1. Introduction

Periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) is a serious complication of total joint arthroplasty (TJA), affecting approximately 1–2% of primary joint replacements [

1] and representing one of the leading causes of revision surgery [

2,

3]. As the number of TJAs continues to rise, the incidence of revision surgeries due to PJI is expected to increase correspondingly, imposing a growing burden on healthcare systems and negatively affecting patient outcomes [

4].

Missed or delayed diagnosis of PJI can result in failed aseptic revisions, multiple subsequent surgeries, prolonged antibiotic use, and extended hospital stays [

3]. Conversely, overdiagnosis may lead to unnecessary revision procedures and antibiotic therapies. Accurate diagnosis of PJI is essential to guide appropriate treatment decisions and early detection helps to optimize patient selection for less invasive management strategies, such as debridement, antimicrobial therapy, and implant retention (DAIR) [

5].

Over the past decade, efforts to standardize the diagnosis of PJI have led to the development of several criteria-based systems, including those proposed by the Musculoskeletal Infection Society (MSIS) [

6], the International Consensus Meeting (ICM) [

7], the European Bone and Joint Infection Society (EBJIS) [

8], and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) [

9]. These systems integrate clinical findings and laboratory biomarkers to classify PJI and have greatly improved standardization in research. However, challenges persist in applying these criteria consistently in clinical practice [

10,

11]. A particular difficulty arises in inconclusive or borderline cases, often associated with culture-negative infections, where diagnostic ambiguity increases the risk of both overdiagnosis and underdiagnosis [

12].

Given the critical importance of timely and accurate PJI diagnosis, and the limitations of current criteria-based systems, there is growing interest in exploring artificial intelligence–driven approaches [

13]. Parr et al. previously developed the SynTuition™ Score (hereafter also referred to as SynTuition), a validated machine learning–based probability score for PJI diagnosis [

14].

The primary aim of this study was to evaluate the clinical impact of SynTuition. SynTuition was compared against physician diagnoses of PJI consistent with their routine clinical practice, utilizing the current standard of care (SOC). Two primary outcomes were assessed in this comparison: the reduction in diagnostic uncertainty and the level of agreement with a widely accepted, expert-endorsed framework. Clinical utility was evaluated using decision curve analysis, and the economic impact was assessed using a decision-analytic model.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Clinical Vignettes

In this retrospective study, secondary analysis of a survey study was performed to evaluate the clinical impact of SynTuition. In a previous study, Deirmengian et al. created 277 clinical vignettes using data collected from a multi-institutional cohort, audited by a contracted research organization [

10,

15]. Each vignette included clinical information such as patient age, sex, joint (hip or knee), laterality, concurrent antibiotic use, and comorbidities. Preoperative serum and synovial fluid (SF) biomarkers reflected those obtained as part of routine clinical evaluation and included erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), synovial fluid white blood cell count (SF-WBC), synovial fluid polymorphonuclear percentage (SF-PMN%), and synovial fluid culture results. Each vignette also included post-operative results, including tissue culture and histology, but these were not available in the physician-facing vignettes to enable assessment of real, clinical preoperative decision-making. Synovial fluid red blood cells (SF-RBC) and alpha-defensin (AD) results were also available but not included in the physician-facing vignettes, as these biomarkers are not part of the 2013 MSIS definition of PJI used in the original survey study [

10].

Deirmengian et al. assigned a clinical reference diagnosis based on the 2013 MSIS definition of PJI. This diagnosis was adjudicated by a panel of three experts until consensus on a definitive classification was reached for each patient. Throughout this manuscript, this adjudicated 2013 MSIS–based classification is referred to as the clinical diagnosis and is used as the primary ground-truth label, as it represents the best available clinical truth in the absence of a gold standard.

To provide an updated benchmark, each vignette was additionally classified according to the 2018 ICM criteria for PJI. This classification was based on both preoperative and postoperative data to align with the most widely adopted, expert consensus-based framework for PJI diagnosis in the United States. Three vignettes were excluded due to insufficient preoperative minor criteria, leaving 274 vignettes for inclusion. Of these, 47 met the 2018 ICM definition of PJI, 197 were aseptic, and 30 were classified as inconclusive.

Table 1.

Distribution of clinical vignettes and PJI classification according to the clinical diagnosis and 2018 ICM criteria.

Table 1.

Distribution of clinical vignettes and PJI classification according to the clinical diagnosis and 2018 ICM criteria.

| Diagnosis |

Clinical diagnosis |

2018 ICM |

| PJI |

42 (15.3%) |

47 (17.2%) |

| Aseptic |

232 (84.7%) |

197 (71.9%) |

| Inconclusive |

- |

30 (10.9%) |

2.2. Physician Survey

The 12 physicians who participated in the survey study included four academic arthroplasty surgeons (AS), four community arthroplasty surgeons (CS), and four infectious disease specialists (ID). Each physician reviewed the clinical vignettes and integrated the available laboratory and clinical information to diagnose PJI in a manner consistent with their routine clinical practice, representing the current SOC for PJI workup.

Physician performance was assessed in two stages. In Stage I, physicians assigned each vignette a diagnosis of PJI, aseptic, or undecided. This allowed the authors to quantify the proportion of initially uncertain diagnoses and to evaluate interobserver agreement. In Stage II, physicians reevaluated only the cases they had previously labeled as undecided and were required to select either PJI or aseptic, ensuring that each vignette received a definitive diagnosis.

2.3. SynTuition Score

A SynTuition Score was calculated for each of the 274 clinical vignettes included in this study. The SynTuition model relies on 11 SF biomarkers: two specimen-integrity markers (absorbance at 280 nm wavelength [A280] and SF-RBC); three general inflammatory markers (SF-WBC, SF-PMN%, and synovial fluid CRP [SF-CRP]); one PJI-specific host-response marker (AD); and five direct microbial antigen detection markers (Staphylococcus targets [SPA and SPB], Enterococcus target [EF], Candida target [CP], and Cutibacterium acnes target [PAC]).

Only four of the 11 SF biomarkers, SF-PMN%, SF-WBC, AD, and SF-RBC, were available through the clinical vignettes. Of the 274 vignettes, 62% contained all four biomarkers, 97% contained at least three, and 99% contained at least two. To enable generation of SynTuition Scores for all vignettes, missing biomarkers were imputed using summary statistics derived from the original SynTuition training cohort [

14]. When available, serum CRP values (present in 86.9% of cases) were substituted for SF-CRP, providing more informative input than assigning a fixed imputed value. Good correlation between serum CRP and SF-CRP has been observed in literature [

16], whilst the relatively low sensitivity of SF-CRP within the SynTuition model suggests only large deviations from expected baseline values would meaningfully influence the model output [

14].

Table 2 summarizes biomarker availability across all vignettes and the imputation values used for missing biomarkers.

The SynTuition Score is an integer between 0 and 100, reflective of the probability of PJI. A score above 80 indicates a high probability of PJI, and a score below 20 indicates a low probability of PJI (aseptic). Scores between 20 and 80 are considered equivocal (undecided) [

14]. For comparison with physician survey results, equivocal SynTuition scores were reclassified as PJI when equal or greater than 20 and as aseptic when less than 20, reflecting the threshold most likely used to guide clinical decision-making when a definitive diagnosis is required. An important property of the SynTuition model is that it does not incorporate culture results and can be evaluated solely from SF biomarker results. Evaluation of the SynTuition score was performed using Python 3.10 and scikit-learn 1.6.1.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses and visualizations were performed in Python 3.10. Agreement between the clinical diagnosis and the physician groups was evaluated using overall percent agreement (OPA), positive percent agreement (PPA), and negative percent agreement (NPA) [

17]. Gwet’s AC1 was used as an additional metric to account for chance agreement [

18]. When comparing groups of physicians, pooled estimates were used. Confidence intervals for OPA, PPA, and NPA were calculated using the Wilson method [

19]. Confidence intervals for Gwet’s AC1 were obtained via bootstrap resampling [

20]. Decision curve analysis was used to illustrate the clinical utility of SynTuition when compared against the different physician groups [

21].

2.5. Economic Impact

A decision-analytic model simulated a hypothetical cohort of 1,000 suspected PJI cases. The costs of misdiagnosis were compared between the physician group, representing current SOC, and the SynTuition score. For the simulation, the prevalence was set according to the study disease prevalence of 15.3% (

Table 1), resulting in 153 PJI and 847 aseptic cases. The total number of simulated false-negative (FN) cases was calculated from the number of PJI cases and the PPA, where

The number of simulated false-positive (FP) cases was calculated from the number of aseptic cases and the NPA, where

The PPA and NPA for the physician group (SOC) were based on pooled results across all 12 participants in the physician survey study when compared against the clinical diagnosis.

The economic impact of a false-negative diagnosis was estimated using a scenario-based model reflecting two plausible downstream clinical pathways following an incorrect PJI negative result. To avoid reliance on variable or site-specific clinical distributions, the model assumes an equal probability of patients entering either pathway. In the first pathway, patients undergo additional nonoperative diagnostic evaluation, including joint aspiration, laboratory testing, and follow-up assessment. U.S. national price transparency data estimate the mean cost of a repeat diagnostic episode at approximately

$1,000, with a reported range of

$500 to

$2,000 [

22]. In the second pathway, delayed recognition of infection leads to operative management. As reported by Okafor et al., misdiagnosed patients commonly undergo an initial aseptic revision followed by a two-stage septic revision, resulting in a combined mean procedural cost of

$123,750 [

23]. Applying equal weighting to these pathways (0.50 ×

$1,000 and 0.50 ×

$123,750) yields an expected false-negative cost of

$62,375 per case.

The cost of a false-positive result was modeled as the cost of an unnecessary two-stage septic revision arthroplasty, estimated at

$75,000 based on published U.S. revision cost analyses [

23,

24].

3. Results

3.1. Stage I Survey Results

Table 3 shows the distribution of PJI, aseptic, and undecided diagnoses based on Stage I of the physician survey. Of particular interest is the frequency of undecided diagnoses across different diagnostic methods and physician groups.

The 2018 ICM criteria classified 10.9% of cases as inconclusive, which aligns closely with existing literature [

25]. The rate of undecided diagnoses varied widely among physicians, ranging from 5.1% to 43.4%, reflecting the high level of uncertainty with the current standard of care. As previously reported, the level of uncertainty is influenced by physician experience. Academic surgeons, who are more familiar with PJI scoring systems, tend to have a lower indecision rate compared to community surgeons and ID physicians [

10].

Due to the discriminative nature of the SynTuition algorithm, the proportion of uncertain results was significantly reduced to 0.4%. A similarly low rate of equivocal results has been previously reported in a large validation dataset [

14].

Table 3.

Distribution of PJI, aseptic, and undecided diagnoses across diagnostic methods and physicians.

Table 3.

Distribution of PJI, aseptic, and undecided diagnoses across diagnostic methods and physicians.

| Diagnostic method / physician |

PJI, n (%) |

Aseptic, n (%) |

Undecided, n (%) |

| Clinical diagnosis |

42 (15.3%) |

232 (84.7%) |

- |

| 2018 ICM |

47 (17.2%) |

197 (71.9%) |

30 (10.9%) |

| SynTuition Score |

46 (16.8%) |

227 (82.8%) |

1 (0.4%) |

| All physicians |

597 (18.2%) |

1,937 (58.9%) |

754 (22.9%) |

| Academic surgeons |

172 (15.7%) |

751 (68.6%) |

173 (15.8%) |

| AS1 |

41 (15.0%) |

191 (69.7%) |

42 (15.3%) |

| AS2 |

49 (17.9%) |

211 (77.0%) |

14 (5.1%) |

| AS3 |

35 (12.8%) |

223 (81.4%) |

16 (5.8%) |

| AS4 |

47 (17.2%) |

126 (46.0%) |

101 (36.9%) |

| Community surgeons |

220 (20.1%) |

563 (51.4%) |

313 (28.6%) |

| CS1 |

67 (24.5%) |

150 (54.7%) |

57 (20.8%) |

| CS2 |

44 (16.1%) |

170 (62.0%) |

60 (21.9%) |

| CS3 |

42 (15.3%) |

141 (51.5%) |

91 (33.2%) |

| CS4 |

67 (24.5%) |

102 (37.2%) |

105 (38.3%) |

| ID physicians |

205 (18.7%) |

623 (56.9%) |

268 (24.5%) |

| ID1 |

47 (17.2%) |

176 (64.2%) |

51 (18.6%) |

| ID2 |

40 (14.6%) |

115 (42.0%) |

119 (43.4%) |

| ID3 |

62 (22.6%) |

184 (67.2%) |

28 (10.2%) |

| ID4 |

56 (20.4%) |

148 (54.0%) |

70 (25.5%) |

3.2. Stage II Survey Results

Table 4 shows the distribution of PJI and aseptic diagnoses based on Stage II of the physician survey, in which all diagnostic methods and physicians were required to provide a definitive diagnosis. According to the clinical diagnosis, the prevalence of PJI across all 274 vignettes was 15.3%. Physicians consistently overestimated this prevalence, with an overall rate of 24.0%, suggesting that when required to make a definitive diagnosis, the current SOC tends to bias toward over-diagnosing PJI.

The agreement between each diagnostic method and the clinical diagnosis is provided in

Table 5.

The SynTuition score demonstrated an OPA comparable to the academic surgeon group. Relative to the physicians using current standard of care, SynTuition showed higher agreement with an OPA of 96.0% and Gwet’s AC1 of 0.94 compared with 90.8% and 0.87, respectively.

While the NPA for SynTuition was higher than the current standard of care, at 96.6% compared to 89.4%, the PPA was lower (92.9% vs. 98.4%), indicating the presence of false-negative results relative to clinical diagnosis. These discrepant cases, with a select set of biomarkers and clinical information, were summarized in

Table 6. Among these, FN-001 and FN-002 appear to represent true false-negative results, given their positive synovial fluid and tissue culture findings. SynTuition does not incorporate culture results; it is solely driven by the preoperative biomarkers. FN-001 has an extremely low SF-WBC, driving a low SynTuition Score, whilst FN-002 is predominantly driven by an elevated CRP, known to be a relatively insensitive feature in the SynTuition model [

14]. FN-003 is culture-negative and less concretely PJI with a high SF-RBC, raising the possibility of blood contamination in the SF, thus responsible for a low SynTuition Score.

Although these three cases lowered the SynTuition PPA, one is borderline or debatable with a culture-negative result and may even highlight the strengths of a machine-learning approach that incorporates specimen integrity biomarkers [

14]. Taken together, the performance of SynTuition remains credible given the imperfections of the clinical diagnosis being used.

3.3. 2018 ICM Inconclusive Cohort

Of particular interest is the performance of the diagnostic methods and physician groups in inconclusive or borderline cases, which are frequently associated with culture-negative results. Among the 30 cases classified as inconclusive by the 2018 ICM criteria (

Table 1), 29 underwent synovial fluid culture and were all culture negative. All 30 cases were aseptic according to the clinical diagnosis.

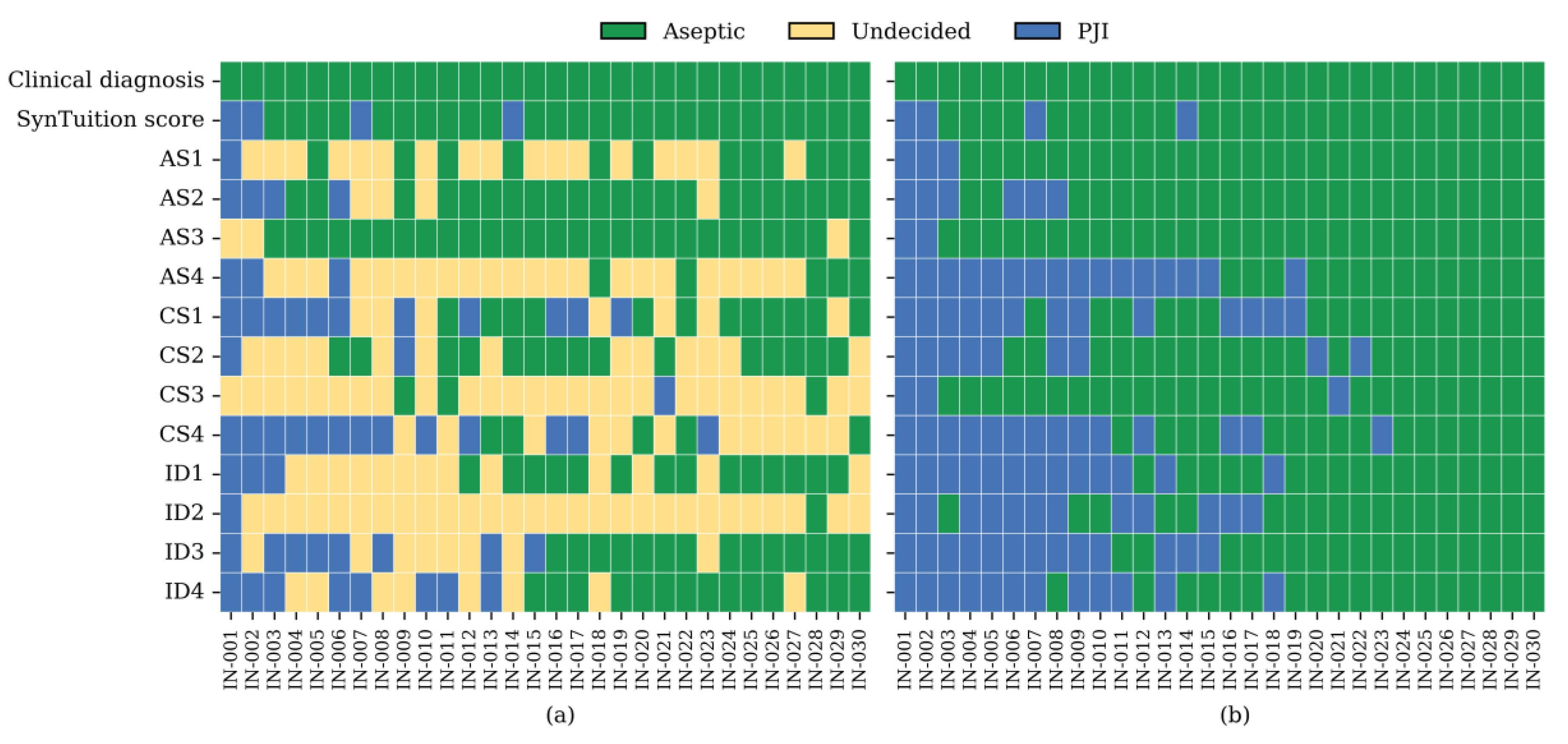

Figure 1 summarizes the diagnoses assigned by the SynTuition Score and each physician for the subset of cases classified as inconclusive by the 2018 ICM criteria. As shown in panel (a), a substantial proportion of physician responses were undecided during Stage I, with undecided rates of 38.3% among academic surgeons, 48.3% among community surgeons, 47.5% among ID physicians, representing an overall SOC rate of 44.7% across all physicians. When restricted to responses requiring a definitive diagnosis, as shown in panel (b), the overall percent agreement (OPA) for SynTuition was 86.7%, compared with 77.5% for academic surgeons, 67.5% for community surgeons, 58.3% for ID physicians, and 67.8% for combined SOC. The high level of diagnostic uncertainty and lower OPA values observed across physician groups highlight the risk of both underdiagnosis and overdiagnosis within this challenging cohort.

3.4. Decision Curve Analysis

Decision curve analysis is presented for each physician group and SynTuition (

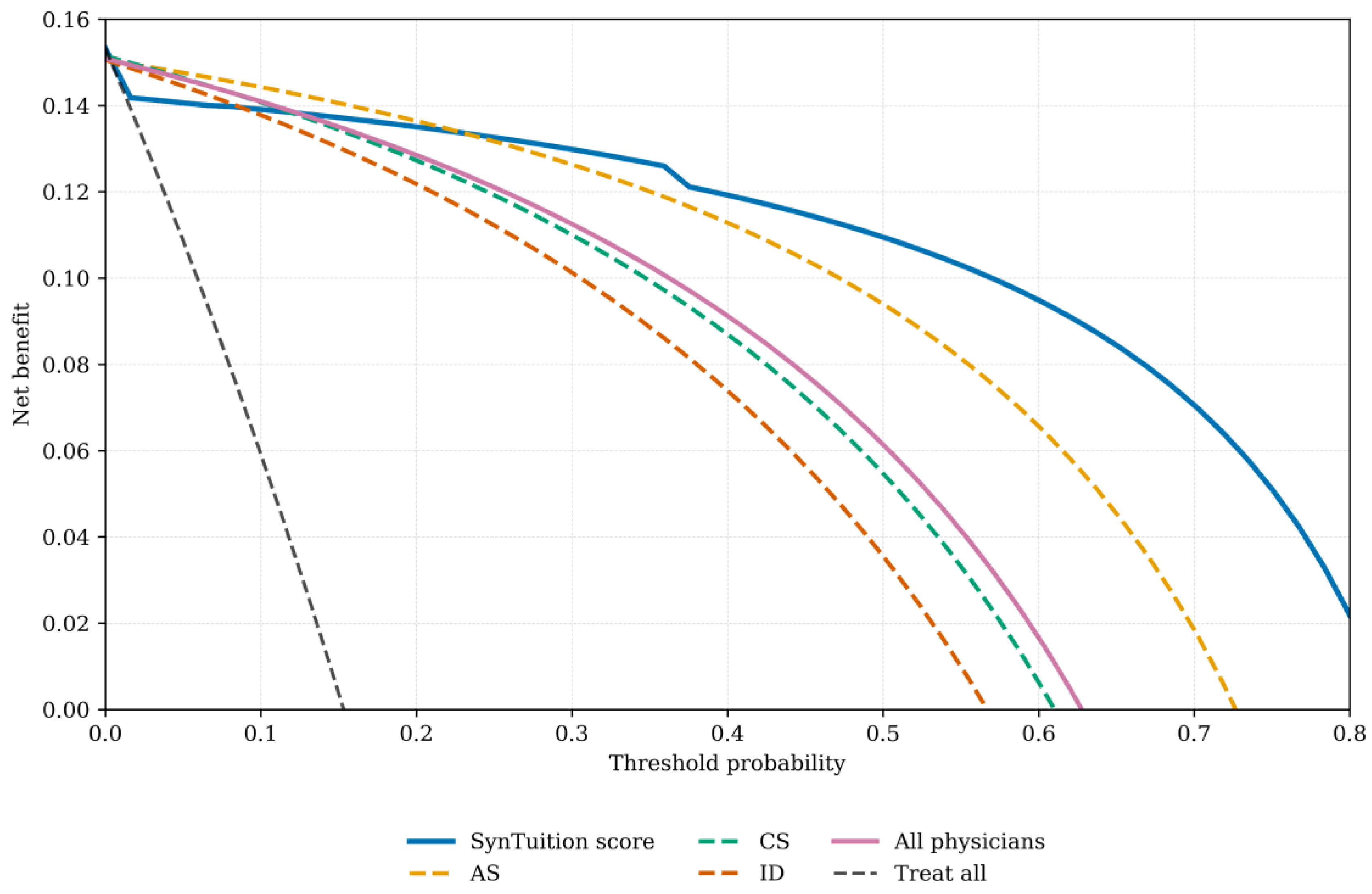

Figure 2). For each physician group, the mean net benefit across all threshold probabilities was calculated; for the all-physician group, the average net benefit across all 12 physicians was used. Interpretation of these curves requires selecting a threshold probability, with the diagnostic method showing the highest net benefit at that threshold, offering the greatest clinical value.

SynTuition demonstrated higher clinical value across a broad range of thresholds compared with the physician groups. For surgeons who prioritize treating every potential infection, even at the expense of overtreating some non-infected patients (threshold probability below 10%), the incremental benefit of SynTuition over current practice may be limited. However, many surgeons view a false-positive result as harmful and seek to avoid unnecessary treatment associated with overdiagnosis. Based on the decision curve analysis, surgeons with a threshold probability greater than or equal to 20% would benefit from incorporating the SynTuition Score into clinical decision-making.

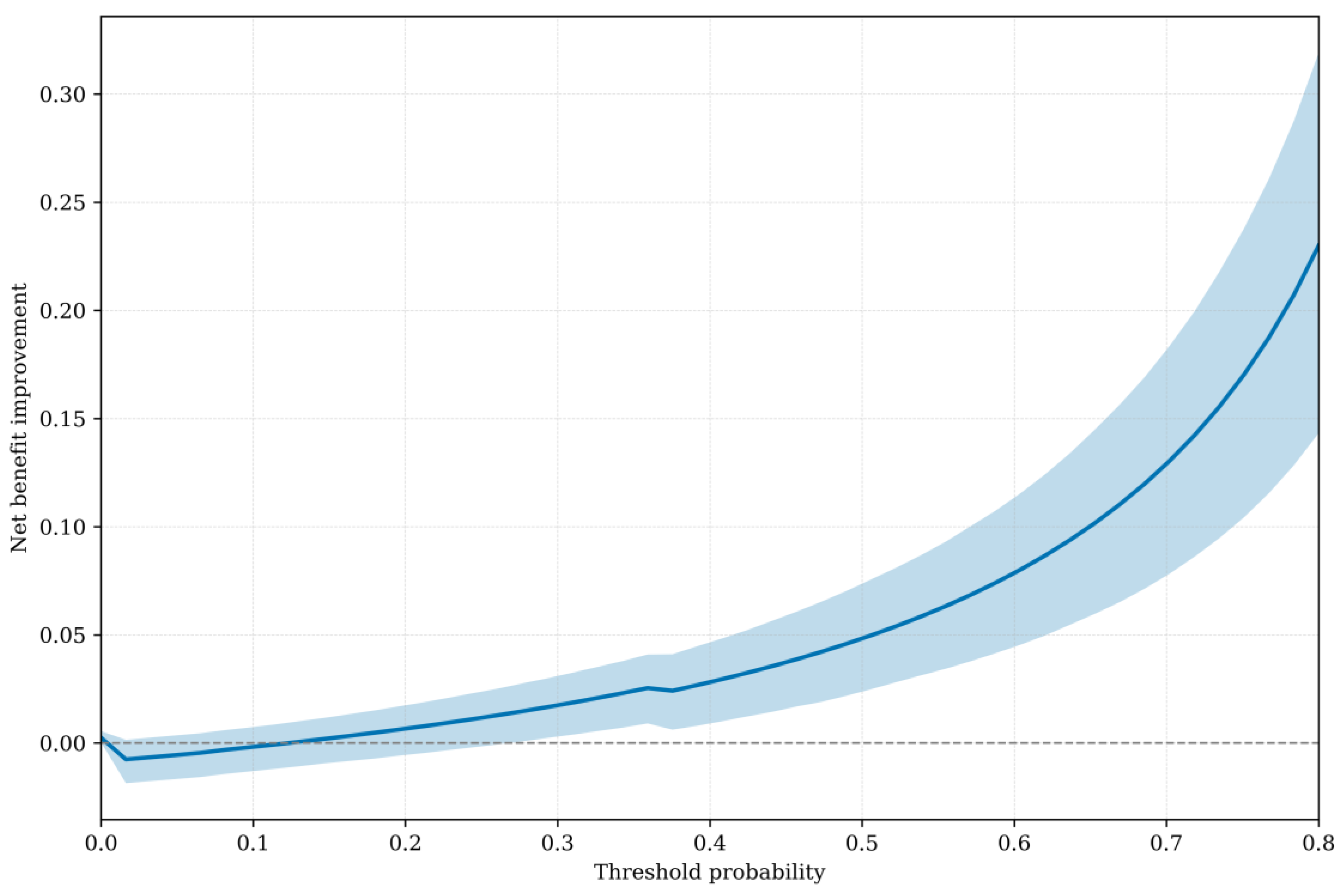

Figure 3 shows the net benefit SynTuition has over the SOC across a range of threshold probabilities. The solid line represents the mean net benefit improvement, while the shaded region denotes the 95% bootstrap confidence interval. The mean net benefit improvement increases with higher thresholds, and the 95% bootstrap confidence interval lies entirely above zero for threshold probabilities greater than approximately 30%.

To estimate a threshold probability reflecting economic value, we identified the point at which the expected cost of treatment equals the expected cost of no treatment, following the framework described by Vickers and Elkin [

21]. This threshold corresponds to the ratio of the cost of a false-positive decision to the combined costs of false-positive and false-negative decisions. Using an estimated cost of

$75,000 for a false positive and

$62,375 for a false negative, the resulting threshold probability was 0.55 (

$75,000 ÷

$137,375). At this threshold, SynTuition demonstrated a mean net benefit improvement of 0.06 (95% CI: 0.03 to 0.09) compared with current SOC. This improvement corresponds to approximately 4 to 11 fewer false positives per 100 patients, translating to a 4%–11% reduction in unnecessary two-stage septic revision surgeries when SynTuition is applied at the economically optimal threshold.

3.5. Economic Impact

The economic implications of SynTuition were evaluated using a decision-analytic model simulating 1,000 suspected PJI cases. Based on the SynTuition PPA and NPA (92.9% and 96.6%,

Table 5) and an assumed cohort of 153 PJI and 847 aseptic cases, the model yielded 11 false negatives and 29 false positives. Using estimated costs of

$62,375 per false-negative diagnosis and

$75,000 per false-positive diagnosis, the total projected cost attributable to misdiagnosis was approximately

$2.9 million.

In comparison, applying the PPA and NPA of the pooled physician group representing current SOC (98.4% and 89.4%,

Table 5) resulted in 2 false negatives and 90 false positives. The disproportionately high number of false positives reflects a tendency among physicians to favor overdiagnosis when diagnostic uncertainty is present. Under these assumptions, the total cost of misdiagnosis is roughly

$6.9 million. Comparing the two strategies, the reduction in misdiagnosis-related costs was

$4.0 million, corresponding to an estimated net savings of

$4,000 per suspected PJI case when SynTuition is used as an adjunct to current SOC.

4. Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the diagnostic consistency and economic implications of SynTuition when compared against routine physician practice, which represents the current SOC. The results demonstrate that SynTuition provides diagnostic performance comparable to, and in several respects exceeding, that of experienced physicians across orthopedic surgery and infectious disease specialties. Notably, the model substantially reduced diagnostic uncertainty and showed higher overall agreement with the clinical diagnosis than the pooled physician groups.

Across 274 clinical vignettes, SynTuition achieved an OPA of 96.0% and Gwet’s AC1 of 0.94, both of which were higher than those of the pooled all-physicians group (OPA: 90.8%, Gwet’s AC1: 0.87). Although the model’s PPA was lower than that of the pooled physicians, investigating discrepant cases identified that not all false-negative results represent clear misclassifications. Importantly, the SynTuition model does not incorporate culture results, and a score can be generated solely with synovial fluid biomarkers. This design does not preclude the use of culture data in clinical decision-making as and when it becomes available. While sequential decision-making was beyond the scope of this study, it is reasonable to suggest that a negative result by SynTuition could be reconsidered in the context of subsequent positive synovial fluid or tissue culture findings. Conversely, by operating independently of culture data and demonstrating a high NPA (96.6%), SynTuition supports early and reliable detection, with timely positive results facilitating optimal selection of patients for less invasive interventions such as DAIR or DECRA (Debridement, Modular Exchange, Component Retention, Antibiotics).

A central challenge in PJI diagnosis is the management of borderline or inconclusive cases, which frequently arise in the context of culture-negative results. These situations can amplify the limitations of criteria-based systems and highlight variability in clinical decision-making. In this study, 10.9% of cases were classified as inconclusive by the 2018 ICM definition, whichwere all adjudicated as aseptic by a panel of three experts. Within this challenging cohort, SynTuition demonstrated no equivocal results, producing a definitive diagnosis in all cases, whilst achieving an OPA of 86.7%. In contrast, physicians utilizing SOC displayed high indecision rates (38–48%) and considerably lower agreement with the clinical diagnosis, with an OPA of 67.8% across all physicians. These findings suggest that the SynTuition Score provides meaningful support where ambiguity is greatest, helping to mitigate both under- and overdiagnosis. It should also be noted that although all uncertain cases in this study were adjudicated as aseptic, other investigations report higher proportions of borderline cases being reclassified as PJI (between 41% and 53%) [

14,

26].

Decision curve analysis further illustrated the clinical utility of SynTuition across a wide range of threshold probabilities. For physicians who place a high value on avoiding unnecessary revision procedures, particularly those who consider false-positive diagnoses harmful, the model provided consistently greater net benefit than physician judgment alone. At an economically optimal threshold probability of 0.55, derived from current cost estimates for false-positive and false-negative diagnoses, SynTuition reduced unnecessary revision surgeries by an estimated 4–11 cases per 100 patients when compared with the pooled physician group. Although the decision curve analysis does not account for test-related harms, SynTuition carries no additional clinical risk beyond current standard of care. Some physicians may nonetheless argue that its net benefit should be weighed against considerations of test cost and availability.

The economic analysis aligned with these observations. When applied to a simulated cohort of 1,000 suspected PJI cases, SynTuition was projected to reduce misdiagnosis-related costs from roughly $6.9 million to $2.9 million, corresponding to an estimated per-patient savings of $4,000. Most of this reduction comes from the lower rate of false-positive diagnoses, reflecting a key advantage over physician tendencies toward overdiagnosis in ambiguous cases. These findings are based on a U.S. payer perspective, consistent with current SynTuition availability, and may not generalize to regions with differing healthcare cost structures or reimbursement models.

Despite the promising results, several limitations warrant consideration. First, although the vignettes were derived from real patient data and validated in prior work, they cannot fully replicate the richness of in-person clinical evaluation and nuanced contextual factors that influence diagnostic reasoning. However, the independent expert panel of adjudicators confirmed sufficient information was available to render a conclusive diagnosis for each vignette. Second, many biomarkers required by the SynTuition model were missing from the vignette dataset and were imputed using values from the model’s training cohort. It is reasonable to assume that performance would improve further if all 11 synovial fluid biomarkers were available for evaluation. Nevertheless, previous clinical validation studies demonstrated that the three most influential features for the model – AD, SF-WBC, and SF-PMN% – were present in over 96% of the dataset [

14]. Third, physicians had access to information such as synovial fluid culture results and clinical context not available to SynTuition, while the model used variables not reviewed by physicians, such as AD and SF-RBC, that are not widely available under current standard diagnostic protocols. Fourth, the adjudicated 2013 MSIS–based classification remains an imperfect ground truth, and borderline classifications remain debatable. Nonetheless, in the absence of a gold standard, this represents the best available clinical diagnosis. Finally, this analysis relied on pooled statistics with wide variance and economic estimates from published literature. Real-world costs will vary across institutions depending on clinical expertise, available resources, and established diagnostic pathways.

Future work may aim to evaluate SynTuition prospectively in clinical settings, incorporating sequential decision-making based on when biomarker results and other clinical information become available. The influence of SynTuition on downstream decision-making, including selection of DAIR/DECRA versus revision strategies, antibiotic stewardship, and outcomes, should also be examined.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that SynTuition reduces diagnostic uncertainty, improves agreement with the clinical diagnosis, and offers meaningful clinical and economic advantages over current standard of care diagnosis in suspected PJI. These findings support the role of machine learning-based diagnostic tools as valuable additions to clinical decision-making, particularly in cases where ambiguity poses substantial risk to patient outcomes.

6. Patents

This section is not mandatory but may be added if there are patents resulting from the work reported in this manuscript.

Supplementary Materials

None.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, JP, KOT, and VTP.; methodology, JP, VTP, AW, JB, PE, and KOT; software, JP; validation, AW, VTP and KOT.; formal analysis, JP; investigation, JP, AW; resources, KOT; data curation, JP and KOT; writing—original draft preparation, JP; writing—review and editing, All authors; visualization, VTP, KOT, JB, and PE; supervision, JB, PE, and KOT; project administration, KOT; funding acquisition, KOT. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study involved secondary analysis of data from a survey study that was conducted using previously de-identified data. The survey study was determined to be exempt from Institutional Review Board review in accordance with applicable regulations and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

The survey study and this secondary analysis utilized de-identified data and did not involve direct interaction with participants; therefore, no informed consent was required.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Because the dataset includes patient test data, public sharing could pose a risk of re-identification and violate HIPAA privacy regulations. Requests will be reviewed to ensure compliance with applicable privacy laws and institutional policies, and data will only be shared for legitimate research purposes.

Conflicts of Interest

Paul K Edwards - consulting payments and research support from Zimmer Biomet, unrelated to this study. James F Baker - consulting payments, speaker honoraria, and research support from Zimmer Biomet, unrelated to this study. Van Thai-Paquette - paid employee of Zimmer Biomet; holds Zimmer Biomet stock/options. Jim Parr - paid employee of Zimmer Biomet; holds Zimmer Biomet stock/options. Krista Toler – paid employee of Zimmer Biomet; holds Zimmer Biomet stock/options. Amy Worden – paid employee of Zimmer Biomet, holds Zimmer Biomet stock/options

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MDPI |

Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ |

Directory of open access journals |

| PJI |

Periprosthetic joint infection |

| DAIR |

Debridement, antimicrobial therapy, and implant retention |

| DECRA |

Debridement, Modular Exchange, Component Retention, Antibiotics |

| SOC |

Standard of care |

| PPA |

Positive percent agreement |

| NPA |

Negative percent agreement |

| OPA |

Overall percent agreement |

| AD |

Alpha defensin |

| SF-WBC |

Synovial fluid white blood cell |

| SF-PMN% |

Synovial fluid polymorphonuclear percentage |

| SF-RBC |

Synovial fluid red blood cell |

| SF-CRP |

Synovial fluid C-reactive protein |

| A280 |

Spectrophotometric absorbance at 280 nm wavelength |

| CP |

Candida microbial antigen |

| EF |

Enterococcus microbial antigen |

| SPA |

Staphylococcus microbial antigen A |

| SPB |

Staphylococcus microbial antigen B |

| PAC |

Cutibacterium acnes microbial antigen |

References

- Fröschen, F.S.; Randau, T.M.; Franz, A.; Molitor, E.; Hischebeth, G.T.R. Microbiological Profiles of Patients with Periprosthetic Joint Infection of the Hip or Knee. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1654. [CrossRef]

- Koh, C.K., Zeng, I., Ravi, S. et al. Periprosthetic Joint Infection Is the Main Cause of Failure for Modern Knee Arthroplasty: An Analysis of 11,134 Knees. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2017, 475, 2194–2201. [CrossRef]

- Aftab MHS, Joseph T, Almeida R, Sikhauli N, Pietrzak JRT. Periprosthetic Joint Infection: A Multifaceted Burden Undermining Arthroplasty Success. Orthopedic Reviews. 2025, 17. [CrossRef]

- Klug, A., Gramlich, Y., Rudert, M. et al. The projected volume of primary and revision total knee arthroplasty will place an immense burden on future health care systems over the next 30 years. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2021, 29, 3287–3298. [CrossRef]

- Sigmund, I. K., Ferry, T., Sousa, R., Soriano, A., Metsemakers, W. J., Clauss, M., Trebse, R., and Wouthuyzen-Bakker, M.: Debridement, antimicrobial therapy, and implant retention (DAIR) as curative strategy for acute periprosthetic hip and knee infections: a position paper of the European Bone & Joint Infection Society (EBJIS), J. Bone Joint Infect. 2025, 10, 101–138. [CrossRef]

- Parvizi J, Gehrke T: Definition of periprosthetic joint infection. J Arthroplasty. 2014, 29, 1331. [CrossRef]

- Shohat N, Bauer T, Buttaro M, et al.: Hip and knee section, what is the definition of a periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) of the knee and the hip? Can the same criteria be used for both joints?: Proceedings of International Consensus on Orthopedic Infections. J Arthroplasty 2019, 34, 325-7. [CrossRef]

- McNally M, Sousa R, Wouthuyzen-Bakker M, et al.: The EBJIS definition of periprosthetic joint infection. Bone Joint J. 2021, 103-B, 18-25. [CrossRef]

- Osmon DR, Berbari EF, Berendt AR, et al.: Executive summary: diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infection: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2013, 56, 1-10. [CrossRef]

- Deirmengian C, McLaren A, Higuera C, Levine BR: Physician use of multiple criteria to diagnose periprosthetic joint infection may be less accurate than the use of an individual test. Cureus. 2022, 14, 31418. [CrossRef]

- Nelson SB, Pinkney JA, Chen AF, Tande AJ: Periprosthetic joint infection: current clinical challenges. Clin Infect Dis. 2023, 77, 34-45. [CrossRef]

- Rocchi, C.; Di Maio, M.; Bulgarelli, A.; Chiappetta, K.; La Camera, F.; Grappiolo, G.; Loppini, M. Agreement Analysis Among Hip and Knee Periprosthetic Joint Infections Classifications. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 1172. [CrossRef]

- Di Matteo, V.; Morandini, P.; Savevski, V.; Grappiolo, G.; Loppini, M. Preoperative Diagnosis of Periprosthetic Infection in Patients Undergoing Hip or Knee Revision Arthroplasties: Development and Validation of Machine Learning Algorithm. Diagnostics 2025, 15, 539. [CrossRef]

- Parr J, Thai-Paquette V, Paranjape P, McLaren A, Deirmengian C, Toler K. Probability Score for the Diagnosis of Periprosthetic Joint Infection: Development and Validation of a Practical Multi-analyte Machine Learning Model. Cureus 2025, 13, 17(5). [CrossRef]

- Deirmengian C, Madigan J, Kallur Mallikarjuna S, Conway J, Higuera C, Patel R: Validation of the alpha defensin lateral flow test for periprosthetic joint infection. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2021, 103, 115-22. [CrossRef]

- Baker CM, Goh GS, Tarabichi S, Shohat N, Parvizi J. Synovial C-Reactive Protein is a Useful Adjunct for Diagnosis of Periprosthetic Joint Infection. J Arthroplasty. 2022, 37(12), 2437-2443. [CrossRef]

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Statistical Guidance on Reporting Results from Studies Evaluating Diagnostic Tests. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2007. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/71147/download (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Gwet, K.L. Handbook of Inter-Rater Reliability: The Definitive Guide to Measuring the Extent of Agreement Among Raters, 4th ed.; Advanced Analytics, LLC.: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2014.

- Wilson, Edwin B. Probable Inference, the Law of Succession, and Statistical Inference. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 1927, 22, 158, 209–12. [CrossRef]

- Efron, B.; Tibshirani, R.J. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Chapman & Hall/CRC: New York, NY, USA, 1993.

- Vickers AJ, Elkin EB. Decision curve analysis: a novel method for evaluating prediction models. Med Decis Making. 2006, 26(6), 565-74. [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://cost.sidecarhealth.com/n/joint-aspiration-cost (accessed on 9 December 2025).

- Okafor C, Hodgkinson B, Nghiem S, Vertullo C, Byrnes J. Cost of septic and aseptic revision total knee arthroplasty: A systematic review. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2021, 22, 706. [CrossRef]

- Kurtz SM, Lau E, Watson H, Schmier JK, Parvizi J. Economic burden of periprosthetic joint infection in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2012, 27, 8 Suppl. [CrossRef]

- McNally M, Sigmund I, Hotchen A, Sousa R. Making the diagnosis in prosthetic joint infection: a European view. EFORT Open Rev. 2023, 9;8(5), 253-263. [CrossRef]

- Hersh BL, Shah NB, Rothenberger SD, Zlotnicki JP, Klatt BA, Urish KL. Do Culture Negative Periprosthetic Joint Infections Remain Culture Negative? J Arthroplasty. 2019, 34(11), 2757-2762. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).