Submitted:

19 January 2026

Posted:

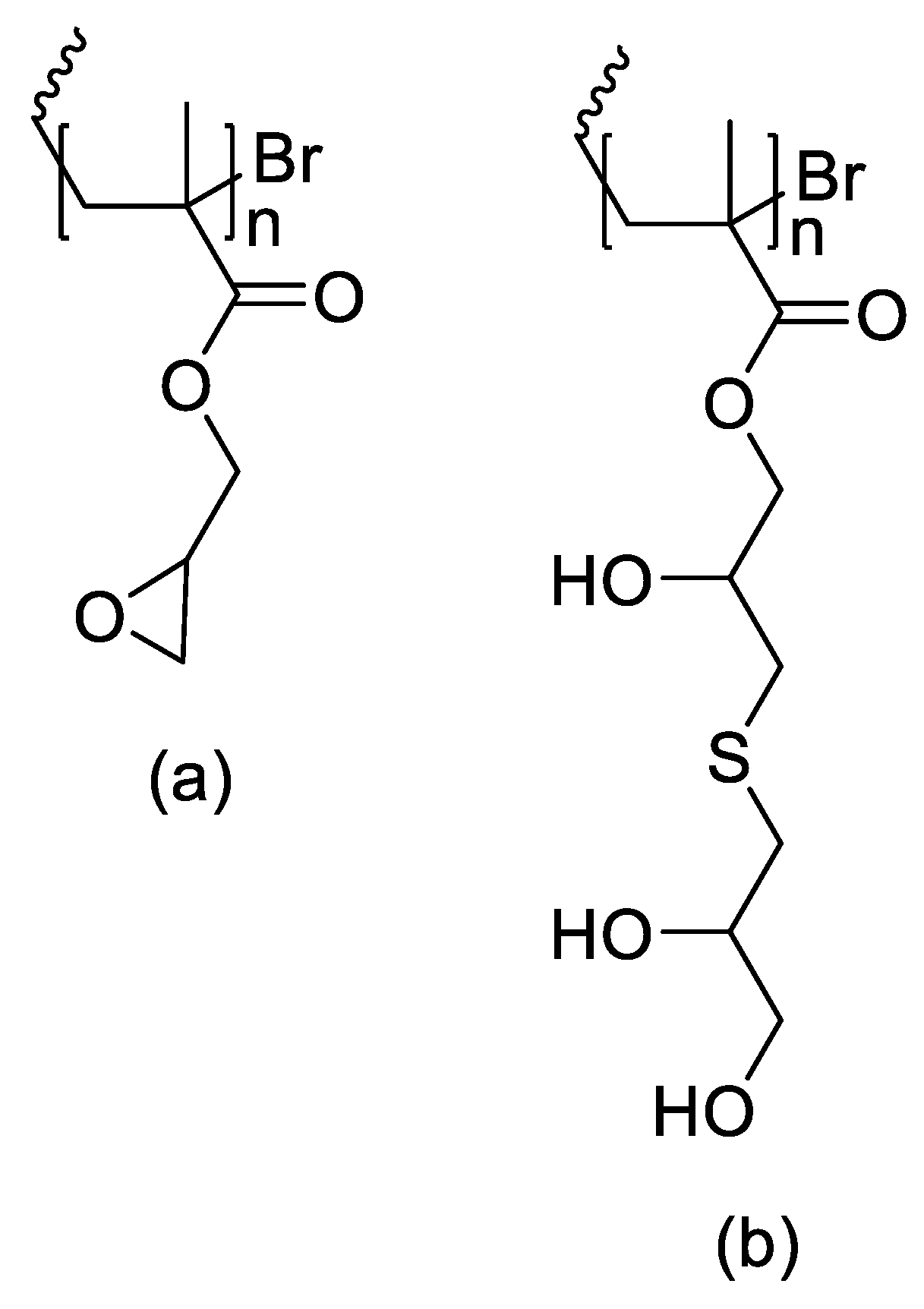

21 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Methodology of Literature Selection

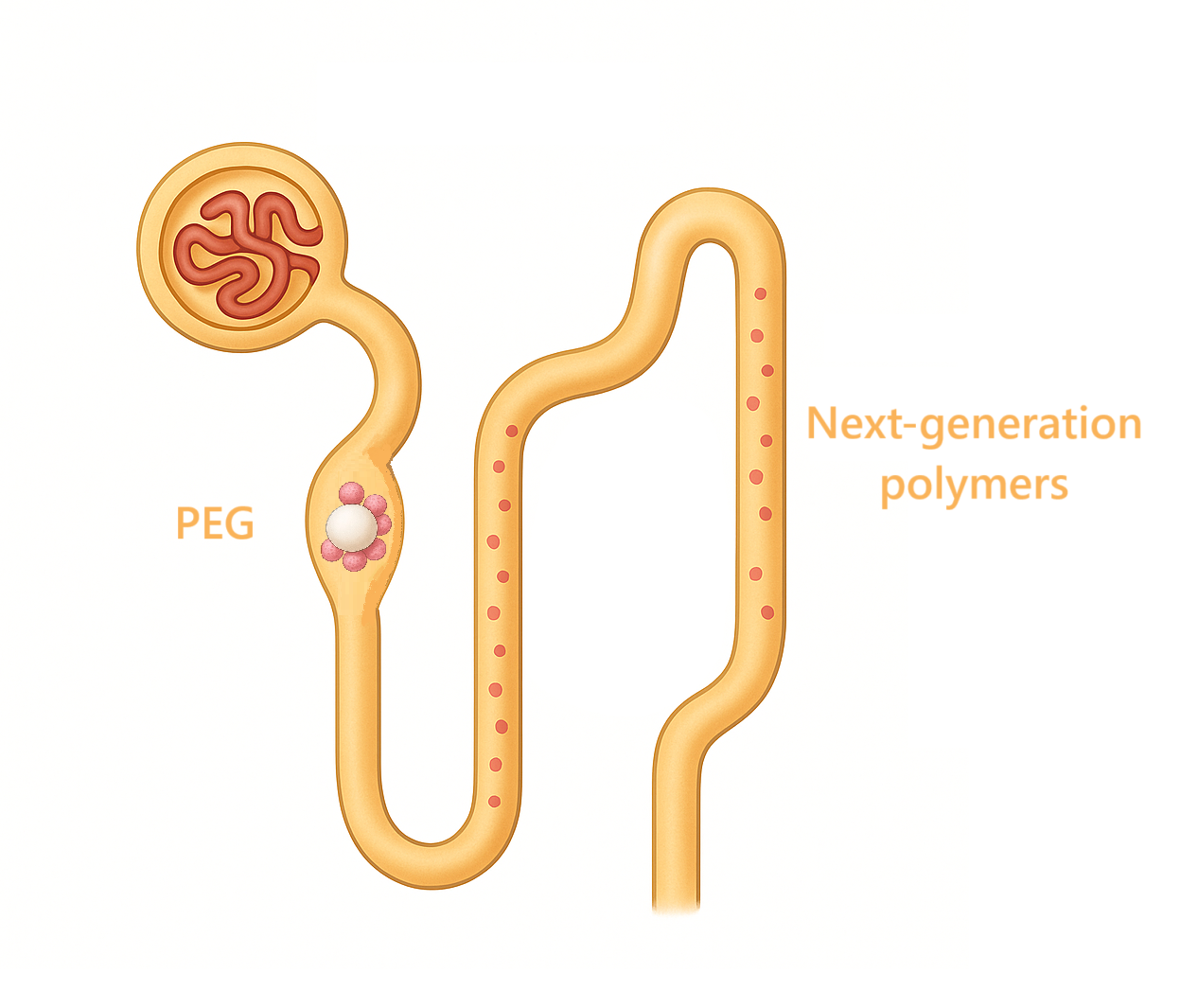

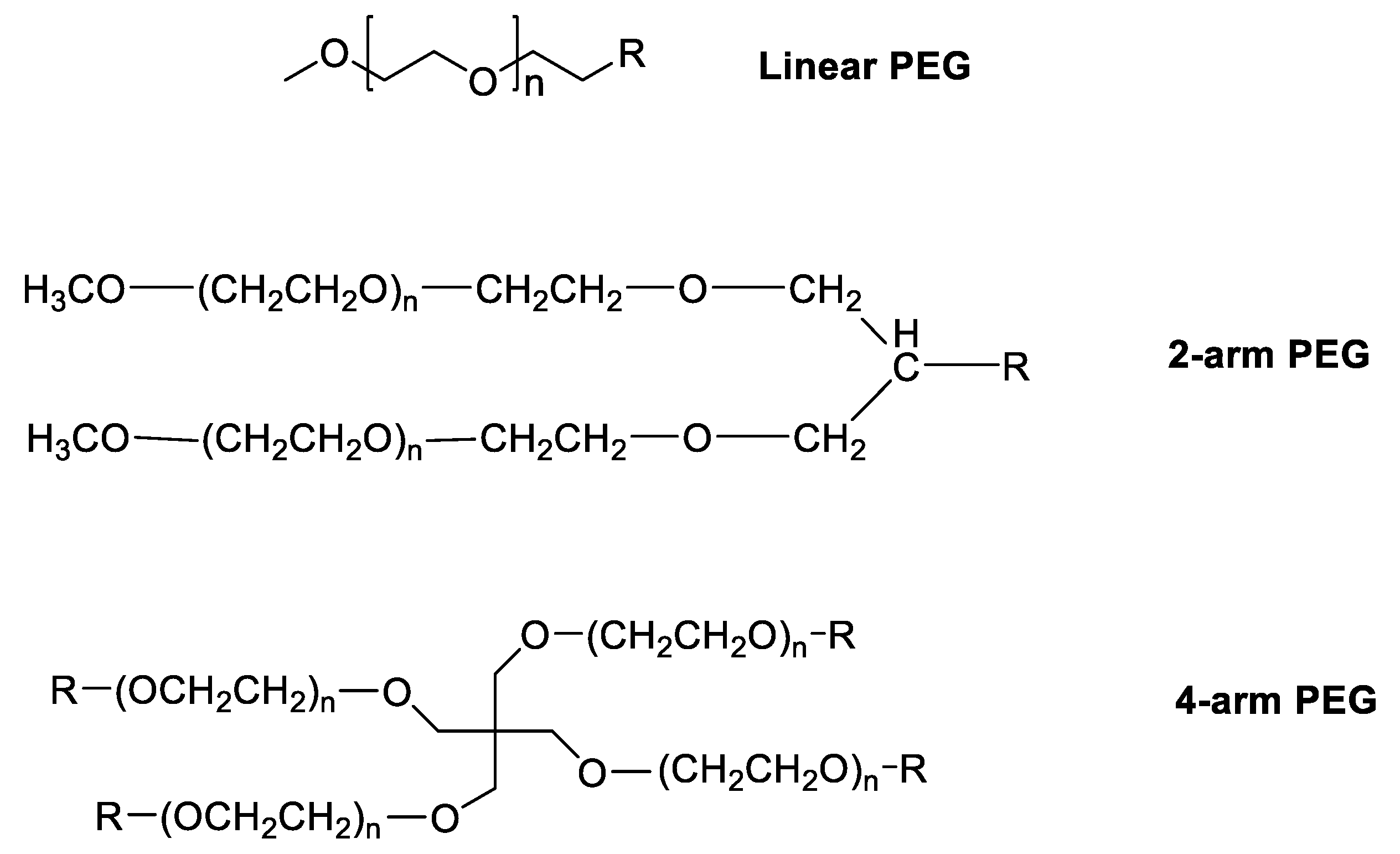

1.2. PEG Losing Its “Gold Standard” Role

1.3. Problems with Polymers

1.4. Delivery Problems

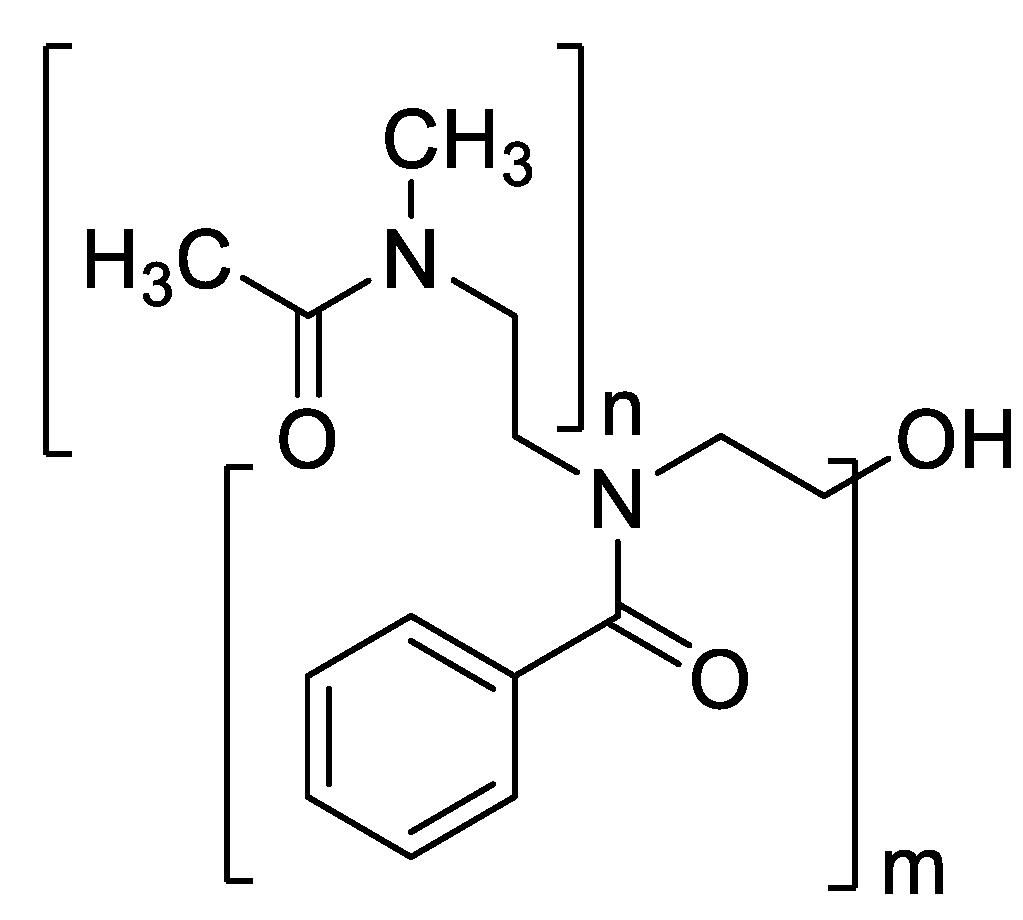

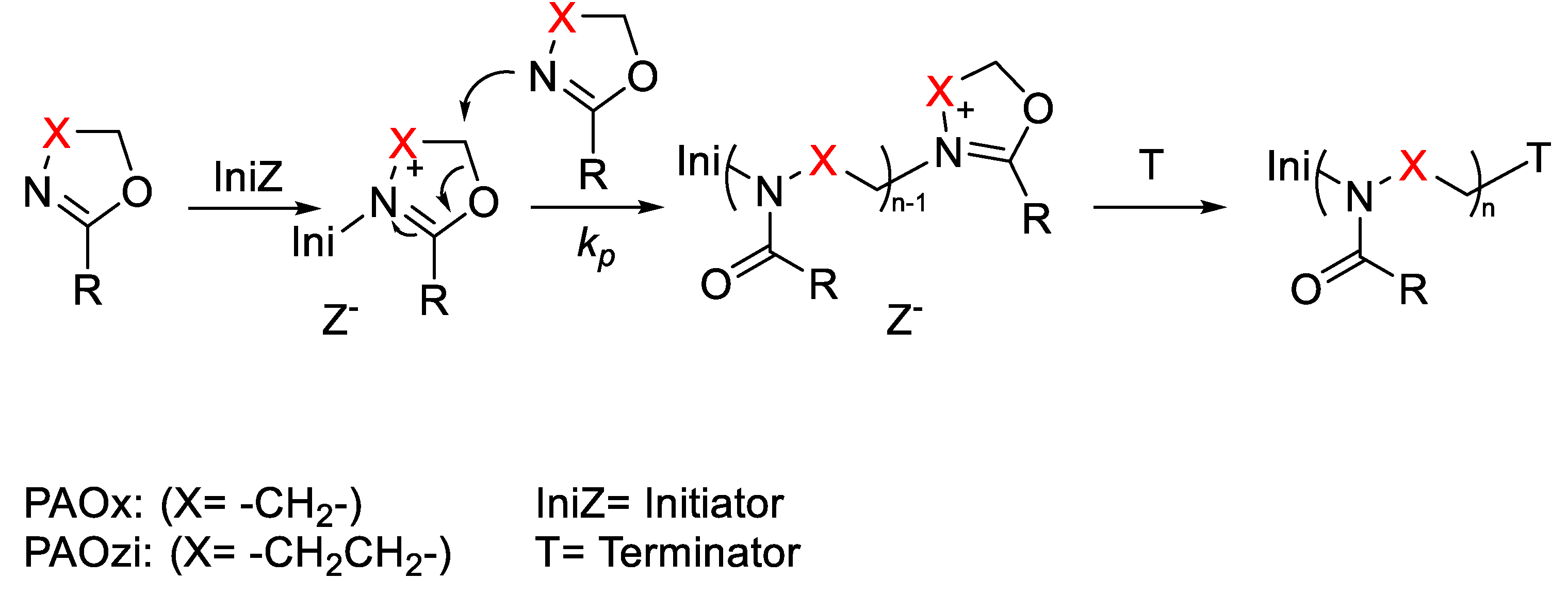

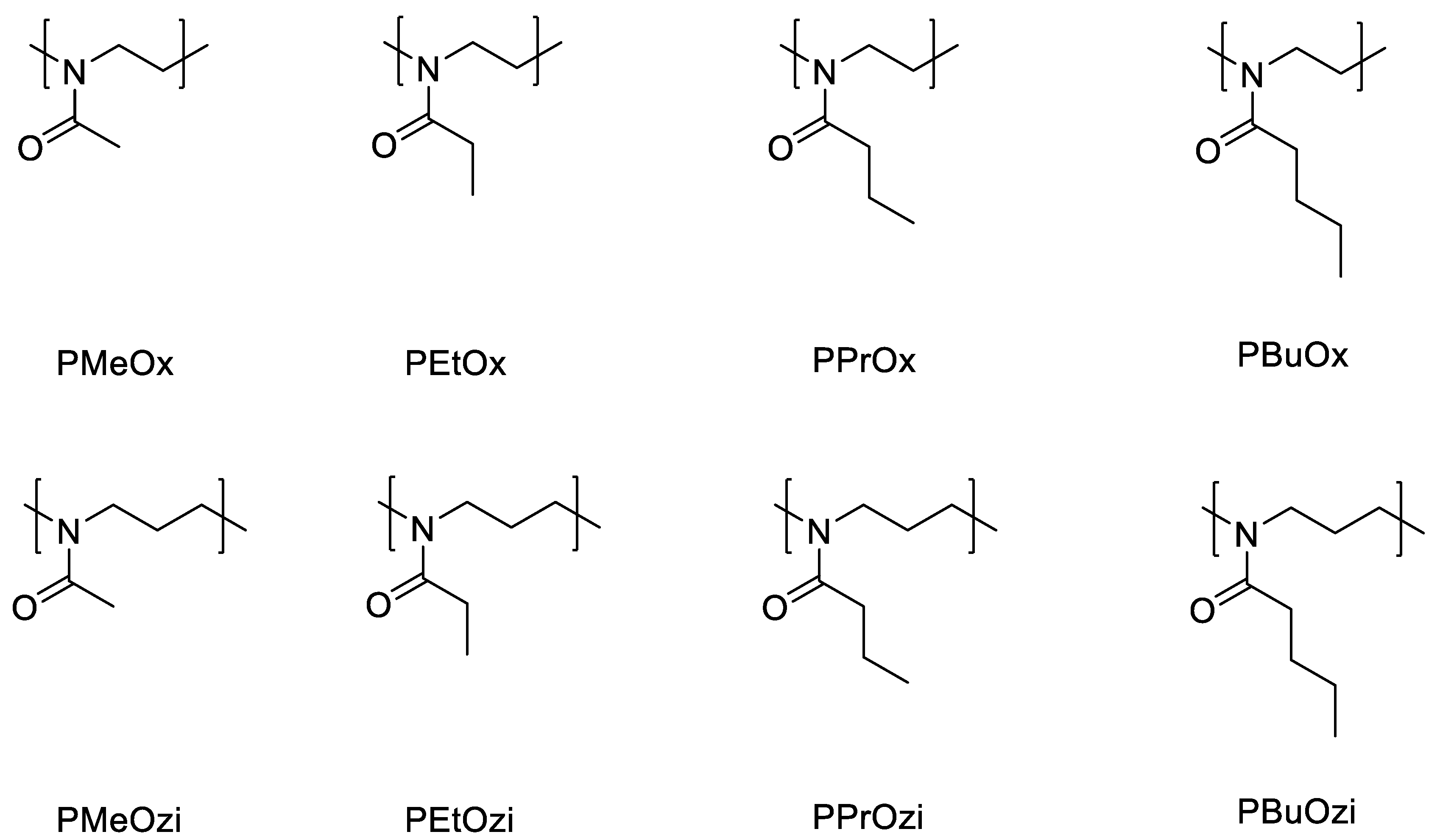

2. Poly(2-oxazoline)s (POx)

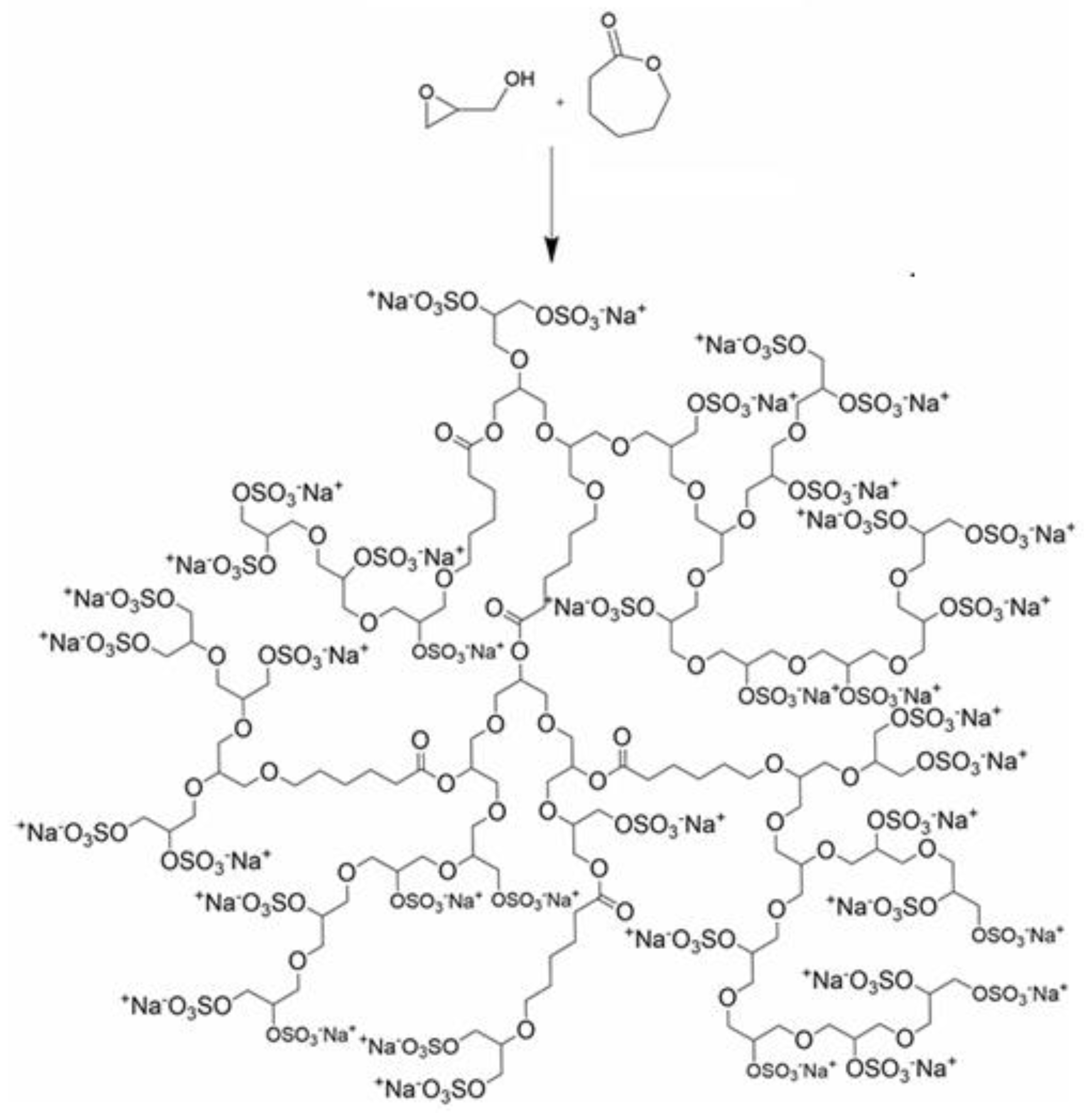

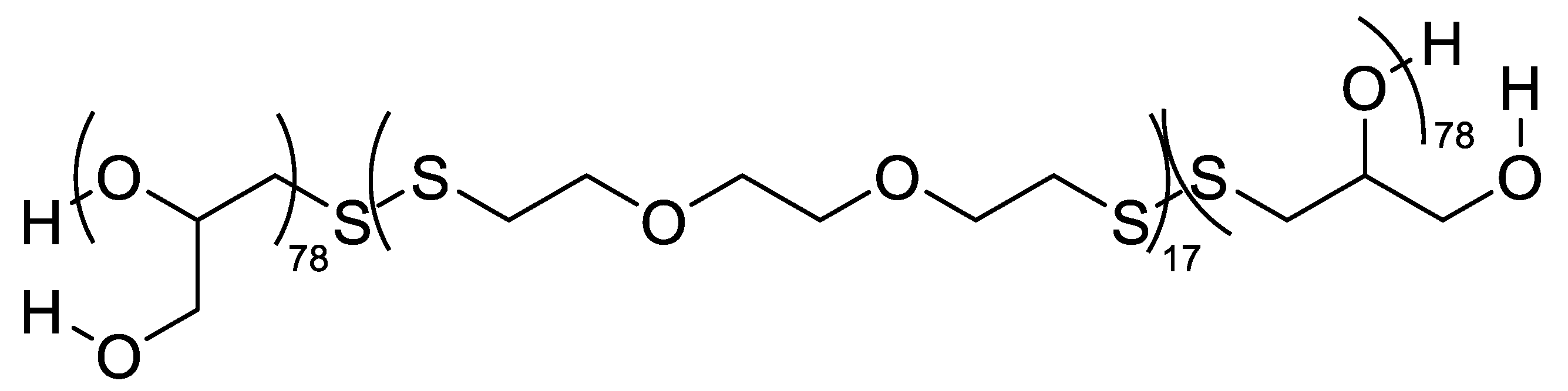

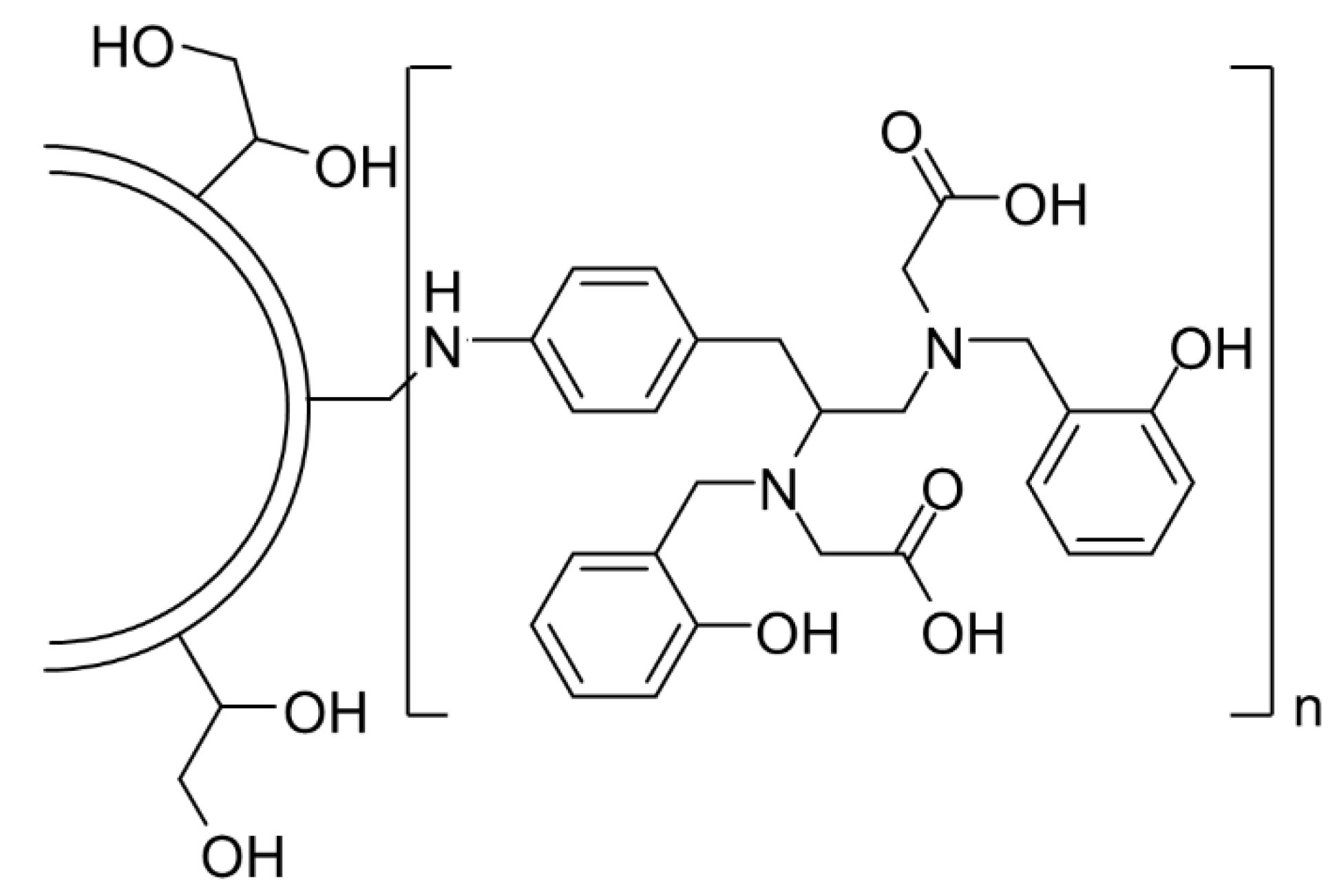

3. Polyglycerols (PGs)

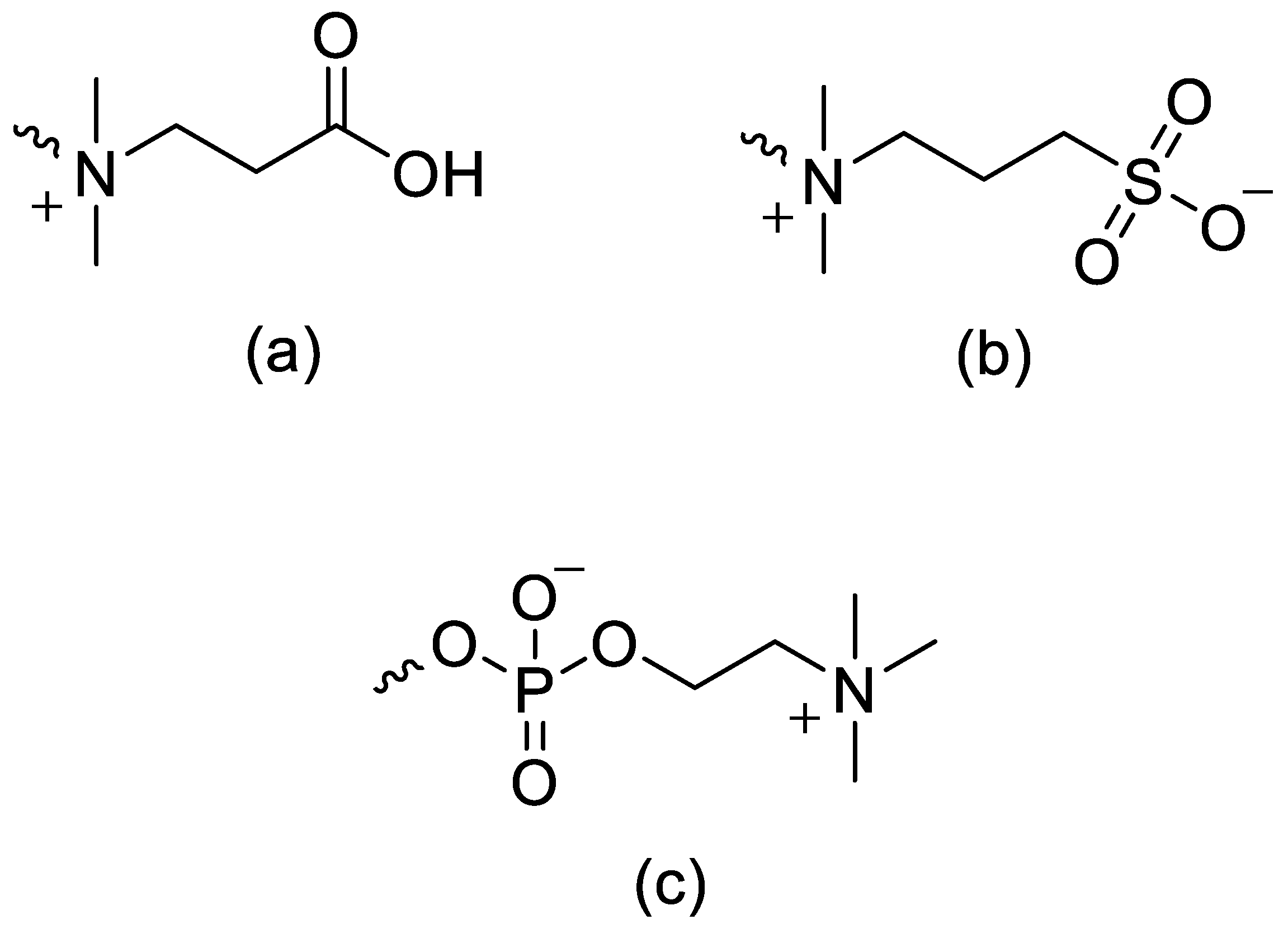

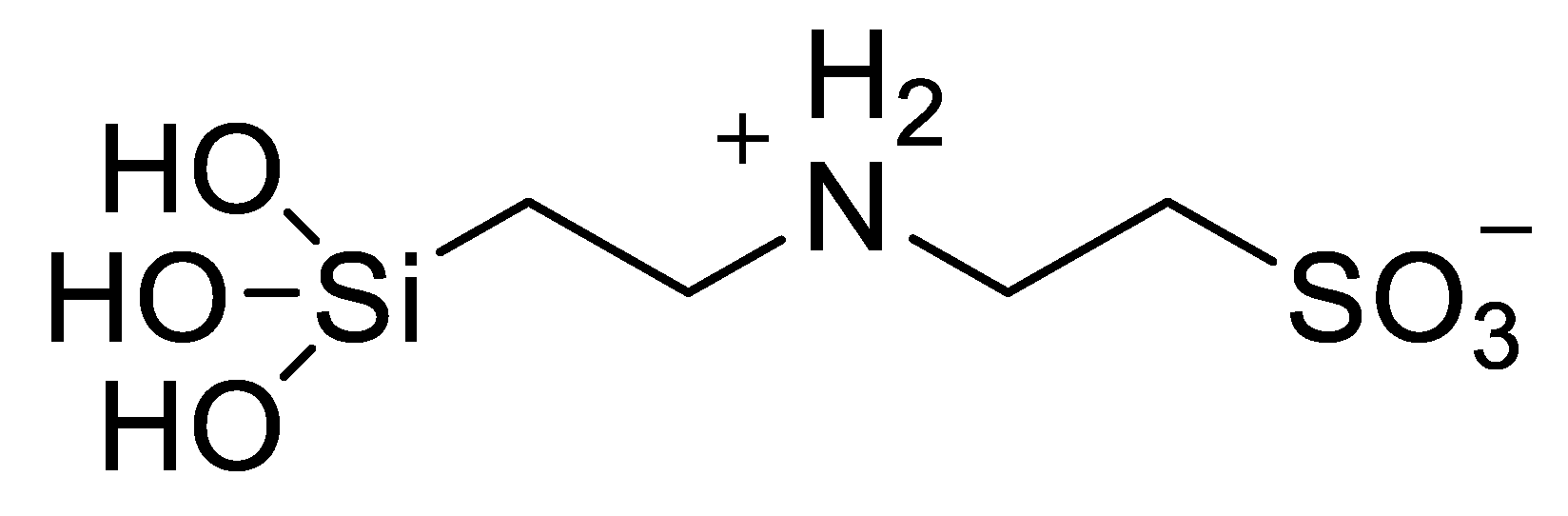

4. Zwitterionic Polymers

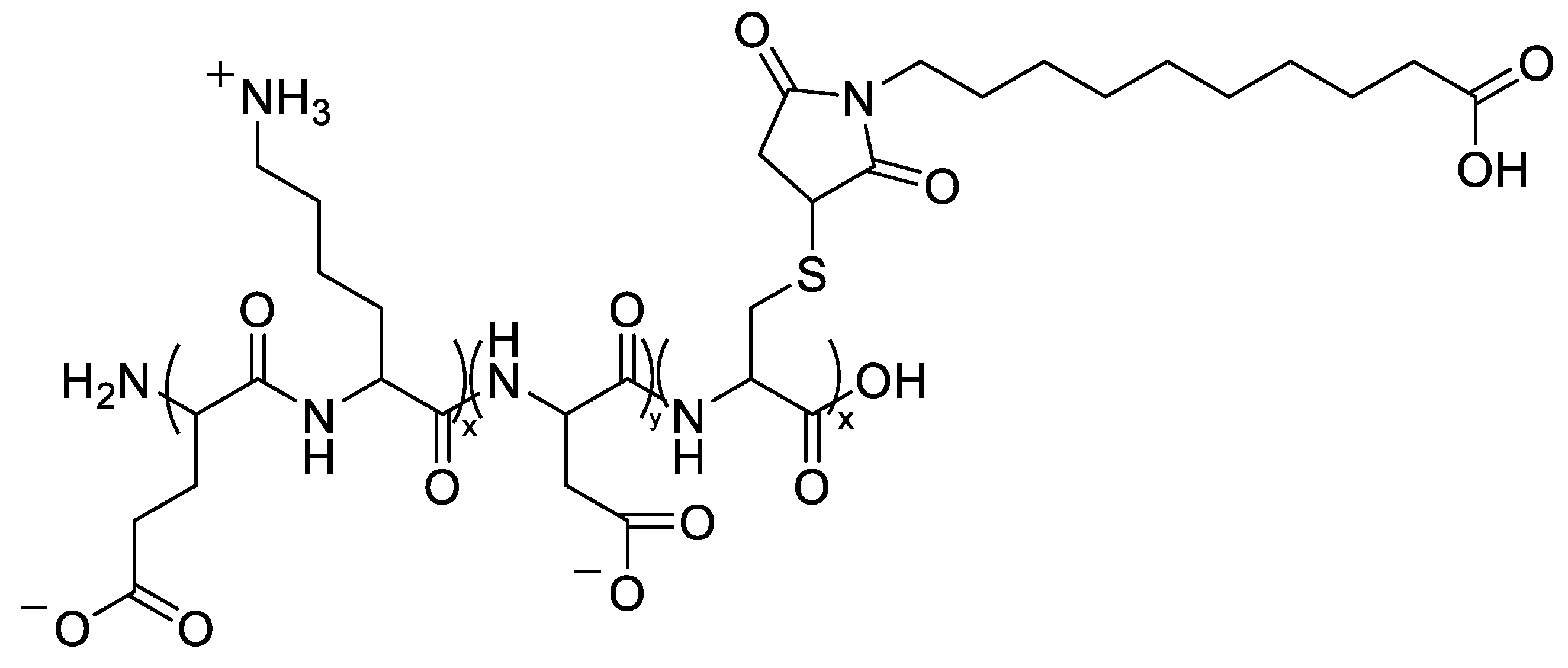

5. Polypeptides and Peptoids

6. Perspectives

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Porello, I.; Stucchi, F.; Guarini, R.; Sbaruffati, G.; Cellesi, F. TCEP-Enabled Click Modification of Glycidyl-Bearing Polymers with Biorelevant Sulfhydryl Molecules: Toward Chemoselective Bioconjugation Strategies. Biomacromolecules 2025, 26, 5269–5286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, D.; Dewangan, H.K. PEGylation: An Important Approach for Novel Drug Delivery System. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2021, 32, 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Sun, H.; Giannino, J.; Wu, Y.; Cheng, C. Biodegradable Zwitterionic Polymers as PEG Alternatives for Drug Delivery. J. Polym. Sci. 2024, 62, 2231–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ensminger, Y.; Rashmi, R.; Karimov, M.; Nölte, G.; Hafke, M.; Schmitt, A.C.; Díaz-Oviedo, D.; Köbberling, J.; Haag, R. Polyglycerol-Based Lipids: A Next-Generation Alternative to PEG in Lipid Nanoparticles for Advanced Drug Delivery Systems. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2025, e00428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Zyl, D.G.; Mendes, L.P.; Semper, R.P.; Rueckert, C.; Baumhof, P. Poly(2-methyl-2-oxazoline) as a Polyethylene Glycol Alternative for Lipid Nanoparticle Formulation. Front. Drug Deliv. 2024, 4, 1383038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbina, S.; Parambath, A. PEGylation and Its Alternatives. In Polymeric Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva Sanchez, A.J.; Loughrey, D.; Echeverri, E.S.; Huayamares, S.G.; Radmand, A.; Paunovska, K.; Hatit, M.; Tiegreen, K.E.; Santangelo, P.J.; Dahlman, J.E. Substituting Poly(ethylene glycol) Lipids with Poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline) Lipids Improves Lipid Nanoparticle Repeat Dosing. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2024, 13, 202304033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

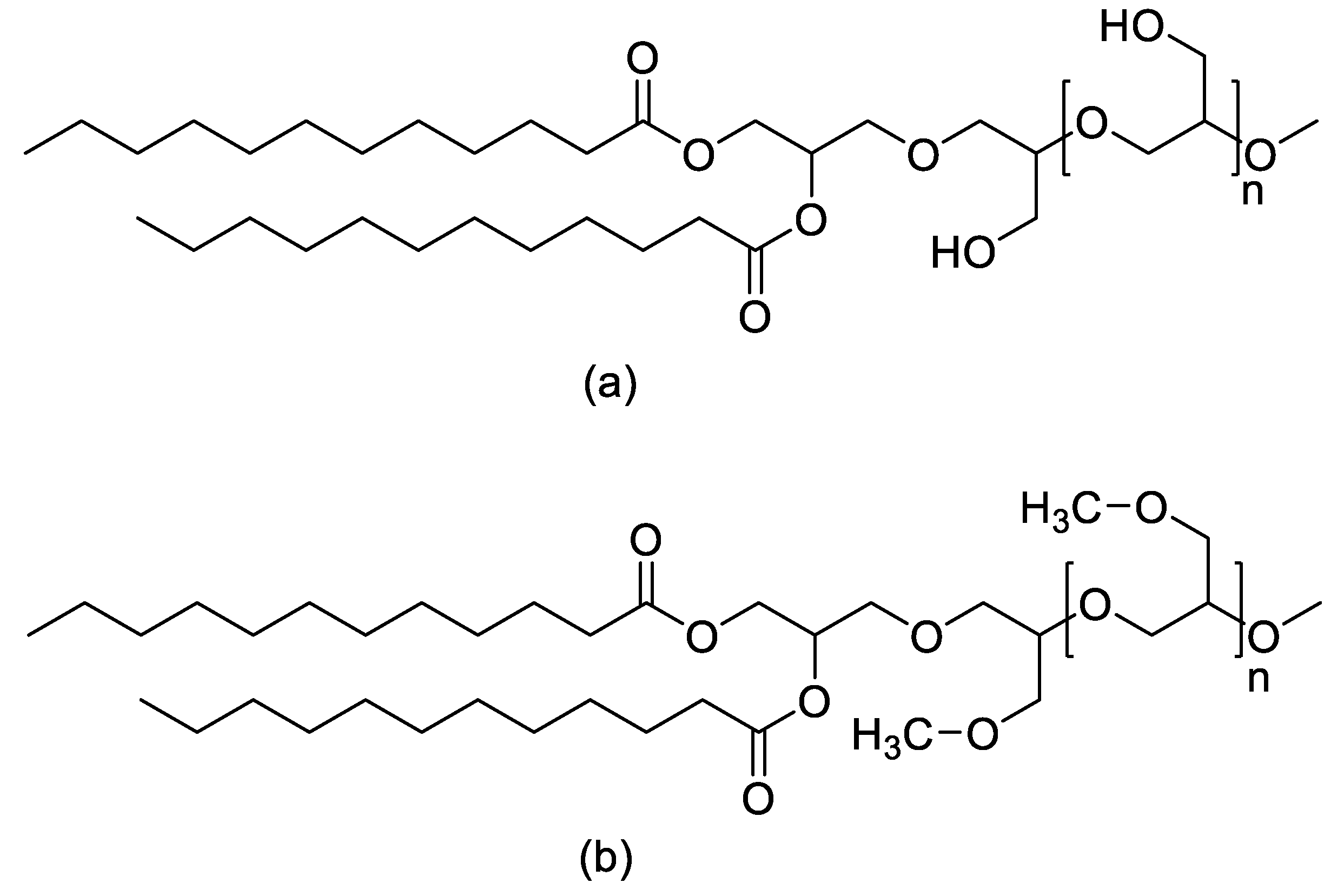

- Friedl, J.D.; Jörgensen, A.M.; Le, N.N.; Steinbring, C.; Bernkop-Schnürch, A. Replacing PEG-Surfactants in Self-Emulsifying Drug Delivery Systems: Surfactants with Polyhydroxy Head Groups for Advanced Cytosolic Drug Delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2022, 618, 121633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, B.; Becer, C.R. Poly(2-oxazoline)-Based Drug Delivery Systems for Cancer Therapy. Eur. Polym. J. 2025, 114292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozma, G.T.; Shimizu, T.; Ishida, T.; Szebeni, J. Anti-PEG Antibodies: Properties, Formation, Testing and Role in Adverse Immune Reactions to PEGylated Nano-Biopharmaceuticals. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2020, 154–155, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogozina, O.; Ruiz-Fernández, C.; Martín-López, S.; Akatbach-Bousaid, I.; González-Muñoz, M.; Ramírez, E. Organ-Specific Immune-Mediated Reactions to Polyethylene Glycol and Polysorbate Excipients: Three Case Reports. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 14, 1293294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pouyan, P.; Zemella, A.; Schloßhauer, J.L.; Walter, R.M.; Haag, R.; Kubick, S. One-to-One Comparison of Cell-Free Synthesized Erythropoietin Conjugates Modified with Linear Polyglycerol and Polyethylene Glycol. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 33463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.S.; Kulkarni, Y.; Pierre, V.; Maski, M.; Wanner, C. Adverse Impacts of PEGylated Protein Therapeutics: A Targeted Literature Review. BioDrugs 2024, 38, 795–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

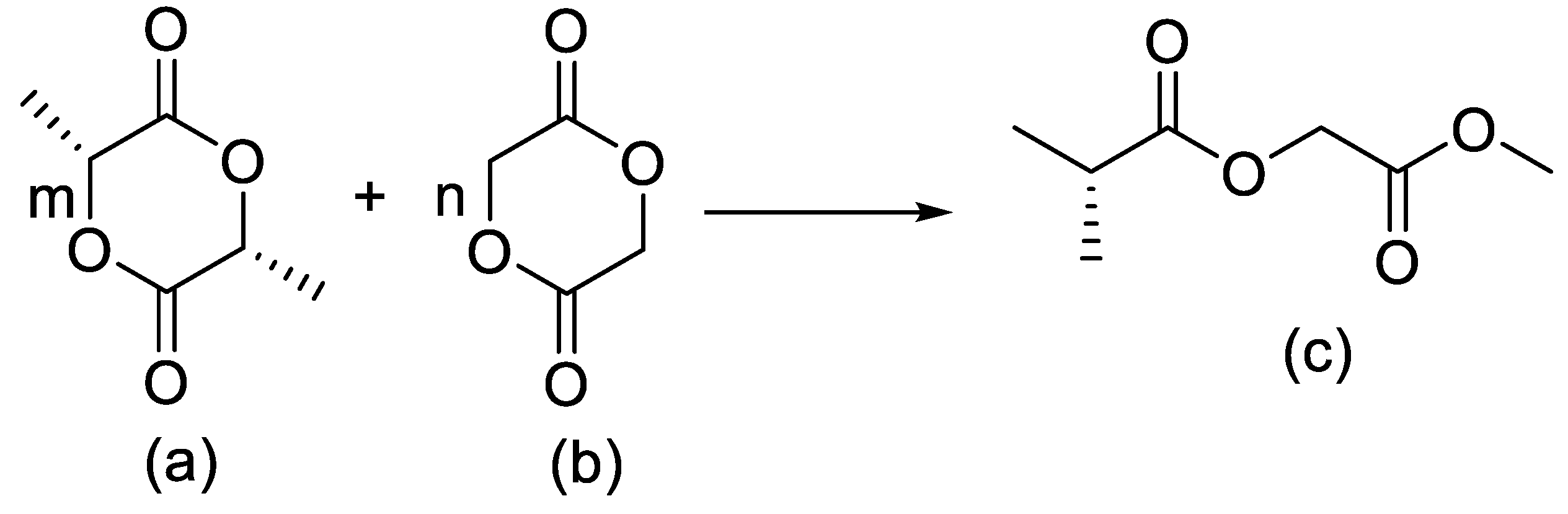

- Washington, M.A.; Balmert, S.C.; Fedorchak, M.V.; Little, S.R.; Watkins, S.C.; Meyer, T.Y. Monomer Sequence in PLGA Microparticles: Effects on Acidic Microclimates and In Vivo Inflammatory Response. Acta Biomater. 2017, 65, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zlomke, C.; Barth, M.; Mäder, K. Polymer Degradation Induced Drug Precipitation in PLGA Implants–Why Less Is Sometimes More. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2019, 139, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fredenberg, S.; Wahlgren, M.; Reslow, M.; Axelsson, A. The Mechanisms of Drug Release in Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid)-Based Drug Delivery Systems: A Review. Int. J. Pharm. 2011, 415, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Weert, M.; Hennink, W.E.; Jiskoot, W. Protein Instability in Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) Microparticles. Pharm. Res. 2000, 17, 1159–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, N.; Saeed, H.; Butt, M.S. Herbal-Infused PEI/PAA Coated Magnesium Stitches: A Drug Delivery System for Skin Regeneration and Controlled Release. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2025, 107829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

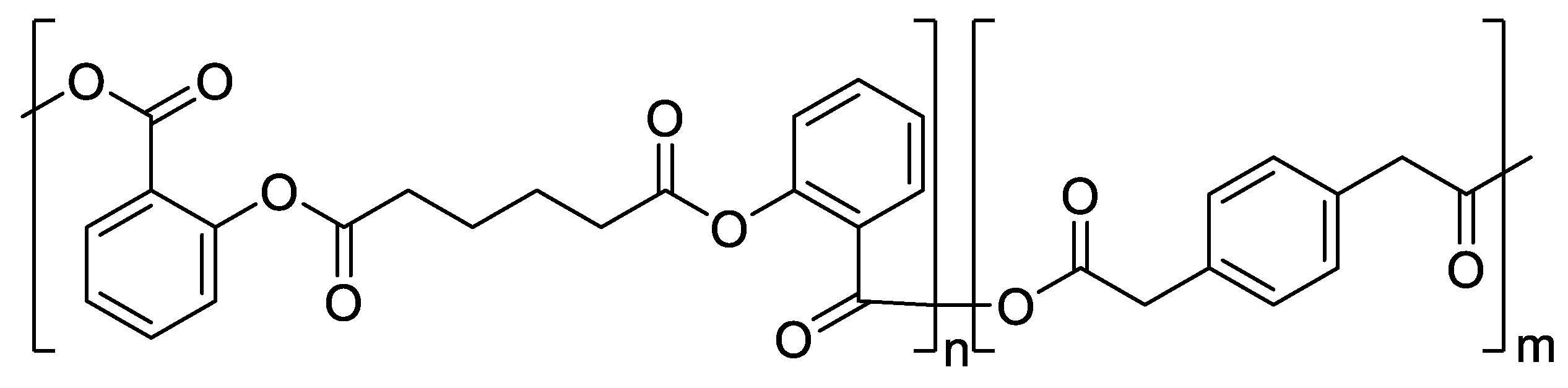

- Lima, M.; Nguyen, N.Q.; Safi, L.; Gill, T.; Song, S.; Dugger, T.; Uhrich, K.E. Tailored Dual Release of Retinol and Salicylic Acid from Salicylate-Based Poly(Anhydride-Ester) Microspheres with Tunable Degradation Profiles. SSRN Electron. J. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zeng, H.; Luo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wang, M.; Wu, C.; Hu, P. Recent Applications of PLGA in Drug Delivery Systems. Polymers 2024, 16, 2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, H.M.; Eid, S.A.; Eldeen, H.A.S.; Ebrahim, M.E.H. Oxidative Degradation Pathways of Carrot Carotenes and Their Protection via Chitosan–TPP Encapsulation. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2025, 12, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Feng, X.; Liu, F.; Wang, B.; Zhang, H.; Niu, X. The Pro-Inflammatory Response of Macrophages Regulated by Acid Degradation Products of Poly(lactide-co-glycolide) Nanoparticles. Eng. Life Sci. 2021, 21, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makadia, H.K.; Siegel, S.J. Poly Lactic-co-Glycolic Acid (PLGA) as Biodegradable Controlled Drug Delivery Carrier. Polymers 2011, 3, 1377–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millet, E.; O’Shea, J.P.; Griffin, B.T.; Dumont, C.; Jannin, V. Next Generation Capsules: Emerging Technologies in Capsule Fabrication and Targeted Oral Drug Delivery. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2025, 107277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

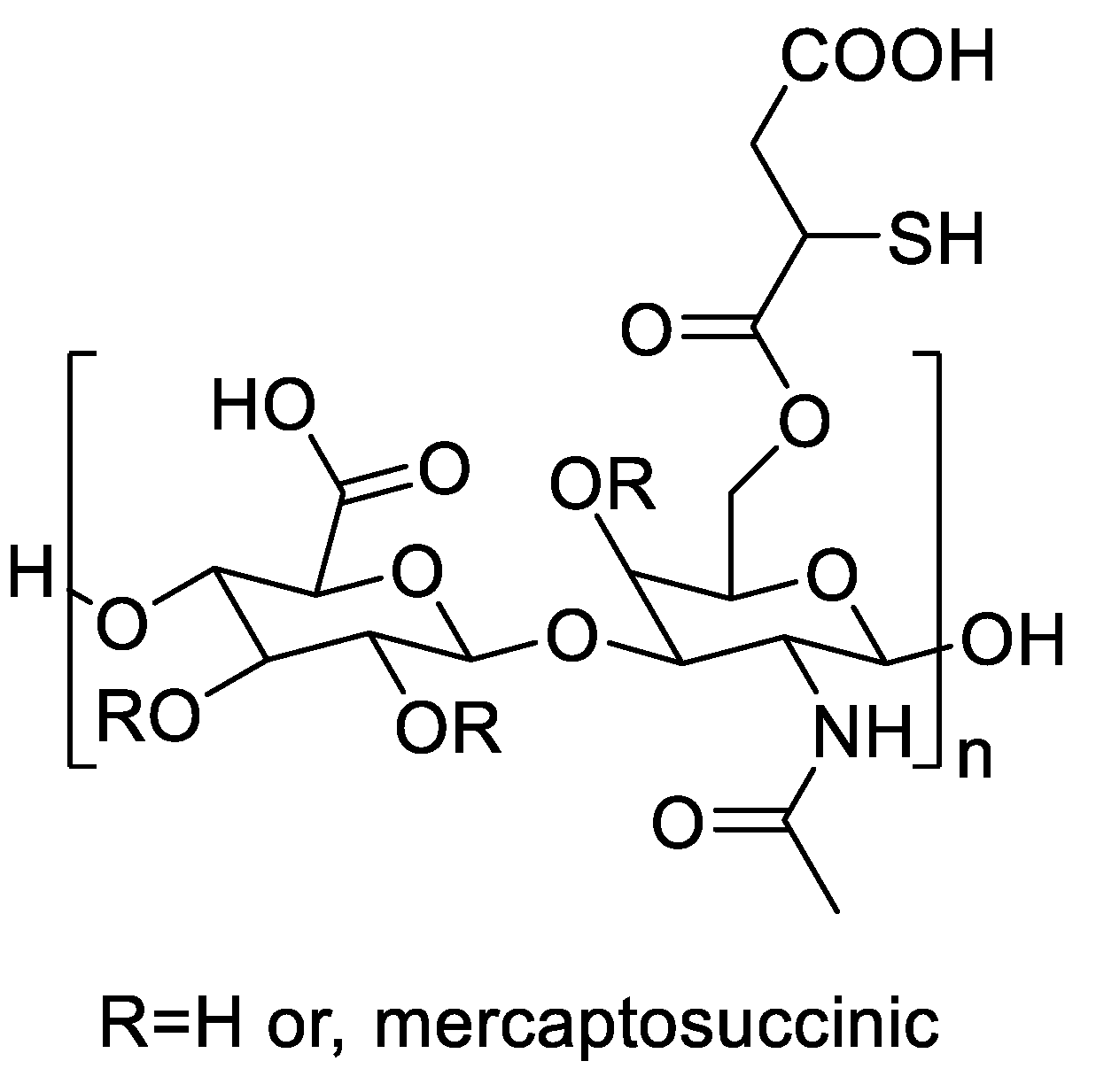

- Massani, M.B.; Meile, S.; Knoll, A.; Gintsburg, D.; Polidori, I.; Seybold, A.; Coraça-Huber, D.C.; Loessner, M.J.; Kali, G.; Schmelcher, M.; Zapotoczny, S.; Bernkop-Schnürch, A. Thiolated Hyaluronic Acid: A Gateway for Targeted Killing of Staphylococcus aureus on the Race for Surface Colonization. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2025, 202502890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, Y.; He, C.; Riviere, J.E.; Monteiro-Riviere, N.A.; Lin, Z. Meta-Analysis of Nanoparticle Delivery to Tumors Using a Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling and Simulation Approach. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 3075–3095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, L.S.L.; Stern, S.T.; Deal, A.M.; Kabanov, A.V.; Zamboni, W.C. A Reanalysis of Nanoparticle Tumor Delivery Using Classical Pharmacokinetic Metrics. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eaay9249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, S.; Tavares, A.J.; Dai, Q.; Ohta, S.; Audet, J.; Dvorak, H.F.; Chan, W.C.W. Analysis of Nanoparticle Delivery to Tumours. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 16014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, M.J.; Billingsley, M.M.; Haley, R.M.; Wechsler, M.E.; Peppas, N.A.; Langer, R. Engineering Precision Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2020, 20, 101–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Wilhelm, S.; Ding, D.; Syed, A.M.; Sindhwani, S.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.Y.; MacMillan, P.; Chan, W.C.W. Quantifying the Ligand-Coated Nanoparticle Delivery to Cancer Cells in Solid Tumors. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 8423–8435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhumagaliyeva, Sh.N.; Iminova, R.S.; Kairalapova, G.Zh.; Beysebekov, M.M.; Beysebekov, M.K.; Abilov, Zh.A. Composite Polymer-Clay Hydrogels Based on Bentonite Clay and Acrylates: Synthesis, Characterization and Swelling Capacity. Eurasian Chem.-Technol. J. 2017, 19, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baimyrza, P.A.; Iminova, R.S.; Kudaibergenova, B.M.; Kairalapova, G.Zh. Bionanocomposite Films Based on Chitosan with Bentonite Clay and Polyvinyl Alcohol. Eurasian Chem.-Technol. J. 2022, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhumagaliyeva, S.N.; Abdikarim, G.G.; Berikova, A.B.; Abilov, Z.A.; Koetz, J.; Kopbayeva, M.T. Study of the Mechanical Properties of Gelatin Films with Natural Compounds of Tamarix hispida. Eurasian Chem.-Technol. J. 2023, 25, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanzholkyzy, A.; Zhumagaliyeva, S.; Sultanova, N.; Abilov, Z.; Ongalbek, D.; Donbayeva, E.; Niyazbekova, A.; Mukazhanova, Z. Hydrogel Delivery Systems for Biological Active Substances: Properties and the Role of HPMC as a Carrier. Molecules 2025, 30, 1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafari, B.; Jalil, S.; Zaib, S.; Safarov, S.; Khalikova, M.; Khalikov, D.; Ospanov, M.; Yelibayeva, N.; Zhumagalieva, S.; Abilov, Z.A.; Turmukhanova, M.Z.; Kalugin, S.N.; Salman, G.A.; Ehlers, P.; Hameed, A.; Iqbal, J.; Langer, P. Synthesis of 2-Alkynyl- and 2-Amino-12H-benzothiazolo[2,3-b]quinazolin-12-ones and Their Inhibitory Potential against Monoamine Oxidase A and B. ChemistrySelect 2019, 4, 13760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhumagaliyeva, S.N.; Iminova, R.S.; Kairalapova, G.Z.; Kudaybergenova, B.M.; Abilov, Z.A. Sorption of Heavy Metal Ions by Composite Materials Based on Polycarboxylic Acids and Bentonite Clay. Eurasian Chem.-Technol. J. 2021, 23, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

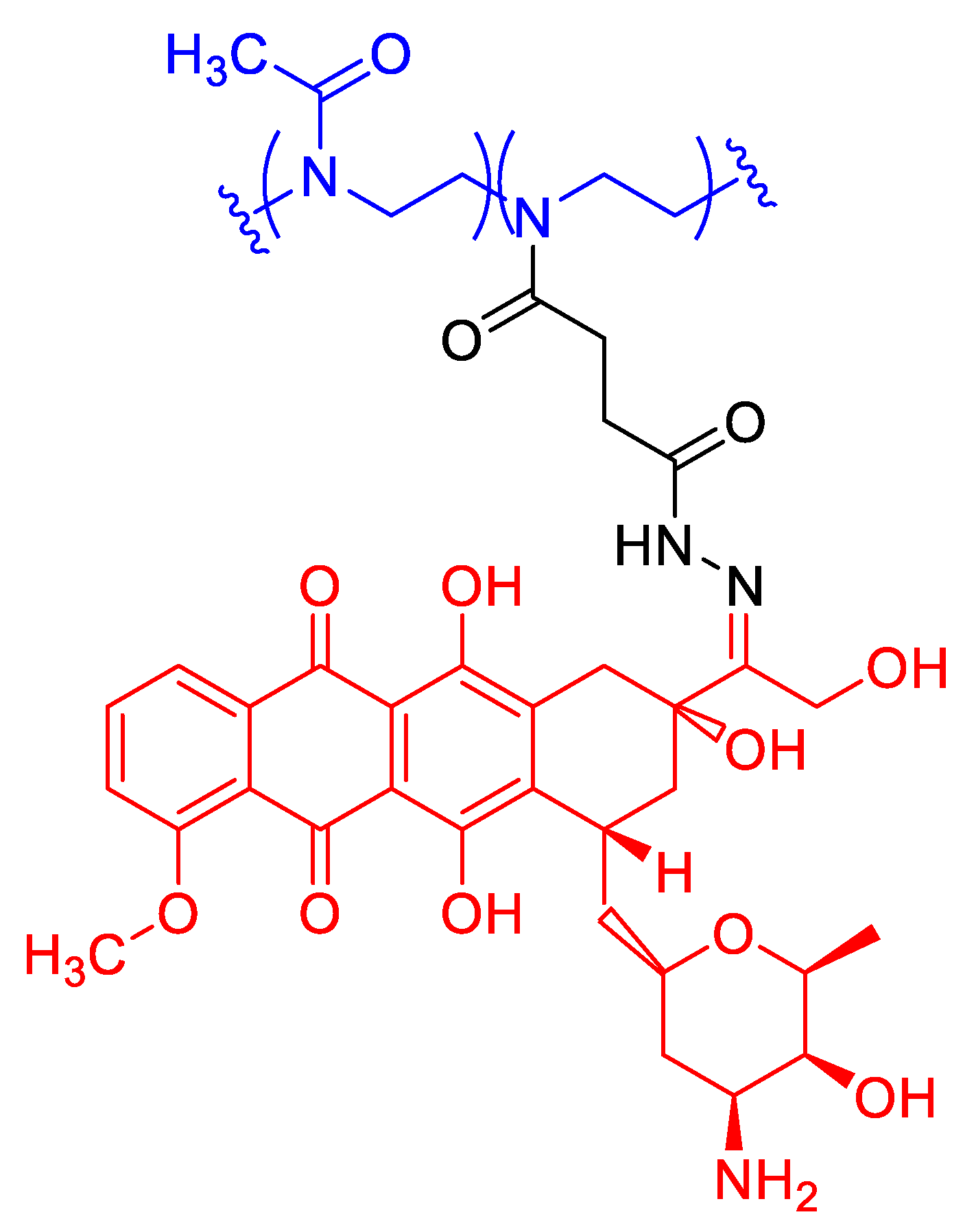

- Sedlacek, O.; Van Driessche, A.; Uvyn, A.; De Geest, B.G.; Hoogenboom, R. Poly(2-methyl-2-oxazoline) Conjugates with Doxorubicin: From Synthesis of High Drug Loading Water-Soluble Constructs to In Vitro Anti-Cancer Properties. J. Control. Release 2020, 326, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, X.; Aspinall, S.; Kaldybekov, D.B.; Buang, F.; Williams, A.C.; Khutoryanskiy, V.V. Synthesis and Evaluation of Methacrylated Poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline) as a Mucoadhesive Polymer for Nasal Drug Delivery. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2021, 3, 5882–5892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusina, A.; Nazim, T.; Cegłowski, M. Poly(2-oxazoline)s as Stimuli-Responsive Materials for Biomedical Applications: Recent Developments of Polish Scientists. Polymers 2022, 14, 4176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavikainen, J.; Dauletbekova, M.; Toleutay, G.; Kaliva, M.; Chatzinikolaidou, M.; Kudaibergenov, S.E.; Tenkovtsev, A.; Khutoryanskiy, V.V.; Vamvakaki, M.; Aseyev, V. Poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline) Grafted Gellan Gum for Potential Application in Transmucosal Drug Delivery. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2021, 32, 2770–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

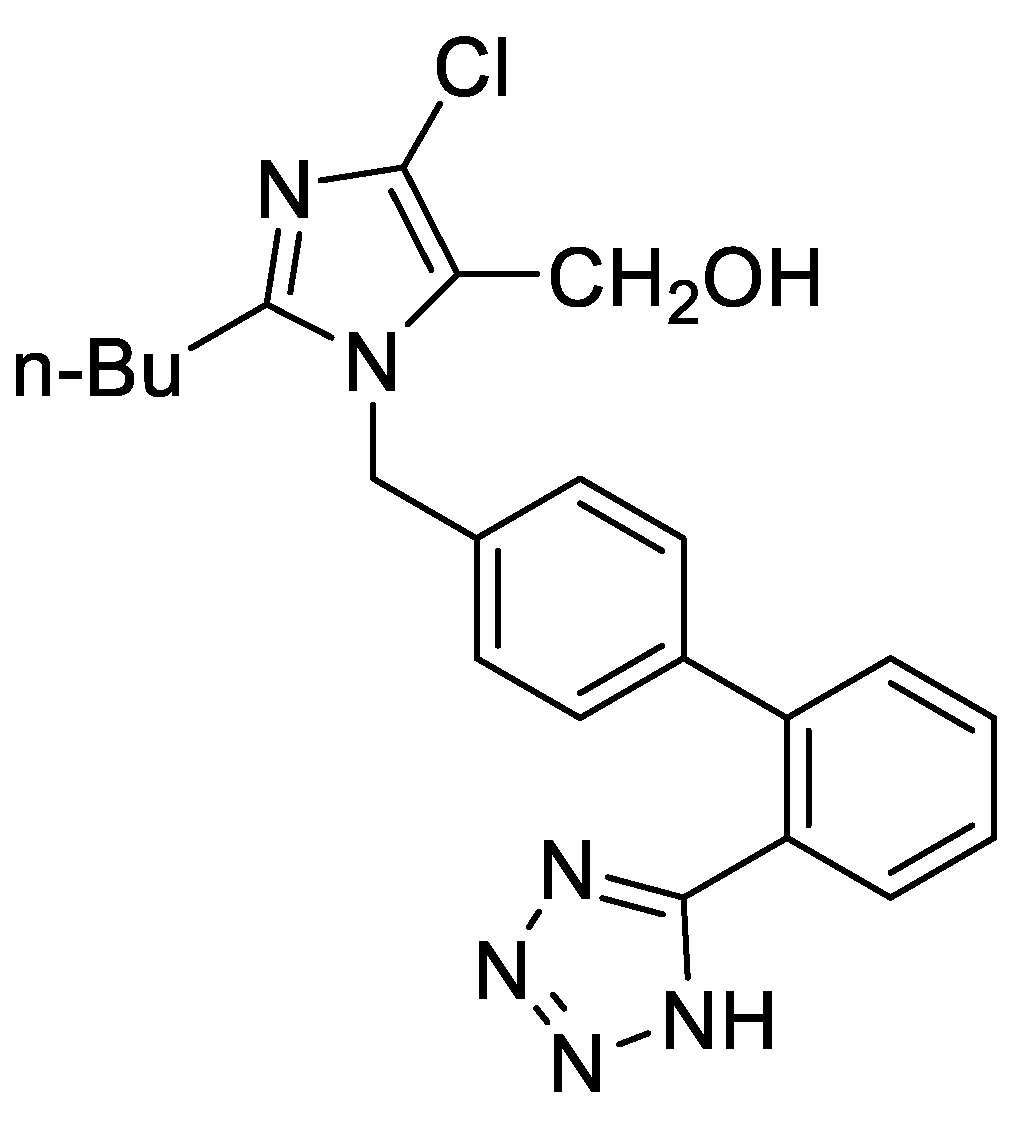

- Chroni, A.; Mavromoustakos, T.; Pispas, S. Poly(2-oxazoline)-Based Amphiphilic Gradient Copolymers as Nanocarriers for Losartan: Insights into Drug–Polymer Interactions. Macromol. 2021, 1, 177–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abilova, G.K.; Kaldybekov, D.B.; Irmukhametova, G.S.; Kazybayeva, D.S.; Iskakbayeva, Z.A.; Kudaibergenov, S.E.; Khutoryanskiy, V.V. Chitosan/Poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline) Films with Ciprofloxacin for Application in Vaginal Drug Delivery. Materials 2020, 13, 1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leiske, M.N.; Lai, M.; Amarasena, T.; Davis, T.P.; Thurecht, K.J.; Kent, S.J.; Kempe, K. Interactions of Core Cross-Linked Poly(2-oxazoline) and Poly(2-oxazine) Micelles with Immune Cells in Human Blood. Biomaterials 2021, 274, 120843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oleszko-Torbus, N.; Mendrek, B.; Wałach, W.; Fus-Kujawa, A.; Mitova, V.; Koseva, N.; Kowalczuk, A. Amino-Modified 2-Oxazoline Copolymers for Complexation with DNA. Polym. Chem. 2024, 15, 742–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkattan, N.; Alasmael, N.; Ladelta, V.; Khashab, N.M.; Hadjichristidis, N. Poly(2-oxazoline)-Based Core Cross-Linked Star Polymers: Synthesis and Drug Delivery Applications. Nanoscale Adv. 2023, 5, 2794–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiske, M.N.; Singha, R.; Jana, S.; De Geest, B.G.; Hoogenboom, R. Amidation of Methyl Ester-Functionalised Poly(2-oxazoline)s as a Powerful Tool to Create Dual pH- and Temperature-Responsive Polymers as Potential Drug Delivery Systems. Polym. Chem. 2023, 14, 2034–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terracciano, R.; Liu, Y.; Varanaraja, Z.; Godzina, M.; Yilmaz, G.; Van Hest, J.C.M.; Becer, C.R. Poly(2-oxazoline)-Based Thermoresponsive Stomatocytes. Biomacromolecules 2024, 25, 6050–6059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

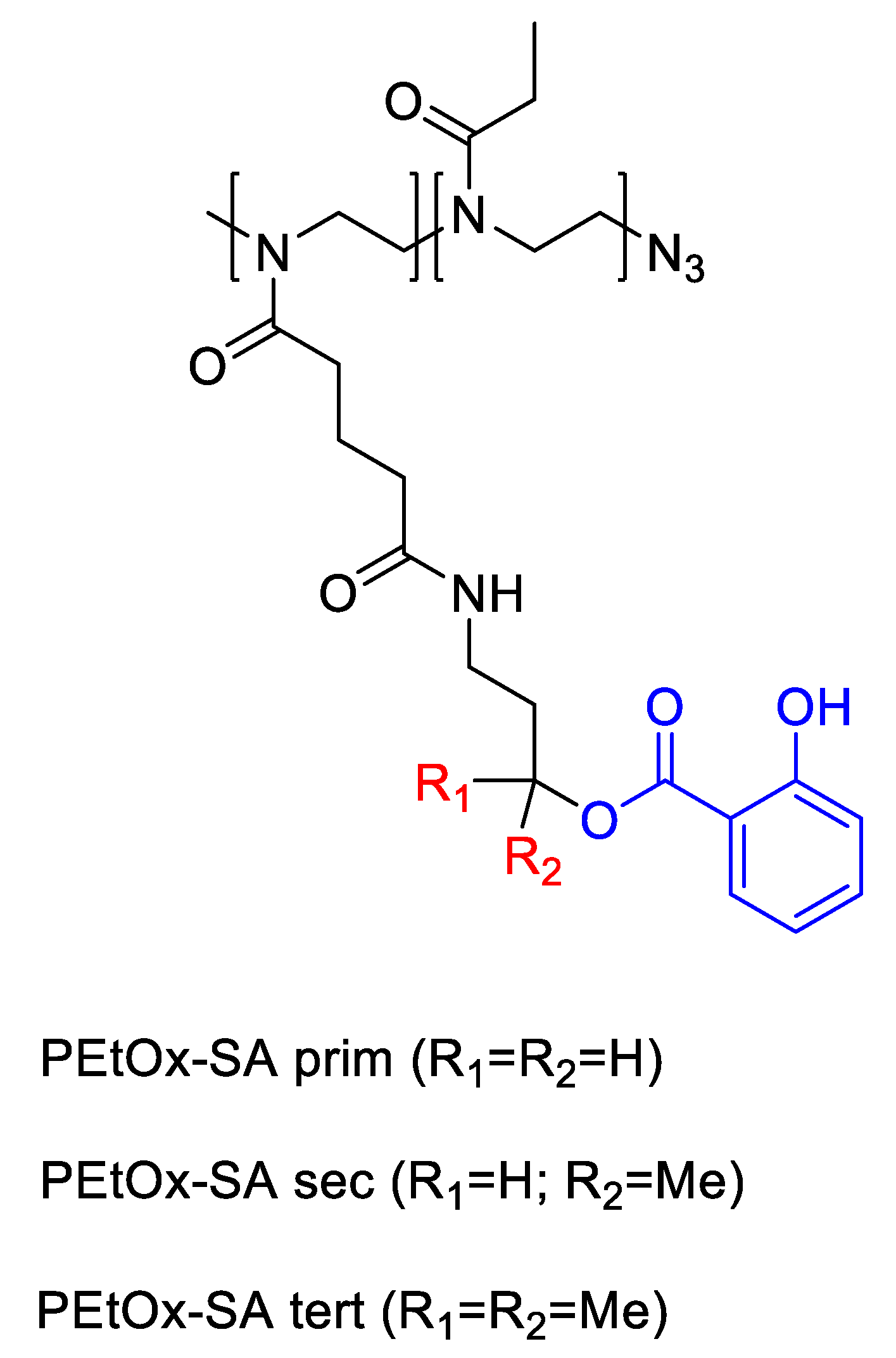

- Bernhard, Y.; Sedlacek, O.; Van Guyse, J.F.R.; Bender, J.; Zhong, Z.; De Geest, B.G.; Hoogenboom, R. Poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline) Conjugates with Salicylic Acid via Degradable Modular Ester Linkages. Biomacromolecules 2020, 21, 3207–3215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

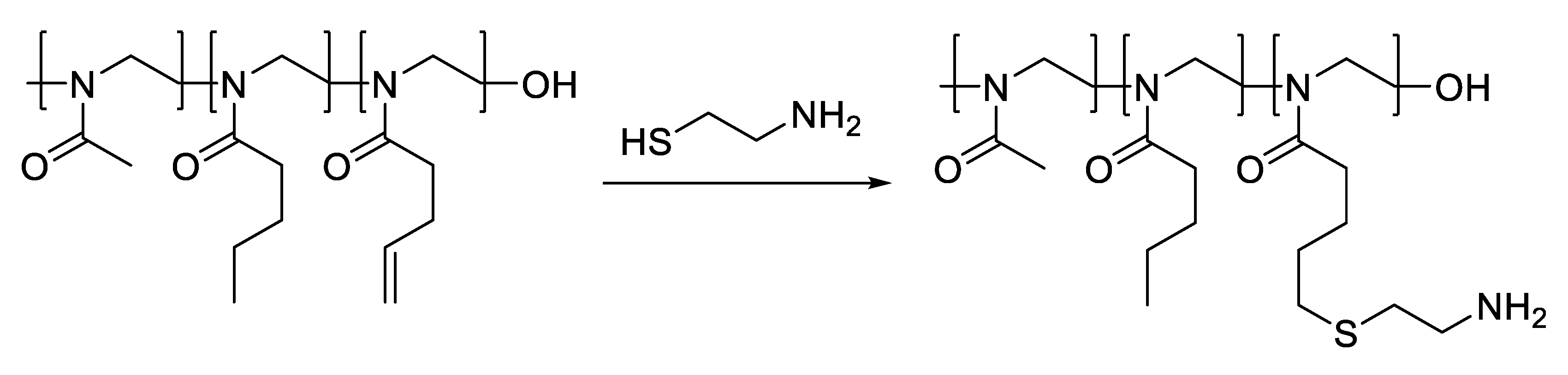

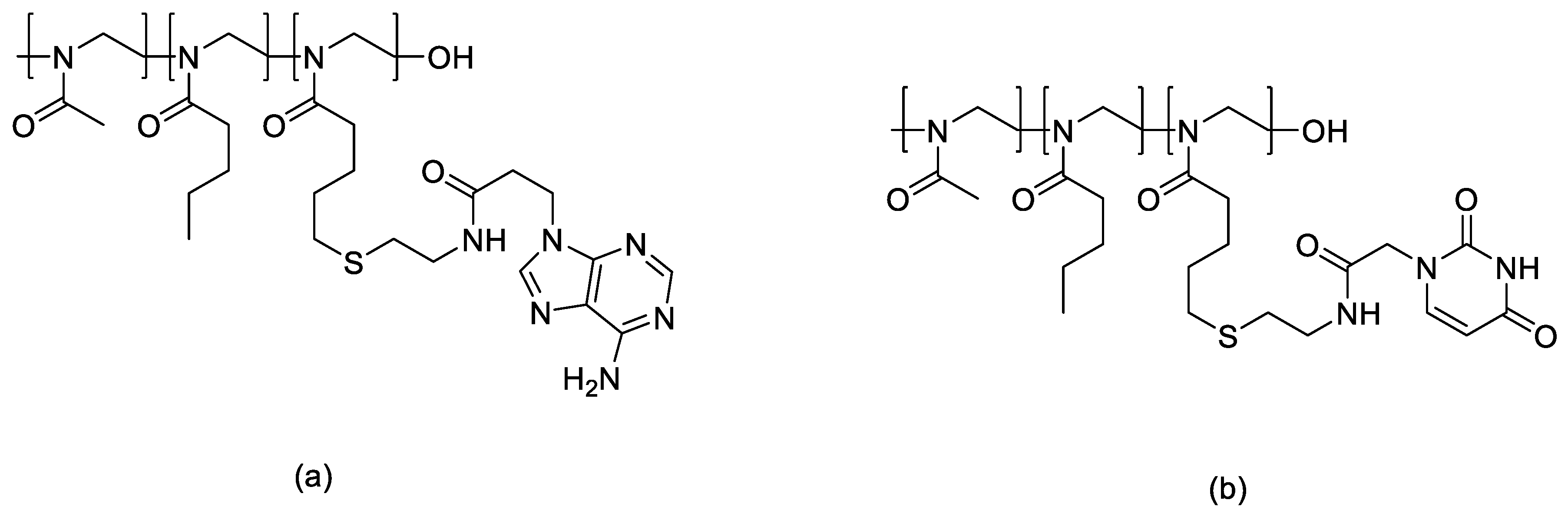

- Dong, S.; Ma, S.; Chen, H.; Tang, Z.; Song, W.; Deng, M. Nucleobase-Crosslinked Poly(2-oxazoline) Nanoparticles as Paclitaxel Carriers with Enhanced Stability and Ultra-High Drug Loading Capacity for Breast Cancer Therapy. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 17, 571–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedlacek, O.; Hoogenboom, R. Drug Delivery Systems Based on Poly(2-oxazoline)s and Poly(2-oxazine)s. Adv. Ther. 2019, 3, 1900168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Feng, S.; El-Kanayati, R.; Karnik, I.; Vemula, S.K.; Repka, M.A. Novel Development of Poly(2-ethyl-2-oxazoline)-Based Mucoadhesive Buccal Film for Poorly Water-Soluble Drug Delivery via Hot-Melt Extrusion. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2025, 114686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vossen, L.I.; Domínguez-Asenjo, B.; Gutiérrez-Corbo, C.; Pérez-Pertejo, M.Y.; Balaña-Fouce, R.; Reguera, R.M.; Calderón, M. Mannose-Decorated Dendritic Polyglycerol Nanocarriers Drive Antiparasitic Drugs to Leishmania infantum-Infected Macrophages. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tiwari, N.; Orellano, M.S.; Navarro, L.; Beiranvand, Z.; Adeli, M.; Calderón, M. Polyglycerol-Functionalized β-Cyclodextrins as Crosslinkers in Thermoresponsive Nanogels for Enhanced Dermal Penetration of Hydrophobic Drugs. Small 2024, 20, e202311166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Zhou, S.; Li, Y.; Parshad, B.; Li, W.; Haag, R. Novel Dendritic Polyglycerol-Conjugated Mesoporous Silica-Based Targeting Nanocarriers for Co-Delivery of Doxorubicin and Tariquidar to Overcome Multidrug Resistance in Breast Cancer Stem Cells. J. Control. Release 2020, 330, 1106–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schötz, S.; Griepe, A.K.; Goerisch, B.B.; Kortam, S.; Vainer, Y.S.; Dimde, M.; Koeppe, H.; Wedepohl, S.; Quaas, E.; Achazi, K.; Schroeder, A.; Haag, R. Esterase-Responsive Polyglycerol-Based Nanogels for Intracellular Drug Delivery in Rare Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zhong, Y.; Nie, C.; Pan, Y.; Adeli, M.; Haag, R. Co-Delivery of Doxorubicin and Chloroquine by Polyglycerol-Functionalized MoS₂ Nanosheets for Efficient Multidrug-Resistant Cancer Therapy. Macromol. Biosci. 2021, 21, e2100233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensminger, Y.; Rashmi, R.; Karimov, M.; Nölte, G.; Hafke, M.; Schmitt, A.; Díaz-Oviedo, D.; Köbberling, J.; Haag, R. Polyglycerol-Based Lipids: A Next-Generation Alternative to PEG in Lipid Nanoparticles for Advanced Drug Delivery Systems. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2025, e202500428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherri, M.; Ferraro, M.; Mohammadifar, E.; Quaas, E.; Achazi, K.; Ludwig, K.; Grötzinger, C.; Schirner, M.; Haag, R. Biodegradable Dendritic Polyglycerol Sulfate for the Delivery and Tumor Accumulation of Cytostatic Anticancer Drugs. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 7, 2569–2579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosravani, N.; Ahmadi, V.; Kakanejadifard, A.; Adeli, M. Thermoresponsive and Antibacterial Two-Dimensional Polyglycerol-Interlocked Poly(NIPAM) for Targeted Drug Delivery. J. Nanostruct. Chem. 2022, 14, 245–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bej, R.; Achazi, K.; Haag, R.; Ghosh, S. Polymersome Formation by Amphiphilic Polyglycerol-b-Polydisulfide-b-Polyglycerol and Glutathione-Triggered Intracellular Drug Delivery. Biomacromolecules 2020, 21, 3353–3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochenek, M.; Oleszko-Torbus, N.; Wałach, W.; Lipowska-Kur, D.; Dworak, A.; Utrata-Wesołek, A. Polyglycidol of linear or branched architecture immobilized on a solid support for biomedical applications. Polymer Reviews 2020, 60, 717–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, E.; Robson, A.J.; Crisp, A.R.; Cockshell, M.P.; Burzava, A.L.S.; Ganesan, R.; Robinson, N.; Al-Bataineh, S.; Nankivell, V.; Sandeman, L.; et al. Study of the structure of hyperbranched polyglycerol coatings and their anti-biofouling and anti-thrombotic applications. Advanced Healthcare Materials 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, P.; Thongrom, B.; Arora, S.; Haag, R. Polyglycerol-based biomedical matrix for immunomagnetic circulating tumor cell isolation and their expansion into tumor spheroids for drug screening. Advanced Healthcare Materials 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbina, S.; Gill, A.; Mathew, S.; Abbasi, U.; Kizhakkedathu, J.N. Polyglycerol-based macromolecular iron chelator adjuvants for antibiotics to treat drug-resistant bacteria. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2020, 12, 37834–37844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tully, M.; Dimde, M.; Weise, C.; Pouyan, P.; Licha, K.; Schirner, M.; Haag, R. Polyglycerol for half-life extension of proteins: Alternative to PEGylation? Biomacromolecules 2021, 22, 1406–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, E.; Öhlinger, K.; Meindl, C.; Corzo, C.; Lochmann, D.; Reyer, S.; Salar-Behzadi, S. In vitro toxicity screening of polyglycerol esters of fatty acids as excipients for pulmonary formulations. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology 2019, 386, 114833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Sun, H.; Giannino, J.; Wu, Y.; Cheng, C. Biodegradable zwitterionic polymers as PEG alternatives for drug delivery. Journal of Polymer Science 2024, 62, 2231–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Trital, A.; Shen, J.; Wang, L.; Chen, S. Zwitterionic polypeptide-based nanodrug augments pH-triggered tumor targeting via prolonging circulation time and accelerating cellular internalization. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 2020, 12, 46639–46652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, T.; Chu, X.; Cheng, J.; Liang, J.; Zhou, J.; Huo, M. Hypoxia-sensitive zwitterionic vehicle for tumor-specific drug delivery through antifouling-based stable biotransport alongside PDT-sensitized controlled release. Biomacromolecules 2021, 22, 2233–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhang, F.; Yu, G.; Wang, Z.; Jacobson, O.; Ma, Y.; Tian, R.; Deng, H.; Yang, W.; Chen, Z.; Chen, X. Zwitterionic-to-cationic charge conversion polyprodrug nanomedicine for enhanced drug delivery. Theranostics 2020, 10, 6629–6637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trital, A.; Xue, W.; Chen, S. Development of a negative-biased zwitterionic polypeptide-based nanodrug vehicle for pH-triggered cellular uptake and accelerated drug release. Langmuir 2020, 36, 7181–7189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Su, L.; Yang, G.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, M.; Jing, H.; Zhang, X.; Bayston, R.; Van der Mei, H.C.; Busscher, H.J.; Shi, L. Self-targeting of zwitterion-based platforms for nano-antimicrobials and nanocarriers. Journal of Materials Chemistry B 2022, 10, 2316–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, H.; Yan, L.; Zhang, R.; Lovell, J.F.; Wu, Y.; Cheng, C. A sulfobetaine zwitterionic polymer–drug conjugate for multivalent paclitaxel and gemcitabine co-delivery. Biomaterials Science 2021, 9, 5000–5010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perecin, C.J.; Sponchioni, M.; Auriemma, R.; Cerize, N.N.P.; Moscatelli, D.; Varanda, L.C. Magnetite nanoparticles coated with biodegradable zwitterionic polymers as multifunctional nanocomposites for drug delivery and cancer treatment. ACS Applied Nano Materials 2022, 5, 16706–16719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulou, E.; Tsimpolis, A.; Theodorakis, K.; Axypolitou, S.; Tsamesidis, I.; Kontonasaki, E.; Pavlidou, E.; Bikiaris, D.N. Biodegradable zwitterionic PLA-based nanoparticles: Design and evaluation for pH-responsive tumor-targeted drug delivery. Polymers 2025, 17, 2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, S.; Park, S.; Choi, D.; Hong, J. Efficient drug delivery carrier surface without unwanted adsorption using sulfobetaine zwitterion. Advanced Materials Interfaces 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Yan, R.; Hou, W.; Wang, H.; Tian, Y. A pH-responsive zwitterionic polyurethane prodrug as drug delivery system for enhanced cancer therapy. Molecules 2021, 26, 5274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biosca, A.; Cabanach, P.; Abdulkarim, M.; Gumbleton, M.; Gómez-Canela, C.; Ramírez, M.; Bouzón-Arnáiz, I.; Avalos-Padilla, Y.; Borros, S.; Fernàndez-Busquets, X. Zwitterionic self-assembled nanoparticles as carriers for Plasmodium targeting in malaria oral treatment. Journal of Controlled Release 2021, 331, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgilis, E.; Abdelghani, M.; Pille, J.; Aydinlioglu, E.; Van Hest, J.C.M.; Lecommandoux, S.; Garanger, E. Nanoparticles based on natural, engineered or synthetic proteins and polypeptides for drug delivery applications. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2020, 586, 119537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

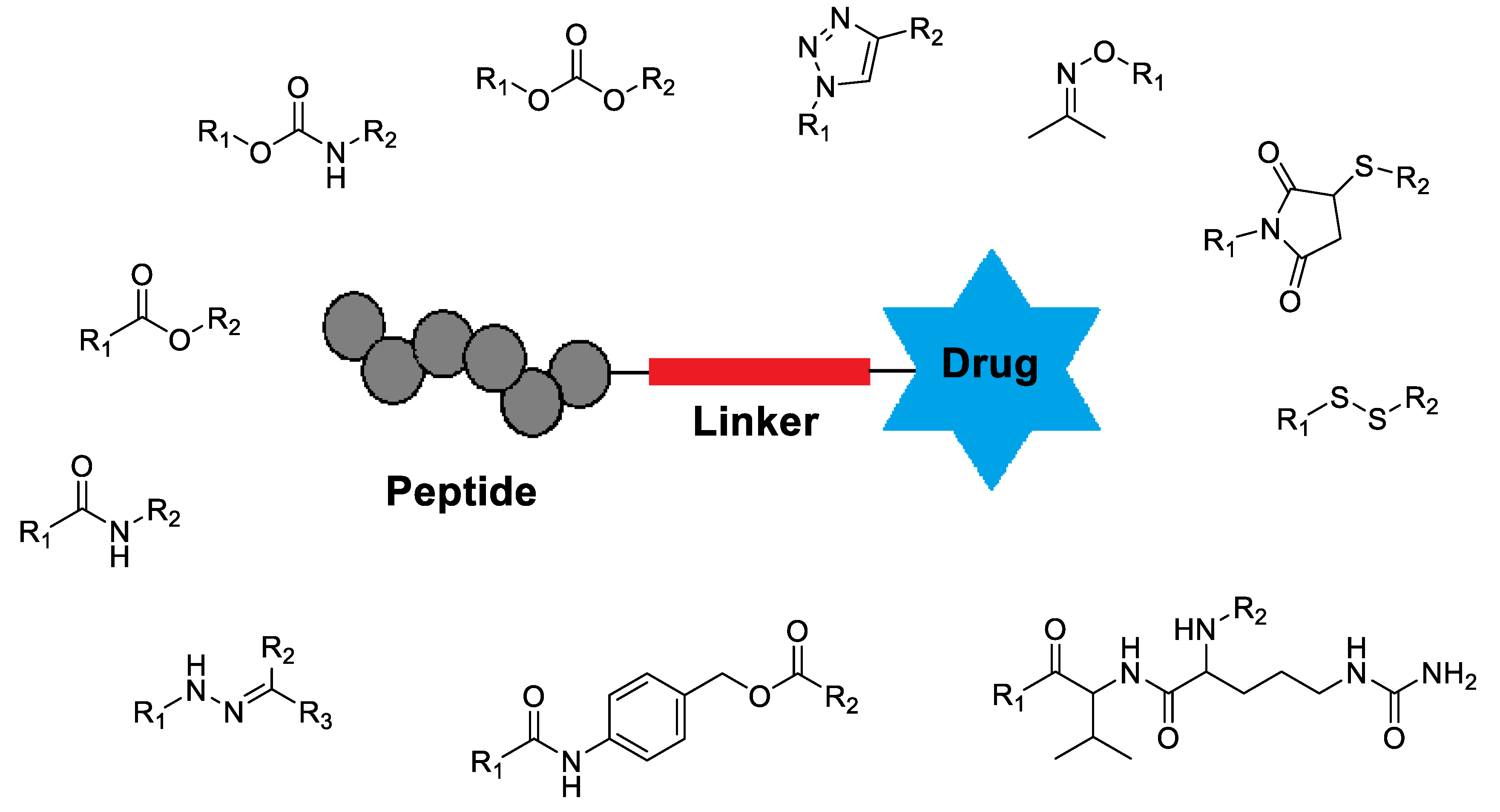

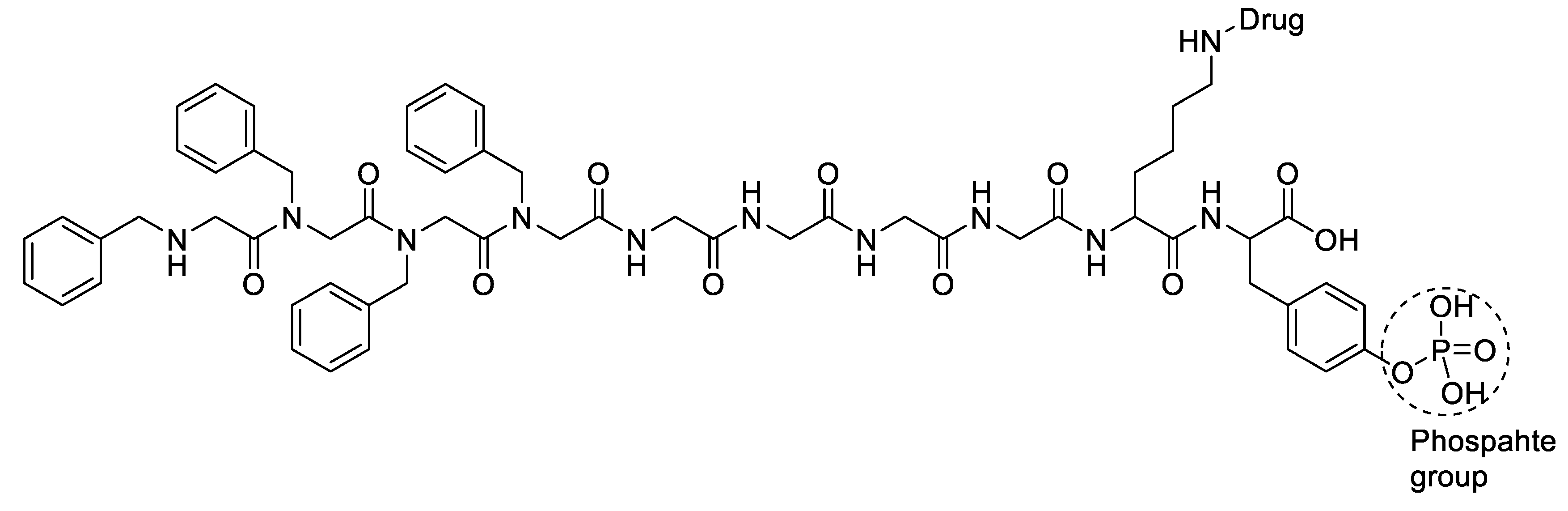

- Alas, M.; Saghaeidehkordi, A.; Kaur, K. Peptide–drug conjugates with different linkers for cancer therapy. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2020, 64, 216–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asai, D.; Kanamoto, T.; Takenaga, M.; Nakashima, H. In situ depot formation of anti-HIV fusion-inhibitor peptide in recombinant protein polymer hydrogel. Acta Biomaterialia 2017, 64, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Smith, Q.R.; Liu, X. Brain penetrating peptides and peptide–drug conjugates to overcome the blood–brain barrier and target CNS diseases. WIREs Nanomedicine and Nanobiotechnology 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.; Lee, S.; Park, S. iRGD peptide as a tumor-penetrating enhancer for tumor-targeted drug delivery. Polymers 2020, 12, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, E.R.; Peck, N.E.; Echeverri, J.D.; Gholizadeh, S.; Tang, W.; Woo, R.; Sharma, A.; Liu, W.; Rae, C.S.; Sallets, A.; et al. Discovery of a peptoid-based nanoparticle platform for therapeutic mRNA delivery via diverse library clustering and structural parametrization. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 22181–22193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, A.; Guan, X.; He, L.; Guan, X. Engineered elastin-like polypeptides: An efficient platform for enhanced cancer treatment. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coulter, S.M.; Pentlavalli, S.; An, Y.; Vora, L.K.; Cross, E.R.; Moore, J.V.; Sun, H.; Schweins, R.; McCarthy, H.O.; Laverty, G. In situ forming, enzyme-responsive peptoid–peptide hydrogels: An advanced long-acting injectable drug delivery system. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2024, 146, 21401–21416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, B.M.; Iegre, J.; O’Donovan, D.H.; Halvarsson, M.Ö.; Spring, D.R. Peptides as a platform for targeted therapeutics for cancer: Peptide–drug conjugates (PDCs). Chemical Society Reviews 2020, 50, 1480–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Luo, S.; Shen, J.; Luo, Y. Injectable pH-responsive polypeptide hydrogels for local delivery of doxorubicin. Nanoscale Advances 2024, 6, 6420–6432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, S.M.; Pentlavalli, S.; Vora, L.K.; An, Y.; Cross, E.R.; Peng, K.; McAulay, K.; Schweins, R.; Donnelly, R.F.; McCarthy, H.O.; Laverty, G. Enzyme-triggered L-α/D-peptide hydrogels as a long-acting injectable platform for systemic delivery of HIV/AIDS drugs. Advanced Healthcare Materials 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pentlavalli, S.; Coulter, S.M.; An, Y.; Cross, E.R.; Sun, H.; Moore, J.V.; Sabri, A.B.; Greer, B.; Vora, L.; McCarthy, H.O.; Laverty, G. D-peptide hydrogels as a long-acting multipurpose drug delivery platform for combined contraception and HIV prevention. Journal of Controlled Release 2025, 379, 30–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).