1. Introduction

This paper presents a review of a classical problem in solar system astronomy, the formation of the Oort Cloud, which is currently under scrutiny from several points of view. Recently, some 30 international experts, researchers and students came together in Stockholm, Sweden, for two days of intense discussions on the invitation by the Swedish Royal Academy of Sciences at a meeting entitled Origin and Evolution of the Oort Cloud. The author of this paper was an initiator and organiser of this conference, and the paper is written as a way to summarise the impressions received from the various presentations and discussions at the conference. It is also a written version of a review talk given at the EAS 2025 Annual Meeting in Cork, Ireland, on June 25, 2025.

The paper is structured in four Sections, all of which are intimately related to the fundamental issue of formation of the Oort Cloud. It starts with a historical introduction and continues by a discussion of the dynamical links between the remote Oort Cloud population and the observed orbits of the new comets arriving from this reservoir. After this, the focus comes to the very issue of how the Oort Cloud was formed as a result of the processes that also led to the formation of our planetary system and the other small body populations. Finally, the evolution from this primordial Oort Cloud by Galactic sculpting into the one that we currently glimpse from the orbits of the new comets is briefly discussed.

2. Historical Remarks

2.1. Öpik [1]

Ernst Julius Öpik (1893-1985) was one of the most outstanding astronomers of the 20th century. In 1932 he published a paper with the title

Note on Stellar Perturbations on Nearly Parabolic Orbits [

1]. The gist of this paper was a mathematical analysis of how solar system objects moving on such orbits are perturbed – in a statistical sense – by the impulses received from stars passing through the Sun’s closest neighbourhood at high speeds. At the time, the existence of both long period meteors and long period comets was known, although it was not generally known in the astronomical community whether the orbits that Öpik discussed were inhabited by real objects.

However, Öpik proceeded to drawing some conclusions from his result that both meteors and observable comets, assumed to exist on nearly parabolic orbits, would statistically have their perihelion distances dramatically increased by stellar perturbations. Quoting from his 1932 paper:

If, however, among our observable objects there is a sensible proportion of meteors with R exceeding a.u., it may be only the result of a very peculiar distribution of meteoric matter at the outskirts of the solar system – a kind of a meteoric cloud, or shell...

Here,

R is the distance from the Sun. Öpik had made it clear that the word

meteors could also stand for

comets.

In fact, this was a theoretical prediction of the Oort Cloud based on an analysis of perturbations by passing stars on hypothetical solar system objects (meteors or comets) with orbits extending beyond au from the Sun. If Öpik had been aware that such objects do exist in the form of long period comets, he might well have written the Oort Cloud discovery paper 18 years before Oort. However, he was not aware of this fact.

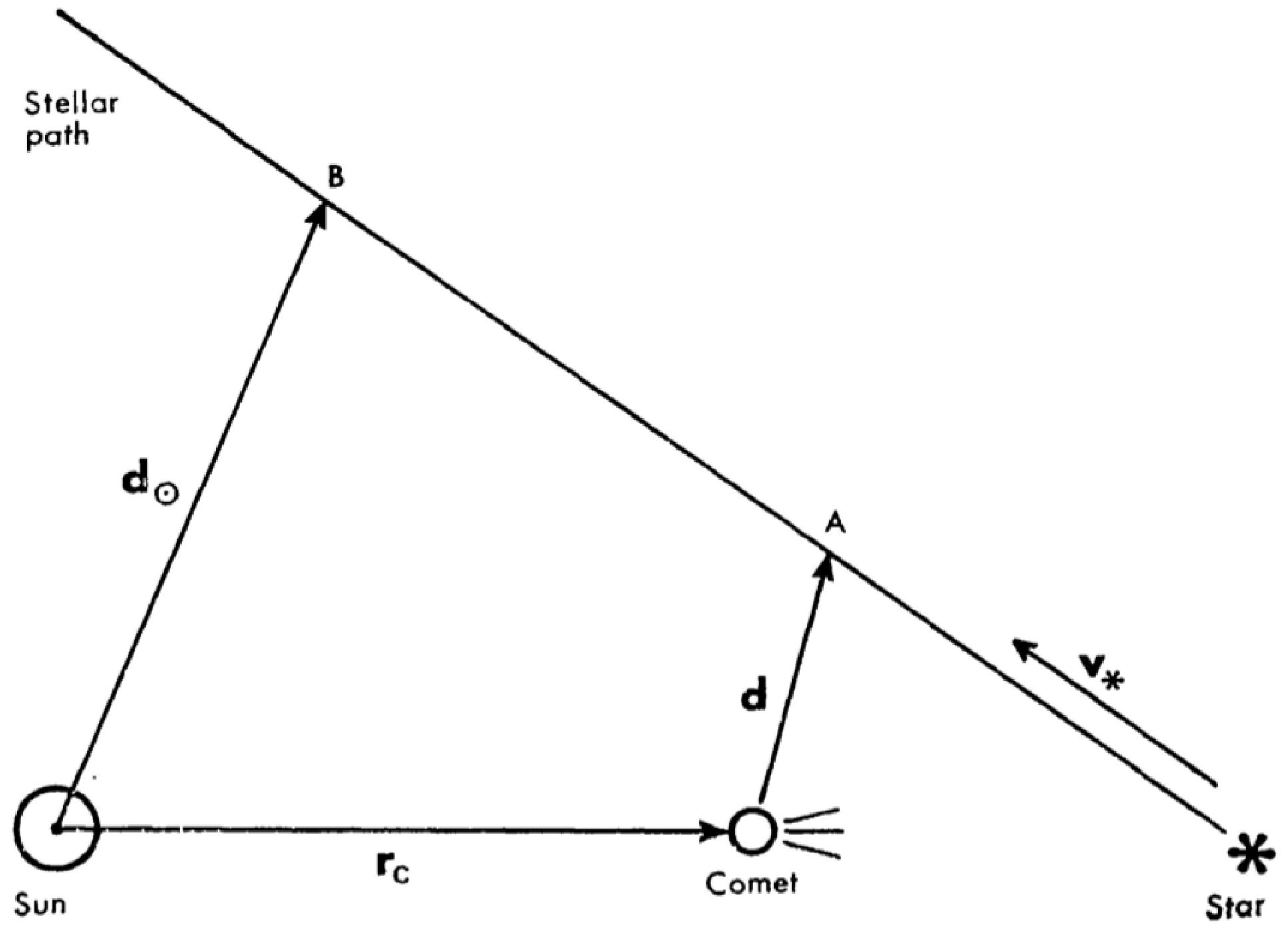

Let us now make a diversion into Öpik’s analysis. The velocities by which Galactic stars pass the solar system are known to be of order 10 km/s. An object moving on a nearly parabolic orbit more than au away from the Sun has a heliocentric velocity of about 400 m/s or less. This motivates the use of the classical impulse approximation, which means that the object is at rest with respect to the Sun, while the star passes on a straight line with constant speed (neglecting the small hyperbolic deflection due to the stellar masses).

Öpik showed that, in this situation, both the Sun and the object receive impulses

directed toward the respective closest points on the stellar trajectory. Here

G is the gravitational constant,

is the mass of the star, and

is the star’s velocity. This is illustrated in

Figure 1. See [

8] for further information.

In typical situations, the absolute value of is not large enough to unbind the comet from the Sun. However, the angular momentum perturbation is more important. The typical size of the above quantity is much larger than the transverse speeds correcponding to perihelion distances of au. Hence, such observable orbits represent an exceptional minority in a much larger population of objects with very large semi-major axes and, generally, much larger perihelion distances.

2.2. Oort [2]

The fundamental difference between Öpik’s paper and the classical paper [

2] by another eminent 20th century astronomer,

Jan Hendrik Oort (1900-1992), is that Oort had access to the observational data that Öpik was lacking. These consisted of orbit determinations of long period comets, painstakingly carried out in the 1910’s by Elis Strömgren (1870-1947) in Copenhagen and Gaston Fayet (1874-1967) in Paris. This work included the determination of osculating orbits near perihelion and backward integration of the orbital motions to a time before the comets plunged into the planetary system and experienced planetary perturbations. It was very important for settling the issue whether comets belong to the solar system or are captured visitors from interstellar space [

10].

Indeed, the solar system nature of these objects was securely confirmed by these determinations of

original orbits, but an equally important consequence was to be found by Oort [

2] in the paper

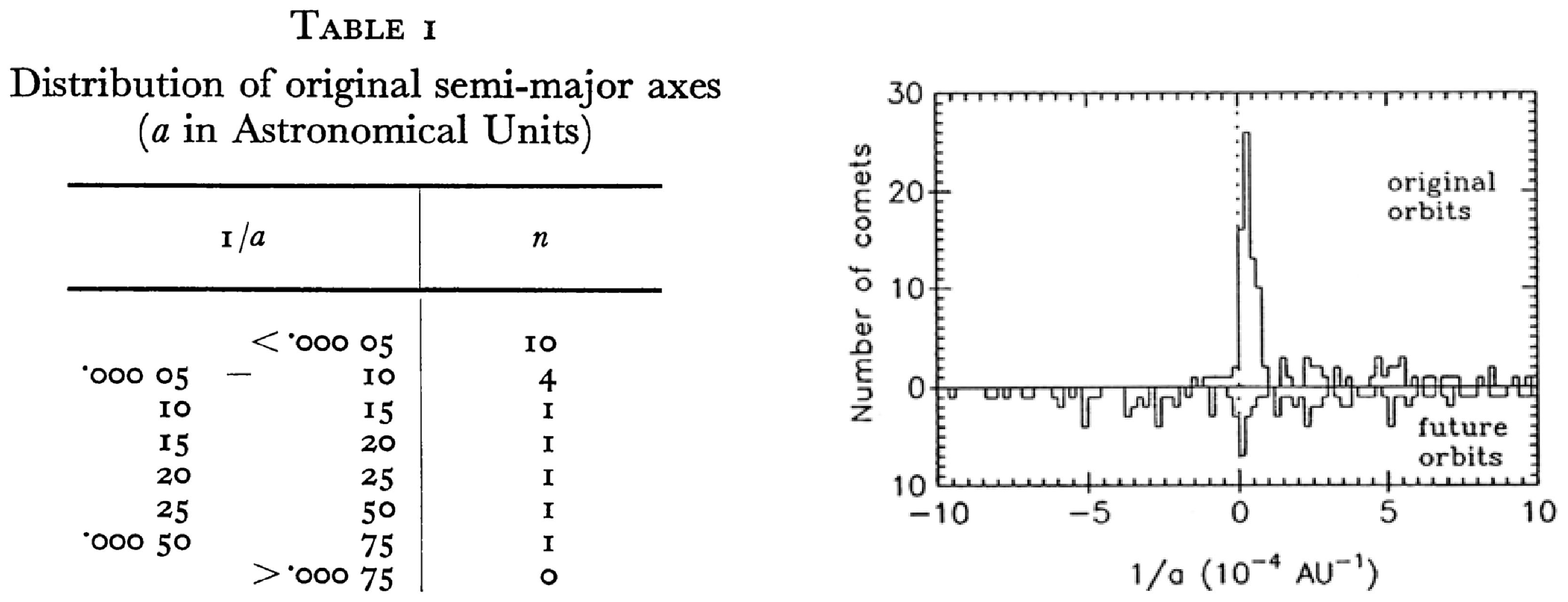

The structure of the cloud of comets surrounding the Solar System and a hypothesis concerning its origin. In

Figure 2 (left panel) we see a copy of a Table from this paper, which shows statistics of 19 original orbits of long period comets with regard to their reciprocal semi-major axes – a quantity that is proportional to the orbital energy. The remarkable feature of this Table is a large concentration to values in a narrow interval next to the parabolic limit, something that is often referred to as the

Oort spike.

The Oort spike was the necessary evidence, which allowed Oort to publish his paper with the

discovery of the remote comet reservoir that since then carries the name

Oort Cloud.

Figure 2 (right panel) carries a graphical illustration of the essential role of the Oort Cloud in comet dynamics. This was made about 40 years after Oort’s paper and uses a much larger sample of comet orbits determined with the aid of the modern computers of that time. We note the striking difference between the incoming and outgoing energy distributions. This is caused by the indirect perturbations of the orbits, mainly due to Jupiter,

i.e.the effect of the Sun’s motion around the solar system’s barycentre.

As a result, nearly half the comets are ejected from the solar system, thus becoming Galactic vagabonds. The rest of the comets (except for a small fraction staying in the spike) will return in a distant future on elliptic orbits resembling the wide tail from which the incoming spike stands out. However, the comets of the spike are newcomers. The meaning of this term has to be clarified. The orbits of the comets have clearly been modified by some external agent like stellar encounters on the way from a preceding perihelion at a larger distance. This means a supply of comets into the inner solar system, while there is also an important loss of such comets due to planetary perturbations.

While the parabolic limit at

is absolutely obvious as a limit to the Oort spike, the reason for the other limit where the spike borders on the extended background of returning comets has been less trivial. Ever since the earliest time, the sharp contrast between the spike and the background was discussed in terms of

comet fading or some specific evolutionary behaviour of comet nuclei (

e.g.[

13,

14,

15]). This discussion has been ongoing until recent times, but it does not address the question, if the sharp edge of the spike reveals a true inner edge of the Oort Cloud such that the cloud appears more like a shell where semi-major axes less than

au are lacking.

2.3. Hills [3]

In 1981, this question was answered by

Jack Gilbert Hills (b. 1943) in a famous paper entitled

Comet showers and the steady-state infall of comets from the Oort Cloud [

3]. From the abstract of this paper we quote:

The appearance of an inner edge to the Oort comet cloud at a semimajor axis of AU is an observational artifact.

Thus, we have no reason at all to think that the cloud is devoid of comets with smaller semi-major axes or nearly so. Such comets may very well exist in huge numbers, but these are simply unable to reach observable orbits in the way that Oort Cloud comets do.

To understand this, the reader is once more referred to

Figure 2 (right panel). This shows that newcomers from the Oort Cloud are very efficiently tidied away through Jupiter’s perturbations. Nearly one half are ejected from the solar system, and nearly all the rest get captured into more strongly bound orbits to become returning comets in due time. This effect of Jupiter, and to a smaller degree also Saturn, reminds of the

loss cone concept of space physics identifying the region of velocity space of magnetospheric ions, where these will be lost by hitting the Earth’s atmosphere. In the solar system, we have somewhat of a loss cone as well, affecting the production of observable newcomers from the Oort Cloud. This can be identified as the region of velocity space, where the transverse component is small enough to yield a perihelion distance smaller than than the orbital radii of Jupiter or Saturn.

Traditionally, comets were very rarely observed with perihelia near or beyond Jupiter’s orbit simply because the discovery techniques were not able to face the challenge of detecting such very faint objects. Hence, the comets of

Figure 2 had perihelia much closer to the Sun and, moreover, they must have had preceding perihelia safely outside the loss cone. However, similar comets with semi-major axes less than

au would only very rarely become observable since the perihelia are not perturbed strongly enough to avoid being cleaned away by Jupiter on the way toward observability.

Let us now show why this is the case. Most stellar perturbations that contribute to the infall of new Oort Cloud comets arise from relatively distant fly-bys, where Eq. (1) can be replaced by an approximate, tidal formula

where

is the distance from the Sun to the comet,

is an orientational angle that can take any value, and

is the Sun’s distance from the closest point on the star’s trajectory. If we use this to derive the angular momentum perturbation from

we see that its absolute value is

. For the total result of a large number of stellar fly-bys with different values of the parameters over a given time, we thus have

in terms of the comet’s semi-major axis

. For the perturbation

of the perihelion distance we get a statistical expectance

. Finally, taking for the time one orbital period

, we get an expected change in

per orbital period:

This strong dependence of the typically expected perturbation of the perihelion distance per orbital period on the semi-major axis explains why there is a sharp limit between too small and adequate values of the semi-major axes concerning the production of observable newcomers from the Oort Cloud. Note that this discussion holds for the normal circumstances, where stellar encounters are limited to the region outside or in the outer parts of the Oort Cloud, but no stars penetrate inside the inner core postulated by Hills [

3]. This inner core is often referred to as the

Hills Cloud.

However, once more quoting the abstract of [

3]:

Comets with semimajor axes less than AU appear in the inner solar system only in intense bursts or showers which last for a few orbital periods after the close passage of a star close to the Sun.

Such passages, where stars penetrate the Hills Cloud, are statistically expected to occur only once per hundred million years. The resulting

comet showers were predicted by Hills and his prediction has been verified in several papers by simulating models of the Oort and Hills Clouds [

16,

17,

18,

19].

Finally, we note that Hills [

3] also wrote that, on average over a Gyr time scale, more comets arrive from the Oort Cloud inner core than from the classical, outer part (nowadays often called the "outer halo"). Moreover, in recent literature, the inner core has become more and more of a research topic in itself with connections to both the delivery of observable Oort Cloud comets and the formation and long term evolution of the Oort Cloud, as will be evident in the following Sections.

3. The Supply of Comets from the Oort Cloud

3.1. A Fundamental Problem

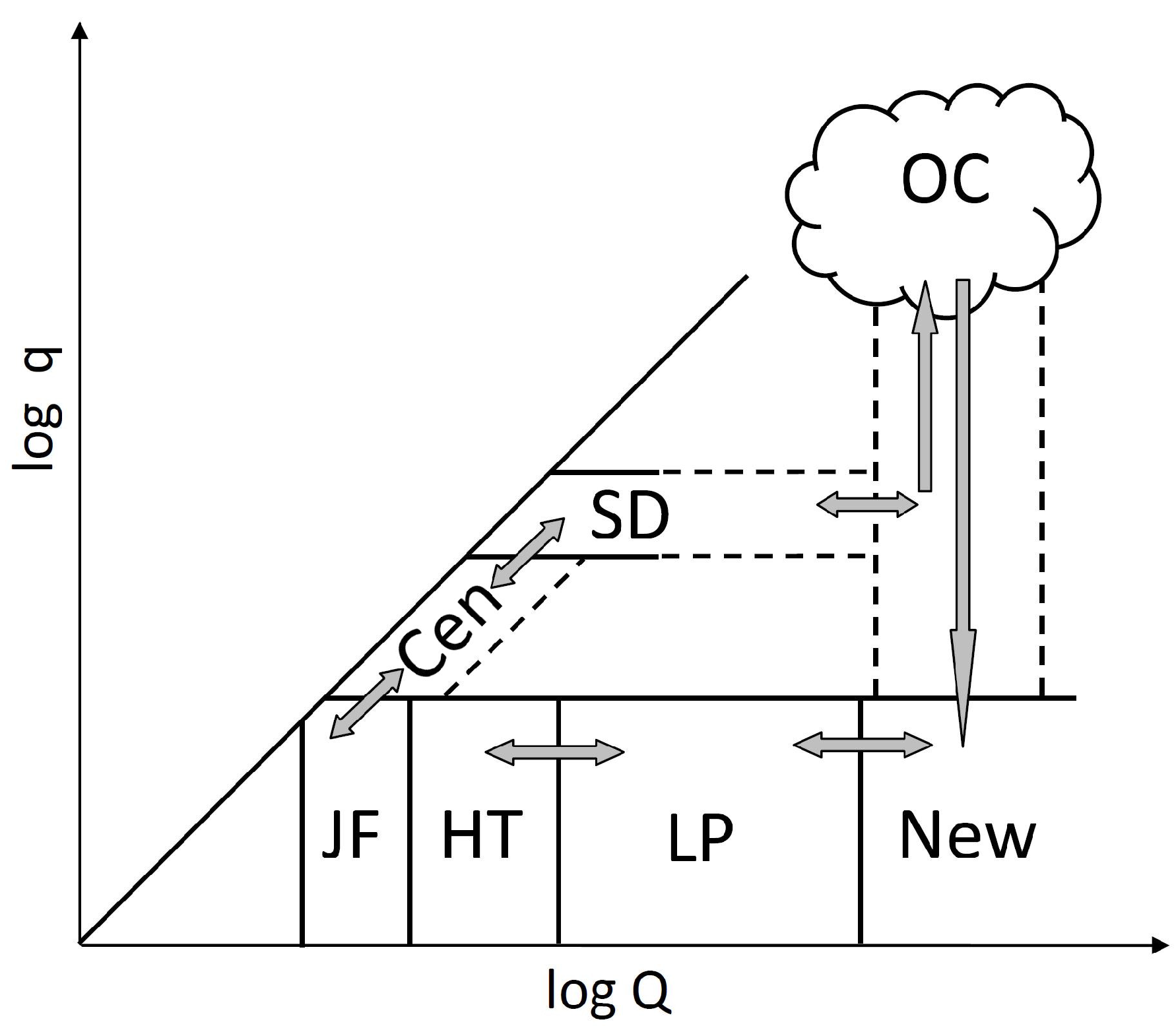

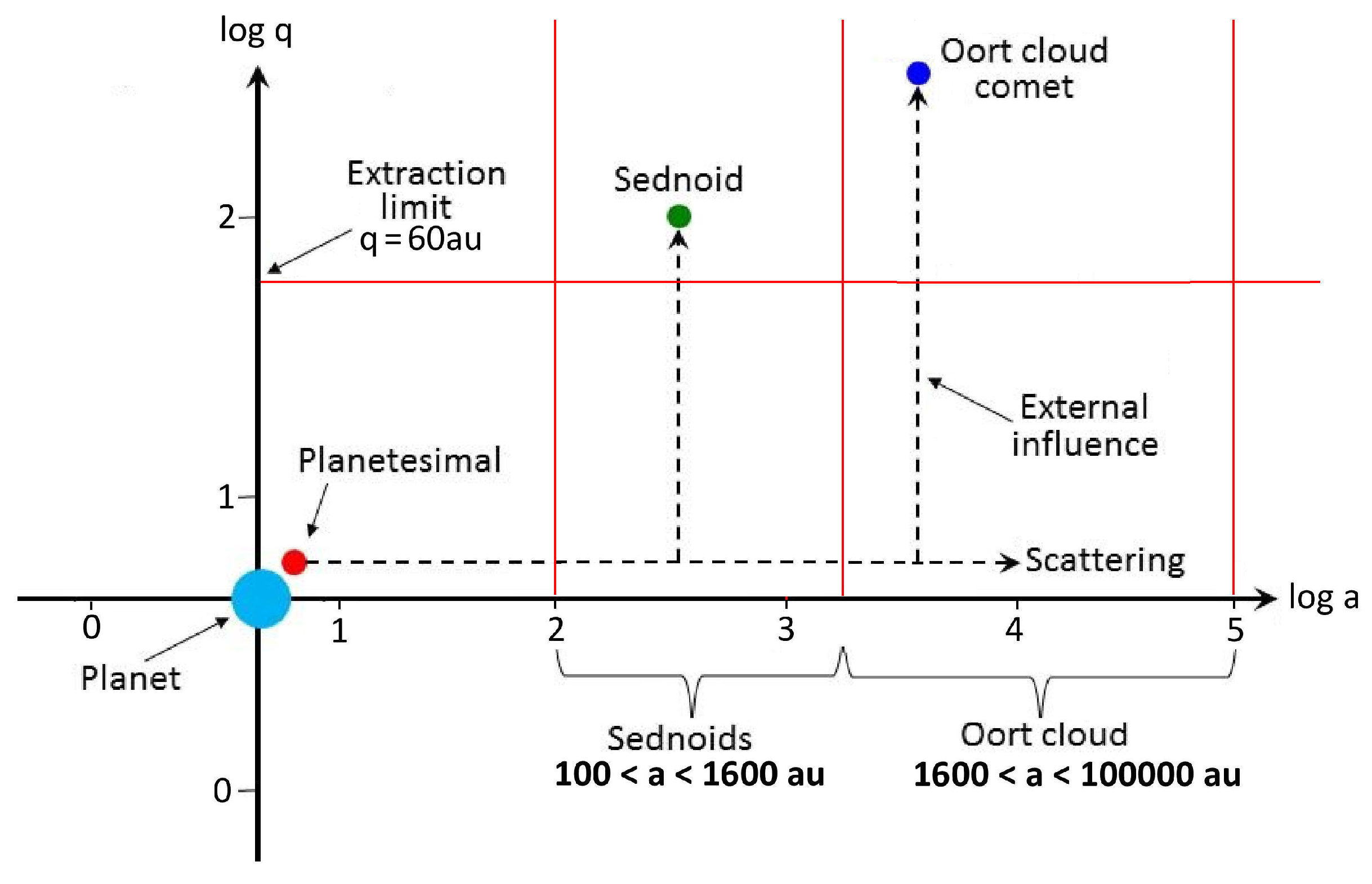

The cartoon in

Figure 3 presents a road map of cometary dynamics in the solar system. Though not fully comprehensive, it shows the main routes followed by comets between the different orbital categories usually recognised for observed or inferred objects. The "log" notations for perihelion and aphelion distances on the axes are not meant to be interpreted strictly.

As in any Hamiltonian system, the arrows are bidirectional, but in practice the transfer is mainly unidirectional though the direction may change as the solar system evolves. We shall now concentrate on the rightmost arrow, which currently indicates the supply of newcomers from the Oort Cloud into observable orbits but during the solar system’s infancy may have indicated a supply of icy planetesimals from the giant planet region or beyond into a forming Oort Cloud, as we shall see below.

If we know the efficiency of the angular momentum exchange, which allows for the supply of new comets, and if we are able to determine the rate of perihelion passages by new comets with good precision, we can use this to estimate the population size of the Oort Cloud. This, in turn, is its most fundamental property, because it plays a central role in discussions of how the structure was once formed and how it relates to the solar nebula and its planetesimal populations.

Recent times have brought improved knowledge of both the arrival rate of new comets and the current stellar encounter rate. Concerning the arrival rate, the coming on line of new sky surveys in search for objects often different from active comets has been of major importance. These are both deep and well characterised in terms of limiting magnitude and sky coverage, thus greatly facilitating corrections for discovery bias. A few early examples concern search programs aiming at better characterisation of the Near-Earth Object (NEO) population, like the Catalina Sky Survey and LINEAR

1 [

20]. As an example, Francis [

21] used data from the LINEAR survey during a three years period for a re-evaluation of the long period comet flux, finding a much lower value than had been obtained using historic visual comet observations by Everhart [

22] and Hughes [

23]. We can now note the inauguration of the LSST project

2, which holds great promise for the future discoveries of long period comets and the charting of the Oort Cloud newcomer flux out to larger perihelion distances than hitherto possible.

Concerning the stellar encounter rate, the solar neighbourhood of the Galactic disc has been scrutinised by astrometric satellites like

Hipparcos in the 1990’s [

24] and

Gaia since 2013 [

25]. Based on Hipparcos data, García-Sánchez et al. [

26] determined encounter frequencies, solar apex velocities and spherical velocity dispersions for 13 stellar categories, and these were used in Oort Cloud simulations by Rickman et al. [

5] to characterise the supply rate of new comets caused by stellar encounters. We have yet to see, what further improvements will follow from the Gaia data.

However, although the above may sound optimistic, a major problem remains. This problem is that we can count observed perihelion passages by Oort Cloud newcomers as a function of a characteristic property of the comets, and this is readily available in the form of brightness (e.g.as expressed by an absolute magnitude), but we really want to know the sizes of the nuclei or, preferably, the masses for a proper characterisation of the Oort Cloud. Obtaining such knowledge is, in fact, much easier said than done. From the limited amount of reliable observational data on nuclear sizes and production rates of luminous material (gas and dust), it appears that there is an enormous variation of the mass to brightness ratio of individual comets, and there is no mass-luminosity relation. We shall come back to this problem in Sect. 4.

In conclusion, even if we would arrive at quite a reliable estimate of the number of comets in the Oort Cloud, the mass of the Oort Cloud still remains poorly known. Tha mass of the Hills Cloud is of course even less well determined.

3.2. The Galactic Tide

We have indeed arrived at a serious problem, but let us now return to the issue of the transfer rate between the Oort Cloud and the new comets. In the mid-1980’s it became clear that Oort Cloud dynamics includes perturbations by the Galactic tide as an important component. Already about 20 years earlier, Chebotarev [

27] had studied the effect of the Galaxy as a distant point mass on the Oort Cloud, and another study of the same kind was carried out by Byl [

28]. However, the breakthrough came with a seminal paper by Heisler and Tremaine [

4]. This paper addressed in particular the tidal action on distant comets by the

Galactic disc.

In this case we use a one-dimensional model of the Galactic potential. Only the distance from the midplane counts and the disc has an infinite extent in the other directions. The potential is at a minimum in the midplane and increases in both directions away from this plane. If we use

z for the Cartesian coordinate perpendicular to the plane, the Poisson equation can be written

where

U is the potential and

is the mass density of the disc. For a homogeneous disc, we see that

is a function with a positive curvature, and thus, the associated force field is directed toward the midplane and increases away on both sides. Hence, if the Sun is situated somewhere in the disc and a comet is situated close to the Sun at a somewhat different distance from the plane, the differential gravity of the disc – or disc tide – is always directed toward the level of the Sun. Thus, we are dealing with a

compressive tide perturbing the comet’s orbital motion around the Sun.

We note that it is possible to describe the plane-parallel disc as the superposition of an infinite number of circular rings, and the gravity of the disc is hence the superposition of all the ring gravities. This makes it evident that the dynamical effect of the Galactic disc on objects orbiting around the Sun is reminiscent of a well-known secular effect on the motion of observed comets moving in the realm of the planetary system – the von Zeipel-Lidov-Kozai effect. This arises from the secular, perturbing effect of Jupiter on a circular orbit around the Sun as an analogue of the circular rings making up the Galactic disc. The basic feature of this effect is a coupled oscillation of the orbital eccentricity and inclination.

After the mean anomaly has been averaged out to isolate the secular dynamics, the tidal force of the Galactic disc is regular and integrable. One integral is the Hamiltonian or, alternatively, the semi-major axis (a). The other integral is the component of the orbital angular momentum perpendicular to the disc plane (). The existence of these isolating integrals allows one to develop an analytical expression for the secular changes of the orbits, and the result is that both eccentricity (e) and Galactic inclination (i) oscillate with the same frequency, set by the variation of the Galactic argument of perihelion (). This comes from an oscillating behaviour of the angular momentum such that sometimes its magnitude is small (e is large) and the Galactic inclination is low, and sometimes the magnitude is large (e is small) and the Galactic inclination is large.

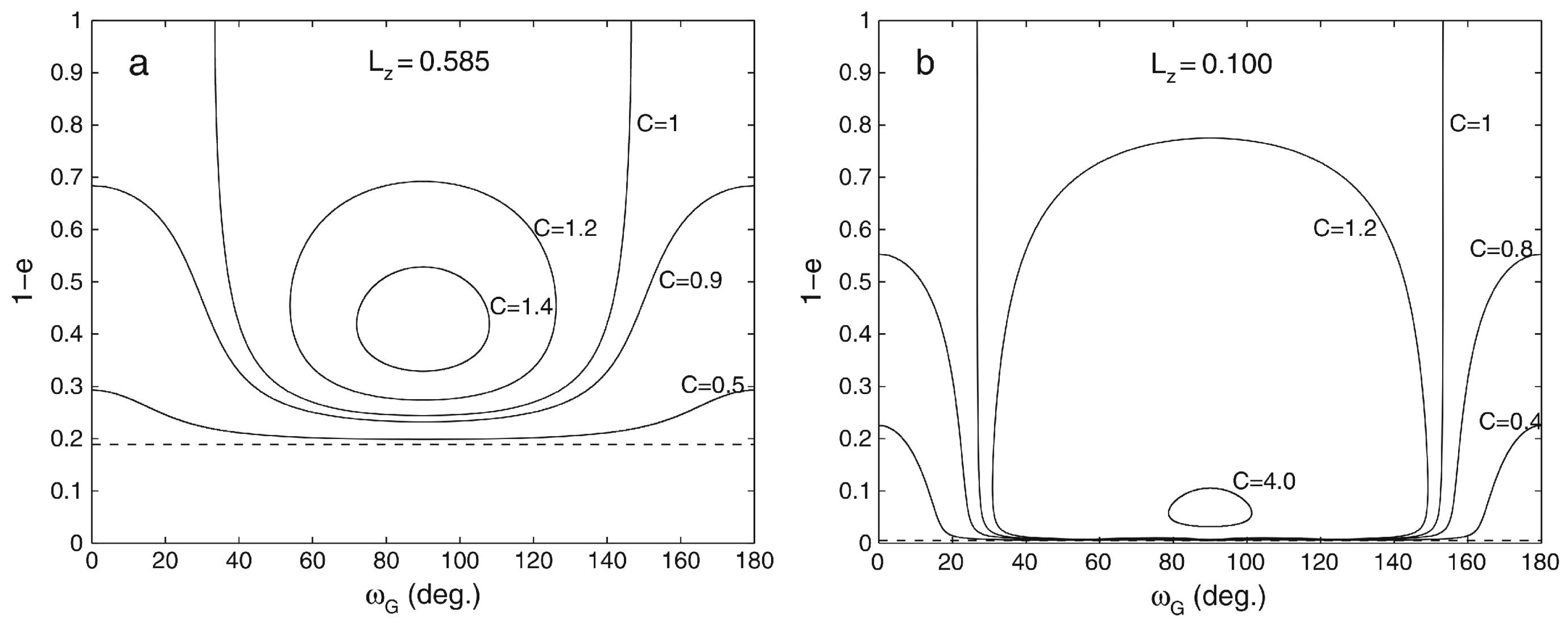

The two diagrams in

Figure 4 show Poincaré maps of the variations of

e and

for different values of the Hamiltonian, given two choices of

.

Figure 4a (left panel) illustrates the fact that

e may show large variations but is prevented from approaching unity by a too large assumed value of

. On the other hand, as shown by

Figure 4b (right panel), assuming a small enough value of

allows

e to come very close to unity. Note that an orbit with

au and

au has

, so the value of

is critical for the possibility of a comet to become observable. We conclude that, for the purpose of comet supply, the tide works only for small values of

and most efficiently (largest amplitudes of the

e oscillation) for Hamiltonians close to the separatrix between

libration and circulation.

Obviously, we now have identified two mechanisms for angular momentum transfer: one regular (the Galactic disc tide) and one chaotic (stellar fly-bys). It may then seem natural to ask, who is the winner of the competition. In fact, the answer is the Galactic tide [

4], and this is verified by observations showing that the Galactic latitude of perihelion of new Oort Cloud comets prefers values close to

[

29]. Such a preference is predicted by the theory of the Galactic disc tide but not by stellar perturbations. However, the situation is really more complex and more interesting, as we shall now see.

3.3. The Tide/Stars Synergy and Planetary Perturbations

In 2008, I and my collaborators (Marc Fouchard, Christiane Froeschlé and Giovanni Valsecchi) reported on an investigation of how the supply of observable comets works when supported by two different mechanisms [

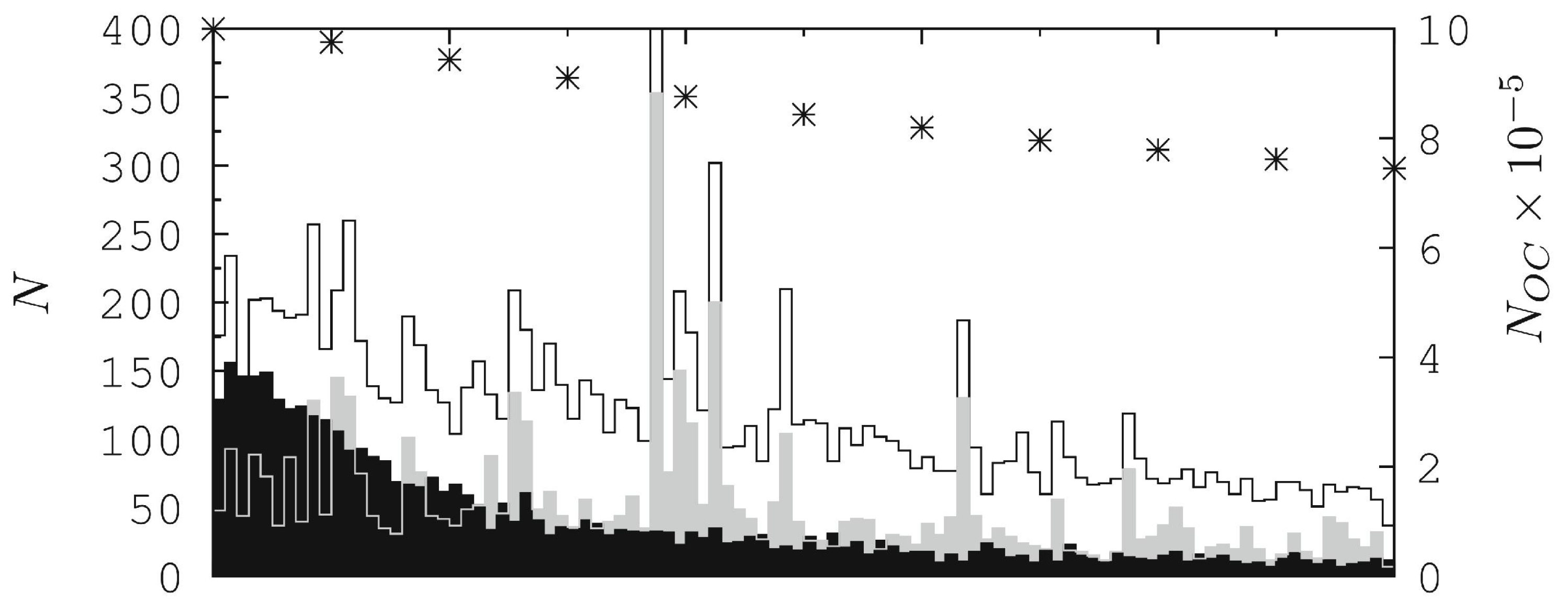

5]. To this end we carried out massive simulations of the Oort Cloud from its conception in the young solar system until the present time – the time span actually considered was 5 Gyr. The primordial cloud was modelled using a broad energy range comprising both the classical Oort Cloud and the inner Hills Cloud. The inclination distribution was isotropic and the eccentricity distribution was assumed to be thermalised. We studied the effects of three different dynamical models: one including only the Galactic tide, one including only stellar encounters, and one that combined both mechanisms together.

Figure 5 shows the results of this exercise. The tide alone is very efficient in providing observable comets in the beginning, but soon enough (

i.e.within about 1 Gyr) the favourable orbits are strongly depleted due to the ejection of the new comets by planetary perturbations. As to the stars alone, this model is generally quite inefficient and only becomes important on rare occasions, when comet showers occur. On the other hand, the striking result is that the only way to guarantee a reasonable rate of supply at the current time is to have the tides and stars collaborate. The true mechanism of supply is a

synergy between the two separate mechanisms. The stars help to replenish the favourable orbits, thus maintaining a high tidal supply rate. On the other hand, the tide provides a constant source of comets with part of the transfer finished, thus facilitating for stars to accomplish the rest of the task.

Let us now consider the asterisks in

Figure 5. These show the cumulative depletion of the entire Oort Cloud as a function of time. This is not dramatic but still significant, reaching more than 20% (

i.e.more than

comets), and is partly due to the progressive planetary ejection of new comets. However, this is only a minor part. We note that the average supply rate of the combined model, which can be taken as the loss rate due to planetary perturbations, yields a total of only about

comets over 5 Gyr out of an initial population of one million,

i.e.about 1%. We also see that the spikes caused by comet showers due to the closest fly-bys do not contribute much more than 1%. Hence, most of the Oort Cloud depletion is due to encounters with massive stars, which yield large enough impulses to the Sun to initiate an important, global loss of comets from the outer parts of the cloud [

19].

A further consequence of interest is that our solar system has thus sent out a substantial part of its primordial Oort Cloud during its current lifetime mostly by means of externally triggered erosion (see further discussion in Sect. 5).

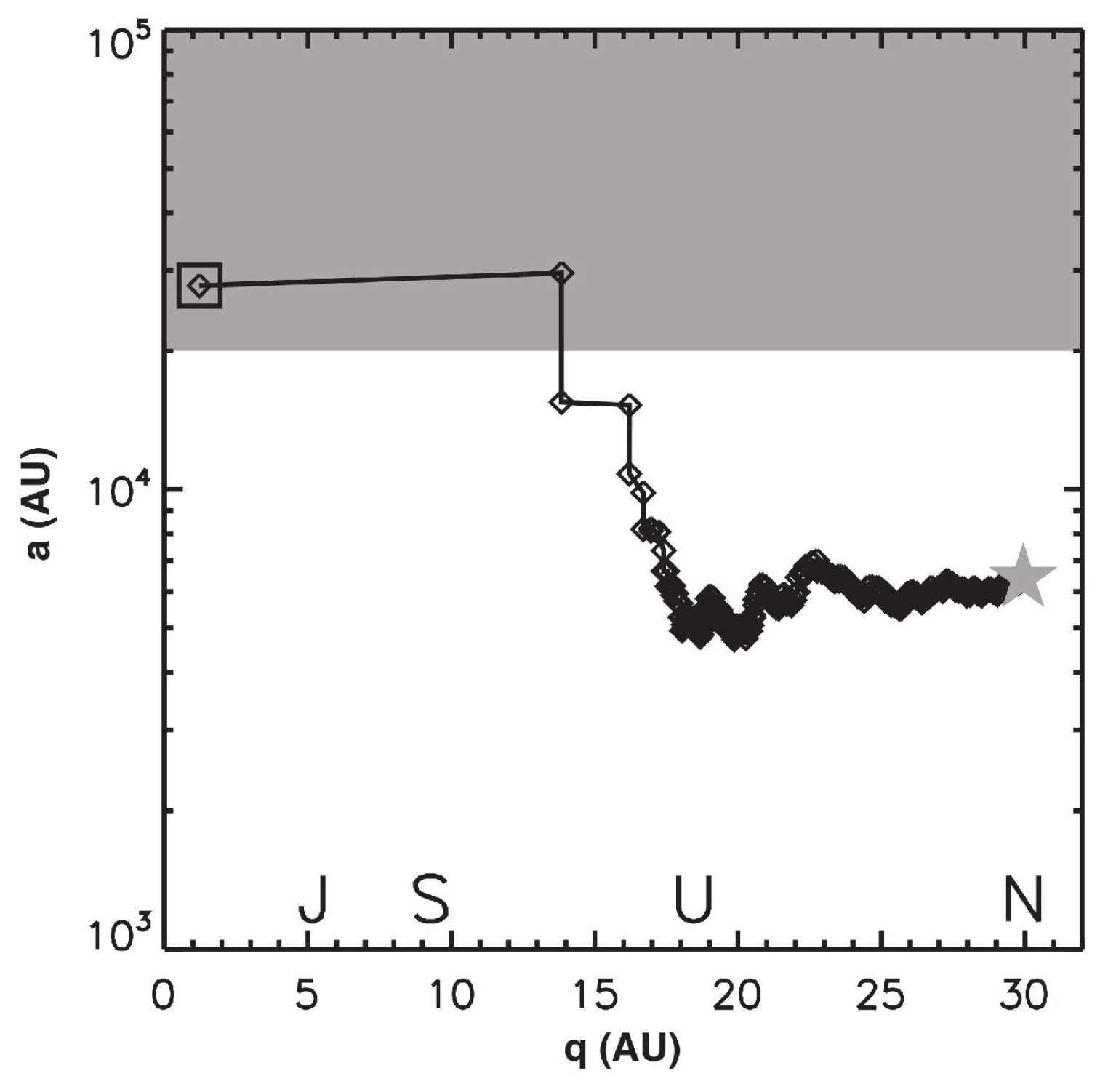

However, the story of comet supply is not finished here. It has been found that, while Jupiter mainly has a negative influence by ejecting comets, the other giant planets play important roles in supporting further routes of supply. This was first announced in a seminal paper by Kaib and Quinn [

6]. In

Figure 6 we reproduce

Figure 1 of that paper. The figure shows a sequence of osculating elements for a representative sample comet from their simulations. On the

x axis the perihelion distance is shown on a linear scale, and the

y axis features the semi-major axis on a log scale.

Marked by a grey star, the starting orbit has a semi-major axis of au and is perihelion tangent with respect to Neptune’s orbit. The comet thus belongs to the Oort Cloud inner core or Hills Cloud. The situation is typical for such comets, e.g.including a long and slow tidal decrease of the perihelion distance. This evolution is here seen to continue with a gradually decreasing perihelion distance and only slight changes of the semi-major axis due to perturbations by Neptune and Uranus. After the passage of the perihelion distance through au the planetary gravities take over as the main driver of the orbital evolution, and the semi-major axis quickly increases beyond au. This helps the tide to regain control so that the perihelion is brought closer to Saturn’s orbit. A final planetary perturbation then kicks the semi-major axis to au, after which the tide causes a jump of the perihelion into the observable region.

The ramification of this result is a demonstration that inner core comets can become observable by means of gravitational perturbations by the outer giant planets without assuming any specific circumstances. When they finally become observed, they are disguised as normal Oort Cloud comets from the outer regions. Moreover, Kaib and Quinn [

6] also showed – using their simulation results – that more than half the newcomers from the Oort Cloud should be such inner cloud comets.

The publication of this paper opened the gate for considering the inner core as an active source region for observed new comets with possible consequences for the origin of the cloud. Since then it has become normal to include the inner core as well as planetary perturbations into analyses of the Oort spike and its interpretation in terms of the structure of the Oort Cloud. One notable undertaking using massive simulations for this purpose has been reported,

e.g.by Fouchard et al. [

19,

30].

4. Oort Cloud Formation

4.1. Overview

A large majority of all the work that has been done on the formation of the Oort Cloud follows a common, basic idea, which will be described later. The main exception is an idea first explored by Zheng et al. [

31]. This assumes that the Sun was born in a stellar cluster and that this cluster housed a swarm of comets, which were captured by the Sun and other stars. Due to doubts over the capture efficiency, this idea was not pursued in further work until Levison et al. [

32] presented a more detailed but very similar view. Here the solar birth cluster was modelled as an aggregate of

stars in a very tight configuration – only the size of the present Oort Cloud. Each star was equipped with a scattered disc represented by

objects with pericentre distances close to

au and semi-major axes of a few thousand au. The stars were initially immersed into a residual gas cloud of several times the total stellar mass. This was assumed to remain for 3 Myr and then to quickly disappear.

During the early time the scattered disks were efficiently dispersed through close stellar encounters, thus creating an additional cluster component made up of cometary vagabonds. The disappearance of the gas signalled the dynamical breakup of the cluster. During the ensuing expansion and adiabatic cooling, captures of comets around stars with similar velocities were found frequently, hence providing the stars with bound comet clouds similar to the Oort Cloud. The authors concluded that our Oort Cloud may thus be a collection of icy planetesimals originally formed around many different stars belonging to the Sun’s birth cluster. This scenario has sometimes been called the "stealth model" of Oort Cloud formation.

Figure 7 instead shows what may be called the generally preferred roadmap of Oort Cloud formation. This illustrates the classical idea, which fits well into the modern picture of giant planet formation by

core accretion. In this picture, left-over planetesimals from the accretion zone of a giant planet, while undergoing close encounters with the planet, are gravitationally scattered into larger orbital energies (

) so that

a is increased. This process is really a random walk, but excursions into large values of

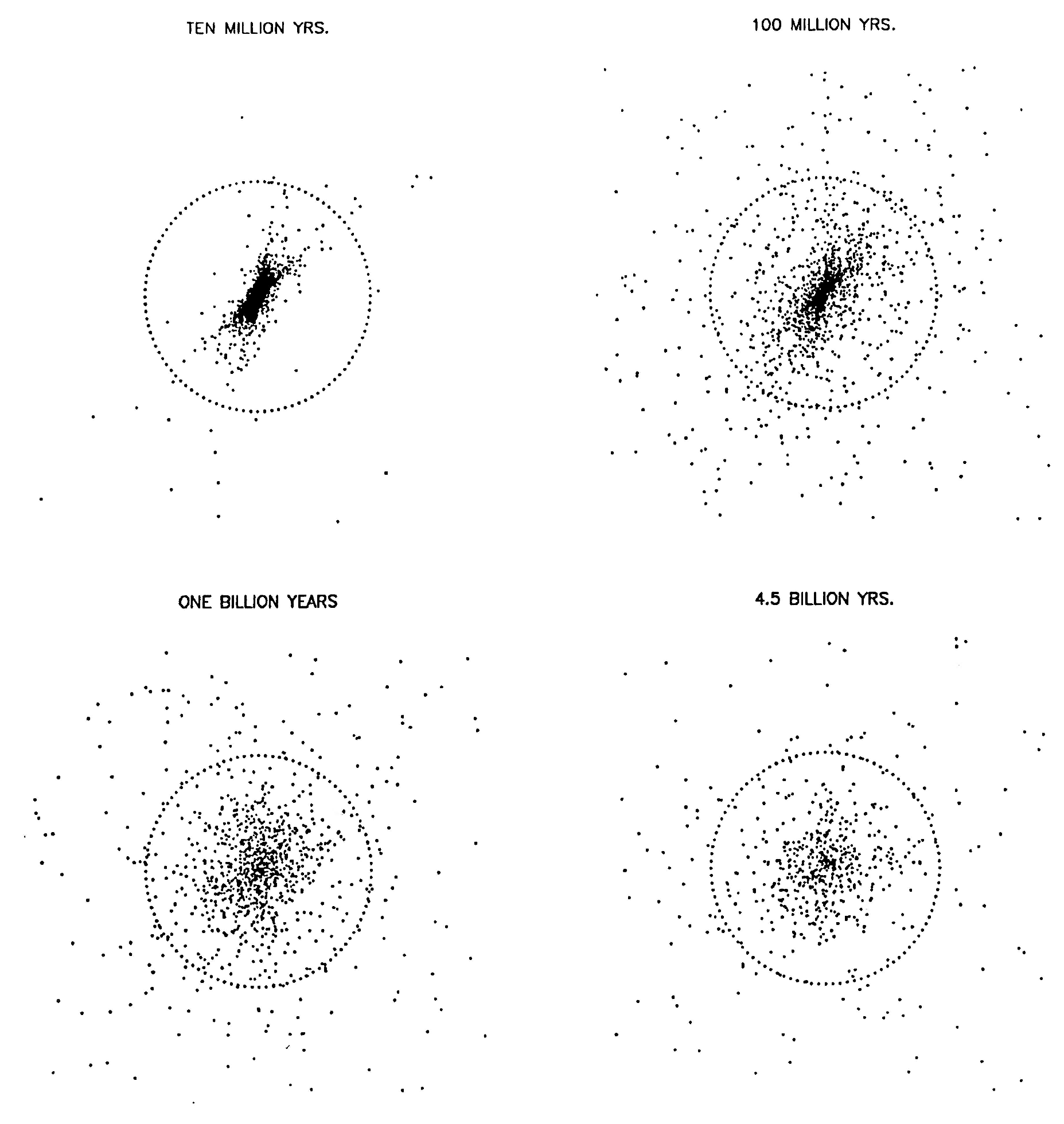

a or even ejection from the solar system occur frequently. A small fraction of the scattered planetesimals are led astray from the random walk by receiving additional, orbital angular momentum from an external agent, so that the perihelia are decoupled from the influence of the planets.

Historically, in the pictures envisaged by Öpik and Oort, this agent would have been stellar encounters. After the importance of the Galactic disc tide was realised in the 1980’s, this quickly became part of a new picture of Oort Cloud formation, primarily through the simulations of Duncan et al. [

34]. In these simulations the authors concentrated on objects formed in the Uranus-Neptune region. The results became a confirmation of Hills’ prediction of the Oort Cloud inner core, because it was found that the resulting Oort Cloud had five times as many comets in the inner core (

au) as in the classical, outer cloud (

au). An illustration of this finding by a time sequence of Oort Cloud portraits, projected onto the Galactic plane, is shown in

Figure 8. It should be noted that this type of formation model has been revisited in several more recent papers, most notably in a review by Dones et al. [

35].

Later on, a new concept was also introduced into models of Oort Cloud formation. This was the solar

birth cluster. In fact, observations show that stars are rarely born in isolation [

36], so it is

a priori very likely that the Sun spent at least its infancy as a member of a dense stellar aggregate just formed from a dusty gas clump in a Giant Molecular Cloud [

37]. Such an aggregate may or may not be long lived, but as long as it exists it provides an environment rich in nearby, slowly moving stars around members like the Sun.

Fernández and Brunini [

38] made the first simulations of Oort Cloud formation, which included a solar birth cluster. The explicit purpose was to allow for a more efficient perihelion extraction due to a high rate of strong impulses from encounters with other cluster members. This could help saving a large number of planetesimals scattered from Jupiter’s accretion zone for the Oort Cloud rather than being ejected by the planet. The simulation results indeed showed the Oort Cloud to be relatively richly populated, but at the same time its structure was strongly concentrated to the inner core. Such tight structures are vulnerable to criticism, since they do not provide the classical Oort Cloud evidenced by the Oort spike. We shall return to this issue in Sect. 5.

4.2. Birth Clusters

Three kinds of stellar clusters are known in the Galaxy. The globular clusters are among the oldest objects and thus are not of interest here. On the other hand, the Galactic disc houses many

open clusters, which are mostly younger than 1 Gyr [

39] and sometines are as young as

Myr [

40]. The youngest are still associated with the star forming regions where they were born. In those regions we often find extremely young stellar aggregates known as

embedded clusters.

There is a critical distinction between these two cluster types. An embedded cluster may or may not develop into an open cluster. In about 90% of the current cases, the embedded clusters will soon disappear by flying apart as unbound stellar associations. Their lifetimes can be estimated as less than 10 Myr. The reason is as follows. At birth the cluster is immersed in a cloud of residual gas and dust left after the star formation process. The mass of this cloud may dominate over the total mass of the stars, unless the star formation efficiency is unusually high. Within a few Myr, the massive OB stars ionise their surroundings and form expanding HII regions, and even more massive stars evolve into supernovae with associated shock fronts. These phenomena are referred to as

stellar feedback. It has the consequence that the residual gas is dispersed and leaves the cluster. When this happens, the cluster loses the gravitational potential that originally kept it together. It may become strongly supervirial and be doomed to rapid dispersal. For a description of these phenomena, see [

41].

However, in some relatively rare cases, the clusters avoid this fate. It may be that the loss of residual gas is slower or that the star formation efficiency is unusually high, but in any case the dynamical evolution leads to revirialisation and the system survives for hundreds of Myr, until two-body relaxation leads to the escape of high velocity stars and the gradual evaporation of member stars finally puts an end to the cluster’s lifetime. This is the case for the open clusters.

From this we conclude that there are two possibilities for the Sun’s birth cluster. A priori, the probability of a short lived embedded cluster is dominant, but there is also a significant chance for evolution into a long lived, open cluster. Clearly, these cases will have different consequences for the formation of the Oort Cloud. Unfortunately, we are not able to say which was the case for the Sun’s birth cluster, so it seems wise to consider both cases.

4.3. Current Status

During the last decade, the most influential paper on the formation of the Oort Cloud has probably been the one by Brasser and Morbidelli [

7]. The most important new feature of their analysis is that it is based on the picture of solar system evolution called the

Nice Model [see [

42]]. In this case, the main source of the Oort Cloud is the trans-planetary planetesimal disc, which plays a major role in steering the dynamics of the planetary system. The Oort Cloud production occurs after the chaotic period of instability, which sends Neptune out into the disc by a large increase of its orbital eccentricity. Neptune then takes the role of scattering agent and provider of objects for perihelion extraction by the external perturbers at the same time as it migrates outward to its present position.

The time scale of this process was found to be about 100 Myr. No attention is paid to a solar birth cluster, since this was likely far too short lived to have any influence at the times in question. Instead, stellar fly-bys typical of the Galactic disc were considered along with the vertical and radial components of the Galactic tide. The authors took great care to evaluate the efficiency of their formation scenario, and this was done by comparing the population size of the modelled Oort Cloud to that of the Scattered Disc – the current survivor of the primordial trans-planetary disc.

Since both populations stem from the same source, the Oort Cloud newcomers and the Scattered Disc objects should have the same size distribution. From their simulations, Brasser and Morbidelli [

7] inferred an OC/SD ratio of about 12. This appears to be in stark contrast to the usual estimates of

SD objects and

OC objects, leading to a ratio

. The OC estimate is based on absolute, total magnitudes of active comets, and the SD estimate relies on similar magnitudes of Jupiter Family comets under the reasonable assumption that these comets have been captured from the SD [

43]. However, we have seen in Sect. 2.1 that the translation from total magnitudes to nuclear sizes presents a difficult problem.

Brasser and Morbidelli [

7] used an estimate of the average brightness/size ratio for Jupiter Family comets compared to Oort Cloud comets based on Fernández and Sosa [

44], who argued that nongravitational parameters derived for one-apparition long period comets indicate a very large brightness/size ratio for such comets. Taking this into account, the OC/SD ratio was brought down to a likely range from about 10 to 100 for a count of objects larger than 2.3 km in diameter. There hence appears to be an underproduction of Oort Cloud comets in their formation model though agreement is not out of the question. We conclude that it is still unclear whether the Brasser and Morbidelli [

7] model is able to quantitatively predict the population size or mass of the Oort Cloud.

A different approach was recently taken by Wajer et al. [

33]. Here, the scenario is taylored to describe the extraction of sednoids and Oort Cloud comets in a newborn solar system long before the occurrence of the Nice Model instability. Only Jupiter and Saturn are included as scattering agents with a simplified model for their gas capture extending over 1.5 Myr. The only perihelion extraction agent taken into account is an embedded birth cluster by means of encounters with member stars and a smooth tidal potential due to the global gravity field of the cluster.

The primary goal of this investigation was to understand the formation of a sednoid population including the three observed objects then known rather than just (90377) Sedna, which had been dealt with by Brasser et al. [

45] in a similar study. However, the simulations also worked for the formation of the more distant Oort Cloud including the inner core as illustrated in

Figure 7. Four different cluster models were used and solar template stars were randomly selected to represent the Sun among the single stars with masses within 5% of the solar mass. The simulation results turned out to differ between the different cluster models, especially for the sednoids. The models with a highly concentrated, initial Plummer structure and a relatively long lived residual gas component proved very efficient in producing sednoids, while they did not stand out from the rest concerning the Oort Cloud population.

This is likely due to an effect described in an accompanying paper [

46] dealing with the extraction dynamics. The cluster models in question produce a very strong cluster tide, which lasts for a long time. This is a non-conservative, radial tide, which raises oscillations in the semi-major axes of the planetesimal orbits. When the scattering produces values beyond several thousand au, these oscillations are strong enough to unbind the objects from the Sun, and this places a serious limit on the Oort Cloud formation efficiency. Naturally, encounters with cluster stars may also have a similar effect.

As a consequence, the Oort Cloud formation efficiency found by Wajer et al. [

33] does not vary much between the cluster types and is limited to about 10% of the estimated, current Oort Cloud population size. This may still be of interest, since a significant fraction of the Oort Cloud newcomers is expected to have Earth-like D/H ratios being formed in or close to the formation zone of carbonaceous chondrites. However, for the bulk of the Oort Cloud we clearly need a different source.

Currently, there is an ongoing project on Oort Cloud formation (Rickman, Wajer, Wiśniowski, Kowalski, Nesvorný and Morbidelli, in prep.), which can only be superficially described here. This will be reminiscent of the mentioned Wajer et al. investigation but will consider models of a long lived birth cluster of the Pleiades type. In this case a time scale of at least 200 Myr will be simulated with inclusion of the Galactic tide and field stars as additional extraction agents.

5. Galactic Sculpting

Thus far, we have discussed Oort Cloud formation as a consequence of the same processes that gave rise to our solar system including the orbital architecture of the giant planets. But, from the point of view of the currently existing Oort Cloud, the formation of this primordial cloud provides only part of the solution. After this, there have been about 4.5 Gyr of what may be called Galactic sculpting, which must also be taken into account.

This sculpting occurs due to external perturbations. The stellar encounters already discussed as an agent for angular momentum transport have relatively small effects on the orbital energies. However, in rare cases – in particular, the fly-bys of massive stars – the impulse imparted to the Sun may be large enough to cause unbinding of outer cloud comets on a global scale [see [

19]. We mentioned this in the discussion of

Figure 5.

Let us now note another interesting point from the same Figure. The asterisks show a steady decline during the whole interval, caused by a gradual and important loss of outer cloud comets. This means that there must also be a steady replenishment of the outer cloud by migration from the inner parts. In fact, such a migration must occur for the same reason as the unbinding of outer cloud comets.

The evidence from

Figure 5 clearly suggests that the long term Galactic sculpting of the Oort Cloud occurs by a series of episodes of the mentioned kind, when

massive perturbers pass in the vicinity and cause a global shaking of the entire cloud that manifests itself through outward migration from the inner part and ejection from the outer part. The simulations behind

Figure 5 did not include any Galactic objects more massive than the high-mass stars, but the presence of Giant Molecular Clouds (GMCs) and the occurrence of encounters with these within a distance of

pc on Gyr time scales are known beyond doubt. In the presence of all such shake-up events, the Oort Cloud is likely eroded to a significant though not dramatic degree.

The proposed picture of Galactic sculpting shaping the history of the Oort Cloud still needs to be verified by further simulations (Rickman, Fouchard and Valsecchi, in prep.), but if it stands these tests, we may characterise this history by quoting the American rock-and-roll star Jerry Lee Lewis (1935-2022) by saying that there’s been a whole lot of shakin’ going on. And, most importantly, this may be the real reason why we can deduce the existence of the Oort Cloud through the Oort spike even today.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

The author is indebted to Paweł Wajer for technical assistance and Tomek Wiśniowski for preparing

Figure 3 and

Figure 7.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Öpik, E. Note on Stellar Perturbations of Nearly Parabolic Orbits. Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences 1932, 67, 169. [CrossRef]

- Oort, J.H. The structure of the cloud of comets surrounding the Solar System and a hypothesis concerning its origin. Bull. Astron. Inst. Netherlands 1950, 11, 91–110.

- Hills, J.G. Comet showers and the steady-state infall of comets from the Oort cloud. Astron. J. 1981, 86, 1730–1740. [CrossRef]

- Heisler, J.; Tremaine, S. The influence of the Galactic tidal field on the Oort comet cloud. Icarus 1986, 65, 13–26. [CrossRef]

- Rickman, H.; Fouchard, M.; Froeschlé, C.; Valsecchi, G.B. Injection of Oort Cloud comets: the fundamental role of stellar perturbations. Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy 2008, 102, 111–132, [arXiv:astro-ph/0804.2560]. [CrossRef]

- Kaib, N.A.; Quinn, T. Reassessing the Source of Long-Period Comets. Science 2009, 325, 1234, [arXiv:astro-ph.EP/0912.1645]. [CrossRef]

- Brasser, R.; Morbidelli, A. Oort cloud and Scattered Disc formation during a late dynamical instability in the Solar System. Icarus 2013, 225, 40–49, [arXiv:astro-ph.EP/1303.3098]. [CrossRef]

- Rickman, H. Cometary Dynamics. In Lecture Notes in Physics, Berlin Springer Verlag; Souchay, J.; Dvorak, R., Eds.; 2010; Vol. 790, pp. 341–399. [CrossRef]

- Rickman, H. Stellar Perturbations of Orbits of Long-period Comets and their Significance for Cometary Capture. Bulletin of the Astronomical Institutes of Czechoslovakia 1976, 27, 92.

- Bailey, M.E.; Clube, S.V.M.; Napier, W.M. The origin of comets. Vistas in Astronomy 1986, 29, 53–112. [CrossRef]

- Rickman, H. Interrelations Between Physics and Dynamics for Minor Bodies in the Solar System. In Proceedings of the Interrelations Between Physics and Dynamics for Minor Bodies in the Solar System; Benest, D.; Froeschle, C., Eds., Gif-sur-Yvette, 1992; pp. 197–.

- Marsden, B.G. Catalogue of Cometary Orbits, 6th ed.; IAU Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams: Cambridge, MA, 1989.

- Oort, J.H.; Schmidt, M. Differences between new and old comets. Bull. Astron. Inst. Netherlands 1951, 11, 259.

- Weissman, P.R. Physical loss of long-period comets. Astron. Astrophys. 1980, 85, 191–196.

- Levison, H.F.; Morbidelli, A.; Dones, L.; Jedicke, R.; Wiegert, P.A.; Bottke, W.F. The Mass Disruption of Oort Cloud Comets. Science 2002, 296, 2212–2215. [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, J.A.; Ip, W.H. Time-dependent injection of Oort cloud comets into Earth-crossing orbits. Icarus 1987, 71, 46–56. [CrossRef]

- Heisler, J.; Tremaine, S.; Alcock, C. The frequency and intensity of comet showers from the Oort cloud. Icarus 1987, 70, 269–288. [CrossRef]

- Heisler, J. Monte Carlo simulations of the Oort comet cloud. Icarus 1990, 88, 104–121. [CrossRef]

- Fouchard, M.; Rickman, H.; Froeschlé, C.; Valsecchi, G.B. Planetary perturbations for Oort cloud comets: III. Evolution of the cloud and production of centaurs and Halley type comets. Icarus 2014, 231, 99–109. [CrossRef]

- Stokes, G.H.; Evans, J.B.; Viggh, H.E.M.; Shelly, F.C.; Pearce, E.C. Lincoln Near-Earth Asteroid Program (LINEAR). Icarus 2000, 148, 21–28. [CrossRef]

- Francis, P.J. The Demographics of Long-Period Comets. Astrophys. J. 2005, 635, 1348–1361, [arXiv:astro-ph/astro-ph/0509074]. [CrossRef]

- Everhart, E. Intrinsic distributions of cometary perihelia and magnitudes. Astron. J. 1967, 72, 1002. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, D.W. The magnitude distribution, perihelion distribution and flux of long-period comets. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2001, 326, 515–523. [CrossRef]

- Perryman, M.A.C.; Brown, A.G.A.; Lebreton, Y.; Gomez, A.; Turon, C.; Cayrel de Strobel, G.; Mermilliod, J.C.; Robichon, N.; Kovalevsky, J.; Crifo, F. The Hyades: distance, structure, dynamics, and age. Astron. Astrophys. 1998, 331, 81–120, [arXiv:astro-ph/astro-ph/9707253]. [CrossRef]

- Lindegren, L.; Klioner, S.A.; Hernández, J.; Bombrun, A.; Ramos-Lerate, M.; Steidelmüller, H.; Bastian, U.; Biermann, M.; de Torres, A.; Gerlach, E.; et al. Gaia Early Data Release 3. The astrometric solution. Astron. Astrophys. 2021, 649, A2, [arXiv:astro-ph.IM/2012.03380]. [CrossRef]

- García-Sánchez, J.; Weissman, P.R.; Preston, R.A.; Jones, D.L.; Lestrade, J.F.; Latham, D.W.; Stefanik, R.P.; Paredes, J.M. Stellar encounters with the solar system. Astron. Astrophys. 2001, 379, 634–659. [CrossRef]

- Chebotarev, G.A. On the Dynamical Limites of the Solar System. Astronomicheskii Zhurnal 1964, 41, 983.

- Byl, J. Galactic Perturbations on Nearly Parabolic Cometary Orbits. Moon and Planets 1983, 29, 121–137. [CrossRef]

- Delsemme, A.H. Galactic Tides Affect the Oort Cloud - an Observational Confirmation. Astron. Astrophys. 1987, 187, 913.

- Fouchard, M.; Rickman, H.; Froeschlé, C.; Valsecchi, G.B. Planetary perturbations for Oort Cloud comets. I. Distributions and dynamics. Icarus 2013, 222, 20–31. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.Q.; Valtonen, M.J.; Valtaoja, L. Capture of Comets during the Evolution of a Star Cluster and the Origin of the Oort Cloud. Celestial Mechanics and Dynamical Astronomy 1990, 49, 265–272. [CrossRef]

- Levison, H.F.; Duncan, M.J.; Brasser, R.; Kaufmann, D.E. Capture of the Sun’s Oort Cloud from Stars in Its Birth Cluster. Science 2010, 329, 187–190. [CrossRef]

- Wajer, P.; Rickman, H.; Kowalski, B.; Wiśniowski, T. Oort Cloud and sednoid formation in an embedded cluster, I: Populations and size distributions. Icarus 2024, 415, 116065. [CrossRef]

- Duncan, M.; Quinn, T.; Tremaine, S. The Formation and Extent of the Solar System Comet Cloud. Astron. J. 1987, 94, 1330. [CrossRef]

- Dones, L.; Weissman, P.R.; Levison, H.F.; Duncan, M.J.; Binzel, R.P. Oort Cloud Formation and Dynamics. In Comets II; Festou, M.C.; Keller, H.U.; Weaver, H.A., Eds.; University of Arizona Press, 2004; pp. 153–174. In Comets II, edited by M. C. Festou, H. U. Keller, and H. A. Weaver.

- Lada, C.J.; Lada, E.A. Embedded Clusters in Molecular Clouds. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2003, 41, 57–115, [arXiv:astro-ph/astro-ph/0301540]. [CrossRef]

- Kruijssen, J.M.D. On the fraction of star formation occurring in bound stellar clusters. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2012, 426, 3008–3040, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/1208.2963]. [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.A.; Brunini, A. The Buildup of a Tightly Bound Comet Cloud around an Early Sun Immersed in a Dense Galactic Environment: Numerical Experiments. Icarus 2000, 145, 580–590. [CrossRef]

- Wielen, R. The Age Distribution and Total Lifetimes of Galactic Clusters. Astron. Astrophys. 1971, 13, 309–322.

- Currie, T.; Plavchan, P.; Kenyon, S.J. A Spitzer Study of Debris Disks in the Young Nearby Cluster NGC 2232: Icy Planets Are Common around ~1.5-3 M⊙ Stars. Astrophys. J. 2008, 688, 597–615, [arXiv:astro-ph/0807.2056]. [CrossRef]

- Pang, X.; Li, Y.; Tang, S.Y.; Pasquato, M.; Kouwenhoven, M.B.N. Different Fates of Young Star Clusters after Gas Expulsion. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2020, 900, L4, [arXiv:astro-ph.GA/2008.02803]. [CrossRef]

- Nesvorný, D. Dynamical Evolution of the Early Solar System. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 2018, 56, 137–174, [arXiv:astro-ph.EP/1807.06647]. [CrossRef]

- Duncan, M.J.; Levison, H.F. A scattered comet disk and the origin of Jupiter family comets. Science 1997, 276, 1670–1672. [CrossRef]

- Fernández, J.A.; Sosa, A. Magnitude and size distribution of long-period comets in Earth-crossing or approaching orbits. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2012, 423, 1674–1690, [arXiv:astro-ph.EP/1204.2285]. [CrossRef]

- Brasser, R.; Duncan, M.J.; Levison, H.F.; Schwamb, M.E.; Brown, M.E. Reassessing the formation of the inner Oort cloud in an embedded star cluster. Icarus 2012, 217, 1–19, [arXiv:astro-ph.EP/1110.5114]. [CrossRef]

- Wajer, P.; Rickman, H.; Kowalski, B.; Wiśniowski, T. Oort Cloud and sednoid formation in an embedded cluster. II. Dynamics and orbital evolutions. Icarus 2024, 410, 115915. [CrossRef]

| 1 |

Lincoln Near-Earth Asteroid Research |

| 2 |

Legacy Survey of Space and Time |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).