Submitted:

19 January 2026

Posted:

20 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Overview of GHG in Industrial Oil Sector

2.2. Pollution Levels and Carbon Footprint of Oil Companies Worldwide and in Sub-Saharan Africa

2.3. Empirical Studies on Emissions Reduction in African Industrial Firms

2.4. Corporate Strategies for GHG Emissions Reduction

2.5. Specific Challenges in Oil-Producing Sub-Saharan African Countries

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design and Conceptual Framework

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Analytical Framework

4. Results

4.1. Breakdown of Emissions by Activity/Process

4.2. Breakdown of Emissions by Activity/Process

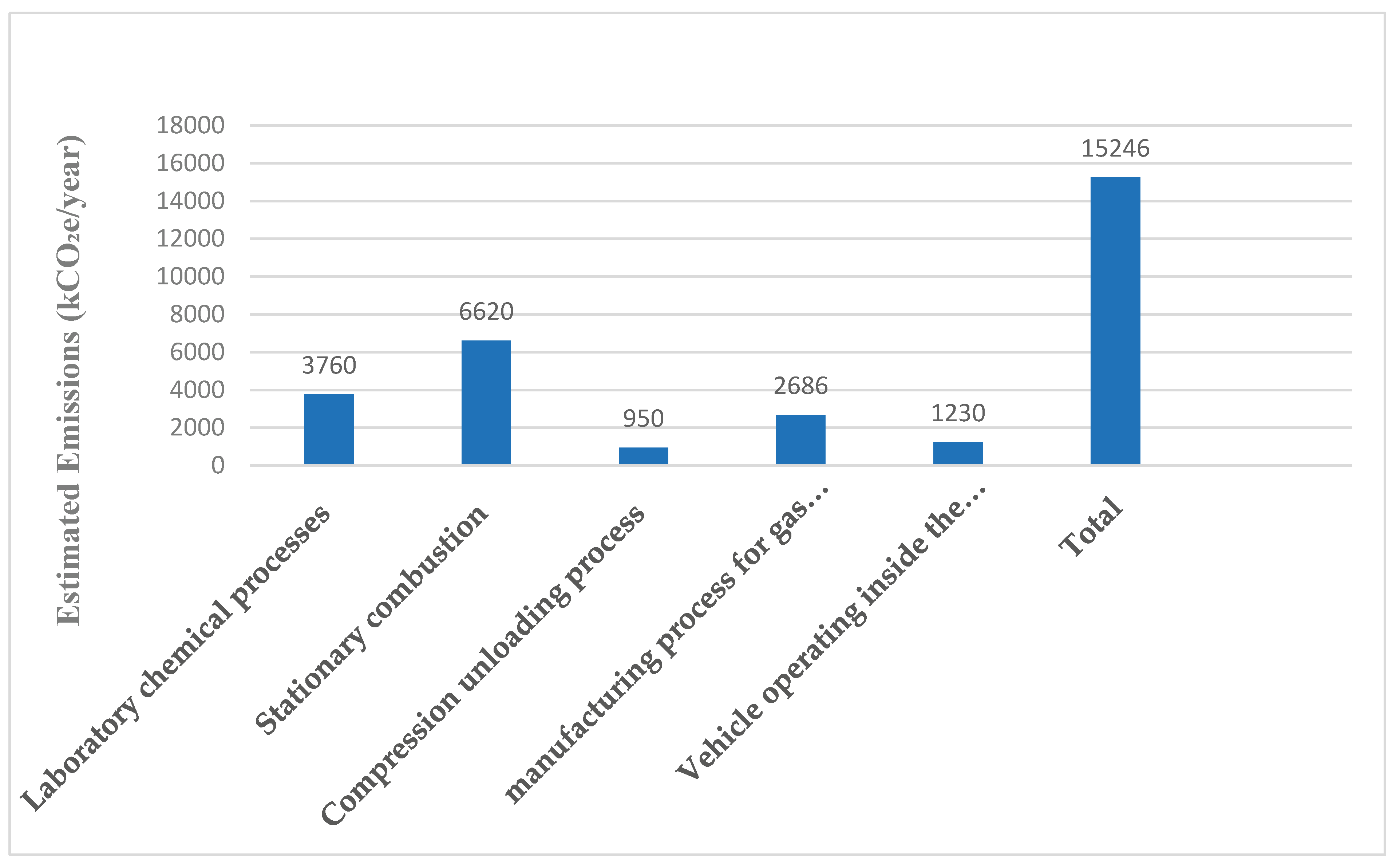

4.2.1. Scope 1

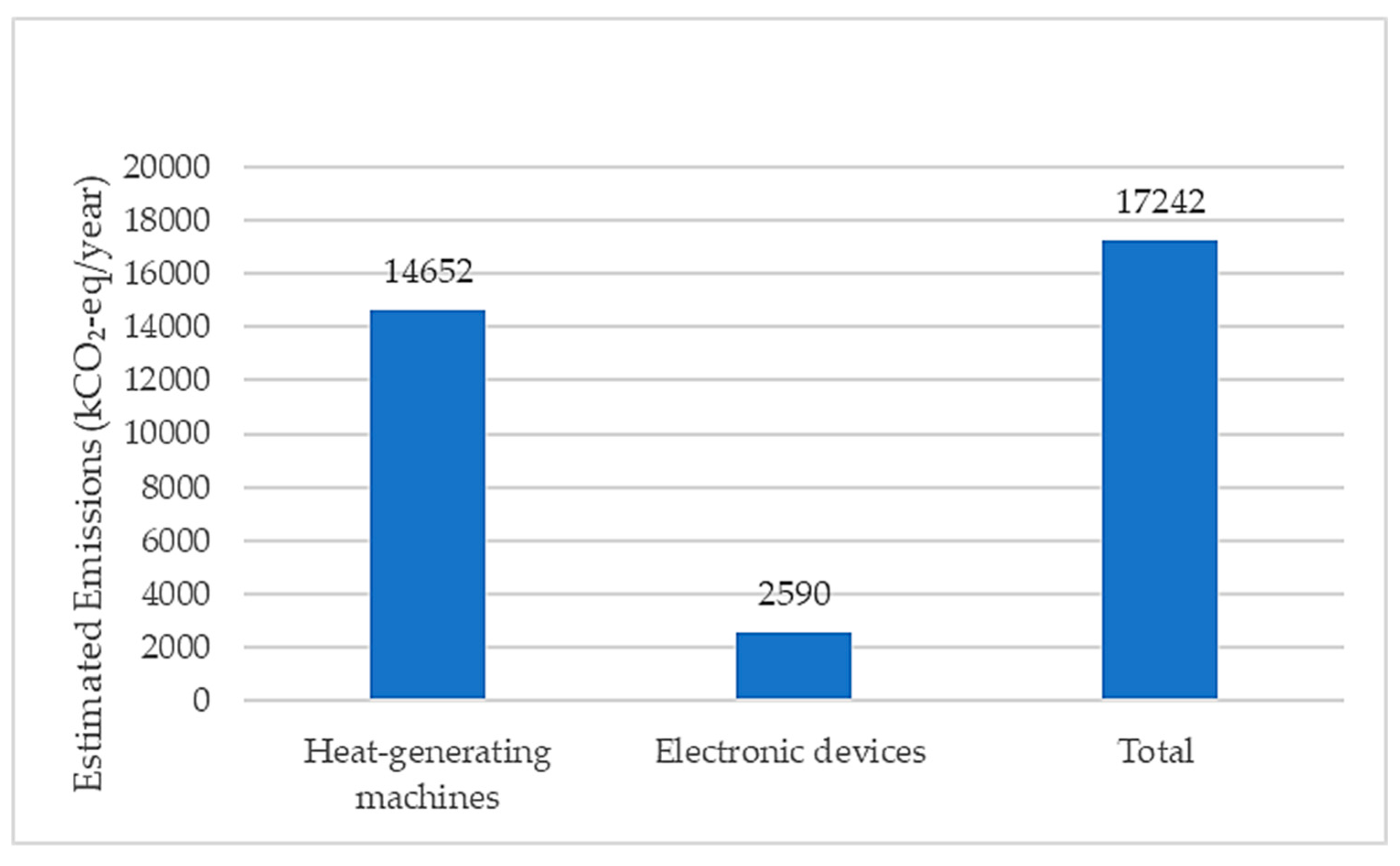

4.2.2. Scope 2

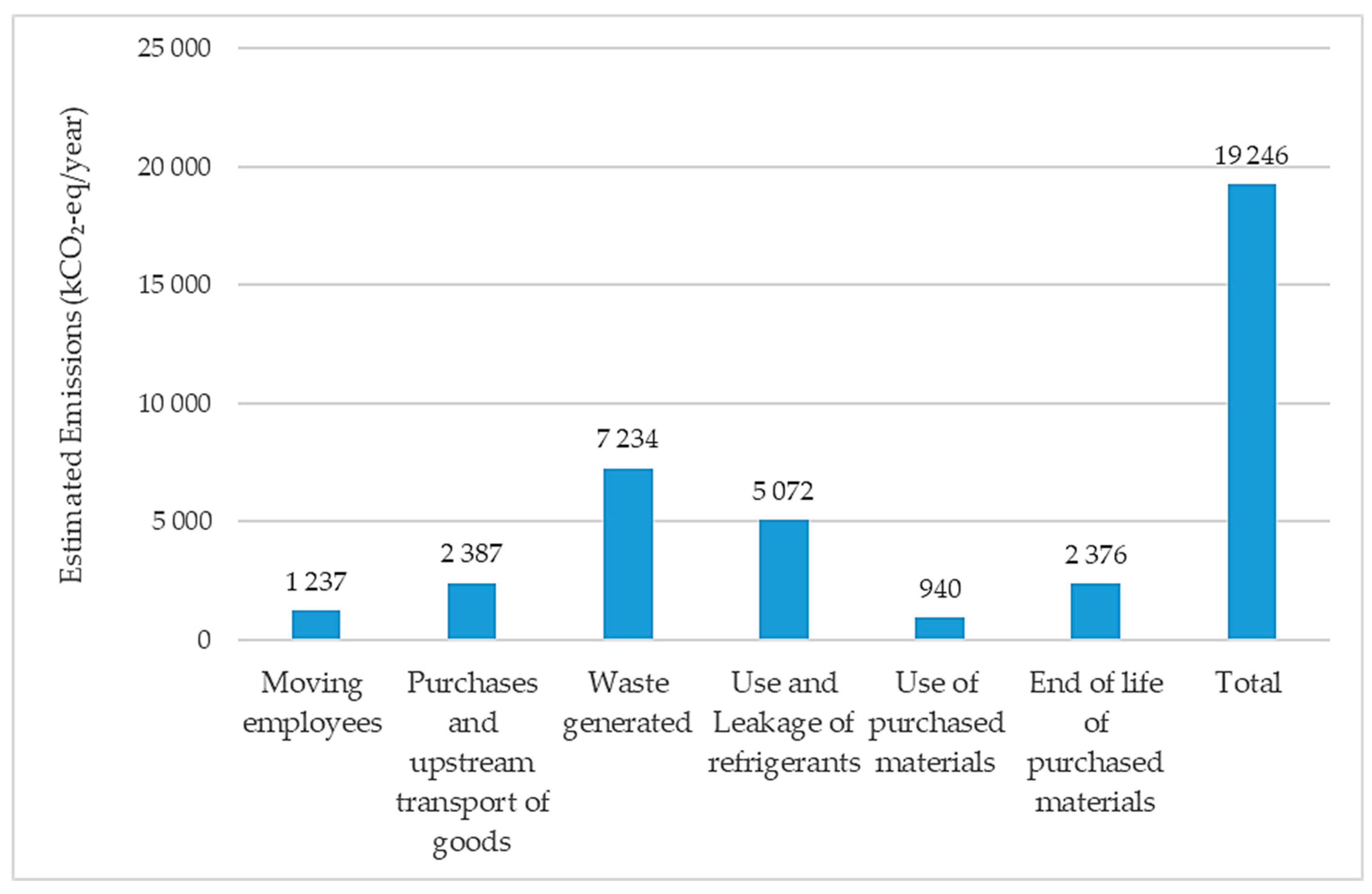

4.2.3. Scope 3

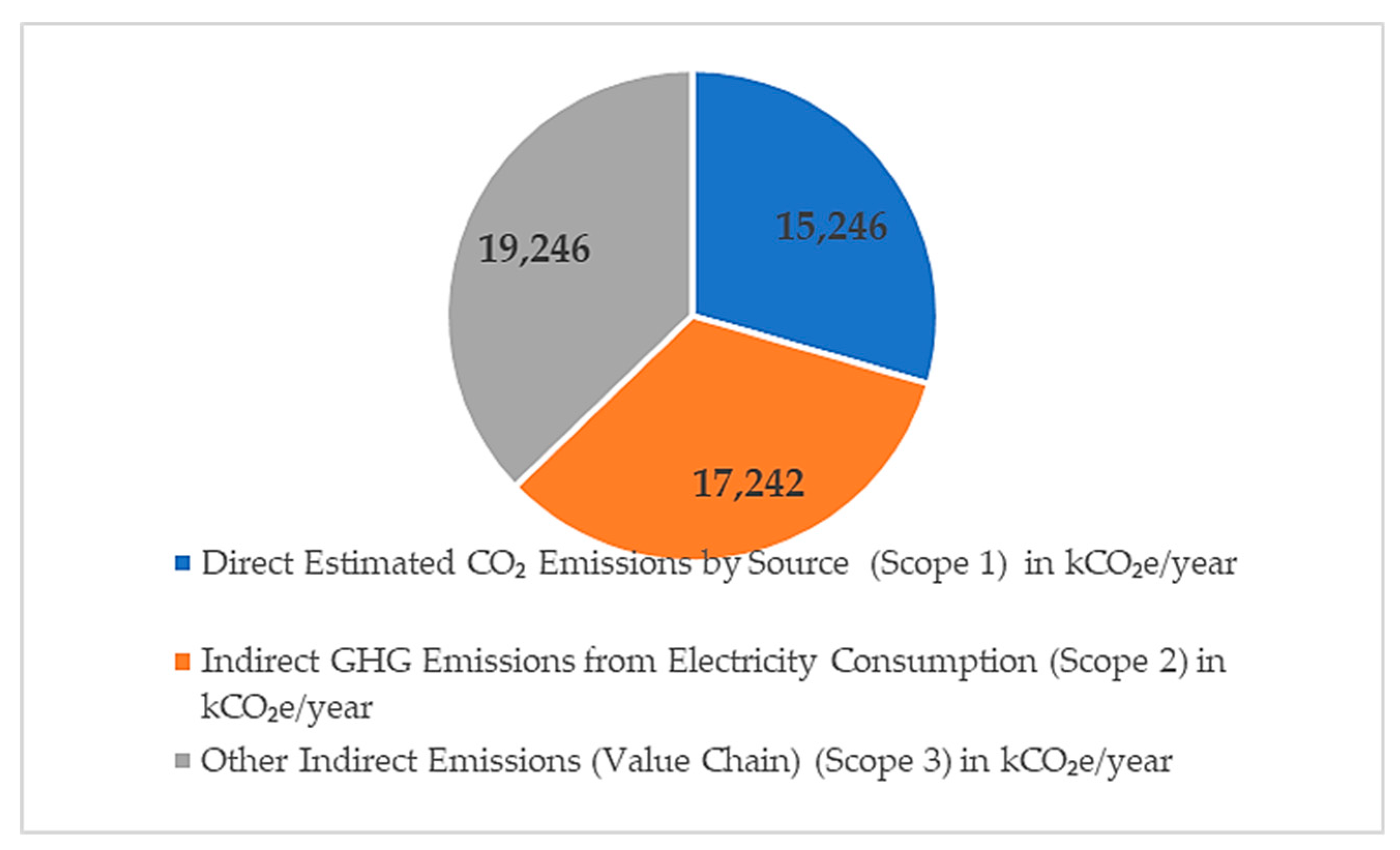

- Scope 1 (Direct emissions): 15,246 kCO₂-eq/year (approximately 29%),

- Scope 2 (Indirect emissions from purchased electricity): 17,242 kCO₂-eq/year (approximately 33%),

- Scope 3 (Other indirect emissions from the value chain): 19,246 kCO₂-eq/year (approximately 38%).

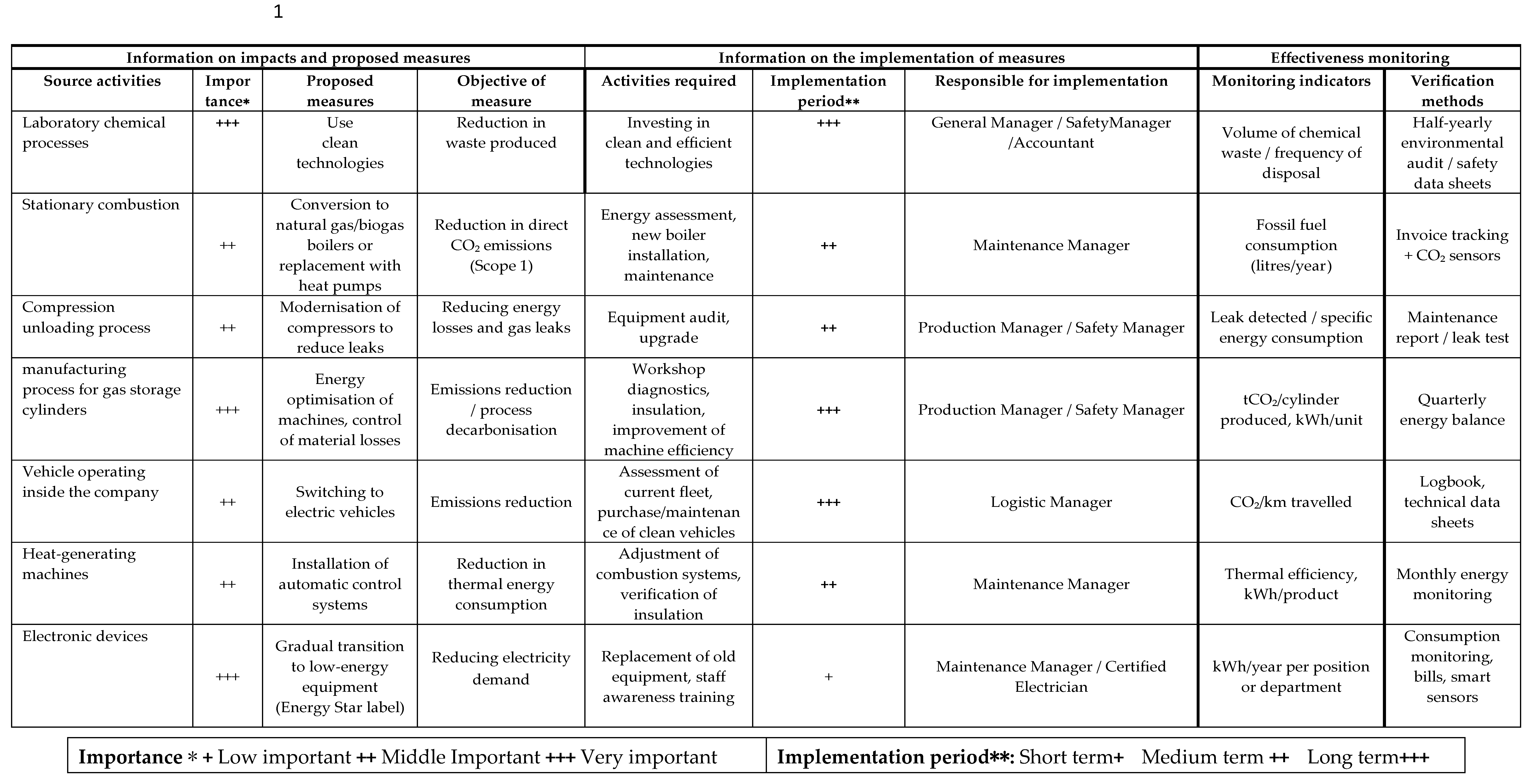

- Environmental Management Plan

- Laboratory Chemical Processes

- Stationary Combustion

- Compression Unloading Process

- Manufacturing of Gas Cylinders

- Vehicle Operation Within the Company

- Heat-Generating Machines

- Electronic Devices

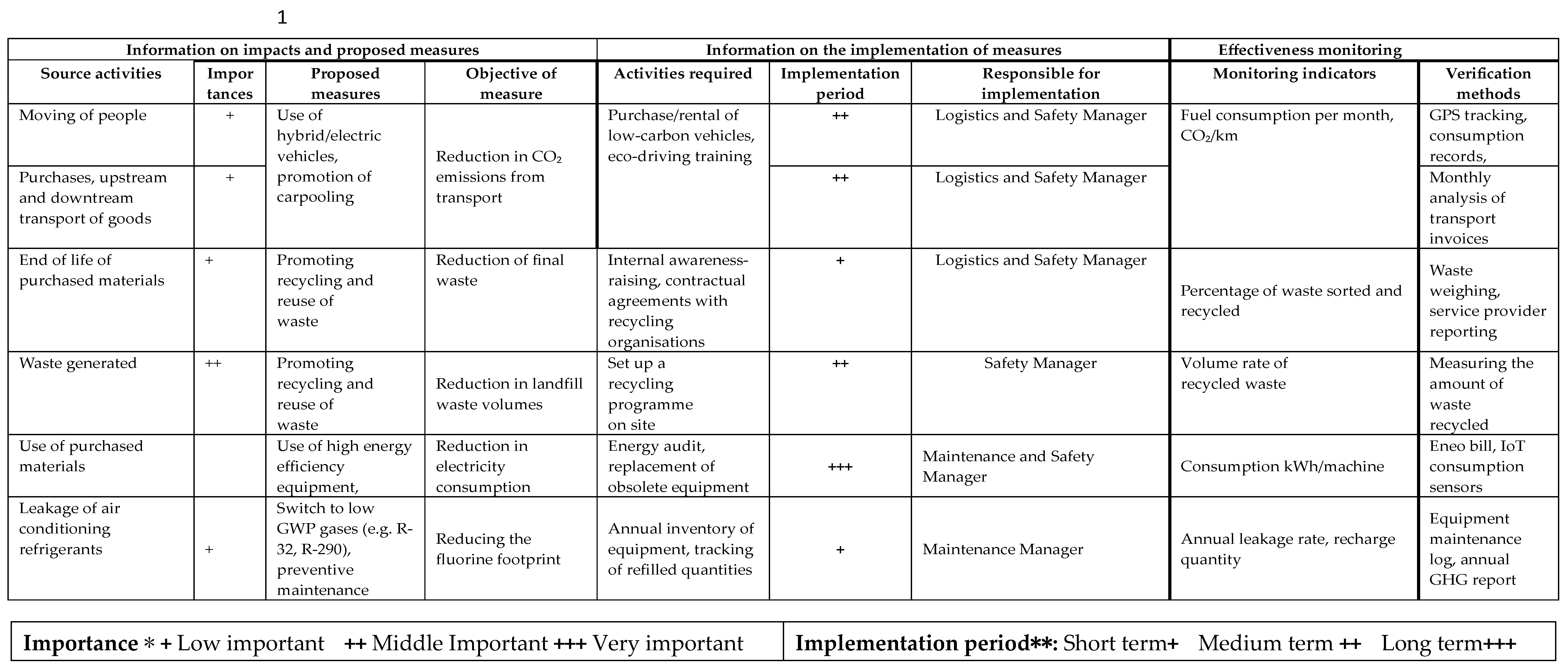

- Moving of People

- ∘

- Purchases and Transportation of Goods (Upstream/Downstream)

- ∘

- End-of-Life of Purchased Materials

- ∘

- Waste Generated

- ∘

- Use of Purchased Materials

- ∘

- Leakage of Air Conditioning Refrigerants

5. Discussion

5.1. Critical Interpretation of Results and Their Local Significance

5.2. Regional and African Implications of BOCOM Petroleum’s Decarbonisation Strategy

5.3. Alignment with Cameroon’s Legal and Institutional Frameworks: Current Status and Long-Term Projections

5.4. Strategic and Environmental Advantages of Decarbonising Industrial Enterprises in Sub-Saharan Africa

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Declaration of competing interest

Declaration of funding

References

- Bot, B. V.; Axaopoulos, P. J.; Sakellariou, E. I.; Sosso, O. T.; Tamba, J. G. Economic Viability Investigation of Mixed-Biomass Briquettes Made from Agricultural Residues for Household Cooking Use. Energies 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakellariou, E. I.; Axaopoulos, P. J.; Bot, B. V.; Kavadias, K. A. First Law Comparison of a Forced-Circulation Solar Water Heating System with an Identical Thermosyphon. Energies 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopakumar, L.; Kholdorov, S.; Shamsiddinov, T. Greenhouse gases emissions: problem, global reality, and future perspectives. Agric. Towar. Net Zero Emiss. 2025, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W. Lamb, T. Wiedmann, ... J. P.-E., and U. 2021 A review of trends and drivers of greenhouse gas emissions by sector from 1990 to 2018. iopscience.iop.org 2021, 13.

- Allen, D. T. Emissions from oil and gas operations in the United States and their air quality implications. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2016, 66, 549–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudhee, K. H. Assessing climate strategies of major energy corporations and examining projections in relation to Paris Agreement objectives within the framework of sustainable energy. Unconv. Resour. 2024, 5, 100127, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byaro, M. Impacts of climate change and non-renewable energy consumption on health in sub-Saharan Africa : transmission channels and policy response. Next Res. 2025, 2, 100385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørreime, H. B. The Current Role of Western Development Actors as Knowledge and Policy Providers: The Making of Good Governance of Natural Gas Resources in Tanzania. Forum Dev. Stud. 2024, 52, 81–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- C. Assembleée nationale, Loi N ° 96 / 12 Du 5 Aout 1996 Portant Loi-Cadre Relative a La Gestion De L ’ Environnement. 1996, p. 21.

- Ayuketah, Y.; Gyamfi, S.; Diawuo, F. A.; Dagoumas, A. S. A techno-economic and environmental assessment of a low-carbon power generation system in Cameroon. Energy Policy 2023, 179, no. May, 113644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INVESTIR AU CAMEROUN. Le marketeur Bocom Petroleum s.a. investit près d’un demi-milliard de FCFA dans sa 75è station-service au Cameroun. Available online: https://www.investiraucameroun.com/transport/2701-15880-le-marketeur-bocom-petroleum-s-a-investit-pres-d-un-demi-milliard-de-fcfa-dans-sa-75e-station-service-au-cameroun (accessed on 21 May 2025).

- El-Fadel, M.; Chedid, R.; Zeinati, M.; Hmaidan, W. Mitigating energy-related GHG emissions through renewable energy. Renew. Energy 2003, 28, 1257–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otene, I. J. J.; Murray, P.; Enongene, K. E. The potential reduction of carbon dioxide (Co2) emissions from gas flaring in Nigeria’s oil and gas industry through alternative productive use. Environ. - MDPI 2016, 3, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, H.; Juta, C. Taking action on climate change: Long term mitigation scenarios for South Africa.; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Owusu, M.; Lawer, V.; Adjei, E. T.; Ogbe, M. Impact of offshore petroleum extraction and ‘ocean grabbing’ on small-scale fisheries and coastal livelihoods in Ghana. Marit. Stud. 2023, 22, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idemudia, U.; Tuokuu, F. X. D.; Essah, M. The extractive industry and human rights in Africa: Lessons from the past and future directions. Resour. Policy 2022, 78, no. March, 102838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyeniyi Abe. Extractives-Industry-Law-in-Africa. J. Energy Nat. Resour. Law 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetherington, A. C.; Borrion, A. L.; Griffiths, O. G.; McManus, M. C. Use of LCA as a development tool within early research: Challenges and issues across different sectors. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2014, 19, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D. K.-E. T. in the O. and G. Industry, “Future Directions in Oil and Gas–Renewables and Energy Transition. taylorfrancis.com, 2024; 682–715.

- Chu, H.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, X.; Qiu, B.; Xu, N. Integration of carbon emission reduction policies and technologies: Research progress on carbon capture, utilization and storage technologies. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 343, 127153, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, W. Y.; Ling, T. C.; Juan, J. C.; Lee, D. J.; Chang, J. S.; Show, P. L. Biorefineries of carbon dioxide: From carbon capture and storage (CCS) to bioenergies production. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 215, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Blondeel and M. B. international, International oil companies, decarbonisation and transition risks. Handbook on oil and, 2022. Available online: https://www.elgaronline.com/edcollchap/book/9781839107559/book-part-9781839107559-34.xml (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- F. Sapnken, M. Kibong, J. T.- Heliyon, and U. 2023 Analysis of household LPG demand elasticity in Cameroon and policy implications. cell.com. 2024. Available online: https://www.cell.com/heliyon/fulltext/S2405-8440(23)03678-2 (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Lokossou, J. “Oil and the Cameroonian Economy: A Story of Unfulfilled Potential1 Léonce Ndikumana2 Hans Tino Mpenya Ayamena3,” 2025. Available online: https://peri.umass.edu/images/publication/WP618.pdf (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- SEG Baiye. Petroleum Supply Chain in Cameroon: An Exploratory Study. papers.ssrn.com. 2015. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3600785 (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Adekoya, O. Yaya; J. O.-S. C., U. Growth and growth disparities in Africa: Are differences in renewable energy use, technological advancement, and institutional reforms responsible? Struct. Chang. Econ. Dyn. 2022, 61, 265–277. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0954349X22000352. [CrossRef]

- Isbell, P. Atlantic Energy and the Changing Global Energy Flow Map; 2014; pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Hafner, M.; Raimondi, P. P. Energy and the Economy in Europe; 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paes, W. Oil Production and National Security in Sub-Saharan Africa. Oil Poicy Gulf Guinea 2004, 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, E.; Ovadia, J. S. Oil exploration and production in Sub-Saharan Africa, 1990-present: Trends and developments. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2019, 6, 593–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouedraogo, N. S. Africa energy future: Alternative scenarios and their implications for sustainable development strategies. Energy Policy 2017, 106, no. April, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Te Liew, W.; Adhitya, A.; Srinivasan, R. Sustainability trends in the process industries: A text mining-based analysis. Comput. Ind. 2014, 65, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsubo, Y.; Chapman, A. J. Assessing Corporate Vendor Selection in the Oil and Gas Industry: A Review of Green Strategies and Carbon Reduction Options. Sustain. 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schutzbach, M.; Miehe, R.; Sauer, A. Simplifying life cycle Assessment: Basic considerations for approximating product carbon footprints based on corporate carbon footprints. Ecol. Indic. 176, no. June, 113710, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C. H.; Ma, H. W. Improving the integrated hybrid LCA in the upstream scope 3 emissions inventory analysis. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2013, 18, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories. 2019. Available online: www.ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp/public/2019rf/ index.html.

- Chan, S.; Brandi, C.; Bauer, S. Aligning transnational climate action with international climate governance: the road from Paris. Rev. Eur. Comp. Int. Environ. Law 2016, 25, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acobta, A. N. bila; Ayompe, L. M.; Wandum, L. M.; Tambasi, E. E.; Muyuka, D. S.; Egoh, B. N. Greenhouse gas emissions along the value chain in palm oil producing systems: A case study of Cameroon. Clean. Circ. Bioeconomy 2023, 6, no. February, 100057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusuf, A. M.; Abubakar, A. B.; Mamman, S. O. Relationship between greenhouse gas emission, energy consumption, and economic growth: evidence from some selected oil-producing African countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 15815–15823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boakye, B.; Ofori, C. G.; Yaotse, K. Examining Methane Management in the Climate Action Plans of Oil Producing African Nations; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC Climate Change 2021. The Physical Science Basis. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1.

- Defra, “UK Government GHG Conversion Factors for Company Reporting. Departme,” 2023. 2023.

- IEA. Energy Efficiency, International Energy Agency. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/energy-efficiency-2022.

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Energy Efficiency 2023. 2023. [Google Scholar]

- IEA. Cameroon: Energy Profile. International Energy Agency. Available online: https://www.iea.org/countries/cameroon.

- Sotos, M. GHG Protocol Scope 2 Guidance. World Resour. intstitute 2022, 120. [Google Scholar]

- I.R.E.N.A., renewable power generation costs in 2016,» international renewable energy agency’’. IRENA rapport.

- Protocol, G. Corporate Value Chain (Scope 3) Accounting and Reporting Standard. World Resources Institute and World Business Council for Sustainable Development. 2011. Available online: https://ghgprotocol.org/standards/scope-3-standard.

- International Energy Agency. Africa Energy Outlook 2022. 2022. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/africa-energy-outlook-2022.

- Amponsah, N. Y.; Troldborg, M.; Kington, B.; Aalders, I.; Hough, R. L. Greenhouse gas emissions from renewable energy sources: A review of lifecycle considerations. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 39, 461–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Kuppusamy, M. Magazine, U. R.-E. J. of Operational, and undefined 2017, “Electric vehicle adoption decisions in a fleet environment,”. Elsevier. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0377221717302436 (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Matthews, H. S.; Hendrickson, C. T.; Weber, C. L. The importance of carbon footprint estimation boundaries. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 5839–5842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- P. Ghisellini, C. Cialani, S. U.-J. of C. production, and undefined 2016, “A review on circular economy: the expected transition to a balanced interplay of environmental and economic systems,” ElsevierP Ghisellini, C Cialani, S UlgiatiJournal Clean. Prod. 2016•Elsevier. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0959652615012287 (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- D. Wilson, L. Rodic, … A. S.-P. W. 2010, and undefined 2010, “Comparative analysis of solid waste management in cities around the world,” core.ac.ukDC Wilson, L Rodic, A Scheinberg, G AlabasterProceedings Waste 2010 Waste Resour. Manag. Strateg. into, 2010•core.ac.uk, pp. 28–29, 2010. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/29239126.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), “Waste,” 2022.

- IEA. Africa Energy Outlook 2019 – Analysis - IEA. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/africa-energy-outlook-2019 (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- Government, S. A. Carbon tax Act. South African Gov. 2019, 647, 1–65. Available online: https://www.gov.za/documents/carbon-tax-act-15-2019-english-afrikaans-23-may-2019-0000.

- Union, U. africaine, and U. africano, “Agenda2063 report of the commission on the African Union Agenda 2063 The Africa we want in 2063,” 2015. Available online: https://archives.au.int/handle/123456789/4631 (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- MINEPDED, “Plan National d’Adaptation aux Changements Climatique du Cameroun,” Cameroon-MINEPNDD, pp. 1–154, 2015, [Online]. Available: www4.unfccc.int/.../PNACC_Cameroun_VF_Validée_24062015 - FINAL.pdf.

- African Development Bank Group. Green Investment Program for Africa |. Available online: https://www.afdb.org/en/topics-and-sectors/initiatives-and-partnerships/green-investment-program-africa (accessed on 3 July 2025).

- UNFCCC. Private Sector Engagement in Climate Finance. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Available online: https://unfccc.int/ (accessed on 3 July 2025).

| Emissions categories | Emissions activities |

|---|---|

|

Direct GHG emissions |

Laboratory chemical processes (lubricant production) |

| Stationary combustion (use of diesel as a generator for the generator set) | |

| Compression unloading process (extraction of gas from tankers to the company's tanks) | |

| manufacturing process for gas storage cylinders | |

| Vehicle operating inside the company | |

| Indirect emissions associated with energy | Electrical Heat-generating machines |

| Electronic devices, air conditioning air-conditioning, filtering process | |

|

Other indirect emissions |

Moving employees |

| Purchases and upstream transport of goods | |

| Waste generated | |

| Use and Leakage of refrigerants | |

| Use of purchased materials (butane, gas cylinders, granules, seals, etc.) | |

| End of life of purchased materials | |

| Company / Study | Scope 1 (%) | Scope 2 (%) | Scope 3 (%) | Region |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BOCOM Petroleum (This study) | 29% | 33% | 38% | Cameroon |

| Industry Average [48] | 25% | 30% | 45% | Global |

| IEA Regional Average [49] | 28% | 30% | 42% | Sub-Saharan Africa |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).