1. The Quiet Geometry of the Lung

For decades, lung ultrasound spoke in the language of artefacts — lines, shadows, and reverberations that echoed the limits of imaging the air-filled lung. But within those echoes, something real was always waiting: a geometry that breathed, a structure that pulsed, a pattern that was not illusion but physiology in motion.

This marks the beginning of a new understanding — the recognition that the normal lung image is not a random play of reflections but a coherent, structured baseline with measurable features: shape, continuity, proportion, and symmetry. At its heart lies the Twinkling White Area (TWA) — the dynamic subpleural field where peripheral densities interweave in a living biological process. TWA is not an artifact but a signature of organization, a reflection of ventilation–perfusion harmony.When this organized field begins to deform — when continuity fades or geometry fractures — the image evolves into pathology. This transition defines the Sick Bat Sign, where structural distortion replaces the balanced geometry of the Healthy Bat Sign. Disease does not invent new echoes; it alters the architecture of the existing image

Among these transformed patterns, some hold diagnostic precision:

The Front Sight in Rear Sight Sign reveals dual perfusion — peripheral pulmonary arterial occlusion with preserved central bronchial collateral flow.

The progressive alteration of the TWA pattern delineates the continuum from healthy aeration to inflammation, infection malignancies, fibrosis, or infarction.

Healthy bat sign versus Chiroptera sign. It is a dilemma whenever we see an image of lung ultrasound. This approach is like a “window” through which you can see how the weather is.

Lung ultrasound enables accurate bedside identification of emphysematous, bronchial remodeling, particularly through expiratory changes of length and wide of TWA, rib shadow distortion, and pleural-rib distance reduction. These sonographic patterns are storytellers that reflect regional and phenotypic heterogeneity and may serve as real-time, non-invasive surrogates for spirometry in the evaluation of obstructive syndrome.

Posterior basal pleural separation with unequal pleural, thickness represents an important marker for distinguishing acute from chronic lung involvement, including differentiation between acute and chronic pulmonary embolism.

Thus, lung ultrasound transcends the traditional vocabulary of artefacts and becomes a true structural language—a visual grammar of physiology and pathophysiology. Each image reflects a dynamic equilibrium between air, tissue, and blood flow. Within this geometric framework, the lung is no longer an echo chamber but a living morphological, functional map, in which brightness, shadow, and form mirror real-time cardiopulmonary interaction.

2. Innovative Conceptual Framework in Lung Ultrasound

3. Twinkling White Area (TWA) within the Merlin Space

A Dynamic Subpleural Morphologic–Functional Tissue–Air Interface

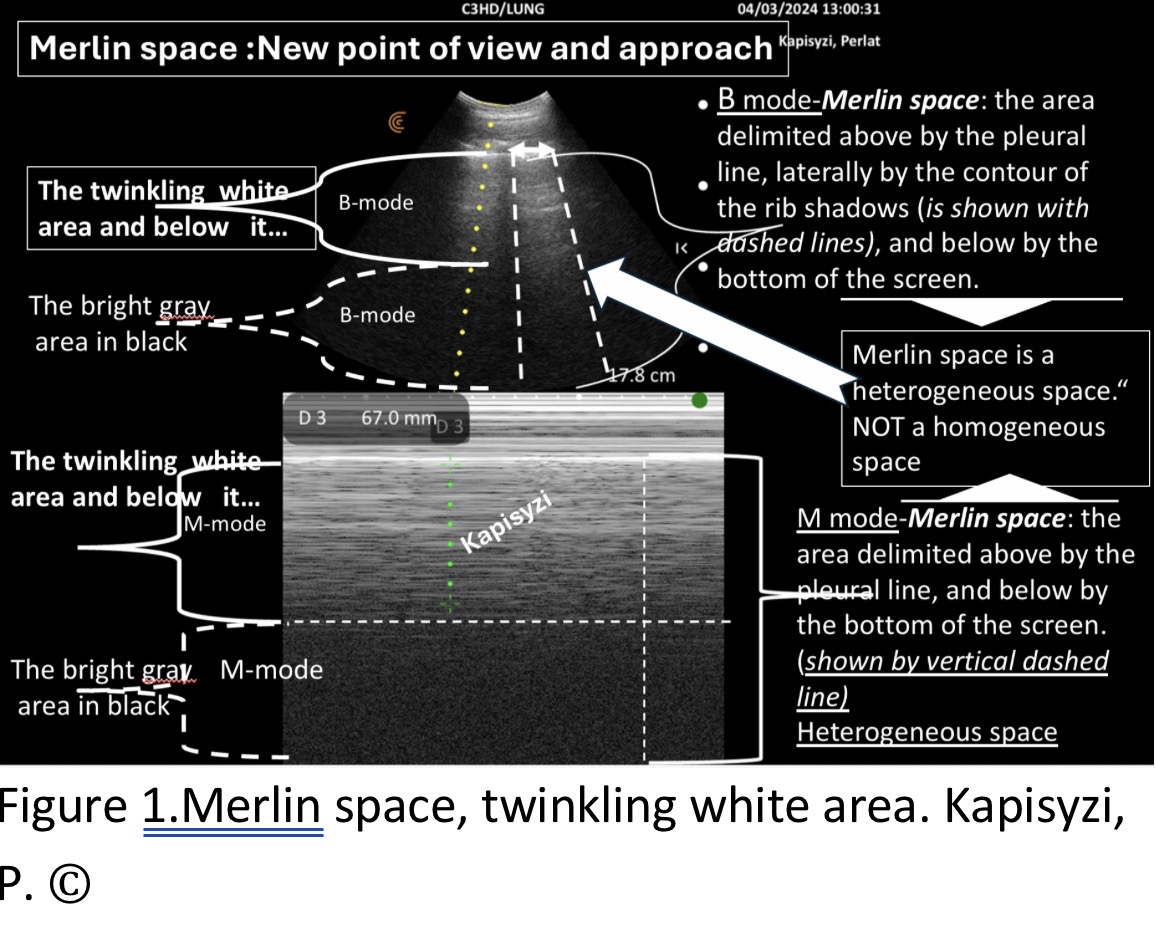

TWA represents the true subpleural reflective interface, an area where peripheral tissue densities interweave dynamically in an active biological process, rather than an acoustic artifact. It belongs to the Merlin Space, a structured reflective corridor bounded by the pleural line and rib shadows, whose dimensions and echo patterns vary with physiology and pathology. This defines the structural baseline for normal lung imaging (

Figure 1) [

1].

Therefore, we defined the Merlin space as follows: The Merlin space is the hyper-echoic twinkling white area below the pleural line, delimited laterally by rib shadows and inferiorly by the hypo-echoic twinkling black area extending to the bottom of the screen. This definition more accurately reflects the real presentation of the Merlin space and helps in understanding the changes it undergoes in abnormal lung conditions (

Figure 1).

Evaluating the structural and functional components of Merlin’s space provides a holistic understanding of lung ultrasound findings:

Twinkling White Area: Analyze its configuration, density, homogeneity, and border regularity. Grey Area Inside Black Region: Assess its relationship with surrounding structures. Rib Shadows: Evaluate their width, length, and distance from the pleural line. This systematic approach helps identify the healthy bat sign, a hallmark of normal lung ultrasound findings. Deviations from this pattern may indicate the “sick bat sign,” associated with underlying pathologies

4. Healthy Bat Sign vs. Sick Bat Sign

Morphologic Integrity versus Structural Distortion of the Peripheral Lung

According to Lichtenstein and other authors, the “bat sign” is a configuration composed of the ribs and their shadows, standing for the bat’s wings, and the pleural line, representing its body. When examining the bat’s wings from beginning to end (where the beginning is the ribs and the extension are the shadows of the ribs), the body cannot be depicted as a simple line but rather as a truncated cone with its base at the pleural line. Thus, the bat’s body aligns with the hyper-echoic, twinkling area in the Merlin space. Therefore, it is crucial not only to see the bat’s wings but also its body. Recognizing the normal appearance of the bat’s body (hyper echoic twinkling white area) along with the bat sign (ribs’s line and shadow, pleural line) is essential for early detection of injuries, known as “sick bat,” in the lungs [

2].

The Bat Sign evolves from a static anatomical landmark to a functional morphologic continuum. Healthy Bat: preserved TWA geometry, harmonious rib shadows, and homogeneous echotexture. Sick Bat: deformation of TWA dimensions (width, length, contour) and irregular rib-shadow dynamics, revealing early parenchymal or obstructive pathology. This model replaces the concept of 'artefactual patterns' with real structural descriptors (

Figure 2), [

2].

Knowing this normal structure which to our knowledge has not been described in this way in details but Merlin’s space has been considered homogeneous—allows us to use ultrasound to discern when “something” is not normal at the lung periphery. If we are not familiar with the “healthy bat” image, it will not be easy to recognize the “sick bat’s” images with various diseases, especially in the initial stages [

2].

Sick Bat sign refers to any ultrasound image in which one or more of the following components are observed, either together or separately:

Thickened, irregular, serrated, or partially/fully absent pleural line.

Absence or reduction of lung sliding.

Identification of the gap between the two pleural lines: the parietal and visceral pleura.

A "twinkling white" zone shortened or extended beyond the range of 3.5–6.5 cm.

Expansion of the conical portion of the "twinkling white" zone.

Heterogeneity of the "twinkling white" zone with vertical or horizontal hyper- or hypoechoic densities.

Negative silhouette sign at the borders of the "twinkling white" zone.

"Waterfall" sign with a positive silhouette sign at the borders of the "twinkling white" zone.

Absence, gap of twinkling white zone.

Irregular contours of the "twinkling white" zone.

Increased distance between the rib lines and the pleural line exceeding 0.5 cm.

Position of the rib’s lines appearing almost adjacent and parallel to pleural line.

Widening of rib shadows, with irregular rib contour visualization.

Extension of rib shadows to the bottom of the screen, with or without hyper-echoic densities visible within the rib shadows.

Missing of gray in black zone [

2].

5. Front Sight in Rear Sight Sign (within Sick Bat progression)

A Geometric–Functional Hemodynamic Signature of Pulmonary Infarction

The Front Sight in Rear Sight Sign represents a distinct hemodynamic and geometric echo-phenotype of pulmonary infarction, appearing within the Sick Bat progression.It is defined by two symmetric hypoechoic zones (A)—corresponding to infarcted, non-perfused pulmonary segments—flanking a central preserved region (B) that remains perfused through bronchial arterial collateral flow.

This configuration creates a triphasic geometric pattern in which:

Zone A (bilateral hypoechoic wedges) reflects abrupt interruption of pulmonary arterial perfusion.

Zone B (central isoechoic or preserved band) represents the bronchial rescue zone, the only territory still receiving oxygenated blood through the systemic bronchial arteries.

The interface between zones A and B produces a sharp, weapon-sight–like alignment, giving the sign its characteristic appearance.

Functionally, this sign establishes one of the clearest direct visual correspondences in lung ultrasound: echo morphology mirroring dual vascular supply (pulmonary vs. bronchial artery).

By making the dual-circulation physiology visible at the bedside, the Front Sight in Rear Sight Sign elevates pulmonary infarction from a non-specific “wedge-shaped hypoechoic area” to a structured hemodynamic signature, advancing the geometric-functional paradigm of this new framework. A hemodynamic echo-sign of pulmonary infarction, characterized by two hypoechoic zones (A) flanking a central preserved region (B) sustained by bronchial collateral perfusion. It establishes a direct visual correlation between echo morphology and dual vascular supply, contributing to functional interpretation of vascular injuries (

Figure 3), [

2].

6. Breaking Free from Artifact Labels

A Pathology-Oriented Approach

Lung ultrasound interpretation can benefit from adopting a descriptive, pathology-focused terminology, akin to approaches used in advanced imaging techniques like CT or MRI. These modalities emphasize anatomical and pathological findings over the technical processes that generate the images. For example:

CT reports describe “ground-glass opacities” or “hyperdense masses,” without referring to imaging mechanisms like iterative reconstruction.

Similarly, LU should prioritize findings' clinical relevance over their physical origins.Proposed Terminological Changes:

A-Lines: Describe as horizontal hyper-echoic lines (not as artifact) indicating (except normal lung) increased air/fluid ratios, observed in conditions like COPD, asthma, or pulmonary embolism.B-Lines more than three refer to as vertical streaky hyper-echoic densities (not as artifact), reflecting interstitial fluid accumulation.

C-Lines: Describe as pleural thickening, irregularities without hypo or hyper echoic densities with pleural interruptions to improve precision.

This conceptual shift reshapes the fundamental interpretive framework of lung ultrasound, advancing beyond the reductionist artifact terminology of A- and B-lines. LUS is viewed as real tissue-interface imaging, where each echo expresses a structural or physiological interaction within the lung parenchyma (

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6), [

3].

7. Ultrasound as an Initial Bedside Spirometry Tool

Innovative Conceptual Framework in Functional Lung Ultrasound

As we have emphasized throughout this innovative framework, mastering the geometry and functional behavior of the healthy Merlin Space—particularly the morphology, proportionality, and coherence of the Twinkling White Area (TWA)—is fundamental for high-precision functional lung ultrasound.

This knowledge serves as more than a reference point; it forms an internal cognitive model against which the brain rapidly compares every new ultrasound pattern.

Importantly, this rapid pattern recognition is often mislabeled as “intuition.” Yet we must distinguish sharply between expert intuition—a high-speed perceptual judgment grounded in deep internalized knowledge—and the superficial optimism of ignorance, an illusion of understanding arising from lack of expertise.Here, intuition is not mystical guesswork but the end result of knowing the normal geometry–function relationship so well that deviations become instantly visible.

Much like looking through a window and immediately sensing both the weather and the time of day—not through speculation, but through decoding known atmospheric cues—the clinician who understands normal TWA geometry can instantly distinguish whether an image represents a healthy state or a Sick Bat Sign.

Through this conceptual lens, the three peripheral lung phenotypes emerge as distinct “atmospheric” signatures, each expressing a unique harmony—and disharmony—between geometry and function.

Emphysema – Geometric Compression and Black-Dominant Atmosphere (“Nightfall Pattern”)

In emphysema, hyperinflation generates deep, uninterrupted black aeration that overtakes the sonographic field.

The subpleural functional architecture collapses in its vertical dimension:

the TWA becomes short, truncated, and disproportionately wide,

its natural vertical proportionality is lost,

micro-reflective subpleural interfaces are progressively obliterated,

the rib-shadow corridors become narrower, shorter, and less sharply defined, reflecting loss of the subpleural density that normally sustains their depth and contrast,

and the pleural line expresses a compressed, low-complexity reflective boundary.

This geometric distortion is a direct expression of functional decline: alveolar overdistension, loss of elastic recoil, and destruction of the peripheral capillary–interstitial network, which normally generates micro-reflections and structural depth.

Visually, this creates the nightfall atmosphere, where brightness collapses into a low, horizontal band, while the image above and below it becomes dominated by darkness—an immediate geometric signature of emphysematous hyperinflation.

Chronic Bronchitis – Geometric Elongation and Diffuse Subpleural Brightness (“Foggy Dawn Pattern”)

Chronic bronchitis produces a diametrically different transformation.

Here, the TWA becomes elongated, extending downwards along its vertical axis:

vertical continuity increases,

brightness becomes diffuse and subtly hazy,

contour irregularities reflect peripheral airway remodeling,

subpleural reflectivity intensifies due to increased density, mucosal edema, and airflow irregularity,

yet alveolar architecture remains preserved, preventing the collapse seen in emphysema.

This elongation is a geometric expression of functional obstruction without hyperinflation. The reflective interface gains depth but loses crispness, resembling a foggy dawn where light is present but softened through suspended density.

The rib shadows remain structurally preserved but appear visually longer relative to the expanded TWA, reinforcing the impression of an extended, thickened subpleural interface.(

Figure 8: Foggy dawn pattern)

Normal Lung – Geometric Equilibrium and Stable Reflective Pattern (“Cloud in a Clear Sky Pattern”)

The normal lung sets the archetype for comparison.

Its TWA demonstrates:

balanced width-to-length proportions,

clean, symmetric transitions into the rib shadows,

crisp but gentle margins,

stable brightness without diffusion,

and coherent geometry expressing intact pleural integrity and physiologic aeration.

This appearance is neither exaggerated nor attenuated; it is structurally harmonious, representing the healthy interaction between the pleural layers and the subpleural microarchitecture.

Visually, it resembles a white cloud in a clear sky—defined, bright, and suspended in a stable environment.

This equilibrium becomes the baseline atmospheric state from which deviations toward nightfall (compression) or foggy dawn (elongation) are immediately perceivable to the informed eye.

(

Figure 9: Cloud in a clear sky pattern)

Integrating TWA motion, rib-shadow displacement, and pleural kinetics allows the quantification of airflow changes and obstruction patterns at the bedside. This approach inaugurates Functional Sonopulmonology, transforming lung ultrasound into a visual spirometer for obstructive syndromes [

4,

5]

8. Diagnostic Importance of Pleural Separation Sign in Lung Ultrasound

A New Geometric Marker of Chronic Visceral Pleuritis and Vascular Chronicity

The pleural separation sign represents a novel geometric–functional observation in lung ultrasound: the distinct visualization of the parietal and visceral pleura as two clearly separated echogenic lines, rather than as a single fused pleural complex.This uncommon appearance emerged through systematic imaging with 2.5–5 MHz Clarius transducers, which allow the discrimination of pleural micro-geometry.

Importantly, the sign does not suggest acute exudative pleuritis. Instead, the pattern—subtle yet disproportionate separation between the pleural layers—combined with consecutive pleural interruptions, is far more compatible with chronic remodeling of the visceral pleura.

Such remodeling may include:

thickened fibrotic laminae,

chronic inflammatory deposition,

low-grade fibrovascular change,

and altered sliding behavior that increases the visual distance between layers.

In this framework, pleural separation becomes a functional signature: a marker of chronic, non-exudative, viscerally confined inflammatory processes rather than acute pleural disease.

Crucially, in the vascular context, this geometry acquires additional diagnostic value.

When present alongside hypo perfused subpleural territories, pleural separation may offer a non-invasive sonographic clue for differentiating chronic from acute pulmonary embolism, reflecting the chronicity of pleural–subpleural interaction in long-standing vascular obstruction. (

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12)

Thus, the pleural separation sign contributes to the emerging ecosystem of functional, geometry-based markers in lung ultrasound, reinforcing the paradigm that structural geometry mirrors underlying physiology, chronicity, and vascular history.[

6].

Author’s Note: The cited works by Kapisyzi et al. represent original conceptual contributions introducing structural, hemodynamic, and functional reinterpretations of lung ultrasound imaging. These references are not secondary citations but primary sources defining the frameworks of Merlin Space, Twinkling White Area (TWA), Healthy vs Sick Bat Sign, Front Sight in Rear Sight, Ultrasound as Initial Bedside Spirometry and Pleural Separation Sign. Their inclusion here serves to ensure terminological coherence and methodological continuity within the same investigative line, rather than to amplify authorship.

References

- Kapisyzi, P.; Çela, D.; Dilka, E.; Tashi, E.; Nuredini, O.; et al. Lung Ultrasound, Merlin Space, New Point of View, and Approach. Ann Case Rep. 2024, 9, 1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapisyzi, P.; Nuredini, O.; Karaulli, L.; Petre, O.; Argjiri, D.; et al. Lung Ultrasound: “Healthy Bat Sign” vs. Sick Chiroptera Patterns. Ann Case Rep. 2024, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapisyzi, P.; Tafai, S.; Petre, O.; Hysa, E.; Çela, D.; et al. Lung Ultrasound: Breaking Free from Artifact Labels and Misnomers. J Clin Res Rep. published online. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapisyzi, P.; Xhardo, E.; Nuredini, O.; Tafa, H.; Karaulli, L.; et al. Lung Ultrasound: An Initial Bedside ‘Spirometry’ Tool in Diagnosing Obstructive Syndrome. Int J Clin Case Rep Rev. 2025, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapisyzi, P.; Tashi, E.; Nuredini, O.; Karaulli, L.; Gjoni, J.; et al. Lung Ultrasound: An Initial Bedside ‘Spirometry’ Tool in Diagnosing Obstructive Syndrome. Echo-graphic findings in chronic bronchitis part two. Int J Clin Case Rep Rev. 2025, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapisyzi, P.; Tashi, E.; Cuko, A.; Telo, S. Pleural Separation Sign: Posterior-Basal Predominance and Physiologic Interpretation. Archives of Medical and Clinical Case Studies 2025, 5, 129. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).