1. Introduction

The emergence of large language models (LLMs) and related intelligent agents has brought a new scale of cognitive delegation into scientific practice. Researchers now make routine use of such systems to synthesize literature, refine arguments, generate code, and assist with formal reasoning. While these tools clearly accelerate discovery and extend what individual researchers can accomplish, they also alter the structure of epistemic agency itself, raising basic questions about what it means to know, to verify, and to author claims within hybrid systems of cognition.

Beyond their technical performance, LLMs change how access to reasoning is organized. By making large portions of the global corpus of human knowledge readily searchable and responsive, they compress the temporal and organizational dimensions of inquiry. Tasks that once required coordinated teams of specialists working under a principal investigator can, in many cases, now be carried out by a single researcher in sustained interaction with a computational collaborator. At the same time, these systems do not possess independent epistemic agency; they function as instruments that amplify human inference within settings of supervised delegation.

This shift invites a reconsideration of the

epistemic structure of scientific cognition. In the sense used here,

epistemology concerns the logic of knowledge production, including the principles by which scientific claims are generated, verified, and rendered accountable within distributed cognitive systems. Large language models extend the scope of human reasoning in a way that recalls the “extended mind” thesis [

1]. They differ, however, from more familiar cognitive extensions in an important respect: their outputs carry no intrinsic intentionality or justificatory force. The human researcher must therefore remain both interpreter and verifier, integrating machine-generated material into a coherent and accountable body of knowledge.

The central question of this paper is not whether machines can reason, but how their incorporation reshapes human responsibility within collective cognition. Traditional research hierarchies, such as those linking a principal investigator (PI) to junior collaborators, already exemplify distributed reasoning governed by established norms. In these settings, the PI retains conceptual leadership and bears ultimate responsibility for verification and accuracy. In LLM-assisted research, this division of labor is altered in significant ways. Although the system may contribute fluency, structure, or heuristic suggestions, it lacks the epistemic agency required for justification. The moral and epistemic burden of verification therefore remains entirely with the human researcher.

Peer review likewise takes on an expanded epistemic role. Referees are not only gatekeepers of correctness but can be understood as epistemic co-stewards, mediating between private reasoning processes—whether human or machine-assisted—and the public domain of justified belief. In this sense, peer review completes the cycle of distributed cognition: responsibility for truth remains collective among human agents, even when elements of reasoning are computationally extended.

Against this background, the paper develops a formal framework for analyzing human–machine collaboration as a structured form of delegated cognition. Three interdependent operators are introduced: verification , denoting coherence and justification; responsibility mapping, assigning epistemic and moral authorship to human agents; and epistemic value, representing the justificatory weight of results independently of their origin. The framework supports the claim that epistemic legitimacy in AI-assisted research depends not on whether a statement originates from a human or a machine, but on the integrity of verification and on the transparency with which responsibility is assigned within the cognitive system as a whole.

2. Background: Delegation and Verification in Scientific Practice

Artificial intelligence has become an integral component of contemporary scientific cognition, ranging from formal proof assistants such as Lean and Isabelle to large-scale generative systems including GPT and Gemini. These technologies extend well-established traditions of cognitive delegation within science rather than introducing a fundamentally new mode of reasoning. Their significance lies in how they reshape existing practices of verification and control.

Philosophical analyses of mathematics have long emphasized that the defining characteristic of rigorous reasoning resides less in the creative generation of conjectures than in the disciplined organization of their

verification. For Frege, this discipline is realized through formal logical proof; for Lakatos, through dialectical reconstruction and sustained critical dialogue [

2,

3]. This shared emphasis situates mathematics, and scientific inquiry more broadly, within a culture of recursive epistemic control, where claims acquire legitimacy through structured processes of justification rather than through their origin alone.

Complementary perspectives from cognitive anthropology and the sociology of science further reinforce this view by showing that knowledge production is inherently collective and hierarchically organized. Hutchins’ theory of

distributed cognition demonstrates that reasoning is frequently enacted across coordinated systems of humans and artifacts, rather than being confined to individual minds [

4]. From this standpoint, the emergence of large language models represents an intensification of established patterns of delegation. Scientific practice has always relied on the distribution of intellectual labor across collaborators, instruments, and institutions. What distinguishes contemporary AI systems is the opacity of the intermediary: the internal processes through which an LLM transforms prompts into outputs remain largely inaccessible to direct human inspection. The resulting challenge is therefore epistemic in nature, centered on preserving transparency and accountability within inferential processes whose internal dynamics are not directly observable.

Ethical reflection on delegation has traditionally focused on the integrity of authorship. Helgesson and Eriksson [

5] characterize plagiarism as epistemic misconduct because it misrepresents the attribution of cognitive labor and undermines the trust on which collective knowledge production depends. This analysis extends naturally to AI-assisted authorship. Computationally generated contributions acquire legitimacy through the human acts of verification, interpretation, and contextualization that integrate them into justified knowledge claims. In this sense, the moral boundary of authorship aligns closely with the epistemic boundary of justification.

An analogy with auditing offers a useful conceptual lens for clarifying this alignment. Studies by Strathern [

6] and by Shore and Wright [

7] show that contemporary audit cultures reshape institutional behavior by embedding continuous verification into routine practice. Power’s account of the “audit society” [

8] further illustrates how verification has become a pervasive mode of institutional rationality. Within quality management systems, however, auditing also reveals a more constructive dimension: when properly designed, audits function not merely as instruments of surveillance but as mechanisms of

diagnostic learning, oriented toward identifying the causal structure of success and failure.

Applied to scientific inquiry, this perspective suggests that verification in AI-assisted research benefits from becoming explicit, recursive, and auditable. An epistemic audit can therefore be understood as a meta-cognitive process through which researchers document, evaluate, and iteratively refine the reliability of hybrid human–machine reasoning. Under this view, responsibility for epistemic integrity is embedded in structured and transparent procedures that make the trajectory from machine-generated output to validated knowledge explicit. Delegation thus operates as a mechanism of distributed, self-correcting cognition rather than as a source of epistemic opacity.

3. Delegated Reasoning and Distributed Cognition

3.1. Human–Machine Collaboration

Consider a principal investigator S coordinating the work of junior scholars . Each undertakes delegated activities—surveying the literature, formulating intermediate results, or implementing computational components—while S retains conceptual oversight and performs final verification. This configuration exemplifies distributed cognition: the ensemble functions as a single epistemic system in which inferential labor and epistemic control are intentionally distributed rather than centralized.

Now suppose that

S replaces human assistants with a large language model

. Let

where

denotes the integrative process through which

S selects, edits, contextualizes, and verifies intermediate outputs to produce a publishable result. Under appropriate oversight, the intended condition is

expressing equivalently warranted outcomes achieved through distinct modes of delegation.

Within established academic practice, sole authorship by a principal investigator is justified when conceptual leadership and verification remain with that individual. The same rationale extends to the use of an LLM as an assistant. Authorship remains warranted insofar as

S understands, evaluates, and verifies the content incorporated into the final work. Formally, let

where

R assigns each contribution to the human agent accountable for it. This assignment interfaces directly with the moral-responsibility operator

: for every statement

g produced within the collective,

R identifies the human who must ensure that

through verification. Substituting algorithmic for human assistants therefore alters the

mechanism of delegation while preserving its

normative locus.

This account aligns with theories of distributed cognition and extended mind, as well as with sociological analyses of authorship and credit. Scientific inquiry has long relied on shared reasoning while maintaining identifiable human responsibility for integration and justification. LLM assistance modifies the internal pathways by which candidate inferences are generated, while leaving intact the requirement that humans warrant what enters the public record.

These considerations motivate a unified formal language for mixed human–machine workflows. The framework introduced below formalizes verification, responsibility, and epistemic value for systems of delegated cognition.

3.2. Formal Framework of Verification and Responsibility

Let denote statements produced by human collaborators and those generated by an LLM, with .

Verification and moral authorship.

Verification operationalizes moral authorship: to verify a claim is to assume responsibility for its truth. Define

with

Accordingly,

classifies the moral status of

g relative to human agency. Once

R assigns a responsible human, moral predicates apply; prior to assignment, they remain inapplicable rather than false. Operationally,

implies

, whereas

marks a failure to discharge epistemic responsibility.

Epistemic and Moral Coordinates

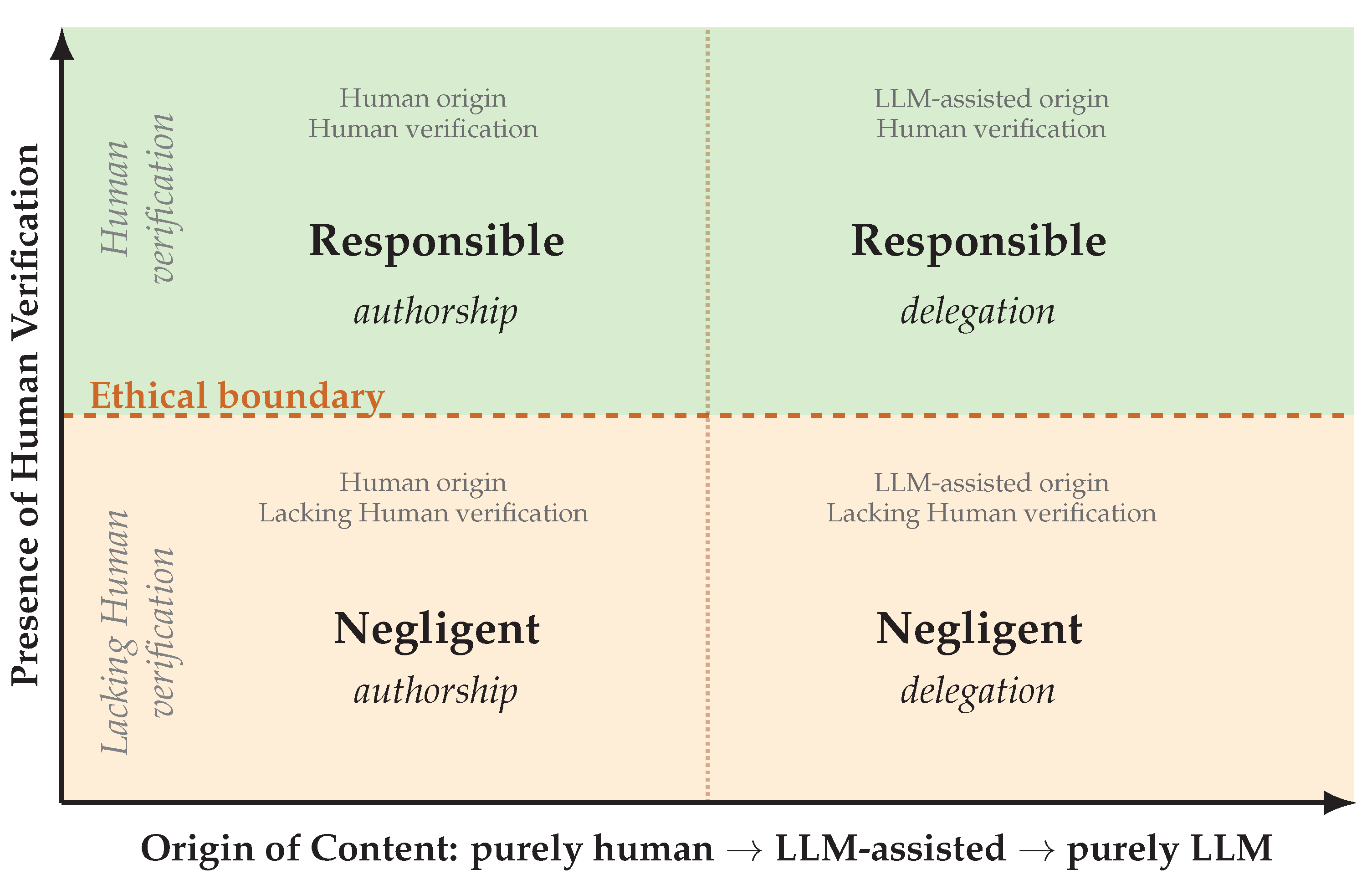

Inferential labor may be distributed across humans and artifacts, while moral authorship remains a human prerogative. To represent origin, define

where

and

encode operationalized measures of contribution, such as token share, time investment, or provenance weights. Thus

denotes purely human origin,

purely machine origin, and intermediate values indicate co-production. Verification remains discrete,

, reflecting the presence or absence of warrant.

Together, these coordinates define a plane on which epistemic and moral status can be visualized (

Figure 1). The horizontal axis represents origin as a continuous variable, while the vertical axis encodes verification as a binary condition. The boundary between responsible and negligent delegation is therefore determined by verification rather than origin.

Epistemic Value of Delegated Reasoning

To integrate epistemic and moral status, define the

epistemic value function

The value of

depends on verification and moral authorship rather than on origin. Maximal epistemic value requires

When either condition fails, epistemic value declines accordingly. In this way, captures the integrity of a statement within a distributed system in which truth and responsibility function as orthogonal yet jointly necessary dimensions.

Aggregating across

yields a system-level measure

with nonnegative weights

reflecting relative salience or impact. High collective integrity is sustained when verified and owned statements dominate the aggregate.

A three-dimensional epistemic state space.

The triplet

induces a state space in which each statement occupies

Here

quantifies human–machine origin,

records verification, and

registers epistemic and moral worth. This triad unifies the ontological (origin), methodological (warrant), and axiological (value) dimensions of delegated cognition. Authorship varies continuously, verification operates discretely, and epistemic value emerges as a smooth resultant of both. Acceptable thresholds for

remain a matter of human judgment, determining when publication or deployment attains epistemic legitimacy.

3.3. The Moral Economy of Peer Review

Peer review constitutes the central institution of epistemic trust in science. It operates as a distributed verification mechanism that links individual reasoning to the collective cognitive system of the scientific community. When authors submit manuscripts—whether human- or machine-assisted—without adequate internal validation, they shift the burden of verification onto unpaid referees. Such displacement disrupts what has been described as the moral economy of science: a network of reciprocal epistemic duties that sustains the credibility of knowledge production.

Formally, let

denote the author’s verification effort and

the expected effort demanded of reviewers. Ethical fairness requires

ensuring that the producer of a claim performs the majority of the epistemic work required to justify it.

Referees act as custodians of collective epistemic integrity rather than as co-authors responsible for unverified reasoning. Submitting unvetted LLM outputs therefore misallocates cognitive and moral labor. Within AI-assisted research, epistemic accountability requires that every claim be traceable to a human act of verification and justification, independent of the computational instruments employed.

Delegation becomes ethically problematic only when it displaces human verification rather than supporting it. The normative distinction lies not between human and artificial reasoning, but between legitimate assistance and abdication of responsibility. Preserving the time and trust of referees forms part of the cooperative duty that allows distributed cognition to remain stable and self-correcting.

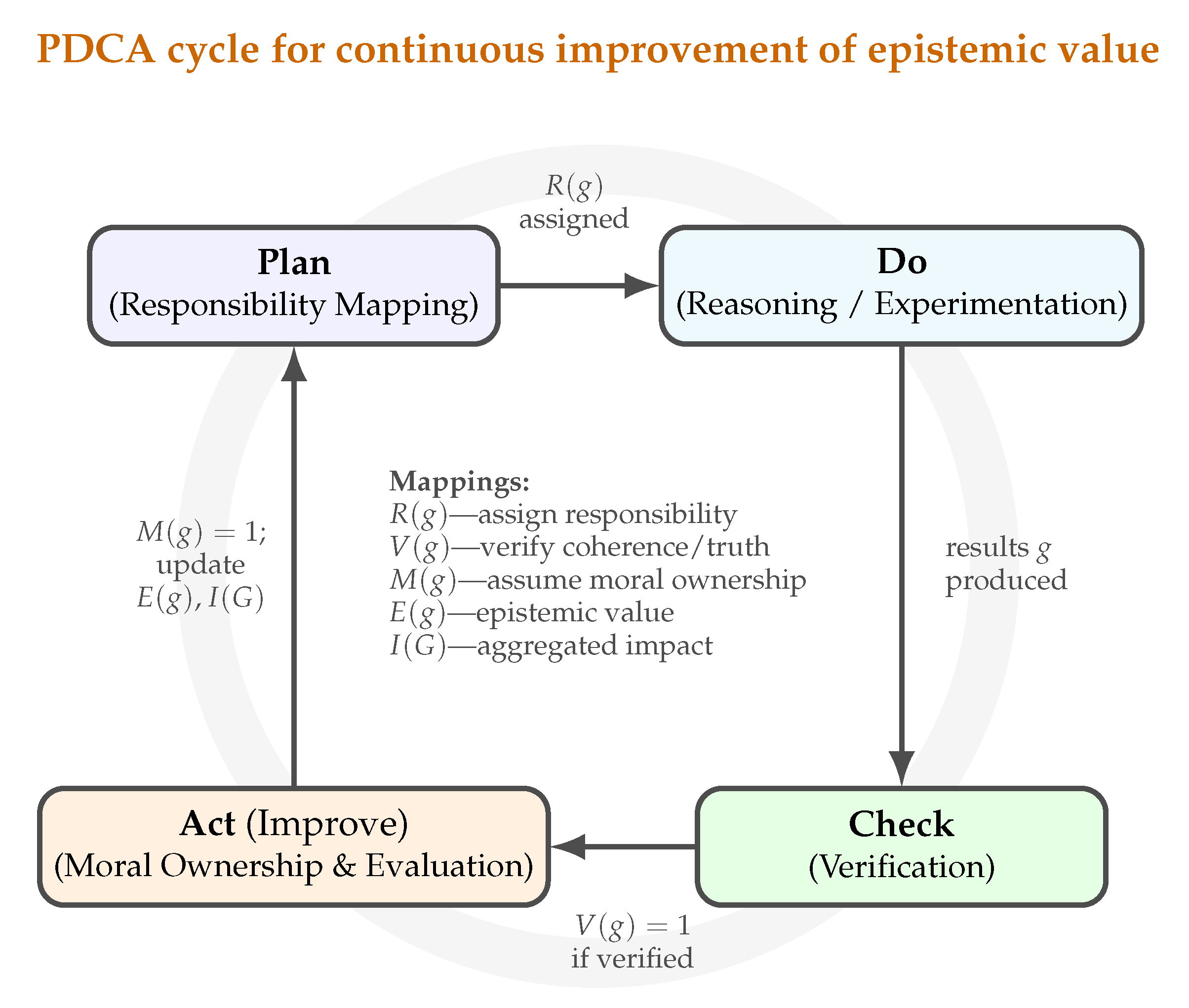

3.4. The Epistemic Value Improvement Loop

The formal framework developed here admits an epistemic interpretation analogous to the

Plan–Do–Check–Act (PDCA) cycle. Tracing its conceptual lineage to Shewhart’s work and to the

Plan–Do–Study–Act formulation articulated by Deming [

9], PDCA later became institutionalized through the ISO 9000 series of standards. The present discussion adopts the PDCA formulation while preserving its original conceptual intent.

Applied to cognition, PDCA functions as an epistemic control loop: a recursive process through which verification, responsibility, and evaluation sustain scientific progress. Each phase finds a direct counterpart in epistemic practice, forming a closed feedback loop that incrementally raises epistemic value (

Figure 2). Through this loop, ethical responsibility becomes an operational mechanism of epistemic improvement, enabling science to refine both its knowledge and the practices through which that knowledge is produced.

4. Future Directions: Toward a Metric of Epistemic Value

The preceding sections delineate the epistemic and moral boundaries of delegated reasoning. A natural next step is the development of a principled, quantitative system for assessing the

epistemic value of scientific contributions. Established citation-based indicators—impact factor, h-index, and related measures—track visibility more reliably than epistemic quality, and their limitations are well documented [

10,

11,

12,

13]. As soon as such indices become institutional targets, they incentivize optimization for attention and status, shifting evaluation away from verification as the core signal of worth. From Merton’s account of communal norms [

14] through Latour’s actor–network perspective [

15] to the Leiden Manifesto’s call for responsible metrics [

12], a consistent orientation emerges: scientific assessment gains traction when it foregrounds epistemic reliability rather than prestige.

The epistemic value function

introduced above provides a conceptual anchor for quantifying integrity and responsibility at the level of individual claims. A quantitative assessment framework can treat

as a

source term contributing to a higher-order measure of verified impact. Let a contribution

consist of

n epistemic elements. Its internal impact can be expressed as

where

encodes contextual importance, including empirical support, theoretical relevance, or disciplinary significance. The resulting score

aggregates the reliability and ethical soundness of individual results into a composite indicator of epistemic coherence.

A next-generation metric can register not only how often a result is cited, but whether it has been verified, replicated, or usefully applied. Positive and negative indicators may be operationalized as follows:

Positive: verified replications, independent implementations, incorporation into standards, patents, or educational materials;

Negative: retractions, failed replications, ethical violations, or documented misuse.

By normalizing these indicators to , an extended metric can couple epistemic and societal domains:

where

denotes an external (societal) signal and

modulates the strength of coupling. Under this formulation,

integrates internal coherence with verified external resonance, aligning truth, responsibility, and demonstrable influence.

A comprehensive audit also requires sensitivity to epistemic decay. Some outputs propagate unverifiable claims, amplify bias, or create downstream harm through uncritical automation. Relevant negative indicators include

retractions or replication failures,

logical inconsistencies or unverifiable references,

evidence of harm from misapplied findings (e.g., unsafe or discriminatory algorithms),

low originality or weak evidential grounding detected by verification tools.

Incorporating such signals allows to move from a local diagnostic of reasoning quality to a systemic measure of epistemic health. LLMs can support estimation by cross-checking citations, detecting inconsistencies, and surfacing risk factors, while moral weighting remains a human decision. Epistemic value emerges when claims are both verified and owned.

Epistemic value admits a natural three-axis description:

- 1.

Internal validity: logical soundness, originality, reproducibility;

- 2.

External impact: verified adoption, including uptake in practice or translation into downstream artifacts;

- 3.

Moral polarity: the balance of beneficial and harmful epistemic effects.

A meaningful metric integrates all three, capturing how knowledge functions and propagates once released into circulation. In practice, such a system can combine

a curated database of verified outcomes, replications, and retractions,

discipline-specific weighting models that reflect heterogeneous epistemic standards, and

uncertainty estimates that express confidence in each data stream.

Auditable AI tools can support this pipeline by extracting evidence of verification, flagging inconsistencies, and tracking positive and negative contributions over time. In this role, LLMs serve as instruments of epistemic transparency: they organize dispersed evidence, maintain provenance, and highlight points where verification is missing or contested. Aggregated information can populate a multidimensional epistemic dashboard whose axes represent internal quality, external influence, and moral polarity, thereby providing a transparent visualization of epistemic performance.

Emerging architectures such as

Real Deep Research (RDR) [

16] embed large models into self-referential research loops that perform literature analysis and hypothesis generation. Under human supervision, these systems already approximate a shift from assistive tooling toward partially autonomous inquiry. In such settings, a rigorous epistemic metric becomes operationally central: it enables internal verification, ranking of outputs by reliability, and prioritization of discoveries with demonstrable benefit. Intermediate hypotheses merit preservation as well, since they often encode latent relations that later crystallize into testable claims.

This trajectory invites an extension of familiar safety intuitions into the epistemic domain: intelligent systems can be guided to refrain from producing or propagating claims with negative epistemic value. Epistemic safety complements physical safety by constraining what a system endorses as knowledge and how it communicates that endorsement. Within such architectures, internal ethical filters govern permissible cognitive states—determining which inferences, beliefs, or outputs are admissible to present—while a complementary principle of positive guarding preserves promising insights for human interpretation and ethical appraisal.

Taken together, these mechanisms articulate preventive and preservative dimensions of epistemic ethics: they limit error propagation while sustaining insight. Future work can therefore focus on formalizing verification-driven metrics, building open epistemic databases, and integrating these components with RDR-like frameworks to support transparent, accountable, and morally grounded machine-assisted discovery.

5. Applied Reflection: Responsible Use of AI in Authorship

The ethical framework developed above can be rendered operational through a concise set of reflective principles for researchers who employ large language models (LLMs) in scientific writing or analysis. The aim is not procedural enforcement but the preservation of epistemic validity and moral accountability when computational systems participate in reasoning. Under this view, responsible authorship is sustained through continuous self-audit: delegation extends cognitive capacity while human responsibility remains fully in force.

5.1. Core Principles for Researchers

Each principle articulates a distinct dimension of epistemic responsibility:

Conceptual Ownership: Define the research problem, hypothesis, or interpretive question. Human authors retain authority over conceptual framing, meaning, and scope.

Intentional Framing of Prompts: Formulate prompts as instructions to a competent collaborator by specifying purpose, constraints, and expected rigor. Prompts express deliberate epistemic intent rather than mechanical task delegation.

Verification and Validation: Independently verify every argument, reference, equation, or dataset generated with LLM support. Machine output attains epistemic standing through human confirmation.

Transparency of Assistance: Explicitly indicate how AI tools were used (e.g., drafting, coding, summarization, translation). Disclosure sustains the integrity of authorship and attribution.

Reference Authenticity: Confirm that each citation corresponds to a real and relevant source that substantiates the claim it supports.

Epistemic Traceability: Maintain a concise record of the principal prompts, responses, and verification actions that shaped the final result.

Authorship Integrity: All listed authors read, understand, and endorse the complete manuscript, including AI-assisted passages.

Moral Accountability: Epistemic responsibility cannot be transferred to a non-intentional system. Human authors remain the sole moral agents of the work.

For every substantive statement

g within a manuscript, the principal investigator should be able to affirm

indicating that each claim has been both verified and humanly owned.

5.2. Positive Example: Responsible Integration

Prompts specify objectives and context (e.g., “revise the introduction for conceptual clarity while preserving technical precision”).

LLM output is reviewed for factual consistency, mathematical correctness, and citation validity.

A brief record of prompts and edits is retained; AI assistance is acknowledged in a disclosure statement.

Human authors supervise all iterations and integrate outputs through interpretive judgment.

Result: the final text exhibits conceptual coherence, verifiable claims, and transparent collaboration. Epistemic integrity is preserved, with and .

5.3. Negative Example: Negligent Delegation

Prompts are vague (e.g., “write a section on how AI improves research quality”) and lack conceptual focus.

Generated text includes fabricated references or incoherent reasoning.

No verification or disclosure occurs prior to submission.

Human oversight is minimal, leaving moral authorship effectively unassigned.

Result: unverifiable content and ethical detachment, with and . Such practice erodes epistemic trust and shifts unacknowledged verification burdens onto peer review.

5.4. Practical Record-Keeping

Consistent with epistemic transparency, only minimal documentation is required:

Verification Log: a brief note indicating what was checked (proofs, data, code) and by whom.

Prompt Archive: a concise list of significant prompts and their verified outputs.

Reference Record: confirmed DOIs or links establishing the validity of each citation.

Statement of AI Involvement: a short acknowledgment describing the tools used and the extent of their contribution.

These practices ensure traceability and reproducibility without imposing bureaucratic overhead. They translate the moral architecture of delegated reasoning into a simple epistemic norm: machines may assist, while humans verify, interpret, and own knowledge.

6. Conclusion

The framework developed in this paper completes a conceptual cycle linking verification, moral authorship, and epistemic responsibility. In the presence of large language models, the scientist’s role does not contract; it acquires additional structure and clarity. Tasks that once demanded extensive technical effort can now be delegated to machines, while the responsibility for directing inquiry, interpreting results, and securing epistemic integrity remains firmly human. Delegation thus sharpens rather than obscures the scientist’s obligation to ensure coherence, transparency, and reliability across the entire cognitive process.

Moral accountability does not diffuse across collaborators, nor does it migrate to computational systems. Although machines can generate fluent and occasionally insightful formulations, intentionality and authorship remain human capacities. What gains prominence under machine assistance is the requirement of traceability: it remains essential to distinguish contributions grounded in human reasoning from those produced through statistical synthesis. Explicit authorship and systematic verification sustain the integrity and moral coherence of scientific knowledge.

The role of referees correspondingly acquires renewed ethical salience. Peer review functions not only as an assessment of correctness but as a form of stewardship over epistemic value. Reviewers evaluate claims independently of whether they emerge from human collaboration or LLM-assisted workflows, thereby reinforcing a moral economy of knowledge suited to large-scale delegation. Authors and reviewers jointly maintain the alignment between truth, responsibility, and public trust.

Delegated reasoning itself follows a familiar logic at an expanded scale. Its epistemic legitimacy rests on verification, while its ethical legitimacy rests on responsible authorship. A verified statement carries the same epistemic standing regardless of origin, whereas moral responsibility for publication and consequence remains exclusively human. As LLMs become embedded in research practice, the preservation of science’s moral economy depends on reaffirming enduring virtues of inquiry: diligence in checking, transparency in attribution, and accountability in judgment.

These commitments condense into a simple operational criterion:

A claim enters the scientific record when it is both verified and ethically owned. This condition expresses continuity between traditional scholarship and computationally assisted research: established norms of authorship extend naturally to new forms of reasoning.

The expanded accessibility enabled by LLMs intensifies the need for vigilance. Rapid access to information amplifies the value of careful verification, as acceleration without scrutiny propagates error alongside insight. Responsible delegation therefore couples technical competence with sustained commitment to epistemic care.

When epistemic value admits both positive and negative contributions—rewarding coherence and truth while registering inconsistency or harm—evaluation itself becomes an ethical instrument. Under such a view, accountability is not imposed externally but embedded within the architecture of discovery, guiding both production and dissemination of knowledge.

Delegated reasoning thus foregrounds the human dimension of artificial intelligence. Every instance of machine-assisted cognition depends on human verification and moral intention. Whether the outcome is a theorem, an argument, or a line of code, epistemic worth arises through verification and moral significance through authorship. Together, these dimensions define a human standard of truth and responsibility for scientific inquiry conducted in the age of artificial reason.

References

- Clark, A.; Chalmers, D.J. The extended mind. Analysis 1998, 58, 10–23. [CrossRef]

- Lakatos, I. Proofs and Refutations: The Logic of Mathematical Discovery; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1976.

- Schlimm, D. Mathematical concepts and investigative practice. In Philosophy of Mathematics: Sociological Aspects and Mathematical Practice; van Kerkhove, B.; Van Bendegem, J.P., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, 2011; pp. 165–189.

- Hutchins, E. Cognition in the Wild; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, 1995.

- Helgesson, G.; Eriksson, S. Plagiarism in research. Medicine, Health Care and Philosophy 2014, 18, 91–101. [CrossRef]

- Strathern, M. Improving ratings: Audit in the British university system. European Review 1997, 5, 305–321.

- Shore, C.; Wright, S. Governing by numbers: Audit culture, rankings and the new world order. Social Anthropology / Anthropologie Sociale 2015, 23, 22–28. [CrossRef]

- Power, M. The Audit Society: Rituals of Verification; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 1997.

- Deming, W.E. Out of the Crisis; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, 1986. Revised edition, 2000.

- Fire, M.; Guestrin, C. Over-optimization of academic publishing metrics: Observing Goodhart’s Law in action. GigaScience 2019, 8, 1–20. Preprint available on arXiv:1809.07841, . [CrossRef]

- Aksnes, D.W.; Langfeldt, L.; Wouters, P. Citations, citation indicators, and research quality: An overview of basic concepts and theories. Sage Open 2019, 9, 1–17.

- Hicks, D.; Wouters, P.; Waltman, L.; de Rijcke, S.; Rafols, I. The Leiden Manifesto for research metrics. Nature 2015, 520, 429–431. [CrossRef]

- Lisciandra, C. Citation metrics: A philosophy of science perspective. Episteme 2025. Forthcoming, Cambridge University Press.

- Merton, R.K. The normative structure of science. In The Sociology of Science: Theoretical and Empirical Investigations; 1942.

- Latour, B. Science in Action: How to Follow Scientists and Engineers Through Society; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, 1987.

- Zou, X.; Ye, J.; Zhang, H.; Xiang, X.; Ding, M.; Yang, Z.; Lee, Y.J.; Tu, Z.; Liu, S.; Wang, X. Real Deep Research for AI, Robotics and Beyond. arXiv preprint arXiv:2510.20809 2025.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).