1. Introduction

Most of the urban poor in the Global South live in informal settlements marked by high poverty, food insecurity, and poor health and nutrition [

1,

2,

3]. In many of these cities, the informal economy plays a crucial role in economic growth and social well-being. In Kenya, around 60% of Nairobi’s population is estimated to reside in informal settlements [

4]. Many residents rely heavily on the informal economy for their livelihoods [

5]. Therefore, the informal economy is not just a temporary situation; it provides employment to a large portion of the urban population [

6]. It acts as a safety net and a means of survival for the urban poor, including women. It is estimated that 83% of Kenya’s workforce is informally employed, and over 89% of employed women work in the informal sector [

7].

The informal food economy is a key part of the broader informal economy and urban food systems in the Global South [

8]. Urban food systems in the Global South feature a mix of market and non-market food sourcing methods, along with formal and informal food retail outlets, the latter including street and market food vendors [

9]. These informal urban food systems have proliferated, attracting more attention from academics, researchers, and policymakers. According to Giroux et al. [

10], informal food vendors are individual retailers who usually operate outside the formal food provisioning system and often conduct business without legal status or protection. The role of the informal food economy, especially street and market vendors, is vital in providing food for the poor [

8].

Battersby & Watson [

9] noted that while urban households may buy from both informal and formal outlets, poorer households rely more heavily on informal vendors. Informal vendors offer food on credit and sell smaller, affordable portions, making food accessible to low-wage earners. Informal food vending provides essential opportunities for livelihoods and income, particularly for women in informal settlements [

11]. These vendors play a crucial role in providing affordable, accessible, and diverse food to the urban poor, while also supporting the livelihoods of many others, including vendors, small-scale farmers, transporters, and other actors in the food supply chain [

12,

13]. Overall, the importance of informal food vendors for urban food security and urban livelihoods cannot be overstated.

Typically, many informal food vendors are women, although the gender balance varies within and across countries [

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. They are present in large numbers due to the sociocultural roles of food preparation, traditionally associated with women, and the ease of entering food vending enterprises. Ramasamy [

19] notes that informal food vending provides employment and livelihood opportunities for women who are more vulnerable to fluctuating economic conditions and environments. Chege et al. [

20] estimate that 61% of food vendors in Nairobi’s slum and non-slum areas are women, a trend common in many cities across the Global South. The activity has helped women in the informal sector achieve financial independence and contribute to household incomes [

6].

However, women street food vendors face multiple challenges in managing their enterprises [

21,

22,

23]. For instance, they have poorer access to capital due to limited collateral, reduced bargaining power, and face discrimination from financial institutions like banks [

24]. They often carry the additional burden of caring for their families and encounter sociocultural barriers that affect their business ventures. Women involved in informal sector activities must balance their cultural, reproductive, and productive roles, which increases their overall workload, much of which is undervalued, unmeasured, and unpaid [

25].

Women workers in the informal sector, especially street vendors, were among the most adversely affected groups during the COVID-19 pandemic [

26,

27,

28]. In many sub-Saharan African countries, the pandemic caused multiple unintended and unprecedented negative consequences for the informal sector and informal food systems [

26,

29]. Bene [

30] argues that the COVID-19 pandemic exposed the fragility of our food systems and how easily they can be unsettled. Global food supply chains faced significant disruptions [

31]. As urban areas were ‘hotspots’ for the novel coronavirus infections, the normal business activities of urban food vendors were also significantly impacted. Several large cities, including Nairobi, faced extended public health restrictions and experienced stronger socioeconomic shocks due to the pandemic [

32]. Furthermore, the negative economic, health-related, and food security impacts and challenges of the COVID-19 crisis were most sharply felt by women employed and self-employed in the informal food sector [

28].

Whereas there a growing literature on the impact of Covid-19 pandemic, limited evidence exists on the impact of the pandemic on informal female-owned enterprises, and especially those that are located in urban informal settlements. Available studies reveal that COVID-19 containment measures had profound consequences on the lives of residents in informal settlements, affecting economic stability, food security, general well-being, and the operations of informal entrepreneurs in these neighbourhoods [

33,

34,

35,

36]. Notably, Pinchoff et al. [

35] study in Nairobi’s informal settlements indicates that women were more severely affected during the pandemic and much more likely to face income losses and food insecurity. Our study contributes to this debate through an assessment of the adverse impacts of COVID-19 pandemic and coping strategies among women street food vendors in urban informal settlements.

2. Materials and Methods

The quantitative survey aimed to achieve four main objectives: first, to identify the demographic characteristics of women food vendors operating in urban informal settlements; second, to determine the characteristics of food vending enterprises operated by women in urban informal settlements, including enterprise opportunities and challenges; third, to assess the impacts of COVID-19 on the vendors’ businesses; and finally, to identify the coping strategies employed by women informal food vendors during the pandemic and how these strategies supported their enterprise recovery from its adverse effects.

The survey was carried out in four informal settlements in Nairobi: Mukuru Kwa Njenga, Mukuru Kwa Reuben (located in Embakasi sub-County), Viwandani (Makadara sub-County), and Mathare (Mathare sub-County). Mukuru Kwa Njenga, Mukuru Kwa Reuben, and Viwandani, which border each other, are part of the larger Mukuru informal settlement located near Nairobi’s industrial area, about 7 kilometres south-east of the city’s Central Business District (CBD). On the other hand, Mathare is located about 6 kilometres north-west of the CBD.

To ensure a more comprehensive spatial coverage of the four settlements, the study used a stratified random sampling method. Stratification was based on the villages within each settlement. In each stratum (village), a random sample of informal food vendors was chosen, paying attention to their distribution along specific streets or roads. The sampling process was coordinated together with the settlement leaders who possessed contextual knowledge and familiarity with the settlements. Data collection took place in May-June 2024 using KoBoCollect platform and administered through android mobile phones. Data collection assistants were a mix of community-based and university-based co-researchers under the supervision of the project coordinators and settlement leaders who were trained as field supervisors (one from each settlement).

Table 1 shows the distribution of sampled women informal food vendors across the four settlements.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Sampled Vendors

3.1.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics

Table 2 displays the socio-demographic characteristics of the sampled vendors. More than half of the vendors were aged between 18 and 39 years, while an additional 24% were between 40 and 50 years. The remaining 10% were 50 years or older. More than half (55%) of the vendors were married, while 5% were cohabiting. The remaining (41%) were either never married, separated, divorced, or widowed. Most vendors (53%) had some secondary level of schooling, while 13% had received post-secondary college or university education. However, 31% had only primary level of education and very few (3%) had no formal education.

3.1.2. Economic Characteristics

Table 3 shows the types of previous and additional employment or businesses among the vendors. More than half (53%) of the vendors reported that they had previously worked in another job or run a business before starting their food vending ventures. Among these, nearly one-quarter (24%) had worked full-time in the formal sector, while 22% had full-time employment in the informal sector. A further 48% had held part-time jobs in either the informal (27%) or formal (21%) sector. A smaller portion operated a different informal business (14%), and 3% managed a formal business. Conversely, only 17% were involved in extra employment or business activities outside their food vending at the time of the survey. Of these, over half (56%) ran another informal business selling a different product, while 8% sold the same food items at their second business. An additional 27% and 17% were employed part-time in the informal and formal sectors, respectively.

3.1.3. Migration Profile

Of the sampled vendors, 20.5% were born in Nairobi, while 79.5% were born in other counties of Kenya or were non-citizens born outside Kenya (

Table 4). Nearly three-quarters (73%) of the vendors who were born elsewhere migrated to Nairobi between 2000 and 2019, with an additional 10% arriving between 2020 and 2024. Some (17%) were early arrivals who had lived in Nairobi for at least 25 years. The main reason for relocating to the city was to find work (73%), while 16% moved to Nairobi, accompanying family members. Almost a quarter (23%) migrated to the city to join a spouse or other relatives, with another 6% coming to join schools.

3.2. Enterprise Characteristics

3.2.1. Location and Type of Enterprise Premises

Table 5 shows that these food vending enterprises were more likely to be in or near prominent public areas with high foot traffic, such as neighbourhood streets (55%) and main roads (36%), mainly to attract passers-by. Other vendors were found along railway lines (10%) and close to bus stops (6%), while about 10% operated outside the vendors’ homes and near visible institutions like schools and churches, respectively. Only 1% of vendors were part of a designated market. Regarding the type of enterprise premises, most vendors operated their food vending businesses on a raised, makeshift platform with a shade (48%) or without a shade (13%). Others spread their goods on the ground with (11%) or without (12%) a makeshift shade. 9% were operating as a

kibanda or makeshift hotel, while 6% were running their food business from a mobile container.

3.2.2. Entry into Food Vending: Timing and Motivation

More than half (53%) of the vendors started their food vending businesses between 2020 and 2024, with another 37% beginning between 2010 and 2019 (

Table 6). Very few (10%) vendors started their operations before 2010. There were several main reasons why participants engaged in informal food vending ventures. We have categorized these reasons into economic survival reasons, business opportunity reasons, and factors related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

About half (49%) of the vendors stated that they started their business because they could not find other forms of employment. 28% indicated that they wanted to contribute to their household’s financial resources through their informal enterprise, and 11% aimed to support their left-behind relatives in their hometowns. 21% said they sought higher earnings than those from their previous jobs. 20% of participants wished to run their own business, 14% wanted to be productively engaged through their enterprises, while 13% cited the ease of entry and perceived business opportunities as their main motivations. A small portion of the sample (7%) began their own informal food businesses after losing their jobs during the pandemic.

3.2.3. Enterprise Start-Up Capital

Almost all vendors (95%) indicated they needed some capital to start their food vending businesses. As shown in

Table 7, most of them relied on two main sources of start-up capital: personal savings (69%) and loans or support from social networks (38%), including family members, relatives, friends, and

chamas (informal savings groups by mostly women). Nearly 16% of participating vendors took out loans to finance this start-up, with 10% borrowing from mobile phone apps, such as Tala and M-Shwari. These are popular mobile phone-based apps in Kenya that one can use to apply for an instant loan of smaller amounts without any security but repaid within a given period of time with some interest. The loan is credited into one’s mobile phone money account and the amount is determined by assessing the applicant’s M-Pesa (mobile money service) transaction history and previous loan repayment behaviour on the same app. Only 7% obtained loans from various financial institutions, like banks and micro-credit organizations.

3.2.4. Types of Food Sold and Sources of Food Products

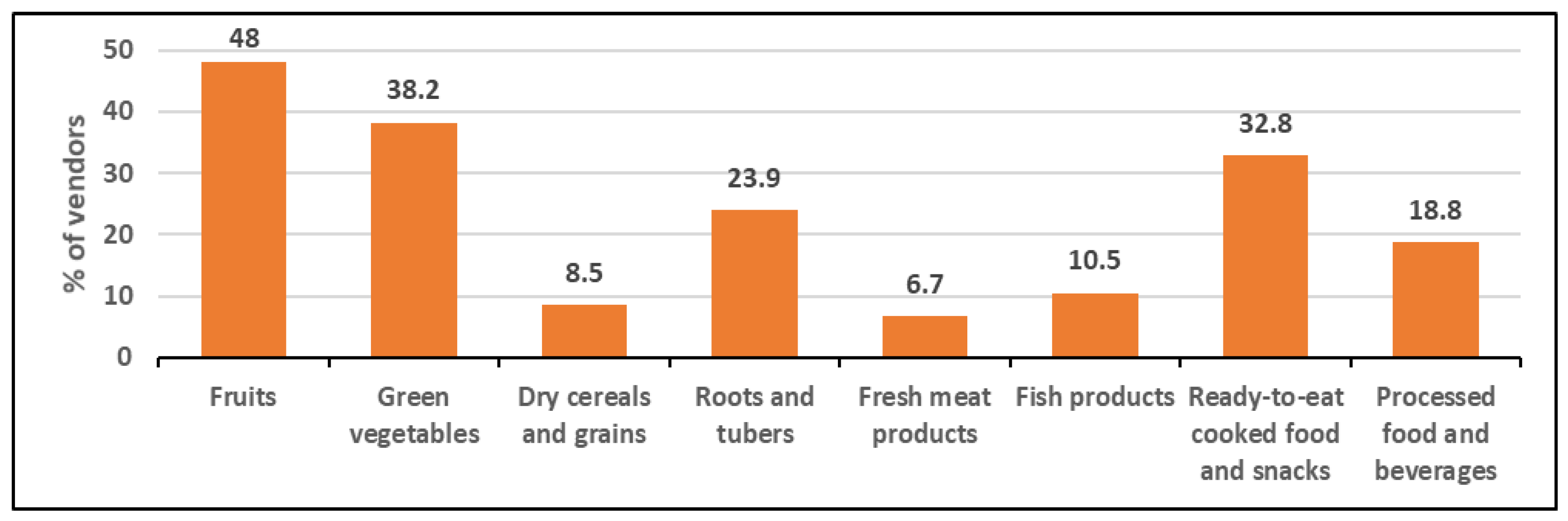

Our survey revealed that vendors offered a diverse selection of food products (

Figure 1). The most common items included fruits (48%), green vegetables (38%), ready-to-eat cooked foods and snacks (33%), and roots and tubers (24%). Nearly one-fifth of vendors sold processed foods and beverages. About 9% of sales consisted of dried cereals and grains. An additional 10% sold fish, while a smaller portion (7%) sold fresh meat. Although roughly 20% of vendors sold less nutritious options such as processed foods and beverages, the remaining vendors provided a wide variety of nutrient-rich foods, including fruits, vegetables, cereals, grains, and both meat and fish products.

Wholesale or retail food markets in Nairobi were the primary sources of food products for the vendors, followed by suppliers within Nairobi. Sources from outside Nairobi were also utilized, mainly by those selling roots and tubers and fish products. Additionally, cereals and grains vendors sourced their products from stores within Nairobi, while vendors selling processed foods obtained their supplies from wholesale or retail shops in Nairobi. Notably, supermarkets were not a common source of food products for most vendors, except for a few vendors who sold cooked and processed foods. The food supplies were primarily transported from their sources to retail points and vendors’ premises using public transportation (65% of the vendors), on foot (33%), motorbikes (26%), hand carts (17%), and through delivery by suppliers (14.5%).

3.3. Enterprise Opportunities and Challenges

3.3.1. Importance of Food Vending Enterprise

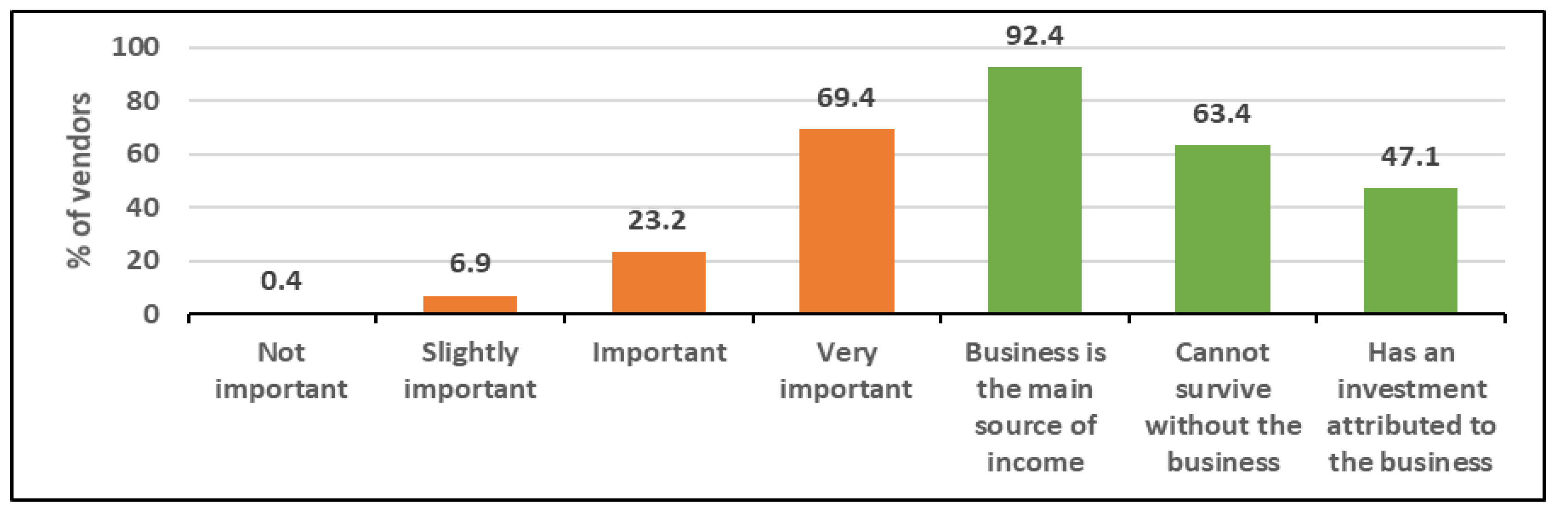

The food vendors were asked how important their food vending businesses were to them, both personally and to their families. A majority (93%) said it was important, with over two-thirds (69%) of vendors indicating it was very important for them and their families, and an additional 23% saying it was important (

Figure 2). Furthermore, a large majority (92%) of vendors reported that the business was their primary source of income. Similarly, 63% stated they could not survive without the income from their vending businesses. Notably, 47% of them were able to save and invest some money through their involvement in the food vending enterprise.

3.3.2. Access to Business Loan, Training and Growth Opportunities

Notably, our sampled women food vendors had limited access to business loans and training opportunities. Only 64 vendors, accounting for 14% of the sample, had previously applied for a bank loan to grow their businesses and had been approved. An additional 11% had applied for a loan but were rejected. Similarly, very few had received formal training on how to operate and expand their businesses. Only 15% of the vendors had participated in a training programme organized by non-state actors such as non-governmental organizations (NGOs), community-based organizations (CBOs), or faith-based organizations (FBOs), while only 9% had received any training from a government or state-organized programme. Despite these challenges, most vendors (95%) expressed their intention to grow their food vending enterprises in the long term. Over half (53%) aimed to seek better business opportunities or employment for themselves.

3.3.3. Food Vending Enterprise Challenges

The food vendors in our study faced multiple business-related challenges, which can be broadly categorized into operational, security and policing, and environmental challenges (

Table 8). The most common operational challenge was weak sales due to a shrinking customer base (61%). Another significant challenge reported by most participants (51%) was the limited shelf life and spoilage of perishable foods, especially fresh produce. Nearly half (49%) of the respondents identified the high cost of doing business, along with weak profit margins, as a major issue. Additionally, 46% of participants cited competition from other vendors offering similar products near their business premises or within their settlement as a key difficulty. Over one-third (35%) of vendors said that non-payment of dues by customers was a tough challenge for them.

Few vendors reported facing security and policing challenges, which partly result from many vendors paying for private security or protection fees to local “gate-keepers” to ensure their safety. Only 8% of vendors had been victims of crime or theft. Notably, fewer than 2% reported that county officers had harassed them or demanded bribes. Some experienced arrests, eviction, or confiscation of goods by Nairobi City County officers. A small segment (6%) of vendors complained about harsh weather (hot sun, heavy rains, flooding), along with inadequate water and electricity, and poor roads, drainage, and sanitation.

3.4. Impact of COVID-19 on Food Vending Enterprises

The results presented in this section are for 260 vendors (58% of the total sample) whose businesses were operational in 2020 and 2021, the first two years of the COVID-19 pandemic. The remaining 188 vendors (42%) started their businesses between 2022 and 2024. The vendors were asked to identify if and how COVID-19 containment measures affected their businesses, addressing multiple aspects, including the cost of operations, prices of food items sold, daily sales and profits, demand, spoilage of certain food products, and overall business operations and patronage. Notably, most vendors consistently observed curfew hours (85%) and wore face masks (84%). A larger percentage (92%) washed their hands frequently. However, physical distancing was regularly maintained by a slightly lower proportion of participants (67%).

3.4.1. Impact on Cost of Business Operations

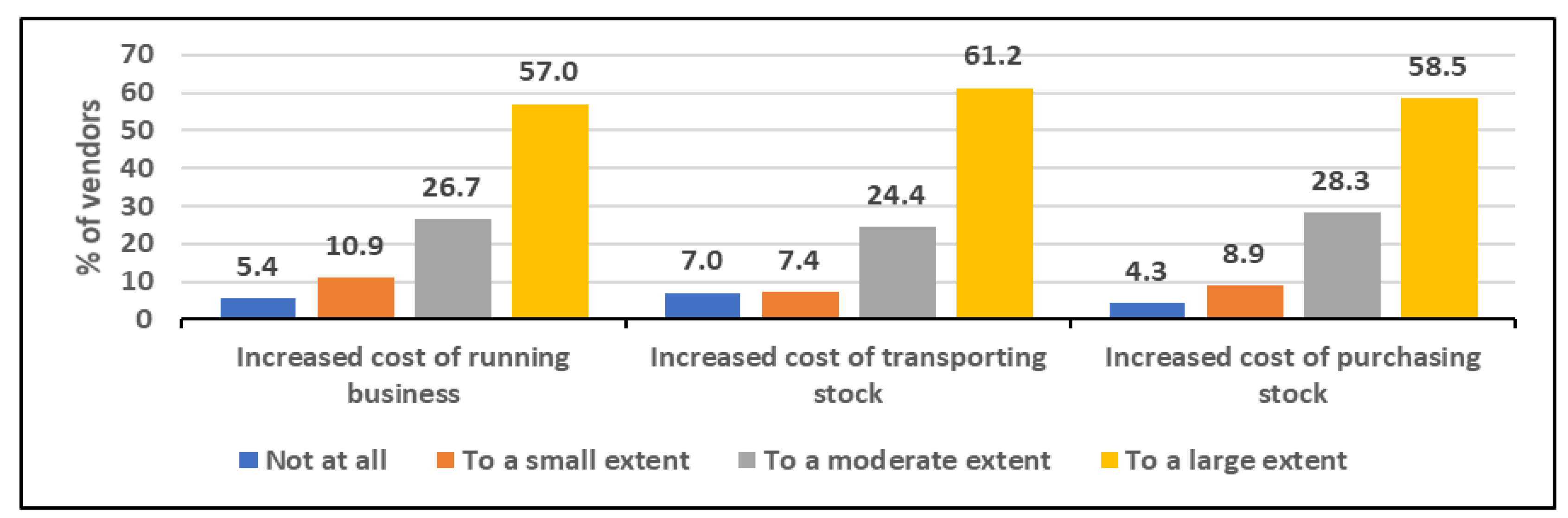

The pandemic increased the overall costs associated with operating a business.

Figure 3 shows that most vendors were negatively affected by these higher costs, including the increased cost of stock due to food inflation. Only a small segment remained unaffected, with a mere 5% unaffected by increased cost of running a business. The higher cost of transporting stock did not impact only 7% of vendors, and just 4% were unaffected by the increased cost of purchasing their stock. The rest were moderately or significantly affected by the higher costs of supplies and transportation. Over half (57%) reported being significantly impacted by the overall higher costs of running a business. Another 27% said that the pandemic increased their operating costs to a moderate extent. 61% were affected by the increased cost of transporting stock, while 59% experienced increased cost of purchasing stock.

3.4.2. Impact on Prices of Food Items

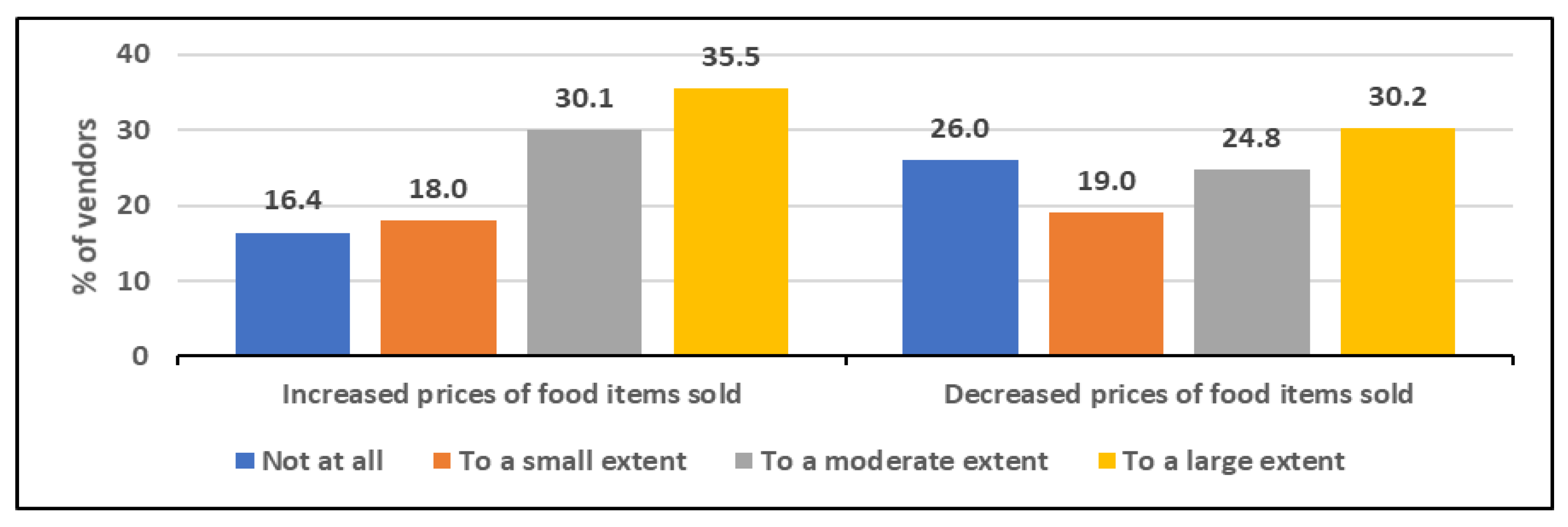

The study participants were asked whether they had altered the prices of their food products during the pandemic. A segment of them sold perishable goods with a short shelf life, including cooked food, meat, and fresh produce. While some vendors managed to keep their regular prices, others indicated that they had to change the prices of their food items to varying degrees (

Figure 4). During the pandemic, vendors were regularly required to adjust their prices according to market conditions and the costs of operating a business. Notably, 35.5% of vendors experienced a significant impact from rising prices, while 30% faced a substantial impact from falling prices of the food items they sold.

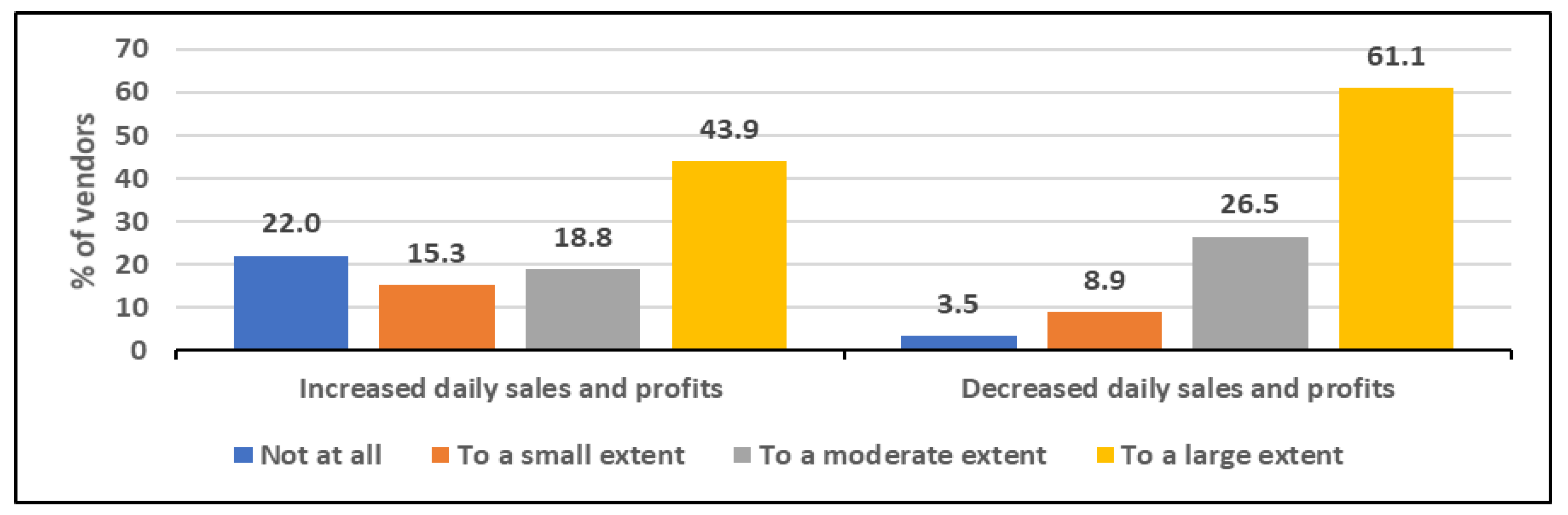

3.4.3. Impact on Daily Sales and Profits

Depending on market forces, vendors experienced fluctuations in their daily sales and profits. While an increase in daily sales and profits was positive for them, a decrease could easily lead to negative consequences for small-scale businesses. Nearly all vendors, except for 9 (3.5% of the sample), reported being negatively affected by reduced daily sales and profits (

Figure 5). Moreover, for 61% of the vendors, this impact was significant. 19% of participants reported moderate increases in daily sales and profits, while 44% experienced a considerable boost. Restrictions on mobility, curfews, lockdowns, a general fear of contracting the virus, and reduced financial resources likely compelled residents to change their shopping habits, which had adverse effects on these vendors’ sales.

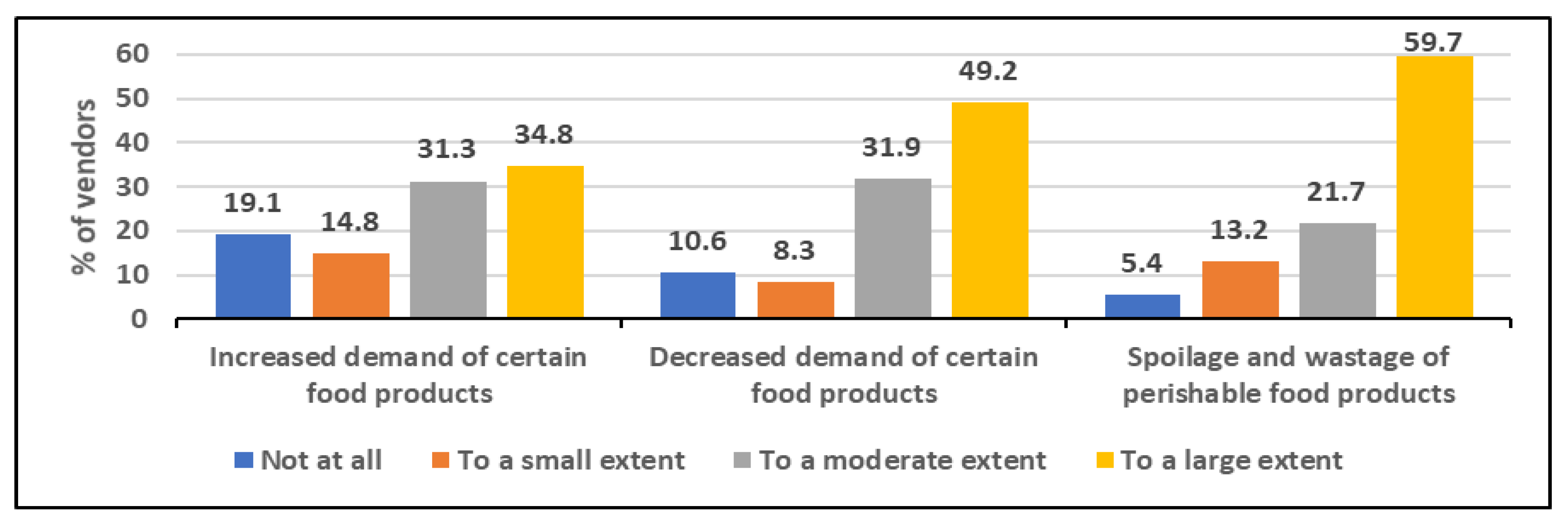

3.4.4. Impact on Demand and Spoilage of Certain Food Products

About one-third (35%) of the vendors experienced a significant impact, mainly due to increased demand (

Figure 6). In comparison, 49% experienced a considerable effect, primarily because of a decline in demand for certain food varieties. During the pandemic, some food items were in high demand because of the popular belief that they could boost immunity and reduce COVID-19 exposure. Similarly, limited supplies of certain food varieties from their sources also led to increased demand from consumers. The increased demand for specific food products clearly benefited vendors, enabling them to maintain supplies; however, a decline in demand inevitably led to adverse outcomes. For instance, 60% of vendors reported that, due to a lack of customers and appropriate storage facilities, perishable food was often spoiled and wasted, causing financial losses.

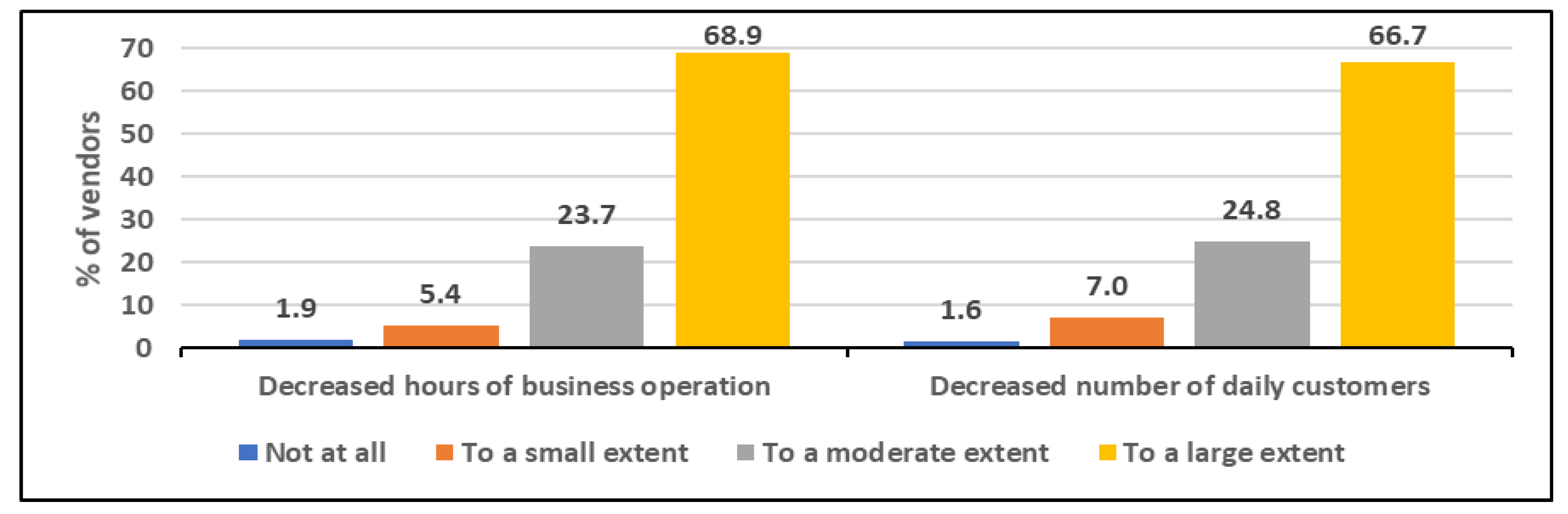

3.4.5. Impact on Business Operation and Patronage

The curfews and lockdowns introduced in Nairobi significantly disrupted the normal operations of vendors. Over two-thirds (69%) of the vendors were heavily affected, and an additional 24% experienced moderate impacts due to the reduced hours of operation (

Figure 7). A further direct result of the curfew and movement restrictions was a decline in the number of daily customers, which had a very significant impact on two-thirds (67%) of the vendors. Another 25% were moderately affected by the decrease in customer numbers.

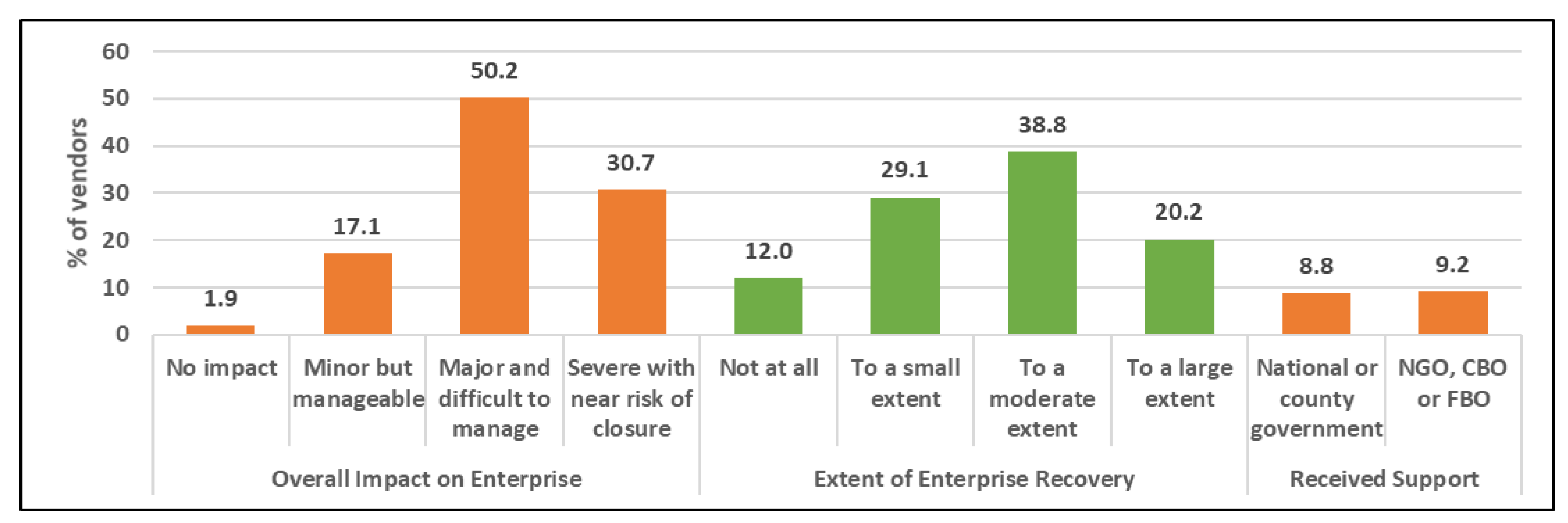

3.4.6. Overall Impact on Enterprise, Extent of Enterprise Recovery and Support

The vendors were asked to share insights on the overall impact of the containment measures on their enterprises, the extent of enterprise recovery in 2024, nearly two years after the pandemic ended, and the support received, if any, during the pandemic. Results shown in

Figure 8 indicate that nearly all vendors experienced either major or severe negative outcomes related to the pandemic. Only 2% of vendors remained unaffected. Half of the vendors (50%) faced significant and hard-to-manage impacts. An additional 31% had experienced severe outcomes that involved a high risk of closure and permanent shutdown.

The recovery of enterprises from the negative impacts of COVID-19 containment measures has been slow and gradual. At the time of the survey, less than a quarter (20%) of vendors had largely recovered, and 39% had recovered to a moderate extent. However, nearly one-third (29%) had only recovered to a small extent. An additional 12% of vendors had not recovered at all from the pandemic’s severe effects. These challenges were amplified by the fact that only a small segment of participants received any form of institutional support or assistance. Only 23 vendors (9% of the sample) reported receiving aid from the national or county government of Nairobi, mainly in the form of financial support such as cash or cash transfers. The number of vendors receiving other types of support was even lower. Two vendors reported receiving food supplies, along with a handwashing bucket and sanitizers. Similarly, a comparable number (24 vendors or 9% of the sample) received assistance from non-governmental organizations (NGOs), community-based organizations (CBOs), or faith-based organizations (FBOs). This support was mostly financial, with some vendors also receiving food and other supplies, like soap.

3.5. Vendors’ Coping Strategies During COVID-19 Pandemic

3.5.1. Enterprise-Level Coping Strategies

Our study participants used various coping strategies to adapt to public health restrictions and continue their businesses during the pandemic (

Table 9). These strategies broadly fall into categories such as price adjustments, stock management, reliance on credit and loan facilities, use of mobile phones for business activities, public health and hygiene measures, and temporary closures. The most common strategies among more than three-quarters of the vendors included reducing stock (92%) and frequency of supplies procurement in a week (77%) to avoid losses, improving hygiene conditions at their premises (95%), and installing handwashing stations for customers (92%). Other strategies used by at least half of the vendors were reducing prices (61%) and selling items on credit (64%) to avoid losses, and relying on mobile phone for business transactions (56% and 56%). Additionally, 38% of vendors had to close their businesses temporarily.

3.5.2. Household-Level Coping Strategies

On the other hand, the sampled vendors adopted several household-level coping strategies, which can be broadly categorized into reliance on personal savings, assets, and additional income; reliance on loans and friends; reducing household consumption and expenditure; and temporary relocation to their rural homes (

Table 10). However, the most common strategies used by more than half of the households were drawing on their personal savings to survive (82%) and reducing non-food household consumption (77%). A striking and challenging finding is that three-fourths (74%) of vendors reduced their household food consumption in response to the pandemic’s financial shocks. One-third (34%) reported taking out loans more frequently through mobile phone apps. One-quarter (25%) reported that at least one of their household members temporarily returned to their rural homes as a pandemic-related coping strategy. 13% of vendors also adopted this strategy.

4. Discussion

This study set out to explore the adverse impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on women food vendors enterprises and their coping strategies across four informal settlements of Nairobi, Kenya. Our findings show that most women vendors in Nairobi’s informal settlements are in the youth age group, married, have secondary level of education, and are recent migrants who relocated to the city, largely driven by economic survival. A number of them had previously worked in another job or run a business in either the formal or informal sector before starting their food vending ventures. However, only a small proportion of the vendors are involved in extra employment or business activities outside their food vending at the time of the survey. This indicates that food vending is the sole income-generating activity for the majority of the women vendors. Similar findings have been observed by Hassan & Rizvi Jafree [

37] who noted that street vending in urban Pakistan serves as a vital survival enterprise for many women marginalized by the formal education sector and lack of employment opportunities, driven by poverty and need to support their families.

Being the only source of income and livelihoods for the women involved, food vending is very important for the majority of the vendors who could not survive without the income from their enterprises. Whereas economic survival is the main reason for entry into food vending business, besides business opportunities, most vendors are recent entrants into the informal food vending sector which generally has limited longevity. This finding qualifies the observation by Singh [

6] that the informal economy is not just a temporary situation; it provides employment to a large portion of the urban population. However, for a few vendors, factors related to the COVID-19 pandemic pushed them to start their food vending enterprises. This implies that food vending provided a crucial safety net and alternative source of income for those who experienced lockdown-induced employment and business losses, especially from other informal sector activities that were significantly impacted.

The women vendors offer a diverse selection of food products to the informal settlements’ communities. Although a few vendors sold less nutritious options such as processed foods and beverages, the remaining vendors provided a wide variety of nutrient-rich foods, including fruits, vegetables, cereals, grains, and both meat and fish products. In separate systematic reviews, Steyn et al. [

38] and Ameye et al. [

39] concluded that street foods make a significant contribution to energy and protein intake and their use should be encouraged if they are healthy traditional foods. While advocating for a healthy diet perspective towards food systems transformations, Brouwer et al. [

40] noted that healthy diets need to be safe, accessible, and affordable for all, including for disadvantaged and nutritionally vulnerable groups. They proposed that interventions and policies to support uptake of healthy diets for all should be guided by information on diets, dietary trends, consumer motives, and food environment characteristics.

It has been demonstrated that training benefits informal food vendors by helping them expand their businesses, reduce losses, and increase sales [

41], while access to affordable credit and loan facilities through cooperative groups helps address common challenges faced by women informal entrepreneurs [

42]. Our findings also show that women food vendors had limited access to business loans and training opportunities. Very few had previously applied for a bank loan to grow their businesses and had been approved, while other were denied. Notably, a large proportion of the vendors drew their start-up capital from personal savings and social networks. According to Gitau et al. [

43], unequal access to financial resources affects male and female food vendors differently, with women vendors being disproportionately disadvantaged due to limited asset ownership, which restricts their access to loan collateral. Similarly, Aberman et al. [

24] and Adeola et al. [

44] noted that women vendors have limited access to financial support and often rely on daily income to sustain their businesses. However, a study of women food vendors in Shinyanga Municipal in Tanzania argues that loans become effective if the beneficiaries have basic training and skills in entrepreneurship and financial management [

45]. In our study, very few women vendors had received formal training from state or non-state actors on how to operate and expand their businesses.

On a day-to-day basis, most of the vendors face operational challenges ranging from low sales due to fewer customers, spoilage of fresh produce, high cost of doing business with little profit, to business competition from similar food sellers. Generally, these are similar challenges, among others, faced by women food vendors in Durban, South Africa [

22], New Delhi, India [

23], and in Nairobi, Kenya and Kampala, Uganda [

43]. However, few vendors in our study reported facing security and policing challenges. In a city-wide survey of food vendors in Nairobi, Kenya, Owuor [

46] found that about one-third of the vendors had experienced harassment, demands for bribes, and confiscation of goods by city-county authorities. Whereas women play an important role in food systems, ignoring the challenges they face leads to further marginalization.

The study findings also reveal that COVID-19 containment measures had varying degrees of negative impact on our sampled women food vendors, particularly in relation to the cost of enterprise operations, demand and prices of food products, spoilage of food products, and daily patronage, sales, and profits. The vendors experienced increased costs of business operations caused by a combination of factors, including higher supplies and transportation costs, as well as extra hygiene measures. They also experienced unpredictable fluctuations on their daily sales and profits, further affecting the retail prices. Moreover, due to lack of storage facilities, perishable food products were especially vulnerable to spoilage. Generally, nearly all vendors experienced either major or severe negative outcomes related to the pandemic which were difficult to manage or with near risk of closure. The findings align with results from similar studies in Kisumu, Kenya [

25] and in South Africa [

47,

48]. Increased costs of running businesses and reduced sales and profits for women vendors meant reduced income, which in turn affected their livelihoods. As such, for women working in the informal food economy, the negative impacts of global pandemics can significantly disrupt their overall livelihoods, economic stability, and survival [

47].

The recovery of enterprises from the negative impacts of COVID-19 containment measures has been slow and gradual. At the time of the survey, less than a quarter of vendors had largely recovered, about one-third had recovered to a moderate extent, about a quarter had only recovered to a small extent, while 12% had not recovered at all from the pandemic’s severe effects. The recovery may have been hampered by the fact that only a small segment of the vendors received any form of institutional support or assistance from state (national and county governments) or non-state actors (non-governmental, community-based, and faith-based organisations). Whereas this finding resonates with that of Donga & Chimucheka [

47] in South Africa and Odhiambo et al. [

25] in Kisumu, Kenya, gaps in support remain a significant barrier to post-pandemic recovery. This finding also implies that women in the informal food economy are central to post-pandemic recovery and must be deliberately targeted.

Finally, the vendors adopted a number of strategies to cope with the negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated containment measures. The most common enterprise-level coping strategies include reducing stock and frequency of supplies procurement to avoid losses, improving hygiene conditions at business premises, installing handwashing stations for customers, reducing prices and selling items on credit to avoid losses, and relying on mobile phone for business transactions. Similar coping mechanisms were observed by Odhiambo et al. [

25] in Kisumu, Kenya. On the other hand, the most commonly used household-level coping strategies include drawing on personal savings to survive, reducing non-food household consumption, and strikingly, reducing household food consumption in response to the pandemic’s financial shocks.

5. Conclusions

Street food vending provides employment and income for women involved in these activities within the informal settlements of Nairobi. It also serves as a livelihood for many who face the dual burden of engaging in income-generating activities while fulfilling their socio-cultural obligations of caring for their families. Despite the livelihood opportunities that informal food vending offers, few strategies are in place to strengthen this potential, address the challenges faced by informal food vendors, and enhance their resilience to the changing global economic, climatic, and environmental conditions that can directly or indirectly impact their vending businesses. Two key challenges identified in this study are the lack of financial support and training necessary to establish and grow their enterprises, leading vendors to rely heavily on their social networks. While loans accessed through mobile apps have created new opportunities, further research is needed to assess whether they contribute to new hardships or debt-related issues for vendors. This dependence on mobile app loans increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, when many households experienced income losses. Our study underscores the urgent need for tailored strategies that promote entrepreneurship, inclusive growth, and innovation within the informal food sector. As informal food vendors are a vital part of the urban landscape, city planners should incorporate them into their planning processes, including considering the gendered aspects of such planning. Furthermore, the pandemic exposed the vulnerabilities of women informal food vendors operating in urban informal settlements while also showcasing their resilience and coping strategies. The main difficulties faced by these vendors and their households included a significant decline in financial resources, along with insufficient pandemic-related assistance for their families and businesses, which adversely affected their livelihoods and household food security. These negative impacts of COVID-19 highlight the importance of targeted support strategies for women-led informal sector economic activities, especially during crises. Such measures could involve improving access to business financing, organizational support, and training opportunities for women in informal vending to help build their resilience against external shocks like the COVID-19 pandemic.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.O.; methodology, S.O., V.W., J.O., S.M. and K.A.; software, J.O.; formal analysis, S.O. and V.W.; investigation, S.O., V.W., J.O., S.M. and K.A.; writing—original draft preparation, S.O.; writing—review and editing, S.J.; supervision, S.O. and V.W.; project administration, S.O.; funding acquisition, S.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the MiFOOD Network, a collaborative project funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) of Canada Partnership Grant No. 895-2021-1004.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki study, and approval was granted by the National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation (Kenya) License No. NACOSTI/P/24/34510 of 13/April/2024.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data is hosted by the MiFOOD Network but is not publicly available currently.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the collaboration and support of the Federation of Slum Dwellers (SDI-Kenya) – Muungano wa Wanavijiji in conducting this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest, and the sponsors had no role in the design, execution, interpretation, or writing of this study.

References

- Agyebang, A.; Peprah, A.; Mensah, J.; Mensah, E. Informal settlement and urban development discourse in the Global South: Evidence from Ghana. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift - Norwegian Journal of Geography 2022, 76(4), 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewnetu, B.; Seo, B. Governance of urban informal settlements in Africa: A scoping review. Heliyon 2025, 11, e43441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Guo, W.; Zhang, Z.; Kisovi, L.; Das, P. Population density and spatial patterns of informal settlements in Nairobi, Kenya. Sustainability 2020, 12(18), 7717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-Habitat. Kenya 2023 A better quality of life for all in an urbanizing world; Country Brief, Nairobi. UNHabitat: Nairobi, 2023; https://unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/2023/07/kenya_country_brief_final_en.pdf.

- Tucker, J.; Anantharaman, M. Informal work and sustainable cities: From formalization to reparation. One Earth 2020, 3(3), 290–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, S.N. Role of street vending in urban livelihood (In case of Mettu town). Socio Economic Challenges 2020, 4(1), 82–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Program (UNDP). Articulating the pathways of the socio-economic impact of the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on the Kenyan economy; UNDP Policy Brief Issue No. 4/2020; UNDP: Nairobi, 2020; https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/78194.

- Young, G.; Crush, J. The urban informal food sector in the Global South. In Handbook on Urban Food Security in the Global South; Crush, J., Frayne, B., Haysom, G., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, 2020; pp. 198–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battersby, J.; Watson, V. Improving urban food security in African cities: Critically assessing the role of informal retailers. In Integrating food into urban planning; Cabannes, Y., Marocchino, C., Eds.; UCL Press and FAO: London and Rome, 2018; pp. 186–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroux, S.; Blekking, J.; Waldman, K.; Resnick, D.; Fobi, D. Informal vendors and food systems planning in an emerging African city. Food Policy 2021, 103, 101997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwango, M.; Kaliba, M.; Chirwa, M.; Guarín, A. Informal food markets in Zambia: Perspectives from vendors, consumers and policymakers in Lusaka and Kitwe. IIED Discussion Paper. 2019. https://www.iied.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/migrate/16659IIED.pdf.

- Kazembe, L.; Nickanor, N.; Crush, J. Informalized containment: Food markets and the governance of the informal food sector in Windhoek, Namibia. Environment and Urbanization 2019, 31(2), 461–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawodzera, G. Food vending and the urban informal food sector in Cape Town, South Africa. Hungry Cities Partnership Discussion Paper No. 23, Waterloo. 2019. https://hungrycities.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/HCP23.pdf.

- Adeosun, K.P.; Greene, M.; Oosterveer, P. Informal ready-to-eat food vending: A social practice perspective on urban food provisioning in Nigeria. Food Security 2022, 14(3), 763–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crush, J.; Kazembe, L.; Nickanor, N. Opportunity and survival in the urban informal food sector of Namibia. Businesses 2023, 3(1), 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickanor, N.; Kazembe, L.; Crush, J.; Shinyemba, T. Inclusive growth and the informal sector in Windhoek, Namibia. Hungry Cities Partnership Report No. 23, Cape Town and Waterloo. 2021. https://hungrycities.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/HCP23.pdf.

- Raimundo, I.; Wagner, J.; Crush, J.; Abrahamo, E.; McCordic, C. Inclusive Growth and Informal Vending in Maputo’s Markets. Hungry Cities Partnership Report No. 18, Cape Town and Waterloo, 2020. https://hungrycities.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/HCP18-2.pdf.

- Ramirez, T.; Vanek, J. Street vendors and market traders in 12 countries: A statistical profile. WEIGO Statistical Brief No. 40, WIEGO. 2024. https://www.wiego.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/wiego-statistics-brief-no-40.pdf.

- Ramasamy, L. Challenges and opportunities of women participating in the informal sector in Malaysia: A case on women street vendors in Penang. International Academic Institute for Science and Technology 2018, 5(3), 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chege, C.G.K.; Mbugua, M.; Onyango, K.; Lundy, M. Keeping food on the table: Urban food environments in Nairobi under COVID-19; International Centre for Tropical Agriculture (CIAT): Nairobi, 2021; https://cgspace.cgiar.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/7a50d543-dac6-4780-bba2-caac9c3b0313/content.

- Kawarazuka, N.; Béné, C.; Prain, G. Adapting to a new urbanizing environment: Gendered strategies of Hanoi’s street food vendors. Environment & Urbanization 2017, 30(1), 233–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khumalo, N.; Ntini, E. The challenges faced by women street food vendors in Warwick Junction, Durban. African Journal of Gender, Society and Development 2021, 10(3), 263–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zingkhai, M.; Anand, S. Women food vendors in the hills of Manipur: An empirical study, New Delhi. Asian Review of Social Sciences 2019, 8(1), 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aberman, N.; Meerman, J.; van de Riet, A. Integrating gender into the governance of urban food systems for improved nutrition; Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition (GAIN). Working Paper No. 25; Geneva, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odhiambo, S.A.; Owuor, P.M.; Obondo, D.; Onyango, J.A.; Kiplagat, J.; Onyango, E. Informal female food vendors, COVID-19, and post-pandemic recovery in Kisumu, Kenya. MiFOOD Paper 38, Waterloo. 2025. https://mifood.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/MiFOOD38.pdf.

- Chen, M.; Rogan, M.; Sen, K. (Eds.) COVID-19 and the Informal Economy: Impact, Recovery, and the Future; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, L. Invisible work, visible impacts: Gender, migrants, and informal food trade amid the COVID-19 pandemic in the Global South. MiFOOD Paper No. 27, Waterloo. 2024. https://mifood.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/MiFOOD27.pdf.

- Skinner, C.; Watson, V. Planning and informal food traders under COVID-19: The South African case. The Town Planning Review 2021, 91(6), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owuor, S. The impact of COVID-19 containment measures on urban-rural linkages: A study on the flow of food and people in the urban-rural nexus in Kenya. In Handbook of Research on Migration, COVID-19 and Cities; Rajan, S.I, Ed.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, 2025; pp. 556–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bene, C. Resilience of local food systems and links to food security – A review of some important concepts in the context of COVID-19 and other shocks. Food Security 2020, 12, 805–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Food supply chains and COVID-19: Impacts and policy lessons. OECD. 2020. https://www.oecd.org/content/dam/oecd/en/publications/reports/2020/06/food-supply-chains-and-covid-19-impacts-and-policy-lessons_62c97266/71b57aea-en.pdf.

- United Nations (UN). COVID-19 in an urban world. Policy Brief. 2020. https://unsdg.un.org/sites/default/files/2020-07/sg_policy_brief_covid_urban_world.pdf.

- Joshi, N.; Lopus, S.; Hannah, S.; Ernst, K.; Kilungo, A.; Opiyo, R.; Ngayu, M.; Davies, J.; Evans, T. COVID-19 lockdowns: Employment and business disruptions, water access and hygiene practices in Nairobi’s informal settlements. Soc Sci Med 2022, 308, 115191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimani-Murage, E.W.; Osogo, D.; Nyamasege, C.K.; et al. COVID- 19 and human right to food: Lived experiences of the urban poor in Kenya with the impacts of government’s response measures, a participatory qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 1399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinchoff, J.; Austrian, K.; Rajshekhar, N; et al. Gendered economic, social and health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and mitigation policies in Kenya: Evidence from a prospective cohort survey in Nairobi informal settlements. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e042749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaife, M.; van Zandvoort, K.; Gimma, A.; Shah, K.; et al. The impact of COVID-19 control measures on social contacts and transmission in Kenyan informal settlements. BMC Medicine 2020, 18(1), 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, R.; Rizvi Jafree, S. Empowered by survival: Women street vendors in Pakistan’s informal patriarchal economy. Development in Practice 2025, 35(5), 834–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyn, N.P.; Mchiza, Z.; Hill, J.; Davids, Y.D.; Venter, I.; Hinrichsen, E.; Opperman, M.; Rumbelow, J.; Jacobs, P. Nutritional contribution of street foods to the diet of people in developing countries: A systematic review. Public Health Nutr. 2014, 17, 1363–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameye, H.; Hulsen, V.; Glatzel, K.; Laar, A.; Qaim, M. Urbanizing food environments in Africa: Challenges and opportunities for improving accessibility, affordability, convenience, and desirability of healthy diets. Food Policy 2025, 137, 102981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, I.D.; van Liere, M.J.; de Brauw, A.; et al. Reverse thinking: Taking a healthy diet perspective towards food systems transformations. Food Sec 2021, 13, 1497–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, S.; Muunda, E.; Ahlberg, S.; Blackmore, E.; Grace, D. Beyond food safety: Socio-economic effects of training informal dairy vendors in Kenya. Global Food Security 2018, 18, 86–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karl, J.; Fieve, J.; Chrysostome, E. Credit cooperative lending loans as challenges and opportunities for women entrepreneurship in Africa: Evidence from Ghana. Journal of African Business 2022, 25(1), 94–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitau, R.; Mugisha Baine, E.M.; Ninsiima, R.; Chelang’a, N.C.; Korir, E.; Wekesa, B.; Harawa, P.P.; Shashi, N.I. Gendered barriers faced by food vendors in providing low income consumers with safe, affordable, and nutritious foods: Evidence from urban markets in Kenya and Uganda [version 1]. VeriXiv 2025, 2, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeola, O.; Igwe, P.A.; Evans, O. Women economic empowerment and post-pandemic recovery in Africa: Normalising the ‘un-normal’ outcome of COVID-19. In Gendered perspectives on COVID-19 recovery in Africa: Towards sustainable development; Adeola, O, Ed.; Springer Nature: Switzerland, 2021; pp. 305–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbakary, H.; Kilamlya, J. Role of microfinance service as an approach to women economic empowerment in Tanzania: Experience from women food vendors in Shinyanga Municipal. American Journal of Youth and Women Empowerment 2024, 3(1), 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owuor, S. Inclusive growth and informal food vending in Nairobi, Kenya. Hungry Cities Report No. 21, Cape Town and Waterloo. 2020. https://hungrycities.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/HCP21.pdf.

- Donga, G.; Chimucheka, T. Challenges and opportunities of the COVID-19 pandemic on women entrepreneurs operating in the informal food sector: A post COVID-19 analyses. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science (2147–4478) 2024, 13(2), 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rwafa-Ponela, T.; Goldstein, S.; Kruger, P.; Erzse, A.; Abdool Karim, S.; Hofman, K. Urban informal food traders: A rapid qualitative study of COVID-19 lockdown measures in South Africa. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |