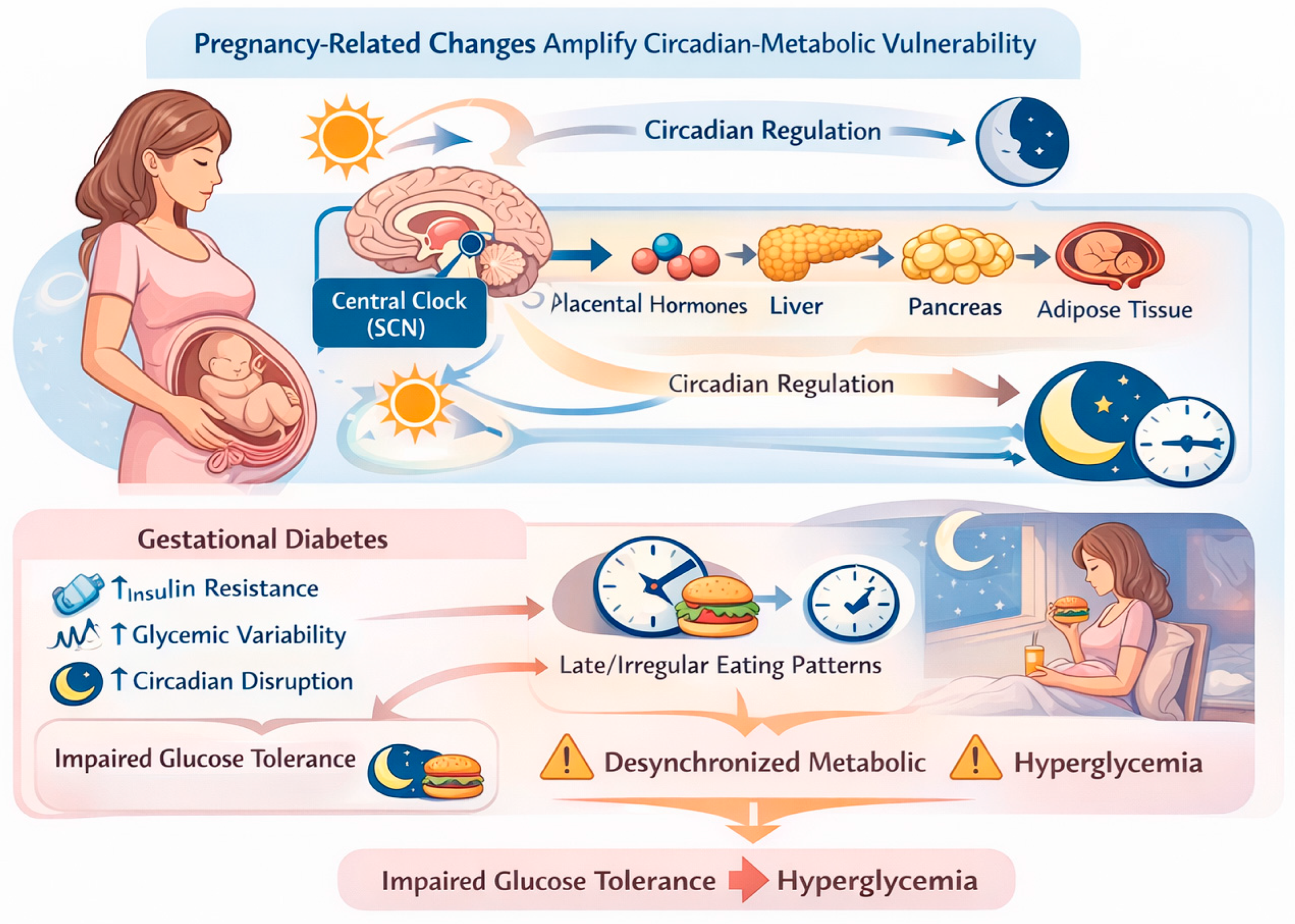

Pregnancy represents a unique physiological state characterized by profound endocrine and metabolic adaptations aimed at supporting fetal growth. Progressive insulin resistance develops across gestation, largely mediated by placental hormones such as human placental lactogen, progesterone, cortisol, and growth hormone [

28,

29]. These pregnancy-related changes interact with circadian regulation of metabolism, potentially amplifying vulnerability to circadian misalignment and time-dependent metabolic stress [

21,

30].

In women with GDM, circadian regulation of glucose metabolism appears further altered. Clinical evidence indicates that diurnal variation in insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance is accentuated in GDM, resulting in marked time-of-day–dependent differences in postprandial glycemic responses [

31]. Late or irregular eating patterns may exacerbate this dysregulation by desynchronizing peripheral metabolic clocks, leading to impaired insulin action, increased hepatic glucose output, and greater glycemic variability [

22,

23,

26], as depicted in

Figure 2.

In line with this physiological framework, a growing body of human evidence, including systematic review data, suggests that delayed meal timing, increased evening carbohydrate consumption, and reduced overnight fasting are associated with less favorable glycemic control in women with GDM [

32]. Furthermore, chrono-nutrition–based interventions targeting meal timing and daily carbohydrate distribution have been shown to improve maternal glycemic profiles, supporting the clinical relevance of circadian regulation as a modifiable determinant of glucose metabolism during pregnancy [

33].

Together, these observations support the concept that circadian regulation constitutes a critical, yet underrecognized, component of glucose homeostasis during pregnancy and that disruption of temporal metabolic organization may contribute to the pathophysiology and clinical expression of GDM.

Chrono Nutrition and Glycemic Control in GDM

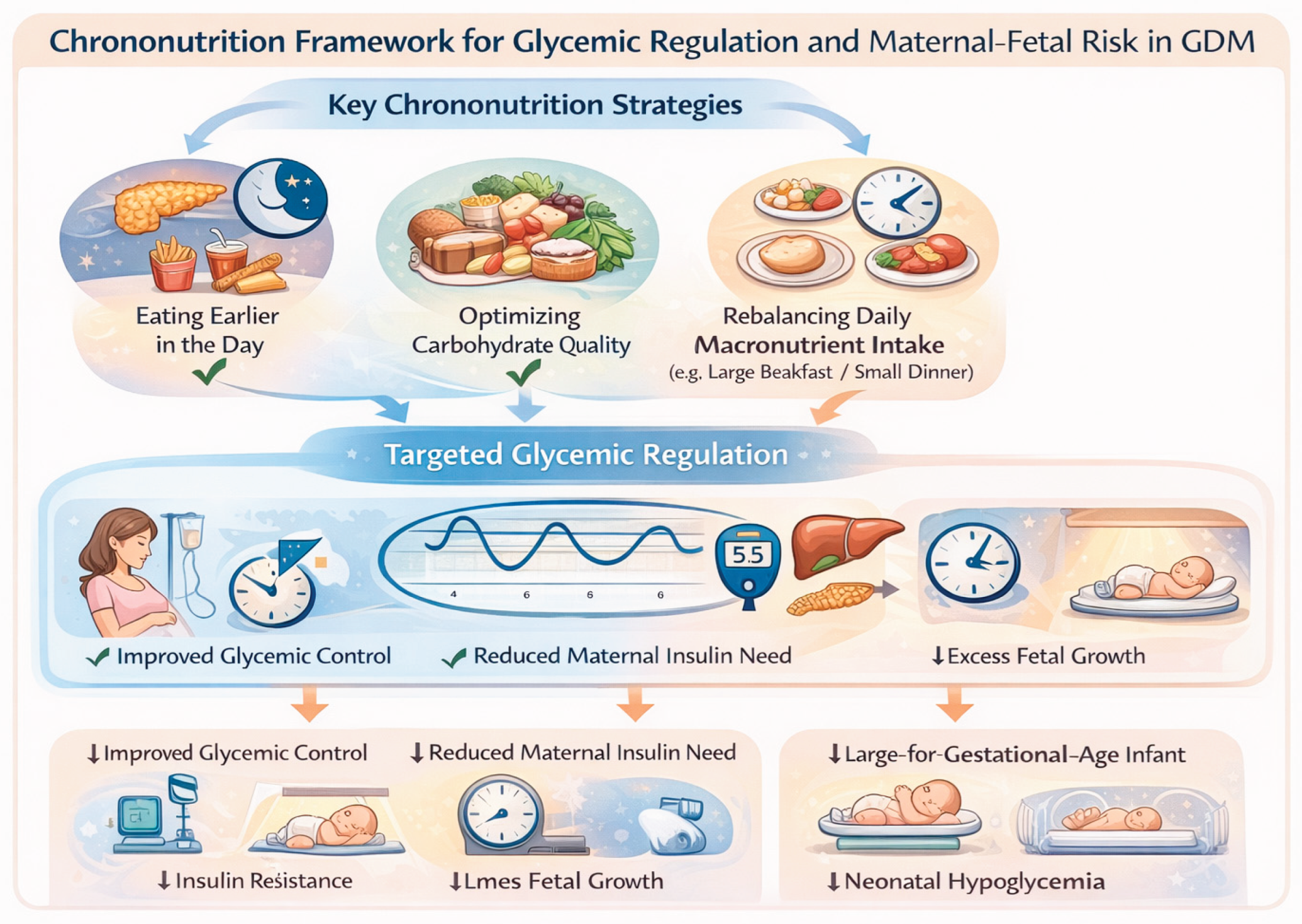

Chrono-nutrition provides a conceptual and practical framework for understanding how the timing and daily distribution of food intake interact with circadian regulation to influence glycemic control (

Figure 3).

In GDM, this interaction is particularly relevant due to the coexistence of pregnancy-induced insulin resistance and accentuated diurnal variation in glucose metabolism [

23,

34].

From a mechanistic perspective, the metabolic response to nutrient intake is strongly time dependent. Insulin sensitivity, pancreatic β-cell responsiveness, incretin secretion, and hepatic glucose production are regulated in a circadian manner, resulting in differential glycemic responses to identical meals consumed at different times of the day [

22,

23,

25,

31]. During pregnancy, these physiological rhythms are generally preserved, but may be amplified, particularly in women with GDM, leading to exaggerated postprandial hyperglycemia during periods of reduced insulin sensitivity, especially in the late afternoon and evening [

25,

31,

32].

Clinical evidence increasingly supports the relevance of chrono-nutrition for glycemic management in GDM. Observational studies and systematic reviews have shown that delayed breakfast timing and later initiation of daily food intake are associated with poorer glycemic control during pregnancy, independent of total energy intake and macronutrient composition [

32,

33]. Delayed morning feeding may prolong the overnight fasting state, exacerbate hepatic glucose output, and delay synchronization of peripheral metabolic clocks, thereby impairing postprandial glucose handling at the first meal of the day [

22,

32,

34].

In addition to breakfast timing, evening carbohydrate intake has emerged as a critical determinant of glycemic control in GDM. Higher carbohydrate consumption during the evening, when insulin sensitivity is physiologically reduced, has been associated with increased postprandial glucose excursions and greater glycemic variability [

32,

35]. Mechanistically, late-day carbohydrate loading coincides with diminished insulin-mediated glucose disposal and altered circadian regulation of hepatic glucose production, promoting prolonged hyperglycemia and potentially increasing fetal glucose exposure [

25,

27].

Interventional evidence further supports a causal role of meal timing in glycemic regulation. A randomized controlled trial combining chrono-nutrition–based dietary counseling with sleep hygiene interventions demonstrated a significant reduction in the risk of suboptimal glycemic control in women with GDM, with reduced evening carbohydrate intake identified as the primary mediator of this effect [

33]. Importantly, these improvements were achieved without substantial changes in total energy intake, underscoring the importance of temporal nutrient distribution rather than caloric restriction per se.

Beyond postprandial glycemia, chrono-nutrition may also influence fasting glucose levels, which represent a common therapeutic challenge in GDM. Late-night eating or inappropriate nocturnal meal timing may disrupt the balance between hepatic glucose production and insulin-mediated suppression, contributing to elevated fasting glucose concentrations [

30]. Conversely, appropriately timed evening meals or snacks with a low glycemic load may help stabilize overnight glucose metabolism, although evidence specific to GDM remains limited and warrants further investigation.

Importantly, chrono-nutrition should be considered an extension of standard medical nutrition therapy rather than a standalone intervention. By aligning nutrient intake with periods of greater metabolic efficiency, chrono-nutrition–based strategies may reduce glycemic excursions, decrease glycemic variability, and potentially limit the need for pharmacological escalation in selected patients with GDM [

25,

33].

Taken together, available evidence indicates that meal timing and daily carbohydrate distribution represent modifiable and clinically meaningful determinants of glycemic control in GDM. While further well-designed randomized controlled trials are required to define optimal chrono-nutrition protocols, current data support the integration of temporal dietary guidance into nutritional counseling for women with GDM.

Meal Timing, Glycemic Variability, and Fetal Implications

Beyond mean glucose levels, increasing evidence indicates that glycemic variability and postprandial glucose excursions represent critical determinants of fetal exposure to maternal hyperglycemia and may independently contribute to adverse neonatal outcomes. Data derived from continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) studies demonstrate that larger postprandial glucose excursions and greater glycemic variability are associated with increased risks of excessive fetal growth and adverse perinatal outcomes, even when mean glycemic indices fall within recommended targets [

36,

37,

38]. In GDM, exaggerated postprandial glycemic peaks are common and may occur despite apparently acceptable average glucose values, underscoring the clinical relevance of dynamic, time-dependent glucose fluctuations beyond static measures of glycemia [

37,

39].

From a physiological standpoint, maternal glucose freely crosses the placenta via facilitated diffusion, whereas insulin does not. Consequently, transient elevations in maternal glucose concentrations directly translate into increased fetal glucose exposure, stimulating fetal pancreatic β-cell hyperplasia and hyperinsulinemia. This mechanism—classically described as fuel-mediated teratogenesis—is central to the pathogenesis of excessive fetal growth, altered body composition, and long-term metabolic programming in pregnancies complicated by diabetes [

40,

41]. Importantly, fetal hyperinsulinemia appears to be driven not only by sustained maternal hyperglycemia, but also by recurrent postprandial glucose excursions, which may exert a disproportionate biological effect on the developing fetus [

36,

42].

Temporal clustering of carbohydrate intake during periods of reduced maternal insulin sensitivity—such as the late evening or biological night—may further exacerbate postprandial hyperglycemia and prolong fetal exposure to elevated glucose concentrations. Circadian variation in maternal insulin action and hepatic glucose production may amplify these effects, resulting in disproportionate glycemic excursions relative to total carbohydrate intake [

19,

24]. This interaction provides a mechanistic rationale for the potential role of chrono-nutrition in modulating fetal growth trajectories through its effects on postprandial glucose dynamics.

Although direct interventional evidence linking chrono-nutrition strategies to neonatal outcomes in GDM remains limited, available physiological and CGM-based data support the hypothesis that reducing glycemic variability and postprandial excursions—through optimized meal timing and carbohydrate distribution—could attenuate fetal hyperinsulinemia and excessive fetal growth. From this perspective, chrono-nutrition–based approaches may represent a valuable complement to traditional glycemic targets, shifting the focus from mean glucose values alone toward the temporal pattern of maternal glycemia.

Fetal Programming and Intergenerational Implications

Beyond immediate glycemic control, the potential implications of chrono nutrition for fetal programming warrant careful consideration. Maternal glucose availability is a critical determinant of the intrauterine metabolic environment, and emerging evidence indicates that not only chronic hyperglycemia but also recurrent postprandial glucose excursions may influence fetal insulin secretion, adiposity, and long-term metabolic trajectories [

32,

33]. In this context, glycemic variability—strongly modulated by meal timing and the diurnal distribution of carbohydrate intake—may represent an underrecognized contributor to fetal metabolic programming [

34].

Chrono nutrition-based strategies aimed at attenuating late-day hyperglycemia and aligning nutrient intake with periods of greater maternal insulin sensitivity may theoretically reduce fetal exposure to excessive glucose and insulin [

43]. Such temporal modulation of maternal metabolism could influence placental nutrient transport and fetal endocrine signaling, with potential downstream effects on birth weight, body composition, and long-term cardiometabolic risk [

20,

21]. Although direct evidence linking chrono nutrition interventions during pregnancy to long-term offspring outcomes remains limited, this hypothesis is biologically plausible and consistent with established models of the developmental origins of health and disease [

10].

From an intergenerational perspective, improving maternal glycemic patterns through physiologically aligned nutritional strategies may confer benefits that extend beyond pregnancy. Given the well-established association between gestational diabetes mellitus and future metabolic disease in both mothers and their offspring, chrono nutrition represents a low-risk and potentially scalable approach to modulate metabolic risk trajectories across generations [

7,

8]. Future longitudinal and interventional studies are required to determine whether optimization of meal timing during pregnancy can translate into sustained improvements in offspring metabolic health [

30].

Limitations and Future Directions

The interpretation of available evidence on chrono nutrition in GDM is subject to several limitations. First, the current literature is characterized by heterogeneous study designs, including observational analyses, small interventional trials, and narrative reviews, which limits direct comparability across studies and precludes quantitative synthesis. Second, chrono nutrition-related exposures—such as meal timing, eating frequency, and daily carbohydrate distribution—are defined and measured inconsistently, often relying on self-reported dietary data that may be prone to recall bias. Interventional studies specifically designed to evaluate chrono nutrition in GDM remain limited in number and sample size, and most have focused primarily on short-term maternal glycemic outcomes. In addition, neonatal and fetal outcomes are inconsistently assessed, and long-term offspring metabolic consequences have not been systematically evaluated. As a result, causal inferences regarding the impact of meal timing on fetal growth and intergenerational metabolic risk remain speculative.

Future research should prioritize adequately powered randomized controlled trials that integrate chrono nutrition-based interventions into standard medical nutrition therapy. The use of continuous glucose monitoring may provide valuable insight into glycemic variability, postprandial excursions, and time-dependent glucose patterns that are not captured by conventional glycemic indices. Furthermore, longitudinal studies with extended follow-up are needed to determine whether optimizing meal timing during pregnancy can influence neonatal outcomes, offspring metabolic health, and long-term cardiometabolic risk in mothers.

Addressing these gaps will be essential to define evidence-based chrono nutrition recommendations and to clarify the role of temporal dietary strategies as part of personalized nutritional care in GDM.

Clinical Implications

Chrono nutrition-based strategies may represent practical and low-burden refinements to standard dietary counseling in GDM. Approaches such as earlier breakfast consumption, redistribution of carbohydrate intake toward earlier daytime hours, and avoidance of late-night eating can be incorporated into routine nutritional care without substantial changes in total energy intake or macronutrient composition.

By aligning nutrient intake with periods of greater insulin sensitivity, these strategies may help reduce postprandial glycemic excursions and glycemic variability, thereby supporting glycemic targets that are clinically relevant in GDM management. Importantly, chrono nutrition principles can be integrated into existing medical nutrition therapy frameworks and tailored to individual lifestyles, cultural eating patterns, and sleep–wake schedules.

While chrono nutrition should not replace established guideline-based recommendations, its incorporation into dietary counseling may enhance personalization of care and provide clinicians with an additional, physiologically grounded tool to optimize glycemic control in women with gestational diabetes mellitus

Conclusions

Chrono nutrition represents an emerging and physiologically grounded framework for refining nutritional management in GDM. By integrating the temporal organization of eating with established principles of medical nutrition therapy, chrono nutrition offers a complementary perspective that addresses not only what and how much is consumed, but also when nutrients are ingested in relation to circadian metabolic rhythms.

Available evidence suggests that meal timing and daily carbohydrate distribution may meaningfully influence maternal glycemic patterns, glycemic variability, and postprandial glucose excursions—factors that are increasingly recognized as clinically relevant in GDM management. Moreover, biological plausibility and preliminary clinical data support the hypothesis that temporally aligned nutritional strategies may modulate fetal glucose exposure and potentially influence neonatal growth trajectories.

Despite these promising observations, the current evidence base remains limited, and causality cannot yet be established. Chrono nutrition should therefore be viewed as a low-risk, hypothesis-driven extension of standard dietary counseling rather than a replacement for existing guideline-based approaches. Well-designed randomized trials and longitudinal studies are needed to define optimal chrono nutrition strategies and to clarify their impact on maternal and offspring metabolic outcomes.

In conclusion, incorporating temporal aspects of eating into nutritional care may represent a step toward more physiologically aligned and personalized management of GDM, with potential implications that extend beyond pregnancy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.T.; methodology, S.T.; writing—original draft preparation S.T.; writing—review and editing, S.T.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not appliable.

Conflicts of Interest

No conflicts of interest.

References

- American Diabetes Association. Management of diabetes in pregnancy: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care 2024, 47 (Suppl 1), S254–S266. [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre, HD; Catalano, P; Zhang, C; Desoye, G; Mathiesen, ER; Damm, P. Gestational diabetes mellitus. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2019, 5(1), 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landon, MB; Spong, CY; Thom, E; et al. A multicenter, randomized trial of treatment for mild gestational diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2009, 361(14), 1339–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triunfo, S; Lanzone, A. Impact of overweight and obesity on obstetric outcomes. J Endocrinol Invest. 2014, 37(4), 323–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triunfo, S; Lanzone, A. Potential impact of maternal vitamin D status on obstetric well-being. J Endocrinol Invest. 2016, 39(1), 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triunfo, S; Lanzone, A; Lindqvist, PG. Low maternal circulating levels of vitamin D as potential determinant in the development of gestational diabetes mellitus. J Endocrinol Invest. 2017, 40(10), 1049–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A; Tan, B; Du, R; et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus and development of intergenerational overall and subtypes of cardiovascular diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2024, 23, 320. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, CK; Campbell, S; Retnakaran, R; et al. Gestational diabetes and the risk of cardiovascular disease in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia 2019, 62(6), 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellamy, L; Casas, JP; Hingorani, AD; Williams, D. Type 2 diabetes mellitus after gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2009, 373(9677), 1773–1779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dabelea, D; Crume, T. Maternal environment and the transgenerational cycle of obesity and diabetes. Diabetes 2011, 60(7), 1849–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups (IADPSG). Recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Care 2010, 33(3), 676–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 15. Management of Diabetes in Pregnancy: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2025. Diabetes Care 2025, 48 (Supplement_1), S306–S320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO recommendations on care for women with diabetes during pregnancy. In Geneva: World Health Organization; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; 2025.

- Garaulet, M; Gómez-Abellán, P. Chronobiology and obesity. Nutr Hosp. 2013, 28 (Suppl 5), 114–120. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, JD. Physiological responses to food intake throughout the day. Nutr Res Rev. 2014, 27(1), 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reutrakul, S; Van Cauter, E. Interplay between sleep, circadian rhythms, and glucose metabolism. Endocr Rev. 2014, 35(5), 718–738. [Google Scholar]

- Messika, A; Toledano, Y; Hadar, E; Tauman, R; Froy, O; Shamir, R. Chronobiological factors influencing glycemic control and birth outcomes in gestational diabetes mellitus. Nutrients 2025, 17, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, MH; Maywood, ES; Brancaccio, M. Generation of circadian rhythms in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2018, 19(8), 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohawk, JA; Green, CB; Takahashi, JS. Central and peripheral circadian clocks in mammals. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2012, 35, 445–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astiz, M; Oster, H. The placenta: a key element in the circadian communication between mother and fetus. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2020, 11, 198. [Google Scholar]

- Wharfe, MD; Mark, PJ; Waddell, BJ. Circadian variation in placental and metabolic function. Placenta 2012, 33(7), 523–529. [Google Scholar]

- Schibler, U; et al. Time to eat reveals the hierarchy of peripheral clocks. Trends Cell Biol. 2021, 31(12), 1010–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flanagan, A; Bechtold, DA; Pot, GK; Johnston, JD. Feeding rhythms and the circadian regulation of metabolism. Front Nutr. 2020, 7, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Saini, C; et al. Regulation of insulin secretion by the circadian clock. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2019, 30(10), 636–649. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, JD. Physiological responses to food intake throughout the day. Proc Nutr Soc. 2014, 73(1), 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leproult, R; Holmback, U; Van Cauter, E. Circadian misalignment augments markers of insulin resistance and inflammation. Diabetes 2014, 63(6), 1860–1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, CJ; et al. Circadian system, sleep, and glucose tolerance in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016, 101(3), 1066–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, LA; et al. Cellular mechanisms for insulin resistance in pregnancy. Lancet 2007, 369(9569), 1697–1705. [Google Scholar]

- Sferruzzi-Perri, AN; Cuffe, JSM. Placental endocrine regulation of maternal metabolism. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22(23), 12722. [Google Scholar]

- Reiter, RJ; et al. Circadian regulation and pregnancy metabolism. Endocr Rev. 2014, 35(2), 139–170. [Google Scholar]

- Jovanovic, L; et al. Time-of-day differences in glucose tolerance during pregnancy. Diabetes Care 2011, 34(1), 27–31. [Google Scholar]

- Boege, HL; Park, C; Gagnier, R; Deierlein, AL. Timing of eating and glycemic control during pregnancy: a systematic review. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2025, 35, 104094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messika, A; Toledano, Y; Hadar, E; et al. Chrono nutrition and glycemic control in gestational diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM 2022, 4(4), 100660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, JD; Ordovás, JM; Scheer, FAJL; Turek, FW. Circadian rhythms, metabolism, and chrononutrition. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2023, 19, 630–648. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, RM; et al. Timing of carbohydrate intake and glycaemic control. Nutrients 2022, 14(6), 1234. [Google Scholar]

- Feig, DS; Donovan, LE; Corcoy, R; et al. Continuous glucose monitoring in pregnant women with type 1 diabetes (CONCEPTT): a multicentre international randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2017, 390(10110), 2347–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, JM; Kellett, JE; Balsells, M; et al. Gestational diabetes mellitus and continuous glucose monitoring: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2020, 43(5), 1146–1155. [Google Scholar]

- Resi, V; Bianchi, C; Burlina, S; et al. The use of technology in diabetes in pregnancy: a position statement of expert opinion from the association of medical diabetologists (AMD), the Italian society of diabetology (SID) and the interassociative diabetes and pregnancy study group. Acta Diabetol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, TL; Barbour, LA. A standard approach to gestational diabetes mellitus using continuous glucose monitoring. Curr Diab Rep. 2013, 13(6), 762–770. [Google Scholar]

- Freinkel, N. Banting Lecture 1980: of pregnancy and progeny. Diabetes. 1980, 29(12), 1023–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desoye, G; Nolan, CJ. The fetal glucose steal: an underappreciated phenomenon in diabetic pregnancy. Diabetologia 2016, 59(6), 1089–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnier, L; Colette, C. Glycemic variability: should we and can we prevent it? Diabetes Care 2008, 31 (Suppl 2), S150–S154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xega, V; Liu, JL. Chrono nutrition in gestational diabetes: toward precision timing in maternal care. J Pers Med. 2025, 15(11), 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).