6.1. Consumption to Supply Estimation: Experiment I and II

Comparative Performance evaluation of individual regression models, i.e., XGBoost, MLP, RF and SVR, are conducted qualitatively and quantitatively. Please note that the performance evaluations of Experiment I and II are performed against the derived test dataset of the leak-corrected ground-truth supply data.

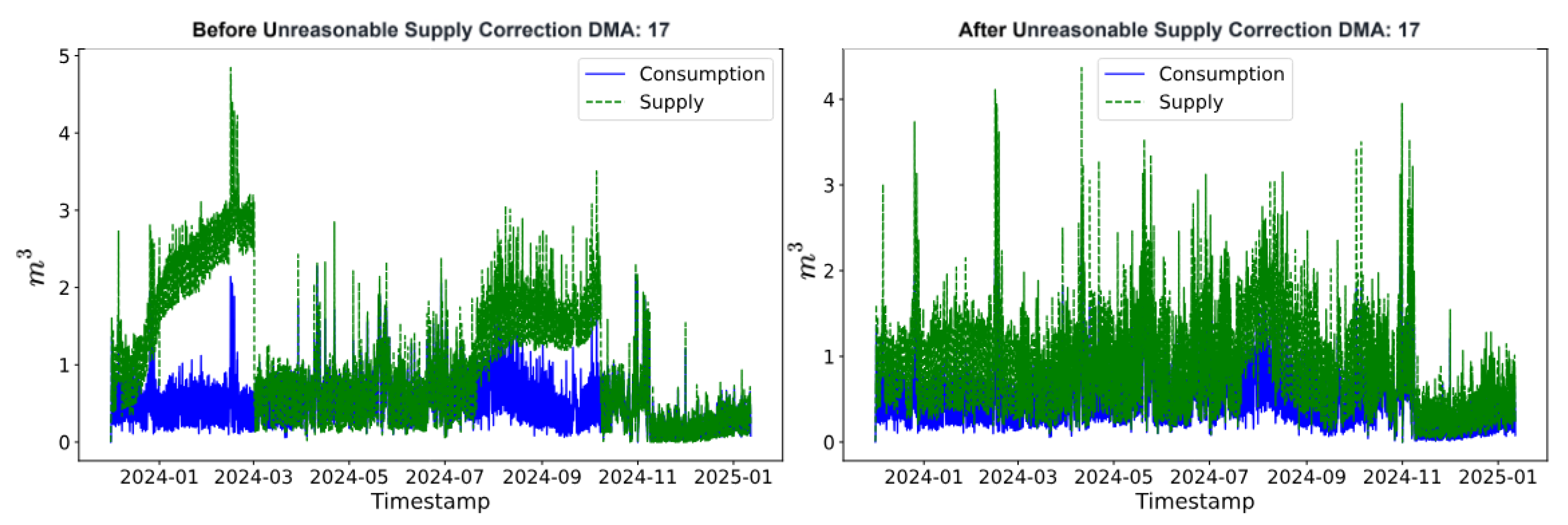

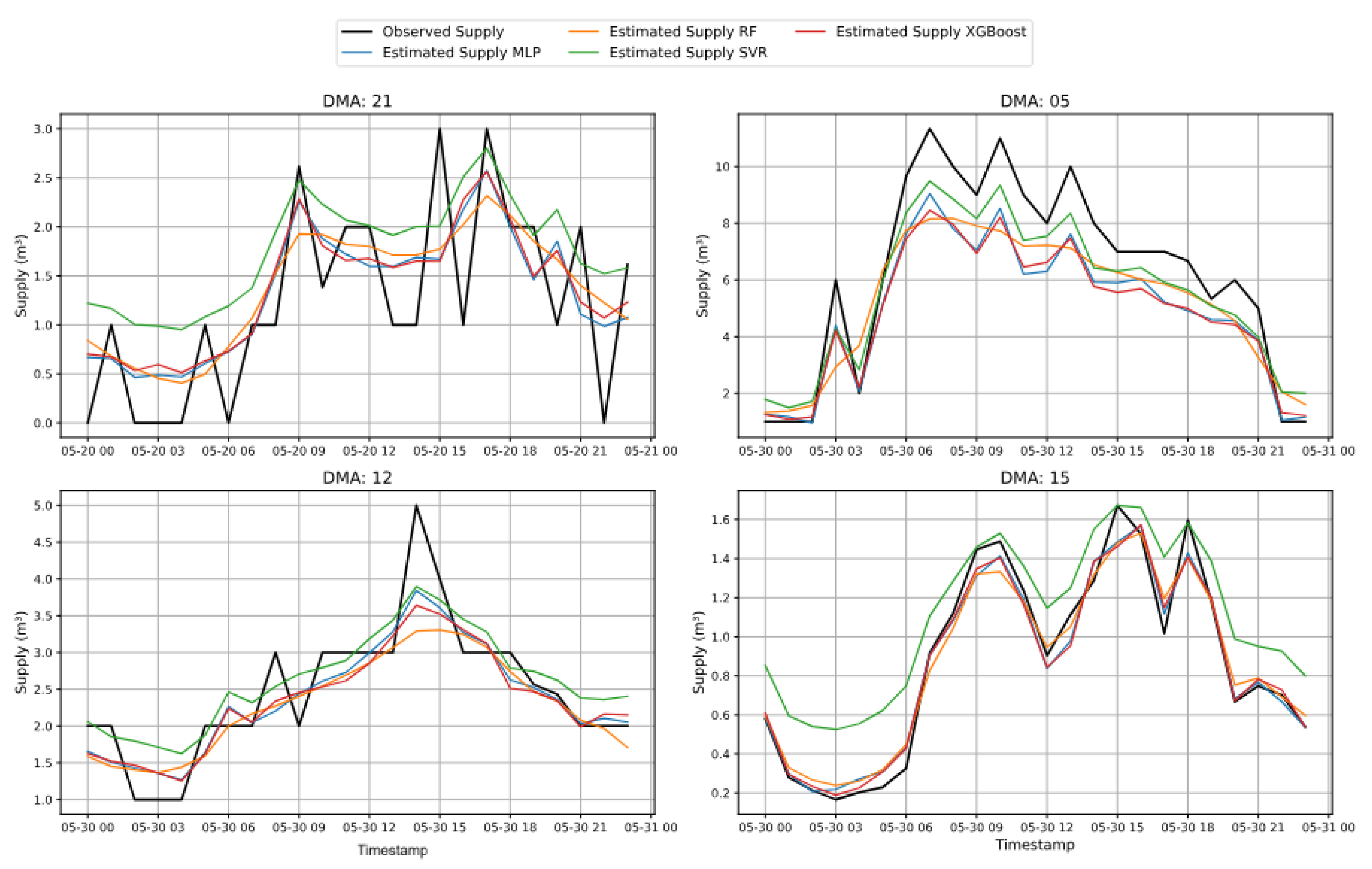

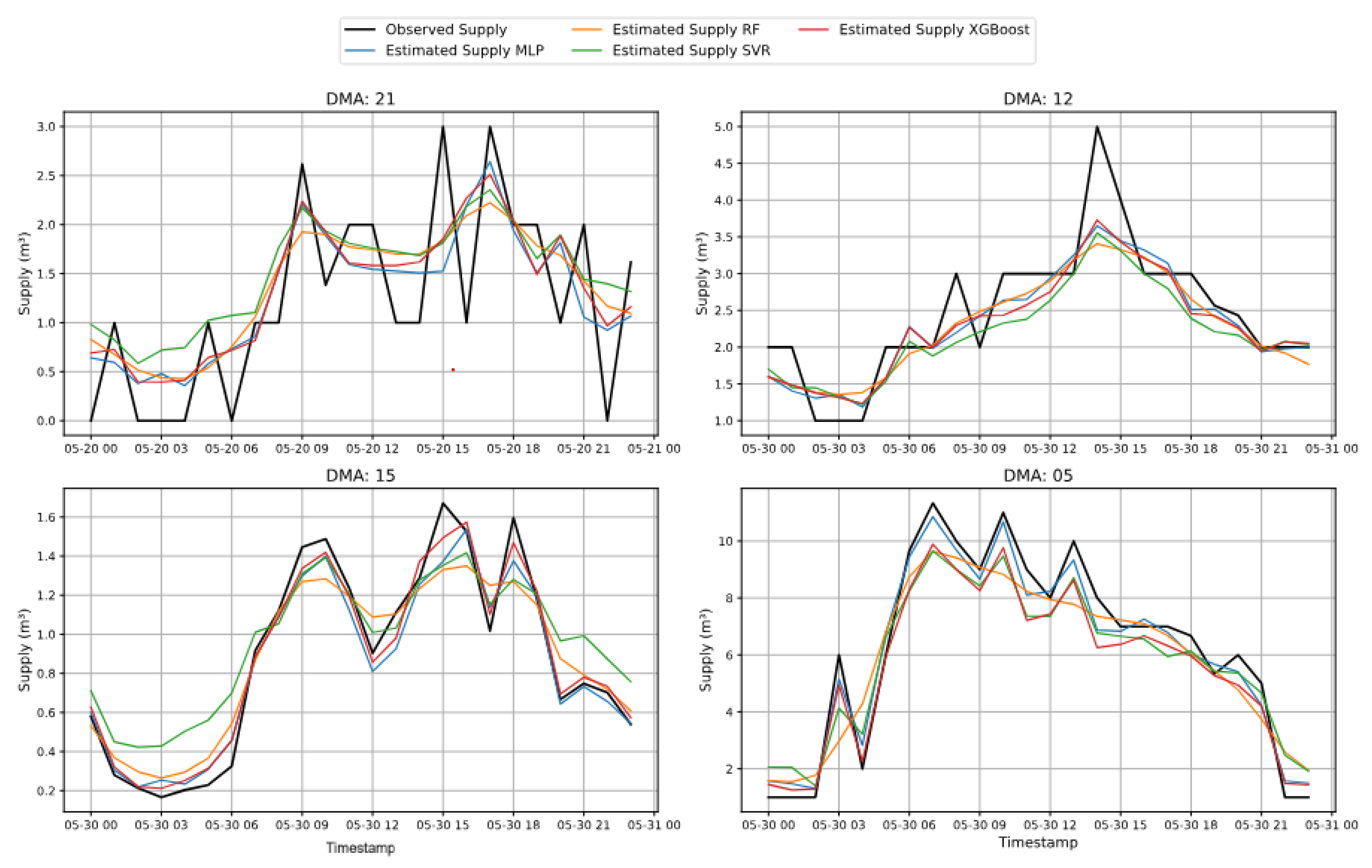

Figure 9 illustrates examples of predicted supply in comparison to ground truth supply. In DMA 15, most models–except SVR–closely follow the observed supply trend. In DMA 05, while most models track the supply pattern reasonably well, the RF model shows noticeable deviations. In contrast, all models struggle to capture the supply dynamics in DMA 21 and DMA 12. Among them, SVR consistently underperforms, primarily due to the lack of hyperparameter tuning constrained by computational limitations.

Figure 10 shows that, in the DMA-specific modeling approach, all machine learning models effectively follow the supply pattern in DMA 15 and DMA 05. However, in DMA 21 and DMA 12, the models struggle to capture the supply behavior accurately. Among all models, MLP consistently shows the closest alignment with the observed supply, followed by XGBoost. In contrast, the RF model fails to capture the supply trends reliably, while SVR demonstrates better performance compared to Experiment I which is likely impacted by suboptimal hyperparameter tuning. The dynamics of the DMA 21 is exhibited due to the data quality of the district flow meters. For this DMA the district meter data is collected from SCADA (Supervisory Control And Data Acquisition) system’s flow sensors, than smart meters. The flow sensor measurements are usually snapshot-kind recorded measurements. This leads to clipped time-series characteristics when data is collected with coarser resolution.

However, the predicted supply, which apparently appears to be not following the stochastic pattern of supply, is actually the result of generalization attained by the model, which has reproduced the supposed diurnal pattern by using higher data quality of consumption data. The anomalous spike appearing in DMA 12 between 13:00 and 15:00 on 30-05 is a physical effect of momentary valve opening, as informed by the utility. Such characteristics actually resembles to a leak-like pattern within small time-span. Hence, the regression models have captured the supposed normal supply pattern, and capturing the deviation within the mentioned time-frame is teh sole objective of our proposed framework.

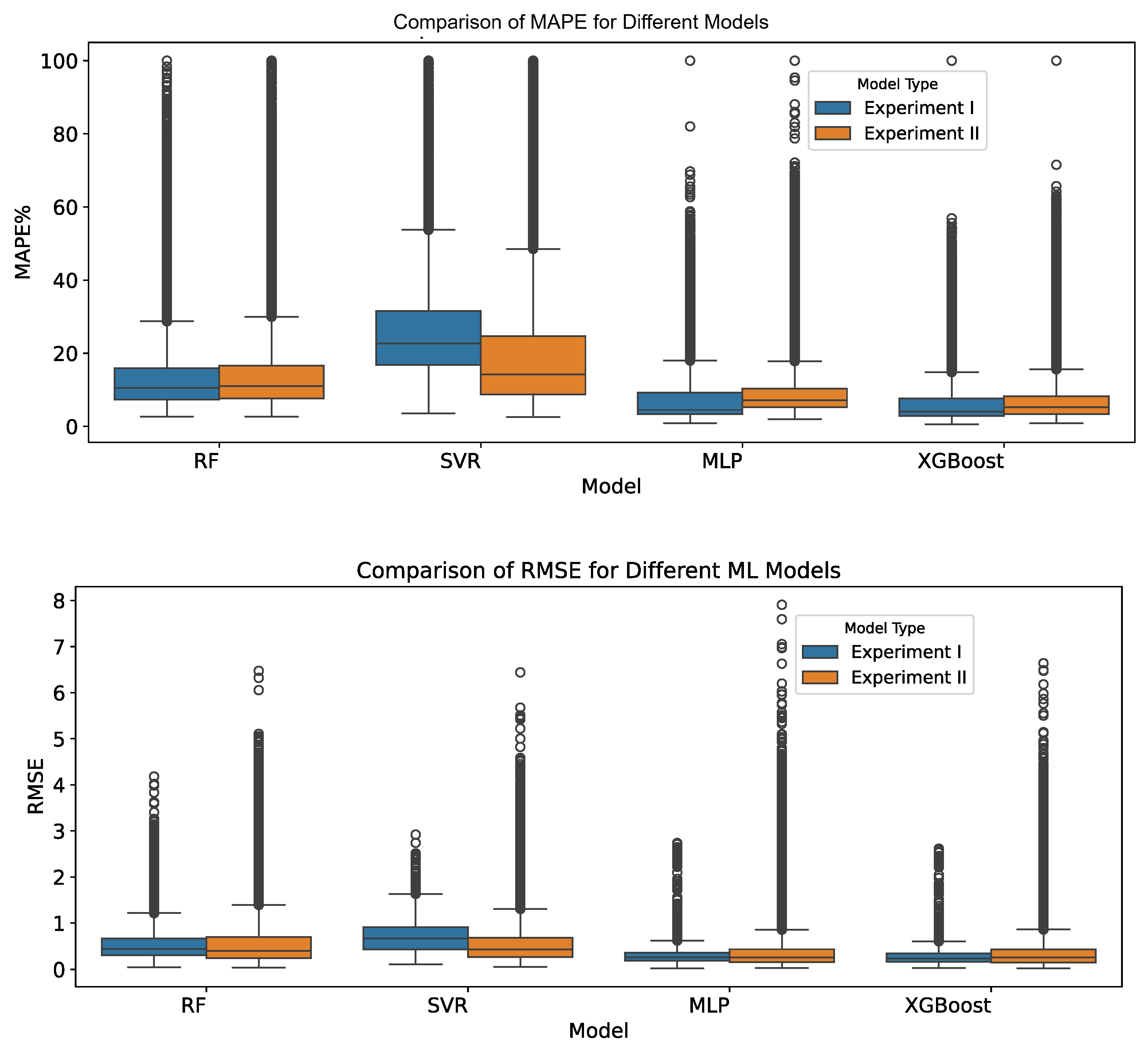

The results in the box plots (

Figure 11) along with

Table 3 clearly demonstrate XGBoost’s superior performance, consistently achieving the lowest median MAPE and RMSE with minimal variability. MLP remains competitive, showing moderate error rates and variability. SVR achieves lower error-range in Experiment II, indicating effective hyperparameter tuning. Conversely, RF shows higher error values and greater variability, suggesting limited robustness in modeling Consumption-supply dynamics.

Apart from SVR, performances of all the regression models suggest that the regression modeling approach of Experiment I results in lower mean and standard deviation of performance compared to their corresponding counterpart in Experiment II, i.e. DMA-specific modeling. Hence, the modeling approach of Experiment I is used in the end-to-end leak-detection pipeline.

XGBoost demonstrates strong consistency between the unified (Experiment I) and DMA-specific (Experiment II) frameworks, achieving nearly identical accuracy and error dispersion. This reflects its ability to capture both global and local consumption–supply relationships effectively through optimal tree partitioning and robust regularization. The MLP performs comparably across both setups, showing slightly lower mean error in the unified model but with higher variability. The unified framework benefits from larger aggregated data, though heterogeneous DMA patterns introduce instability in training and convergence. SVR exhibits the largest framework-dependent differences, performing significantly worse in the unified setting due to the absence of DMA-specific hyperparameter tuning. Its results highlight SVR’s sensitivity to parameter optimization rather than structural limitations of the modeling framework. RF performs similarly across both experiments, consistently lagging behind other models. Its bagging ensemble structure, while robust to noise, weakens fine-grained spatial relationships and lacks the adaptive capacity to model complex nonlinear dependencies.

Overall, the unified modeling framework achieves accuracy comparable to the per-DMA approach with substantially lower computational and maintenance overhead—only four models versus eighty-four—making it more scalable and operationally efficient for large-scale deployment. Most importantly, the performance evaluation shows the ability of the unified-modeling approach in Experiment I to capture DMA-specific Consumption-supply dynamics with the help of one-hot encoding of DMA names.

6.2. Leak Detection: Experiment III and IV

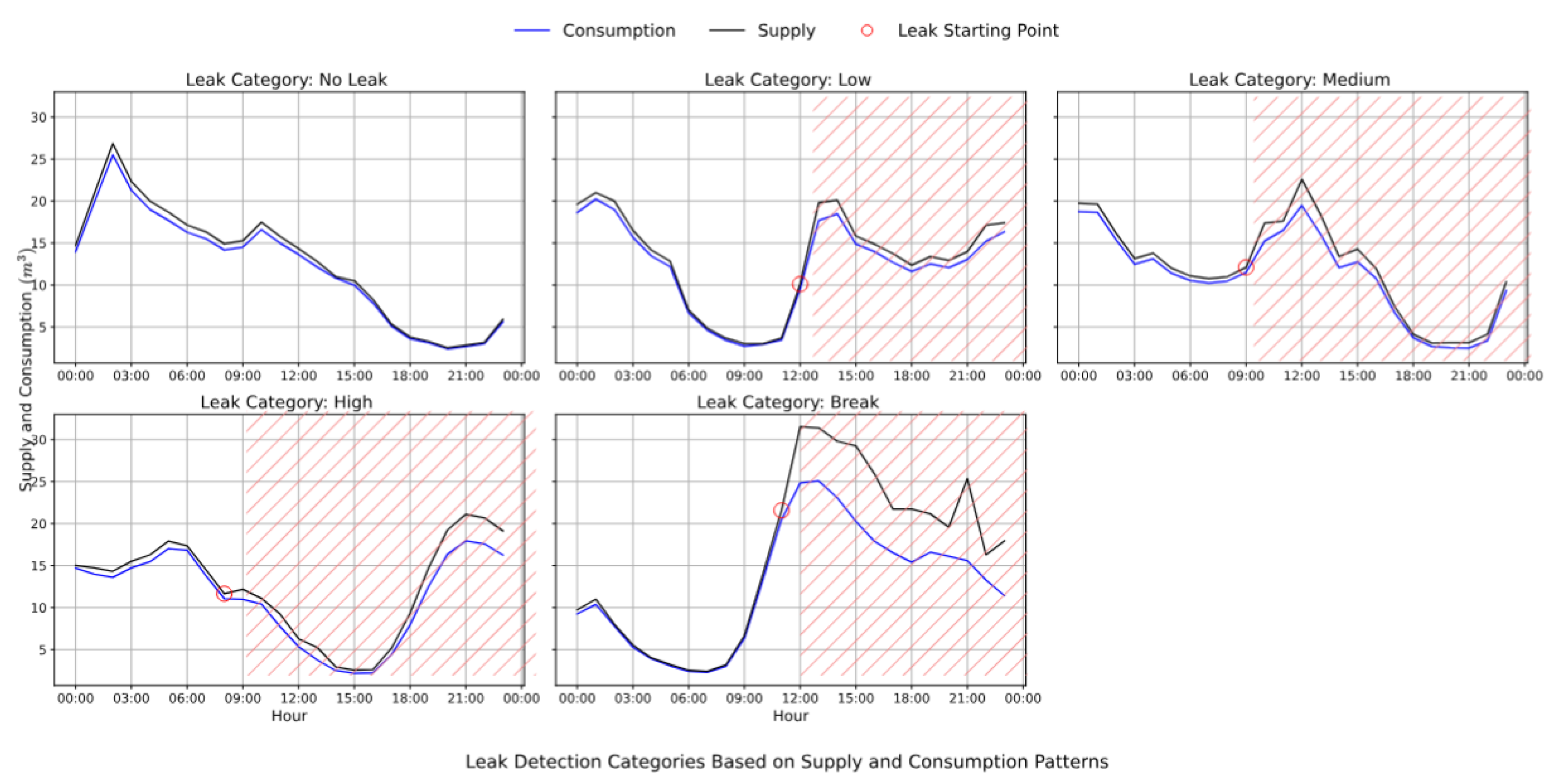

Leak detection performance is assessed both qualitatively and quantitatively in Experiments III and IV. The qualitative analysis visualizes how the predicted supply from different regression models deviates from the observed supply when trained using DMA-specific Consumption data and encoded DMA identifiers.

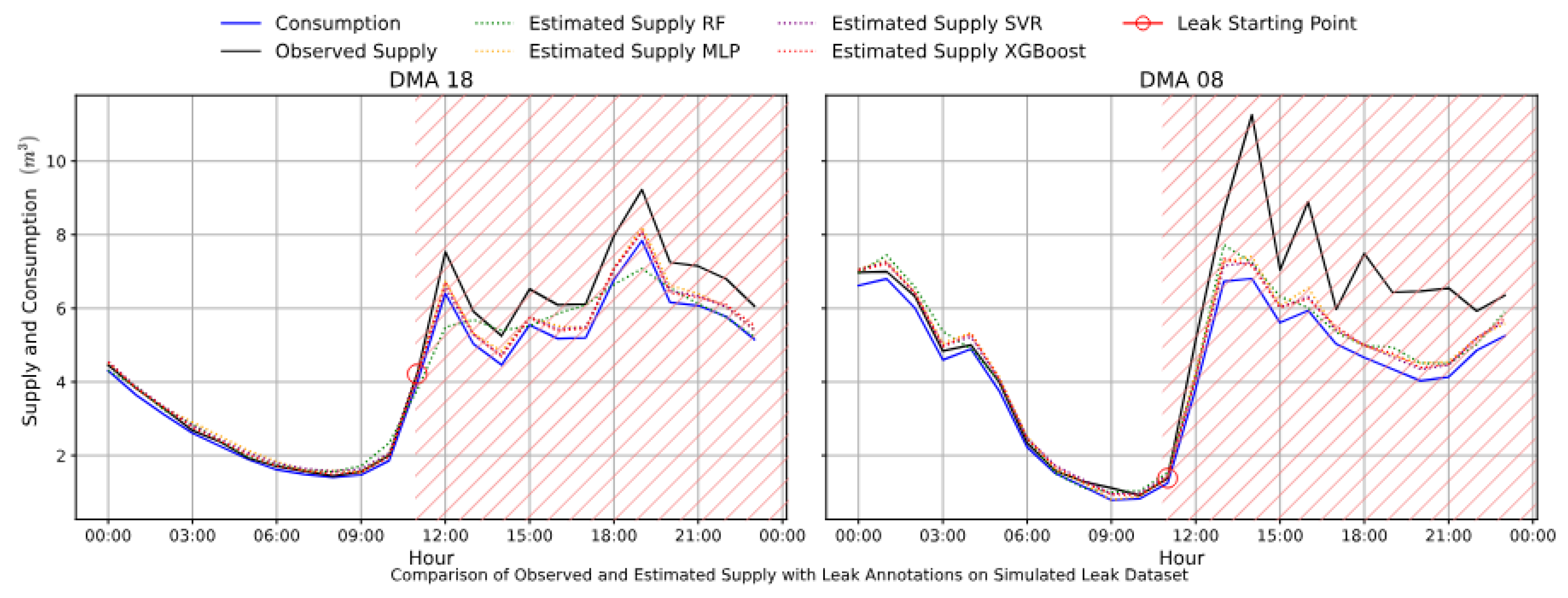

Figure 12 illustrates examples of mentioned deviation starting from leak-onset in the simulated dataset, whereas

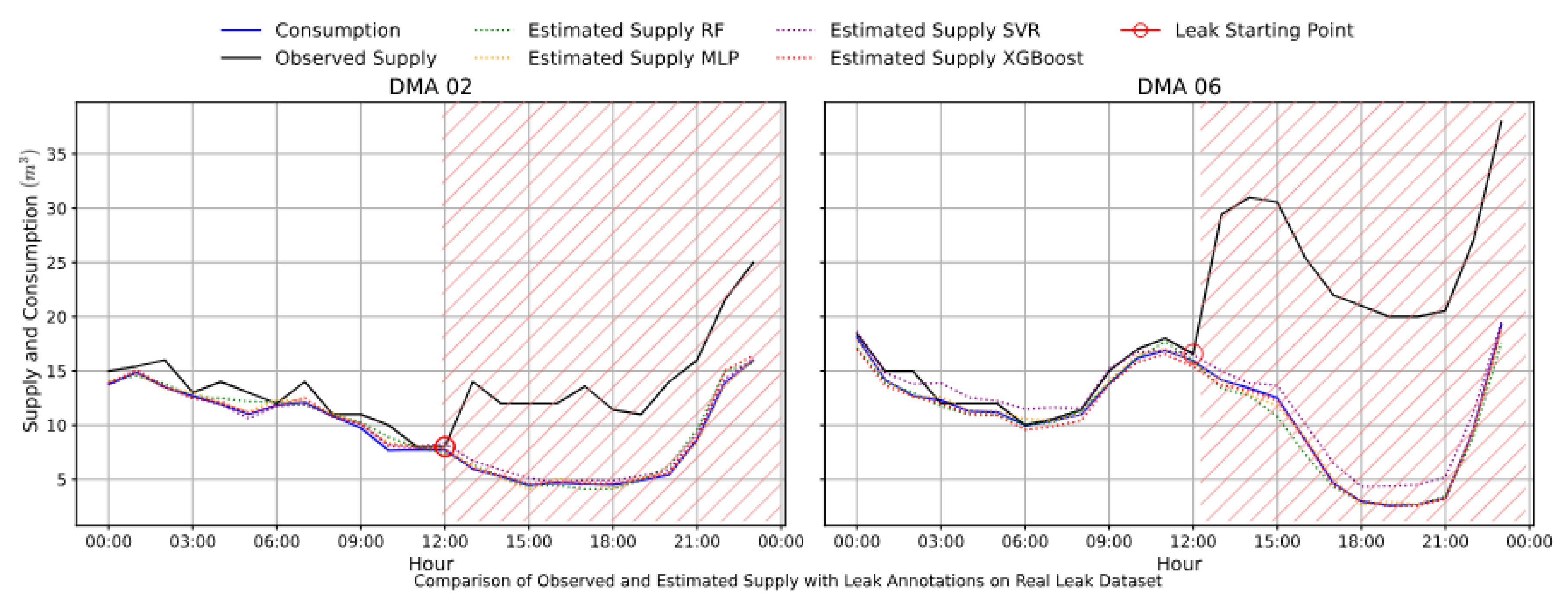

Figure 13 showcases the pattern-deviations of observed supply data with respect to predicted supply in real retrospective dataset.

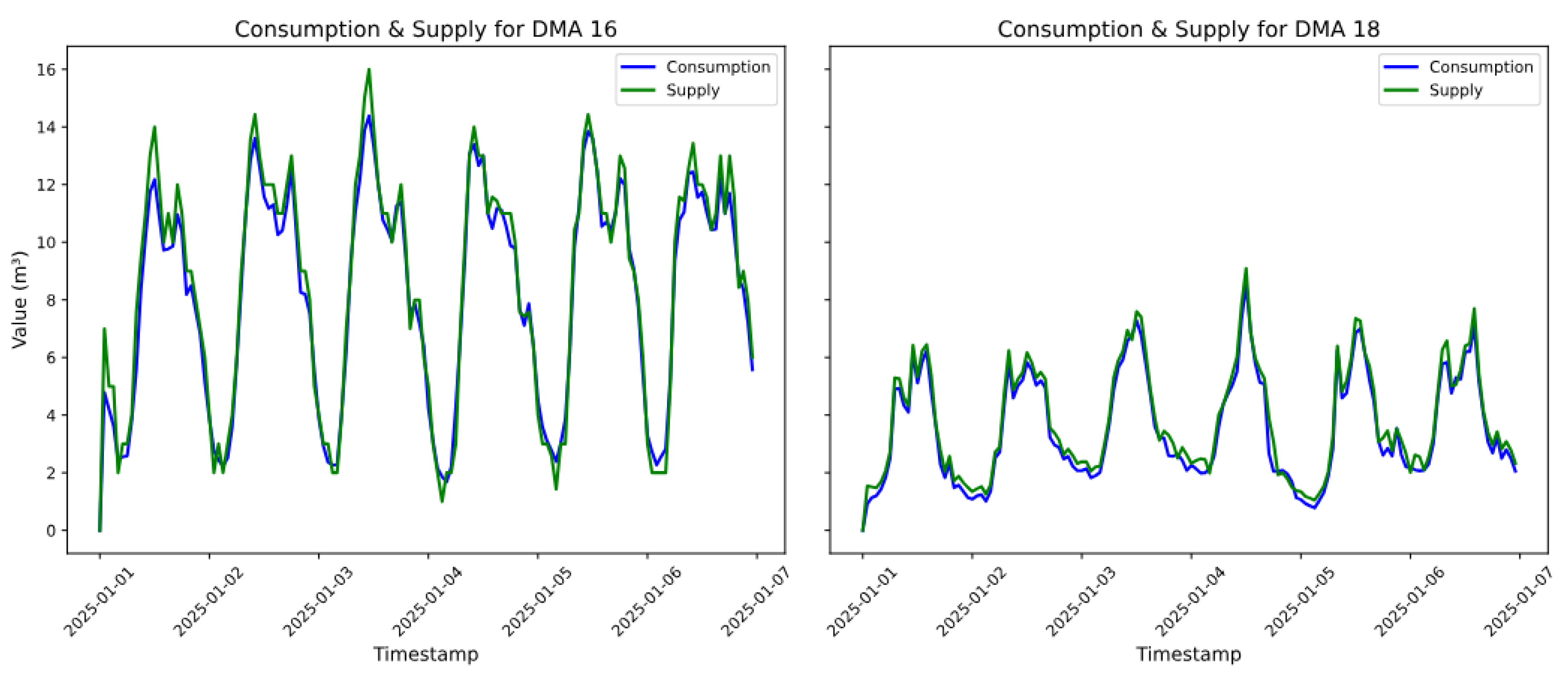

In both simulated and real leak datasets, supply and consumption show strong initial correlation across DMAs (

Figure 12 and

Figure 13). In the simulated case, supply aligns with consumption until a leak is introduced—at the 11

th hour for DMA 18 and DMA 08—after which observed supply (black line) exceeds consumption (blue line), indicating water loss. Similarly, in the real dataset, divergence begins at the 12

th hour, showcasing an actual leak. In both cases, estimated supply (dotted lines) continues to track consumption, highlighting the models’ ability to detect leaks via deviation analysis.

Quantitative evaluation of Experiment III and IV are conducted with the help of Confusion matrices, ROC-curve with AUC-scores and standard classification metrics mentioned in the

Section 4.5.

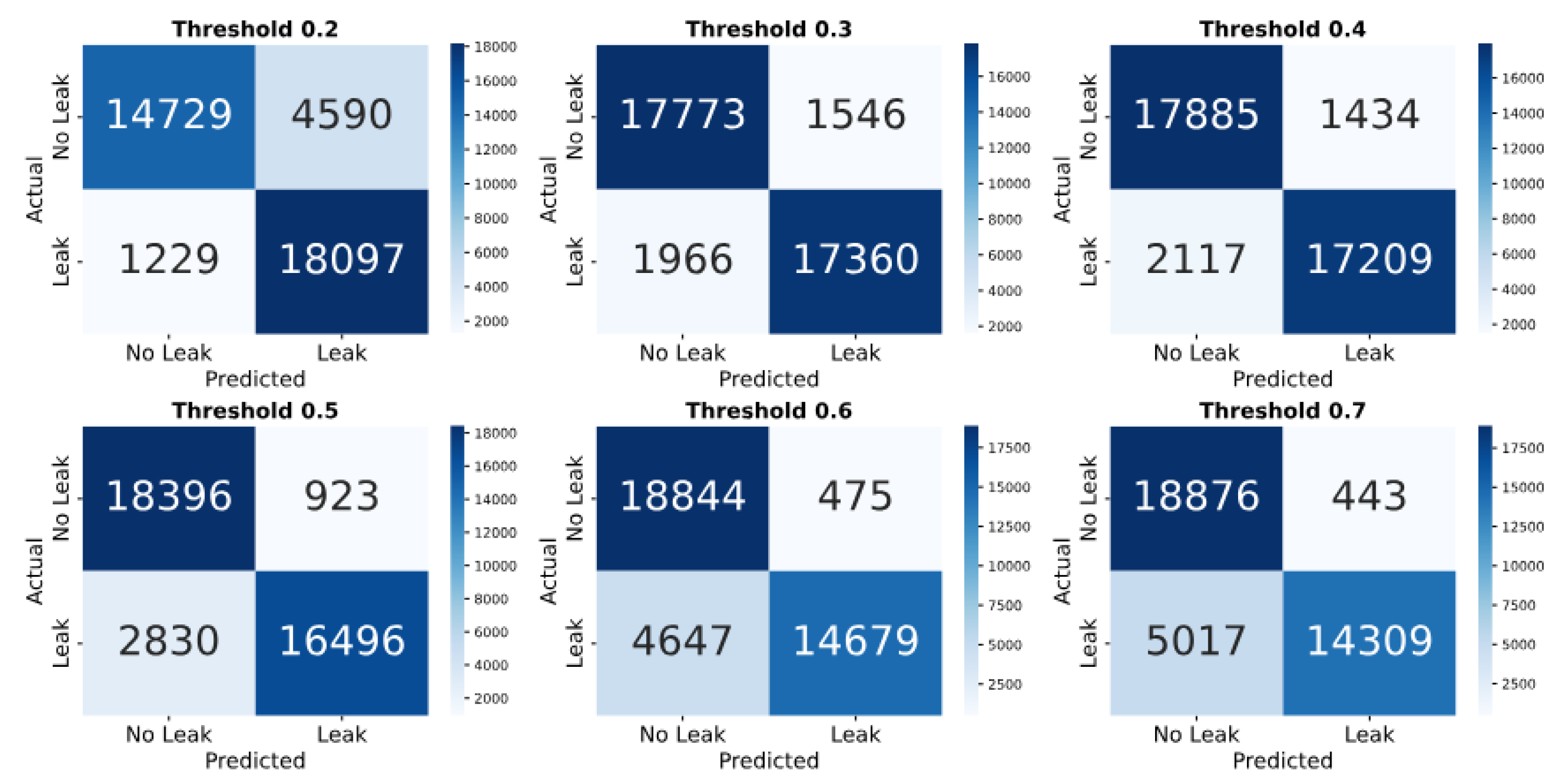

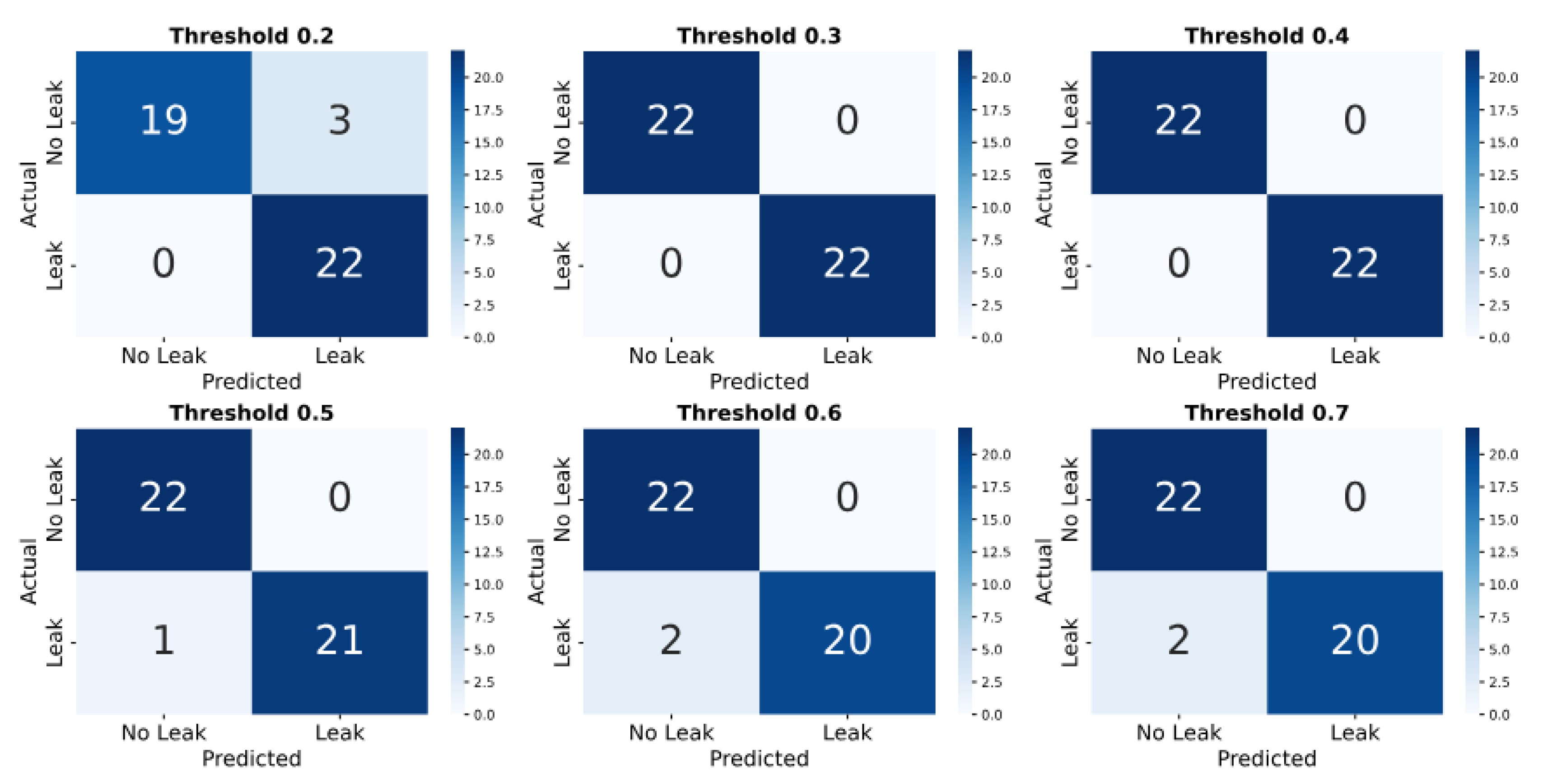

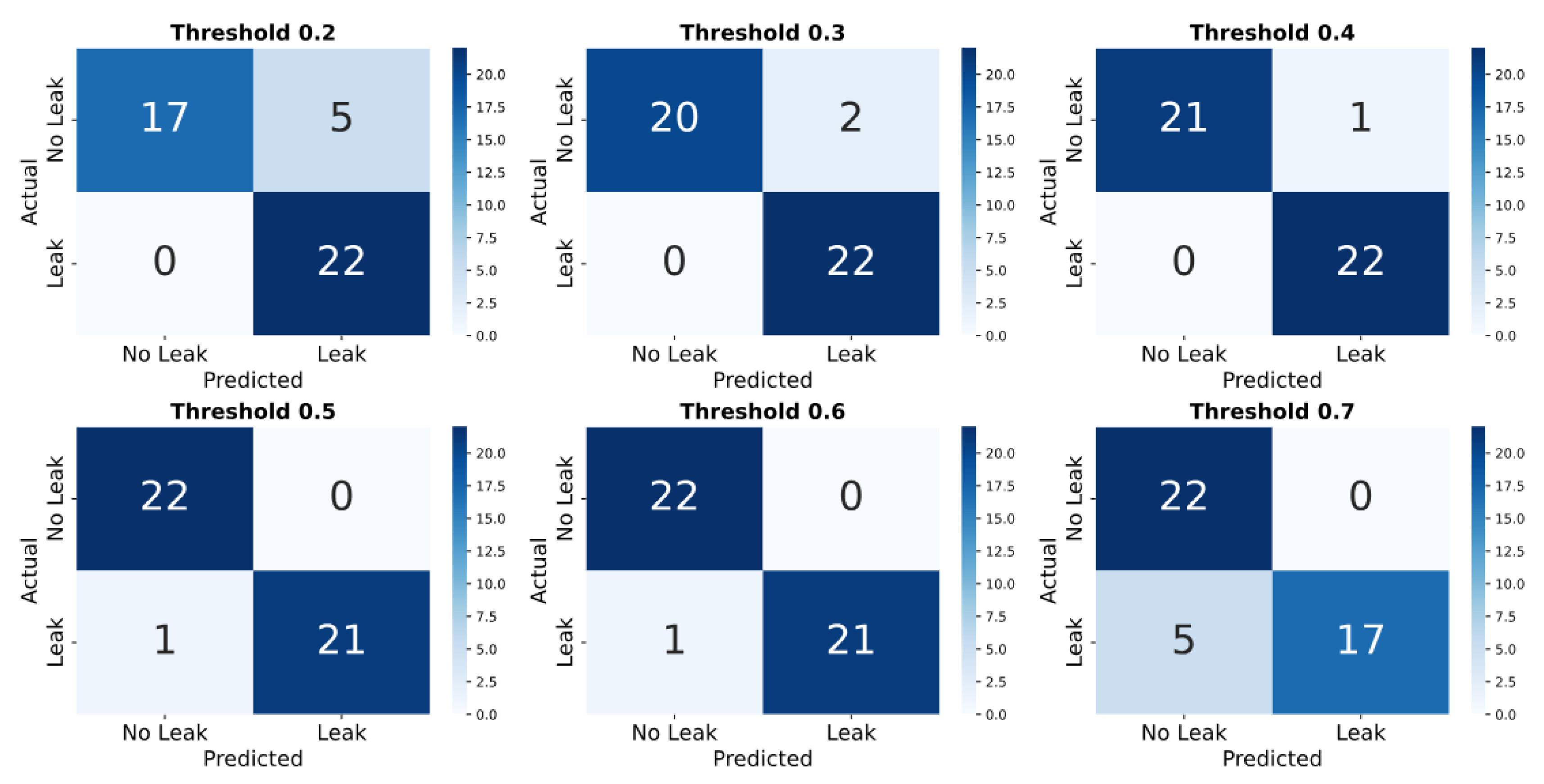

The confusion matrix analysis (

Figure 14) shows how threshold adjustments affect leak detection performance. In the simulated case, a low threshold (0.2) detects most leaks (18097) and no-leaks (14729) but results in 4590 false alarms. Raising the threshold to 0.7 reduces false alarms to 443 but increases missed leaks to 5017. At the balanced threshold of 0.5, the model correctly identifies 16,496 leaks and 18,396 no-leaks, with 923 false alarms and 2,830 missed leaks. Whereas in the real dataset (

Figure 15), at a 0.2 threshold, the model detects 22 leaks and 19 no-leaks, with 3 false alarms. From thresholds 0.3 to 0.7, the model produces 0 false alarms. However, missed leaks increase slightly–from none at 0.3 to 2 at 0.7.

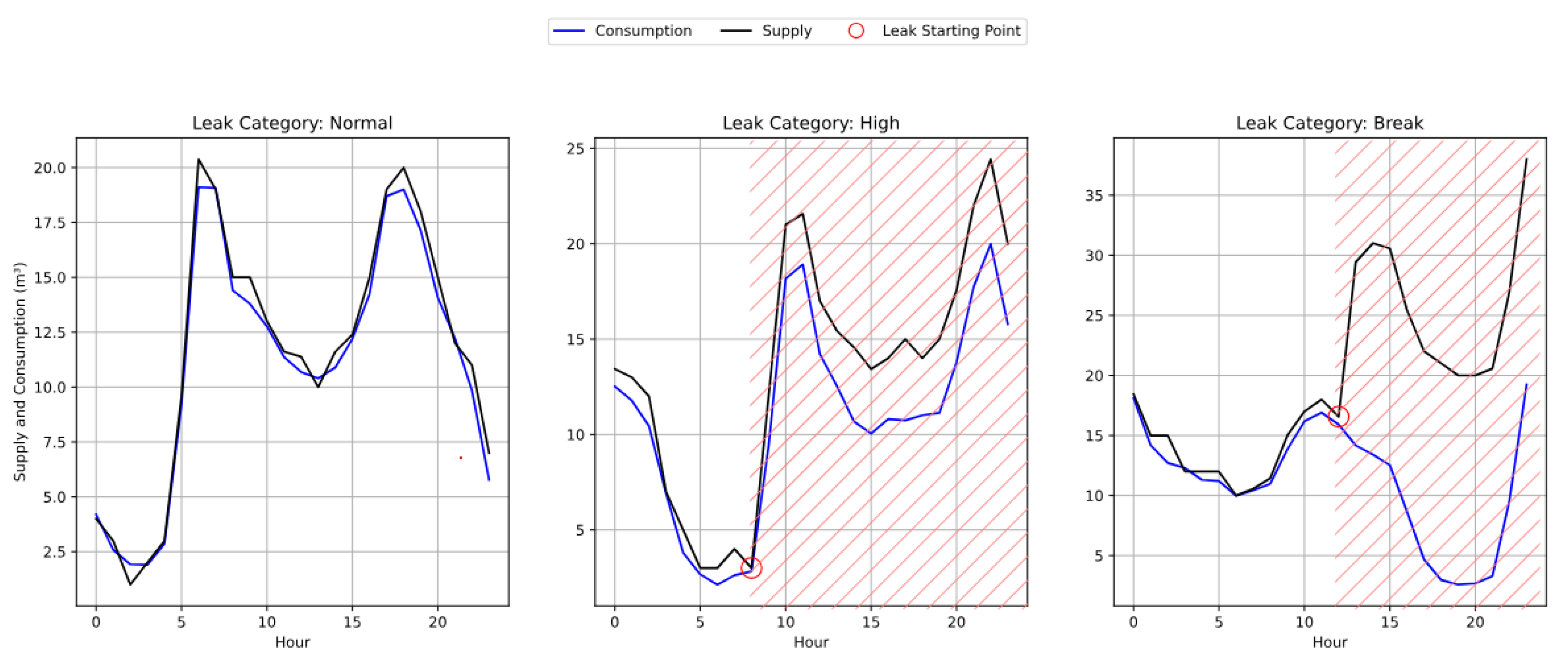

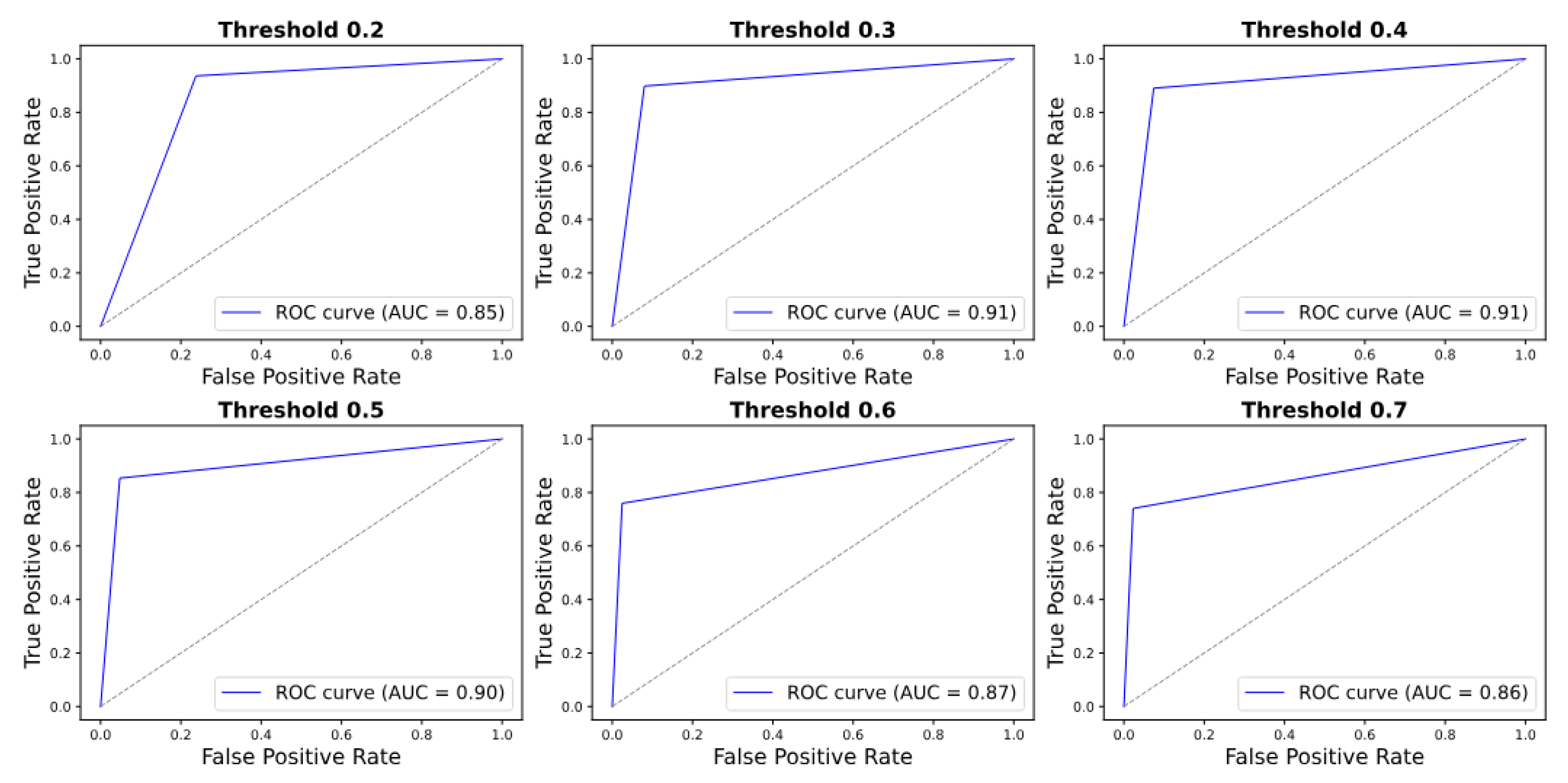

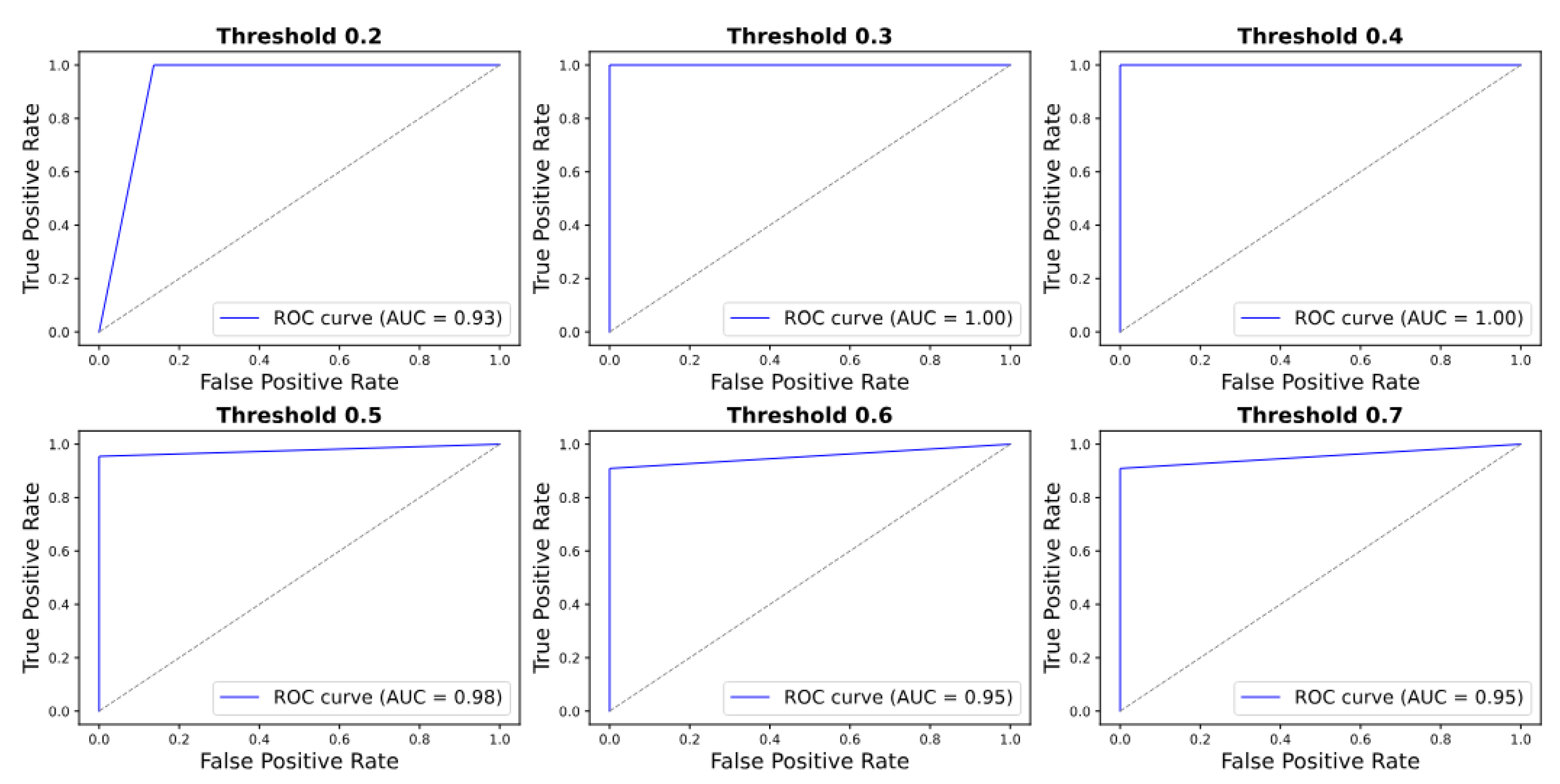

The ROC curve analysis (

Figure 16 and

Figure 17) demonstrates consistent model performance across thresholds. For the simulated dataset, the AUC peaks at 0.91 for thresholds of 0.3 and 0.4, with a marginal decrease to 0.86 at 0.7. In the real dataset, the AUC remains exceptionally high—reaching 1.00 at 0.3 and 0.4 and exceeding 0.92 for all thresholds—indicating robust and reliable classification.

The classification report for the simulated leak dataset (

Table 4) shows that the thresholds 0.3 and 0.4 offer the best balance, with 0.91 accuracy and F1 scores for both classes. From threshold 0.2 to 0.7, leak precision rises from 0.80 to 0.97, while recall drops from 0.94 to 0.74. No-leak precision falls from 0.92 to 0.79, and recall increases from 0.76 to 0.98, reflecting a trade-off where higher thresholds reduce false alarms but increase missed leaks.

For the real leak dataset (

Table 5) enhanced performance is observed. At the 0.3 and 0.4 thresholds, all metrics reach 1.00. At threshold 0.2, accuracy is 0.93 with leak precision at 0.88 and no-leak precision at 1.00. Above 0.4, leak recall slightly falls to 0.91 at 0.7, while precision remains high (0.92–1.00), maintaining reliable detection with minimal false alarms.

In case of

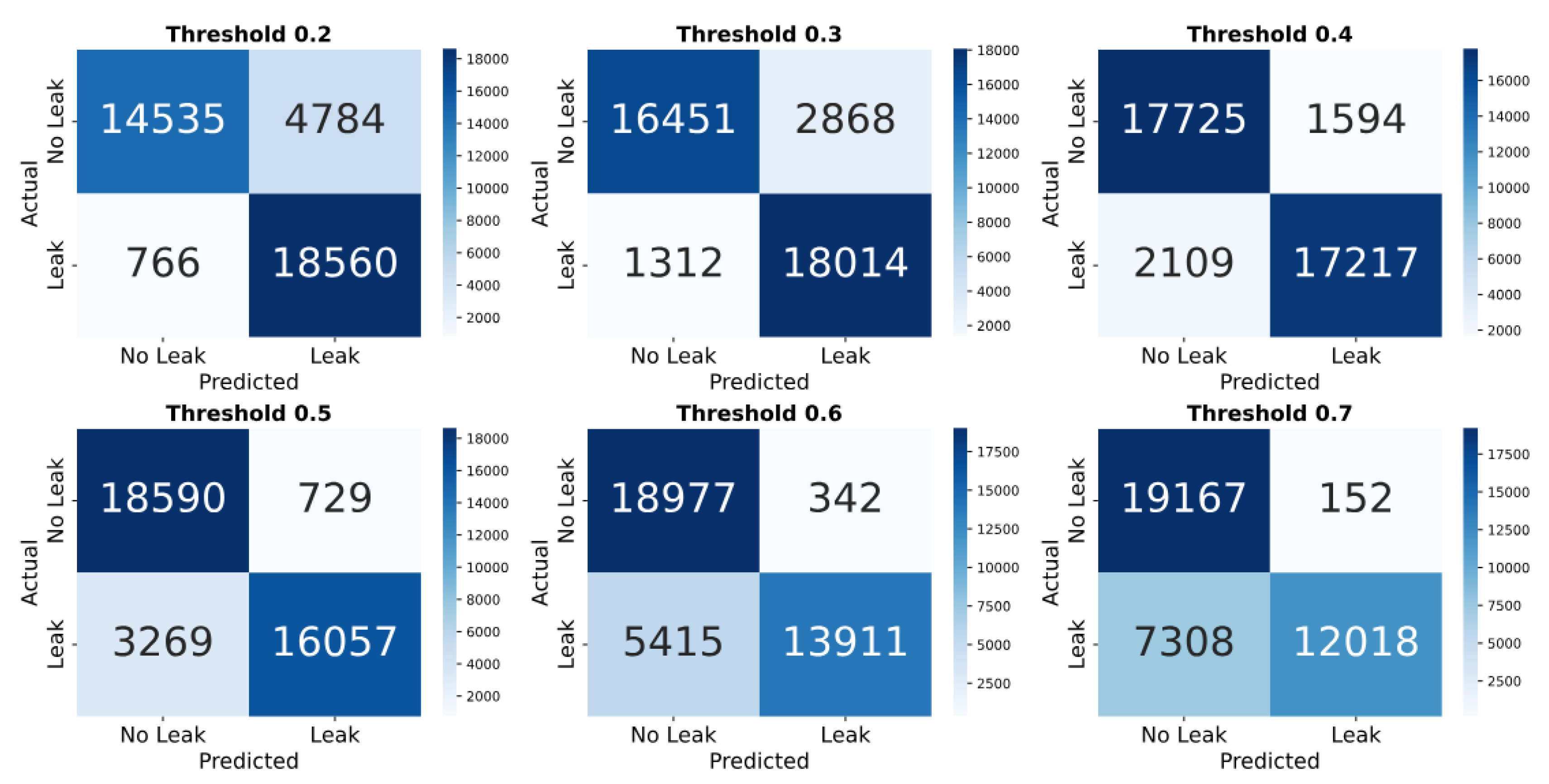

Experiment IV, performances are illustrated as follows for PS-approach. The confusion matrices for the simulated dataset highlight a trade-off between leak detection and false alarms as the threshold increases (refer to

Figure 18). At 0.2, the model detects 18560 leaks and 14535 no-leaks, but with 4784 false alarms and 766 missed leaks. As the threshold rises to 0.7, false alarms drop to 152, while missed leaks increase to 7308.

In the real dataset (

Figure 19), the performances using PS approach are observed as follows. At 0.2, it detects all 22 leaks with 5 false alarms. By threshold 0.4, false alarms drop to 1 with perfect leak detection. At 0.5–0.6, one leak is missed and no false alarms occur. At 0.7, 5 leaks are missed, with 17 detected and no false alarms.

At lower thresholds (e.g., 0.2), both MV and PS focus on detecting every possible leak, achieving perfect or near-perfect recall on the real dataset and around 0.9 on the simulated one. However, this strong sensitivity also increases false positives, especially in the simulated data, which lowers precision. In contrast, the non-leak class shows high precision but lower recall, indicating that the models become biased towards when labeling samples as leaks than non-leak while prioritizing leak detection.

When the threshold increases to 0.3–0.4, both methods achieve a better balance between precision and recall. False positives drop sharply, and F1-scores for leak and non-leak classes stabilize around 0.9 in the simulated dataset. The ROC-AUC remains strong (about 0.9), and in the real dataset, both MV and PS achieve almost perfect classification, with precision, recall, and F1-scores reaching 1.00. This indicates that both methods perform very reliably under real dataset where the distinction between leak and non-leak patterns is clearer due to only high severity leak-categories being present in the samples.

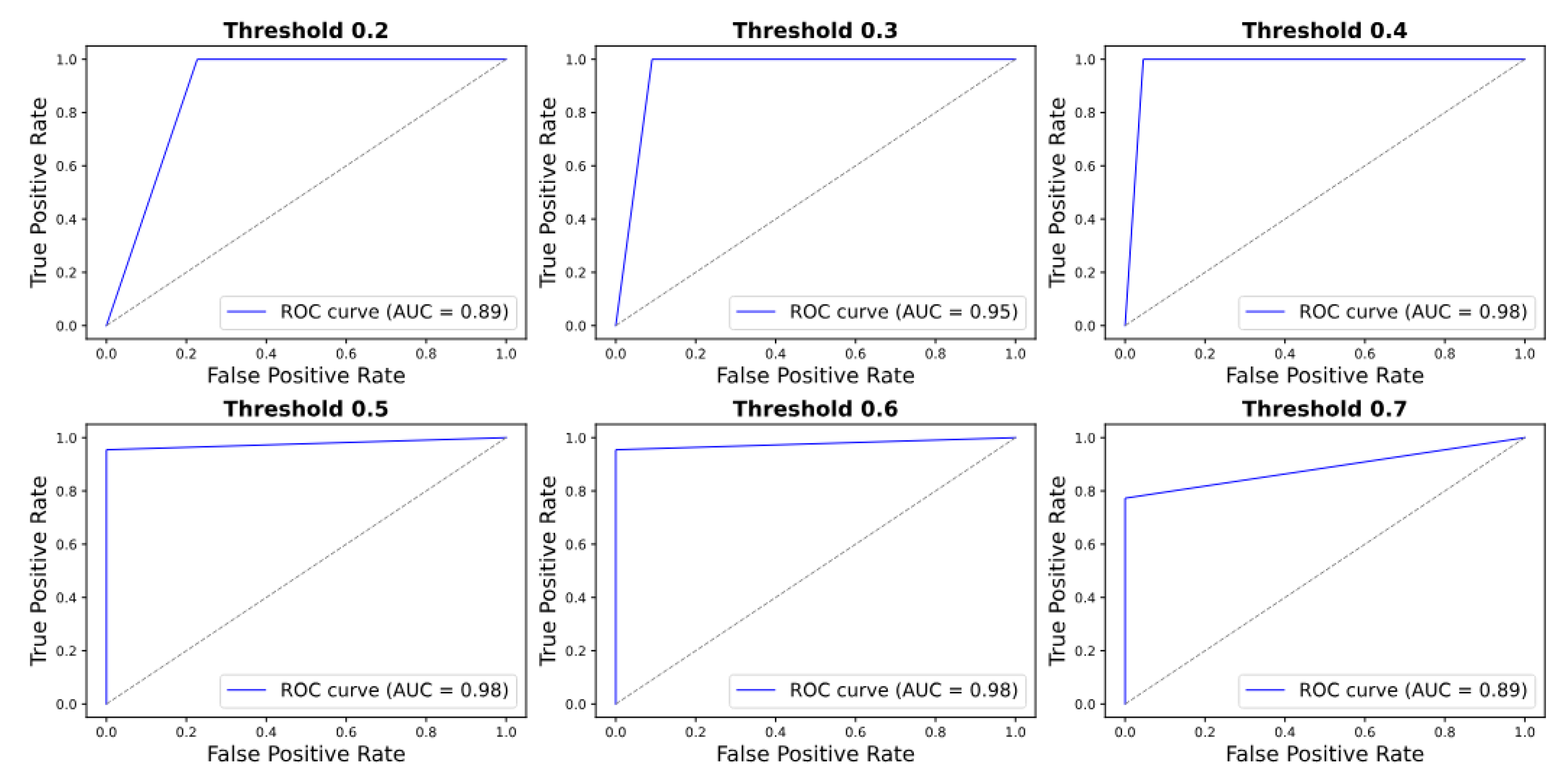

Figure 20.

Exp IV: PS Performance Evaluation via ROC Curves (Simulated Leaks)

Figure 20.

Exp IV: PS Performance Evaluation via ROC Curves (Simulated Leaks)

Figure 21.

Exp IV: PS Performance Evaluation via ROC Curves (Real Leaks)

Figure 21.

Exp IV: PS Performance Evaluation via ROC Curves (Real Leaks)

At higher thresholds (above 0.5), the models become more conservative, favoring precision over recall. Leak precision rises above 0.95, while recall decreases below 0.8, showing that the models aim to reduce false alarms but may miss some true leaks. Despite this trade-off, non-leak recall remains high (around 0.95–0.98), and real-world results continue to be stable – precision stays perfect, and recall decreases only slightly. Hence the comprehensive analysis of performance in both the experiments – Experiment III and IV illustrates the traditional trade-off between sensitivity and specificity of anomaly detection. The results showcase the optimal operating point where the balance can be obtained. The higher resilience in performance observed in case of real data is due to only ’High’ and ’Break’ category leaks being present in the dataset, where the deviation pattern is clearer.

Table 6.

Exp IV: PS Classification Report (Simulated Leaks)

Table 6.

Exp IV: PS Classification Report (Simulated Leaks)

| Threshold |

Class |

Precision |

Recall |

F1-score |

Accuracy |

Support |

| 0.2 |

No Leak |

0.95 |

0.75 |

0.84 |

0.86 |

19319 |

| |

Leak |

0.80 |

0.96 |

0.87 |

|

19326 |

| 0.3 |

No Leak |

0.93 |

0.85 |

0.89 |

0.89 |

19319 |

| |

Leak |

0.86 |

0.93 |

0.90 |

|

19326 |

| 0.4 |

No Leak |

0.89 |

0.92 |

0.91 |

0.90 |

19319 |

| |

Leak |

0.92 |

0.89 |

0.90 |

|

19326 |

| 0.5 |

No Leak |

0.85 |

0.96 |

0.90 |

0.90 |

19319 |

| |

Leak |

0.96 |

0.83 |

0.89 |

|

19326 |

| 0.6 |

No Leak |

0.78 |

0.98 |

0.87 |

0.85 |

19319 |

| |

Leak |

0.98 |

0.72 |

0.83 |

|

19326 |

| 0.7 |

No Leak |

0.72 |

0.99 |

0.84 |

0.81 |

19319 |

| |

Leak |

0.99 |

0.62 |

0.76 |

|

19326 |

Table 7.

Exp IV: PS Classification Report (Real Leaks)

Table 7.

Exp IV: PS Classification Report (Real Leaks)

| Threshold |

Class |

Precision |

Recall |

F1-score |

Accuracy |

Support |

| 0.2 |

No Leak |

1.00 |

0.77 |

0.87 |

0.89 |

22 |

| |

Leak |

0.81 |

1.00 |

0.90 |

|

22 |

| 0.3 |

No Leak |

1.00 |

0.91 |

0.95 |

0.95 |

22 |

| |

Leak |

0.92 |

1.00 |

0.96 |

|

22 |

| 0.4 |

No Leak |

1.00 |

0.95 |

0.98 |

0.98 |

22 |

| |

Leak |

0.96 |

1.00 |

0.98 |

|

22 |

| 0.5 |

No Leak |

0.96 |

1.00 |

0.98 |

0.98 |

22 |

| |

Leak |

1.00 |

0.95 |

0.98 |

|

22 |

| 0.6 |

No Leak |

0.96 |

1.00 |

0.98 |

0.98 |

22 |

| |

Leak |

1.00 |

0.95 |

0.98 |

|

22 |

| 0.7 |

No Leak |

0.81 |

1.00 |

0.9 |

0.89 |

22 |

| |

Leak |

1.00 |

0.77 |

0.87 |

|

22 |

6.2.1. MV vs PS

Both MV and PS exhibit strong overall agreement in performance across simulated and real datasets but differ in how they balance precision and recall at varying thresholds.

At lower thresholds (0.2–0.4), MV provides more stable and balanced performance, maintaining higher leak precision and comparable recall, while PS favors higher sensitivity at the cost of more false positives. In the real dataset, both methods achieve perfect leak recall, though MV consistently attains higher precision and F1-scores, reflecting fewer false alarms and better overall classification balance.

As the threshold increases (0.5–0.7), MV demonstrates greater robustness and slower performance degradation compared to PS. MV sustains higher precision and accuracy with moderate recall loss, whereas PS becomes increasingly conservative—boosting leak precision but sharply reducing recall and overall F1-scores. On real data, MV retains its stability even at higher thresholds, achieving balanced precision–recall values and fewer false detections than PS.

Overall, MV achieves a superior trade-off between sensitivity and specificity across datasets, offering more consistent and dependable performance. PS performs competitively when minimizing false positives is the top priority, but MV’s balanced and resilient behavior makes it more suitable for practical leak detection scenarios where missing true leaks is costlier than occasional false alarms.

6.2.2. Optimal Threshold for Leak Decision

The leak decision threshold plays a critical role in shaping the performance of both the MV and PS strategies. Lower values of cause the system to classify even mild deviations as leaks. With lower , recall is high because nearly all leak events are detected; however, the rate of false positives increases, particularly in the simulated dataset where leak signatures may overlap more strongly with background variability. In contrast, the real dataset exhibits better class separability, resulting in fewer false alarms at comparable threshold levels.

As the threshold is increased into a mid-range (), both MV and PS achieve a more balanced trade-off between sensitivity and reliability. In this range, leak precision and recall remain simultaneously high, and the number of false positives decreases substantially. For the real dataset in particular, this threshold region yields near-perfect performance, as reflected in high F1-scores and ROC-AUC values approaching 0.98.

Further increasing the threshold () leads to a more conservative decision rule. Precision remains high because only the most pronounced anomalies exceed the threshold, but recall decreases as smaller or short-duration leaks are not detected. This results in fewer false positives but a reduction in overall discriminative balance.

In summary, threshold selection should align with operational priorities: lower thresholds when maximizing leak detection is critical, mid-range thresholds when balanced performance is desired, and higher thresholds when minimizing false alarms is more important than detecting every leak event.

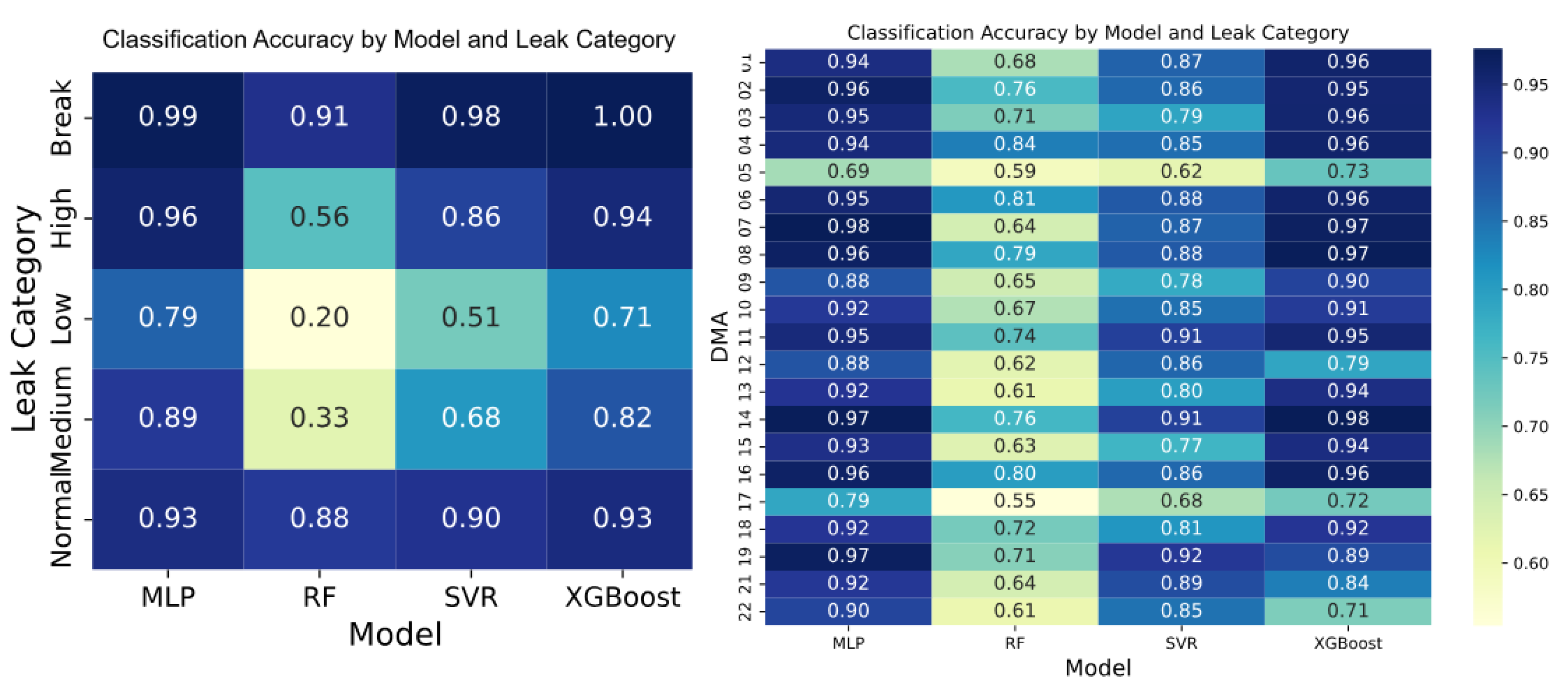

6.3. Impact of Ensembling on Leak Detection Accuracy

The impact of ensembling multiple regression models can be assessed by taking into account predicted supply of individual regression models as the basis for deviation analysis from observed supply. This analysis is carried out on simulated dataset as leaks of various categories are present in simulated-leak dataset, in contrast to the real-leak dataset. As shown in

Figure 22, performance across leak categories varied significantly when using individual models, particularly for medium and low-severity leaks. All models demonstrated strong performance in detecting

Break-type leaks (scores: 0.91–1.00) and reliably identified

Normal operating conditions, with classification scores in the range of 0.88–0.93.

However, their effectiveness dropped notably for other critical categories. The RF model scored as low as 0.56 in High leaks, and RF and SVR scored 0.33 and 0.68 in Medium leaks, respectively. The Low leaks were the most difficult to detect (the highest RF was only 0.20 and the highest SVR was only 0.51). These inconsistencies underscore the limitations of relying solely on individual models, especially their tendency to underperform on less frequent or more ambiguous leak types. These findings are corroborated by the individual DMA-level analysis (

Figure 22), where, as discussed in

Section 6.1, MLP and XGBoost emerged as the most reliable models for estimating water supply, directly enhancing leak detection capabilities. Both models consistently achieved over 0.90 accuracy in detecting leaks across most DMAs, demonstrating strong generalization to underlying supply patterns. In contrast, RF performed poorly, failing to exceed 0.81 accuracy in most DMAs (except DMA 04), while SVR, though more competitive than RF, achieved an average accuracy of 0.82—slightly lower than the 0.88 average attained by MLP and XGBoost. These variations suggest that some models are more sensitive to data quality and local noise at the DMA level, resulting in less stable and less reliable detection performance.

But a key observation is that, for DMA 12, 19, 21 and 22, higher classification accuracy is achieved using the prediction of SVR compared to that from XGBoost. This highlights the complementary effect of integrating another model’s opinion through an ensembling mechanism, to overcome limitation of a model whose performance can deviate in a different data scenario. Thus, the ensembling process increases confidence and robustness in classification by incorporating predictions from other models. Furthermore, the limitations observed across both leak categories and individual DMAs are effectively addressed by the ensembling approach, which integrates outputs from multiple models through metric-level fusion (MV and PS) and model-level weighting based on accuracy. This strategy leverages the strengths of each base learner while mitigating their individual weaknesses.

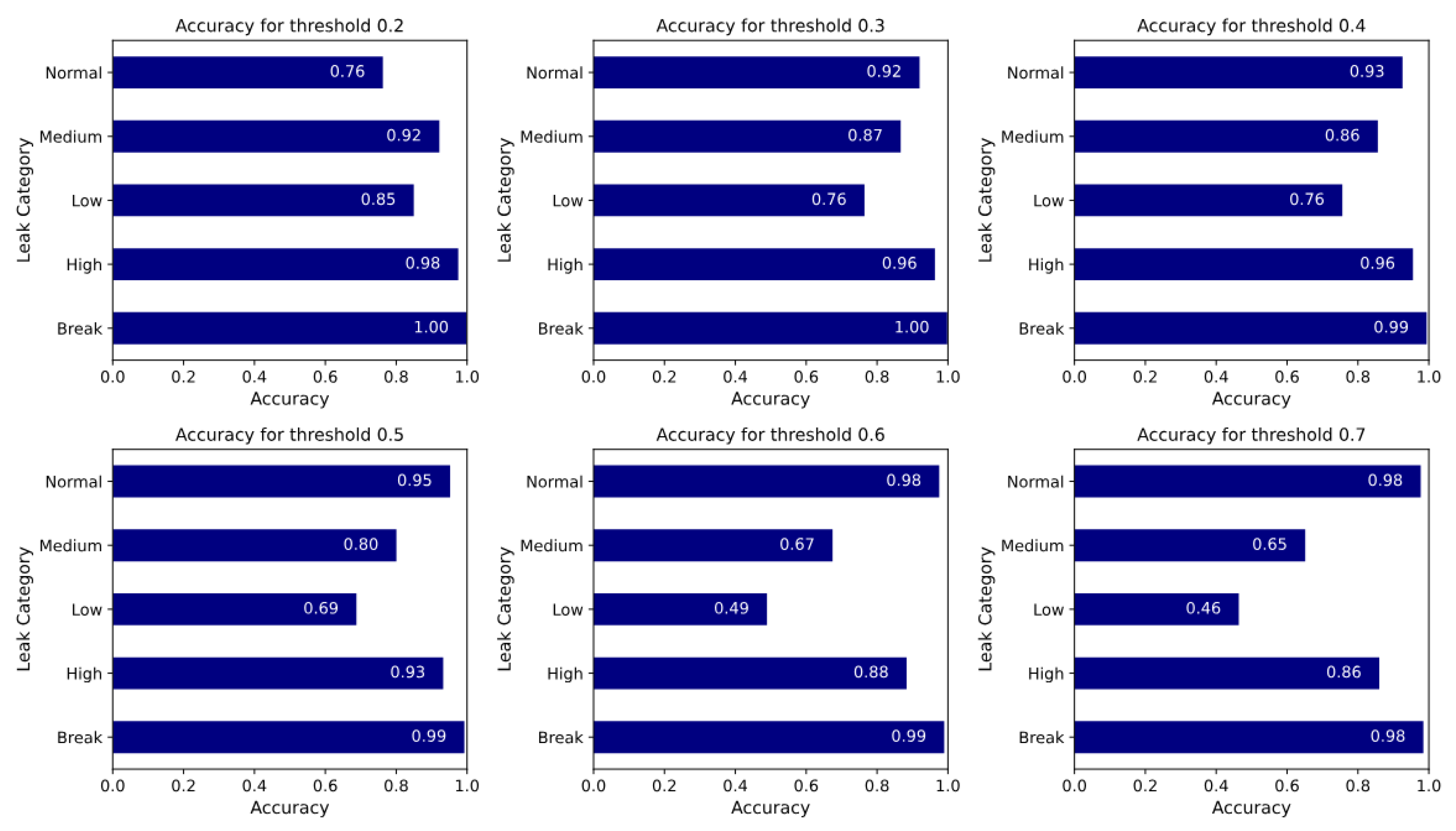

After applying the ensemble method (

Figure 23), the model exhibited substantially more stable and reliable performance across all leak categories. It consistently maintained near-perfect accuracy (>0.98) in detecting Break leaks across all threshold settings, ensuring dependable recognition of the most severe failures. Detection of high severity leaks also improved significantly, with accuracy never falling below 0.86—even as the decision threshold increased from 0.2 to 0.7. Although this reflects a slight trade-off between sensitivity and specificity, the ensemble preserved high detection rates for critical leak events. Classification of Normal conditions showed notable improvement as well. Accuracy increased from 0.76 at threshold 0.2 to above 0.92 at higher thresholds, suggesting that the ensemble becomes more confident and specific in identifying normal operations as the decision boundary tightens. However, this improved specificity came at the expense of sensitivity to less severe leaks. The Medium category remained relatively stable (>0.80) up to threshold 0.5 but declined below 0.70 beyond that. The Low category was the most sensitive to threshold changes, with accuracy dropping from 0.85 at threshold 0.2 to 0.46 at threshold 0.7.

Overall, these findings underscore a critical insights for ensemble model design. Low-category leaks are inherently more difficult to detect, both before and after ensembling. The highest individual accuracy for the Low category leaks before ensembling was 0.79, achieved by the MLP model. With ensembling, the maximum classification accuracy for the Low category reached only 0.85, and this came at the cost of reducing the accuracy for the Normal class to 0.76. Therefore, in practical deployment, a threshold of 0.76 appears to be the optimal trade-off point, as it preserves reasonable sensitivity to low-severity leaks without compromising classification of other categories.

Altogether, these results demonstrate the tolerance of the ensemble approach against model-dependent sensitivities and noisy measurements. It reduces performance fluctuation among the leak categories and DMAs and enhances overall reliability.

6.4. Kalman-View and Neural Network MoE-View of the Proposed Framework

The proposed framework can be understood as an innovation-based monitoring system, similar in spirit to Kalman filtering. Each regression model acts as a predictor of the expected DMA supply under normal hydraulic behavior. The deviation between predicted and observed supply forms an innovation signal, whose statistical properties rather than raw residuals are monitored to identify deviations from nominal operation. Under normal conditions, these innovation statistics remain stable and consistent with their training-time behavior.

When a new leak emerges, the relationship between consumption and supply changes, and the innovation statistics shift accordingly. The metric-level fusion acts as an innovation gate, deciding whether each model finds its innovation inconsistent with expected behavior. The model-level weighted fusion then combines these innovation evidences, analogous to reliability-weighted multi-model filtering. Finally, thresholding the aggregated anomaly score corresponds to a hypothesis test on the innovation process, where exceeding the threshold indicates a statistically significant departure from nominal hydraulics and therefore a potential leak. In this sense, the entire pipeline behaves as a Kalman-style innovation detector, where expected behavior comes from trained regression models. Here the deviations are characterized through innovation statistics, and the ensemble process provides robust decision making.

The framework can also be interpreted as a Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) architecture. Each regression model acts as an expert that estimates supply from consumption for a DMA. Instead of learning neural hidden layers, the framework computes simple statistical measures describing how well each expert’s prediction matches the observed supply. These statistics act as a lightweight representation of residual behavior.

A deterministic fusion rule converts the metric vector into a per-model anomaly score, and the RMO weights serve as fixed attention coefficients, emphasizing experts that historically predicted reasonably for the DMA. The weighted combination of expert scores then produces a single anomaly score, which is finally thresholded to produce the leak decision.

Viewed this way, the pipeline resembles a transparent, hand-crafted mixture-of-experts model, where each expert contributes according to its reliability and the “gating mechanism” is implemented through RMO weights rather than learned parameters.