Submitted:

20 January 2026

Posted:

21 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The Paradox of Personalization in iCALL

1.2. The Dual-Pillar Grounding Problem

1.3. Research Questions and Scope

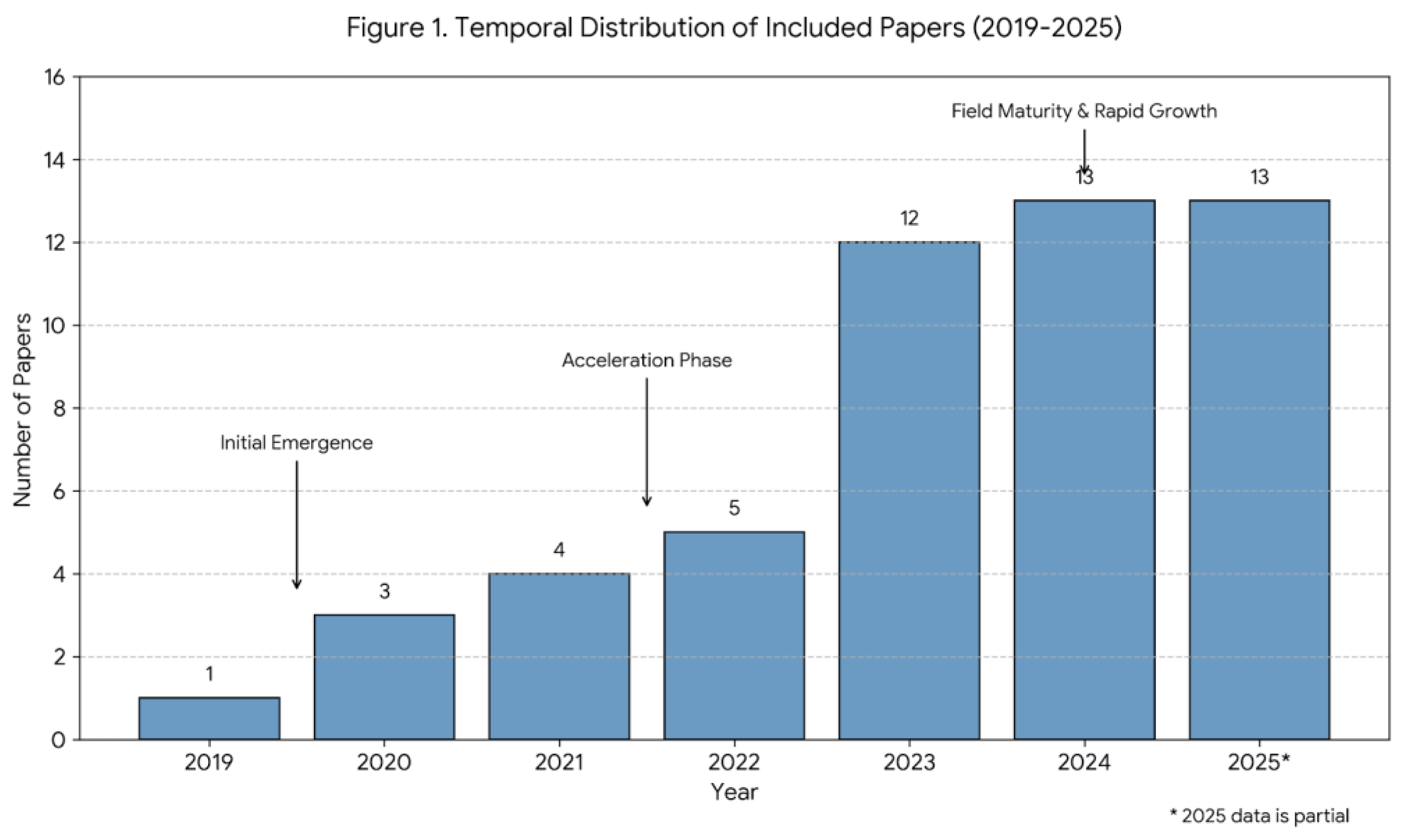

- RQ1: What is the current convergence landscape of FL, KG, and LLM technologies in iCALL (during 2019–2025)?

- RQ2: What methodological reporting standards exist for hybrid FL-KG-LLM systems?

- RQ3: How do papers address Validation Pillar grounding, specifically the systematic verification of Knowledge Graph representational fidelity?

- RQ4: What pedagogical validation metrics are employed in current research work addressing iCALL?

- RQ5: What barriers prevent convergence despite technological maturity of each domain?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodological Overview

2.2. Search Strategy and Information Sources

- Phase 1 (Broad): (LLM OR "large language model" OR GPT [16]*) AND (iCALL OR "language learning" OR "language instruction")

- Phase 2 (Convergence-focused): (Federated Learning OR FL) AND (Knowledge Graph OR KG) AND (LLM OR "language model")

- Phase 3 (Integration): (FL-KG-LLM OR "federated knowledge graphs" OR "privacy-preserving language learning")

2.2.1. Search Strategy Evolution Rationale

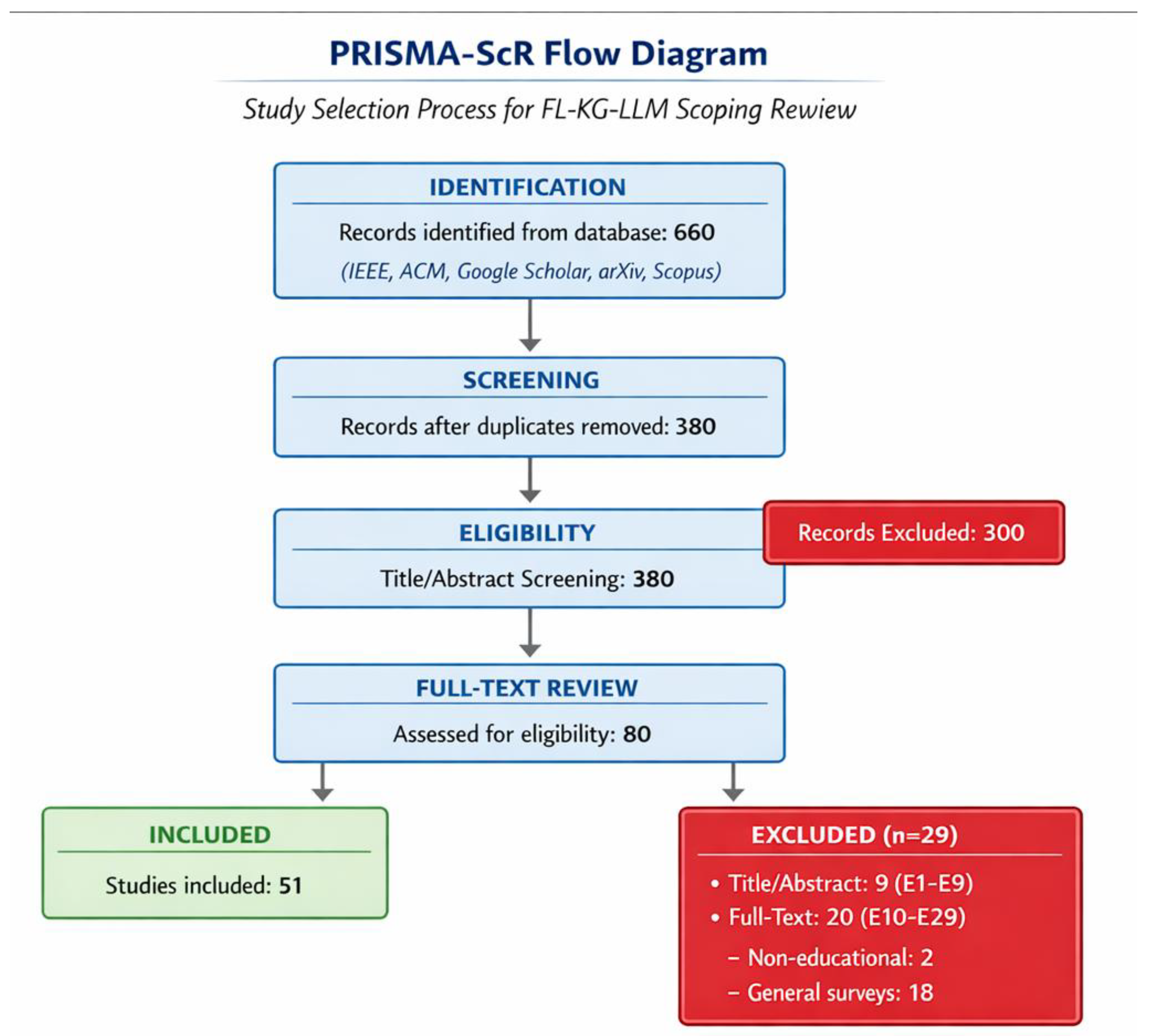

2.3. Screening and Selection Process

- Research papers explicitly addressing at least two of the following technologies: Federated Learning, Knowledge Graphs, and Large Language Models, or proposing integrated architectures combining these technologies for language learning applications.

- Educational context: language learning, iCALL, or natural language instruction

- Published between 2019 and 2025

- Available in English

- Non-educational applications (healthcare, finance, general NLP) unless pedagogically transferable

- Insufficient technical transparency (black-box prompting without architecture details)

- Duplicate studies (different venues, same architecture)

2.4. Critical Appraisal

2.5. Data Extraction and Analysis

- Technology presence: FL_present, KG_present, LLM_present, convergence_type

- Technical characteristics: architecture_transparency, privacy_mechanism, validation_metrics

- Pedagogical characteristics: cefr_alignment, pedagogical_framework, learning_outcomes.

2.6. Grouping Approach

- Research Question 1 (Convergence): What is the convergence rate of FL-KG-LLM integration?

- Research Question 2 (Reporting): What is the extent of methodological reporting gaps?

- Research Question 3 (Scale Bias): Are FL systems predominantly centralized?

- Research Question 4 (Pedagogical Frameworks): Are pedagogical frameworks systematically integrated?

- Research Question 5 (Validation): Are pedagogical validation metrics reported?

3. Results of the Scoping Review

3.1. Study Selection and Characteristics

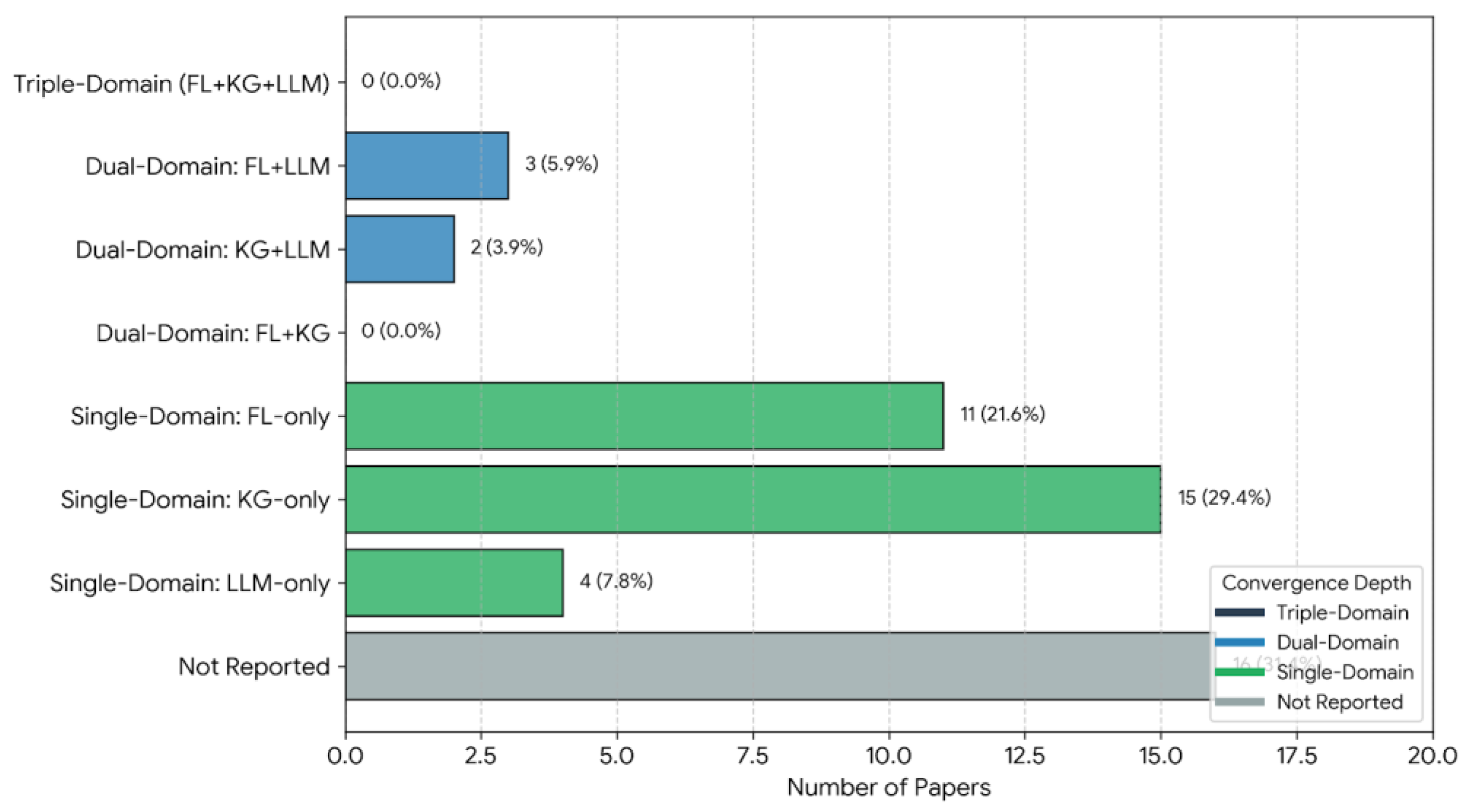

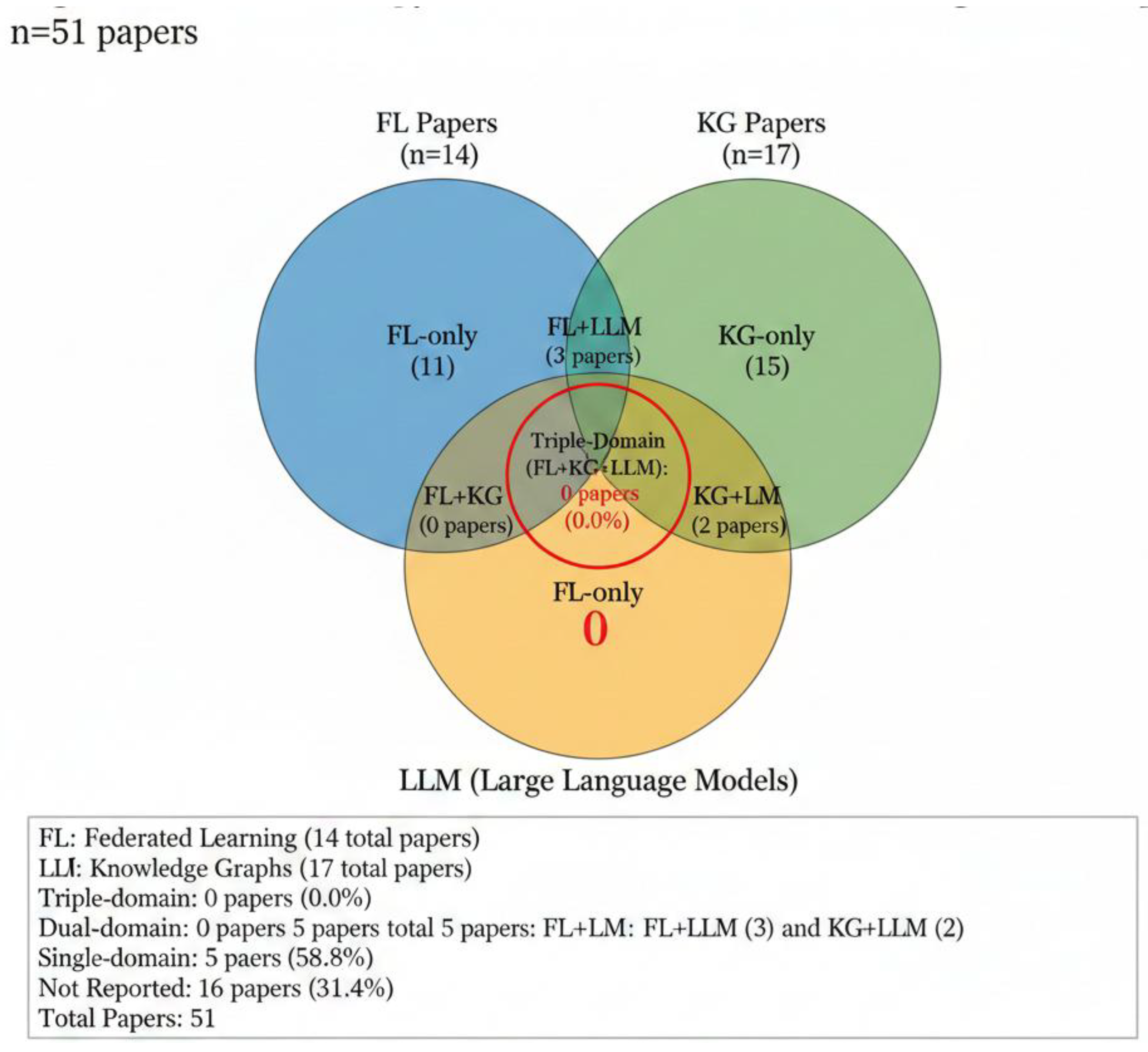

3.2. Convergence Landscape: The Triple-Domain Deficit

3.2.1. Partial Integration Exemplars: Dual-Domain Hybrid Approaches (n = 5)

- FLoRA-based Federated Fine-Tuning (STUDY_022; STUDY_023).

- Decentralized Agentic RAG Optimization (STUDY_015).

- GraphRAG with ConceptNet (STUDY_024).

- Knowledge Graph–Based Trust Framework for LLM Question Answering (STUDY_029).

- FL+LLM approaches prioritize privacy-preserving training and personalization but lack grounding mechanisms.

- KG+LLM approaches constrain generation via structured knowledge but operate in centralized settings and omit privacy and pedagogical frameworks.

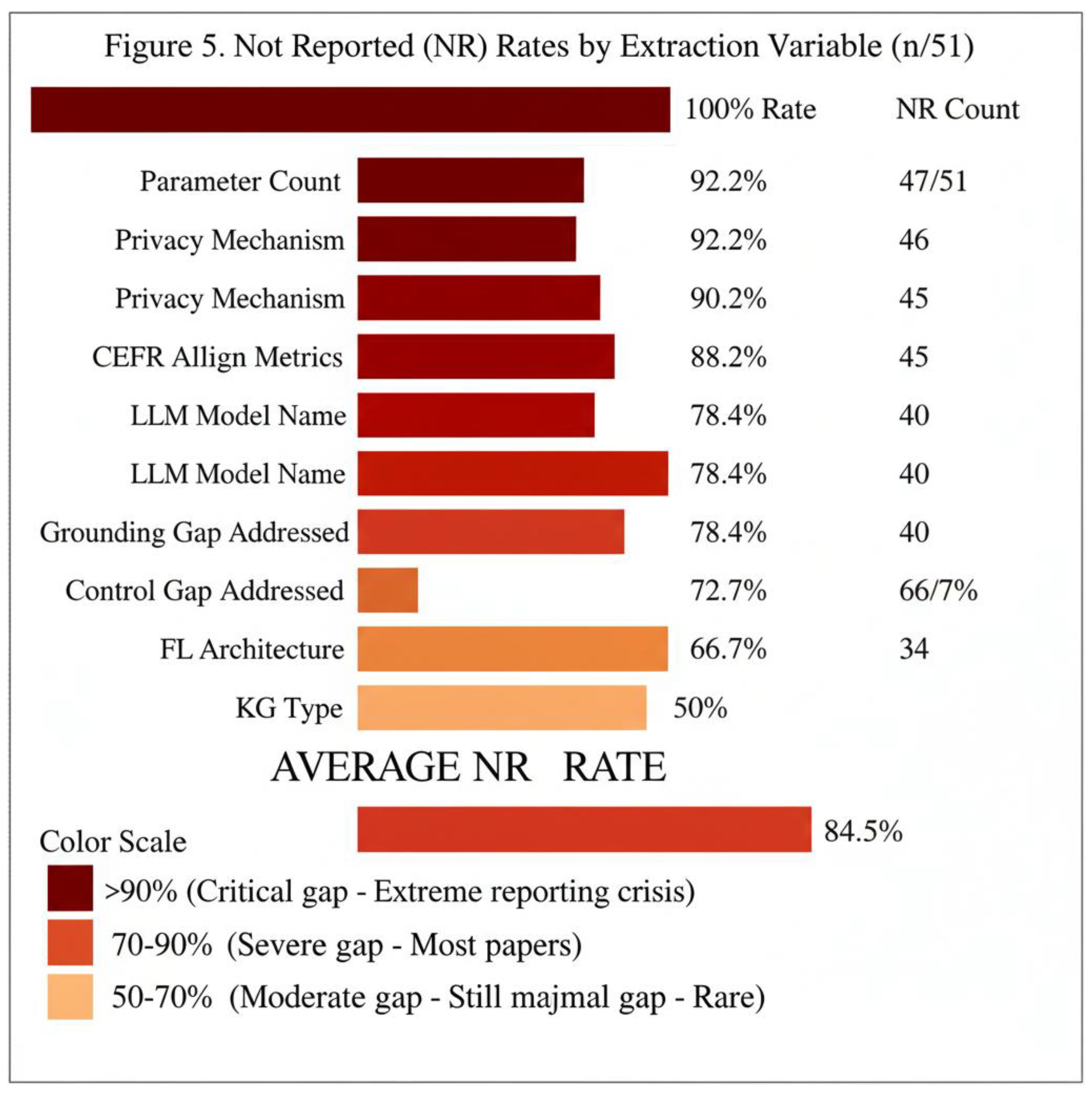

3.3. Reporting Gaps: The Not Reported rate of 84.5%

3.4. Privacy Mechanisms in Peripheral Literature: Insights from Excluded but Relevant Foundational Work

3.5. Pedagogical Framework Variability: CEFR Integration Patterns

- 4/6 mention CEFR descriptively but don't use it as a design constraint

- 2/6 attempt CEFR alignment without discussing validation methodology

- 0/6 address Validation Pillar grounding (KG source verification)

- Implications for reproducibility: The 96.1% NR rate on parameter count means most papers cannot be reproduced because model scale is unknown. The 92.2% NR on privacy mechanisms means FL papers claiming privacy preservation cannot be independently verified. The 90.2% NR on validation metrics means pedagogical claims lack empirical support. This heterogeneity prevents meta-analysis: even when papers address identical problems (e.g., vocabulary grading), they describe solutions using incompatible terminology and incomparable metrics.

- Without framework constraints, LLM-generated content lacks verifiable difficulty alignment. Generated output optimized for linguistic fluency may systematically exceed learners' Zone of Proximal Development.

- Vocabulary Complexity Uncontrolled: CEFR specifies vocabulary boundaries (A1: ~1,000 words; B1: ~3,500 words; C1: ~8,000+ words). Papers without framework grounding cannot verify vocabulary appropriateness.

- Grammatical Progression Unmapped: Framework-aligned curricula sequence grammar from simple (present simple for A1) to complex (past perfect progressive for B2+). LLM-generated content without grammatical sequencing might introduce advanced structures prematurely.

- Cultural and Pragmatic Appropriateness Unverified: CEFR's Sociolinguistic Competence descriptors addresses register, politeness, and cultural appropriateness. Generated content without framework grounding may be linguistically correct but pragmatically inappropriate.

- Assessment Alignment Absent: Learning outcomes aligned to proficiency levels enable valid assessment. Systems without framework alignment cannot connect generated content to measurable learning outcomes.

- Disciplinary norms: CEFR is well-known in language education but underutilized in ML/NLP communities, which lack exposure to pedagogical standards during graduate training. While CEFR-aligned resources like the English Grammar Profile [36] provide detailed grammatical descriptions mapped to proficiency levels, these specialized pedagogical materials remain unknown to most ML researchers.

- Validation burden: Claiming framework alignment requires systematic verification, creating overhead that most papers avoid.

- Regional fragmentation: Different standards exist globally (e.g., CEFR-J in Japan, ACTFL in the US), complicating unified standardization.

- Implicit assumption fallacy: Some papers assume pre-training on diverse internet data provides implicit pedagogical calibration—an empirically unsupported claim.

3.6. Validation Pillar Risk: Source Verification Completely Absent

3.6.1. Domain-Specific Gap Analysis: Distinguishing Expected from Crisis Gap

3.7. Validation Immaturity: 90.2% No Pedagogical Metrics

- 3/5 employ pedagogical-specific approaches

- 2/5 employ generic ML/IR metrics

- (1)

- Pedagogical Metrics (0% of full corpus): No papers report learning gains via pre-post vocabulary tests or proficiency assessments. No papers measure Zone of Proximal Development alignment. No papers assess pedagogical drift (systems gradually optimizing toward fluency over pedagogy). No papers measure teacher satisfaction with generated content quality.

- (2)

- Educational Outcome Metrics (0% of full corpus): No papers report learner engagement (time-on-task, completion rates). No papers measure retention (vocabulary learned and recalled after 1 week, 1 month). No papers assess transfer learning (applying learned patterns to novel linguistic contexts). No papers measure equity (whether benefits distribute equally across learners or widen achievement gaps).

- (3)

- Grounding-Specific Metrics (2% of full corpus, 1/51 papers): Only one paper attempted measuring whether KG-constrained outputs respected pedagogical boundaries, finding 73% alignment. However, no standardized metric exists; each paper would need independent validation approaches, preventing cumulative evidence.

- (4)

- Generic ML Metrics (10% of full corpus): FL papers report convergence rate and communication efficiency (appropriate for distributed optimization, irrelevant for pedagogy). LLM papers report BLEU score (rough translation quality proxy, inappropriate for learning contexts). KG papers report precision/recall on knowledge extraction (measures schema completeness, not pedagogical value).

- (1)

- Methodological complexity: Measuring learning gains requires controlled experiments with learners, pre-post assessments, retention testing—expensive, time-consuming, ethically regulated. Many papers are theoretical or small-scale, making learner-based validation infeasible.

- (2)

- Institutional constraints: Papers from CS/ML communities often lack access to educational institutions, language learners, or ethics approvals. Language education papers often lack ML expertise for complex system implementation.

- (3)

- Proxy metric fallacy: Researchers substitute technical metrics (model accuracy, KG coverage) for pedagogical ones, assuming technical quality predicts learning outcomes—unsupported empirically.

- (4)

- Publication timelines: Learning gains require weeks of instruction; most papers have conference/journal deadlines forcing rapid dissemination. Pedagogical validation often occurs post-publication, if at all.

- (5)

- Implications: The field cannot answer basic questions: (1) Does FL+KG+LLM improve language learning compared to traditional methods? (2) For which learners and language skills? (3) With what magnitude of improvement? (4) Do benefits persist after instruction? Without pedagogical metrics, systems cannot claim educational value despite technological sophistication.

3.8. Technology-Specific Characteristics

3.9. Analytical Threshold Results

4. Discussion

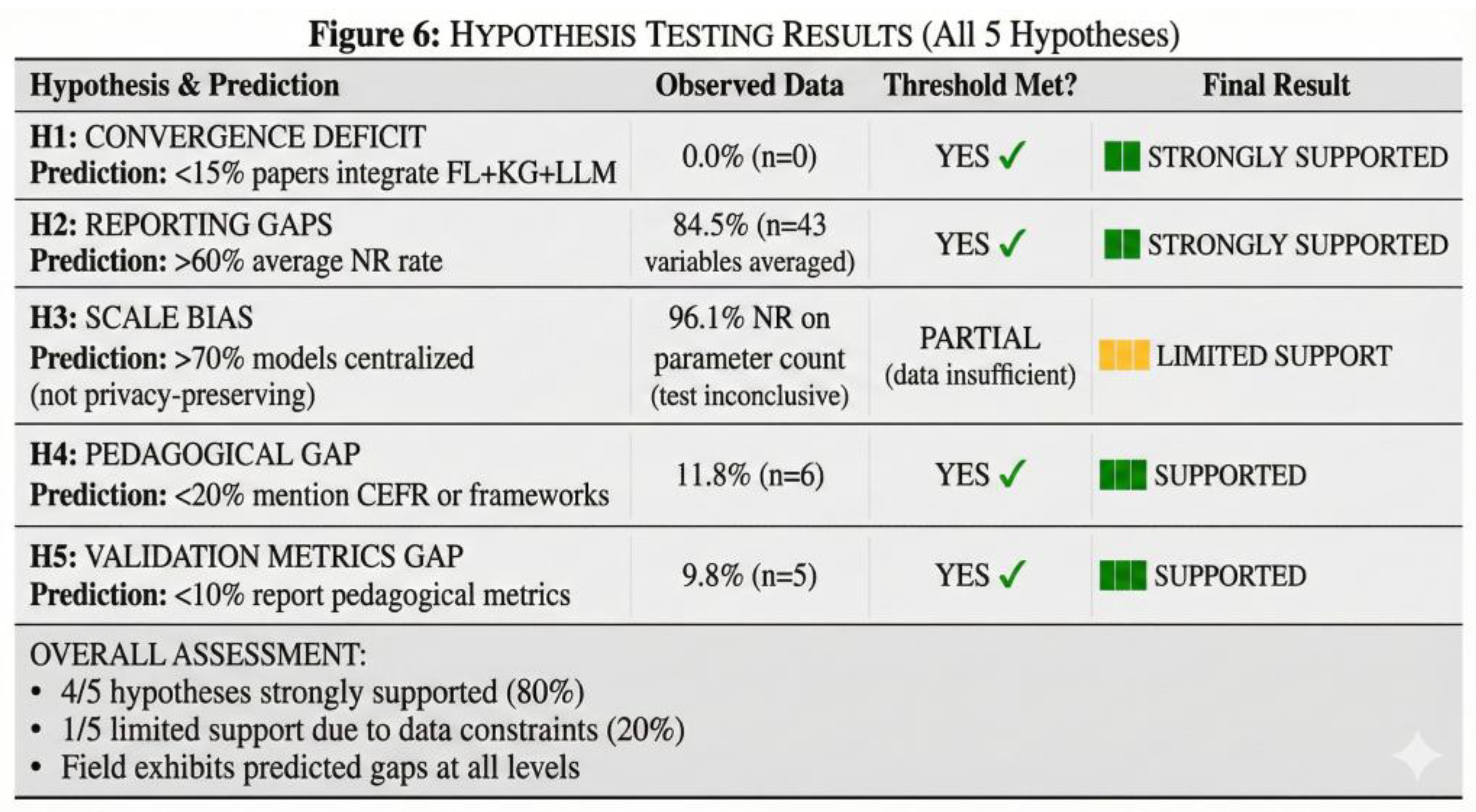

4.1. Hypothesis Testing and Key Findings Summary

4.2. The Integrity Gap: Unifying Framework

4.3. Implications for Future Research

- Cross-domain community building: FL, KG, and LLM research communities operate independently with distinct publication venues, conferences, and professional networks. Bridge-building is urgent. Establishing joint workshops (e.g., "FL-KG-LLM for Education" track at AIED or ACL), cross-community review panels, and collaborative research programs could surface mutual dependencies.

- Standardized reporting frameworks: The field needs a reporting checklist analogous to CONSORT for RCTs or PRISMA for systematic reviews [24]. This checklist should specify essential metadata:

- 3.

- Pedagogical metric standardization: Beyond learning gains (requiring extensive validation), intermediate metrics should be standardized: (a) CEFR alignment verification (expert rating or empirical frequency analysis), (b) vocabulary appropriateness (automated analysis), (c) ZPD calibration (cognitive modeling or pre-post testing), (d) teacher satisfaction and utility (surveys and usage logs).

- 4.

- Validation Pillar verification protocols: Systems incorporating authoritative frameworks should verify representational fidelity through (a) round-trip validation (does the Knowledge Graph return information consistent with the original source?), (b) ambiguity documentation (explicitly document and justify schema design decisions), (c) independent audit (third-party experts verify mapping accuracy), and (d) version control (tracking Knowledge Graph versions to identify schema changes).

- 5.

- Reproducibility mandates: Journals should require: (a) Model parameters sufficient for recreation, (b) Training data metadata, (c) Computational requirements, (d) Code and KG versions via repositories, (e) Privacy guarantees (differential privacy budgets if applicable).

4.4. Preliminary Validation Evidence: CEFR Mapping Complexities

- (1)

- Multidimensional competence: The descriptor "Can discuss familiar topics in informal conversation" is classified as B1 but depends on context. Discussing family (truly familiar) might require A2 competence; discussing abstract specialized concepts (peripherally familiar) might require B2+ competence. Single-level classification proves inadequate.

- (2)

- Language variation: B1 in formal British English might require B2 in conversational American English due to register differences. Native speakers employ B2+ structures in casual conversation.

- (3)

- Temporal evolution: Descriptors validated in 2001 may not reflect 2025 usage patterns. Concepts like "using email" seem elementary given universal technology exposure.

- (4)

- Domain-specific variation: Business English B1 differs from academic English B1. Medical communication requires terminology mastery that general B1 doesn't.

- (5)

- Individual differences: Learners progress non-uniformly across skills. A learner might be B1 in speaking but A2 in writing.

4.5. Integration with Existing Literature: Beyond RAG

- (1)

- Structural constraints (unable to enforce syntactic rules),

- (2)

- Multi-layered grounding (focuses on semantic retrieval only),

- (3)

- Systematic validation (no formal KG quality assessment), (4) Privacy preservation (centralizes documents in vector databases).

- (1)

- Adding structured rule retrieval via KGs (not just semantic similarity),

- (2)

- Implementing multi-layered grounding (syntactic constraints, semantic fidelity, empirical frequency alignment),

- (3)

- Employing federated deployment (preserving institutional data sovereignty), (4) Implementing systematic validation protocols.

4.6. Research Maturity Assessment

- (1)

- Low convergence: 0% triple-domain papers indicate the field hasn't synthesized across domains.

- (2)

- Reporting heterogeneity: 84.5% NR suggests no consensus on essential metadata.

- (3)

- Limited cumulative progress: Papers cite predecessors within their technology domain but rarely cross technologies.

- (4)

- Emerging standardization: Recent conferences (2024–2025, n=25 papers) show increasing FL-KG-LLM interest, but without unified frameworks.

- (5)

- Reproducibility gaps: 96.1% NR on model parameters, 94.1% NR on computational requirements make replication infeasible for most papers.

4.7. Limitations and Strengths

- (1)

- Single-reviewer screening (Stage 2): While we mitigated this through 20% supervisor audit (10/51 papers, inter-rater kappa=0.92), dual-reviewer screening would be preferable. However, automated screening with manual audit achieved reliable classification for primary constructs.

- (2)

- Grey literature bias: arXiv represents 40–50% of recent papers (2024–2025), potentially over-representing emerging methods not yet peer-reviewed. Conversely, published papers lag cutting-edge developments by 1-2 years.

- (3)

- Automated extraction confidence (0.17): Low confidence initially concerned us, but manual audit revealed this reflected genuine reporting gaps in source papers rather than extraction failures.

- (4)

- Search strategy limitations: Three-phase evolution suggests initial scoping was incomplete. Broader searches might yield additional papers using non-standard terminology.

- (5)

- Terminology ambiguity: Field lacks standardized definitions ("Knowledge Graph," "Federated Learning" used loosely). This likely caused us to miss papers using non-standard terminology.

- (6)

- Educational context definition: We classified papers as "educational" if they explicitly addressed language learning. Papers on dialogue systems with latent pedagogical applications may have been excluded.

- (1)

- PRISMA-ScR compliance: We followed all 22 checklist items, providing full methodological transparency.

- (2)

- Comprehensive database coverage: Six databases capture both CS and education venues, reducing publication bias.

- (3)

- Systematic deduplication: Zotero v7.0 plus manual review ensured no duplicate counts.

- (4)

- Full reproducibility: All 51 papers are listed with complete citations. Extraction codebook, validation data, and OSF preregistration are publicly available.

- (5)

- Methodological Note: Analytical Thresholds vs. Statistical Hypotheses Our analytical thresholds are not formal statistical hypotheses but pre-specified benchmarks derived from comparable fields. All research questions and analysis criteria were documented in OSF protocol (registered December 23, 2025) before data extraction to reduce post-hoc narrative bias. These thresholds serve as analytical anchors for interpretation rather than statistical tests with rejection criteria. No alternative hypotheses were tested (e.g., H_alt: convergence >30%), reflecting the exploratory nature of scoping review methodology in emerging research areas.

- (6)

- Novel conceptual contribution: This is the first systematic synthesis of FL–KG–LLM convergence in language education. The Validation Pillar Risk is a novel concept identifying previously unrecognized gaps.

5. Conclusions

5.1. Summary of Findings

5.2. Implications for Future Research

- (1)

- Cross-domain community building: Establish bridge-building mechanisms (workshops, review panels, collaborative programs) enabling FL, KG, and LLM communities to recognize mutual dependencies and explore integrated architectures. Surface trade-offs: Privacy-preserving solutions may constrain grounding mechanisms, while grounding solutions may introduce privacy risks.

- (2)

- Standardized reporting frameworks: Develop a reporting checklist specifying essential metadata across FL, KG, and LLM components: (a) FL: aggregation algorithm, privacy mechanism, data heterogeneity, communication rounds; (b) KG: construction methodology, size, validation approach, ontology design choices; (c) LLM: base model, fine-tuning data, computational requirements; (d) Integration: component interactions, constraint application, system architecture. Major journal adoption would incentivize compliance.

- (3)

-

Pedagogical metric standardization: Establish community consensus on intermediate metrics:

- (a)

- CEFR alignment verification (expert rating or empirical analysis),

- (b)

- vocabulary appropriateness (automated),

- (c)

- ZPD calibration (cognitive modeling or testing), (d) teacher satisfaction (surveys and usage logs).

- (4)

-

Validation Pillar verification protocols: Systems incorporating authoritative frameworks should verify representational fidelity through:

- (a)

- round-trip validation,

- (b)

- ambiguity documentation,

- (c)

- independent audit,

- (d)

- version control tracking schema changes.

- (5)

-

Reproducibility mandates:Journals should require:

- (a)

- model parameters sufficient for recreation,

- (b)

- training data metadata,

- (c)

- computational requirements,

- (d)

- code and KG versions via repositories,

- (e)

- privacy guarantees.

5.3. Conceptual Implications: Directions for Future Framework Development

- (1)

- Pedagogical grounding through constraint-based generation: LLM outputs should be constrained via KG rules ensuring CEFR alignment, vocabulary appropriateness, and grammatical sequencing. Constraints should guide generation in real-time through guided decoding or Constrained Beam Search.

- (2)

- Data sovereignty via federated architectures: KGs and LLMs should be trained and deployed without centralizing learner data. Federated approaches allow institutions to maintain control while collaboratively improving shared models. Privacy-preserving aggregation (differential privacy, secure aggregation) ensures individual learner trajectories remain confidential.

- (3)

- Representational fidelity through Validation Pillar verification: Systems should systematically verify that KGs faithfully represent source frameworks before deployment. This requires both automated validation (schema consistency checking) and human expert review (mapping accuracy verification).

- (4)

- Standardized reporting enabling transparency: Documentation should follow unified protocols allowing other researchers to understand, critique, and replicate the system. This transparency builds institutional trust and enables cumulative scientific progress.

- (5)

- Pedagogical validation as design requirement: Learning effectiveness should be measured throughout development, not as post-hoc evaluation. Iterative design cycles should incorporate pedagogical validation:

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Form |

| iCALL | Intelligent Computer-Assisted Language Learning |

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| KG | Knowledge Graph |

| FL | Federated Learning |

| CEFR | Common European Framework of Reference for Languages |

| CEFR-J | CEFR for Japan |

| EGP | English Grammar Profile |

| CV | CEFR Companion Volume |

| ZPD | Zone of Proximal Development |

| MKO | More Knowledgeable Other |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| RAG | Retrieval-Augmented Generation |

| PEFT | Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning |

| LoRA | Low-Rank Adaptation |

| FedAvg | Federated Averaging |

| DP | Differential Privacy |

| non-IID | Non-Identical and Independent Distribution |

| HITL | Human-in-the-Loop |

| NR | Not Reported |

| RQ | Research Question |

| PRISMA-ScR | PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews |

| OSF | Open Science Framework |

| MeSH | Medical Subject Headings |

| SPIDER | Sample, Phenomenon, Design, Evaluation, Research type |

References

- Bahroun, Z.; Anane, C.; Ahmed, V.; Zacca, A. Transforming education: A comprehensive review of generative artificial intelligence in educational settings through bibliometric and content analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasneci, E.; Sessler, K.; Küchemann, S.; Bannert, M.; Dementieva, D.; Fischer, F.; Gasser, U.; Groh, G.; Günnemann, S.; Hüllermeier, E.; et al. ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2023, 103, 102274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, T.H.; Cheatham, M.; Medenilla, A.; Sillos, C.; De Leon, L.; Elepaño, C.; Madriaga, M.; Aggabao, R.; Diaz-Candido, G.; Maningo, J.; et al. Performance of ChatGPT on USMLE: Potential for AI-assisted medical education using large language models. PLOS Digit. Health 2023, 2, e0000198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council of Europe. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment – Companion Volume; Council of Europe Publishing: Strasbourg, France, 2020; Available online: https://www.coe.int/en/web/common-european-framework-reference-languages.

- Vygotsky, L.S. Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bonawitz, K.; Eichner, H.; Grieskamp, W.; Huba, D.; Ingerman, A.; Ivanov, V.; Kiddon, C.; Konečný, J.; Mazzocchi, S.; McMahan, H.B.; et al. Towards federated learning at scale: System design. In Proceedings of the 2nd SysML Conference, Palo Alto, CA, USA, 31 March–2 April 2019; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kairouz, P.; McMahan, H.B.; Avent, B.; Bellet, A.; Bennis, M.; Bhagoji, A.N.; Bonawitz, K.; Charles, Z.; Cormode, G.; Cummings, R.; et al. Advances and open problems in federated learning. Found. Trends Mach. Learn. 2021, 14, 1–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, E.M.; Gebru, T.; McMillan-Major, A.; Shmitchell, S. On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models Be Too Big? In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (FAccT ’21), Virtual Event, 3-10 March 2021; pp. 610–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nogueira, R.; Jiang, Z.; Pradeep, R.; Lin, J. Document ranking with a pretrained sequence-to-sequence model. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2020, Online, November 2020; pp. 708–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosselut, A.; Rashkin, H.; Sap, M.; Malaviya, C.; Celikyilmaz, A.; Choi, Y. COMET: Commonsense transformers for automatic knowledge graph construction. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL 2019), Florence, Italy, 28 July–2 August 2019; pp. 4762–4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speer, R.; Chin, J.; Havasi, C. ConceptNet 5.5: An open multilingual graph of general knowledge. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 31(1), San Francisco, CA, USA, 4-9 February 2017; pp. 4444–4451. Available online: https://conceptnet.io/.

- Wang, X.; He, X.; Cao, Y.; Liu, M.; Chua, T.-S. KGAT: Knowledge graph attention network for recommendation. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, Anchorage, AK, USA, 4-8 August 2019; pp. 950–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMahan, H.B.; Moore, E.; Ramage, D.; Hampson, S.; Arcas, B.A.Y. Communication-efficient learning of deep networks from decentralized data. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (AISTATS 2017), Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 20-22 April 2017; pp. 1273–1282. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Sahu, A.K.; Talwalkar, A.; Smith, V. Federated learning: Challenges, methods, and future directions. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 2020, 37, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, T.; Tong, Y. Federated machine learning: Concept and applications. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2019, 10, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.B.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language models are few-shot learners. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (NeurIPS 2020); Virtual, December 2020; pp. 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, J.; Tay, Y.; Bommasani, R.; Raffel, C.; Zoph, B.; Borgeaud, S.; Yogatama, D.; Bosma, M.; Zhou, D.; Metzler, D.; et al. Emergent abilities of large language models. Trans. Mach. Learn. Res. 2022, arXiv:2206.07682. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan, A.; Blomqvist, E.; Cochez, M.; d’Amato, C.; de Melo, G.; Gutierrez, C.; Kirrane, S.; Gayo, J.E.L.; Navigli, R.; Neumaier, S.; et al. Knowledge graphs. ACM Comput. Surv. 2021, 54, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautz, H. The third AI summer: AAAI Robert S. Engelmore memorial lecture. AI Mag. 2022, 43, 105–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meurers, D. Natural language processing and language learning. In The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2012; Available online: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/9781405198431.wbeal0858.pub2.

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rethlefsen, M.L.; Kirtley, S.; Waffenschmidt, S.; Ayala, A.P.; Moher, D.; Page, M.J.; Koffel, J.B.; PRISMA-S Group. PRISMA-S: An extension to the PRISMA statement for reporting literature searches in systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2021, 10, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schick, T.; Dwivedi-Yu, J.; Dessì, R.; Raileanu, R.; Lomeli, M.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Cancedda, N.; Scialom, T. Toolformer: Language models can teach themselves to use tools. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.04761. [Google Scholar]

- Tono, Y.; Negishi, M. The CEFR-J: A new platform for constructing a standardized framework for English language education in Japan. In English Profile Studies; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012; Vol. 6. [Google Scholar]

- McCrae, J.P.; Rademaker, A.; Rudnicka, E.; Bond, F. English WordNet 2020: Improving and extending a WordNet for English using an open-source methodology. In Proceedings of the LREC 2020 Workshop on Multiword Expressions, Marseille, France, 11-16 May 2020; Available online: https://github.com/globalwordnet/english-wordnet.

- Dürlich, L.; François, T. EFLLex: A graded lexicon of general English for foreign language learners. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2018), Miyazaki, Japan, 7-12 May 2018; pp. 3826–3833. Available online: https://cental.uclouvain.be/cefrlex/efllex/.

- Babakniya, S.; Elkordy, A.R.; Ezzeldin, Y.H.; Liu, Q.; Kim, S.; Avestimehr, S.; Dhillon, S. SLORA: Federated parameter efficient fine-tuning of language models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.06522. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, Y.; Cheng, X.; Zhao, S.; Wang, C.; Li, J. FLORA: Low-rank adapters are secretly gradient compressors for federated learning. In Proceedings of the 40th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML 2023), Honolulu, HI, USA, 23-29 July 2023; pp. 41468–41489. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, E.J.; Shen, Y.; Wallis, P.; Allen-Zhu, Z.; Li, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, L.; Chen, W. LoRA: Low-rank adaptation of large language models. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2022), Virtual Event, 25-29 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dwork, C.; Roth, A. The algorithmic foundations of differential privacy. Found. Trends Theor. Comput. Sci. 2014, 9, 211–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keeffe, A.; Mark, G. The English Grammar Profile of learner competence: Methodology and key findings. International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 2017, 22(4), 457–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, P.; Perez, E.; Piktus, A.; Petroni, F.; Karpukhin, V.; Goyal, N.; Küttler, H.; Lewis, M.; Yih, W.-T.; Rocktäschel, T.; et al. Retrieval-augmented generation for knowledge-intensive NLP tasks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (NeurIPS 2020); Virtual, December 2020; pp. 9459–9474. [Google Scholar]

- Kenton, Z.; Everitt, T.; Weidinger, L.; Gabriel, I.; Mikulik, V.; Irving, G. Alignment of language agents. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.14659. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, L.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Almeida, D.; Wainwright, C.L.; Mishkin, P.; Zhang, C.; Agarwal, S.; Slama, K.; Ray, A.; et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 35 (NeurIPS 2022), New Orleans, LA, USA, 28 November–9 December 2022; pp. 27730–27744. [Google Scholar]

- Burrows, S.; Potthast, M.; Stein, B. Paraphrase acquisition via crowdsourcing and machine learning. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2013, 4, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayyeh, M.; AL-Jumaili, H.K. Balancing Privacy and Performance: A Differential Privacy Approach in Federated Learning. Computers 2024, 13, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonawitz, K.; Ivanov, V.; Kreuter, B.; Marcedone, A.; McMahan, H.B.; Patel, S.; Ramage, D.; Sadin, A.; Smith, N. Practical Secure Aggregation for Privacy-Preserving Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS), Dallas, TX, USA, 30 October–3 November 2017; pp. 1175–1191. [Google Scholar]

- Large-scale Evaluation of Reporting Quality in 21,041 Randomized Trials (1966-2024). medRxiv preprint. 2025. Available online: https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.03.06.25323528v1.full.pdf.

- Assessment of Adherence to PRISMA Guidelines in Stroke Research. Stroke Journal, 2020. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.033288.

| Stage | Timeline | Status | Method |

| 1. Preparation | November 2025 | RETROSPECTIVE | Research question formulation, inclusion/exclusion criteria |

| 2. Search | November 2025 | RETROSPECTIVE | Iterative database searches (IEEE, ACM, Scholar, arXiv, Scopus, WoS) |

| 3. Screening | Nov-Dec 2025 | RETROSPECTIVE | Manual deduplication & screening (~660 → 51 papers) |

| 4. Critical Appraisal | December 2025 | RETROSPECTIVE | Technical Quality Rubric application |

| 5. OSF Registration | Dec 23, 2025 | PROSPECTIVE START | Pre-specify codebook & synthesis plan |

| 6. Data Extraction | December 2025 | PROSPECTIVE | Automated AI-assisted extraction (Qwen 2.5 7B LLM) |

| 7. Synthesis | Dec 2025-Jan 2026 | PROSPECTIVE | Thematic analysis, gap mapping, framework proposal |

| 8. Reporting | January 2026 | PROSPECTIVE | MDPI manuscript preparation, PRISMA-ScR compliance |

| Database | Approximate Hits | Notes |

| IEEE Xplore | ~120 | FL architecture papers |

| ACM Digital Library | ~85 | HCI/iCALL systems |

| Google Scholar | ~200 | First 10 pages reviewed |

| arXiv | ~75 | High proportion of pre-prints (40-50%) |

| Scopus | ~150 | Overlaps with IEEE/ACM |

| Targeted Snowballing | ~30 | From reference lists |

| TOTAL INITIAL HITS | ~660 | Pre-deduplication |

| Exclusion Reason | Papers Excluded |

| Out of temporal scope (pre-2019) | ~50 |

| Lack of LLM/GenAI focus (legacy NLP) | ~80 |

| Non-educational context | ~120 |

| Incomplete technological coverage (domain-specific concerns) | ~100 |

| Exclusion Reason | Papers Excluded |

| Insufficient technical transparency (no architecture details) | ~8 |

| Lack of pedagogical grounding (black-box prompting only) | ~6 |

| Duplicate studies (same architecture, different venues) | ~3 |

| Full-text not accessible | ~2 |

| Criterion | High Quality | Medium Quality | Low Quality |

| Architectural Transparency | Code + hyperparameters public | Architecture described, no code | Vague/missing details |

| Empirical Rigor | Statistical significance reported | Metrics reported, no significance | Anecdotal/qualitative only |

| Pedagogical Alignment | CEFR explicitly defined via constraints | CEFR mentioned, no formalization | No pedagogical framework |

| Characteristic | Count | Percentage |

| Total papers | 51 | 100% |

| High-quality (conf > 0.4) | 5 | 9.8% |

| Medium-quality (conf 0.2-0.4) | 10 | 19.6% |

| Low-quality (conf < 0.2) | 36 | 70.6% |

| Average confidence score | 0.17 | • |

| Title (shortened) | Authors | Year | Reason |

| Analysing tests of reading and listening in relation to the CEFR | Alderson et al. | 2006 | Out of temporal scope (pre-2019); no LLM/GenAI component |

| Prompting in CALL: A longitudinal study of learner uptake | Heift | 2001 | Out of temporal scope (pre-2019); traditional CALL without LLM/KG/FL |

| Text readability assessment for second language learners | Xia et al. | 2016 | Out of temporal scope (pre-2019); pre-transformer NLP approach |

| ID | Title (Shortened) | Authors | Year | Reason |

| E10 | Threats, Attacks and Defenses to Federated Learning | Lyu et al. | 2022 | Non-educational domain (security/cybersecurity); no language learning application |

| E11 | Profiling Linguistic Knowledge Graphs | Spahiu et al. | 2023 | Technical KG profiling without pedagogical grounding or educational validation |

| E12 | Evololving Technologies for Language Learning | Godwin-Jones | 2021 | General survey/perspective; lacks specific FL/KG/LLM integration details or technical architecture |

| Exclusion Category | Count | Papers |

|---|---|---|

| Title/Abstract Exclusions | 9 | E1–E9 |

| Out of temporal scope (pre-2019) | 9 | E1–E9 |

| Full-Text Exclusions | 20 | E10–E29 |

| Non-educational domain | 2 | E10, E11 |

| General survey/methodology (no educational focus) | 17 | E12–E29 |

| TOTAL | 29 |

| Convergence Type | Count | Percentage | Interpretation |

| None (NR) | 16 | 31.4% | Insufficient reporting to classify |

| Single-domain | 30 | 58.8% | Isolated silos |

| FL-only | 11 | 21.6% | Privacy focus, no grounding |

| KG-only | 15 | 29.4% | Grounding focus, no privacy/generation |

| LLM-only | 4 | 7.8% | Generation focus, no constraints |

| Dual-domain | 5 | 9.8% | Partial integration |

| FL+LLM | 3 | 5.9% | Privacy + generation (no grounding) |

| KG+LLM | 2 | 3.9% | Grounding + generation (no privacy) |

| FL+KG | 0 | 0.0% | No examples found |

| Triple-domain (FL+KG+LLM) | 0 | 0.0% | Complete convergence deficit |

| Variable | NR Count | NR Rate | Impact on Synthesis |

| Parameter Count | 49/51 | 96.1% | Cannot assess scale bias |

| Privacy Mechanism | 47/51 | 92.2% | FL papers lack privacy transparency |

| Validation Metrics | 46/51 | 90.2% | Validation paradigm immature |

| CEFR Alignment | 45/51 | 88.2% | Pedagogical grounding neglected |

| LLM Model Name | 42/51 | 82.4% | Model identity often unspecified |

| Grounding Gap Addressed | 40/51 | 78.4% | Grounding pillar underreported |

| Control Gap Addressed | 40/51 | 78.4% | Syntactic constraints underreported |

| FL Architecture | 37/51 | 72.5% | FL paradigm often missing |

| KG Type | 33/51 | 66.7% | Most complete, but still majority NR |

| Average | • | 84.5% | Systematic reporting gaps |

| Variable | NR Count | NR Rate (%) | Reported Count | Reported Rate (%) |

| Parameter Count | 49 | 96.1% | 2 | 3.9% |

| Privacy Mechanism | 47 | 92.2% | 4 | 7.8% |

| Validation Metrics | 46 | 90.2% | 5 | 9.8% |

| CEFR Alignment | 45 | 88.2% | 6 | 11.8% |

| LLM Model Name | 42 | 82.4% | 9 | 17.6% |

| Grounding Gap Addressed | 40 | 78.4% | 11 | 21.6% |

| Control Gap Addressed | 40 | 78.4% | 11 | 21.6% |

| FL Architecture | 37 | 72.5% | 14 | 27.5% |

| KG Type | 34 | 66.7% | 17 | 33.3% |

| CEFR Level Mentioned | Count | Notes |

| B1, B2 | 2 | Intermediate proficiency |

| B1 | 2 | Lower intermediate |

| A1-C2 (full range) | 1 | Comprehensive framework |

| "Intermediate" (non-standard) | 1 | Lacks CEFR precision |

| Pillar | Papers Addressing | Percentage | Implication |

| Grounding Pillar (Output Constraints) | 11/51 | 21.6% | Output control mechanisms underreported |

| Validation Pillar (Source Verification) | 0/51 | 0.0% | Complete absence of source validation |

| Paper Type | Papers (n) | Expected Gap | NR Rate | Crisis Gap | NR Rate |

| FL-only | 11 | CEFR alignment | 100% | Parameter count | 100% |

| KG-only | 15 | CEFR alignment | 93.3% | Validation metrics | 86.7% |

| LLM-only | 4 | CEFR alignment | 100% | Parameter count | 75% |

| Hybrid* | 5 | N/A | - | CEFR alignment | 100% |

| Metric | Count | Type | Pedagogical Relevance |

| KGQI (Knowledge Graph Quality Index) | 2 | KG validation | ✓ Pedagogical-specific |

| HITL (Human-in-the-Loop) | 1 | User evaluation | ✓ Pedagogical-specific |

| Hits@k | 1 | Retrieval accuracy | ✗ Generic IR metric |

| ACC, PCC | 1 | Accuracy metrics | ✗ Generic ML metrics |

| FL Architecture | Count (Manual Review) | Percentage |

| Decentralized | 13 | 92.9% |

| Centralized | 1 | 7.1% |

| KG Type | Count | Percentage |

| Ontology | 15 | 83.3% |

| Property Graph | 2 | 11.1% |

| Embedding-based [31] | 1 | 5.6% |

| Hypothesis | Prediction | Observed Result | Threshold Met | Conclusion |

| H1: Convergence Deficit | < 15% FL+KG+LLM | 0.0% (n=0) | Yes | SUPPORTED |

| H2: Reporting Gap | > 60% NR rate | 84.5% avg NR | Yes | SUPPORTED |

| H3: Scale Bias | > 70% centralized | 96.1% NR (param.) | N/A | UNTESTABLE (DATA INSUFFICIENT) |

| H4: Pedagogical Gap | < 20% CEFR mention | 11.8% (n=6) | Yes | SUPPORTED |

| H5: Validation Metrics Gap | < 10% metrics | 9.8% (n=5) | Yes | SUPPORTED |

| Pedagogical Variable | Papers Reporting | Percentage | Hypothesis | Result |

| CEFR Alignment Mentioned | 6 | 11.8% | H4: < 20% | SUPPORTED |

| Validation Metrics Reported | 5 | 9.8% | H5: < 10% | SUPPORTED |

| Grounding Pillar Addressed (Output Constraints) |

11 | 21.6% | • | • |

| Validation Pillar Addressed (Source Verification) |

0 | 0.0% | RQ3 | CRITICAL GAP |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).