Submitted:

19 January 2026

Posted:

19 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

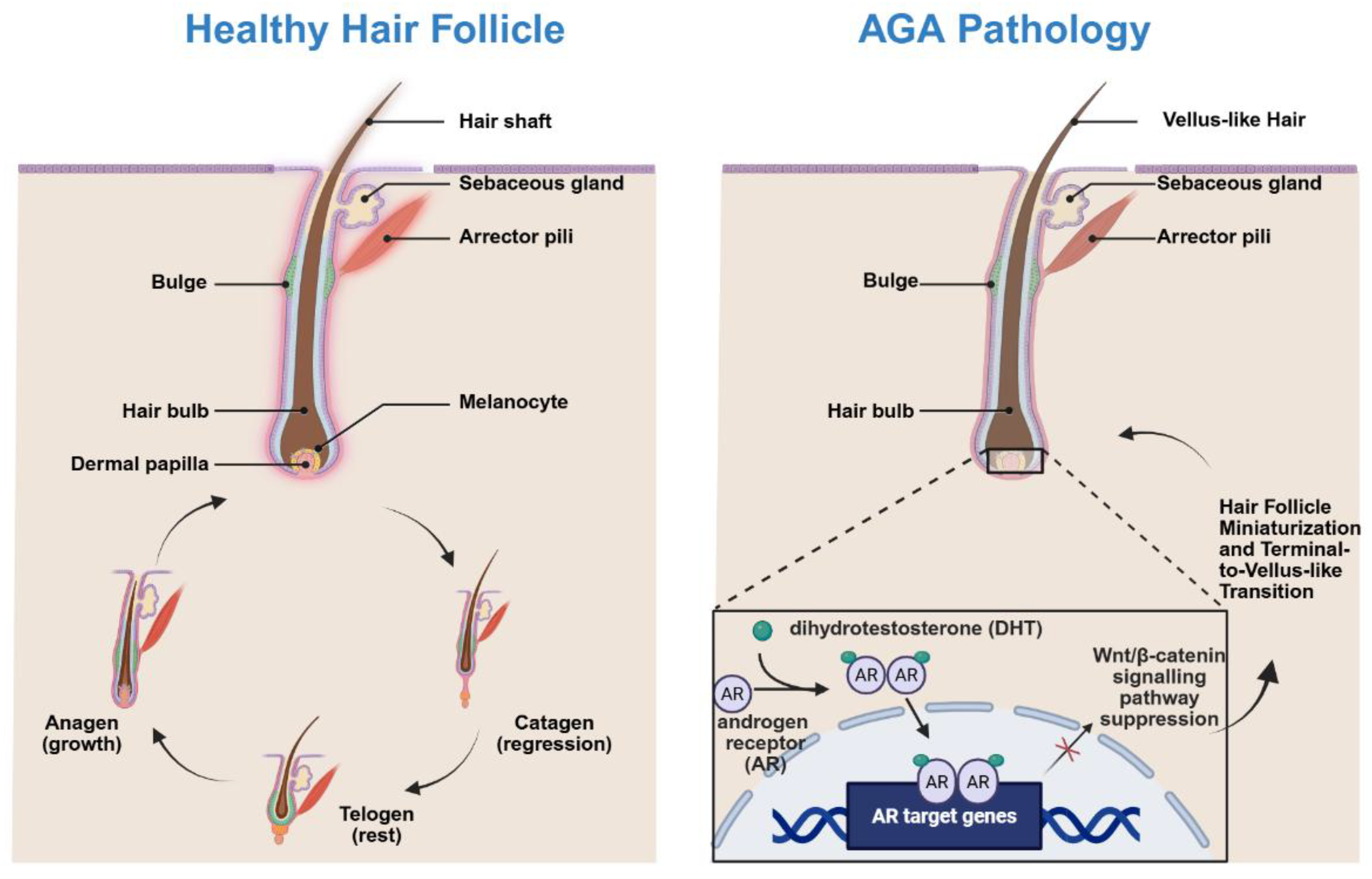

2. Pathophysiology of AGA

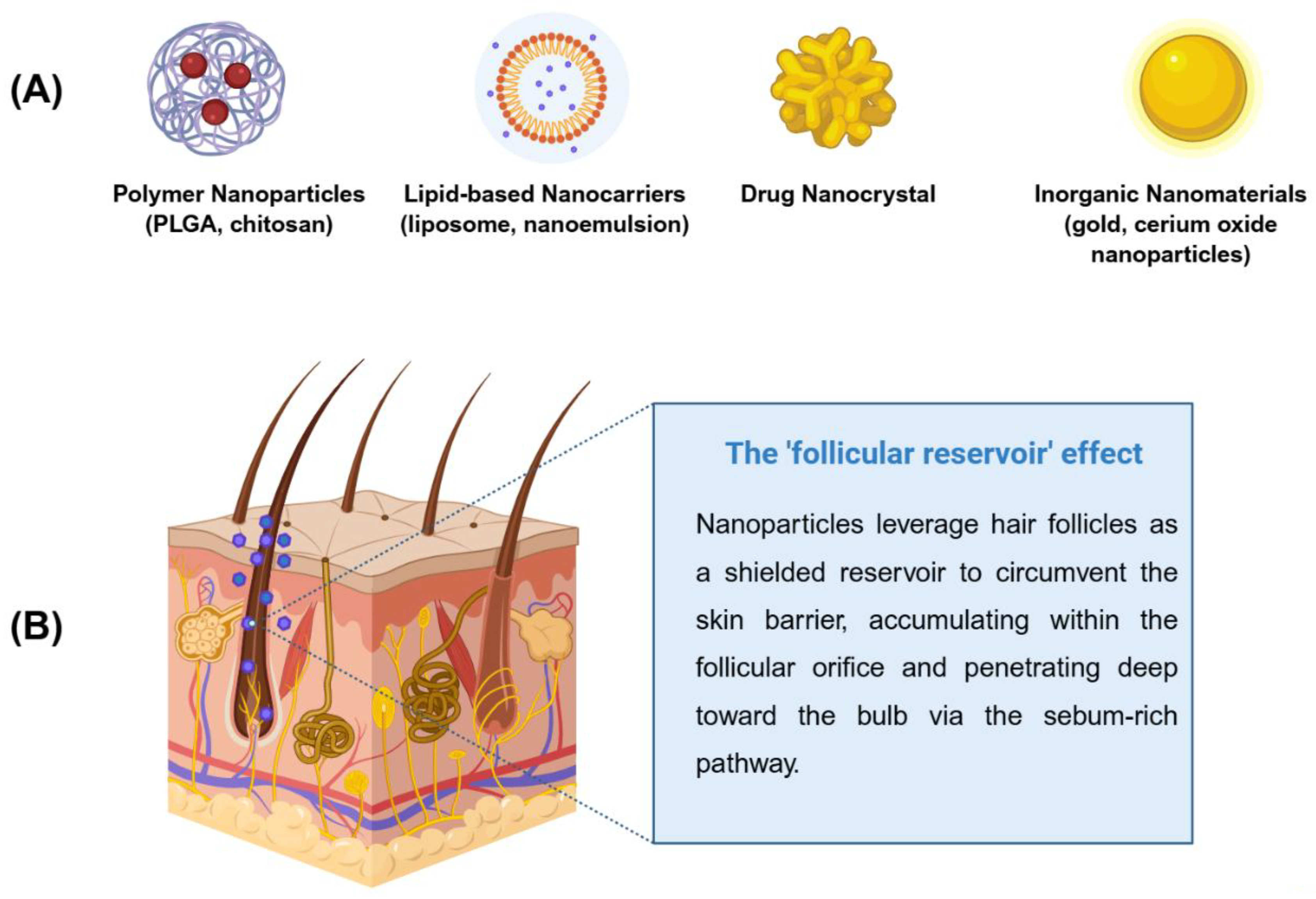

3. Nanocarrier-Based Drug Delivery Systems for AGA

| Nanocarrier Class | Example Materials | Therapeutic Mechanism / Drug Delivered | Key Advantages for AGA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymeric Nanoparticles | PLGA, Chitosan, PCL | Encapsulation of Finasteride, Minoxidil, or growth factors. | Provides sustained drug release; protects unstable biomolecules; reduces dosing frequency. |

| Lipid-based Carriers | Liposomes, Ethosomes, Nanoemulsions | Delivery of hydrophobic drugs; targeted to the sebaceous gland. | High affinity for follicular sebum; enhances skin penetration; biocompatible and low toxicity. |

| Drug Nanocrystals | Pure drug crystals with stabilizers (PVP, SDS) | High-dose delivery of poorly soluble compounds. | Maximizes drug loading capacity; improves dissolution rates; allows for dose reduction. |

| Inorganic Nanomaterials | Gold (Au) NPs, Ceria (CeO2) NPs, Mesoporous Silica | Ceria nanozymes for ROS scavenging; Gold NPs for photothermal or delivery. | Intrinsic antioxidant and pro-angiogenic activities; high surface-to-volume ratio for functionalization. |

| Exosomes / EVs | Mesenchymal stem cell-derived exosomes | Delivery of regenerative mi-RNAs and proteins to Dermal Papilla cells. | Highly biomimetic; low immunogenicity; promotes Wnt/β-catenin signaling directly. |

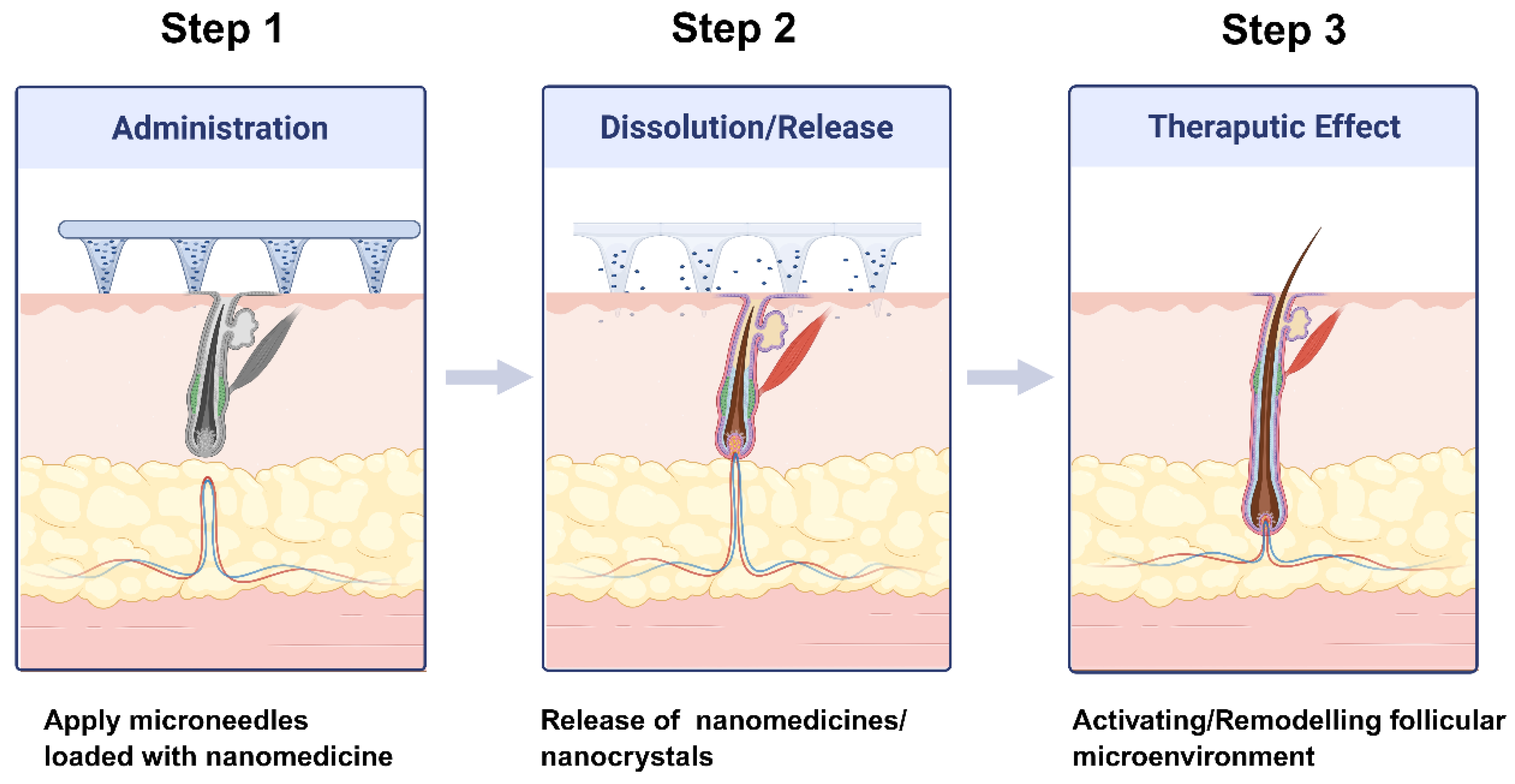

4. Nano-Enabled Microneedle Systems for Transdermal Follicular Delivery

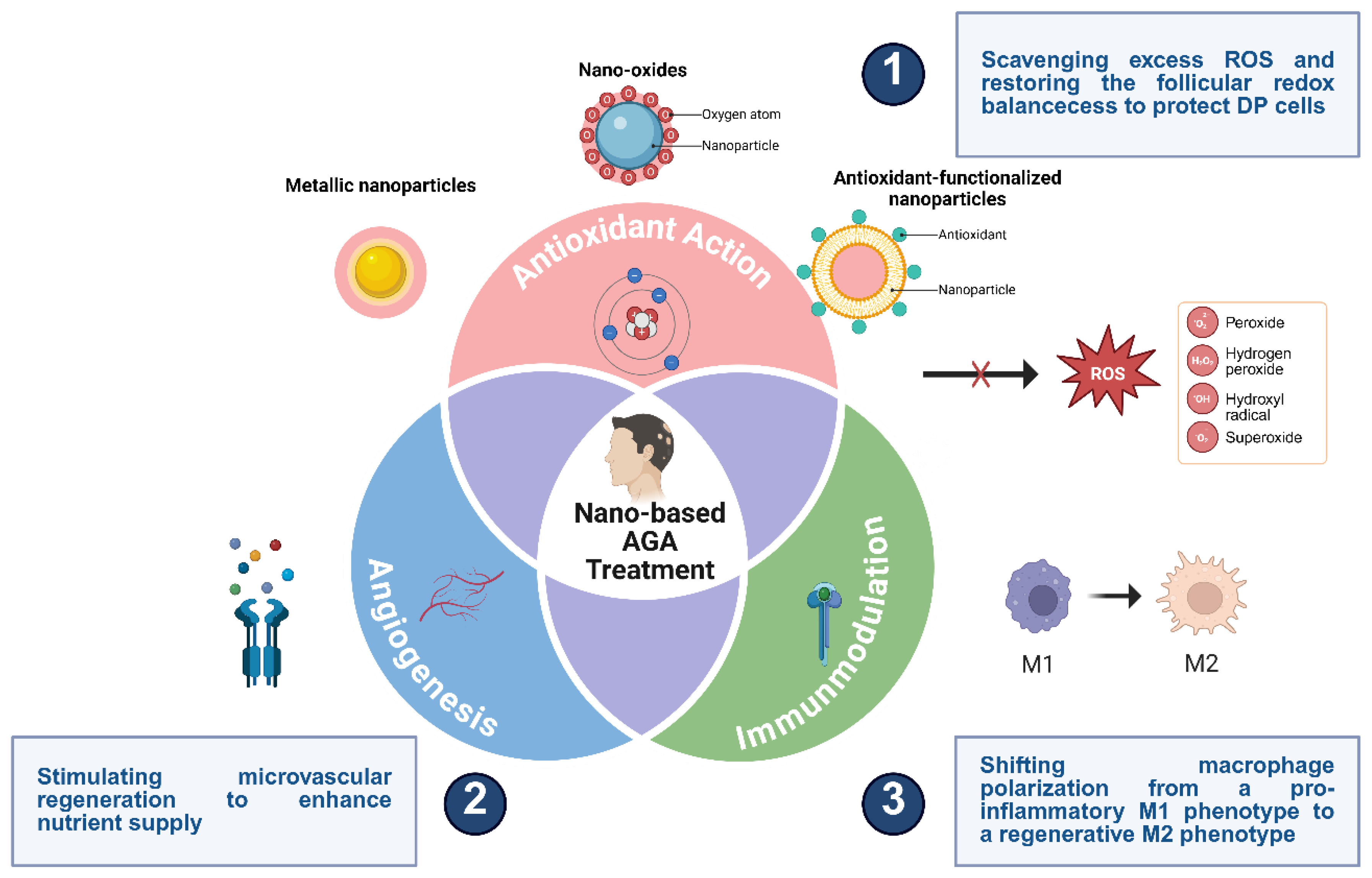

5. Nano-Enabled Remodeling of the Hair Follicle Microenvironment

6. Safety, Toxicity, and Regulatory Considerations

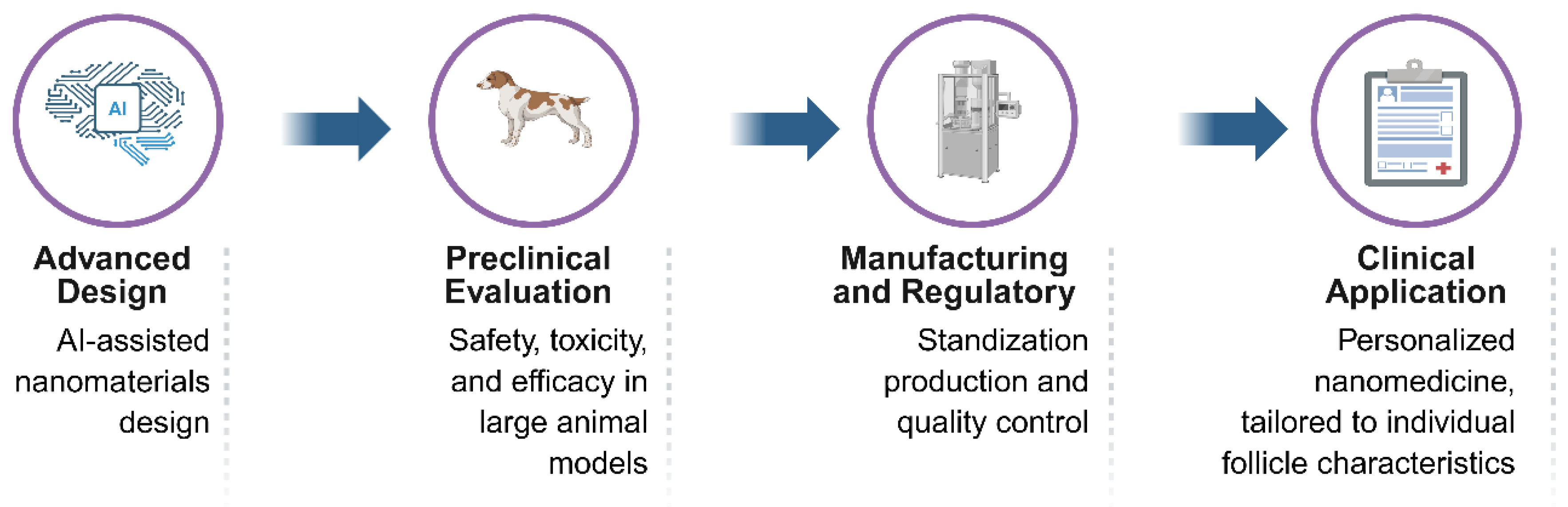

7. Clinical Translation and Future Perspectives

| Translational Aspect | Current Status & Challenges | Proposed Future Directions |

|---|---|---|

| Safety & Toxicology | Potential for long-term accumulation of non-biodegradable NPs in the skin; limited systemic toxicity data. | Extensive chronic toxicity studies and use of biodegradable, “green” nanomaterials. |

| Manufacturing Scale-up | Batch-to-batch variability; high cost of specialized equipment for complex nanostructures. | Development of microfluidic-based synthesis and standardized manufacturing protocols (GMP). |

| Regulatory Hurdles | Lack of specific FDA/EMA guidelines for “nano-cosmeceuticals” and complex delivery systems. | Harmonization of international testing standards; close collaboration with regulatory agencies. |

| Clinical Validation | Most data derived from rodent models; human scalp skin thickness and follicle density differ. | Use of 3D-printed human skin models and humanized mice for more accurate preclinical screening. |

| Patient Compliance | High frequency of application for topical nanosystems; cost of microneedle-based therapies. | Designing long-acting (e.g., monthly) delivery platforms and low-cost MN manufacturing techniques. |

8. Conclusions

References

- Geyfman, M.; et al. Resting no more: re-defining telogen, the maintenance stage of the hair growth cycle. 2015, 90(4), 1179–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nuaimi, Y.; et al. The cycling hair follicle as an ideal systems biology research model. 2010, 19(8), 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.W.; et al. A guide to studying human hair follicle cycling in vivo. 2016, 136(1), 34–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houschyar, K.S.; et al. Molecular mechanisms of hair growth and regeneration: current understanding and novel paradigms. 2020, 236(4), 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, J.D.; et al. The biology of human hair greying. 2021, 96(1), 107–128.

- Xue, C.; et al. Wnt signaling pathways in biology and disease: mechanisms and therapeutic advances. 2025, 10(1), 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; et al. Cell signaling and transcriptional regulation of osteoblast lineage commitment, differentiation, bone formation, and homeostasis. 2024, 10(1), 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Chen, G.; Li, Y.-P.J.B.r. TGF-β and BMP signaling in osteoblast, skeletal development, and bone formation, homeostasis and disease. 2016, 4(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abe, Y.; Tanaka, N.J.J.o.d.b. Roles of the hedgehog signaling pathway in epidermal and hair follicle development, homeostasis, and cancer. 2017, 5(4), 12. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; et al. Regulation of signaling pathways in hair follicle stem cells. 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, S.B.; Park, H.J.; Lee, B.-H.J.I.j.o.m.s. Hair-growth-promoting effects of the fish collagen peptide in human dermal papilla cells and C57BL/6 mice modulating Wnt/β-catenin and BMP signaling pathways. 2022, 23(19), 11904. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Lee, J.J.P. Modulation of hair growth promoting effect by natural products. 2021, 13(12), 2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; et al. Androgenetic alopecia. 2025, 11(1), 73.

- Oiwoh, S.O.; et al. Androgenetic alopecia: A review. 2024, 31(2), 85–92.

- Ntshingila, S.; et al. Androgenetic alopecia: An update. 2023, 13, 150–158.

- Altendorf, S.; et al. Frontiers in the physiology of male pattern androgenetic alopecia: Beyond the androgen horizon. 2026, 106(1), 121–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo-Pérez, L.; et al. Clinical and preclinical approach in AGA treatment: a review of current and new therapies in the regenerative field. 2024, 15(1), 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelkader, A.; et al. Androgenetic alopecia: an overview. 2024, 9(2), 37–50.

- Katzer, T.; et al. Physiopathology and current treatments of androgenetic alopecia: going beyond androgens and anti-androgens. 2019, 32(5), e13059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidangazhiathmana, A.; Santhosh, P.J.C.D.R. Pathogenesis of androgenetic alopecia. 2022, 6(2), 69–74.

- Ovcharenko, Y.; Khobzei, K.; Lortkipanidze, N. Androgenetic alopecia, in Psychotrichology: Psychiatric and Psychosocial Aspects of Hair Diseases; Springer, 2025; pp. 137–170. [Google Scholar]

- McElwee, K.J.; Sundberg, J.P.J.E.O.o.D.D. Innovative strategies for the discovery of new drugs against androgenetic alopecia. 2025, 20(4), 517–536. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Goyal, I.; Mahendra, A.J.I.j.o.t. Quality of life assessment in patients with androgenetic alopecia. 2019, 11(4), 147–152. [Google Scholar]

- Han, S.-H.; et al. Quality of life assessment in male patients with androgenetic alopecia: result of a prospective, multicenter study. 2012, 24(3), 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-H.; Fu, Y.; Chi, C.-C.J.J.d. Health-related quality of life, depression, and self-esteem in patients with androgenetic alopecia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. 2021, 157(8), 963–970. [Google Scholar]

- Tampucci, S.; et al. Nanostructured drug delivery systems for targeting 5-α-reductase inhibitors to the hair follicle. 2022, 14(2), 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobari, N.N.; et al. A systematic review of clinical trials using single or combination therapy of oral or topical finasteride for women in reproductive age and postmenopausal women with hormonal and nonhormonal androgenetic alopecia. 2023, 32(7), 813–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, P.; Garcovich, S.J.I.j.o.m.s. Systematic review of platelet-rich plasma use in androgenetic alopecia compared with Minoxidil®, Finasteride®, and adult stem cell-based therapy. 2020, 21(8), 2702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestor, M.S.; et al. Treatment options for androgenetic alopecia: Efficacy, side effects, compliance, financial considerations, and ethics. 2021, 20(12), 3759–3781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messenger, A.; Rundegren, J.J.B.j.o.d. Minoxidil: mechanisms of action on hair growth. 2004, 150(2), 186–194. [Google Scholar]

- York, K.; et al. A review of the treatment of male pattern hair loss. 2020, 21(5), 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Talukder, M.; Williams, G.J.J.o.D.T. Comparison of oral minoxidil, finasteride, and dutasteride for treating androgenetic alopecia. 2022, 33(7), 2946–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuca, M.; et al. Risk associated with the use of 5-alpha reductase inhibitors with minoxidil in treatment of male androgenetic alopecia-literature review. 2025, 19(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; et al. Androgenetic Alopecia: An Update on Pathogenesis and Pharmacological Treatment 2025, 7349–7363.

- Lee, S.W.; et al. A systematic review of topical finasteride in the treatment of androgenetic alopecia in men and women. 2018, 17(4), 457. [Google Scholar]

- Rane, B.R.; et al. Follicular Delivery of Nanocarriers to Improve Skin Disease Treatment, in Novel Nanocarriers for Skin Diseases; Apple Academic Press, 2025; pp. 209–237. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, C.-L.; et al. Delivery and targeting of nanoparticles into hair follicles. 2014, 5(9), 991–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cevc, G.; Vierl, U.J.J.o.c.r. Nanotechnology and the transdermal route: A state of the art review and critical appraisal. 2010, 141(3), 277–299. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rancan, F.; et al. Hair follicle targeting with nanoparticles, in Nanotechnology in dermatology; Springer, 2012; pp. 95–107. [Google Scholar]

- Hamblin, M.R.; Avci, P.; Prow, T. Nanoscience in dermatology; Academic Press, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira-Silva, M.; et al. Nanomaterials in Hair Care and Treatment: Current Advances and Future Perspectives.

- Brito, S.; Baek, M.; Bin, B.-H.J.P. Skin structure, physiology, and pathology in topical and transdermal drug delivery. 2024, 16(11), 1403. [Google Scholar]

- Giradkar, V.; et al. Nanocrystals: a multifaceted regimen for dermatological ailments. 2024, 41(6), 2300147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; et al. Functional nano-systems for transdermal drug delivery and skin therapy. 2023, 5(6), 1527–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkar, S.; et al. Nano-lipidic carriers as a tool for drug targeting to the pilosebaceous units. 2020, 26(27), 3251–3268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parga, A.; Ray, B.J.I.J.N.N. Advances in Nanocarrier Systems for Dermatologic Transdermal Drug Delivery: A Chemical and Molecular Review. 2025, 10(1), 01–12. [Google Scholar]

- Mathes, C. Drug delivery to the hair follicle: role of follicular tight junctions as a biological barrier and the potential for targeting clobetasol nanocarriers. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh, Z.S.A.; et al. Nanotechnology-based strategies for hair follicle regeneration in androgenetic alopecia. 2023, 14(1), 57. [Google Scholar]

- KAYAL, P.; et al. NANOCARRIER-BASED APPROACHES FOR ENHANCED MANAGEMENT OF ANDROGENETIC ALOPECIA: ADVANCEMENTS AND FUTURE PROSPECTS. 2025, 17(3), 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Du, Y.-z.J.M.P. Nanodrug delivery strategies to signaling pathways in alopecia. 2023, 20(11), 5396–5415. [Google Scholar]

- Bambale, P.G.; Lewade, V.; Daundkar, S. Exploring Novel Treatments for Alopecia: Nanoparticles, Iontophoresis, and Cell Therapy. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, M.D. Nanotechnology-Based Therapeutics Strategies Towards the Topical Treatment of Hair Loss; Universidade de Coimbra (Portugal), 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Diao, R.; et al. Novel Strategies for Androgenetic Alopecia Therapy: Integrating Multifunctional Plant Extracts with Nanotechnology for Advanced Cutaneous Drug Delivery. 2025, 17(9), 1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; et al. Advances in Transdermal Delivery Systems for Treating Androgenetic Alopecia. 2025, 17(8), 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, J.F.; et al. An update on nanocarriers for follicular-targeted drug delivery for androgenetic alopecia topical treatment. 2025, 22(3), 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; et al. Polydopamine synergizes with quercetin nanosystem to reshape the perifollicular microenvironment for accelerating hair regrowth in androgenetic alopecia. 2024, 24(20), 6174–6182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalilzad, M.A.; et al. Elevating Dermatology Beyond Aesthetics: Perinatal-Derived Advancements for Rejuvenation, Alopecia Strategies, Scar Therapies, and Progressive Wound Healing. 2025, 21(3), 709–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik, H.; Bal-Öztürk, A.J.B. Tissue Engineering and Nanoparticle-Based Approaches for Hair Follicle Regeneration. 2025, 15(2), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, T.-r.; et al. Progress on mitochondria and hair follicle development in androgenetic alopecia: relationships and therapeutic perspectives. 2025, 16(1), 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; et al. Ni–Cu Bimetallic Nanozyme and Minoxidil Co-Loaded Dissolving Microneedles Reshape Hair Follicle Microenvironment for Androgenic Alopecia Treatment. 2025, 8(18), 9502–9514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stough, D.; et al. Psychological effect, pathophysiology, and management of androgenetic alopecia in men. in Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Elsevier, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lolli, F.; et al. Androgenetic alopecia: a review. 2017, 57(1), 9–17.

- Kaliyadan, F.; et al. Androgenetic alopecia: an update. 2013, 79, 613.

- Kabir, Y.; Goh, C.J.J.o.t.E.W.s.D.S. Androgenetic alopecia: update on epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment. 2013, 10(3), 107–116. [Google Scholar]

- Trüeb, R.M.J.E.g. Molecular mechanisms of androgenetic alopecia. 2002, 37(8-9), 981–990. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Y.; et al. Immune and Non-immune Interactions in the Pathogenesis of Androgenetic Alopecia. 2025, 68(1), 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eunmiri, R.J.C. Advancements in Bioactive Compounds and Therapeutic Agents for Alopecia: Trends and Future Perspectives. 2025, 12(6), 287. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, H.; et al. Pathogenic Mechanisms and Mechanism-Directed Therapies for Androgenetic Alopecia: Current Understanding and Future Directions. 2025, 2025(1), 9950475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, D.; et al. The regulatory mechanisms of mitophagy and oxidative stress in androgenetic alopecia; 2025; p. 111862. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, D.; et al. Advances in research on concentrated growth factor applications for androgenetic alopecia treatment: A review. 2025, 31, e948054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairnar, T.D.; et al. Recent trends in nanocarrier formulations of actives beyond minoxidil and 5-α reductase inhibitors in androgenetic alopecia management: A systematic review. 2024, 98, 105890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patzelt, A.; Lademann, J.J.E.o.o.d.d. Recent advances in follicular drug delivery of nanoparticles . 2020, 17(1), 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Raut, S.Y.; et al. Engineered Nano-carrier systems for the oral targeted delivery of follicle stimulating Hormone: Development, characterization, and, assessment of in vitro and in vivo performance and targetability. 2023; 637, p. 122868.

- Qi, F.; et al. Plant Nanovesicles Integrate Bioactivity and Transdermal Finasteride Delivery for Androgenetic Alopecia. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, A.C.; et al. Topical minoxidil-loaded nanotechnology strategies for alopecia. 2020, 7(2), 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, F.; et al. Advanced nanocarrier-and microneedle-based transdermal drug delivery strategies for skin diseases treatment. 2022, 12(7), 3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, K.; et al. Minoxidil Nano-hydrogel Based on Chitosan and Hyaluronic Acid for Potential Treatment of Androgenic Alopecia. 2025, 15(2), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd, E.; et al. Follicular penetration of caffeine from topically applied nanoemulsion formulations containing penetration enhancers: in vitro human skin studies. 2018, 31(5), 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madawi, E.A.; et al. Polymeric nanoparticles as tunable nanocarriers for targeted delivery of drugs to skin tissues for treatment of topical skin diseases. 2023, 15(2), 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, W.Y.; et al. Transdermal delivery of Minoxidil using HA-PLGA nanoparticles for the treatment in alopecia. 2019, 23(1), 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; et al. Polymeric nanoparticles-based topical delivery systems for the treatment of dermatological diseases. 2013, 5(3), 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, B.N.; et al. Chitosan nanoparticles for targeting and sustaining minoxidil sulphate delivery to hair follicles. 2015, 75, 225–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; et al. Poly (γ-glutamic acid)/chitosan hydrogel nanoparticles for effective preservation and delivery of fermented herbal extract for enlarging hair bulb and enhancing hair growth 2019, 8409–8419.

- Lok, K.-H.; et al. Topical and transdermal lipid-polymer hybrid nanoparticles (LPN): an integration in advancing dermatological treatments. 2025, 15(11), 4277–4313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, F.; et al. Advanced nanocarrier-and microneedle-based transdermal drug delivery strategies for skin diseases treatment. 2022, 12(7), 3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulkarni, D.; et al. Recent advancements in microneedle technology for multifaceted biomedical applications. 2022, 14(5), 1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillot, A.J.; et al. Microneedle-assisted transdermal delivery of nanoparticles: Recent insights and prospects. 2023, 15(4), e1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrudden, M.T.; et al. Microneedle applications in improving skin appearance. 2015, 24(8), 561–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitzanti, G. Lipid nanocarriers and 3D printed hollow microneedles as strategies to promote drug delivery via the skin. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; et al. Machine learning guided discovery of superoxide dismutase nanozymes for androgenetic alopecia. 2022, 22(21), 8592–8600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokale, R.; et al. Focused Review on Metal Nanoparticles in Hair Regeneration and Alopecia: Insights into Mechanisms, Assessment Techniques, Toxicity, Regulatory and Intellectual Property Perspectives: R. Pokale et al. 2025, 36(4), 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, H.; et al. Near-infrared light-triggered nitric oxide-releasing hyaluronic acid hydrogel for precision transdermal therapy of androgenic alopecia. 2025, 304, 140751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.-L.; et al. Functional complexity of hair follicle stem cell niche and therapeutic targeting of niche dysfunction for hair regeneration. 2020, 27(1), 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, W.; et al. Environmental regulation of skin pigmentation and hair regeneration; Mary Ann Liebert, Inc.: publishers 140 Huguenot Street, 3rd Floor New …, 2022; pp. 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, S.; et al. Functional hair follicle regeneration: an updated review. 2021, 6(1), 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chueh, S.-C.; et al. Therapeutic strategy for hair regeneration: hair cycle activation, niche environment modulation, wound-induced follicle neogenesis, and stem cell engineering. 2013, 13(3), 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, A.J.C.i.D. Nanotechnology and dermatology: Part II—risks of nanotechnology. 2010, 28(5), 581–588. [Google Scholar]

- Andrade, S.S.; et al. Hurdles in translating science from lab to market in delivery systems for Cosmetics: An industrial perspective. 2024; 205, p. 115156.

- De, R.; Mahata, M.K.; Kim, K.T.J.A.S. Structure-based varieties of polymeric nanocarriers and influences of their physicochemical properties on drug delivery profiles. 2022, 9(10), 2105373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).