Submitted:

20 January 2026

Posted:

21 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

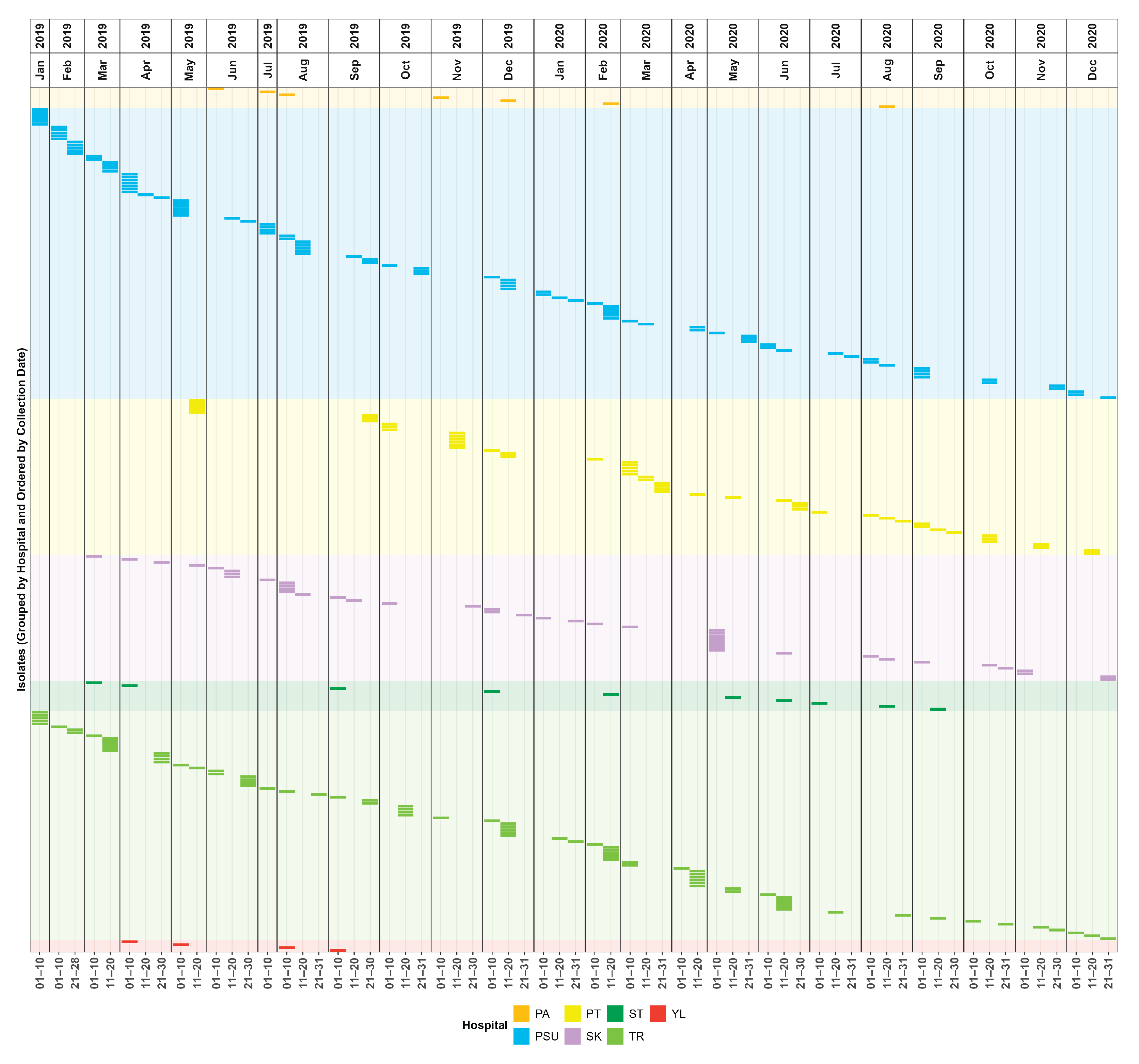

2.1. Surveillance Period and Clinical Characteristics

2.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Profiles

2.3. Genome Assembly Quality

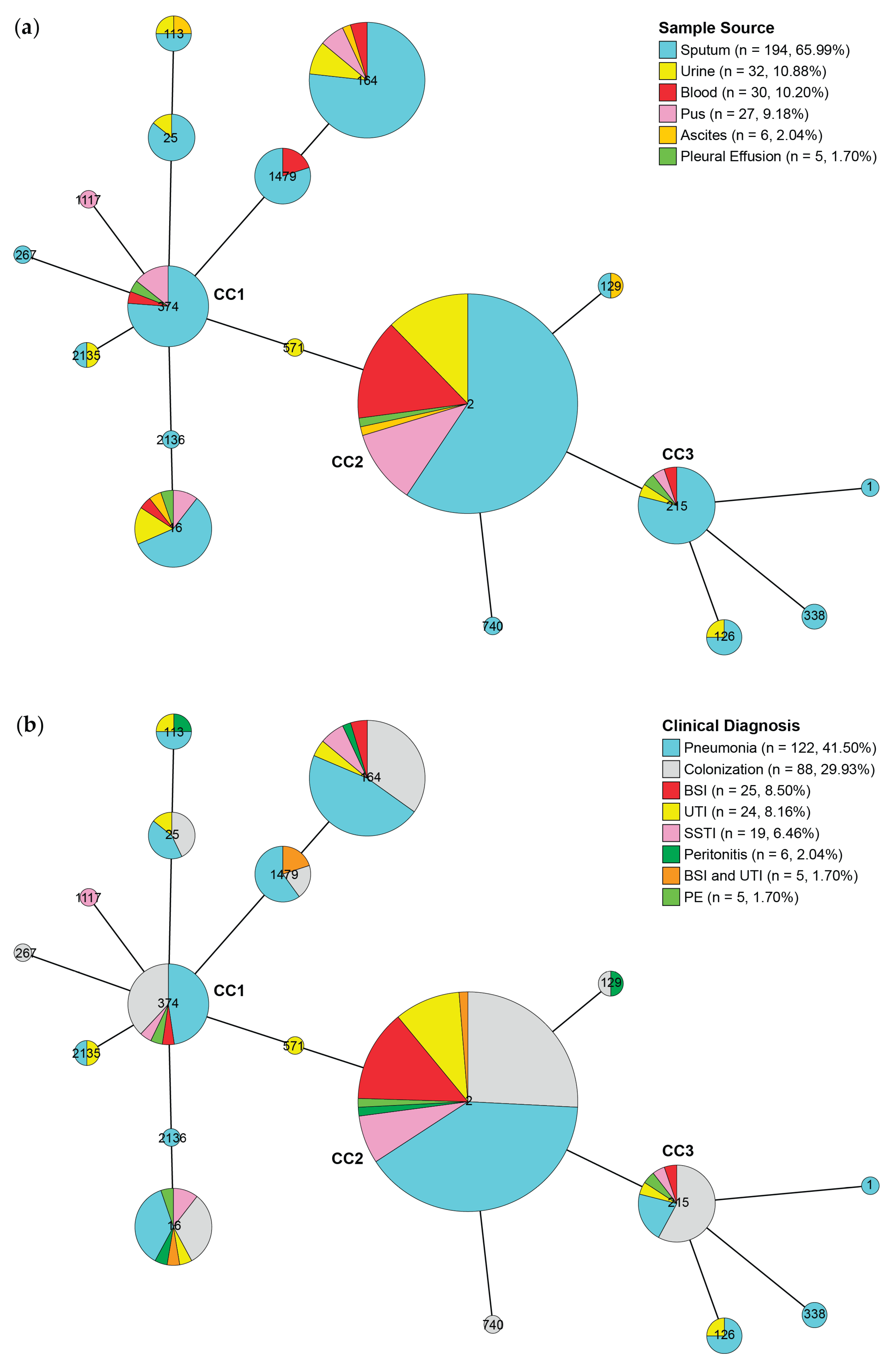

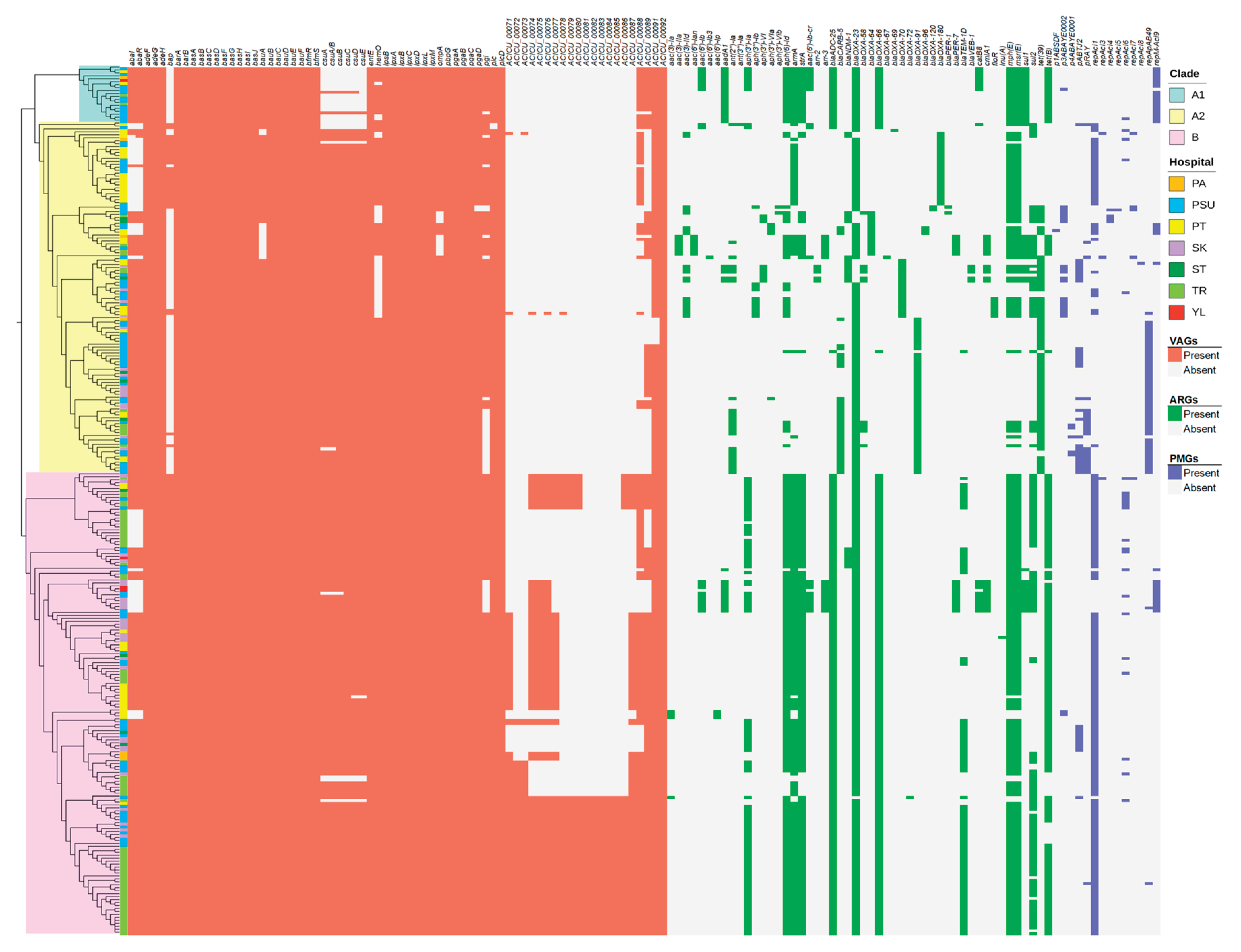

2.4. Identification of Sequence Types (STs), Virulence-Associated Genes (VAGs), Antimicrobial Resistance Genes (ARGs), and Plasmid Marker Genes (PMGs)

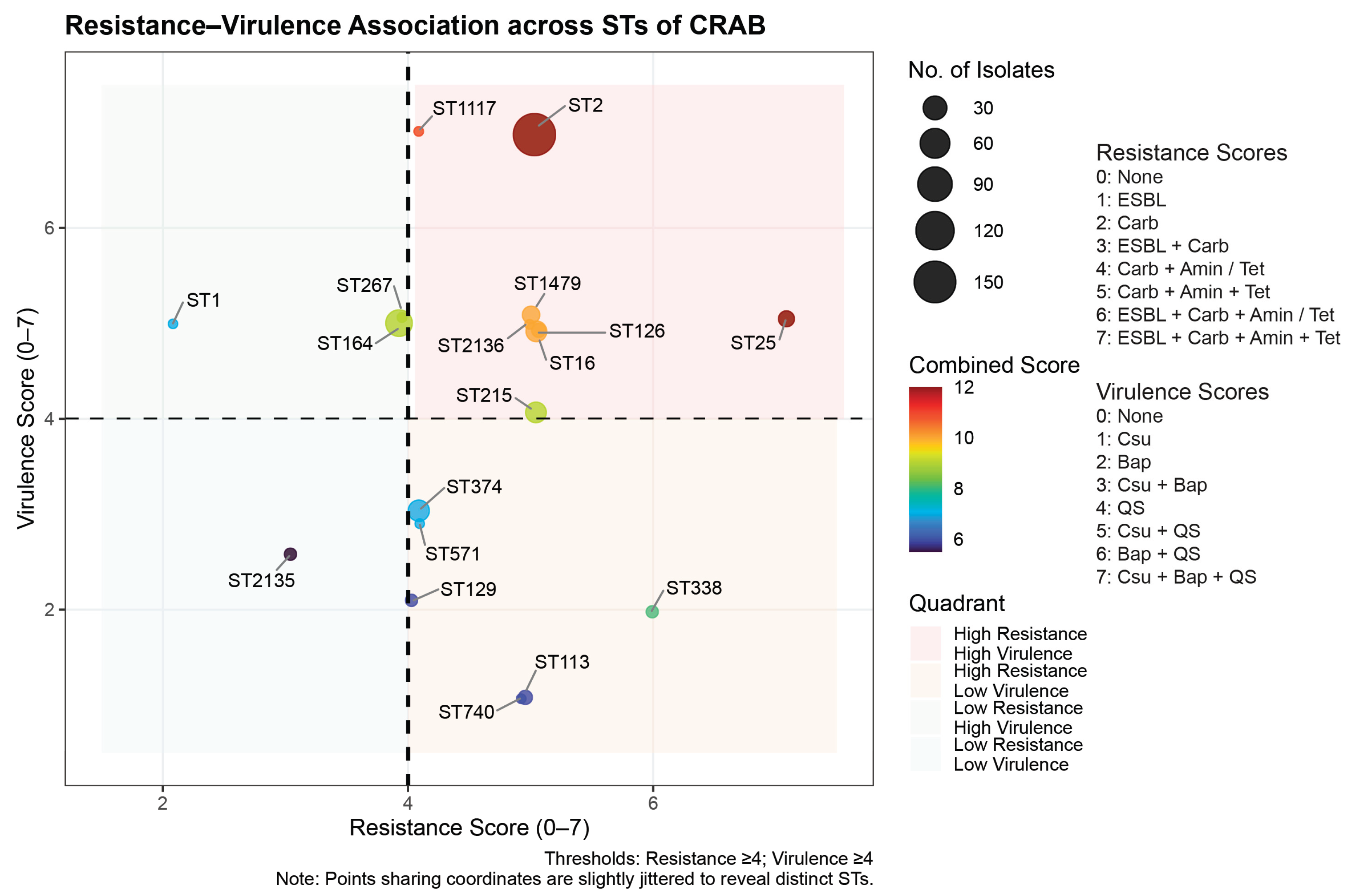

2.5. Association Between Resistance and Virulence Across the STs

2.6. Association Among Hospitals, Clinical Diagnoses, STs, Carbapenem Resistance-Associated Genes, and Predicted PMGs.

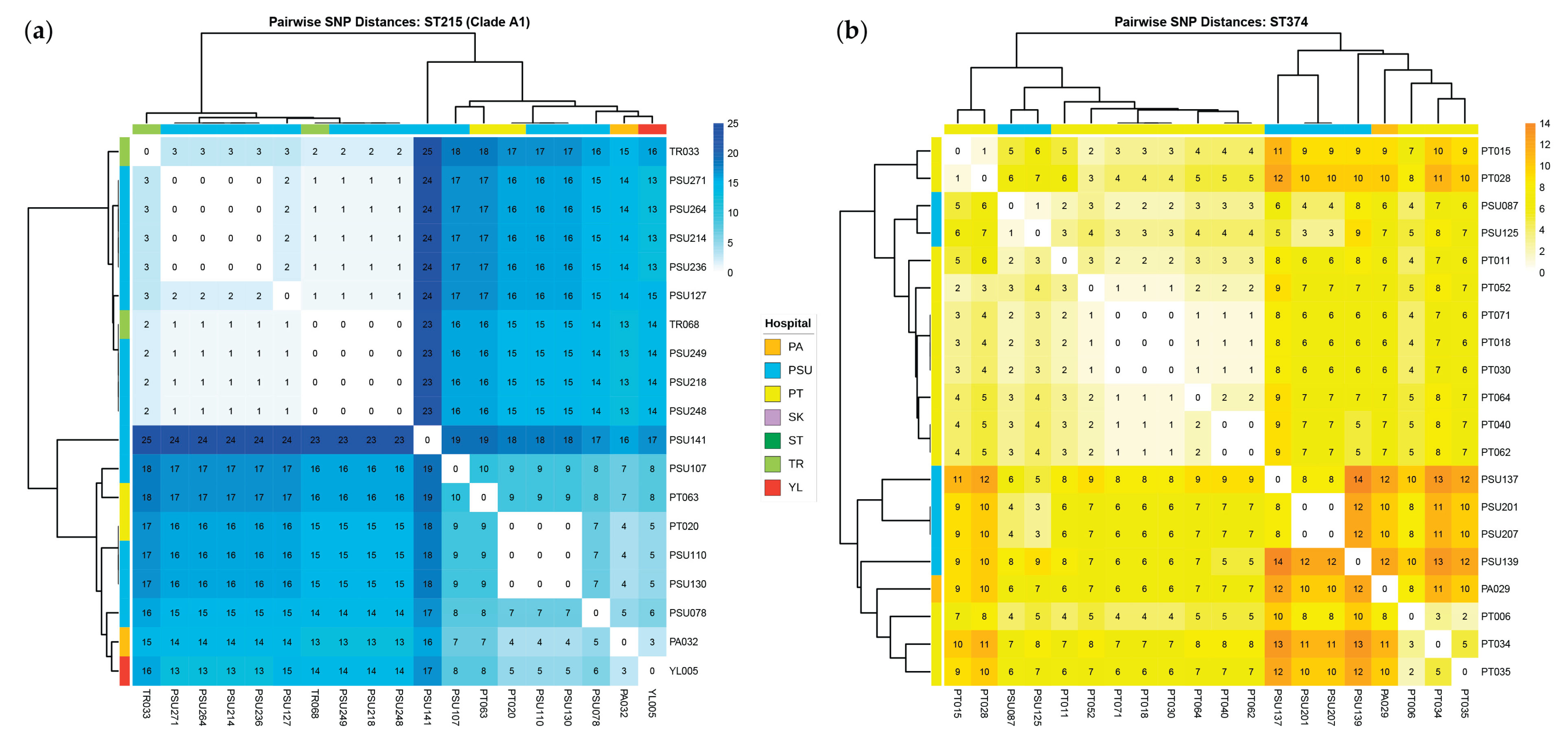

2.7. Comprehensive Comparative Genomics

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Clinical Isolates

4.2. Genomic DNA Extraction and Whole-Genome Sequencing

4.3. De Novo Assembly, Species Confirmation, and Genome Annotation

4.4. Downstream Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Salam, M.A.; Al-Amin, M.Y.; Salam, M.T.; Pawar, J.S.; Akhter, N.; Rabaan, A.A.; Alqumber, M.A. Antimicrobial resistance: a growing serious threat for global public health. Healthcare (Basel) 2023, 11, 1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayobami, O.; Willrich, N.; Harder, T.; Okeke, I.N.; Eckmanns, T.; Markwart, R. The incidence and prevalence of hospital-acquired (carbapenem-resistant) Acinetobacter baumannii in Europe, Eastern Mediterranean and Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2019, 8, 1747–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- CDC. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019 (2019 AR Threats Report), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Atlanta, GA. 2019. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/Biggest-Threats.html (accessed on 04 January 2020).

- Poirel, L.; Nordmann, P. Carbapenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii: mechanisms and epidemiology. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2006, 12, 826–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabour, S.; Bantle, K.; Bhatnagar, A.; Huang, J.Y.; Biggs, A.; Bodnar, J.; Dale, J.L.; Gleason, R.; Klein, L.; Lasure, M.; et al. Descriptive analysis of targeted carbapenemase genes and antibiotic susceptibility profiles among carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii tested in the Antimicrobial Resistance Laboratory Network-United States, 2017-2020. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e02828-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeighami, H.; Valadkhani, F.; Shapouri, R.; Samadi, E.; Haghi, F. Virulence characteristics of multidrug resistant biofilm-forming Acinetobacter baumannii isolated from intensive care unit patients. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolma, K.G.; Khati, R.; Paul, A.K.; Rahmatullah, M.; de Lourdes Pereira, M.; Wilairatana, P.; Khandelwal, B.; Gupta, C.; Gautam, D.; Gupta, M.; et al. Virulence characteristics and emerging therapies for biofilm-forming Acinetobacter baumannii: a review. Biology 2022, 11, 1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostyanev, T.; Xavier, B.B.; García-Castillo, M.; Lammens, C.; Acosta, J.B.-F.; Rodríguez-Baño, J.; Cantón, R.; Glupczynski, Y.; Goossens, H.; EURECA/WP1B Group. Phenotypic and molecular characterizations of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii isolates collected within the EURECA study. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2021, 57, 106345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, C.H.; Cunha, M.P.V.; de Barcellos, T.A.F.; Bueno, M.S.; de Jesus Bertani, A.M.; Dos Santos, C.A.; Nagamori, F.O.; Takagi, E.H.; Chimara, E.; de Carvalho, E.; et al. Genomic and phenotypic characterization of antimicrobial resistance in carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii hyperendemic clones CC1, CC15, CC79, and CC25. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 56, 106195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.H.; Jeong, H.; Sim, Y.M.; Lee, S.; Yong, D.; Ryu, C.-M.; Choi, J.Y. Using comparative genomics to understand molecular features of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii from South Korea causing invasive infections and their clinical implications. PloS one. 2020, 15, e0229416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, M.; Rashid, F.A.; Shukor, S.; Hashim, R.; Ahmad, N. Detection of carbapenem resistance genes from whole-genome sequences of Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from Malaysia. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2020, 2020, 5021064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wareth, G.; Linde, J.; Nguyen, N.H.; Nguyen, T.N.; Sprague, L.D.; Pletz, M.W.; Neubauer, H. WGS-Based Analysis of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in Vietnam and molecular characterization of antimicrobial determinants and MLST in Southeast Asia. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loraine, J.; Heinz, E.; Soontarach, R.; Blackwell, G.A.; Stabler, R.A.; Voravuthikunchai, S.P.; Srimanote, P.; Kiratisin, P.; Thomson, N.R.; Taylor, P.W. Genomic and phenotypic analyses of Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from tertiary care hospitals in Thailand. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nghiem, M.N.; Bui, D.P.; Ha, V.T.T.; Tran, H.T.; Nguyen, D.T.; Vo, T.T.B. Dominance of high-risk clones ST2 and ST571 and resistance island diversity in clinical Acinetobacter baumannii isolates from Hanoi, Vietnam. Microb. Genom. 2025, 11, 001500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kon, H.; Lurie-Weinberger, M.N.; Chen, D.F.; Laderman, H.; Temkin, E.; Lomansov, E.; Firan, I.; Aboalhega, W.; Raines, M.; Keren-Paz, A.; et al. Contribution of Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy for outbreak investigation of carbapenem-resistant. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 19, e0239225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L.W.; Forde, B.M.; Hurst, T.; Ling, W.; Nimmo, G.R.; Bergh, H.; George, N.; Hajkowicz, K.; McNamara, J.F.; Lipman, J.; et al. Genomic surveillance and intervention of a carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii outbreak in critical care. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornelsen, V.; Kumar, A. Update on multidrug resistance efflux pumps in Acinetobacter spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2021, 65, e0051421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upmanyu, K.; Haq, Q.M.R.; Singh, R. Factors mediating Acinetobacter baumannii biofilm formation. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2022, 3, 100131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, D.C.S.; Silveira, M.C.; Pribul, B.R.; Karam, B.R.S.; Picão, R.C.; Kraychete, G.B.; Pereira, F.M.; de Lima, R.M.; de Souza, A.K.G.; Leão, R.S.; et al. Genomic study of Acinetobacter baumannii strains co-harboring blaOXA-58 and blaNDM-1 in Brazil. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1439373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, J.; Shariff, M. Multilocus sequence typing of clinical and colonizing isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii and comparison with global isolates. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brek, T.M.; Muhajir, A.A.; Alkuwaity, K.K.; Haddad, M.A.; Alattas, E.M.; Eisa, Z.M.; Al-Thaqafy, M.S.; Albarraq, A.M.; Al-Zahrani, I.A. Genomic insights of predominant international high-risk clone ST2 Acinetobacter baumannii isolates in Saudi Arabia. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2025, 42, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidian, M.; Nigro, S.J. Emergence, molecular mechanisms, and global spread of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Microb. Genom. 2019, 5, e000306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Li, X.; Li, S.; Zhou, H.; Hu, L.; Xia, H.; Xie, L.; Xie, F. Nosocomial surveillance of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: a genomic epidemiological study. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e02207-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.R.; Lee, J.H.; Park, M.; Park, K.S.; Bae, I.K.; Kim, Y.B.; Cha, C.J.; Jeong, B.C.; Lee, S.H. Biology of Acinetobacter baumannii: pathogenesis, antibiotic resistance mechanisms, and prospective treatment options. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gutiérrez, K.; Vásquez-Mendoza, A.; Rodríguez, C. An outbreak of severe or lethal infections by a multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii ST126 strain carrying a plasmid with blaNDM-1 and blaOXA-58 carbapenemases. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2024, 110, 116428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khuntayaporn, P.; Kanathum, P.; Houngsaitong, J.; Montakantikul, P.; Thirapanmethee, K.; Chomnawang, M.T. Predominance of international clone 2 multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii clinical isolates in Thailand: a nationwide study. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2021, 20, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiradiputra, M.R.D.; Thirapanmethee, K.; Khuntayaporn, P.; Wanapaisan, P.; Chomnawang, M.T. Comparative genotypic characterization related to antibiotic resistance phenotypes of clinical carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii MTC1106 (ST2) and MTC0619 (ST25). BMC Genomics 2023, 24, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Aspas, A.; Guerrero-Sánchez, F.M.; García-Colchero, F.; Rodríguez-Roca, S.; Girón-González, J.-A. Differential characteristics of Acinetobacter baumannii colonization and infection. Infect. Drug Resist. 2018, 11, 861–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, É.L.; Morgado, S.M.; Freitas, F.; Oliveira, P.P.; Monteiro, P.M.; Lima, L.S.; Santos, B.P.; Sousa, M.A.R.; Assunção, A.O.; Mascarenhas, L.A.; et al. Persistence of a carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii (CRAB) international clone II (ST2/IC2) sub-lineage involved with outbreaks in two Brazilian clinical settings. J. Infect. Public Health 2023, 16, 1690–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Yuan, Y.; Tang, S.; Liu, C.; He, C. Clinical and microbiological features of a cohort of patients with Acinetobacter baumannii bloodstream infections. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2024, 43, 1721–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, S.; Osama, D.; Abdelsalam, N.A.; Shata, A.H.; Mouftah, S.F.; Elhadidy, M. Comparative genomics of Acinetobacter baumannii from Egyptian healthcare settings. BMC Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelenkov, A.; Akimkin, V.; Mikhaylova, Y. International high-risk clones of Acinetobacter baumannii. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castanheira, M.; Mendes, R.E.; Gales, A.C. Global epidemiology and mechanisms of resistance of the Acinetobacter baumannii–calcoaceticus complex. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 76 (Suppl. 2), S166–S178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo-Ramírez, S.; Graña-Miraglia, L. Inaccurate multilocus sequence typing of Acinetobacter baumannii. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaiarsa, S.; Batisti Biffignandi, G.; Esposito, E.P.; Castelli, M.; Jolley, K.A.; Brisse, S.; Sassera, D.; Zarrilli, R. Comparative analysis of the two Acinetobacter baumannii multilocus sequence typing (MLST) schemes. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, D.M.; Perez, F.; Conger, N.G.; Solomkin, J.S.; Adams, M.D.; Rather, P.N.; Bonomo, R.A. Acinetobacter baumannii-associated skin and soft tissue infections: recognizing a broadening spectrum of disease. Surg. Infect. 2010, 11, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chukamnerd, A.; Singkhamanan, K.; Chongsuvivatwong, V.; Palittapongarnpim, P.; Doi, Y.; Pomwised, R.; Sakunrang, C.; Jeenkeawpiam, K.; Yingkajorn, M.; Chusri, S.; et al. Whole-genome analysis of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii from clinical isolates in Southern Thailand. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwabor, L.C.; Chukamnerd, A.; Nwabor, O.F.; Surachat, K.; Pomwised, R.; Jeenkeawpiam, K.; Chusri, S. Genotypic and phenotypic mechanisms underlying antimicrobial resistance and rifampicin-based synergy against carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Heliyon 2024, 10, e27326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bankevich, A.; Nurk, S.; Antipov, D.; Gurevich, A.A.; Dvorkin, M.; Kulikov, A.S.; Lesin, V.M.; Nikolenko, S.I.; Pham, S.; Prjibelski, A.D.; et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing J. Comput. Biol. 2012, 19, 455–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurevich, A.; Saveliev, V.; Vyahhi, N.; Tesler, G. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 2013, 29, 1072–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seppey, M.; Manni, M.; Zdobnov, E.M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019, 1962, 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, C.; Rodriguez-R, L.M.; Phillippy, A.M.; Konstantinidis, K.T.; Aluru, S. High-throughput ANI analysis of 90K prokaryotic genomes reveals clear species boundaries. Nat. Comm. 2018, 9, 5114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2024, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bharat, A.; Petkau, A.; Avery, B.P.; Chen, J.C.; Folster, J.P.; Carson, C.A.; Kearney, A.; Nadon, C.; Mabon, P.; Thiessen, J.; et al. Correlation between phenotypic and in silico detection of antimicrobial resistance in Salmonella enterica in Canada using StarAMR. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nascimento, M.; Sousa, A.; Ramirez, M.; Francisco, A.P.; Carriço, J.A.; Vaz, C. PHYLOViZ 2.0: scalable data integration and visualization for phylogenetic inference. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 128–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, A.J.; Cummins, C.A.; Hunt, M.; Wong, V.K.; Reuter, S.; Holden, M.T.; Fookes, M.; Falush, D.; Keane, J.A.; Parkhill, J. Roary: rapid large-scale prokaryote pan-genome analysis. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 3691–3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, A.J.; Taylor, B.; Delaney, A.J.; Soares, J.; Seemann, T.; Keane, J.A.; Harris, S.R. SNP-sites: rapid efficient extraction of SNPs from multi-FASTA alignments. Microb. Genom. 2016, 2, e000056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, M.N.; Dehal, P.S.; Arkin, A.P. FastTree: computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2009, 26, 1641–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v5: an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W293–W296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Patients (N = 294) |

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age, Median [IQR] (years) | 52 [34,66] |

| Male | 172 (58.50%) |

| Female | 122 (41.50%) |

| Underlying diseases | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 131 (44.56%) |

| Hypertension | 98 (33.33%) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 75 (25.51%) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 52 (17.69%) |

| Coronary artery disease | 56 (19.05%) |

| Pulmonary disease | 38 (12.93%) |

| CCI score, Median [IQR] | 7 [5,8] |

| Prior antibiotic use within 3 months | |

| Ceftriaxone | 174 (59.18%) |

| Ceftazidime | 38 (12.93%) |

| Imipenem | 140 (47.62%) |

| Meropenem | 219 (74.49%) |

| Ertapenem | 32 (10.88%) |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | 164 (55.78%) |

| Aminoglycosides (amikacin or gentamycin) | 32 (10.88%) |

| Fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin or ciprofloxacin) | 98 (33.33%) |

| Others: azithromycin, colistin, tigecycline, cefoperazone/sulbactam, or antifungal agents | 59 (20.07%) |

| Clinical diagnosis | |

| Infection | |

| Bloodstream infection | 25 (8.50%) |

| Bloodstream infection and urinary tract infection | 5 (1.70%) |

| Peritonitis | 6 (2.04%) |

| Pleural effusion | 5 (1.70%) |

| Pneumonia | 122 (41.50%) |

| Skin/soft tissue infection | 19 (6.46%) |

| Urinary tract infection | 24 (8.16%) |

| Colonization | 88 (29.93%) |

| APACHE II score, Median [IQR] | 16 [12,16] |

| Length of hospital stay, Median [IQR] | 12 [9,19] |

| Antimicrobial Agents | Interpretation | Hospitals, n (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA (n = 7) | PSU (n = 99) | PT (n = 53) | SK (n = 43) | ST (n = 10) | TR (n = 78) | YL (n = 4) | ||

| IPM | Susceptible | 0 (0) | 6 (6.06) | 2 (3.77) | 0 (0) | 1 (10) | 1 (1.28) | 0 (0) |

| Resistant | 7 (100) | 93 (93.94) | 51 (96.23) | 43 (100) | 9 (90) | 77 (98.72) | 4 (100) | |

| MEM | Susceptible | 0 (0) | 4 (4.04) | 3 (5.66) | 1 (2.33) | 1 (10) | 2 (2.56) | 0 (0) |

| Resistant | 7 (100) | 95 (95.96) | 50 (94.34) | 42 (97.67) | 9 (90) | 76 (97.44) | 4 (100) | |

| CAZ | Susceptible | 0 (0) | 4 (4.04) | 1 (1.89) | 1 (2.33) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.28) | 0 (0) |

| Resistant | 7 (100) | 95 (95.96) | 52 (98.11) | 42 (97.67) | 10 (100) | 77 (98.72) | 4 (100) | |

| CEP/SUL | Susceptible | 0 (0) | 13 (13.13) | 8 (15.09) | 5 (11.63) | 1 (10) | 6 (7.69) | 1 (25) |

| Resistant | 7 (100) | 86 (86.87) | 45 (84.91) | 38 (88.37) | 9 (90) | 72 (92.31) | 3 (75) | |

| AMK | Susceptible | 0 (0) | 4 (4.04) | 2 (3.77) | 1 (2.33) | 1 (10) | 1 (1.28) | 0 (0) |

| Resistant | 7 (100) | 95 (95.96) | 51 (96.23) | 42 (97.67) | 9 (90) | 77 (98.72) | 4 (100) | |

| GEN | Susceptible | 0 (0) | 4 (4.04) | 2 (3.77) | 1 (2.33) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.56) | 0 (0) |

| Resistant | 7 (100) | 95 (95.96) | 51 (96.23) | 42 (97.67) | 10 (100) | 76 (97.44) | 4 (100) | |

| CIP | Susceptible | 0 (0) | 3 (3.03) | 1 (1.89) | 1 (2.33) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Resistant | 7 (100) | 96 (96.97) | 52 (98.11) | 42 (97.67) | 9 (90) | 78 (100) | 4 (100) | |

| LVX | Susceptible | 0 (0) | 3 (3.03) | 1 (1.89) | 1 (2.33) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) |

| Resistant | 7 (100) | 96 (96.97) | 52 (98.11) | 42 (97.67) | 10 (100) | 78 (100) | 3 (75) | |

| CST | Susceptible | 7 (100) | 91 (91.92) | 50 (94.34) | 40 (93.02) | 10 (100) | 76 (97.44) | 4 (100) |

| Resistant | 0 (0) | 8 (8.08) | 3 (5.66) | 3 (6.98) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.56) | 0 (0) | |

| TMP/SMX | Susceptible | 0 (0) | 9 (9.09) | 8 (15.09) | 9 (20.93) | 0 (0) | 9 (11.54) | 1 (25) |

| Resistant | 7 (100) | 90 (90.91) | 45 (84.91) | 34 (79.07) | 10 (100) | 69 (88.46) | 3 (75) | |

| TIG | Susceptible | 7 (100) | 81 (81.82) | 48 (90.57) | 41 (95.35) | 10 (100) | 75 (96.15) | 4 (100) |

| Resistant | 0 (0) | 18 (18.18) | 5 (9.43) | 2 (4.65) | 0 (0) | 3 (3.85) | 0 (0) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).