Submitted:

17 January 2026

Posted:

19 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Who remains resilient over time, compared with individuals who experience persistently elevated depressive symptoms or persistently lower QoL, thereby capturing differences in long-term outcome levels.

- Who is at risk for persistently poor depression or QoL outcomes, providing insight into profiles associated with sustained vulnerability.

- Who deteriorates despite early resilience, a contrast that is less confounded by baseline outcome levels and enables the identification of early warning markers relevant to preventive strategies, clinical monitoring and early intervention.

- Who recovers among individuals with comparable baseline levels, a comparison that is likewise less influenced by baseline outcome levels and highlights factors associated with improvement rather than symptom burden, with potential implications for therapeutic intervention.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Outcome Variables

2.2.2. Sociodemographic, Lifestyle and Clinical Data

2.2.3. Psychological Scales

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.3.1. Missing Data

2.3.2. Derivation of Mental Health and GHS/QoL Trajectories

2.3.3. Determinants of Mental Health and GHS/QoL Trajectories

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

| Variable | n (%) | Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Life Events | Estrogen receptor Positivity | 467 (89.6%) | |

| None | 58 (12%) | Progesterone receptor Positivity | 410 (79.8%) |

| One event | 239 (49.6%) | HER2 Positivity | 89 (18.2%) |

| Two or more events | 185 (38.4%) | Ki67 levels ≥20% | 293 (56.7%) |

| Chronic diseases | 191 (35.7%) | Subtypes1 | |

| Metabolic diseases | Luminal A-like | 175 (36.9%) | |

| Mental illness | Luminal B-like (HER2 -) | 185 (39%) | |

| Family history of beast cancer | 330 (64.3%) | Luminal B-like (HER2 +) | 68 (14.3%) |

| Menopausal status pre | Her2-positive (non luminal) | 20 (4.2%) | |

| Pre/Peri-menopausal | 202 (38.5%) | Triple-negative | 26 (5.5%) |

| Postmenopausal | 322 (61.5%) | Lumpectomy | 391 (74.6%) |

| HRT before diagnosis | 105 (21.6%) | Mastectomy | 133 (25.4%) |

| Cancer stage | Radiotherapy | 424 (80.6%) | |

| I | 251 (48.2%) | Systemic Therapy | |

| II | 223 (42.8%) | Chemotherapy only (± anti-HER2) | 78 (14.9%) |

| III | 47 (9%) | Endocrine therapy only | 247 (47.3%) |

| Cancer grade | Chemo + Endocrine therapy (± anti-HER2) | 197 (37.7%) | |

| I | 91 (17.5%) | Anti-HER2 therapy | 82 (15.4%) |

| II | 271 (52.2%) | Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy | 84 (16%) |

| III | 157 (30.3%) | ||

| Cancer histological type | |||

| Ductal | 408 (77.9%) | ||

| Lobular | 80 (15.3%) | ||

| Other | 36 (6.9%) |

3.2. Trajectory Groups

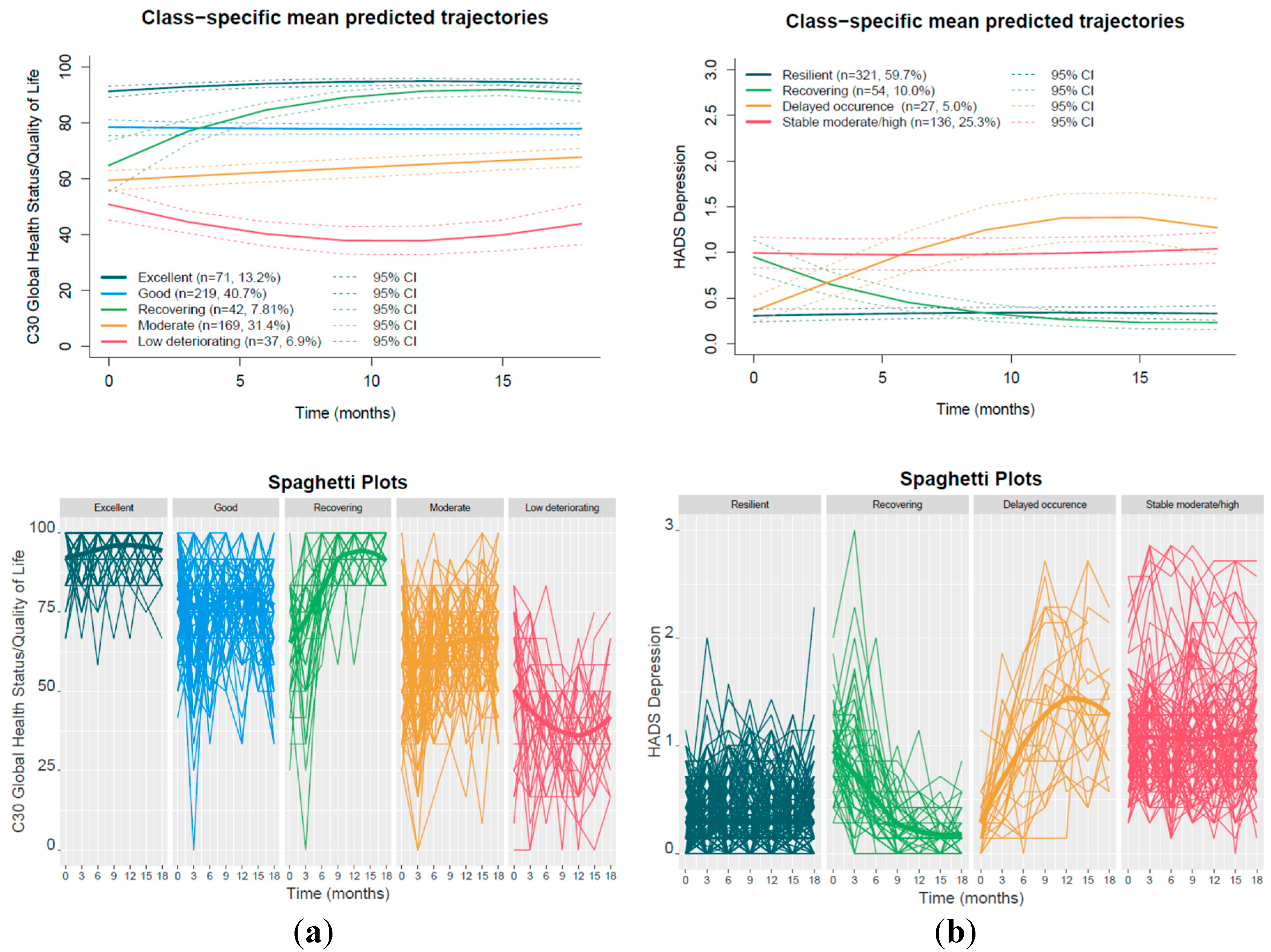

3.2.1. GHS/QoL Trajectories

3.2.2. HADS Depression Trajectories

3.3. Predictors of C30 GHS/QoL Trajectories

3.3.1. Low Deteriorating QoL vs Rest

3.3.2. Excellent QoL vs Rest

3.3.3. Recovery vs Moderate QoL

3.4. Predictors of HADS Depression Trajectories

3.4.1. Stable Moderate/High vs Resilient

3.4.2. Delayed occurrence vs Resilient

3.4.3. Recovery vs Stable Moderate/High

4. Discussion

4.1. Strengths and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BR23 | BReast cancer–specific module of EORTC QLQ |

| CBI-B | Cancer Behavior Inventory |

| CD-RISC | Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 | European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire - Core 30 |

| FCR-SF | Fear of Cancer Recurrence Scale–Short Form |

| GHS/QoL | Global Health Status/ QoL scale of EORTC-QLQ-C30 |

| HADS | Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale |

| LOT | Life Orientation Test |

| MAAS | Mindful Attention Awareness Scale |

| MAC | Mental Adjustment to Cancer Scale |

| MOS | Medical Outcomes Study |

| PACT | Perceived Ability to Cope with Trauma Scale |

| PANAS | Positive and Negative Affect Schedule |

| PTGI-SF | Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory–Short Form |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| SOC | Sense of Coherence Scale |

Appendix A

| Transformation - link function | AIC | BIC |

|---|---|---|

| None | 30481.32 | 30498.47 |

| Beta cumulative distribution | 29468.93 | 29494.65 |

| I-splines with 5 equidistant knots | 30001.87 | 30040.46 |

| I-splines with 5 knots at quantiles | 29889.07 | 29927.66 |

| I-splines with 6 equidistant knots | 29997.34 | 30040.21 |

| I-splines with 6 knots at quantiles | 29412.77 | 29455.64 |

| I-splines with 7 equidistant knots | 29955.92 | 30003.08 |

| I-splines with 7 knots at quantiles | 29411 | 29458.16 |

| Transformation - link function | AIC | BIC |

|---|---|---|

| None | 28905.96 | 28948.84 |

| Beta cumulative distribution | 27780.27 | 27831.73 |

| I-splines with 5 equidistant knots | 28306.42 | 28370.74 |

| I-splines with 5 knots at quantiles | 28193.4 | 28257.72 |

| I-splines with 6 equidistant knots | 28300.39 | 28369 |

| I-splines with 6 knots at quantiles | 27722.3 | 27790.9 |

| I-splines with 7 equidistant knots | 28258.61 | 28331.5 |

| I-splines with 7 knots at quantiles | 27719.66 | 27792.55 |

| Transformation - link function | AIC | BIC |

|---|---|---|

| None | 5384.34 | 5401.491 |

| Beta cumulative distribution | 3830.596 | 3856.323 |

| I-splines with 5 equidistant knots | 3459.454 | 3498.045 |

| I-splines with 5 knots at quantiles | 3344.796 | 3383.387 |

| I-splines with 6 equidistant knots | 3423.261 | 3466.14 |

| I-splines with 6 knots at quantiles | 3340.9 | 3383.778 |

| I-splines with 7 equidistant knots | 3398.965 | 3446.132 |

| I-splines with 7 knots at quantiles | 3339.337 | 3386.504 |

| Transformation - link function | AIC | BIC |

|---|---|---|

| None | 2688.547 | 2731.426 |

| Beta cumulative distribution | 1272.653 | 1324.107 |

| I-splines with 5 equidistant knots | 976.3214 | 1040.639 |

| I-splines with 5 knots at quantiles | 882.3571 | 946.675 |

| I-splines with 6 equidistant knots | 955.6132 | 1024.219 |

| I-splines with 6 knots at quantiles | 869.0842 | 940.7354 |

| I-splines with 7 equidistant knots | 941.1433 | 1014.037 |

| I-splines with 7 knots at quantiles | 869.0842 | 941.9778 |

Appendix B

| Relative class size (%) | |||||||||||||

| No of classes | loglik | AIC | BIC | entropy | ICL | class1 | class2 | class3 | class4 | class5 | class6 | class7 | class8 |

| 1 | -14696 | 29413 | 29456 | 1 | 29456 | 100 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2 | -14170 | 28368 | 28428 | 0.857 | 28481 | 32.16 | 67.84 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 3 | -13959 | 27955 | 28032 | 0.836 | 28129 | 19.89 | 52.79 | 27.32 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 4 | -13908 | 27861 | 27955 | 0.809 | 28098 | 16.36 | 29.55 | 6.32 | 47.77 | - | - | - | - |

| 5 | -13869 | 27789 | 27901 | 0.800 | 28074 | 13.20 | 40.71 | 7.81 | 31.41 | 6.88 | - | - | - |

| 6 | -13836 | 27732 | 27860 | 0.795 | 28058 | 10.22 | 12.27 | 7.06 | 41.64 | 23.42 | 5.39 | - | - |

| 7 | -13820 | 27708 | 27854 | 0.768 | 28097 | 10.04 | 11.52 | 35.50 | 6.51 | 23.05 | 8.36 | 5.02 | - |

| 8 | -13815 | 27706 | 27868 | 0.726 | 28175 | 9.85 | 11.71 | 35.13 | 8.55 | 10.41 | 6.51 | 12.45 | 5.39 |

| Note: AIC: Akaike Information Criterion; BIC: Bayesian Information Criterion; ICL: Integrated Complete Likelihood. | |||||||||||||

| Relative class size (%) | |||||||||||

| No of classes | loglik | AIC | BIC | entropy | ICL | class1 | class2 | class3 | class4 | class5 | class6 |

| 1 | -13845 | 27722 | 27791 | 1 | 27791 | 100 | NA | NA | NA | NA | |

| 2 | -13841 | 27722 | 27808 | 0.504 | 27993 | 22.68 | 77.32 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 3 | -13831 | 27710 | 27813 | 0.766 | 27951 | 7.99 | 19.14 | 72.86 | NA | NA | NA |

| 4 | -13825 | 27706 | 27826 | 0.713 | 28040 | 46.28 | 5.58 | 17.47 | 30.67 | NA | NA |

| 5 | -13819 | 27702 | 27839 | 0.759 | 28048 | 3.35 | 15.61 | 69.70 | 8.18 | 3.16 | NA |

| 6 | -13816 | 27704 | 27858 | 0.731 | 28118 | 17.47 | 44.61 | 1.12 | 28.81 | 5.95 | 2.04 |

| Note: AIC: Akaike Information Criterion; BIC: Bayesian Information Criterion; ICL: Integrated Complete Likelihood. | |||||||||||

| Assigned class |

Class 1 Excellent GHS/QoL |

Class 2 Good GHS/QoL |

Class 3 Recovering GHS/QoL |

Class 4 Moderate GHS/QoL |

Class 5 Low deteriorating GHS/QoL |

| 1 | 0.9222 | 0.0378 | 0.0400 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 |

| 2 | 0.0093 | 0.8547 | 0.0338 | 0.1022 | 0.0000 |

| 3 | 0.0657 | 0.1222 | 0.8002 | 0.0118 | 0.0000 |

| 4 | 0.0000 | 0.0944 | 0.0047 | 0.8636 | 0.0373 |

| 5 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0808 | 0.9192 |

Appendix C

| No of classes | loglik | AIC | BIC | entropy | ICL | %class1 | %class2 | %class3 | %class4 | %class5 | %class6 | %class7 | %class8 |

| 1 | -1660 | 3341 | 3384 | 1 | 3384 | 100 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 2 | -861 | 1750 | 1810 | 0.899 | 1848 | 47.21 | 52.79 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 3 | -631 | 1298 | 1375 | 0.873 | 1450 | 19.70 | 38.48 | 41.82 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 4 | -553 | 1149 | 1243 | 0.845 | 1359 | 16.54 | 33.64 | 37.92 | 11.90 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 5 | -497 | 1047 | 1158 | 0.851 | 1287 | 3.53 | 37.17 | 17.47 | 30.67 | 11.15 | NA | NA | NA |

| 6 | -455 | 971 | 1099 | 0.843 | 1251 | 3.53 | 17.47 | 6.88 | 28.81 | 30.67 | 12.64 | NA | NA |

| 7 | -434 | 936 | 1082 | 0.798 | 1293 | 3.53 | 22.12 | 7.62 | 15.99 | 16.36 | 10.78 | 23.61 | NA |

| 8 | -412 | 900 | 1063 | 0.809 | 1277 | 2.60 | 7.62 | 23.05 | 1.12 | 23.79 | 10.59 | 15.61 | 15.61 |

| Note: AIC: Akaike Information Criterion; BIC: Bayesian Information Criterion; ICL: Integrated Complete Likelihood. | |||||||||||||

| Relative class size (%) | |||||||||||

| No of classes | loglik | AIC | BIC | entropy | ICL | %class1 | %class2 | %class3 | %class4 | %class5 | %class6 |

| 1 | -420 | 872 | 941 | 1 | 941 | 100 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 2 | -410 | 860 | 946 | 0.586 | 1101 | 21.93 | 78.07 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 3 | -403 | 854 | 957 | 0.657 | 1159 | 2.60 | 23.79 | 73.61 | NA | NA | NA |

| 4 | -391 | 838 | 958 | 0.681 | 1196 | 10.04 | 5.02 | 59.67 | 25.28 | NA | NA |

| 5 | -383 | 829 | 966 | 0.732 | 1199 | 4.28 | 25.09 | 60.04 | 9.85 | 0.74 | NA |

| 6 | -373 | 819 | 973 | 0.772 | 1193 | 3.72 | 51.67 | 33.83 | 1.67 | 8.36 | 0.74 |

| Note: AIC: Akaike Information Criterion; BIC: Bayesian Information Criterion; ICL: Integrated Complete Likelihood. | |||||||||||

| Assigned class | Class 1 Recovery | Class 2 Delayed occurrence | Class 3 Resilient | Class 4 Stable Moderate/High |

| 1 | 0.7735 | 0.0000 | 0.1608 | 0.0657 |

| 2 | 0.0000 | 0.7899 | 0.1206 | 0.0895 |

| 3 | 0.0375 | 0.0090 | 0.8620 | 0.0914 |

| 4 | 0.0353 | 0.0348 | 0.1760 | 0.7540 |

Appendix D

|

Fixed effects in the class-membership model: (the class of reference is the last class) | ||||

| coefficient | SE | Wald | p-value | |

| intercept class 1 | 0.55548 | 0.28801 | 1.929 | 0.05378 |

| intercept class 2 | 1.65476 | 0.30204 | 5.479 | 0.00000 |

| intercept class 3 | 0.10195 | 0.35111 | 0.290 | 0.77153 |

| intercept class 4 | 1.44951 | 0.23372 | 6.202 | 0.00000 |

| Fixed effects in the longitudinal model: | ||||

| coefficient | SE | Wald | p-value | |

| intercept class1 (not estimated) | 0 | |||

| intercept class 2 | -1.34743 | 0.18936 | -7.116 | 0.00000 |

| intercept class 3 | -2.39865 | 0.28857 | -8.312 | 0.00000 |

| intercept class 4 | -2.74885 | 0.18200 | -15.103 | 0.00000 |

| intercept class 5 | -3.26800 | 0.21464 | -15.226 | 0.00000 |

| linear slope class 1 | 0.09053 | 0.03134 | 2.889 | 0.00386 |

| linear slope class 2 | -0.00849 | 0.02040 | -0.416 | 0.67729 |

| linear slope class 3 | 0.34277 | 0.06492 | 5.280 | 0.00000 |

| linear slope class 4 | 0.03283 | 0.02206 | 1.488 | 0.13668 |

| linear slope class 5 | -0.13893 | 0.04217 | -3.295 | 0.00099 |

| quadratic slope class 1 | -0.00378 | 0.00164 | -2.305 | 0.02117 |

| quadratic slope class 2 | 0.00033 | 0.00101 | 0.329 | 0.74253 |

| quadratic slope class 3 | -0.01185 | 0.00300 | -3.945 | 0.00008 |

| quadratic slope class 4 | -0.00008 | 0.00116 | -0.070 | 0.94426 |

| quadratic slope class 5 | 0.00651 | 0.00222 | 2.934 | 0.00335 |

| Parameters of the link function: | ||||

| coefficient | SE | Wald | p-value | |

| I-splines 1 | -5.95455 | 0.21304 | -27.950 | 0.00000 |

| I-splines 2 | 1.06674 | 0.09931 | 10.742 | 0.00000 |

| I-splines 3 | 0.91341 | 0.09308 | 9.813 | 0.00000 |

| I-splines 4 | 1.42070 | 0.03349 | 42.424 | 0.00000 |

| I-splines 5 | 0.86157 | 0.02925 | 29.451 | 0.00000 |

| I-splines 6 | -1.17587 | 0.02114 | -55.617 | 0.00000 |

| I-splines 7 | 0.00011 | 0.03728 | 0.003 | 0.99767 |

| I-splines 8 | -0.95530 | 0.02128 | -44.889 | 0.00000 |

|

Fixed effects in the class-membership model: (the class of reference is the last class) | ||||

| coefficient | SE | Wald | p-value | |

| intercept class 1 | -0.85515 | 0.34940 | -2.448 | 0.01438 |

| intercept class 2 | -1.56106 | 0.40570 | -3.848 | 0.00012 |

| intercept class 3 | 0.81867 | 0.29328 | 2.791 | 0.00525 |

| Fixed effects in the longitudinal model: | ||||

| coefficient | SE | Wald | p-value | |

| intercept class1 (not estimated) | 0 | |||

| intercept class 2 | -2.12840 | 0.43187 | -4.928 | 0.00000 |

| intercept class 3 | -2.40407 | 0.29120 | -8.256 | 0.00000 |

| intercept class 4 | 0.11938 | 0.33984 | 0.351 | 0.72537 |

| linear slope class 1 | -0.35787 | 0.05419 | -6.605 | 0.00000 |

| linear slope class 2 | 0.47814 | 0.07396 | 6.465 | 0.00000 |

| linear slope class 3 | 0.01588 | 0.02306 | 0.689 | 0.49109 |

| linear slope class 4 | -0.02495 | 0.03805 | -0.656 | 0.51200 |

| quadratic slope class 1 | 0.01082 | 0.00267 | 4.052 | 0.00005 |

| quadratic slope class 2 | -0.01737 | 0.00388 | -4.478 | 0.00001 |

| quadratic slope class 3 | -0.00075 | 0.00125 | -0.604 | 0.54560 |

| quadratic slope class 4 | 0.00171 | 0.00216 | 0.792 | 0.42858 |

| Variance-covariance matrix of the random-effects: | ||||

| intercept | linear slope | quadratic slope | ||

| intercept | 0.89100 | |||

| linear slope | 0.03042 | 0.00566 | ||

| quadratic slope | -0.00159 | -0.00025 | 1e-05 | |

| Parameters of the link function: | ||||

| coefficient | SE | Wald | p-value | |

| I-splines 1 | -4.61362 | 0.28054 | -16.446 | 0.00000 |

| I-splines 2 | 0.95180 | 0.02099 | 45.347 | 0.00000 |

| I-splines 3 | 0.79402 | 0.03608 | 22.006 | 0.00000 |

| I-splines 4 | 1.17562 | 0.02950 | 39.851 | 0.00000 |

| I-splines 5 | 0.93434 | 0.03303 | 28.292 | 0.00000 |

| I-splines 6 | 1.61728 | 0.04373 | 36.986 | 0.00000 |

| I-splines 7 | 1.24502 | 0.11248 | 11.069 | 0.00000 |

| I-splines 8 | 1.15337 | 0.13638 | 8.457 | 0.00000 |

References

- Pravettoni, G.; Gorini, A. A P5 cancer medicine approach: why personalized medicine cannot ignore psychology. Evaluation Clinical Practice 2011, 17, 594–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, G.A.; Galea, S.; Bucciarelli, A.; Vlahov, D. What predicts psychological resilience after disaster? The role of demographics, resources, and life stress. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007, 75, 671–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carver, C.S. Enhancing adaptation during treatment and the role of individual differences. Cancer 2005, 104, 2602–2607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, Y.; Yi, J.C.; Martinez-Gutierrez, J.; Reding, K.W.; Yi-Frazier, J.P.; Rosenberg, A.R. Resilience Among Patients Across the Cancer Continuum: Diverse Perspectives. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing 2014, 18, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garnefski, N.; Kraaij, V.; Spinhoven, P. Negative life events, cognitive emotion regulation and emotional problems. Personality and Individual Differences 2001, 30, 1311–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhu, X.; Yang, Y.; et al. Cognitive emotion regulation: characteristics and effect on quality of life in women with breast cancer. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2015, 13, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamama-Raz, Y.; Pat-Horenczyk, R.; Perry, S.; Ziv, Y.; Bar-Levav, R.; Stemmer, S.M. The Effectiveness of Group Intervention on Enhancing Cognitive Emotion Regulation Strategies in Breast Cancer Patients: A 2-Year Follow-up. Integr Cancer Ther. 2016, 15, 175–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolen-Hoeksema, S.; Aldao, A. Gender and age differences in emotion regulation strategies and their relationship to depressive symptoms. Personality and Individual Differences 2011, 51, 704–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yi, J.; He, J.; et al. Cognitive emotion regulation strategies as predictors of depressive symptoms in women newly diagnosed with breast cancer: Cognitive strategies predict depression in women with breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology 2014, 23, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzocco, K.; Masiero, M.; Carriero, M.C.; Pravettoni, G. The role of emotions in cancer patients’ decision-making. ecancer 2019, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorini, A.; Riva, S.; Marzorati, C.; Cropley, M.; Pravettoni, G. Rumination in breast and lung cancer patients: Preliminary data within an Italian sample. Psycho-Oncology 2018, 27, 703–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novakov, I.; Popovic-Petrovic, S. Personality traits as predictors of the affective state in patients after breast cancer surgery. Arch Oncol. 2017, 23, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exploring the Role of Self-Efficacy for Coping With Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review. Archives of Breast Cancer 2017, 42–57. [CrossRef]

- Wills, T.A.; Bantum, E.O. Social Support, Self-Regulation, and Resilience in Two Populations: General-Population Adolescents and Adult Cancer Survivors. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 2012, 31, 568–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolland, J.S. Cancer and the family: An integrative model. Cancer 2005, 104, 2584–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faccio, F.; Gandini, S.; Renzi, C.; Fioretti, C.; Crico, C.; Pravettoni, G. Development and validation of the Family Resilience (FaRE) Questionnaire: an observational study in Italy. BMJ Open. 2019, 9, e024670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faccio, F.; Renzi, C.; Giudice, A.V.; Pravettoni, G. Family Resilience in the Oncology Setting: Development of an Integrative Framework. Front Psychol. 2018, 9, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettini, G.; Sanchini, V.; Pat-Horenczyk, R.; et al. Predicting Effective Adaptation to Breast Cancer to Help Women BOUNCE Back: Protocol for a Multicenter Clinical Pilot Study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2022, 11, e34564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.J.; Meader, N.; Symonds, P. Diagnostic validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in cancer and palliative settings: A meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders 2010, 126, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Levis, B.; Sun, Y.; et al. Accuracy of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale Depression subscale (HADS-D) to screen for major depression: systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ 2021, n972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puhan, M.A.; Frey, M.; Büchi, S.; Schünemann, H.J. The minimal important difference of the hospital anxiety and depression scale in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008, 6, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaganian, L.; Bussmann, S.; Gerlach, A.L.; Kusch, M.; Labouvie, H.; Cwik, J.C. Critical consideration of assessment methods for clinically significant changes of mental distress after psycho-oncological interventions. Int J Methods Psych Res. 2020, 29, e1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, U.G.; Papalia, R.; De Salvatore, S.; et al. Establishing the Minimum Clinically Significant Difference (MCID) and the Patient Acceptable Symptom Score (PASS) for the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in Patients with Rotator Cuff Disease and Shoulder Prosthesis. JCM 2023, 12, 1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karsten, M.M.; Roehle, R.; Albers, S.; et al. Real-world reference scores for EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-BR23 in early breast cancer patients. European Journal of Cancer 2022, 163, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, J.; Bakshi, J.; Panda, N.K.; Sharma, M.; Vir, D.; Goyal, A.K. Cut-off points to classify numeric values of quality of life into normal, mild, moderate, and severe categories: an update for EORTC-QLQ-H&N35. Egypt J Otolaryngol. 2024, 40, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diouf, M.; Bonnetain, F.; Barbare, J.C.; et al. Optimal Cut Points for Quality of Life Questionnaire-Core 30 (QLQ-C30) Scales: Utility for Clinical Trials and Updates of Prognostic Systems in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma. The Oncologist 2015, 20, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, C.F.; Blackford, A.L.; Sussman, J.; et al. Identifying changes in scores on the EORTC-QLQ-C30 representing a change in patients’ supportive care needs. Qual Life Res. 2015, 24, 1207–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scheier, M.F.; Carver, C.S.; Bridges, M.W. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1994, 67, 1063–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antonovsky, A. The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Social Science & Medicine 1993, 36, 725–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, K.M.; Davidson, J.R.T. Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety 2003, 18, 76–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlson, L.E.; Brown, K.W. Validation of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale in a cancer population. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2005, 58, 29–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, G.A.; Pat-Horenczyk, R.; Noll, J. Coping flexibility and trauma: The Perceived Ability to Cope With Trauma (PACT) scale. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 2011, 3, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitzmann, C.A.; Merluzzi, T.V.; Jean-Pierre, P.; Roscoe, J.A.; Kirsh, K.L.; Passik, S.D. Assessing self-efficacy for coping with cancer: development and psychometric analysis of the brief version of the Cancer Behavior Inventory (CBI-B). Psycho-Oncology 2011, 20, 302–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simard, S.; Savard, J. Screening and comorbidity of clinical levels of fear of cancer recurrence. J Cancer Surviv. 2015, 9, 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, M.; Law, M.G.; Santos, M.D.; Greer, S.; Baruch, J.; Bliss, J. The Mini-MAC: Further Development of the Mental Adjustment to Cancer Scale. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology 1994, 12, 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cann, A.; Calhoun, L.G.; Tedeschi, R.G.; et al. A short form of the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory. Anxiety, Stress & Coping 2010, 23, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, D.; Clark, L.A.; Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1988, 54, 1063–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, A.; Stuck, A.E.; Silliman, R.A.; Ganz, P.A.; Clough-Gorr, K.M. The eight-item modified Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey: psychometric evaluation showed excellent performance. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 2012, 65, 1107–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buuren, S.V.; Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. mice : Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R. J Stat Soft 2011, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proust-Lima, C.; Philipps, V.; Liquet, B. Estimation of Extended Mixed Models Using Latent Classes and Latent Processes: The R Package lcmm. J Stat Soft 2017, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van De Schoot, R.; Sijbrandij, M.; Winter, S.D.; Depaoli, S.; Vermunt, J.K. The GRoLTS-Checklist: Guidelines for Reporting on Latent Trajectory Studies. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal 2017, 24, 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weller, B.E.; Bowen, N.K.; Faubert, S.J. Latent Class Analysis: A Guide to Best Practice. Journal of Black Psychology 2020, 46, 287–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Nest, G.; Lima Passos, V.; Candel, M.J.J.M.; Van Breukelen, G.J.P. An overview of mixture modelling for latent evolutions in longitudinal data: Modelling approaches, fit statistics and software. Advances in Life Course Research 2020, 43, 100323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, J.K.; Narasimhan, B.; Hastie, T. Elastic Net Regularization Paths for All Generalized Linear Models. J Stat Soft 2023, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Hastie, T. Regularization and Variable Selection Via the Elastic Net. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Statistical Methodology 2005, 67, 301–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T.; Tibshirani, R.; Friedman, J.H. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction, Second edition; Springer, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer, D.W.; Lemeshow, S.; Sturdivant, R.X. Applied Logistic Regression, 1st ed.; Wiley, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Jung, Y.S.; Kim, J.Y.; Bae, S.H. Trajectories of quality of life in breast cancer survivors during the first year after treatment: a longitudinal study. BMC Women’s Health 2023, 23, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Meglio, A.; Havas, J.; Gbenou, A.S.; et al. Dynamics of Long-Term Patient-Reported Quality of Life and Health Behaviors After Adjuvant Breast Cancer Chemotherapy. JCO 2022, 40, 3190–3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, N.G.; Levine, B.J.; Van Zee, K.J.; Naftalis, E.; Avis, N.E. Trajectories of quality of life following breast cancer diagnosis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018, 169, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charles, C.; Bardet, A.; Larive, A.; et al. Characterization of Depressive Symptoms Trajectories After Breast Cancer Diagnosis in Women in France. JAMA Netw Open. 2022, 5, e225118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kant, J.; Czisch, A.; Schott, S.; Siewerdt-Werner, D.; Birkenfeld, F.; Keller, M. Identifying and predicting distinct distress trajectories following a breast cancer diagnosis - from treatment into early survival. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2018, 115, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, Y.; et al. Group-based trajectory and predictors of anxiety and depression among Chinese breast cancer patients. Front Public Health 2022, 10, 1002341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karademas, E.C.; Mylona, E.; Mazzocco, K.; et al. Well-being trajectories in breast cancer and their predictors: A machine-learning approach. Psycho-Oncology 2023, 32, 1762–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genolini, C.; Ecochard, R.; Benghezal, M.; Driss, T.; Andrieu, S.; Subtil, F. kmlShape: An Efficient Method to Cluster Longitudinal Data (Time-Series) According to Their Shapes. PLoS One 2016, 11, e0150738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobl, C.; Boulesteix, A.L.; Zeileis, A.; Hothorn, T. Bias in random forest variable importance measures: Illustrations, sources and a solution. BMC Bioinformatics 2007, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Den Teuling, N.; Pauws, S.; Van Den Heuvel, E. latrend: A Framework for Clustering Longitudinal Data. The R Journal. 2025, 17, 108–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verboon, P.; Pat-El, R. Clustering longitudinal data using R: A Monte Carlo Study. Published online. 30 June 2022. [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Ahmadiankalati, M.; Tan, Z. Joint clustering multiple longitudinal features: A comparison of methods and software packages with practical guidance. Statistics in Medicine 2023, 42, 5513–5540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, D.P.; Von Oertzen, T. Growth Mixture Models Outperform Simpler Clustering Algorithms When Detecting Longitudinal Heterogeneity, Even With Small Sample Sizes. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2015, 22, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.E.; Kim, Y.E.; Kang, Y.S.; Choi, D.H.; Ahn, S.H.; An, J. SMOTE-augmented machine learning model predicts recurrent and metastatic breast cancer from microbiome analysis. Sci Rep. 2025, 15, 33096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.; Le, U.; Shi, Y. An effective up-sampling approach for breast cancer prediction with imbalanced data: A machine learning model-based comparative analysis. In PLoS ONE; E S, V, Ed.; 2022; Volume 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudin, C. Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead. Nat Mach Intell. 2019, 1, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarica, A.; Aracri, F.; Bianco, M.G.; et al. Explainability of random survival forests in predicting conversion risk from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Inf. 2023, 10, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelopoulos, A.N.; Bates, S. Conformal Prediction: A Gentle Introduction. Foundations and Trends in Machine Learning 2023, 16, 494–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alnemer, L.M.; Rajab, L.; Aljarah, I. Conformal Prediction Technique to Predict Breast Cancer Survivability. IJAST 2016, 96, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreenivasan, A.P.; Vaivade, A.; Noui, Y.; et al. Conformal prediction enables disease course prediction and allows individualized diagnostic uncertainty in multiple sclerosis. npj Digit Med. 2025, 8, 224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Mean (range) | Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 55.4 (40-70) | Monthly Income 1 | |

| BMI | 26 (17.3-54.1) | Low | 103 (20.2%) |

| Variable | n (%) | Middle | 315 (61.6%) |

| Country/Clinical site | High | 93 (18.2%) | |

| Portugal | 134 (24.9%) | Exercise level2 | |

| Italy | 95 (17.7%) | None | 166 (33.7%) |

| Finland | 205 (38.1%) | Low/moderate | 179 (36.4%) |

| Israel | 104 (19.3%) | Heavy | 147 (29.9%) |

| Education | Diet | ||

| Non University | 211 (39.3%) | No diet | 293 (54.6%) |

| University | 326 (60.7%) | Mediterranean/Vegetarian type | 166 (30.9%) |

| Marital status | Special | 78 (14.5%) | |

| Single/Engaged | 53 (9.9%) | Alcohol behavior3 | |

| Married/Common in Law | 400 (74.9%) | No Consumption | 107 (22.1%) |

| Divorced/Widowed | 81 (15.2%) | Consumption in Moderation | 331 (68.2%) |

| Employment status | Heavy Consumption | 47 (9.7%) | |

| Full/part- time/Self-employed | 390 (72.9%) | Smoking behavior | |

| Unemployed/Housewife | 47 (8.8%) | Current smoker | 72 (13.5%) |

| Retired | 98 (18.3%) | Never smoker | 359 (67.4%) |

| Former smoker | 102 (19.1%) |

| Variable | Selection Freq (%) Penalized Site |

Mean OR1 Penalized Site |

Selection Freq (%) Unpenalized Site |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| Performance2: log-loss = 0.191, Brier score = 0.052, ROC-AUC = 0.855 | |||

| Depression HADS | 100% | 1.4081 | 100% |

| Diarrhea C30 | 100% | 1.004 | 100% |

| Emotional functioning C30 | 100% | 0.9976 | 100% |

| Fatigue C30 | 100% | 1.0011 | 100% |

| GHS/QoL C30 | 100% | 0.9857 | 100% |

| Coping with cancer CBI | 100% | 0.9623 | 97% |

| Manageability SOC | 100% | 0.9548 | 100% |

| Other blame CERQ | 100% | 1.2173 | 100% |

| Pain C30 | 100% | 1.0154 | 100% |

| Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy | 100% | 1.4209 | 83% |

| Perceived support 1 item | 100% | 0.8896 | 100% |

| Triple−negative | 83% | 1.429 | 60% |

| Negative Life Events: Two or more (ref. No) | 67% | 1.0899 | 57% |

| Month 33 | |||

| Performance2: log-loss = 0.196, Brier score = 0.0537, ROC-AUC = 0.855 | |||

| Cognitive Function C30 | 100% | 0.9924 | 100% |

| Depression HADS | 100% | 1.8171 | 100% |

| Physical Function C30 | 100% | 0.9875 | 100% |

| Treatment control beliefs | 100% | 0.9005 | 100% |

| Anxiety HADS | 90% | 1.1226 | 87% |

| Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy | 73% | 1.1347 | 27% |

| Communication and cohesion FARE | 70% | 0.9455 | 73% |

| Variable | Selection Freq (%) Penalized Site |

Mean OR1 Penalized Site |

Selection Freq (%) Unpenalized Site |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| Performance2: log-loss = 0.276, Brier score = 0.0852, ROC-AUC = 0.879 | |||

| Anxiety HADS | 100% | 0.8796 | 93% |

| Cognitive functioning C30 | 100% | 1.0059 | 100% |

| Constipation C30 | 100% | 0.998 | 100% |

| Emotional functioning C30 | 100% | 1.0068 | 100% |

| Mental illness (ref. No) | 100% | 0.8947 | 10% |

| Fatigue C30 | 100% | 0.9955 | 100% |

| GHS/QoL C30 | 100% | 1.0501 | 100% |

| Mindfulness MAAS | 100% | 1.224 | 100% |

| Resilience CDRISC | 100% | 1.2044 | 100% |

| Self blame CERQ | 100% | 0.8493 | 100% |

| Physical functioning C30 | 100% | 1.0106 | 100% |

| Role functioning | 100% | 1.0029 | 100% |

| Luminal A-like | 100% | 1.3491 | 100% |

| Israel (ref.Portugal) | 100% | 1.1341 | - |

| Endocrine only (ref. Chemo only +/−Anti−HER2) | 100% | 1.107 | 63% |

| Mediterranean/Vegetarian diet (ref. None) | 100% | 0.9513 | 70% |

| Unemployed/Housewife (ref. Full/part− time/Self−employed) | 100% | 0.9384 | 100% |

| Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy | 100% | 0.7816 | 100% |

| Perceived support 1 item | 100% | 1.0287 | 97% |

| Future Perspective Image BR23 | 97% | 1.0014 | 97% |

| Meaningfulness SOC | 93% | 1.0026 | 80% |

| Positive affect PANAS | 93% | 1.014 | 0% |

| General self−efficacy 1 item | 93% | 1.0907 | 90% |

| Arm Symptoms BR23 | 90% | 0.9991 | 100% |

| Distress thermometer NCCN | 90% | 0.9624 | 90% |

| Coping with cancer CBI | 87% | 1.0278 | 100% |

| Luminal B-like (HER2 +) | 83% | 0.9583 | 63% |

| Catastrophizing CERQ | 80% | 0.9764 | 97% |

| Negative Life Events: Two or more (ref. No) | 77% | 0.9199 | 77% |

| Month 33 | |||

| Performance2: log-loss = 0.306, Brier score = 0.0928, ROC-AUC = 0.845 | |||

| Anxiety HADS | 100% | 0.744 | 100% |

| Fatigue C30 | 100% | 0.988 | 100% |

| Anxious preoccupation MAC | 100% | 0.8719 | 100% |

| Positive affect PANAS | 100% | 1.3538 | 100% |

| Role functioning | 100% | 1.0055 | 100% |

| Systemic Therapy Side Effects BR23 | 100% | 0.9963 | 100% |

| Social functioning | 100% | 1.004 | 100% |

| Personal control beliefs over illness | 100% | 1.0147 | 80% |

| Distress thermometer NCCN | 100% | 0.9693 | 97% |

| What done to cope: Talked to the physician | 100% | 0.9495 | 97% |

| Future Perspective Image BR23 | 97% | 1.0027 | 97% |

| Depression HADS | 93% | 0.8901 | 80% |

| Negative affect PANAS | 93% | 0.9418 | 13% |

| Physical functioning C30 | 93% | 1.003 | 97% |

| Perceived support 1 item | 93% | 1.0361 | 90% |

| Arm Symptoms BR23 | 90% | 0.9974 | 90% |

| Emotional functioning C30 | 83% | 1.003 | 87% |

| Communication and cohesion FARE | 77% | 1.0215 | 83% |

| Pain C30 | 77% | 0.9962 | 83% |

| Emotional support mMOS | 73% | 1.0395 | 67% |

| Negative Life Events: Two or more (ref. No) | 70% | 0.916 | 83% |

| Variable | Selection Freq (%) Penalized Site |

Mean OR1 Penalized Site |

Selection Freq (%) Unpenalized Site |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| Performance2: log-loss = 0.464, Brier score = 0.147, ROC-AUC = 0.681 | |||

| Coping with cancer CBI | 100% | 1.0568 | 97% |

| Mindfulness MAAS | 100% | 1.0276 | 93% |

| Optimism LOT | 100% | 1.1892 | 100% |

| Perspective CERQ | 100% | 1.0756 | 90% |

| Resilience CDRISC | 100% | 1.0604 | 0% |

| Pain C30 | 100% | 0.9978 | 100% |

| Positive affect PANAS | 100% | 1.0919 | 100% |

| Sexual functioning BR23 | 100% | 1.0033 | 90% |

| Social functioning C30 | 100% | 1.0047 | 100% |

| Income Middle (ref. Low) | 100% | 0.7621 | 97% |

| Income High (ref. Low) | 100% | 1.5861 | 100% |

| Postmenopausal | 93% | 1.0937 | 17% |

| Planning CERQ | 90% | 1.0193 | 70% |

| Negative Life Events: Two or more (ref. No) | 80% | 0.9259 | 77% |

| Special diet (ref. None) | 63% | 0.9428 | 37% |

| Month 33 | |||

| Performance2: log-loss = 0.432, Brier score = 0.136, ROC-AUC = 0.763 | |||

| Helpless MAC | 100% | 0.7512 | 100% |

| Pain C30 | 100% | 0.9945 | 100% |

| Positive affect PANAS | 100% | 1.1766 | 100% |

| Sexual functioning BR23 | 100% | 1.0065 | 100% |

| Non Luminal (HER2 +) | 100% | 1.3504 | 60% |

| Personal control beliefs over illness | 100% | 1.0572 | 100% |

| Income Middle (ref. Low) | 100% | 0.7705 | 100% |

| Income High (ref. Low) | 100% | 1.6132 | 100% |

| Postmenopausal | 100% | 1.1308 | 7% |

| What done to cope: See it as a challenge | 100% | 1.1008 | 100% |

| General self−efficacy 1 item | 97% | 1.0398 | 97% |

| Triple negative | 93% | 0.8909 | 33% |

| Social functioning | 87% | 1.0019 | 97% |

| Fighting MAC | 80% | 1.1059 | 73% |

| Depression HADS | 77% | 0.9431 | 83% |

| Anxiety HADS | 70% | 0.9368 | 83% |

| Negative Life Events: Two or more (ref. No) | 70% | 0.9331 | 53% |

| Variable | Selection Freq (%) Penalized Site |

Mean OR1 Penalized Site |

Selection Freq (%) Unpenalized Site |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| Performance2: log-loss = 0.300, Brier score = 0.0892, ROC-AUC = 0.941 | |||

| Anxiety HADS | 100% | 1.2873 | 100% |

| Arm Symptoms BR23 | 100% | 1.0028 | 100% |

| Depression HADS | 100% | 15.3494 | 100% |

| Financial impact C30 | 100% | 1.0006 | 100% |

| Future Perspective Image BR23 | 100% | 0.9978 | 100% |

| Catastrophizing CERQ | 100% | 1.1142 | 100% |

| Manageability SOC | 100% | 0.9752 | 100% |

| Meaningfulness SOC | 100% | 0.9872 | 100% |

| Optimism LOT | 100% | 0.9384 | 100% |

| Resilience CDRISC | 100% | 0.7783 | 63% |

| Role functioning | 100% | 0.9948 | 100% |

| Italy (ref.Portugal) | 100% | 1.3646 | - |

| Finland (ref.Portugal) | 100% | 0.8601 | - |

| Unemployed/Housewife (ref. Full/part− time/Self−employed) | 100% | 1.2159 | 0% |

| Coping with cancer CBI | 93% | 0.9806 | 0% |

| Distress thermometer NCCN | 90% | 1.0306 | 77% |

| Exercise level: Heavy (ref. No) | 80% | 0.937 | 0% |

| Month 33 | |||

| Performance2: log-loss = 0.370, Brier score = 0.115, ROC-AUC = 0.905 | |||

| Anxiety HADS | 100% | 1.8654 | 100% |

| Emotional functioning C30 | 100% | 0.9941 | 100% |

| Future Perspective Image BR23 | 100% | 0.9949 | 100% |

| Anxious preoccupation MAC | 100% | 1.3574 | 100% |

| Helpless MAC | 100% | 1.3366 | 100% |

| Spiritual change PTGI | 100% | 1.0459 | 73% |

| Emotional support mMOS | 100% | 0.7919 | 100% |

| Negative affect PANAS | 100% | 1.5575 | 100% |

| Positive affect PANAS | 100% | 0.8326 | 100% |

| Italy (ref.Portugal) | 100% | 1.7245 | - |

| Finland (ref.Portugal) | 100% | 0.709 | - |

| Exercise level: Heavy (ref. No) | 100% | 0.828 | 20% |

| Distress thermometer NCCN | 100% | 1.0686 | 100% |

| Radiotherapy | 100% | 0.9329 | 0% |

| Fatigue C30 | 97% | 1.0028 | 97% |

| Pain C30 | 97% | 1.0027 | 90% |

| Sexual Enjoyment BR23 | 93% | 0.997 | 77% |

| Arm Symptoms BR23 | 90% | 1.0023 | 80% |

| Sexual functioning BR23 | 83% | 0.9974 | 80% |

| University education | 80% | 0.9706 | 0% |

| What done to cope: Exercised | 80% | 0.9772 | 17% |

| Cognitive Function C30 | 70% | 0.9986 | 93% |

| Avoidance MAC | 63% | 1.0353 | 0% |

| Variable | Selection Freq (%) Penalized Site |

Mean OR1 | Selection Freq (%) Unpenalized Site |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| Performance2: log-loss = 0.248, Brier score = 0.067, ROC-AUC = 0.781 | |||

| Diarrhea C30 | 100% | 1.0046 | 100% |

| Manageability SOC | 100% | 0.9796 | 3% |

| Optimism LOT | 100% | 0.9043 | 10% |

| Pain C30 | 100% | 1.0163 | 100% |

| Role functioning | 100% | 0.9987 | 97% |

| Finland (ref. Portugal) | 100% | 0.8797 | - |

| Month 33 | |||

| Performance2: log-loss = 0.244, Brier score = 0.066, ROC-AUC = 0.754 | |||

| Diarrhea C30 | 100% | 1.0077 | 97% |

| Emotional functioning C30 | 100% | 0.9885 | 87% |

| Mental illness (ref. No) | 100% | 1.8311 | 100% |

| Triple−negative | 100% | 1.8134 | 60% |

| Finland (ref. Portugal) | 100% | 0.5863 | - |

| University education | 100% | 0.8106 | 93% |

| Unemployed/Housewife (ref. Full/part− time/Self−employed) | 100% | 1.3757 | 10% |

| What done to cope: Talked to the physician | 100% | 1.1374 | 87% |

| Income Middle (ref. Low) | 97% | 0.8602 | 40% |

| Anxiety HADS | 93% | 1.3522 | 90% |

| Sexual functioning BR23 | 87% | 0.9958 | 73% |

| Exercise level: Heavy (ref. No) | 83% | 0.8848 | 0% |

| Pain C30 | 67% | 1.0017 | 13% |

| Variable | Selection Freq (%) Penalized Site |

Mean OR1 Penalized Site |

Selection Freq (%) Unpenalized Site |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | |||

| Performance2: log-loss = 0.575, Brier score = 0.1944, ROC–AUC = 0.664 | |||

| Manageability SOC | 100% | 1.0202 | 100% |

| Optimism LOT | 100% | 1.1608 | 10% |

| Italy (ref.Portugal) | 100% | 0.8259 | - |

| Endocrine only (ref. Chemo only +/−Anti−HER2) | 100% | 0.8059 | 7% |

| Income High (ref. Low) | 100% | 1.1661 | 3% |

| Finland (ref. Portugal) | 60% | 1.0232 | - |

| Month 33 | |||

| Performance: log-loss = 0.558, Brier score = 0.1869, ROC–AUC = 0.696 | |||

| Anxiety HADS | 100% | 0.6592 | 97% |

| Italy (ref. Portugal) | 100% | 0.7177 | - |

| Endocrine only (ref. Chemo only +/−Anti−HER2) | 100% | 0.7821 | 23% |

| Income High (ref. Low) | 100% | 1.3056 | 57% |

| Spiritual change PTGI | 90% | 0.9701 | 40% |

| Special diet (ref. None) | 90% | 0.8446 | 77% |

| What done to cope: Talked to sb important | 90% | 1.0455 | 27% |

| Emotional functioning C30 | 87% | 1.0028 | 87% |

| Upset hair image BR23 | 80% | 1.0012 | 17% |

| Metabolic diseases | 77% | 0.9565 | 73% |

| Finland (ref. Portugal) | 77% | 1.0455 | - |

| Negative affect PANAS | 73% | 0.9551 | 0% |

| Emotional support mMOS | 70% | 1.0249 | 87% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).