Submitted:

17 January 2026

Posted:

19 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bennett, N.J.; Roth, R.; Klain, S.C.; Chan, K.; Christie, P.; Clark, D.A.; Cullman, G.; Curran, D.; Durbin, T.J.; Epstein, G. Conservation Social Science: Understanding and Integrating Human Dimensions to Improve Conservation. Biological conservation 2017, 205, 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Toit, J.T.; Cross, P.C.; Valeix, M. Managing the Livestock–Wildlife Interface on Rangelands. In Rangeland systems: Processes, management and challenges; Springer International Publishing Cham, 2017; pp. 395–425. [Google Scholar]

- Moss, L.A.G.; Glorioso, R.S. Global Amenity Migration. Transforming Rural Culture, Economy &Landscape; New Ecology Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Matarrita-Cascante, D.; Veintimilla, C.; Brooke, C.; Treadwell, M.; Castro, C. Amenity Migration for Land Stewardship: Getting to Know the New Faces in Ranching. Rangelands 2025, 47, 151–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrams, J.B.; Gosnell, H.; Gill, N.J.; Klepeis, P.J. Re-Creating the Rural, Reconstructing Nature: An International Literature Review of the Environmental Implications of Amenity Migration. Conservation and society 2012, 10, 270–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krannich, R.S.; Luloff, A.E.; Field, D.R. People, Places and Landscapes: Social Change in High Amenity Rural Areas; Springer Science & Business Media, 2011; ISBN 978-94-007-1263-8. [Google Scholar]

- Lekies, K.S.; Matarrita-Cascante, D.; Schewe, R.; Winkler, R. Amenity Migration in the New Global Economy: Current Issues and Research Priorities. Society & Natural Resources 2015, 28, 1144–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, G.; Matarrita-Cascante, D.; Rodriguez, M.F. International Amenity Migration: Implications for Integrated Community Development Opportunities. In Rural Wealth Creation as a Sustainable Economic Development Strategy; Routledge, 2017; pp. 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, A.J.; Knight, R.L.; Marzluff, J.M.; Powell, S.; Brown, K.; Gude, P.H.; Jones, K. Effects of Exurban Development on Biodiversity: Patterns, Mechanisms, and Research Needs. Ecological Applications 2005, 15, 1893–1905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yung, L.; Belsky, J.M. Private Property Rights and Community Goods: Negotiating Landowner Cooperation Amid Changing Ownership on the Rocky Mountain Front. Society & Natural Resources 2007, 20, 689–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosnell, H.; Abrams, J. Amenity Migration: Diverse Conceptualizations of Drivers, Socioeconomic Dimensions, and Emerging Challenges. GeoJournal 2011, 76, 303–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, R.L.; Matarrita-Cascante, D. Exporting Consumption: Lifestyle Migration and Energy Use. Global Environmental Change 2020, 61, 102026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosnell, H.; Travis, W.R. Ranchland Ownership Dynamics in the Rocky Mountain West. Rangeland Ecology & Management 2005, 58, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gosnell, H.; Haggerty, J.H.; Travis, W.R. Ranchland Ownership Change in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, 1990–2001: Implications for Conservation. Society & Natural Resources 2006, 19, 743–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haggerty, J.H.; Epstein, K.; Gosnell, H.; Rose, J.; Stone, M. Rural Land Concentration & Protected Areas: Recent Trends from Montana and Greater Yellowstone. Society & Natural Resources 2022, 35, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, K.; Haggerty, J.H.; Gosnell, H. With, Not for, Money: Ranch Management Trajectories of the Super-Rich in Greater Yellowstone. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 2022, 112, 432–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veintimilla, C.; Matarrita-Cascante, D.; Treadwell, M.; Brooke, C. From Consumers to Stewards: Understanding the Spectrum of Amenity Migrants. Society and Natural Recources In Press.

- Lopez, A.; Barrientos, D. Updates and trends in landowner demographics and their relationship with wildlife management: A Texas Landowner Survey report; Texas A&M Natural Resources Institute: College Station, TX, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cumming, G.S.; Cumming, D.H.; Redman, C.L. Scale Mismatches in Social-Ecological Systems: Causes, Consequences, and Solutions. Ecology and society 2006, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poiani, K.A.; Richter, B.D.; Anderson, M.G.; Richter, H.E. Biodiversity Conservation at Multiple Scales: Functional Sites, Landscapes, and Networks. BioScience 2000, 50, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiens, J.A. Spatial Scaling in Ecology. Functional Ecology 1989, 3, 385–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez-Gimenez, M.E.; Ballard, H.L.; Sturtevant, V.E. Adaptive Management and Social Learning in Collaborative and Community-Based Monitoring: A Study of Five Community-Based Forestry Organizations in the Western USA. Ecology and Society 2008, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmer, H.; Derner, J.D.; Fernández-Giménez, M.E.; Briske, D.D.; Augustine, D.J.; Porensky, L.M. Collaborative Adaptive Rangeland Management Fosters Management-Science Partnerships. Rangeland Ecology & Management 2018, 71, 646–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGranahan, D.A. NATURAL AMENITIES DRIVE RURAL POPULATION CHANGE. Available online: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/record/33955/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Cordell, H.K. Natural Amenities and Rural Population Migration. General technical report SRS 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hjerpe, E.; Hussain, A.; Holmes, T. Amenity Migration and Public Lands: Rise of the Protected Areas. Environmental Management 2020, 66, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hjerpe, E.; Armatas, C.A.; Haefele, M. Amenity-Based Development and Protected Areas in the American West. Land Use Policy 2022, 116, 106064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Texas A; M Natural Resources Institute. Featured Map: Fragmentation Risk Index. Available online: https://nri.tamu.edu/blog/2020/march/featured-map-fragmentation-risk-index/ (accessed on 6 March 2020).

- Brown, S. Texas Rural Land Sales Spike with Pandemic. The Dallas Morning News 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, F. Pandemic Drives Rural Land Sales In Texas. Available online: https://www.houstonpublicmedia.org/articles/news/business/2021/04/01/394764/pandemic-pushes-rural-land-sales-in-texas/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Haslag, P.; Weagley, D. From L.A. to Boise: How Migration Has Changed During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 2024, 59, 2068–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, J.K.; Winkler, R.L.; Mockrin, M.H. Changes to Rural Migration in the COVID-19 Pandemic. Rural Sociology 2024, 89, 130–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theophilus, A.; Ulrich-Schad, J.; Flint, C.; Epperson, E. Amenity Migration and Community Wellbeing in Washington’s Kittitas County Post-COVID-19 Pandemic. Rural Sociology 2025, 90, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matarrita-Cascante, D.; McCord, S.; Landaverde, R.; Veintimilla, C. Beyond the Productivist Ideal: Understanding the Drivers of Land Stewardship Among Amenity Migrants Transforming Agrifood Systems in Rangelands. Agriculture and Human Values 2026, 43(1), 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruger, L.E.; Mazza, R.; Stiefel, M. Amenity Migration, Rural Communities, and Public Lands. In Forest Community Connections; Taylor & Francis Group, 2008; p. 292. ISBN 978-1-936331-45-1. [Google Scholar]

- Dearien, C.; Rudzitis, G.; Hintz, J. The Role of Wilderness and Public Land Amenities in Explaining Migration and Rural Development in the American Northwest. Green, GP, Deller, SC and Marcouiller, DW Amenities and Rural Development: Theory, Methods and Public Policy 2005, 113–128. [Google Scholar]

- Fahrig, L. Effects of Habitat Fragmentation on Biodiversity. Annual review of ecology, evolution, and systematics 2003, 34, 487–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindenmayer, D.; Hobbs, R.J.; Montague-Drake, R.; Alexandra, J.; Bennett, A.; Burgman, M.; Cale, P.; Calhoun, A.; Cramer, V.; Cullen, P.; et al. A Checklist for Ecological Management of Landscapes for Conservation. Ecology Letters 2008, 11, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opdam, P.; Steingröver, E.; Rooij, S. van Ecological Networks: A Spatial Concept for Multi-Actor Planning of Sustainable Landscapes. Landscape and Urban Planning 2006, 75, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clendenning, G.; Field, D.R.; Kapp, K.J. A Comparison of Seasonal Homeowners and Permanent Residents on Their Attitudes toward Wildlife Management on Public Lands. Human dimensions of wildlife 2005, 10, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrom, E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action; Cambridge University Press, 1990; ISBN 978-0-521-40599-7. [Google Scholar]

- Briske, D.D. Conservation Benefits of Rangeland Practices: Assessment, Recommendations, and Knowledge Gaps; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sayre, N.F. Viewpoint: The Need for Qualitative Research to Understand Ranch Management. rama.1 2004, 57, 668–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmet Jones, R.; Mark Fly, J.; Talley, J.; Ken Cordell, H. Green Migration into Rural America: The New Frontier of Environmentalism? Society &Natural Resources 2003, 16, 221–238. [Google Scholar]

- Hurst, Z.; Kreuter, U. Place-Based Identities of Landowners: Implications for Wildlife Conservation. Society & Natural Resources 2021, 34, 659–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meadows, J.; Emtage, N.; Herbohn, J. Engaging Australian Small-Scale Lifestyle Landowners in Natural Resource Management Programmes – Perceptions, Past Experiences and Policy Implications. Land Use Policy 2014, 36, 618–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikutegbe, V.; Gill, N.; Klepeis, P. Same but Different: Sources of Natural Resource Management Advice for Lifestyle Oriented Rural Landholders. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 2015, 58, 1530–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argent, N.; Tonts, M.; Jones, R.; Holmes, J. Amenity-Led Migration in Rural Australia: A New Driver of Local Demographic and Environmental Change? In Demographic change in Australia’s rural landscapes: implications for society and the environment; Springer, 2010; pp. 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Van Auken, O.W. Causes and Consequences of Woody Plant Encroachment into Western North American Grasslands. Journal of Environmental Management 2009, 90, 2931–2942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, S.; Schimel, D.S.; Holland, E.A. Mechanisms of Shrubland Expansion: Land Use, Climate or CO2? Climatic Change 1995, 29, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, L.W.; Van Druff, L.W.; Luniak, M. Managing Urban Habitats and Wildlife. Techniques for wildlife investigations and management 2005, 714–739. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, M.H.; Becker, D.J.; Hall, R.J.; Hernandez, S.M. Wildlife Health and Supplemental Feeding: A Review and Management Recommendations. Biological Conservation 2016, 204, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, C.; Fenwick, N.; Lombard, A.; Cartwright, B.; Dubois, S.; Carter, S.; Baker, L.; Fraser, D.; Grogan, A.; Baker, S. International Consensus Principles for Ethical Wildlife Control; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Post, C.W. Heritage, Amenity, and the Changing Landscape of the Rural American West. Journal of Cultural Geography 2013, 30, 328–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooden, J.; Moir, F.C. Consensus, Clusters, and Trade-Offs in Wildlife-Friendly Ranching: An Advance Analysis of Stakeholder Goals in Northern Mexico. Biological Conservation 2019, 236, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, S.K.; McDuff, M.D.; Monroe, M.C. Conservation Education and Outreach Techniques; Oxford University Press, 2015; ISBN 978-0-19-871668-6. [Google Scholar]

- Brunson, M.W.; Huntsinger, L. Ranching as a Conservation Strategy: Can Old Ranchers Save the New West? Rangeland Ecology & Management 2008, 61, 137–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepeis, P.; Gill, N.; Chisholm, L. Emerging Amenity Landscapes: Invasive Weeds and Land Subdivision in Rural Australia. Land Use Policy 2009, 26, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorice, M.G.; Conner, J.R.; Kreuter, U.P.; Wilkins, R.N. Centrality of the Ranching Lifestyle and Attitudes Toward a Voluntary Incentive Program to Protect Endangered Species. Rangeland Ecology & Management 2012, 65, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, I.; Teeter, L.; Butler, B. Characterizing Family Forest Owners: A Cluster Analysis Approach. for sci 2008, 54, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorice, M.G.; Kreuter, U.P.; Wilcox, B.P.; Fox, W.E. Classifying Land-Ownership Motivations in Central, Texas, USA: A First Step in Understanding Drivers of Large-Scale Land Cover Change. Journal of Arid Environments 2012, 80, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Texas Parks and Wildlife Department [TPWD. Landowner Incentive Program. Available online: https://tpwd.texas.gov/landwater/land/private/lip/ (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- Olliff, T.; Mordecai, R.; Cakir, J.; Thatcher, B.S.; Tabor, G.M.; Finn, S.P.; Morris, H.; Converse, Y.; Babson, A.; Monahan, W.B.; et al. Landscape Conservation Cooperatives: Working Beyond Boundaries to Tackle Large-Scale Conservation Challenges. The George Wright Forum 2016, 33, 149–162. [Google Scholar]

- Plummer, R.; Armitage, D.R. Charting the New Territory of Adaptive Co-Management: A Delphi Study. Ecology and Society 2007, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjelland, M. E.; Kreuter, U. P.; Clendenin, G. A.; Wilkins, R. N.; Wu, X. B.; Afanador, E. G.; Grant, W. E. Factors related to spatial patterns of rural land fragmentation in Texas. Environmental Management 2007, 40(2), 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostrom, E. Understanding Institutional Diversity; Princeton University Press, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ostrom, E. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social-ecological systems. Science 2009, 325, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreier, M. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice; SAGE Publications Ltd: London, UK, 2012; ISBN 978-1-84920-592-4. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, N.; Klepeis, P.; Chisholm, L. Stewardship among lifestyle oriented rural landowners. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management 2010, 53(3), 317–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, B.; Lane, R. How do amenity migrants learn to be environmental stewards of rural landscapes? Landscape and Urban Planning 2015, 134, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

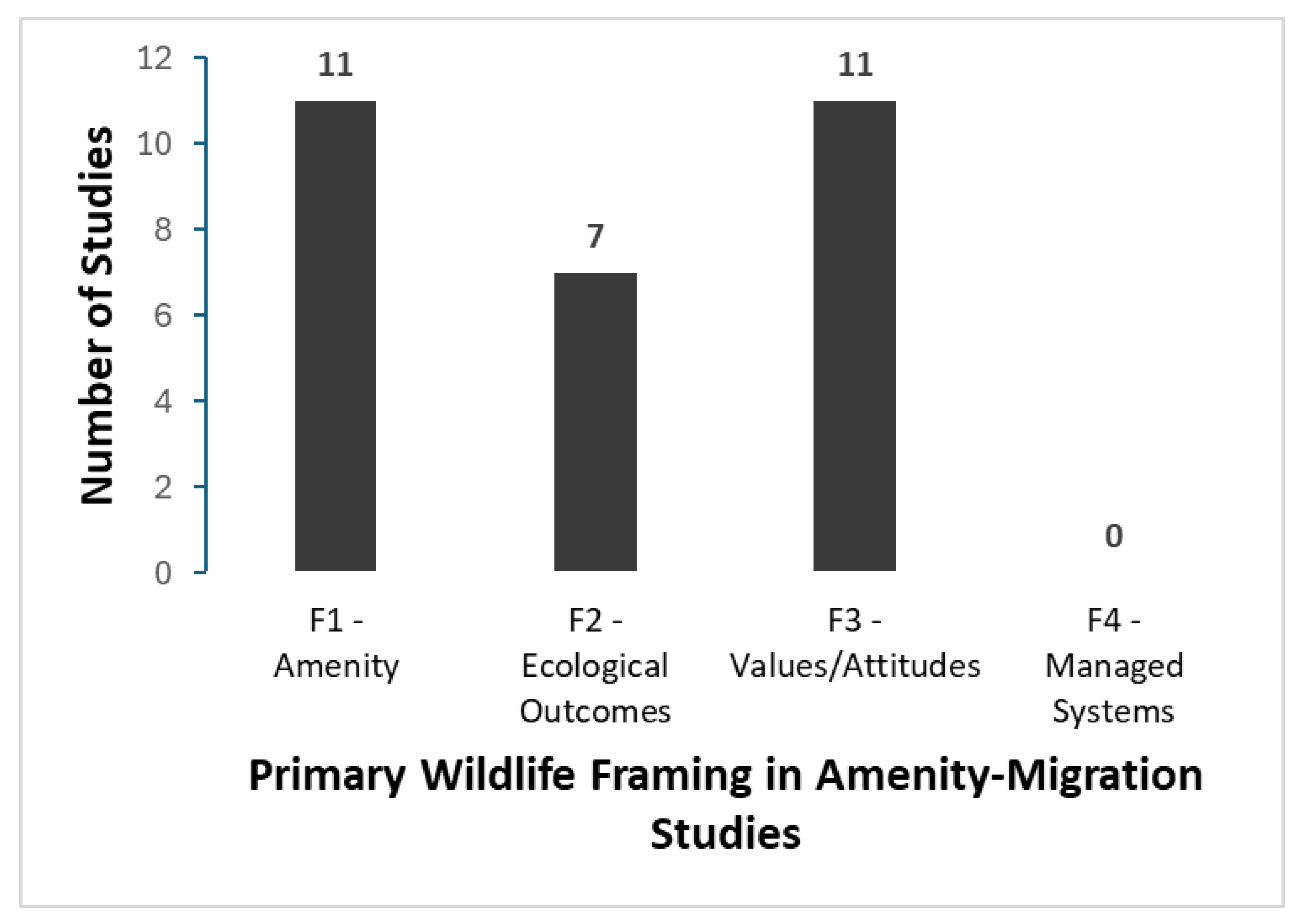

| Citation (Author, Year [Ref #]) | Wildlife Mentioned | Primary Wildlife Framing | Wildlife Management Analyzed |

| Moss & Glorioso 2014 [3] | Yes | F1 | No |

| Matarrita-Cascante et al. 2025 [4] | Yes | F3 | No |

| Abrams et al. 2012 [5] | Yes | F1 | No |

| Krannich et al. 2011 [6] | Yes | F1 | No |

| Lekies et al. 2015 [7] | Yes | F1 | No |

| Cortes et al. 2017 [8] | Yes | F1 | No |

| Hansen et al. 2005 [9] | Yes | F2 | No |

| Gosnell & Abrams 2011 [11] | Yes | F1 | No |

| Gosnell & Travis 2005 [13] | Yes | F2 | No |

| Gosnell et al. 2006 [14] | Yes | F2 | No |

| Haggerty et al. 2022 [15] | Yes | F2 | No |

| Epstein et al. 2022 [16] | Yes | F2 | No |

| Lopez & Barrientos 2024 [18] | Yes | F3 | No |

| Hjerpe et al. 2020 [26] | Yes | F1 | No |

| Hjerpe et al. 2022 [27] | Yes | F1 | No |

| Matarrita-Cascante et al. 2026 [34] | Yes | F3 | No |

| Kruger et al. 2008 [35] | Yes | F1 | No |

| Dearien et al. 2005 [36] | Yes | F1 | No |

| Clendenning et al. 2005 [40] | Yes | F3 | No |

| Emmet Jones et al. 2003 [44] | Yes | F3 | No |

| Hurst & Kreuter 2021 [45] | Yes | F3 | No |

| Meadows et al. 2014 [46] | Yes | F3 | No |

| Ikutegbe et al. 2015 [47] | Yes | F3 | No |

| Argent et al. 2010 [48] | Yes | F2 | No |

| Post 2013 [54] | Yes | F1 | No |

| Klepeis et al. 2009 [58] | Yes | F2 | No |

| Sorice et al. 2012 [59] | Yes | F3 | No |

| Gill et al. 2010 [69] | Yes | F3 | No |

| Cooke & Lane 2015 [70] | Yes | F3 | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).