Submitted:

19 January 2026

Posted:

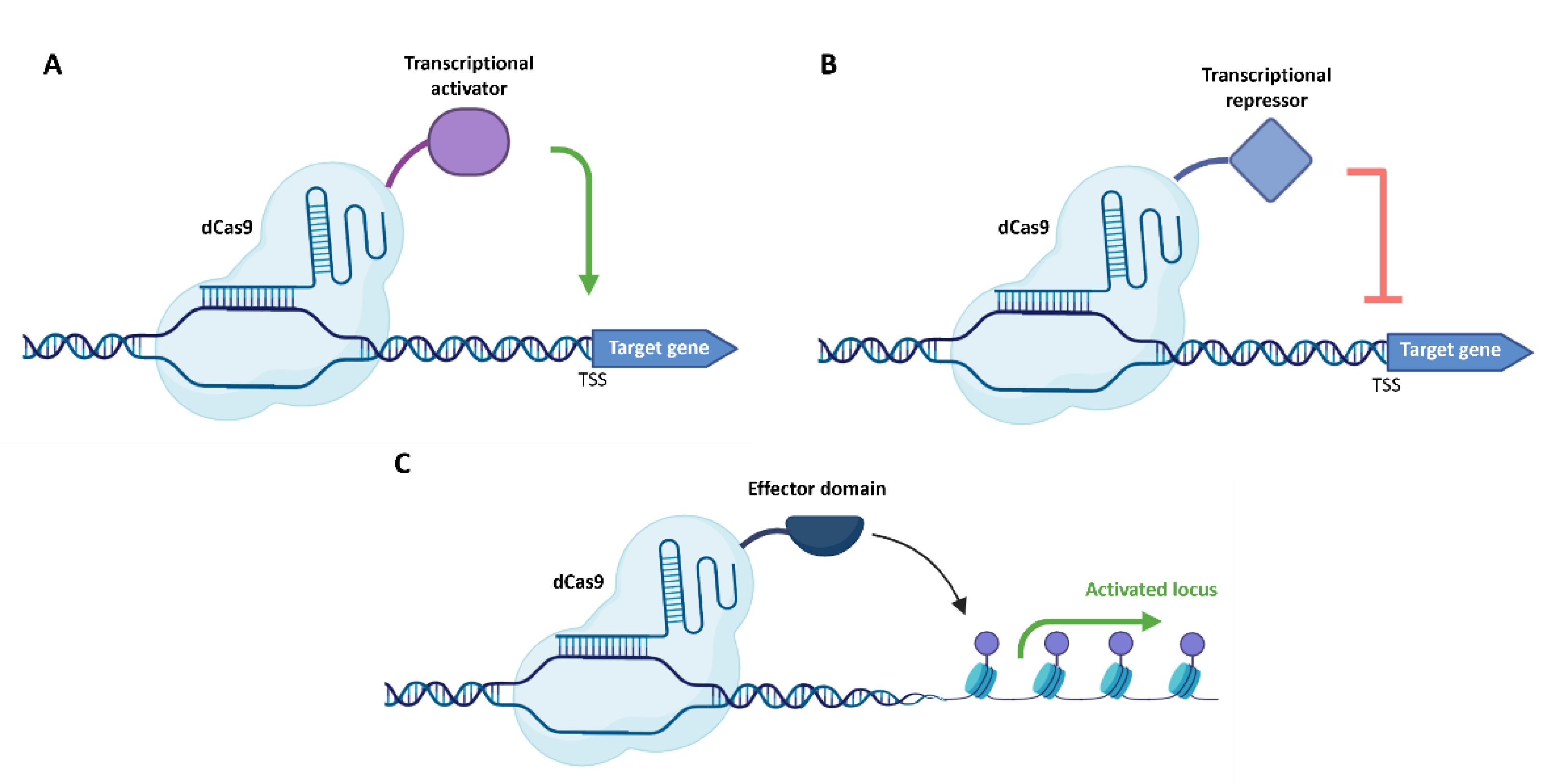

21 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

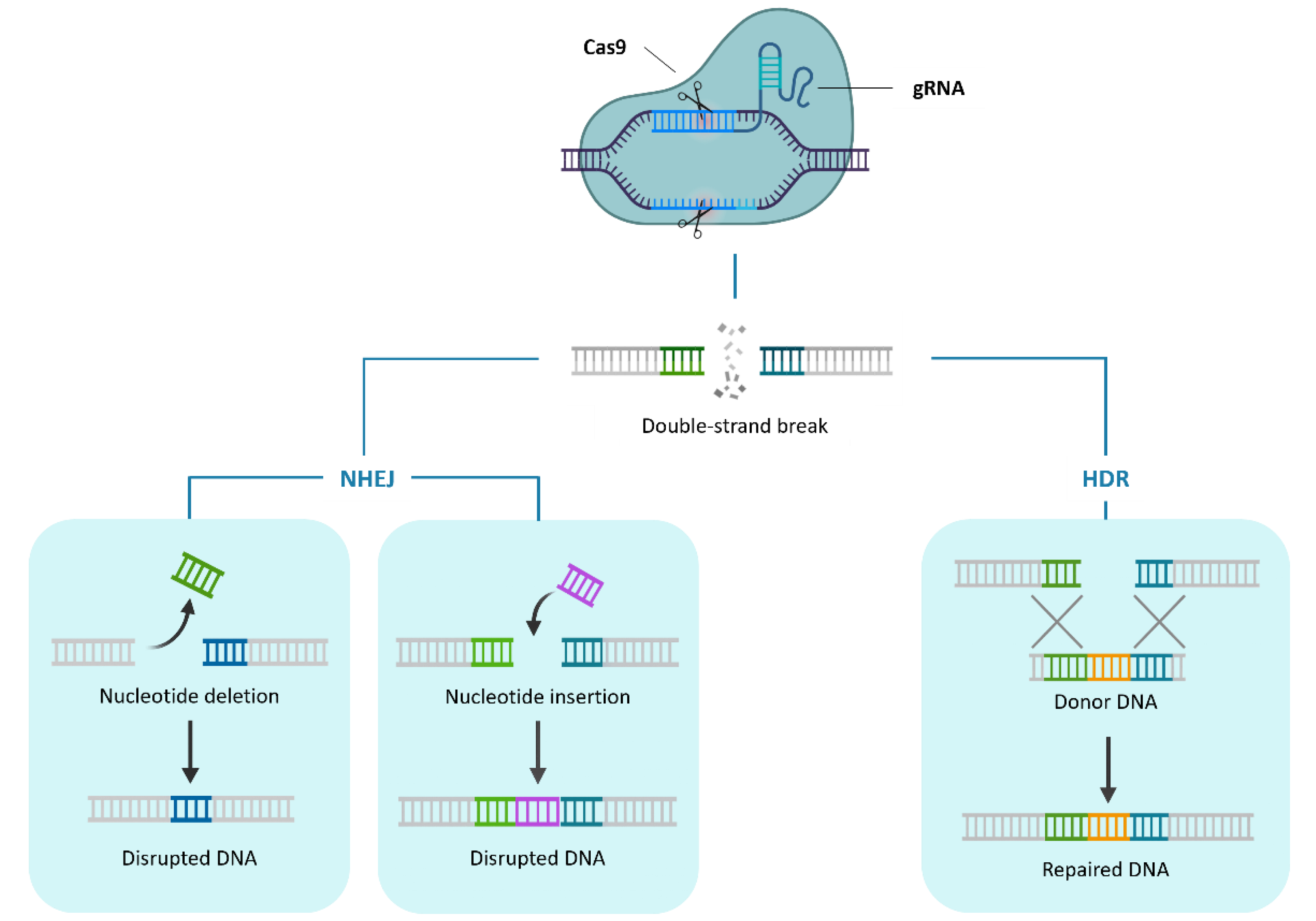

1. CRISPR/Cas9 Mediated Genome Editing

1.1. CRISPR/Cas9 for Gene Knockout

1.2. CRISPR/Cas9 for Gene Knock-In and Allele Swapping

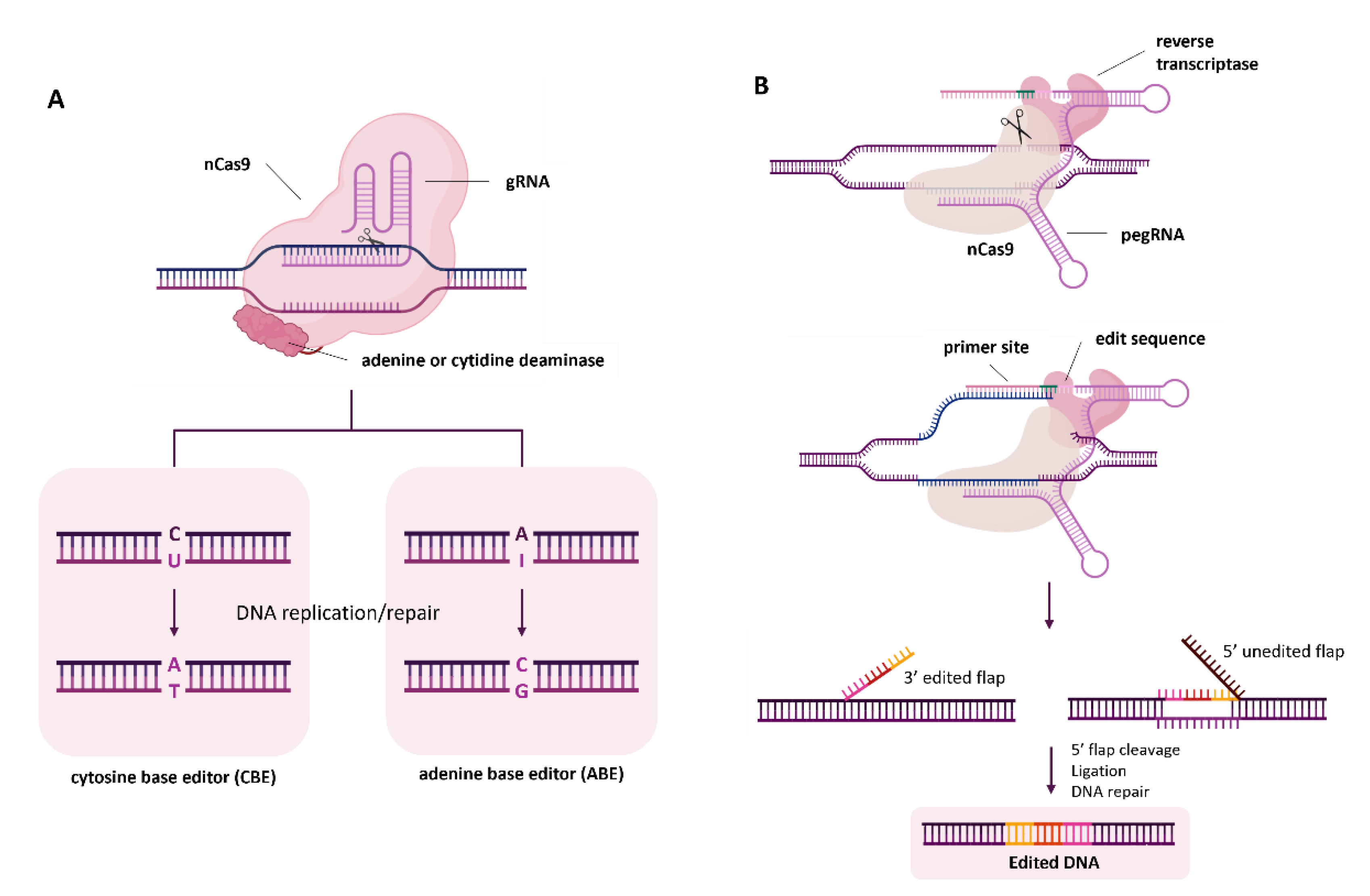

2. Base Editing and Prime Editing

3. CRISPR/Cas-Mediated Transcription Activation and Inhibition

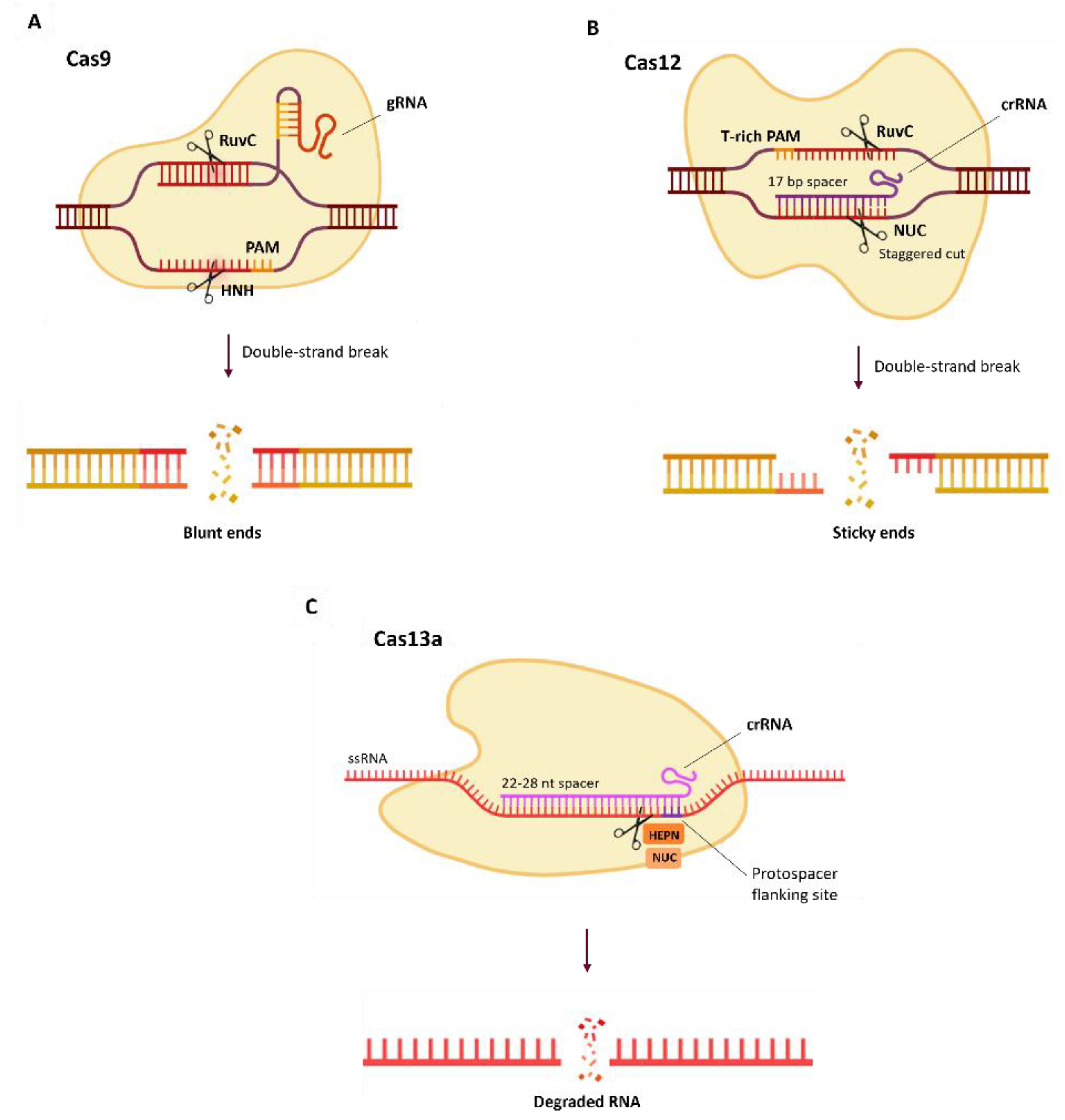

4. Alternative Cas Proteins

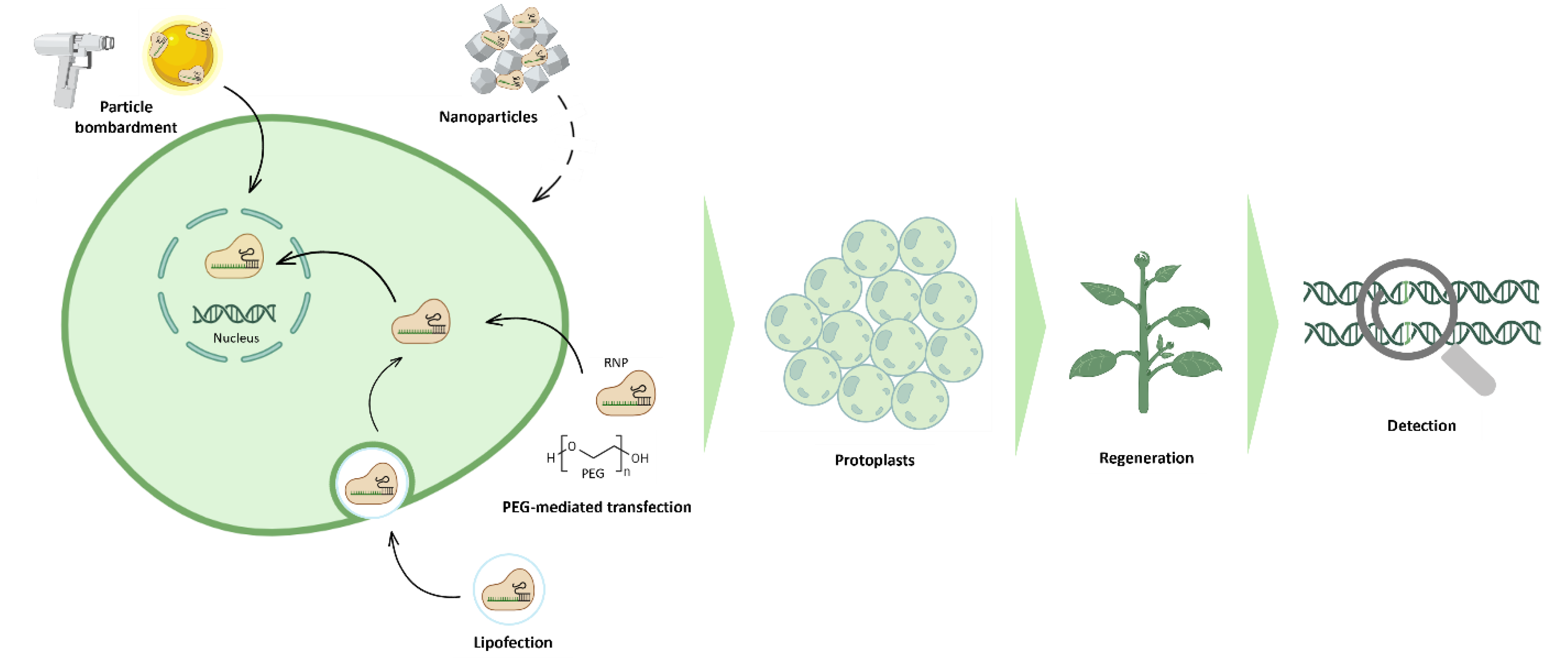

5. RNPs Mediated Genome Editing in Protoplasts

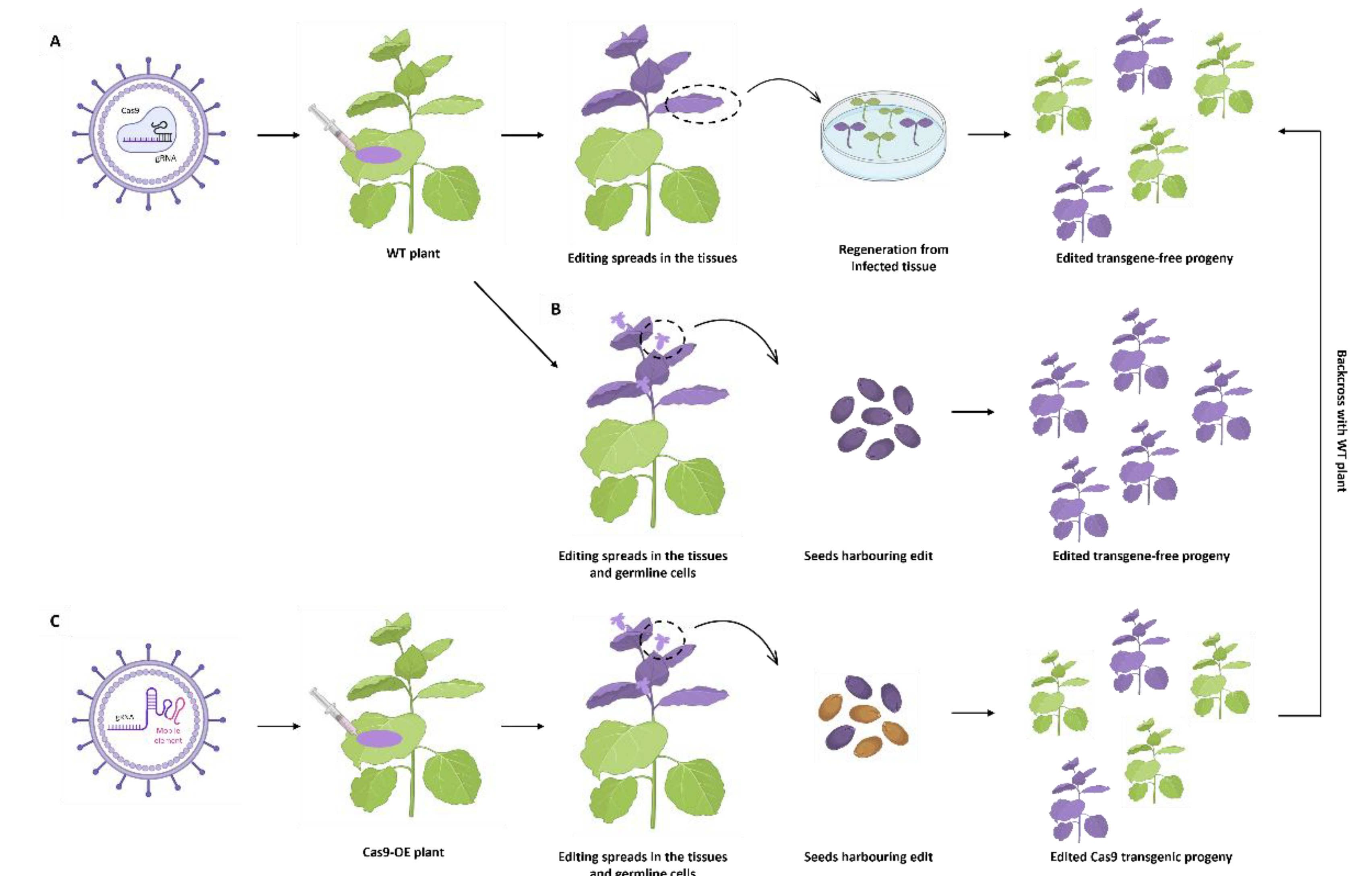

6. Virus Induced Gene Editing

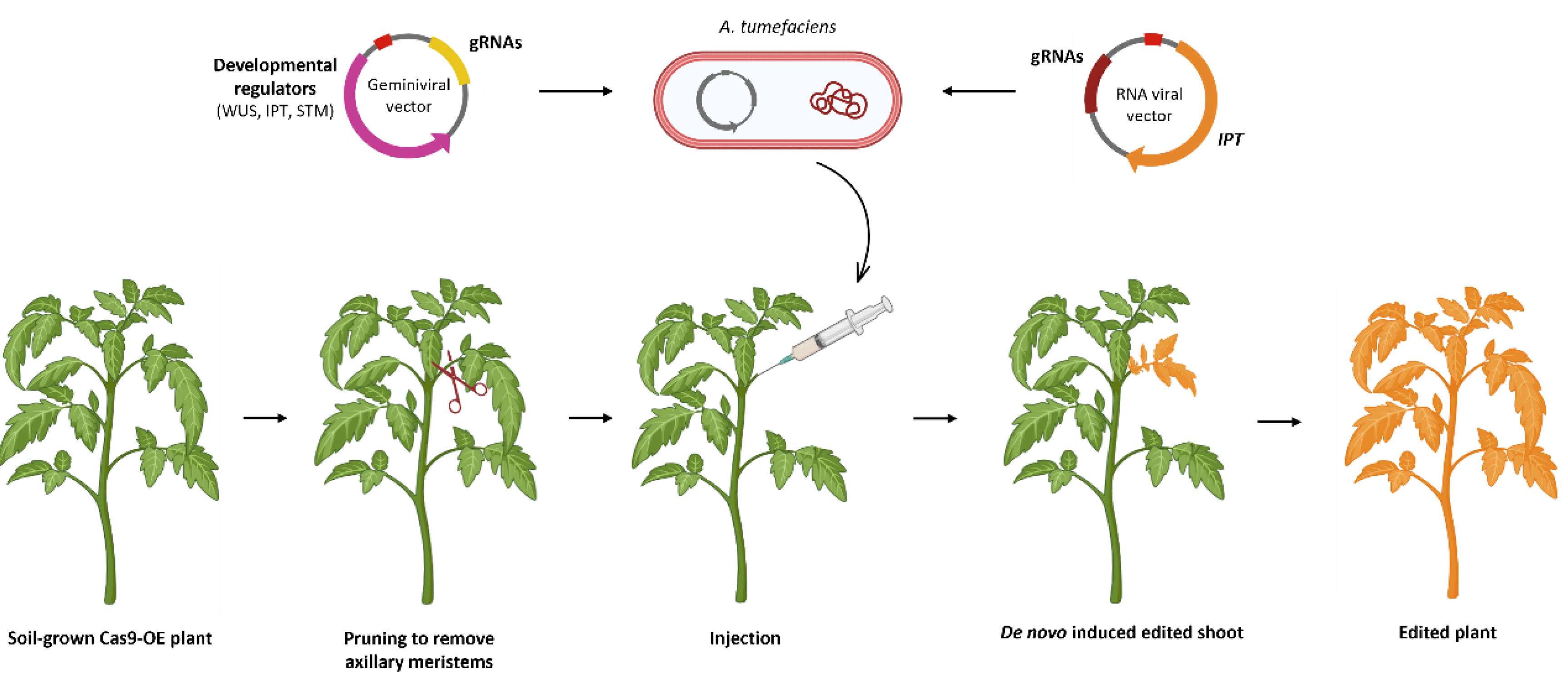

7. De Novo Induction of Meristems

8. Research and Field Trials for CRISPRed Plants in Europe

9. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CRISPR | Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| RNA | Ribonucleic acid |

| Cas | CRISPR associated |

| PAM | Protospacer adjacent motif |

| GMO | Genetically modified organism |

References

- Chen, K.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, H.; Gao, C. ‘CRISPR/Cas Genome Editing and Precision Plant Breeding in Agriculture’. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2019, vol. 70(no. 1), 667–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaq. ‘Modern Trends in Plant Genome Editing: An Inclusive Review of the CRISPR/Cas9 Toolbox’. IJMS 2019, vol. 20(no. 16), 4045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doudna, J. A.; Charpentier, E. ‘The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9’. Science 2014, vol. 346(no. 6213), 1258096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortesi, L.; Fischer, R. ‘The CRISPR/Cas9 system for plant genome editing and beyond’. Biotechnology Advances 2015, vol. 33(no. 1), 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.-F. ‘Multiplex and homologous recombination–mediated genome editing in Arabidopsis and Nicotiana benthamiana using guide RNA and Cas9’. Nat Biotechnol 2013, vol. 31(no. 8), 688–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaganathan, D.; Ramasamy, K.; Sellamuthu, G.; Jayabalan, S.; Venkataraman, G. ‘CRISPR for Crop Improvement: An Update Review’. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, vol. 9, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, C.; Nekrasov, V.; Lippman, Z. B.; Van Eck, J. ‘Efficient Gene Editing in Tomato in the First Generation Using the Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats/CRISPR-Associated9 System’. PLANT PHYSIOLOGY 2014, vol. 166(no. 3), 1292–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, N. M.; Atkins, P. A.; Voytas, D. F.; Douches, D. S. ‘Generation and Inheritance of Targeted Mutations in Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Using the CRISPR/Cas System’. PLoS ONE 2015, vol. 10(no. 12), e0144591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R. ‘CRISPR/Cas9-Based Knock-Out of the PMR4 Gene Reduces Susceptibility to Late Blight in Two Tomato Cultivars’. IJMS 2022, vol. 23(no. 23), 14542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maioli. ‘Knock-out of SlDMR6-1 in tomato promotes a drought-avoidance strategy and increases tolerance to Late Blight’. Plant Stress 2024, 100541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekrasov, V.; Wang, C.; Win, J.; Lanz, C.; Weigel, D.; Kamoun, S. ‘Rapid generation of a transgene-free powdery mildew resistant tomato by genome deletion’. Sci Rep 2017, vol. 7(no. 1), 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santillán Martínez, M. I. ‘CRISPR/Cas9-targeted mutagenesis of the tomato susceptibility gene PMR4 for resistance against powdery mildew’. BMC Plant Biol 2020, vol. 20(no. 1), 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomazella, D. P. de T. ‘Loss of function of a DMR6 ortholog in tomato confers broad-spectrum disease resistance’. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, vol. 118(no. 27), e2026152118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R. ‘Less is more: CRISPR/Cas9-based mutations in DND1 gene enhance tomato resistance to powdery mildew with low fitness costs’. BMC Plant Biol 2024, vol. 24(no. 1), 763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, W. CRISPR /Cas9-guided editing of a novel susceptibility gene in potato improves Phytophthora resistance without growth penalty’. Plant Biotechnology Journal 2024, vol. 22(no. 1), 4–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karlsson, M. ‘CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing of potato StDMR6-1 results in plants less affected by different stress conditions’. Horticulture Research 2024, p. uhae130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kieu, N. P.; Lenman, M.; Wang, E. S.; Petersen, B. L.; Andreasson, E. ‘Mutations introduced in susceptibility genes through CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing confer increased late blight resistance in potatoes’. Sci Rep 2021, vol. 11(no. 1), 4487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K. ‘Silencing of six susceptibility genes results in potato late blight resistance’. Transgenic Res 2016, vol. 25(no. 5), 731–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K. ‘Silencing susceptibility genes in potato hinders primary infection with Phytophthora infestans at different stages’. Horticulture Research 2022, vol. 9, uhab058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, W. ‘Potato DMP2 positively regulates plant immunity by modulating endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis’. JIPB 2025, vol. 67(no. 6), 1568–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaq, H. A.; Ijaz, S.; Haq, I. U.; Khan, I. A. ‘Functional inhibition of the StERF3 gene by dual targeting through CRISPR/Cas9 enhances resistance to the late blight disease in Solanum tuberosum L.’. Mol Biol Rep 2022, vol. 49(no. 12), 11675–11684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramasamy, M. ‘Genome editing of NPR3 confers potato resistance to Candidatus Liberibacter spp.’. Plant Biotechnology Journal 2024, vol. 22(no. 9), 2635–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroiwa, K.; Thenault, C.; Nogué, F.; Perrot, L.; Mazier, M.; Gallois, J.-L. ‘CRISPR-based knock-out of eIF4E2 in a cherry tomato background successfully recapitulates resistance to pepper veinal mottle virus’. Plant Science 2022, vol. 316, 111160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramanik, D. ‘CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Generation of Pathogen-Resistant Tomato against Tomato Yellow Leaf Curl Virus and Powdery Mildew’. IJMS 2021, vol. 22(no. 4), 1878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tashkandi, M.; Ali, Z.; Aljedaani, F.; Shami, A.; Mahfouz, M. M. Engineering resistance against Tomato yellow leaf curl virus via the CRISPR/Cas9 system in tomato’. Plant Signaling & Behavior 2018, vol. 13(no. 10), e1525996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucioli; Tavazza, R.; Baima, S.; Fatyol, K.; Burgyan, J.; Tavazza, M. ‘CRISPR-Cas9 Targeting of the eIF4E1 Gene Extends the Potato Virus Y Resistance Spectrum of the Solanum tuberosum L. cv. Desirée’. Front. Microbiol. 2022, vol. 13, 873930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noureen; Khan, M. Z.; Amin, I.; Zainab, T.; Mansoor, S. ‘CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Targeting of Susceptibility Factor eIF4E-Enhanced Resistance Against Potato Virus Y’. Front. Genet. 2022, vol. 13, 922019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z. ‘The protein kinase CPK28 phosphorylates ascorbate peroxidase and enhances thermotolerance in tomato’. Plant Physiology 2021, vol. 186(no. 2), 1302–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakeshpour, T. ‘CGFS -type glutaredoxin mutations reduce tolerance to multiple abiotic stresses in tomato’. Physiologia Plantarum 2021, vol. 173(no. 3), 1263–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R. ‘CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated SlNPR1 mutagenesis reduces tomato plant drought tolerance’. BMC Plant Biol 2019, vol. 19(no. 1), 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Yuan, Y.; Feng, B.; Deng, W. ‘CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene-editing technology in fruit quality improvement’. Food Quality and Safety 2020, vol. 4(no. 4), 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X. ‘Biofortification of tomatoes with beta-carotene through targeted gene editing’. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2025, vol. 327, 147396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q. ‘CRISPR/cas9 Allows for the Quick Improvement of Tomato Firmness Breeding’. CIMB 2024, vol. 47(no. 1), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, J. H. ‘Development of a Genome-Edited Tomato With High Ascorbate Content During Later Stage of Fruit Ripening Through Mutation of SlAPX4’. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, vol. 13, 836916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J. ‘Biofortified tomatoes provide a new route to vitamin D sufficiency’. Nat. Plants 2022, vol. 8(no. 6), 611–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrero, M. ‘Enhancing tolerance to Phytophthora spp. in eggplant through DMR6–1 CRISPR/Cas9 knockout’. Plant Stress 2024, vol. 14, 100691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maioli. Simultaneous CRISPR/Cas9 Editing of Three PPO Genes Reduces Fruit Flesh Browning in Solanum melongena L.’, Front. Plant Sci. 2020, vol. 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodackattumannil, P. ‘Hidden pleiotropy of agronomic traits uncovered by CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis of the tyrosinase CuA-binding domain of the polyphenol oxidase 2 of eggplant’. Plant Cell Rep 2023, vol. 42(no. 4), 825–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M.; Turesson, H.; Nicolia, A.; Fält, A.-S.; Samuelsson, M.; Hofvander, P. ‘Efficient targeted multiallelic mutagenesis in tetraploid potato (Solanum tuberosum) by transient CRISPR-Cas9 expression in protoplasts’. Plant Cell Rep 2017, vol. 36(no. 1), 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, M. N. ‘Reduced Enzymatic Browning in Potato Tubers by Specific Editing of a Polyphenol Oxidase Gene via Ribonucleoprotein Complexes Delivery of the CRISPR/Cas9 System’. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, vol. 10, 1649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Ye, G.; Zhou, Y.; Pu, X.; Su, W.; Wang, J. Editing sterol side chain reductase 2 gene ( StSSR2 ) via CRISPR/Cas9 reduces the total steroidal glycoalkaloids in potato’. All Life 2021, vol. 14(no. 1), 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducreux, L. J. M. ‘Metabolic engineering of high carotenoid potato tubers containing enhanced levels of -carotene and lutein’. Journal of Experimental Botany 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayasu, M. ‘Generation of α-solanine-free hairy roots of potato by CRISPR/Cas9 mediated genome editing of the St16DOX gene’. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 2018, vol. 131, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Z.; Ye, G.; Zhou, Y.; Pu, X.; Su, W.; Wang, J. Editing sterol side chain reductase 2 gene ( StSSR2 ) via CRISPR/Cas9 reduces the total steroidal glycoalkaloids in potato’. All Life 2021, vol. 14(no. 1), 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Ayzenshtat, D.; Rather, G. A.; Aisemberg, E.; Goldshmidt, A.; Bocobza, S. ‘Breaking the glass ceiling of stable genetic transformation and gene editing in the popular pepper cv Cayenne’. Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, vol. 76(no. 10), 2688–2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulle, M.; Venkatapuram, A. K.; Abbagani, S.; Kirti, P. B. ‘CRISPR/Cas9 based genome editing of Phytoene desaturase (PDS) gene in chilli pepper (Capsicum annuum L.)’. Journal of Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology 2024, vol. 22(no. 2), 100380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, H.; Li, J. ‘De novo domestication: retrace the history of agriculture to design future crops’. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2023, vol. 81, 102946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, T. ‘Domestication of wild tomato is accelerated by genome editing’. Nat Biotechnol 2018, vol. 36(no. 12), 1160–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, F.; Gong, H.; Bao, Y.; Zeng, S.; Huang, H.; Wang, Y. ‘CRISPR gene editing of major domestication traits accelerating breeding for Solanaceae crops improvement’. Plant Mol Biol 2022, vol. 108(no. 3), 157–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zsögön. ‘De novo domestication of wild tomato using genome editing’. Nat Biotechnol 2018, vol. 36(no. 12), 1211–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemmon, Z. H. ‘Rapid improvement of domestication traits in an orphan crop by genome editing’. Nature Plants 2018, vol. 4(no. 10), 766–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinnen, G.; Goossens, A.; Pauwels, L. ‘Lessons from Domestication: Targeting Cis-Regulatory Elements for Crop Improvement’. Trends in Plant Science 2016, vol. 21(no. 6), 506–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Leal, D.; Lemmon, Z. H.; Man, J.; Bartlett, M. E.; Lippman, Z. B. ‘Engineering Quantitative Trait Variation for Crop Improvement by Genome Editing’. Cell 2017, vol. 171(no. 2), 470–480.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Feng, Q.; Snouffer, A.; Zhang, B.; Rodríguez, G. R.; Van Der Knaap, E. ‘Increasing Fruit Weight by Editing a Cis-Regulatory Element in Tomato KLUH Promoter Using CRISPR/Cas9’. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, vol. 13, 879642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinert, J.; Schiml, S.; Puchta, H. ‘Homology-based double-strand break-induced genome engineering in plants’. Plant Cell Rep 2016, vol. 35(no. 7), 1429–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danilo; Perrot, L.; Mara, K.; Botton, E.; Nogué, F.; Mazier, M. ‘Efficient and transgene-free gene targeting using Agrobacterium-mediated delivery of the CRISPR/Cas9 system in tomato’. Plant Cell Rep 2019, vol. 38(no. 4), 459–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Q. ‘CRISPR/Cas9-induced Targeted Mutagenesis and Gene Replacement to Generate Long-shelf Life Tomato Lines’. Sci Rep 2017, vol. 7(no. 1), 11874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayut, S. Filler; Bessudo, C. Melamed; Levy, A. A. ‘Targeted recombination between homologous chromosomes for precise breeding in tomato’. Nat Commun 2017, vol. 8(no. 1), 15605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahan-Meir, T. ‘Efficient in planta gene targeting in tomato using geminiviral replicons and the CRISPR /Cas9 system’. The Plant Journal 2018, vol. 95(no. 1), 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čermák, T.; Baltes, N. J.; Čegan, R.; Zhang, Y.; Voytas, D. F. ‘High-frequency, precise modification of the tomato genome’. Genome Biol 2015, vol. 16(no. 1), 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegde, N.; Joshi, S.; Soni, N.; Kushalappa, A. C. ‘The caffeoyl-CoA O-methyltransferase gene SNP replacement in Russet Burbank potato variety enhances late blight resistance through cell wall reinforcement’. Plant Cell Rep 2021, vol. 40(no. 1), 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. Van Eck; Cornell University; USA; and The Boyce Thompson Institute. ‘Genome editing of tomatoes and other Solanaceae’. In Burleigh Dodds Series in Agricultural Science; Cornell University, USA, Willmann, M. R., Eds.; Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing, 2021; pp. 421–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T. V. ‘Highly efficient homology-directed repair using CRISPR/Cpf1-geminiviral replicon in tomato’. Plant Biotechnology Journal 2020, vol. 18(no. 10), 2133–2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, N. M.; Baltes, N. J.; Voytas, D. F.; Douches, D. S. ‘Geminivirus-Mediated Genome Editing in Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) Using Sequence-Specific Nucleases’. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, vol. 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, F.; Doudna, J. A. ‘CRISPR–Cas9 Structures and Mechanisms’. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 2017, vol. 46(no. 1), 505–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzalone, V.; Koblan, L. W.; Liu, D. R. ‘Genome editing with CRISPR–Cas nucleases, base editors, transposases and prime editors’. Nat Biotechnol 2020, vol. 38(no. 7), 824–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimatani, Z. ‘Targeted base editing in rice and tomato using a CRISPR-Cas9 cytidine deaminase fusion’. Nat Biotechnol 2017, vol. 35(no. 5), 441–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veillet, F. ‘Expanding the CRISPR Toolbox in P. patens Using SpCas9-NG Variant and Application for Gene and Base Editing in Solanaceae Crops’. IJMS 2020, vol. 21(no. 3), 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sretenovic, S. ‘Exploring C-To-G Base Editing in Rice, Tomato, and Poplar’, Front. Genome Ed. 2021, vol. 3, 756766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunziker, J.; Nishida, K.; Kondo, A.; Kishimoto, S.; Ariizumi, T.; Ezura, H. ‘Multiple gene substitution by Target-AID base-editing technology in tomato’. Sci Rep 2020, vol. 10(no. 1), 20471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S. ‘Efficient base editing in tomato using a highly expressed transient system’. Plant Cell Rep 2021, vol. 40(no. 4), 667–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Y. ‘Efficient C-to-T base editing in plants using a fusion of nCas9 and human APOBEC3A’. Nat Biotechnol 2018, vol. 36(no. 10), 950–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veillet, F. ‘The Solanum tuberosum GBSSI gene: a target for assessing gene and base editing in tetraploid potato’. Plant Cell Rep 2019, vol. 38(no. 9), 1065–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. ‘Plant base editing and prime editing: The current status and future perspectives’. JIPB 2023, vol. 65(no. 2), 444–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y. ‘Precise genome modification in tomato using an improved prime editing system’. Plant Biotechnology Journal 2021, vol. 19(no. 3), 415–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vu, T. V.; Nguyen, N. T.; Kim, J.; Song, Y. J.; Nguyen, T. H.; Kim, J.-Y. ‘Optimized dicot prime editing enables heritable desired edits in tomato and Arabidopsis’. Nat. Plants 2024, vol. 10(no. 10), 1502–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, H. ‘Engineering source-sink relations by prime editing confers heat-stress resilience in tomato and rice’. Cell 2025, vol. 188(no. 2), 530–549.e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Y. ‘Precise deletion, replacement and inversion of large DNA fragments in plants using dual prime editing’. Nat. Plants 2025, vol. 11(no. 2), 191–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perroud, P.-F. ‘Prime Editing in the model plant Physcomitrium patens and its potential in the tetraploid potato’. Plant Science 2022, vol. 316, 111162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Russa, M. F.; Qi, L. S. ‘The New State of the Art: Cas9 for Gene Activation and Repression’. Molecular and Cellular Biology 2015, vol. 35(no. 22), 3800–3809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Qi, L. S. Repurposing CRISPR System for Transcriptional Activation’, in RNA Activation, vol. 983. In Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Li, L.-C., Ed.; Springer Singapore: Singapore, 2017; vol. 983. pp. 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, J. E.; Kue Foka, I. C.; Lawton, M. A.; Di, R. ‘CRISPR activation: identifying and using novel genes for plant disease resistance breeding’. Front. Genome Ed. 2025, vol. 7, 1596600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Murillo, L. ‘CRISPRa-mediated transcriptional activation of the SlPR-1 gene in edited tomato plants’. Plant Science 2023, vol. 329, 111617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rivera-Toro, M.; De Folter, S.; Alvarez-Venegas, R. ‘CRISPR/dCas12a-mediated activation of SlPAL2 enhances tomato resistance against bacterial canker disease’. PLoS ONE 2025, vol. 20(no. 3), e0320436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Lozano. ‘Editing of SlWRKY29 by CRISPR-activation promotes somatic embryogenesis in Solanum lycopersicum cv. Micro-Tom’. PLoS ONE 2024, vol. 19(no. 4), e0301169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee; Jodder, J.; Chowdhury, S.; Das, H.; Kundu, P. ‘A novel stress-inducible dCas9 system for solanaceous plants’. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2025, vol. 308, 142462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan. ‘CRISPR–Act3.0 for highly efficient multiplexed gene activation in plants’. Nat. Plants 2021, vol. 7(no. 7), 942–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casas-Mollano, J. A.; Zinselmeier, M. H.; Sychla, A.; Smanski, M. J. ‘Efficient gene activation in plants by the MoonTag programmable transcriptional activator’. Nucleic Acids Research 2023, vol. 51(no. 13), 7083–7093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L. ‘The evaluation of active transcriptional repressor domain for CRISPRi in plants’. Gene 2023, vol. 851, 146967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, R.; Tiwari, B. S. ‘CRISPRi/dCas9-KRAB mediated suppression of Solanidine galactosyltransferase (sgt1) in Solanum tuberosum leads to the reduction in α-solanine level in potato tubers without any compensatory effect in α-chaconine.’. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2024, vol. 58, 103133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernabé-Orts, J. M. ‘Assessment of Cas12a-mediated gene editing efficiency in plants’. Plant Biotechnology Journal 2019, vol. 17(no. 10), 1971–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, R. T.; Christie, K. A.; Whittaker, M. N.; Kleinstiver, B. P. ‘Unconstrained genome targeting with near-PAMless engineered CRISPR-Cas9 variants’. Science 2020, vol. 368(no. 6488), 290–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veillet. ‘Expanding the CRISPR Toolbox in P. patens Using SpCas9-NG Variant and Application for Gene and Base Editing in Solanaceae Crops’. IJMS 2020, vol. 21(no. 3), 1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarova, K. S. ‘An updated evolutionary classification of CRISPR–Cas systems including rare variants’. Nat Microbiol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bandyopadhyay; Kancharla, N.; Javalkote, V. S.; Dasgupta, S.; Brutnell, T. P. ‘CRISPR-Cas12a (Cpf1): A Versatile Tool in the Plant Genome Editing Tool Box for Agricultural Advancement’. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, vol. 11, 584151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zetsche. ‘Cpf1 Is a Single RNA-Guided Endonuclease of a Class 2 CRISPR-Cas System’. Cell 2015, vol. 163(no. 3), 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L. ‘Engineered Cpf1 variants with altered PAM specificities’. Nat Biotechnol 2017, vol. 35(no. 8), 789–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tóth. ‘Improved LbCas12a variants with altered PAM specificities further broaden the genome targeting range of Cas12a nucleases’. Nucleic Acids Research 2020, vol. 48(no. 7), 3722–3733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slaman, E.; Kottenhagen, L.; De Martines, W.; Angenent, G. C.; De Maagd, R. A. ‘Comparison of Cas12a and Cas9-mediated mutagenesis in tomato cells’. Sci Rep 2024, vol. 14(no. 1), 4508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu, T. V.; Doan, D. T. H.; Tran, M. T.; Sung, Y. W.; Song, Y. J.; Kim, J.-Y. ‘Improvement of the LbCas12a-crRNA System for Efficient Gene Targeting in Tomato’. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, vol. 12, 722552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavuri, N. R.; Ramasamy, M.; Qi, Y.; Mandadi, K. ‘Applications of CRISPR/Cas13-Based RNA Editing in Plants’. Cells 2022, vol. 11(no. 17), 2665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, X. ‘Generation of virus-resistant potato plants by RNA genome targeting’. Plant Biotechnology Journal 2019, vol. 17(no. 9), 1814–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, X.; Liu, W.; Nie, B.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, J. ‘Cas13d-mediated multiplex RNA targeting confers a broad-spectrum resistance against RNA viruses in potato’. Commun Biol 2023, vol. 6(no. 1), 855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noureen. Broad-spectrum resistance against multiple PVY-strains by CRSIPR/Cas13 system in Solanum tuberosum crop’. GM Crops & Food 2022, vol. 13(no. 1), 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, Y. W. ‘Resistance of the CRISPR-Cas13a Gene-Editing System to Potato Spindle Tuber Viroid Infection in Tomato and Nicotiana benthamiana’. Viruses 2024, vol. 16(no. 9), 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V. K. ‘CRISPR guides induce gene silencing in plants in the absence of Cas’. Genome Biol 2022, vol. 23(no. 1), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laforest, L. C.; Nadakuduti, S. S. Advances in Delivery Mechanisms of CRISPR Gene-Editing Reagents in Plants’, Front. Genome Ed. 2022, vol. 4, 830178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S. H.; Kim, S. W.; Lee, S.; Koo, Y. ‘Optimized protocols for protoplast isolation, transfection, and regeneration in the Solanum genus for the CRISPR/Cas-mediated transgene-free genome editing’. Appl Biol Chem 2024, vol. 67(no. 1), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-S. ‘DNA-free CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing of wild tetraploid tomato Solanum peruvianum using protoplast regeneration’. Plant Physiology 2022, vol. 188(no. 4), 1917–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolia; Andersson, M.; Hofvander, P.; Festa, G.; Cardi, T. ‘Tomato protoplasts as cell target for ribonucleoprotein (RNP)-mediated multiplexed genome editing’. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult 2021, vol. 144(no. 2), 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Andersson, M.; Granell, A.; Cardi, T.; Hofvander, P.; Nicolia, A. ‘Establishment of a DNA-free genome editing and protoplast regeneration method in cultivated tomato (Solanum lycopersicum)’. Plant Cell Rep 2022, vol. 41(no. 9), 1843–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, H.; Kang, B.-C.; Han, J.-S.; Lee, J. M. ‘DNA-free genome editing in tomato protoplasts using CRISPR/Cas9 ribonucleoprotein delivery’. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2024, vol. 65(no. 1), 131–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, M. N. ‘Comparative potato genome editing: Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated transformation and protoplasts transfection delivery of CRISPR/Cas9 components directed to StPPO2 gene’. Plant Cell Tiss Organ Cult 2021, vol. 145(no. 2), 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, M. ‘Genome editing in potato via CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein delivery’. Physiologia Plantarum 2018, vol. 164(no. 4), 378–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X. ‘Amylose starch with no detectable branching developed through DNA-free CRISPR-Cas9 mediated mutagenesis of two starch branching enzymes in potato’. Sci Rep 2021, vol. 11(no. 1), 4311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, K.-B. ‘Editing of StSR4 by Cas9-RNPs confers resistance to Phytophthora infestans in potato’. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, vol. 13, 997888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi; Shin, H.; Kim, C. Y.; Park, J.; Kim, H. Highly efficient CRISPR/Cas9-RNP mediated CaPAD1 editing in protoplasts of three pepper ( Capsicum annuum L.) cultivars’. Plant Signaling & Behavior 2024, vol. 19(no. 1), 2383822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim; Choi, J.; Won, K.-H. ‘A stable DNA-free screening system for CRISPR/RNPs-mediated gene editing in hot and sweet cultivars of Capsicum annuum’. BMC Plant Biology 2020, vol. 20(no. 1), 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, J.-H.; Kim, H. ‘Harnessing CRISPR/Cas9 for Enhanced Disease Resistance in Hot Peppers: A Comparative Study on CaMLO2-Gene-Editing Efficiency across Six Cultivars’. IJMS 2023, vol. 24(no. 23), 16775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y. ‘A highly efficient mesophyll protoplast isolation and PEG-mediated transient expression system in eggplant’. Scientia Horticulturae 2022, vol. 304, 111303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fish, N.; Karp, A.; Jones, M. G. K. ‘Production of somatic hybrids by electrofusion in Solanum’. Theoret. Appl. Genetics 1988, vol. 76(no. 2), 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, H.; Ooms, G.; Jones, M. G. K. ‘Transient gene expression in electroporated Solanum protoplasts’. Plant Mol Biol 1989, vol. 13(no. 5), 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banakar, R.; Schubert, M.; Collingwood, M.; Vakulskas, C.; Eggenberger, A. L.; Wang, K. ‘Comparison of CRISPR-Cas9/Cas12a Ribonucleoprotein Complexes for Genome Editing Efficiency in the Rice Phytoene Desaturase (OsPDS) Gene’. Rice 2020, vol. 13(no. 1), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghogare, R.; Ludwig, Y.; Bueno, G. M.; Slamet-Loedin, I. H.; Dhingra, A. ‘Genome editing reagent delivery in plants’. Transgenic Res 2021, vol. 30(no. 4), 321–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W. ‘Lipofection-mediated genome editing using DNA-free delivery of the Cas9/gRNA ribonucleoprotein into plant cells’. Plant Cell Rep 2020, vol. 39(no. 2), 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R. ‘CRISPR/Cas9-Based Knock-Out of the PMR4 Gene Reduces Susceptibility to Late Blight in Two Tomato Cultivars’. IJMS 2022, vol. 23(no. 23), 14542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uranga, M. ‘Virus-Induced Genome Editing’. In CRISPR and Plant Functional Genomics, 1st edn; CRC Press: Boca Raton, 2024; pp. 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, S.; Li, X.; Zhang, R.; Li, J. ‘Virus-Induced Gene Editing and Its Applications in Plants’. IJMS 2022, vol. 23(no. 18), 10202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.; Abul-faraj, A.; Piatek, M.; Mahfouz, M. M. ‘Activity and specificity of TRV-mediated gene editing in plants’. Plant Signaling & Behavior 2015, vol. 10(no. 10), e1044191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellison, E. E.; Nagalakshmi, U.; Gamo, M. E.; Huang, P.; Dinesh-Kumar, S.; Voytas, D. F. ‘Multiplexed heritable gene editing using RNA viruses and mobile single guide RNAs’. Nat. Plants 2020, vol. 6(no. 6), 620–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-Y. ‘Development of virus-induced genome editing methods in Solanaceous crops’. Horticulture Research 2024, vol. 11(no. 1), uhad233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Baik, J. E.; Kim, K.-N. Development of an efficient and heritable virus-induced genome editing system in Solanum lycopersicum’. Horticulture Research 2025, vol. 12(no. 4), uhae364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, G. H.; Ko, Y.; Lee, J. M. ‘Enhancing virus-mediated genome editing for cultivated tomato through low temperature’. Plant Cell Rep 2025, vol. 44(no. 1), 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Y. ‘Heritable virus-induced germline editing in tomato’. The Plant Journal 2025, vol. 122(no. 1), e70115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uranga, M. ‘RNA virus-mediated gene editing for tomato trait breeding’. Horticulture Research 2024, vol. 11(no. 1), uhad279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, D.; Dai, Y.; Liu, C. ‘Efficient tobacco rattle virus-induced gene editing in tomato mediated by the CRISPR/Cas9 system’. Biotechnology Journal 2024, vol. 19(no. 5), 2400204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Q.; Zhao, C.; Sun, K.; Deng, Y.; Li, Z. ‘Engineered biocontainable RNA virus vectors for non-transgenic genome editing across crop species and genotypes’. Molecular Plant 2023, vol. 16(no. 3), 616–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B. ‘Virus-induced systemic and heritable gene editing in pepper ( Capsicum annuum L.)’. The Plant Journal 2025, vol. 122(no. 5), e70257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Lou, H.; Liu, Q.; Pei, S.; Liao, Q.; Li, Z. ‘Efficient and transformation-free genome editing in pepper enabled by RNA virus-mediated delivery of CRISPR/Cas9’. JIPB 2024, vol. 66(no. 10), 2079–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Yang, B.; Wang, D. ‘Achieving Plant Genome Editing While Bypassing Tissue Culture’. Trends in Plant Science 2020, vol. 25(no. 5), 427–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, M. F.; Nasti, R. A.; Vollbrecht, M.; Starker, C. G.; Clark, M. D.; Voytas, D. F. ‘Plant gene editing through de novo induction of meristems’. Nat Biotechnol 2020, vol. 38(no. 1), 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, H.; Li, C.; Gao, C. ‘Applications of CRISPR–Cas in agriculture and plant biotechnology’. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2020, vol. 21(no. 11), 661–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D. ‘Heritable gene editing in tomato through viral delivery of isopentenyl transferase and single-guide RNAs to latent axillary meristematic cells’. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2024, vol. 121(no. 39), e2406486121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kshetry, O. ‘A synthetic transcription cascade enables direct in planta shoot regeneration for transgenesis and gene editing in multiple plants’. Molecular Plant 2025, vol. 18(no. 12), 2066–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lian, Z. ‘Application of developmental regulators to improve in planta or in vitro transformation in plants’. Plant Biotechnology Journal 2022, vol. 20(no. 8), 1622–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, S. ‘Efficient base editing in tomato using a highly expressed transient system’. Plant Cell Rep 2021, vol. 40(no. 4), 667–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Parliament. ‘Directive 2001/18/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 March 2001 on the deliberate release into the environment of genetically modified organisms and repealing Council Directive 90/220/EEC.’ Apr. 17, 2001. 08 May 2025. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32001L0018&rid=1.

- Habets, M. G. J. L.; Macnaghten, P. ‘From genes to governance: Engaging citizens in the new genomic techniques policy debate’. Plants People Planet 2024, p. ppp3.10626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. ‘Proposal for a REGULATION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on plants obtained by certain new genomic techniques and their food and feed, and amending Regulation (EU) 2017/625’. 05 Jul 2023. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/plants/genetically-modified-organisms/new-techniques-biotechnology_en.

- Council of the EU. ‘New genomic techniques: Council and Parliament strike deal to boost the competitiveness and sustainability of our food systems’. 04 Dec 2025. Available online: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2025/12/04/new-genomic-techniques-council-and-parliament-strike-deal-to-boost-the-competitiveness-and-sustainability-of-our-food-systems/.

- European Commission. Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety, EU’s rules new genomic techniques. Publications Office of the European Union: LU, 2025; Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2875/1144622.

- Zimny, T. ‘Regulation of GMO field trials in the EU and new genomic techniques: will the planned reform facilitate experimenting with gene-edited plants?’. BioTechnologia 2023, vol. 104(no. 1), 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK Parliament, Genetic Technology (Precision Breeding) Act 2023. 2023. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2023/6/contents.

- UK Parliament, The Genetic Technology (Precision Breeding) Regulations 2025. 2025. Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2025/581/contents/made.

- ACRE, ACRE guidance on producing precision bred plants. 2025. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/acre-guidance-on-producing-precision-bred-plants.

- Nicolia. Editing strigolactone biosynthesis genes in tomato reveals novel phenotypic effects and highlights D27 as a key target for parasitic weed resistance’. In Genetics; 06 Feb 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakthivel; Balasubramanian, R.; Sampathrajan, V.; Veerasamy, R.; Appachi, S. V.; K. K., K. ‘Transforming tomatoes into GABA-rich functional foods through genome editing: A modern biotechnological approach’. Funct Integr Genomics 2025, vol. 25(no. 1), 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waltz, E. ‘GABA-enriched tomato is first CRISPR-edited food to enter market’. Nat Biotechnol 2022, vol. 40(no. 1), 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlson, D. ‘Targeted Mutagenesis of the Multicopy Myrosinase Gene Family in Allotetraploid Brassica juncea Reduces Pungency in Fresh Leaves across Environments’. Plants 2022, vol. 11(no. 19), 2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Veriety | Gene | Nation | Notification number | Trait |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. lycopersicum | San Marzano | DMR6-1 | Italy | B/IT/25/03 | Tolerance to abiotic and biotic stress |

| S. lycopersicum | Alisa Craig | D27, CCD7 | Italy | B/IT/24/02 | Reduced strigolactones - resistance razmakto Orobanche spp. |

| S. lycopersicum | MoneyMaker | 7-DR2 | UK | 23/Q06 | Conversion of provitamin D3 to vitamin razmakD3 in sunlight |

| S. tuberosum | Ydun | DMR6-1 | Denmark | B/DK/24/23110 | Tolerance to late blight |

| S. tuberosum | Ydun | DMR6-1 | Denmark | B/DK/54/StDMR6-1 LoF Ydun | Altered sensitvity razmakto blight |

| S. tuberosum | Wotan | GBSS1 | Denmark | B/DK/55/Waxy Wotan | Amylopectin only starch |

| S. tuberosum | Various | Rpi-chc1, Rpi-cap1, ELR1, Peru / DND1, PMR4, DMR6-1, SR4 | Netherlands | B/NL/25/007 | Increased resistance / lower susceptibility to Phytophthora infestans |

| S. tuberosum | Kuras | DMR6-1 | Denmark | B/DK/25/Kuras | Tolerance to late blight |

| S. tuberosum | Ydun | CBP-1 | Denmark | B/DK/25/Ydun_v1 | Tolerance to late blight |

| S. tuberosum | NA | GBSS, SSS3, SSS2 | Sweden | B/SE/19/5614 | Lack of amylose starch |

| S. tuberosum | NA | DMR6, CHL1, AsS1, PiS1 | Sweden | B/SE/21/3359 | Altered resistance razmakto pathogens |

| S. tuberosum | NA | CHL1 | Sweden | B/SE/20/1726 | Altered resistance razmakto pathogens |

| S. tuberosum | NA | DMR6-1 | Sweden | B/SE/23/3093 | Altered resistance razmakto pathogens |

| S. tuberosum | Various | GBSS, SSS, SBE | Sweden | B/SE/22/23780 | Tailored starch quality |

| S. tuberosum | Various | GBSS, SSS3, SSS2, SSS1, SSS4, SSS5, SSS6, SBE1, SBE2 / RMA1H1, SMO1, DWF1, GAME9, DWF7, GAME6, GAME11, GAME4, GAME12 / DMR6, Parakletosis, eIF4E | Sweden | B/SE/24/20422 | Altered starch quality / decreased content of antinutritional compounds (TGA) / reduced susceptibility to late blight and PVY |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).