Submitted:

19 January 2026

Posted:

20 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Vladimir Potočnjak’s Architectural Career from the Typological Point of View

3.1. The Prelude: Education

3.2. The Early Period: Apprenticing to Adolf Loos, Ernst May and Hugo Ehrlich (1926-1931)

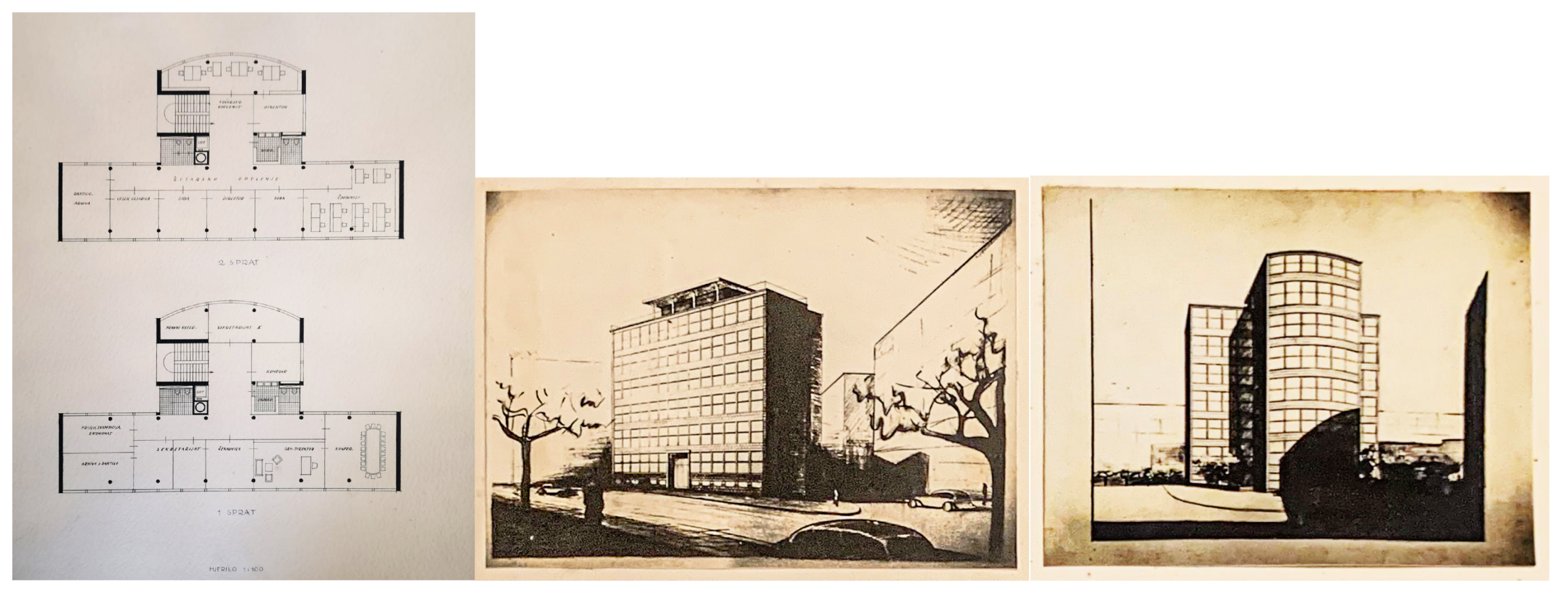

3.3. The Main Period: Licensed Architectural Engineer (1931-1945)

3.3.1. Apartment Houses

3.3.2. Villas

3.3.3. Industrial and Other Facilities

3.3.4. Publications

3.3.5. Work in the Directorial Bodies of Professional Organizations

3.3.6. Professorship at the University of Zagreb’s School of Technology during the Independent State of Croatia

3.3.7. Standardization

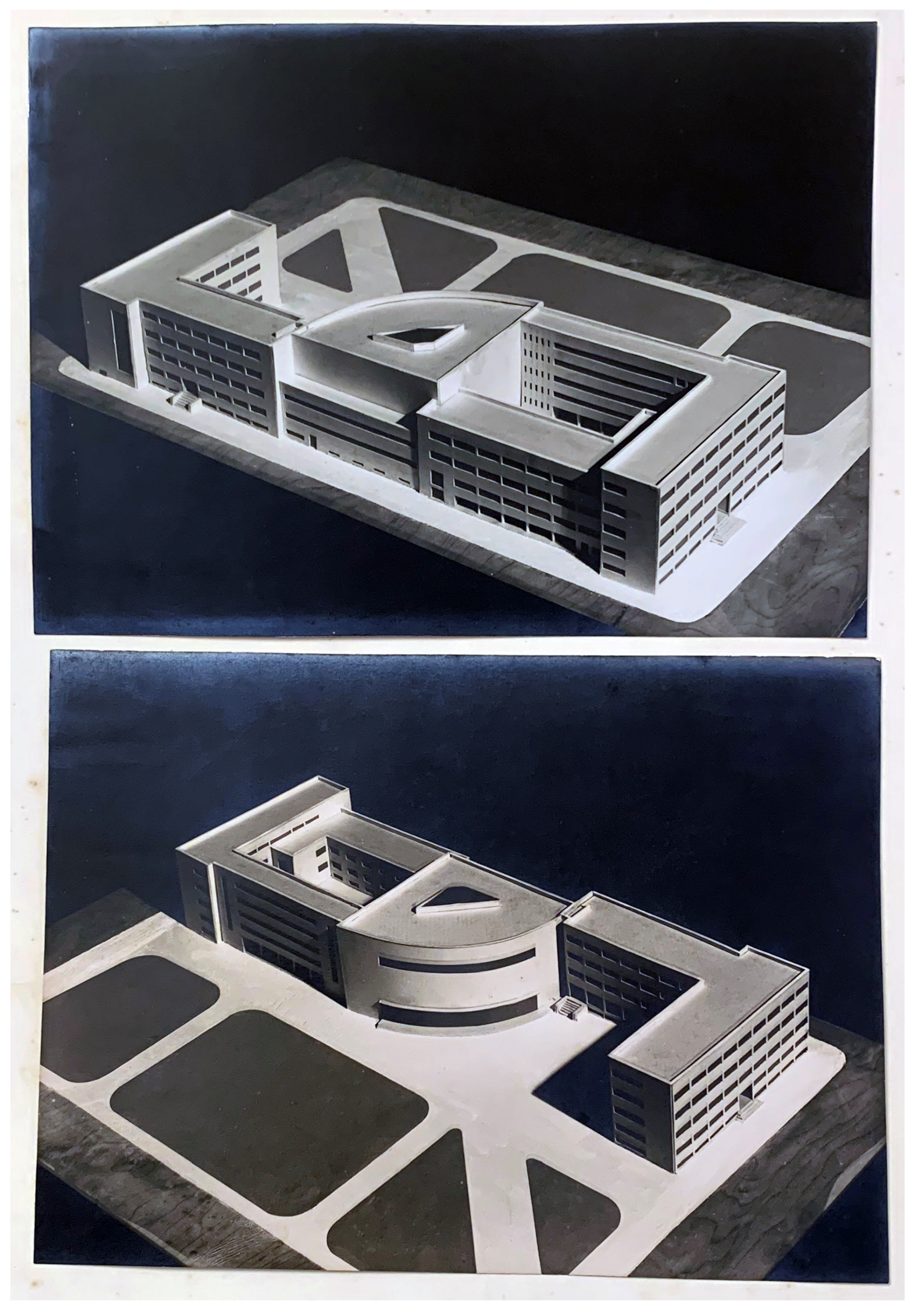

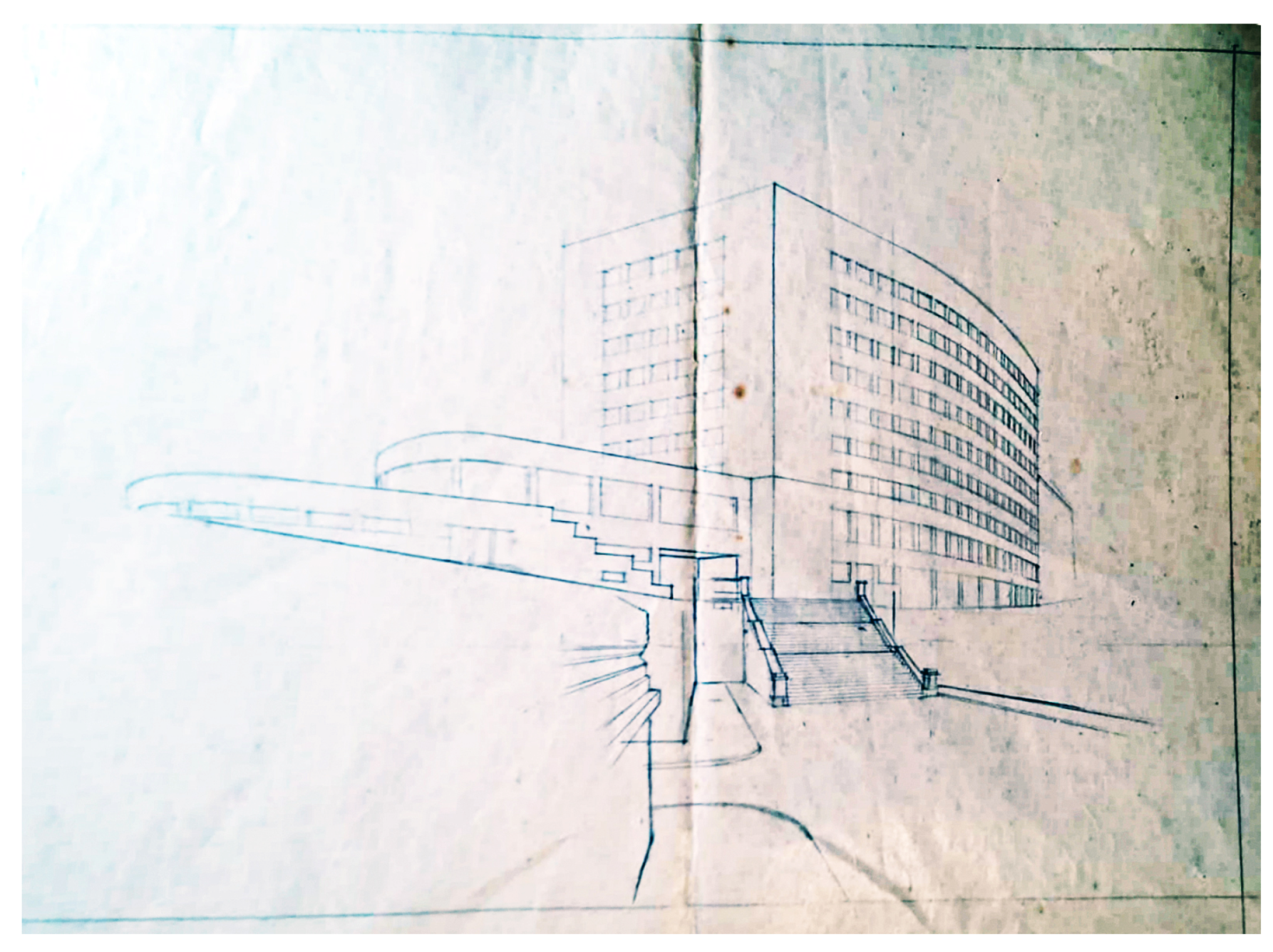

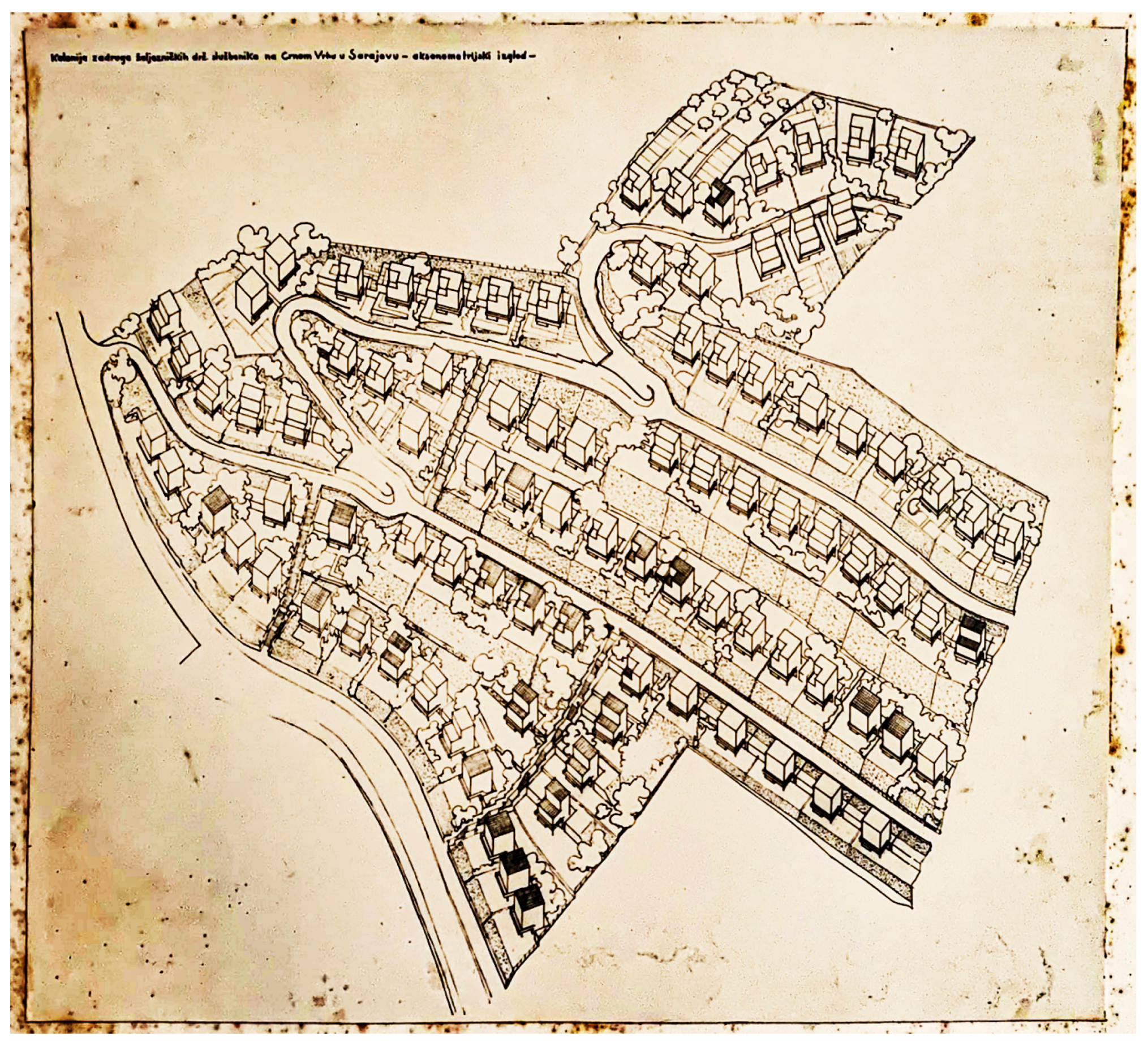

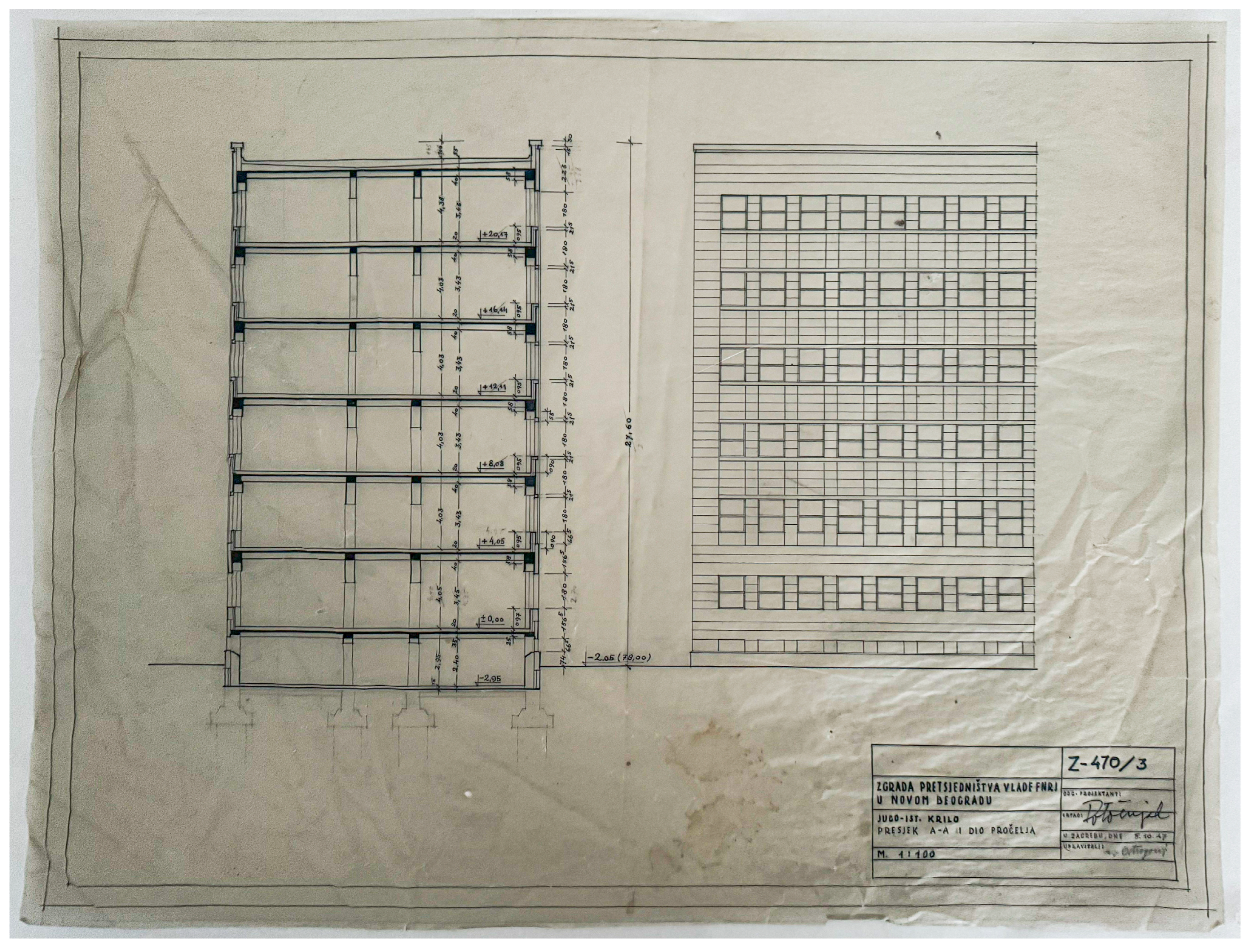

3.4. The Late Period: People’s Republic of Croatia’s Stately Design and Planning Institute (1945-1952)

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Appendix A. Comprehensive List of Projects, Realizations and Publications [78]

| 1 | According to the Book of Matura Exam Records, No. 38 [/1922], pages 557 recto & verso, on July 3rd, 2022, he was born on January 17th, 1904. Yet, according to the uncertified transcript of his 2nd Stately Exam / Diploma Certificate, No. 46 [/1926], he was born on January 4th, 1904. I presume that his birth date on the Diploma Certificate was erroneously rewritten from the original, because in other documents, submitted as the evidentiary support to his application for professorship at the School of Technology, Croatian University in Zagreb in May 1942, his date of birth was stated on January 17th, 1904. |

| 2 | In the DAZG / State Archives Zagreb (Državni Arhiv u Zagrebu), 29 Opatička St, Zagreb, the “Vladimir Potočnjak personal file” as contractual engineer at the Zagreb’s City Construction Office [a city official] does not exist. |

| 3 | The archival documentation of this 10 villas probably exist, although it is necessary to thoroughly research all corresponding archives in the wider Rijeka area. The archival documentation of villa Muačević should be placed in the DAO / State Archives Osijek. |

References

- Anon. Arhitekt Vladimir Potočnjak [Obituary]. Arhitektura 1952, 6, 27-31.

- Vrkljan, Z. Obljetnice: Dipl. inž. arh. Vladimir Potočnjak (1904-1952) [Anniversaries: Dipl. Eng. Arch. Vladimir Potočnjak (1904-1952)]. Čovjek i prostor, 1977, 24, , p. 30.

- Vrkljan, Z. Sjećanja [Memories]; Publisher: Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Zagreb, Croatia, 1995; pp. 144-145.

- Premerl, T. Potočnjak, Vladimir. In Likovna Enciklopedija Jugoslavije 2 K-Ren.; Domljan, Ž., Šercar, H., Eds.; Publisher: Jugoslavenski Leksikografski Zavod “Miroslav Krleža”, Zagreb, Croatia, Yugoslavia, 1987; Volume 2, pp. 624.

- Premerl, T. Potočnjak, Vladimir. In Enciklopedija Hrvatske Umjetnosti 2 Novi-Ž.; Domljan, Ž., Ed.; Publisher: Leksikografski Zavod “Miroslav Krleža”, Zagreb, Croatia, 1996; Volume 2, pp. 85.

- Blažić, M. Potočnjak, Vladimir. Hrvatska tehnička enciklopedija. Available online: https://tehnika.lzmk.hr/potocnjak-vladimir/ (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Širola, B. S.; Kreković, M. Gradnja tvornice aluminiuma a.d. u Lozovcu kraj Šibenika (sa slikama) [The construction of the aluminum factory Co. in Lozovac near Šibenik (with pictures)]. Građevinski Vjesnik 1937, 6, 165-168.

- Steinmann, E. Buduća izgradnja Griča [The future construction of Grič]. Tehnički Vjesnik 1943, 3, 369-375.

- Kahle, D. Architect Zlatko Neumann: Buildings and Projects between the World Wars. Prostor 2015, 23, 28-41. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279531945_Architect_Zlatko_Neumann_Buildings_and_Projects_between_the_World_Wars (accessed on 17 August 2021).

- Kahle, D. Architect Zlatko Neumann: Works after the Second World War (1945-1963). Prostor 2016, 24, 172-187. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329438932_Arhitekt_Zlatko_Neumann_Djela_nakon_Drugoga_svjetskog_rata_1945-1963 (accessed on 17 August 2021). [CrossRef]

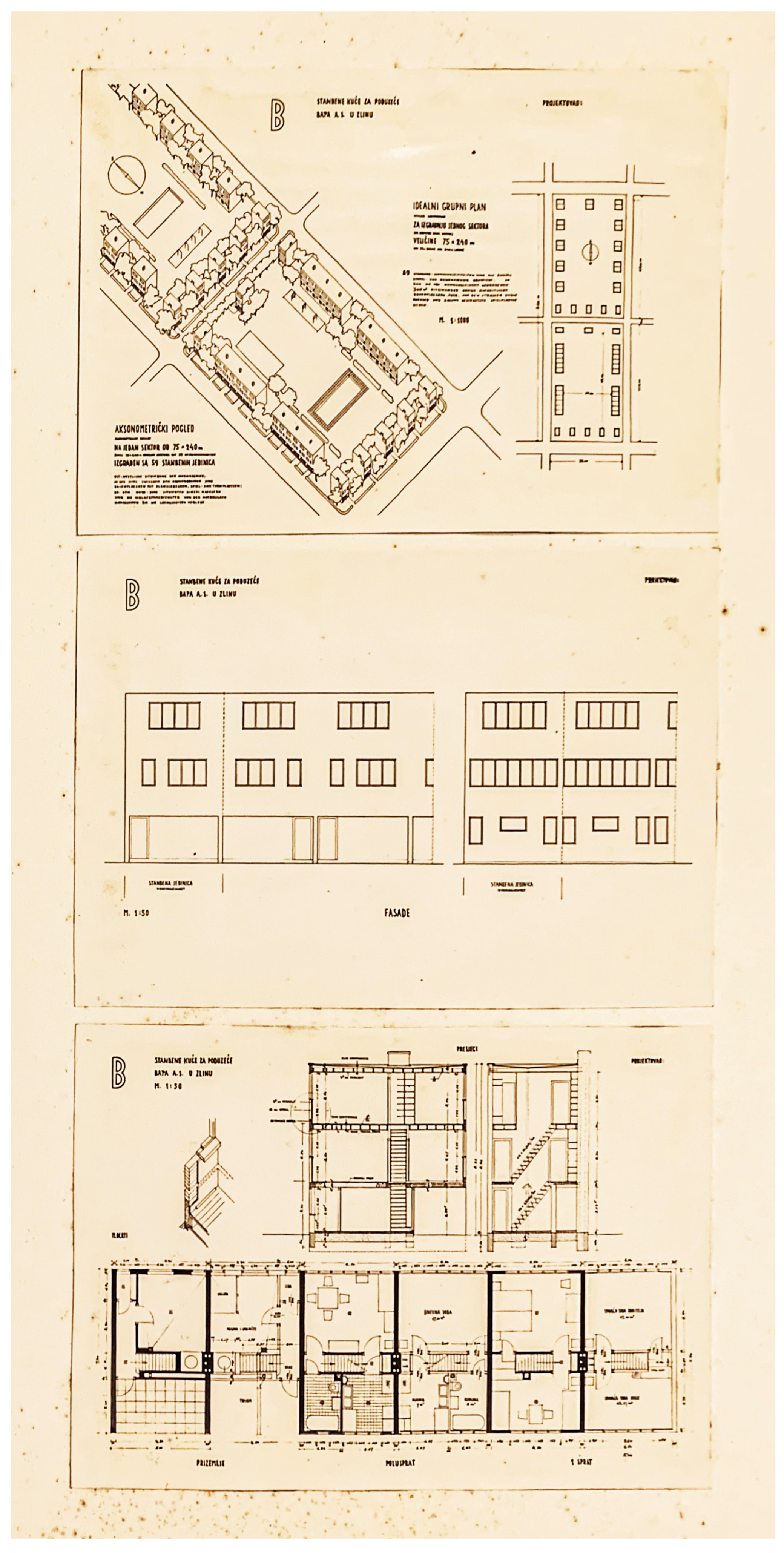

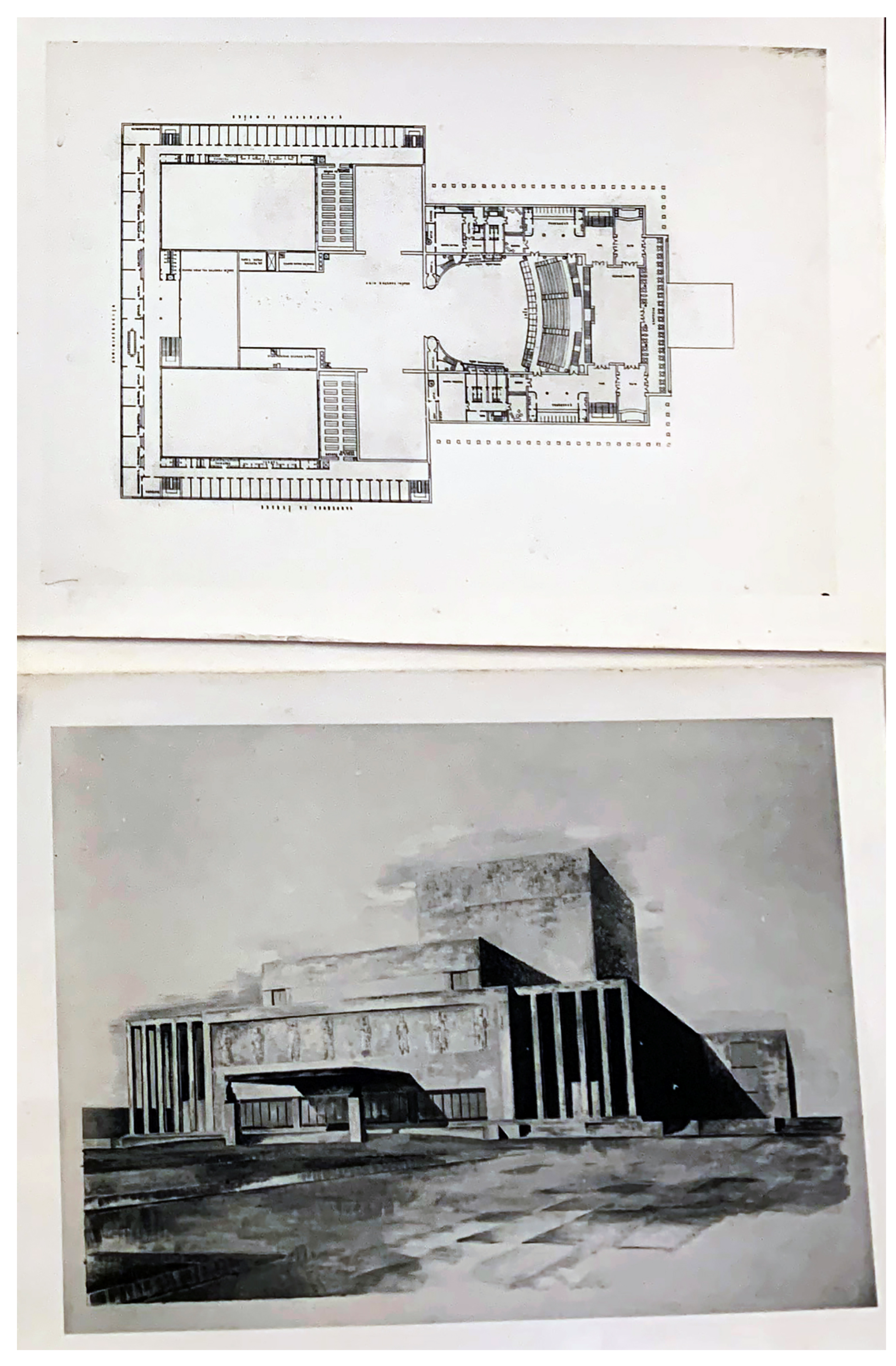

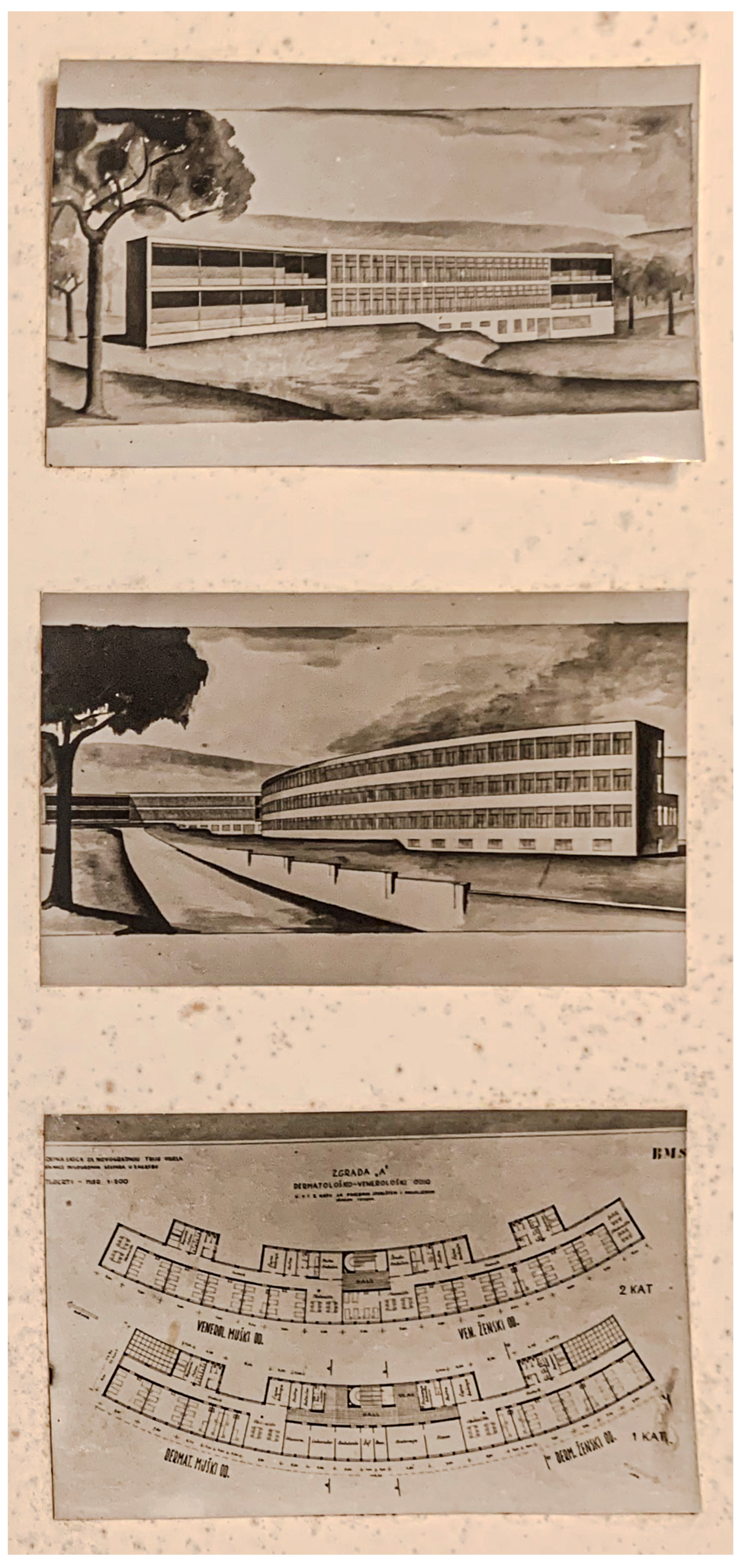

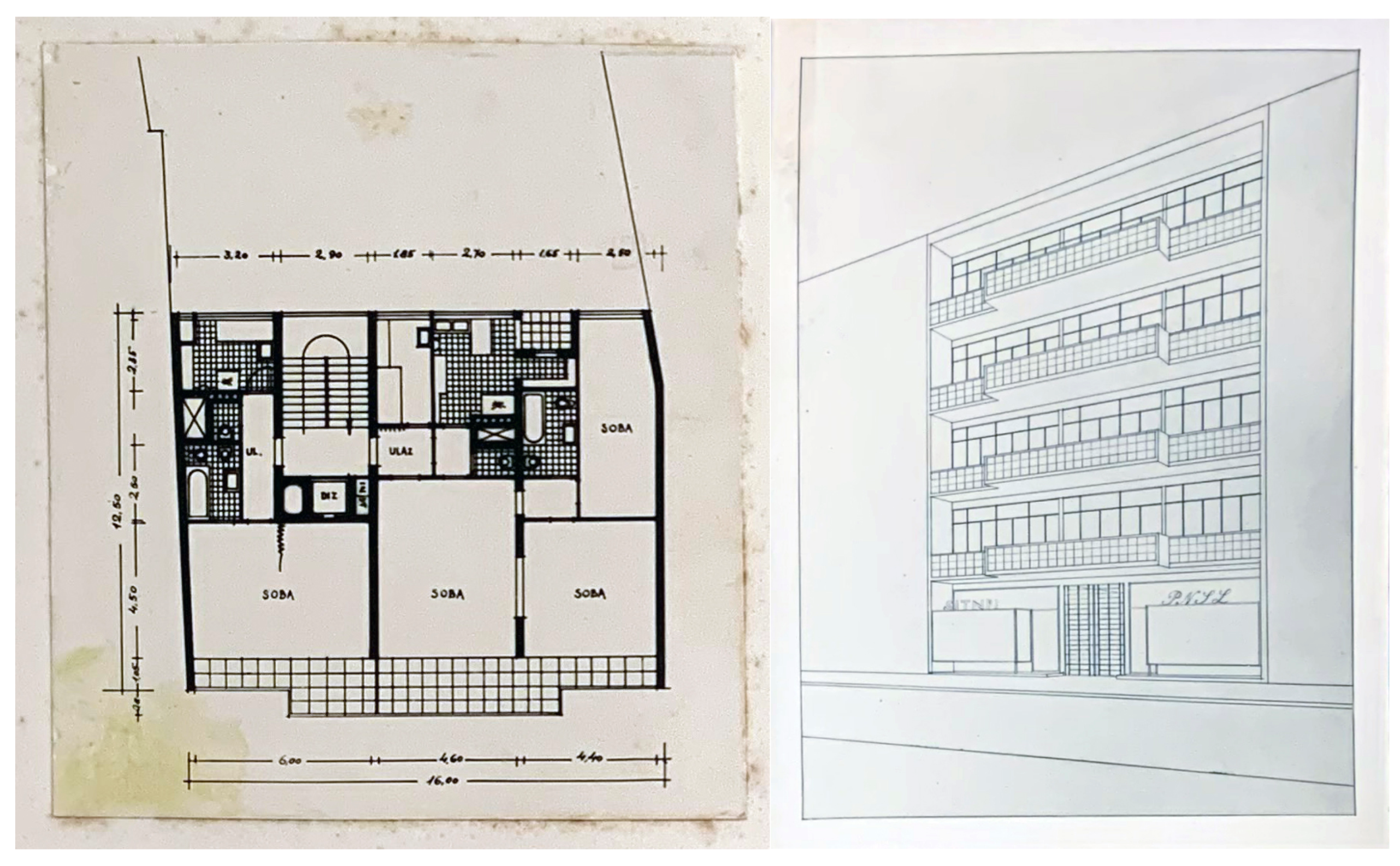

- Potočnjak, V. [Vladimir Potočnjak drawings collection: A. The Map.] 1942, unpublished (in possession of the article’s author).

- Potočnjak, V. [Vladimir Potočnjak drawings collection: B. Drawings in folio.] 1932-1952, unpublished (in possession of the article’s author).

- Potočnjak, V. [ZBOR NACRTA U APZ-u – Vladimir Potočnjak], 23. 2. 1951, aukcije.hr . Was available online: https://www.aukcije.hr/prodaja/kolekcionarstvo/Stari-dokumenti-i-fotografije/367/oglas/ZBOR-NACRTA-U-APZ-u-Vladimir-Poto%C4%8Dnjak/2763464/ (accessed on 17 August 2021, page vanished, the author created the captured site’s PDF file on 13:46:18).

- Durm, J. Die Baukunst der Griechen, 3rd ed. [Handbuch der Architektur, II. Teil, 1. Band]; Publisher: Alfred Kröner Leipzig, Germany, 1910; pp. 1–ff. [stamped: ARH. VLADIMIR POTOČNJAK, in author’s library].

- Durm, J. Die Baukunst der Etrusker, Die Baukunst der Römer, 2nd ed. [Handbuch der Architektur, II. Teil, 2. Band]; Publisher: Arnold Bergsträsser Stuttgart, Germany, 1905; pp. 1–ff. [stamped: ARH. VLADIMIR POTOČNJAK, in author’s library].

- Schumacher, F. Zeitfragen der Architektur, Erstes und zweites Tausend.; Publisher: Eugen Diederichs Jena, Germany, 1929; pp. 1–ff. [signed: Volodja [Vladimir] Potočnjak, in author’s library].

- Vladimir Potočnjak’s MEC / The Maturity Exam Certificate, no. 38 / 3. 7. 1922; in the DAZG / State Archives Zagreb (Državni Arhiv u Zagrebu), 29 Opatička St, Zagreb.

- Vladimir Potočnjak’s 2nd Stately Exam / Diploma Certificate, no. 46 / 25. 6. 1926; in the Vladimir Potočnjak’s personal file at the Faculty of Architecture, University of Zagreb.

- Domljan, Ž. Arhitekt Ehrlich.; Društvo povjesničara umjetnosti Hrvatske: Zagreb, Yugoslavia, 1979; p. 110.

- Kahle, D. THE “WORKERS’ INSTITUTIONS’ PALACE COMPETITION” IN ZAGREB AND ITS AFTERMATH. In Proceedings of the 13th / 13. Architecture in Perspective 2021 / Architektura v perspektivě 2021, Ostrava, Czech Republic, Date of Conference (29.-30. 09. 2021). Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/355928346_The_Workers’_Institutions’_Palace_Competition_in_Zagreb_and_its_aftermath (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Ehrlich, H. Gradnja Tehničkog fakulteta Sveučilišta Kraljevine Jugoslavije [The construction of the Faculty of Technology of the University of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia]. Godišnjak Sveučilišta u Zagrebu, 1929, pp. 1114-17.

- Kahle, D. Zagrebačka ugrađena najamna kuća u razdoblju od 1928. do 1934. godine [Built-in Apartment Houses in Zagreb between 1928 and 1934]. Prostor 2002, 10, 162, Figure 15-16. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/350410742_Built-in_Apartment_Houses_in_Zagreb_between_1928_and_1934 (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Kahle, D. Die Liste der gefundenen Projekte und ausgeführten Bauten des Architekten Zvonimir Pavešić (1907-1978). [2025] (A private research project submitted to the Architect’s granddaughters Mrs. Sanja Pavešić-Hirschfeld and Mrs. Zinka Forth).

- Vladimir Potočnjak’s Statement on 18. 6. 1942; in the Vladimir Potočnjak’s personal file at the Faculty of Architecture, University of Zagreb.

- Kahle, D. THE COMPARISON OF CONSECUTIVE ARCHITECTURAL LEGISLATIONS IN CROATIAN LANDS FROM THE HABSBURG EMPIRE UNTIL THE INDEPENDENT STATE OF CROATIA. In Proceedings of the Art and the State in Modern Central Europe (18th – 21st Century), Zagreb, Croatia, Date of Conference (Day Month Year). Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/385300754_THE_COMPARISON_OF_CONSECUTIVE_ARCHITECTURAL_LEGISLATIONS_IN_CROATIAN_LANDS_FROM_THE_HABSBURG_EMPIRE_UNTIL_THE_INDEPENDENT_STATE_OF_CROATIA (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Vladimir Potočnjak’s Curriculum Vitae on 11. 5. 1942; in the Vladimir Potočnjak’s personal file at the Faculty of Architecture, University of Zagreb.

- Vrkljan, Z. Sjećanja [Memories]; Publisher: Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Zagreb, Croatia, 1995; pp. 60.

- Vrkljan, Z. Sjećanja [Memories]; Publisher: Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Zagreb, Croatia, 1995; pp. 61.

- Mladen Lorković. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mladen_Lorkovi%C4%87 (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Vergabe- und Vertragsordnung für Bauleistungen. Available online, in German: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vergabe-_und_Vertragsordnung_f%C3%BCr_Bauleistungen (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Kolacio, Z. In memoriam BRANKO TUČKORIĆ (1910-1971). Čovjek i prostor 1972, 4 [228], 25. Available online, in Croatian: https://arhitekti.eindigo.net/?pr=iiif.v.a&id=10590&tify={%22pages%22:[25],%22panX%22:0.204,%22panY%22:0.982,%22view%22:%22info%22,%22zoom%22:0.471} (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- Kahle, D. Architect Zlatko Neumann: Works after the Second World War (1945-1963), chapter “THE PERIOD FROM 1945 TO 1954”. Prostor 2016, 24, 176-178.

- Kahle, D. THE RISE AND FALL OF THE ZAGREB PAPER INDUSTRY 1893-2006. In Proceedings of the 12th / 12. Architecture in Perspective 2020 / Architektura v perspektivě 2020, Ostrava, Czech Republic, Date of Conference (14.-15. 10. 2020). Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/347380847_The_Rise_and_Fall_of_the_Zagreb_Paper_Industry_1893-2006 (accessed on 7 January 2026).

- State Anti-Fascist Council for the National Liberation of Croatia. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/State_Anti-Fascist_Council_for_the_National_Liberation_of_Croatia (accessed on 7 January 2026).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).