1. Introduction

Single-use packaging is one of the most critical sources of solid waste worldwide. Recent analyses estimate that around 40% of global plastic waste originates from packaging applications, with similar shares in regions that generate the largest amounts of plastic waste, such as Europe, the United States and China [

1]. In the European Union (EU), packaging waste reached about 79.7 million tonnes in 2021, corresponding to roughly 178 kg per inhabitant [

2,

3]. Within this stream, plastic packaging alone accounts for more than 35 kg per person, of which only about 40–45% is effectively recycled [

3]. These figures highlight the need for new solutions that simultaneously reduce the demand for virgin polymers and create higher-value outlets for post-consumer packaging fractions that are currently under-utilised [

1,

2,

3].

Beverage cartons such as Tetra Pak

® are a representative example of complex multilayer packaging. A typical used carton contains approximately 73–75 wt% cellulose fibres, 20–23 wt% polymers and 4–5 wt% aluminium [

4,

5]. After conventional hydropulping, high-quality fibres can be efficiently recovered, but the remaining polymer–aluminium fraction (commonly referred to as PolyAl) is more challenging to manage because the polyethylene layers and aluminium foil are strongly bonded [

5]. In the last decade, carton manufacturers and recycling companies have invested in dedicated PolyAl recycling lines and in the development of new products such as pallets, crates and outdoor items [

5,

9,

10,

11,

12]. However, existing capacities remain limited compared with the total volume of cartons placed on the market, and additional high-value applications for PolyAl-rich composites are still needed [

5].

In parallel, agro-industrial residues are increasingly recognised as strategic resources within the transition to a circular bioeconomy. Rice husk is one of the most abundant agricultural by-products in rice-producing countries; it is generated in large volumes, is difficult to dispose of and is often under-utilised [

6]. Recent reviews describe rice husk as a lignocellulosic material with relatively low density, significant silica content and a chemical composition that makes it attractive as a filler or reinforcement in polymer matrices [

6]. Studies on rice-husk-reinforced polymer composites show that increasing husk content typically enhances stiffness and sometimes tensile strength, but at the expense of reduced impact resistance and increased water absorption, unless the fibre–matrix interface is carefully engineered with appropriate compatibilisers or surface treatments [

6,

7].

Natural-fibre-reinforced polymer composites and wood–plastic composites (WPCs) have evolved from early formulations based on virgin polymers and wood flour to more complex systems combining recycled polyolefins, diverse lignocellulosic fillers and tailored additives [

6,

7,

8]. Gardner et al. [

8], for example, show how WPCs are now widely used in decking, cladding and outdoor furniture, where moderate mechanical performance and adequate durability under outdoor exposure are required rather than high structural capacity. When these composites incorporate recycled polymers and waste lignocellulosic resources, they can substantially reduce the consumption of tropical hardwoods and virgin plastics in building and outdoor applications [

8].

Alongside agricultural residues, post-consumer multilayer beverage cartons have emerged as a promising but technically demanding waste stream for composite production [

5,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Several thermo-mechanical and mechanical recycling routes have been proposed to transform the polymer–aluminium fraction into cement-based materials, polymer concretes or polymer composites [

5,

9,

10,

11,

12]. Martínez-López et al. [

9] manufacture polymer concretes using recycled high-density polyethylene and PET from Tetra Pak

® containers and report compressive and flexural strengths suitable for small structural elements. Macías-Gallego et al. [

10] evaluate composite materials made from recycled Tetra Pak

® containers, while Martínez-Barrera et al. [

11,

12] investigate the incorporation of Tetra Pak-derived components into concrete and other construction materials, demonstrating viable mechanical performance in non-structural applications. Overall, these studies focus on a single waste stream (either beverage-carton PolyAl or a lignocellulosic residue) and often on laboratory-scale specimens; only a limited number address board- or panel-like products manufactured by extrusion or compression moulding using industrially relevant equipment [

5,

6,

7,

9,

10,

11,

12].

The concept of industrial symbiosis provides a useful framework to integrate these different waste streams into value-added products. Industrial symbiosis is commonly described as a specific application of industrial ecology in which traditionally separate industries collectively gain competitive advantage by exchanging materials, energy, water and by-products within local or regional networks [

13]. Key features include collaboration among firms and the synergistic opportunities created by geographical proximity, which allow one company’s waste stream to become another company’s feedstock [

13]. Recent reviews emphasise that well-designed industrial symbiosis initiatives can significantly reduce waste generation, decrease primary resource demand and improve the overall environmental performance of industrial clusters [

14,

15]. From a policy perspective, industrial symbiosis is increasingly recognised as a practical implementation tool for circular-economy strategies: the European Circular Economy Action Plan calls for high-value uses of secondary raw materials in resource-intensive sectors such as construction, plastics and packaging [

16], while the United Nations 2030 Agenda stresses the need for resilient infrastructure (SDG 9), sustainable cities (SDG 11), responsible consumption and production (SDG 12) and climate action (SDG 13) [

17]. Symbiotic schemes that valorise industrial and agro-food by-products into new materials and construction products directly contribute to these objectives by reducing landfilling, substituting virgin raw materials and enabling more sustainable infrastructure solutions [

14,

15,

16,

17].

Against this background, coupling recycled Tetra Pak® PolyAl with rice husk within a single composite material aligns with the core principles of industrial symbiosis and circular economy. The polymer–aluminium fraction of beverage cartons can act as a secondary polymeric matrix, while rice husk provides a lignocellulosic filler that partially replaces virgin wood flour or mineral fillers. If properly formulated and processed into wood-like boards, such composites could divert both packaging and agricultural residues from low-value uses or disposal, while supplying municipalities and other stakeholders with components suitable for low-load urban furniture applications.

Despite the substantial body of work on rice-husk composites, WPCs and recycled Tetra Pak

® materials [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12], there is, to the best of our knowledge, no systematic study of hybrid boards that combine recycled PolyAl and rice husk in different proportions and that are produced by extrusion plus compression moulding at board thicknesses representative of real products. Existing literature seldom reports a comprehensive mechanical and durability characterization—including tensile and flexural behaviour, surface hardness, water absorption and UV ageing—for such hybrid systems, nor does it explicitly link the measured properties to design windows for low-load structural elements such as park benches or beach walkways [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. This work addresses these gaps by manufacturing wood-like boards from recycled Tetra Pak

® PolyAl and ground rice husk through single-screw extrusion followed by compression moulding. Four formulations with different PolyAl/rice husk ratios are prepared and characterised in terms of density, tensile and flexural properties, surface hardness, water absorption and accelerated UV exposure. The experimental stress–strain curves are further analysed using the constitutive laws of Hollomon, Swift and Voce [

18,

19,

20] too extract parameters relevant for mechanical design. By comparing the performance of the different formulations with data reported for rice-husk and Tetra Pak-based composites [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12] and with typical property ranges for outdoor wood–plastic composites [

8], the study aims to identify a composition that offers a suitable compromise between mechanical performance and durability for low-load urban furniture applications; as shown in the following sections, the intermediate PolyAl/rice husk ratio provides the most balanced solution within the tested range.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Raw Materials

The polymer matrix was an industrially pelletised PolyAl (PA) fraction obtained from post-consumer Tetra Pak® beverage cartons after fibre recovery by hydropulping. The PA consisted of polyethylene as the continuous phase, containing finely dispersed aluminium and residual cellulose fibres.

Rice husk (RH) was supplied by a local rice-processing company. The material was dried and mechanically ground to obtain a particulate lignocellulosic filler with a maximum particle size of approximately 1 mm. A maleic-anhydride-grafted polyethylene (MAPE) compatibilizer was used to improve interfacial adhesion between the hydrophobic PA and the hydrophilic RH. A brown colouring masterbatch was added to obtain a wood-like appearance suitable for outdoor applications.

Throughout the paper, PA and RH refer to the mass fractions (wt.%) of PolyAl and rice husk, respectively.

2.2. Composite Formulations

Four formulations were selected to cover a realistic range of RH contents while maintaining processability in extrusion and compression moulding. The compositions are summarised below:

Table 1.

Composite formulations (mass fractions in wt.%).

Table 1.

Composite formulations (mass fractions in wt.%).

| Formulation 1

|

PA (wt%) |

RT (wt%) |

| F1 |

80 |

20 |

| F2 |

70 |

30 |

| F3 |

57 |

43 |

| F4 |

50 |

50 |

2.3. Processing of Wood-Like Boards

Composite boards were produced by an industrial partner using a single-screw extrusion followed by compression moulding. PA pellets, ground RH, compatibilizer and colourant were first homogenised in a gravimetric mixer and fed into a conventional single-screw extruder. Inside the barrel, PA melted and wet the RH particles, generating a viscous composite melt under standard processing conditions for PA-based materials as defined by the partner.

The molten strand leaving the die was deposited into a pre-heated steel mould with an internal cross-section of approximately 108 × 36 mm and a length of up to 3 m. Once the cavity was filled, the mould was closed and placed in a hydraulic press, where the material was consolidated under pressure and then cooled under controlled conditions. After demoulding, continuous solid boards with wood-like colour and surface finish were obtained.

2.4. Specimen Preparation

Specimens for mechanical and physical testing were machined from the boards using standard woodworking tools. Full-section beams were cut along the extrusion direction for three-point bending tests, with typical dimensions of about 440 × 108 × 35 mm (length × width × thickness), constrained by the board geometry.

Rectangular plates were extracted from the board faces and further machined into tensile specimens with a reduced central gauge, following the general philosophy of dog-bone specimens used for plastics. Smaller prismatic pieces were prepared for density measurements, and irregular fragments were reserved for hardness, water-absorption and UV-ageing tests.

All specimens were labelled with their formulation code (F1–F4) and conditioned at laboratory ambient temperature and humidity for at least 48 h prior to testing. For each formulation and test, several specimens were used and mean values and standard deviations were calculated.

2.5. Mechanical Testing

Tensile tests were carried out in a universal testing machine under displacement control. Plate-based specimens were clamped with mechanical wedge grips. The procedure followed the general recommendations of UNE-EN ISO 527 for plastics, with adaptations in specimen geometry and test speed imposed by the available board thickness and equipment. Force–displacement data were recorded continuously until failure and converted into engineering stress–strain curves using the initial cross-sectional area and gauge length. True stress–strain curves were then obtained assuming negligible volume change in the plastic regime.

Flexural behaviour was characterised by three-point bending tests on full-section beams in the same universal testing machine. A simply supported configuration with a span of 400 mm was used, resulting in a span-to-thickness ratio of approximately 11:1 for the nominal board thickness. The procedure was inspired by UNE-EN ISO 178 for plastics but adapted to the actual beam geometry. At least one quasi-static loading rate was employed; the applied force and mid-span deflection were recorded to determine the flexural modulus and strength from the standard beam-bending relationships.

2.6. Physical and Durability Testing

Surface hardness was measured on small specimens cut from the board surfaces using a Shore D durometer mounted on a stand. The methodology was based on UNE-EN ISO 868. For each specimen, several readings were taken at different locations and averaged to obtain a representative hardness value; at least three specimens per formulation were tested.

Apparent density was determined on prismatic specimens by dry measurements. Mass was recorded using an analytical balance and dimensions were measured with a calliper. The procedure was inspired by UNE-EN ISO 1183.

Water absorption was evaluated on fragments obtained from cutting operations. Specimens were dried to constant mass, weighed and then immersed in water at room temperature. At selected exposure times (from hours to several days), specimens were removed, wiped to remove surface water and re-weighed. Water uptake was expressed as mass gain per unit exposed surface area. The protocol followed the philosophy of UNE-EN ISO 62 but with non-standard specimen shapes and an adapted immersion schedule.

Short-term UV ageing was studied by exposing small specimens to a low-pressure mercury lamp with a dominant wavelength of 254 nm. Groups of specimens were subjected to increasing exposure times. After each interval, Shore D hardness was measured using the same procedure as for unexposed material. The method provided a qualitative assessment of the influence of UV radiation on surface properties, in analogy with the concept of accelerated weathering in UNE-EN ISO 4892.

2.7. Microstructural Analysis and Constitutive Modelling

Microstructural observations were performed on polished cross-sections of selected specimens by optical microscopy. The analysis focused on RH particle dispersion, the presence of voids or defects and the apparent quality of the PA–RH interface. Representative images were used to support the interpretation of the mechanical and physical results.

True stress–strain curves obtained from tensile tests were fitted to three classical work-hardening laws: Hollomon, Swift and Voce [

18,

19,

20]. Nonlinear regression was applied to the plastic portion of the curves to identify the corresponding parameters for each formulation. These parameters were later used to compare the mechanical response of the PA–RH boards and to discuss the suitability of each constitutive law for design and numerical modelling of low-load structural elements made from the studied material.

3. Results

This section presents the experimental results obtained for the PA–RH boards, structured by type of test. First, the tensile and flexural responses are analysed together with the constitutive parameters identified from the true stress–strain curves. Then, the physical properties (hardness and apparent density) and water absorption behaviour are reported, followed by a brief assessment of short-term UV ageing and microstructural observations. Unless otherwise stated, reported values correspond to the mean of all tested specimens for each formulation, and the detailed numerical data are provided in the corresponding tables and figures.

3.1. Tensile Behaviour and Constitutive Parameters

The true stress–strain curves in tension for the four PA–RH boards are shown in the experimental and fitted plots, Hollomon and Voce. All compositions display a non-linear response from very low strain levels, with a short quasi-linear initial segment followed by a marked strain-hardening region up to fracture. Maximum true stresses are in the range of 8–10 MPa. Within this range, the 57PA–43RH board consistently reaches the highest stress levels over most of the strain interval, whereas 80PA–20RH shows the lowest tensile strength; 50PA–50RH and 70PA–30RH exhibit intermediate behaviour. The scatter between specimens of the same composition is moderate, indicating acceptable reproducibility of the manufacturing process.

The experimental curves were first fitted to the Hollomon law:

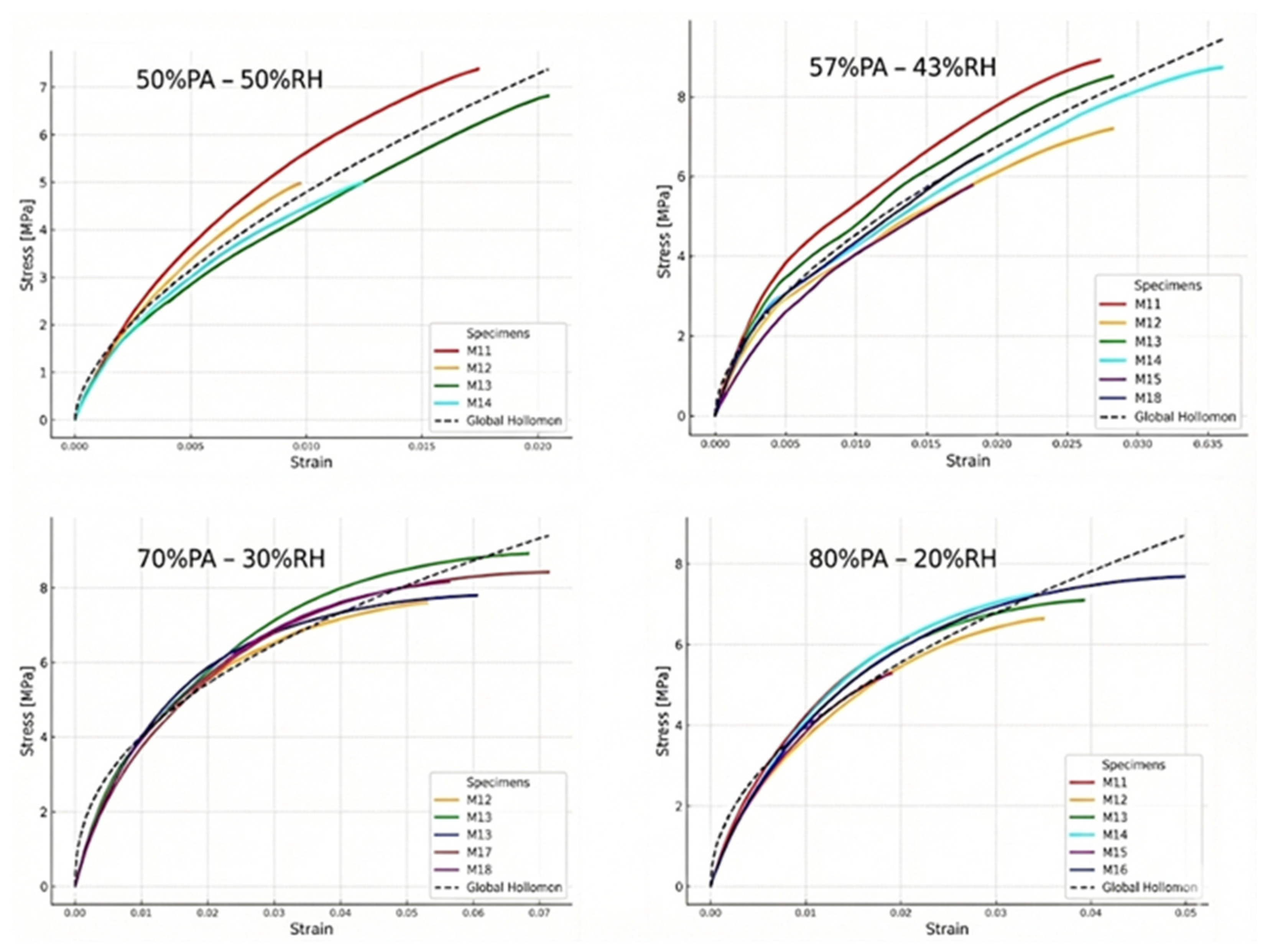

using true stress σ and true strain ε. The global parameters obtained for each formulation (refer to

Table 2) show strength coefficients K between 29.29 and 76.85 MPa and strain-hardening exponents n between 0.43 and 0.60. The highest K and n values correspond to 50PA–50RH, followed by 57PA–43RH, while 70PA–30RH presents the lowest values; 80PA–20RH partially recovers both K and n. In all cases, the determination coefficients R

2 lie between 0.94 and 0.97, confirming that this simple power law reproduces the overall curvature of the tensile response, although it cannot represent the gradual saturation observed at larger strains.

After fitting the global Hollomon parameters, the experimental true stress–strain curves for all tensile specimens were compared with the corresponding model predictions.

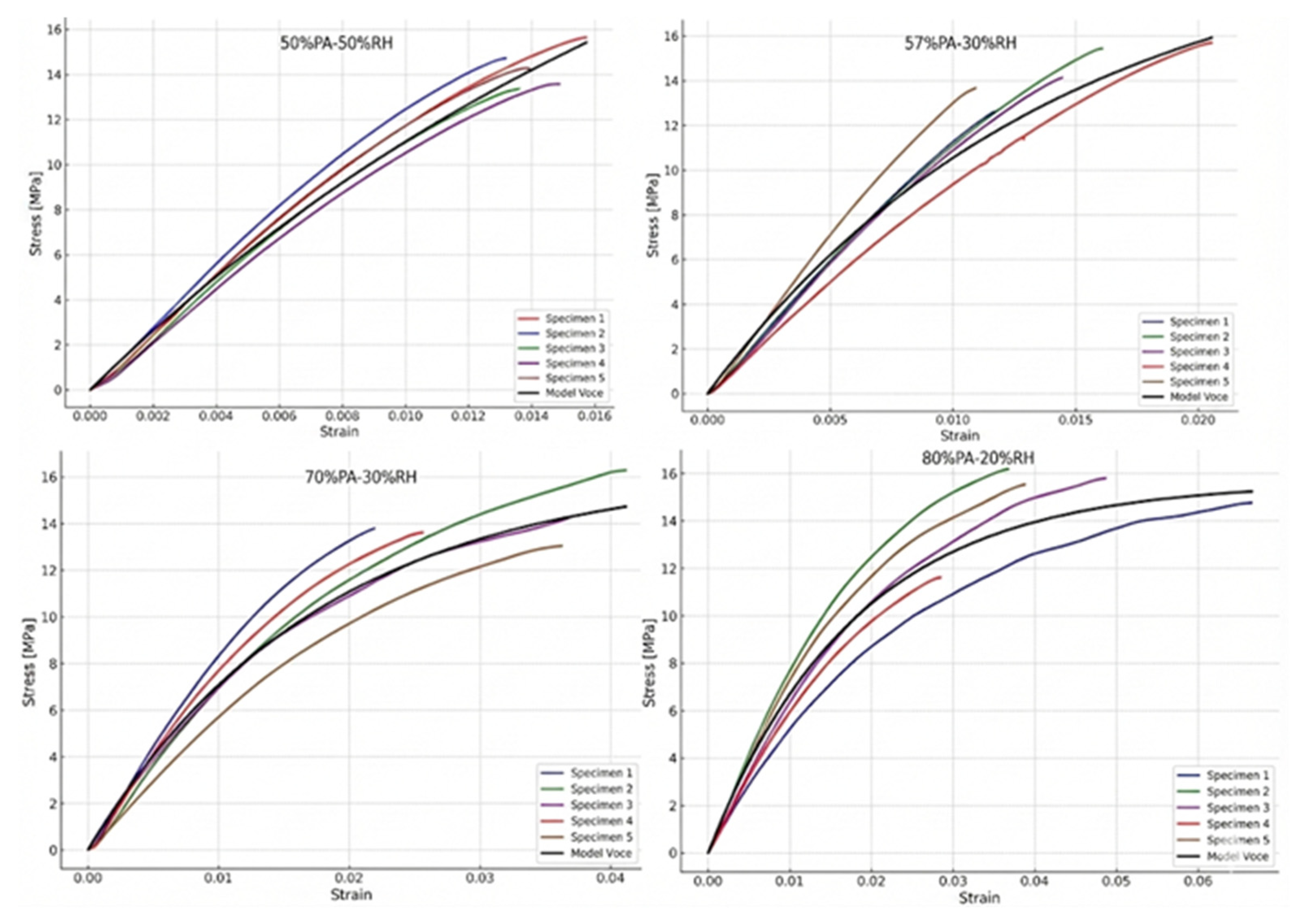

Figure 1 shows, for each PA–RH board, the individual tensile curves and the global Hollomon fit, illustrating both the scatter between specimens and the ability of the power law to reproduce the overall shape of the response.

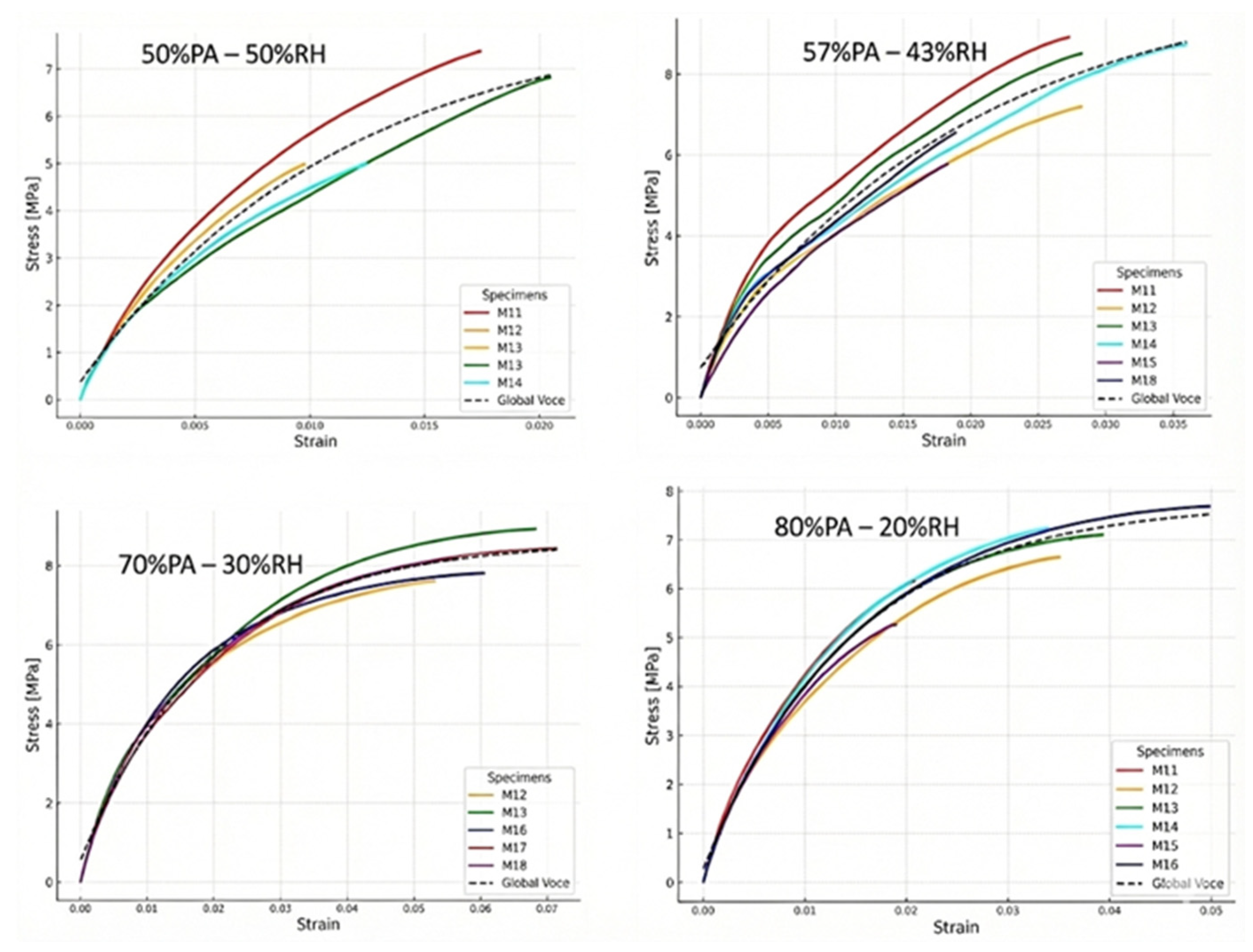

To capture this saturation effect, the Voce law was also applied:

where σ

0 is the initial flow stress, σ

s the saturation stress and c a material constant. The resulting global parameters for each composite are summarised in

Table 3. Saturation stresses σ

s range from 7.76 MPa (80PA–20RH) to 10.36 MPa (57PA–43RH), in agreement with the ranking observed in the experimental curves. The parameter c takes values between 50.5 and 88.0, reflecting different rates of approach to saturation. The coefficients of determination R

2 are between 0.94 and 0.99 and are systematically equal to or higher than those of the Hollomon fits, while the global Voce curves closely follow the envelopes of the experimental data for all formulations. On this basis, the Voce model is selected as the reference constitutive law for subsequent analysis of the tensile behaviour of the PA–RH boards.

After identifying the global Voce parameters, the experimental true stress–strain curves of all tensile specimens were compared with the corresponding model predictions.

Figure 2 shows, for each PA–RH board, the individual tensile curves together with the global Voce fit, illustrating both the experimental scatter and the ability of the Voce law to reproduce the nonlinear hardening behaviour up to saturation.

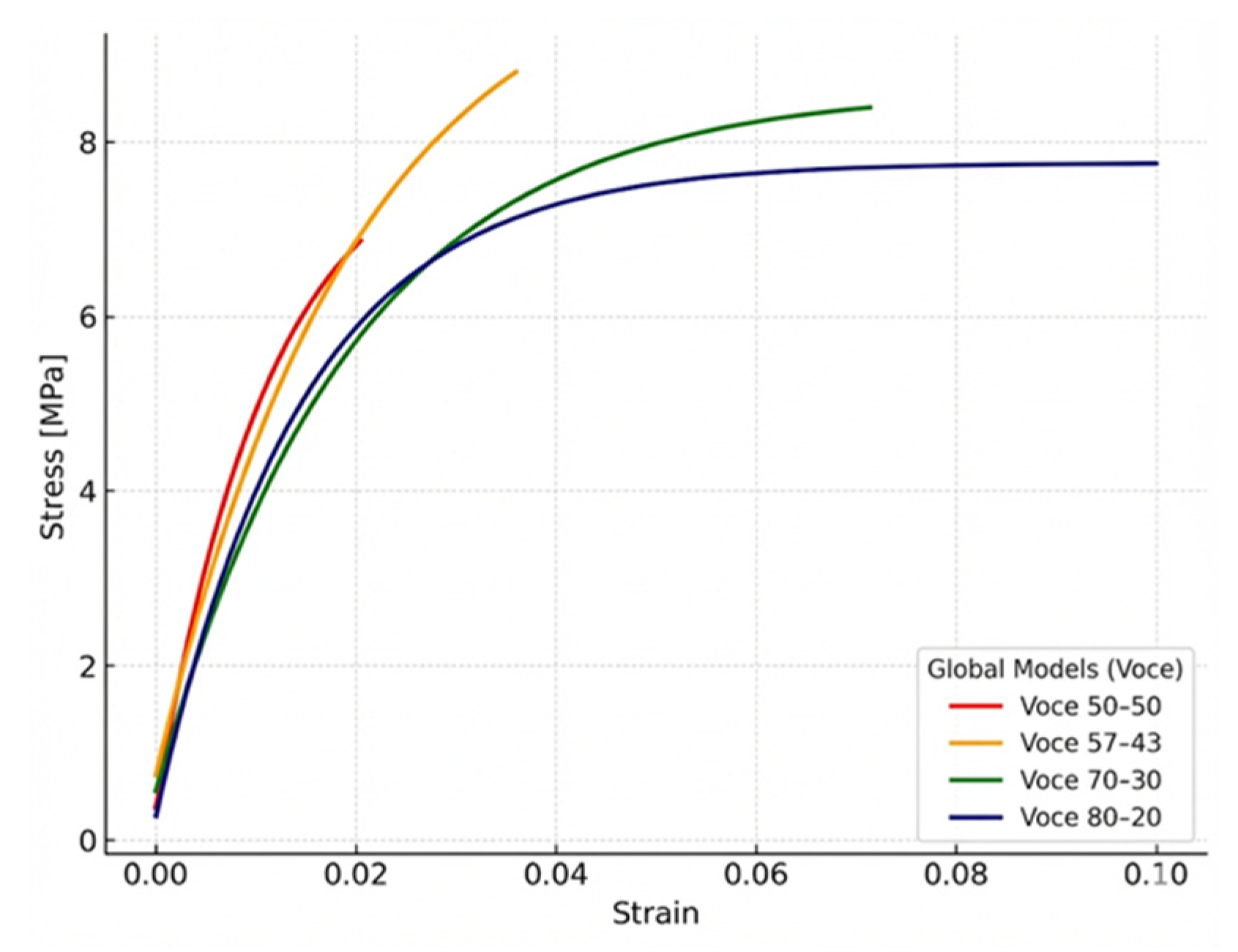

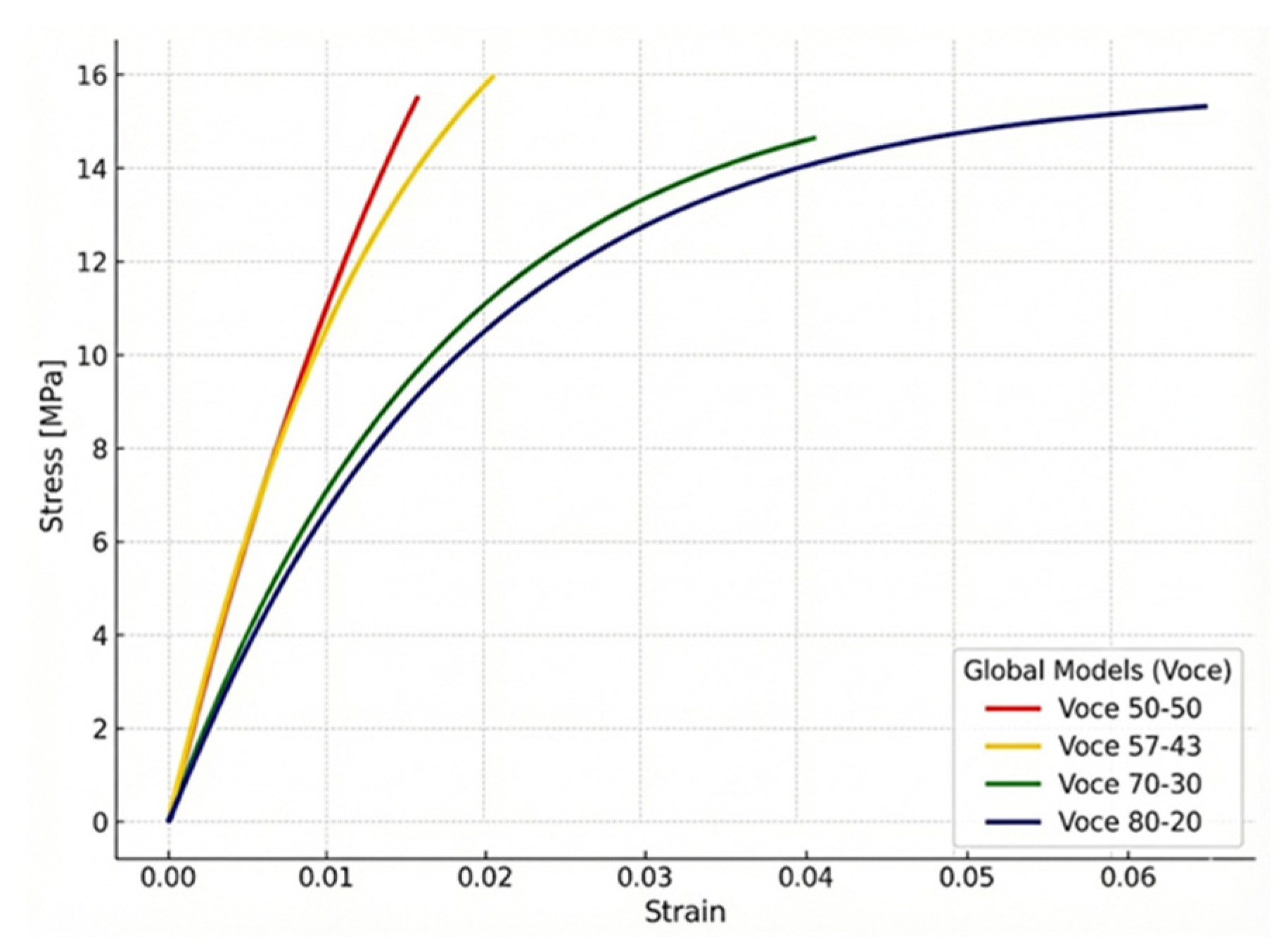

To provide an overall comparison between formulations, the four global Voce curves were plotted together in a single graph.

Figure 3 summarises the fitted tensile behaviour of the PA–RH boards, highlighting the differences in stress level and hardening rate associated with the PA/RH ratio.

3.2. Bending Behaviour and Constitutive Parameters

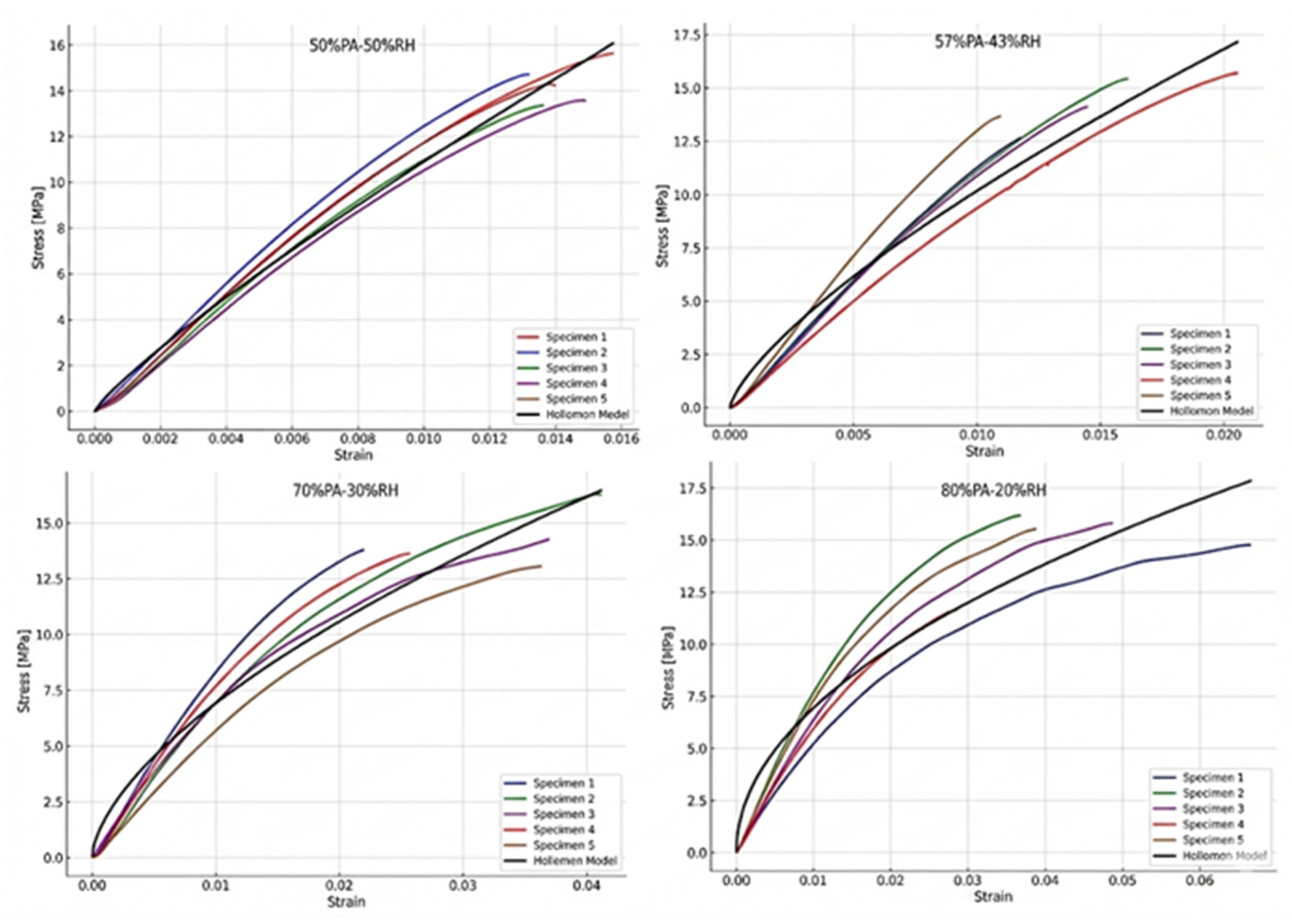

Three-point bending tests were carried out on full-section beams to characterise the flexural response of the PA–RH boards. True flexural stress–strain curves were derived from the force–deflection data and used to identify the parameters of the Hollomon and Voce work-hardening laws (Equations (1) and (2)), following the same procedure as in tension.

The flexural curves were first fitted using the Hollomon law (Equation (1)). The global parameters obtained for each formulation are summarised in

Table 4. The strength coefficient K shows a clear decreasing trend from approximately 665 MPa for 50PA–50RH down to about 70 MPa for 80PA–20RH, while the strain-hardening exponent n decreases from around 0.90 to 0.51. The coefficients of determination R

2 remain relatively high (between 0.86 and 0.98), indicating that the Hollomon law provides a reasonable description of the overall flexural hardening behaviour of the boards.

After fitting the global Hollomon parameters, the experimental true flexural stress–strain curves for all specimens were compared with the corresponding model predictions.

Figure 4 shows, for each formulation, the individual flexural curves together with the global Hollomon fit, illustrating both the experimental scatter and the capability of the power law to reproduce the main features of the response.

To better capture the saturation tendency observed at higher flexural strains, the same curves were fitted using the Voce law (Equation (2)). The corresponding parameters are listed in

Table 5. The saturation stress σs decreases from about 38 MPa for 50PA–50RH to roughly 16 MPa for 80PA–20RH, in line with the reduction of apparent flexural strength as the PA content increases. The initial stress σ0 is practically negligible in all cases, and the parameter c takes values between approximately 33 and 64, controlling how quickly the curves approach σs. The Voce fits yield R

2 values between about 0.92 and 0.98, systematically higher than those obtained with the Hollomon model.

Figure 5 illustrates the agreement between the experimental flexural data and the Voce predictions for each formulation. The model closely follows the non-linear hardening over the whole strain range, particularly in the high-strain region. For design and comparative purposes, the four global Voce curves are finally plotted together in

Figure 6, providing a compact summary of the flexural response of the PA–RH boards as a function of composition. In view of the higher average R

2 and its ability to reproduce the saturation behaviour, the Voce law is selected as the preferred constitutive model in bending.

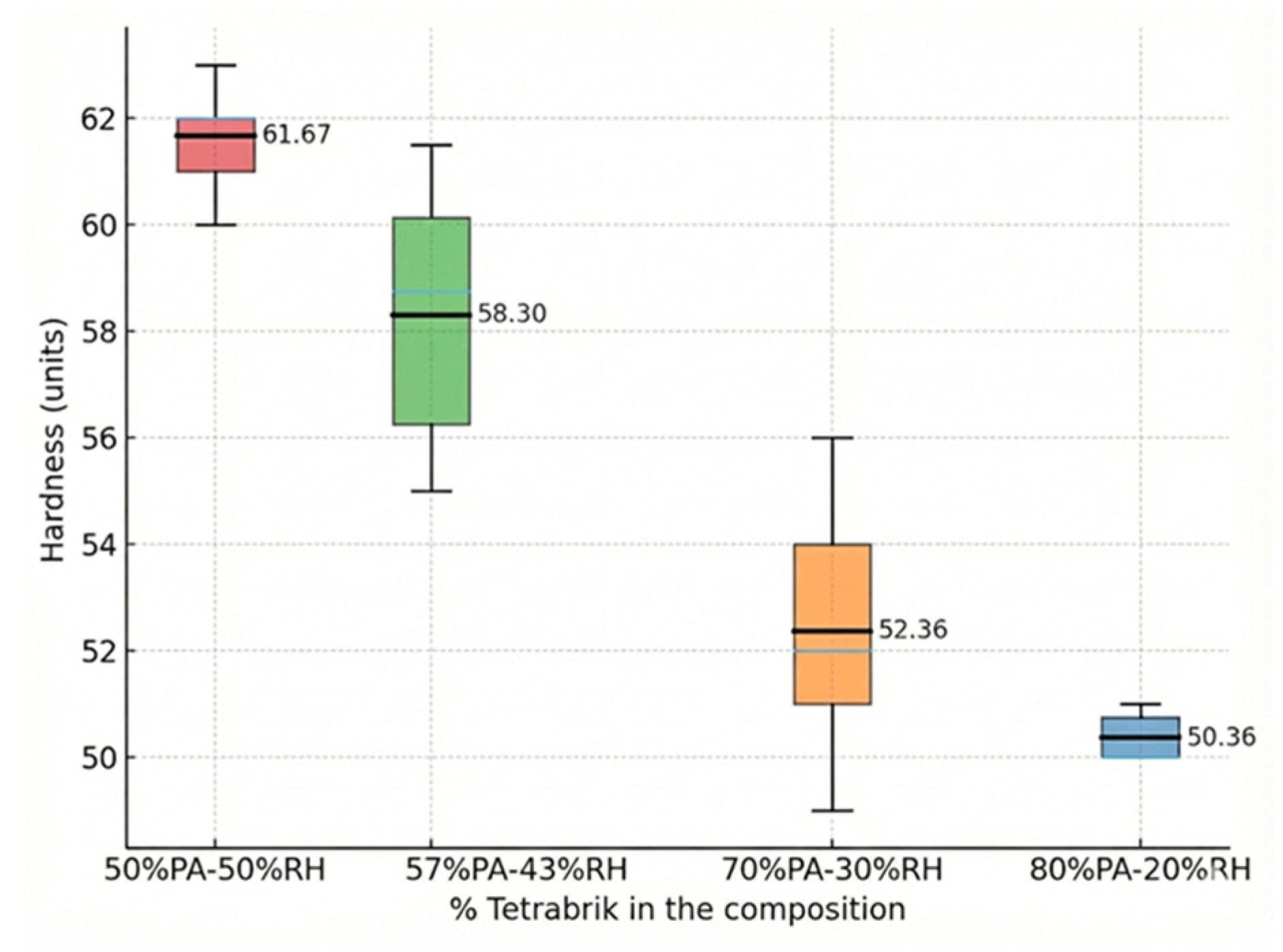

3.3. Surface Hardness

Shore D hardness in dry condition was measured on all PA–RH boards. The descriptive statistics for each formulation are summarised in

Table 6, including number of specimens, mean value, standard deviation and minimum/maximum hardness. The highest average hardness was obtained for the 50PA–50RH board (≈61.67 Shore D), followed by 57PA–43RH (≈58.30). The 70PA–30RH and 80PA–20RH formulations showed lower mean values, around 52.36 and 50.36, respectively. Standard deviations remained modest in all cases, which indicates a good reproducibility of the hardness measurements.

The distribution of hardness values is illustrated in

Figure 7 by means of box-and-whisker plots. For each composition, the median hardness is highlighted by a black line inside the box, and the numerical mean is plotted next to it. This representation makes it possible to visualise both intra-composition variability and the systematic decrease in hardness as the PA (Tetrabrik) content increases and the RH fraction is reduced.

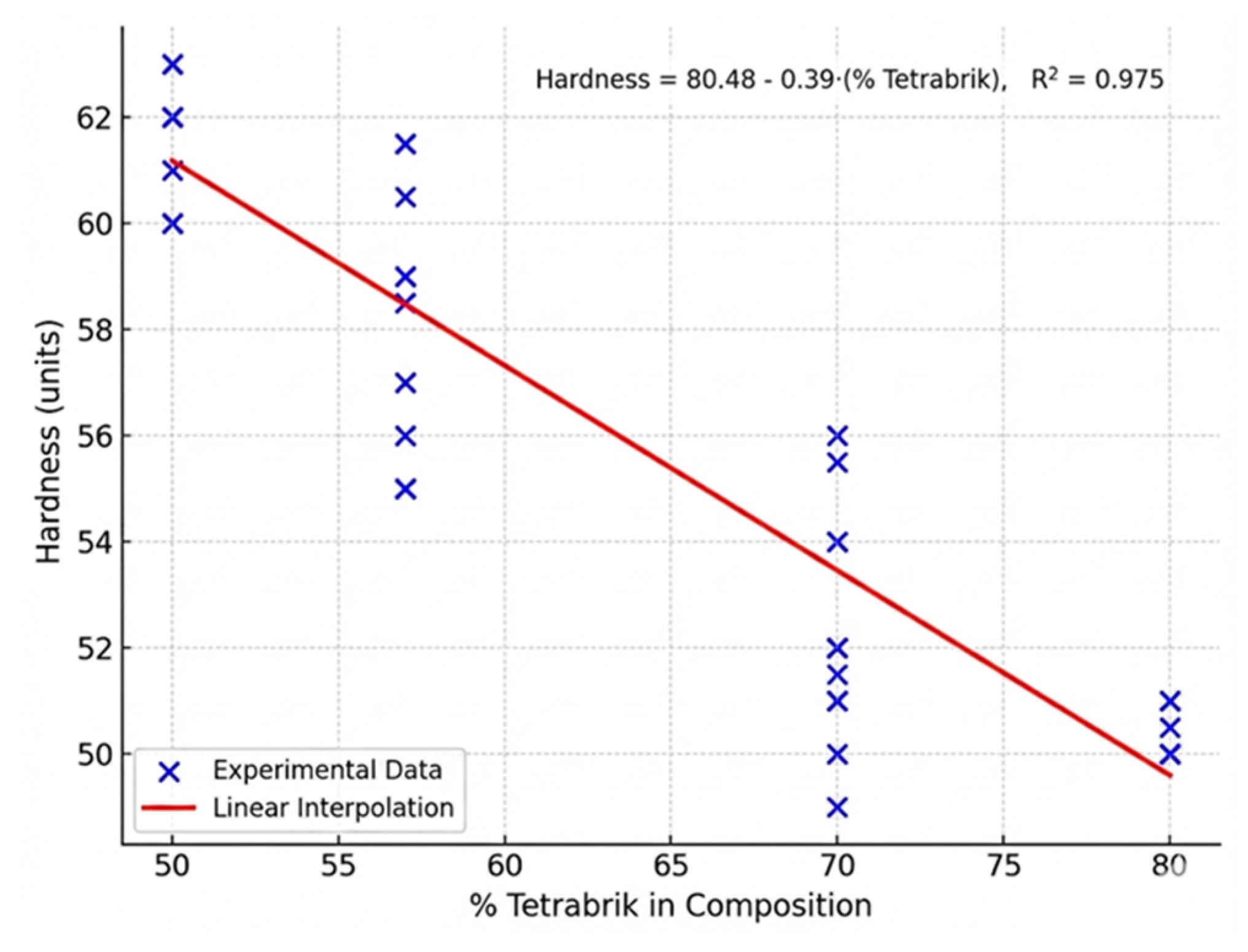

The relationship between hardness and formulation was further quantified by a linear regression of the mean hardness against the PA content, expressed as Tetrabrik percentage in the mixture (

Figure 8). The experimental data show a clear decreasing trend, which is well described by the regression line,

The equation representing this trend being:

this result indicates that each 1 wt.% increase in Tetrabrik content leads, on average, to a reduction of about 0.39 Shore D units in surface hardness within the studied composition range.

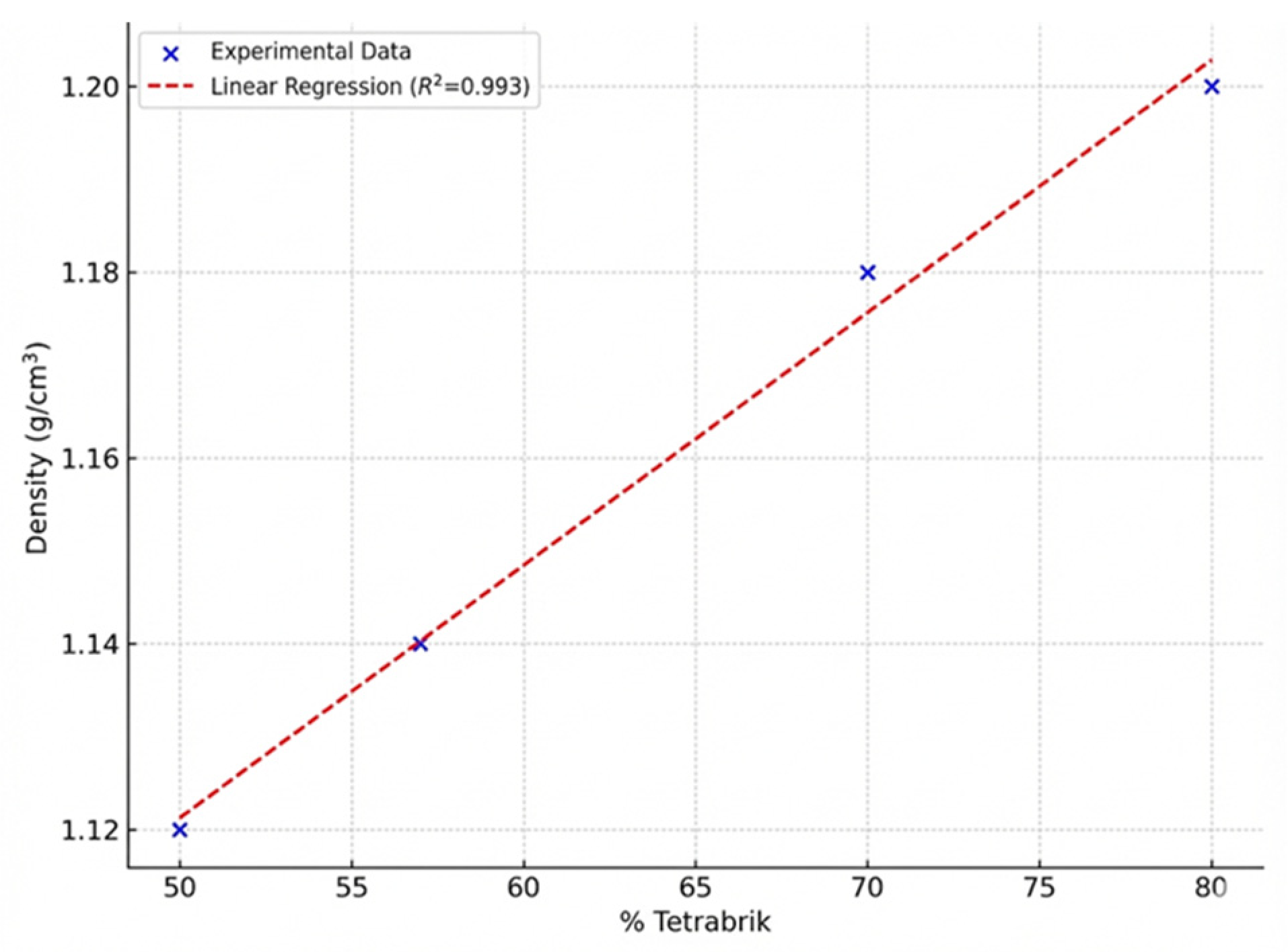

3.4. Apparent Density

Apparent density was determined for all PA–RH boards using prismatic specimens cut from the moulded panels.

Figure 9 shows the evolution of density as a function of PA content. A clear increasing trend is observed, from approximately 1.12 g·cm

−3 for the 50PA–50RH composite to about 1.20 g·cm

−3 for 80PA–20RH, with intermediate values around 1.14 g·cm

−3 and 1.18 g·cm

−3 for the 57PA–43RH and 70PA–30RH formulations.

The linear regression of density versus PA percentage yields a high coefficient of determination (R

2 = 0.993), confirming the strong correlation between both variables. The fitted relationship can be expressed as:

within the composition range considered in this study.

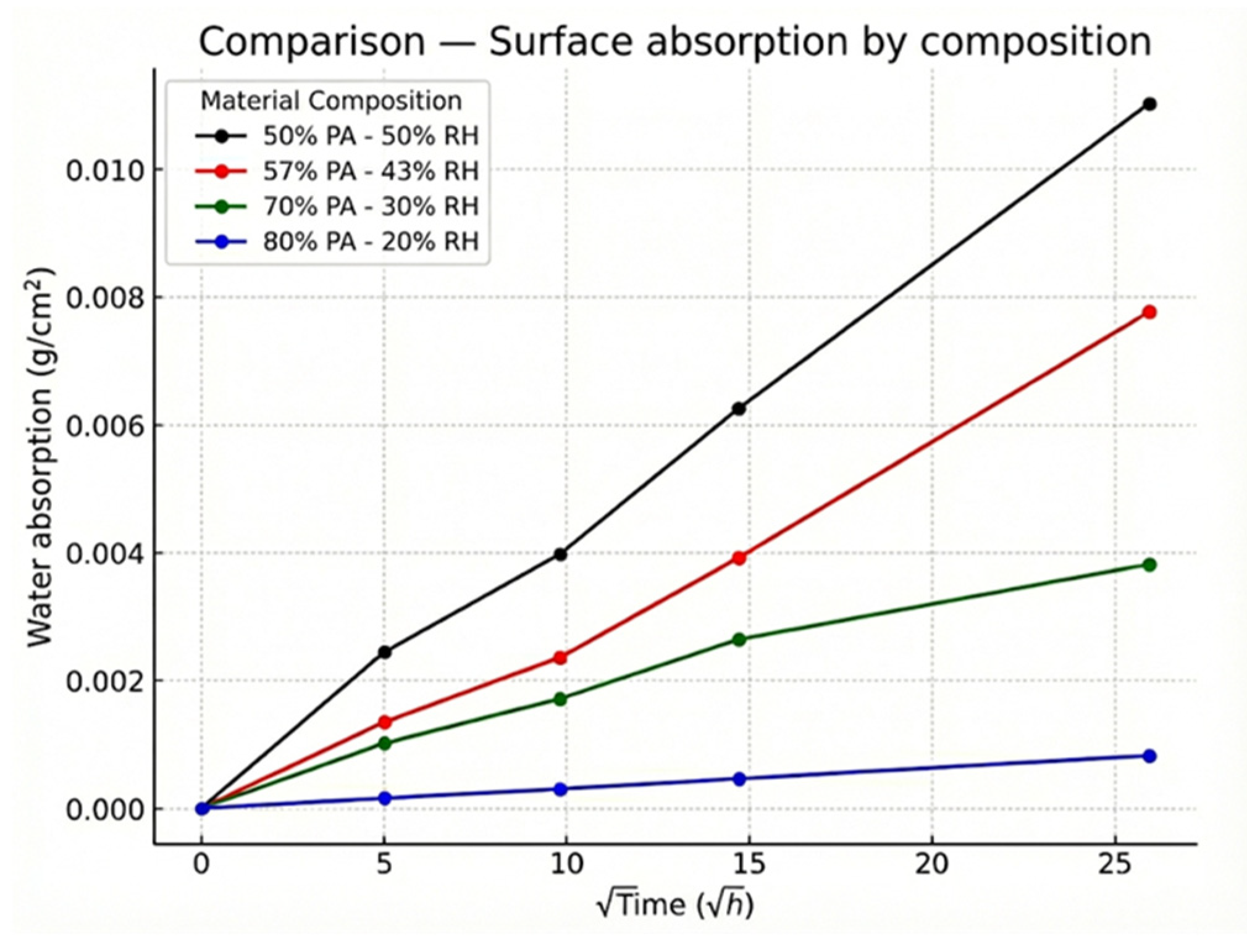

3.5. Water Absorption

Water absorption tests were performed on all PA–RH boards by monitoring the normalised mass gain per exposed surface area as a function of the square root of immersion time. The mean curves for each formulation are compared in

Figure 10. All compositions exhibit an initial quasi-linear increase of absorbed water versus √t, consistent with a diffusion-controlled surface mechanism, followed by a gradual approach towards a quasi-steady state as immersion time increases.

A clear dependence on composition is observed. The 50PA–50RH and 57PA–43RH boards show the highest absorption rates and final uptake levels, whereas the 80PA–20RH composite exhibits the lowest values throughout the test, confirming the beneficial effect of a higher PA fraction on resistance to moisture ingress. The 70PA–30RH formulation displays intermediate behaviour, with noticeably lower water uptake than the more RH-rich boards while still retaining a significant bio-based content. Normalisation by exposed surface area removes geometric effects between specimens, enabling a consistent comparison among the four materials. Within the range studied, 70PA–30RH appears as a reasonable compromise between stiffness (

Section 3.1 and

Section 3.2) and water resistance.

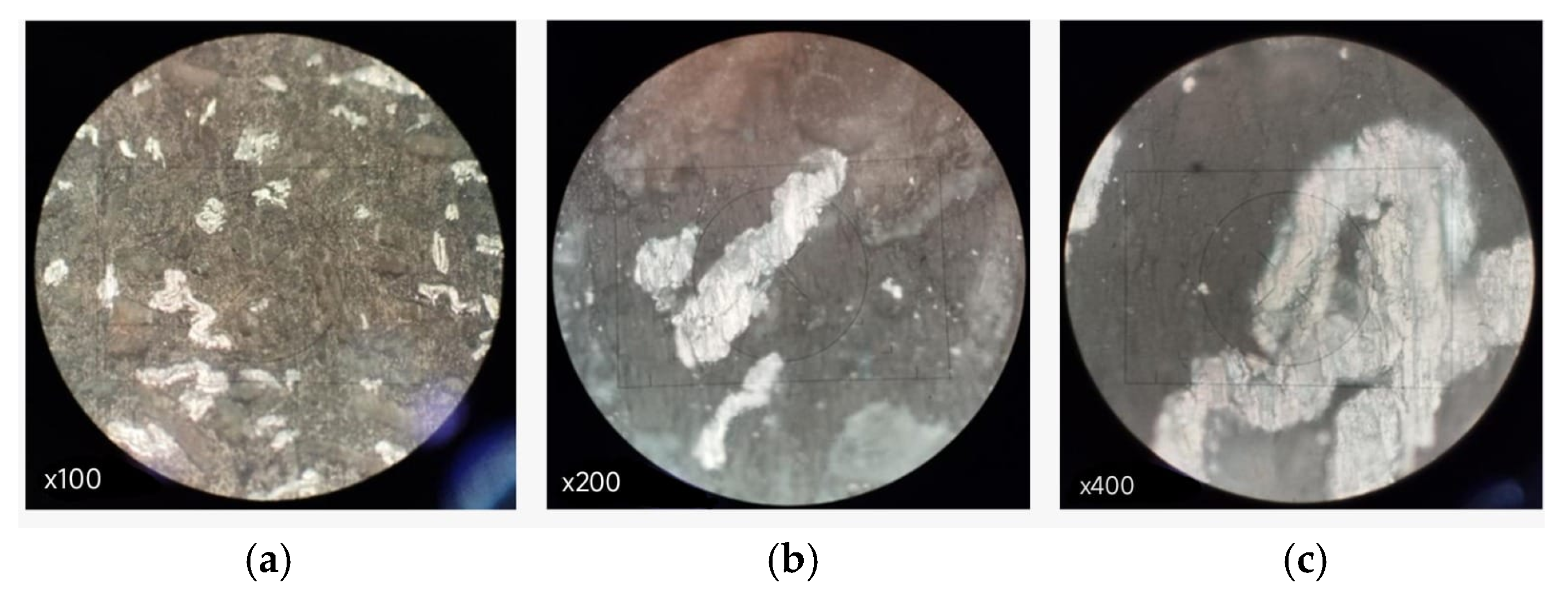

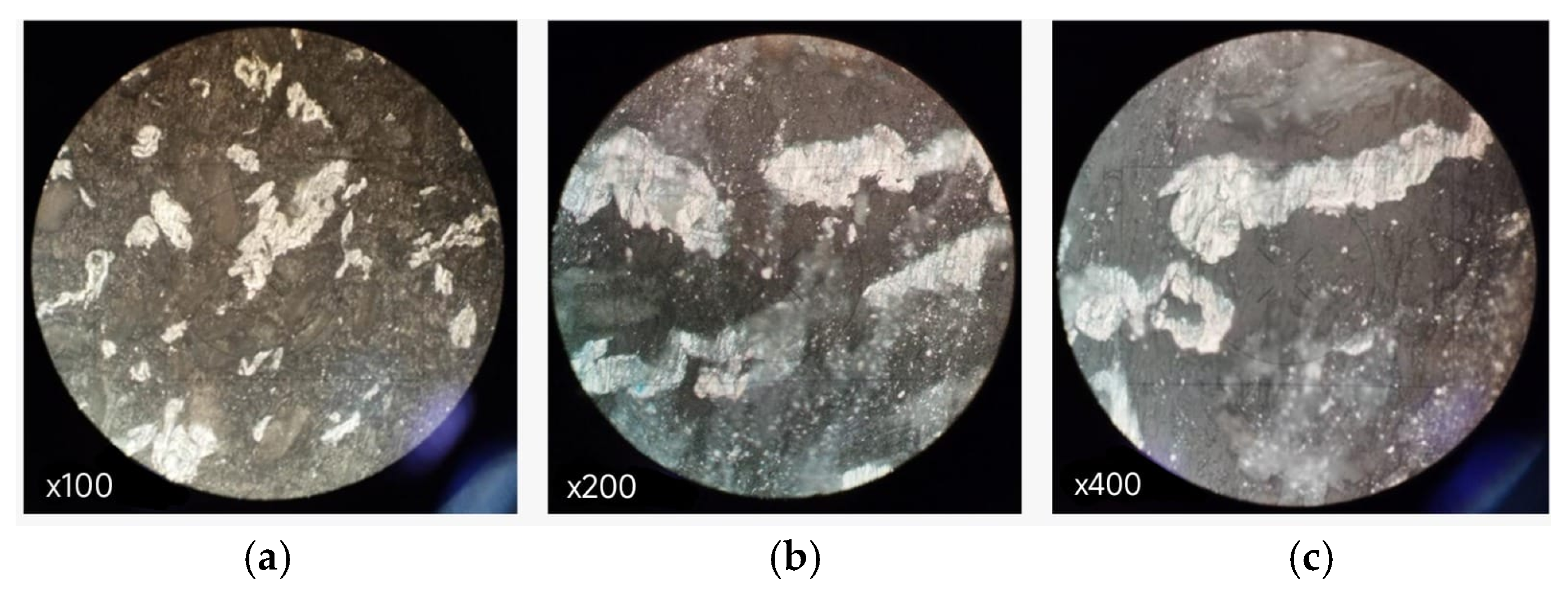

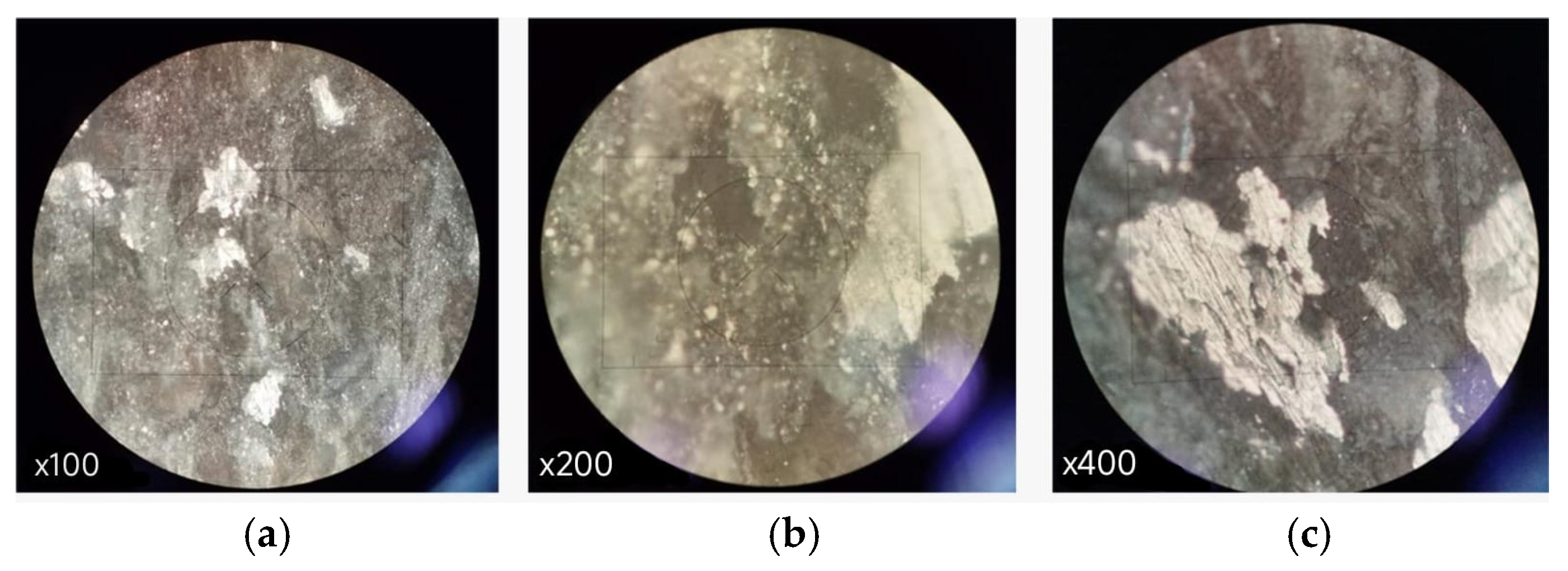

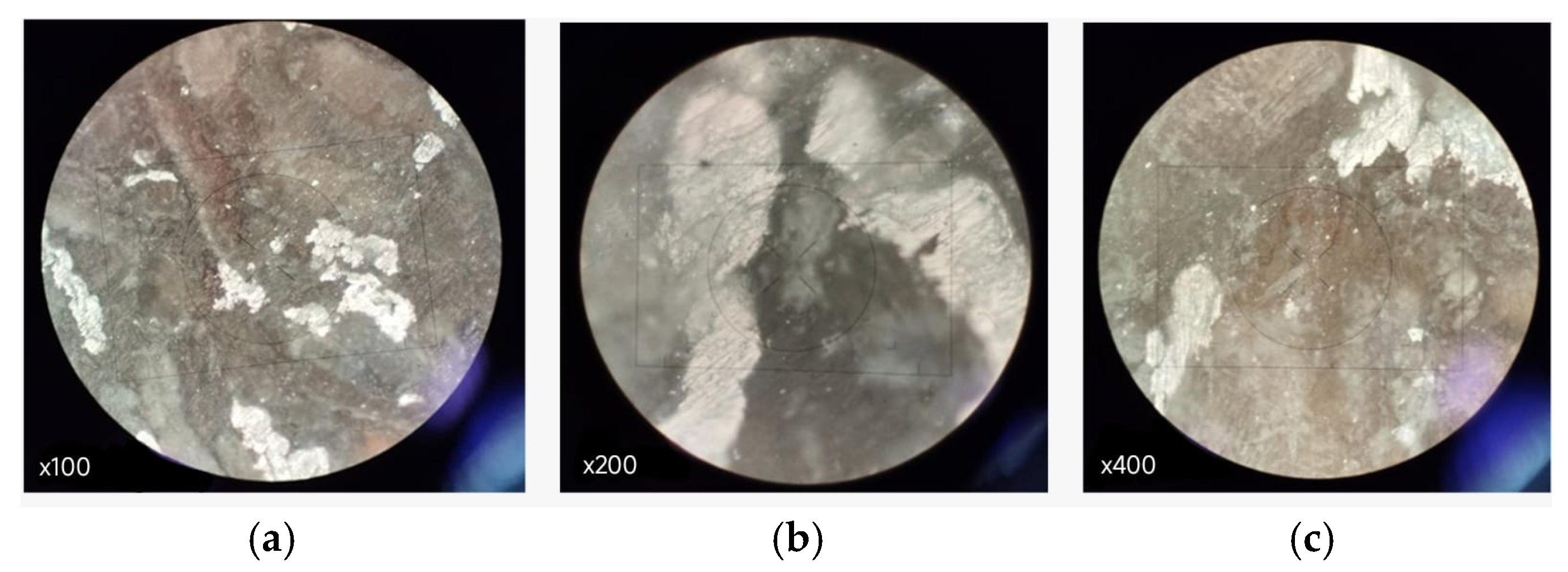

3.6. Microstructural Observations

Representative optical micrographs of the PA–RH boards are shown in

Figure 11,

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14. The bright regions correspond to PolyAl-rich domains containing aluminium foil fragments, whereas the darker background is associated with the polymeric matrix and the lignocellulosic filler. In all formulations, PolyAl particles appear as irregular clusters with variable size, and their spatial distribution is clearly non-uniform, with zones of higher and lower particle density.

Within these qualitative pictures, the boards with higher PA content tend to exhibit larger PolyAl-rich agglomerates and more pronounced local heterogeneities, while the more RH-rich formulations show a slightly finer dispersion. Due to the absence of metallographic etching and the optical contrast limitations, individual rice husk particles cannot be clearly distinguished from the surrounding matrix, and a quantitative assessment of porosity or interfacial defects is not possible with the present images. Nevertheless, these observations support the interpretation that microstructural heterogeneity and the distribution of PolyAl-rich domains are likely to influence the tensile and flexural behaviour of the boards discussed in

Section 3.1 and

Section 3.2.

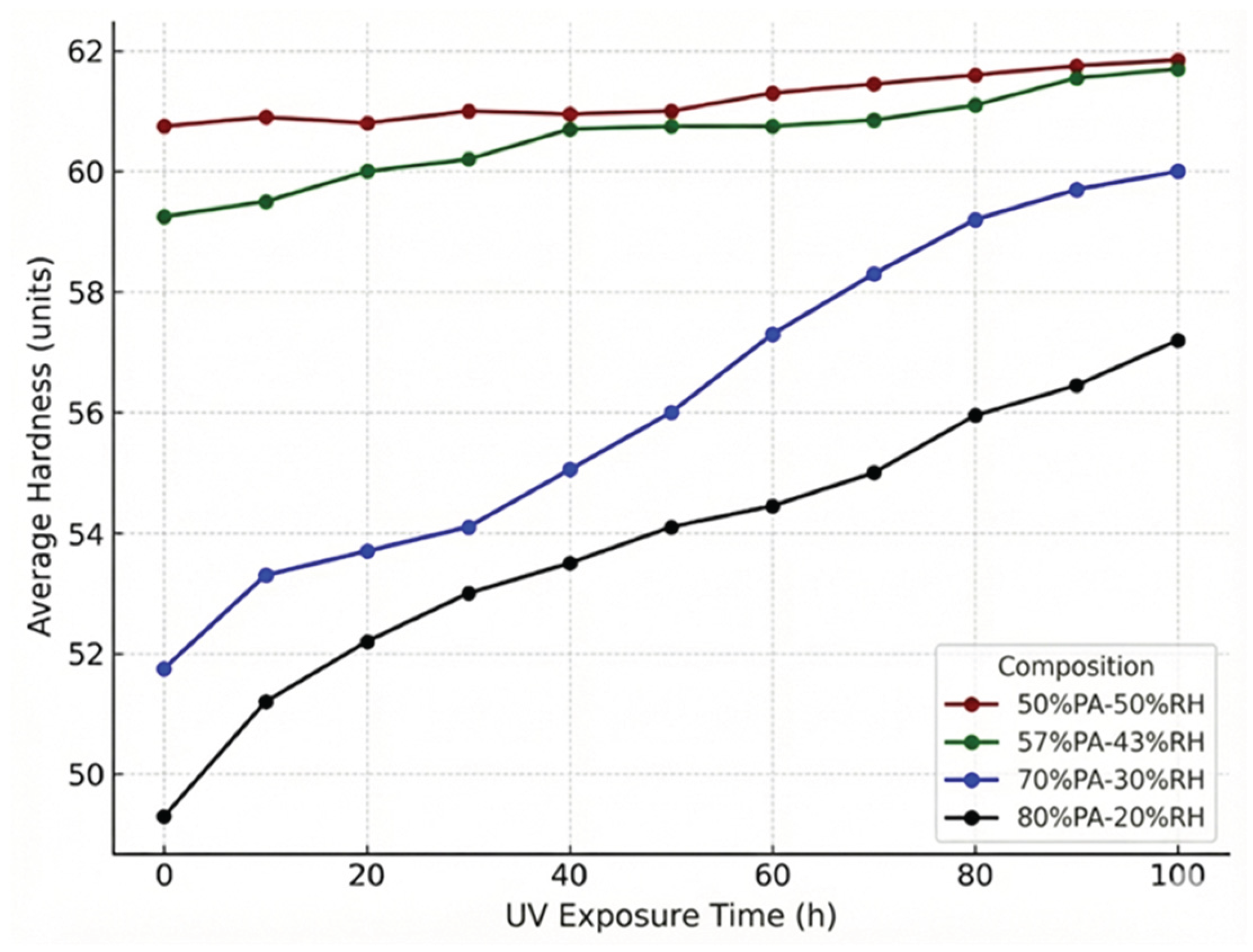

3.7. UV Ageing

The evolution of surface hardness under UV exposure was monitored for all PA–RH boards up to 100 h (test conditions described in

Section 2).

Figure 15 shows the mean Shore D hardness of each formulation as a function of exposure time. All composites exhibit a progressive increase in hardness with irradiation time, without abrupt changes or signs of surface degradation during the test window.

Formulations with higher RH content start from the highest initial hardness levels. The 50PA–50RH board increases from about 60.7 to 61.9 Shore D between 0 and 100 h, while 57PA–43RH evolves from roughly 59.3 to 61.1 Shore D with very small variations throughout the test. In contrast, the 70PA–30RH and 80PA–20RH boards begin from lower hardness values (≈50.5 and ≈49.5 Shore D, respectively) and show a more pronounced hardening, reaching about 61 and 56–57 Shore D after 100 h. Overall, all four formulations present a moderate increase in surface hardness under the applied UV conditions, with final values that tend to converge towards a relatively narrow range, which suggests that short-term UV exposure does not impair the mechanical performance of the boards.

5. Conclusions

This work characterised recycled PA–RH composite boards manufactured by extrusion and compression moulding for low-load structural applications. The main findings are:

1. All formulations show densities and flexural properties comparable to commercial wood–plastic composites and Tetra Pak–based boards, confirming their suitability for urban furniture and decking-type uses.

2. The Voce law provides the most accurate description of the tensile and flexural stress–strain curves, offering a compact constitutive model for design and numerical simulations.

3. Increasing the rice husk fraction enhances stiffness and surface hardness but increases water uptake, whereas PolyAl-rich boards show lower hardness but improved moisture resistance; the 70PA–30RH formulation offers the best overall compromise.

4. Water absorption remains within the range reported for other Tetra Pak composites, and short-term UV exposure leads to moderate surface hardening without visible degradation, indicating promising initial durability.

5. By jointly valorising beverage carton PolyAl and rice husk residues, these boards illustrate a viable industrial-symbiosis route that supports circular-economy and sustainability objectives, although long-term outdoor ageing and microstructural optimisation should be addressed in future work.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A. Perez Puig., Oscar Loriente.; methodology, Alba Loriente Lujan.; validation, M.A. Perez Puig., Fidel Salas., Oscar Loriente., Alba Loriente Lujan.; formal analysis, Alba Loriente Lujan.; investigation, Alba Loriente Lujan.; resources, data curation, Alba Loriente Lujan.; writing—original draft preparation, Alba Loriente Lujan.; writing—review and editing, Alba Loriente Lujan.; visualization, M.A. Perez Puig., Fidel Salas., Oscar Loriente.; supervision, M. A. Perez Puig., Fidel Salas., Oscar Loriente.; project administration, M. A. Perez Puig., Fidel Salas., Oscar Loriente.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Figure 1.

True tensile stress–strain Hollomon curves for the PA–RH boards.

Figure 1.

True tensile stress–strain Hollomon curves for the PA–RH boards.

Figure 2.

True tensile stress–strain Voce curves for the PA–RH boards.

Figure 2.

True tensile stress–strain Voce curves for the PA–RH boards.

Figure 3.

Global Voce tensile stress-strain curves for the four PA-RH formulations.

Figure 3.

Global Voce tensile stress-strain curves for the four PA-RH formulations.

Figure 4.

Comparison between experimental flexural stress-strain curves and global Hollomon fits for the four PA-RH formulations.

Figure 4.

Comparison between experimental flexural stress-strain curves and global Hollomon fits for the four PA-RH formulations.

Figure 5.

Experimental flexural stress-strain curves and corresponding Voce fits for the four PA-RH formulations.

Figure 5.

Experimental flexural stress-strain curves and corresponding Voce fits for the four PA-RH formulations.

Figure 6.

Global Voce flexural stress-strain curves for the four formulations, obtained from the fitted parameters.

Figure 6.

Global Voce flexural stress-strain curves for the four formulations, obtained from the fitted parameters.

Figure 7.

Box-and-whisker representation of Shore D hardness by formulation.

Figure 7.

Box-and-whisker representation of Shore D hardness by formulation.

Figure 8.

Relationship between Shore D hardness and Tetrabrik (PA) content in the composites, with linear regression fit.

Figure 8.

Relationship between Shore D hardness and Tetrabrik (PA) content in the composites, with linear regression fit.

Figure 9.

Apparent density as function of PA content, with linear regression fit (R2 = 0.993).

Figure 9.

Apparent density as function of PA content, with linear regression fit (R2 = 0.993).

Figure 10.

Normalised surface water absorption as a function of the square root of immersion time.

Figure 10.

Normalised surface water absorption as a function of the square root of immersion time.

Figure 11.

Representative optical micrographs of the 80PA–20RH composite: (a) overview of the microstructure at 100×; (b) detail of PolyAl-rich domains and surrounding matrix at 200×; (c) close-up of PolyAl clusters and neighbouring regions at 400×.

Figure 11.

Representative optical micrographs of the 80PA–20RH composite: (a) overview of the microstructure at 100×; (b) detail of PolyAl-rich domains and surrounding matrix at 200×; (c) close-up of PolyAl clusters and neighbouring regions at 400×.

Figure 12.

Representative optical micrographs of the 70PA–30RH composite: (a) overview of the microstructure at 100×; (b) detail of PolyAl-rich domains and surrounding matrix at 200×; (c) close-up of PolyAl clusters and neighbouring regions at 400×.

Figure 12.

Representative optical micrographs of the 70PA–30RH composite: (a) overview of the microstructure at 100×; (b) detail of PolyAl-rich domains and surrounding matrix at 200×; (c) close-up of PolyAl clusters and neighbouring regions at 400×.

Figure 13.

Representative optical micrographs of the 57PA–43RH composite: (a) overview of the microstructure at 100×; (b) detail of PolyAl-rich domains and surrounding matrix at 200×; (c) close-up of PolyAl clusters and neighbouring regions at 400×.

Figure 13.

Representative optical micrographs of the 57PA–43RH composite: (a) overview of the microstructure at 100×; (b) detail of PolyAl-rich domains and surrounding matrix at 200×; (c) close-up of PolyAl clusters and neighbouring regions at 400×.

Figure 14.

Representative optical micrographs of the 50PA–50RH composite: (a) overview of the microstructure at 100×; (b) detail of PolyAl-rich domains and surrounding matrix at 200×; (c) close-up of PolyAl clusters and neighbouring regions at 400×.

Figure 14.

Representative optical micrographs of the 50PA–50RH composite: (a) overview of the microstructure at 100×; (b) detail of PolyAl-rich domains and surrounding matrix at 200×; (c) close-up of PolyAl clusters and neighbouring regions at 400×.

Figure 15.

Evolution of mean Shore D surface hardness as a function of UV exposure time.

Figure 15.

Evolution of mean Shore D surface hardness as a function of UV exposure time.

Table 2.

Hollomon parameters for the tensile true stress-strain curves of the PA-RH composites.

Table 2.

Hollomon parameters for the tensile true stress-strain curves of the PA-RH composites.

| Formulation |

k (-) |

n (-) |

R2

|

| 50PA–50RH |

76.853 |

0.6027 |

0.9456 |

| 57PA–43RH |

62.409 |

0.5687 |

0.9404 |

| 70PA–30RH |

29.290 |

0.4303 |

0.9638 |

| 80PA–20RH |

38.159 |

0.4929 |

0.9655 |

Table 3.

Voce parameters for the tensile true stress-strain curves of the PA-RH composites.

Table 3.

Voce parameters for the tensile true stress-strain curves of the PA-RH composites.

| Formulation |

σs (MPa) |

σ0 (MPa) |

c (-) |

R2

|

| 50PA–50RH |

8.152 |

0.370 |

88.005 |

0.9466 |

| 57PA–43RH |

10.359 |

0.741 |

50.525 |

0.9386 |

| 70PA–30RH |

8.600 |

0.563 |

51.214 |

0.9857 |

| 80PA–20RH |

7.760 |

0.275 |

68.799 |

0.9888 |

Table 4.

Hollomon parameters for the three-point bending tests on PA–RH composites.

Table 4.

Hollomon parameters for the three-point bending tests on PA–RH composites.

| Formulation |

k (-) |

n (-) |

R2

|

| 50PA–50RH |

664.725 |

0.8988 |

0.9798 |

| 57PA–43RH |

310.686 |

0.7497 |

0.9242 |

| 70PA–30RH |

117.109 |

0.6153 |

0.9280 |

| 80PA–20RH |

70.262 |

0.5061 |

0.8590 |

Table 5.

Voce parameters identified from flexural tests on PA-RH composites.

Table 5.

Voce parameters identified from flexural tests on PA-RH composites.

| Formulation |

σs (MPa) |

σ0 (MPa) |

c (-) |

R2

|

| 50PA–50RH |

37.9098 |

<0.1 |

33.1422 |

0.983658 |

| 57PA–43RH |

21.631 |

<0.1 |

63.7753 |

0.941396 |

| 70PA–30RH |

16.3421 |

<0.1 |

56.26 |

0.951323 |

| 80PA–20RH |

15.7087 |

<0.1 |

54.2198 |

0.922698 |

Table 6.

Descriptive statistics of Shore D hardness for each formulation.

Table 6.

Descriptive statistics of Shore D hardness for each formulation.

| Formulation |

N |

Mean

hardness, μ |

Standard

deviation, σ |

Minimum |

Maximum |

| 50PA–50RH |

9 |

61.67 |

1.12 |

60.0 |

63.0 |

| 57PA–43RH |

10 |

58.30 |

3.39 |

55.0 |

61.5 |

| 70PA–30RH |

10 |

52.36 |

2.24 |

49.0 |

56.0 |

| 80PA–20RH |

7 |

50.36 |

0.74 |

51.0 |

51.0 |