1. Introduction

Rabies is an acute viral zoonosis that remains almost universally fatal once clinical disease develops, yet it is preventable through well-established medical and veterinary interventions. Globally, the burden of rabies is concentrated in low-and middle-income countries, where dog-mediated transmission accounts for the overwhelming majority of human infections [

1,

2]. The disease is primarily transmitted through bites or scratches from infected dogs, and survival depends entirely on the rapid management of wounds and the timely administration of post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) before symptom onset [

3].

In Ghana, rabies remains a significant public health concern, despite the availability of effective vaccines for both humans and dogs. Domestic dogs constitute the principal reservoir and the dominant source of human exposure, particularly within settings characterized by free-roaming dog populations and limited veterinary oversight [

4,

5,

6]. Sporadic dog vaccination campaigns and case management efforts have been implemented by veterinary and public health authorities; however, these measures have not translated into sustained reductions in risk, and rabies remains endemic across multiple ecological and administrative zones [

7].

Growing evidence indicates that the persistence of rabies cannot be explained solely by logistical or biomedical limitations. Instead, community-level factors including knowledge of rabies, perceptions of exposure risk, and behavioural responses following dog bites play a decisive role in shaping disease outcomes [

8,

9,

10]. In Ghanaian communities, incomplete understanding of rabies transmission routes, underestimation of disease severity, and misconceptions surrounding treatment options have been consistently observed [

6,

11]. These issues are often reinforced by sociocultural norms, financial constraints, and unequal access to health and veterinary services, particularly in rural areas [

12,

13].

Dog vaccination coverage remains central to rabies elimination, yet reported coverage levels in Ghana remain substantially below the threshold required to interrupt transmission within canine populations [

4,

6,

14]. Low participation in vaccination campaigns, weak dog confinement practices, and limited owner engagement diminish the effectiveness of control efforts. Together, these human, animal, and environmental factors highlight the importance of adopting a One Health perspective that explicitly integrates societal dimensions into rabies control strategies [

15,

16].

This study sought to assess societal knowledge of rabies, perceptions of dog-bite risk, health-seeking behaviour following potential exposure, and factors influencing dog vaccination practices in selected communities in Ghana. By examining these determinants within a One Health framework, the study aims to generate evidence to inform context-specific policies and strengthen rabies prevention and control efforts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Study Area

A community-based cross-sectional study was conducted between June to December 2025 in selected districts within the Greater Accra, Ashanti, and Bono East Regions of Ghana. These regions were selected to reflect differences in urbanization, dog ownership patterns, availability of veterinary services, and access to healthcare facilities. Both urban and rural communities were included to capture contextual variability in rabies-related knowledge and behaviour.

2.2. Study Population and Eligibility Criteria

The study population comprised adult residents (≥18 years) who were primarily responsible for the care of at least one domestic dog within their household. Only individuals who had resided in the community for a minimum of six months were eligible to participate. Visitors and individuals unwilling or unable to provide informed consent were excluded.

2.3. Sample Size Determination and Sampling Strategy

Sample size was calculated using a single population proportion formula, assuming a conservative prevalence estimate of 50% for adequate rabies knowledge, a 95% confidence level, and a 5% precision. Allowing for potential non-response, a target sample size of 450 respondents was established.

A multi-stage sampling technique was employed. First, districts within each selected region were purposively identified based on reported dog-bite events. Within each district, communities were randomly selected. Households meeting eligibility criteria were then chosen using systematic sampling, and one eligible respondent per household was interviewed.

2.4. Data Collection Instruments and Procedures

Data were collected through face-to-face interviews using a structured questionnaire developed specifically for this study and informed by previously applied rabies KAP tools in endemic settings [

6,

8,

11]. The questionnaire consisted of five sections:

Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents

Knowledge of rabies transmission, clinical features, prevention, and outcomes

Perceived risk associated with dog bites and rabies infection

Health-seeking behaviour following dog-bite incidents

Dog ownership practices, vaccination history, and barriers to vaccination

To complement quantitative data, focus group discussions (FGDs) were conducted in selected communities to explore contextual beliefs, traditional practices, and perceived challenges related to rabies prevention. Each FGD included 6-8 participants and followed a semi-structured discussion guide.

2.5. Data Management and Analysis

Completed questionnaires were checked for completeness and entered into SPSS version 26 for analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize respondent characteristics and rabies-related knowledge, perceptions, and practices. Composite knowledge scores were generated from responses to key items and categorized as adequate or inadequate. Associations between socio-demographic variables and outcome measures were assessed using chi-square tests and multivariable logistic regression, with statistical significance set at p < 0.05.

Qualitative data from FGDs were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and analysed thematically. Themes were identified inductively and used to contextualize quantitative findings.

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

A total of 450 respondents participated in the survey, representing both urban and rural communities across the study area. The majority were adults aged ≥18 years, with a balanced distribution between sexes. Educational attainment varied, ranging from no formal education to tertiary level, with lower educational attainment more common in rural settings. Dog ownership was reported by a substantial proportion of households, with free-roaming dogs frequently observed in both urban and rural environments, as shown in

Table 1.

3.2. Knowledge of Rabies Transmission and Outcomes

From

Table 2, Most respondents reported prior awareness of rabies as a disease. However, accurate knowledge of transmission pathways and clinical outcomes was limited. Fewer than half correctly identified domestic dogs as the primary source of human rabies transmission, misconceptions regarding transmission via non-bite contact and curability after symptom onset were commonly reported. Knowledge scores were significantly lower among respondents from rural communities and among those with no formal education (p < 0.05).

3.3. Risk Perception and Dog-Bite Management Practices

Table 3 showed that the perceived severity of dog bites varied across respondents. While over half of participants considered dog bites potentially dangerous, a substantial proportion perceived minor bites or scratches as low risk. Following dog bites, first-aid practices differed widely: some respondents reported washing wounds with soap and water, whereas others relied on home remedies or traditional treatments. Less than half of exposed individuals reported seeking formal medical care within 24 h of exposure. Delayed care (more than 24 hours) was more frequent in rural communities than in urban areas (p < 0.05).

3.4. Risk Perception and Health-Seeking Behaviour Following Dog Bites

Among respondents reporting dog-bite exposure, health-seeking behaviour varied by residence (

Figure 1). Approximately one-third of exposed individuals sought medical care within 24 h of the bite episode, with a higher proportion observed among urban respondents compared with rural respondents. Delayed care beyond 24 h was common and significantly more frequent among 102 respondents in rural communities than 60 in urban settings, with the p-value < 0.05. A smaller proportion of respondents reported not seeking any formal medical care following exposure.

3.5. Health-Seeking Behaviour and Use of Post-Exposure Prophylaxis

Among respondents reporting dog-bite exposure, utilization of post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) was inconsistent. Barriers to timely care included limited awareness of the need for PEP, perceived cost, distance to health facilities, and initial reliance on traditional healers. Individuals with higher knowledge scores were significantly more likely to seek prompt medical attention following exposure (p < 0.01), as shown in

Table 3.

3.6. Dog Vaccination Coverage by Residence

Overall, dog vaccination coverage was low across the study population, 140 (31.1%) and differed significantly between urban and rural households (

Figure 2). Urban areas reported higher vaccination coverage 90, compared with rural areas 50. The majority of dogs in rural communities were unvaccinated, corresponding with a higher prevalence of free-roaming ownership practices. These findings indicate insufficient vaccination coverage to interrupt canine rabies transmission, particularly in rural settings.

3.7. Dog Vaccination Coverage and Determinants

Reported dog vaccination coverage was low across the study population and did not reach levels sufficient to interrupt canine rabies transmission, as reported in

Table 4. Vaccination rates were significantly lower in rural households compared to urban households (p < 0.01). Key factors associated with non-vaccination included lack of access to veterinary services, perceived low risk of rabies, and absence of organized mass vaccination campaigns. Free-roaming dog ownership was negatively associated with vaccination status (p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

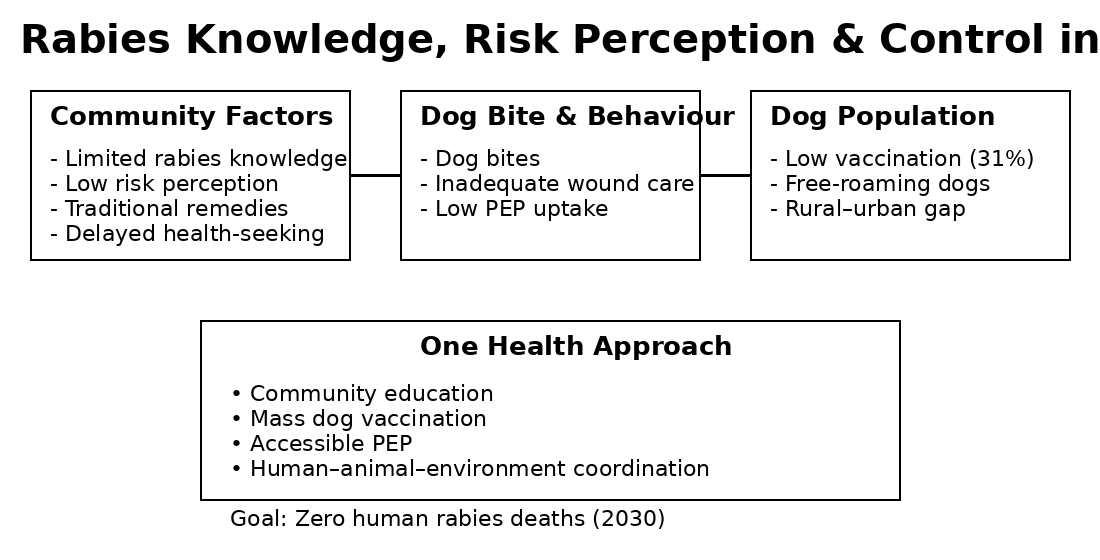

This study demonstrates that rabies prevention in Ghana is constrained less by the absence of biomedical tools and more by societal determinants that shape exposure recognition, response to dog bites, and participation in preventive measures. Although rabies is widely recognized as a disease, substantial gaps persist in accurate knowledge, risk perception, and health-seeking behaviour, which collectively undermine effective rabies control.

4.1. Knowledge Gaps and Misconceptions

While awareness of rabies was moderate among respondents, detailed understanding of transmission pathways, disease progression, and prevention was limited. A considerable proportion of participants failed to consistently identify domestic dogs as the principal source of infection or recognize rabies as invariably fatal once symptoms emerge. Similar patterns have been documented in other rabies-endemic tropical settings, where partial knowledge contributes to delayed or inappropriate responses following exposure [

1,

2,

3]. In Ghana, these gaps are likely amplified by uneven access to formal health education, particularly in rural and peri-urban communities.

The persistence of misconceptions, including beliefs in curative traditional remedies, reflects the interaction between cultural explanatory models of disease and limited biomedical engagement. Such misconceptions are not unique to rabies but are common across neglected zoonotic diseases in tropical regions, where traditional belief systems coexist with formal healthcare structures [

4,

5]. Without targeted risk communication that addresses these beliefs directly, educational interventions may achieve awareness without behavioural change.

4.2. Risk Perception and Response to Dog Bites

Risk perception emerged as a critical mediator between knowledge and action. Although more than half of respondents perceived dog bites as potentially dangerous, this perception did not consistently translate into timely medical care. The normalization of dog bites, particularly in settings with high dog-human interaction, appears to reduce perceived urgency and contributes to delayed health-seeking behaviour. Comparable findings have been reported across Africa and Asia, where familiarity with dogs often leads to underestimation of rabies risk [

6,

7].

The frequent reliance on home-based wound care and traditional treatments following dog bites highlights a significant gap in rabies prevention pathways. These practices delay access to post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) and increase the likelihood of fatal outcomes. In tropical disease contexts, such delays are well recognized contributors to preventable mortality, particularly for diseases where early intervention is essential [

8].

4.3. Dog Vaccination Practices and Barriers

Dog vaccination coverage observed in this study was markedly below the threshold required to interrupt canine rabies transmission. Low uptake was particularly evident in rural communities, where access to veterinary services is limited and the perceived value of vaccination is low. Free-roaming dog populations further complicate vaccination efforts, as unrestrained dogs are difficult to capture and owners often feel limited responsibility for collective herd immunity.

These findings are consistent with previous reports from Ghana and other rabies-endemic regions, which document persistent challenges in achieving and sustaining adequate canine vaccination coverage [

9,

10,

11]. In tropical settings, dog vaccination programs that rely solely on owner initiative or cost recovery mechanisms have repeatedly failed to achieve sufficient coverage. This underscores the need for publicly funded, community-based vaccination strategies integrated into broader public health programming.

4.4. Implications for One Health and Rabies Control

The findings reinforce rabies as a paradigmatic One Health disease, situated at the intersection of human behaviour, animal management, and health system capacity. Fragmented approaches that address only one domain, such as human PEP provision without dog vaccination or education without service accessibility are unlikely to succeed.

For tropical countries such as Ghana, effective rabies control requires synchronizing community education, accessible PEP, mass dog vaccination, and strengthened surveillance. Importantly, interventions must be designed with an understanding of local sociocultural contexts. Experiences from successful rabies control programs in comparable tropical settings demonstrate that community engagement, political commitment, and sustained intersectoral collaboration are key determinants of impact [

12,

13,

14].

4.5. Public Health Significance

Rabies remains one of the most preventable causes of death among neglected tropical zoonoses. The continued occurrence of rabies deaths in Ghana represents not only a health system failure but also a missed opportunity for integrating social science into tropical disease control. Addressing the societal drivers identified in this study could substantially reduce rabies incidence while strengthening broader zoonotic disease preparedness.

5. Conclusions

Rabies in Ghana persists not because of absent vaccines, but because social and behavioural factors impede their effective use. This study shows that incomplete knowledge, underestimation of bite-related risk, reliance on traditional remedies, and low dog-vaccination coverage act together to sustain transmission. Addressing these drivers requires a One Health approach that couples community-centred risk communication with readily accessible PEP and sustained, equitable mass dog-vaccination campaigns. Strengthened intersectoral coordination and investments targeted at rural and underserved populations are critical to translate awareness into protective action. Aligning national efforts with the WHO’s Zero by 30 framework prioritizing coordinated vaccination, PEP access, and context-specific community engagement remains vital to achieving elimination of dog-mediated human rabies deaths in Ghana by 2030.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

Preprints.org, Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Author Contributions

PKD: Conceptualization; Methodology; Investigation; Project Administration; Data Curation; Writing – Original Draft. NYA-B: Methodology; Data Collection; Investigation; Writing – Review & Editing. RED: Methodology; Formal Analysis; Validation; Writing – Review & Editing. SAS & EO: Formal Analysis; Supervision; Validation; Writing – Review & Editing. DK: Resources; Literature Review; Writing – Review & Editing. DN: Conceptualization; Investigation; Visualization; Writing – Review & Editing. PE: Investigation; Supervision; Data Collection; Resources; Writing – Review & Editing. HD-F: Data Interpretation; Validation; Writing – Original Draft, Review & Editing. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval for this study was formally waived by the Office of the Regional Veterinary Officer, Bono East Region, Ghana, acting under the mandate of the Veterinary Services Directorate. The waiver was granted because the study involved non-invasive, questionnaire-based interviews and focus group discussions with adult participants, did not include any clinical or experimental procedures, did not involve biological sample collection, and posed no more than minimal risk to participants. The study was reviewed and determined to fall within routine public health and veterinary surveillance and community engagement activities, for which formal institutional ethics committee approval is not required under applicable local regulations and professional guidelines.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study before data collection. Participation was voluntary, and respondents were provided with a clear explanation of the study objectives, procedures, potential risks, and benefits in a language they understood. Verbal informed consent was deemed appropriate due to the non-invasive, questionnaire-based nature of the study and the absence of any clinical procedures or collection of biological samples. Participants were assured of confidentiality and anonymity, and no personally identifiable information was recorded. All participants retained the right to decline participation or withdraw from the study at any stage without any consequences.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are publicly available in the Mendeley Data repository: Dwaah, Prince Kyere; Awauh-Boateng, Nana Yaa; Squire, Sylvia Afriyie; Osei, Ernest; Kando, David; Dunu, Rogermilla Enam; Nartey, Daniel; Djang-Fordjour, Helen; Edze, Patience (2026).

“Societal Knowledge, Risk Perception, and Health-Seeking Behaviour toward Rabies in Ghana: Implications for One Health Policy and Dog Vaccination Coverage”, Mendeley Data, V1.

https://doi.org/10.17632/29ff5vnkzt.1.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely acknowledge the study participants and community members for their cooperation and willingness to share their experiences. We also appreciate the support of local veterinary and public health officers who facilitated community engagement during data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CSIR |

Council for Scientific and Industrial Research. |

| FAO |

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations |

| FGD |

Focus Group Discussion |

| FGDs |

Focus Group Discussions |

| GHS |

Ghana Health Service |

| KAP |

Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices |

| MMWR |

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report |

| PEP |

Post-Exposure Prophylaxis |

| SPSS |

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| UNICEF |

United Nations Children’s Fund |

| WHO |

World Health Organization |

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Expert Consultation on Rabies: Third Report. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/272364.

- Hampson, Katie; Coudeville, Laurence; Lembo, Tiziana; Sambo, Maganga; Kieffer, Axel; Attlan, Mathieu; Barrat, Jacqueline; Blanton, Jesse D.; Briggs, Deborah J.; Cleaveland, Sarah; Costa, Peter; Freuling, Conrad; Hiby, Lex; Knopf, Lise; Leanes, Fernanda; Meslin, François-Xavier; Metlin, Andrey; Miranda, Mary Elizabeth; Müller, Thomas; Nel, Louis; Recuenco, Sergio; Rupprecht, Charles E.; Schumacher, Christine; Taylor, Louise; Vigilato, Marco A.N.; Zinsstag, Jakob. Estimating the Global Burden of Endemic Canine Rabies. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2015, 9, e0003709. [CrossRef]

- Rupprecht, Charles E.; Briggs, Deborah; Brown, Catherine M.; Franka, Richard; Katz, Susan L.; Kerr, H. Dean; Lett, Sarah M.; Levis, Ronald; Meltzer, Martin I.; Schaffner, William; Cieslak, Paul R.; Krebs, John W.; Hanlon, Cathleen A. Use of a Reduced (4-Dose) Vaccine Schedule for Postexposure Prophylaxis to Prevent Human Rabies. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2010, 59, 1–9. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5902a1.htm.

- Tasiame, Wisdom; Mani, R.S.; Baidoe-Ansah, Daniel; Vaidya, Shilpa A.; Bonney, Joseph H.K.; Yeboah, Eric; Kasanga, Charles J.; Odoom, Samuel; Nartey, Nicholas; Addo, Kofi K. Dog Rabies in Ghana: A Retrospective Review of Laboratory Data (2008–2015). Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 2019, 4, 82. [CrossRef]

- Dodet, Bernard; Goswami, Aparna; Gunasekera, Anura; de Guzman, Fidel; Jamali, Shahnaz; Montalban, Carmelita; Briggs, Deborah J. Rabies Awareness in Eight Asian Countries. Vaccine 2008, 26, 6344–6348. [CrossRef]

- Amegashie, Emmanuel A.; Owusu, Michael; Tasiame, Wisdom; Addo, Kofi K. Community Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Regarding Rabies in Southern Ghana. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2021, 110, 289–295. [CrossRef]

- Banyard, Ashley C.; Horton, Daniel L.; Freuling, Conrad; Müller, Thomas; Fooks, Anthony R. Control and Prevention of Canine Rabies: The Need for Building Laboratory-Based Surveillance Capacity. Antiviral Research 2013, 98, 357–364. [CrossRef]

- Sambo, Maganga; Lembo, Tiziana; Cleaveland, Sarah; Ferguson, Heather M.; Sikana, Lawrence; Simon, Chazaya; Urassa, Helena; Hampson, Katie. Knowledge, Attitudes and Practices about Rabies Prevention and Control: A Community Survey in Tanzania. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2014, 8, e3310. [CrossRef]

- Cleaveland, Sarah; Kaare, Magai; Knobel, Darryn; Laurenson, M. Kate. Canine Vaccination-Providing Broader Benefits for Disease Control. Veterinary Microbiology 2006, 117, 43–50. [CrossRef]

- Knobel, Darryn L.; Cleaveland, Sarah; Coleman, Peter G.; Fèvre, Eric M.; Meltzer, Martin I.; Miranda, Mary Elizabeth G.; Shaw, Alison; Zinsstag, Jakob; Meslin, François-Xavier. Re-Evaluating the Burden of Rabies in Africa and Asia. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 2005, 83, 360–368. Available online: https://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/83/5/knobel.pdf.

- Masthi, Narayana R.R.; Pruthvishree, Basappa S.; Anandaiah, Mahadevaiah; Channabasappa, Gururaj; Jayanth, S. H.; Narayana, D.H.A. Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Regarding Rabies among Dog Owners in Rural India. International Journal of Community Medicine and Public Health 2017, 4, 2251–2257. [CrossRef]

- Zinsstag, Jakob; Schelling, Esther; Waltner-Toews, David; Tanner, Marcel. From “One Medicine” to “One Health” and Systemic Approaches to Health and Well-Being. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 2011, 101, 148–156. [CrossRef]

- Lembo, Tiziana; Attlan, Mathieu; Bourhy, Hervé; Cleaveland, Sarah; Costa, Peter; de Balogh, Katinka; Dodet, Bernard; Fooks, Anthony R.; Hiby, Lex; Leanes, Fernanda; Meslin, François-Xavier; Miranda, Mary Elizabeth; Müller, Thomas; Nel, Louis; Rupprecht, Charles E.; Schumacher, Christine; Taylor, Louise; Vigilato, Marco A.N.; Zinsstag, Jakob. Renewed Global Partnerships and Redesigned Roadmaps for Rabies Prevention and Control. Veterinary Medicine International 2011, 2011, 923149. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; World Organisation for Animal Health; United Nations Children’s Fund. United Against Rabies: Zero by 30 Global Strategic Plan to End Human Deaths from Dog-Mediated Rabies by 2030. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-CDS-NTD-NZD-2018.04.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations; World Health Organization; World Organisation for Animal Health. Taking a Multisectoral, One Health Approach: A Tripartite Guide to Addressing Zoonotic Diseases. FAO, Rome, Italy, 2019. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/ca2942en/ca2942en.pdf.

- Taylor, Louise H.; Latham, Sarah M.; Woolhouse, Mark E.J. Risk Factors for Human Disease Emergence. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2001, 356, 983–989. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).