1. Introduction

Early childhood (3–6 years) represents a critical period for motor, cognitive, and behavioral development, with significant implications for future health and lifestyle habits [

1,

2,

3]. During this phase, fundamental capacities such as basic motor skills (MS), self-regulation, and early cognitive processes develop rapidly, laying the foundation for school readiness and long-term physical health [

4]. The concept of Twenty-four-hour movement behaviors (MV) encompasses physical activity (PA), sedentary time, and sleep, which are considered interdependent and essential for optimal development [

5,

6,

7]. In preschool children, regular PA is associated with better MS and overall functional development, while excessive sedentary behavior (SB) is linked to increased risk of overweight and reduced motor performance [

8,

9,

10]. Sleep and nap practices also contribute to neurocognitive development and body weight regulation [

11,

12,

13]. Furthermore, the quality and timing of these behaviors, as well as their interactions, may play a crucial role in shaping neuro-motor outcomes [

14]. However, the relationships between 24-hour MV, MS, and early cognitive functions remain complex and may be influenced by multiple factors, including individual characteristics, environmental conditions, and cultural practices [

15,

16,

17].

BMI is a key indicator of weight status in children, defined according to World Health Organization (WHO) references [

13,

18,

19]. Deviations from normal BMI, such as underweight or overweight, significantly influence fundamental MS and participation in PA [

18,

20,

21]. Systematic reviews and recent studies have confirmed that weight status plays a determining role in the development of physical fitness and motor competence from preschool to middle childhood [

22,

23,

24]. For example, elevated BMI is frequently associated with lower motor proficiency and reduced PA levels [

17,

25]. Anthropometric characteristics may also create biomechanical and physiological constraints that make certain motor tasks more difficult, potentially affecting motor learning and movement confidence [

26]. The anthropometric influence on physical fitness and MS in preschool children has also been documented in international studies [

19,

27].

Beyond motor aspects, weight status appears to be linked to cognitive development, particularly executive function (EF) such as inhibition, working memory, and cognitive flexibility [

28,

29,

30]. Preschool children with excess weight often demonstrate lower executive function and motor performance compared to their normal-weight peers [

11,

21]. 24-hour MV, including sleep and naps, also influence the development of EF [

15,

22]. Furthermore, early environmental factors, such as stimulation at home and school, parental education, and socioeconomic status, can modulate the impact of weight status and daily behaviors on cognitive and motor outcomes [

31,

32]. Despite this evidence, few studies have simultaneously examined BMI, 24-hour MV, motor competence, and EF in a comprehensive analytical framework, particularly in low- or middle-income countries such as Tunisia [

31].

However, existing evidence remains inconsistent, with some studies reporting associations between excess weight and reduced motor or executive function, while others find no significant relationship [

33]. These inconsistencies highlight the importance of multidimensional research approaches that consider not only BMI but also daily movement patterns, motor competence, cognitive development, and environmental influences. Moreover, such data are particularly scarce in the Tunisian context, where children’s daily routines, cultural practices, and environmental conditions may differ from those in other populations.

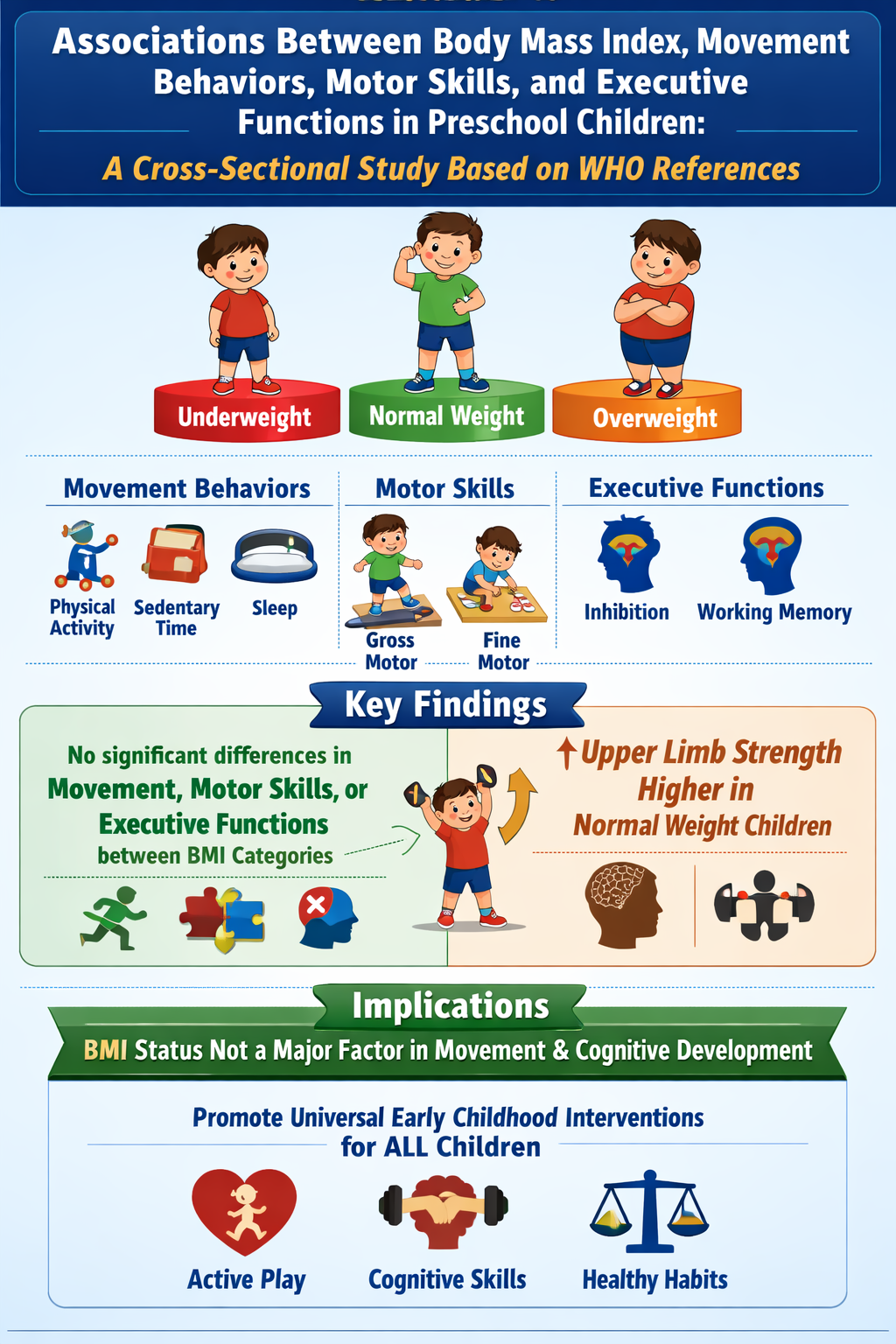

In this context, the present cross-sectional observational study seeks to investigate the associations of weight status, as determined by BMI according to WHO references, on 24-hour MV, motor competence, and EF in Tunisian children aged 4 to 5 years. To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has concurrently examined the impact of BMI on these three critical domains of neuro-motor development. By providing data from a middle-income country, this research contributes to the literature and advances our understanding of the early interactions between weight status, MV, and neuro-motor development in early childhood.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

This observational cross-sectional study included 112 preschool children (50 boys and 62 girls) aged 4 to 5 years (mean age: 4.10 ± 0.58 years; median: 4.13 years). Participants were recruited from five kindergartens located in urban and rural regions of Tunisia: El Manar and El Omrane (urban areas), and Cité Zahrouni and Séjoumi (rural areas).

The selected kindergartens included children aged between 4 and 5 years with parental or legal guardian consent. Children with medical conditions, physical disabilities, developmental disorders, or any other conditions that could influence movement, motor skills, or executive functions (MV, MS, or EF) were excluded from participation. The selection of kindergartens aimed to capture variability in environmental and sociodemographic contexts. Although differences between urban and rural areas are well documented, data from both settings were combined to increase statistical power and provide a sample broadly representative of preschool children across these regions, while minimizing the risk of confounding. The kindergartens were randomly selected from both urban and rural areas in Tunisia to ensure a diverse sample. While the sample is not fully nationally representative, it reflects the typical sociodemographic characteristics of preschool children in these regions.

2.2. Procedure

All measurements were performed within the kindergarten setting by a trained research teacher and two research assistants who followed standardized data collection protocols.

Anthropometric measurements, motor skill assessments, and executive function tasks were administered individually. Accelerometers were distributed to children and worn for five consecutive days during daily activities. Parent and center questionnaires were administered via face-to-face interviews at times convenient for families and kindergarten staff. All questionnaires and instructions were provided in Arabic to ensure clear understanding.

2.3. Ethical Approval Statement

All procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of Sousse (CEFMS 121/2022) and were conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians prior to participation. Children were informed of the study procedures in an age-appropriate manner.

2.4. Anthropometry and BMI Classification

2.4.1. Anthropometry

Body height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using customizable and repositionable adhesive measuring tapes, following standardized anthropometric procedures. Children stood barefoot in an upright position with the head aligned according to the Frankfurt plane. Each height measurement was performed twice, and when the difference between the two measurements exceeded 0.5 cm, a third measurement was taken, with the mean value retained for analysis.

Body mass was assessed to the nearest 0.1 kg using a calibrated SECA 750 Viva scale (SECA, Hamburg, Germany), with children wearing light clothing and no shoes. Two measurements were obtained, and if the difference exceeded 0.25 kg, a third measurement was conducted and the average value was used.

BMI was calculated as body weight (kg) divided by height squared (m²). Height-for-age (HAZ), weight-for-age (WAZ), and BMI-for-age (BAZ) z-scores were calculated using WHO growth reference standards [

19].

2.4.2. BMI Classification

According to WHO BMI-for-age z-score classifications [

19,

34], children were initially categorized as severely thin (< −3 SD), thin (−3 to < −2 SD), normal weight (−2 to +1 SD), at risk of overweight (> +1 to +2 SD), overweight (> +2 to +3 SD), or obese (> +3 SD).

For statistical analyses, categories were regrouped into three BMI groups:

a) BMI below normal (severe thinness and thinness)

b) BMI normal

c) BMI above normal (risk of overweight, overweight, and obesity).

This grouping is consistent with WHO standards for children aged 0–60 months (WHO Anthro) and 61 months to 19 years (WHO AnthroPlus) [

13,

34], ensuring standardized assessment of weight status adjusted for age and sex.

2.5. Physical Activity, Sedentary Behavior, and Sleep

PA, sedentary behavior (SB), and sleep were objectively measured using ActiGraph GT3X accelerometers (ActiGraph LLC, USA) attached to the right hip for five consecutive days.

Accelerometers were programmed at a sampling rate of 30 Hz and data were reintegrated into 15-second epochs using a low-frequency filter. ActiLife software (version 6.1.2.1) was used for data processing. A valid day required at least 24 hours of data, including a minimum of 6 hours of valid waking wear time.

Non-wear time was defined as 20 or more consecutive minutes of zero counts and excluded from analyses. Sleep periods were identified using accelerometer data and confirmed via parental reports and activity logs, and were excluded from PA and SB analyses.

Activity intensity thresholds were defined as follows: sedentary behavior (<800 counts·min⁻¹), light-intensity PA (800–1679 counts·min⁻¹), moderate-intensity PA (1680–3367 counts·min⁻¹), and vigorous-intensity PA (≥3368 counts·min⁻¹) [

35,

36].

2.6. Executive Function (EF)

The assessment of EF was conducted with the Early Years Toolbox. [

29], focusing on inhibition and visuospatial working memory. Each task lasted approximately 10 minutes and included a standardized practice phase at the beginning.

The original French versions of the games were translated verbatim into Arabic by a field worker, who was also a physical education teacher, using a forward translation method to ensure accurate adaptation of the content. This Arabic version is currently undergoing validation among Tunisian preschool children. It has been used in previous studies within the Tunisian context [

11], confirming its acceptability and comprehensibility for this population. All executive function assessments were administered individually in a quiet environment within the kindergartens by trained research assistants.

2.7. Gross and Fine Motor Skills

MS were assessed using selected tests from the NIH Toolbox [

37] and administered in a spacious classroom environment.

2.7.1. Gross Motor Skills

2.7.1.1. Functional Mobility (Mobility and Posture: Supine-Timed Up and Go)

Functional mobility was assessed using the supine Timed Up and Go test. Children started lying on their back behind a marked line, stood up as quickly as possible, ran to touch a target located 3 m away, and returned to the starting position. One practice trial and two test trials were performed.

2.7.1.2. Posture: One-Leg Standing Balance Test

Postural stability was assessed using the one-leg standing balance test. Children stood on one leg with their arms alongside the body while the opposite foot was lifted off the ground. The test ended if the child shifted the standing foot or wrapped the free leg around it. Each leg was tested for a maximum of 30 seconds, and the mean of both trials was calculated for analysis.

2.7.1.3. Upper Body Strength: Hand Grip Dynamometer

Upper body strength was assessed using a hand grip dynamometer (TKK 5825, Grip-A). Children were instructed to squeeze the device with maximum force for at least 3 seconds without touching their body. One practice trial and two recorded trials were performed for each hand [

38].

2.7.1.4. Lower Body Strength and Mobility

Lower limb strength and mobility were assessed via the standing long jump. Participants stood behind a marked line and jumped as far forward as possible using both feet. After a practice jump, two trials were recorded, and the mean distance was used for analysis.

2.7.2. Fine Motor Skills

2.7.2.1. Manipulation: 9-Hole Pegboard Test

Fine motor dexterity was evaluated using the 9-Hole Pegboard Test. Children were asked to place and remove nine pegs one by one as quickly as possible. Timing began when the first peg was touched and ended when the last peg was removed. The total completion time (seconds) was used for analysis. This test has demonstrated good reliability and validity for assessing fine MS in children [

39].

2.8. Questionnaires

2.8.1. Center Information Questionnaire

A Center Information Questionnaire was administered via interview to kindergarten directors. The questionnaire collected information on the total number of children enrolled, participation rates, daily nap schedules, meal provision, food policies, and nutrition practices within the center. In addition, the questionnaire included items adapted from the SUNRISE parent/guardian questionnaire to provide further context, such as children’s daily routines, sleep schedules, time spent in screen activities, time spent sitting or restrained, and eating behaviors, including dietary intake at home outside the kindergarten setting. The SUNRISE questionnaire was translated into the two most common local languages, Arabic and French, and caregivers could choose the language they were most comfortable with. Caregivers were also asked about their interactions with the child during meals, playtime, walks, travel, and bedtime routines. These data were used to provide descriptive contextual information about the kindergarten environment and were not included as covariates in the statistical analyses [

27].

2.9. Statistical analysis

No a priori sample size calculation was performed, as this study followed a pragmatic observational cross-sectional design within the SUNRISE framework. The sample size was determined by feasibility and participant availability during the data collection period. Data were analyzed using SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 26.0). Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and categorical variables as number (percentage).

Differences between the three BMI categories were examined using the Kruskal–Wallis test for continuous variables and Pearson’s chi-square tests for categorical variables. When a significant overall effect was observed for continuous variables, pairwise comparisons were conducted and the significance values adjusted using the Bonferroni correction for multiple tests were reported. Children were classified into three BMI groups (BMI below normal, BMI normal, and BMI above normal) according to WHO reference standards [

19].

Children were classified as meeting the PA guidelines if they accumulated an average of ≥ 180 min/day of total PA, including ≥ 60 min/day of moderate-to-vigorous PA, as measured by accelerometry. Accelerometer data were processed using ActiLife software (version 6.1.2.1), with non-wear time (≥ 20 consecutive minutes of zero counts) excluded and a valid day defined as at least 24 hours of data, including a minimum of 6 hours of valid waking wear time. Sleep periods were identified from accelerometer data and confirmed via parental reports and activity logs, and were excluded from PA and sedentary behavior analyses. Compliance with the sedentary screen time recommendation was defined as ≤ 60 min/day, and compliance with the sleep duration recommendation was defined as 10–13 h per 24-hour period, based on parent-reported data. These definitions are in accordance with the WHO Guidelines on PA, Sedentary Behavior and Sleep for Children under 5 Years [

34].The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

Table 1 presents the anthropometric characteristics and MV of preschool children according to BMI categories. Significant differences were observed between BMI groups for most anthropometric variables, including height-for-age (HAZ), weight-for-age (WAZ), and BMI-for-age z-scores (BAZ), indicating differences in overall growth. Height-for-age (HAZ) and weight-for-age (WAZ) z-scores were also higher in children with elevated BMI, indicating greater overall growth. No significant differences in age were found between groups, ensuring good comparability and ruling out age as a major confounding factor. No significant differences were observed between BMI groups for light, moderate, vigorous, moderate-to-vigorous (MVPA), or total PA, SB, screen time, or sleep duration (all p > 0.05). This suggests that at this age, BMI differences are mainly associated with anthropometric characteristics rather than daily MV.

Table 2 presents the number and proportion of preschool children meeting the 24-hour movement guidelines according to BMI categories. The majority of children (76.4%) met the guideline of ≥60 minutes/day of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA), with similar proportions across BMI groups (p = 0.586). Fewer children met the total physical activity (TPA) guideline of ≥80 minutes/day (40.5%), with no significant differences between BMI categories (p = 0.076). Likewise, the combined guideline of ≥60 minutes/day MVPA and ≥180 minutes/day TPA was met by 40.4% of children, with comparable rates across BMI groups. Over half of the children (52.7%) met the screen time guideline of ≤60 minutes/day, with no significant differences between groups (p = 0.886). Most children (81.3%) achieved the recommended sleep duration of 10–13 hours/day, again with no significant differences according to BMI (p = 0.640). Only 18% of children met all five 24-hour movement recommendations, with no significant differences across BMI categories (p = 0.428).

Table 3.

Executive function and gross and fine motor skill outcomes of preschool children according to body mass index (BMI) categories (Mean ± SD).

Table 3.

Executive function and gross and fine motor skill outcomes of preschool children according to body mass index (BMI) categories (Mean ± SD).

| Variables |

Total (N = 112) |

BMI < normal (n = 5) |

BMI = normal (n = 69) |

BMI > normal (n = 38) |

P value |

| Inhibition |

0.67 ± 0.24 |

0.57 ± 0.29 |

0.68 ± 0.24 |

0.65 ± 0.25 |

0.662 |

| Working memory |

1.89 ± 0.74 |

2.00 ± 1.22 |

1.85 ± 0.71 |

1.95 ± 0.72 |

0.686 |

| Functional mobility (s) |

5.30 ± 1.41 |

5.17 ± 1.53 |

4.84 ± 1.40 |

4.81 ± 1.43 |

0.836 |

| Postural steadiness (s) |

12.6 ± 7.1 |

13.3 ± 7.8 |

15.5 ± 9.2 |

15.0 ± 9.2 |

0.174 |

| Lower body strength (cm) |

56.1 ± 20.8 |

56.6 ± 22.4 |

57.9 ± 21.5 |

57.2 ± 21.7 |

0.231 |

| Upper body strength (kg) |

7.24 ± 2.52 |

7.56 ± 3.19 |

8.21 ± 2.84 |

8.13 ± 2.87 |

0.418 €

1.000π

0.035 β

|

| Dexterity (s) |

40.9 ± 9.8 |

39.4 ± 10.9 |

36.9 ± 9.9 |

37.4 ± 10.0 |

0.253 |

4. Discussion

The current cross-sectional observational study aimed to examine the influence of BMI, classified according to WHO references, on 24-hour MV, motor competence, and EF in Tunisian preschool children aged 4 to 5 years. To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the few studies to simultaneously analyze these three key domains of early neuro-motor development in a middle-income country context. The major finding of the current investigation is that BMI defined according to WHO references status was primarily associated with differences in physical growth, while showing no statistically detectable associations with 24-hour MV, EF, or most components of motor competence at the age of 4 to 5 years, with the exception of upper limb strength, which was slightly higher in children with normal BMI compared with those with above-normal BMI. These non-significant findings should be interpreted with caution, as they may reflect either a true absence of relationship or be partly explained by the limited sample size, reduced statistical power, or the sensitivity of the measurement tools used in this age group. Therefore, the possibility of a Type II error cannot be excluded.

4.1. Anthropometric Differences According to BMI Categories

Significant differences were observed between BMI categories for the majority of anthropometric variables. Children with above-normal BMI had higher body weight, height, BMI, and BMI-for-age z-scores (BAZ) compared to their normal-weight or underweight peers. Height-for-age (HAZ) and weight-for-age (WAZ) z-scores were also higher in children with elevated BMI, reflecting greater overall somatic growth. These anthropometric differences are partly expected due to BMI-based classification and should therefore be interpreted with caution, particularly given the well-recognized limitations of BMI in early childhood, including its inability to distinguish between fat mass and lean mass. These findings may reflect a pattern of accelerated global growth, which could be related to mechanisms such as early adiposity rebound and individual growth variability; however, such interpretations remain speculative [

11,

13,

17].

These results are consistent with previous studies reporting clear anthropometric distinctions between BMI categories during early childhood [

9,

10,

25]. For instance, research has shown that children with elevated BMI not only exhibit higher body weight but also greater linear growth indicators, suggesting that BMI captures overall somatic development rather than exclusively excess adiposity, which may help explain the limited or non-statistically detectable associations observed with motor competence and EF [

9,

13].

No age differences were observed between BMI groups, indicating that the observed anthropometric variations are not influenced by age-related developmental differences. This observation supports the notion that differences in height and weight are primarily related to weight status rather than maturation and allows controlling for the effect of age when analyzing associations between BMI, motor competence, and EF [

11,

17].

4.2. BMI and 24-Hour Movement Behaviors

In the present study, no significant differences were observed between BMI categories regarding objectively measured PA (light, moderate, vigorous, MVPA, or total physical activity), SB, screen time, or sleep duration. These findings suggest that, in preschool children, BMI-related differences do not yet translate into observable disparities in daily MV.

This observation aligns with previous research indicating that associations between BMI and PA tend to strengthen with age, particularly during primary school and adolescence, when children gain more autonomy in choosing their physical activities [

5,

6,

10,

36]. During early childhood, environmental constraints, such as structured kindergarten schedules, guided play, and limited screen exposure, may contribute to a relative homogeneity of MV across BMI groups, independent of weight status [

1,

4,

7].

Moreover, the low proportion of children (~18%) meeting MVPA and sleep recommendations, regardless of BMI category, supports the notion that MV at this age are more strongly influenced by the educational environment, parental practices, and daily routines than by individual body composition [

5,

10,

11,

14,

31].

These results also underscore the need to account for environmental and contextual factors when assessing the relationship between weight status and PA in early childhood. Interventions aimed at improving MV at this age may need to focus more on increasing structured opportunities for active play and promoting regular sleep routines, rather than relying solely on BMI stratification [

5,

32].

4.3. Adherence to the 24-Hour Movement Guidelines

Although a relatively large proportion of children met the individual recommendations for moderate-to-vigorous PA (MVPA) and sleep, less than one-fifth of participants met all five components of the 24-hour movement guidelines. This finding is consistent with previous SUNRISE study data from low- and middle-income countries, which consistently report low adherence to combined guidelines, even when individual behaviors are relatively well met [

40,

41,

42]. These patterns may reflect the structure of preschool environments, parental practices, and cultural norms that promote certain behaviors (e.g., adequate sleep or MVPA) but do not necessarily support a fully integrated daily movement balance.

Notably, adherence rates did not differ significantly across BMI categories, suggesting that, in preschool-aged children, weight status is not strongly associated with daily MV. Given the cross-sectional design and unadjusted analyses, causal inferences cannot be made. Important covariates, such as accelerometer wear time and potential center-level effects, were not controlled and may have influenced these results. It should also be noted that the use of a binary outcome (compliance vs non-compliance) may reduce sensitivity to detect differences between groups, and that the study may not have had sufficient statistical power to identify potential group differences. Therefore, the absence of statistically significant differences should not be interpreted as evidence of no effect of BMI on daily MV. This observation supports the idea that early childhood represents a key window of opportunity for universal interventions promoting healthy MV, rather than focusing solely on children with excess weight [

10,

42,

43,

44]. Furthermore, the overall low adherence highlights the need for comprehensive strategies that address all aspects of 24-hour movement, including light PA, SB, and sleep, to optimize motor and cognitive development from an early age [

6,

7,

40,

43].

4.4. BMI, Executive Functions, and Motor Skills

No significant differences were observed between BMI groups for EF (inhibition and working memory) or for most measures of gross and fine MS. This finding contrasts with some studies reporting poorer motor and cognitive performance among children with overweight or obesity [

4,

21], where excess adiposity has been linked to lower motor coordination and reduced neuromuscular performance in pediatric samples [

18,

45]. However, such associations are not always consistent, especially in early childhood [

21,

28], and may only emerge more clearly as children grow older and behavioral and physiological differences accumulate [

18,

45]. It should also be noted that assessing EF in preschool-aged children has inherent developmental limitations, including possible ceiling or floor effects, variability in children’s understanding of task instructions, and fluctuations in behavior during testing. The EF assessment tools used in the present study may have had limited sensitivity to detect subtle differences between BMI groups, which should be considered when interpreting these non-significant findings.

Interestingly, only upper limb strength differed significantly between BMI groups, with children of normal BMI showing slightly higher grip strength compared to those with above normal BMI. This isolated difference may reflect muscle development and habitual activity patterns rather than overall motor competence or neuromuscular fitness, and can be influenced by hand size, body weight, or children’s motivation during testing [

20,

21,

45]. Indeed, the relationship between body composition and motor performance in preschoolers is complex and multifactorial, with some studies finding no significant BMI related deficits in motor or cognitive measures at very young ages [

18,

46]. Therefore, these results should be interpreted with caution and do not imply causal effects of BMI on MV, MS, or EF at this age [

10,

18,

26].

4.5. Implications for Child Development and Public Health

The lack of strong associations between BMI, MV, EF, and MS at this age suggests that the preschool period represents a critical window for universal preventive actions. Interventions aimed at promoting balanced MV, motor skill development, and healthy growth should target all children, regardless of their weight status [

47,

48].

These findings emphasize the importance of implementing early educational and environmental strategies in early childhood settings, particularly in middle-income countries such as Tunisia [

31], where lifestyle transitions can quickly influence childhood obesity trajectories [

49]. Integrating programs that encourage PA, reduce sedentary time, and foster motor skill development from early childhood may have lasting effects on children’s health and cognitive development [

40,

43].

4.6. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

This study’s main strengths lie in the objective assessment of 24-hour MV via accelerometry, the use of WHO-standardized BMI classifications, and the thorough evaluation of MS and EF. The inclusion of children from both urban and rural settings further enhances the ecological validity of the findings and better reflects the diversity of living contexts in Tunisia.

However, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, it is important to note that this is an observational study, with a convenience sample and no a priori sample size or statistical power calculation, which may limit the generalizability of the results and increase the risk of Type II error. All statistical analyses were based on unadjusted comparisons, and important covariates, such as accelerometer wear time, were not controlled, which may have influenced the results. In addition, the very small number of children in the underweight BMI category (n = 5) may have limited the robustness and generalizability of the statistical comparisons. Moreover, no a priori sample size or statistical power calculation was conducted, which may increase the risk of Type II error. Therefore, the absence of statistically significant differences between BMI categories should be interpreted with caution and does not necessarily indicate the absence of meaningful associations. Furthermore, the limitations related to the assessment of EF and MS should be emphasized. Executive function assessment in preschool children has inherent developmental limitations, such as possible ceiling or floor effects, and the fact that only two EF domains were assessed may limit the ability to detect differences between BMI groups. Additionally, the sensitivity of the instruments and the psychometric properties of the tools, particularly the Arabic versions, should be considered when interpreting these results. Finally, dietary intake was not directly assessed, which could partially explain BMI variability independent of MV. Other unmeasured factors, such as genetics, family habits, and socioeconomic environment, may also have influenced the observed results.

5. Conclusions

This cross-sectional study indicates that in Tunisian preschool children aged 4 to 5 years, BMI according to WHO references is associated with anthropometric differences but shows no statistically detectable associations with 24-hour MV, EF, or most MS. Only upper limb strength showed a slight difference between BMI groups. These findings highlight the importance of universal early childhood interventions to promote balanced motor and cognitive development. Future research should use longitudinal designs to better understand the interactions between BMI, MV, and neuro-motor development over time, considering dietary, socio-economic, and environmental factors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.L.; F.H., D.I.A. and M.S.C.; methodology, M.A.L., A.Z., M.D.B., M.W. and K.N.; software, K.N., F.H. and A.Z.; validation, M.A.L., K.N., M.D.B., F.H. and D.I.A.; formal analysis, M.A.L., A.Z. and M.W.; investigation, M.A.L. and K.N.; resources, K.N., M.D.B., M.W. and D.I.A.; data curation, M.A.L., M.W. and F.H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.L.; writing—review and editing, K.N., D.I.A., M.D.B., A.Z., M.W., M.A.L, F.H. and M.S.C.; visualization, F.H., M.D.B., A.Z., M.W. and M.S.C.; supervision, M.S.C. and D.I.A.; project administration, M.A.L. and D.I.A.; funding acquisition, M.D.B. and D.I.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine of Sousse (CEFMS 121/2022) and were conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from parents or legal guardians prior to participation. Children were informed of the study procedures in an age-appropriate manner.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all parental or legal guardian consent for the subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from them to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

A special thank you to Ghaith Ben-Bouzaiene for their invaluable assistance throughout the implementation of the study in the kindergarten. Dan Iulian Alexe thanks to ”Vasile Alecsandri” University of Bacău, Romania for the support it has provided.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

|

Abbreviation

|

Definition

|

| BMI |

Body Mass Index |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

| PA |

Physical Activity |

| EF |

Executive Functions |

| MS |

Motor Skills |

| LPA |

Light-intensity Physical Activity |

| MPA |

Moderate-intensity Physical Activity |

| VPA |

Vigorous-intensity Physical Activity |

| MB |

Movement Behaviors |

| MVPA |

Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity |

| TPA |

Total Physical Activity |

| SB |

Sedentary Behavior |

| SST |

Sedentary Screen Time |

| HAZ |

Height-for-age z-score |

| WAZ |

Weight-for-age z-score |

| BAZ |

BMI-for-age z-score |

References

- National Research, C.; Institute of Medicine Committee on Integrating the Science of Early Childhood, D. In From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development, Shonkoff, J.P., Phillips, D.A., Eds.; National Academies Press (US) Copyright 2000 by the National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved.: Washington (DC), 2000.

- Brown, T.T.; Jernigan, T.L. Brain development during the preschool years. Neuropsychology review 2012, 22, 313-333. [CrossRef]

- Bornstein, M.H.; Britto, P.R.; Nonoyama-Tarumi, Y.; Ota, Y.; Petrovic, O.; Putnick, D.L. Child development in developing countries: introduction and methods. Child development 2012, 83, 16-31. [CrossRef]

- Bai, P.; Johnson, S.; Trost, S.G.; Lester, L.; Nathan, A.; Christian, H. The Relationship between Physical Activity, Self-Regulation and Cognitive School Readiness in Preschool Children. International journal of environmental research and public health 2021, 18. [CrossRef]

- Chaput, J.P.; Carson, V.; Gray, C.E.; Tremblay, M.S. Importance of all movement behaviors in a 24 hour period for overall health. International journal of environmental research and public health 2014, 11, 12575-12581. [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, M.S.; LeBlanc, A.G.; Kho, M.E.; Saunders, T.J.; Larouche, R.; Colley, R.C.; Goldfield, G.; Connor Gorber, S. Systematic review of sedentary behaviour and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. The international journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity 2011, 8, 98. [CrossRef]

- Timmons, B.W.; Naylor, P.J.; Pfeiffer, K.A. Physical activity for preschool children--how much and how? Canadian journal of public health = Revue canadienne de sante publique 2007, 98 Suppl 2, S122-134.

- Duch, H.; Fisher, E.M.; Ensari, I.; Harrington, A. Screen time use in children under 3 years old: a systematic review of correlates. The international journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity 2013, 10, 102. [CrossRef]

- Carter, P.J.; Taylor, B.J.; Williams, S.M.; Taylor, R.W. Longitudinal analysis of sleep in relation to BMI and body fat in children: the FLAME study. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 2011, 342, d2712. [CrossRef]

- Kuzik, N.; Carson, V. The association between physical activity, sedentary behavior, sleep, and body mass index z-scores in different settings among toddlers and preschoolers. BMC pediatrics 2016, 16, 100. [CrossRef]

- Ltifi, M.A.; Turki, O.; Ben-Bouzaiene, G.; Pagaduan, J.C.; Okely, A.; Chelly, M.S. Exploring 24-Hour Movement Behaviors in Early Years: Findings From the SUNRISE Pilot Study in Tunisia. Pediatric exercise science 2025, 37, 94-101. [CrossRef]

- Breastfeeding in the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study. Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992). Supplement 2006, 450, 16-26. [CrossRef]

- de Onis, M.; Garza, C.; Onyango, A.W.; Rolland-Cachera, M.F. [WHO growth standards for infants and young children]. Archives de pediatrie : organe officiel de la Societe francaise de pediatrie 2009, 16, 47-53. [CrossRef]

- Lau, P.W.C.; Song, H.; Song, D.; Wang, J.J.; Zhen, S.; Shi, L.; Yu, R. 24-Hour movement behaviors and executive functions in preschoolers: A compositional and isotemporal reallocation analysis. Child development 2024, 95, e110-e121. [CrossRef]

- Ltifi, M.A.; Chong, K.H.; Ben-Bouzaiene, G.; Okely, A.D.; Chelly, M.S. Observed relationships between nap practices, executive function, and developmental outcomes in Tunisian childcare centers. Sports medicine and health science 2025, 7, 272-279. [CrossRef]

- Greier, K.; Drenowatz, C. Bidirectional association between weight status and motor skills in adolescents : A 4-year longitudinal study. Wiener klinische Wochenschrift 2018, 130, 314-320. [CrossRef]

- Lima, R.A.; Soares, F.C.; Queiroz, D.R.; Aguilar, J.A.; Bezerra, J.; Barros, M.V.G. The importance of body weight status on motor competence development: From preschool to middle childhood. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports 2021, 31 Suppl 1, 15-22. [CrossRef]

- Rico-González, M.; Ardigò, L.P.; Ramírez-Arroyo, A.P.; Gómez-Carmona, C.D. Anthropometric Influence on Preschool Children's Physical Fitness and Motor Skills: A Systematic Review. Journal of functional morphology and kinesiology 2024, 9. [CrossRef]

- WHO Child Growth Standards based on length/height, weight and age. Acta paediatrica (Oslo, Norway : 1992). Supplement 2006, 450, 76-85. [CrossRef]

- Barnett, L.M.; Lai, S.K.; Veldman, S.L.C.; Hardy, L.L.; Cliff, D.P.; Morgan, P.J.; Zask, A.; Lubans, D.R.; Shultz, S.P.; Ridgers, N.D.; et al. Correlates of Gross Motor Competence in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports medicine (Auckland, N.Z.) 2016, 46, 1663-1688. [CrossRef]

- Fernandes, A.C.; Viegas Â, A.; Lacerda, A.C.R.; Nobre, J.N.P.; Morais, R.L.S.; Figueiredo, P.H.S.; Costa, H.S.; Camargos, A.C.R.; Ferreira, F.O.; de Freitas, P.M.; et al. Association between executive functions and gross motor skills in overweight/obese and eutrophic preschoolers: cross-sectional study. BMC pediatrics 2022, 22, 498. [CrossRef]

- Ltifi, M.A.; Cherni, Y.; Panaet, E.A.; Alexe, C.I.; Ben Saad, H.; Vulpe, A.M.; Alexe, D.I.; Chelly, M.S. Mini-Trampoline Training Enhances Executive Functions and Motor Skills in Preschoolers. Children (Basel, Switzerland) 2025, 12. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Dai, Q.; Jackson, J.C.; Zhang, J. Overweight is associated with decreased cognitive functioning among school-age children and adolescents. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.) 2008, 16, 1809-1815. [CrossRef]

- Tandon, P.S.; Sasser, T.; Gonzalez, E.S.; Whitlock, K.B.; Christakis, D.A.; Stein, M.A. Physical Activity, Screen Time, and Sleep in Children With ADHD. Journal of physical activity & health 2019, 16, 416-422. [CrossRef]

- Nervik, D.; Martin, K.; Rundquist, P.; Cleland, J. The relationship between body mass index and gross motor development in children aged 3 to 5 years. Pediatric physical therapy : the official publication of the Section on Pediatrics of the American Physical Therapy Association 2011, 23, 144-148. [CrossRef]

- Kakebeeke, T.H.; Lanzi, S.; Zysset, A.E.; Arhab, A.; Messerli-Bürgy, N.; Stuelb, K.; Leeger-Aschmann, C.S.; Schmutz, E.A.; Meyer, A.H.; Kriemler, S.; et al. Association between Body Composition and Motor Performance in Preschool Children. Obesity facts 2017, 10, 420-431. [CrossRef]

- Okely, T.; Reilly, J.J.; Tremblay, M.S.; Kariippanon, K.E.; Draper, C.E.; El Hamdouchi, A.; Florindo, A.A.; Green, J.P.; Guan, H.; Katzmarzyk, P.T.; et al. Cross-sectional examination of 24-hour movement behaviours among 3- and 4-year-old children in urban and rural settings in low-income, middle-income and high-income countries: the SUNRISE study protocol. BMJ open 2021, 11, e049267. [CrossRef]

- Best, J.R.; Miller, P.H. A developmental perspective on executive function. Child development 2010, 81, 1641-1660. [CrossRef]

- Blair, C.; Raver, C.C. School readiness and self-regulation: a developmental psychobiological approach. Annual review of psychology 2015, 66, 711-731. [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A. Executive functions. Annual review of psychology 2013, 64, 135-168. [CrossRef]

- Ltifi, M.A.; Turki, O.; Ben-Bouzaiene, G.; Chong, K.H.; Okely, A.D.; Chelly, M.S. Exploring urban-rural differences in 24-h movement behaviours among tunisian preschoolers: Insights from the SUNRISE study. Sports medicine and health science 2025, 7, 48-55. [CrossRef]

- de Souza Morais, R.L.; de Castro Magalhães, L.; Nobre, J.N.P.; Pinto, P.F.A.; da Rocha Neves, K.; Carvalho, A.M. Quality of the home, daycare and neighborhood environment and the cognitive development of economically disadvantaged children in early childhood: A mediation analysis. Infant behavior & development 2021, 64, 101619. [CrossRef]

- Mamrot, P.; Hanć, T. The association of the executive functions with overweight and obesity indicators in children and adolescents: A literature review. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews 2019, 107, 59-68. [CrossRef]

- Okely, A.D.; Kontsevaya, A.; Ng, J.; Abdeta, C. 2020 WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behavior. Sports medicine and health science 2021, 3, 115-118. [CrossRef]

- Pate, R.R.; Almeida, M.J.; McIver, K.L.; Pfeiffer, K.A.; Dowda, M. Validation and calibration of an accelerometer in preschool children. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md.) 2006, 14, 2000-2006. [CrossRef]

- Pate, R.R.; O'Neill, J.R.; Brown, W.H.; Pfeiffer, K.A.; Dowda, M.; Addy, C.L. Prevalence of Compliance with a New Physical Activity Guideline for Preschool-Age Children. Childhood obesity (Print) 2015, 11, 415-420. [CrossRef]

- Gershon, R.C.; Wagster, M.V.; Hendrie, H.C.; Fox, N.A.; Cook, K.F.; Nowinski, C.J. NIH toolbox for assessment of neurological and behavioral function. Neurology 2013, 80, S2-6. [CrossRef]

- Mathiowetz, V.; Wiemer, D.M.; Federman, S.M. Grip and pinch strength: norms for 6- to 19-year-olds. The American journal of occupational therapy : official publication of the American Occupational Therapy Association 1986, 40, 705-711. [CrossRef]

- Smith, Y.A.; Hong, E.; Presson, C. Normative and validation studies of the Nine-hole Peg Test with children. Perceptual and motor skills 2000, 90, 823-843. [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, M.S.; Carson, V.; Chaput, J.P.; Connor Gorber, S.; Dinh, T.; Duggan, M.; Faulkner, G.; Gray, C.E.; Gruber, R.; Janson, K.; et al. Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Children and Youth: An Integration of Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour, and Sleep. Applied physiology, nutrition, and metabolism = Physiologie appliquee, nutrition et metabolisme 2016, 41, S311-327. [CrossRef]

- Taylor, R.W.; Haszard, J.J.; Meredith-Jones, K.A.; Galland, B.C.; Heath, A.M.; Lawrence, J.; Gray, A.R.; Sayers, R.; Hanna, M.; Taylor, B.J. 24-h movement behaviors from infancy to preschool: cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships with body composition and bone health. The international journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity 2018, 15, 118. [CrossRef]

- Draper, C.E.; Tomaz, S.A.; Cook, C.J.; Jugdav, S.S.; Ramsammy, C.; Besharati, S.; van Heerden, A.; Vilakazi, K.; Cockcroft, K.; Howard, S.J.; et al. Understanding the influence of 24-hour movement behaviours on the health and development of preschool children from low-income South African settings: the SUNRISE pilot study. South African journal of sports medicine 2020, 32, v32i31a8415. [CrossRef]

- WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee. In Guidelines on Physical Activity, Sedentary Behaviour and Sleep for Children under 5 Years of Age; World Health Organization© World Health Organization 2019.: Geneva, 2019.

- Khan, A.; Ahmed, K.R.; Lee, E.Y. Adherence to 24-hour movement guidelines and their association with depressive symptoms in adolescents: Evidence from Bangladesh. Sports medicine and health science 2024, 6, 76-81. [CrossRef]

- Barros, W.M.A.; da Silva, K.G.; Silva, R.K.P.; Souza, A.; da Silva, A.B.J.; Silva, M.R.M.; Fernandes, M.S.S.; de Souza, S.L.; Souza, V.O.N. Effects of Overweight/Obesity on Motor Performance in Children: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in endocrinology 2021, 12, 759165. [CrossRef]

- Reisberg, K.; Riso, E.M.; Animägi, L.; Jürimäe, J. Longitudinal Associations of Body Fatness and Physical Fitness with Cognitive Skills in Preschoolers. Children (Basel, Switzerland) 2024, 11. [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, C.; Culkin, V.; Putkaradze, A.; Zeng, N. Effects of movement behaviors on preschoolers' cognition: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. The international journal of behavioral nutrition and physical activity 2025, 22, 12. [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Martínez, L.; Ramírez-Vélez, R.; García-Hermoso, A.; Izquierdo, M.; Alonso-Martínez, A.M. Improving Preschool Fundamental Motor Skills Through Interventions Targeting 24-Hour Movement Behaviors and Socioecological Factors: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of physical activity & health 2025, 22, 1076-1085. [CrossRef]

- Grady, A.; Lorch, R.; Giles, L.; Lamont, H.; Anderson, A.; Pearson, N.; Romiti, M.; Lum, M.; Stuart, A.; Leigh, L.; et al. The impact of early childhood education and care-based interventions on child physical activity, anthropometrics, fundamental movement skills, cognitive functioning, and social-emotional wellbeing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity 2025, 26, e13852. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Anthropometric characteristics and movement behaviors of preschool children stratified by body mass index (BMI) categories.

Table 1.

Anthropometric characteristics and movement behaviors of preschool children stratified by body mass index (BMI) categories.

| Variables |

All (n = 112) |

BMI < normal (n = 5) |

BMI = normal (n = 69) |

BMI > normal (n=38) |

P value |

| Age (years) |

4.10 ± 0.58 |

3.98 ± 0.56 |

4.09 ± 0.57 |

4.07 ± 0.57 |

1.000 €

0.205 π

0.034 β

|

| Weight (kg) |

18.6 ± 2.9 |

17.7 ± 3.1 |

18.6 ± 2.9 |

18.6 ± 3.0 |

0.005 €

<0.001π

0.001 β

|

| Height (cm) |

107.4 ± 6.8 |

105.8 ± 6.8 |

107.4 ± 6.8 |

107.1 ± 6.8 |

0.007 €

<0.001π

0.001 β

|

| Body mass index (BMI) |

16.1 ± 2.0 |

15.7 ± 2.1 |

16.1 ± 2.0 |

16.23 ± 2.0 |

0.041 €

<0.001π

<0.001 β

|

| Height-for-age z-score (HAZ) |

0.85 ± 1.20 |

0.58 ± 1.36 |

0.85 ± 1.20 |

0.89 ± 1.22 |

0.013 €

<0.001π

<0.001 β

|

| Weight-for-age z-score (WAZ) |

0.89 ± 1.26 |

0.75 ± 1.18 |

0.90 ± 1.26 |

0.88 ± 1.29 |

0.043 €

0.001π

0.007 β

|

| BMI-for-age z-score (BAZ) |

0.48 ± 1.37 |

0.19 ± 1.52 |

0.46 ± 1.37 |

0.55 ± 1.36 |

0.042 €

<0.001π

<0.001 β

|

| Light PA (LPA, min/day) a |

88.3 ± 24.7 |

79.8 ± 16.8 |

86.8 ± 24.6 |

93.3 ± 24.8 |

0.355 |

| Moderate PA (MPA, min/day) a |

61.8 ± 23.8 |

67.0 ± 24.2 |

59.9 ± 23.4 |

64.3 ± 24.0 |

0.550 |

| Vigorous PA (VPA, min/day) a |

18.8 ± 12.8 |

15.2 ± 10.8 |

18.9 ± 13.1 |

19.0 ± 12.3 |

0.802 |

| Moderate-to-vigorous PA (MVPA, min/day) a |

80.3 ± 34.9 |

82.2 ± 32.9 |

78.9 ± 34.9 |

83.4 ± 34.9 |

0.696 |

| Total PA (TPA, min/day) a |

168.6 ±55.1 |

162.0 ± 47.8 |

165.6 ± 56.0 |

176.7 ± 52.7 |

0.496 |

| Sedentary behavior (SB, min/day) a |

628.6 ± 56.5 |

653.1 ± 62.0 |

633.8 ± 57.1 |

612.2 ± 49.5 |

0.165 |

| Screen sedentary time (SST, min/day) b |

70.8 ± 33.3 |

72.2 ± 29.2 |

69.6 ± 32.1 |

73.1 ± 37.1 |

0.945 |

| Sleep duration (min/day) b |

640.4 ± 53.5 |

603.2 ± 22.2 |

641.8 ± 50.8 |

642.9 ± 59.8 |

0.159 |

Table 2.

Number and proportion of preschool children meeting 24-hour movement guidelines according to body mass index (BMI) categories.

Table 2.

Number and proportion of preschool children meeting 24-hour movement guidelines according to body mass index (BMI) categories.

| Variables |

Total n (%) |

BMI < normal (%) |

BMI = normal (%) |

BMI > normal (%) |

P value |

| ≥ 60 min/day of MVPA, n = 89 |

68 (76.4%) |

4 (80%) |

35 (71.4%) |

29 (82.9%) |

0.586 |

| ≥ 80 min/day of TPA, n = 89 |

36 (40.5%) |

4 (80%) |

16 (32.7%) |

16 (45.7%) |

0.076 |

| ≥ 60 min/day of MVPA and ≥ 180 min/day of TPA, n = 89 |

36 (40.4%) |

4 (80%) |

16 (32.7%) |

16 (45.7%) |

0.076 |

| ≤ 60 min/day of SST, n = 112 |

59 (52.7%) |

3 (60%) |

37 (53.6%) |

19 (50%) |

0.886 |

| 10–13 h/day of sleep, n = 112 |

91 (81.3%) |

4 (80%) |

55 (79.7%) |

32 (84.2%) |

0.640 |

| Meeting all 5 recommendations, n = 89 |

16 (18.0%) |

1 (20%) |

11 (22.5%) |

4 (11.4%) |

0.428 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).