1. Introduction

Feature selection and sample selection are two critical preprocessing strategies that substantially influence both the efficiency and effectiveness of neural network training. These techniques not only reduce computational cost but also enhance generalization by focusing learning on the most informative regions of the data space. While feature selection has been extensively studied, progress in sample selection has received considerably less theoretical attention. Few existing methods provide a rigorous foundation or demonstrate empirical performance comparable to advances in related fields such as optimal experimental design.

Approaches to accelerating neural network training through data selection can be broadly categorized into two groups: methods that modify the

content of the dataset, and those that selectively determine

which samples are used during training. Content-oriented techniques include data pruning, which removes redundant or low-value examples [

1], and dataset distillation, where the original dataset is replaced with a compact, synthetic representation of each class [

2]. Other strategies directly modify training examples, such as masking less informative pixels [

3] or ranking examples by their contribution to predictive performance [

4]. While these approaches can be effective, they often incur high computational costs and lack a principled selection criterion grounded in information theory.

Recent research increasingly recognizes that optimizing the dataset itself can yield substantial gains in training efficiency. Mahmood et al. [

5] introduced a framework that balances annotation cost against model accuracy. Other studies have sought to minimize dataset size while preserving informativeness through techniques such as coreset selection ([

6,

7]) and bilevel optimization ([

8]). Active learning ([

9,

10,

11]) and curriculum learning ([

12,

13]) further exemplify this paradigm shift toward actively optimized, information-rich subsets. Our work extends this line of inquiry by introducing a cross-entropy–based selection criterion grounded in Shannon’s information theory and Fisher geometry, providing a tractable approximation to G-optimality—widely used in optimal design theory—within the context of deep model training. A related line of work is the recently proposed Structural-Entropy-Based Sample Selection (SES) method [

14], which extends entropy-based selection to graph-structured datasets. SES employs structural entropy to preserve the global topology of the data manifold, emphasizing representativeness and diversity at the group level.

In contrast to approaches focusing on architectural scaling or loss shaping, our method directly targets the

data distribution that underlies training efficiency. The development of our framework is guided by cognitive and neuromotor mechanisms underlying handwriting, which provide both conceptual and stochastic foundations for our model. Neuromotor variability serves as an intrinsic

noise source in Shannon’s communication framework, perturbing the intended prototype and generating observable diversity across samples. Concurrently, Rosch’s prototype theory [

15] established that human categories are organized around central, highly typical members—an insight that motivates our use of class-conditional means as

pivots or prototype representations. Plamondon and Srihari [

16] modeled handwriting as a generative process governed by stroke-level motor commands, reinforcing our interpretation of each observed image as an affine transformation of an idealized prototype corrupted by neuromotor noise. Lake et al. [

17] further demonstrated that capturing such generative structure enables human-level one-shot learning of characters, aligning with our goal of constructing minimal yet expressive training subsets that span the natural variability of each class.

Nevertheless, a principled strategy remains necessary to determine which samples should constitute the training set and how to partition data into training and validation subsets—precisely the classical objective of optimal design when positioning experiments in factor space. We hypothesize that explicitly evaluating the information content of samples provides a rigorous foundation for constructing optimized training sets. Conceptually, our approach draws on optimal experimental design, where sampling points are chosen to maximize an information criterion (e.g., determinant-based D-optimality, variance-based G-optimality, or eigenvalue-based E-optimality), thereby ensuring high informativeness and broad representational coverage of the design space.

These cognitive and algorithmic insights jointly motivate our entropy-based training set construction framework. Rather than relying on random sampling or uniform coverage, we employ a principled divergence-based criterion that selects examples conveying maximal information under a realistic generative model of the data. We instantiate this framework in the

cross

Entropy

Maximum (

cEntMax) algorithm, which selects a fixed fraction of the dataset based on cross-entropy divergence from class prototypes. The algorithm’s name,

cEntMax, intentionally echoes Mitchell’s seminal

DetMax algorithm [

18]

1, one of the most influential and enduring methods in optimal design.

We investigated training sets comprising fractions and observed consistent performance gains across most of this range. The improvement is most pronounced for , where cEntMax enables efficient learning from substantially smaller subsets compared with the commonly adopted—now almost canonical—training fraction of for the full dataset. At the same time, the algorithm stabilizes the loss curve by reducing oscillations through enhanced sample informativeness and diversity.

We discuss the theoretical foundation of this framework in

Section 2, extending Shannon’s communication model to interpret samples as stochastic signals transmitted through a noisy channel formed by the human cognitive system, while incorporating neuromotor and symbolic mechanisms underlying handwriting generation. Variability arises naturally from the interplay between prototype representations, motor transformations, and cognitive perturbations such as stress or attention fluctuations.

Section 3 formalizes training samples as random variables,

Section 4 describes the neural network model, and

Section 5 presents the information-theoretic basis of our approach. The

cEntMax algorithm is detailed in

Section 6, and experimental results are reported in

Section 7. All experiments employ a convolutional neural network [

19] as the classification model.

Finally, this framework opens several research avenues, discussed in

Section 10 and

Section 9. Potential extensions include incorporating structural entropy for graph-structured data, adapting the approach to online and continual learning, enhancing robustness to label noise, coupling with neural architecture search, and applying information-theoretic metrics to analyze training dynamics. The theoretical link to G-optimality and the convex encompassment principle further reinforces the geometric and statistical justification of our method, underscoring its applicability beyond handwritten character recognition. Additional technical background details are provided in the appendices.

2. Theoretical Motivation: The Mind as a Noisy Communication Channel

2.1. The MNIST dataset

To ground the discussion, we consider the MNIST dataset [

19], which contains handwritten digit images collected from a broad demographic. MNIST was derived from NIST SD-1 (high school students) and SD-3 (U.S. Census Bureau employees) and constructed to mitigate legibility differences between these sources [

20,

21]. The final dataset merges both in balanced proportions.

Table 1 represents the structure of the MNIST dataset.

We thus have a complete set of grayscale images labeled into classes. The canonical split provides training and test images. Each image s is a matrix of integers in . Images are centered by centroid alignment and then flattened to , so each sample , , is represented by features.

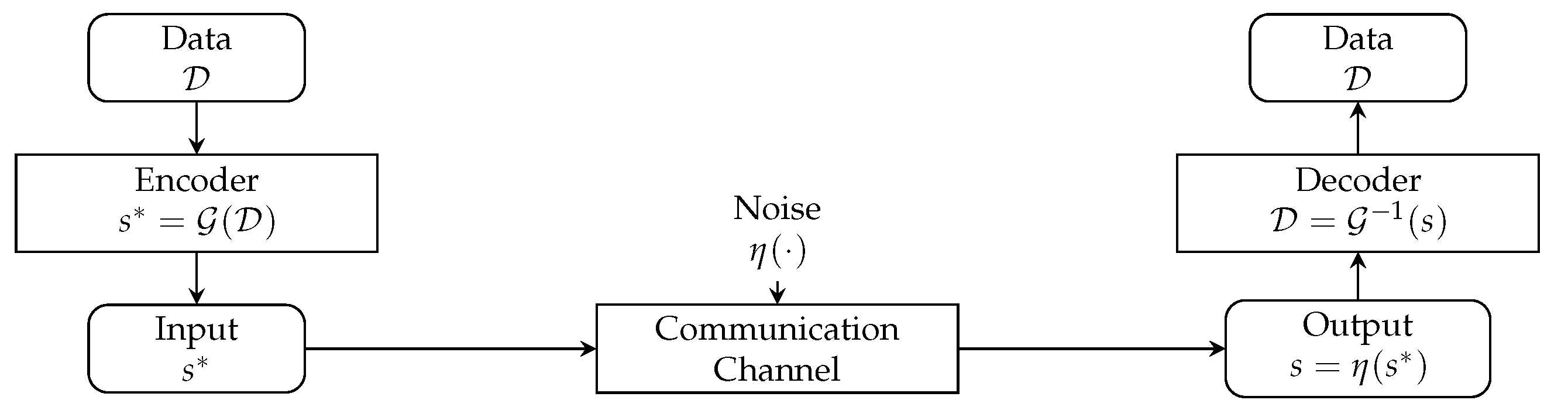

2.2. Shannon’s model of noisy communication channels

Figure 1 illustrates Shannon’s noisy-channel model. A source emits

data , encoded by rules

into a transmissible message

:

The channel corrupts

via noise

, yielding the received signal

s:

The receiver applies a decoder

to reconstruct the data:

Consider

m data types

with corresponding inputs

. Repeatedly using the channel for class

j, we transmit

a total of

times, each with an independent noise realization

, producing

:

Thus

generates a

cluster of corrupted variants,

Hence,

represents a random sample from the distribution of noisy realizations generated by

acting on prototype

. Let

denote the set of class pivots (prototypes), and let

be the full sample collection. Each

serves as an idealized reference (prototype) for class

j, while elements of

are noisy realizations generated under varying channel conditions. The prototype also acts as a

model for the class cluster, a role exploited later in

Section 3.3 and operationalized in the

cEntMax algorithm.

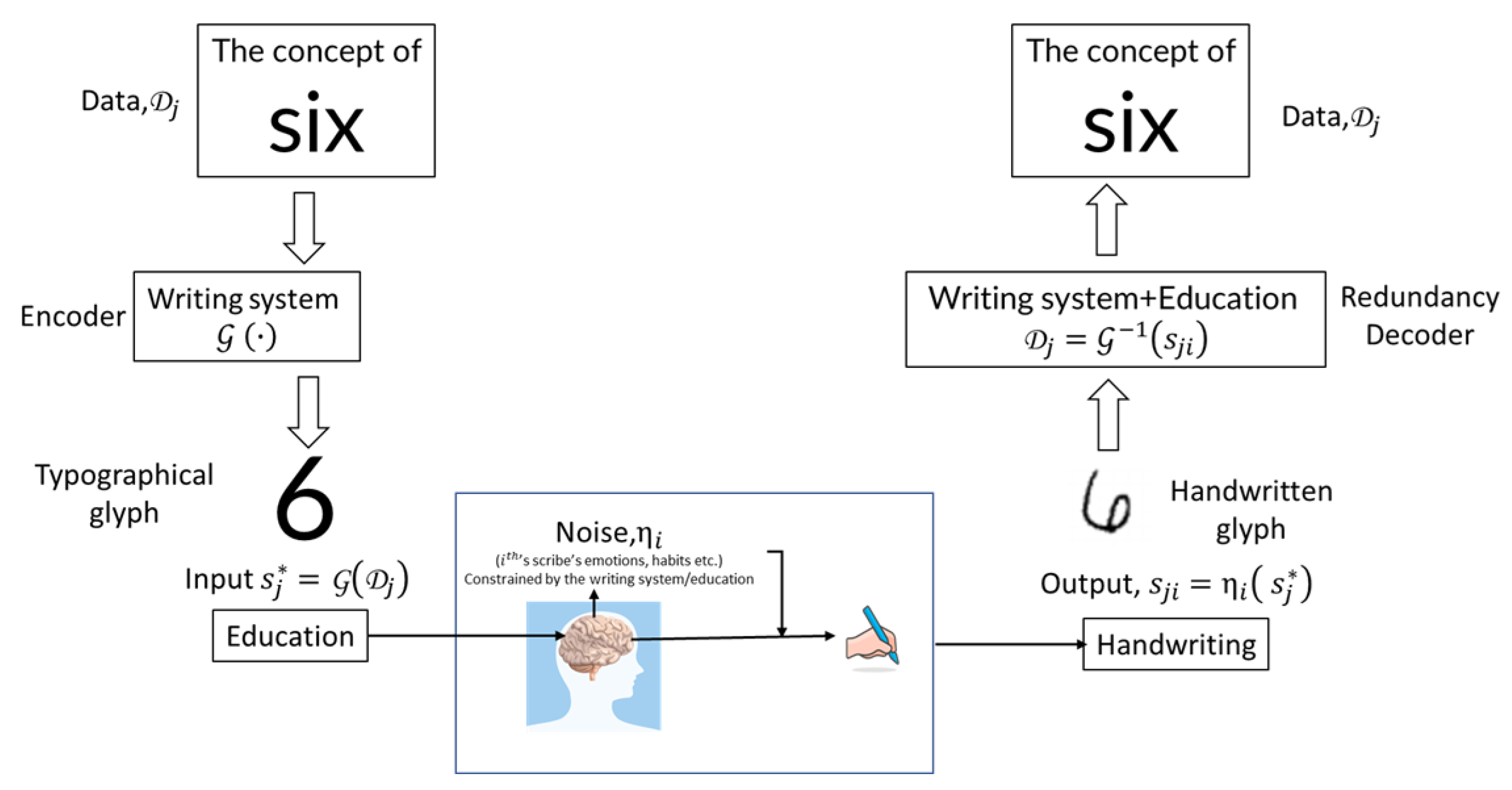

2.3. Handwriting as a neuromotor process influenced by symbolic input

Human handwriting emerges from neuromotor control guided by internalized symbolic representations—learned visual forms and compositional rules of a writing system. Using MNIST as an example (

Figure 2), each image reflects a cognitive–perceptual–motor pipeline: an abstract numerical concept is retrieved, mapped to a canonical glyph, and executed via motor programs shaped by education and practice.

Both U.S. Census Bureau employees and high school students (hereafter, scribes) who contributed to SD-3 and SD-1 were trained within comparable educational frameworks. Throughout their education and life experience, scribes learn to associate abstract concepts (e.g., “six”) with standardized glyphs; through repeated exposure and practice, these mappings become long-term internal representations. When prompted to write a digit, the brain retrieves the corresponding glyph and initiates a sensorimotor sequence. At the same time, this process is influenced by emotional state, stress, and external distractions, as well as by physiological and motor factors that introduce variability in movement execution. Consequently, the resulting handwritten digit constitutes a noisy realization of an internal prototype.

Within this analogy with the Shannon’s noisy channel, the concept is the data; the internalized writing system acts as the encoder, producing the mental glyph ; the neuromotor pathway is the channel with noise ; and the decoder is the reader’s internalized codebook that maps the handwritten sample back to the intended concept. The decoding leverages redundancy in the writing system (consistent glyph shapes and constraints), allowing robust identification even under distortion.

Formally, for each of the scribes assigned to digit j:

Data (concept):.

Encoder (writing system): maps

to a prototype glyph

:

Channel and noise (neuromotor variability):

Decoder (reader’s codebook):

Each

is thus a scribe-specific realization of

under scribe’s own noise

. In this simplified framework we assume that

encompasses all specifics of each of the scribes. We designate

as the

pivot (prototype) and the set

as the class-specific variants. This cognitive–communication view aligns with Shannon’s framework and motivates the information-theoretic analysis adopted in subsequent sections. It provides the foundation for modeling each handwritten sample as a random vector generated from a prototype under affine or additive noise, as developed in

Section 3.3.

3. Random Variables and Entropy-Based Selection

In supervised classification, the dataset is modeled as independent draws from an unknown joint distribution

over input space

and label space

. Each pair

is a realization of

, and the dataset comprises

N such pairs:

This probabilistic framing justifies the standard objective of approximating the conditional distribution

, where a softmax layer induces a probability mass function over labels. Modeling samples as random variables enables principled use of entropy and divergence measures and aligns learning with Shannon’s communication view of information flow through noisy channels.

3.1. Formal definition of a discrete random variable

Let

z be a discrete random variable described by the triplet

[

22], where

is a finite alphabet,

is an observed outcome,

is a probability mass function with and .

We write to emphasize its distributional nature. Two such variables are comparable if they share a common alphabet (i.e., common support). When they also have the same distribution and are independent, they are i.i.d.

3.2. Softmax as a probability estimator

Following [

23], given scores

, the softmax function

maps

B to a probability vector

. Crucially softmax has probabilistic meaning when

B represents realizations of a random vector; otherwise, the output superficially resembles probabilities but lacks a stochastic interpretation.

3.3. Inputs as random variables and cognitive interpretation

As established in

Section 2, each observed sample

arises from a random transformation

applied to a class pivot

:

with

the number of realizations (scribes) in class

j. After flattening

to

, and considering (

10) we map it to a categorical distribution over

n perceptual components (pixels):

obtaining a random variable

with

. Applying the same transformation to the pivot

yields

.

Since

and

share the same alphabet (pixel positions), they are

comparable on a common support:

Within a class, the realizations

are modeled as i.i.d. draws from a class-conditional family induced by the pivot and its affine perturbations. This motivates using the cross-entropy from pivot to sample as an informativeness score:

which ranks samples by their divergence from the prototype (equivalently, by

up to an additive constant).

3.4. Labels as random variables

3.4.1. Ground-truth labels as degenerate random variables

Let

denote the

true class label. The corresponding one-hot encoding is

where

is the Kronecker delta function.

Equivalently,

defines a degenerate probability mass function (pmf)

supported on class

:

Thus, the true label can be interpreted as a degenerate random variable taking value with probability one.

3.4.2. Predicted labels as random variables

Let

be the network logits for input

(cf. Eq. (

19)). Since the neural network

is deterministic but its input is modeled as random, the output vector becomes a random variable. Softmax yields the predictive pmf:

giving

with

. Since

, the canonical use of cross-entropy loss is well-defined:

4. Neural Network Architecture and Training Procedure

As a working example, we use a deep convolutional neural network (CNN) [

19,

24], denoted by

. We assume that

comprises

L layers and is trained on a training set

of size

. Being a deterministic mapping, the network transforms each flattened (random) sample

(originating from

) into a vector of logits

:

Here,

denotes the trainable parameters (including biases), and

represents the fixed network architecture and macro-hyperparameters (layer configuration, activation functions, optimizer, etc.). Training seeks the parameter set that minimizes the empirical loss

over the training data:

where

denotes the log-likelihood (or negative loss). After training on

, the resulting fitted parameters

define the trained model:

Train/validation split.

We acquire the training set

by splitting the general dataset

according to a prescribed proportion

:

where

is the validation set, by

one denotes the set’s cardinality.

Epochs, batching, and objective.

Training proceeds in epochs. After shuffling , we partition it into batches of size . Each epoch iterates over all batches, applying forward/backward propagation passes and an update rule (e.g., Adam). This repeats until a stopping criterion is met (number of epochs or validation-based early stopping).

For discrete distributions

(true label pmf) and

(predicted pmf) on the same support, the cross-entropy is

Here

corresponds to the one-hot target

(degenerate pmf), and

is the predictive categorical random variable induced by softmax on

(see

Section 3).

Validation.

At the end of each epoch we evaluate on the validation set:

where

are predicted labels for

, and

are ground-truth labels. See [

25,

26] for a review of performance measures. Background on deep learning architectures is provided in [

24], and mathematical foundations of deep networks in [

27].

5. Information-Theoretic Basis of the cEntMax Criterion

5.1. Stochastic Sample Generation and Pivot Estimation

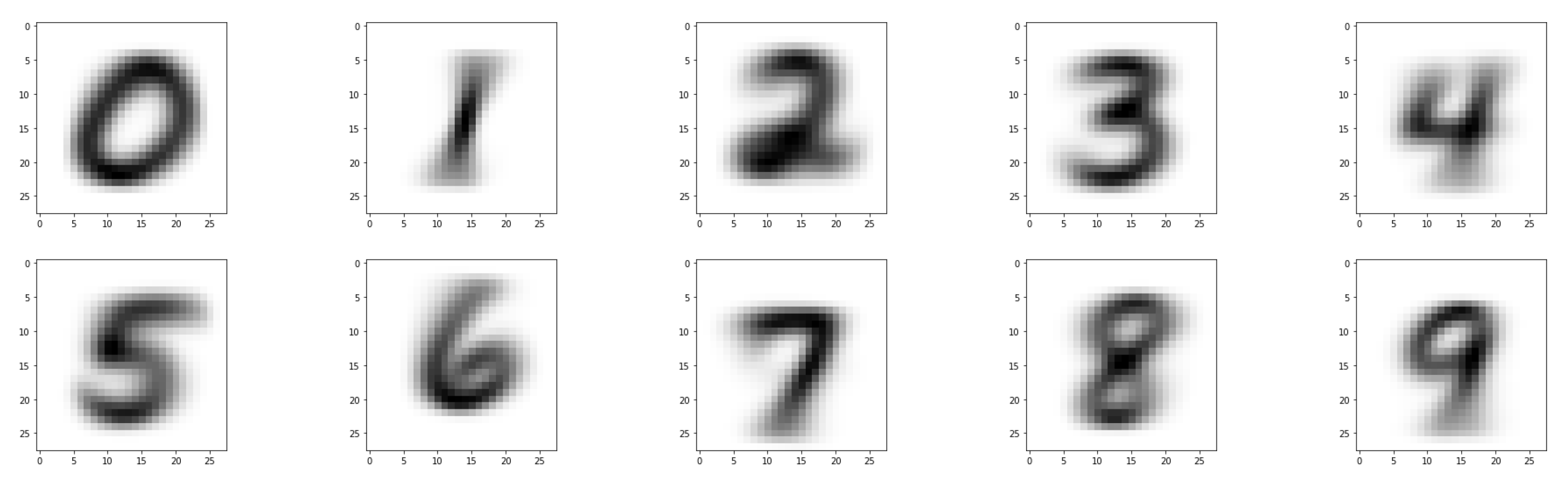

Figure 3 visualizes the

stacked images in each MNIST class: superimposing all samples reveals a sharp central shape surrounded by a diffuse halo. This empirical picture suggests a class-specific

prototype (pivot) with structured variability around it, consistent with cognitive evidence on category prototypes [

15] and neuromotor accounts of handwriting [

16,

17].

Affine-noise channel model.

We formalize each observed sample as a stochastic affine perturbation of a latent pivot

:

where

capture per-pixel multiplicative (stroke/intensity–dependent) and additive (background/digitization) noise, respectively.

2 The perturbed signal is then quantized to the 8-bit lattice:

From stacks to a local Gaussian surrogate.

Let

and vectorize images as

. Conditionally on the pivot, the class cluster

is well summarized (as suggested by the stacked means in

Figure 3) by a local Gaussian surrogate:

with the isotropic special case

providing a tractable approximation to the true (quantized) distribution.

Estimating the pivot by averaging the cluster.

Under the affine–noise model with zero-mean stationary perturbations, the class pivot is not observed but can be consistently estimated by the empirical mean of the cluster in either matrix or vector form:

Then and , so as . This averaging step operationalizes the intuition conveyed by the stacked images: the visible central shape is precisely the pivot estimator.

Divergence to the pivot.

After quantization, all pixels take values in

, yielding a shared per-coordinate alphabet. For divergence computations on a common support, we map images to pmfs via pixelwise softmax to obtain

and

, and score samples by their cross-entropy to the pivot:

The empirical pivot thus plays a dual role—model of the class distribution and estimator of the latent prototype—so large flags samples that are poorly explained by the current prototype and therefore highly informative.

5.2. Maximizing the Total Entropy of the Training Set

Once class pivots are estimated, we seek a training subset

that maximizes overall informativeness. Let

denote the full dataset,

the training subset, and let training on

yield parameters

and predictions

for

(cf. Eq. (

21)). Ideally, we would select

to minimize expected validation loss:

Because direct optimization of (

30) is intractable, we introduce an entropy-based surrogate that prioritizes informative, uncertain samples.

Entropy-based surrogate.

Let

denote the predictive entropy for sample

s under the model trained on

. We select the subset maximizing cumulative entropy:

Intuitively, high-entropy samples correspond to regions of model uncertainty, where providing labeled examples yields the greatest information gain for refining decision boundaries. This aligns with the principle of optimal experimental design, which prescribes performing measurements at points of maximal predictive variance.

Heuristic connection to local linearity.

Although local linearity is not assumed in our derivation, it offers geometric intuition. In piecewise-linear networks (e.g., ReLU CNNs), entropy peaks in transitional regions where small logit perturbations flip class predictions. These regions correspond to high-curvature directions of (

32), reinforcing the link between entropy, sensitivity, and Fisher information without requiring strict linearity assumptions.

Connection to G-optimality.

In classical optimal design theory, G-optimal designs minimize the maximum prediction variance, typically by selecting boundary points of the convex hull [

28]. Our entropy surrogate (

31) extends this intuition to nonlinear models: high-uncertainty samples act as variance-inflating inputs that improve predictive uniformity and reduce extrapolation risk.

Operational criterion.

Within each class, we rank samples by their cross-entropy divergence from the empirical pivot (Eq. (

29)) and select the top fraction as the training subset. Samples with large

are atypical yet class-consistent, thus (i) expanding convex coverage, (ii) aligning with high-variance regions (G-optimality), and (iii) carrying high Fisher information.

Unified objective.

Combining these perspectives, the intractable validation objective (

30) can be approximated by:

This entropy-maximization framework, implemented through classwise cross-entropy selection relative to pivots, provides a tractable approximation to G-optimal sample design under the data’s generative assumptions.

6. The cEntMax Algorithm for Training Set Optimization

As discussed earlier, the general dataset

is split into training and validation subsets:

Rather than selecting

uniformly at random, we propose an information-theoretic construction that prioritizes the most informative

class-specific samples. Concretely, within each class we select samples exhibiting the largest cross-entropy relative to that class’s pivot (empirical prototype).

Classwise i.i.d. structure.

As argued in

Section 2, samples from different classes are not identically distributed. We therefore partition

and assume

within each class

j that samples are i.i.d. realizations of a class-conditional distribution generated from a pivot

via the noisy channel in

Section 5.1. Let

n denote the number of features after vectorization.

Score: cross-entropy to the empirical pivot.

Let

be the empirical class mean (Eq. (

28)) and let

denote its softmax-mapped random variable (

Section 3). For each sample

, with corresponding random variable

, define

Large

values indicate that

is poorly explained by the current prototype model and is therefore informative for refining decision boundaries (cf.

Section 5).

Per-class quotas and imbalance.

Given a global training fraction , we allocate a per-class quota . Any leftover slots are filled by a global “largest remainder” rule across classes using the next-highest values, ensuring and preserving class balance as much as possible.

Softmax mapping used for scoring.

For any vectorized image

we use the pixelwise softmax

this yields

and provides a common discrete support for cross-entropy/divergence across samples and pivots.

7. Experimental Evaluation and Results

For the purposes of this study, we adopted a compact convolutional neural network (CNN), denoted by . The structure of is as follows:

For the purpose of this work, to train the models we use

CrossEntropyLoss function, provided by PyTorch, [

29]. As a minimiser of the loss function, we use the Adam optimizer ([

30]), as provided by the Keras library, [

31], backended by TensorFlow, [

32]. The loss function was

sparse categorical crossentropy, as provided by the Keras, [

31].

We conducted a series of experiments to evaluate the performance of convolutional neural networks trained on subsets of varying sizes and selection strategies. Specifically, we compared two training set selection strategies: random i.i.d. sampling (denoted as Random Split) and selection based on the divergence of the training samples from class-mean prototypes using the cEntMax algorithm (denoted as Mean Split). The examined training subsets comprised , , , and of the full dataset. Each model was trained for 200 epochs, and the validation loss was recorded at each epoch to assess generalization.

The datasets employed for the demonstration the

cEntMax algorithm, are the

EMNIST ByClass [

31] and

KMNIST [

32] datasets. Each of the samples represents a gray scale image of particular handwritten character, represented by a

matrix of integers ranged

. Hence the general set is

.

After flattening, each matrix

is transformed to a vector

,

. Hence the set

will be expressed as a matrix of the

general set, where

n is the number of features of the samples.

Each of the samples

is associated with a

true label, where

denotes the task-specific set of labels (e.g.,

for EMNIST digits,

for EMNIST uppercase,

for EMNIST lowercase, or

characters for KMNIST), one-hot encoded to

, where

and

coincides with the probability distribution of a degenerate random variable; see

Section 3.

The one-hot encoded labels in

will be expressed as a matrix

, where

m is the number of the classes,

The general set

comprising of

training and

validation subsets of samples is associated with the label set

, comprised of

training and

validation subsets of labels respectively, where

The sets

are represented by the matrices

, respectively. Here by

and

we denote the number of samples in the training and validation sets,

.

To train the CNN-based models, we employed two types of training subsets: a randomly constructed one, referred to as the Random split, and another selected using the cEntMax algorithm (Algorithm 1), referred to as the Mean split. The originally downloaded training and validation subsets were first concatenated to form a unified sample pool , whose elements were randomly permuted using a uniform random number generator to eliminate ordering bias.

For the

Random split, the pool

was partitioned into a training subset

and a validation subset

according to the selected fraction

For the

Mean split, the same proportion

was used, but the training subset

was constructed by applying the

cEntMax selection criterion to identify the most informative samples with respect to their class prototypes. This ensured that the two configurations shared the same size but differed in the informational quality of their training data.

|

Algorithm 1:The cEntMax algorithm |

Inputs: ▹ network; data; #classes; train fraction

Outputs:; ,

- 1:

Partition into classwise subsets with . - 2:

Compute class pivots ; map to pmfs . - 3:

for to m do

- 4:

for to do

- 5:

- 6:

▹ CE score - 7:

end for

- 8:

Sort by in descending order. - 9:

end for - 10:

for all j; distribute remaining by largest remainders. - 11:

Build from the top per class; assign the rest to ; shuffle . - 12:

Train . - 13:

Evaluate .

|

8. Common Results

Across all datasets, the following general conclusions can be drawn:

For moderate to large data fractions (), cEntMax consistently outperforms random selection.

cEntMax shows the strongest advantage during the early stages of training, when the number of epochs satisfies .

As training progresses (with increasing epoch count), a slight trend of performance degradation is observed—manifested as reduced accuracy or increased loss—for both mean-based and random splits.

At very low data fractions (), the random split exhibits lower oscillations in the loss curve, likely due to its higher stochastic diversity.

8.1. EMNIST dataset

The

Extended MNIST (EMNIST) dataset, introduced in [

31], extends the original MNIST to encompass handwritten digits and characters. It is derived from the NIST Special Database19, presented in the familiar

grayscale MNIST format, and organized into predefined subsets (

splits) designed for various classification tasks:

ByClass: 62 classes — uppercase (A–Z), lowercase(a–z), digits (0–9).

ByMerge: 26 classes — merging uppercase and lowercase alphabetic forms.

Balanced: 47 classes — balanced sample distribution across letters and digits.

Digits, Letters, MNIST: specialized subsets for focused evaluation.

In this study, we use the ByClass split, which contains images representing all 62 alphanumeric classes. Each image is a grayscale character image, which inherits orientation and alignment artifacts from the original NIST source and thus requires dedicated preprocessing.

We apply the following preprocessing pipeline to each image:

Normalization: Conversion to grayscale tensors scaled to .

Centering: The smallest bounding box around non-zero pixels is identified, cropped, and the result is symmetrically zero-padded back to , reducing spatial variance due to writing style.

Flattening: Each image is reshaped into a 784-dimensional vector for compatibility with learning pipelines.

Then we employ one-hot encoding, transforming the original label vector , which contains integer class indices for each sample, into an indicator matrix , where and denotes the set of indicator values.

We train a convolutional neural network (CNN) on training datasets

prepared both randomly and using the proposed

cEntMax algorithm.

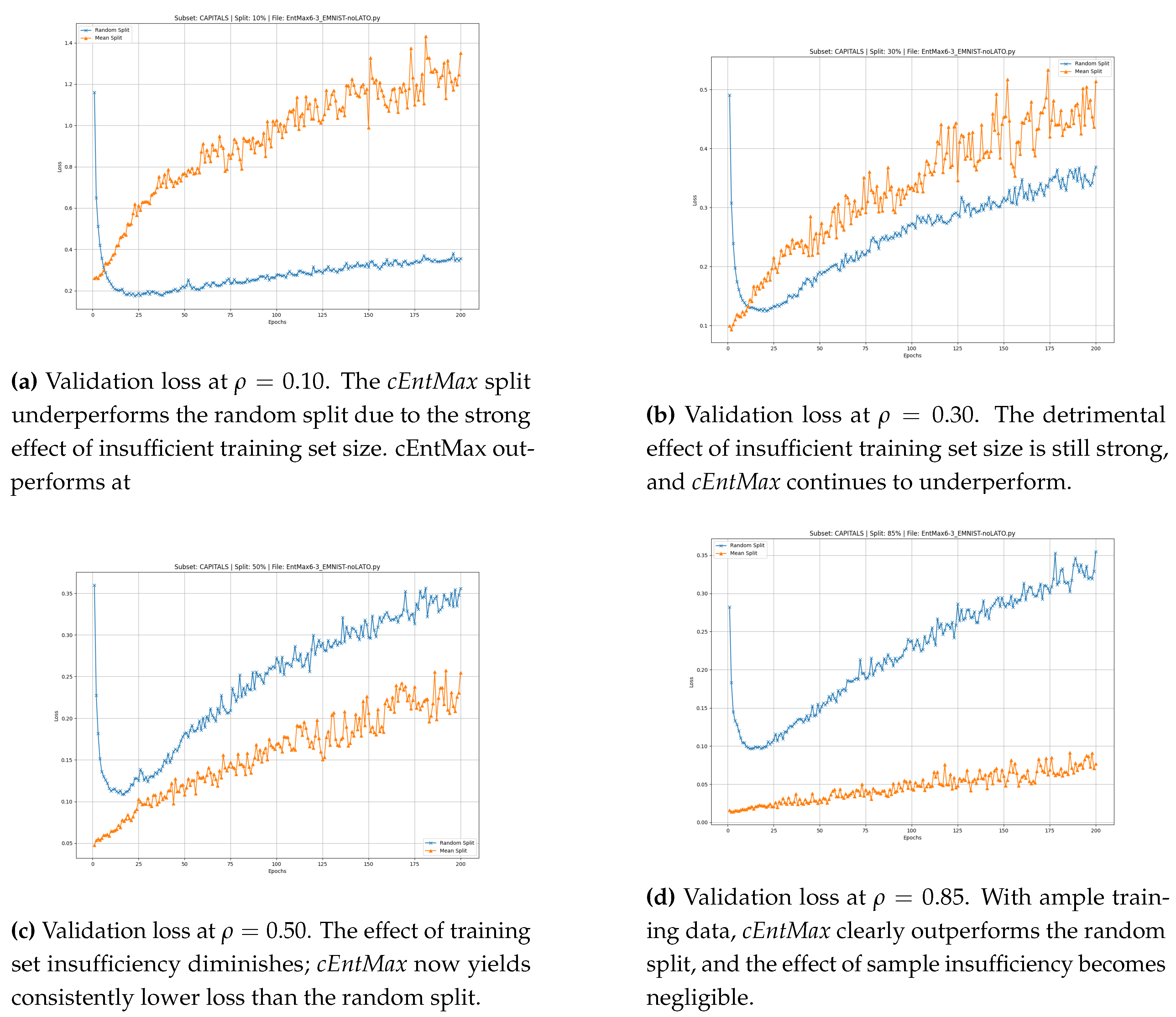

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 present the validation loss trajectories of CNN training when using randomly selected training samples (

Random split) and

cEntMax-selected samples (

Mean split). Experiments are performed at different fractions

of the full training set, with losses monitored over 200 epochs.

At and , the cEntMax subset yields higher accuracy for both uppercase and lowercase letters, while for digits, its advantage appears already at and persists at higher fractions. In contrast to the Mean split, the Random split typically exhibits an upward-pointing tail (high error rate) during the initial epochs, which is later compensated as training progresses.

We now present a detailed analysis of these results in the following section.

8.1.1. EMNIST detailed results

EMNIST uppercase

We begin the analysis with

, corresponding to the conventional MNIST split ratio (

,

). At this setting, the training set selected by

cEntMax yields consistently lower validation loss than the Random split (

Figure 4). The advantage of

cEntMax emerges from the very first epoch, whereas the Random split shows elevated loss during the initial 20 epochs before gradually improving up to epoch

.

Both methods exhibit a steady increase in loss during extended training—more pronounced for the Random split—suggesting mild overfitting as epochs accumulate. This effect is lower at cEntMax. Nevertheless, the cEntMax configuration maintains a clear and persistent advantage throughout the entire training process.

At the next lower training set size,

(

Figure 4) the

cEntMax-selected training set continues to provide markedly better training quality than the random split.

With the reduction of the training set proportion to and further to , the absolute number of informative samples, despite their prioritization, becomes insufficient to sustain a superior loss trajectory.

As a result, the loss curve of cEntMax remains higher than that of the Random split and exhibits more pronounced oscillations. The stochastic composition of the Random split appears to mitigate extrapolation effects arising from validation samples lying outside the convex hull of the training data, leading to a lower overall loss and a smoother convergence profile.

The results for EMNIST-Uppercase across different training fractions are presented in

Figure 4.

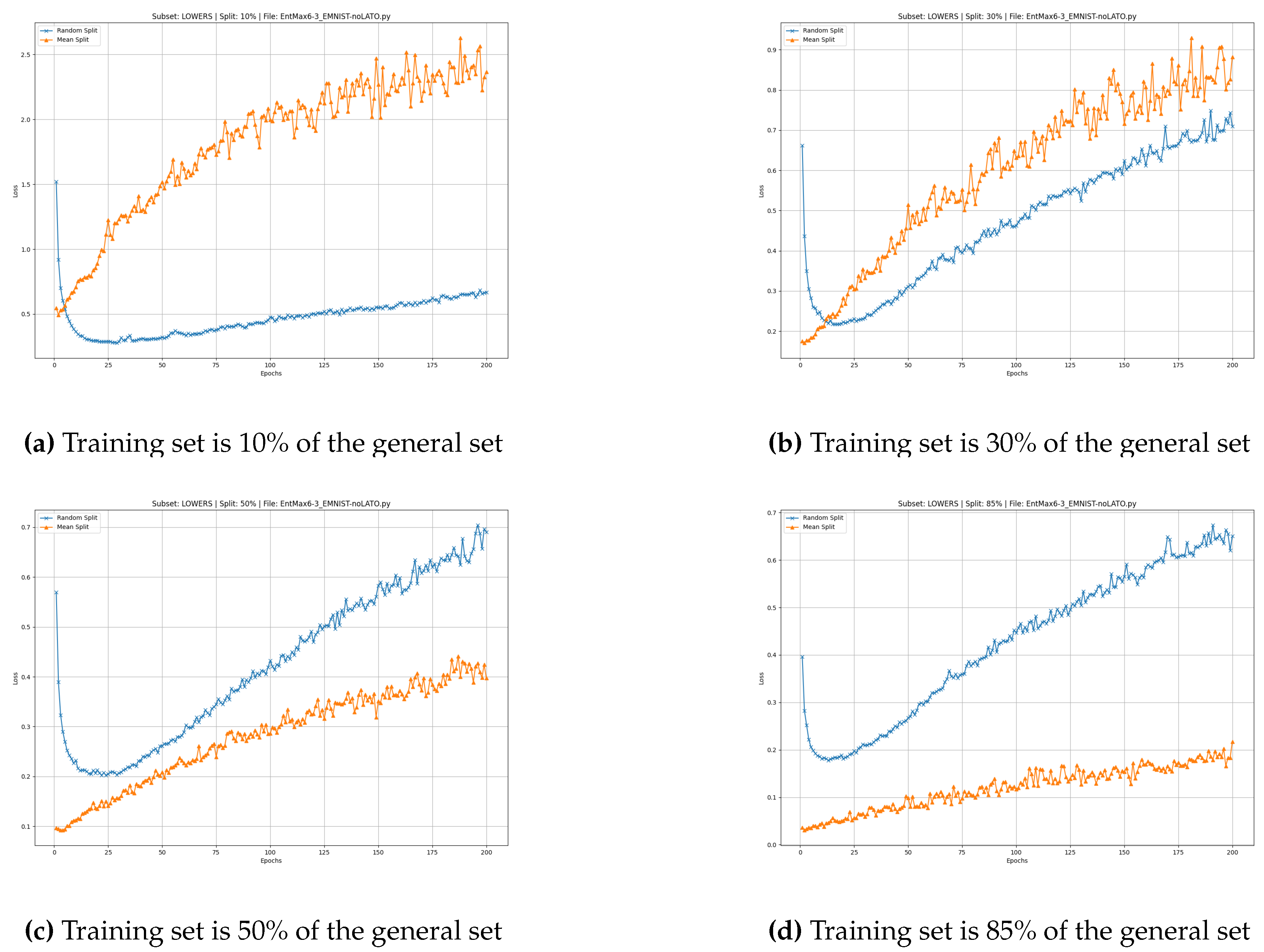

EMNIST lowercase

For the EMNIST-Lowercase dataset, we observe similar overall behavior between the cEntMax and Random-split training subsets. At and , the cEntMax algorithm consistently outperforms random selection by maintaining lower loss values throughout all training epochs.

The oscillatory effect is notably reduced, particularly during the first 50 epochs. An upward-pointing tail during the early epochs remains visible for the Random split, as does the gradual increase in loss associated with overfitting, which appears in all configurations.

However, the effect of limited training data becomes more pronounced at smaller ratios (

and

). In these cases,

cEntMax demonstrates superior model quality already at the initial training stages, while extended training gradually degrades performance due to cumulative overfitting (

Figure 5).

In all cases, the oscillatory behavior of the cEntMax loss curve intensifies over time, likely reflecting the interplay between overfitting, which accumulates with training epochs, and the higher informativeness of the selected samples.

These observations indicate that future training regimes may benefit from early stopping criteria or regularization strategies when using

cEntMax-selected training sets, in order to capitalize on their superior initial performance while mitigating the detrimental effects of overfitting at later stages. The results for EMNIST-lowercase at different training set fractions are shown in

Figure 5.

EMNIST digits

The superior performance of

cEntMax is also evident on the EMNIST-digits dataset, which is similar to MNIST.

cEntMax achieves consistently lower loss across all epochs for both

and

. The oscillatory behavior is substantially reduced compared to random selection, with the effect being particularly pronounced at

but also at

, where the upward trend in the loss function due to overfitting becomes negligible. These results are illustrated in

Figure 6 and

Figure 6.

At lower ratios,

and

, the effect of an insufficient number of training samples becomes apparent. At

,

cEntMax still outperforms random selection, but the oscillatory behavior becomes more pronounced. At

, the stochastic nature of the random split appears to dominate over the information content of the selected samples, as shown in

Figure 6 and

Figure 6. Notably,

cEntMax maintains superior performance during the very early epochs (approximately at epochs up to 5; see

Figure 6). At

and

, the oscillations become evident at later epochs (after epoch 20), suggesting that smaller training sets are more susceptible to the factors driving this instability.

These observations indicate that although cEntMax maintains a clear advantage even with limited training data, its ability to suppress oscillatory behavior diminishes as the training set becomes too small.

This emphasizes the need for a sufficient number of samples and a certain degree of stochasticity to fully exploit information-based selection strategies. In very low-sample regimes, further improvements may be achieved by combining cEntMax with additional regularization techniques—such as weight decay, dropout, early stopping, or data augmentation—to mitigate overfitting, stabilize training dynamics, and preserve the benefits of informative sample selection.

The results for EMNIST-Digits across different training fractions are presented in

Figure 6.

8.2. KMNIST dataset

The

Kuzushiji-MNIST (KMNIST) dataset, proposed by Clanuwat et al. [

32], serves as a drop-in replacement for MNIST, targeting handwritten character recognition in historical Japanese scripts. Unlike MNIST digits, KMNIST comprises

grayscale images of handwritten

Kuzushiji — a cursive form of

Kanji and

Hiragana used in Japan from the 8th to the early 20th century.

The dataset poses a more challenging classification problem due to the higher stroke complexity and stylistic variability of Kuzushiji characters, making it a valuable benchmark for models addressing non-Latin scripts and OCR tasks in historical documents.

KMNIST contains:

Classes: 10 Hiragana characters chosen from classical texts.

Image size: pixels, single-channel grayscale.

Split: 60,000 training images and 10,000 test images, following MNIST’s standard partition.

Images are normalized to by scaling pixel intensities and flattened to 784-dimensional vectors. Unlike EMNIST, we do not apply centering or alignment corrections, preserving the authentic writing variability of different scribes.

8.2.1. KMNIST detailed results

We utilize the full KMNIST dataset, retaining all 10 classes, to evaluate the generalizability of the cEntMax algorithm beyond Arabic digits and Latin letters.

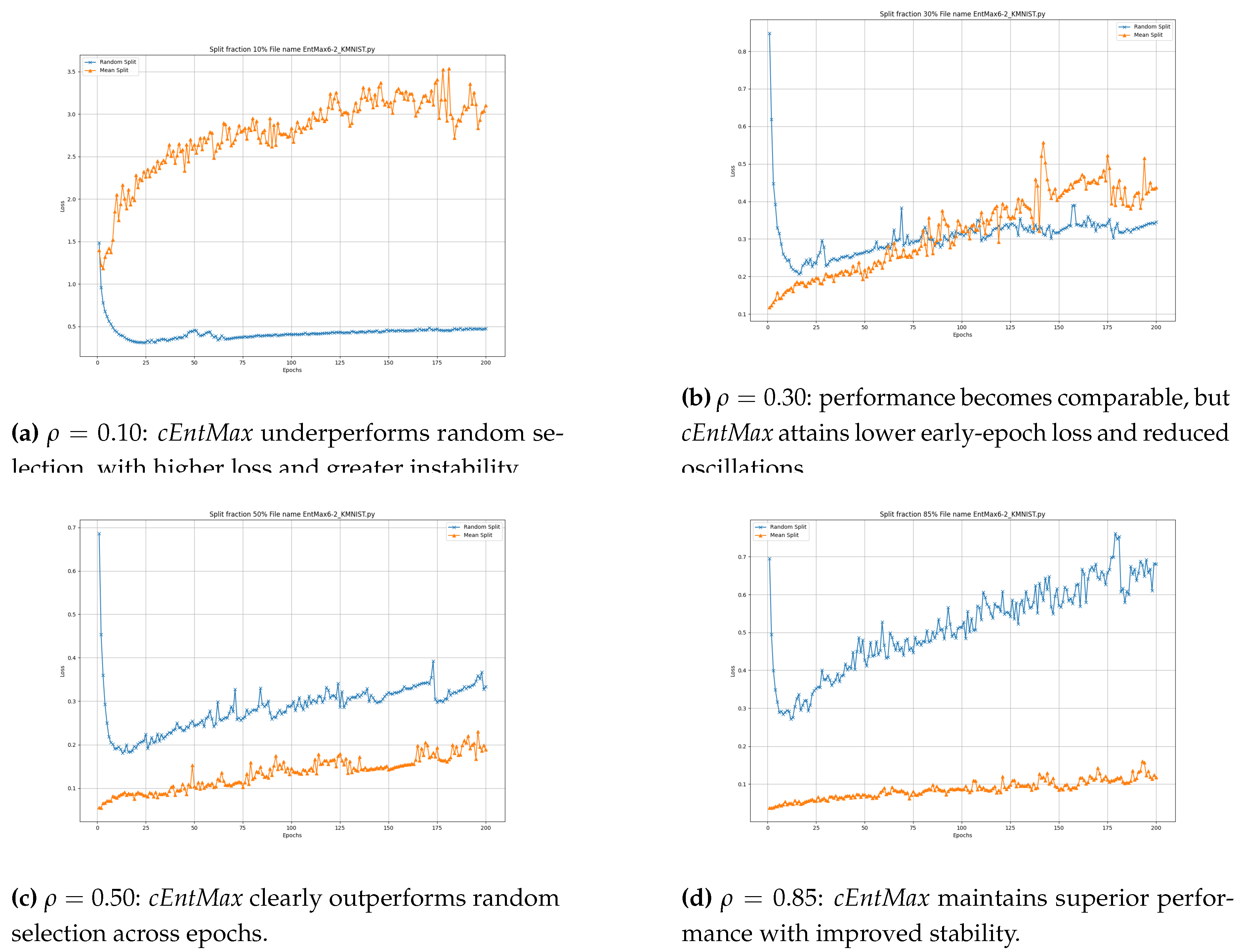

The results on the KMNIST dataset are similar to those observed on EMNIST.

cEntMax outperforms random selection for large training set sizes (

and

;

Figure 7d and

Figure 7c), while the performance of

cEntMax and random selection becomes comparable for smaller training sets (

;

Figure 7b). Notably at

,

cEntMax still achieves lower loss and reduced oscillations during the early epochs (before epoch

). However, at the very small training set size (

;

Figure 7a),

cEntMax underperforms compared to random selection, both in terms of loss value and stability. These results suggest that this type of character dataset may require a greater degree of stochasticity in sample selection when operating in the small or very small data regimes. Overall, the findings indicate that while

cEntMax is effective for larger training sets, incorporating stochastic elements becomes crucial to sustain performance in low-data regimes, particularly for character datasets like KMNIST, which appear to exhibit higher complexity.

9. Conclusions

The experimental results across EMNIST (uppercase, lowercase, and digits) and KMNIST consistently confirm the effectiveness of the proposed cEntMax framework in constructing informative training subsets. For moderate and large data fractions (), cEntMax achieves lower validation loss and smoother convergence than random selection throughout almost all epochs. These improvements are most pronounced during the initial training phase, typically within the first 10–20 epochs, indicating that information-rich subsets accelerate learning by emphasizing the most representative and discriminative samples.

At very small training fractions (), cEntMax provides better early-epoch performance but is eventually surpassed by the random split as training progresses. This inversion is likely due to overfitting on a small, high-entropy subset, whereas the stochastic variability in random sampling implicitly regularizes the model and reduces oscillations.

The KMNIST experiments reveal a similar pattern: clear cEntMax superiority for , competitive behavior for , and underperformance at . Across datasets, the results highlight a consistent trade-off between informativeness and stochastic regularization. The most striking observation is that, under entropy-based selection, strong generalization and stability are often achieved within fewer epochs—suggesting that *less training can be better* when the dataset itself is optimally informative.

Overall, these findings demonstrate that entropy-guided sample selection can substantially improve the efficiency of neural network training without altering architecture or optimization routines, offering a principled and computationally tractable route toward data-centric model design.

Figure 8.

KMNIST: validation loss at different training fractions. Results for . The effectiveness of cEntMax increases with training-set size, while random selection performs comparably or better in very low-data regimes ().

Figure 8.

KMNIST: validation loss at different training fractions. Results for . The effectiveness of cEntMax increases with training-set size, while random selection performs comparably or better in very low-data regimes ().

10. Future Directions

The promising results achieved with the cEntMax algorithm open several avenues for further research and methodological refinement.

- 1.

-

Multimodal Pivot Estimation. The current formulation assumes that samples within each class follow an approximately Gaussian distribution, allowing the class pivot to be represented by the empirical mean. While this assumption holds for unimodal and well-separated classes, many real-world datasets exhibit multimodal or overlapping distributions in which a single mean fails to capture the underlying class structure. In such settings, employing multiple pivots per class—obtained through clustering, mixture modeling, or local manifold decomposition—could provide a more faithful representation of the class-conditional density.

Extending cEntMax to incorporate such multimodal pivot estimation represents a promising direction for future development.

- 2.

Graph-Structured Sample Selection via Structural Entropy. Recent advances show that structural entropy over sample graphs can improve representativeness by capturing global data structure [

14,

33,

34]. Future versions of

cEntMax could integrate structural entropy to balance local informativeness with global coherence. A promising direction is

structural cross-entropy, which evaluates informativeness at the group level by modeling sample relationships as a graph. This would enable selecting sample clusters with high collective uncertainty or diversity, supporting data acquisition strategies that align with both local detail and global structure.

- 3.

-

Online and Continual Learning Extensions. Entropy-based criteria have been applied in continual learning settings to mitigate catastrophic forgetting [

35,

36]. Extending

cEntMax to an online learning regime could enable dynamic and adaptive sample selection in streaming environments.

From a sequential design perspective, this formulation aligns with Wynn’s

sequential optimal design [

37], where each newly acquired observation is selected to maximize an information-based criterion such as the determinant of the Fisher information matrix. In this framework, every incremental sample maximizes the expected information gain, ensuring that data collection proceeds along the steepest ascent in model informativeness.

- 4.

-

Efficient Labeling through Informativeness. Because manual annotation is often expensive and time-consuming, selectively labeling only the most informative samples can greatly enhance the efficiency of data acquisition.

Following the principles of response surface methodology, where experiments are concentrated in the most informative regions of the design space, the cEntMax framework can analogously guide annotation toward samples that provide maximal information gain. Informativeness is quantified through entropy or expected cross-entropy divergence, identifying data points that most effectively refine the model’s decision boundaries.

By prioritizing such high-entropy samples, comparable model performance can be achieved with far fewer labeled examples, substantially reducing human effort and cost while preserving the statistical efficiency of the resulting training set.

- 5.

-

Robustness to Label Noise. High cross-entropy values may indicate samples with uncertain or unreliable annotations, even when labels are assigned manually [

38,

39]. In practice, such high-entropy samples can be interpreted as points where the model exhibits low confidence that the assigned label is correct. Future extensions of

cEntMax could exploit this property by integrating confidence-based filtering or adaptive loss correction, thereby automatically flagging and downweighting potentially mislabeled or ambiguous samples during training.

This would enable the training process to act as a built-in quality control mechanism, improving model robustness in the presence of human or systematic labeling errors.

- 6.

Joint Sample Selection and Architecture Search. Neural architecture search (NAS) frameworks [

40,

41] could benefit from entropy-guided data pruning. Coupling NAS with

cEntMax-based selection may lead to more efficient model-data co-adaptation.

- 7.

Understanding Learning Dynamics through Information Metrics. Investigating the effect of selected samples on training dynamics using Fisher information [

42], Jacobians, or gradient flow metrics may offer insights into why certain examples accelerate learning.

- 8.

Cross-Modality and Domain Generalization. The

cEntMax framework could be extended to non-image data, including graphs [

43], sequences [

44], and signals [

45], where entropy remains a valid proxy for informativeness.

11. Conclusions

In this paper, we introduced a method for improving the efficiency of supervised neural network training, centered on a novel algorithm termed cEntMax. This approach replaces conventional random sampling of training data with a principled strategy that identifies and selects the most informative samples based on their cross-entropy. Grounded in information theory, the method models training samples as i.i.d. realizations of class-conditional random variables and interprets learning as signal recovery through a noisy communication channel, thereby justifying sample selection via entropy as a proxy for information gain.

Our experiments demonstrate that cEntMax substantially outperforms random selection, achieving lower error rates and higher accuracy with considerably fewer training samples. On the EMNIST and KMNIST datasets, models trained on cEntMax-selected subsets consistently reached higher validation accuracy and converged more rapidly than those trained on randomly chosen subsets of equal size. The results also reveal that randomly composed training sets typically exhibit higher error during the early epochs, which diminishes as training progresses. This improvement was particularly pronounced at smaller subset fractions, confirming the effectiveness of entropy-based selection in low-data regimes. In contrast, the cEntMax-based subsets—enriched with highly informative samples—begin training with markedly lower error, suggesting the potential for early stopping and therefore faster, more economical training.

cEntMax introduces only a negligible initial cost for sample evaluation, which is independent of the network architecture and is offset by the substantial reduction in training time and data requirements.

Furthermore, our findings emphasize the complementary roles of informativeness and diversity in training set selection. While cEntMax consistently outperforms random sampling by prioritizing highly informative examples, its advantage decreases at very low training ratios ( and ), where the number of informative samples becomes insufficient to stabilize the loss trajectory. In this regime, the loss curve of cEntMax exhibits stronger oscillations, likely due to the interplay between overfitting and concentrated information gain, whereas the Random split benefits from its stochastic composition, which provides implicit diversity and smoother convergence. These observations suggest that under extreme subsampling, selection strategies may benefit from combining information-based criteria with explicit diversity constraints to further enhance training stability.

Finally, representing training samples as random variables and selecting representative prototype sets per class provides a general framework applicable beyond handwritten character recognition. Future work will extend the cEntMax paradigm to other data modalities and network architectures, and explore hybrid approaches that integrate entropy-based selection with structural diversity and adaptive regularization.

Acknowledgments

The author acknowledges the use of artificial intelligence–based tools for language editing, formatting assistance, and code verification during the preparation of this manuscript. All scientific content, theoretical derivations, experimental design, results, and conclusions were conceived, developed, and validated by the author.

Appendix A. Compatibility of Neural Network Architectures with Local Linearity Assumptions

The proposed method relies on the assumption that the neural network behaves approximately linearly within a local neighborhood of each input sample. This allows the use of a first-order Taylor expansion of the network function

and supports the computation of the Fisher information matrix via the Jacobian:

This local linearity assumption is valid for a wide range of modern neural network architectures.

Table A1 categorizes common network types by their compatibility with the

cEntMax framework.

Table A1.

Compatibility of neural network architectures with the local linearity assumption underlying cEntMax.

Table A1.

Compatibility of neural network architectures with the local linearity assumption underlying cEntMax.

| Network Type |

Activation |

Compatible |

Remarks |

| ReLU-based CNNs |

ReLU |

Yes |

Piecewise linear; enables local linear analysis |

| Smooth activations |

Tanh, GELU |

Yes |

Differentiable; Jacobian and FIM computable |

| Residual networks |

ReLU + skip |

Yes |

Local linearity preserved across layers |

| Linear networks |

None |

No |

Globally linear; no sample-dependent variability |

| Hard-threshold networks |

Step, binary |

No |

Non-differentiable; Fisher information undefined |

The cEntMax framework applies to any architecture that is locally differentiable and admits a well-defined Jacobian in input space. This includes standard convolutional networks with ReLU activations and architectures using smooth nonlinearities. Models that are globally linear or non-differentiable fall outside the scope of the method due to the inapplicability of the Fisher information-based selection criterion.

Appendix B. Fisher Information Matrix and Sample Random Variables

The Fisher information matrix quantifies how much information a random variable carries about an unknown parameter on which its distribution depends. In our context, the parameter of interest is the pivot random variable , whose realization is the pivot sample . Similarly, each observed sample , representing a noisy affine transformation of the pivot, is a realization of a random variable .

Let

X be a random variable with density

, where

is a parameter vector. The Fisher information matrix with respect to

is defined as:

where

is the

score function, which quantifies the sensitivity of the log-likelihood with respect to changes in

.

In our generative setting, each observed sample

is a realization of the random variable

, whose distribution is conditioned on the pivot random variable

, with realization

. The sample is generated as:

where

is a stochastic affine transformation operator drawn independently for each

i. The conditional distribution

defines how likely a sample is, given the pivot random variable.

The Fisher information matrix with respect to the pivot random variable

is then:

This expectation is taken over the random variable

and captures the local curvature of the log-likelihood function around

. Large eigenvalues of

indicate directions in which small changes in the pivot random variable result in large changes in the likelihood of observed samples. These directions represent regions of high local sensitivity and are highly informative for learning.

Appendix C. G-optimal Designs

The development of the cEntMax methodology is motivated by optimal experimental design theory—specifically, the concept of G-optimality. The central idea, inherited from response surface modeling (RSM), is to select design points (or samples, in machine learning terms) that most strongly influence model accuracy and training efficiency.

Let a design be represented as a probability measure

over the design space

. The corresponding

information matrix is

The

G-optimality criterion seeks a design

that minimizes the maximum prediction variance:

According to the General Equivalence Theorem [

46], minimizing this maximum variance is equivalent to minimizing the determinant of the parameter covariance matrix, establishing the duality between G- and D-optimality.

Lemma A1 (Convex Encompassment Principle).

Let be a training set and a validation set, both subsets of a general sample pool . If every can be expressed as a convex combination of elements in ,

then convexly encompasses , ensuring that no validation sample lies outside the representational span of the training distribution.

Convolutional networks, though nonlinear, perform locally linear operations (convolutions and affine transformations) followed by piecewise-linear activations such as ReLU. Consequently, convex encompassment in input space approximately extends to early feature spaces, supporting the theoretical connection between G-optimality and local linearity.

Since high-entropy samples often lie near class boundaries—regions of maximal model uncertainty—selecting them expands the geometric coverage of the training set. Maximizing total entropy on the training set,

therefore serves as a practical analogue of G-optimality, improving interpolation capacity and minimizing validation cross-entropy:

References

- Birodkar, V.; Mobahi, H.; Bengio, S. Semantic redundancies in image-classification datasets: The 10% you don’t need. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1901.11409. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, S.; Tao, D. A comprehensive survey of dataset distillation. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- DeVries, T.; Taylor, G.W. Improved regularization of convolutional neural networks with cutout. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1708.04552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapedriza, A.; Pirsiavash, H.; Bylinskii, Z.; Torralba, A. Are all training examples equally valuable? arXiv 2013, arXiv:1311.6510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, K.; Lucas, J.; Alvarez, M.; Fidler, S.; Law, M. Optimizing Data Collection for Machine Learning. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2025, 26, 1–48. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay, N.; Pontil, M.; Carpentier, A. Determinantal Point Processes for Coresets. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2019, 20, 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, T.; Broderick, T. Automated Scalable Bayesian Inference via Hilbert Coresets. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2019, 20, 1–70. [Google Scholar]

- Borsos, Z.; Jegelka, S.; Krause, A.; Mutny, M. Data Summarization via Bilevel Optimization. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2024, 25, 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Settles, B. Active learning literature survey. PhD thesis, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hanneke, S.; Yang, L. Minimax Analysis of Active Learning. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2015, 16, 3487–3602. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Z.; Kpotufe, S.; Hanneke, S. Regimes of No Gain in Multi-class Active Learning. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2024, 25, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Weinshall, D.; Amir, D. Theory of Curriculum Learning, with Convex Loss Functions. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2020, 21, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Klink, P.; Tanneberg, D.; Peters, J. A Probabilistic Interpretation of Self-Paced Learning with Applications to Reinforcement Learning. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2021, 22, 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, T.; Zhu, J.; Ma, G.; Lin, M.; Chen, W.; Yang, W. Structural-Entropy-Based Sample Selection for Efficient and Effective Learning. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.02268. [Google Scholar]

- Rosch, E. Cognitive representations of semantic categories. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 1975, 104, 192–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plamondon, R.; Srihari, S.N. A framework for on-line handwriting analysis and recognition. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2000, 22, 63–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lake, B.M.; Salakhutdinov, R.; Tenenbaum, J.B. Human-level concept learning through probabilistic program induction. Science 2015, 350, 1332–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, T.J. An Algorithm for the Construction of “D-Optimal” Experimental Designs. Technometrics 1974, 16, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proceedings of the IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Cortes, C.; Burges, C.; et al. MNIST handwritten digit database. 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L. The mnist database of handwritten digit images for machine learning research [best of the web]. IEEE signal processing magazine 2012, 29, 141–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKay, D.J.; et al. Information theory, inference and learning algorithms; Cambridge university press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bridle, J. Training stochastic model recognition algorithms as networks can lead to maximum mutual information estimation of parameters. Advances in neural information processing systems 1989, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press, 2016; Available online: http://www.deeplearningbook.org.

- Muntean, M.; Militaru, F.D. Metrics for Evaluating Classification Algorithms. In Proceedings of the Education, Research and Business Technologies; Ciurea, C., Pocatilu, P., Filip, F.G., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore, 2023; pp. 307–317. [Google Scholar]

- Hossin, M.; Sulaiman, M.N. A review on evaluation metrics for data classification evaluations. International journal of data mining & knowledge management process 2015, 5, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Caterini, A.L.; Chang, D.E. Deep Neural Networks in a Mathematical Framework; Springer, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Pukelsheim, F. Optimal Design of Experiments, classics in applied mathematics; SIAM, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; et al. PyTorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) 2019, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, G.; Afshar, S.; Tapson, J.; Van Schaik, A. EMNIST: Extending MNIST to handwritten letters. In Proceedings of the 2017 international joint conference on neural networks (IJCNN), 2017; IEEE; pp. 2921–2926. [Google Scholar]

- Clanuwat, T.; Bober-Irizar, M.; Kitamoto, A.; Lamb, A.; Yamamoto, K.; Ha, D. Deep learning for classical Japanese literature. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1812.01718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Z. Deep Graph Structure Learning for Robust Representations. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Wu, J.; Chen, G. Structural Entropy Guided Sample Selection for Imbalanced Learning. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 3186. [Google Scholar]

- Zenke, F.; Poole, B.; Ganguli, S. Continual learning through synaptic intelligence. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Aljundi, R.; Lin, M.; Goujaud, B.; Bengio, Y. Task-free continual learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wynn, H.P. The sequential generation of D-optimum experimental designs. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics 1970, 41, 1655–1664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrini, G.; Rozza, A.; Krishna Menon, A.; Nock, R.; Qu, L. Making deep neural networks robust to label noise: A loss correction approach. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, L.; Zhou, Z.; Leung, T.; Li, L.J.; Fei-Fei, L. MentorNet: Learning Data-Driven Curriculum for Very Deep Neural Networks on Corrupted Labels. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zoph, B.; Le, Q.V. Neural Architecture Search with Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Elsken, T.; Metzen, J.H.; Hutter, F. Neural Architecture Search: A Survey. Journal of Machine Learning Research 2019, 20, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kunstner, F.; Balles, L.; Hennig, P. Limitations of the Empirical Fisher Approximation for Natural Gradient Descent. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kipf, T.N.; Welling, M. Semi-Supervised Classification with Graph Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is All You Need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, S.; Kolter, J.Z.; Koltun, V. An Empirical Evaluation of Generic Convolutional and Recurrent Networks for Sequence Modeling. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.01271. [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer, J.; Wolfowitz, J. The equivalence of two extremum problems. Canadian Journal of Mathematics 1960, 12, 363–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 |

The term DetMax refers to determinant maximization, as the algorithm constructs a design that maximizes the determinant of the information matrix, thereby achieving D-optimality. |

| 2 |

Here model intensity fluctuations; geometric transforms (e.g., rotation/translation) can be incorporated by extending but are not required in our analysis. |

Figure 1.

Shannon’s noisy channel. The source is encoded into , corrupted by , and decoded to recover .

Figure 1.

Shannon’s noisy channel. The source is encoded into , corrupted by , and decoded to recover .

Figure 2.

Handwriting as a neuromotor noisy channel. An abstract concept is encoded by the internalized writing system into a reference glyph and expressed through the scribe’s neuromotor system as with neuromotor noise . A reader decodes to recover .

Figure 2.

Handwriting as a neuromotor noisy channel. An abstract concept is encoded by the internalized writing system into a reference glyph and expressed through the scribe’s neuromotor system as with neuromotor noise . A reader decodes to recover .

Figure 3.

Stacked MNIST class images (0–9). Superimposing all samples in a class reveals a sharp central structure (empirical mean) with a diffuse halo, motivating a pivot with local stochastic variability.

Figure 3.

Stacked MNIST class images (0–9). Superimposing all samples in a class reveals a sharp central structure (empirical mean) with a diffuse halo, motivating a pivot with local stochastic variability.

Figure 4.

EMNIST uppercase: effect of training set fraction on validation loss. Validation loss is shown for , comparing cEntMax and random splits. The relative advantage of cEntMax increases with training set size, while the negative impact of insufficient samples is most pronounced at low values of q.

Figure 4.

EMNIST uppercase: effect of training set fraction on validation loss. Validation loss is shown for , comparing cEntMax and random splits. The relative advantage of cEntMax increases with training set size, while the negative impact of insufficient samples is most pronounced at low values of q.

Figure 5.

EMNIST lowercase: effect of training set fraction on validation loss. Validation loss is shown for training set fractions . The performance of cEntMax improves as q increases, reflecting the diminishing negative impact of insufficient training data at larger fractions.

Figure 5.

EMNIST lowercase: effect of training set fraction on validation loss. Validation loss is shown for training set fractions . The performance of cEntMax improves as q increases, reflecting the diminishing negative impact of insufficient training data at larger fractions.

Figure 6.

EMNIST digits: effect of training set fraction on validation loss. Validation loss is shown for training set fractions . The benefit of cEntMax over the random split is already evident at low fractions and persists as the training set size increases.

Figure 6.

EMNIST digits: effect of training set fraction on validation loss. Validation loss is shown for training set fractions . The benefit of cEntMax over the random split is already evident at low fractions and persists as the training set size increases.

Figure 7.

KMNIST: validation loss at different training fractions. Results for . cEntMax gains increase with training set size, while random selection performs comparably in very low-data regimes ().

Figure 7.

KMNIST: validation loss at different training fractions. Results for . cEntMax gains increase with training set size, while random selection performs comparably in very low-data regimes ().

Table 1.

MNIST composition by digit class: per-class counts for the training set (), test set (), and totals (). The full dataset has images in classes.

Table 1.

MNIST composition by digit class: per-class counts for the training set (), test set (), and totals (). The full dataset has images in classes.

| Label j

|

Training

|

Test

|

Total

|

| 0 |

5 923 |

980 |

|

| 1 |

6 742 |

1 135 |

|

| 2 |

5 958 |

1 032 |

|

| 3 |

6 131 |

1 010 |

|

| 4 |

5 842 |

982 |

|

| 5 |

5 421 |

892 |

|

| 6 |

5 918 |

958 |

|

| 7 |

6 265 |

1 028 |

|

| 8 |

5 851 |

974 |

|

| 9 |

5 949 |

1 009 |

|

| Total |

|

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).