Submitted:

16 January 2026

Posted:

20 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Supplies

2.2. Stock E-Liquids

2.3. Saliva Preparation

2.4. Bacterial Strains and Growth Conditions

2.5. Preparation of Commensal Supernatants

2.6. Growth Curves of P. gingivalis with E-Liquids and Oral Commensal Supernatants

2.6.1. P. gingivalis Planktonic Growth

2.6.2. P. gingivalis CFU Quantification at 24 Hours of Planktonic Growth

2.7. Quantification of Multispecies Biofilms Exposed to E-Liquids

2.7.1. Crystal Violet

2.7.2. qPCR

2.7.3. Biofilm Sonication for Bacterial Dispersal and Subsequent CFU Counting

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

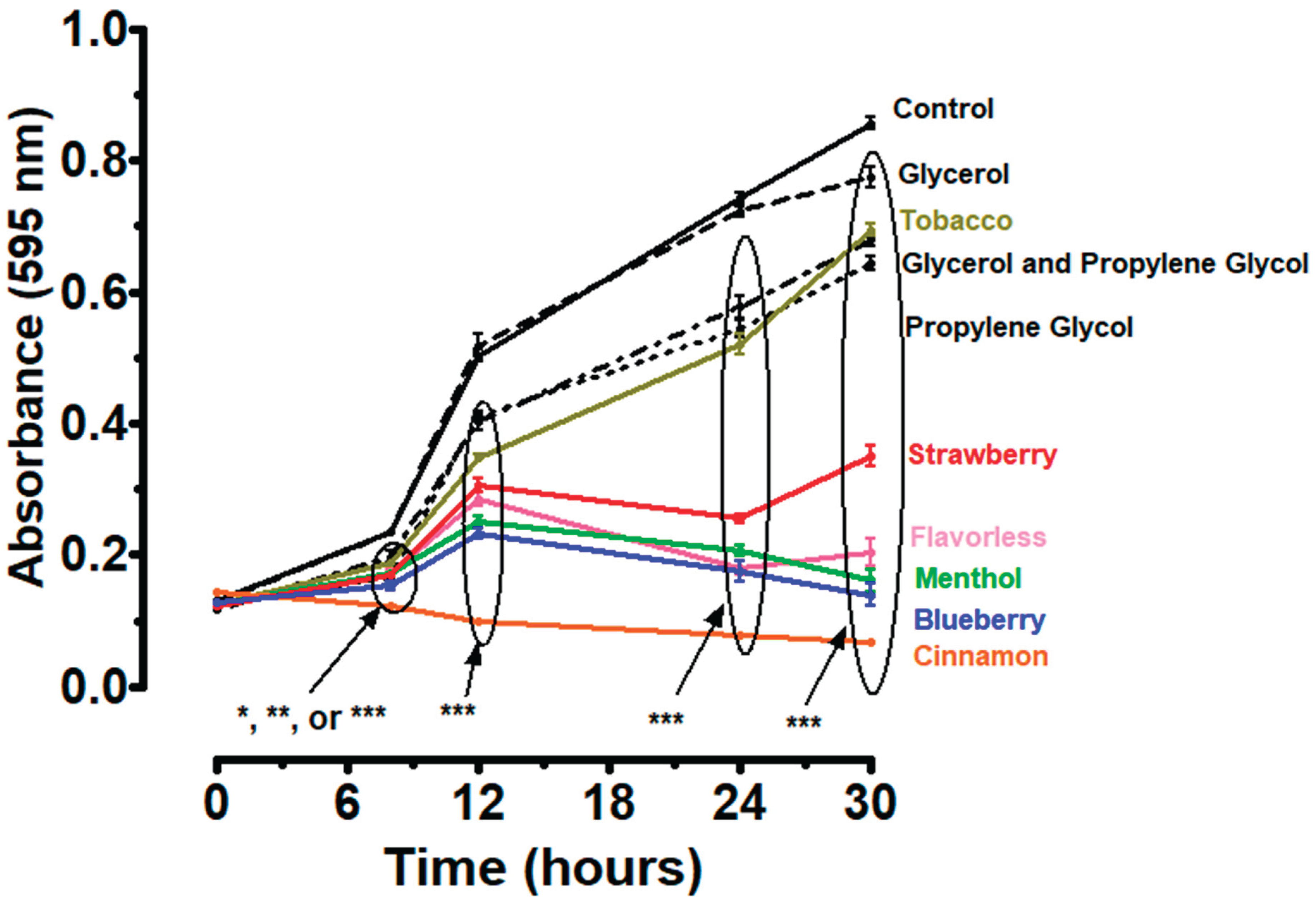

3.1. Effect of E-Liquid Components on P. gingivalis Planktonic Growth

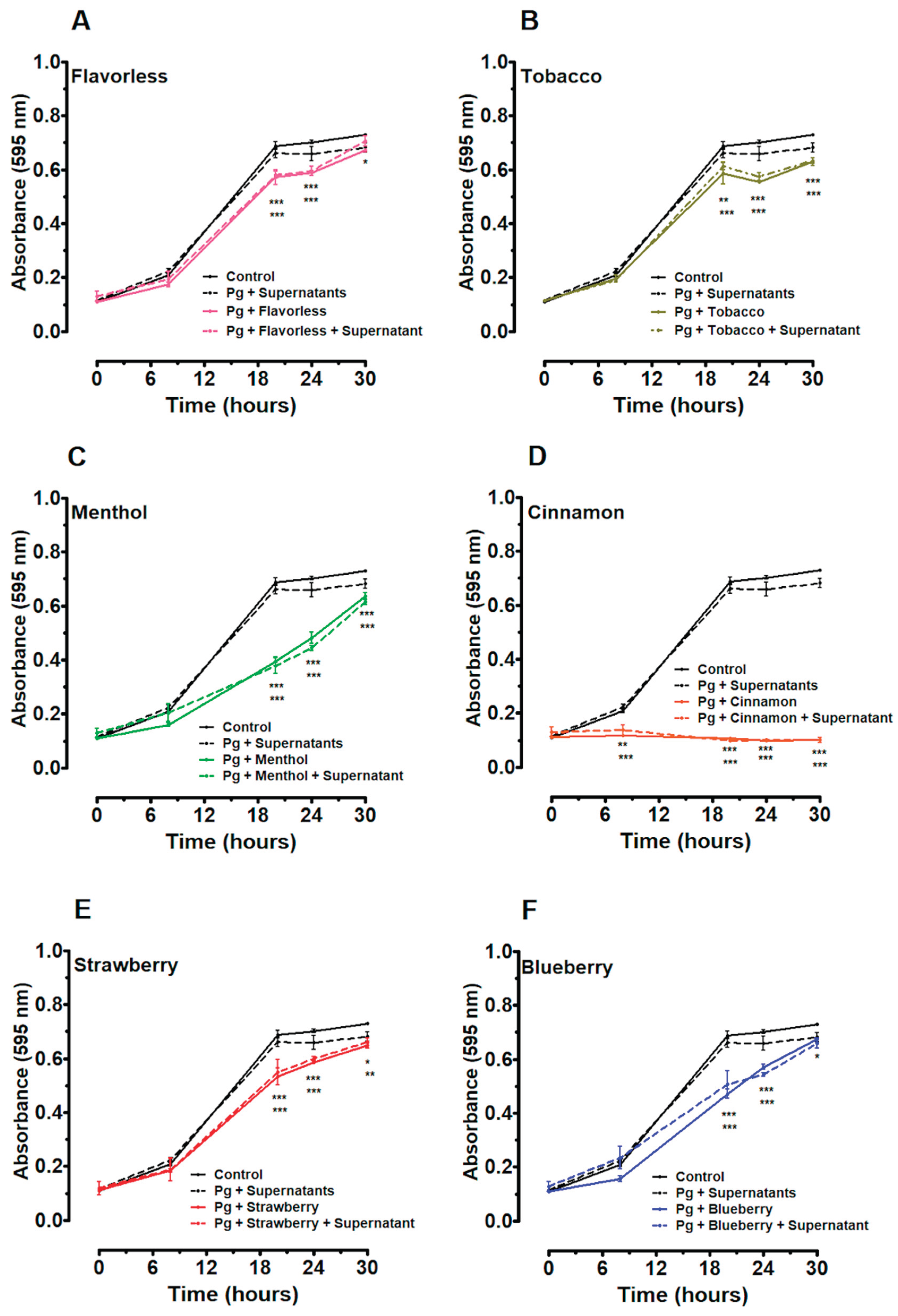

3.2. Effects of E-Liquids and Individual Commensal Supernatants on P. gingivalis Planktonic Growth

3.3. Effects of E-Liquids and Mixed Commensal Supernatants on P. gingivalis Planktonic Growth

3.4. CFU Counts of P. gingivalis at 24 Hour of Planktonic Growth with E-Liquids and Mixed Supernatants

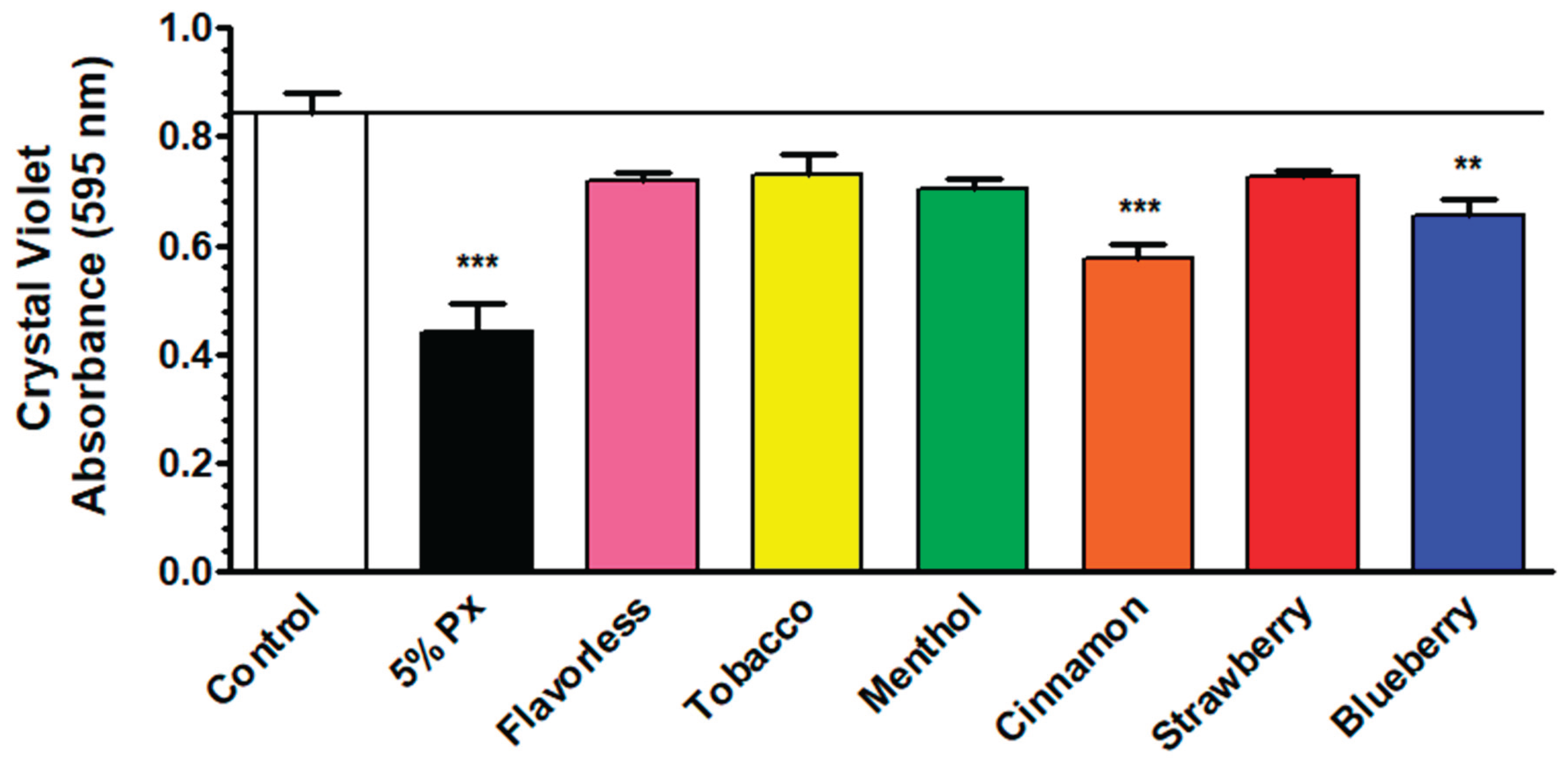

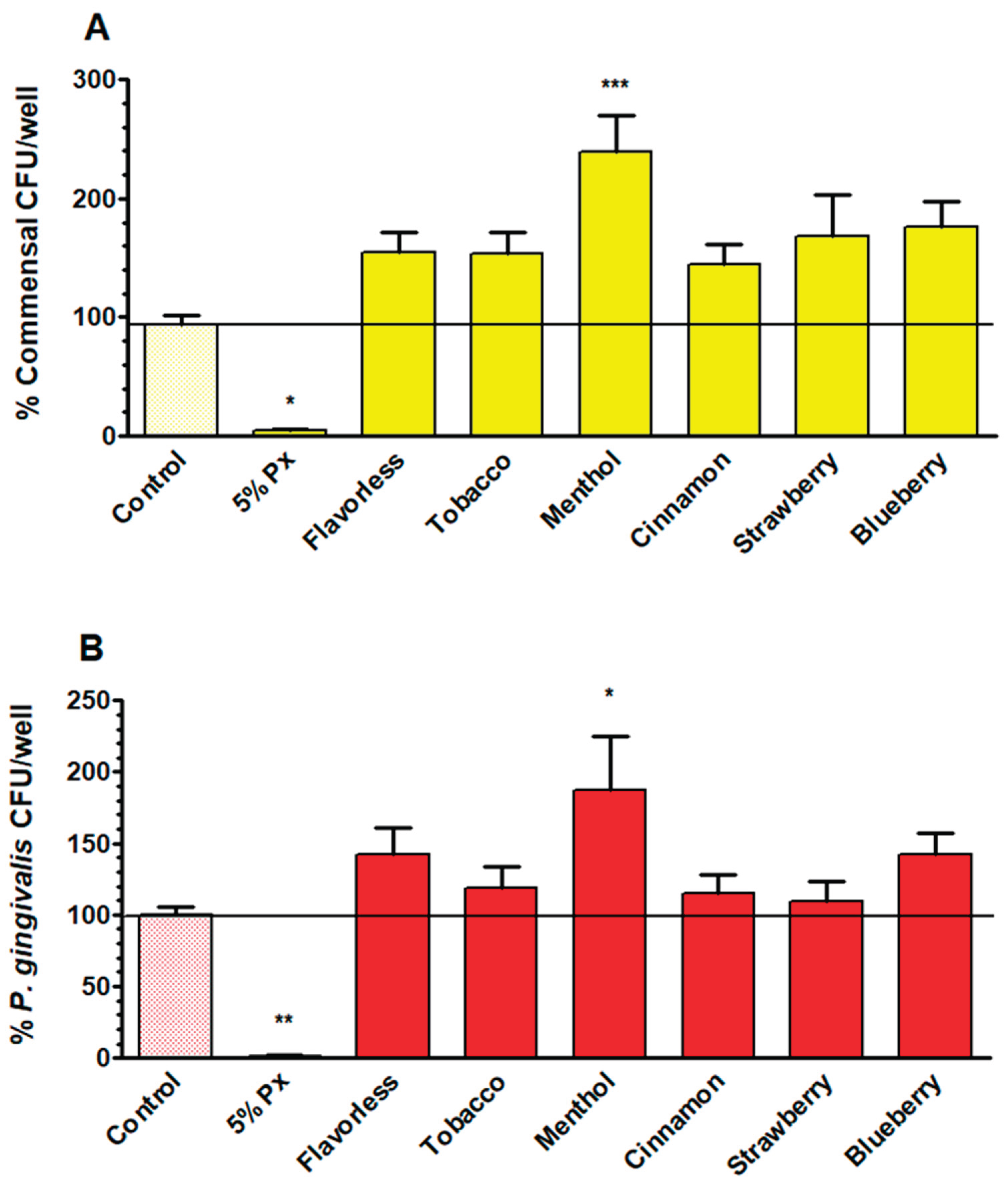

3.5. Quantification of E-Liquid Effects on Multispecies Biofilm Biomass via Crystal Violet Assay

3.6. Quantification of E-Liquid Effects on Multispecies Biofilm Biomass via qPCR

3.7. Quantification of E-Liquid Effects on Multispecies Biofilm Biomass via CFU Counting

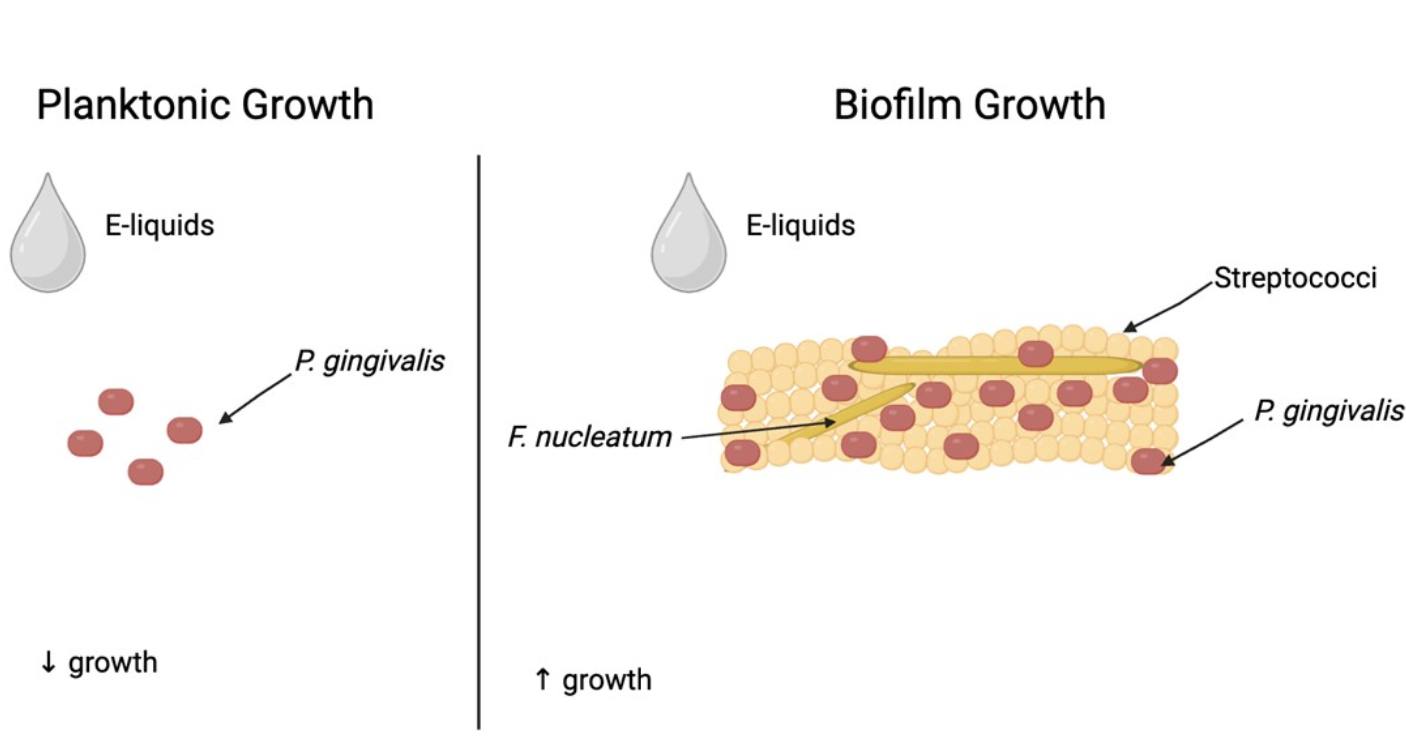

3.8. Comparison of E-Liquid Effects on P. gingivalis Growth Planktonically and in Multispecies Biofilms

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Selekman, J. Vaping: It’s All a Smokescreen—ProQuest Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2184907265?parentSessionId=4ogZxMBzh2Lk87ECvsLC4jJLiQ6qMS%2Bbx%2F0J9sfUzyU%3D&sourcetype=Scholarly%20Journals (accessed on 23 July 2024).

- Glantz, S.A.; Bareham, D.W. E-Cigarettes: Use, Effects on Smoking, Risks, and Policy Implications. Annu Rev Public Health 2018, 39, 215–235. [CrossRef]

- Palazzolo, D.L. Electronic Cigarettes and Vaping: A New Challenge in Clinical Medicine and Public Health. A Literature Review. Front. Public Health 2013, 1. [CrossRef]

- Famiglietti, A.; Memoli, J.W.; Khaitan, P.G. Are Electronic Cigarettes and Vaping Effective Tools for Smoking Cessation? Limited Evidence on Surgical Outcomes: A Narrative Review. J Thorac Dis 2021, 13, 384–395. [CrossRef]

- Besaratinia, A.; Tommasi, S. Vaping: A Growing Global Health Concern. EClinicalMedicine 2019, 17, 100208. [CrossRef]

- Lyzwinski, L.N.; Naslund, J.A.; Miller, C.J.; Eisenberg, M.J. Global Youth Vaping and Respiratory Health: Epidemiology, Interventions, and Policies. npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 2022, 32, 14. [CrossRef]

- Eaton, D.; Kwan, L.; Stratton, K. Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes; The National Academies Press: Washington DC, 2018; ISBN 978-0-309-46834-3.

- Hajek, P.; Etter, J.-F.; Benowitz, N.; Eissenberg, T.; McRobbie, H. Electronic Cigarettes: Review of Use, Content, Safety, Effects on Smokers and Potential for Harm and Benefit. Addiction 2014, 109, 1801–1810. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Drummond, M.B. Electronic Cigarettes as Smoking Cessation Tool: Are We There? Curr Opin Pulm Med 2017, 23, 111–116. [CrossRef]

- While Less Harmful than Cigarettes, e-Cigarettes Still Pose Risks Available online: https://truthinitiative.org/research-resources/emerging-tobacco-products/while-less-harmful-cigarettes-e-cigarettes-pose (accessed on 8 January 2026).

- Cuadra, G.; Hanel, A.; Christian, N.; Pecorelli, S.; Ha, V.; Tomov, S.; Palazzolo, D.; Cuadra, G.; Hanel, A.; Christian, N.; et al. Perspective Chapter: The Impact of Electronic Cigarettes on the Oral Microenvironment; IntechOpen, 2025; ISBN 978-1-83635-438-3.

- Izquierdo-Condoy, J.S.; Naranjo-Lara, P.; Morales-Lapo, E.; Hidalgo, M.R.; Tello-De-la-Torre, A.; Vásconez-Gonzáles, E.; Salazar-Santoliva, C.; Loaiza-Guevara, V.; Rincón Hernández, W.; Becerra, D.A.; et al. Direct Health Implications of E-Cigarette Use: A Systematic Scoping Review with Evidence Assessment. Front. Public Health 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Holliday, R.; Kist, R.; Bauld, L. E-Cigarette Vapour Is Not Inert and Exposure Can Lead to Cell Damage. Evid Based Dent 2016, 17, 2–3. [CrossRef]

- Muthumalage, T.; Prinz, M.; Ansah, K.O.; Gerloff, J.; Sundar, I.K.; Rahman, I. Inflammatory and Oxidative Responses Induced by Exposure to Commonly Used E-Cigarette Flavoring Chemicals and Flavored e-Liquids without Nicotine. Front Physiol 2018, 8, 1130. [CrossRef]

- Clapp, P.W.; Lavrich, K.S.; van Heusden, C.A.; Lazarowski, E.R.; Carson, J.L.; Jaspers, I. Cinnamaldehyde in Flavored E-Cigarette Liquids Temporarily Suppresses Bronchial Epithelial Cell Ciliary Motility by Dysregulation of Mitochondrial Function. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2019, 316, L470–L486. [CrossRef]

- Shamim, A.; Herzog, H.; Shah, R.; Pecorelli, S.; Nisbet, V.; George, A.; Cuadra, G.A.; Palazzolo, D.L. Pathophysiological Responses of Oral Keratinocytes After Exposure to Flavored E-Cigarette Liquids. Dentistry Journal 2025, 13, 60. [CrossRef]

- Shah, R.; Luo, E.D.; Shaffer, C.A.; Tabakha, M.; Tomov, S.; Minton, S.H.; Brown, M.K.; Palazzolo, D.L.; Cuadra, G.A. Polarization of THP-1-Derived Human M0 to M1 Macrophages Exposed to Flavored E-Liquids. Toxics 2025, 13, 451. [CrossRef]

- Ramenzoni, L.L.; Schneider, A.; Fox, S.C.; Meyer, M.; Meboldt, M.; Attin, T.; Schmidlin, P.R. Cytotoxic and Inflammatory Effects of Electronic and Traditional Cigarettes on Oral Gingival Cells Using a Novel Automated Smoking Instrument: An In Vitro Study. Toxics 2022, 10, 179. [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, Z.N.; Alqahtani, A.; Almela, T.; Franklin, K.; Tayebi, L.; Moharamzadeh, K. Effects of Electronic Cigarette Liquid on Monolayer and 3D Tissue-Engineered Models of Human Gingival Mucosa. J Adv Periodontol Implant Dent 2019, 11, 54–62. [CrossRef]

- Palazzolo, D.L.; Nelson, J.M.; Ely, E.A.; Crow, A.P.; Distin, J.; Kunigelis, S.C. The Effects of Electronic Cigarette (ECIG)-Generated Aerosol and Conventional Cigarette Smoke on the Mucociliary Transport Velocity (MTV) Using the Bullfrog (R. Catesbiana) Palate Paradigm. Front Physiol 2017, 8, 1023. [CrossRef]

- Allbright, K.; Villandre, J.; Crotty Alexander, L.E.; Zhang, M.; Benam, K.H.; Evankovich, J.; Königshoff, M.; Chandra, D. The Paradox of the Safer Cigarette: Understanding the Pulmonary Effects of Electronic Cigarettes. Eur Respir J 2024, 63, 2301494. [CrossRef]

- Palazzolo, D.L.; Crow, A.P.; Nelson, J.M.; Johnson, R.A. Trace Metals Derived from Electronic Cigarette (ECIG) Generated Aerosol: Potential Problem of ECIG Devices That Contain Nickel. Front Physiol 2016, 7, 663. [CrossRef]

- HOMD: Human Oral Microbiome Database Available online: https://www.homd.org/# (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- Damyanova, T.; Paunova-Krasteva, T. What We Still Don’t Know About Biofilms—Current Overview and Key Research Information. Microbiology Research 2025, 16, 46. [CrossRef]

- Deo, P.N.; Deshmukh, R. Oral Microbiome: Unveiling the Fundamentals. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol 2019, 23, 122–128. [CrossRef]

- Kolenbrander, P.E.; Andersen, R.N.; Blehert, D.S.; Egland, P.G.; Foster, J.S.; Palmer, R.J. Communication among Oral Bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2002, 66, 486–505, table of contents.

- Jenkinson, H.F.; Lamont, R.J. Oral Microbial Communities in Sickness and in Health. Trends Microbiol 2005, 13, 589–595. [CrossRef]

- Periasamy, S.; Kolenbrander, P.E. Mutualistic Biofilm Communities Develop with Porphyromonas Gingivalis and Initial, Early, and Late Colonizers of Enamel. J. Bacteriol. 2009, 191, 6804–6811. [CrossRef]

- Sakanaka, A.; Kuboniwa, M.; Shimma, S.; Alghamdi, S.A.; Mayumi, S.; Lamont, R.J.; Fukusaki, E.; Amano, A. Fusobacterium Nucleatum Metabolically Integrates Commensals and Pathogens in Oral Biofilms. mSystems 2022, 7, e0017022. [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Chen, Y.-Y.M.; Snyder, J.A.; Burne, R.A. Isolation and Molecular Analysis of the Gene Cluster for the Arginine Deiminase System from Streptococcus Gordonii DL1. Appl Environ Microbiol 2002, 68, 5549–5553. [CrossRef]

- Redanz, S.; Cheng, X.; Giacaman, R.A.; Pfeifer, C.S.; Merritt, J.; Kreth, J. Live and Let Die: Hydrogen Peroxide Production by the Commensal Flora and Its Role in Maintaining a Symbiotic Microbiome. Mol Oral Microbiol 2018, 33, 337–352. [CrossRef]

- Hanel, A.N.; Herzog, H.M.; James, M.G.; Cuadra, G.A. Effects of Oral Commensal Streptococci on Porphyromonas Gingivalis Invasion into Oral Epithelial Cells. Dentistry Journal 2020, 8, 39. [CrossRef]

- Cuadra, G.A.; Smith, M.T.; Nelson, J.M.; Loh, E.K.; Palazzolo, D.L. A Comparison of Flavorless Electronic Cigarette-Generated Aerosol and Conventional Cigarette Smoke on the Survival and Growth of Common Oral Commensal Streptococci. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019, 16, e1669. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J.M.; Cuadra, G.A.; Palazzolo, D.L. A Comparison of Flavorless Electronic Cigarette-Generated Aerosol and Conventional Cigarette Smoke on the Planktonic Growth of Common Oral Commensal Streptococci. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019, 16. [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.P.; Palazzolo, D.L.; Cuadra, G.A. Mechanistic Effects of E-Liquids on Biofilm Formation and Growth of Oral Commensal Streptococcal Communities: Effect of Flavoring Agents. Dent J (Basel) 2022, 10, 85. [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.C.; Xu, F.; Pushalkar, S.; Lin, Z.; Thakor, N.; Vardhan, M.; Flaminio, Z.; Khodadadi-Jamayran, A.; Vasconcelos, R.; Akapo, A.; et al. Electronic Cigarette Use Promotes a Unique Periodontal Microbiome. mBio 13, e00075-22. [CrossRef]

- Cichońska, D.; Kusiak, A.; Goniewicz, M.L. The Impact of E-Cigarettes on Oral Health—A Narrative Review. Dentistry Journal 2024, 12, 404. [CrossRef]

- Aldakheel, F.M.; Alduraywish, S.A.; Jhugroo, P.; Jhugroo, C.; Divakar, D.D. Quantification of Pathogenic Bacteria in the Subgingival Oral Biofilm Samples Collected from Cigarette-Smokers, Individuals Using Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems and Non-Smokers with and without Periodontitis. Arch Oral Biol 2020, 117, 104793. [CrossRef]

- Tabnjh, A.K.; Alizadehgharib, S.; Campus, G.; Lingström, P. The Effects of Electronic Smoking on Dental Caries and Proinflammatory Markers: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Oral Health 2025, 6, 1569806. [CrossRef]

- Gaur, S.; Agnihotri, R. The Role of Electronic Cigarettes in Dental Caries: A Scoping Review. Scientifica (Cairo) 2023, 2023, 9980011. [CrossRef]

- Alkattan, R.; Tashkandi, N.; Mirdad, A.; Ali, H.T.; Alshibani, N.; Allam, E. Effects of Electronic Cigarettes on Periodontal Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. International Dental Journal 2025, 75, 2014–2024. [CrossRef]

- Figueredo, C.A.; Abdelhay, N.; Figueredo, C.M.; Catunda, R.; Gibson, M.P. The Impact of Vaping on Periodontitis: A Systematic Review. Clin Exp Dent Res 2021, 7, 376–384. [CrossRef]

- Pushalkar, S.; Paul, B.; Li, Q.; Yang, J.; Vasconcelos, R.; Makwana, S.; González, J.M.; Shah, S.; Xie, C.; Janal, M.N.; et al. Electronic Cigarette Aerosol Modulates the Oral Microbiome and Increases Risk of Infection. iScience 2020, 23, 100884. [CrossRef]

- Yang, I.; He, X.; Jeon, J.; Claussen, H.; Arthur, R.; Cushenan, P.; Weaver, S.R.; Luo, R.; Black, M.; Shannahan, J.; et al. The Impact of Vaping Behavior on Functional Changes within the Subgingival Microbiome. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 34374. [CrossRef]

- Hajishengallis, G. Periodontitis: From Microbial Immune Subversion to Systemic Inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 2015, 15, 30–44. [CrossRef]

- Mealey, B.L. Influence of Periodontal Infections on Systemic Health. Periodontol. 2000 1999, 21, 197–209.

- Christian, N.; Burden, D.; Emam, A.; Brenk, A.; Sperber, S.; Kalu, M.; Cuadra, G.; Palazzolo, D. Effects of E-Liquids and Their Aerosols on Biofilm Formation and Growth of Oral Commensal Streptococcal Communities: Effect of Cinnamon and Menthol Flavors. Dent J (Basel) 2024, 12, 232. [CrossRef]

- Fischman, J.S.; Sista, S.; Lee, D.; Cuadra, G.A.; Palazzolo, D.L. Flavorless vs. Flavored Electronic Cigarette-Generated Aerosol and E-Liquid on the Growth of Common Oral Commensal Streptococci. Front Physiol 2020, 11, 585416. [CrossRef]

- Werheim, E.R.; Senior, K.G.; Shaffer, C.A.; Cuadra, G.A. Oral Pathogen Porphyromonas Gingivalis Can Escape Phagocytosis of Mammalian Macrophages. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 1432. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Qv, W.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, C.; Chu, M.; Chen, F. The Interplay between Oral Microbes and Immune Responses. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Lamont, R.J.; Koo, H.; Hajishengallis, G. The Oral Microbiota: Dynamic Communities and Host Interactions. Nat Rev Microbiol 2018, 16, 745–759. [CrossRef]

- Mysak, J.; Podzimek, S.; Sommerova, P.; Lyuya-Mi, Y.; Bartova, J.; Janatova, T.; Prochazkova, J.; Duskova, J. Porphyromonas Gingivalis: Major Periodontopathic Pathogen Overview. Journal of Immunology Research 2014, 2014, 476068. [CrossRef]

- Tribble, G.D.; Lamont, R.J. Bacterial Invasion of Epithelial Cells and Spreading in Periodontal Tissue. Periodontology 2000 2010, 52, 68–83. [CrossRef]

- How, K.Y.; Song, K.P.; Chan, K.G. Porphyromonas Gingivalis: An Overview of Periodontopathic Pathogen below the Gum Line. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7. [CrossRef]

- Catala-Valentin, A.; Bernard, J.N.; Caldwell, M.; Maxson, J.; Moore, S.D.; Andl, C.D. E-Cigarette Aerosol Exposure Favors the Growth and Colonization of Oral Streptococcus Mutans Compared to Commensal Streptococci. Microbiol Spectr 2022, 10, e02421-21. [CrossRef]

- Williams, I.; Tuckerman, J.S.; Peters, D.I.; Bangs, M.; Williams, E.; Shin, I.J.; Kaspar, J.R. A Strain of Streptococcus Mitis Inhibits Biofilm Formation of Caries Pathogens via Abundant Hydrogen Peroxide Production. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2025, 91, e02192-24. [CrossRef]

- Baty, J.J.; Stoner, S.N.; Scoffield, J.A. Oral Commensal Streptococci: Gatekeepers of the Oral Cavity. J Bacteriol 2022, 204, e0025722. [CrossRef]

- Avila, M.; Ojcius, D.M.; Yilmaz, O. The Oral Microbiota: Living with a Permanent Guest. DNA Cell Biol. 2009, 28, 405–411. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Huang, S.; Huang, X. Editorial: Mutualistic and Antagonistic Interactions in the Human Oral Microbiome. Front Microbiol 16, 1731807. [CrossRef]

- Kuramitsu, H.K.; He, X.; Lux, R.; Anderson, M.H.; Shi, W. Interspecies Interactions within Oral Microbial Communities. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews 2007, 71, 653–670. [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.P.; Fitzsimonds, Z.R.; Lamont, R.J. Metabolic Signaling and Spatial Interactions in the Oral Polymicrobial Community. J Dent Res 2019, 98, 1308–1314. [CrossRef]

- Kuboniwa, M.; Houser, J.R.; Hendrickson, E.L.; Wang, Q.; Alghamdi, S.A.; Sakanaka, A.; Miller, D.P.; Hutcherson, J.A.; Wang, T.; Beck, D.A.C.; et al. Metabolic Crosstalk Regulates Porphyromonas Gingivalis Colonization and Virulence during Oral Polymicrobial Infection. Nature Microbiology 2017, 2, 1493–1499. [CrossRef]

- Bostanghadiri, N.; Kouhzad, M.; Taki, E.; Elahi, Z.; Khoshbayan, A.; Navidifar, T.; Darban-Sarokhalil, D. Oral Microbiota and Metabolites: Key Players in Oral Health and Disorder, and Microbiota-Based Therapies. Front Microbiol 2024, 15, 1431785. [CrossRef]

- Havermans, A.; Krüsemann, E.J.Z.; Pennings, J.; de Graaf, K.; Boesveldt, S.; Talhout, R. Nearly 20 000 E-Liquids and 250 Unique Flavour Descriptions: An Overview of the Dutch Market Based on Information from Manufacturers. Tob Control 2021, 30, 57–62. [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, A.R.; Vasudevan, S.; Shanmugam, K.; Lévesque, C.M.; Solomon, A.P.; Neelakantan, P. Combinatorial Effects of Trans-Cinnamaldehyde with Fluoride and Chlorhexidine on Streptococcus Mutans. J Appl Microbiol 2021, 130, 382–393. [CrossRef]

- Panariello, B.; Dias Panariello, F.; Misir, A.; Barboza, E.P. An Umbrella Review of E-Cigarettes’ Impact on Oral Microbiota and Biofilm Buildup. Pathogens 2025, 14, 578. [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.P.; Clegg, T.; Ransome, E.; Martin-Lilley, T.; Rosindell, J.; Woodward, G.; Pawar, S.; Bell, T. High-Throughput Characterization of Bacterial Responses to Complex Mixtures of Chemical Pollutants. Nat Microbiol 2024, 9, 938–948. [CrossRef]

| Control | Flavorless | Tobacco | Menthol | Cinnamon | Strawberry | |

| Planktonic* | 100 | 6 | 14 | 11 | 4 | 27 |

| Biofilm** | 100 | 142 | 119 | 187 | 115 | 109 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).