Submitted:

01 April 2025

Posted:

02 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

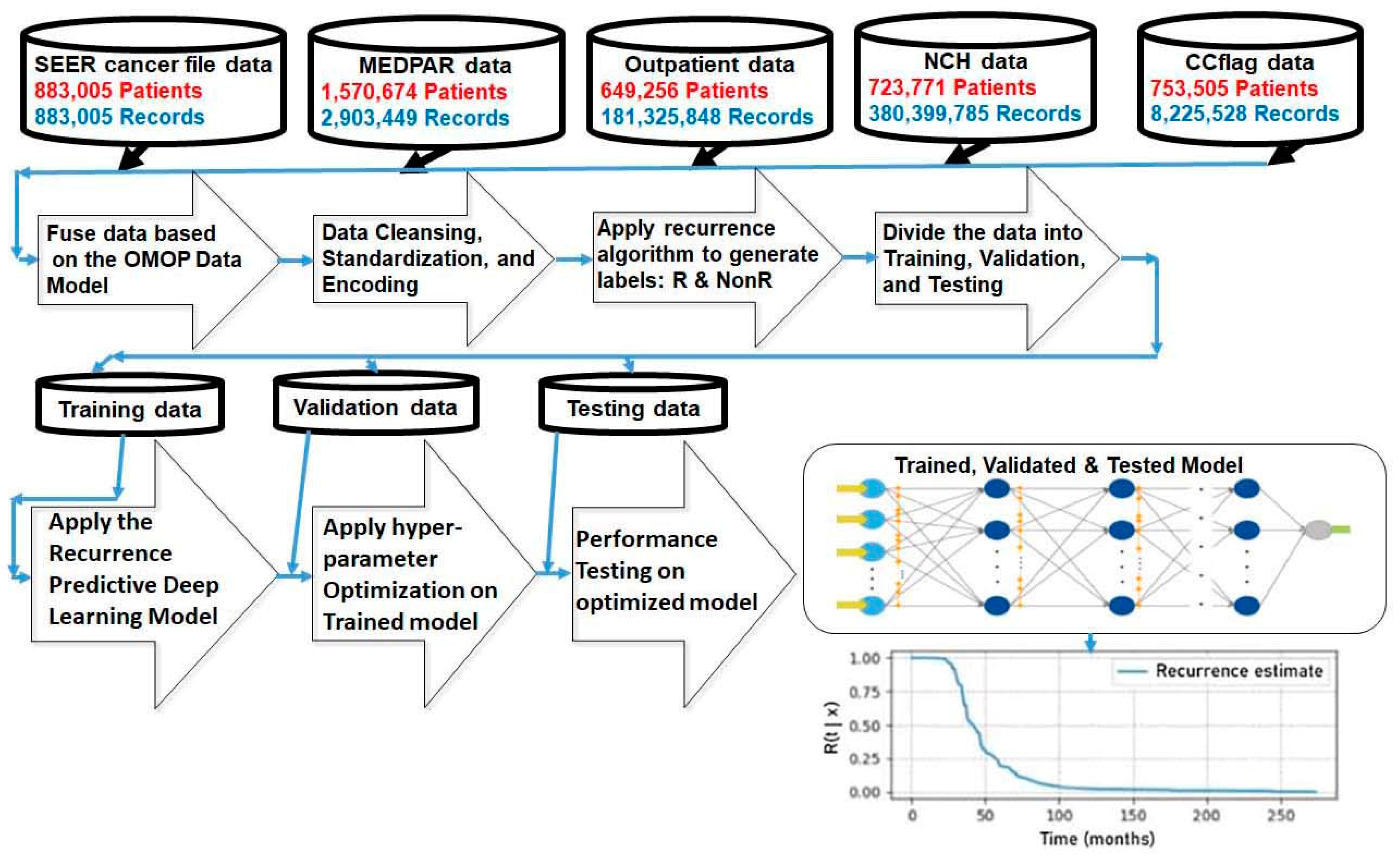

2. Methods

2.1. Dataset and Patients

2.2. Recurrence

2.3. Deep Learning Predictive Modeling

Discrete Time-to-Event Data

Experiments

3. Results

3.1. Patient Characteristics

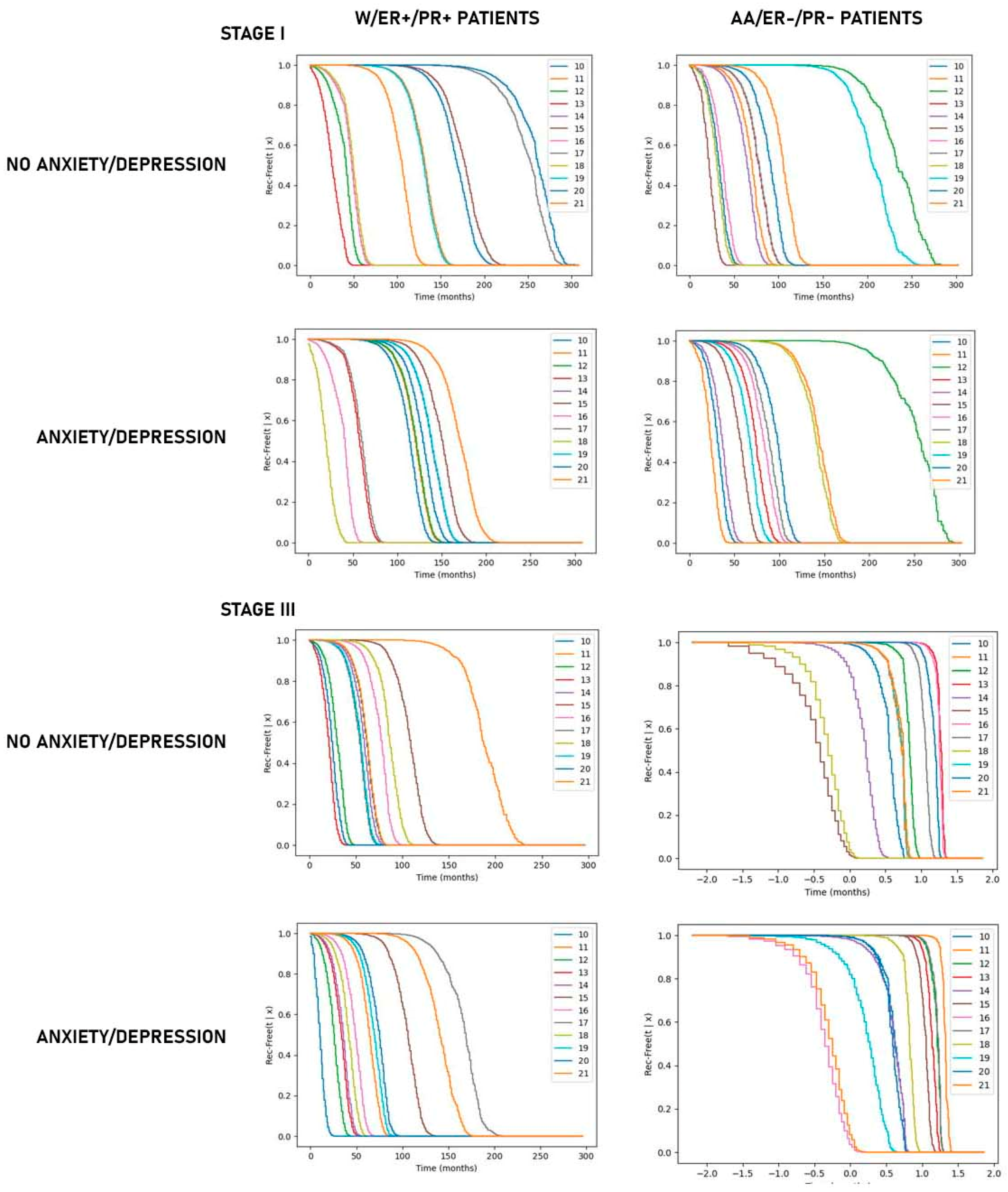

3.2. Predictive Modeling of Recurrence-Free Survival

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Braun, S.; Pantel, K.; Muller, P.; Janni, W.; Hepp, F.; Kentenich, C.R.; Gastroph, S.; Wischnik, A.; Dimpfl, T.; Kindermann, G.; et al. Cytokeratin-positive cells in the bone marrow and survival of patients with stage I, II, or III breast cancer. New. Engl. J. Med. 2000, 342, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartkopf, A.D.; Brucker, S.Y.; Taran, F.A.; Harbeck, N.; von Au, A.; Naume, B.; Pierga, J.Y.; Hoffmann, O.; Beckmann, M.W.; Rydén, L.; et al. Disseminated tumour cells from the bone marrow of early breast cancer patients: Results from an international pooled analysis. Eur. J. Cancer 2021, 154, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korah, R.; Boots, M.; Wieder, R. Integrin α5β1 promotes survival of growth-arrested breast cancer cells: An in vitro paradigm for breast cancer dormancy in bone marrow. Cancer Research 2004, 64, 4514–4522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Najmi, S.; Korah, R.; Chandra, R.; Abdellatif, M.; Wieder, R. Flavopiridol blocks integrin-mediated survival in dormant breast cancer cells. Clinical Cancer Research 2005, 11, 2038–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrios, J.; Wieder, R. Dual FGF-2 and intergrin α5β1 signaling mediate GRAF-induced RhoA inactivation in a model of breast cancer dormancy. Cancer Microenvironment 2009, 2, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, C.A. Parallel progression of primary tumours and metastases. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2009, 9, 302–312Car19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Wu, T.; Liu, A.Y.; Ouyang, G. Differentiation and transdifferentiation potentials of cancer stem cells. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 39550–39563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tivari, S.; Lu, H.; Dasgupta, T.; De Lorenzo, M.S.; Wieder, R. Reawakening of dormant estrogen-dependent human breast cancer cells by bone marrow stroma secretory senescence. Cell Communication and Signaling 2018, 16, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobre, A.R.; Risson, E.; Singh, D.K.; di Martino, J.; Cheung, J.F.; Wang, J.; Johnson, J.; Russnes, H.G.; Bravo-Cordero, J.J.; Birbrair, A.; et al. Bone Marrow NG2+/Nestin+ mesenchymal stem cells drive DTC dormancy via TGFβ2. Nat. Cancer 2021, 2, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieder, R. Bone marrow stoma co-cultivation model of breast cancer dormancy. Methods in Molecular Biology 2024, 2811, 55–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreekumar, A.; Lu, M.; Choudhury, B.; Pan, T.C.; Pant, D.K.; Lawrence-Paul, M.R.; Sterner, C.J.; Belka, G.K.; Toriumi, T.; Benz, B.A.; Escobar-Aguirre, M.; Marino, F.E.; Esko, J.D.; Chodosh, L.A. B3GALT6 promotes dormant breast cancer cell survival and recurrence by enabling heparan sulfate-mediated FGF signaling. Cancer Cell. 2024, 42, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fluegen, G.; Avivar-Valderas, A.; Wang, Y.; Padgen, M.R.; Williams, J.K.; Nobre, A.R.; Calvo, V.; Cheung, J.F.; Bravo-Cordero, J.J.; Entenberg, D.; et al. Phenotypic heterogeneity of disseminated tumour cells is preset by primary tumour hypoxic microenvironments. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017, 19, 120–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, S.; Kentenich, C.; Janni, W.; Hepp, F.; de Waal, J.; Willegroth, F.; Sommer, H.; Pantel, K. Lack of an effect of adjuvant chemotherapy on the elimination of single dormant tumor cells in bone marrow of high risk breast cancer patients. J. Clin. Onc. 2000, 18, 80–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naumov, G.N.; Townson, J.L.; MacDonald, I.C.; Wilson, S.M.; Bramwell, V.H.; Groom, A.C.; Chambers, A.F. Ineffectiveness of doxorubicin treatment on solitary dormant mammary carcinoma cells or late-developing metastases. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2003, 82, 199–206. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, P.; Dasgupta, A.; Grzelak, C.A.; Kim, J.; Barrett, A.; Coleman, I.M.; Shor, R.E.; Goddard, E.T.; Dai, J.; Schweitzer, E.M.; et al. Targeting the perivascular niche sensitizes disseminated tumour cells to chemotherapy. Nat. Cell Biol. 2019, 21, 238–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, R.; Chen, X.; Cowley, N.; Ottewell, P.D.; Hawkins, R.J.; Hunter, K.D.; Hobbs, J.K.; Brown, N.J.; Holen, I. Osteoblast-derived paracrine and juxtacrine signals protect disseminated breast cancer cells from stress. Cancers 2021, 13, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieder, R. Awakening of Dormant Breast Cancer Cells in the Bone Marrow. Cancers 2023, 15, 3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieder, R. Insurgent micrometastases: Sleeper cells and harboring the enemy. J. Surgical Oncology 2005, 89, 207–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, S.; Vogl, F.D.; Naume, B.; Janni, W.; Osborne, M.P.; Coombes, R.C.; Schlimok, G.; Diel, I.J.; Gerber, B.; Gebauer, G.; et al. A pooled analysis of bone marrow micrometastasis in breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005, 353, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, C.; Oh, D.S.; Wessels, L.; Weigelt, B.; Nuyten, D.S.; Nobel, A.B.; van't Veer, L.J.; Perou, C.M. Concordance among gene-expression-based predictors for breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006, 355, 560–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Swartz, M.D.; Zhao, H.; Kapadia, A.S.; Lai, D.; Rowan, P.J.; Buchholz, T.A.; Giordano, S.H. Hazard of recurrence among women after primary breast cancer treatment--a 10-year follow-up using data from SEER-Medicare. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012, 21, 800–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Y.Z.; Wang, L.; Hu, X.; Shao, Z.M. Effect of tumor size on breast cancer-specific survival stratified by joint hormone receptor status in a SEER population-based study. Oncotarget. 2015, 6, 22985–22995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, R.; Trudeau, M.; Pritchard, K.I.; Hanna, W.M.; Kahn, H.K.; Sawka, C.A.; Lickley, L.A.; Rawlinson, E.; Sun, P.; Narod, S.A. Triple-negative breast cancer: Clinical features and patterns of recurrence. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 4429–4434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jatoi, I.; Anderson, W.F.; Jeong, J.H.; Redmond, C.K. Breast cancer adjuvant therapy: Time to consider its time-dependent effects. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 2301–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naume, B.; Synnestvedt, M.; Falk, R.S.; Wiedswang, G.; Weyde, K.; Risberg, T.; Kersten, C.; Mjaaland, I.; Vindi, L.; Sommer, H.H.; et al. Clinical outcome with correlation to disseminated tumor cell (DTC) status after DTC-guided secondary adjuvant treatment with docetaxel in early breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 3848–3857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colleoni, M.; Sun, Z.; Price, K.N.; Karlsson, P.; Forbes, J.F.; Thürlimann, B.; Gianni, L.; Castiglione, M.; Gelber, R.D.; Coates, A.S.; et al. Annual Hazard Rates of Recurrence for Breast Cancer During 24 Years of Follow-Up: Results from the International Breast Cancer Study Group Trials I to V. J. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 34, 927–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borgen, E.; Rypdal, M.C.; Sosa, M.S.; Renolen, A.; Schlichting, E.; Lonning, P.E.; Synnestvedt, M.; Aguirre-Ghiso, J.A.; Naume, B. NR2F1 stratifies dormant disseminated tumor cells in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. 2018, 20, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, C.A. Cancer progression and the invisible phase of metastatic colonization. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2020, 20, 681–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushnell, G.G.; Deshmukh, A.P.; den Hollander, P.; Luo, M.; Soundararajan, R.; Jia, D.; Levine, H.; Mani, S.A.; Wicha, M.S. ; Breast cancer dormancy: Need for clinically relevant models to address current gaps in knowledge. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2021, 7, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, R.; Newman, L.; Davis, M. Breast cancer disparities in outcomes; unmasking biological determinants associated with racial and genetic diversity. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 2022, 39, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Garlapati, C.; Aneja, R. Epigenetic determinants of racial disparity in breast cancer: Looking beyond genetic alterations. Cancers 2022, 14, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiagge, E.; Chitale, D.; Newman, L.A. Triple-negative breast cancer, stem cells, and African ancestry. Am. J. Pathol. 2018, 188, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Barner, J.C.; Moczygemba, L.R.; Rascati, K.L.; Park, C.; Kodali, D. Comparing survival outcomes between neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy within breast cancer subtypes and stages among older women: A SEER-Medicare analysis. Breast Cancer 2023, 30, 489–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wieder, R. Fibroblasts as turned agents in cancer progression. Cancers 2023, 15, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, O.; Hossain, F.; Danos, D.; Lassak, A.; Scribner, R.; Miele, L. Racial disparities in triple negative breast cancer: A review of the role of biologic and non-biologic factors. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 576964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, M.C.; Wheeler, S.B.; Reeder-Hayes, K. Racial/ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in endocrine therapy adherence in breast cancer: A systematic review. Am. J. Public Health 2015, 105 (Suppl. S3), e4–e15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, B.; Olopade, O.I. A perfect storm: How tumor biology, genomics, and health care delivery patterns collide to create a racial survival disparity in breast cancer and proposed interventions for change. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015, 65, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Autelitano, M.; Bisanti, L. Re: Frequency and cost of chemotherapy-related serious adverse effects in a population sample of women with breast cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2006, 98, 1826–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieder, R.; Adam, N. Racial Disparities in Breast Cancer Treatments and Adverse Events in the SEER-Medicare Data. Cancers 2023, 15, 4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, N.; Wieder, R. Temporal Association Rule Mining: Race-Based Patterns of Treatment-Adverse Events in Breast Cancer Patients Using SEER–Medicare Dataset. Biomedicines. 2024, 12, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurts, Y.M.; Witteveen, A.; Bretveld, R.; Poortmans, P.M.; Sonke, G.S.; Strobbe, L.J.A.; Siesling, S. Patterns and predictors of first and subsequent recurrence in women with early breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017, 165, 709–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sreekumar, A.; Lu, M.; Choudhury, B.; Pan, T.C.; Pant, D.K.; Lawrence-Paul, M.R.; Sterner, C.J.; Belka, G.K.; Toriumi, T.; Benz, B.A.; Escobar-Aguirre, M.; Marino, F.E.; Esko, J.D.; Chodosh, L.A. B3GALT6 promotes dormant breast cancer cell survival and recurrence by enabling heparan sulfate-mediated FGF signaling. Cancer Cell. 2024, 42, 52–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.; Yang, J.; Shimura, T.; Merritt, L.; Alluin, J.; Man, E.; Daisy, C.; Aldakhlallah, R.; Dillon, D.; Pories, S.; Chodosh, L.A.; Moses, M.A. Escape from breast tumor dormancy: The convergence of obesity and menopause. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2022, 119, e2204758119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wang, N.; Zhong, L.; Wang, S.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, B.; Zhang, J.; Lin, Y.; Wang, Z. Prognostic value of depression and anxiety on breast cancer recurrence and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 282,203 patients. Mol. Psychiatry 2020, 25, 3186–3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forget, P.; Vandenhende, J.; Berliere, M.; Machiels, J.P.; Nussbaum, B.; Legrand, C.; DeKock, M. Do intraoperative analgesics influence breast cancer recurrence after mastectomy? A retrospective analysis. Anesth. Analg. 2010, 110, 1630–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retsky, M.; Rogers, R.; Demicheli, R.; Hrushesky, W.J.; Gukas, I.; Vaidya, J.S.; Baum, M.; Forget, P.; Dekock, M.; Pachmann, K. Nsaid analgesic ketorolac used perioperatively may suppress early breast cancer relapse: Particular relevance to triple negative subgroup. Breast Cancer Research & Treatment 2012, 134, 881–888. [Google Scholar]

- Hanin, L.; Pavlova, L. A quantitative insight into metastatic relapse of breast cancer. J. Theor. Biol. 2016, 394, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaashua, L.; Shabat-Simon, M.; Haldar, R.; Matzner, P.; Zmora, O.; Shabtai, M.; Sharon, E.; Allweis, T.; Barshack, I.; Hayman, L.; et al. Perioperative Cox-2 and beta-adrenergic blockade improves metastatic biomarkers in breast cancer patients in a phase-ii randomized trial. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 4651–4661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar, R.; Ricon-Becker, I.; Radin, A.; Gutman, M.; Cole, S.W.; Zmora, O.; Ben-Eliyahu, S. Perioperative cox2 and beta-adrenergic blockade improves biomarkers of tumor metastasis, immunity, and inflammation in colorectal cancer: A randomized controlled trial. Cancer 2020, 126, 3991–4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Cock, J.M.; Shibue, T.; Dongre, A.; Keckesova, Z.; Reinhardt, F.; Weinberg, R.A. Inflammation triggers zeb1-dependent escape from tumor latency. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 6778–6784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, N.D.; Elias, M.; Guiro, K.; Bhatia, R.; Greco, S.J.; Bryan, M.; Gergues, M.; Sandiford, O.A.; Ponzio, N.M.; Leibovich, S.J.; et al. Exosomes from differentially activated macrophages influence dormancy or resurgence of breast cancer cells within bone marrow stroma. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricon, I.; Hanalis-Miller, T.; Haldar, R.; Jacoby, R.; Ben-Eliyahu, S. Perioperative biobehavioral interventions to prevent cancer recurrence through combined inhibition of beta-adrenergic and cyclooxygenase 2 signaling. Cancer 2019, 125, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, W.; Zhang, L.; Dong, Y.; Tian, Z.; Chen, Y.; Dong, S. Tumour dormancy in inflammatory microenvironment: A promising therapeutic strategy for cancer-related bone metastasis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2020, 77, 5149–5169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ecker, B.L.; Lee, J.Y.; Sterner, C.J.; Solomon, A.C.; Pant, D.K.; Shen, F.; Peraza, J.; Vaught, L.; Mahendra, S.; Belka, G.K.; Pan, T.C.; Schmitz, K.H.; Chodosh, L.A. Impact of obesity on breast cancer recurrence and minimal residual disease. Breast Cancer Res. 2019, 21, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Bowers, E.; Singer, K. Obesity-induced inflammation: The impact of the hematopoietic stem cell niche. Jci Insight. 2021, 6, 145295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpatkin, S. Does hypercoagulability awaken dormant tumor cells in the host? J. Thromb. Haemost. 2004, 2, 2103–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fogarty, H.; Townsend, L.; Morrin, H.; Ahmad, A.; Comerford, C.; Karampini, E.; Englert, H.; Byrne, M.; Bergin, C.; O'Sullivan, J.M.; et al. Persistent endotheliopathy in the pathogenesis of long covid syndrome. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2021, 19, 2546–2553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takatsuka, H.; Wakae, T.; Mori, A.; Okada, M.; Fujimori, Y.; Takemoto, Y.; Okamoto, T.; Kanamaru, A.; Kakishita, E. Endothelial damage caused by cytomegalovirus and human herpesvirus-6. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2003, 31, 475–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyakutake, M.T.; Steinberg, E.; Disla, E.; Heller, M. Concomitant infection with epstein-barr virus and cytomegalovirus infection leading to portal vein thrombosis. J. Emerg. Med. 2019, 57, e49–e51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampeerawipakorn, O.; Navasumrit, P.; Settachan, D.; Promvijit, J.; Hunsonti, P.; Parnlob, V.; Nakngam, N.; Choonvisase, S.; Chotikapukana, P.; Chanchaeamsai, S.; et al. Health risk evaluation in a population exposed to chemical releases from a petrochemical complex in Thailand. Environ. Res. 2017, 152, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaguin, M.; Fardel, O.; Lecureur, V. Exposure to diesel exhaust particle extracts (DEPe) impairs some polarization markers and functions of human macrophages through activation of AhR and Nrf2. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0116560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montoya, A.; Amaya, C.N.; Belmont, A.; Diab, N.; Trevino, R.; Villanueva, G.; Nahleh, Z. Use of non-selective beta-blockers is associated with decreased tumor proliferative indices in early stage breast cancer. . Oncotarget 2017, 8, 6446–6460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montoya, A.; Varela-Ramirez, A.; Dickerson, E.; Pasquier, E.; Torabi, A.; Aguilera, R.; Bryan, B. The beta adrenergic receptor antagonist propranolol alters mitogenic and apoptotic signaling in late stage breast cancer. . Biomedical Journal 2019, 42, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Sun, J.; Wu, T.; Lu, X.; Du, Y.; Duan, H.; Tian, J. Effects of serum from breast cancer surgery patients receiving perioperative dexmedetomidine on breast cancer cell malignancy: A prospective randomized controlled trial. . Cancer Medicine 2019, 8, 7603–7612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiller, J.G.; Cole, S.W.; Crone, E.M.; Byrne, D.J.; Shackleford, D.M.; Pang, J.B.; Henderson, M.A.; Nightingale, S.S.; Ho, K.M.; Myles, P.S.; Fox, S.; Riedel, B.; Sloan, E.K. Preoperative β-Blockade with Propranolol Reduces Biomarkers of Metastasis in Breast Cancer: A Phase II Randomized Trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2020, 26, 1803–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Haji, H.; Souadka, A.; Patel, B.N.; Sbihi, N.; Ramasamy, G.; Patel, B.K.; Ghogho, M.; Banerjee, I. Evolution of breast cancer recurrence risk prediction: A systematic review of statistical and machine learning–based models. JCO Clinical Cancer Informatics 2023, 7, p.e2300049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauritzen, A.D.; Berg, T.; Jensen, M.B.; Lillholm, M.; Knoop, A. Identifying recurrent breast cancer patients in national health registries using machine learning. Acta Oncologica. 2023, 62, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sittenfeld, S.M.C.; Zabor, E.C.; Hamilton, S.N.; et al. A multi-institutional prediction model to estimate the risk of recurrence and mortality after mastectomy for T1-2N1 breast cancer. Cancer 2022, 128, 3057–3066, © 2023 by American Society of Clinical Oncology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, S.J.; Hou, M.F.; Chang, H.T.; Chiu, C.C.; Lee, H.H.; Yeh, S.C.; Shi, H.Y. Machine learning algorithms to predict recurrence within 10 years after breast cancer surgery: A prospective cohort study. Cancers 2020, 12, 3817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Xu, Y.; Lin, Y.; et al. Comparison of CTS5 risk model and 21-gene recurrence score assay in large-scale breast cancer population and combination of CTS5 and recurrence score to develop a novel nomogram for prognosis prediction. Breast 2022, 63, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudloff, U.; Jacks, L.M.; Goldberg, J.I.; et al. Nomogram for predicting the risk of local recurrence after breast-conserving surgery for ductal carcinoma in situ. J Clin Oncol 2010, 28, 3762–3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, W.; Kim, K.S.; Lee, J.E.; et al. Development of novel breast cancer recurrence prediction model using support vector machine. J Breast Cancer 2012, 15, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohebian, M.R.; Marateb, H.R.; Mansourian, M.; et al. A hybrid computer-aided-diagnosis system for prediction of breast cancer recurrence (HPBCR) using optimized ensemble learning. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 2016, 15, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, W.; Kim, K.S.; Park, R.W. Nomogram of naive Bayesian model for recurrence prediction of breast cancer. Healthc Inform Res 2016, 22, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Ye, Y.; Barcenas, C.H.; et al. Personalized prognostic prediction models for breast cancer recurrence and survival incorporating multidimensional data. J Natl Cancer Inst 2016, 109, djw314. [Google Scholar]

- Vazifehdan, M.; Moattar, M.H.; Jalali, M. A hybrid Bayesian network and tensor factorization approach for missing value imputation to improve breast cancer recurrence prediction. J King Saud Univ Comput Inf Sci 2018, 31, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.H.; Kim, T.-Y.; Kim, M.; et al. Development of a nomogram to predict the recurrence score of 21-gene prediction assay in hormone receptor–positive early breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer 2019, 20, 98–107.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Su, K.; Zhao, H. A case-based ensemble learning system for explainable breast cancer recurrence prediction. Artif Intell Med 2020, 107, 101858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Khan, S.A.; et al. Prediction of breast cancer distant recurrence using natural language processing and knowledge-guided convolutional neural network. Artif Intell Med 2020, 110, 101977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltres, A.; Al Masry, Z.; Zemouri, R.; et al. Prediction of Oncotype DX recurrence score using deep multi-layer perceptrons in estrogen receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer 2020, 27, 1007–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwohaibi, M.; Alzaqebah, M.; Alotaibi, N.M.; et al. A hybrid multi-stage learning technique based on brain storming opti- mization algorithm for breast cancer recurrence prediction. J King Saud Univ—Comput Inf Sci 2021, 34, 5192–5203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawngliani, M.S.; Chandrasekaran, N.; Lalmawipuii, R.; et al. Breast cancer recurrence prediction model using voting technique. In International Conference on Mobile Computing and Sustainable Informatics. EAI/Springer Innovations in Communication and Computing; Raj, J.S., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J.-Y.; Lee, Y.S.; Yu, J.; et al. Deep learning-based prediction model for breast cancer recurrence using adjuvant breast cancer cohort in tertiary cancer center registry. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 596364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, N.N.; Hsu, C.-Y.; Huang, C.-C.; et al. Prediction of breast cancer recurrence using a deep convolutional neural network without region-of-interest labeling. Front Oncol 2021, 11, 734015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osako, T.; Matsuura, M.; Yotsumoto, D.; et al. A prediction model for early systemic recurrence in breast cancer using a molecular diagnostic analysis of sentinel lymph nodes: A large-scale, multicenter cohort study. Cancer 2022, 128, 1913–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xin, L.; Wu, Q.; Zhan, C.; et al. Multicenter study of the clinicopathological features and recurrence risk prediction model of early-stage breast cancer with low-positive human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 expression in China (Chinese Society of Breast Surgery 021). Chin Med J 2022, 135, 697–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koume, M.; Seguin, L.; Bouhnik, A.D.; Urena, R. Predicting Fear of Breast Cancer Recurrence from Healthcare Reimbursement Data using Deep Learning. In 2024 IEEE 37th International Symposium on Computer-Based Medical Systems (CBMS) (pp. 57–60). IEEE.

- Mazo, C.; Aura, C.; Rahman, A.; Gallagher, W.M.; Mooney, C. Application of artificial intelligence techniques to predict risk of recurrence of breast cancer: A systematic review. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2022, 12, 1496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wang, N.; Zhong, L.; Wang, S.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, B.; Zhang, J.; Lin, Y.; Wang, Z. Prognostic value of depression and anxiety on breast cancer recurrence and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 282,203 patients. Molecular psychiatry. 2020, 25, 3186–3197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Sun, H.; Luo, X.; Li, W.; Yang, F.; Xu, W.; Ding, K.; Zhou, J.; Liu, W.; Garg, S.; Jackson, T. Network connectivity between fear of cancer recurrence, anxiety, and depression in breast cancer patients. Journal of affective disorders. 2022, 309, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, C.; Lopes-Conceição, L.; Fontes, F.; Ferreira, A.; Pereira, S.; Lunet, N.; Araújo, N. Prevalence and persistence of anxiety and depression over five years since breast cancer diagnosis—The NEON-BC prospective study. Current oncology. 2022, 29, 2141–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheu, C.; Singh, M.; Tock, W.L.; Eyrenci, A.; Galica, J.; Hébert, M.; Frati, F.; Estapé, T. Fear of cancer recurrence, health anxiety, worry, and uncertainty: A scoping review about their conceptualization and measurement within breast cancer survivorship research. Frontiers in psychology. 2021, 12, 644932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, M.M.; Siah, R.C.; Lam, A.S.; Cheng, K.K. The effect of psychological interventions on fear of cancer recurrence in breast cancer survivors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2022, 78, 3069–3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, H.M.; Son, C.G. The risk of psychological stress on cancer recurrence: A systematic review. Cancers. 2021, 13, 5816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gold, M.; Dunn, L.B.; Phoenix, B.; Paul, S.M.; Hamolsky, D.; Levine, J.D.; Miaskowski, C. Co-occurrence of anxiety and depressive symptoms following breast cancer surgery and its impact on quality of life. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2016, 20, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinty, H.L.; Small, B.J.; Laronga, C.; Jacobsen, P.B. Predictors and patterns of fear of cancer recurrence in breast cancer survivors. Health Psychology. 2016, 35, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Enewold, L.; Parsons, H.; Zhao, L.; Bott, D.; Rivera, D.R.; Barrett, M.J.; Virnig, B.A.; Warren, J.L. Updated overview of the SEER-Medicare data: Enhanced content and applications. JNCI Monographs. 2020, 2020, 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Sarfati, D.; Gurney, J.; Stanley, J.; Salmond, C.; Crampton, P.; Dennett, E.; Koea, J.; Pearce, N. Cancer-specific administrative data–based comorbidity indices provided valid alternative to Charlson and National Cancer Institute Indices. J. Clinical Epidemiology. 2014, 67, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Barner, J.C.; Moczygemba, L.R.; Rascati, K.L.; Park, C.; Kodali, D. Comparing survival outcomes between neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy within breast cancer subtypes and stages among older women: A SEER-Medicare analysis. Breast Cancer. 2023, 01441-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.L.; Osborne, C.; Goodwin, J.S. Population-based assessment of hospitalizations for toxicity from chemotherapy in older women with breast cancer. J. Clinical Oncology. 2002, 20, 4636–4642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, A.; Autelitano, M.; Bisanti, L. Re: Frequency and cost of chemotherapy-related serious adverse effects in a population sample of women with breast cancer. J. National Cancer Institute. 2006, 98, 1826–1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassett, M.J.; O'Malley, A.J.; Pakes, J.R.; Newhouse, J.P.; Earle, C.C. Frequency and cost of chemotherapy-related serious adverse effects in a population sample of women with breast cancer. J. National Cancer Institute. 2006, 98, 1108–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, N.; Koh, H.A.; Baca, H.C.; Li, Z.; Malecha, S.; Abidoye, O.; Masaquel, A. Clinical impact of chemotherapy-related adverse events in patients with metastatic breast cancer in an integrated health care system. J. Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy. 2015, 21, 863–871. [Google Scholar]

- Groenvold, M.; Petersen, M.A.; Idler, E.; Bjorner, J.B.; Fayers, P.M.; Mouridsen, H.T. Psychological distress and fatigue predicted recurrence and survival in primary breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007, 105, 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, N.; Wieder, R. AI Survival Prediction Modeling: The Importance of Considering Treatments and Changes in Health Status Over Time. Cancers. 2024, 16, 3527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adam, N.; Wieder, R. Predictive Modeling of Long-Term Survivors with Stage IV Breast Cancer Using the SEER-Medicare Dataset. Cancers. 2024, 16, 4033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snoek, J.; Larochelle, H.; Adams, R.P. Practical bayesian optimization of machine learning algorithms. Advances in neural information processing systems. 2012, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Kvamme, H.; Borgan, Ø.; Scheel, I. Time-to-event prediction with neural networks and Cox regression. Journal of Machine Learning Research. 2019, 20, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Mucaki, E.J.; Baranova, K.; Pham, H.Q.; Rezaeian, I.; Angelov, D.; Ngom, A.; Rueda, L.; Rogan, P.K. the Molecular Taxonomy of Breast Cancer International Consortium (METABRIC) Study by Biochemically-inspired Machine Learning [version 3; referees: 2.

- Connors, A.F.; Dawson, N.V.; Desbiens, N.A.; Fulkerson, W.J.; Goldman, L.; Knaus, W.A.; Lynn, J.; Oye, R.K.; Bergner, M.; Damiano, A.; Hakim, R. A controlled trial to improve care for seriously iII hospitalized patients: The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). JAMA 1995, 274, 1591–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WPBC Breast Cancer Wisconsin (Prognostic) Data Set," archive.ics.uci.edu. Available online: https://archive.ics.uci.edu/.

- Pati, A.; Panigrahi, A.; Parhi, M.; Giri, J.; Qin, H.; Mallik, S.; Pattanayak, S.R.; Agrawal, U.K. Performance assessment of hybrid machine learning approaches for breast cancer and recurrence prediction. PLoS ONE. 2024, 19, e0304768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Sun, H.; Luo, X.; Li, W.; Yang, F.; Xu, W.; Ding, K.; Zhou, J.; Liu, W.; Garg, S.; Jackson, T. Network connectivity between fear of cancer recurrence, anxiety, and depression in breast cancer patients. Journal of affective disorders. 2022, 309, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavingia, R.; Jones, K.; Asghar-Ali, A.A. A systematic review of barriers faced by older adults in seeking and accessing mental health care. Journal of Psychiatric Practice 2020, 26, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noyes, K.; Liu, H.; Lyness, J.M.; Friedman, B. Medicare beneficiaries with depression: Comparing diagnoses in claims data with the results of screening. Psychiatr Serv. 2011, 62, 1159–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, S.; Jayadevappa, R.; Zee, J.; Zivin, K.; Bogner, H.R.; Raue, P.J.; Bruce, M.L.; Reynolds CF3rd Gallo, J.J. Concordance Between Clinical Diagnosis and Medicare Claims of Depression Among Older Primary Care Patients. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015, 23, 726–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassett, M.J.; Ritzwoller, D.P.; Taback, N.; Carroll, N.; Cronin, A.M.; Ting, G.V.; Schrag, D.; Warren, J.L.; Hornbrook, M.C.; Weeks, J.C. Validating billing/encounter codes as indicators of lung, colorectal, breast, and prostate cancer recurrence using 2 large contemporary cohorts. Med Care. 2014, 52, e65–e73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, J.L.; Mariotto, A.; Melbert, D.; Schrag, D.; Doria-Rose, P.; Penson, D.; Yabroff, K.R. Sensitivity of Medicare Claims to Identify Cancer Recurrence in Elderly Colorectal and Breast Cancer Patients. Med Care. 2016, 54, e47–e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Algorithm 1: ALGORITHM TO INFER PATIENT'S RECURRENCE | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Input:Window_after_completion_of_adjuvant_therapy=4 Month 2nd_Mal_Neop_BC_dx=19881 SRG=["8511","8512","850","8519","8520","8521","8522","8523","8525","8591","860d1", "8533","8534", "8535","8536","4022","4023","4029","403","4050","4051","8541","8542","8543","8544","8545","8546","8547","8548] PR=["9221","9222","9223","9224","9225","9226","9227","9228","9229","9230","9231","9232","9233","9239","9241"] TR=["G9829","1","2","3","4","5","6","7","8","9","10","11","12","13","14","15","16","17","18","19","20", "21","22", "23","24","25","26","27","28","29","30","31","32","33","34","35","36","37","38","39","40","41","42","43","44","45","46"] |

|||||

|

Output:For Each Patient: Infer her/his Rec_flag and the corresponding Rec_Date |

|||||

|

1 2 |

Initialization: New_Chem_Hor_Bio_Rad_List=[], Mal_Neop_List=[], New_Contralat_List=[], No_Rec_Date←“2050-01-01” |

||||

| 3 | For Each Patient | ||||

|

4 5 6 7 8 9 10 |

Rec_flag← 0, Rec_Date← No_Rec_Date Identify: Date_1st_Chem, Date_1st Hor, Date_1st Bio, Date_1st Rad, Date_1st_Sur, Date_1st_Course_Tr Date_Init_Adj_Therapy←Max{Date_1st_Chem, Date_1st Hor, Date_1st Bio, Date_1st Rad, Date_1st_Sur, Date_1st_Course_Tr } Order visits in ascending order of Visit_Date |

||||

| 11 | For Each Visit | ||||

| 12 | For Each Entry within this Visit | ||||

|

13 14 |

If ( (Visit_Date-Date_Init_Adj_Therapy) >=4mon) And (Sur OR Bio OR Hor OR Rad) |

||||

| 15 | Rec_flag← 1 | ||||

|

16 17 |

Rec_Date ← VisitDate Break |

||||

| 18 | If (Rec_flag = 1) | ||||

|

19 20 21 |

Append this Patient to New_Chem_Hor_Bio_Rad_List Rec_flag ← 0, Rec_Date ← No_Rec_Date |

||||

| 22 | For Each Visit | ||||

| 23 | For Each Entry within this Visit | ||||

| 24 | If (dx_code=2nd_Mal_Neop_BC_dx) | ||||

| 25 | Rec_flag← 1 | ||||

| 26 | If ( (Rec_flag =1 & (Visit_Date < Rec_Date) ) | ||||

| 27 | Rec_Date← Visit_Date | ||||

| 28 | If (Rec_flag = 1) | ||||

|

29 30 31 |

Append this Patient to Mal_Neop_List Rec_flag ← 0, Rec_Date ← No_Rec_Date |

||||

| 32 | For Each of the Ten Recorded Diagnoses | ||||

| 33 | If Diagnosis =1 | ||||

|

34 35 36 |

Prev_Laterality=Current_Laterality Rec_flag← 0 Date_of_Prev_diagnosis ← No_Rec_Date |

||||

|

37 38 |

If ( ((Current_Laterality).isin(2,4,5,9)) & (Prev_Laterality)=1)) OR ((Current_Laterality).isin(1,4,5,9)) & (Prev_Laterality)=2)) ) |

||||

|

39 40 |

Rec_flag1← 1 If (Date_of_this_Diagnosis < Date_of_Prev_Diagnosis) |

||||

| 41 | Rec_Date← Date_of_this_Diagnosis | ||||

| 42 | Date_of_Prev_Diagnosis← Date_of_this_Diagnosis | ||||

| 43 | If (Rec_flag = 1) | ||||

|

44 45 46 |

Append this Patient to New_Contralat_List Rec_flag← 0, Rec_Date← No_Rec_Date |

||||

| 47 | If (patient isin New_Chem_Hor_Bio_Rad_List OR isin Mal_Neop_List OR isin New_Contralat_List)) | ||||

|

48 49 50 |

Rec_flag← 0, Rec_Date← Min{Patient’s Rec_Date in New_Chem_Hor_Bio_Rad_List, Patient’s Rec_Date in Mal_Neop_List, Patient’s Rec_Date in New_Contralat_List} |

||||

| All Patients | All patients with Anxiety/Depression | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | Age + SD | Comorbidity at Dx + SD | Number (%) | p (chi sq) | Age + SD | Comorbidity at Dx + SD | Mos, Dx-Dep/anx Avg+ SD |

|

| Total Patients | 239,288 (100) | 75.2 + 7.2 | 0.6 + 1.5 | 86,745 (100) (36.3% of all) | 75.4 + 7.0 | 0.7 + 1.7 | 31.4 + 48.0 | |

| ER+/PR+ | 154,730 (64.7) | 75.1 + 7.1 | 0.7 + 1.5 | 55,681 (64.2) | n.s. | 75.3 + 7.0 | 0.8 + 1.7 | 29.9 + 46.6 |

| ER+/PR- | 29,278 (12.2) | 75.6 + 7.3 | 0.6 + 1.5 | 10,775 (12.4) | 75.7 + 7.1 | 0.7 + 1.6 | 31.8 + 47.6 | |

| ER-/PR- | 32,400 (13.5) | 74.8 + 7.2 | 0.6 + 1.5 | 11,505 (13.3) | 75.0 + 7.1 | 0.7 + 1.7 | 28.3 + 46.3 | |

| Stage I | 134,598 (56.2) | 74.7 + 6.8 | 0.6 + 1.4 | 49,628 (57.2) | n.s. | 75.0 + 6.7 | 0.7 + 1.6 | 34.5 + 50.2 |

| Stage II | 76,928 (32.1) | 75.8 + 7.6 | 0.7 + 1.6 | 28,098 (32.4) | 76.0 + 7.4 | 0.8 + 1.8 | 28.8 + 46.0 | |

| Stage III | 27,762 (11.6) | 76.0 + 7.7 | 0.6 + 1.6 | 9,019 (10.4) | 76.1 + 7.5 | 0.8 + 1.7 | 22.8 + 39.8 | |

| Race–W | 210,108 (87.8) | 75.3 + 7.2 | 0.6 + 1.5 | 79,239 (91.3) | p = 0 | 75.5 + 7.0 | 0.7 + 1.6 | 31.7 + 48.2 |

| Race–AA | 16,887 (7.1) | 74.8 + 7.2 | 0.8 + 1.7 | 4,781 (5.5) | 75.3 + 7.2 | 1.0 + 2.0 | 27.4 + 44.4 | |

| Race–Other | 12,293 (5.1) | 73.7 + 6.7 | 0.7 + 1.5 | 2,725 (3.1) | 74.2 + 6.6 | 0.9 + 1.8 | 31.3 + 48.3 | |

| Hispanic | 12,603 (5.3) | 4,486 (5.2) | p=0 | |||||

| Non-Recurrent Patients | Recurrent Patients | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | Age + SD | Comorb. at Dx + SD | Number (%) | p (chi sq.) | Age + SD | Comorb. at Dx + SD | Mos, Dx-Recr + SD | Comorb. at recur. + SD | |

| Total Patients | 202,339 (100) (84.6% of all) | 75.2 + 7.2 | 0.6 + 1.5 | 36,949 (100) (15.4% of all) | 74.6 + 6.9 | 0.5 + 1.4 | 37.5 + 44.6 | 2.9 + 3.5 | |

| ER+/PR+ | 133,560 (66.0) | 75.2 + 7.2 | 0.7 + 1.6 | 21,170 (57.3) | p = 0 | 74.5 + 6.8 | 0.6 + 1.4 | 39.7 + 45.6 | 3.2 + 3.5 |

| ER+/PR- | 24,280 (12.0) | 75.7 + 7.3 | 0.6 + 1.5 | 4,998 (13.5) | 75.0 + 7.0 | 0.5 + 1.4 | 36.2 + 41.5 | 3.0 + 3.5 | |

| ER-/PR- | 25,762 (12.7) | 74.9 + 7.3 | 0.6 + 1.5 | 6,638 (18.0) | 74.2 + 6.8 | 0.5 + 1.3 | 28.6 + 37.6 | 2.6 + 3.3 | |

| Stage I | 120,231 (59.4) | 74.7 + 6.8 | 0.6 + 1.4 | 14,367 (38.9) | p = 0 | 74.4 + 6.6 | 0.5 + 1.4 | 46.0 + 50.3 | 3.3 + 3.6 |

| Stage II | 63,363 (31.3) | 76.0 + 7.6 | 0.7 + 1.6 | 13,565 (36.7) | 74.6 + 7.0 | 0.5 + 1.4 | 36.1 + 42.9 | 2.9 + 3.5 | |

| Stage III | 18,745 (9.3) | 76.6 + 7.9 | 0.6 + 1.5 | 9,017 (24.4) | 74.7 + 7.1 | 0.5 + 1.3 | 26.2 + 33.6 | 2.3 + 3.3 | |

| Race–W | 177,554 (87.8) | 75.4 + 7.3 | 0.6 + 1.5 | 32,554 (88.1) | p = 0 | 74.7 + 6.9 | 0.5 + 1.3 | 38.4 + 45.3 | 2.9 + 3.5 |

| Race–AA | 14,189 (7.0) | 74.9 + 7.3 | 0.9 + 1.8 | 2,698 (7.3) | 73.9 + 6.9 | 0.5 + 1.4 | 28.6 + 35.8 | 2.9 + 3.6 | |

| Race–Other | 10,596 (5.2) | 73.8 + 6.7 | 0.0 + 0.3 | 1,697 (4.6) | 73.1 + 6.5 | 0.6 + 1.4 | 35.3 + 43.0 | 3.1 + 3.4 | |

| Hispanic | 10,789 (5.3) | 1,814 (4.9) | p = 0 | ||||||

| Recurrent patients without anxiety/depression | Recurrent patients with anxiety/depression | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) | Age + SD | Mos, Dx- Recr + (SD) | Comorb. at recur. + SD | Number (%) | p (chi sq.) | Age + SD | Mos, Dx-Recr + (SD) p (t-test) |

Comorb.at recur. + SD p (t-test) |

Mos, Dx-Dep /Anx + SD |

|

| Tot. Pts. |

21,412 (100) 14.0% of pts. without anx/dep | 74.5 + 7.0 | 36.3 + 43.6 | 2.4 + 3.1 | 15,537 (100) 17.9% of pts with anx/dep | p= 0 | 74.6 + 6.7 | 39.3 + 46.0 p=0 |

3.6 + 3.8 p=0 |

32.9 + 48.8 |

| ER+/PR+ | 12,101 (56.5) | 74.5 + 7.0 | 38.6 + 44.8 | 2.7 + 3.2 | 9,069 (58.4) | p=0 | 746 + 6.7 | 41.1 + 46.6 p=0 |

3.9 + 3.9 p=0 |

32.7 + 48.0 |

| ER+/PR- | 2,875 (13.4) | 75.1 + 7.1 | 34.9 + 40.1 | 2.5 + 3.1 | 2,123 (13.7) | 74.9 + 7.0 | 38.0 + 43.2 p=0.009 |

3.7 + 3.8 p= |

32.4 + 48.2 | |

| ER-/PR- | 3,976 (18.6) | 74.0 + 6.9 | 27.9 + 37.2 | 2.0 + 2.9 | 2,662 (17.1) | 74.4 + 6.8 | 29.8 + 38.3 p=0.044 |

3.3 + 3.7 p=0 |

25.6 + 42.6 | |

| Stage I | 7,900 (36.9) | 74.4 + 6.7 | 44.6 + 49.4 | 2.8 + 3.2 | 6,467 (41.6) | p=0 | 74.4 + 6.5 | 47.8 + 51.3 p=0 |

3.9.+ 3.9 p=0 |

38.0 + 53.1 |

| Stage II | 7,737 (36.1) | 74.6 + 7.1 | 36.0 + 42.5 | 2.4 + 3.1 | 5,828 (37.5) | 74.7 + 6.9 | 36.2 + 43.3 n.s. |

3.6 + 3.8 p=0 |

32.0 + 48.8 | |

| Stage III | 5,775 (27.0) | 74.6 + 7.2 | 25.3 + 32.8 | 1.8 + 2.8 | 3,242 (20.9) | 74.9 + 7.0 | 27.7 + 34.9 p=0.001 |

3.2 + 3.7 p=0 |

24.3 + 38.8 | |

| Race–W | 18,399 (85.9) | 74.7 + 7.0 | 37.3 + 44.4 | 2.4 + 3.1 | 14,155 (91.1) | p=0 | 74.7 + 6.8 | 39.9 + 46.4 p=0 |

3.6 + 3.8 p=0 |

32.9 + 48.8 |

| Race–AA | 1,799 (8.4) | 73.8 + 7.0 | 27.8 + 35.6 | 2.4 + 3.2 | 899 (5.8) | 74.2 + 6.7 | 30.2 + 36.1 n.s. |

3.9.+ 4.0 p=0 |

30.6 + 46.5 | |

| Race–Oth | 1,214 (5.7) | 73.0 + 6.5 | 34.0 + 41.4 | 2.8 + 3.2 | 583 (3.1) | 73.5 + 6.4 | 38.4 + 46.8 p=0.044 |

3.8 + 3.8 p=0 |

35.9 + 51.9 | |

| Hispanic | 957 (4.5) | 857 (5.5) | p=0 | |||||||

| Model | ER+/PR+ | ER-PR- | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time-dependent Concordance (C-Index) Avg. + SD | Integrated Brier Score (IBS) Avg. + SD | Time-dependent Concordance (C-Index) Avg. + SD | Integrated Brier Score (IBS) Avg. + SD | |

| Stage I | ||||

| CoxTime | 0.989 + 0.001 | 0.031 + 0.007 | 0.983 + 0.001 | 0.028 + 0.007 |

| DeepHit | 0.983 + 0.001 | 0.036 + 0.003 | 0.972 + 0.004 | 0.018 + 0.004 |

| DeepSurv | 0.987 + 0.001 | 0.027 + 0.001 | 0.984 + 0.001 | 0.024 + 0.001 |

|

Nnet-Survival (Logistic Hazard) |

0.982 + 0.001 | 0.026 + 0.001 | 0.969 + 0.001 | 0.055 + 0.002 |

| Stage II | ||||

| CoxTime | 0.981 + 0.001 | 0.056 + 0.022 | 0.972 + 0.001 | 0.055 + 0.018 |

| DeepHit | 0.981 + 0.001 | 0.009 + 0.001 | 0.970 + 0.001 | 0.021 + 0.002 |

| DeepSurv | 0.970 + 0.001 | 0.052 + 0.002 | 0.967 + 0.006 | 0.035 + 0.006 |

|

Nnet-Survival (Logistic Hazard) |

0.982 + 0.001 | 0.026 + 0.001 | 0.966 + 0.001 | 0.045 + 0.003 |

| Stage III | ||||

| CoxTime | 0.968 + 0.001 | 0.024 + 0.009 | 0.955 + 0.002 | 0.028 + 0.025 |

| DeepHit | 0.948 + 0.002 | 0.012 + 0.001 | 0.945 + 0.001 | 0.091 + 0.002 |

| DeepSurv | 0.972 + 0.002 | 0.019 + 0.001 | 0.961 + 0.001 | 0.021 + 0.001 |

|

Nnet-Survival (Logistic Hazard) |

0.965 + 0.002 | 0.039 + 0.002 | 0.928 + 0.003 | 0.030 + 0.002 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).