Submitted:

19 January 2026

Posted:

21 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagent

2.2. Macrophage Culture, Differentiation and Polarization

2.3. Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) and Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

2.4. Western Blotting

2.5. UGT Activity Assay Using Fluorescence-Based Detection System

2.6. UGT Activity Assay Using LC/MS-MS

2.7. ELISA Assay

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

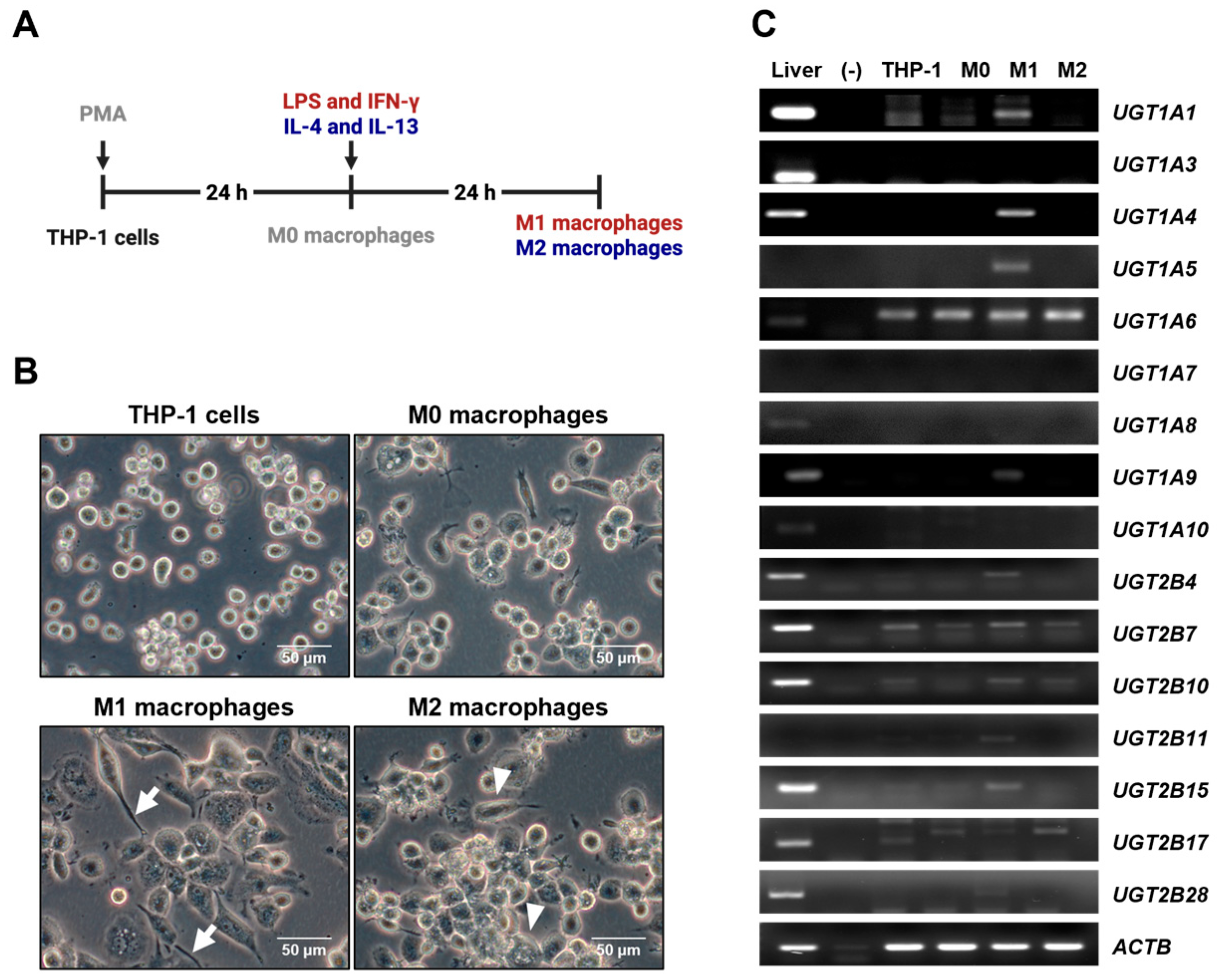

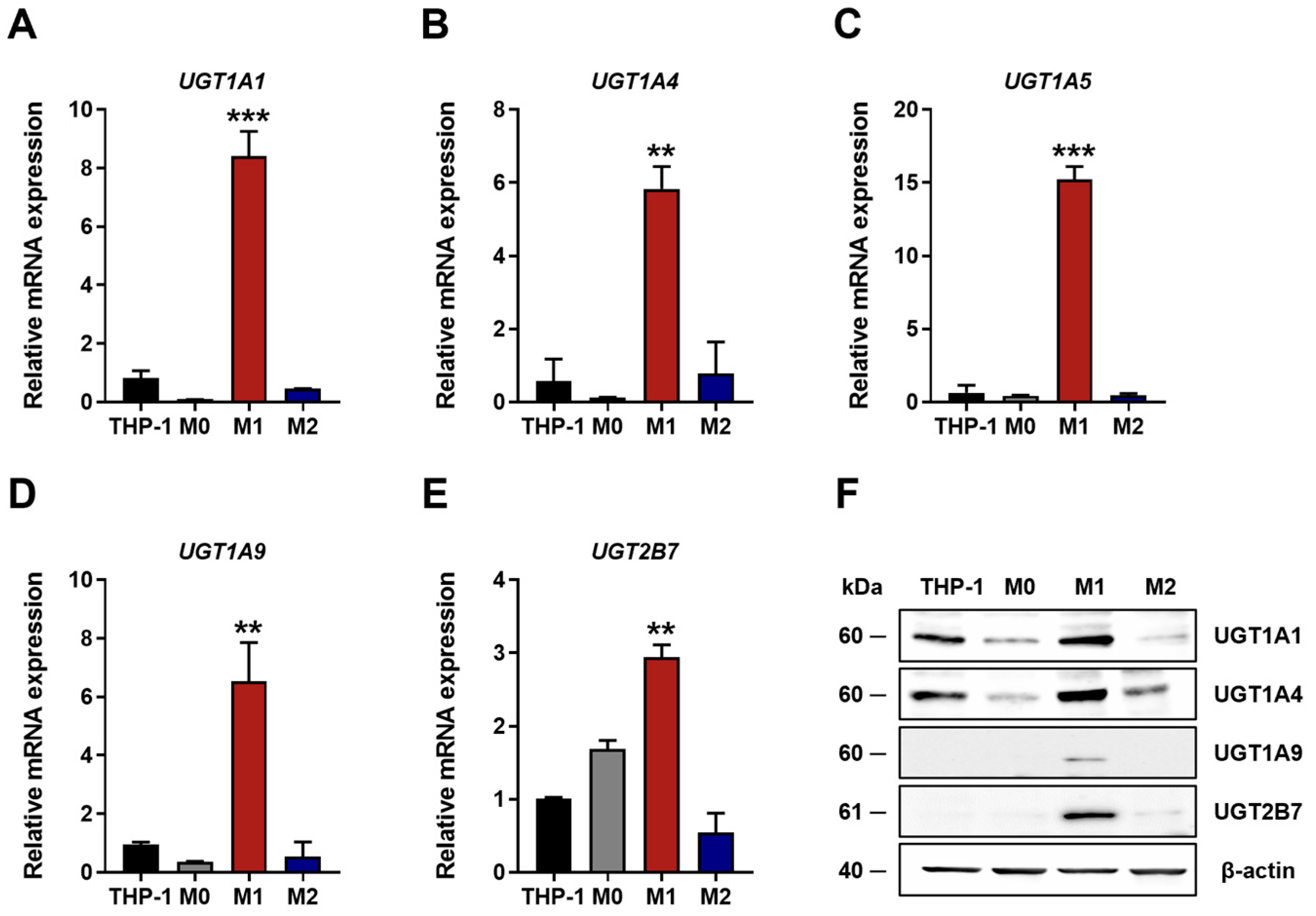

3.1. UGT Expression Profiles

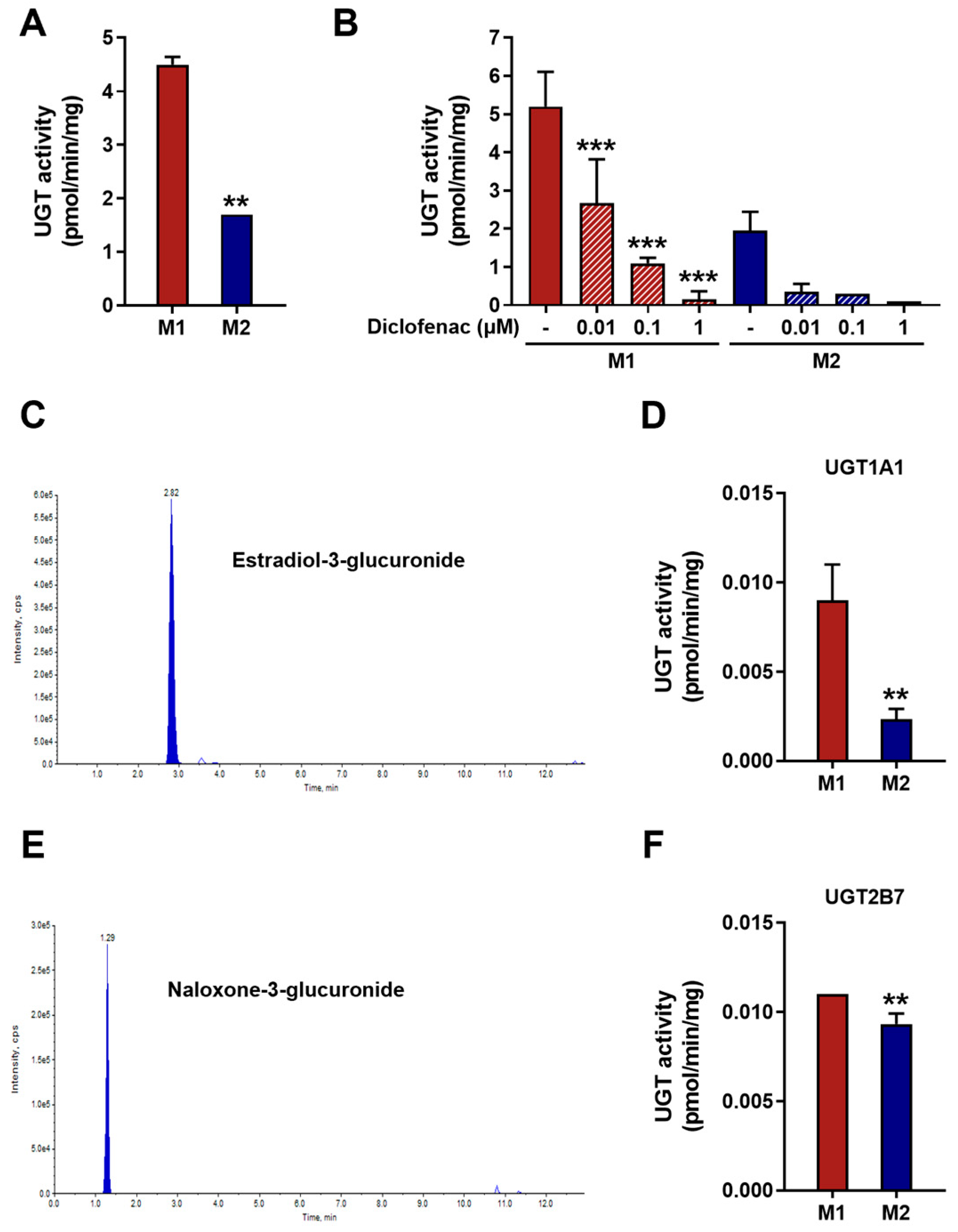

3.2. UGT Enzymatic Activity in M1 and M2 Macrophages

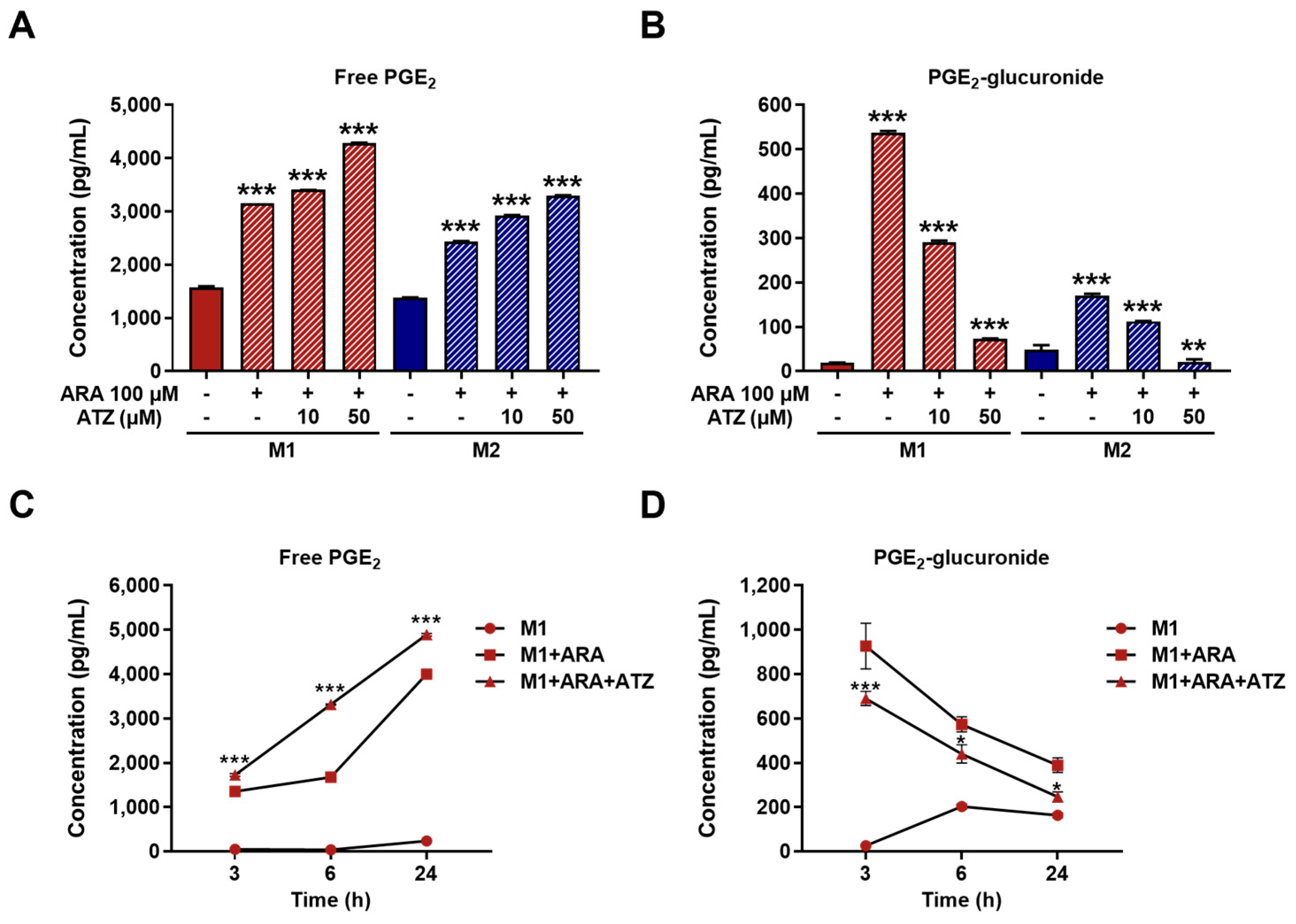

3.3. Impact of UGT-Mediated PGE2 Glucuronidation in M1 Macrophages

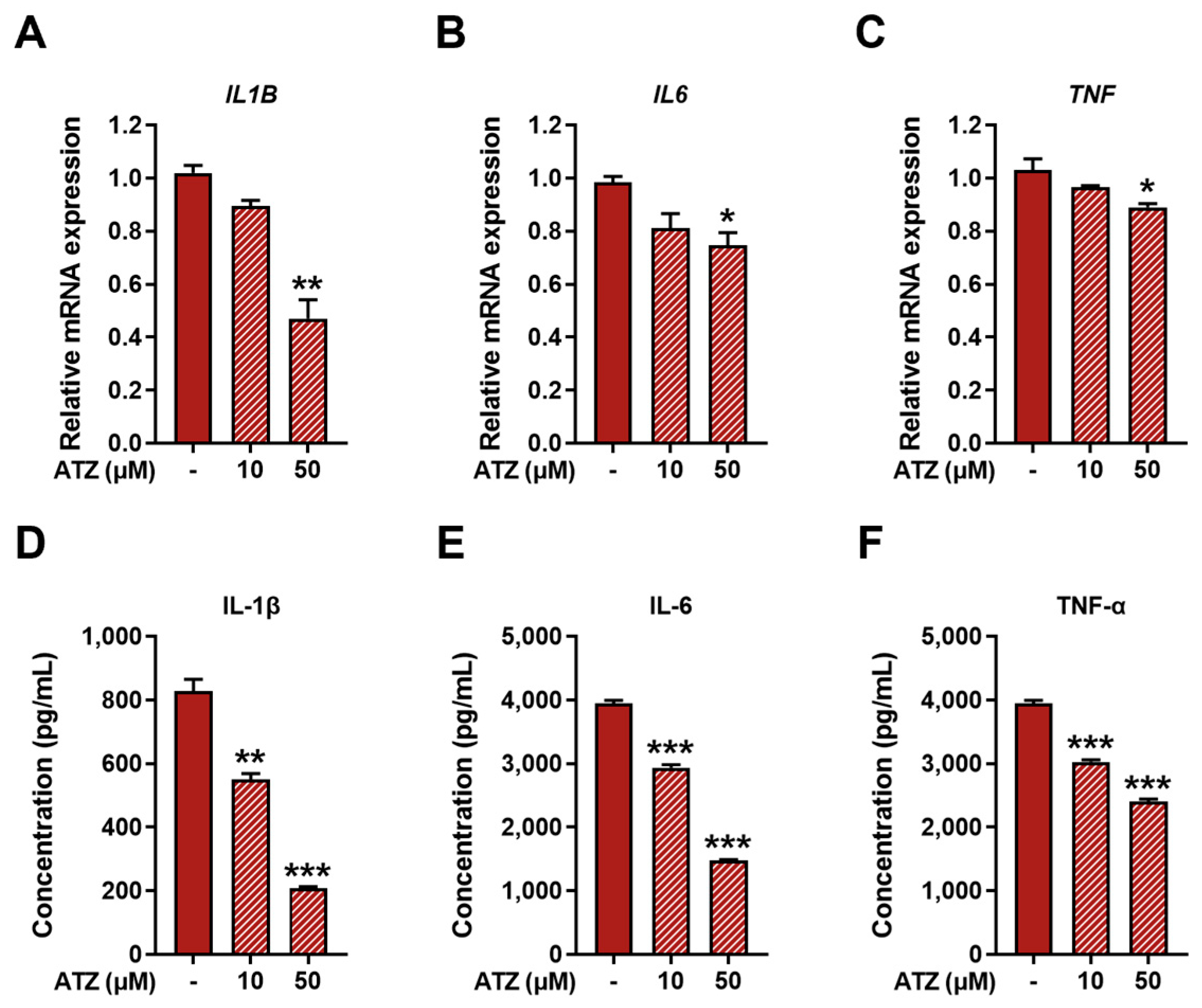

3.4. Effect of UGT Inhibition on Pro-Inflammatory Markers in M1 Macrophages

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ARA | Arachidonic acid |

| ATZ | Atazanavir |

| IFN-γ | Interferon gamma |

| IL | Interleukin |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| NSAID | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug |

| PGE2 | Prostaglandin E2 |

| PMA | Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| UDPGA | UDP-glucuronic acid |

| UGT | UDP-glucuronosyltransferase |

References

- Wynn, T.A.; Chawla, A.; Pollard, J.W. Macrophage Biology in Development, Homeostasis and Disease. Nature 2013, 496, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murray, P.J.; Wynn, T.A. Protective and Pathogenic Functions of Macrophage Subsets. Nat Rev Immunol 2011, 11, 723–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Italiani, P.; Boraschi, D. From Monocytes to M1/M2 Macrophages: Phenotypical vs. Functional Differentiation. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mantovani, A.; Biswas, S.K.; Galdiero, M.R.; Sica, A.; Locati, M. Macrophage Plasticity and Polarization in Tissue Repair and Remodelling. The Journal of Pathology 2013, 229, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A.; Marchesi, F.; Malesci, A.; Laghi, L.; Allavena, P. Tumour-Associated Macrophages as Treatment Targets in Oncology. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2017, 14, 399–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tukey, R.H.; Strassburg, C.P. Human UDP-Glucuronosyltransferases: Metabolism, Expression, and Disease. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2000, 40, 581–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Sun, R.; Liao, X.; Aa, J.; Wang, G. UDP-Glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs) and Their Related Metabolic Cross-Talk with Internal Homeostasis: A Systematic Review of UGT Isoforms for Precision Medicine. Pharmacological Research 2017, 121, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meech, R.; Hu, D.G.; McKinnon, R.A.; Mubarokah, S.N.; Haines, A.Z.; Nair, P.C.; Rowland, A.; Mackenzie, P.I. The UDP-Glycosyltransferase (UGT) Superfamily: New Members, New Functions, and Novel Paradigms. Physiological Reviews 2019, 99, 1153–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tochigi, Y.; Yamashiki, N.; Ohgiya, S.; Ganaha, S.; Yokota, H. ISOFORM-SPECIFIC EXPRESSION AND INDUCTION OF UDP-GLUCURONOSYLTRANSFERASE IN IMMUNOACTIVATED PERITONEAL MACROPHAGES OF THE RAT. Drug Metabolism and Disposition 2005, 33, 1391–1398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricciotti, E.; FitzGerald, G.A. Prostaglandins and Inflammation. ATVB 2011, 31, 986–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinski, P. Regulation of Immune Responses by Prostaglandin E2. The Journal of Immunology 2012, 188, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedi, H.; Norbert, G. Inhibition of IL-6, TNF-α, and Cyclooxygenase-2 Protein Expression by Prostaglandin E2-Induced IL-10 in Bone Marrow-Derived Dendritic Cells. Cellular Immunology 2004, 228, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gunaydin, C.; Bilge, S.S. Effects of Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs at the Molecular Level. EAJM 2019, 50, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allain, E.P.; Rouleau, M.; Le, T.; Vanura, K.; Villeneuve, L.; Caron, P.; Turcotte, V.; Lévesque, E.; Guillemette, C. Inactivation of Prostaglandin E2 as a Mechanism for UGT2B17-Mediated Adverse Effects in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.Y.; Ahn, S.; Cho, Y.-S.; Seo, S.-K.; Kim, D.H.; Shin, J.-G.; Lee, S.-J. CYP2C19 Contributes to THP-1-Cell-Derived M2 Macrophage Polarization by Producing 11,12- and 14,15-Epoxyeicosatrienoic Acid, Agonists of the PPARγ Receptor. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, J.A.; Ring, B.J.; Cantrell, V.E.; Campanale, K.; Jones, D.R.; Hall, S.D.; Wrighton, S.A. Differential Modulation of UDP-Glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 (UGT1A1)-Catalyzed Estradiol-3-Glucuronidation by the Addition of UGT1A1 Substrates and Other Compounds to Human Liver Microsomes. Drug Metabolism and Disposition 2002, 30, 1266–1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Marco, A.; D’Antoni, M.; Attaccalite, S.; Carotenuto, P.; Laufer, R. DETERMINATION OF DRUG GLUCURONIDATION AND UDP-GLUCURONOSYLTRANSFERASE SELECTIVITY USING A 96-WELL RADIOMETRIC ASSAY. Drug Metabolism and Disposition 2005, 33, 812–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, K.-A.; Kim, H.-J.; Jeong, E.S.; Abdalla, N.; Choi, C.-S.; Kim, D.-H.; Shin, J.-G. In Vitro Assay of Six UDP-Glucuronosyltransferase Isoforms in Human Liver Microsomes, Using Cocktails of Probe Substrates and Liquid Chromatography–Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Drug Metabolism and Disposition 2014, 42, 1803–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkhenany, H.A.; Linardi, R.L.; Ortved, K.F. Differential Modulation of Inflammatory Cytokines by Recombinant IL-10 in IL-1β and TNF-α ̶ Stimulated Equine Chondrocytes and Synoviocytes: Impact of Washing and Timing on Cytokine Responses. BMC Vet Res 2024, 20, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, W.; Shi, J.; Guo, Y. Midkine Promotes PDGF - BB -induced Proliferation, Migration, and Glycolysis of Airway Smooth Muscle Cells via the PI3K Akt Pathway. Physiological Reports 2025, 13, e70553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Huang, T.; Li, J.; Li, A.; Li, C.; Huang, X.; Li, D.; Wang, S.; Liang, M. Optimization of Differentiation and Transcriptomic Profile of THP-1 Cells into Macrophage by PMA. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0286056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orecchioni, M.; Ghosheh, Y.; Pramod, A.B.; Ley, K. Macrophage Polarization: Different Gene Signatures in M1(LPS+) vs. Classically and M2(LPS–) vs. Alternatively Activated Macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scott, T.E.; Lewis, C.V.; Zhu, M.; Wang, C.; Samuel, C.S.; Drummond, G.R.; Kemp-Harper, B.K. IL-4 and IL-13 Induce Equivalent Expression of Traditional M2 Markers and Modulation of Reactive Oxygen Species in Human Macrophages. Sci Rep 2023, 13, 19589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarrar, Y.B.; Kim, D.H.; Lee, S.-J.; Shin, J.-G. Inhibition of 20-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic Acid (20-HETE) Glucuronidation by Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs in Human Liver Microsomes and Recombinant UDP-Glucuronosyltransferase Enzymes. Prostaglandins, Leukotrienes and Essential Fatty Acids 2020, 153, 102055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Wu, L.; Chen, J.; Dong, L.; Chen, C.; Wen, Z.; Hu, J.; Fleming, I.; Wang, D.W. Metabolism Pathways of Arachidonic Acids: Mechanisms and Potential Therapeutic Targets. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2021, 6, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Mey, D.; Gerisch, M.; Jungmann, N.A.; Kaiser, A.; Yoshikawa, K.; Schulz, S.; Radtke, M.; Lentini, S. Drug-drug Interaction of Atazanavir on UGT1A1-mediated Glucuronidation of Molidustat in Human. Basic Clin Pharma Tox 2021, 128, 511–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayama, K.; Garcı́a-Cardeña, G.; Sukhova, G.K.; Comander, J.; Gimbrone, M.A.; Libby, P. Prostaglandin E2 Suppresses Chemokine Production in Human Macrophages through the EP4 Receptor. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2002, 277, 44147–44154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Liang, M.; Wang, L.; Bei, W.; Rong, X.; Xu, J.; Guo, J. Role of Prostaglandin E2 in Macrophage Polarization: Insights into Atherosclerosis. Biochemical Pharmacology 2023, 207, 115357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Saeed, A.F.U.H.; Liu, Q.; Jiang, Q.; Xu, H.; Xiao, G.G.; Rao, L.; Duo, Y. Macrophages in Immunoregulation and Therapeutics. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2023, 8, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, T.A.; Sherman, M.; Kalman, D.; Morgan, E.T. EXPRESSION OF UDP-GLUCURONOSYLTRANSFERASE ISOFORM mRNAS DURING INFLAMMATION AND INFECTION IN MOUSE LIVER AND KIDNEY. Drug Metabolism and Disposition 2006, 34, 351–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, H.; Zhou, L.; Yuen, J.; Forman, H.J. Temporal Changes in Glutathione Biosynthesis during the Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Inflammatory Response of THP-1 Macrophages. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2017, 113, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diotallevi, M.; Checconi, P.; Palamara, A.T.; Celestino, I.; Coppo, L.; Holmgren, A.; Abbas, K.; Peyrot, F.; Mengozzi, M.; Ghezzi, P. Glutathione Fine-Tunes the Innate Immune Response toward Antiviral Pathways in a Macrophage Cell Line Independently of Its Antioxidant Properties. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, S.; Rius-Pérez, S. Macrophage Polarization and Reprogramming in Acute Inflammation: A Redox Perspective. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, M.M.-Y.; Moore, A.R. Resolution of Inflammation in Murine Autoimmune Arthritis Is Disrupted by Cyclooxygenase-2 Inhibition and Restored by Prostaglandin E2-Mediated Lipoxin A4 Production. The Journal of Immunology 2010, 184, 6418–6426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basil, M.C.; Levy, B.D. Specialized Pro-Resolving Mediators: Endogenous Regulators of Infection and Inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 2016, 16, 51–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soars, M.G.; Petullo, D.M.; Eckstein, J.A.; Kasper, S.C.; Wrighton, S.A. AN ASSESSMENT OF UDP-GLUCURONOSYLTRANSFERASE INDUCTION USING PRIMARY HUMAN HEPATOCYTES. Drug Metabolism and Disposition 2004, 32, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).