1. Introduction

Parthenium hysterophorus is a highly invasive weed that rapidly establishes across diverse climatic regions, including Asia, Australia, West Africa, and the Caribbean, where it colonizes grasslands, croplands, roadsides, and riparian zones (Singh et al., 2005; Javaid and Riaz, 2012). Its aggressive growth severely suppresses native plant communities, reduces forage availability, and leads to significant declines in agricultural productivity. In addition, prolonged exposure causes allergic dermatitis and respiratory complications in both humans and livestock. The invasive success of

P. hysterophorus is largely attributed to its strong allelopathic potential. The plant produces the sesquiterpene lactone parthenin, along with several phenolic acids including vanillic, caffeic, ferulic, chlorogenic, and anisic acids which inhibit seed germination, root elongation, and seedling growth of neighboring species (Singh et al., 2003; Pedrol et al., 2006; Kohli et al., 2006). These allelochemicals accumulate in plant residues and surrounding soils, thereby disrupting nutrient uptake and hindering the establishment of crops and native vegetation over time (Kanchan, 1979; Pandey, 1994). The combined effects of biochemical interference and intense competition for water and nutrients result in widespread displacement of resident vegetation and the formation of near monospecific stands of

P. hysterophorus (Ridenour and Callaway, 2001; Qasem and Foy, 2001; Khaliq et al., 2013; Rajan, 1973; Kanchan, 1975; Kohli and Rani, 1994; Batish et al., 2002; Belz, 2008; Wiesner et al., 2007). Utilizing

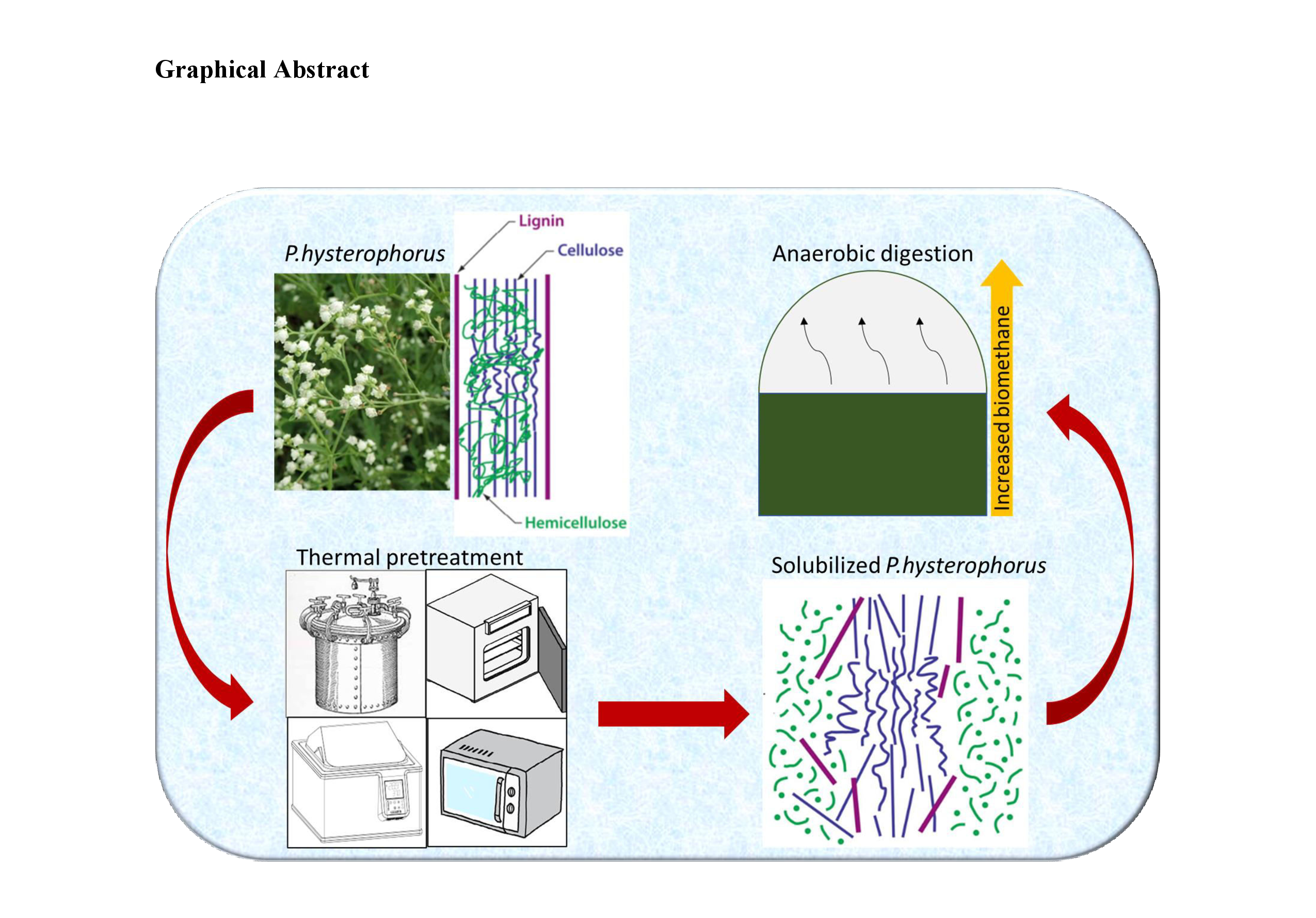

P. hysterophorus as a substrate for anaerobic digestion presents a dual benefit by mitigating its ecological impacts while contributing to renewable energy production in the context of declining fossil fuel resources (Li and Khanal, 2016). However, its lignocellulosic matrix, characterized by high lignin and cellulose contents, is inherently resistant to enzymatic degradation. This recalcitrance prolongs the hydrolysis phase and limits overall digestion efficiency, as schematically illustrated in Graphical abstract. Consequently, appropriate pretreatment strategies are essential to disrupt the lignincarbohydrate complex, enhance substrate solubilization, improve biodegradability, and ultimately increase methane yields from this problematic yet potentially valuable biomass (

Figure 1). Four thermal pretreatment methods were investigated: hot air oven treatment (dry convective heating), hot water bath treatment (wet convective–conductive heat transfer), autoclaving (pressurized steam), and microwave irradiation (dielectric volumetric heating) (Barua and Kalamdhad, 2016; Tampio et al., 2014; Kaatze, 1995). During hot air oven treatment, convective heat transfer initially raises the temperature of the biomass surface, followed by inward heat conduction that disrupts the lignin sheaths encasing the cell walls. In contrast, hot water bath treatment and autoclaving supply moist heat through convection and subsequent conduction, promoting hemicellulose hydrolysis and partial cellulose solubilization. Microwave pretreatment induces rapid volumetric heating by oscillation of polar water molecules, leading to the rupture of hydrogen bonds within the lignocellulosic matrix. Collectively, these thermal approaches disrupt complex structural assemblies, enhance substrate solubilization, and facilitate efficient biomethane recovery during anaerobic digestion.

This study focuses on evaluating multiple thermal pretreatment strategies to optimize methane production from Parthenium hysterophorus biomass under anaerobic digestion conditions. Among the various pretreatment categories biological, physical, and chemical thermal methods exhibit superior effectiveness in disintegrating the lignocellulosic framework, thereby significantly increasing biogas yields through enhanced substrate solubilization and accelerated hydrolysis. To comprehensively assess the structural and chemical modifications induced by pretreatment, advanced spectroscopic and microscopic techniques including field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD), and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) were employed. These analyses demonstrated substantial changes in biomass crystallinity, chemical bonding patterns, and surface morphology following pretreatment, confirming effective lignin disruption and increased exposure of holocellulosic components for microbial colonization. Although thermal pretreatments have been widely reported for various lignocellulosic feedstocks, their targeted application to P. hysterophorus, an underutilized invasive weed, represents a novel approach. This integration not only strengthens invasive species management strategies but also unlocks the potential of this biomass as a sustainable substrate for biogas production, contributing to renewable energy diversification and ecological restoration.

2. Materials and Methods

Parthenium hysterophorus biomass was collected from the institute campus, while fresh cow dung was obtained from a nearby village. Prior to experimentation, the weed biomass was subjected to physicochemical characterization to determine its lignocellulosic composition, including lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose contents, as summarized in

Table 1. For each experimental run, the biomass was chopped and uniformly ground to achieve a consistent particle size, thereby enhancing pretreatment efficiency and reproducibility.

The influence of temperature was systematically examined by subjecting multiple sample sets to different thermal conditions while maintaining a constant exposure time. Conversely, the effects of treatment duration were evaluated by holding samples at the optimized temperature for varying time intervals. Acid insoluble lignin was quantified using a gravimetric method, whereas acid soluble lignin was determined spectrophotometrically at 205 nm using a UV/Vis spectrophotometer.

A non-pretreated sample was used as the control to benchmark the effects of thermal pretreatment on biomass characteristics (DiLallo and Albertson, 1961). Soluble sCOD and VFA were measured in accordance with standard methods prescribed by the American Public Health Association (APHA, 2005). These standardized analytical procedures enabled accurate assessment of pretreatment induced improvements in biomass solubilization and hydrolysis.

2.1. Thermal Pretreatment Methods

2.1.1. Hot Air Oven Pretreatment

Hot air oven pretreatment conditions were selected based on previous studies (Rafique et al., 2010; Barua and Kalamdhad, 2016). Freshly harvested Partheniumhysterophorus biomass was chopped into small pieces and uniformly ground prior to pretreatment. The processed samples were then subjected to temperatures of 80, 90, 100, 110, and 120 °C for 60 min in sealed beakers.Subsequently, time optimization was performed at the selected optimum temperature by varying exposure durations of 30, 60, 90, 120, and 150 min to determine the conditions yielding maximum substrate solubilization

2.1.2. Microwave Pretreatment

Microwave pretreatment was carried out by exposing 50 g portions of ground Partheniumhysterophorus biomass, placed in sealed beakers, to temperatures of 160, 180, 200, and 220°C for 10 min. Subsequently, time optimization was performed by maintaining the samples at the selected optimum temperature for exposure durations of 5, 10, and 15 min. The selected temperature and time ranges were adapted from established lignocellulosic pretreatment protocols reported in the literature (Sapci, 2013; Lin et al., 2015).

2.1.3. Autoclave Pretreatment

The effects of autoclave pretreatment were investigated using 50 g of ground Partheniumhysterophorus biomass placed in sealed beakers and subjected to temperatures of 80, 90, 100, 110, and 120°C for 20min. Subsequently, the influence of treatment duration on biomass hydrolysis was evaluated by maintaining the samples at a fixed temperature for exposure periods of 20, 40, 60, and 80 min. The selected operating conditions were based on previously reported autoclave pretreatment studies on lignocellulosic biomass (Menardo et al., 2012; Toquero and Bolado, 2014; Bolado-Rodríguez et al., 2016).

2.1.4. Hot Water Bath Pretreatment

Hot water bath pretreatment was conducted following methodologies reported in biomass processing studies [Li et al., 2007; Cho et al., 2013]. The effect of temperature was evaluated by immersing sealed beakers containing ground Partheniumhysterophorus biomass in a hot water bath at 70, 80, 90, and 100 °C for 30 min. Subsequently, time optimization was performed at the selected optimum temperature with exposure durations of 30, 60, 90, and 120 min to maximize biomass hydrolysis and solubilization.

2.2. Biomass Characterization

Acid insoluble lignin content in Partheniumhysterophorus biomass was quantified following the standardized National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) protocol, ensuring reproducible determination of this recalcitrant component critical for assessing pretreatment effectiveness. This gravimetric method involves sequential acid hydrolysis to isolate and weigh the acidinsoluble lignin fraction, thereby providing baseline information on the resistance of the lignocellulosic matrix to biodegradation.

Cellulose content was determined using a colorimetric anthrone assay. Briefly, 0.5 g of ground biomass was mixed with 3 mL of acetic–nitric acid reagent and boiled to hydrolyze holocellulosic components. The mixture was then cooled and centrifuged to separate the supernatant, which was subsequently diluted and reacted with anthrone reagent. Color development was achieved by boiling the solution for 10 min, after which absorbance was measured at 630 nm using a UV–Vis spectrophotometer. Cellulose concentration was quantified against a glucose standard calibration curve.

Hemicellulose content was calculated indirectly as the difference between neutral detergent fiber (NDF) and acid detergent fiber (ADF), following the established fiber analysis method of Goering and Van Soest (1975). This sequential fractionation procedure removes soluble carbohydrates, hemicellulose, and lignin, enabling accurate isolation of structural polysaccharides. Following analysis, residues were thoroughly rinsed with distilled water and 67% H₂SO₄ to remove residual interferents, yielding a comprehensive lignocellulosic composition (

Table 1) essential for correlating pretreatment effects with biogas production potential.

2.3. Spectroscopic Characterization

2.3.1. Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy (FESEM)

Biomass samples were prepared for morphological analysis by sputter coating with a thin layer (1.5–3.0 nm) of gold or gold–palladium to enhance surface conductivity and minimize charging effects under high vacuum conditions. FESEM imaging revealed pronounced pretreatment induced disruptions in cell wall integrity, including surface pitting, structural fragmentation, and the exposure of internal fibrillar architectures. These morphological alterations provide direct visual evidence of increased substrate accessibility, thereby facilitating microbial hydrolysis during anaerobic digestion.

2.3.2. X-ray Diffraction (XRD)

Changes in the crystallinity of lignocellulosic components were evaluated using XRD analysis. Powdered biomass samples were scanned at a rate of 5° min⁻¹ over a diffraction angle (2θ) range of 5–60°. Variations in the cellulose crystallinity index (CrI) were quantified by comparing the intensities of characteristic diffraction peaks corresponding to crystalline and amorphous regions, typically observed within the 2θ range of approximately 15–22°. The observed reductions in crystallinity following thermal pretreatment indicate partial amorphization of cellulose, which is strongly associated with enhanced enzymatic accessibility, improved biodegradability, and increased biogas production potential.

2.3.3. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

Chemical bond alterations in the biomass were analyzed using a PerkinElmer Spectrum 2 Fourier FTIR spectrometer. Finely ground, oven dried samples were homogeneously mixed with potassium bromide (KBr) at a mass ratio of 1:100 and compressed into translucent pellets under a pressure of 10 MPa for 3 min. The pellets were scanned over a wavenumber range of 4000–400 cm⁻¹ at a resolution of 4 cm⁻¹, with 16 co-added scans per sample.

Characteristic absorption bands associated with lignin (aromatic C–H stretching at ~1600 cm⁻¹), hemicellulose (C–O stretching at ~1050 cm⁻¹), and cellulose (O–H stretching at ~3400 cm⁻¹) exhibited reduced intensities following thermal pretreatment. These spectral changes confirm partial solubilization and structural reorganization of lignocellulosic components, supporting the enhanced accessibility observed during anaerobic digestion.

2.4. Biochemical Methane Potential (BMP) Assay

Biochemical methane potential assays were performed in triplicate batch reactors to quantify the maximum biomethane yield per gram of volatile solids (VS) from Parthenium hysterophorus biomass under anaerobic conditions. The food to microorganism (F/M) ratio was standardized based on the VS content of both pretreated and untreated substrates to ensure consistent inoculum–substrate interactions across all experiments.

Each 1000 mL reactor was loaded with a homogeneous mixture comprising ground P. hysterophorus biomass (pretreated or control) at the optimized F/M ratio, fresh cow dung as the inoculum, essential macro and micronutrients, and distilled water to achieve a total solids concentration of 8%. Anaerobic conditions were established by purging the reactors with nitrogen gas for 5 min, after which they were hermetically sealed using butyl rubber stoppers fitted with gas sampling ports.

Biogas production was quantified by the liquid displacement method using aspirator flasks containing 1.5 N NaOH to selectively absorb CO₂, allowing measurement of CO₂ free methane volume (Elliott and Mahmood, 2007). Cumulative methane yields were recorded daily until biogas production reached a plateau, defined as less than a 1% increase in daily methane output over seven consecutive days. This stabilization typically occurred within 30–45 days, enabling accurate determination of ultimate methane potential and digestion kinetics for evaluating pretreatment performance.

2.5. Energy Balance Evaluation

Net energy gains from hot air oven pretreatment were calculated to evaluate process viability, treating biomethane as the primary energy output. Operational energy input EU (J/g VS),

Was determined using:

where

P represents pretreatment power consumption (W),

n denotes

P. hysterophorus volatile solids loading (g VS), and E

t indicates exposure duration (s) (Passos et al., 2013).

EQ=ϕ×Qraw equation 2

where ϕ is the lower heating value of methane (35.80 kJ/L CH₄) and Qraw (mL CH₄/g VS) quantifies biochemical methane potential per unit volatile solids (Kuglarz et al., 2013). Energy efficiency was assessed as the ratio EQ/EU, confirming thermal pretreatment's positive energy balance for scalable biogas production from invasive biomass.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Effects of Temperature and Exposure Duration

Temperature and time optimization across thermal pretreatments (hot air oven, microwave, hot water bath, and autoclave) revealed distinct solubilization profiles, with hot air oven demonstrating superior performance for P. hysterophorus lignocellulosic biomass.

3.1.1. Hot Air Oven Pretreatment

Hot air oven pretreatment achieved maximum biomass solubilization at 110°C, as evidenced by pronounced increases in soluble sCOD and VFA, which declined at higher temperatures (

Figure 2a). Temperatures exceeding 120°C promoted VFA volatilization and thermal degradation of readily biodegradable compounds, thereby suppressing subsequent acetogenesis and methanogenesis. This inhibitory effect is consistent with observations reported for other lignocellulosicfeedstocks, where excessive thermal severity impairs downstream anaerobic digestion. At 110 °C, effective cell wall rupture facilitated the release of bound organic matter, significantly enhancing microbial accessibility and resulting in a 51.56% increase in sCOD (2.06 fold relative to the untreated control).

At a fixed temperature of 110°C, sCOD and VFA concentrations increased progressively with treatment duration up to 90 min, after which no substantial further enhancement was observed (

Figure 2b). This trend directly links VFA accumulation to organic matter solubilization, in agreement with earlier findings by Barua and Kalamdhad (2016). The 90 min exposure effectively disrupted the compact lignocellulosic matrix through dry convective heating, where initial surface heating is followed by conductive heat penetration, leading to efficient fracturing of lignin sheaths surrounding cellulose fibers. Although heat penetration depth is limited under dry conditions, this mechanism proved more effective than lower temperature treatments. Elevated temperatures (>100°C) were essential, as sub 100°C regimes preserved lignin–carbohydrate complexes, thereby restricting hydrolysis (Wang et al., 1997).

Comparable studies further corroborate the effectiveness of hot air oven pretreatment. For example, treatment at 80 °C for 90 min enhanced organic solubilization in paper mill sludge, while similar conditions applied to Lantana camara accelerated hydrolysis by 25–30%. Pretreatments near 100°C have also been reported to stimulate hydrolytic microbial activity, functioning as a biological pre-digestion step that yields 2–10% increases in biogas production at 90–110 °C. However, excessive thermal exposure (>120°C) has been shown to reduce biogas output by approximately 4% due to substrate degradation and inhibitor formation (Nielsen et al., 2004). Increased sCOD directly shortens the hydrolysis phase the rate limiting step in anaerobic digestion thereby enhancing biogas production through accelerated bacterial metabolism (Junoh et al., 2015).

Overall, these findings identify hot air oven pretreatment at 110°C for 90 min as the optimal condition for Partheniumhysterophorus biomass valorization. This operating window balances effective lignocellulosic disruption with minimal thermal degradation, aligning well with energy efficient pretreatment strategies for the sustainable conversion of invasive biomass into renewable biogas (Sathyan et al., 2023).

3.1.2. Microwave Pretreatment

Microwave irradiation enhanced biomass solubilization through volumetric dielectric heating; however, its effectiveness was lower than that of hot air oven pretreatment for

Parthenium hysterophorus (

Figure 3a,b). Both soluble sCOD and VFA increased progressively with temperature up to 180 °C, reflecting rapid disruption of lignocellulosic bonds via water molecule polarization and hydrogen bond cleavage. Nevertheless, the overall improvement remained modest, with a 20.55% increase in sCOD (1.25-fold relative to the untreated control), compared with dry convective thermal pretreatment. At temperatures above 180°C, sCOD and VFA declined due to excessive moisture evaporation, Maillard reactions between reducing sugars and amino acids leading to inhibitory melanoidin formation, and protein denaturation. These effects were visually evident as sample browning at 220°C and are known to inhibit downstream acetogenesis and methanogenesis (Carrère et al., 2010; Barua and Kalamdhad, 2016).

The comparatively limited performance of microwave pretreatment can be attributed to its high penetration depth (approximately 10–20 cm, compared with 1–2 cm for conductive heating), which promotes uneven energy distribution, localized thermal hotspots exceeding 250°C, and premature carbohydrate degradation rather than selective lignin disruption. Previous studies have reported optimal microwave pretreatment temperatures for lignocellulosic biomass within the range of 150–200°C. For instance, rice straw treated at 180°C for 10 min exhibited a 25% increase in sCOD, which declined by approximately 15% at 210°C due to the formation of furfural and related inhibitory compounds. Similar temperature dependent trends in VFA and sCOD were observed for wheat straw, with maxima at 170–190 °C followed by thermal decomposition at higher severities. Excessive microwave heating has also been shown to denature hydrolytic enzymes and volatilize soluble organics, reducing net biogas potential by 10–20% (Karthikeyan et al., 2024).

At a fixed temperature of 180°C, sCOD and VFA concentrations increased with exposure time and reached a maximum at 15 min (

Figure 3b), beyond which refractory compound formation and excessive energy input diminished pretreatment efficiency (Barua and Kalamdhad, 2016). This behavior is consistent with kinetic models describing microwaveassisted hydrolysis as a first order process that plateaus once readily accessible holocellulosic fractions are depleted. Comparable studies have reported optimal exposure times of 15–30 min, including food waste treated at 180 °C for 15 min, which achieved a 30% increase in biogas yield, and

Lantana camara, which peaked at 180 °C for 20 min with an 18% sCOD enhancement prior to inhibitor accumulation.

Although microwave pretreatment offers rapid heat transfer rates 10 to 100 times faster than conventional convective heating it requires precise operational control to avoid over pretreatment. Consequently, microwave irradiation may be suitable for small scale or decentralized processing of invasive biomass, but its higher energy demand and lower solubilization efficiency render it less favorable than hot air oven pretreatment for large scale P. hysterophorus valorization. Overall, a microwave pretreatment condition of 180°C for 15 min emerges as viable but inferior to hot air oven pretreatment for scale up applications.

3.1.3. Autoclave Pretreatment

Autoclave pretreatment, employing saturated steam under pressure, produced a non-linear solubilization response, with soluble sCOD and VFA increasing up to 100 °C, declining at 110 °C, and rising again at 120 °C (

Figure 4a). At 100 °C, sCOD reached 14,210 mg L⁻¹, slightly exceeding the value obtained at 120 °C (13,900 mg L⁻¹), indicating that 100 °C was the most effective operating condition despite the secondary peak observed at higher temperature. This behavior reflects a balance between enhanced hydrolysis and the onset of thermal degradation and aligns with previous reports on cereal residues such as barley and wheat, where optimal autoclave pretreatment typically occurred within the range of 100–121°C, while excessive severity reduced net solubilization and methane yields (Menardo et al., 2012; Toquero and Bolado, 2014).

Time optimization conducted at 100°C demonstrated that sCOD and VFA concentrations increased with exposure duration up to 60 min, beyond which further heating provided no additional benefit and, in some cases, reduced solubilization efficiency (

Figure 4b). Under the optimal condition of 100 °C for 60 min, sCOD enhancement reached 40.85%, corresponding to a 1.69 fold increase relative to the untreated control. These results confirm that autoclave pretreatment is moderately effective for

Partheniumhysterophorus biomass, although less impactful than hot air oven pretreatment. The close correspondence between VFA and sCOD trends further supports their direct relationship, as elevated sCOD indicates greater release of fermentable organics that are subsequently converted to VFAs during the early stages of anaerobic digestion (Carrère et al., 2010).

In steam based pretreatment systems, moist heat provides greater penetration than dry heat, effectively disrupting lignin carbohydrate complexes. However, prolonged exposure or excessive temperatures can induce protein denaturation, sugar degradation, and the formation of recalcitrant or inhibitory compounds, thereby limiting further increases in sCOD and potentially constraining downstream biogas production (Li et al., 2022).

3.1.4. Pretreatment by Hot Water Bath

Hot water bath pretreatment, employing saturated liquid water as the heating medium, exhibited a clear temperature dependent solubilization behavior for

Partheniumhysterophorus biomass (

Figure 5a). Both soluble sCOD and VFA concentrations increased progressively as the temperature rose from 70 to 90 °C, followed by a decline at 100 °C, indicating that 90 °C was the most favorable temperature within the tested range. The reduction in sCOD and VFA at 100 °C can be attributed to partial volatilization and thermal degradation of VFAs and other soluble organics, consistent with reports that excessive hydrothermal severity promotes the transformation or loss of fermentable compounds into refractory or inhibitory products (Thi et al., 2017; Gil et al., 2018). Compared with lower temperature treatments (70 and 80 °C), pretreatment at 90 °C provided sufficient thermal energy to disrupt the lignocellulosic matrix and enhance solubilization without exceeding the threshold at which degradation becomes dominant.

Time optimization at 90 °C further demonstrated that sCOD and VFA concentrations increased with exposure duration up to 90 min, after which both parameters declined (

Figure 5b). Under the optimal condition of 90 °C for 90 min, the maximum sCOD enhancement reached 44.14%, corresponding to a 1.79 fold increase relative to the untreated control. This confirms that 90 °C for 90 min represents the most effective hot water bath pretreatment condition for

P. hysterophorus within the investigated temperature time gap. The parallel trends observed for sCOD and VFA underscore their close coupling, as increased sCOD reflects greater release of soluble organic matter that is subsequently converted into VFAs during the early stages of anaerobic digestion (Carrère et al., 2010). Similar temperature–time interactions have been reported for other lignocellulosic substrates; for example, Thi et al. (2017) identified an optimum at 100 °C for 60 min, with performance declining at higher severities, while comprehensive reviews emphasize that mild to moderate hydrothermal conditions (≤100 °C, ≤120 min) generally favor VFA accumulation and biogas enhancement without excessive inhibitor formation (Lukitawesa et al., 2019).

Mechanistically, hot water bath pretreatment exposes biomass to moist heat, which enhances heat transfer into particle interiors and promotes cell wall swelling, hemicellulose solubilization, and partial depolymerization of lignin–carbohydrate complexes. However, moist heat also facilitates volatilization and stripping of low molecular weight VFAs, such as acetic, propionic, butyric, and valeric acids, particularly at higher temperatures or prolonged exposure times. This phenomenon likely explains the observed reductions in VFA and sCOD at 100 °C and beyond 90 min (Gil et al., 2018). As these VFAs serve as key intermediates for acetogenesis and methanogenesis, their loss or degradation during pretreatment may negatively affect downstream biogas yields if process severity is not carefully controlled. Overall, pretreatment at 90 °C for 90 min represents a balance between effective structural disruption and minimal VFA loss, positioning hot water bath pretreatment as a moderately effective, low technology option for enhancing P. hysterophorus digestibility, albeit less impactful than optimized hot air oven pretreatment in terms of absolute solubilization (Banu et al., 2021).

3.2. Biomass Characterization

The lignocellulosic composition of

Partheniumhysterophorus biomass was analyzed before and after thermal pretreatment to elucidate structural modifications relevant to anaerobic digestion performance (

Table 2). Across all four pretreatment methods, acid soluble lignin content increased relative to the untreated biomass (2.12%), indicating partial depolymerization and solubilization of the lignin matrix. The highest acid soluble lignin content was observed for hot air oven pretreatment (3.62%), followed by autoclaving (2.58%), hot water bath (2.54%), and microwave irradiation (1.89%). Elevated soluble lignin fractions suggest enhanced lignin breakdown, which facilitates the release of soluble organics and improves microbial accessibility during hydrolysis and subsequent biogas production (Banu et al., 2021).

In contrast, acid insoluble lignin exhibited an overall decreasing trend compared with the untreated biomass (5.93%), particularly following microwave (4.33%), hot air oven (4.67%), and autoclave (5.35%) pretreatments. This reduction reflects disruption of recalcitrant lignin carbohydrate complexes and cleavage of ether and ester linkages between lignin and hemicellulose, thereby decreasing structural rigidity and enhancing enzymatic accessibility (Kamdem et al., 2015). Such depolymerization is widely recognized as a key mechanism through which thermal pretreatments improve the digestibility of lignocellulosic substrates (Kumar et al., 2009a). The slight increase or marginal change in acid insoluble lignin observed for hot water bath pretreatment (6.05%) may be attributed to lignin condensation or redistribution phenomena, whereby portions of lignin become more condensed while overall biomass solubilization and biodegradability still improve (Banu et al., 2021).

Cellulose content increased from 42.84% in the untreated biomass to 46.58% following hot air oven pretreatment, 44.34% after microwave irradiation, and 43.16% after hot water bath treatment, while remaining nearly unchanged under autoclaving (42.93%). This apparent cellulose enrichment does not indicate de novo cellulose formation but instead reflects a relative increase resulting from preferential removal or solubilization of hemicellulose and lignin, along with fragmentation of long cellulose chains into shorter, more reactive segments (Kumar et al., 2009a). Concurrently, hemicellulose content decreased from 29.1% in the untreated biomass to 20.8% (hot air oven), 22.3% (hot water bath), and 25.2% (microwave), with only a modest reduction observed under autoclave pretreatment (27.8%). These results indicate preferential solubilization of the more labile hemicellulosic fraction during thermal processing. Among the evaluated methods, hot air oven pretreatment produced the greatest reduction in hemicellulose and the most pronounced increases in cellulose and soluble lignin, corroborating its superior ability to open the lignocellulosic structure compared with the other thermal techniques (Karthikeyan et al., 2026).

Overall, these compositional changes namely increased acid soluble lignin; reduced acidinsoluble lignin, relative cellulose enrichment, and hemicellulose depletion are consistent with effective thermal deconstruction of lignocellulosic biomass. Such modifications align well with previous reports demonstrating strong correlations between lignocellulosic compositional shifts, enhanced enzymatic hydrolysis, increased sCOD release, and improved methane yields under optimally selected pretreatment conditions.

3.3. Spectroscopic Analysis

3.3.1. FESEM Analysis

FESEM revealed pronounced morphological differences between untreated and thermally pretreated Partheniumhysterophorus biomass. In the untreated samples, the lignocellulosic surface appeared compact, smooth, and structurally intact, indicative of a dense matrix in which cellulose microfibrils are tightly embedded within lignin and hemicellulose. This compact architecture restricts microbial attachment and enzymatic penetration during anaerobic digestion.

Following thermal pretreatment, the ordered surface morphology was progressively disrupted, as evidenced by visible cracking, peeling, and fragmentation of the biomass surface (

Figure 6a–e). Such structural alterations are widely associated with enhanced enzyme and microbial accessibility, leading to accelerated hydrolysis and shortened lag phases in anaerobic digestion of lignocellulosic substrates (Banu et al., 2021).

Among the evaluated pretreatment methods, hot air oven pretreatment induced the most extensive structural deconstruction, characterized by pronounced disintegration of the lignocellulosic matrix, exposure of internal fibrillar networks, and the formation of pores and fissures. These features significantly enhance cellulose accessibility to hydrolytic microorganisms. In contrast, microwave pretreated biomass retained relatively compact regions with only localized surface damage, suggesting incomplete disruption, which is consistent with the comparatively lower sCOD enhancement observed. Autoclave and hot water bath pretreatments produced intermediate morphological changes, including partial surface rupture and limited opening of the matrix, reflecting the milder severity of moist heat conditions at their respective optimized parameters.

Comparable FESEM observations namely the transition from smooth, dense surfaces to rough, porous, and fissured morphologies have been widely reported for thermally pretreated agricultural residues and invasive weed biomass. These morphological transformations are strongly correlated with increased solubilization, enhanced hydrolysis rates, and improved biogas yields under anaerobic digestion (Karthikeyan et al., 2026).

3.3.2. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

XRD analysis was employed to evaluate changes in the crystalline and amorphous fractions of

Partheniumhysterophorus cellulose induced by thermal pretreatment. In the untreated biomass, distinct and sharp diffraction peaks were observed at characteristic 2θ values corresponding to crystalline cellulose, indicating a high degree of structural order and tight fibril packing. Such an ordered structure generally limits enzymatic hydrolysis and microbial degradation. Following hot air oven pretreatment, these intense diffraction peaks were significantly attenuated and broadened (

Figure 7), indicating a reduction in cellulose crystallinity and a concomitant increase in the amorphous fraction, which is more readily accessible and degradable under anaerobic conditions.

The observed decrease in the crystallinity index supports the premise that thermal energy disrupts intermolecular hydrogen bonding and partially rearranges or collapses the crystalline lattice, thereby loosening the rigid lignocellulosic framework. Similar XRD patterns have been reported for thermally and chemically pretreated sugarcane bagasse and other lignocellulosic residues, where peak attenuation and broadening are associated with enhanced enzymatic digestibility and increased biogas or bioethanol yields (Chen et al., 2011). These findings confirm that thermal pretreatment particularly hot air oven treatment is effective in transforming highly ordered cellulose into a more amorphous and microbially accessible form, corroborating the FESEM observations and compositional evidence of improved substrate susceptibility (Baruah et al., 2018).

3.3.3. FTIR Analysis

FTIR spectroscopy was employed to identify chemical bond transformations within

Partheniumhysterophorus biomass before and after thermal pretreatment. The overlaid FTIR spectra exhibit distinct absorption features that reflect the extent of lignocellulosic deconstruction and the resulting enhancement in substrate accessibility for anaerobic digestion (

Figure 8).

Aromatic C–H and lignin associated vibrations (1600–1500 cm⁻¹): The untreated biomass displays prominent absorption bands characteristic of aromatic C=C stretching vibrations within the lignin macromolecule. Following hot air oven pretreatment, these peaks were markedly attenuated, indicating partial delignification and thermal cleavage of ether and ester linkages that crosslink lignin with carbohydrate polymers (Barua et al., 2017).

Carbonyl region (≈1700 cm⁻¹): A distinct absorption band corresponding to C=O stretching vibrations of carboxylic acids, esters, and ketones is evident in the untreated sample. The reduced intensity of this band after pretreatment suggests thermal degradation or removal of carbonyl containing components, accompanied by progressive opening of the lignocellulosic matrix (Li et al., 2010).

C–O and polysaccharide related vibrations (1050 cm⁻¹): Strong absorption in the untreated biomass arises from C–O and C–C stretching vibrations typical of cellulose and hemicellulose polysaccharides. After thermal pretreatment, the decreased intensity in this region indicates partial solubilization and depolymerization of hemicelluloses, thereby exposing internal cellulose fibrils and facilitating microbial colonization (Banu et al., 2021).

Broad O–H stretching band (3300 cm⁻¹): Both untreated and pretreated samples exhibit broad hydroxyl absorption bands; however, the pretreated biomass shows a more defined O–H profile. This change reflects the reorganization of hydrogen bonding networks and increased surface accessibility resulting from thermal disruption of the biomass structure (Lazzari et al., 2017).

Collectively, these spectroscopic changes attenuated lignin signals, reduced hemicellulose associated absorptions, and enhanced cellulose accessibility confirm thermal pretreatment as an effective strategy for structural reconfiguration and improved bioavailability. These findings complement the FESEM, XRD, and compositional analyses, providing a mechanistic basis for the enhanced anaerobic digestibility and biogas recovery from P. hysterophorus biomass.

3.3.4. Biomethane Production

Four thermal pretreatment strategies hot air oven, microwave irradiation, autoclaving, and hot water bath treatment were evaluated for their effects on biomethane production from Partheniumhysterophorus biomass. Among these methods, hot air oven pretreatment proved to be the most effective, resulting in a 51.56% increase in soluble sCOD and a 46.48% increase in VFA compared with the untreated substrate. These increases indicate substantial solubilization of fermentable organic matter and enhanced hydrolysis potential. Such improvements are consistent with previous studies demonstrating that appropriately controlled thermal severity disrupts the lignocellulosic matrix, increases soluble substrate availability, and ultimately enhances biogas yields during anaerobic digestion (Gurung et al., 2012).

Biochemical methane potential assays were conducted using four reactor configurations: untreated

P. hysterophorus (substrate only), hot air oven pretreated

P. hysterophorus, a cow dung only inoculum control, and a blank control for baseline gas correction. Owing to the high lignin content and dense structural matrix of the untreated biomass, hydrolysis occurred slowly, leading to an extended lag phase and lower overall substrate conversion. Consequently, cumulative biogas production from the untreated reactors reached only 3148 mL after 50 days of digestion (

Figure 6a) (Gurung et al., 2012). In contrast, reactors fed with hot air oven–pretreated biomass exhibited a substantially accelerated digestion profile, with cumulative biogas production rapidly increasing to 3723 mL within 35 days (Figure 9a,b). Biomethane production stabilized by approximately day 30, indicating both shortened hydrolysis duration and an enhanced ultimate methane potential. Comparable reductions in digestion time following moderate thermal pretreatment (90–120°C) have been reported for other lignocellulosicfeedstocks, where pretreatment improves degradation kinetics without promoting excessive formation of inhibitory by products (Wang et al., 1997).

The best performance of the hot air oven pretreated reactors can be attributed to the combined effects of lignin softening, hemicellulose solubilization, and partial amorphization of cellulose, which collectively enhance enzyme and microbial accessibility. These mechanistic insights are consistent with the compositional analysis and the FESEM, XRD, and FTIR results obtained in this study. Nevertheless, excessively severe thermal pretreatment is known to promote the formation of inhibitory compounds, such as furfural, hydroxymethylfurfural, and phenolic derivatives, which can suppress methanogenic activity and reduce biogas yields (Laser et al., 2002; Nizami et al., 2009). The optimized hot air oven conditions applied here appear to achieve a favorable balance between effective structural disruption and minimal inhibitor generation, thereby maximizing net biomethane recovery from P. hysterophorus while avoiding the drawbacks associated with over pretreatment.

4. Energy Assessment

An energy analysis of the hot air oven pretreatment was conducted by comparing the specific electrical energy consumed during thermal conditioning with the specific energy recovered as biomethane. Based on the oven power rating, an exposure duration of 90 min at 110°C, and a volatile solids (VS) loading of approximately 7.9 g, the specific energy input was calculated to be 3.2 kJ g⁻¹ VS. This relatively low energy requirement reflects the moderate pretreatment temperature and batch scale operation and falls within the range reported for thermal conditioning of lignocellulosic substrates prior to anaerobic digestion (Passos et al., 2013).

The specific energy recovered from biomethane was estimated using the maximum daily methane yield obtained from the BMP assays and the lower heating value of methane (35.8 kJ L⁻¹). When normalized to the added VS, the corresponding specific energy output was 7.70 kJ g⁻¹ VS, which is more than twice the pretreatment energy input. This favorable energy balance demonstrates that the additional methane generated as a result of hot air oven pretreatment more than compensates for the electrical energy consumed during heating, thereby confirming the energetic feasibility of this approach for the valorization of P. hysterophorus biomass (Kuglarz et al., 2013; Zhang et al., 2021).

Comparable net energy gains have been reported for thermally pretreated food waste, sewage sludge, and agricultural residues, where optimized temperature time combinations yield energy ratios (output/input) greater than 2. These findings support the integration of mild thermal pretreatment strategies into full scale biogas production systems to enhance overall energy recovery efficiency (Kemke et al., 2013).

5. Conclusion

Thermal pretreatment of Partheniumhysterophorus was shown to be effective in shortening the hydrolysis phase while simultaneously enhancing biogas production under anaerobic digestion conditions. Across all four thermal strategies evaluated hot air oven, microwave irradiation, autoclaving, and hot water bath treatment a marked increase in soluble sCOD was observed, indicating improved solubilization of organic matter and enhanced substrate availability for microbial conversion. Among these approaches, hot air oven pretreatment at 110 °C for 90 min was identified as the optimal condition, achieving a 51.56% increase in solubilization relative to the untreated biomass and delivering the highest biomethane yield. Under these conditions, cumulative methane production reached 4239 ± 22 mL CH₄ g⁻¹ VS, compared with 3148 ± 19 mL CH₄ g⁻¹ VS for the untreated substrate, demonstrating a substantial improvement in conversion efficiency. These performance gains are consistent with the observed structural, compositional, and crystallinity modifications, which collectively indicate disruption of the lignocellulosic matrix, enhanced cellulose accessibility, and partial delignification. From a process design and sustainability perspective, the findings suggest that appropriately controlled thermal pretreatment can transform the invasive weed P. hysterophorus into a viable and energy efficient biogas feedstock, thereby contributing to both effective weed management and renewable energy generation. Further performance enhancements may be achievable through sequential or combined pretreatment strategies (e.g., thermal–alkali or staged thermal treatments); however, any such intensification must be carefully assessed in terms of additional energy requirements to ensure a positive net energy balance and long term process sustainability.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the National Science, Research and Innovation Fund (NSRF), King Mongkut’s University of Technology North Bangkok (Project No. KMUTNB-FF-69-B-03) for financially support of this work.

References

- APHA. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water & Wastewater; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Batish, D.R; Singh, H.P; Saxena, D.B; Kohli, R.K. Weed suppressing ability of parthenin – a sesquiterpene lactone from P.hysterophorushysterophorus. N. Z. Plant Prot. 2002, 55, 218–221. [Google Scholar]

- Belz, G.T. Stimulationversusinhibition—bioactivity of parthenin, a phytochemicalfrom P.hysterophorushysterophorus L. Dose Response 2008, 6, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, V.B; Kalamdhad, A.S. Water hyacinth to biogas: a review. Pollut. Res. 2016, 35, 491–501. [Google Scholar]

- Barua, V.B; Kalamdhad, S A. Effect of various type of pretreatment technique on hydrolysis, compositional analysis and characterization of Water Hyacinth. Biosourtechnol 2017, 227, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barua, V.B.; Kalamdhad, A.S. Biochemical Methane Potential Test of Untreated408 and Hot Air Oven Pretreated Water Hyacinth: A Comparative Study. J Clean Produc 2017, 166, 409 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.; Park, S.; Seon, J.; Yu, J.; Lee, T. Evaluation of thermal, ultrasonic and alkali pretreatments on mixed-microalgal biomass to enhance anaerobic methane production. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 143, 330–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciftci, D; Saldaña, M.D.A. Hydrolysis of sweet blue lupin hull using subcritical water technology. BioresourTechnol 2015, 194, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.H.; Tu, Y.J.; Sheen, H.K. Disruption of sugarcane bagasse lignocellulosic structure by means of dilute sulphuric acid pretreatment with microwave-assisted heating. Appl. Energy 2011, 88, 2726–2734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrère, H.; Dumas, C.; Battimelli, A.; Batstone, D.J.; Delgenès, J.P.; Steyer, J.P.; Ferrer, I. Pretreatment methods to improve sludge anaerobic degradability:areview. J. Hazard. Mater. 2010, 183, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DiLallo, R.; Albertson, O.E. Volatile acids by direct titration. Water Pollut.Control Fed. 1961, 33(4), 356–365. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, A.; Mahmood, T. Pretreatment technologies for advancing anaerobic digestion of pulp and paper bio-treatment residues. Water Res. 2007, 41, 4273–4286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil, A.; Siles, J.A.; Martin, M.A.; Chica, A.F.; Estevez-Pastor, S.; Toro- Baptista. Effect of microwave pretreatment on semi-continuous anaerobic digestion of sewage sludge. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goering, H.D.; Van, S.P.J. Forage Fibre Analysis; US Dept of Agriculture Research Service: Washington, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, A; Dubey, SK. Specific methanogenic activity test for anaerobic treatment of phenolic wastewater. Desalin Water Treat 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, A.T.W.M.; Zeeman, G. Pretreatments to enhance the digestibility of lignocellulosic biomass. Bioresour. Technol. 2009, 100, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junoh, H.; Palanisamy, K.; Yip, C.H.; Pua, F.L. Optimization of NaOH thermochemical pretreatment to enhance solubilisation of organic food waste by response surface methodology. Int. J. Chem. Mol. Nucl. Mater. Metall. Eng. 2015, 9, 1300–1306. [Google Scholar]

- Javaid, A; Riaz, T. P.hysterophorusL., an alien invasive weed threatening natural vegetation in Punjab, Pakistan. Pak. J. Bot. 2012, 44, 123–126. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R.; Mago, G.; Balan, V.; Wyman, C.E. Physical and chemical characterizations of corn stover and poplar solids resulting from leading pretreatment technologies. Bioresour. Technol. 2009b, 100(17), 3948–3962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohli, R.K; Batish, D.R; Singh, H.P; Dogra, K.S. Status, invasiveness and environmental threats of three tropical American invasive weeds (P.hysterophorushysterophorusL., Ageratum conyzoides L. Lantana camara L.) in India Biol. Invasions 2006, 8, 1501–1510. [Google Scholar]

- Kanchan, S.D. Allelopathic effects of P.hysterophorushysterophorus L.1.Exudation of inhibitors through roots. Plant Soil 1979, 34, 27–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kanchan, S.D. Growth inhibitors from P.hysterophorushysterophorus L. Curr. Sci. 1975, 44, 358–359. [Google Scholar]

- Kohli, R.K; Rani, D. Res. Bull. (Sci.)Pb. Univ. P.hysterophorushysterophorus L. A Review 1994, vol. 44, 105–149. [Google Scholar]

- Khaliq, A.; Hussain, S.; Matloob, A.; Wahid, A.; Aslam., F. Aqeous swine cress (Coronopusdidymus) extracts inhibit wheat germination and early seedling growth. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2013, 15, 743–748. [Google Scholar]

- Kaatze, U. Fundamentals of microwaves. Radiat. Phys. Chem. 1995, 45(4), 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamdem, I.; Jacquet, N.; Tiappi, F.M.; Hiligsmann, S.; Vanderghem, C.; Richel, A.; Jacques, P.; Thonart, P. Comparative biochemical analysis after steam pretreatment of lignocellulosic agricultural waste biomass from Williams Cavendish banana plant (TriploidMusaAAA group). Waste Manage. Res. 2015, 33(11), 1022–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Barrett, D.M.; Delwiche, M.J.; Stroeve, P. Methods for pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass for efficient hydrolysis and biofuel prod. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2009a, 48(8), 3713–3729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y; Khanal, S.K. Bioenergy: Principles and Applications; John Wiley & Sons, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Henriksson, G.; Gellerstedt, G. Lignin depolymerization/ repolymerization and its critical role for delignification of aspen wood by steam explosion. Bioresour.Technol 2007, 98, 3061–3068. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Knierim, B.; Manisseri, C.; Arora, R.; Scheller, H.V.; Auer, M.; Vogel, K.P.; Simmons, B.A.; Singh, S. Comparison of dilute acid and ionic liquid pretreatment of switchgrass: biomass recalcitrance, delignification andenzymaticsaccharification. Bioresour. Technol. 2010, 101(13), 4900–4906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, R.; Cheng, J.; Song, W.; Ding, L.; Xie, B.; Zhou, J.; Cen, K. Characterisation of water hyacinth with microwave-heated alkali pretreatment for enhanced enzymatic digestibility and hydrogen/methane fermentation. Bioresour.Technol 2015, 182, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lay, J.; Li, Y.; Noike, T. Effect of moisture content and chemical nature on methane fermentation characteristics of municipal solid wastes. J. Environ. Syst. Eng. 1996, 552, 101e108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzari, E.; Schena, T.; Marcelo, M.C.A.; Primaz, T.C.; Silva, N.A.; Ferrão, F.M.; Bjerk, T.; Caramão, B.E. Classification of biomass through their pyrolytic bio-oil composition using FTIR and PCAanalysis. Industrial CropsandProducts 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.; Chantrasakdakul, P.; Kim, D.; Kim, H.S.; Park, K.Y. Evaluation of methane production and biomass degradation in anaerobic co-digestion of organic residuals. Int. J. Biol. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2013, 2(3), 2277e4394. [Google Scholar]

- Menardo, S.; Airoldi, G.; Balsari, P. The effect of particle size and thermal pretreatment on the methane yield of four agricultural by-products. Bioresour.Technol 2012, 104, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menardo, S.; Airoldi, G.; Balsari, P. The effect of particle size and thermal pretreatment on the methane yield of four agricultural by-products. Bioresour.Technol 2012, 104, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, H.B.; Mladenovska, Z.; Westermann, P.; Ahring, B.K. Comparison of two-stage thermophilic (68 C/55 C) anaerobic digestion with one-stage thermophilic (55 C) digestion of cattle manure. Biotechnol.Bioeng 2004, 86, 291–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrol, N.; González, L.; Reigosa, M.J. Allelopathy and abiotic stress. In Allelopathy; Springer: Netherlands, 2006; pp. 171–209. [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, D.K. Inhibition of salvinia (Salviniamolesta Mitchell) by P.hysterophorus (P.hysterophorushysterophorus L.) II. Relative effect of flower, leaf, stems, and root residue on salvinia and paddy. J. Chem. Ecol. 1994, 20, 3123–3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qasem, J.R; Foy, C.L. Weed allelopathy, its ecological impacts and future prospects. J. Crop Prod. 2001, 4, 43–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridenour, W.M; Callaway, RM. The relative importance of allelopathy in interference: the effects of an invasive weed on a native bunchgrass. Oecologia 2001, 126, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafique, R.; Poulsen, T.G.; Nizami, A.S.; Asam, Z.Z.; Murphy, J.D.; Kiely, G. Effect of thermal, chemical and thermo-chemical pre-treatments to enhance methane production. Energy 2010, 35, 4556–4561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.P.; Batish, D.R; Pandher, J.K; Kohli, R.K. Phytotoxic effects of P.hysterophorushysterophorus residues on three Brassica species. Weed Biol. Manag. 2005, 5, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.P; Batish, D.R; Pandher, J.K; Kohli, R.K. Assessment of allelopathic properties of P.hysterophorushysterophorus residues. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2003, 95, 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapci, Z. The effect of microwave pretreatment on biogas production from agricultural straws. Bioresour. Technol. 2013, 128, 487–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toquero, C.; Bolado, S. Effect of four pretreatments on enzymatic hydrolysis and ethanol fermentation of wheat straw. Influence of inhibitors and washing. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 157, 68–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thi, B.T.N.; Thanh, L.H.V.; Lan, T.N.P.; Thuy, N.T.D.; Ju, Y.H. Comparison of some pretreatment methods on celluloserecovery from water hyacinth (EichhorniaCrassipes). J. Clean Energy Technol. 2017, 5, 274–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesner, M; Tessema, T; Hoffmann, A; Wilfried, P; Buettner, C; Mewis; Ulrichs, I.C. Impact of the Pan-tropical Weed P.hysterophorushysterophorus L. On Human Health in Ethiopia; Institute of Horticultural Science, Urban Horticulture, Berlin, Germany, 2007; pp. 9pp. 729–730. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Noguchi, C.; Hara, Y.; Sharon, C.; Kakimoto, K.; Kato, Y. Studies on anaerobic digestion mechanism: influence of pretreatment temperature on biodegradation of waste activated sludge. Environ. Technol. 1997, 18, 999–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Zhang, X.; Wan, J.; Ma, F.; Tang, Y.; Zhang, X. Production of fibreboardusing corn stalk pretreated with white-rot fungusTrameteshirsuteby hot pressing without adhesive. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 11258–11261. [Google Scholar]

- Gurung, A.; Van Ginkel, S.W.; Kang, W.C.; Qambrani, N.A.; Oha, S.E. Evaluation of marine biomass as a source of methane in batch tests: a lab-scale study. Energy 2012, 43, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Noguchi, C.; Hara, Y.; Sharon, C.; Kakimoto, K.; Kato, Y. Studies on anaerobic digestion mechanism: influence of pretreatment temperature on biodegradation of waste activated sludge. Environ. Technol. 1997, 18, 999–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laser, M.; Schulman, D.; Allen, S.G.; Lichwa, J.; Antal, M.J., Jr.; Lynd, L.R. A comparison of liquid hot water and steam pretreatments of sugar cane bagasse for bioconversion to ethanol. Bioresour. Technol. 2002, 81, 33–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizami, A.S.; Korres, N.E.; Murphy, J.D. A review of the integrated process for the production of grass biomethane. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 54 43, 8496–8508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathyan, A.; Koley, S.; Khwairakpam, M.; Kalamdhad, A. S. Effect of thermal pretreatments on biogas production and methane yield from anaerobic digestion of aquatic weed biomass Hydrillaverticillata. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2023, 13(17), 16273–16284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Khanna, S.; Moholkar, V. S.; Goyal, A. Screening and optimization of pretreatments for Partheniumhysterophorus as feedstock for alcoholic biofuels. Applied energy 2014, 129, 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthikeyan, P. K.; Bandulasena, H. C. H.; Radu, T. A comparative analysis of pre-treatment technologies for enhanced biogas production from anaerobic digestion of lignocellulosic waste. Industrial Crops and Products 2024, 215, 118591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wang, J.; Peng, H.; Li, Q.; Wang, M.; Yan, W.; Zhang, H. The effect of heat pre-treatment on the anaerobic digestion of high-solid pig manure under high organic loading level. Froniers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2022, 10, 972361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banu J, R.; Sugitha, S.; Kavitha, S.; Kannah R, Y.; Merrylin, J.; Kumar, G.; Lukitawesa; Patinvoh, R. J.; Millati, R.; Sarvari-Horvath, I.; Taherzadeh, M. J.; Lignocellulosic biomass pretreatment for enhanced bioenergy recovery: effect of lignocelluloses 59. Factors influencing volatile fatty acids production from food wastes via anaerobic digestion ecalcitrance and enhancement strategies. Bioengineered;Frontiers in Energy Research 2021, 11((1) 9), 39–52 646057. [Google Scholar]

- Karthikeyan, P. K.; Iza, F.; Bandulasena, H. C. H.; Radu, T. Enhanced biogas production from lignocellulosic biomass via integrated Fenton and plasma treatment. Biomass and Bioenergy 2026, 208, 108812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baruah, J.; Nath, B. K.; Sharma, R.; Kumar, S.; Deka, R. C.; Baruah, D. C.; Kalita, E. Recent trends in the pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass for value-added products. Frontiers in Energy Research 2018, 6, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Cao, H.; Liang, Y. Optimization of thermal pretreatment of food waste for maximal solubilization. Journal of Environmental Engineering 2021, 147(4), 04021010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemka, U. N.; Ogbulie, T. E.; Oguzie, K.; Akalezi, C. O.; Oguzie, E. E. Pretreatment procedures on lignocellulosic biomass material for biogas production: a review. Annals of Oradea University, Biology Fascicle/AnaleleUniversităţii din Oradea, FasciculaBiologie 2023, 30(2). [Google Scholar]

- Bolado-Rodríguez, S.; Toquero, C.; Martín-Juárez, J.; Travaini, R.; García-Encina, P.A. Effect of thermal, acid, alkaline and alkaline-peroxide pretreatments on the biochemical methane potential and kinetics of the anaerobic digestion of wheat straw and sugarcane bagasse. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 201, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |