Submitted:

16 January 2026

Posted:

20 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Cell Culture and Adipogenic Differentiation

Transfection and Stable Clone Selection

Real-Time RT-qPCR

Western Blot

Calcium Retention Capacity (CRC) Assay

Seahorse Assay

Metabolomics

Mouse Strains

Isolation and Culture of Mouse Primary BMSCs

Ectopic Bone Formation Assay

Micro-Computed Tomography (μCT) Analysis

Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry (DEXA)

Osmium Tetroxide Staining

Histology

Immunofluorescence (IF) Staining

Statistics

Results

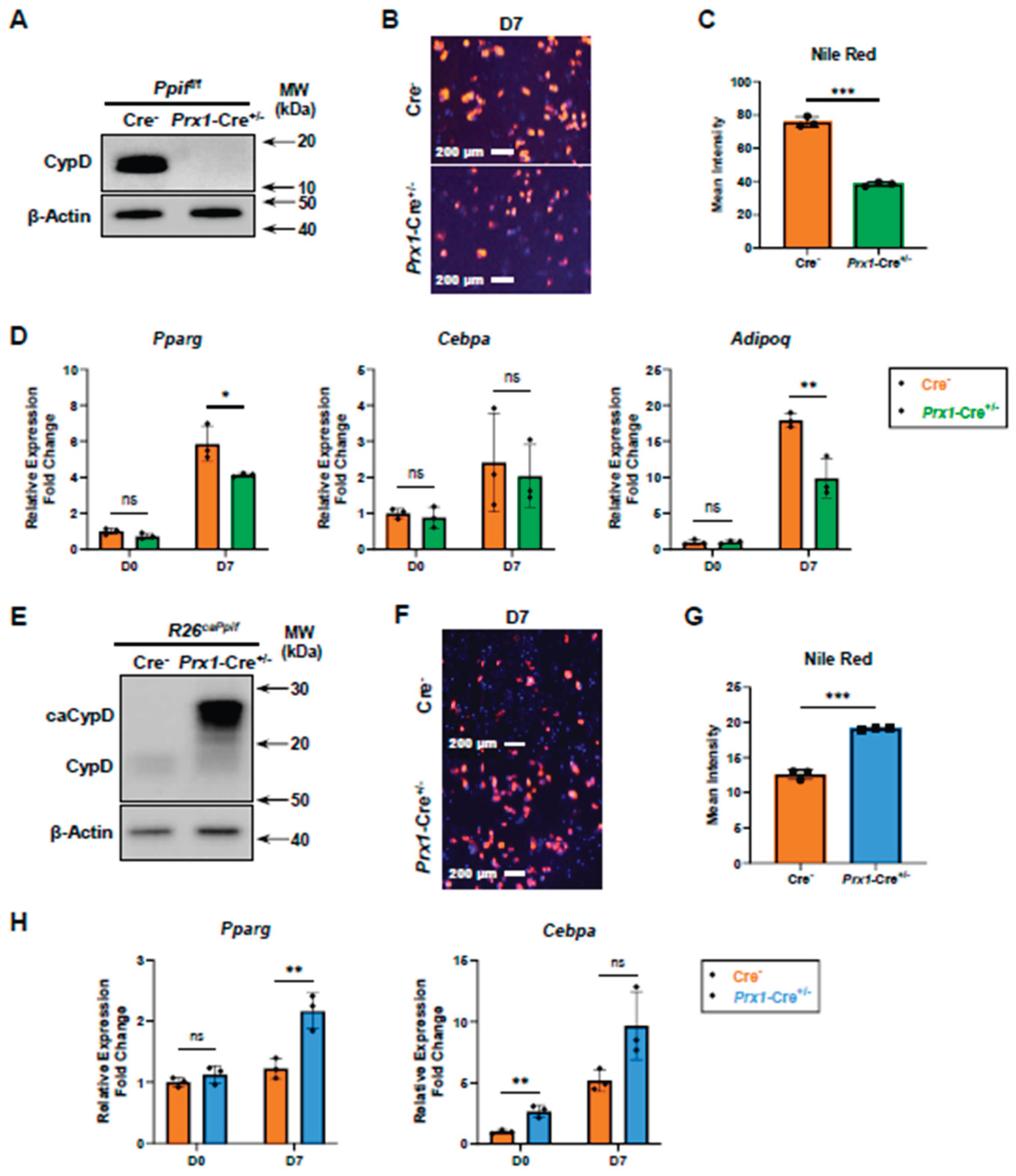

CypD Knockdown Decreases MPTP Activity and Impairs Adipogenesis, Whereas caCypD Expression Increases MPTP Activity and Enhances Adipogenesis

CypD Knockdown Improves Mitochondrial Function, Whereas caCypD Expression Impairs Mitochondrial Function and Activates Glycolysis

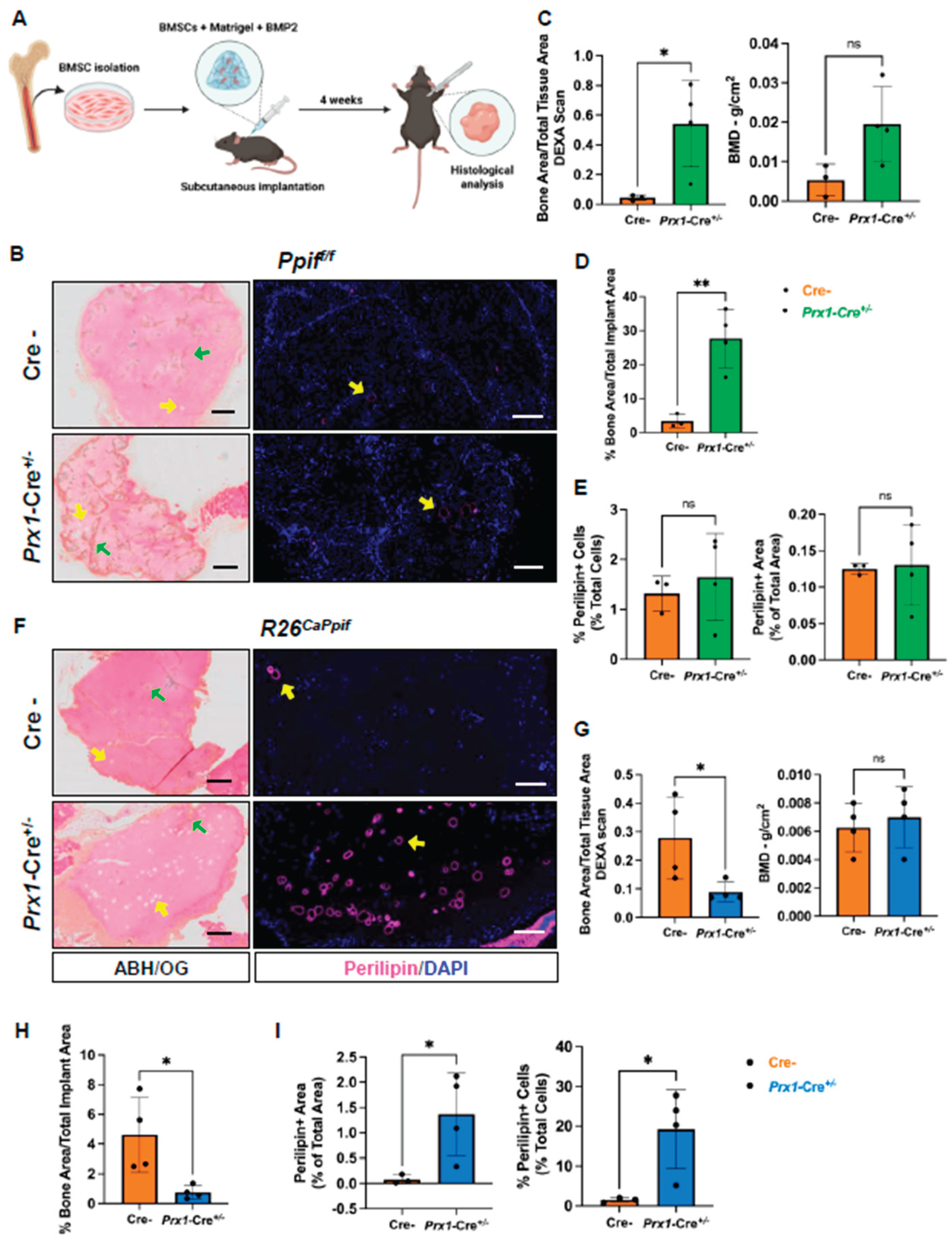

BMSC-Specific CypD Knockout Decreases Whereas caCypD Expression Increases Fat Accumulation During Ectopic Bone Formation in Mice

Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding and additional information

Abbreviations

| BMSCs | bone marrow stromal cells |

| HSCs | hematopoietic stem cells |

| BMAs | bone marrow adipocytes |

| OBs | osteoblasts |

| BM | bone marrow |

| BMAT | bone marrow adipose tissue |

| WAT | white adipose tissue |

| BAT | brown adipose tissue |

| OXPHOS | oxidative phosphorylation |

| MPTP | mitochondrial permeability transition pore |

| CypD | Cyclophilin D |

| caCypD | K166Q constitutively active CypD |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| PTMs | post-translational modifications |

| LOF | loss of function |

| GOF | gain of function |

| OCR | oxygen consumption rate |

| ECAR | extracellular acidification rate |

| LC-MS | liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry |

| BMD | bone mineral density |

| BMC | bone mineral content |

| ABH/OG | alcian blue hematoxylin/orange G |

| CRC | calcium retention capacity |

| DHAP | dihydroxyacetone phosphate |

| GSH | glutathione |

| GSSG | glutathione disulfide |

| PPP | pentose phosphate pathway |

| 2-HG | 2-hydroxyglutarate |

References

- Boskey, A.L.; Coleman, R. Aging and bone. J Dent Res 2010, 89(12), 1333–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kfoury, Y.; Scadden, D.T. Mesenchymal cell contributions to the stem cell niche. Cell Stem Cell 2015, 16(3), 239–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; et al. Paracrine and endocrine actions of bone-the functions of secretory proteins from osteoblasts, osteocytes, and osteoclasts. Bone Res 2018, 6, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsenty, G. Update on the Biology of Osteocalcin. Endocr Pract 2017, 23(10), 1270–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, E.; Koo, J.S. The Role of Adipokines and Bone Marrow Adipocytes in Breast Cancer Bone Metastasis. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21(14). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suchacki, K.J.; et al. Bone marrow adipose tissue is a unique adipose subtype with distinct roles in glucose homeostasis. Nat Commun 2020, 11(1), 3097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamrick, M.W.; McGee-Lawrence, M.E.; Frechette, D.M. Fatty Infiltration of Skeletal Muscle: Mechanisms and Comparisons with Bone Marrow Adiposity. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2016, 7, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nehlin, J.O.; et al. Aging and lineage allocation changes of bone marrow skeletal (stromal) stem cells. Bone 2019, 123, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafalski, V.A.; Mancini, E.; Brunet, A. Energy metabolism and energy-sensing pathways in mammalian embryonic and adult stem cell fate. J Cell Sci 2012, 125 Pt 23, 5597–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.T.; et al. Coordinated changes of mitochondrial biogenesis and antioxidant enzymes during osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells 2008, 26(4), 960–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forni, M.F.; et al. Murine Mesenchymal Stem Cell Commitment to Differentiation Is Regulated by Mitochondrial Dynamics. Stem Cells 2016, 34(3), 743–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shares, B.H.; et al. Active mitochondria support osteogenic differentiation by stimulating β-catenin acetylation. J Biol Chem 2018, 293(41), 16019–16027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shum, L.C.; et al. Energy Metabolism in Mesenchymal Stem Cells During Osteogenic Differentiation. Stem Cells Dev 2016, 25(2), 114–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, C.O.; Eliseev, R.A. Energy Metabolism During Osteogenic Differentiation: The Role of Akt. Stem Cells Dev 2021, 30(3), 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; et al. Glutamine Metabolism Regulates Proliferation and Lineage Allocation in Skeletal Stem Cells. Cell Metab 2019, 29(4), 966–978.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kinnally, K.W.; Campo, M.L.; Tedeschi, H. Mitochondrial channel activity studied by patch-clamping mitoplasts. J Bioenerg Biomembr 1989, 21(4), 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petronilli, V.; Szabò, I.; Zoratti, M. The inner mitochondrial membrane contains ion-conducting channels similar to those found in bacteria. FEBS Lett 1989, 259(1), 137–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, P.; et al. Identity, structure, and function of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore: controversies, consensus, recent advances, and future directions. Cell Death Differ 2023, 30(8), 1869–1885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, P.; von Stockum, S. The permeability transition pore as a Ca(2+) release channel: new answers to an old question. Cell Calcium 2012, 52(1), 22–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ichas, F.; Jouaville, L.S.; Mazat, J.P. Mitochondria are excitable organelles capable of generating and conveying electrical and calcium signals. Cell 1997, 89(7), 1145–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; et al. Superoxide flashes in single mitochondria. Cell 2008, 134(2), 279–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zorov, D.B.; et al. Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced ROS release: a new phenomenon accompanying induction of the mitochondrial permeability transition in cardiac myocytes. J Exp Med 2000, 192(7), 1001–14. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, Y.; et al. Mitoflash altered by metabolic stress in insulin-resistant skeletal muscle. J Mol Med (Berl) 2015, 93(10), 1119–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folmes, C.D.; et al. Mitochondria in control of cell fate. Circ Res 2012, 110(4), 526–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, M.B.; et al. C6 ceramide dramatically increases vincristine sensitivity both in vivo and in vitro, involving AMP-activated protein kinase-p53 signaling. Carcinogenesis 2015, 36(9), 1061–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, S.; et al. p53's mitochondrial translocation and MOMP action is independent of Puma and Bax and severely disrupts mitochondrial membrane integrity. Cell Res 2008, 18(7), 733–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliseev, R.A.; et al. Cyclophilin D interacts with Bcl2 and exerts an anti-apoptotic effect. J Biol Chem 2009, 284(15), 9692–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hafner, A.V.; et al. Regulation of the mPTP by SIRT3-mediated deacetylation of CypD at lysine 166 suppresses age-related cardiac hypertrophy. Aging (Albany NY) 2010, 2(12), 914–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, G.A., Jr.; Beutner, G. Cyclophilin D, Somehow a Master Regulator of Mitochondrial Function. Biomolecules 2018, 8(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sautchuk, R.; et al. Transcriptional regulation of cyclophilin D by BMP/Smad signaling and its role in osteogenic differentiation. Elife 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shares, B.H.; et al. Inhibition of the mitochondrial permeability transition improves bone fracture repair. Bone 2020, 137, 115391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sautchuk, R., Jr.; et al. Role of the Mitochondrial Permeability Transition in Bone Metabolism and Aging. J Bone Miner Res 2023, 38(4), 522–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sautchuk, R., Jr.; et al. Cyclophilin D, regulator of the mitochondrial permeability transition, impacts bone development and fracture repair. Bone 2024, 189, 117258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; et al. Mitochondrial permeability transition regulator, cyclophilin D, is transcriptionally activated by C/EBP during adipogenesis. J Biol Chem 2023, 299(12), 105458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheller, E.L.; et al. Use of osmium tetroxide staining with microcomputerized tomography to visualize and quantify bone marrow adipose tissue in vivo. Methods Enzymol 2014, 537, 123–39. [Google Scholar]

- Shum, L.C.; et al. Cyclophilin D Knock-Out Mice Show Enhanced Resistance to Osteoporosis and to Metabolic Changes Observed in Aging Bone. PLoS One 2016, 11(5), e0155709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ambrosi, T.H.; et al. Aged skeletal stem cells generate an inflammatory degenerative niche. Nature 2021, 597(7875), 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wabitsch, M.; et al. The role of growth hormone/insulin-like growth factors in adipocyte differentiation. Metabolism 1995, 44((10) Suppl 4, 45–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooke, P.S.; Naaz, A. Role of estrogens in adipocyte development and function. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2004, 229(11), 1127–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Y.; et al. Down-regulation of type I Runx2 mediated by dexamethasone is required for 3T3-L1 adipogenesis. Mol Endocrinol 2012, 26(5), 798–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, M.A.; et al. The cycling of acetyl-coenzyme A through acetylcarnitine buffers cardiac substrate supply: a hyperpolarized 13C magnetic resonance study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2012, 5(2), 201–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukao, T.; et al. Ketone body metabolism and its defects. J Inherit Metab Dis 2014, 37(4), 541–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; et al. L-threonine promotes healthspan by expediting ferritin-dependent ferroptosis inhibition in C. elegans. Nat Commun 2022, 13(1), 6554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massieu, L.; et al. Acetoacetate protects hippocampal neurons against glutamate-mediated neuronal damage during glycolysis inhibition. Neuroscience 2003, 120(2), 365–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noh, H.S.; et al. Acetoacetate protects neuronal cells from oxidative glutamate toxicity. J Neurosci Res 2006, 83(4), 702–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haces, M.L.; et al. Antioxidant capacity contributes to protection of ketone bodies against oxidative damage induced during hypoglycemic conditions. Exp Neurol 2008, 211(1), 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Board, M.; et al. Acetoacetate is a more efficient energy-yielding substrate for human mesenchymal stem cells than glucose and generates fewer reactive oxygen species. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 2017, 88, 75–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.; et al. Quantifying reductive carboxylation flux of glutamine to lipid in a brown adipocyte cell line. J Biol Chem 2008, 283(30), 20621–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; et al. Reductive carboxylation is a major metabolic pathway in the retinal pigment epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113(51), 14710–14715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mullen, A.R.; et al. Reductive carboxylation supports growth in tumour cells with defective mitochondria. Nature 2011, 481(7381), 385–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devalaraja-Narashimha, K.; et al.; Diener, A.M.; et al.; Padanilam, B.J. Cyclophilin D deficiency prevents diet-induced obesity in mice. FEBS Lett 2011, 585(4), 677–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laker, R.C.; et al. The Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore Regulator Cyclophilin D Exhibits Tissue-Specific Control of Metabolic Homeostasis. PLoS One 2016, 11(12), e0167910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tavecchio, M.; et al. Deletion of Cyclophilin D Impairs beta-Oxidation and Promotes Glucose Metabolism. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 15981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; et al. Liver cyclophilin D deficiency inhibits the progression of early NASH by ameliorating steatosis and inflammation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2022, 594, 168–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, M.A.; et al. Brief review of models of ectopic bone formation. Stem Cells Dev 2012, 21(5), 655–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusuma, G.D.; et al. Ectopic Bone Formation by Mesenchymal Stem Cells Derived from Human Term Placenta and the Decidua. PLoS One 2015, 10(10), e0141246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hashimoto, K.; et al. In vivo dynamic analysis of BMP-2-induced ectopic bone formation. Sci Rep 2020, 10(1), 4751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).