1. Introduction

Steroid-induced glaucoma (SIG) and ocular hypertension are well-documented complications of corticosteroid therapy, caused by increased resistance to aqueous humor outflow through the trabecular meshwork (TM) [

1,

2]. Underlying mechanisms include accumulation of extracellular matrix materials, cytoskeletal reorganization, inhibition of cellular phagocytic activity, and altered myocilin and fibronectin expression in TM cells [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Clinically significant intraocular pressure (IOP) elevation can be caused by steroid use of various durations and application routes, including topical, periorbital, intravitreal, or systemic corticosteroid administration. In particular, the sustained-release dexamethasone implant (Ozurdex

®, Allergan, Irvine, CA, USA) has been widely used for macular edema secondary to retinal vein occlusion, but 20–36% of patients experience transient or sustained IOP elevation requiring medical or surgical management [

5,

6].

Management of SIG is often challenging because affected patients may continue to require corticosteroid therapy for underlying ocular or systemic conditions. Conventional filtering surgery is usually effective in lowering IOP but is also carries significant risks, including postoperative hypotony, bleb-related infection, or fibrosis [

7]. Recently, minimally invasive glaucoma surgeries (MIGS) including stents, microhooks, ablation, and other approaches, have emerged as safer options that target physiologic aqueous outflow pathways with less surgical trauma [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Among these, trabecular bypass devices such as the iStent platform (iStent, iStent inject, iStent inject, iStent Infinite, Glaukos Corp., Aliso Viejo, CA, USA)[

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13] or Hydrus Microstent (Alcon, Fort Worth, TX, USA)[

8,

11] directly create microbypass channels through the TM into Schlemm’s canal, addressing the primary site of steroid-induced outflow resistance [

14].

Currently, there are few reports about the application of MIGS, including iStent [

12,

13], canaloplasty [

15], and gonioscopy-assisted transluminal trabeculotomy with or without goniotomy [

16,

17] or minimally invasive bleb surgery (MIBS) including XEN or Preserflo [

18,

19,

20] for SIG. Thus, we report a case of Ozurdex-associated SIG successfully treated using iStent infinite implantation, achieving long-term IOP control with sustained macular edema resolution despite continued intravitreal steroid injection.

2. Case Presentation

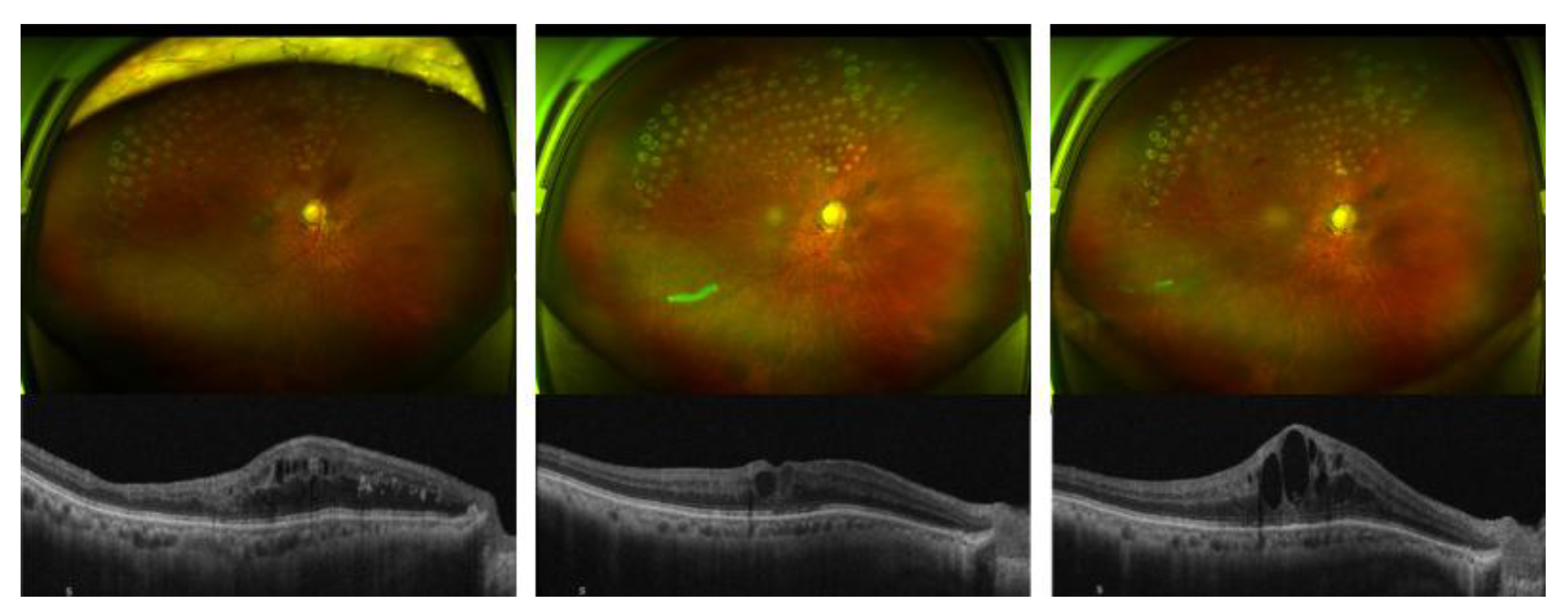

A 73-year-old man with a history of kidney transplantation and systemic immunosuppression (tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil) presented with persistent macular edema secondary to branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO) in his right eye. Despite multiple intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (anti-VEGF) injections, including bevacizumab and aflibercept, macular edema remained refractory. Consequently, intravitreal dexamethasone implant was administered. (

Figure 1).

Wide-field fundus photographs (upper panels) and corresponding spectral-domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) scans (lower panels) demonstrate the sequential changes in macular edema associated with branch retinal vein occlusion (BRVO). (left) Prior to intravitreal steroid injection, diffuse cystoid macular edema persisted despite multiple anti-VEGF treatments (bevacizumab and aflibercept). (center) One week after intravitreal dexamethasone implant (Ozurdex®), marked reduction of macular edema and improvement in foveal contour were observed. (right) At three months post-injection, recurrent cystoid changes and retinal thickening were noted, consistent with the waning effect of the dexamethasone implant.

Prior to receiving the Ozurdex implant, his IOP had remained well-controlled at

17 mmHg on topical dorzolamide/timolol fixed combination (DTFC, Cosopt

®, Santen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) twice daily due to ocular hypertension. Within several months after implantation, the patient developed progressive ocular hypertension, with IOP rising to 26 mmHg despite triple topical therapy with DTFC, brimonidine (Alphagan

®, Allergan, Abbvie company, Irvine, CA, USA), and bimatoprost (Lumigan

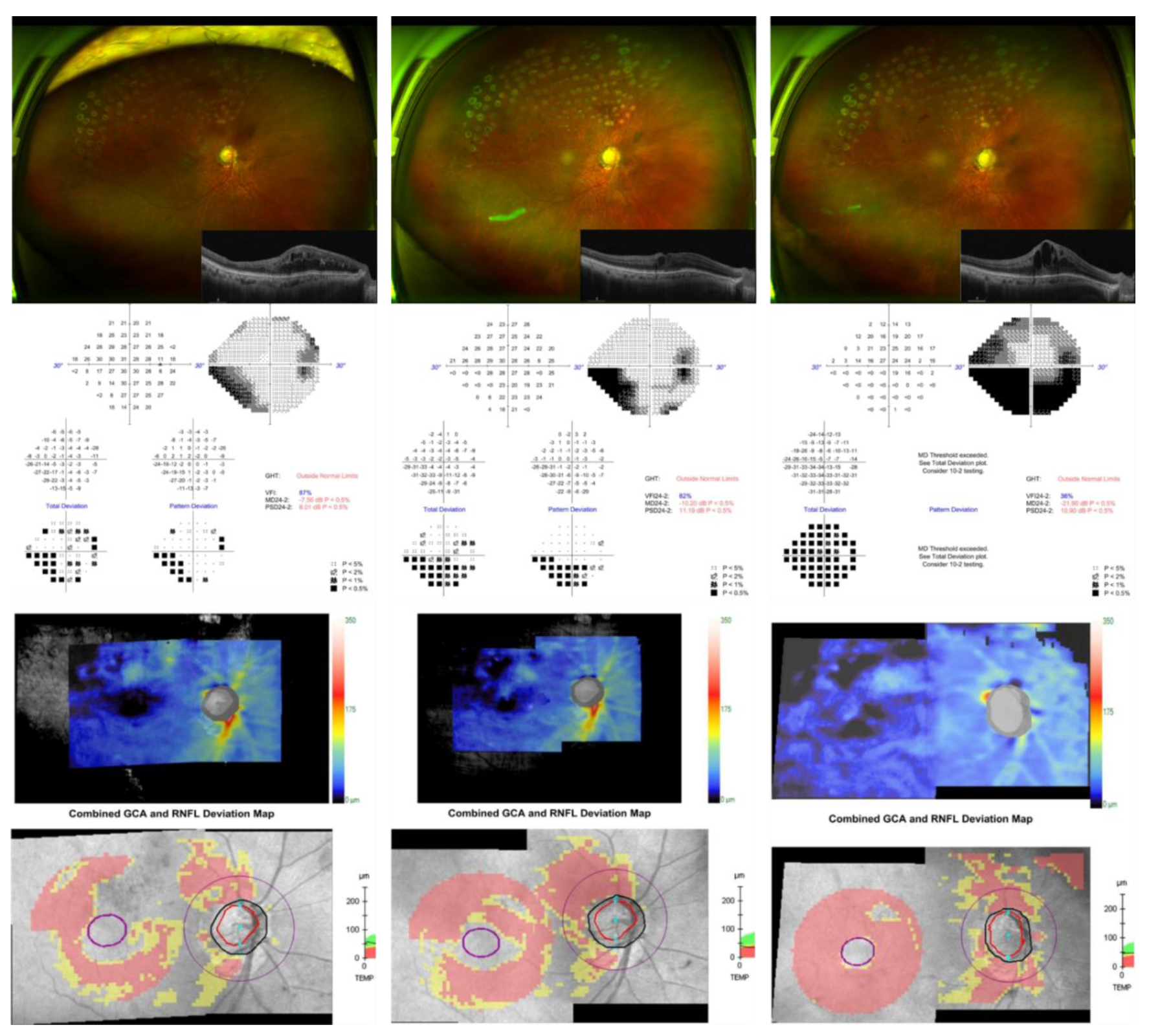

®, Abbvie company, Irvine, CA, USA). The IOP subsequently increased further to 34 mmHg, and Humphrey 24-2 visual field testing revealed rapid stepwise deterioration (mean deviation, −7.56 dB, −10.20 dB, and −21.91 dB; visual field index, 87%, 82%, and 36% respectively). Fundus photography demonstrated a hyperemic optic disc and diffuse laser scars from prior focal photocoagulation. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) revealed progressive cystoid macular edema and structural thinning of the retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) and ganglion cell analysis, particularly in the superior and inferior arcuate regions, consistent with rapid glaucomatous progression (

Figure 2).

The patient had also lost one of his upper limbs due to previous trauma, making the self-administration of multiple topical medications difficult. Given his fragile systemic condition and difficulty using frequent topical eye drops, conventional filtration surgery or tube surgery were considered highly risky, and therefore, we opted for a minimally invasive approach targeting the trabecular outflow pathways.

Slit lamp examination revealed fine corneal opacities, a properly placed posterior chamber intraocular lens, and absence of iris neovascularization. Gonioscopy revealed a wide-open angle with the absence of peripheral anterior synechiae or neovascularization of the angle.

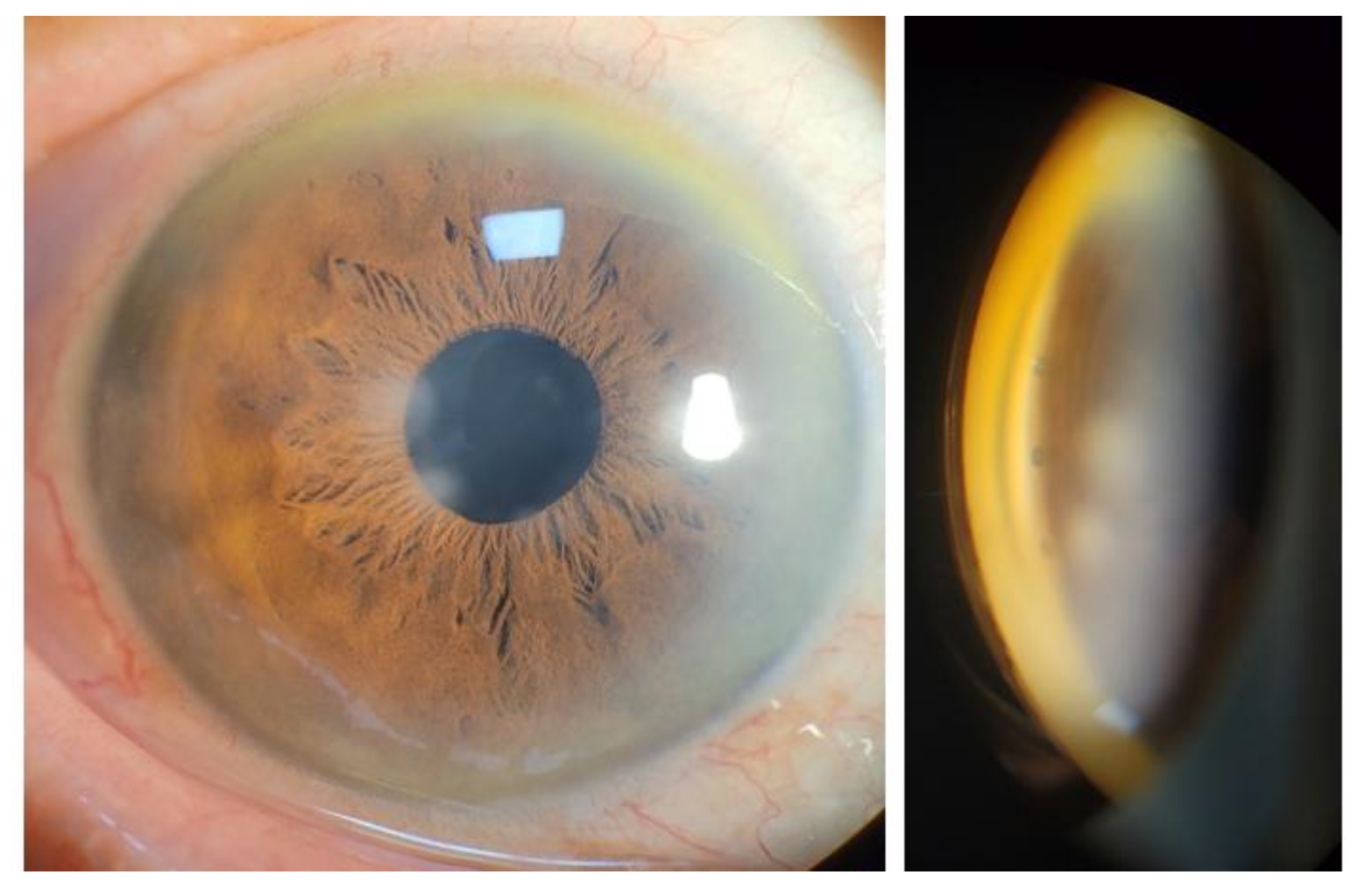

Based on these findings, the mechanism of IOP increase was assumed to be due to steroid-induced TM dysfunction with increased trabecular outflow resistance. To re-establish physiologic aqueous outflow via the Schlemm’s canal, iStent infinite implantation was planned. The procedure was performed under topical anesthesia using a clear corneal incision. Three trabecular micro-bypass stents were implanted sequentially into the nasal quadrant under direct gonioscopic visualization. Postoperatively, good positioning of all three stents within the pigmented TM without significant inflammation or hyphema were observed on slit lamp examination (

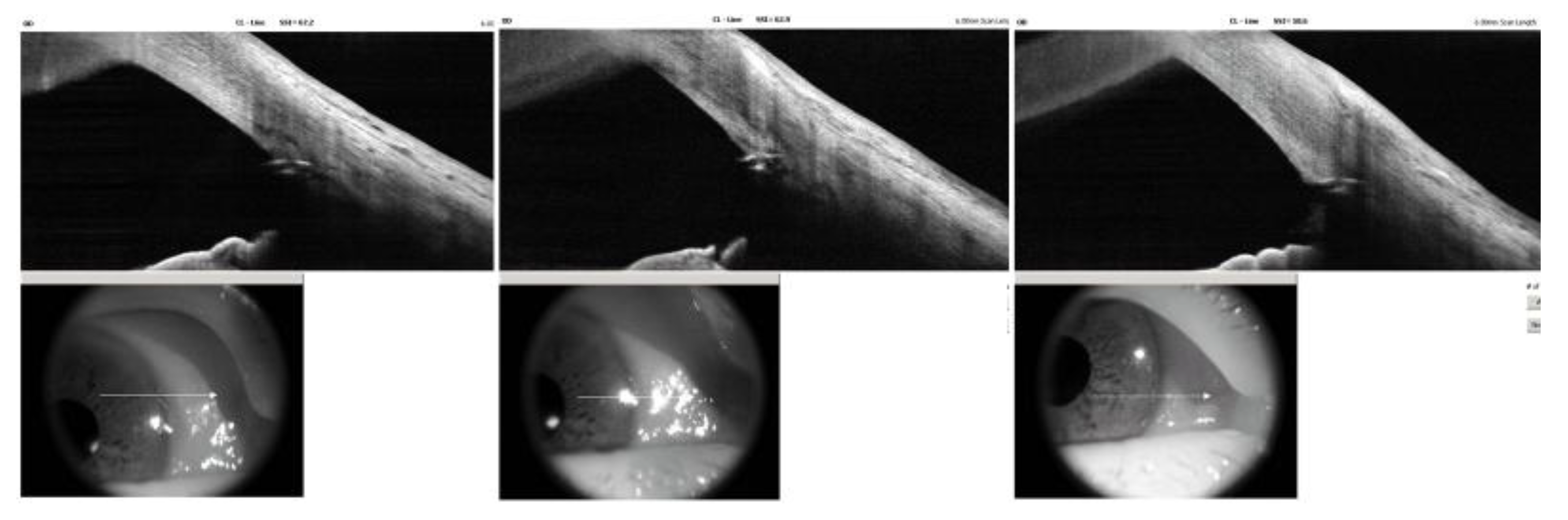

Figure 3). AS-OCT demonstrated similar findings except for one slightly over-implanted stent in the inferonasal side. (

Figure 4).

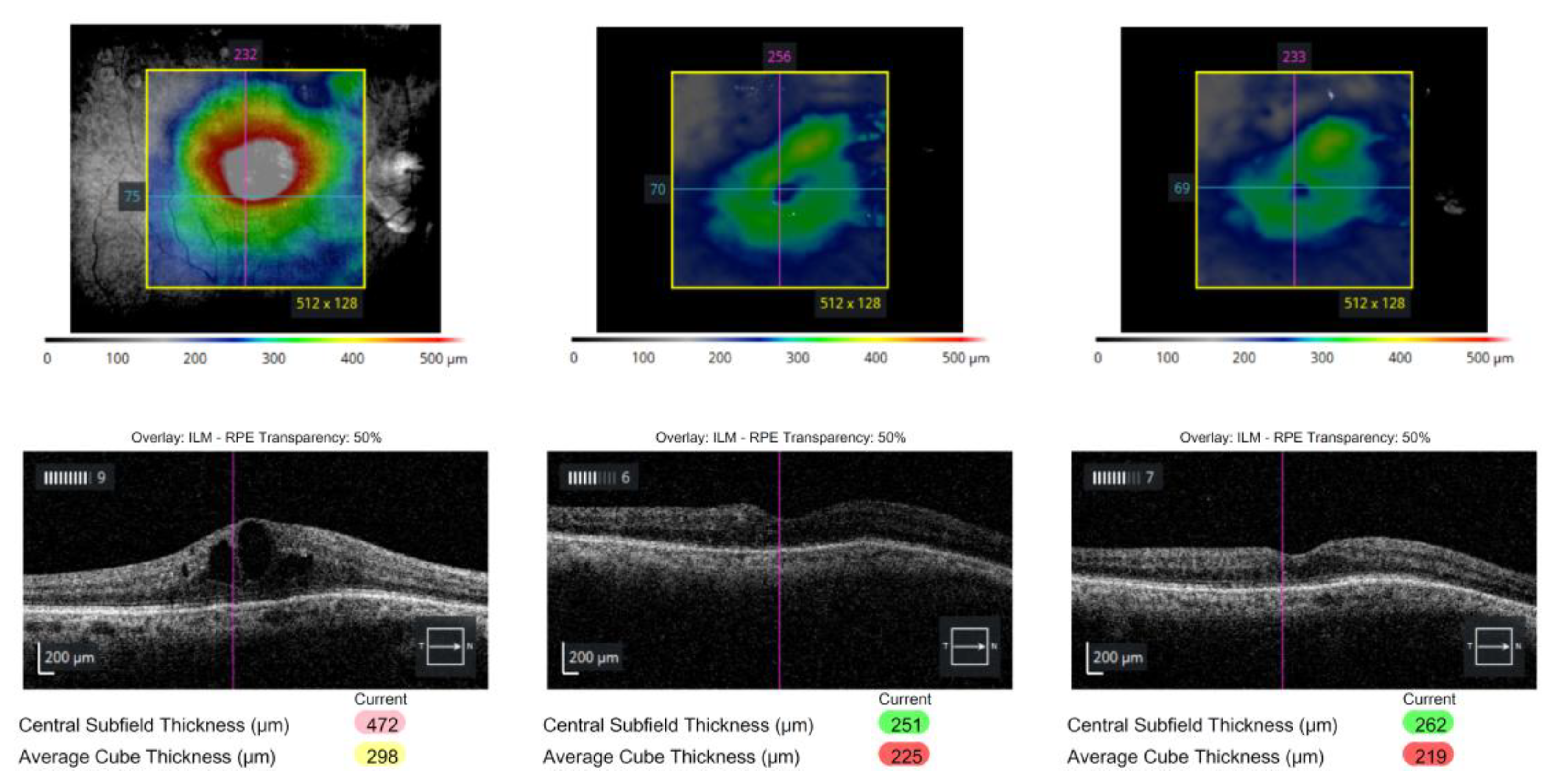

The postoperative course was uneventful. IOP decreased to 13 mmHg on postoperative day 7 while using DTFC and remained stable at 15 mmHg on the last follow-up at 12 months. There were neither intraoperative nor postoperative complications. Notably, the patient underwent two additional intravitreal Ozurdex injections for recurrent BRVO-related macular edema, which remained well controlled, as confirmed by serial macular OCT images showing resolution of cystoid changes and restoration of foveal contour. (

Figure 5)

To date, the patient has maintained excellent IOP control and visual stability for over one year following three trabecular micro-bypass stent surgeries, despite long-standing exposure to intravitreal corticosteroids. This case demonstrates that utilizing trabecular micro-bypass MIGS may be effective in restoring trabecular outflow and maintaining long-term pressure control in steroid-induced ocular hypertension or glaucoma, even when further steroid therapy is clinically necessary.

3. Discussion

In this case study, a patient exhibited marked IOP elevation with secondary steroid-induced glaucoma and underwent iStent infinite implantation along the nasal quadrant for IOP control. IOP improved from a maximum preoperative IOP of 34 on maximal medical treatment to 13 mmHg at postoperative 1 week. IOP control was maintained through 12 months (15 mmHg) on only one fixed combination eyedrop. Furthermore, additional Ozurdex implantations were continued with no recurrence of IOP elevation. These results suggest that multiple trabecular micro-bypass stents could achieve relatively long-term IOP control even in the presence of dexamethasone implant exposure.

Management of SIG is thought to be highly complex or sometimes challenging, particularly if cessation of steroids is difficult [

1,

2]. Usually, IOP rise most commonly occurs between three to six weeks and normalizes within two weeks after cessation of steroid therapy [

2]. A previous study [

21] compared intravitreal and periocular triamcinolone for macular edema from BRVO. Interestingly, the incidence of an IOP rise of 20 mm Hg or greater was significantly higher in the intravitreal group (33.3%), compared to the retrobulbar group (7.4%) [

21]. The problem is that most ocular pathologies that require intravitreal corticosteroids need multiple injections to maintain therapeutic effect, leading to increased risk of IOP spikes also [

1,

4]. In this context, sustained-release corticosteroid implants have an important role in the treatment of various ocular microvascular or inflammatory pathologies. Ozurdex is the shortest-acting and biodegradable implant, which releases dexamethasone at a controlled rate for up to 6 months [

5,

6]. Regarding the incidence of IOP elevation, about one-third of patients in each implant group (34.1% for the 0.35 mg group and 36.0% for the 0.7 mg group) had a clinically significant IOP increase, necessitating treatment in the MEAD study, a randomized clinical trial of varying doses of dexamethasone implant [

5].

Initial SIG management typically involves topical antiglaucoma medication, including aqueous beta-blockers, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, alpha-agonists, or prostaglandin analogues. However, in some cases, particularly those with severe steroid response or for those patients who require prolonged exposure, laser trabeculoplasty or surgical intervention is needed. Conventional filtration surgery or tube shunt implantation can achieve substantial IOP reduction but carry notable risks, including hypotony, bleb infections, and fibrosis [

7]. To prevent severe complications, previous studies reported on goniotomy, gonioscopy-assisted transluminal trabeculotomy, and canaloplasty [

15,

16,

17].

Recently, MIGS have emerged as promising alternatives to traditional filtration surgeries for selected patients with mild to moderate open-angle glaucoma. Angle-based MIGS procedures target physiological outflow pathways with faster recovery, less tissue disruption, and fewer severe postoperative complications. Major MIGS or micro-invasive bleb surgeries (MIBS) techniques could be classified into four categories: (1) trabecular bypass stents (iStent or Hydrus) [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13], (2) trabecular ablation or excision (Kahook Dual Blade, microhook, Trabectome, or bent angle needle goniotomy) [

10,

22], (3) Schlemm’s canal dilation (canaloplasty) [

15], and (4) subconjunctival microstents, MIBS (XEN, PreserFlo) [

18,

19,

20]. The selection of a specific MIGS/MIBS procedure should be guided by the presumed site of main outflow resistance and the patient’s clinical profile.

SIG is a form of secondary open-angle glaucoma, which aqueous outflow resistance increased [

1,

2,

4]. The primary main pathology is localized to the TM, where there are physical and mechanical changes in the microstructure of the TM, inhibition of TM phagocytosis, and depositions of various substances in the TM [

1,

2,

4]. Therefore, a direct angle-based MIGS procedure may be the better rational approach compared to other approaches. Rationales include: (1) canaloplasty or viscodilation may be less effective in SIG because Schlemm’s canal and the collector channels are often structurally intact, and TM resistance may be increased if corticosteroid therapy continues; (2) subconjunctival MIBS might be aggressive in such cases because Schlemm’s canal and distal channels remain structurally intact; and (3) trabecular ablation procedures may trigger additional fibrosis. In these contexts, we chose to use the iStent infinite stent, which creates permanent channels connecting the anterior chamber to Schlemm’s canal, thus restoring physiologic drainage independent of TM resistance [

8,

9]. The Hydrus implant was not available in South Korea at the time this patient was cared for. Also, the recently published INTEGRITY Study— a randomized, double-masked, multicenter, 24-month study— reported a statistically significant greater proportion of eyes achieving unmedicated mean diurnal IOP reduction ≥ 20% from baseline in eyes with no surgical complications in the iStent infinite group compared to the Hydrus group [

8].

The favorable result in our case may be attributed to the additive effect of three trabecular micro-bypass stents, which provides access to up to 240° of Schlemm’s canal. The iStent infinite composed of three heparin-coated titanium stents, allowing broader aqueous access [

8]. This might be especially beneficial in eyes with localized or segmental outflow obstruction, such as those seen in steroid-induced TM fibrosis or high TM resistance conditions.

In a similar manner, Louca and Wechner reported that two second-generation iStent inject devices may have prevented SIG by creating a trabecular bypass pathway, serving as a long-term, multidirectional safeguard that maintained aqueous humor outflow in a patient with Behçet disease during 4 years of follow-up [

13]. Buchacra et al. also reported four SIG cases treated with a first-generation iStent, with IOP decreasing over 12 months of follow-up (21–30 mmHg before iStent implantation vs. 17–20 mmHg at postoperative 12-month afterward) [

23].

While this single case cannot establish definitive efficacy, it raises the potential for angle-based MIGS to be an effective,safe, and physiologically compatible treatment for ocular hypertension in SIG. Future studies with larger cohorts receiving MIGS for SIG are warranted to confirm long-term safety, durability of pressure reduction, long-term compatibility with intravitreal steroid implants, and utility of AS-OCT for postoperative follow-up.

4. Conclusions

This case demonstrates successful long-term control of SIG with the iStent infinite trabecular micro-bypass system in a patient requiring continued intravitreal corticosteroid injection for macular edema. The favorable outcome suggests that trabecular bypass MIGS can effectively restore aqueous outflow in steroid-related trabecular dysfunction while minimizing surgical risk in patients who are elderly or who are compromised due to systemic co-morbidities.

To our knowledge, this is the first report of SIG managed with three trabecular micro-bypass stents (iStent infinite), achieving sustained IOP control and stable macular outcomes over 12 months of follow-up.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, SH.Lim. and KH. Lee, J. Seo; methodology, SH. Lim, J. Seo. LJ Katz; investigation, SH. Lim and KH. Lee, AS Huang, LJ Katz; resources, SH. Lim and KH.Lee.; data curation, SH.Lim.; writing—original draft preparation, SH.Lim. and KH.Lee.; writing—review and editing, SH.L. KH Lee, J Seo, AS Huang, LJ Katz; visualization, SH. Lim; supervision, SH.Lim. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Funding for this work came from National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD (Grant Numbers R01EY030501 [ASH]; Research to Prevent Blindness / David L. Epstein Career Advancement Award in Glaucoma Research sponsored by Alcon [AH], American Glaucoma Society Mid-Career Physician Research Grant [AH]; and an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness (New York, NY) [UCSD].

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Daegu Veterans Hospital (2025-35 and Dec 1 2025).” for studies involving humans.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author (Su-Ho Lim).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Alice Chu PhD, MPH, MBA for editing and reviewing this manuscript for English language.

Conflicts of Interest

KH Lee, J Seo, SH Lim declare no conflicts of interest. L Jay Katz: Glaukos: employee (chief medical officer), salary, stock options; Olleyes: stock options; Mati Pharmaceuticals: stock; Amorphex: stock. AS Huang: Allergan (Consultant), Amydis (Consultant), Celanese (Consultant), Diagnosys (Funding), Equinox (Consultant), Glaukos (Consultant, Funding), Heidelberg Engineering (Funding), QLARIS (Consultant), Santen (Consultant), Spinogenix (Consultant), and Topcon (Consultant).

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IOP |

Intraocular pressure |

| MIGS |

Minimally invasive glaucoma surgery |

| MIBS |

Minimally invasive bleb surgery |

| TM |

Trabecular meshwork |

| DTFC |

Dorzolamide-Timolol Fixed Combination |

| BRVO |

Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion |

| OCT |

Optical coherence tomography |

| AS-OCT |

Anterior segment optical coherence tomography |

| RNFL |

Retinal nerve fiber layer |

References

- Razeghinejad, M.R.; Katz, L.J. Steroid-induced iatrogenic glaucoma. Ophthalmic Res 2012, 47, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinreb, R.N.; Polansky, J.R.; Kramer, S.G.; Baxter, J.D. Acute effects of dexamethasone on intraocular pressure in glaucoma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1985, 26, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lu, R.; Kolarzyk, A.M.; Stamer, W.D.; Lee, E. Human ocular fluid outflow on-chip reveals trabecular meshwork-mediated Schlemm’s canal endothelial dysfunction in steroid-induced glaucoma. Nat Cardiovasc Res 2025, 4, 1066–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, P.D.; Kodati, B.; Clark, A.F. Role of Glucocorticoids and Glucocorticoid Receptors in Glaucoma Pathogenesis. Cells 2023, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, D.S.; Yoon, Y.H.; Belfort, R., Jr.; Bandello, F.; Maturi, R.K.; Augustin, A.J.; Li, X.Y.; Cui, H.; Hashad, Y.; Whitcup, S.M.; et al. Three-year, randomized, sham-controlled trial of dexamethasone intravitreal implant in patients with diabetic macular edema. Ophthalmology 2014, 121, 1904–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Chen, Y.; Fu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Ji, L.; Qiu, Y.; Li, S. The relationship between the intraocular position of dexamethasone intravitreal implant and post-injection intraocular pressure elevation. Frontiers in Medicine 2025, 12, 1582422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gedde, S.J.; Herndon, L.W.; Brandt, J.D.; Budenz, D.L.; Feuer, W.J.; Schiffman, J.C.; Tube Versus Trabeculectomy Study, G. Postoperative complications in the Tube Versus Trabeculectomy (TVT) study during five years of follow-up. Am J Ophthalmol 2012, 153, 804–814 e801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.I.K.; Berdahl, J.P.; Yadgarov, A.; Reiss, G.R.; Sarkisian, S.R., Jr.; Gagne, S.; Robles, M.; Voskanyan, L.A.; Sadruddin, O.; Parizadeh, D.; et al. Six-Month Outcomes from a Prospective, Randomized Study of iStent infinite Versus Hydrus in Open-Angle Glaucoma: The INTEGRITY Study. Ophthalmol Ther 2025, 14, 1005–1024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Rho, S.; Lim, S.H. Five-Year Outcomes of Single Trabecular Microbypass Stent (iStent((R))) Implantation with Phacoemulsification in Korean Patients. Ophthalmol Ther 2023, 12, 3281–3294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, S.; Tanito, M.; Shoji, N.; Yokoyama, Y.; Kameda, T.; Shoji, T.; Mizoue, S.; Saito, Y.; Ishida, K.; Ueda, T.; et al. Noninferiority of Microhook to Trabectome: Trabectome versus Ab Interno Microhook Trabeculotomy Comparative Study (Tram Trac Study). Ophthalmol Glaucoma 2022, 5, 452–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, J.C.K.; Clement, C.; Healey, P.; Lim, R.; White, A.; Yuen, J.; Agar, A.; Lawlor, M. Long-term comparative outcomes of Hydrus versus iStent inject microinvasive glaucoma surgery implants combined with cataract surgery. Br J Ophthalmol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guemes-Villahoz, N.; Garcia-Feijoo, J.; Martinez-de-la-Casa, J.M.; Torres-Imaz, R.; Donate-Lopez, J. Trabecular microbypass stent to treat ocular hypertension after intravitreal injection of a dexamethasone implant. J Fr Ophtalmol 2021, 44, e591–e594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louca, M.; Wechsler, D.Z. Protection from Steroid-Induced Glaucoma via iStent Inject in a Patient with Behcet’s Disease. Ophthalmol Glaucoma 2025, 8, 323–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hohberger, B.; Haug, M.; Bergua, A.; Lammer, R. [MIGS-off-label option for treatment-refractory steroid-induced ocular hypertension]. Ophthalmologe 2020, 117, 62–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brusini, P.; Tosoni, C.; Zeppieri, M. Canaloplasty in Corticosteroid-Induced Glaucoma. Preliminary Results. J Clin Med 2018, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.I.; Purgert, R.; Eisengart, J. Gonioscopy-Assisted Transluminal Trabeculotomy and Goniotomy, With or Without Concomitant Cataract Extraction, in Steroid-Induced and Uveitic Glaucoma: 24-Month Outcomes. J Glaucoma 2023, 32, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucgul, R.K.; Olgun, A.O.; Akdeniz, Z.B.; Inan, P.; Aktas, Z.; Ucgul, A.Y. Gonioscopy-assisted transluminal trabeculotomy for intractable ocular hypertension after repeated intravitreal dexamethasone implant injections. Int Ophthalmol 2025, 45, 325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezkallah, A.; Mathis, T.; Denis, P.; Kodjikian, L. XEN Gel Stent to Treat Intraocular Hypertension After Dexamethasone-Implant Intravitreal Injections: 5 Cases. J Glaucoma 2019, 28, e5–e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.Y.; Md Din, N.; Mohd Khialdin, S.; Wan Abdul Halim, W.H.; Tang, S.F. Ab-Externo Implantation of XEN Gel Stent for Refractory Steroid-Induced Glaucoma After Lamellar Keratoplasty. Cureus 2021, 13, e13320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourauel, L.; Petrak, M.; Holz, F.G.; Mercieca, K.; Weber, C. Short-Term Safety and Efficacy of PreserFlo Microshunt in Patients with Refractory Intraocular Pressure Elevation After Dexamethasone Implant Intravitreal Injection. J Clin Med 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, K.; Hayashi, H. Intravitreal versus retrobulbar injections of triamcinolone for macular edema associated with branch retinal vein occlusion. Am J Ophthalmol 2005, 139, 972–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, R.; Taravella, M.; Pantcheva, M.B. Kahook Dual Blade goniotomy in post penetrating keratoplasty steroid-induced ocular hypertension. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep 2020, 19, 100826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchacra, O.; Duch, S.; Milla, E.; Stirbu, O. One-year analysis of the iStent trabecular microbypass in secondary glaucoma. Clin Ophthalmol 2011, 5, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).