Submitted:

16 January 2026

Posted:

19 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

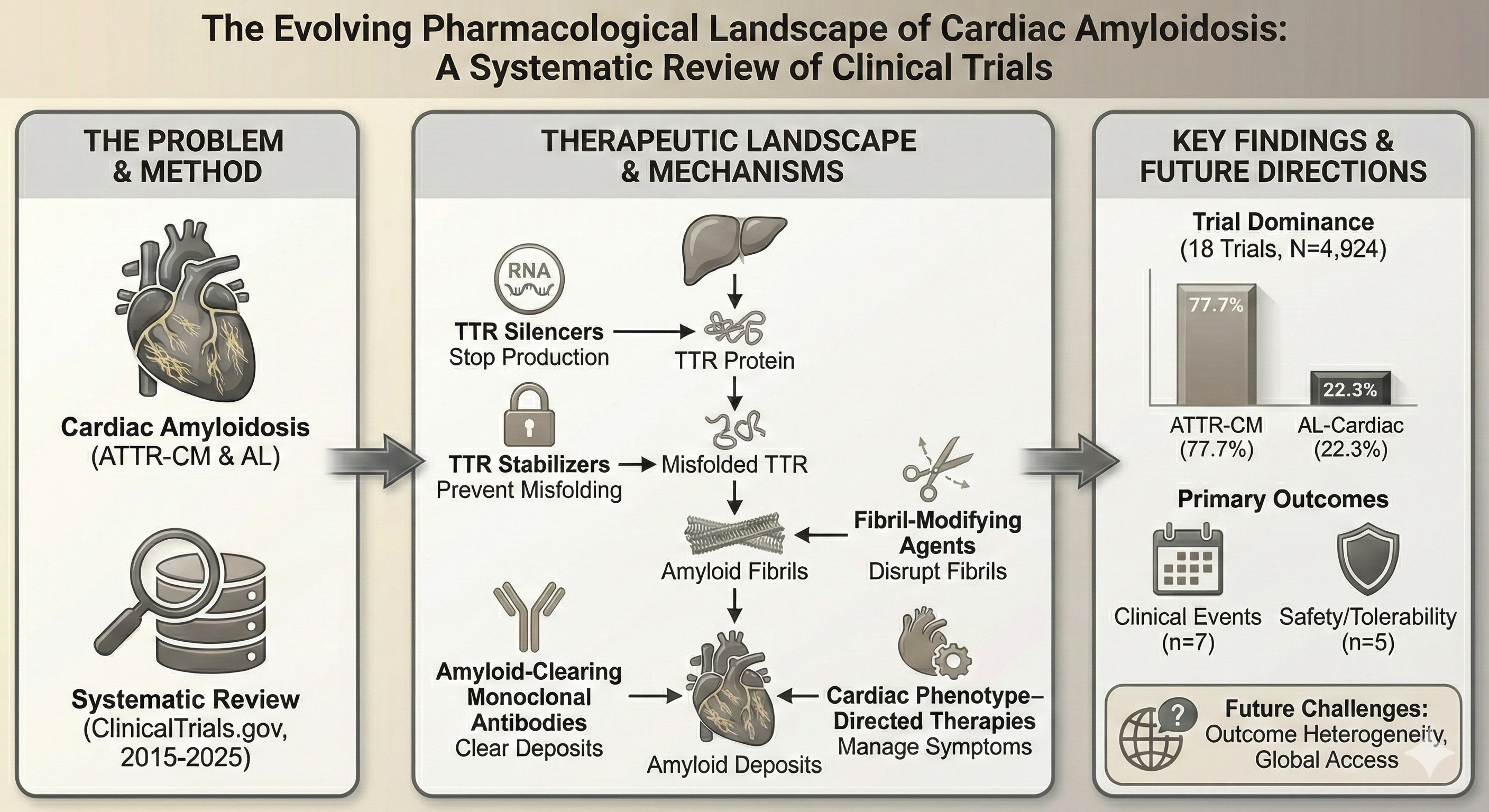

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Definition |

| 6MWD | Six-minute walk distance |

| AL | Light-chain amyloidosis |

| AL-cardiac | Light-chain amyloidosis with cardiac involvement |

| ASO | Antisense oligonucleotide |

| ATTR-CM | Transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy |

| CMR | Cardiac magnetic resonance |

| ECV | Extracellular volume |

| GLS | Global longitudinal strain |

| HF | Heart failure |

| KCCQ | Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire |

| LV | Left ventricular |

| mAb | Monoclonal antibody |

| mRNA | Messenger RNA |

| NCT | National Clinical Trial identifier |

| NT-proBNP | N-terminal pro–B-type natriuretic peptide |

| PCWP | Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure |

| SAE | Serious adverse event |

| siRNA | Small interfering RNA |

| TEAE | Treatment-emergent adverse event |

| TTR | Transthyretin |

References

- Kittleson, M.M.; Maurer, M.S.; Ambardekar, A.V.; Bullock-Palmer, R.P.; Chang, P.P.; Eisen, H.J.; Nair, A.P.; Nativi-Nicolau, J.; Ruberg, F.L.; et al.; American Heart Association Heart; F Cardiac Amyloidosis: Evolving Diagnosis and Management: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2020, 142, e7–e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oladiran, O.D.; Oladunjoye, A.O.; Dhital, R.; Oladunjoye, O.O.; Nwosu, I.; Licata, A. Hospitalization Rates, Prevalence of Cardiovascular Manifestations and Outcomes Associated With Amyloidosis in the United States. Cureus 2021, 13, e14177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, A.; Patel, R.K.; Razvi, Y.; Porcari, A.; Sinagra, G.; Venneri, L.; Bandera, F.; Masi, A.; Williams, G.E.; O’Beara, S.; et al. Impact of Earlier Diagnosis in Cardiac ATTR Amyloidosis Over the Course of 20 Years. Circulation 2022, 146, 1657–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argon, A.; Nart, D.; Yilmazbarbet, F. Cardiac Amyloidosis: Clinical Features, Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Turk Patoloji Derg 2024, 40, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, M.D.; Buxbaum, J.N.; Eisenberg, D.S.; Merlini, G.; Saraiva, M.J.M.; Sekijima, Y.; Sipe, J.D.; Westermark, P. Amyloid nomenclature 2018: recommendations by the International Society of Amyloidosis (ISA) nomenclature committee. Amyloid 2018, 25, 215–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontana, M.; Berk, J.L.; Drachman, B.; Garcia-Pavia, P.; Hanna, M.; Lairez, O.; Witteles, R. Changing Treatment Landscape in Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis. Circ Heart Fail 2025, 18, e012112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fontana, M.; Aimo, A.; Emdin, M.; Porcari, A.; Solomon, S.D.; Hawkins, P.N.; Gillmore, J.D. Transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy: from cause to novel treatments. Eur Heart J 2026, 47, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimza, M.; Vasilakis, G.; Grodin, J.L. Transthyretin Amyloid Cardiomyopathy: The Plot Thickens as Novel Therapies Emerge. US Cardiol 2025, 19, e21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gitt, A.K.; Bueno, H.; Danchin, N.; Fox, K.; Hochadel, M.; Kearney, P.; Maggioni, A.P.; Opolski, G.; Seabra-Gomes, R.; Weidinger, F. The role of cardiac registries in evidence-based medicine. Eur Heart J 2010, 31, 525–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawson, L.P.; Biswas, S.; Lefkovits, J.; Stub, D.; Burchill, L.; Evans, S.M.; Reid, C.; Eccleston, D. Characteristics and Quality of National Cardiac Registries: A Systematic Review. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2021, 14, e007963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, S.N.; Weintraub, W.S. The Role of National Registries in Improving Quality of Care and Outcomes for Cardiovascular Disease. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J 2020, 16, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, M.S.; Schwartz, J.H.; Gundapaneni, B.; Elliott, P.M.; Merlini, G.; Waddington-Cruz, M.; Kristen, A.V.; Grogan, M.; Witteles, R.; Damy, T.; et al. Tafamidis Treatment for Patients with Transthyretin Amyloid Cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med 2018, 379, 1007–1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higaki, J.N.; Chakrabartty, A.; Galant, N.J.; Hadley, K.C.; Hammerson, B.; Nijjar, T.; Torres, R.; Tapia, J.R.; Salmans, J.; Barbour, R.; et al. Novel conformation-specific monoclonal antibodies against amyloidogenic forms of transthyretin. Amyloid 2016, 23, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso, I.; Martins, D.; Ribeiro, T.; Merlini, G.; Saraiva, M.J. Synergy of combined doxycycline/TUDCA treatment in lowering Transthyretin deposition and associated biomarkers: studies in FAP mouse models. J Transl Med 2010, 8, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Pavia, P.; Rapezzi, C.; Adler, Y.; Arad, M.; Basso, C.; Brucato, A.; Burazor, I.; Caforio, A.L.P.; Damy, T.; Eriksson, U.; et al. Diagnosis and treatment of cardiac amyloidosis: a position statement of the ESC Working Group on Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases. Eur Heart J 2021, 42, 1554–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senigarapu, S.; Driscoll, J.J. A review of recent clinical trials to evaluate disease-modifying therapies in the treatment of cardiac amyloidosis. Front Med (Lausanne) 2024, 11, 1477988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oubari, S.; Naser, E.; Papathanasiou, M.; Luedike, P.; Hagenacker, T.; Thimm, A.; Rischpler, C.; Kessler, L.; Kimmich, C.; Hegenbart, U.; et al. Impact of time to diagnosis on Mayo stages, treatment outcome, and survival in patients with AL amyloidosis and cardiac involvement. Eur J Haematol 2021, 107, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poledniczek, M.; Schmid, L.M.; Kronberger, C.; Ermolaev, N.; Rettl, R.; Binder, C.; Camuz Ligios, L.; Eslami, M.; Nitsche, C.; Hengstenberg, C.; et al. Applicability of phase 3 trial selection criteria to real-world transthyretin amyloid cardiomyopathy patients. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 37893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurer, M.S.; Dunnmon, P.; Fontana, M.; Quarta, C.C.; Prasad, K.; Witteles, R.M.; Rapezzi, C.; Signorovitch, J.; Lousada, I.; Merlini, G. Proposed Cardiac End Points for Clinical Trials in Immunoglobulin Light Chain Amyloidosis: Report From the Amyloidosis Forum Cardiac Working Group. Circ Heart Fail 2022, 15, e009038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorbala, S.; Adigun, R.; Alexander, K.M.; Brambatti, M.; Cuddy, S.A.M.; Dispenzieri, A.; Dunnmon, P.; Emdin, M.; Abou Ezzeddine, O.F.; Falk, R.H.; et al. Development of Imaging Endpoints for Clinical Trials in AL and ATTR Amyloidosis: Proceedings of the Amyloidosis Forum. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2025, 18, 602–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, J.; Carpinteiro, A.; Luedike, P.; Buehning, F.; Wernhart, S.; Rassaf, T.; Michel, L. Current Therapies and Future Horizons in Cardiac Amyloidosis Treatment. Curr Heart Fail Rep 2024, 21, 305–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, R.D.; Coriu, D.; Jercan, A.; Badelita, S.; Popescu, B.A.; Damy, T.; Jurcut, R. Progress and challenges in the treatment of cardiac amyloidosis: a review of the literature. ESC Heart Fail 2021, 8, 2380–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein-Merlob, A.F.; Swier, R.; Vucicevic, D. Evolving Strategies in Cardiac Amyloidosis: From Mechanistic Discoveries to Diagnostic and Therapeutic Advances. Cardiol Clin 2025, 43, 93–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez-Lopez, E.; Lopez-Sainz, A.; Garcia-Pavia, P. Diagnosis and Treatment of Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis. Progress and Hope. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2017, 70, 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quarta, C.C.; Solomon, S.D.; Uraizee, I.; Kruger, J.; Longhi, S.; Ferlito, M.; Gagliardi, C.; Milandri, A.; Rapezzi, C.; Falk, R.H. Left ventricular structure and function in transthyretin-related versus light-chain cardiac amyloidosis. Circulation 2014, 129, 1840–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merlini, G.; Bellotti, V. Molecular mechanisms of amyloidosis. N Engl J Med 2003, 349, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.M.; Ramazani, N.; Sodhi, G.; Tak, T. Cardiac Amyloidosis: Tribulations and New Frontiers. J Pers Med 2025, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brownell, D.; Pillai, A.J.; Nair, N. Cardiac Amyloidosis: A Contemporary Review of Medical and Surgical Therapy. Curr Cardiol Rev 2024, 20, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gertz, M.A.; Lacy, M.Q.; Gastineau, D.A.; Inwards, D.J.; Chen, M.G.; Tefferi, A.; Kyle, R.A.; Litzow, M.R. Blood stem cell transplantation as therapy for primary systemic amyloidosis (AL). Bone Marrow Transplant 2000, 26, 963–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanitis, M.; Koch, C.M.; Chan, G.G.; Torres-Arancivia, C.; LaValley, M.P.; Jacobson, D.R.; Berk, J.L.; Connors, L.H.; Ruberg, F.L. Identification of Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis Using Serum Retinol-Binding Protein 4 and a Clinical Prediction Model. JAMA Cardiol 2017, 2, 305–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez Valle, F.; Perez Bocanegra, C. Biomarkers in transthyretin amyloidosis. Present and future. Med Clin (Barc) 2025, 164, 106939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulati, J.S.; Pedretti, R.; Hendren, N.; Kozlitina, J.; Saelices, L.; Roth, L.R.; Grodin, J.L. Biomarkers in Subclinical Transthyretin Cardiac Amyloidosis. Curr Heart Fail Rep 2025, 22, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrysohoou, C.; Panagiotakos, D.; Tsiachris, D.; Dimitriadis, K.; Lazaros, G.; Tsioufis, K.; Stefanadis, C. A simplified cardiac amyloidosis score predicts all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality and morbidity in the general population: the Ikaria Study. Arch Med Sci 2025, 21, 1801–1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willixhofer, R.; Contini, M.; Emdin, M.; Magri, D.; Bonomi, A.; Salvioni, E.; Celeste, F.; Del Torto, A.; Passino, C.; Capelle, C.D.J.; et al. Exercise limitations in amyloid cardiomyopathy assessed by cardiopulmonary exercise testing-A multicentre study. ESC Heart Fail 2025, 12, 1326–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chacko, L.; Karia, N.; Venneri, L.; Bandera, F.; Passo, B.D.; Buonamici, L.; Lazari, J.; Ioannou, A.; Porcari, A.; Patel, R.; et al. Progression of echocardiographic parameters and prognosis in transthyretin cardiac amyloidosis. Eur J Heart Fail 2022, 24, 1700–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| NCT number | Study title | Amyloidosis subtype (ATTR-CM or AL-cardiac) | Intervention | Therapeutic class | Study phase | Enrolment (planned or actual) |

| NCT07213583 | Study of Re-Treatment With ALXN2220 in Patients With ATTR-CM | ATTR-CM | ALXN2220 | Amyloid-clearing monoclonal antibodies | Phase 2 | 35 |

| NCT04512235 | A Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of CAEL-101 in Patients With Mayo Stage IIIa AL Amyloidosis (CARES) | AL-cardiac | CAEL-101 | Amyloid-clearing monoclonal antibodies | Phase 3 | 125 |

| NCT04504825 | A Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of CAEL-101 in Patients With Mayo Stage IIIb AL Amyloidosis (CARES) | AL-cardiac | CAEL-101 | Amyloid-clearing monoclonal antibodies | Phase 3 | 284 |

| NCT04304144 | A Study to Evaluate the Safety and Tolerability of CAEL-101 in Patients With AL Amyloidosis | AL-cardiac | CAEL-101 | Amyloid-clearing monoclonal antibodies | Phase 2 | 25 |

| NCT05633563 | The Effect of Trimetazidine on Mitochondrial Function and Myocardial Performance in ATTR-CM | ATTR-CM | Trimetazidine | Cardiac phenotype–directed therapies in ATTR-CM (non–amyloid-targeting) | Phase 4 | 24 |

| NCT04360434 | First-in-Human Study of NI006 in Patients With ATTR-CM | ATTR-CM | NI006 | Amyloid-clearing monoclonal antibodies | Phase 1 | 46 |

| NCT03481972 | Doxycycline/TUDCA Plus Standard Supportive Therapy Versus Standard Supportive Therapy Alone in Cardiac ATTR Amyloidosis | ATTR-CM | Doxycycline/TUDCA | Amyloid disruptors / fibril-modifying agents | Phase 3 | 102 |

| NCT03458130 | Study of AG10 in Amyloid Cardiomyopathy | ATTR-CM | AG10 | TTR stabilizers | Phase 2 | 49 |

| NCT04843020 | ION-682884 in Patients With TTR Amyloid Cardiomyopathy | ATTR-CM | ION 682884 | TTR silencers (siRNA / antisense oligonucleotides) | Phase 2 | 17 |

| NCT07207811 | CLEOPATTRA Coramitug Study in ATTR-CM | ATTR-CM | Coramitug | Amyloid-clearing monoclonal antibodies | Phase 3 | 1280 |

| NCT06194825 | EPIC-ATTR: Eplontersen in Chinese Subjects With ATTR-CM | ATTR-CM | Eplontersen | TTR silencers (siRNA / antisense oligonucleotides) | Phase 3 | 64 |

| NCT06183931 | Study of ALXN2220 Versus Placebo in Adults With ATTR-CM | ATTR-CM | ALXN2220 | Amyloid-clearing monoclonal antibodies | Phase 3 | 1160 |

| NCT04814186 | Tafamidis in Chinese Participants With ATTR-CM | ATTR-CM | Tafamidis | TTR stabilizers | Phase 3 | 53 |

| NCT04622046 | A Phase 3 Study of ALXN2060 in Japanese Participants With Symptomatic ATTR-CM | ATTR-CM | ALXN2060 | TTR stabilizers | Phase 3 | 25 |

| NCT04136171 | CARDIO-TTRansform: Eplontersen in Participants With ATTR-CM | ATTR-CM | Eplontersen | TTR silencers (siRNA / antisense oligonucleotides) | Phase 3 | 1400 |

| NCT03401372 | BCD With or Without Doxycycline in Mayo Stage II-III AL | AL-cardiac | Doxycycline | Amyloid disruptors / fibril-modifying agents | not reported | not reported |

| NCT05233163 | SGLT2 Inhibitors in Transthyretin Amyloid Cardiomyopathy | ATTR-CM | Empagliflozin | Cardiac phenotype–directed therapies in ATTR-CM (non–amyloid-targeting) | Phase 4 | 15 |

| NCT05951049 | A Study of AT-02 in Subjects With Systemic Amyloidosis | AL-cardiac | AT-02 | Amyloid-clearing monoclonal antibodies | Phase 2 | 120 |

| Drug/agent | Therapeutic class | Number of trials |

| CAEL-101 | Amyloid-clearing monoclonal antibodies | 3 |

| Eplontersen | TTR silencers (siRNA / antisense oligonucleotides) | 3 |

| ALXN2220 | Amyloid-clearing monoclonal antibodies | 2 |

| AG10 (ALXN2060) | TTR stabilizers | 2 |

| Doxycycline | Amyloid disruptors / fibril-modifying agents | 2 |

| NI006 | Amyloid-clearing monoclonal antibodies | 1 |

| Coramitug | Amyloid-clearing monoclonal antibodies | 1 |

| AT-02 | Amyloid-clearing monoclonal antibodies | 1 |

| Tafamidis | TTR stabilizers | 1 |

| Trimetazidine | Cardiac phenotype–directed therapies in ATTR-CM (non–amyloid-targeting) | 1 |

| Empagliflozin | Cardiac phenotype–directed therapies in ATTR-CM (non–amyloid-targeting) | 1 |

| Drug Class | Number of trials (n/N) | Total enrolment | ATTR-CM vs AL-cardiac (counts) | Primary outcome focus (brief) | Typical design/comparator (brief) | Notes (1 line max) |

| TTR stabilizers | 3/18 | 127 | 3 ATTR / 0 AL | Biomarkers/pharmacodynamics; functional/health status | Randomized parallel; placebo | Targets protein tetramer stability to prevent amyloidogenesis. |

| TTR silencers (ASO/siRNA) | 3/18 | 1481 | 3 ATTR / 0 AL | Clinical events; biomarkers/pharmacodynamics | Randomized parallel; placebo | Evaluates reduction in hepatic TTR production via genetic silencing. |

| Amyloid-clearing monoclonal antibodies | 8/18 | 3075 | 4 ATTR / 4 AL | Clinical events; imaging; safety/tolerability | Randomized parallel; placebo | Includes safety-focused study for CAEL-101 and trials for cardiac-staged AL. |

| Amyloid disruptors/fibril-modifying agents | 2/18 | 202 | 1 ATTR / 1 AL | Clinical events | Randomized parallel; standard-of-care | Classified by doxycycline (fibril-modifying) component; background plasma cell therapy SoC. |

| Cardiac phenotype–directed therapies in ATTR-CM (non–amyloid-targeting) | 2/18 | 39 | 2 ATTR / 0 AL | Functional/health status; imaging; safety/tolerability | Randomized crossover; placebo or single group | Focuses on myocardial performance and heart failure symptom management. |

| Outcome domain | Frequency (number of trials) | Example outcomes/measures (brief) |

| Clinical events (mortality/hospitalization) | 7 | All-cause mortality, cardiovascular-related hospitalizations, and progression-free survival. |

| Functional/health status (6MWD/KCCQ) | 2 | Distance walked during the 6-minute walk test (6MWT). |

| Biomarkers/pharmacodynamics (NT-proBNP, TTR levels) | 3 | Percent stabilization of TTR tetramers and reduction in serum TTR concentration. |

| Cardiac imaging/structure (echo/GLS, CMR/ECV/LV mass, scintigraphy) | 2 | Change in myocardial amyloid burden assessed by echocardiography, cardiac magnetic resonance (ECV/LV mass), or nuclear scintigraphy. |

| Safety/tolerability (TEAEs/SAEs) | 5 | Incidence and severity of treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) and serious adverse events (SAEs). |

| Hematologic/organ response (AL-cardiac) | 0 | N/A (Included AL-cardiac trials prioritized clinical events or safety as primary endpoints). |

| Study title | NCT number | Design type | Comparator type |

| Study of Re-Treatment With ALXN2220 in Patients With ATTR-CM | NCT07213583 | single-arm/open-label | none/not reported |

| A Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of CAEL-101 in Patients With Mayo Stage IIIa AL Amyloidosis (CARES) | NCT04512235 | parallel-group placebo-controlled | placebo |

| A Study to Evaluate the Efficacy and Safety of CAEL-101 in Patients With Mayo Stage IIIb AL Amyloidosis (CARES) | NCT04504825 | parallel-group placebo-controlled | placebo |

| A Study to Evaluate the Safety and Tolerability of CAEL-101 in Patients With AL Amyloidosis | NCT04304144 | single-arm/open-label | none/not reported |

| The Effect of Trimetazidine on Mitochondrial Function and Myocardial Performance in ATTR-CM | NCT05633563 | crossover/other | placebo |

| First-in-Human Study of NI006 in Patients With ATTR-CM | NCT04360434 | parallel-group placebo-controlled | placebo |

| Doxycycline and Tauroursodeoxycholic Acid (Doxy/TUDCA) in Cardiac ATTR Amyloidosis | NCT03481972 | parallel-group active-controlled | standard of care (± placebo) |

| Study of AG10 in Amyloid Cardiomyopathy | NCT03458130 | parallel-group placebo-controlled | placebo |

| ION-682884 in Patients With TTR Amyloid Cardiomyopathy | NCT04843020 | single-arm/open-label | none/not reported |

| CLEOPATTRA Coramitug Study in ATTR-CM | NCT07207811 | parallel-group placebo-controlled | placebo |

| EPIC-ATTR: Eplontersen in Chinese Subjects With ATTR-CM | NCT06194825 | parallel-group placebo-controlled | placebo |

| Study of ALXN2220 Versus Placebo in Adults With ATTR-CM | NCT06183931 | parallel-group placebo-controlled | placebo |

| A Study to Assess the Safety and Efficacy Of Tafamidis In Chinese Participants With ATTR-CM | NCT04814186 | single-arm/open-label | none/not reported |

| A Phase 3 Study of ALXN2060 in Japanese Participants With Symptomatic ATTR-CM | NCT04622046 | single-arm/open-label | none/not reported |

| CARDIO-TTRansform: Eplontersen in Participants With ATTR-CM | NCT04136171 | parallel-group placebo-controlled | placebo |

| BCD With or Without Doxycycline in Mayo Stage II-III AL | NCT03401372 | parallel-group active-controlled | standard of care |

| SGLT2 Inhibitors in Transthyretin Amyloid Cardiomyopathy | NCT05233163 | single-arm/open-label | none/not reported |

| A Study of AT-02 in Subjects With Systemic Amyloidosis | NCT05951049 | single-arm/open-label | none/not reported |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).