Submitted:

19 January 2026

Posted:

20 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Chemistry

2.2. Synthesis

2.2.1. Procedure for Preparing 2-(2-oxoindolin-3-ylidene)hydrazine-1-Carboxamide (11)

2.2.2. Procedure for Preparing 2-(2-Oxoindolin-3-ylidene)Hydrazine-1-Carbothioamide (13)

2.2.3. Procedure for Preparing 1-(prop-2-yn-1-yl)-2,3-Dihydro-1H-Indole-2,3-Dione (16)

2.2.4. Procedure for Preparing 2-(2-oxo-1-(prop-2-yn-1-yl)Indolin-3-Ylidene)Hydrazinecarboxamide (12)

2.2.5. Procedure for Preparing 2-(2-oxo-1-(prop-2-yn-1-yl)Indolin-3-ylidene)Hydrazinecarbothioamide (14)

2.3. Cytotoxicity Assay in BHK-21 Cells

2.4. Cell-Based Replicon Assay for CHIKV Inhibition

2.5. Viral Replication Inhibition Assay

2.6. Viral Entry Inhibition Assay

2.7. Virus Quantification by RT-qPCR

| CHIKV_Fw | AAAGGGCAAACTCAGCTTCAC |

| CHIKV_Rv | GCCTGGGCTCATCGTTATTC |

2.8. Molecular Modeling and Docking of Isatins with nsP4 and nsP2 Proteins of CHIKV

2.9. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

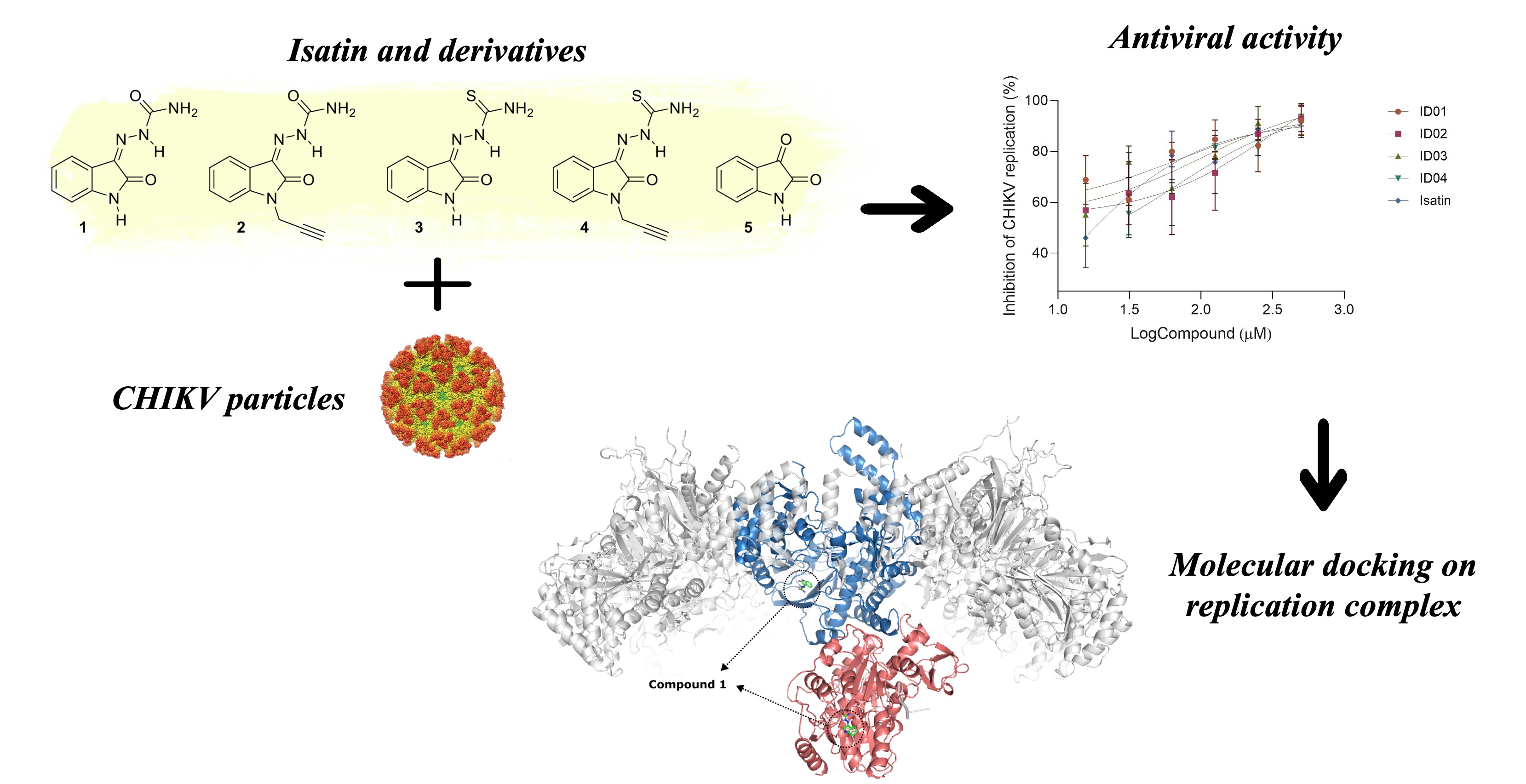

3.1. Chemistry

3.3. Antiviral Activity Using a CHIKV Replicon Model

3.2. Cytotoxicity Analysis

3.4. Antiviral Activity Against Infectious Viral Particles

3.5. Mechanism of Action: Entry vs. Replication Inhibition

3.6. Molecular Docking Analysis and Correlation with Biological Assays

3.6.1. Interactions with nsP2 (Helicase Domain)

3.6.2. Interactions with nsP4 (Polymerase Domain)

3.7. Structural Insights into the Replication Complex

4. Overview and Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hua, C.; Combe, B. Chikungunya Virus-Associated Disease. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2017, 19, 69. [CrossRef]

- Mason, P.J.; Haddow, A.J. An Epidemic of Virus Disease in Southern Province, Tanganyika Territory, in 1952–1953. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1957, 51, 238–240. [CrossRef]

- Zeller, H.; Van Bortel, W.; Sudre, B. Chikungunya: Its History in Africa and Asia and Its Spread to New Regions in 2013-2014. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 214, S436–S440. [CrossRef]

- Weber, W.C.; Streblow, D.N.; Coffey, L.L. Chikungunya Virus Vaccines: A Review of IXCHIQ and PXVX0317 from Pre-Clinical Evaluation to Licensure. BioDrugs 2024, 38, 727–742. [CrossRef]

- Guignard, A.; Praet, N.; Jusot, V.; Bakker, M.; Baril, L. Introducing New Vaccines in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Challenges and Approaches. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2019, 18, 119–131. [CrossRef]

- Ojeda Rodriguez, J.A.; Haftel, A.; Walker, J.R., III Chikungunya Fever. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island (FL), 2025.

- Webb, E.; Michelen, M.; Rigby, I.; Dagens, A.; Dahmash, D.; Cheng, V.; Joseph, R.; Lipworth, S.; Harriss, E.; Cai, E.; et al. An Evaluation of Global Chikungunya Clinical Management Guidelines: A Systematic Review. EClinicalMedicine 2022, 54, 101672. [CrossRef]

- Law, Y.-S.; Wang, S.; Tan, Y.B.; Shih, O.; Utt, A.; Goh, W.Y.; Lian, B.-J.; Chen, M.W.; Jeng, U.-S.; Merits, A.; et al. Interdomain Flexibility of Chikungunya Virus nsP2 Helicase-Protease Differentially Influences Viral RNA Replication and Infectivity. J. Virol. 2021, 95. [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.B.; Chmielewski, D.; Law, M.C.Y.; Zhang, K.; He, Y.; Chen, M.; Jin, J.; Luo, D. Molecular Architecture of the Chikungunya Virus Replication Complex. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eadd2536. [CrossRef]

- Borges, P.H.O.; Ferreira, S.B.; Silva, F.P., Jr Recent Advances on Targeting Proteases for Antiviral Development. Viruses 2024, 16, 366. [CrossRef]

- Behrouz, S.; Kühl, N.; Klein, C.D. N-Sulfonyl Peptide-Hybrids as a New Class of Dengue Virus Protease Inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 251, 115227. [CrossRef]

- Dansana, J.; Purohit, P.; Panda, M.; Meher, B.R. Recent Advances in Phytocompounds as Potential Chikungunya Virus Non-Structural Protein 2 Protease Antagonists: A Systematic Review. Phytomedicine 2025, 136, 156359. [CrossRef]

- Rocha, D.C.P.; Sisnande, T.; Gavino-Leopoldino, D.; Guimarães-Andrade, I.P.; Cruz, F.F.; Assunção-Miranda, I.; Mendonça, S.C.; Leitão, G.G.; Simas, R.C.; Mohana-Borges, R.; et al. Antiviral, Cytoprotective, and Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Ampelozizyphus Amazonicus Ducke Ethanolic Wood Extract on Chikungunya Virus Infection. Viruses 2023, 15. [CrossRef]

- Elsaman, T.; Mohamed, M.S.; Eltayib, E.M.; Abdel-Aziz, H.A.; Abdalla, A.E.; Munir, M.U.; Mohamed, M.A. Isatin Derivatives as Broad-Spectrum Antiviral Agents: The Current Landscape. Med. Chem. Res. 2022, 31, 244–273. [CrossRef]

- De Moraes Gomes, P.A.T.; Pena, L.J.; Leite, A.C.L. Isatin Derivatives and Their Antiviral Properties against Arboviruses: A Review. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2019, 19, 56–62. [CrossRef]

- Kostova, I.; Saso, L. Advances in Research of Schiff-Base Metal Complexes as Potent Antioxidants. Curr. Med. Chem. 2013, 20, 4609–4632. [CrossRef]

- Tumosienė, I.; Jonuškienė, I.; Kantminienė, K.; Mickevičius, V.; Petrikaitė, V. Novel N-Substituted Amino Acid Hydrazone-Isatin Derivatives: Synthesis, Antioxidant Activity, and Anticancer Activity in 2D and 3D Models in Vitro. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7799. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhao, S.-J.; Lv, Z.-S.; Gao, F.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, F.; Bai, L.; Deng, J.-L. Fluoroquinolone-Isatin Hybrids and Their Biological Activities. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 162, 396–406. [CrossRef]

- Varun; Sonam; Kakkar, R. Isatin and Its Derivatives: A Survey of Recent Syntheses, Reactions, and Applications. Medchemcomm 2019, 10, 351–368. [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Xie, X.; Ye, N.; Zou, J.; Chen, H.; White, M.A.; Shi, P.Y.; Zhou, J. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Evaluation of Substituted 4,6-Dihydrospiro[[1,2,3]triazolo[4,5- B]pyridine-7,3′-Indoline]-2′,5(3 H)-Dione Analogues as Potent NS4B Inhibitors for the Treatment of Dengue Virus Infection. Journal of medicinal chemistry 2019, 62, 7941–7960. [CrossRef]

- Bal, T.R.; Anand, B.; Yogeeswari, P.; Sriram, D. Synthesis and Evaluation of Anti-HIV Activity of Isatin Beta-Thiosemicarbazone Derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005, 15, 4451–4455. [CrossRef]

- Zou, B.; Chan, W.L.; Ding, M.; Leong, S.Y.; Nilar, S.; Seah, P.G.; Liu, W.; Karuna, R.; Blasco, F.; Yip, A.; et al. Lead Optimization of Spiropyrazolopyridones: A New and Potent Class of Dengue Virus Inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 344–348. [CrossRef]

- Mishra, P.; Kumar, A.; Mamidi, P.; Kumar, S.; Basantray, I.; Saswat, T.; Das, I.; Nayak, T.K.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Subudhi, B.B.; et al. Inhibition of Chikungunya Virus Replication by 1-[(2-Methylbenzimidazol-1-Yl) Methyl]-2-Oxo-Indolin-3-Ylidene] Amino] thiourea(MBZM-N-IBT). Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20122. [CrossRef]

- Lebeau, P.F.; Chen, J.; Byun, J.H.; Platko, K.; Austin, R.C. The Trypan Blue Cellular Debris Assay: A Novel Low-Cost Method for the Rapid Quantification of Cell Death. MethodsX 2019, 6, 1174–1180. [CrossRef]

- Cunha, M.S.; Cruz, N.V.G.; Schnellrath, L.C.; Medaglia, M.L.G.; Casotto, M.E.; Albano, R.M.; Costa, L.J.; Damaso, C.R. Autochthonous Transmission of East/Central/South African Genotype Chikungunya Virus, Brazil. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2017, 23, 1737–1739. [CrossRef]

- Lanciotti, R.S.; Calisher, C.H.; Gubler, D.J.; Chang, G.J.; Vorndam, A.V. Rapid Detection and Typing of Dengue Viruses from Clinical Samples by Using Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1992, 30, 545–551. [CrossRef]

- Freire, M.C.L.C.; Basso, L.G.M.; Mendes, L.F.S.; Mesquita, N.C.M.R.; Mottin, M.; Fernandes, R.S.; Policastro, L.R.; Godoy, A.S.; Santos, I.A.; Ruiz, U.E.A.; et al. Characterization of the RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase from Chikungunya Virus and Discovery of a Novel Ligand as a Potential Drug Candidate. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 10601. [CrossRef]

- Law, Y.-S.; Utt, A.; Tan, Y.B.; Zheng, J.; Wang, S.; Chen, M.W.; Griffin, P.R.; Merits, A.; Luo, D. Structural Insights into RNA Recognition by the Chikungunya Virus nsP2 Helicase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2019, 116, 9558–9567. [CrossRef]

- Olomola, T.O.; Bada, D.A.; Obafemi, C.A. Synthesis and Antibacterial Activity of Two Spiro [indole] Thiadiazole Derivatives. Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 2009, 91, 941–946. [CrossRef]

- Saranya, S.; Haribabu, J.; Vadakkedathu Palakkeezhillam, V.N.; Jerome, P.; Gomathi, K.; Rao, K.K.; Hara Surendra Babu, V.H.; Karvembu, R.; Gayathri, D. Molecular Structures, Hirshfeld Analysis and Biological Investigations of Isatin Based Thiosemicarbazones. J. Mol. Struct. 2019, 1198, 126904. [CrossRef]

- Haj Mohammad Ebrahim Tehrani, K.; Hashemi, M.; Hassan, M.; Kobarfard, F.; Mohebbi, S. Synthesis and Antibacterial Activity of Schiff Bases of 5-Substituted Isatins. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2016, 27, 221–225. [CrossRef]

- Yu, B.; Qi, P.-P.; Shi, X.-J.; Huang, R.; Guo, H.; Zheng, Y.-C.; Yu, D.-Q.; Liu, H.-M. Efficient Synthesis of New Antiproliferative Steroidal Hybrids Using the Molecular Hybridization Approach. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 117, 241–255. [CrossRef]

- Huong, T.-T.-L.; Dung, D.-T.-M.; Huan, N.-V.; Cuong, L.-V.; Hai, P.-T.; Huong, L.-T.-T.; Kim, J.; Kim, Y.-G.; Han, S.-B.; Nam, N.-H. Novel N-Hydroxybenzamides Incorporating 2-Oxoindoline with Unexpected Potent Histone Deacetylase Inhibitory Effects and Antitumor Cytotoxicity. Bioorg. Chem. 2017, 71, 160–169. [CrossRef]

- Silva, M.; Gonçalves, J.C.O.; Oliveira-Campos, A.M.F.; Rodrigues, L.M.; Esteves, A.P. Synthesis of Novel Glycoconjugates Derived from Alkynyl Heterocycles through a Click Approach. Synth. Commun. 2013, 43, 1432–1438. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Lal, K.; Kumar, V.; Murtaza, M.; Jaglan, S.; Paul, A.K.; Yadav, S.; Kumari, K. Synthesis, Antimicrobial, Antibiofilm and Computational Studies of Isatin-Semicarbazone Tethered 1,2,3-Triazoles. Bioorg. Chem. 2023, 133, 106388. [CrossRef]

- Pohjala, L.; Utt, A.; Varjak, M.; Lulla, A.; Merits, A.; Ahola, T.; Tammela, P. Inhibitors of Alphavirus Entry and Replication Identified with a Stable Chikungunya Replicon Cell Line and Virus-Based Assays. PLoS One 2011, 6, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Gigante, A.; Gómez-SanJuan, A.; Delang, L.; Li, C.; Bueno, O.; Gamo, A.-M.; Priego, E.-M.; Camarasa, M.-J.; Jochmans, D.; Leyssen, P.; et al. Antiviral Activity of [1,2,3]triazolo[4,5- D ]pyrimidin-7(6 H )-Ones against Chikungunya Virus Targeting the Viral Capping nsP1. Antiviral Res. 2017, 144, 216–222. [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Dhanwani, R.; Patro, I.K.; Rao, P.V.L.; Parida, M.M. Cellular IMPDH Enzyme Activity Is a Potential Target for the Inhibition of Chikungunya Virus Replication and Virus Induced Apoptosis in Cultured Mammalian Cells. Antiviral Res. 2011, 89, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.C.; Reis, P.A.; de Freitas, C.S.; Sacramento, C.Q.; Villas Bôas Hoelz, L.; Bastos, M.M.; Mattos, M.; Rocha, N.; Gomes de Azevedo Quintanilha, I.; da Silva Gouveia Pedrosa, C.; et al. Beyond Members of the Flaviviridae Family, Sofosbuvir Also Inhibits Chikungunya Virus Replication. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63. [CrossRef]

- Abdelnabi, R.; Jochmans, D.; Verbeken, E.; Neyts, J.; Delang, L. Antiviral Treatment Efficiently Inhibits Chikungunya Virus Infection in the Joints of Mice during the Acute but Not during the Chronic Phase of the Infection. Antiviral Res. 2018, 149, 113–117. [CrossRef]

- Lani, R.; Hassandarvish, P.; Chiam, C.W.; Moghaddam, E.; Chu, J.J.H.; Rausalu, K.; Merits, A.; Higgs, S.; Vanlandingham, D.; Abu Bakar, S.; et al. Antiviral Activity of Silymarin against Chikungunya Virus. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 11421. [CrossRef]

- Abu Bakar, F.; Ng, L.F.P. Nonstructural Proteins of Alphavirus-Potential Targets for Drug Development. Viruses 2018, 10. [CrossRef]

- Battisti, V.; Urban, E.; Langer, T. Antivirals against the Chikungunya Virus. Viruses 2021, 13, 1307.

- Navarro, H.; Scott, J.E.; Smith, G.R.; Ghiabi, P.; Gibson, E.; Loppnau, P.; Harding, R.J.; Hossain, M.A.; Bose, M.R.; Pearce, K.H.; et al. Identification of Inhibitors of Chikungunya Virus nsP2 ATPase. bioRxivorg 2025.

- Santana, A.C.; Silva Filho, R.C.; Menezes, J.C.J.M.D.S.; Allonso, D.; Campos, V.R. Nitrogen-Based Heterocyclic Compounds: A Promising Class of Antiviral Agents against Chikungunya Virus. Life (Basel) 2020, 11, 16. [CrossRef]

- Metibemu, D.S.; Adeyinka, O.S.; Falode, J.; Crown, O.; Ogungbe, I.V. Inhibitors of the Structural and Nonstructural Proteins of Alphaviruses. ACS Infect. Dis. 2024, 10, 2507–2524. [CrossRef]

- Furuta, Y.; Gowen, B.B.; Takahashi, K.; Shiraki, K.; Smee, D.F.; Barnard, D.L. Favipiravir (T-705), a Novel Viral RNA Polymerase Inhibitor. Antiviral Res. 2013, 100, 446–454. [CrossRef]

- Rabelo, V.W.-H.; Paixão, I.C.N. de P.; Abreu, P.A. Targeting Chikungunya Virus by Computational Approaches: From Viral Biology to the Development of Therapeutic Strategies. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2020, 24, 63–78. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Wang, L.; Leng, P.; Guo, J.; Zhou, H. Drugs Targeting Structural and Nonstructural Proteins of the Chikungunya Virus: A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 262, 129949. [CrossRef]

| Compound | EGFPEC50 (μM) | EC50 (μM) | CC50 (μM) | SI (CC50 / EC50) |

| Isatin | 340.6 | 20.2 | >500 | 24.7 |

| ID11 | >500 | 24.6 | >500 | 34.2 |

| ID12 | >500 | 32.6 | >500 | 15.3 |

| ID13 | 189.7 | 20.0 | >500 | 25 |

| ID14 | 152.92 | 33.6 | >500 | 14.9 |

| Compound | NSP2 | NSP4 |

| Score | Score | |

| simone..tammaro | -31.3 ± 0.1 | -27.4 ± 0.2 |

| simone..tammaro | -33.8 ± 0.1 | -29.8 ± 0.4 |

| simone..tammaro | -32.9 ± 0.5 | -31.9 ± 0.2 |

| simone..tammaro | -32.5 ± 0.3 | -29.8 ± 0.2 |

| simone..tammaro | -34.9 ± 0.5 | -32.4 ± 0.3 |

| simone..tammaro | -21.1±0.2 | -22.6±0.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).