Submitted:

16 January 2026

Posted:

19 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Methods

Research Design

Eligibility Criteria

- Types of Studies: This study reviews RCTs assessing the impact of holistic, non-surgical management strategies on outcomes related to low back pain. Holistic strategies include, but are not limited to, exercise therapy, patient education, psychological therapies (such as cognitive behavioural therapy or mindfulness), manual therapy as adjuncts, and multidisciplinary rehabilitation programmes. The studies included were published in English-language conference proceedings and peer-reviewed journals. Grey literature identified via hand searches and reputable trial registries were also considered.

- Types of Participants: This review included studies involving adult participants aged ≥ 18 years diagnosed with acute, subacute, or chronic low back pain, irrespective of gender or ethnicity. Both specific and non-specific LBP populations were eligible provided the intervention aligned with holistic, non-surgical management strategies and the study setting was clearly described.

- Intervention: We selected RCTs focusing on holistic, non-surgical interventions for LBP, either unimodal (e.g., structured exercise, psychological therapy, or education) or multimodal (e.g., exercise combined with education and/or psychological therapy). Only supervised or structured programmes were included. These programmes had no limitations regarding intervention dosage, form, frequency, duration, intensity, or post-intervention follow-up time.

- Types of Control: Our study involved randomized trials comparing holistic interventions against one or more of the following control categories:

- Usual care / Waitlist (No-Contact Control Group): Participants received standard care or were placed on a waitlist with no additional structured intervention.

- Different Interventions (Active Control Group): Participants received alternative interventions such as pharmacological management, sham procedures, education only, advice leaflets, or self-directed exercise programmes.

- Social Support (Social Control Group): Participants received non-specific social or support-based contacts without the structured therapeutic components.

- Timing: Only studies that completed outcome assessments at the end of the intervention or during follow-up periods of up to six months post-intervention were included.

- Types of Outcomes: Studies were included if they measured changes in outcomes relevant to low back pain management. The primary outcome was pain intensity. All studies focusing on these patient-centered and functional outcomes were included, analysed, and combined where appropriate. Clinical outcomes were evaluated and ranked, preserving the initial descriptions in the source texts.

- Primary Outcomes: Pain intensity: The primary outcome is pain intensity, usually measured using validated tools such as the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) or the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS). Pain assessments capture the severity and change in back pain symptoms over time and across interventions.

- Studies without supervised or structured holistic/non-surgical intervention components.

- Studies that implemented interventions unrelated to holistic or non-surgical care of low back pain (e.g., surgical procedures, pharmacological-only trials).

- Studies that failed to assess the main outcomes of interest such as pain intensity, functional ability, balance, muscle strength, or quality of life.

- Publications comprising opinion pieces, narrative reviews, systematic reviews, case reports, or correspondence without a clear methodology or primary data description.

- In instances of multiple publications from the same research project, the most recent or most complete publication on the subject was included.

Information Sources

Search Strategy

Study Record and Data Management

Data Collection Processes

Risks of Bias Assessment in Individual Studies

Data Collection Processes

Statistical Methodology

Data Analysis

Rating Quality of Evidence and Strength of Recommendation

Evidence Statement and Quality Assessment

- High Quality: Implies that additional research is unlikely to alter the effect estimates.

- Moderate Quality: Suggests that further research could significantly impact the effect estimates.

- Low Quality: Indicates that additional research is very likely to alter or significantly change the estimate.

- Level 1 Evidence: High-quality randomized controlled trials (RCTs) with larger samples (PEDro rated good or excellent and sample size > 50).

- Level 2 Evidence: Lower-quality RCTs with fair or poor ratings and/or a sample size less than 50

Report of Review

Results

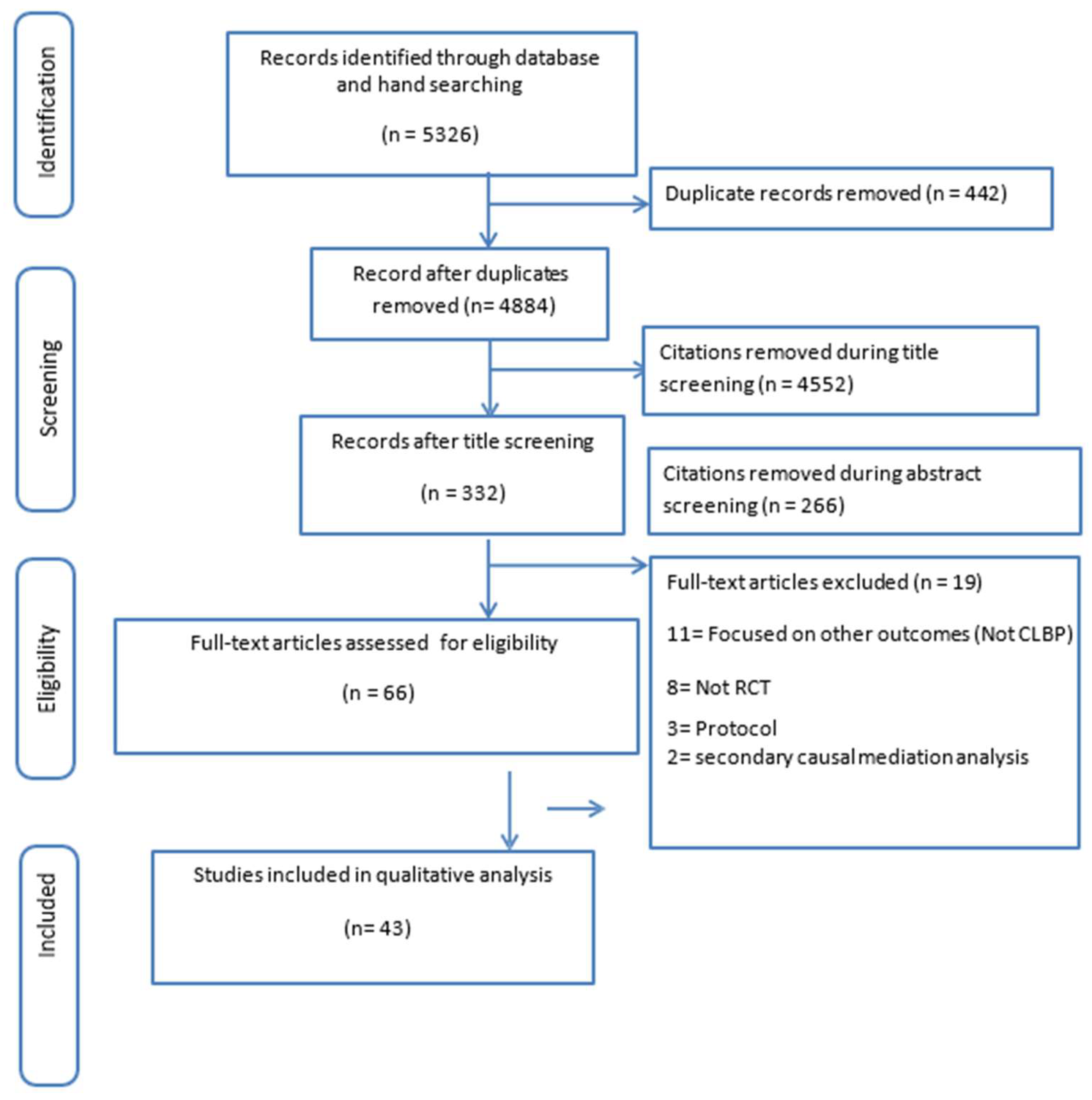

Study Selection

Qualitative and Quantitative Synthesis

Risk of Bias in Included Studies

Selection Bias and Eligibility Criteria

Performance and Detection Bias

Attrition Bias and Outcome Reporting

Outcomes Reported in Included Studies

Pain Intensity

Muscle Function

Balance, Mobility, and Physical Performance

Functional Disability

Work Participation and Broader Life Impact

Effects of Interventions

Physically Oriented Exercise Therapies

Mind–Body and Psychological Therapies

Manual and Body-Based Therapies

Technology-Assisted and Adjunctive Modalities

Integrated and Multimodal Interventions

Level of Evidence

Grade of Evidence for the Review

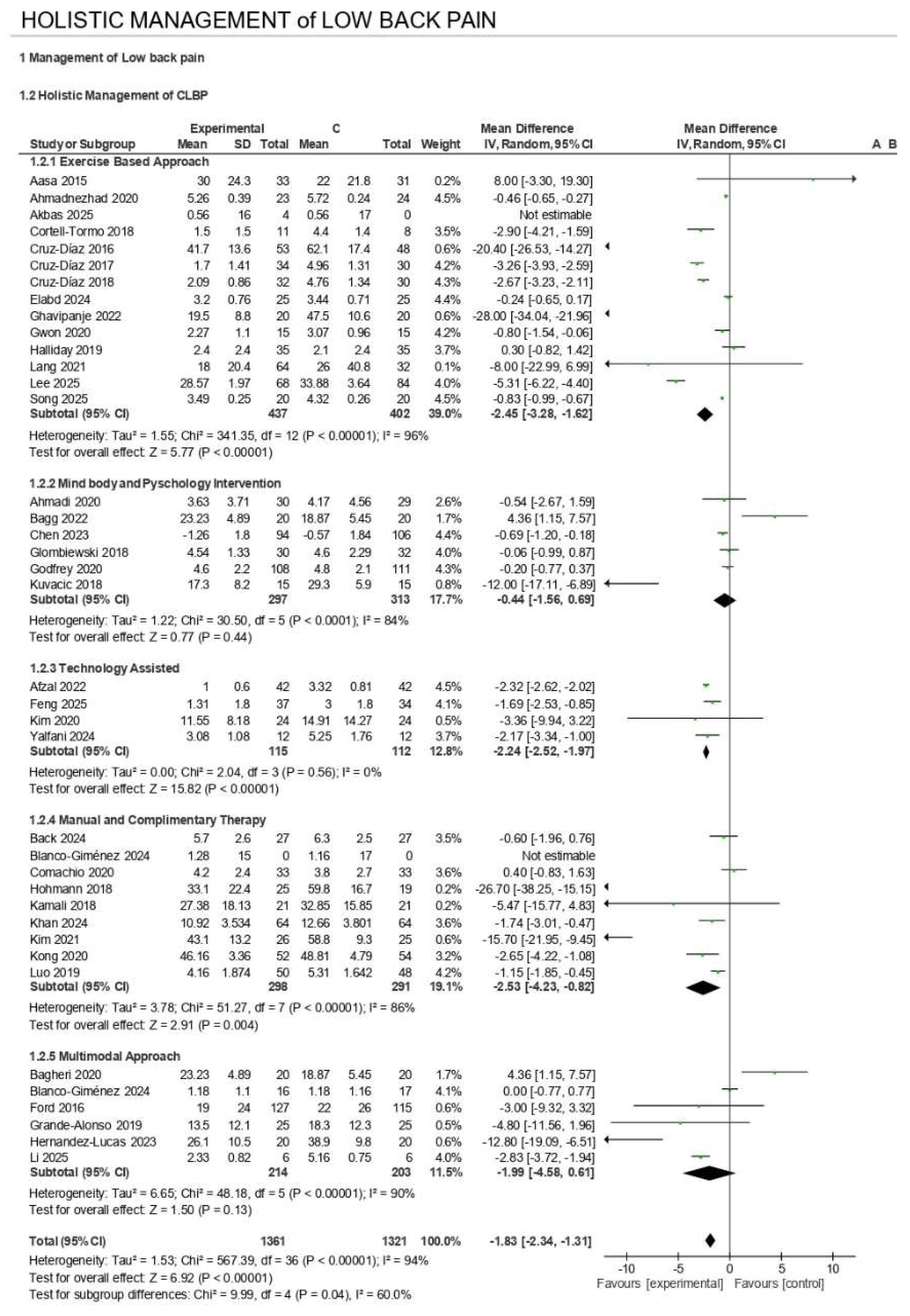

Meta-Analyses – Effects of Holistic Interventions

Exercise-Based Interventions

Mind–Body and Psychology Interventions

Technology-Assisted Interventions

Manual and Complementary Therapy

Multimodal Interventions

Subgroup with the Highest Effect

Discussion

The Efficacy of Holistic Interventions on Primary Outcomes

Alignment with Existing High-Quality Evidence and Guidelines

Comparative Effectiveness Across Intervention Types

The Recommended Holistic Prescriptions for Chronic Low Back Pain Include

Reasons for Non-Significant Effects Reported in Some of the Studies

For Quality-of-Life Outcomes

Why the Interventions Should Not Be Overgeneralized in the Population Group

The Intervention Adverse Effects

Quality of Evidence

Conclusions

Recommendations for Practice and Future Research

A. Clinical Practice Recommendations

B. Recommendations for Future Research

Limitations

Closing Remark

List of Abbreviations

| ACSM | American College of Sports Medicine |

| ACT | Acceptance and Commitment Therapy |

| ADIM | Abdominal Drawing-In Maneuver |

| AHAS | Asymmetry of Hip Abductor Strength |

| ALL | Anterior Longitudinal Ligament |

| ASLR | Active Straight Leg Raise |

| BBQ | Back Beliefs Questionnaire |

| BGA | Behavioural Graded Activity |

| BHT | Breath Hold Time |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| CBT | Cognitive Behavioural Therapy |

| CDSR | Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews |

| CENTRAL | Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials |

| CES-D | Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale |

| CFT | Cognitive Functional Therapy |

| CG | Control Group |

| CHT | Commitment to Health Theory |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| CINAHL | Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature |

| CLBP | Chronic Low Back Pain |

| CNSLBP | Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain |

| CPM | Conditioned Pain Modulation |

| CROB | Cochrane Risk of Bias |

| CT | Cognitive Therapy |

| DST | Dynamic Systems Theory |

| EA | Electroacupuncture |

| EARS | Exercise Adherence Rating Scale |

| EG | Experimental Group |

| EMG | Electromyography |

| ESWT | Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy |

| FABQ | Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire |

| GBD | Global Burden of Disease |

| GRADE | Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations |

| GROC | Global Rating of Change |

| HBM | Health Belief Model |

| HRQOL / HRQoL | Health-Related Quality of Life |

| IASP | International Association for the Study of Pain |

| IMT | Inspiratory Muscle Training |

| IPAQ | International Physical Activity Questionnaire |

| ITT | Intention-To-Treat |

| LBP | Low Back Pain |

| LMICs | Low- and Middle-Income Countries |

| MA | Manual Acupuncture |

| MBR | Multidisciplinary Biopsychosocial Rehabilitation |

| MBSR | Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction |

| MCE | Motor Control Exercises |

| MD | Mean Difference |

| MDT | McKenzie Method |

| MeSH | Medical Subject Headings |

| MODI | Modified Oswestry Disability Index |

| MODQ | Modified Oswestry Disability Questionnaire |

| N/A | Not Applicable |

| NICE | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence |

| NIHR | National Institute of Health Research |

| NPRS | Numerical Pain Rating Scale |

| NRS | Numerical Rating Scale |

| NSAIDs | Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs |

| ODI | Oswestry Disability Index |

| OMT | Orthopaedic Manual Therapy |

| PACT | Physiotherapy informed by Acceptance and Commitment Therapy |

| PEDro | Physiotherapy Evidence Database |

| PHQ-8 | Patient Health Questionnaire-8 |

| PICOS | Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes, Study Design |

| PLL | Posterior Longitudinal Ligament |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| PSFS | Patient-Specific Functional Scale |

| PT | Physical Therapy / Physiotherapy |

| QBPDS | Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale |

| QoL / QOL | Quality of Life |

| RA | Rectus Abdominis |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| RMDQ | Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire |

| RR | Respiratory Rate; Risk Ratio |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| SDNN | Standard Deviation of NN Intervals (Heart Rate Variability) |

| SDT | Self-Determination Theory |

| SEM | Social Ecological Model; Structural Equation Modeling |

| SES | Schmerzempfindungs-Skala (Pain Perception Scale) |

| SF-12 / SF-36 | Short Form Health Survey (12 or 36 items) |

| SHR | Simulated Horseback Riding |

| SMD | Standardised Mean Difference |

| SMR | Self-Myofascial Release |

| SSE | Stabilization Exercises |

| STB | Stabilization |

| TCM | Traditional Chinese Medicine |

| TENS | Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation |

| TrA | Transversus Abdominis |

| TSK | Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia |

| TTM | Transtheoretical Model |

| TUG | Timed Up and Go |

| UC | Usual Care |

| VAS | Visual Analogue Scale |

| VR / VRT | Virtual Reality (Training) |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| WHOQOL | World Health Organization Quality of Life |

| WMD | Weighted Mean Difference |

| YLDs | Years Lived with Disability |

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Consent for Publication

Availability of Data and Materials

Competing Interests

Funding

Authors’ Contributions

Authors’ Information

References

- World Health Organization WHO. Low back pain. World Health Organization: WHO [Internet], 19 Jun 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/low-back-pain? (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Gill, T.K.; Mittinty, M.M.; March, L.M.; Steinmetz, J.D.; Culbreth, G.T.; Cross, M.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of other musculoskeletal disorders, 1990–2020, and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. The Lancet Rheumatology. 2023, 5, e670–e682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchbinder, R.; Underwood, M.; Hartvigsen, J.; Maher, C.G. The Lancet Series call to action to reduce low value care for low back pain: an update. Pain. 2020, 161, S57–S64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartvigsen, J.; Hancock, M.J.; Kongsted, A.; Louw, Q.; Ferreira, M.L.; Genevay, S.; et al. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet 2018, 391, 2356–2367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Main, C.J.; George, S.Z. Psychosocial influences on low back pain: why should you care? Physical therapy. 2011, 91, 609–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ageing (AAH), H. WHO guideline for non-surgical management of chronic primary low back pain in adults in primary and community care settings. World Health Organization [Internet], 7 Dec 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240081789 (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Hayden, J.A.; Ogilvie, R.; Kashif, S.; Singh, S.; Boulos, L.; Stewart, S.A.; et al. Exercise treatments for chronic low back pain: a network meta-analysis - PMC. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2023, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas, M.K.; Linton, S.J.; Watson, P.J.; Main, C.J. Early Identification and Management of Psychological Risk Factors (“Yellow Flags”) in Patients With Low Back Pain: A Reappraisal. Physical Therapy 2011, 91, 737–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherkin, D.C.; Sherman, K.J.; Balderson, B.H.; Cook, A.J.; Anderson, M.L.; Hawkes, R.J.; et al. Effect of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction vs Cognitive Behavioral Therapy or Usual Care on Back Pain and Functional Limitations in Adults With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2016, 315, 1240–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamper, S.J.; Apeldoorn, A.T.; Chiarotto, A.; Smeets, R.J.E.M.; Ostelo, R.W.J.G.; Guzman, J.; et al. Multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation for chronic low back pain. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2014, 2014, CD000963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, N.E.; Anema, J.R.; Cherkin, D.; Chou, R.; Cohen, S.P.; Gross, D.P.; et al. Prevention and treatment of low back pain: evidence, challenges, and promising directions. Lancet 2018, 391, 2368–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geneen, L.J.; Moore, R.A.; Clarke, C.; Martin, D.; Colvin, L.A.; Smith, B.H. Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2017, 4, CD011279. [Google Scholar]

- Maher, C.; Underwood, M.; Buchbinder, R. Non-specific low back pain. Lancet 2017, 389, 736–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Traeger, A.C.; Reed, B.; Hamilton, M.; O’Connor, D.A.; Hoffmann, T.C.; et al. Clinician and patient beliefs about diagnostic imaging for low back pain: a systematic qualitative evidence synthesis. BMJ open. 2020, 10, e037820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane [Internet]. [cited 2025 Dec 16]. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Available online: https://www.cochrane.org/authors/handbooks-and-manuals/handbook.

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; 20 Sep 2019.

- Maher, C.G.; Sherrington, C.; Herbert, R.D.; Moseley, A.M.; Elkins, M. Reliability of the PEDro scale for rating quality of randomized controlled trials. Physical therapy 2003, 83, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cashin, A.G.; McAuley, J.H. Clinimetrics: Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) Scale. Journal of physiotherapy 2020, 66, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teasell, R.W.; Foley, N.C.; Bhogal, S.K.; Speechley, M.R. An evidence-based review of stroke rehabilitation. Topics in stroke rehabilitation 2003, 10, 29–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, H.D. Systematic Reviews to Answer Health Care Questions; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Aasa, B.; Berglund, L.; Michaelson, P.; Aasa, U. Individualized Low-Load Motor Control Exercises and Education Versus a High-Load Lifting Exercise and Education to Improve Activity, Pain Intensity, and Physical Performance in Patients With Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy 2015, 45, 77–85. [Google Scholar]

- Afzal, M.W.; Ahmad, A.; Mohseni Bandpei, M.A.; Gillani, S.A.; Hanif, A.; Sharif Waqas, M. Effects of virtual reality exercises and routine physical therapy on pain intensity and functional disability in patients with chronic low back pain. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association 2022, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, H.; Adib, H.; Selk-Ghaffari, M.; Shafizad, M.; Moradi, S.; Madani, Z.; et al. Comparison of the effects of the Feldenkrais method versus core stability exercise in the management of chronic low back pain: a randomised control trial. Clinical Rehabilitation 2020, 34, 1449–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadnezhad, L.; Yalfani, A.; Gholami Borujeni, B. Inspiratory Muscle Training in Rehabilitation of Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of sport rehabilitation 2020, 29, 1151–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbaş, E.; Özdemir, M.; Akbaş, A.; Usgu, S.; Bulut, H.T. Investigation of the effect of different intensity stabilization exercises on core muscle stiffness and pain in chronic low back pain: a single-blind, randomized controlled trial. Rheumatology international 2025, 45, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Back, C.G.N.; Peron, R.; Lopes, C.V.R.; de Souza, J.V.E.; Liebano, R.E. Immediate effect of extracorporeal shockwave therapy in patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain: A randomized placebo-controlled triple-blind trial. Clinical Rehabilitation 2025, 39, 701–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagg, M.K.; Wand, B.M.; Cashin, A.G.; Lee, H.; Hübscher, M.; Stanton, T.R.; et al. Effect of Graded Sensorimotor Retraining on Pain Intensity in Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain. JAMA 2022, 328, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, R.; Hedayati, R.; Ehsani, F.; Hemati-Boruojeni, N.; Abri, A.; Taghizadeh Delkhosh, C. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy With Stabilization Exercises Affects Transverse Abdominis Muscle Thickness in Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Double-Blinded Randomized Trial Study. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics 2020, 43, 418–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, A.I.; Quartey, J.; Lartey, M. Efficacy of Behavioural Graded Activity Compared with Conventional Exercise Therapy in Chronic Non-Specific Low Back Pain: Implication for Direct Health Care Cost. Ghana medical journal. 2015, 49, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Giménez, P.; Vicente-Mampel, J.; Gargallo, P.; Maroto-Izquierdo, S.; Martín-Ruíz, J.; Jaenada-Carrilero, E.; et al. Effect of exercise and manual therapy or kinesiotaping on sEMG and pain perception in chronic low back pain: a randomized trial. BMC musculoskeletal disorders 2024, 25, 583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, Y.; Currier, L.; Plante, T.W.; Schubert Kabban, C.M.; Tvaryanas, A.P. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Core Strengthening Exercises in Helicopter Crewmembers with Low Back Pain. Aerospace medicine and human performance 2015, 86, 889–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.A.; Anderson, M.L.; Cherkin, D.C.; Balderson, B.H.; Cook, A.J.; Sherman, K.J.; et al. Moderators and Nonspecific Predictors of Treatment Benefits in a Randomized Trial of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction vs Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy vs Usual Care for Chronic Low Back Pain. The journal of pain. 2023, 24, 282–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comachio, J.; Oliveira, C.C.; Silva, I.F.R.; Magalhães, M.O.; Marques, A.P. Effectiveness of Manual and Electrical Acupuncture for Chronic Non-specific Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of acupuncture and meridian studies 2020, 13, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortell-Tormo, J.M.; Sánchez, P.T.; Chulvi-Medrano, I.; Tortosa-Martínez, J.; Manchado-López, C.; Llana-Belloch, S.; et al. Effects of functional resistance training on fitness and quality of life in females with chronic nonspecific low-back pain. Journal of back and musculoskeletal rehabilitation 2018, 31, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Díaz, D.; Martínez-Amat, A.; Osuna-Pérez, M.C.; De la Torre-Cruz, M.J.; Hita-Contreras, F. Short- and long-term effects of a six-week clinical Pilates program in addition to physical therapy on postmenopausal women with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Disability and rehabilitation 2016, 38, 1300–1308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Díaz, D.; Bergamin, M.; Gobbo, S.; Martínez-Amat, A.; Hita-Contreras, F. Comparative effects of 12 weeks of equipment based and mat Pilates in patients with Chronic Low Back Pain on pain, function and transversus abdominis activation. A randomized controlled trial. Complementary therapies in medicine 2017, 33, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Díaz, D.; Romeu, M.; Velasco-González, C.; Martínez-Amat, A.; Hita-Contreras, F. The effectiveness of 12 weeks of Pilates intervention on disability, pain and kinesiophobia in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical rehabilitation 2018, 32, 1249–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Day, M.A.; Ciol, M.A.; Mendoza, M.E.; Borckardt, J.; Ehde, D.M.; Newman, A.K.; et al. The effects of telehealth-delivered mindfulness meditation, cognitive therapy, and behavioral activation for chronic low back pain: a randomized clinical trial. BMC medicine 2024, 22, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 40de Lira, M.R.; Meziat-Filho, N.; Zuelli Martins Silva, G.; Castro, J.; Fernandez, J.; Guirro RRde, J. Efficacy of cognitive functional therapy for pain intensity and disability in patients with non-specific chronic low back pain: a randomised sham-controlled trial. British journal of sports medicine 2025, 59, 912–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elabd, A.M.; Elabd, O.M. Effect of aerobic exercises on patients with chronic mechanical low back pain: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Journal of bodywork and movement therapies 2024, 37, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Zhu, C.; Liu, H.; Bao, T.; Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; et al. Effect of telemedicine-supported structured exercise program in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. PloS one 2025, 20, e0326218. [Google Scholar]

- Ford, J.J.; Hahne, A.J.; Surkitt, L.D.; Chan, A.Y.P.; Richards, M.C.; Slater, S.L.; et al. Individualised physiotherapy as an adjunct to guideline-based advice for low back disorders in primary care: a randomised controlled trial. British journal of sports medicine 2016, 50, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freiwald, J.; Hoppe, M.W.; Beermann, W.; Krajewski, J.; Baumgart, C. Effects of supplemental heat therapy in multimodal treated chronic low back pain patients on strength and flexibility. Clinical biomechanics 2018, 57, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghavipanje, V.; Rahimi, N.M.; Akhlaghi, F. Six Weeks Effects of Dynamic Neuromuscular Stabilization (DNS) Training in Obese Postpartum Women With Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Biological research for nursing 2022, 24, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glombiewski, J.A.; Holzapfel, S.; Riecke, J.; Vlaeyen, J.W.S.; de Jong, J.; Lemmer, G.; et al. Exposure and CBT for chronic back pain: An RCT on differential efficacy and optimal length of treatment. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology 2018, 86, 533–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, E.; Wileman, V.; Galea Holmes, M.; McCracken, L.M.; Norton, S.; Moss-Morris, R.; et al. Physical Therapy Informed by Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (PACT) Versus Usual Care Physical Therapy for Adults With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. The journal of pain. 2020, 21, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grande-Alonso, M.; Suso-Martí, L.; Cuenca-Martínez, F.; Pardo-Montero, J.; Gil-Martínez, A.; La Touche, R. Physiotherapy Based on a Biobehavioral Approach with or Without Orthopedic Manual Physical Therapy in the Treatment of Nonspecific Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Pain medicine 2019, 20, 2571–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwon, A.J.; Kim, S.Y.; Oh, D.W. Effects of integrating Neurac vibration into a side-lying bridge exercise on a sling in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled study. Physiotherapy theory and practice 2020, 36, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halliday, M.H.; Pappas, E.; Hancock, M.J.; Clare, H.A.; Pinto, R.Z.; Robertson, G.; et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing the McKenzie Method to Motor Control Exercises in People With Chronic Low Back Pain and a Directional Preference. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy 2016, 46, 514–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Lucas, P.; Leirós-Rodríguez, R.; Mota, J.; García-Soidán, J.L. Effects of a back school-based intervention on non-specific low back pain in adults: a randomized controlled trial. BMC complementary medicine and therapies 2023, 23, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohmann, C.D.; Stange, R.; Steckhan, N.; Robens, S.; Ostermann, T.; Paetow, A.; et al. The Effectiveness of Leech Therapy in Chronic Low Back Pain. Deutsches Arzteblatt international 2018, 115, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamali, F.; Sinaei, E.; Taherkhani, E. Comparing spinal manipulation with and without Kinesio Taping® in the treatment of chronic low back pain. Journal of bodywork and movement therapies 2018, 22, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.; Ahmad, A.; Mohseni Bandpei, M.A.; Kashif, M. Comparison of the effects of dry needling and spinal manipulative therapy versus spinal manipulative therapy alone on functional disability and endurance in patients with nonspecific chronic low back pain: An experimental study. Medicine 2024, 103, e39734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.K.; Park, H. The Effect of Auricular Acupressure for Chronic Low Back Pain in Elders: A Randomized Controlled Study. Holistic nursing practice 2021, 35, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Lee, J.; Oh, S.; Kim, S.; Yoon, B. Effectiveness of Simulated Horseback Riding for Patients With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of sport rehabilitation 2020, 29, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.T.; Puetz, C.; Tian, L.; Haynes, I.; Lee, E.; Stafford, R.S.; et al. Effect of Electroacupuncture vs Sham Treatment on Change in Pain Severity Among Adults With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA network open. 2020, 3, e2022787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuvačić, G.; Fratini, P.; Padulo, J.; Antonio, D.I.; De Giorgio, A. Effectiveness of yoga and educational intervention on disability, anxiety, depression, and pain in people with CLBP: A randomized controlled trial. Complementary therapies in clinical practice 2018, 31, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, A.E.; Hendrick, P.A.; Clay, L.; Mondal, P.; Trask, C.M.; Bath, B.; et al. A randomized controlled trial investigating effects of an individualized pedometer driven walking program on chronic low back pain. BMC musculoskeletal disorders 2021, 22, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Kim, J. Effects of aquarobics on back pain, sleep, and memory in older women with chronic pain. Medicine 2025, 104, e43199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, X.; E, Y.; Su, Y. The impact of core training combined with breathing exercises on individuals with chronic non-specific low back pain. Frontiers in public health 2025, 13, 1518612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Yang, M.; Liu, T.; Zhong, X.; Tang, W.; Guo, M.; et al. Effect of hand-ear acupuncture on chronic low-back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of traditional Chinese medicine = Chung i tsa chih ying wen pan 2019, 39, 587–598. [Google Scholar]

- Song, J.; Yim, J. Effects of Self-Myofascial Release and Dynamic Neuromuscular Stabilization Exercises on Pain, Balance, Muscle Function, and the Autonomic Nervous System in Women with Chronic Low Back Pain. Medical science monitor : international medical journal of experimental and clinical research 2025, 31, e949985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalfani, A.; Abedi, M.; Raeisi, Z.; Asgarpour, A. The effects of virtual reality training on postural sway and physical function performance on older women with chronic low back pain: A double-blind randomized clinical trial. Journal of back and musculoskeletal rehabilitation 2024, 37, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Shamseer, L.; Clarke, M.; Ghersi, D.; Liberati, A.; Petticrew, M.; et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews 2015, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, N.E.; Anema, J.R.; Cherkin, D.; Chou, R.; Cohen, S.P.; Gross, D.P.; et al. Prevention and treatment of low back pain: evidence, challenges, and promising directions. Lancet 2018, 391, 2368–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traeger, A.C.; Lee, H.; Hübscher, M.; Skinner, I.W.; Moseley, G.L.; Nicholas, M.K.; et al. Effect of Intensive Patient Education vs Placebo Patient Education on Outcomes in Patients With Acute Low Back Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA neurology 2019, 76, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghamkhar, L.; Kahlaee, A.H. Pain and Pain-Related Disability Associated With Proprioceptive Impairment in Chronic Low Back Pain Patients: A Systematic Review. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics 2019, 42, 210–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanton, R.; Ada, L.; Dean, C.M.; Preston, E. Biofeedback improves performance in lower limb activities more than usual therapy in people following stroke: a systematic review. Journal of physiotherapy 2017, 63, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roseen, E.J.; Conyers, F.G.; Atlas, S.J.; Mehta, D.H. Initial Management of Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain: Responses from Brief Interviews of Primary Care Providers. Journal of alternative and complementary medicine 2021, 27, S106–S114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allet, L.; Armand, S.; de Bie, R.A.; Golay, A.; Monnin, D.; Aminian, K.; et al. The gait and balance of patients with diabetes can be improved: a randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia 2010, 53, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- NCBI Bookshelf [Internet]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: Guidelines. 2003. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11822/ (accessed on 18 December 2025).

| S/N | AUTHOR/YEAR | COUNTRY/ SETTING | PARTICIPANTS (AGE RANGE/MEAN, GENDER, SAMPLE SIZE, RETENTION, DISEASE HISTORY/DURATION, SEVERITY) | INTERVENTION (TYPE, COMPONENTS, THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK, PROVIDER, SETTING, DURATION, FOLLOW-UP) | CONTROL/ COMPARATOR | OUTCOMES ASSESSED | OUTCOME MEASURES | TIMEPOINTS ASSESSED | SUMMARY OF RESULTS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aasa et al., 2015 [22] |

Sweden / Outpatient physiotherapy setting | Adults with non-specific low back pain; mean age ~40 years; N = 70 randomised (62 completed); majority chronic (>12 weeks duration); both male and female | Individualized low-load motor control exercise + education: focus on retraining deep trunk stabilizers and postural control; supervised by physiotherapists; 12 weeks, 2 sessions/week; education included ergonomics and self-management | High-load lifting exercise + education: general strengthening with progressive resistance, plus same education content; supervised physiotherapy | Pain intensity, activity limitation, physical performance | Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), Patient-Specific Functional Scale (PSFS), physical performance tests (lifting, endurance tasks) | Baseline, post-intervention (12 weeks), follow-up at 6 months | Both groups improved significantly in pain and activity. No significant between-group differences. Low-load motor control and high-load lifting exercise were equally effective when combined with education. |

| 2 | Afzal et al., 2022 [23] |

Pakistan / Physiotherapy department | Adults with chronic low back pain; N = 68 randomised (34 per group, 62 completed); mean age ~40 years; both genders included; symptom duration >12 weeks | Virtual reality exercise programme + routine physical therapy: interactive VR-based exercises designed to enhance engagement and adherence, combined with conventional physiotherapy; 4 weeks, 3 sessions/week | Routine physical therapy alone: conventional exercises and physiotherapy management without VR component | Pain intensity, functional disability | Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) | Baseline, post-intervention (4 weeks) | VR + physiotherapy group showed greater reductions in pain intensity and disability compared to physiotherapy alone. Intervention was feasible and well-tolerated. |

| 3 | Ahmadi et al., 2020 [24] |

Iran / Outpatient, Sports Medicine Clinic, Mazandaran Medical University | 60 patients with chronic non-specific low back pain; equally randomised into two groups; mean age ~40 years; both genders included; symptom duration >12 weeks | Feldenkrais Method: supervised exercise therapy + theoretical training content, 2 sessions/week for 5 weeks | Core stability exercise + education: educational programme and home-based core stability training for 5 weeks | Pain intensity, disability, quality of life, interoceptive awareness | WHO Quality of Life Questionnaire, McGill Pain Questionnaire, Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness | Baseline, post-intervention (5 weeks) | Both groups improved in pain, but Feldenkrais group showed greater improvements in quality of life (p = 0.006), interoceptive awareness (p < 0.001), and disability (p = 0.021). No significant between-group difference in McGill pain scores. |

| 4 | Ahmadnezhad et al., 2020 [25] |

Iran / Clinical rehabilitation laboratory | 47 athletes with CLBP (23 male, 24 female) with chronic low back pain; randomly divided into intervention and control groups; mean age not reported | Inspiratory Muscle Training (IMT): performed using POWERbreathe KH1; 8 weeks, 7 days/week, 2 sessions/day; initial load at 50% of maximum inspiratory pressure with progressive increases | Control group: no IMT; continued with standard rehabilitation management | Pain intensity, core muscle activity, pulmonary function | Surface EMG (erector spinae, multifidus, transverse abdominis, rectus abdominis), spirometry for respiratory parameters, Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) | Baseline, post-intervention (8 weeks) | IMT group showed significant increases in multifidus and transverse abdominis activity, improved pulmonary function, and a reduction in pain intensity (p < 0.05). Control group did not show comparable changes. |

| 5 | Akbaş et al., 2025 [26] |

Turkey / Rheumatology outpatient clinic | 50 adults with chronic low back pain; randomised into 3 groups (Group 1 = 16, Group 2 = 17, Control = 17); mean age not specified; all completed | Stabilization exercises (SSE): Group 1 = supervised 4 days/week; Group 2 = supervised 2 days/week; duration = 12 weeks; delivered by physiotherapists | Home exercise programme only | Core muscle stiffness, pain intensity, disability | Shear wave elastography (TrA stiffness), Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) | Baseline, 6 weeks, 12 weeks | Group 1 (SSE 4x/week) showed significantly greater improvements in core muscle stiffness and disability compared to Group 2 and control (p < 0.05). Both SSE groups reduced pain vs. control, but no significant difference between Group 1 and 2 for pain. |

| 6 | Back et al., 2024 [27] |

Brazil / Primary care physiotherapy clinic | 81 patients with chronic non-specific low back pain; aged 18–80 years; pain ≥3 months; baseline pain ≥3 on VAS; randomised into 3 groups (concave tip, convex tip, placebo) | Extracorporeal shockwave therapy (ESWT): single session, radial type; 2000 discharges, 100 mJ energy, 5 Hz frequency; applied with concave or convex applicator tips | Placebo treatment: sham application (no therapeutic dose delivered) | Pain intensity, pressure pain threshold, temporal summation of pain, functional performance | Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), algometry for pressure pain threshold, temporal summation protocols, functional tests | Baseline, immediate post-intervention | Concave tip ESWT produced a 2-point greater reduction in pain compared to placebo (p < 0.01), and significantly higher pressure pain thresholds compared to convex tip and placebo groups (p < 0.05). Convex tip produced smaller, non-significant effects. |

| 7 | Bagg et al., 2022 [28] |

Australia / Medical research institute, Sydney | 276 adults with chronic non-specific low back pain (>3 months); mean age 46 (SD 14.3); 50% women; recruited from primary care and community; 261 (95%) completed | Graded sensorimotor retraining (RESOLVE): 12 weekly clinical sessions + home training; included movement retraining, education, and graded physical activity; supervised by trained clinicians | Sham and attention control: 12 weekly sessions including sham laser, sham diathermy, sham brain stimulation, and non-specific home training without focus on movement or activity | Pain intensity (primary), function, disability | Numerical Rating Scale (0–10), disability questionnaires (not detailed in abstract) | Baseline, 18 weeks (primary endpoint) | Intervention group improved more than control: mean pain reduced from 5.6 → 3.1 vs. 5.8 → 4.0; between-group mean difference = –1.0 (95% CI: –1.5 to –0.4, p = .001). Effect statistically significant but small. |

| 8 | Bagheri et al., 2020 [29] |

Iran / Outpatient physiotherapy clinic | 40 adults with non-specific chronic low back pain; randomised into 2 groups (n = 20 per group); mean age not specified; both genders included | CBT + Stabilization Exercises (SE): supervised SE combined with cognitive behavioural therapy sessions addressing fear-avoidance, coping strategies; duration not specified in abstract | Stabilization Exercises alone: no CBT component | TrA muscle thickness, fear-avoidance beliefs, disability | Ultrasound imaging of TrA contraction (during ADIM & ASLR), Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ), Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) | Baseline, post-intervention (timeframe not stated, estimated short-term) | Experimental group (CBT + SE) showed greater TrA thickness increases during ADIM (p = .001), and significant improvements in FABQ (p = .04) and disability (RMDQ, p = .01) compared to SE alone. No group differences for TrA thickness during ASLR. |

| 9 | Bello et al., 2015 [30] |

Ghana / Outpatient physiotherapy clinic | 80 adults with chronic non-specific low back pain; mean age ~44 years; 62 participants (77.5%) completed (CET = 29, BGA = 33) | Behavioural Graded Activity (BGA): time-contingent, sub-maximal activities individually prescribed; 2 sessions/week for 12 weeks; supervised physiotherapy | Conventional Exercise Therapy (CET): supervised structured exercise sessions; 2 sessions/week for 12 weeks | Pain intensity, quality of life, healthcare cost | Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), RAND-36 health survey, physiotherapy cost questionnaire | Baseline, 4 weeks, 12 weeks | Both groups showed significant improvements in pain and quality of life (p < 0.001). No significant differences between groups. Cost analysis indicated that both CET and BGA could have implications for healthcare resource allocation. |

| 10 | Blanco-Giménez et al., 2024 [31] |

Spain / Outpatient physiotherapy clinics | Adults with chronic low back pain (mild disability by ODI); N=80 (3 parallel groups, intention-to-treat); mean age not specified | Exercise + adjunct therapy: 12-week supervised lumbo-pelvic core stability and motor-control program, supplemented by (a) manual therapy (MT) or (b) kinesiotaping (KT); delivered by physiotherapists | Exercise + adjunct comparison: exercise program combined with either MT or KT (both active comparators, no pure placebo/sham arm) | Pain perception, trunk muscle activation | Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), surface EMG of rectus abdominis (RA) and multifidus (MF) | Baseline, post-intervention (12 weeks) | Both MT + exercise and KT + exercise led to significant reductions in perceived pain. EMG analysis showed improved RA activation in exercise groups, but changes in MF were less consistent. No clear superiority between MT and KT adjuncts; benefits appeared to derive mainly from the exercise component. |

| 11 | Brandt et al., 2015 [32] |

USA / U.S. Air Force helicopter aircrew | 12 helicopter crewmembers with low back pain; 5 randomized to intervention, 7 to control; mean age not reported; military subgroup | Core strengthening exercises: 5 specific exercises performed 4 days/week for 12 weeks; supervised program | Control group: maintained regular exercise regimen | Pain intensity (daily and in-flight), disability, global improvement | Numerical Pain Rating Scale (NPRS daily & in-flight), Modified Oswestry Disability Index (MODI), Global Rating of Change Scale (GRCS) | Baseline, 12 weeks | Intervention group reported reduced in-flight pain (–1.8 points), decreased disability (–4.8 MODI points), and higher global improvement compared to control. No significant between-group difference in daily NPRS pain. |

| 12 | Chen et al., 2023 [33] |

USA / Outpatient, multicenter | 297 adults aged 20–70 with chronic low back pain; recruited from community; randomized into 3 groups: MBSR (n≈100), CBT (n≈100), usual care (n≈100) | Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR): 8-week program including meditation, mindful movement, and group sessions. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): 8-week program targeting pain coping, catastrophizing, and behavior modification. | Usual Care (UC): standard medical management with no structured MBSR or CBT | Function, pain bothersomeness, depression, moderators of treatment response | Modified Roland Disability Questionnaire (function), 0–10 Numerical Rating Scale (pain bothersomeness), PHQ-8 (depression), mindfulness questionnaires | Baseline, 8 weeks, follow-up (duration not specified in abstract, likely 26+ weeks per trial registry) | Both MBSR and CBT significantly improved function and reduced pain compared to usual care. Moderators: mindfulness “nonjudging” trait predicted differential benefit (better outcomes with MBSR). Pain control beliefs and lower anxiety predicted improvement across all groups. |

| 13 | Comachio et al., 2020 [34] |

Brazil / Outpatient physiotherapy-acupuncture clinic | 66 adults aged 20–60 years with chronic non-specific low back pain (>3 months, pain ≥3/10); randomized equally to MA or EA groups | Manual Acupuncture (MA): 12 sessions at local, distal, and sensitized acupoints. Electroacupuncture (EA): 12 sessions with electrical stimulation through acupuncture needles. | Comparison between MA and EA (no sham/placebo group). | Pain intensity, disability, kinesiophobia | Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia | Baseline, post-intervention (12 sessions), 3-month follow-up | Both MA and EA groups showed significant improvements in pain and disability, sustained at 3 months. No significant between-group differences, except reduced kinesiophobia in the MA group (–4.1 points, 95% CI = –7.0 to –1.1). |

| 14 | Cortell-Tormo et al., 2018 [35] |

Spain / University-based rehabilitation program | 19 adult females with chronic non-specific low back pain, recruited via Paris Task Force criteria; randomized to exercise (n=10) or control (n=9) | Functional resistance training: 12-week periodized program, 24 sessions (2x/week), focusing on functional movements, trunk stability, and progressive loading | Control group: no structured exercise intervention | Pain, disability, health-related quality of life, physical fitness | Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), SF-36, physical fitness tests (flamingo, back endurance, side bridge, curl-up, squat) | Baseline, post-intervention (12 weeks) | Exercise group showed significant improvements in pain (–62.5%), disability (–61.3%), HRQOL (physical function, vitality, physical component scale), and physical fitness tests (balance, endurance, squat, core strength) compared to control (p < 0.05 to < 0.01). |

| 15 | Cruz-Díaz et al., 2017 [36] |

Spain / Physiotherapy rehabilitation program | 98 adults with chronic non-specific low back pain; randomized into 3 groups: Mat Pilates (PMG), Equipment-based Pilates (PAG), or Control group (CG); mean age not specified | Mat Pilates (PMG): 12-week program of mat-based Pilates exercises. Equipment Pilates (PAG): 12-week program using Pilates apparatus providing feedback and resistance. Both: supervised, 2–3x/week | Control group: no structured Pilates intervention | Pain, disability, kinesiophobia, TrA activation | Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK), real-time ultrasound (TrA activation) | Baseline, 6 weeks, 12 weeks | Both Pilates groups improved significantly in pain, disability, TrA activation, and kinesiophobia (p < 0.001). Equipment-based Pilates showed faster improvements than mat Pilates (p = 0.007), suggesting apparatus feedback enhanced engagement with Pilates principles. |

| 16 | Cruz-Díaz et al., 2016 [37] |

Spain / Physiotherapy rehabilitation clinics | 101 postmenopausal women with chronic low back pain; randomized into Pilates + PT group (PPT) vs PT-only group; retention not fully reported | Clinical Pilates + Physical Therapy (PPT): 6-week program combining Pilates-based supervised exercise with standard PT | Physical Therapy (PT) alone: conventional physiotherapy without Pilates | Pain, disability | Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) | Baseline, 6 weeks, 1-year follow-up | After 6 weeks, PPT group showed significant reductions in pain and disability compared to PT alone (effect sizes: pain d = 3.14, disability d = 2.33). At 1-year follow-up, improvements persisted in the PPT group (d = 2.49 for pain, d = 4.98 for disability), whereas PT-only group returned to baseline levels. |

| 17 | Cruz-Díaz et al., 2018 [38] |

Spain / University laboratory | 64 adults with chronic non-specific low back pain; randomized to Pilates group (n = 32) or control (n = 32); mean age not specified | Pilates intervention: supervised exercise program, 12 weeks, focusing on lumbo-pelvic stability, posture, and core control | Control group: no treatment | Disability, pain, kinesiophobia | Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK) | Baseline, 6 weeks, 12 weeks | Pilates group showed significant improvements in disability, pain, and kinesiophobia compared to control (p < 0.001). Largest changes in disability and kinesiophobia were seen at 6 weeks, with continued pain improvement at 12 weeks. Mean between-group differences: RMDQ = 4.0, TSK = 5.5, VAS = 2.4. |

| 18 | Day et al., 2024 [39] |

USA / Telehealth (videoconference delivery) | 302 adults with chronic low back pain; randomized to Cognitive Therapy (CT), Mindfulness Meditation (MM), or Behavioral Activation (BA); balanced gender; retention high (exact % not in abstract) | CT, BA, or MM: all delivered in groups via videoconference; focused on pain coping, mindfulness skills, or activity engagement; program duration not detailed in abstract; follow-up to 6 months | No inert/sham control; comparison between 3 active treatment arms | Pain interference (primary), secondary outcomes (pain intensity, function, sleep disturbance, mental health) | Standardized scales (pain interference scores, sleep disturbance questionnaires, functional and mental health measures) | Pre- to post-treatment, 3 months, 6 months | All three interventions (CT, BA, MM) produced medium-to-large reductions in pain interference (ds –0.71 to –1.00), maintained at 3 and 6 months. Secondary outcomes improved with small-to-medium effects. No significant differences between groups, except BA showed greater improvement in sleep disturbance vs MM (d = –0.49). |

| 19 | de Lira et al., 2025 [40] |

Brazil / Primary care public health service | 152 adults with non-specific chronic low back pain; randomized to CFT (n=76) or sham (n=76); >97% follow-up retention | Cognitive Functional Therapy (CFT): 6 individualized one-hour sessions; tailored approach combining pain reconceptualization, lifestyle advice, movement retraining, and self-management strategies | Sham control: 6 sessions of neutral talking + detuned photobiomodulation (placebo laser); both groups also received a CLBP education booklet | Pain intensity, disability | Numerical Rating Scale (pain), disability index (tool not specified in abstract, likely ODI or RMDQ) | Baseline, 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months | CFT group showed greater reductions in pain (MD = –1.8; 95% CI –2.5 to –1.1) and disability (MD = –9.9; 95% CI –13.2 to –6.5) compared with sham at 6 weeks. Improvements were sustained at 3- and 6-month follow-up. |

| 20 | Elabd & Elabd, 2024 [41] |

Egypt / University hospital physiotherapy clinic | 50 young adults with chronic mechanical low back pain; 22 males, 28 females; randomized equally into 2 groups; 8-week program | Experimental group: conventional physiotherapy (infrared, ultrasound, burst TENS, exercise) + aerobic training (stationary bicycle) | Control group: conventional physiotherapy only (infrared, ultrasound, burst TENS, exercise) | Pain intensity, disability, endurance, physical performance | Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), Sorensen test (back extensor endurance), Back Performance Scale, 6-Minute Walk Test (6MWT) | Baseline, post-intervention (8 weeks) | Both groups improved significantly in pain and function (p < 0.001). Experimental group showed greater improvements in disability (p = 0.043), extensor endurance (p = 0.023), and 6MWT performance (p = 0.023). No significant group-by-time differences for pain intensity or Back Performance Scale. |

| 21 | Feng et al., 2025 [42] |

China / Telemedicine (mobile health apps) | 78 adults with chronic low back pain; randomized 1:1 into experimental (n=39) and control (n=39); mean age not reported | Telemedicine-supported structured exercise program: 8 weeks, delivered via mHealth apps; included patient education, health coaching, and structured exercise | Usual care therapy: education + paper handouts describing home exercises | Disability, pain intensity, mental health, quality of life, walking ability, adherence | Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), DASS-21, SF-12, Timed Up and Go (TUG), Exercise Adherence Rating Scale (EARS) | Baseline, 4 weeks (mid-treatment), 8 weeks (post-treatment) | Telemedicine group had greater improvements in disability (MD = –3.96), pain (MD = –1.69), and physical QoL (MD = +4.5) compared to control (p < 0.01). Within-group improvements were also observed for mental health, walking ability, and QoL mental component, though between-group differences were not significant. |

| 22 | Ford et al., 2016 [43] |

Australia / 16 primary care physiotherapy practices (multicentre) | 300 adults with low back disorders persisting ≥6 weeks to ≤6 months; randomized to individualised PT (n=156) vs advice (n=144) | Individualised physiotherapy + guideline-based advice: 10 sessions; tailored treatment addressing pathoanatomical, psychosocial, and neurophysiological barriers to recovery | Guideline-based advice alone: 2 physiotherapist-delivered sessions | Disability, back pain, leg pain | Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) for back and leg pain | 5, 10, 26, and 52 weeks | Individualised physiotherapy significantly improved ODI at 10 weeks (4.7 points), 26 weeks (5.4), and 52 weeks (4.3) compared to advice. Back and leg pain also improved more in the intervention at 10 and 26 weeks. At 12 months, intervention group more likely to achieve ≥50% improvement in ODI (RR 1.5) and pain (RR 1.3). |

| 23 | Freiwald et al., 2018 [44] |

Germany / Multimodal rehabilitation program | 176 adults with chronic low back pain; enrolled in individualized multimodal treatment program; randomized to multimodal treatment with or without heat wraps | Multimodal therapy + supplemental heat therapy (thermotherapy): daily application of heat wrap for several hours in addition to standard multimodal treatment | Multimodal therapy alone (exercise, education, and other guideline-based components) | Trunk strength, flexibility, range of motion | Biomechanical testing of trunk flexion, extension, lateral flexion, and rotation | Baseline, post-intervention (12 weeks) | Both groups improved significantly in strength and range of motion. Heat therapy group showed additional improvements in trunk strength (extension and rotation), though differences were modest and not statistically strong (p ~ 0.08–0.09). No significant differences in flexibility. |

| 24 | Ghavipanje et al., 2022 [45] |

Iran / Clinical rehabilitation setting | 40 obese postpartum women with low back pain; mean age 29.3 ± 3.8 years; BMI ~32; randomized equally to DNS (n=20) or General Exercise (n=20); all completed 6 weeks | Dynamic Neuromuscular Stabilization (DNS): 6 sessions/week for 6 weeks; exercises based on developmental kinesiology patterns to restore posture, breathing, and core control | General Exercise (GE): 6 sessions/week for 6 weeks; conventional exercises not based on DNS principles | Pain, disability, fear-avoidance, respiratory function | Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS), Modified Oswestry Disability Questionnaire (MODQ), Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ), Breath Hold Time (BHT), Respiratory Rate (RR), Global Rating of Change (GROC) | Baseline, post-intervention (6 weeks) | Both groups improved, but DNS group showed significantly greater improvements across all measures, including pain, disability, FABQ, respiratory control, and GROC scores (p < .05). |

| 25 | Glombiewski et al., 2018 [46] |

Germany / Outpatient psychological setting | 88 participants with chronic low back pain (≥3 months) and high fear-avoidance; 55% women; randomized to three groups | Exposure therapy: tailored, fear-focused; delivered in short (10 sessions) or long versions; focused on reducing pain-related anxiety & fear-avoidance | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): active comparator focusing on coping strategies and cognitive restructuring | Disability, pain intensity, pain-related anxiety, psychological flexibility, coping, depression | Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale (QBPDS), Pain Disability Index (PDI), average pain NRS, FABQ, coping and depression scales | Pre-treatment, mid-treatment, post-treatment, 6-month follow-up | Exposure > CBT for reducing movement-related disability (QBPDS) and improving psychological flexibility. No difference in pain intensity or disability (PDI). CBT outperformed Exposure in coping strategies. Shorter Exposure was more effective than longer version for speed of improvement. More dropouts in Exposure groups. |

| 26 | Godfrey et al., 2020 [47] |

UK / Four public hospital physiotherapy clinics | 248 adults with chronic low back pain (≥12 weeks, mean duration ~3 years); mean age 48; 59% female | PACT (Physical Therapy informed by ACT): standard physiotherapy integrated with Acceptance and Commitment Therapy strategies; delivered by trained physiotherapists; fidelity ≥80% | Usual care physiotherapy without ACT elements | Disability (primary), physical function, health-related quality of life, treatment credibility | Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), Patient Specific Functioning, SF-12, Treatment Credibility Scale | Baseline, 3 months, 12 months | PACT group improved more at 3 months for disability (mean diff RMDQ = -1.07, p = .037), functioning (p = .008), SF-12 physical health (p = .032), and credibility (p < .001). No between-group differences at 12 months. PACT was feasible, acceptable, and delivered with high fidelity. |

| 27 | Grande-Alonso et al., 2019 [48] |

Spain / Outpatient physiotherapy setting | 50 adults with nonspecific chronic low back pain; randomized equally; mean age not reported; mixed gender | Biobehavioral therapy + Orthopedic Manual Therapy (OMT): 8 sessions, 2/week; combined education, exercise, behavioral strategies with OMT techniques | Biobehavioral therapy alone: identical dose/frequency without OMT | Pain intensity, pain frequency, somatosensory, physical and psychological variables | Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NPRS), psychological/functional assessments | Baseline, 1 month, 3 months | Both groups improved significantly across all variables (pain, function, psychological outcomes) with large effect sizes (>0.80). No significant differences between groups, suggesting that OMT did not add extra benefit beyond the biobehavioral approach. |

| 28 | Gwon et al., 2020 [49] |

South Korea / Physiotherapy clinical setting | 30 adults with chronic low back pain; randomized into experimental group (n=15) and control group (n=15) | Experimental group (EG): Side-lying bridge exercise on a sling system + Neurac vibration | Control group (CG): Same side-lying bridge exercise on sling without vibration | Pain, asymmetry of weight distribution, asymmetry of hip abductor strength (AHAS), static balance (one-leg stance) | Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for pain; weight distribution & hip abductor strength asymmetry indices; static balance measures | Baseline, post-intervention | EG showed significant improvements in all outcomes (pain, AHAS, weight distribution, balance, p < 0.05). CG improved only in pain and AHAS. Pain reduction had the largest effect size (d=0.77, moderate effect). Neurac vibration enhanced exercise effectiveness. |

| 29 | Halliday et al., 2019 [50] |

Australia / Secondary public health facility, Sydney | 70 adults with chronic low back pain (>3 months) and directional preference; randomized equally | McKenzie Method (MDT): 12 supervised sessions over 8 weeks, focusing on repeated movement testing and patient self-management strategies | Motor Control Exercises (MCE): 12 supervised sessions over 8 weeks, focusing on deep trunk muscle activation and control | Primary: Trunk muscle thickness (TrA, obliquus internus, obliquus externus). Secondary: Pain, function, perceived recovery | Ultrasound imaging for muscle thickness; pain scales; functional questionnaires | Baseline, 8 weeks (post-intervention), 1 year (follow-up) | No significant differences between groups at 1-year for muscle thickness, pain, function, or recovery. Both interventions demonstrated similar long-term effects, indicating that MDT and MCE are equally effective for this subgroup of CLBP patients with directional preference. |

| 30 | Hernandez-Lucas et al., 2023 [51] |

Spain / Clinical and community setting | 40 adults with non-specific low back pain; randomized into experimental and control groups | Back School program (8 weeks): 14 practical sessions (strengthening + flexibility exercises) + 2 theoretical sessions (anatomy, lifestyle education) | Control group: maintained usual lifestyle (no structured program) | Pain, disability, quality of life, kinesiophobia | Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), Short Form-36 (SF-36), Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK) | Baseline, post-intervention (8 weeks) | Experimental group showed significant improvements in pain, disability, physical QoL (SF-36), and kinesiophobia (p < 0.05). No significant changes in psychosocial QoL. Control group showed no significant improvements. |

| 31 | Hohmann et al., 2018 [52] |

Germany / Outpatient clinical setting | 44 adults with chronic low back pain (≥3 months); randomized to leech therapy (n=25) or exercise therapy (n=19) | Leech therapy: single local application of 4–7 leeches | Exercise therapy: 4 weekly sessions (1 hour each) led by physiotherapist | Pain intensity (primary); physical impairment, function, QoL, pain perception, depression, analgesic use (secondary) | Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), Hannover Functional Ability Questionnaire, SF-36, SES, CES-D, analgesic diary | Baseline, 28 days, 56 days | Leech therapy group showed significantly greater pain reduction (VAS: -25.2 points vs control, p = 0.0018), and better functional and QoL outcomes at 4 and 8 weeks. No significant effect of patient expectations. Limitations: small sample, unblinded design, short follow-up. |

| 32 | Kamali et al., 2018 [53] |

Iran / Sports rehabilitation setting | 42 athletes (21 male, 21 female) with chronic non-specific LBP; randomized equally | Spinal Manipulation (SM) + Kinesio Taping (KT): applied during treatment | Spinal Manipulation (SM) only: identical frequency without KT | Pain, functional disability, trunk flexor–extensor endurance | Numerical Rating Scale (NRS), Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), McQuade test, Unsupported trunk holding test | Baseline, immediately post, 1 day, 1 week, 1 month | Both groups showed significant improvements in pain, disability, and endurance over time (p < 0.05). No significant between-group differences at any time point. Adding KT to SM did not confer extra benefit. |

| 33 | Khan et al., 2024 [54] |

Pakistan / Outpatient physiotherapy setting | Adults with chronic nonspecific low back pain (n not specified; both genders) N=114; randomized to SMT+DN or SMT alone |

Experimental group: Spinal Manipulative Therapy (SMT) + Dry Needling (DN); delivered over 8 weeks | Control group: SMT alone, identical duration/frequency | Functional disability, endurance | Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), endurance tests | Baseline, 8 weeks | Both groups improved significantly in disability and endurance. SMT+DN group showed greater reductions in RMDQ scores (mean diff baseline–8 weeks: -2.75, p = .003) and larger endurance gains compared to SMT alone. |

| 34 | Kim & Park, 2021 [55] |

South Korea / Community setting | 51 elderly participants with chronic low back pain; randomized to experimental (n=26) and placebo (n=25) | Auricular acupressure (AA): applied to LBP-related ear points; 6 weeks, weekly cycles | Placebo AA: applied to unrelated ear points, identical schedule | Pain intensity, pain threshold, disability | Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), Pain threshold test, Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) | Baseline, post-intervention (6 weeks) | Experimental group showed significant improvements in pain (VAS, p < .001), pain threshold (p < .001), and disability (ODI, p < .001) compared to placebo. Suggests AA is a safe, effective, noninvasive alternative for CLBP in elders. |

| 35 | Kim et al., 2020 [56] |

South Korea / Community & university campus | 48 adults with chronic low back pain; randomized equally to SHR (n=24) and stabilization (STB) (n=24) | Simulated Horseback Riding (SHR): seated exercise mimicking horseback riding motion; 30 min, 2x/week for 8 weeks | Stabilization (STB): conventional trunk stabilization exercises; identical schedule | Pain, disability, fear-avoidance | Numeric Rating Scale (NRS), Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) | Baseline, 4 weeks, 8 weeks, 6 months | Both SHR and STB improved pain and disability significantly within groups. Between groups: SHR reduced FABQ-work more effectively (p = .01), while other outcomes (NRS, ODI, RMDQ, FABQ-physical) showed no significant differences. SHR uniquely sustained long-term fear-avoidance improvements at 6 months. |

| 36 | Kong et al., 2020 [57] |

USA / Stanford University, single-center | 121 adults with chronic low back pain (≥6 months, pain ≥4/10, no radiculopathy); randomized: real EA (n=59), sham EA (n=62) | Real Electroacupuncture (EA): 12 sessions, 2x/week for 6 weeks | Sham EA: identical procedure but with placebo stimulation | Pain intensity (primary), disability (secondary), psychosocial/demographic moderators | PROMIS Pain Intensity T-scores, Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), psychophysical testing (e.g., temporal summation, CPM), coping, self-efficacy, catastrophizing | Baseline, 2 weeks post-treatment | No significant difference in primary outcome (PROMIS pain intensity) between groups (p=0.06). Significant improvement in disability (RMDQ) for EA vs sham (mean diff = -2.11, p=0.01). Coping skills predicted better outcomes; White participants had poorer responses than non-White. |

| 37 | Kuvačić et al., 2018 [58] |

Croatia / Clinical setting | 30 adults with chronic low back pain (mean age 34.2 ± 4.5 yrs); randomized equally to yoga group (n=15) and pamphlet group (n=15) | Yoga + education: 8-week program, 2x/week; included yoga postures plus education on spine anatomy/biomechanics and CLBP management | Pamphlet group: received informational pamphlet only (usual advice) | Disability, depression, anxiety, pain | Oswestry Disability Index (ODI-I), Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS), Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) | Baseline, post-intervention (8 weeks) | Yoga + education group showed significant improvements in depression, anxiety, and pain (p < 0.05) compared to pamphlet. Both groups improved in disability, but no significant between-group difference in ODI. |

| 38 | Lang et al., 2021 [59] |

Australia / Community setting | 174 adults with chronic low back pain; randomized 2:1 to walking group (WG) and standardized care (SG); 138 (79%) completed at 12 weeks; 96 (55%) at 12 months | Walking group (WG): 12-week pedometer-driven, physiotherapist-guided program; individualized weekly step targets negotiated with participants | Standardized care group (SG): education + advice package (self-management, stay active, benefits of PA) | Disability (primary), pain, physical activity, beliefs, QoL, self-efficacy | Oswestry Disability Index (ODI), Numeric Pain Rating Scale (NRS), IPAQ, FABQ, Back Beliefs Questionnaire (BBQ), PA Self-efficacy, EQ-5D-5L | Baseline, 12 weeks, 6 months, 12 months | No significant group differences for ODI or secondary outcomes at any time point. Subgroup analyses: participants with moderate disability (ODI ≥21) and those with low baseline step counts (<7500/day) showed greater ODI improvements in the walking group. Suggests walking may benefit subgroups rather than all CLBP patients. |

| 39 | Lee & Kim, 2025 [60] |

South Korea / Community setting | 152 older women aged ≥65 years with CLBP >1 year (Experimental: n=68; Control: n=84). Mean age 70.1 ± 1.5 (exp) vs 71.1 ± 1.0 (ctrl); mean CLBP duration 8.7 years | Aquarobics group: 60-min aquatic aerobics sessions, twice per week, for 12 weeks | Control group: sedentary lifestyle, no structured exercise | Pain/disability, sleep disturbance, subjective memory impairment | Back Pain Disability Index, standardized sleep disturbance scale, subjective memory impairment questionnaire; SEM for mediating effects | Baseline and post-12 weeks | Significant improvements in the aquarobics group vs control: pain disability ↓ (MD = -7.6, 95% CI: -10.5 to -4.9, p<.001), sleep disturbance ↓ (MD = -4.2, 95% CI: -6.8 to -1.5, p<.001), memory impairment ↓ (MD = -3.9, 95% CI: -6.1 to -1.7, p<.001). SEM showed pain reduction mediated improvements in sleep and memory outcomes. Concluded aquarobic exercise is effective for both physical and cognitive enhancement in older women with CLBP. |

| 40 | Li, Y., et al., 2025 [61] |

China / University rehabilitation setting | 18 patients with chronic non-specific LBP | Core training + breathing exercises for 12 weeks | Core training only; Control (no exercise) | Pain, disability, muscle strength | VAS (pain), ODI (disability), muscle strength test | Baseline and post 12-week intervention | Combined core + breathing group showed significantly greater reduction in pain, improved functional outcomes, and enhanced muscle strength compared to core-only and control. |

| 41 | Luo, Y., et al., 2019 [62] |

China / General Hospital of Western Theater Command | 152 adults with chronic LBP | Hand-ear acupuncture (18 sessions over 7 weeks) | Standard acupuncture; Usual care | Pain, disability, overall efficacy | Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ), TCM Symptom Curative Effect Standard | Baseline, 2 months, 6 months | Hand-ear acupuncture showed significant improvement in VAS and RMDQ compared to standard acupuncture and usual care. At 6 months, RMDQ improved by 7.74 points in the hand-ear acupuncture group. Overall efficacy was 88.9% vs 45.8% in usual care. |

| 42 | Song & Yim, 2025 [63] |

South Korea / Exercise center, Seongnam City | 40 women with CLBP | Self-myofascial release (SMR) + DNS (20 min SMR + 30 min DNS, 2x/week, 6 weeks) | DNS alone (30 min, 2x/week, 6 weeks) | Pain, static & dynamic balance, muscle endurance, flexibility, muscle tone/stiffness, disability, autonomic regulation | VAS, Functional Reach Test (FRT), Y-Balance Test, Supine Bridge, Sit-and-Reach, Myoton PRO, ODI (Korean version), SDNN (HRV) | Baseline, post-intervention (6 weeks) | Both groups improved in all outcomes (p<0.05). Experimental group achieved significantly greater improvements in pain, balance, flexibility, endurance, muscle tone, ODI, and SDNN. Integration of SMR with DNS yielded superior clinical and autonomic benefits. |

| 43 | Yalfani et al., 2022 [64] |

Iran / Elderly care & rehabilitation setting | 25 elderly women (65–75 yrs) with CLBP | Virtual Reality Training (VRT) using Xbox Kinect, 30 min, 3x/week for 8 weeks | Control group (no VR training, usual lifestyle) | Pain intensity, fall risk, quality of life | VAS, Biodex Balance System, SF-36 | Baseline, post-intervention (8 weeks) | VRT group showed significant improvements: ↓ pain intensity (p=0.001), ↓ fall risk (p=0.001), ↑ QoL (p=0.001). Virtual reality provided enhanced exercise engagement and therapeutic benefit. |

| STUDY | SOURCES/POTENTIAL SOURCES OF BIASA | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Eligibil ity Criteri a | Rando m Allocati on | Concealed Allocation | Baseline Similari ty | Bindin g Of Sub- Jects |

Blinding Of thera- pists | Blinding Of Accessor s | Measures Of key Outcomes From 85% of the initially allocated | Intenti on To treat/1 00% partici pation |

Betwee n Group | Point measure & variabiles | Grade Quality ROB | Level of Evidence |

| Aasa et al., 2015 [22] |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

8 High Quality Low RoB |

Level I |

| Afzal et al., 2022 [23] |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

6 High Quality Low RoB |

Level I |

| Ahmadi et al., 2020 [24] |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

8 High Quality Low RoB |

Level I |

| Ahmadnezhad et al., 2020 [25] |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

6 High Quality Low RoB |

Level II |

| Akbaş et al., 2025 [26] |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

7 High Quality Low RoB |

Level I |

| Back et al., 2024 [27] |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

10 High Quality Low RoB |

Level I |

| Bagg et al., 2022 [28] |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

9 High Quality Low RoB |

Level I |

| Bagheri et al., 2020 [29] |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

6 High Quality Low RoB |

Level II |

| Bello et al., 2015 [30] |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

5 Moderate Quality Some Concern RoB |

Level II |

| Blanco-Giménez et al., 2024 [31] |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

8 High Quality Low RoB |

Level I |

| Brandt et al., 2015 [32] |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

5 Moderate Quality Some Concern RoB |

Level II |

| Chen et al., 2023 [33] |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

8 High Quality Low RoB |

Level I |

| Comachio et al., 2020 [34] |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

8 High Quality Low RoB |

Level I |

| Cortell-Tormo et al., 2018 [35] |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

6 High Quality Low RoB |

Level II |

| Cruz-Díaz et al., 2017 [36] |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

5 Moderate Quality Some Concern RoB |

Level II |

| Cruz-Díaz et al., 2016 [37] |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

5 Moderate Quality Some Concern RoB |

Level II |

| Cruz-Díaz et al., 2018 [38] |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

7 High Quality Low RoB |

Level I |

| Day et al., 2024 [39] |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

7 High Quality Low RoB |

Level I |

| de Lira et al., 2025 [40] |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

9 High Quality Low RoB |

Level I |

| Elabd & Elabd, 2024 [41] |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

6 High Quality Low RoB |

Level I |

| Feng et al., 2025 [42] |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

7 High Quality Low RoB |

Level I |

| Ford et al., 2016 [43] |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

7 High Quality Low RoB |

Level I |

| Freiwald et al., 2018 [44] |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

6 High Quality Low RoB |

Level I |

| Ghavipanje et al., 2022 [45] |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

5 Moderate Quality Some Concern RoB |

Level II |

| Glombiewski et al., 2018 [46] |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

5 Moderate Quality Some Concern RoB |

Level II |

| Godfrey et al., 2020 [47] |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

8 High Quality Low RoB |

Level I |

| Grande-Alonso et al., 2019 [48] |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

6 High Quality Low RoB |

Level I |

| Gwon et al., 2020 [49] |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

7 High Quality Low RoB |

Level II |

| Halliday et al., 2019 [50] |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

7 High Quality Low RoB |

Level I |

| Hernandez-Lucas et al., 2023 [51] |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

7 High Quality Low RoB |

Level II |

| Hohmann et al., 2018 [52] |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

9 High Quality Low RoB |

Level II |

| Kamali et al., 2018 [53] |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

5 Moderate Quality Some Concern RoB |

Level II |

| Khan et al., 2024 [54] |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

6 High Quality Low RoB |

Level I |

| Kim & Park, 2021 [55] |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

7 High Quality Low RoB |

Level I |

| Kim et al., 2020 [56] |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

5 Moderate Quality Some Concern RoB |

Level II |

| Kong et al., 2020 [57] |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

9 High Quality Low RoB |

Level I |

| Kuvačić et al., 2018 [58] |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

6 High Quality Low RoB |

Level II |

| Lang et al., 2021 [59] |