1. Introduction

Long-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 20:5 n-3) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6 n-3) are well-known for their biological effects, whereas n-3 docosapentaenoic acid (DPA, 22:5 n-3) has been comparatively overlooked. Recent reviews highlight DPA as the “missing” omega-3 fatty acid, noting its presence in marine foods and mammalian tissues. DPA bridges the metabolic pathway between EPA and DHA and may exert its own effects, for instance via conversion to specialized pro-resolving mediators distinct from those derived from EPA or DHA. Emerging evidence suggests DPA has anti-inflammatory and cardiometabolic benefits, reinforcing its interest [

1,

2,

3,

4].

DPA occurs in certain fish oils, marine animal oils, and in trace amounts in terrestrial foods, as well as in human milk [

2]. However, it typically comprises only 1–5% of total fatty acids in these sources. For example, concentrated fish oils contain a few percent DPA, while krill oil or standard fish oils have <1%. As a result, isolating DPA in meaningful quantities is challenging. Researchers often lack access to DPA in pure form, in contrast to EPA/DHA which are readily available as purified ethyl esters or triglycerides. Thus, developing an efficient method to obtain DPA at preparative scale is important to enable further biological research [

1,

4].

Past efforts to purify DPA have been scarce and generally involved multi-step protocols. Notably, Yamamura and Shimomura achieved >99% pure DPA (and DHA) from single-cell oil using industrial-scale HPLC columns in series, with a reported production rate of ~70 g DPA per hour [

5]. This impressive output required specialized equipment of twin 400 mm i.d. columns, high-pressure pumps, not commonly accessible to academic labs. At laboratory scale, Mu et al. employed a combination of urea complexation and argentated silica column chromatography to enrich DPA from tuna oil, obtaining a fraction with ~22% DPA and an overall DPA yield of ~70% [

6]. While this approach confirmed the feasibility of concentrating DPA, it fell short of producing gram-quantities of pure DPA. More recently, other groups have reported partial enrichment of DPA by low-temperature crystallization or as specific derivatives – for instance, concentrating DPA as a diacylglycerol from microbial oils – but still did not reach high purity or scalability [

7,

8,

9]. A few patents have likewise been filed for DPA production or isolation methods (e.g. via algal sources or modified oils), underscoring the technical interest in this problem [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

In summary, there is a clear need for a practical, high-purity DPA isolation method that can be implemented with standard laboratory equipment. Here, we present a preparative chromatography protocol designed to yield tens of grams of DPA (ethyl ester form) at >98% purity. The method uses readily available C18 reversed-phase columns in a stacked configuration and an iterative purification loop strategy to incrementally enrich DPA. Importantly, the process incorporates solvent recycling and oxidative precautions to enhance sustainability and product quality. We detail the optimization of key parameters such as feedstock selection, flow rate, isocratic elution conditions, loading capacity, and fractionation strategy. We also compare the performance to prior ω-3 PUFA purification approaches. This work provides an enabling technique to supply high-purity DPA for nutritional biochemistry, lipid mediator research, and other applications that have been hampered by DPA’s limited availability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Commercial long-chain omega-3 fatty acid concentrates were obtained from Polaris (Quimper, France). The primary material was a fish oil ethyl ester blend (Omegavie 4020EE) containing approximately 40% total omega-3, enriched in EPA, DHA, and DPA. For method development, a DHA-rich concentrate (Omegavie DHA80) and krill oil were also tested. All oils were stored in amber containers under nitrogen. Butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT, 0.02% w/v) was added as an antioxidant. Beef liver (as a representative terrestrial source of DPA) was obtained fresh from a local butcher (Rennes, France) for preliminary extraction trials. HPLC-grade methanol and analytical-grade solvents were purchased from Fisher Scientific, and Milli-Q deionized water was used throughout. Boron trifluoride methanol reagent (14% BF₃) for methylation was from Sigma-Aldrich.

2.1.1. Fatty Acid Analysis

The fatty acid profiles of oils and tissue extracts were determined by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) of fatty acid methyl esters (FAME). Lipids from oils or homogenized tissues were extracted by the Folch method (chloroform/methanol) [

14]. Saponification (0.5 N NaOH in methanol, 70 °C, 30 min) was followed by methylation using BF₃–methanol (70 °C, 30 min) [

15]. The resulting FAME was extracted in hexane and analyzed on an Agilent 7890A GC coupled to a 5975C MS detector. A polar capillary column (BPX70, 60 m × 0.25 mm, 0.25 μm film) was used with helium as carrier gas (1.8 mL/min). The oven temperature was programmed from 150 °C, ramping 4 °C/min to 250 °C (hold 10 min). MS was operated in EI mode (70 eV) scanning m/z 50–550. Individual fatty acids were identified by retention time matching to authentic standards and by mass spectral library (NIST) matching for unknowns. Quantification was done by FID (flame ionization detection) on a parallel GC system using a 100 m CP-Sil 88 column, with C17:0 internal standard for calibration. All fatty acid compositions are reported as weight percent of total identified FAME.

2.2. Chromatography Setup

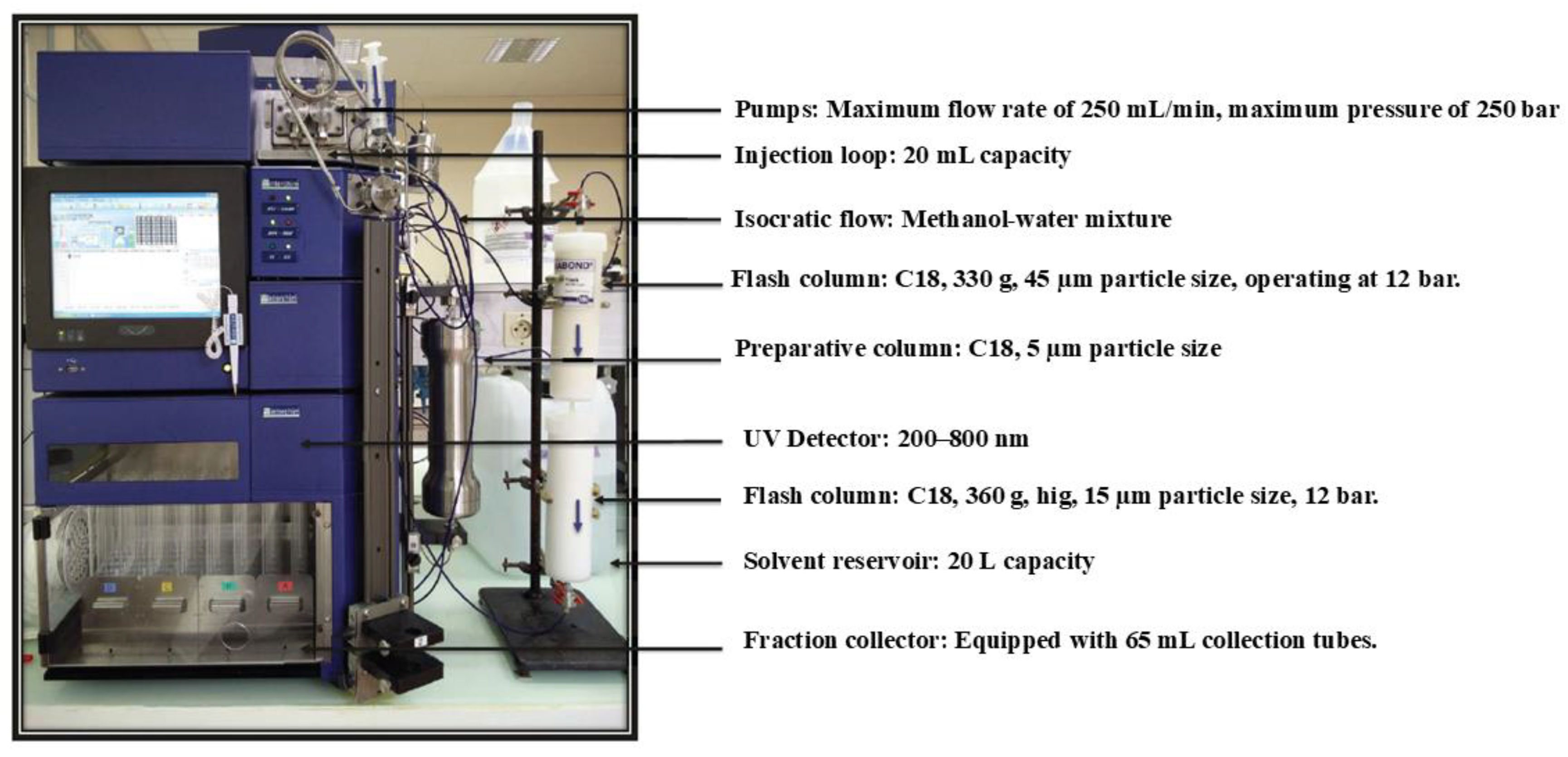

Preparative purification was performed on a modular flash chromatography system (Interchim puriFlash® equipped with a binary pump and UV detector) modified to accommodate high flow rates. Two C18 reversed-phase columns were connected in series: Column 1 (high-capacity) was a 45 μm silica C18 cartridge (approx. 250 × 100 mm, ~330 g packing), and Column 2 (high-performance) was a 15 μm C18 cartridge of the same dimensions. The combined bed length thus provided enhanced resolution and load tolerance. The mobile phase was methanol–water with 0.1% formic acid (to aid in UV detection and maintain consistency, though formic acid is not strictly required). Initial scouting runs compared 95:5 vs 92:8 MeOH/H₂O; the latter was adopted for production runs as described. The flow rate was set to 120 mL/min, and the system pressure stabilized around 200 bar (well within column limits). Temperature was ambient (20–25 °C). An injection loop of 20 mL volume was used to introduce the sample, which consisted of the oil concentrate diluted 1:10 (v/v) in methanol. Each injection thus contained ~1.5–2.0 g of oil (depending on oil density and composition).

Fractions were collected into glass tubes using an automated fraction collector triggered by time. We collected 60 mL per fraction (approximately every 30 s) based on prior calibration of the system dead volume and peak elution profile. The UV detector was set at 205 nm to monitor elusion; distinct increases in absorbance signaled the EPA, DPA, and DHA band passages, but GC analysis was used for definitive fraction mapping.

2.3. Iterative Purification Loop

After each 20 mL injection, collected fractions were processed as follows. Methanol was evaporated from each tube under vacuum or nitrogen sweep, and the residue weighed to determine recovery. A small aliquot of each dried fraction was derivatized to FAME and analyzed by GC–FID to determine its DPA content. Fractions were then grouped into four pools corresponding to the DHA-rich region (pool A), the transitional region before DPA (B), the DPA-rich peak (C), and the trailing region including n-6 DPA (D). Only pool C fractions (typically 4–6 tubes per run) were retained for the next purification cycle. Prior to reinjection, the pooled C fractions were combined and redissolved in methanol (up to 20 mL total) and an equal volume of water added to match the 92:8 mobile phase to avoid a strong solvent effect on the column. This solution was then injected as the feed for the next cycle. The columns were not regenerated between cycles beyond a brief flush with fresh mobile phase (15 min) to re-equilibrate isocratically. This cycle was repeated until the GC–FID analysis of pool C showed no detectable DHA. In practice, three iterations were sufficient to reach >98% purity for DPA. After the final cycle, the purified DPA fractions were combined and stored under nitrogen at –20 °C until use.

For maximum recovery, the pool D fractions containing DPA and n-6 DPA isomer can be further processed. In our case, we performed an additional polishing step on these fractions by using a preparative silver-ion column (25 cm × 2.0 cm i.d. glass column packed with 5% AgNO₃-silica). A 1 mL portion of the pool D concentrate was loaded and eluted with 95:5 methanol/water at 120 mL/min, which cleanly separated n-3 DPA from n-6 DPA (confirmed by GC). The n-3 DPA fraction from this step (>99% pure) was combined with the main batch. This optional step, however, added time and was only used to maximize final purity for analytical standard preparation. Most of the results reported were obtained without this silver column step, i.e. with final purity ~98% and a minor n-6 DPA presence (<1–2%).

2.4. Solvent Recycling

To curtail solvent use, we implemented a distillation recovery system. The collected methanol–water effluent from the flash system was funneled into a large round-bottom flask. Using a rotary evaporator, we distilled the bulk methanol (boiling ~65 °C) from the water. Because the mobile phase was only 8% water, once 92% of the volume was collected as distillate, the remainder was water-rich and was discarded. The distilled methanol was dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and reused for subsequent mobile phase makeup, after verifying that it produced no change in chromatographic behavior. All glassware and tubing in contact with solvents or lipids were rinsed with ethanol and acetone and dried between runs to prevent cross-contamination or microbial growth. Waste methanol from final residues was collected and handled according to institutional safety protocols [

12,

13].

2.5. Analytical and Quality Control

The purity of the final DPA preparation was assessed by multiple analytical techniques. Quantitative GC–FID was the primary measure of purity (area% of total FAME). GC–MS was used qualitatively to check for any unidentified components co-eluting with DPA. ^1H NMR spectra of the purified DPA ethyl ester were recorded on a 400 MHz spectrometer in CDCl₃ to confirm structural identity. Key NMR signals (triplets from terminal methyl protons, bis-allylic methylene protons around 2.8 ppm, and other methylene envelope patterns) matched literature values for 22:5 n-3. Oxidation metrics were measured on both the starting material and final product: peroxide value (PV) by the iodometric titration (AOCS Official Method Cd 8b-90) [

16], p-anisidine value by the AOCS Cd 18-90 colorimetric method [

16], and TBARS by the standard thiobarbituric acid assay (using malondialdehyde equivalents). In addition, an HPLC-fluorescence method for MDA (after derivatization to a fluorescent adduct) was used on select samples to verify TBARS results, following established protocols [

17]. UV absorbance spectra (200–300 nm) of the oils were recorded to detect conjugated diene or triene formation (signs of polyunsaturated lipid oxidation). All analyses confirmed that the processing did not introduce oxidation: PV remained <0.5 meq/kg, and no significant increase in UV absorbance at 233 nm or 270 nm was observed in the purified DPA compared to the fresh oil.

2.6. Statistical Note

Yields and purities reported are representative of at least three independent purification runs. Minor variations in results (±2–3%) were observed depending on ambient temperature and slight differences in column packing performance, but no systematic deviations were noted.

3. Results

3.1. Preparation and Selection of Food Sources

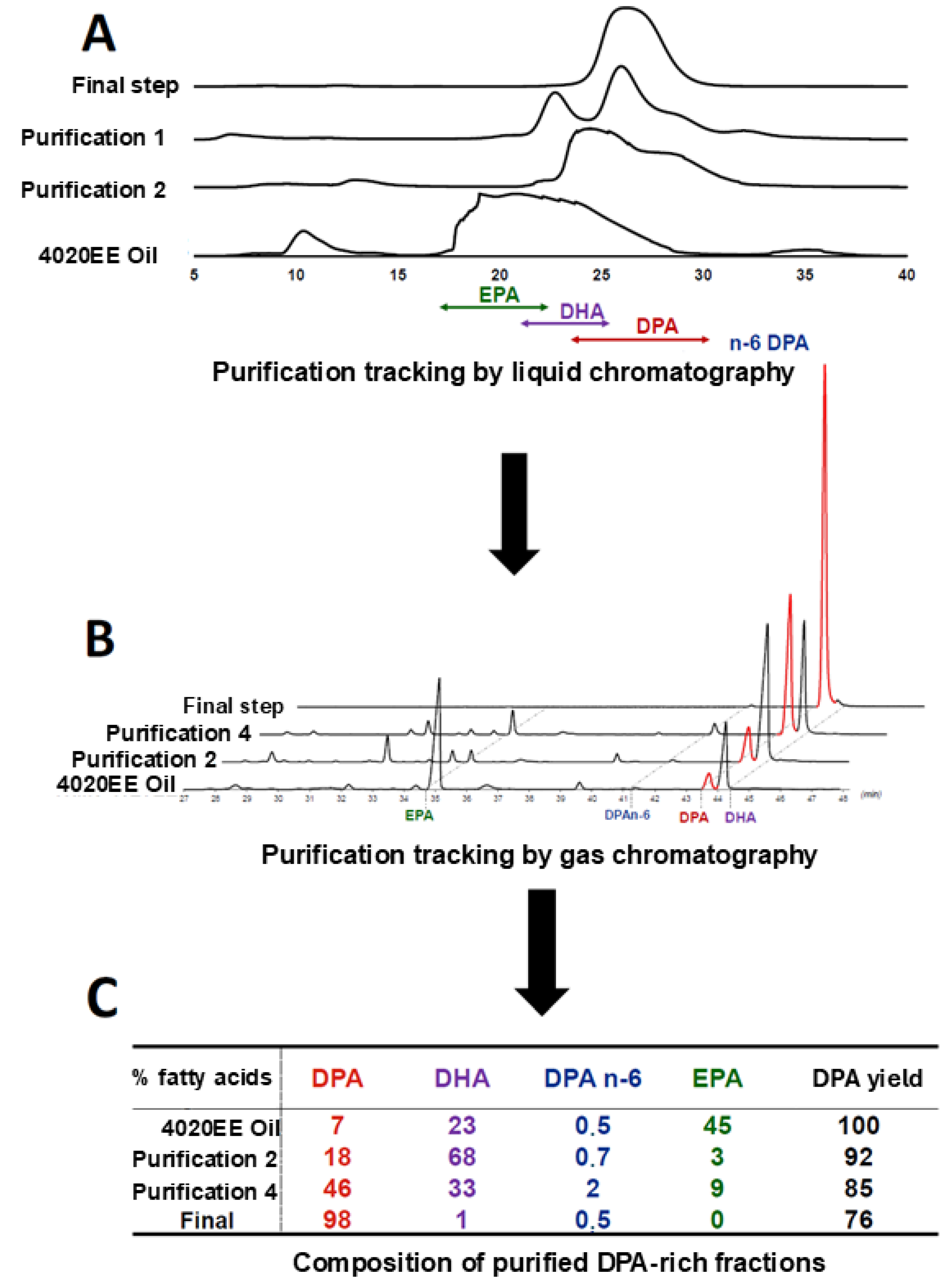

Although oils were stored under nitrogen, we detected trace lipid peroxidation (malondialdehyde, TBARS), consistent with the oxidative liability of highly unsaturated ethyl esters. A single −20 °C crystallization step removed aggregated residues including saturated lipids and oxidation by-products after which TBARS-derived malondialdehyde was no longer detectable in the supernatant. We next profiled candidate sources (fish oils, enriched n-3 LCPUFA concentrates, and calf liver) to identify an input that maximized DPA while limiting species known to compromise reversed-phase resolution. Across this panel, DPA ranged from 0.5% (krill oil) to 6.6% (Omegavie 4020EE®, Polaris) of total fatty acids (

Table 1).

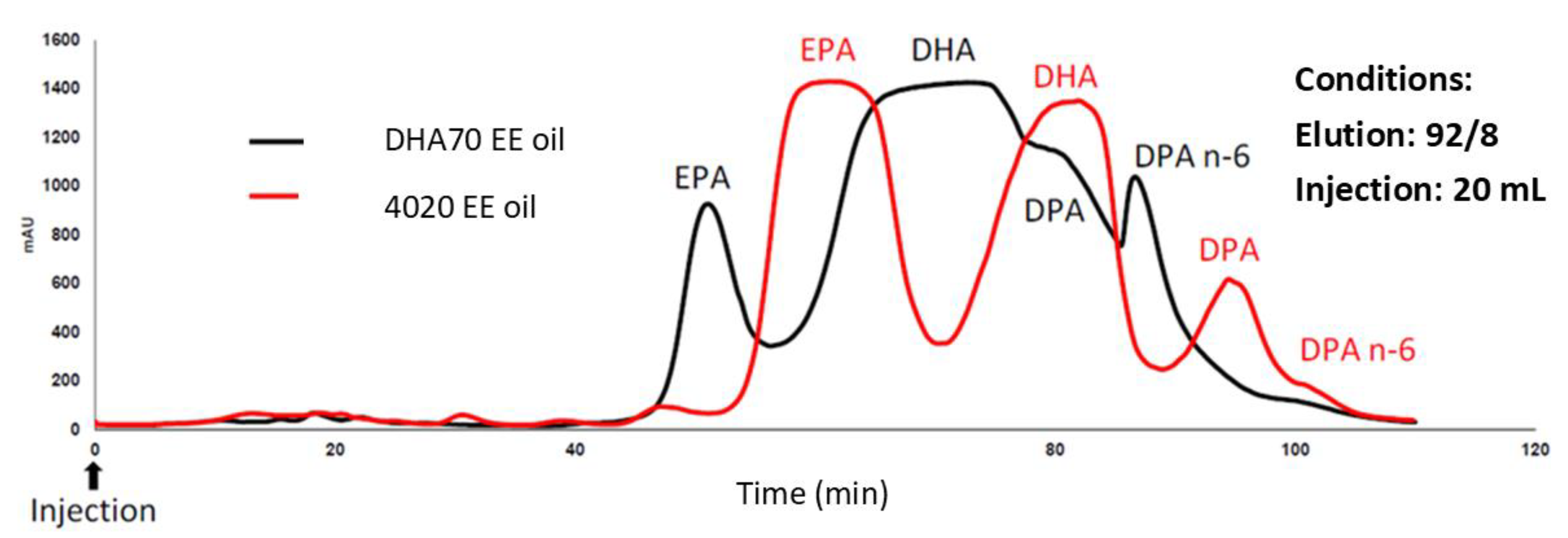

We selected 4020EE because it combined high DPA with lower DHA and n-6 DPA (22:5n-6). The two principal interferents partially co-elute with DPA on C18 while containing abundant EPA, which elutes well ahead of DPA and can be stripped early (

Figure 1).

Conversely, DHA-enriched oil (DHA80®) was deliberately used to stress-test the separation window, because under overloaded conditions the broad DHA band encroaches into the DPA region and defines the practical worst case for preparative resolution (

Figure 1).

3.2. Selection of Columns, Scale-Up, and Elution Optimization

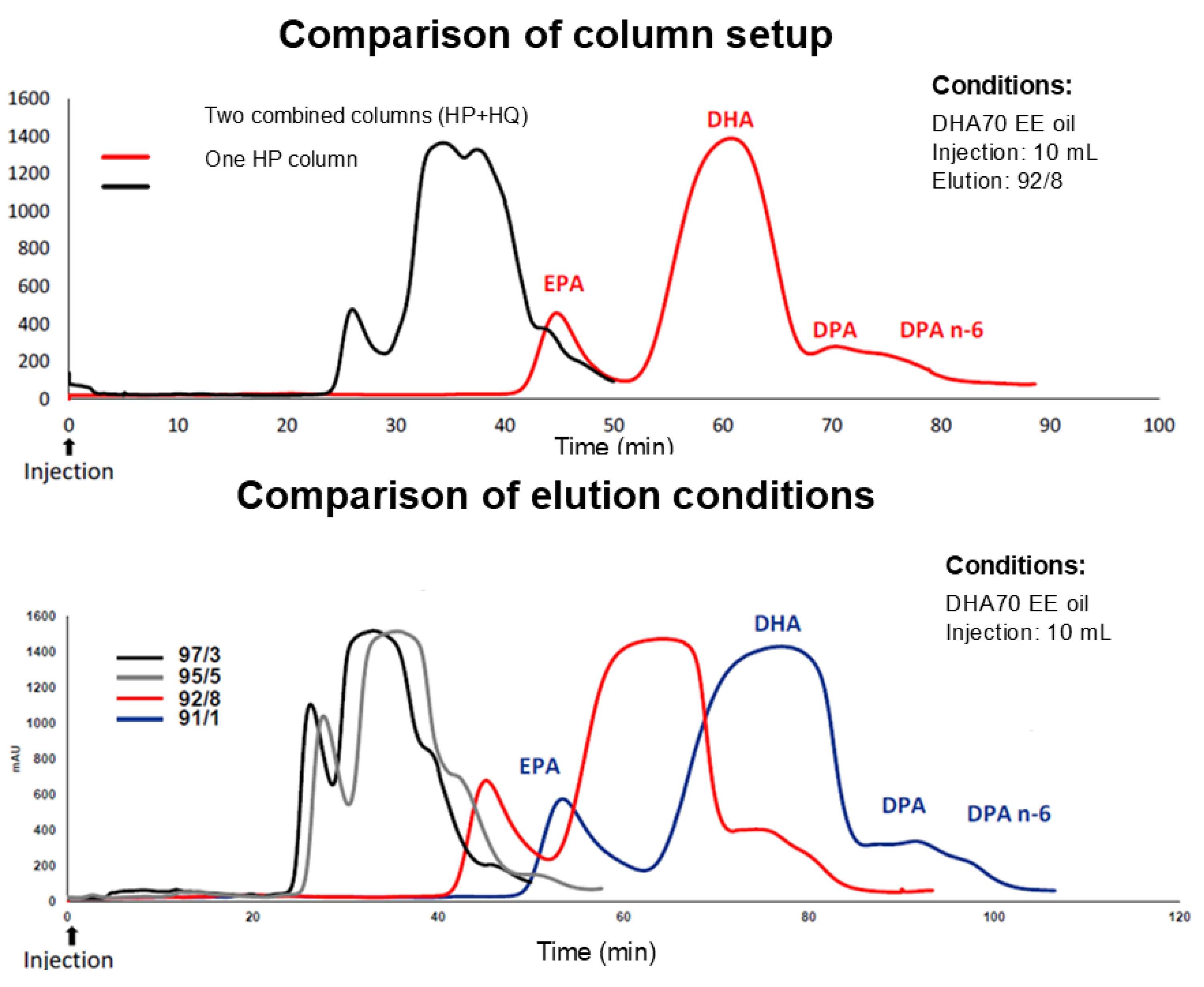

At small scale (15 µm C18 flash format; MeOH/H₂O 95/5), the HP column gave the best DHA–DPA resolution (Rs = 0.9) relative to HQ (Rs = 0.7) and HC (Rs = 0.5) (

Figure 2).

A MeOH/H₂O gradient (10% → 7% water) further increased DHA–DPA separation (best Rs = 1.4) on the HP column (

Figure 2).

Scale-up required a step change in loading: analytical-format capacity (30 g class columns; 150 µL oil) was incompatible with producing tens of grams of DPA within reasonable instrument time.

We moved to a two-column flash configuration, a high-performance C18 (15 µm, 330 g) paired with a higher-capacity C18 (45 µm, 330 g), to increase injected mass while maintaining usable selectivity (

Figure 3).

Relative to the HP column alone, the coupled system produced a 3.5-fold purer DPA fraction while only doubling run time, improving overall hourly productivity (

Figure 2).

Among ten MeOH/H₂O programs evaluated (90/10 to 99/1), we selected an isocratic 92/8 mode as the best compromise between throughput, robustness, and per-run recovery (

Figure 2).

Under these preparative conditions, DPA purification yield was 91–95% per run (

Figure 3).

Because coupling increased backpressure, we fixed flow at 120 mL/min, corresponding to the maximum pressure tolerated by the columns while retaining efficient cycle times (

Figure 3).

3.3. Purification of DPA and n-3 LCPUFAs

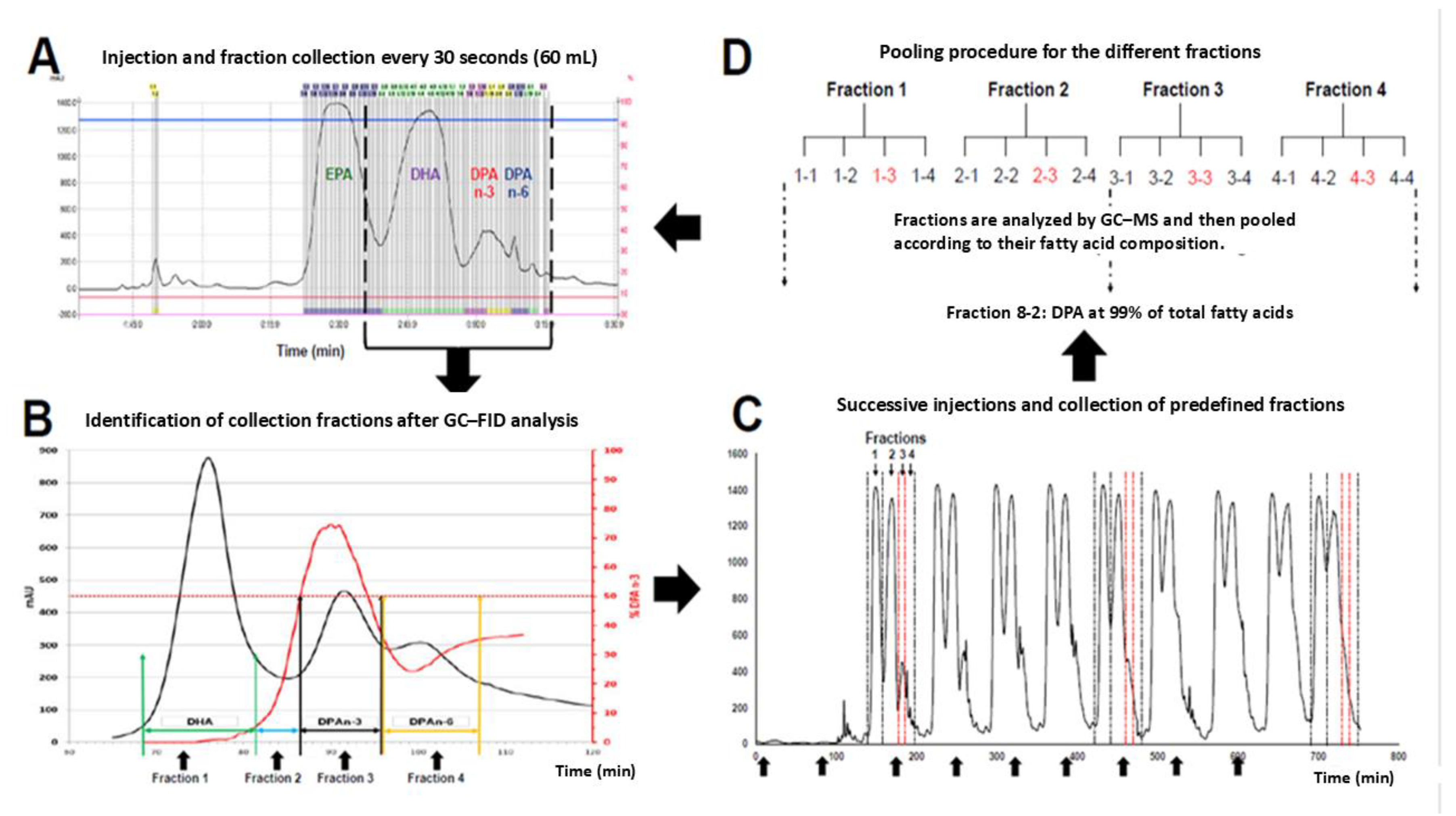

We implemented a closed-loop, reinjection-based workflow in which each overloaded flash run is fractionated, analytically triaged, pooled by composition, and reinjected to progressively sharpen the DPA-enriched band (

Figure 4).

After equilibration, a 20 mL injection of 4020EE (in 10% methanol) was separated on the two-column system, and fractions were collected every 30 s (≈60 mL) (

Figure 4A).

Each fraction was evaporated, weighed, and analyzed by GC to map DPA purity versus retention time, enabling objective definition of collection windows (

Figure 4B).

We then partitioned the chromatogram into four operational pools: a DHA-rich region (>85% DHA), two mixed transition regions (<50% DPA), and a DPA-enriched region (>50% DPA) designated for reinjection (

Figure 4B).

Successive injections accumulated material into these predefined pools until sufficient mass was reached, at which point pooled fractions were reinjected to iterate the enrichment cycle (

Figure 4C–D).

After three cycles, pooling and reinjection were continued until >98% DPA (of total fatty acids) was achieved, enabling production of several tens of grams of highly purified DPA (

Figure 5).

To accelerate throughput, the first two cycles were run at room temperature with MeOH/H₂O 99/1, prioritizing rapid removal of EPA (45% of 4020EE) and partial DHA depletion rather than full DHA–DPA resolution (

Figure 5).

Consistent with that design, DPA purity increased only modestly (7% → 18%) after these two fast cycles, but the step sharply reduced the volume requiring higher-resolution processing from cycle three onward (

Figure 5).

Subsequent cycles used the optimized 92/8 isocratic mixture to restore selectivity while maintaining preparative throughput (

Figure 2).

A remaining bottleneck was the n-3 DPA / n-6 DPA pair, which could not be resolved on the flash system under any tested conditions.

To recover DPA from the terminal mixed fraction (60% DPA / 40% DPA n-6), we used a preparative C18 column with MeOH/H₂O 95/5, collected the DPA peak (>99% purity), and combined it with the main DPA pool. Under this integrated scheme, the overall DPA purification yield reached 76% (

Figure 5).

3.4. Laboratory Workflow Management and Limitations

We selected fatty acid ethyl esters as the purification target because they can be directly incorporated into semi-synthetic diets and reflect the dominant commercial form of enriched n-3 LCPUFA oils, improving accessibility and cost realism for in vivo programs. Newer market oils enriched in EPA+DPA with minimal DHA could compress cycle count and solvent burden under this workflow.

Although gradients improved DHA–DPA resolution at small scale, we retained isocratic operation at preparative scale to eliminate re-equilibration overhead and to support successive injections as a practical productivity lever.A key limitation was flash column degradation during successive injections, exacerbated by the absence of true reverse-flush cleaning on this platform (

Figure 4C).

The coupled-column design partially mitigated this by using the first column as a sacrificial capture bed for accumulating impurities, preserving the resolving performance of the second (15 µm) column.

Finally, scale-up is constrained as much by logistics as by chromatography: in this program, processing 1.8 L of oil required 8,500 L methanol with 70% recycled by distillation. Added to this substantial ethanol volumes for water removal are needed, alongside high-flow solvent handling (120 mL/min) and solvent-vapor safety controls [

12,

13].

4. Discussion

n-3 Docosapentaenoic acid (DPA) interconverts with EPA and DHA. Yet, also contributes to a dedicated pool of bioactive lipid mediators, including DPA-derived protectins and resolvins linked to inflammation resolution in mucosal tissues [

1,

2,

3,

4,18]. This combination of biological relevance and limited commercial availability has made access to well-defined DPA a practical bottleneck for mechanistic and translational studies.

Our results show that this bottleneck can be reduced with widely available reversed-phase equipment by treating preparative LC as an iterative enrichment problem rather than a single-pass separation. The stacked C18 configuration provides a pragmatic balance between resolving power and loading capacity, while the isocratic 92:8 MeOH/H2O system simplifies re-equilibration and supports routine solvent recovery. In this context, the key design principle is the purification loop: only the central, DPA-rich window is reinjected, progressively compressing the compositional space until DHA and EPA are effectively excluded from the circulating pool. The approach is therefore robust to moderate peak overload and day-to-day variability, because enrichment depends on repeated selection of the same chromatographic region.

Compared with earlier laboratory-scale protocols that produced DPA as an enriched fraction or required specialized stationary phases, the present workflow offers a different trade-off. Argentated media can deliver higher isomeric selectivity [

7,

8], and industrial-scale HPLC trains have achieved very high purity and throughput in optimized settings [

5]. However, these approaches increase cost and operational complexity. Also, concerns about column lifetime and solvent constraints might appear. Counter-current chromatography is another scalable option for highly unsaturated lipids [

10,

11]. However, instrument access and biphasic solvent development remain barriers in many laboratories. Our data shows that for most academic settings, repeated isocratic C18 cycles can reach a purity threshold (>98%) that is sufficient for analytical validation and downstream biology, with the remaining limitation being partial co-elution of the n-6 DPA isomer at the tail of the DPA band.

Finally, oxidation control is not a secondary detail but a defining requirement for any multi-cycle PUFA isolation. The low peroxide and p-anisidine values, together with the absence of detectable TBARS in the processed material, indicate that antioxidant protection, cold handling, and short residence times can preserve chemical integrity even over repeated injections. Incorporating solvent recovery further improves practicality and aligns the workflow with emerging expectations for greener preparative chromatography [

12,

13].

5. Conclusions

This work provides a compact, reproducible route to high-purity n-3 DPA ethyl ester at the gram-to-tens-of-grams scale using an iterative, windowed chromatographic enrichment approach. The strategy is operationally straightforward, compatible with standard laboratory chromatography, and should be adaptable to other low-abundance LCPUFAs and related lipid targets where neighboring species partially overlap, improving access to purified material for downstream analytical, formulation, and biological studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, and visualization: G.S.-G. and G.D.; supervision and project administration: G.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

None declared.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| C18 |

octadecylsilane-bonded silica |

| DPA |

docosapentaenoic acid |

| DHA |

docosahexaenoic acid |

| EPA |

eicosapentaenoic acid |

| EI |

electron ionization |

| FAME |

fatty acid methyl ester |

| GC |

gas chromatography |

| GC–FID |

gas chromatography–flame ionization detection |

| GC–MS |

gas chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| HC |

high-capacity |

| HP |

high-performance |

| HQ |

high-quality |

| HPLC |

high-performance liquid chromatography |

| HPLC–FL |

high-performance liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection |

| i.d., |

internal diameter |

| LC |

liquid chromatography |

| LCPUFA |

long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid |

| MDA |

malondialdehyde |

| MeOH |

methanol |

| NMR |

nuclear magnetic resonance |

| NIST |

National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| PUFA |

polyunsaturated fatty acid |

| PV |

peroxide value |

| TBARS |

thiobarbituric acid reactive substances |

| UV |

ultraviolet |

References

- Drouin, G; Rioux, V; Legrand, P. The n-3 docosapentaenoic acid (DPA): A new player in the n-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acid family. Biochimie 2019, 159, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, G; Cameron-Smith, D; Garg, M; Sinclair, AJ. Docosapentaenoic acid (22:5n-3): a review of its biological effects. Prog Lipid Res 2011, 50(1), 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghasemi Fard, S; Cameron-Smith, D; Sinclair, AJ. n - 3 Docosapentaenoic acid: the iceberg n - 3 fatty acid. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2021, 24(2), 134–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Byelashov, OA; Sinclair, AJ; Kaur, G. Dietary sources, current intakes, and nutritional role of omega-3 docosapentaenoic acid. Lipid Technol 2015, 27(4), 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yamamura, R.; Shimomura, Y. Industrial High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Purification of Docosahexaenoic Acid Ethyl Ester and Docosapentaenoic Acid Ethyl Ester from Single-Cell Oil. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1997, 74, 1435–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.; Jin, Q.; Xu, X.; Li, B.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z. Combined Urea Complexation and Argentated Silica Gel Column Chromatography for Concentration and Separation of PUFAs from Tuna Oil: Based on Improved DPA Level. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2016, 93(8), 1157–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillon, JT; Aponte, JC; Tarozo, R; Huang, Y. Purification of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids from fish oil using silver-thiolate chromatographic material and high performance liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr A 2013, 1312, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czajkowska-Mysłek, A; Siekierko, U; Gajewska, M. Application of Silver Ion High-Performance Liquid Chromatography for Quantitative Analysis of Selected n-3 and n-6 PUFA in Oil Supplements. Lipids 2016, 51(4), 413–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sang, M; Pan, N; Wu, J; Chen, X; Cai, S; Fang, H; Xiao, M; Jiang, X; Liu, Z. Reversed-Phase Medium-Pressure Liquid Chromatography Purification of Omega-3 Fatty Acid Ethyl Esters Using AQ-C18. Mar Drugs 2024, 22(6), 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Li, H; Yang, Z; Cao, X; Han, T; Pei, H. Separation of high-purity eicosapentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid from fish oil by pH-zone-refining countercurrent chromatography. J Sep Sci. 2019, 42(15), 2569–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IIto, Y. pH-zone-refining counter-current chromatography: origin, mechanism, procedure and applications. J Chromatogr A 2013, 1271(1), 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yabré, M; Ferey, L; Somé, IT; Gaudin, K. Greening Reversed-Phase Liquid Chromatography Methods Using Alternative Solvents for Pharmaceutical Analysis. Molecules 2018, 23(5), 1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Aboagye, E.A.; Mills-Lin, L.; Struebing, H.; Meier-Michels, E.M.; Roger, J.M.; Siirola, E. Systems-Level Roadmap for Solvent Recovery and Reuse in Pharmaceutical Manufacturing. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9(39), 13172–13185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folch, J.; Lees, M.; Sloane Stanley, G.H. A Simple Method for the Isolation and Purification of Total Lipides from Animal Tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 1957, 226, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, W.R.; Smith, L.M. Preparation of Fatty Acid Methyl Esters and Dimethylacetals from Lipids with Boron Fluoride–Methanol. J. Lipid Res. 1964, 5, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AOCS. Official Methods and Recommended Practices of the AOCS, 7th ed.; American Oil Chemists’ Society: Urbana, IL, USA, 2006; p. Methods Cd 18-90 and Cd 8b-90. [Google Scholar]

- Domijan, A.M.; Ralić, J.; Radić Brkanac, S.; Rumora, L.; Žanić-Grubišić, T. Quantification of Malondialdehyde by HPLC-FL—Application to Various Biological Samples. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2015, 29(1), 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).