Submitted:

19 January 2026

Posted:

20 January 2026

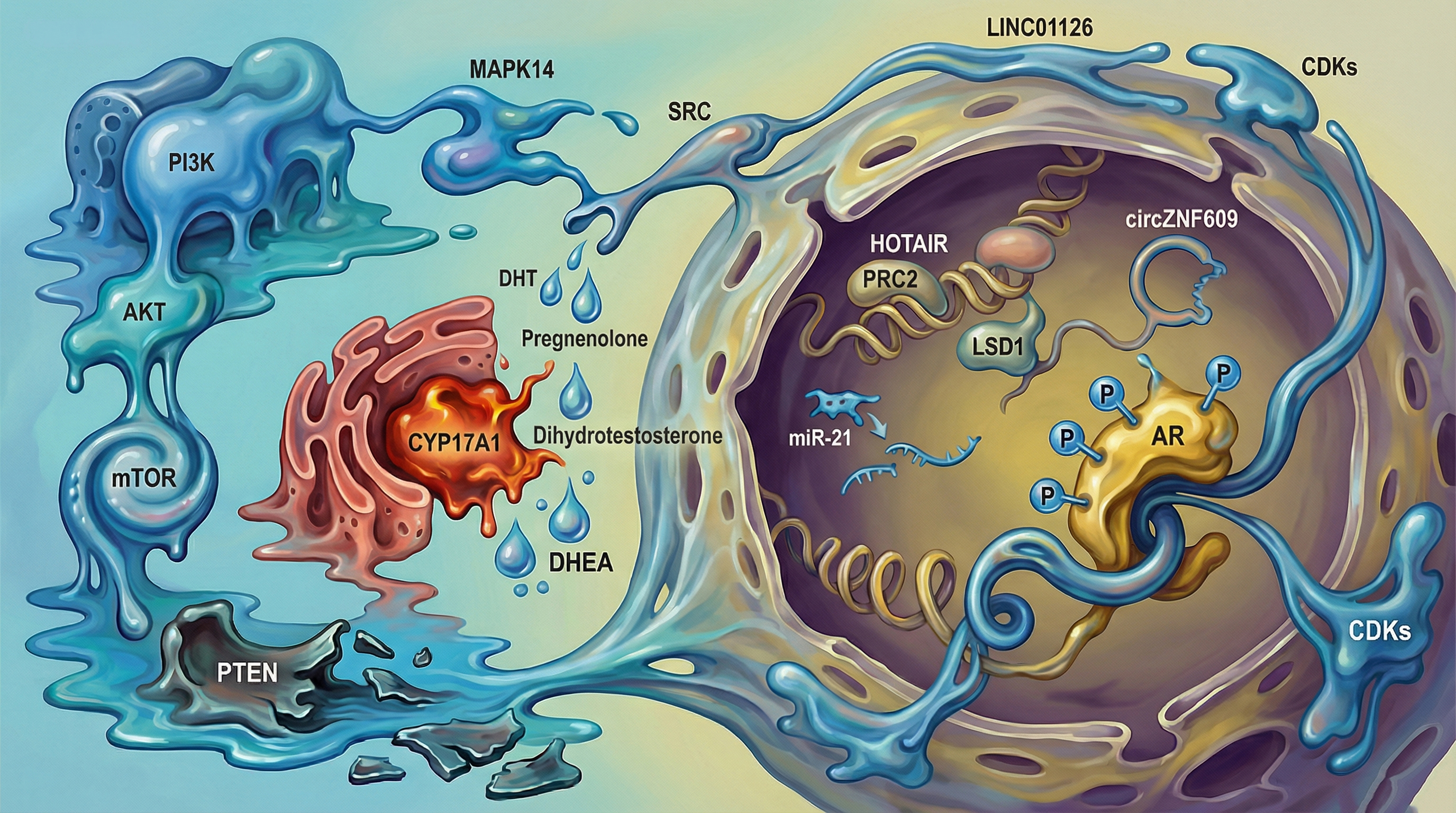

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction (Overview)

2. Signaling Through Protein Phosphorylation

2.1. Protein Kinases

2.1.1. Serine/Threonine Kinases

2.1.2. Tyrosine Kinases

2.2. Protein Phosphatases

2.3. In Vitro and In Vivo Assays Targeting Kinases in Human Diseases

3. Non-Coding RNAs (ncRNAs)

3.1. Small Non-Coding RNA (sncRNAs)

3.1.1. Micro-RNA (miRNA)

3.1.2. siRNA

3.1.3. piRNAs

3.2. Long Non-Coding RNAs (lncRNAs)

3.3. Mechanism of Action of RNAi Silencing

3.4. Advantages and Disadvantages of RNAi Technology

3.5. Roles of Non-Coding RNA in Prostate Cancer

4. Interplay Between Kinase Signaling and Non-Coding RNAs in Prostate Cancer Progression

| Inhibitor Class | Binding Conformation | R-Spine State | Mechanism of Action | Resistance Mechanism in PCa |

| Type I (e.g., Dasatinib) | Active (DFG-in) | Assembled | Binds to the ATP pocket when the kinase is in its catalytically active state. | "Gatekeeper" mutations (e.g., T315I) that sterically block the pocket; upregulation of upstream activators. |

| Type II (e.g., Cabozantinib) | Inactive (DFG-out) | Disassembled | Stabilizes the inactive conformation by occupying the hydrophobic pocket adjacent to the ATP site. | Mutations that favor the active conformation (R-spine assembly), preventing the inhibitor from binding. |

| Allosteric (e.g., Trametinib) | Inactive | Disassembled | Binds outside the ATP pocket, preventing the conformational change required for R-spine assembly. | Feedback loop activation of alternative pathways (e.g., PI3K activation following MAPK inhibition). |

5. Therapeutic Potential and Future Perspectives

5.1. Combining Kinase Inhibitors with RNA-Based Therapies

5.2. Advancing Precision Medicine Through Multi-Omics and Functional Genomics

5.3. Nanoparticle-Based Delivery Systems for RNA and Kinase Inhibitors

5.4. ncRNAs as Biomarkers for Prognosis and Treatment Monitoring

6. Conclusion

Funding statement

Disclosure statement

References

- He, Y. et al. Targeting signaling pathways in prostate cancer: mechanisms and clinical trials. Signal Transduct Target Ther 7, 198 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Maekawa, S., Takata, R. & Obara, W. Molecular Mechanisms of Prostate Cancer Development in the Precision Medicine Era: A Comprehensive Review. Cancers (Basel) 16 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Perdana, N. R., Mochtar, C. A., Umbas, R. & Hamid, A. R. The Risk Factors of Prostate Cancer and Its Prevention: A Literature Review. Acta Med Indones 48, 228–238 (2016).

- Zhang, H. et al. Androgen Metabolism and Response in Prostate Cancer Anti-Androgen Therapy Resistance. Int J Mol Sci 23 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Stangelberger, A., Waldert, M. & Djavan, B. Prostate cancer in elderly men. Rev Urol 10, 111–119 (2008).

- Snaterse, G. et al. Prostate cancer androgen biosynthesis relies solely on CYP17A1 downstream metabolites. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 236, 106446 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Miller, W. L. & Auchus, R. J. The molecular biology, biochemistry, and physiology of human steroidogenesis and its disorders. Endocr Rev 32, 81–151 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Petrunak, E. M., DeVore, N. M., Porubsky, P. R. & Scott, E. E. Structures of human steroidogenic cytochrome P450 17A1 with substrates. J Biol Chem 289, 32952–32964 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Kmetova Sivonova, M. et al. The role of CYP17A1 in prostate cancer development: structure, function, mechanism of action, genetic variations and its inhibition. Gen Physiol Biophys 36, 487–499 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Ferraldeschi, R., Sharifi, N., Auchus, R. J. & Attard, G. Molecular pathways: Inhibiting steroid biosynthesis in prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res 19, 3353–3359 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A. V., Mellon, S. H. & Miller, W. L. Protein phosphatase 2A and phosphoprotein SET regulate androgen production by P450c17. J Biol Chem 278, 2837–2844 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A. V. & Miller, W. L. Regulation of 17,20 lyase activity by cytochrome b5 and by serine phosphorylation of P450c17. J Biol Chem 280, 13265–13271 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Yoshimoto, F. K. & Auchus, R. J. The diverse chemistry of cytochrome P450 17A1 (P450c17, CYP17A1). J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 151, 52–65 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Alex, A. B., Pal, S. K. & Agarwal, N. CYP17 inhibitors in prostate cancer: latest evidence and clinical potential. Ther Adv Med Oncol 8, 267–275 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Flück, C. E. et al. Why boys will be boys: two pathways of fetal testicular androgen biosynthesis are needed for male sexual differentiation. Am J Hum Genet 89, 201–218 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Biason-Lauber, A., Miller, W. L., Pandey, A. V. & Flück, C. E. Of marsupials and men: "Backdoor" dihydrotestosterone synthesis in male sexual differentiation. Mol Cell Endocrinol 371, 124–132 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Wrobel, T. M. et al. Non-steroidal CYP17A1 Inhibitors: Discovery and Assessment. J Med Chem 66, 6542–6566 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Wrobel, T. M. et al. Pyridine indole hybrids as novel potent CYP17A1 inhibitors. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem 40, 2463014 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Auchus, R. J., Lee, T. C. & Miller, W. L. Cytochrome b5 augments the 17,20-lyase activity of human P450c17 without direct electron transfer. J Biol Chem 273, 3158–3165 (1998).

- Klein, E. A., Ciezki, J., Kupelian, P. A. & Mahadevan, A. Outcomes for intermediate risk prostate cancer: are there advantages for surgery, external radiation, or brachytherapy? Urol Oncol 27, 67–71 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, K. E. & Penning, T. M. Partners in crime: deregulation of AR activity and androgen synthesis in prostate cancer. Trends Endocrinol Metab 21, 315–324 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Wrobel, T. M. et al. Discovery of Novel Non-Steroidal Cytochrome P450 17A1 Inhibitors as Potential Prostate Cancer Agents. Int J Mol Sci 21, 4868 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Wang, B. R. et al. Developing New Treatment Options for Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer and Recurrent Disease. Biomedicines 10 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Obinata, D. et al. Recent Discoveries in the Androgen Receptor Pathway in Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Front Oncol 10, 581515 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. et al. Redirecting abiraterone metabolism to fine-tune prostate cancer anti-androgen therapy. Nature 533, 547–551 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Fizazi, K. et al. Abiraterone acetate plus prednisone in patients with newly diagnosed high-risk metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (LATITUDE): final overall survival analysis of a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 20, 686–700 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Attard, G., Reid, A. H., Olmos, D. & de Bono, J. S. Antitumor activity with CYP17 blockade indicates that castration-resistant prostate cancer frequently remains hormone driven. Cancer Res 69, 4937–4940 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. H. A. et al. Major adverse cardiovascular events of enzalutamide versus abiraterone in prostate cancer: a retrospective cohort study. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 27, 776–782 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Tee, M. K. & Miller, W. L. Phosphorylation of human cytochrome P450c17 by p38alpha selectively increases 17,20 lyase activity and androgen biosynthesis. J Biol Chem 288, 23903–23913 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Mulholland, D. J. et al. Cell autonomous role of PTEN in regulating castration-resistant prostate cancer growth. Cancer Cell 19, 792–804 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Taylor, B. S. et al. Integrative genomic profiling of human prostate cancer. Cancer Cell 18, 11–22 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Antonarakis, E. S. et al. AR-V7 and resistance to enzalutamide and abiraterone in prostate cancer. N Engl J Med 371, 1028–1038 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Watson, P. A., Arora, V. K. & Sawyers, C. L. Emerging mechanisms of resistance to androgen receptor inhibitors in prostate cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 15, 701–711 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Davies, M. A. & Samuels, Y. Analysis of the genome to personalize therapy for melanoma. Oncogene 29, 5545–5555 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Massague, J. TGFbeta in Cancer. Cell 134, 215–230 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Ikushima, H. & Miyazono, K. TGFbeta signalling: a complex web in cancer progression. Nat Rev Cancer 10, 415–424 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Li, C. & Wand, M. Approximate Translational Building Blocks for Image Decomposition and Synthesis. Acm Transactions on Graphics 34, 1–16 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Elimam, H. et al. Natural products and long non-coding RNAs in prostate cancer: insights into etiology and treatment resistance. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 398, 6349–6368 (2025). [CrossRef]

- Kohvakka, A. et al. Long noncoding RNA EPCART regulates translation through PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway and PDCD4 in prostate cancer. Cancer Gene Ther 31, 1536–1546 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Narla, G., Sangodkar, J. & Ryder, C. B. The impact of phosphatases on proliferative and survival signaling in cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci 75, 2695–2718 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Ardito, F., Giuliani, M., Perrone, D., Troiano, G. & Lo Muzio, L. The crucial role of protein phosphorylation in cell signaling and its use as targeted therapy (Review). Int J Mol Med 40, 271–280 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H. C., Qi, R. Z., Paudel, H. & Zhu, H. J. Regulation and function of protein kinases and phosphatases. Enzyme Res 2011, 794089 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S. S., Herberg, F. W., Veglia, G. & Wu, J. Edmond Fischer's kinase legacy: History of the protein kinase inhibitor and protein kinase A. IUBMB Life 75, 311–323 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Hanks, S. K. & Hunter, T. The eukaryotic protein kinase superfamily: kinase (catalytic) domain structure and classification 1. The FASEB journal 9, 576–596 (1995).

- Schwartz, P. A. & Murray, B. W. Protein kinase biochemistry and drug discovery. Bioorg Chem 39, 192–210 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Dhanasekaran, N. & Premkumar Reddy, E. Signaling by dual specificity kinases. Oncogene 17, 1447–1455 (1998). [CrossRef]

- Adeyelu, T. et al. KinFams: De-Novo Classification of Protein Kinases Using CATH Functional Units. Biomolecules 13 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M. J., Xu, B.-e., Stippec, S. & Cobb, M. H. Different Domains of the Mitogen-activated Protein Kinases ERK3 and ERK2 Direct Subcellular Localization and Upstream Specificityin Vivo. Journal of Biological Chemistry 277, 5094–5100 (2002).

- Robinson, D. R., Wu, Y. M. & Lin, S. F. The protein tyrosine kinase family of the human genome. Oncogene 19, 5548–5557 (2000). [CrossRef]

- Torrecilla, I. et al. Phosphorylation and regulation of a G protein-coupled receptor by protein kinase CK2. J Cell Biol 177, 127–137 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Collins, S. J. Exploiting Water-Mediated Interactions to Inhibit Mutationally Activated HER2, State University of New York at Stony Brook, (2022).

- Doublet, P., Grangeasse, C., Obadia, B., Vaganay, E. & Cozzone, A. J. Structural organization of the protein-tyrosine autokinase Wzc within Escherichia coli cells. J Biol Chem 277, 37339–37348 (2002). [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q. et al. TREM (Triggering Receptor Expressed on Myeloid Cells)-1 Inhibition Attenuates Neuroinflammation via PKC (Protein Kinase C) delta/CARD9 (Caspase Recruitment Domain Family Member 9) Signaling Pathway After Intracerebral Hemorrhage in Mice. Stroke 52, 2162–2173 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Lemmon, M. A. & Schlessinger, J. Cell signaling by receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell 141, 1117–1134 (2010). [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y. Serine/threonine phosphatases: mechanism through structure. Cell 139, 468–484 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Cully, M., You, H., Levine, A. J. & Mak, T. W. Beyond PTEN mutations: the PI3K pathway as an integrator of multiple inputs during tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Cancer 6, 184–192 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X. D. & Agazie, Y. M. Inhibition of SHP2 leads to mesenchymal to epithelial transition in breast cancer cells. Cell Death Differ 15, 988–996 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Ruvolo, P. P. Role of protein phosphatases in the cancer microenvironment. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 1866, 144–152 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Vainonen, J. P., Momeny, M. & Westermarck, J. Druggable cancer phosphatases. Sci Transl Med 13, eabe2967 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Crespo, P. & Gutkind, J. S. Activation of MAPKs by G protein-coupled receptors. Methods Mol Biol 250, 203–210 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Marinissen, M. J. et al. The small GTP-binding protein RhoA regulates c-jun by a ROCK-JNK signaling axis. Mol Cell 14, 29–41 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Hilder, T. L., Malone, M. H. & Johnson, G. L. Hyperosmotic induction of mitogen-activated protein kinase scaffolding. Methods Enzymol 428, 297–312 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Black, M. H., Gradowski, M., Pawłowski, K. & Tagliabracci, V. S. in Methods in enzymology Vol. 667 575–610 (Elsevier, 2022).

- Burke, J. E., Triscott, J., Emerling, B. M. & Hammond, G. R. V. Beyond PI3Ks: targeting phosphoinositide kinases in disease. Nat Rev Drug Discov 22, 357–386 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Castelo-Soccio, L. et al. Protein kinases: drug targets for immunological disorders. Nat Rev Immunol 23, 787–806 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Narayanan, J. et al. Role and mechanistic actions of protein kinase inhibitors as an effective drug target for cancer and COVID. Arch Microbiol 205, 238 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Kim, D. H. & Rossi, J. J. Strategies for silencing human disease using RNA interference. Nat Rev Genet 8, 173–184 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Mahmoodi Chalbatani, G. et al. Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) in cancer therapy: a nano-based approach. Int J Nanomedicine 14, 3111–3128 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Carthew, R. W. & Sontheimer, E. J. Origins and Mechanisms of miRNAs and siRNAs. Cell 136, 642–655 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Ozata, D. M., Gainetdinov, I., Zoch, A., O'Carroll, D. & Zamore, P. D. PIWI-interacting RNAs: small RNAs with big functions. Nat Rev Genet 20, 89–108 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Rottiers, V. & Naar, A. M. MicroRNAs in metabolism and metabolic disorders. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 13, 239–250 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Farberov, L. et al. Multiple Copies of microRNA Binding Sites in Long 3'UTR Variants Regulate Axonal Translation. Cells 12 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Bonci, D. et al. The miR-15a-miR-16-1 cluster controls prostate cancer by targeting multiple oncogenic activities. Nat Med 14, 1271–1277 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Ostadrahimi, S. et al. miR-1266-5p and miR-185-5p Promote Cell Apoptosis in Human Prostate Cancer Cell Lines. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 19, 2305–2311 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Strand, S. H. et al. Validation of the four-miRNA biomarker panel MiCaP for prediction of long-term prostate cancer outcome. Sci Rep 10, 10704 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. et al. Distinct microRNA expression profiles in prostate cancer stem/progenitor cells and tumor-suppressive functions of let-7. Cancer Res 72, 3393–3404 (2012). [CrossRef]

- Gan, J. et al. MicroRNA-375 is a therapeutic target for castration-resistant prostate cancer through the PTPN4/STAT3 axis. Exp Mol Med 54, 1290–1305 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Konoshenko, M. & Laktionov, P. The miRNAs involved in prostate cancer chemotherapy response as chemoresistance and chemosensitivity predictors. Andrology 10, 51–71 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Bartel, D. P. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116, 281–297 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Place, R. F., Li, L. C., Pookot, D., Noonan, E. J. & Dahiya, R. MicroRNA-373 induces expression of genes with complementary promoter sequences. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 1608–1613 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Roberts, A. M., Ward, C. C. & Nomura, D. K. Activity-based protein profiling for mapping and pharmacologically interrogating proteome-wide ligandable hotspots. Curr Opin Biotechnol 43, 25–33 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Weng, W., Li, H. & Goel, A. Piwi-interacting RNAs (piRNAs) and cancer: Emerging biological concepts and potential clinical implications. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer 1871, 160–169 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Wu, H., Yang, L. & Chen, L. L. The Diversity of Long Noncoding RNAs and Their Generation. Trends Genet 33, 540–552 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Mattick, J. S. et al. Long non-coding RNAs: definitions, functions, challenges and recommendations. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 24, 430–447 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Cayuela, M. L., Flores, J. M. & Blasco, M. A. The telomerase RNA component Terc is required for the tumour-promoting effects of Tert overexpression. EMBO Rep 6, 268–274 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Sakurai, K., Reon, B. J., Anaya, J. & Dutta, A. The lncRNA DRAIC/PCAT29 Locus Constitutes a Tumor-Suppressive Nexus. Mol Cancer Res 13, 828–838 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y. et al. Circular RNA circ0005276 promotes the proliferation and migration of prostate cancer cells by interacting with FUS to transcriptionally activate XIAP. Cell Death Dis 10, 792 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Hao, T. et al. MALAT1 knockdown inhibits prostate cancer progression by regulating miR-140/BIRC6 axis. Biomed Pharmacother 123, 109666 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Yao, M. et al. LINC00675 activates androgen receptor axis signaling pathway to promote castration-resistant prostate cancer progression. Cell Death Dis 11, 638 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Fu, D. et al. Long non-coding RNA CRNDE regulates the growth and migration of prostate cancer cells by targeting microRNA-146a-5p. Bioengineered 12, 2469–2479 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Le Hars, M. et al. Pro-tumorigenic role of lnc-ZNF30-3 as a sponge counteracting miR-145-5p in prostate cancer. Biol Direct 18, 38 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Cantile, M. et al. The role of HOTAIR in the modulation of resistance to anticancer therapy. Front Mol Biosci 11, 1414651 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Statello, L., Guo, C. J., Chen, L. L. & Huarte, M. Gene regulation by long non-coding RNAs and its biological functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 22, 96–118 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Ren, D. et al. Oncogenic miR-210-3p promotes prostate cancer cell EMT and bone metastasis via NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Mol Cancer 16, 117 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Fire, A. et al. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 391, 806–811 (1998). [CrossRef]

- Pushparaj, P. N., Aarthi, J. J., Manikandan, J. & Kumar, S. D. siRNA, miRNA, and shRNA: in vivo applications. J Dent Res 87, 992–1003 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Elbashir, S. M. et al. Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs mediate RNA interference in cultured mammalian cells. Nature 411, 494–498 (2001). [CrossRef]

- Kim, D. H. et al. Synthetic dsRNA Dicer substrates enhance RNAi potency and efficacy. Nat Biotechnol 23, 222–226 (2005). [CrossRef]

- Lam, J. K., Chow, M. Y., Zhang, Y. & Leung, S. W. siRNA Versus miRNA as Therapeutics for Gene Silencing. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 4, e252 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Penner, P. E., Cohen, L. H. & Loeb, L. A. RNA-dependent DNA polymerase: presence in normal human cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 42, 1228–1234 (1971). [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, N. et al. RNA interference: biology, mechanism, and applications. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 67, 657–685 (2003). [CrossRef]

- Yokota, T. et al. Unique structure of Ascaris suum b5-type cytochrome: an additional alpha-helix and positively charged residues on the surface domain interact with redox partners. Biochem J 394, 437–447 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Mocellin, S. & Provenzano, M. RNA interference: learning gene knock-down from cell physiology. J Transl Med 2, 39 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Moreira, D., Pereira, A. M., Lopes, A. L. & Coimbra, S. The best CRISPR/Cas9 versus RNA interference approaches for Arabinogalactan proteins' study. Mol Biol Rep 47, 2315–2325 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Moreira, V. J. V. et al. In planta RNAi targeting Meloidogyne incognita Minc16803 gene perturbs nematode parasitism and reduces plant susceptibility. Journal of Pest Science 97, 411–427 (2024).

- Pecot, C. V., Calin, G. A., Coleman, R. L., Lopez-Berestein, G. & Sood, A. K. RNA interference in the clinic: challenges and future directions. Nat Rev Cancer 11, 59–67 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Ramalho-Carvalho, J., Fromm, B., Henrique, R. & Jeronimo, C. Deciphering the function of non-coding RNAs in prostate cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev 35, 235–262 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Ling, H. et al. Junk DNA and the long non-coding RNA twist in cancer genetics. Oncogene 34, 5003–5011 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Sang, H. et al. The regulatory process and practical significance of non-coding RNA in the dissemination of prostate cancer to the skeletal system. Front Oncol 14, 1358422 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Bu, T., Li, L. & Tian, J. Unlocking the role of non-coding RNAs in prostate cancer progression: exploring the interplay with the Wnt signaling pathway. Front Pharmacol 14, 1269233 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Imani, S. et al. MicroRNA-34a targets epithelial to mesenchymal transition-inducing transcription factors (EMT-TFs) and inhibits breast cancer cell migration and invasion. Oncotarget 8, 21362–21379 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Chawra, H. S. et al. MicroRNA-21's role in PTEN suppression and PI3K/AKT activation: Implications for cancer biology. Pathol Res Pract 254, 155091 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., Hamdane, D., Im, S. C. & Waskell, L. Cytochrome b5 inhibits electron transfer from NADPH-cytochrome P450 reductase to ferric cytochrome P450 2B4. J Biol Chem 283, 5217–5225 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Dong, Q., Qiu, H., Piao, C., Li, Z. & Cui, X. LncRNA SNHG4 promotes prostate cancer cell survival and resistance to enzalutamide through a let-7a/RREB1 positive feedback loop and a ceRNA network. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 42, 209 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Guarnerio, J. et al. Oncogenic Role of Fusion-circRNAs Derived from Cancer-Associated Chromosomal Translocations. Cell 165, 289–302 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Wang, L. et al. Downregulation of circ-ZNF609 Promotes Heart Repair by Modulating RNA N(6)-Methyladenosine-Modified Yap Expression. Research (Wash D C) 2022, 9825916 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y. H., Deng, J. L., Wang, G. & Zhu, Y. S. Long non-coding RNAs in prostate cancer: Functional roles and clinical implications. Cancer Lett 464, 37–55 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Ren, S. et al. Long noncoding RNA MALAT-1 is a new potential therapeutic target for castration resistant prostate cancer. J Urol 190, 2278–2287 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Pickard, M. R., Mourtada-Maarabouni, M. & Williams, G. T. Long non-coding RNA GAS5 regulates apoptosis in prostate cancer cell lines. Biochim Biophys Acta 1832, 1613–1623 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Marks, L. S. & Bostwick, D. G. Prostate Cancer Specificity of PCA3 Gene Testing: Examples from Clinical Practice. Rev Urol 10, 175–181 (2008).

- Merola, R. et al. PCA3 in prostate cancer and tumor aggressiveness detection on 407 high-risk patients: a National Cancer Institute experience. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 34, 15 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Li, T. et al. Long noncoding RNA HOTAIR regulates the invasion and metastasis of prostate cancer by targeting hepaCAM. Br J Cancer 124, 247–258 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A. et al. LncRNA HOTAIR Enhances the Androgen-Receptor-Mediated Transcriptional Program and Drives Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Cell Rep 13, 209–221 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Yang, F. et al. Non-coding RNAs: Emerging roles in the characterization of immune microenvironment and immunotherapy of prostate cancer. Biochem Pharmacol 214, 115669 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Pudova, E. et al. Non-Coding RNAs and the Development of Chemoresistance to Docetaxel in Prostate Cancer: Regulatory Interactions and Approaches Based on Machine Learning Methods. Life (Basel) 13 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. et al. Function of microRNA-124 in the pathogenesis of cancer (Review). Int J Oncol 64 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Mbeje, M. et al. In Silico Bioinformatics Analysis on the Role of Long Non-Coding RNAs as Drivers and Gatekeepers of Androgen-Independent Prostate Cancer Using LNCaP and PC-3 Cells. Curr Issues Mol Biol 45, 7257–7274 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Fu, A., Jacobs, D. I., Hoffman, A. E., Zheng, T. & Zhu, Y. PIWI-interacting RNA 021285 is involved in breast tumorigenesis possibly by remodeling the cancer epigenome. Carcinogenesis 36, 1094–1102 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Shih, J. W., Wang, L. Y., Hung, C. L., Kung, H. J. & Hsieh, C. L. Non-Coding RNAs in Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer: Regulation of Androgen Receptor Signaling and Cancer Metabolism. Int J Mol Sci 16, 28943–28978 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Missaghian, E. et al. Role of DNA methylation in the tissue-specific expression of the CYP17A1 gene for steroidogenesis in rodents. J Endocrinol 202, 99–109 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Fu, M. et al. The androgen receptor acetylation site regulates cAMP and AKT but not ERK-induced activity. J Biol Chem 279, 29436–29449 (2004). [CrossRef]

- Bridges, A. et al. Identification of the binding site on cytochrome P450 2B4 for cytochrome b5 and cytochrome P450 reductase. J Biol Chem 273, 17036–17049 (1998). [CrossRef]

- Udhane, S. S. & Fluck, C. E. Regulation of human (adrenal) androgen biosynthesis-New insights from novel throughput technology studies. Biochem Pharmacol 102, 20–33 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Zhu, W. et al. Oxidative stress increases the 17,20-lyase-catalyzing activity of adrenal P450c17 through p38alpha in the development of hyperandrogenism. Mol Cell Endocrinol 484, 25–33 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Argos, P. & Mathews, F. S. The structure of ferrocytochrome b5 at 2.8 A resolution. J Biol Chem 250, 747–751 (1975). [CrossRef]

- Yin, L. & Hu, Q. CYP17 inhibitors--abiraterone, C17,20-lyase inhibitors and multi-targeting agents. Nat Rev Urol 11, 32–42 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Mostaghel, E. A. Abiraterone in the treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. Cancer Manag Res 6, 39–51 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Ang, J. E., Olmos, D. & de Bono, J. S. CYP17 blockade by abiraterone: further evidence for frequent continued hormone-dependence in castration-resistant prostate cancer. Br J Cancer 100, 671–675 (2009). [CrossRef]

- Pozas, J. et al. Androgen Receptor Signaling Inhibition in Advanced Castration Resistance Prostate Cancer: What Is Expected for the Near Future? Cancers (Basel) 14 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Bonfils, C., Balny, C. & Maurel, P. Direct evidence for electron transfer from ferrous cytochrome b5 to the oxyferrous intermediate of liver microsomal cytochrome P-450 LM2. J Biol Chem 256, 9457–9465 (1981). [CrossRef]

- Xu, R. & Hu, J. The role of JNK in prostate cancer progression and therapeutic strategies. Biomed Pharmacother 121, 109679 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Chau, V., Madan, R. A. & Aragon-Ching, J. B. Protein kinase inhibitors for the treatment of prostate cancer. Expert Opin Pharmacother 22, 1889–1899 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, S. et al. Targeting Protein Kinases and Epigenetic Control as Combinatorial Therapy Options for Advanced Prostate Cancer Treatment. Pharmaceutics 14 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z. et al. Regulation of androgen receptor activity by tyrosine phosphorylation. Cancer Cell 10, 309–319 (2006). [CrossRef]

- Nunes-Xavier, C. E., Mingo, J., Lopez, J. I. & Pulido, R. The role of protein tyrosine phosphatases in prostate cancer biology. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res 1866, 102–113 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Kreisberg, J. I. & Ghosh, P. M. Cross-talk between the androgen receptor and the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway in prostate cancer. Curr Cancer Drug Targets 7, 591–604 (2007). [CrossRef]

- Andl, T., Ganapathy, K., Bossan, A. & Chakrabarti, R. MicroRNAs as Guardians of the Prostate: Those Who Stand before Cancer. What Do We Really Know about the Role of microRNAs in Prostate Biology? Int J Mol Sci 21 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y. et al. Androgen-repressed lncRNA LINC01126 drives castration-resistant prostate cancer by regulating the switch between O-GlcNAcylation and phosphorylation of androgen receptor. Clin Transl Med 14, e1531 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y. et al. miR-302/367/LATS2/YAP pathway is essential for prostate tumor-propagating cells and promotes the development of castration resistance. Oncogene 36, 6336–6347 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Kinkade, C. W. et al. Targeting AKT/mTOR and ERK MAPK signaling inhibits hormone-refractory prostate cancer in a preclinical mouse model. J Clin Invest 118, 3051–3064 (2008). [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Liu, K. Y., Liu, Q. & Cao, Q. Androgen Receptor-Related Non-coding RNAs in Prostate Cancer. Front Cell Dev Biol 9, 660853 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Mirzakhani, K. et al. The androgen receptor-lncRNASAT1-AKT-p15 axis mediates androgen-induced cellular senescence in prostate cancer cells. Oncogene 41, 943–959 (2022). [CrossRef]

- Leite, K. R. et al. MicroRNA-100 expression is independently related to biochemical recurrence of prostate cancer. J Urol 185, 1118–1122 (2011). [CrossRef]

- Nabavi, N. et al. miR-100-5p inhibition induces apoptosis in dormant prostate cancer cells and prevents the emergence of castration-resistant prostate cancer. Sci Rep 7, 4079 (2017). [CrossRef]

- He, R. Z., Luo, D. X. & Mo, Y. Y. Emerging roles of lncRNAs in the post-transcriptional regulation in cancer. Genes Dis 6, 6–15 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Cao, J. The functional role of long non-coding RNAs and epigenetics. Biol Proced Online 16, 11 (2014). [CrossRef]

- Coppola, V. et al. BTG2 loss and miR-21 upregulation contribute to prostate cell transformation by inducing luminal markers expression and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Oncogene 32, 1843–1853 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Takayama, K. et al. RUNX1, an androgen- and EZH2-regulated gene, has differential roles in AR-dependent and -independent prostate cancer. Oncotarget 6, 2263–2276 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Shi, L. et al. Review on Long Non-Coding RNAs as Biomarkers and Potentially Therapeutic Targets for Bacterial Infections. Curr Issues Mol Biol 46, 7558–7576 (2024). [CrossRef]

- Hagman, Z. et al. miR-205 negatively regulates the androgen receptor and is associated with adverse outcome of prostate cancer patients. Br J Cancer 108, 1668–1676 (2013). [CrossRef]

- Shi, X. B. et al. miR-124 and Androgen Receptor Signaling Inhibitors Repress Prostate Cancer Growth by Downregulating Androgen Receptor Splice Variants, EZH2, and Src. Cancer Res 75, 5309–5317 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y. & Lai, M. Epigenetic Regulation and Therapeutic Targeting of Alternative Splicing Dysregulation in Cancer. LID - 10.3390/ph18050713 [doi] LID - 713.

- Wadosky, K. M. & Koochekpour, S. Androgen receptor splice variants and prostate cancer: From bench to bedside. Oncotarget 8, 18550–18576 (2017). [CrossRef]

- Shalem, O., Sanjana, N. E. & Zhang, F. High-throughput functional genomics using CRISPR-Cas9. Nat Rev Genet 16, 299–311 (2015). [CrossRef]

- Ashrafizadeh, M. et al. Progress in Delivery of siRNA-Based Therapeutics Employing Nano-Vehicles for Treatment of Prostate Cancer. Bioengineering (Basel) 7 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Mainini, F. & Eccles, M. R. Lipid and Polymer-Based Nanoparticle siRNA Delivery Systems for Cancer Therapy. Molecules 25 (2020). [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S., Zhi, D. & Huang, L. Lipid-based vectors for siRNA delivery. J Drug Target 20, 724–735 (2012). [CrossRef]

- He, M. X. et al. Transcriptional mediators of treatment resistance in lethal prostate cancer. Nat Med 27, 426–433 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Anil, P., Dastidar, S. G. & Banerjee, S. Unravelling the role of long non-coding RNAs in prostate carcinoma. Advances in Cancer Biology-Metastasis 6, 100067 (2022). [CrossRef]

| RNA Type | Name | Classification | Expression in PCa | Functional Roles | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA | miR-34a, let-7b, miR-141, miR-106 | Tumor-suppressive microRNAs | Downregulated | Inhibit prostate cancer (PCa) cell invasion by inducing apoptosis and arresting the cell cycle | [74] |

| miRNA | miR-452, miR-301b | Oncogenic microRNAs | Upregulated | Enhance invasion and stemness of cancer stem cells (CSCs) | [76,78] |

| miRNA | miR-15a/miR-16-1 cluster | Tumor-suppressive microRNAs | Downregulated | Induce apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in PCa cells via targeting BCL2 | [73] |

| miRNA | miR-133a-3p | Tumor-suppressive microRNA | Downregulated | Inhibits viability and invasion of PCa cells by promoting apoptosis; may regulate EGFR/AKT pathway | [75] |

| miRNA | miR-210-3p | Hypoxia-induced oncogenic microRNA | Upregulated | Drives epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and bone metastasis via NF-κB pathway activation |

[94] |

| miRNA | miR-375 | Oncogenic microRNA | Upregulated | Facilitates PCa progression, possibly via targeting SEC23A | [77] |

| lncRNA | HOTAIR | Oncogenic lncRNA | Upregulated | Enhances PCa cell proliferation and invasion; modulates chromatin state via PRC2 complex | [92] |

| piRNA | PIWIL2 | Oncogenic piRNA-associated protein | Upregulated | Promotes EMT, invasion, and metastasis; potential role in epigenetic silencing | [82] |

| lncRNA | Lnc-ZNF30-3 | Oncogenic lncRNA | Upregulated | Enhances PCa cell survival and correlates with poor prognosis in patients. acting as a competitive endogenous RNA (ceRNA) sponge for miR-145-5p, thereby derepressing the EMT driver TWIST1 | [91] |

| lncRNA | CRNDE | Oncogenic lncRNA | Upregulated | Stimulates PCa cell proliferation, migration, and invasion through Wnt/β-catenin signaling | [90] |

| circRNA | circ-0005276 | Oncogenic circular RNA | Upregulated | Promotes proliferation and invasion of PCa cells, likely via miRNA sponging | [87] |

| lncRNA | MALAT1 | Oncogenic lncRNA | Upregulated | Inhibits apoptosis and promotes PCa invasion by regulating EMT-related genes | [88] |

| lncRNA | PCAT29, DRAIC | Tumor-suppressive lncRNAs | Downregulated | Inhibit migration and metastasis of PCa cells; DRAIC interacts with IKK complex to suppress NF-κB | [86] |

| lncRNA | LINC00675 | Dual function lncRNA in CRPC | Upregulated | Promotes castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) progression and therapy resistance. Direct binding to the AR N-terminal domain, which blocks MDM2 interaction, preventing ubiquitination and degradation | [89] |

| lncRNA | TERC (Telomerase RNA Component) | Oncogenic lncRNA | Upregulated | Supports tumor progression by maintaining telomere integrity and enhancing proliferation | [85] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.