Submitted:

15 January 2026

Posted:

19 January 2026

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Desing

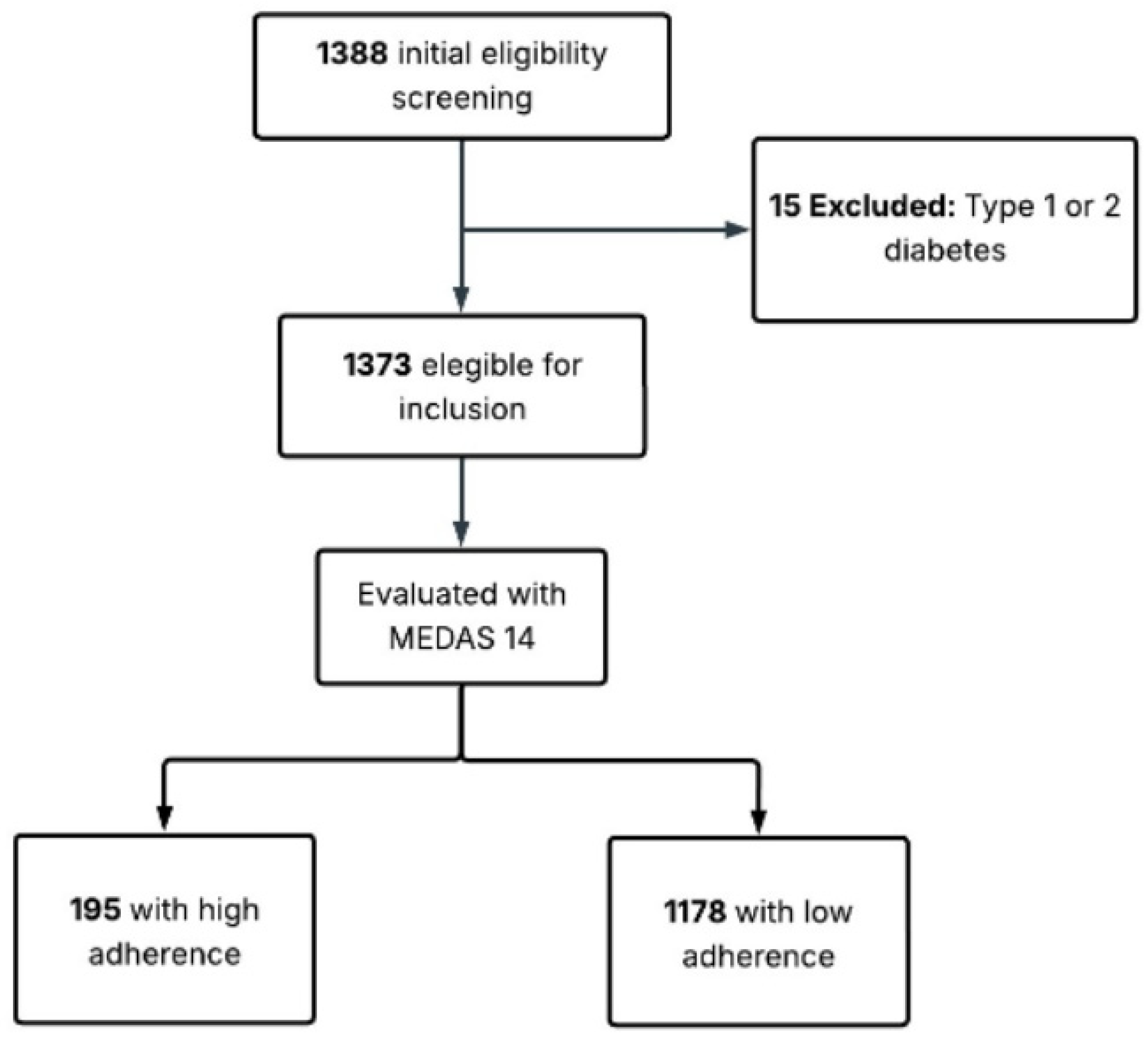

2.2. Population and Sample

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Anthropometric and Body Composition

2.5. Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet

2.6. Risk of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

2.7. Ethical Approval

2.8. Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Marques, ES; Formato, E; Liang, W; Leonard, E; Timme-Laragy, AR. Relationships between type 2 diabetes, cell dysfunction, and redox signaling: A meta-analysis of single-cell gene expression of human pancreatic α- and β-cells. J Diabetes 2022, 14[1], 34–51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fuster-Parra, P; Yañez, AM; López-González, A; Aguiló, A; Bennasar-Veny, M. Identifying risk factors of developing type 2 diabetes from an adult population with initial prediabetes using a Bayesian network. Front Public Health 2022, 10, 1035025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeedi, P; Petersohn, I; Salpea, P; Malanda, B; Karuranga, S; Unwin, N; et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the International Diabetes Federation Diabetes Atlas, 9th edition. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2019, 157, 107843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milenkovic, T; Bozhinovska, N; Macut, D; Bjekic-Macut, J; Rahelic, D; Velija Asimi, Z; et al. Mediterranean Diet and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Perpetual Inspiration for the Scientific World. A Review. Nutrients 2021, 13[4], 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarsangi, P; Salehi-Abargouei, A; Ebrahimpour-Koujan, S; Esmaillzadeh, A. Association between Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: An Updated Systematic Review and Dose-Response Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Adv Nutr 2022, 13[5], 1787–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrea, L; Verde, L; Simancas-Racines, D; Zambrano, AK; Frias-Toral, E; Colao, A; et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet as a possible additional tool to be used for screening the metabolically unhealthy obesity [MUO] phenotype. J Transl Med. 2023, 21[1], 675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotzakioulafi, E; Bakaloudi, DR; Chrysoula, L; Theodoridis, X; Antza, C; Tirodimos, I; et al. High Versus Low Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet for Prevention of Diabetes Mellitus Type 2: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Metabolites 2023, 13[7], 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sleiman, D; Al-Badri, MR; Azar, ST. Effect of mediterranean diet in diabetes control and cardiovascular risk modification: a systematic review. Front Public Health 2015, 3, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosatti, JAG; Alves, MT; Gomes, KB. The Role of the Mediterranean Dietary Pattern on Metabolic Control of Patients with Diabetes Mellitus: A Narrative Review. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2021, 1307, 115–28. [Google Scholar]

- Godos, J; Zappalà, G; Mistretta, A; Galvano, F; Grosso, G. Mediterranean diet, diet quality, and adequacy to Italian dietary recommendations in southern Italian adults. Mediterranean Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism 2024, 17[3], 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Pozo, V; Guevara, P; Paz Cruz, E; Tamayo Trujillo, R; Cadena-Ullauri, S; Frias-Toral, E; et al. The role of the Mediterranean diet in prediabetes management and prevention: a review of molecular mechanisms and clinical outcomes. Food and Agricultural Immunology 2024, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiani, AK; Medori, MC; Bonetti, G; Aquilanti, B; Velluti, V; Matera, G; et al. Modern vision of the Mediterranean diet. J Prev Med Hyg. 2022, 63 2 Suppl 3, E36-43. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z; Khandpur, N; Desjardins, C; Wang, L; Monteiro, CA; Rossato, SL; et al. Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: Three Large Prospective U.S. Cohort Studies. Diabetes Care 2023, 46[7], 1335–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S; Sullivan, VK; Fang, M; Appel, LJ; Selvin, E; Rebholz, CM. Ultra-processed food consumption and risk of diabetes: results from a population-based prospective cohort. Diabetologia 2024, 67[10], 2225–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Ramírez, S; Martinez-Tapia, B; González-Castell, D; Cuevas-Nasu, L; Shamah-Levy, T. Westernized and Diverse Dietary Patterns Are Associated With Overweight-Obesity and Abdominal Obesity in Mexican Adult Men. Front Nutr. 2022, 9, 891609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldeón, ME; Felix, C; Fornasini, M; Zertuche, F; Largo, C; Paucar, MJ; et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and diabetes mellitus type-2 and their association with intake of dairy and legume in Andean communities of Ecuador. PLoS One 2021, 16[7], e0254812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, M; Jebb, SA; Aveyard, P; Ambrosini, GL; Perez-Cornago, A; Papier, K; et al. Associations Between Dietary Patterns and Incident Type 2 Diabetes: Prospective Cohort Study of 120,343 UK Biobank Participants. Diabetes Care 2022, 45[6], 1315–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa-Avilés, A; Verstraeten, R; Lachat, C; Andrade, S; Van Camp, J; Donoso, S; et al. Dietary intake practices associated with cardiovascular risk in urban and rural Ecuadorian adolescents: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suresh, A; Shobna; Salaria, M; Morya, S; Khalid, W; Afzal, FA; et al. Dietary fiber: an unmatched food component for sustainable health. Food and Agricultural Immunology 2024, 35[1], 2384420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bondonno, NP; Davey, RJ; Murray, K; Radavelli-Bagatini, S; Bondonno, CP; Blekkenhorst, LC; et al. Associations Between Fruit Intake and Risk of Diabetes in the AusDiab Cohort. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021, 106[10], e4097-108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H; Christman, LM; Li, R; Gu, L. Synergic interactions between polyphenols and gut microbiota in mitigating inflammatory bowel diseases. Food Funct 2020, 11[6], 4878–91. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-González, MA; García-Arellano, A; Toledo, E; Salas-Salvadó, J; Buil-Cosiales, P; Corella, D; et al. A 14-item Mediterranean diet assessment tool and obesity indexes among high-risk subjects: the PREDIMED trial. PLoS One 2012, 7[8], e43134. [Google Scholar]

- Hurtado-Barroso, S; Martínez-Huélamo, M; Rinaldi de Alvarenga, JF; Quifer-Rada, P; Vallverdú-Queralt, A; Pérez-Fernández, S; et al. Acute Effect of a Single Dose of Tomato Sofrito on Plasmatic Inflammatory Biomarkers in Healthy Men. Nutrients 2019, 11[4], 851. [Google Scholar]

- James-Martin, G; Brooker, PG; Hendrie, GA; Stonehouse, W. Avocado Consumption and Cardiometabolic Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2024, 124[2], 233–248.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirani, K; Sundheim, B; Blaschke, M; Lemos, JRN; Mittal, R. A global call to action: strengthening strategies to combat dysglycemia and improve public health outcomes. Front Public Health 2025, 13, 1597128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Probst, Y; Guan, V; Neale, E. Avocado intake and cardiometabolic risk factors in a representative survey of Australians: a secondary analysis of the 2011-2012 national nutrition and physical activity survey. Nutr J 2024, 23[1], 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guasch-Ferré, M; Willett, WC. The Mediterranean diet and health: a comprehensive overview. J Intern Med. 2021, 290[3], 549–66. [Google Scholar]

- Schwingshackl, L; Morze, J; Hoffmann, G. Mediterranean diet and health status: Active ingredients and pharmacological mechanisms. Br J Pharmacol 2020, 177[6], 1241–57. [Google Scholar]

- Dernini, S; Berry, EM. Mediterranean Diet: From a Healthy Diet to a Sustainable Dietary Pattern. Front Nutr 2015, 2, 15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Matos, RA; Adams, M; Sabaté, J. Review: The Consumption of Ultra-Processed Foods and Non-communicable Diseases in Latin America. Front Nutr. 2021, 8, 622714. [Google Scholar]

- Anza-Ramirez, C; Lazo, M; Zafra-Tanaka, JH; Avila-Palencia, I; Bilal, U; Hernández-Vásquez, A; et al. The urban built environment and adult BMI, obesity, and diabetes in Latin American cities. Nat Commun 2022, 13[1], 7977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, R; Bautista-Valarezo, E; Matos, A; Calderón, P; Fascì-Spurio, F; Castano-Jimenez, J; et al. Obesity and nutritional strategies: advancing prevention and management through evidence-based approaches. Food and Agricultural Immunology 2025, 36[1], 2491597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manual de vigilancia STEPS de la OMS: el método STEPwise de la OMS para la vigilancia de los factores de riesgo de las enfermedades crónicas [Internet]. [citado 8 de enero de 2026]. Available online: https://iris.who.int/items/0d955541-1144-4934-9867-616946337c57.

- Craig, CL; Marshall, AL; Sjöström, M; Bauman, AE; Booth, ML; Ainsworth, BE; et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003, 35[8], 1381–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernabe-Ortiz, A; Perel, P; Miranda, JJ; Smeeth, L. Diagnostic accuracy of the Finnish Diabetes Risk Score [FINDRISC] for undiagnosed T2DM in Peruvian population. Prim Care Diabetes 2018, 12[6], 517–25. [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo-Larco, RM; Aparcana-Granda, DJ; Mejia, JR; Bernabé-Ortiz, A. FINDRISC in Latin America: a systematic review of diagnosis and prognosis models. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2020, 8[1], e001169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Silvestre, MP; Jiang, Y; Volkova, K; Chisholm, H; Lee, W; Poppitt, SD. Evaluating FINDRISC as a screening tool for type 2 diabetes among overweight adults in the PREVIEW:NZ cohort. Prim Care Diabetes 2017, 11[6], 561–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guías de práctica Clínica 2017 – Ministerio de Salud Pública [Internet]. [citado 8 de enero de 2026]. Available online: https://www.salud.gob.ec/guias-de-practica-clinica-2017/.

- Lee, JY; Kim, S; Lee, Y; Kwon, YJ; Lee, JW. Higher Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet Is Associated with a Lower Risk of Steatotic, Alcohol-Related, and Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease: A Retrospective Analysis. Nutrients 2024, 16[20], 3551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caizaguano, MAC; Carpio, V; del, PC. Adherence to the mediterranean diet in an urban population of the ecuadorian sierra. Salud, Ciencia y Tecnología 2022, 2, 229–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinaccia, S; Serra-Majem, L; Ruano, C; Quintero Marzola, M; Ortega, A; Momo Cabrera, P; et al. Artículo Original Adherencia a la dieta mediterránea en población universitaria colombiana Mediterranean diet adherence in Colombian university population. Nutricion Clinica y Dietetica Hospitalaria 2019, 39, 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, G; Fisberg, RM; Nogueira Previdelli, Á; Hermes Sales, C; Kovalskys, I; Fisberg, M; et al. Diet Quality and Diet Diversity in Eight Latin American Countries: Results from the Latin American Study of Nutrition and Health [ELANS]. Nutrients 2019, 11[7], 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denova-Gutiérrez, E; Tucker, KL; Flores, M; Barquera, S; Salmerón, J. Dietary Patterns Are Associated with Predicted Cardiovascular Disease Risk in an Urban Mexican Adult Population. J Nutr. 2016, 146[1], 90–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y; Cortés-Ortiz, MV; Baylin, A; Leung, CW; Rosero-Bixby, L; Ruiz-Narváez, EA. Traditional rural dietary pattern and all-cause mortality in a prospective cohort study of elderly Costa Ricans: the Costa Rican Longevity and Healthy Aging Study [CRELES]. Am J Clin Nutr 2024, 120[3], 656–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valerino-Perea, S; Armstrong, MEG; Papadaki, A. Adherence to a traditional Mexican diet and non-communicable disease-related outcomes: secondary data analysis of the cross-sectional Mexican National Health and Nutrition Survey. Br J Nutr 2023, 129[7], 1266–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraft, TS; Stieglitz, J; Trumble, BC; Martin, M; Kaplan, H; Gurven, M. Nutrition transition in 2 lowland Bolivian subsistence populations. Am J Clin Nutr 2018, 108[6], 1183–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gualan, M; Ster, IC; Veloz, T; Granadillo, E; Llangari-Arizo, LM; Rodriguez, A; et al. Cardiometabolic diseases and associated risk factors in transitional rural communities in tropical coastal Ecuador. PLoS One 2024, 19[7], e0307403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Garzón, S; Vasconez, J; Delgado, JP; Barrera-Guarderas, F; Chilet-Rosell, E; Puig-García, M; et al. The burden of non-communicable disease risk factors in a low-income population: Findings from a cross-sectional study highlighting the prevalence of obesity, hypertension, and metabolic disorders in the south of Quito, Ecuador. PLoS One 2025, 20[9], e0332159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valder, S; Schick, F; Pietsch, N; Wagner, T; Urban, H; Lindemann, P; et al. Effects of two weeks of daily consumption of [poly]phenol-rich red berry fruit juice, with and without high-intensity physical training, on health outcomes in individuals with pre-diabetes mellitus. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2025, 35[10], 104121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lecerf, JM; Moreno Aznar, L; Rjimati, L; Atkinson, FS; Richonnet, C. Glycemic and Insulinemic Index Values of Apple Puree. Food Sci Nutr 2025, 13[9], e70844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawahara, T; Nawa, N; Oze, I; Ikezaki, H; Hara, M; Kubo, Y; et al. Inverse association between fruit juice consumption and type 2 diabetes among individuals with high genetic risk on type 2 diabetes: the Japan Multi-Institutional Collaborative Cohort [J-MICC] study. Br J Nutr. 2025, 134[2], 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, JA; Nieto, JA; Suarez-Diéguez, T; Silva, M. Influence of culinary skills on ultraprocessed food consumption and Mediterranean diet adherence: An integrative review. Nutrition 2024, 121, 112354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, CA; Andrade, GC; de Oliveira, MFB; Rauber, F; de Castro, IRR; Couto, MT; et al. «Healthy», «usual» and «convenience» cooking practices patterns: How do they influence children’s food consumption? Appetite 2021, 158, 105018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, P de M; Couto, MT; Wells, J; Cardoso, MA; Devakumar, D; Scagliusi, FB. Mothers’ food choices and consumption of ultra-processed foods in the Brazilian Amazon: A grounded theory study. Appetite 2020, 148, 104602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braverman-Bronstein, A; Camacho-García-Formentí, D; Zepeda-Tello, R; Cudhea, F; Singh, GM; Mozaffarian, D; et al. Mortality attributable to sugar sweetened beverages consumption in Mexico: an update. Int J Obes [Lond] 2020, 44[6], 1341–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardach, AE; Espínola, N; Cairoli, FR; Perelli, L; Balan, D; Palacios, A; et al. The burden of disease and economic impact of sugar-sweetened beverages’ consumption in Argentina: A modeling study. PLoS One 2023, 18[2], e0279978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulawik, A; Cielecka-Piontek, J; Zalewski, P. The Importance of Antioxidant Activity for the Health-Promoting Effect of Lycopene. Nutrients 2023, 15[17], 3821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N; Wu, X; Zhuang, W; Xia, L; Chen, Y; Wu, C; et al. Tomato and lycopene and multiple health outcomes: Umbrella review. Food Chem. 2021, 343, 128396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storniolo, CE; Sacanella, I; Lamuela-Raventos, RM; Moreno, JJ. Bioactive Compounds of Mediterranean Cooked Tomato Sauce [Sofrito] Modulate Intestinal Epithelial Cancer Cell Growth Through Oxidative Stress/Arachidonic Acid Cascade Regulation. ACS Omega 2020, 5[28], 17071–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connolly, LJ; Nordsborg, NB; Nyberg, M; Weihe, P; Krustrup, P; Mohr, M. Low-volume high-intensity swim training is superior to high-volume low-intensity training in relation to insulin sensitivity and glucose control in inactive middle-aged women. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2016, 116[10], 1889–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dovinova, I; Kvandová, M; Balis, P; Gresova, L; Majzunova, M; Horakova, L; et al. The role of Nrf2 and PPARgamma in the improvement of oxidative stress in hypertension and cardiovascular diseases. Physiol Res. 2020, 69 Suppl 4, S541–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jideani, AIO; Silungwe, H; Takalani, T; Omolola, AO; Udeh, HO; Anyasi, TA. Antioxidant-rich natural fruit and vegetable products and human health. International Journal of Food Properties [Internet]. 1 de enero de 2021 [citado 9 de marzo de 2025]. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10942912.2020.1866597.

- Rinaldi de Alvarenga, JF; Quifer-Rada, P; Westrin, V; Hurtado-Barroso, S; Torrado-Prat, X; Lamuela-Raventós, RM. Mediterranean sofrito home-cooking technique enhances polyphenol content in tomato sauce. J Sci Food Agric. 2019, 99[14], 6535–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandoval, V; Rodríguez-Rodríguez, R; Martínez-Garza, Ú; Rosell-Cardona, C; Lamuela-Raventós, RM; Marrero, PF; et al. Mediterranean Tomato-Based Sofrito Sauce Improves Fibroblast Growth Factor 21 [FGF21] Signaling in White Adipose Tissue of Obese ZUCKER Rats. Mol Nutr Food Res 2018, 62[4]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandoval, LA; Carpio, CE; Sanchez-Plata, M. The effect of «Traffic-Light» nutritional labelling in carbonated soft drink purchases in Ecuador. PLoS One 2019, 14[10], e0222866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Ritter, R; Sep, SJS; van Greevenbroek, MMJ; Kusters, YHAM; Vos, RC; Bots, ML; et al. Sex differences in body composition in people with prediabetes and type 2 diabetes as compared with people with normal glucose metabolism: the Maastricht Study. Diabetologia 2023, 66[5], 861–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciardullo, S; Zerbini, F; Cannistraci, R; Muraca, E; Perra, S; Oltolini, A; et al. Differential Association of Sex Hormones with Metabolic Parameters and Body Composition in Men and Women from the United States. J Clin Med. 2023, 12[14], 4783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z; Hu, Y; He, H; Chen, X; Ou, Q; Liu, Y; et al. Associations of muscle mass, strength, and quality with diabetes and the mediating role of inflammation in two National surveys from China and the United states. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2024, 214, 111783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suárez, R; Andrade, C; Bautista-Valarezo, E; Sarmiento-Andrade, Y; Matos, A; Jimenez, O; et al. Low muscle mass index is associated with type 2 diabetes risk in a Latin-American population: a cross-sectional study. Front Nutr. 2024, 11, 1448834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayedi, A; Soltani, S; Motlagh, SZT; Emadi, A; Shahinfar, H; Moosavi, H; et al. Anthropometric and adiposity indicators and risk of type 2 diabetes: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ 2022, 376, e067516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López-Gil, JF; García-Hermoso, A; Martínez-González, MÁ; Rodríguez-Artalejo, F. Mediterranean Diet and Cardiometabolic Biomarkers in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2024, 7[7], e2421976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Onofre Bernat, N; Quiles, I; Izquierdo, J; Trescastro-López, EM. Health Determinants Associated with the Mediterranean Diet: A Cross-Sectional Study. Nutrients 2022, 14[19], 4110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conde-Pipó, J; Martinez-Amat, A; Mora-Fernández, A; Mariscal-Arcas, M. Impact of Mediterranean Diet Pattern Adherence on the Physical Component of Health-Related Quality of Life in Middle-Aged and Older Active Adults. Nutrients 2024, 16[22], 3877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, L; Liu, Y; Huang, C; Huang, Y; Lin, R; Wei, K; et al. Association of accelerated phenotypic aging, genetic risk, and lifestyle with progression of type 2 diabetes: a prospective study using multi-state model. BMC Med 2025, 23[1], 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosi, A; Scazzina, F; Giampieri, F; Abdelkarim, O; Aly, M; Pons, J; et al. Adherence to the Mediterranean diet in 5 Mediterranean countries: A descriptive analysis of the DELICIOUS project. 1 de noviembre de 2024 [citado 8 de enero de 2026]. Available online: https://www.growkudos.com/publications/10.1177%252F1973798x241296440.

- Nucci, D; Stacchini, L; Villa, M; Passeri, C; Romano, N; Ferranti, R; et al. The role of Mediterranean diet in reducing household food waste: the UniFoodWaste study among italian students. Int J Food Sci Nutr 2025, 76[4], 443–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alakaam, A; Lett, M; Puckett, H; Kite, K. Associations among Eating Habits, Health Conditions, and Education Level in North Dakota Adults. Health Behavior and Policy Review 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verde, L; Barrea, L; Bowman-Busato, J; Yumuk, VD; Colao, A; Muscogiuri, G. Obesogenic environments as major determinants of a disease: It is time to re-shape our cities. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2024, 40[1], e3748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, L; Hopstock, LA; Skeie, G; Grimsgaard, S; Lundblad, MW. The Educational Gradient in Intake of Energy and Macronutrients in the General Adult and Elderly Population: The Tromsø Study 2015-2016. Nutrients 2021, 13[2], 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melby, CL; Orozco, F; Ochoa, D; Muquinche, M; Padro, M; Munoz, FN. Nutrition and physical activity transitions in the Ecuadorian Andes: Differences among urban and rural-dwelling women. Am J Hum Biol. 2017, 29[4]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melby, CL; Orozco, F; Averett, J; Muñoz, F; Romero, MJ; Barahona, A; et al. Agricultural Food Production Diversity and Dietary Diversity among Female Small Holder Farmers in a Region of the Ecuadorian Andes Experiencing Nutrition Transition. Nutrients [Internet]. 14 de agosto de 2020 [citado 8 de enero de 2026];12[8]. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6643/12/8/2454.

- Chi, Y; Wang, X; Jia, J; Huang, T. Smoking Status and Type 2 Diabetes, and Cardiovascular Disease: A Comprehensive Analysis of Shared Genetic Etiology and Causal Relationship. Front Endocrinol [Lausanne] 2022, 13, 809445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, H; Fitó, M; Estruch, R; Martínez-González, MA; Corella, D; Salas-Salvadó, J; et al. A short screener is valid for assessing Mediterranean diet adherence among older Spanish men and women. J Nutr. 2011, 141[6], 1140–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalskys, I; Rigotti, A; Koletzko, B; Fisberg, M; Gómez, G; Herrera-Cuenca, M; et al. Latin American consumption of major food groups: Results from the ELANS study. PLoS One 2019, 14[12], e0225101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Adherence to MedDiet | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High 195 (14.2%) |

Low 1178 (85.8%)] |

P value | |||

| Age, years | Mean (SD) | 43.56 (10.2) | 40.27 (10.11) | 0.000* | |

| Gender (n,%) | Male | 59 (30.3%) | 490 (41.6%) | 0.003* | |

| Female | 136 (69.7%) | 688 (58.4%) | |||

|

Education (n,%) |

Elementary school | 3 (1.5%) | 41 (3.4%) | 0.002* | |

| High school | 23 (11.8%) | 195 (16.6%) | |||

| College | 98 (50.3%) | 667 (56.6%) | |||

| Graduate | 71 (36.4%) | 275 (23.3%) | |||

|

Current smoker (n,%) |

No | 178 (91.3%) | 1005 (85.3%) | 0.025* | |

| Yes | 17 (8.7%) | 173 (14.7%) | |||

|

Alcohol consumption, last 30 days(n,%) |

No | 97 (49.7%) | 550 (46.7%) | 0.429 | |

| Yes | 98 (50.3%) | 628 (53.3%) | |||

| T2D Risk | T2D risk (FINDRISC <12) |

T2D risk (FINDRISC >12) |

Unadjusted | Adjusted | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 874 F (%) |

499 F (%) |

RP (95%CI) |

P value | RP (95%CI) |

P value | |||

| MedDiet component | ||||||||

| Olive oil | 302 (67.4%) | 146 (32.6%) | 0.854 (0.704-1.036) |

0.109 | 0,868 (0.711-1.059) |

0.163 | ||

| Vegetablesa | 182 (68.2%) | 85 (31.8%) | 0.850 (0.673-1.074) |

0.174 | 0.889 (0.697-1.133) |

0.341 | ||

| Fruitsa | 212 (69.3%) | 94 (30.7%) | 0.809 (0,647-1.013) |

0.065 | 0.821 (0.654-1.032) |

0.091 | ||

| Processed or red meatsa | 588 (62.6%) | 351 (37.4%) | 1.096 (0.905-1.328) |

0.349 | 1.082 (0.889-1.317) |

0.433 | ||

| Butter or cream or margarinea | 670 (63%) |

394 (37%) |

1.090 (0.879-1.351) |

0.434 | 1.028 (0.823-1.284) |

0.805 | ||

| Carbonated or sugary beveragesa |

621 (61.8%) | 384 (38.2%) | 1.223 (0.993-1.506) |

0.059 |

1.247 (1.002-1.552) |

0.048* | ||

| Winea | 59 [67.8] | 32.2 (%) | 0.879 (0,600-1.287) |

0.506 | 0.982 (0.665-1.448) |

0.925 | ||

| Legumesa | 523 (64.8%) | 284 (35.2%) | 0.926 (0,776-1.106) |

0.398 | 0.960 (0.803-1.149) |

0.660 | ||

| Fisha | 112 (69.1%) | 50 (30.9%) |

0.832 (0,622-1.115) |

0.219 | 0.878 (0.654-1.180) |

0.389 | ||

| Pastries. cakes. cookies or pastaa | 517 (62.2%) | 309 (37.4%) | 1.077 (0.899-1.290) |

0.421 | 1.069 (0.888-1.286) |

0.480 | ||

| Nutsa | 381 (65.1%) | 204 (34.9%) | 0.931 (0.779-1.113) |

0.436 | 0.969 (0.805-1.167) |

0.742 | ||

| Preference for white meata | 723 (63.6%) | 413 (36.4%) | 0.993 (1.333-0.962) |

0.962 | 0.991 (0.782-1.255) |

0.938 | ||

| Sofrito saucea | 593 [66.6%] | 298 [33.4%] | 0.802 [0.671-0.959] |

0.016* | 0.817 [0.682-0.979] |

0.028* | ||

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%IC) |

P value | OR (95%IC) |

P value | |

| BMI | 1.481 (1.373-1.596) |

<0.001 | 1.303 (1.122-1.513) |

<0.001 |

| WC | 1.167 (1.133-1.201) |

<0.001 | 1.129 (1.068-1.193) |

<0.001 |

| SMM | 1.088 (1.041-1.137) |

<0.001 | 0.907 (0.849-0.970) |

<0.004 |

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95%IC) |

P value | OR (95%IC) |

P value | |

| BMI | 1.328 (1.265-1.394) |

<0.001 | 1.132 (1.056-1.213) |

<0.001 |

| WC | 1.137 (1.114-1.161) |

<0.001 | 1.094 (1.062-1.127) |

<0.001 |

| SMM | 1.107 (1.056-1.161) |

<0.001 | 0.928 (0.873-0.987) |

0.018 |

| P value |

PR |

(95%IC) Inferior |

Superior |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, (male) | 0,000 | 0,646 | 0,514 | 0,812 |

| Smoke, (don’t smoke) | 0,009 | 0,798 | 0,675 | 0,944 |

| BMI | 0,000 | 1,057 | 1,034 | 1,080 |

| WC | 0,000 | 1,026 | 1,015 | 1,036 |

| SMM | 0,897 | 0,999 | 0,979 | 1,019 |

| Age | 0,000 | 1,036 | 1,029 | 1,043 |

| Fruits (do not Consume) |

0,000 | 1,350 | 1,146 | 1,589 |

| Sofrito (not Prepare) |

0,026 | 1,154 | 1,017 | 1,308 |

| Carbonated or sugary beverages (consume) | 0,841 | 1,015 | 0,877 | 1,175 |

| P value | PR | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inferior | Superior | |||

| Gender (male) | <0.001 | 0,658 | 0,526 | 0,823 |

| Smoking (Non- Smoking) |

0,015 | 0,814 | 0,690 | 0,961 |

| BMI | <0.001 | 1,057 | 1,035 | 1,079 |

| WC | <0.001 | 1,026 | 1,016 | 1,037 |

| SMM | 0,688 | 0,996 | 0,976 | 1,016 |

| Age | <0.001 | 1,035 | 1,028 | 1,043 |

| MEDAS-14 score | 0,001 | 0,947 | 0,918 | 0,978 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).