Submitted:

20 January 2026

Posted:

21 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

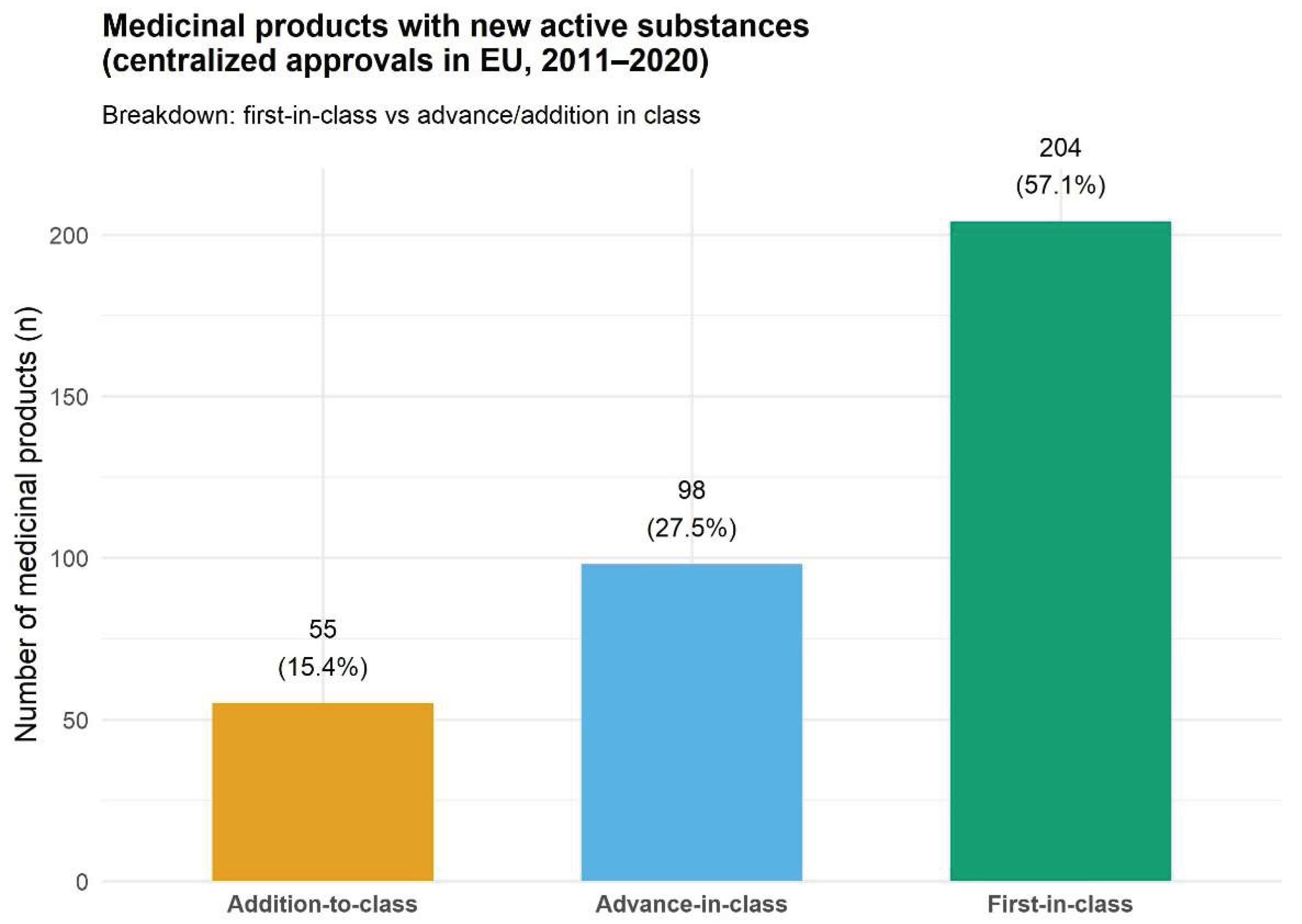

3.1. Distribution by Innovation Degree

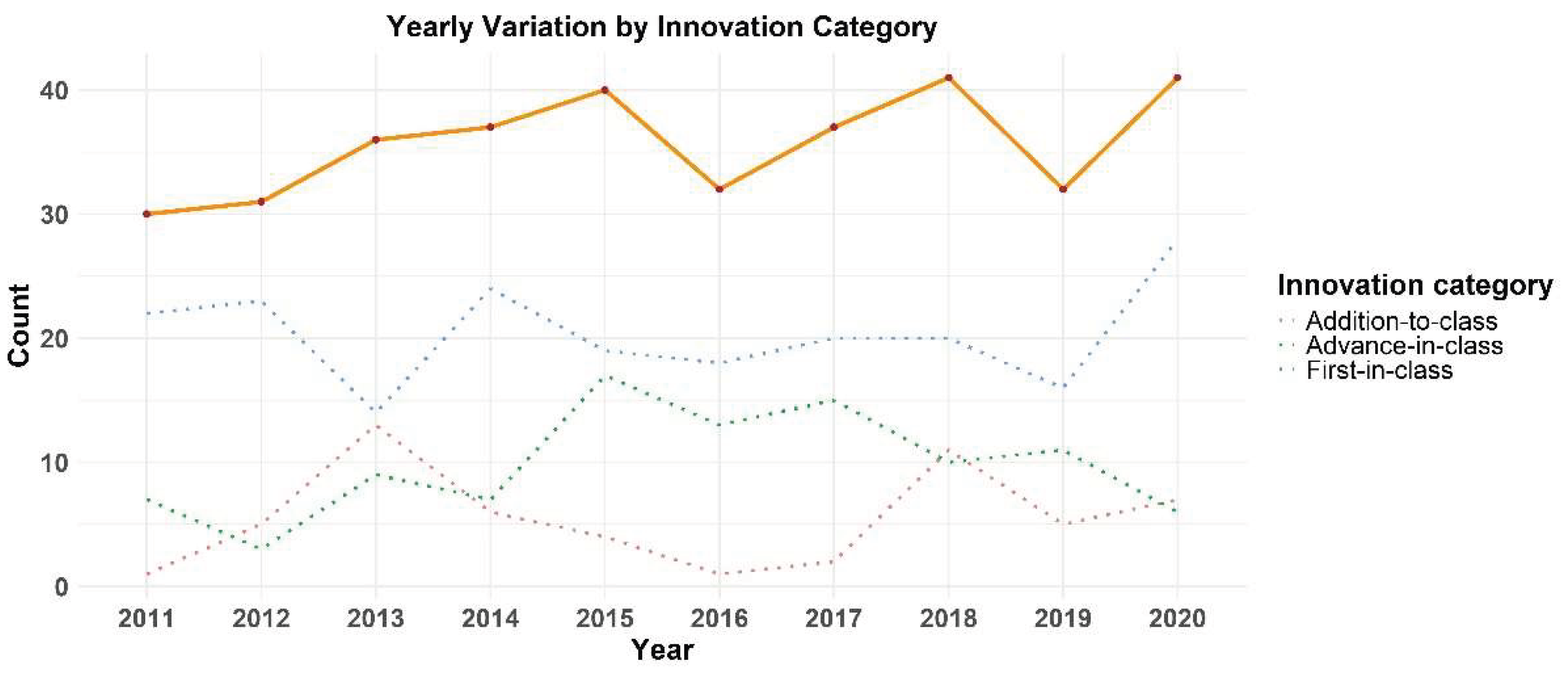

3.2. Time Evolution

3.3. Variation by Technology Class

3.4. Administration Routes

3.5. Pharmaceutical Forms

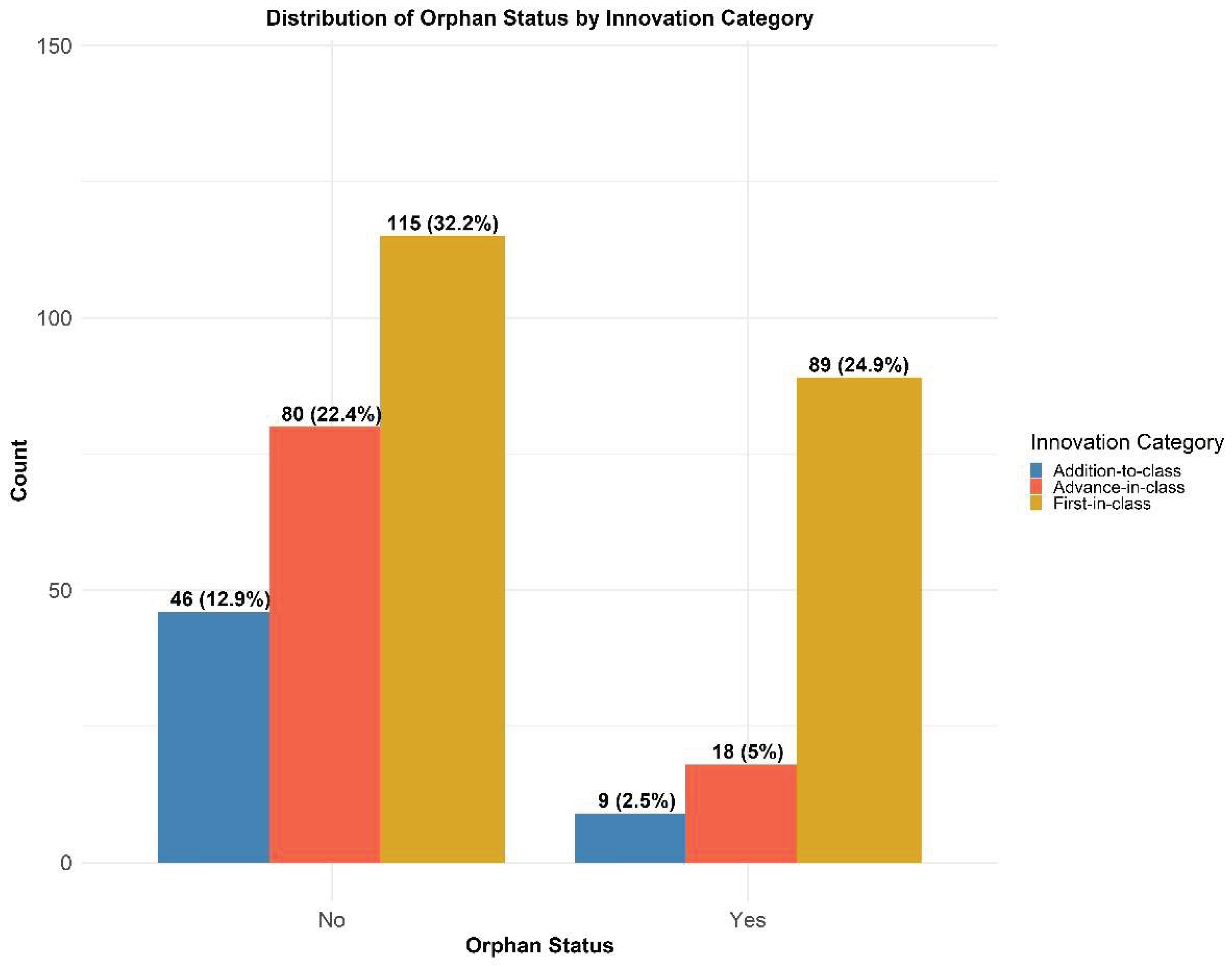

3.6. Orphan Versus Non-Orphan Products

4. Discussion

4.1. Innovation Levels and Competition Landscape

4.2. Time Evolution

4.3. Therapeutic Classes

4.4. Administration Routes

4.5. Pharmaceutical Forms

- Pediatric-oriented formulations, such as chewable tablets and granules for oral suspension in sachets, remain underrepresented despite regulatory incentives for pediatric drug development [115]. The limited presence of gastro-resistant dosage forms suggests that few new active substances need shielding from gastric acid, or that acceptable bioavailability can generally be achieved without enteric protection. This could be a consequence of current discovery efforts emphasizing compounds with robust absorption profiles or the deployment of alternative tools like acid-resistant prodrug designs. On the other hand, while enteric coating can optimize a drug’s stability and release profile, its actual impact on oral bioavailability remains debatable, as its effectiveness often fluctuates based on a complex interplay between the drug’s chemical properties and the physiology factors such as gastric transit speed and pH fluctuations [116].

- Innovative delivery systems, including implants (e.g., Scenesse/alfamelanotide [117]) and tissue-engineered therapies (e.g., Spherox, Holoclar) [117,118], are the result of the fusion of pharmaceutical innovation and regenerative medicine. While such products are still relatively rare, they reflect the rise of personalized [119] and long-acting therapies[120]. Scenesse’s implant, which achieves two months of continuous drug release, illustrates how such advanced technologies can redefine treatment approaches by minimizing the frequency of administration.

- While most radiopharmaceuticals approved during this period were formulated as conventional forms (such as solutions for injection, included in the products discussed earlier), three products were formulated as radiopharmaceutical precursor solutions (two) and a kit for radiopharmaceutical preparation. They reflect the unique requirements of nuclear medicine, where the radiopharmaceutical precursor must undergo radiolabeling at the clinical site, and kits must enable rapid, reliable preparation while maintaining radiochemical purity, labeling efficiency, and overall quality of the final radiopharmaceutical [121,122]. The predominance of ready-to-use solutions among radiopharmaceuticals indicates progress in developing stable formulations that can be centrally manufactured and distributed, as well as improved cold-chain logistics and generator-based radionuclides (e.g., 68Ga, 99ᵐTc) [123,124,125], though the persistence of precursors and kits highlights situations where on-site preparation remains necessary, particularly due to the short physical half-lives of certain radionuclides or the complexity of the associated radiolabeling chemistry.

4.6. Orphan Status

4.7. Limitations

4.8. Future Perspectives and Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADC | Antibody-drug conjugates |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| API | Active pharmaceutical ingredients |

| ATMP | Advanced Therapy Medicinal Product |

| CEA | Cost-effectiveness analysis |

| DALY | Disability-Adjusted Life Year |

| EMA | European Medicines Agency |

| EPAR | European Public Assessment Report |

| ERT | Enzyme replacement therapies |

| EU | European Union |

| FDA | Food and Drug Administration |

| FDC | Fixed-dose combination |

| GTMP | Gene therapy medicinal product |

| HCV | Hepatitis C virus |

| HIV | Human immunodeficiency virus |

| ID | Intradermal |

| IM | Intramuscular |

| IV | Intravenous |

| LAL | Lysosomal acid lipase |

| LMIC | Low- and middle-income countries |

| mAb | Monoclonal antibody |

| MAH | Marketing Authorization Holder |

| MPS IVA | Mucopolysaccharidosis type IVA |

| NAS | New active substance |

| NDA | New Drug Application |

| NME | New Molecular Entity |

| QALY | Quality-adjusted life year |

| R&D | Research and Development |

| SC | Subcutaneous |

| sCTMP | Somatic-cell therapy medicines |

| SGLT2 | Sodium/glucose cotransporter 2 |

| siRNA | Small interference RNA |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- Wakutsu, N.; Hirose, E.; Yonemoto, N.; Demiya, S. Assessing Definitions and Incentives Adopted for Innovation for Pharmaceutical Products in Five High-Income Countries: A Systematic Literature Review. Pharmaceut Med 2023, 37, 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horrobin, D.F. Innovation in the Pharmaceutical Industry. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 2000, 93, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urabe, K.; Child, J.; Kagono, T. Innovation and Management: International Comparisons. In De Gruyter Studies in Organization Ser; De Gruyter, Inc: Berlin/Boston, 2018; ISBN 978-3-11-086451-9. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, S.; Lopert, R.; Greyson, D. Toward a Definition of Pharmaceutical Innovation. Open Med 2008, 2, e4-7. [Google Scholar]

- National Museum of the United States Air Force Conquering the Sky: Dec. 17; 1903. Available online: https://www.nationalmuseum.af.mil/Visit/Museum-Exhibits/Fact-Sheets/Display/Article/196027/conquering-the-sky-dec-17-1903/ (accessed on 15.01.2026).

- Nordham, K.D.; Ninokawa, S. The History of Organ Transplantation. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 2022, 35, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, F.J. Macro Trends in Pharmaceutical Innovation. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2005, 4, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaitin, K.I.; DiMasi, J.A. Pharmaceutical Innovation in the 21st Century: New Drug Approvals in the First Decade, 2000–2009. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2011, 89, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munos, B. Lessons from 60 Years of Pharmaceutical Innovation. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2009, 8, 959–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, E.D.; Guyer, M.S.; National Human Genome Research Institute. Charting a Course for Genomic Medicine from Base Pairs to Bedside. Nature 2011, 470, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dubois, P.; De Mouzon, O.; Scott-Morton, F.; Seabright, P. Market Size and Pharmaceutical Innovation. The RAND Journal of Economics 2015, 46, 844–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanthier, M.; Miller, K.L.; Nardinelli, C.; Woodcock, J. An Improved Approach To Measuring Drug Innovation Finds Steady Rates Of First-In-Class Pharmaceuticals, 1987–2011. Health Affairs 2013, 32, 1433–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, D.W. Global Drug Discovery: Europe Is Ahead: A Reanalysis of Data from 1982–2003 Contradicts the Claim That U.S. Drug Firms Overtook European Firms in Pharmaceutical Innovation. Health Affairs 2009, 28, w969–w977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, L.E. Drug Reformulation Regulatory Gaming: Enforcement and Innovation Implications. European Competition Journal 2011, 7, 379–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternitzke, C. Knowledge Sources, Patent Protection, and Commercialization of Pharmaceutical Innovations. Research Policy 2010, 39, 810–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, T.J.; Lipkus, A.H. Structural Approach to Assessing the Innovativeness of New Drugs Finds Accelerating Rate of Innovation. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11, 2114–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicine Agency Annual Reports and Work Programmes. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/about-us/annual-reports-work-programmes (accessed on 15.01.2026).

- European Medicine Agency European Public Assessment Reports (EPARs). Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines (accessed on 15.01.2026).

- European Commission Public Health - Union Register of Medicinal Products. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/documents/community-register/html/index_en.htm (accessed on 15.01.2026).

- European Medicine Agency Assessment Report. Dinutuximab Beta Apeiron International Non-Proprietary Name: Dinutuximab Beta 2017.

- McKeage, K.; Lyseng-Williamson, K.A. Dinutuximab Beta in High-Risk Neuroblastoma: A Profile of Its Use. Drugs Ther Perspect 2018, 34, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaeli, D.T.; Michaeli, T.; Albers, S.; Boch, T.; Michaeli, J.C. Special FDA Designations for Drug Development: Orphan, Fast Track, Accelerated Approval, Priority Review, and Breakthrough Therapy. The European Journal of Health Economics 2024, 25, 979–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Grosso, V.; Perini, M.; Casilli, G.; Costa, E.; Boscaro, V.; Miglio, G.; Genazzani, A.A. Performance of the Accelerated Assessment of the European Medicines Agency. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 2025, 91, 1439–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicine Agency European Medicines Agency. EMA/7872/2021 2024; Guidance for Applicants Seeking Access to PRIME Scheme.

- Franco, P.; Jain, R.; Rosenkrands-Lange, E.; Hey, C.; Koban, M.U. Regulatory Pathways Supporting Expedited Drug Development and Approval in ICH Member Countries. Ther Innov Regul Sci 2023, 57, 484–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, T.J.; Ross, J.S.; Vokinger, K.N.; Kesselheim, A.S. Association between FDA and EMA Expedited Approval Programs and Therapeutic Value of New Medicines: Retrospective Cohort Study. BMJ 2020, 371, m3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Rajabi, S.; Shi, C.; Afifirad, G.; Omidi, N.; Kouhsari, E.; Khoshnood, S.; Azizian, K. Antibacterial Activity of Recently Approved Antibiotics against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus (MRSA) Strains: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 2022, 21, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eder, J.; Sedrani, R.; Wiesmann, C. The Discovery of First-in-Class Drugs: Origins and Evolution. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2014, 13, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohler, M. Regulatory Pathways in the European Union. MAbs 2011, 3, 241–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Kesselheim, A.S. First-In-Class Drugs Experienced Different Regulatory Treatment In The US And Europe. Health Aff (Millwood) 2025, 44, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lythgoe, M.P.; Sullivan, R.; Blagden, S. UK Oncology Approvals in 2022: Global Regulatory Collaboration and New Regulatory Pathways Deliver New Anti-Cancer Therapies. The Lancet Oncology 2023, 24, 963–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jena, A.B.; Calfee, J.E.; Mansley, E.C.; Philipson, T.J. “Me-Too” Innovation in Pharmaceutical Markets. Forum Health Econ Policy 2009, 12(5), 1558–9544.1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aronson, J.K.; Green, A.R. Me-too Pharmaceutical Products: History, Definitions, Examples, and Relevance to Drug Shortages and Essential Medicines Lists. Brit J Clinical Pharma 2020, 86, 2114–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuyama, R. Chronological Analysis of First-in-Class Drugs Approved from 2011 to 2022: Their Technological Trend and Origin. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMasi, J.A.; Paquette, C. The Economics of Follow-on Drug Research and Development: Trends in Entry Rates and the Timing of Development. PharmacoEconomics 2004, 22, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiMasi, J.A.; Faden, L.B. Competitiveness in Follow-on Drug R&D: A Race or Imitation? Nature Reviews Drug Discovery 2011, 10, 23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, X.; Zhao, Q.; Hui, J.; Wang, T.; Lin, M.; Wang, K.; Zhang, J.; Shentu, J.; Dalby, P.A.; Zhang, H.; et al. The Global Landscape of Approved Antibody Therapies. Antib Ther 2022, 5, 233–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerriaud, M.; Kohli, E. RNA-Based Drugs and Regulation: Toward a Necessary Evolution of the Definitions Issued from the European Union Legislation. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 1012497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, K.; Nonami, A.; Shinohara, K.; Nagai, S. Regulatory Approval of CAR-T Cell and BsAb Products for Lymphoid Neoplasms in the US, EU, and Japan. Clin Pharma and Therapeutics 2025, 118, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellino, S.; La Salvia, A.; Cometa, M.F.; Botta, R. Cell-Based Medicinal Products Approved in the European Union: Current Evidence and Perspectives. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1200808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission Rare Diseases. EU Research on Rare Diseases. Available online: https://research-and-innovation.ec.europa.eu/research-area/health/rare-diseases_en?utm_source=copilot.com (accessed on 15.01.2026).

- Ringborg, U.; Berns, A.; Celis, J.E.; Heitor, M.; Tabernero, J.; Schüz, J.; Baumann, M.; Henrique, R.; Aapro, M.; Basu, P.; et al. The Porto European Cancer Research Summit 2021. Molecular Oncology 2021, 15, 2507–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batta, A.; Kalra, B.S.; Khirasaria, R. Trends in FDA Drug Approvals over Last 2 Decades: An Observational Study. J Family Med Prim Care 2020, 9, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodier, C.; Bujar, M.; McAuslane, N.; Liberti, L.; Munro, J. New Drug Approvals in Six Major Authorities 2010–2019: Focus on Facilitated Regulatory Pathways and Internationalisation. R&D Briefing 2020, 77, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- US Food & Drug Administration 2016 Novel Drugs Summary. Available online: https://fda.report/media/102618/2016-Novel-Drugs-Summary.pdf?utm_source=copilot.com (accessed on 15.01.2026).

- Daizadeh, I. US FDA Drug Approvals Are Persistent and Polycyclic: Insights into Economic Cycles, Innovation Dynamics, and National Policy. Ther Innov Regul Sci 2021, 55, 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebied, A.M.; Na, J.; Cooper-DeHoff, R.M. New Drug Approvals in 2018 - Another Record Year! Am J Med 2019, 132, 1038–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra-Majumdar, M.; Gunter, S.J.; Kesselheim, A.S.; Brown, B.L.; Joyce, K.W.; Ross, M.; Pham, C.; Avorn, J.; Darrow, J.J. Analysis of Supportive Evidence for US Food and Drug Administration Approvals of Novel Drugs in 2020. JAMA Netw Open 2022, 5, e2212454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; McAuslane, N. New Drug Approvals in ICH Countries: 2002–2011. Center for Innovation in Regulatory Science, White Paper. Abgerufen. 2012, 11.

- Falcone, R.; Lombardi, P.; Filetti, M.; Duranti, S.; Pietragalla, A.; Fabi, A.; Lorusso, D.; Altamura, V.; Paroni Sterbini, F.; Scambia, G.; et al. Oncologic Drugs Approval in Europe for Solid Tumors: Overview of the Last 6 Years. Cancers 2022, 14, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.-R.; Choi, S. New Drug Expenditure by Therapeutic Area in South Korea: International Comparison and Policy Implications. Healthcare 2025, 13, 468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, T.; Haslam, A.; Prasad, V. Anticancer Drugs Approved by the US Food and Drug Administration From 2009 to 2020 According to Their Mechanism of Action. JAMA Netw Open 2021, 4, e2138793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.; Zhou, S. Six Events That Shaped Antibody Approvals in Oncology. Front Immunol 2025, 16, 1533796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojciechowski, D.; Wiseman, A. Long-Term Immunosuppression Management: Opportunities and Uncertainties. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2021, 16, 1264–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.; Zhong, W.; Zhao, H.; An, Y.; Dong, X.; Li, Z.; Qin, S.; Xu, G.; Yue, X.; Wang, X.; et al. Multifunctional Nano Immunostimulant: Overcoming Immunosuppressive Microenvironment for Antitumor Immunotherapy. Advanced Science 2025, e17480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, C.; Denlinger, N.; Yang, Y. Recent Advances and Challenges in Cancer Immunotherapy. Cancers 2022, 14, 3972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frontiers in Clinical Drug Research: HIV; Atta-ur-Rahman, Ed.; Frontiers in Clinical Drug Research: HIV; BENTHAM SCIENCE PUBLISHERS, 2021; Vol. 5, ISBN 978-981-14-6445-4. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri, S.; Symons, J.A.; Deval, J. Innovation and Trends in the Development and Approval of Antiviral Medicines: 1987-2017 and Beyond. Antiviral Res 2018, 155, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chahine, E.B.; Durham, S.H. Ibalizumab: The First Monoclonal Antibody for the Treatment of HIV-1 Infection. Ann Pharmacother 2021, 55, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarębska-Michaluk, D.; Jaroszewicz, J.; Parfieniuk-Kowerda, A.; Janczewska, E.; Dybowska, D.; Pawłowska, M.; Halota, W.; Mazur, W.; Lorenc, B.; Janocha-Litwin, J.; et al. Effectiveness and Safety of Pangenotypic Regimens in the Most Difficult to Treat Population of Genotype 3 HCV Infected Cirrhotics. JCM 2021, 10, 3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, J.; An, S.; Zhang, Z. Efficacy and Safety of Intravenous Peramivir versus Oral Oseltamivir in the Treatment of Influenza in Children: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Virology Plus 2024, 4, 100179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.-H.; Hsu, T.-H.; Lin, T.-Y.; Liu, C.-H.; Chou, S.-C.; Wu, J.-Y.; Perng, P.-C. Comparing Intravenous Peramivir with Oral Oseltamivir for Patients with Influenza: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy 2021, 19, 1039–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraishi, C.; Kato, H.; Hagihara, M.; Asai, N.; Iwamoto, T.; Mikamo, H. Comparison of Clinical Efficacy and Safety of Baloxavir Marboxil versus Oseltamivir as the Treatment for Influenza Virus Infections: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Infection and Chemotherapy 2024, 30, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordon, C.J.; Lee, H.W.; Tchesnokov, E.P.; Perry, J.K.; Feng, J.Y.; Bilello, J.P.; Porter, D.P.; Götte, M. Efficient Incorporation and Template-Dependent Polymerase Inhibition Are Major Determinants for the Broad-Spectrum Antiviral Activity of Remdesivir. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2022, 298, 101529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gastaldi, G.; Lucchini, B.; Thalmann, S.; Alder, S.; Laimer, M.; Brändle, M.; Wiesli, P.; Lehmann, R. Working Group Of The Sged/Ssed Swiss Recommendations of the Society for Endocrinology and Diabetes (SGED/SSED) for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (2023). Swiss Med Wkly 2023, 153, 40060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahl, E.; Kurko, T.; Koskinen, H.; Airaksinen, M.; Sarnola, K. EMA Approved Orphan Medicines since the Implementation of the Orphan Legislation. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2025, 20, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, E.M. SGLT2 Inhibitors: Physiology and Pharmacology. Kidney360 2021, 2, 2027–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, N.; Lee, M.M.; Kristensen, S.L.; Branch, K.R.; Del Prato, S.; Khurmi, N.S.; Lam, C.S.; Lopes, R.D.; McMurray, J.J.; Pratley, R.E.; et al. Cardiovascular, Mortality, and Kidney Outcomes with GLP-1 Receptor Agonists in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomised Trials. The lancet Diabetes & endocrinology 2021, 9, 653–662. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, J.; Duan, H.; Qin, Q.; Teng, Z.; Gan, F.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, X. Advances in Oral Drug Delivery Systems: Challenges and Opportunities. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahiwala, A. Formulation Approaches in Enhancement of Patient Compliance to Oral Drug Therapy. Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery 2011, 8, 1521–1529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azman, M.; Sabri, A.H.; Anjani, Q.K.; Mustaffa, M.F.; Hamid, K.A. Intestinal Absorption Study: Challenges and Absorption Enhancement Strategies in Improving Oral Drug Delivery. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, V.; Varum, F.; Bravo, R.; Furrer, E.; Basit, A.W. Gastrointestinal Stability of Therapeutic Anti-TNF α IgG1 Monoclonal Antibodies. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2016, 502, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skalko-Basnet, N. Biologics: The Role of Delivery Systems in Improved Therapy. Biologics 2014, 8, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panchal, K.; Katke, S.; Dash, S.K.; Gaur, A.; Shinde, A.; Saha, N.; Mehra, N.K.; Chaurasiya, A. An Expanding Horizon of Complex Injectable Products: Development and Regulatory Considerations. Drug Deliv Transl Res 2023, 13, 433–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedaya, M.A. Routes of Drug Administration. In Pharmaceutics; Elsevier, 2024; pp. 537–554. ISBN 978-0-323-99796-6. [Google Scholar]

- Stielow, M.; Witczyńska, A.; Kubryń, N.; Fijałkowski, Ł.; Nowaczyk, J.; Nowaczyk, A. The Bioavailability of Drugs-The Current State of Knowledge. Molecules 2023, 28, 8038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitiot, A.; Heuzé-Vourc’h, N.; Sécher, T. Alternative Routes of Administration for Therapeutic Antibodies-State of the Art. Antibodies (Basel) 2022, 11, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, J.D.; Bravo Padros, M.; Conrado, D.J.; Ganguly, S.; Guan, X.; Hassan, H.E.; Hazra, A.; Irvin, S.C.; Jayachandran, P.; Kosloski, M.P.; et al. Subcutaneous Administration of Monoclonal Antibodies: Pharmacology, Delivery, Immunogenicity, and Learnings From Applications to Clinical Development. Clin Pharma and Therapeutics 2024, 115, 422–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surasi, D.S.; O’Malley, J.; Bhambhvani, P. 99mTc-Tilmanocept: A Novel Molecular Agent for Lymphatic Mapping and Sentinel Lymph Node Localization. J Nucl Med Technol 2015, 43, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Pardo, D.; Pigrau, C.; Campany, D.; Diaz-Brito, V.; Morata, L.; De Diego, I.C.; Sorlí, L.; Iftimie, S.; Pérez-Vidal, R.; García-Pardo, G.; et al. Effectiveness of Sequential Intravenous-to-Oral Antibiotic Switch Therapy in Hospitalized Patients with Gram-Positive Infection: The SEQUENCE Cohort Study. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2016, 35, 1269–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homayun, B.; Lin, X.; Choi, H.-J. Challenges and Recent Progress in Oral Drug Delivery Systems for Biopharmaceuticals. Pharmaceutics 2019, 11, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapteva, L.; Purohit-Sheth, T.; Serabian, M.; Puri, R.K. Clinical Development of Gene Therapies: The First Three Decades and Counting. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2020, 19, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomo, G.M.; Pose-Boirazian, T.; Naumann-Winter, F.; Costa, E.; Duarte, D.M.; Kalland, M.E.; Malikova, E.; Matusevicius, D.; Vitezic, D.; Larsson, K.; et al. The European Landscape for Gene Therapies in Orphan Diseases: 6-Year Experience with the EMA Committee for Orphan Medicinal Products. Mol Ther 2023, 31, 3414–3423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avanthay, R.; Garcia-Nicolas, O.; Ruggli, N.; Grau-Roma, L.; Párraga-Ros, E.; Summerfield, A.; Zimmer, G. Evaluation of a Novel Intramuscular Prime/Intranasal Boost Vaccination Strategy against Influenza in the Pig Model. PLoS Pathog 2024, 20, e1012393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M.; Sepodes, B.; Martins, A.P. Regulatory and Scientific Advancements in Gene Therapy: State-of-the-Art of Clinical Applications and of the Supporting European Regulatory Framework. Front. Med. 2017, 4, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, B.R.; Jakka, D.; Sandoval, M.A.; Kulkarni, V.R.; Bao, Q. Advancements in Ocular Therapy: A Review of Emerging Drug Delivery Approaches and Pharmaceutical Technologies. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gade, S.; So, Y.; Mishra, D.; Baviskar, S.M.; Assiri, A.A.; Glover, K.; Sheshala, R.; Vora, L.K.; Thakur, R.R.S. Ocular Drug Delivery: Emerging Approaches and Advances. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowe, L.W.; Akotoye, C.; Harris, A.; Ciulla, T.A. Beyond the Injection: Delivery Systems Reshaping Retinal Disease Management. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2025, 26, 939–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, A.N. A Comprehensive Review on Pharmaceutical Film Coating: Past, Present, and Future. Drug Des Devel Ther 2020, 14, 4613–4623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.Y.; Martin, J.H.; Mclachlan, A.J.; Boddy, A.V. Precision Dosing of Targeted Anticancer Drugs—Challenges in the Real World. Transl. Cancer Res 2017, 6, S1500–S1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyner, E.; Lum, B.; Jing, J.; Kagedal, M.; Ware, J.A.; Dickmann, L.J. Intrinsic and Extrinsic Pharmacokinetic Variability of Small Molecule Targeted Cancer Therapy. Clinical Translational Sci 2020, 13, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habet, S. Narrow Therapeutic Index Drugs: Clinical Pharmacology Perspective. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2021, 73, 1285–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Q.; Lee, Y.; Zhou, T. Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Modeling of Therapeutic Antibodies in Oncology: Current Advances and Future Perspectives. J. Pharm. Investig. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-L.; Shah, V.P.; Ganes, D.; Midha, K.K.; Caro, J.; Nambiar, P.; Rocci, M.L.; Thombre, A.G.; Abrahamsson, B.; Conner, D.; et al. Challenges and Opportunities in Establishing Scientific and Regulatory Standards for Assuring Therapeutic Equivalence of Modified-Release Products: Workshop Summary Report. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2010, 40, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laichapis, M.; Sakulbumrungsil, R.; Udomaksorn, K.; Kessomboon, N.; Nerapusee, O.; Hongthong, C.; Poonpolsub, S. Financial Feasibility of Developing Sustained-Release Incrementally Modified Drugs in Thailand’s Pharmaceutical Industry: Mixed Methods Study. JMIRx Med 2025, 6, e65978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, J.; Dunn, J.D.; Johnson, M.M.; Karst, K.R.; Shear, W.C. How Drug Life-Cycle Management Patent Strategies May Impact Formulary Management. Am J Manag Care 2016, 22, S487–S495. [Google Scholar]

- Stegemann, S.; Tian, W.; Morgen, M.; Brown, S. CHAPTER 2. Hard Capsules in Modern Drug Delivery. In Drug Discovery; Tovey, G.D., Ed.; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, 2018; pp. 21–51. ISBN 978-1-84973-941-2. [Google Scholar]

- Tovey, G. Pharmaceutical Formulation: The Science and Technology of Dosage Forms; RSC Drug discovery series; Royal Society of Chemistry: Cambridge, 2018; ISBN 978-1-84973-941-2. [Google Scholar]

- Savla, R.; Browne, J. Softgel Formulations - Lipid-Based Drug Delivery System to Bring Poorly Soluble Drugs to Market. Drug development & Delivery. 2016. Available online: https://drug-dev.com/softgel-formulations-lipid-based-drug-delivery-system-to-bring-poorly-soluble-drugs-to-market/ (accessed on 15.01.2026).

- Sarvepalli, S.; Pasika, S.R.; Verma, V.; Thumma, A.; Bolla, S.; Nukala, P.K.; Butreddy, A.; Bolla, P.K. A Review on the Stability Challenges of Advanced Biologic Therapeutics. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le Basle, Y.; Chennell, P.; Tokhadze, N.; Astier, A.; Sautou, V. Physicochemical Stability of Monoclonal Antibodies: A Review. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2020, 109, 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Duong, H.T.T.; Hu, Q.; Shameem, M.; Tang, X. (Charlie) Practical Advice in the Development of a Lyophilized Protein Drug Product. Antibody Therapeutics 2025, 8, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butreddy, A.; Janga, K.Y.; Ajjarapu, S.; Sarabu, S.; Dudhipala, N. Instability of Therapeutic Proteins — An Overview of Stresses, Stabilization Mechanisms and Analytical Techniques Involved in Lyophilized Proteins. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 167, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrababu, K.B.; Kannan, A.; Savage, J.R.; Stadmiller, S.; Ryle, A.E.; Cheung, C.; Kelley, R.F.; Maa, Y.; Saggu, M.; Bitterfield, D.L. Stability Comparison Between Microglassification and Lyophilization Using a Monoclonal Antibody. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2024, 113, 1054–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castañeda Ruiz, A.J.; Shetab Boushehri, M.A.; Phan, T.; Carle, S.; Garidel, P.; Buske, J.; Lamprecht, A. Alternative Excipients for Protein Stabilization in Protein Therapeutics: Overcoming the Limitations of Polysorbates. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bramham, J.E.; Davies, S.A.; Podmore, A.; Golovanov, A.P. Stability of a High-Concentration Monoclonal Antibody Solution Produced by Liquid-Liquid Phase Separation. MAbs 2021, 13, 1940666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bas, T.G. Innovative Formulation Strategies for Biosimilars: Trends Focused on Buffer-Free Systems, Safety, Regulatory Alignment, and Intellectual Property Challenges. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makwana, S.; Basu, B.; Makasana, Y.; Dharamsi, A. Prefilled Syringes: An Innovation in Parenteral Packaging. Int J Pharm Investig 2011, 1, 200–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittner, B.; Richter, W.; Schmidt, J. Subcutaneous Administration of Biotherapeutics: An Overview of Current Challenges and Opportunities. BioDrugs 2018, 32, 425–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, W.-K.; Herbig, M.E.; Newsam, J.M.; Gottwald, U.; May, E.; Winckle, G.; Birngruber, T. Opportunities of Topical Drug Products in a Changing Dermatological Landscape. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2024, 203, 106913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Lockwood, A. Topical Ocular Drug Delivery Systems: Innovations for an Unmet Need. Experimental Eye Research 2022, 218, 109006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, E.; Gooderham, M.; Torres, T. New Topical Therapies in Development for Atopic Dermatitis. Drugs 2022, 82, 843–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lie, E.; Choi, M.; Wang, S.-P.; Eichenfield, L.F. Topical Management of Pediatric Psoriasis: A Review of New Developments and Existing Therapies. Pediatr Drugs 2024, 26, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan-Warren, P.J.; Morarji, J.B. Trends in Licence Approvals for Ophthalmic Medicines in the United Kingdom. Eye 2020, 34, 1856–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, I.; Sousa, J.J.; Vitorino, C. Paediatric Medicines – Regulatory Drivers, Restraints, Opportunities and Challenges. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2021, 110, 1545–1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maderuelo, C.; Lanao, J.M.; Zarzuelo, A. Enteric Coating of Oral Solid Dosage Forms as a Tool to Improve Drug Bioavailability. Eur J Pharm Sci 2019, 138, 105019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerth, A.; Opitz, C.H.; Lee, K. Manufacturing, Approval and Market Launch of Tissue Engineered Products in Europe. Cytotherapy 2024, 26, S107–S108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, G.; Ardigò, D.; Milazzo, G.; Iotti, G.; Guatelli, P.; Pelosi, D.; De Luca, M. Navigating Market Authorization: The Path Holoclar Took to Become the First Stem Cell Product Approved in the European Union. Stem Cells Translational Medicine 2018, 7, 146–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghi, H.S.; Al-hakeem, M.A.; Almajidi, Y.Q. The Evolution of Drug Delivery Systems: Historical Advances and Future Directions. Journal of Pharmacology and Drug Development 2025, 3, 13–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bassand, C.; Villois, A.; Gianola, L.; Laue, G.; Ramazani, F.; Riebesehl, B.; Sanchez-Felix, M.; Sedo, K.; Ullrich, T.; Duvnjak Romic, M. Smart Design of Patient-Centric Long-Acting Products: From Preclinical to Marketed Pipeline Trends and Opportunities. Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery 2022, 19, 1265–1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pijarowska-Kruszyna, J.; Garnuszek, P.; Decristoforo, C.; Mikołajczak, R. Radiopharmaceutical Precursors. Theranostics: An Old Concept in New Clothing 2021, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Gillings, N.; Hjelstuen, O.; Ballinger, J.; Behe, M.; Decristoforo, C.; Elsinga, P.; Ferrari, V.; Peitl, P.K.; Koziorowski, J.; Laverman, P.; et al. Guideline on Current Good Radiopharmacy Practice (cGRPP) for the Small-Scale Preparation of Radiopharmaceuticals. EJNMMI radiopharmacy and chemistry 2021, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ioppolo, J.A.; Alvarez de Eulate, E.; Cullen, D.R.; Mohamed, S.; Morandeau, L. Development of a High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Method for Rapid Radiochemical Purity Measurement of [18F] PSMA-1007, a PET Radiopharmaceutical for Detection of Prostate Cancer. Journal of Labelled Compounds and Radiopharmaceuticals 2023, 66, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, P. Theranostics in the Indian Subcontinent: Opportunities, Challenges, and the Path Forward. Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 2025, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Shao, Y.; Li, Z.; Luo, M.; Xu, D.; Ma, L. Research Progress on Major Medical Radionuclide Generators. Processes 2025, 13, 521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahl, E.; Kurko, T.; Koskinen, H.; Airaksinen, M.; Sarnola, K. EMA Approved Orphan Medicines since the Implementation of the Orphan Legislation. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2025, 20, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Monguio, R.; Spargo, T.; Seoane-Vazquez, E. Ethical Imperatives of Timely Access to Orphan Drugs: Is Possible to Reconcile Economic Incentives and Patients’ Health Needs? Orphanet J Rare Dis 2017, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarpatwari, A.; Beall, R.F.; Abdurrob, A.; He, M.; Kesselheim, A.S. Evaluating The Impact Of The Orphan Drug Act’s Seven-Year Market Exclusivity Period. Health Aff (Millwood) 2018, 37, 732–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, Q.; You, Q.; Wang, L. A Decade of Approved First-in-Class Small Molecule Orphan Drugs: Achievements, Challenges and Perspectives. Eur J Med Chem 2022, 243, 114742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantor, A.; Haga, S.B. The Potential Benefit of Expedited Development and Approval Programs in Precision Medicine. JPM 2021, 11, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacoub, E.; Lefebvre, N.B.; Milunov, D.; Sarkar, M.; Saha, S. Quantifying Hope: An EU Perspective of Rare Disease Therapeutic Space and Market Dynamics. Front. Public Health 2025, 13, 1520467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, J.D.; Silver, M.C.; Berklein, F.C.; Cohen, J.T.; Neumann, P.J. Orphan Drugs Offer Larger Health Gains but Less Favorable Cost-Effectiveness than Non-Orphan Drugs. J Gen Intern Med 2020, 35, 2629–2636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postma, M.J.; Noone, D.; Rozenbaum, M.H.; Carter, J.A.; Botteman, M.F.; Fenwick, E.; Garrison, L.P. Assessing the Value of Orphan Drugs Using Conventional Cost-Effectiveness Analysis: Is It Fit for Purpose? Orphanet J Rare Dis 2022, 17, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alum, E.U.; Ekpang Ii, J.E.; Ekpang, P.O.; Ainebyoona, C.; Nwagu, K.E.; Nwuruku, O.A.; Muhammad, K. Toward an Ethical Future for Orphan Drugs: Balancing Access, Affordability, and Innovation. J Med Econ 2025, 28, 1869–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onakpoya, I.J.; Spencer, E.A.; Thompson, M.J.; Heneghan, C.J. Effectiveness, Safety and Costs of Orphan Drugs: An Evidence-Based Review. BMJ Open 2015, 5, e007199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| ATC Code | Category | Drug Count |

|---|---|---|

| L | Antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents | 129 |

| J | Antiinfectives for systemic use | 67 |

| A | Alimentary tract and metabolism | 38 |

| B | Blood and blood forming organs | 34 |

| N | Nervous system | 24 |

| V | Various | 18 |

| C | Cardiovascular system | 11 |

| M | Musculo-skeletal system | 10 |

| R | Respiratory system | 10 |

| D | Dermatologicals | 7 |

| S | Sensory organs | 7 |

| G | Genito-urinary system and sex hormones | 5 |

| H | Systemic hormonal preparations | 3 |

| Technology class | Number of medicinal products | First in class (% within column) |

Advance in class (% within column) | Addition to class (% within column) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small molecules | 157 | 80 (39.22%) | 50 (51.02%) | 27 (49.09%) |

| Monoclonal antibodies | 64 | 45 (22.06%) | 6 (6.12%) | 13 (23.64%) |

| Proteins/polypeptides | 51 | 33 (16.18%) | 11 (11.22%) | 7 (12.73%) |

| FDCs | 27 | 4 (1.96%) | 18 (18.37%) | 5 (9.09%) |

| Vaccines | 18 | 9 (4.41%) | 9 (9.18%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Radiopharmaceuticals | 9 | 7 (3.43%) | 0 (0.00%) | 2 (3.64%) |

| ATMP cell therapies | 5 | 5 (2.45%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Gene therapies (excluding CAR-T cells) | 5 | 5 (2.45%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| siRNA | 4 | 4 (1.96%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Complex, non-herbal | 5 | 2 (0.98%) | 2 (2.04%) | 1 (1.82%) |

| CAR-T cells | 3 | 3 (1.47%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Antisense oligonucleotides | 3 | 3 (1.47%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Complex, herbal | 3 | 3 (1.47%) | 0 (0.00%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Glycopeptides | 3 | 1 (0.49%) | 2 (2.04%) | 0 (0.00%) |

| Total | 357 | 204 (57.14%) | 98 (27.45%) | 55 (15.41%) |

| Administration_route | Addition-to-class | Advance-in-class | First-in-class |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral | 28 | 57 | 73 |

| IV | 14 | 17 | 75 |

| SC | 7 | 9 | 28 |

| IM | 1 | 7 | 5 |

| Topical | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Intralesional | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Ophthalmic | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Oral + IV | 0 | 3 | 1 |

| Nasal | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Intravitreal | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| ID + SC + intratumoral + peritumoral injection (following radiolabelling) | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| In vitro radiolabelling of medicinal products, which are subsequently administered by the approved route | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Intra-articular | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Intracerebroventricular | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Intrathecal | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| IV (first dose) + SC (subsequent doses) | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Ocular (surgical implantation onto the corneal surface / under the conjunctiva) | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| SC (implant) | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Subretinal | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Vaginal | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Inhalation | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Oral + gastroenteral | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Oral + IM | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Oral + enteral | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Administration_route | Addition-to-class (% within column) |

Advance-in-class (% within column) |

First-in-class (% within column) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed | 1 | 5 | 3 |

| Oral | 28 | 57 | 73 |

| Parenteral | 23 | 33 | 116 |

| Topical/Local | 3 | 3 | 9 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Dosage_form | Count |

|---|---|

| Film-coated tablet | 98 |

| Hard capsule | 38 |

| Concentrate for solution for infusion | 35 |

| Solution for injection | 35 |

| Others | 33 |

| Powder for concentrate for solution for infusion | 23 |

| Powder and solvent for solution for injection | 21 |

| Dispersion for infusion | 7 |

| Powder for solution for injection | 6 |

| Tablet | 6 |

| Solution for infusion | 5 |

| Suspension for injection | 5 |

| Prolonged-release tablet | 4 |

| Soft capsule | 4 |

| Gel | 3 |

| Powder for solution for infusion | 3 |

| Solution for injection (pre-filled pen) | 3 |

| Solution for injection in pre-filled pen | 3 |

| Solution for injection in pre-filled syringe | 3 |

| Dispersion for injection | 2 |

| Eye drops, solution | 2 |

| Film-coated tablet + powder for concentrate for solution for infusion | 2 |

| Inhalation powder, pre-dispensed | 2 |

| Nasal spray, suspension | 2 |

| Powder for concentrate and solution for solution for infusion | 2 |

| Powder for concentrate for solution for injection/infusion | 2 |

| Powder for oral suspension | 2 |

| Radiopharmaceutical precursor, solution | 2 |

| Solution for injection (pre-filled pen/syringe) | 2 |

| Suspension for injection (pre-filled syringe) | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).