Submitted:

20 January 2026

Posted:

21 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

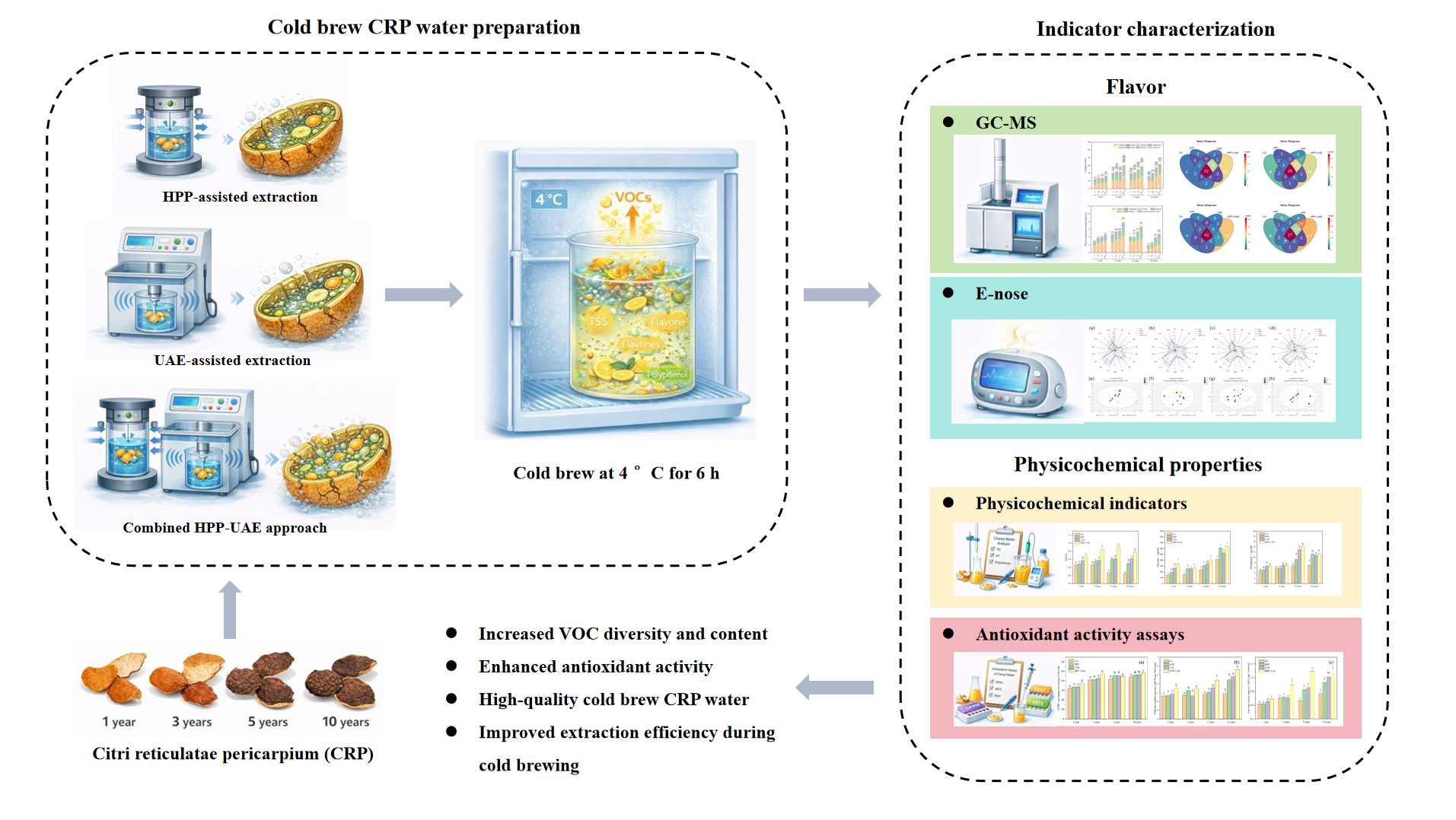

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Sample Preparation

2.2.2. Color

2.2.3. TSS

2.2.4. Total Sugar

2.2.5. Total Flavonoid Content

2.2.6. Total Polyphenol Content

2.2.7. Antioxidant Activity

2.2.8. Amino Acid Composition

2.2.9. E-Nose

2.2.10. HS- SPME-GC-MS

2.2.11. Sensory Evaluation

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

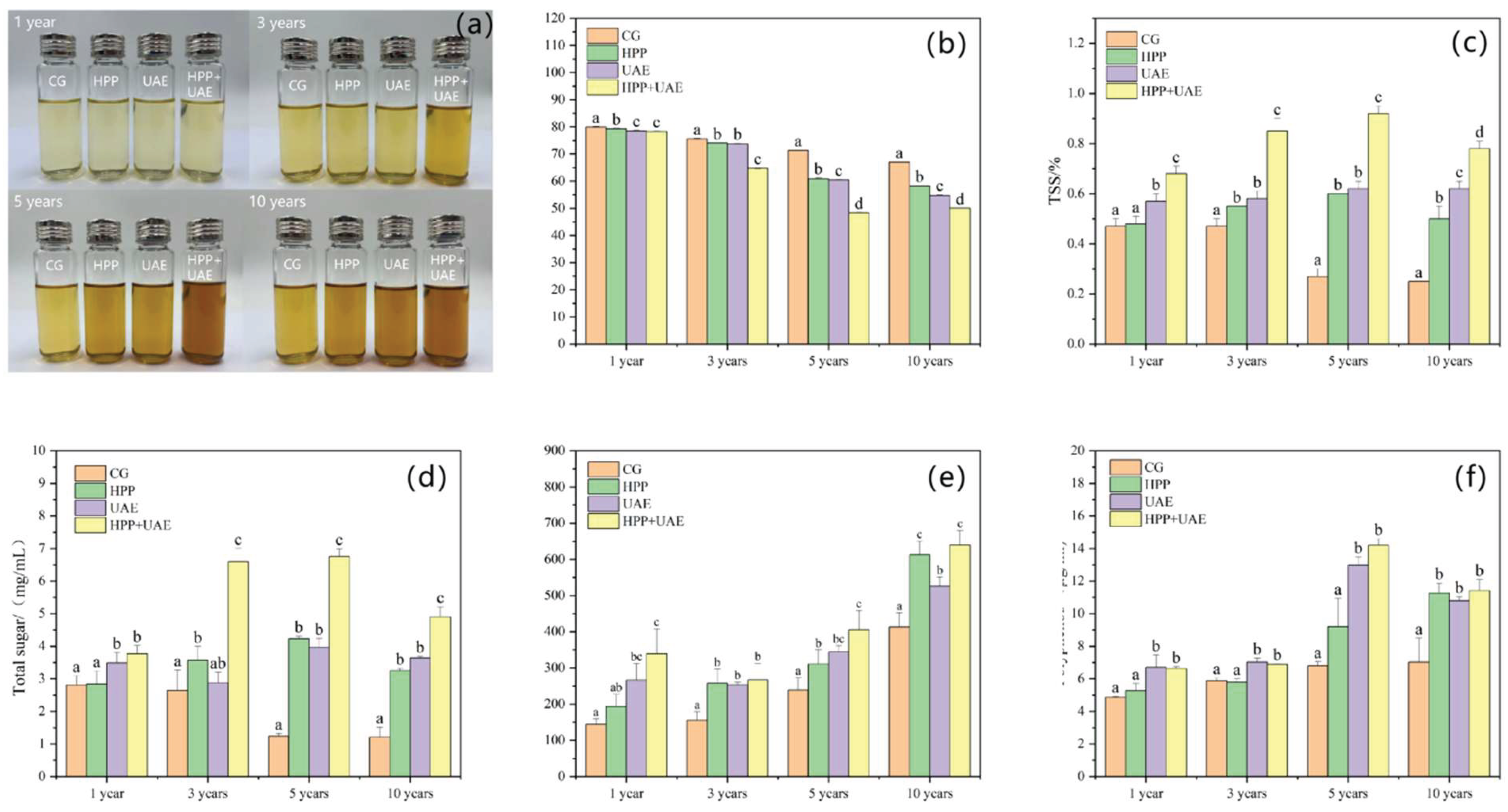

3.1. Effects of Extraction Methods on Physicochemical Properties

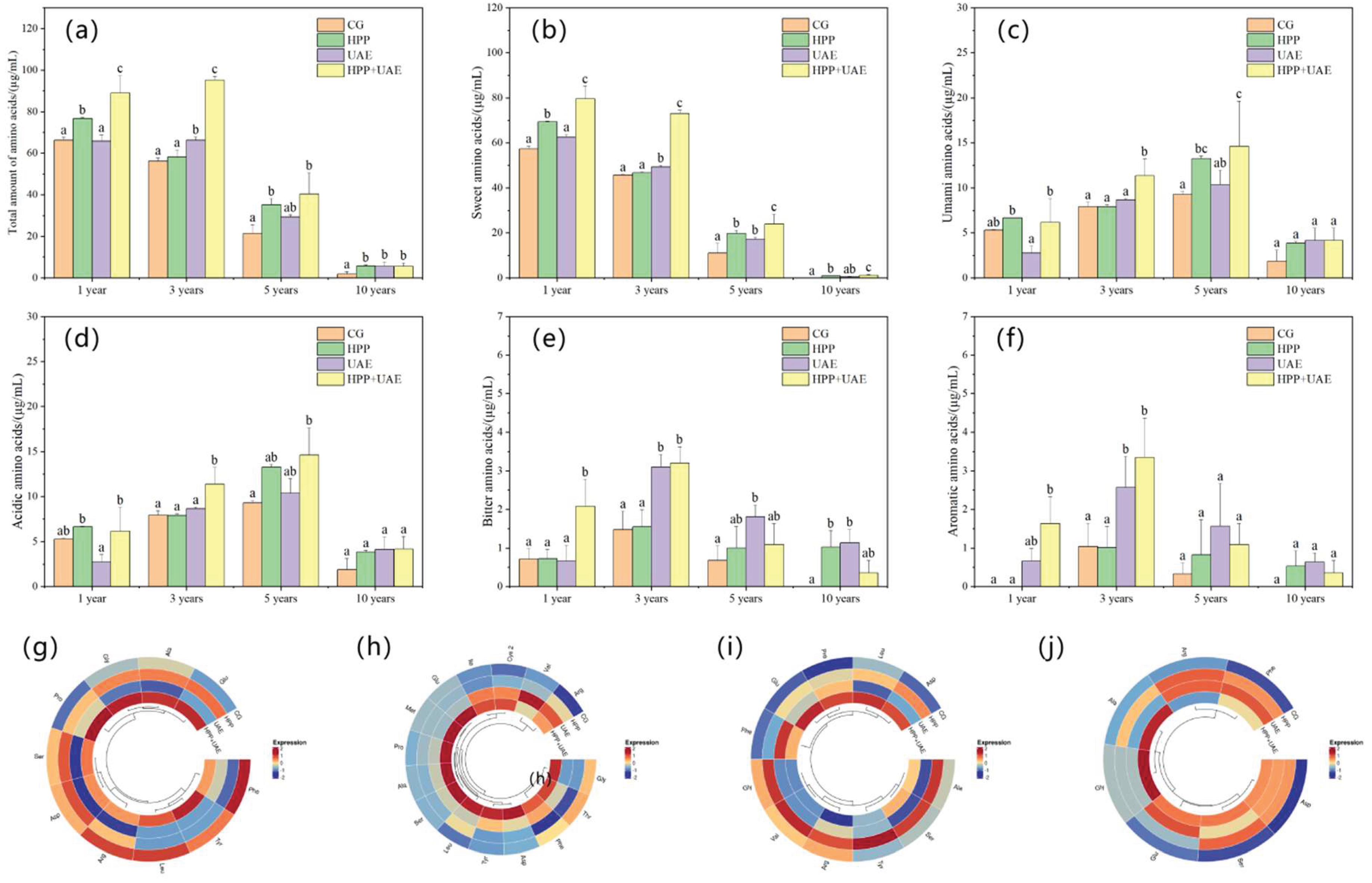

3.2. Effects of Extraction Methods on Amino Acid Composition

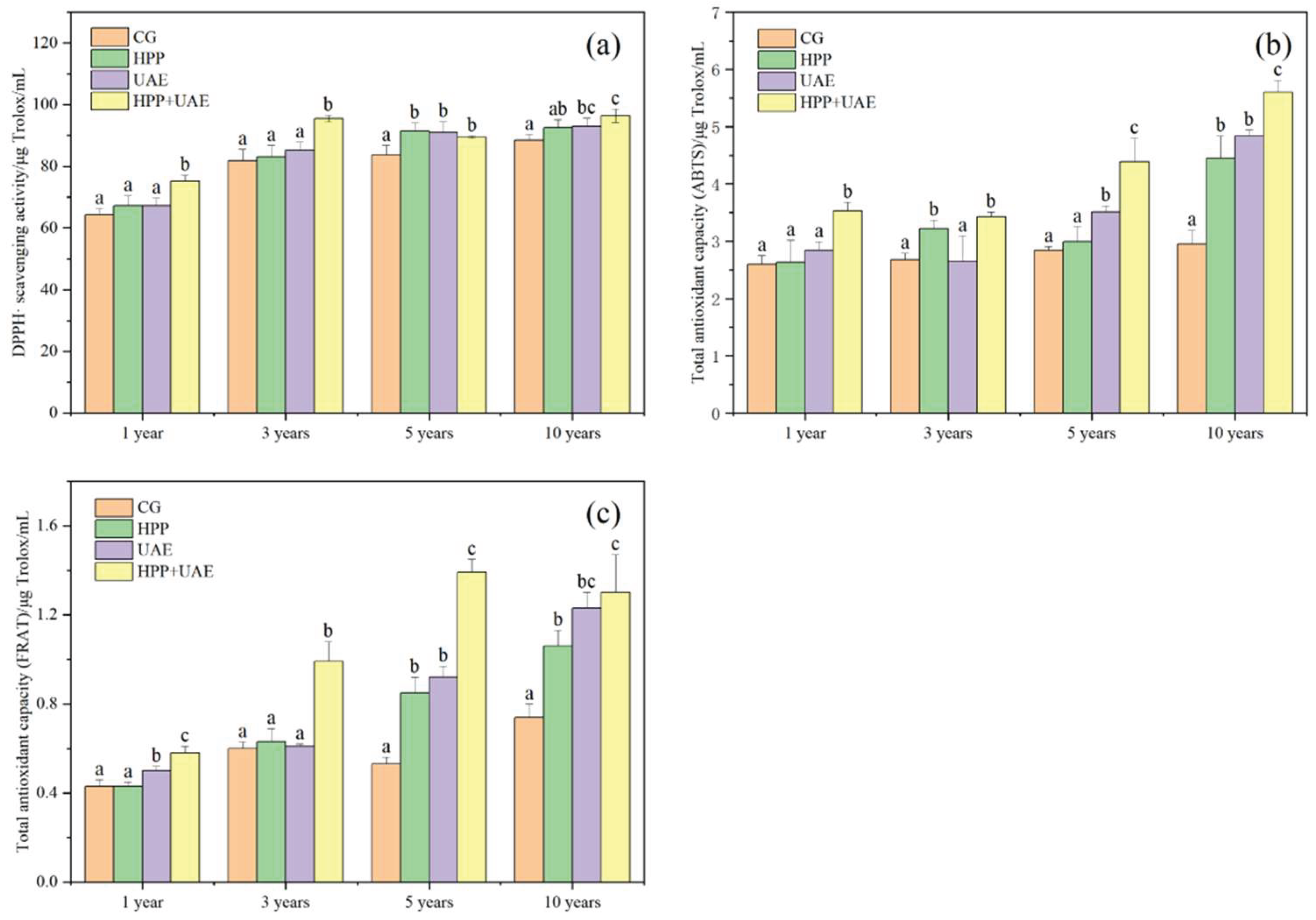

3.3. Effects of Extraction Methods on Antioxidant Activity

3.4. Effects of Extraction Methods on VOCs

3.4.1. Flavor Compounds

3.4.2. Differential Flavor Compound Analysis

3.5. E-Nose

3.6. Correlation Analysis Between Antioxidant Indices and Physicochemical Parameters

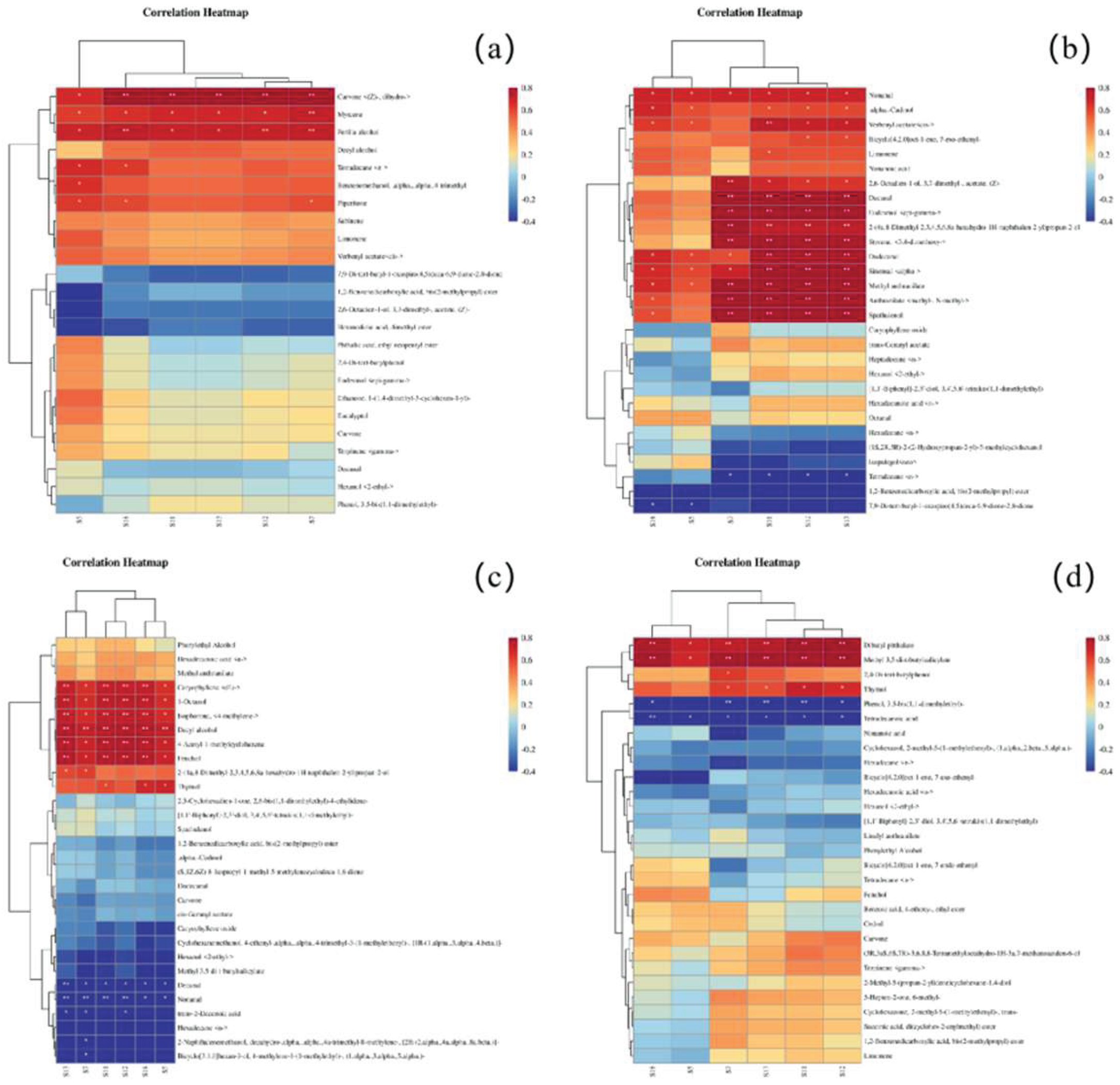

3.7. Correlation Analysis Between E-Nose and GC-MS

3.8. Sensory Evaluation

4. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Data Availability Statement

References

- Liu, H.; Liu, D.; Wang, W.; Zhang, X.; Tuly, J.; Li, H.; Ma, H. Dual-frequency countercurrent ultrasonic-assisted extraction of the cold brew coffee and in situ real-time monitoring of extraction process. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2024, 111, 107118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Lv, W.; Wu, B.; Dou, W.; Wang, H. Β-Glucosidase combined with stir-ultrasound enhances the flavour of cold-extracted green tea: characterisation and evaluation by GC–MS and GC-IMS. Food Research International 2025, 221, 117290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwicker, M.; Phillips, J.; Lim, L.-T. Novel continuous cold brewing method for coffee using a combined screw extraction and mechanical expression approach. Journal of Food Engineering 2024, 383, 112242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oussou, K.F.; Guclu, G.; Sevindik, O.; Kelebek, H.; Starowicz, M.; Selli, S. GC-MS-Olfactometric Characterization of Volatile and Key Odorants in Moringa (Moringa oleifera) and Kinkeliba (Combretum micranthum G. Don) Herbal Tea Infusions Prepared from Cold and Hot Brewing. Separations 2023, 10, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donlao, N.; Sim, C.; Singh, J.; Kaur, L.; Tian, J.; Phongthai, S.; Tanongkankit, Y.; Issara, U.; Phungamngoen, C.; Tongdeesoontorn, W.; et al. Comparative evaluation of high-pressure processing and conventional pasteurization in cold brew green tea: In vitro digestibility, bioavailability, and nutrient stability. Food Chemistry: X 2026, 33, 103473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, A.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, K.; Xu, K.; Meng, F.; Wu, W.; Li, Z.; Wang, B. Study on ultrasound-assisted extraction of cold brew coffee using physicochemical, flavor, and sensory evaluation. Food Bioscience 2024, 61, 104455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, H.; Park, H.; Lee, K.-G. Analysis of physicochemical properties of cold brew Robusta and decaffeinated coffee prepared via ultrasound-assisted soaking and extraction. Food Chemistry 2026, 500, 147509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, M.; Guo, Q.; Xiao, Z.; Sarengaowa; Xiao, Y.; Feng, K. Recent Advances in the Health Benefits and Application of Tangerine Peel (Citri Reticulatae Pericarpium): A Review. Foods 2024, 13, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Li, M.; Yu, Y.; Wu, J.; Wen, J.; San Cheang, W.; Xu, Y. Metabolomics reveal changes of flavonoids during processing of “nine-processed” tangerine peel (Jiuzhi Chenpi). LWT 2024, 214, 117132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Cao, Y.; Ho, C.-T.; Jin, S.; Huang, Q. Aged citrus peel (chenpi) extract reduces lipogenesis in differentiating 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Journal of Functional Foods 2017, 34, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Hu, H.; Yang, H.; Xiong, L.; Zheng, J.; Zhu, T.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, H. Structural characterization and probiotic activity of Chenpi polysaccharides prepared by fermentation with Bacillus licheniformis. Food Bioscience 2025, 74, 107789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wei, W.; Chen, Y.; Zhao, J.; Fu, M.; Wang, X. Research Progress on Geographical Origin Traceability and Authentication of Citri Reticulatae Pericarpium. Food Science 2024, 45, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepsongkroh, B.; Thaihuttakij, C.; Supawong, S.; Jangchud, K. Impact of high pressure pre-treatment and hot water extraction on chemical properties of crude polysaccharide extract obtained from mushroom (Volvariella volvacea). Food Chemistry: X 2023, 19, 100864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallarés, N.; Berrada, H.; Tolosa, J.; Ferrer, E. Effect of high hydrostatic pressure (HPP) and pulsed electric field (PEF) technologies on reduction of aflatoxins in fruit juices. LWT 2021, 142, 111000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.; Lee, C.; Cha, E.; Hwang, K.; Park, S.-K.; Baik, O.-D.; Yu, D. Enhancement of antioxidant properties of Eisenia bicyclis extracts through combination of green extractions: Parameter optimization and comparison. LWT 2024, 213, 117005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, S.; Yu, C.; Zaeim, D.; Wu, D.; Hu, X.; Ye, X.; Chen, S. Increasing RG-I content and lipase inhibitory activity of pectic polysaccharides extracted from goji berry and raspberry by high-pressure processing. Food Hydrocolloids 2022, 126, 107477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Xu, Y.; Dorado, C.; Chau, H.K.; Hotchkiss, A.T.; Cameron, R.G. Modification of pectin with high-pressure processing treatment of fresh orange peel before pectin extraction: Part I. The effects on pectin extraction and structural properties. Food Hydrocolloids 2024, 149, 109516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ijod, G.; Nawawi, N.I.M.; Sulaiman, R.; Ismail-Fitry, M.R.; Adzahan, N.M.; Anwar, F.; Azman, E.M. Elevating anthocyanin extraction from mangosteen pericarp: A comparative exploration of conventional and emerging non-thermal technology. Food Chemistry: X 2024, 24, 101882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, J.; Pei, Y.; Dong, N.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhou, X.; Liu, H. Separation of the active components from the residue of Schisandra chinensis via an ultrasound-assisted method. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2025, 114, 107241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallouch, O.; Bounasser, B.; Asbbane, A.; Giuffrè, A.M.; Abdulmonem, W.A.; Bouyahya, A.; Majourhat, K.; Gharby, S. Enrichment of refined sunflower oil with phenolic extracts from argan (Argania spinosa L. (Skeels)) co-products using ultrasound-assisted extraction. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2025, 122, 107624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fikry, M.; Jafari, S.; Shiekh, K.A.; Kijpatanasilp, I.; Khongtongsang, S.; Khojah, E.; Aljumayi, H.; Assatarakul, K. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of bioactive compounds from longan seeds powder: Kinetic modelling and process optimization. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2024, 108, 106949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhu, H.; Du, W.; Li, G.; Zhao, Y.; Song, K.; Qiu, J.; Liu, J.; Fang, S. Effect of ultrasound-assisted extraction combined with enzymatic pretreatment on bioactive compounds, antioxidant capacity and flavor characteristics of grape pulp extracts. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2025, 121, 107572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duppeti, H.; Nakkarike Manjabhatta, S.; Bheemanakere Kempaiah, B. Optimization of ultrasonic-assisted extraction of flavor compounds from shrimp by-products and characterization of flavor profile of the extract. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2023, 101, 106651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wang, J.; Yuan, H.; Ouyang, W.; Li, J.; Hua, J.; Jiang, Y. Effects of Fermentation Temperature and Time on the Color Attributes and Tea Pigments of Yunnan Congou Black Tea. Foods 2022, 11, 1845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, R.; Tao, Y.; Xu, T.; Wu, T.; Yu, Q.; Pan, S.; Xu, X. Antioxidant activity increased due to dynamic changes of flavonoids in orange peel during Aspergillus niger fermentation. International Journal of Food Science and Technology 2023, 58, 3329–3336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andaleeb, R.; Zhang, D.; Jiang, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y. Volatile profile and multivariant analysis of Sanhuang chicken breast in combination with Chinese 5-spice blend and garam masala. Food Science and Human Wellness 2023, 12, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Ye, X.; Ding, T.; Sun, X.; Xu, Y.; Liu, D. Ultrasound effects on the degradation kinetics, structure and rheological properties of apple pectin. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2013, 20, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Yan, X.; Azarakhsh, N.; Huang, X.; Wang, C. Effects of high-pressure pretreatment on acid extraction of pectin from pomelo peel. International Journal of Food Science and Technology 2022, 57, 5239–5249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.-n.; Xie, S.-m.; Dai, Y.-t. Study on the change of compositions and Maillard Browning reaction in Guang Citri reticulatae Pericarpium during ageing. Journal of Guangdong Pharmaceutical University 2023, 39, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Z.; Xi, W.; Hu, Y.; Nie, C.; Zhou, Z. Antioxidant activity of Citrus fruits. Food Chemistry 2016, 196, 885–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Zheng, Y.-J.; Wu, D.-T.; Du, X.; Gao, H.; Ayyash, M.; Zeng, D.-G.; Li, H.-B.; Liu, H.-Y.; Gan, R.-Y. Quality evaluation of citrus varieties based on phytochemical profiles and nutritional properties. Frontiers in Nutrition 2023, 10, 1165841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, J.; Wang, P.; Xu, H.; Gan, X.; Zhang, H.; Chen, L.; Chen, H.; Wang, F.; Hu, Y.; Liu, Y. Metabolic profile and bioactivity of the peel of Zhoupigan (Citrus reticulata cv. Manau Gan), a special citrus variety in China, based on GC–MS, UPLC-ESI-MS/MS analysis, and in vitro assay. Food Chemistry: X 2024, 23, 101719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Fu, M.; Wu, J.; Yu, Y.; Si, W.; Xu, Y.; Yang, J. Flavor characterization of aged Citri Reticulatae Pericarpium from core regions: An integrative approach utilizing GC-IMS, GC–MS, E-nose, E-tongue, and chemometrics. Food Chemistry 2025, 490, 144995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; Xiang, F.; He, F. Polyphenols from Artemisia argyi leaves: environmentally friendly extraction under high hydrostatic pressure and biological activities. Industrial Crops and Products 2021, 171, 113951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, J.; Luo, S. The mechanism for enhancing extraction of ferulic acid from Radix Angelica sinensis by high hydrostatic pressure. Separation and Purification Technology 2016, 165, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehzadi, F.; Shoaib, M.; Munir, S.; Abdi, G. Ultrasound-assisted extraction of bioactive compounds from pomegranate peel and seed: A comprehensive review of key parameters and optimization strategies. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2026, 124, 107722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, A.; Shah, A.; Bhatt, S.; Bhushan, B.; Kumar, A.; Gaur, R.; Tyagi, I. Ultrasound and microwave assisted extraction of bioactives from food wastes: An overview on their comparative analysis towards commercialization. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2026, 124, 107712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, S.; Xue, T.; Hou, Q.; Wen, L.; Wang, B.; Li, M.; Hu, J.; Yang, J. Ultrasound-assisted extraction and functional characterization of bioactive polysaccharides from Apocynum pictum. Microchemical Journal 2025, 219, 115924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mok, I.-K.; Jung, H.-y.; Kim, H.; Kim, D. Biotransformation of ginsenosides from Korean wild-simulated ginseng (Panax ginseng C. A. Mey.) using the combination of high hydrostatic pressure, enzymatic hydrolysis, and sonication. Food Bioscience 2023, 53, 102687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).